Summary

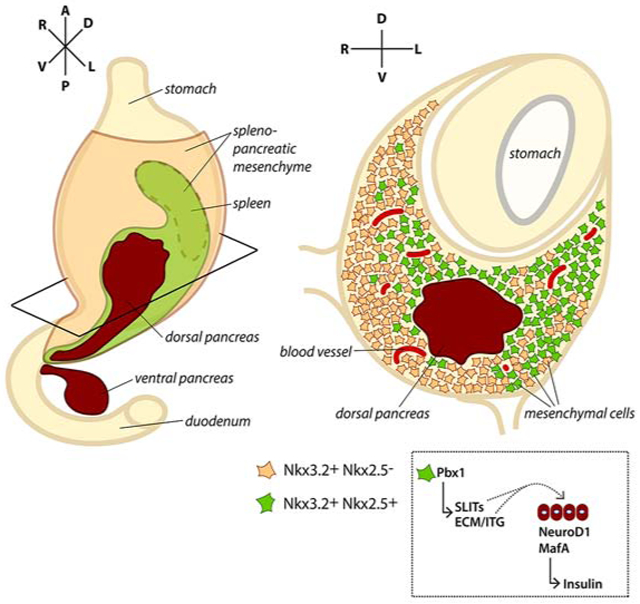

The interplay between pancreatic epithelium and surrounding microenvironment is pivotal for pancreas formation and differentiation as well as adult organ homeostasis. The mesenchyme is the main component of the embryonic pancreatic microenvironment, yet its cellular identity is broadly defined and whether it comprises functionally distinct cell subsets is not known. Using genetic lineage tracing, transcriptome and functional studies, we identified mesenchymal populations with different roles during pancreatic development. Moreover, we showed that Pbx transcription factors act within the mouse pancreatic mesenchyme to define a pro-endocrine specialized niche. Pbx directs differentiation of endocrine progenitors into insulin- and glucagon-positive cells through non-cell-autonomous regulation of ECM-integrin interactions and soluble molecules. Next, we measured functional conservation between mouse and human pancreatic mesenchyme by testing identified mesenchymal factors in an iPSC-based differentiation model. Our findings provide insights into how lineage-specific crosstalk between epithelium and neighboring mesenchymal cells underpin the generation of different pancreatic cell types.

Keywords: Pancreatic mesenchyme, endocrine differentiation, iPSC, lineage tracing, pancreas, PBX

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

The diversity of mesenchymal cell types in the pancreas that influence cell differentiation is poorly defined. Cozzitorto et al. identified a specialized microenvironment that surrounds the developing pancreas and promotes the formation of insulin-producing cells.

Introduction

The pancreatic microenvironment is composed of multiple cell types, including mesenchymal cells, endothelial cells, neural crest-derived and immune cells, as well as structural molecules, which are part of the extracellular matrix (ECM) (Angelo and Tremblay, 2018; Azizoglu and Cleaver, 2016; Geutskens et al., 2005; Gittes et al., 1996; Harari et al., 2019; Pierreux et al., 2010; Seymour and Serup, 2018). Various interactions occur between distinct pancreatic cell types and the surrounding cells or ECM components; these sets of interactions change with time, possibly influencing subsequent steps of pancreatic development, such as fate specification, growth, morphogenesis and/or differentiation (Seymour and Serup, 2018).

Mesenchymal cells are the most abundant category of cells composing the embryonic pancreatic microenvironment. Seminal studies based on ex vivo organ cultures and more recent in vivo mouse genetic models demonstrated the absolute requirement of the pancreatic mesenchyme throughout pancreatic organogenesis for epithelial growth and differentiation (Attali et al., 2007; Gittes et al., 1996; Golosow and Grobstein, 1962; Landsman et al., 2011). Mesenchymal cues have started to be characterized at the molecular levels mostly in the mouse; examples include members of the major signaling pathways, such as FGF, Wnt, Shh and Retinoic Acid (Bhushan et al., 2001; Harari et al., 2019; Seymour and Serup, 2018; Yung et al., 2019). These signaling molecules can exert distinct roles during development, being able to influence either the expansion of epithelial progenitors or their subsequent differentiation, or both. Advances in this field have had a tremendous impact on the establishment of directed differentiation protocols to generate insulin-producing β-cells from human pluripotent stem cells as a promising therapy for diabetes (Seymour and Serup, 2018; Sneddon et al., 2018).

Heterologous tissue recombination experiments and transcriptome analyses underscored the existence of organ-specific mesenchymal niches along the gastrointestinal tract that are responsible for each organ’s epithelial development and differentiation (Gittes et al., 1996; Golosow and Grobstein, 1962; Yung et al., 2019). For example, distinct mesenchymal gene signatures were found to typify pancreatic, stomach and intestinal stromal cells isolated from E13.5 mouse guts (Yung et al., 2019). Moreover, single-cell transcriptome analysis has recently unveiled high degree of heterogeneity even within the pancreatic microenvironment itself, suggesting the existence of different mesenchymal lineages that may create distinct “cellular niches” (Byrnes et al., 2018). However, whether such transcriptional heterogeneity corresponds to functional diversity is an open question. To date, the spatial distribution of these various cell types within the microenvironment and their potential functional contribution to pancreas formation have not been addressed.

Here, we used lineage tracing, transcriptome and genetic approaches, to characterize embryonic pancreas mesenchymal populations marked by Nkx3.2 and Nkx2.5. We identified a Pbx-dependent molecular network within the Nkx2.5-expressing mesenchyme, which locally regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk underlying endocrine differentiation. We then assessed the conservation of such specialized microenvironment using in vitro differentiation of human iPSCs into pancreatic cell lineage. Together, these studies shed light on the cellular and molecular complexity and heterogeneity of pancreatic mesenchymal niches and identify environmental factors critical for endocrine differentiation in both mouse and human.

Results

Lineage tracing of pancreatic mesenchymal cell populations

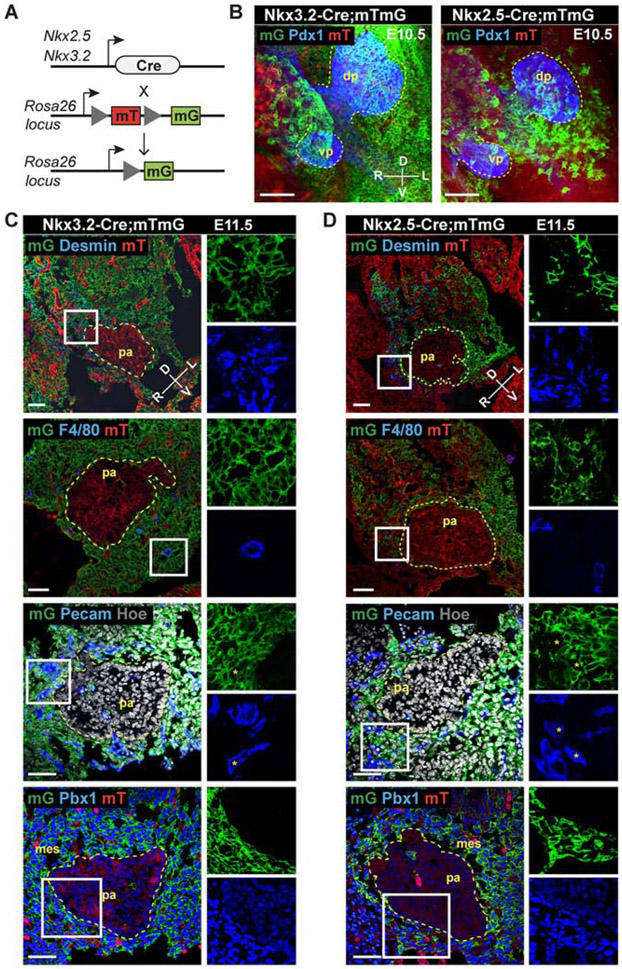

We used lineage tracing to map pancreatic mesenchymal cells and their spatial arrangement relative to epithelial progenitor cells and other cell types present in the pancreatic microenvironment of the mouse embryo (Figure 1). To identify the relative location and distribution of mesenchymal cells, we employed two Cre-recombinase-dependent labeling strategies in combination with the membrane-targeted tdTomato/membrane-targeted EGFP (mT/mG) double-fluorescent reporter mouse strain (Muzumdar et al., 2007). One strategy was based on the transcription factor (TF) Nkx3.2 (a.k.a. Bapx1), which drives the expression of Cre recombinase (Nkx3.2-Cre) (Verzi et al., 2009) in the mesenchyme of the developing pancreas, stomach, and gut from E9.5 (Landsman et al., 2011). The other approach took advantage of the Nkx2.5-Cre line (Stanley et al., 2002), which has been reported to direct the Cre activity to the visceral mesoderm and spleno-pancreatic mesenchyme between E9.5-E12.5 (Castagnaro et al., 2013; Koss et al., 2012). We found that Nkx3.2 (mG)-positive (+) descendant cells surround both pancreatic buds and represent a large fraction of mesenchymal cells (~70%) around the dorsal pancreas, while Nkx2.5-Cre-expressing cells give rise to a much smaller population (~30%), which was spatially confined to the mesenchyme surrounding the dorsal bud (Figures 1B-1D, S1 and S2C). In both transgenic strains the Cre activity was specific to mesenchymal cells, as judged by the co-expression of desmin and other mesenchymal markers, such as PDGFRβ, Collagen I and Islet 1, in a subset of Nkx2.5- and Nkx3.2-expressing cells (Figures 1C, 1D and S2A, S2B) and absence of the pancreatic TF Pdx1 (Figure 1B). Immunofluorescence (IF) staining showed that PECAM-1 does not colocalize with mG+ cells (Figures 1C and 1D), suggesting that Nkx2.5+ and Nkx3.2+ lineages do not contribute to the endothelial cells surrounding the pancreas. Moreover, only a small fraction of the Nkx2.5- (<10%) and Nkx3.2-descendant cells (~25%) overlap with F4/80, a marker commonly used to identify murine macrophages (Figures 1C, 1D and S2D).

Figure 1. Mesenchymal lineages expressing Nkx3.2 and Nkx2.5 surround the embryonic pancreas.

A, Schematic representation of the strategy for labelling Nkx3.2- and Nkx2.5-expressing mesenchymal cells with GFP (mG). B, Representative confocal maximum intensity z-projections of whole-mount immunofluorescence (IF) for Pdx1 (blue) on E10.5 Nkx3.2- and Nkx2.5-Cre;mTmG embryos. Yellow dashed lines mark pancreatic buds; in green (mG), surrounding mesenchyme; in red (mT), non-recombined tissue. dp, dorsal pancreas; vp, ventral pancreas. n = 3 independent embryos of each genotype. Scale bars, 50 μm. C, Representative confocal images of IF staining on cryosections of E11.5 Nkx3.2-Cre;mTmG embryos for the indicated markers. Nkx3.2-Cre-driven GFP expression is exclusive to mesenchymal cells in the pancreatic microenvironment. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification and as split channels on the right. D, Representative confocal images of IF staining on cryosections of E11.5 Nkx2.5-Cre;mTmG embryos for the indicated markers. Nkx2.5-Cre-driven GFP expression marks a subset of pancreatic mesenchymal cells, positioned on the left-lateral side of the dorsal pancreas. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification and as split channels on the right. mes, mesenchyme; pa, pancreas. Asterisks (*) indicate Pecam1-positive cells that are mG-negative. n = 3 independent embryos of each genotype were examined for each IF combination. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Taken together, these results suggest the existence of anatomically distinct pancreatic mesenchymal subtypes surrounding the pancreatic epithelium. While the Nkx3.2+ lineage broadly contributed to the gastrointestinal and pancreatic mesenchyme, the Nkx2.5+ lineage gave rise to a restricted organ niche, contributing only to a subset of Nkx3.2+ traced cells positioned on the left side of the dorsal pancreas (Figures 1, S1 and S2). This observation is consistent with recent single-cell transcriptome analyses of murine embryonic pancreata performed at the same developmental stage (Byrnes et al., 2018). After E12.5, both Nkx3.2 and Nkx2.5 transcripts were still expressed in the dorsal pancreatic mesenchyme and also labelled splenic precursors (Figures S1, S2F), as previously reported (Asayesh et al., 2006; Castagnaro et al., 2013; Koss et al., 2012).

Pancreatic mesenchymal lineages are functionally distinct

Next, we asked whether these two subsets of pancreatic mesenchymal cells exert distinct functions during pancreatic development and which are the genetic regulators that typify them. To date, only few transcription factors have been studied in the context of the pancreatic mesenchyme, including Islet 1, Nkx3.2 and Hox6 (Ahlgren et al., 1997; Asayesh et al., 2006; Hecksher-Sørensen et al., 2004; Landsman et al., 2011; Larsen et al., 2015). We discovered that the Pbx1 TALE (three amino acids loop extension) homeodomain protein TF is extremely abundant in the pancreatic mesenchyme starting from E9.5 and encompasses both Nkx3.2(mG)+ and Nkx2.5(mG)+ cell populations in the pancreatic mesenchyme (Figures 1C, 1D and S1D), besides being in the epithelium at lower levels. Previous work showed that constitutive homozygous deletion of Pbx1 (Pbx1−/−), in both mesenchyme and epithelium compartments, leads to pancreatic hypoplasia and defects in cell differentiation prior to death in utero at E15.5 (Kim et al., 2002). Thus, we reasoned that a genetic strategy for probing functional diversity of the two mesenchymal subtypes was to conditionally ablate Pbx1 in the pancreatic microenvironment using the Nkx3.2- and Nkx2.5-Cre lines. Because of the high degree of functional conservation among Pbx proteins, we generated mutant embryos with homozygous Pbx1 deletion in Cre-expressing cells on a Pbx2-heterozygous deficient background (Nkx3.2-Cre or Nkx2.5-Cre;Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/−). Cre-negative littermates as well as Cre Tg-only (without floxed sequences) served as negative controls in our experiments. Importantly, we found that the efficiency of Pbx1 deletion mediated by the two Cre Tg strains is comparable, mirroring the distinct distribution of endogenous Nkx3.2 or Nkx2.5 gene expression in the mesenchyme (Figures S1D-E). Upon conditional ablation of Pbx1 in the broad Nkx3.2+ digestive mesenchyme, we observed severe pancreatic hypoplasia, accompanied by stomach and duodenum defects; the Nkx3.2-Cre;Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/− mutant embryos are hereafter referred to as PbxNkx3.2MES-Δ (Figure S3A). IF analysis showed that all pancreatic cell types are present in PbxNkx3.2MES-Δ mutant pancreata and the number of insulin+ and glucagon+ cells as relative to the total pancreatic area is unchanged (Figure S3B). PbxNkx3.2MES-Δ deletion resulted in lethality at birth, most likely due to the severe defects in gastrointestinal tract and asplenia (Figure S3A).

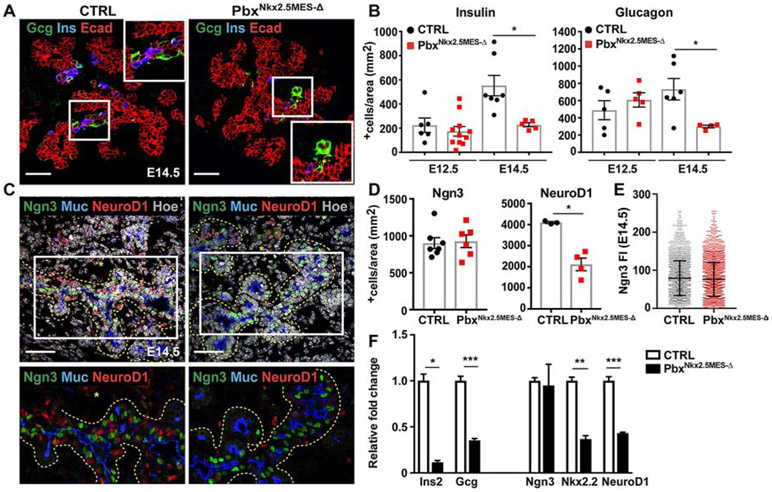

By contrast, Pbx1 deletion in the more restricted pancreatic-specific Nkx2.5+ mesenchyme did not affect pancreas organ size (Figures S3 and S4C). However, Nkx2.5-Cre;Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/− mutant embryos (hereafter referred to as pbxNkx2.5MES-Δ) showed severe defects in the pancreatic endocrine compartment, displaying 50% reduction in the number of both insulin+ and glucagon+ cells when compared to controls, starting from E14.5 (Figures 2A and 2B). The decrease in endocrine cells was detectable after E12.5, which coincides with the onset of the secondary transition (Pan and Wright, 2011) (Figure 2B). Moreover, the defects were confined to the dorsal portion of the pancreas, which is in line with the expression pattern of Nkx2.5 in the dorsal pancreatic mesenchyme (Figure 1). To assess individual contribution of Pbx1 we compared the number of insulin+ cells in Nkx2.5-Cre;Pbx1flox/flox mutants versus PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata and found a comparable reduction, even though slightly less important, in the single mutant (Figure S4E). We thus focused on the combined deletion and used the PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ for the rest of the study.

Figure 2. Pbx1 in the Nkx2.5-mesenchyme controls endocrine differentiation downstream of Neurogenin 3.

A, IF analysis of Glucagon (Gcg), Insulin (Ins) and E-cadherin (Ecad) on control (CTRL) and pbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5 mouse pancreatic cryosections. In white insets are shown higher magnification of boxed area. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, Quantification of Insulin+ and Glucagon+ cells at E12.5 and E14.5. Cell numbers were expressed relative to the area (in mm2) of the Ecad+ pancreatic epithelium. Insulin IF, n=6 embryos (CTRL E12.5); n=7 embryos (CTRL E14.5); n=11 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E12.5); n=5 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5). Glucagon IF, n=5 embryos (CTRL E12.5); n=6 embryos (CTRL E14.5); n=5 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E12.5); n=4 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5). * p<0.05. C, IF analysis of Neurogenin3 (Ngn3), NeuroD1 and Mucin1 (Muc) on control (CTRL) and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5 mouse pancreatic cryosections. Hoechst nuclear counterstaining is shown in grey. Yellow dashed lines mark pancreatic epithelium. Bottom panel shows magnified views of the marked regions and asterisks (*) indicate clusters of delaminating cells. Scale bars, 50 μm. D, Quantification of Ngn3+ and NeuroD1+ cells at E14.5. Cell numbers were expressed relative to the area (in mm2) of the Ecad+ pancreatic epithelium. Ngn3 IF, n=7 embryos (CTRL), n=6 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ); NeuroD1 IF, n=3 embryos (CTRL), n=4 embryos (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ). * p<0.05. E, Single cell measurement of fluorescence intensity (FI) of Ngn3 in E14.5 CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata. FI individual values were measured in n=2489 cells CTRL, n=3203 cells PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ from n≥3 embryos per each genotype. F, Representative RT-qPCR analysis for the indicated pancreatic genes performed on E14.5 CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata (n=3 independent samples per genotype). Data are represented as relative fold change. Values shown are mean ± s.e.m. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001; two-tailed paired t-tests.

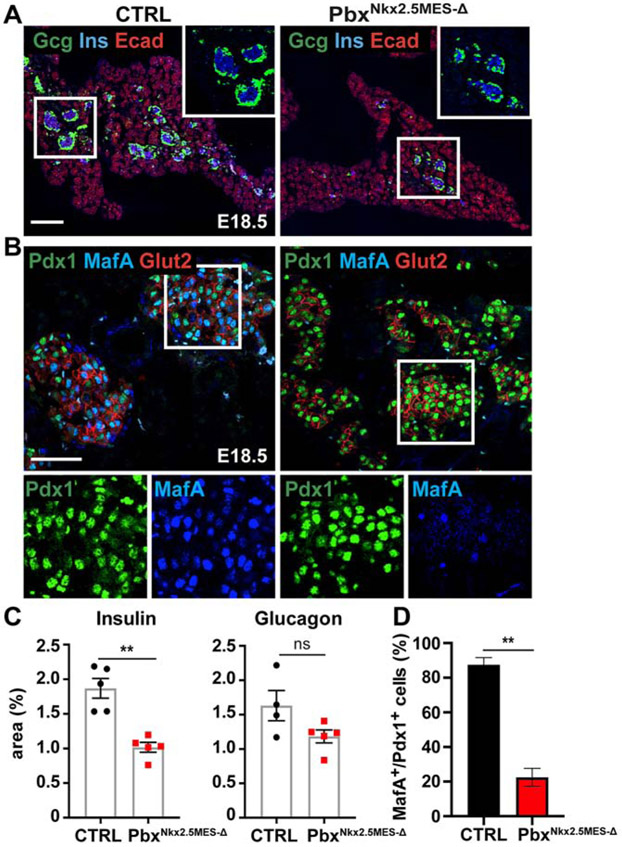

We found that the insulin+ β-cell population continue to be significantly reduced at birth in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ mice (Figures 3A and 3C). Consistently, PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ adult animals showed impaired glucose tolerance and delay in the restoration of basal glucose levels (Figure S3E). These are functional consequences of a reduced insulin-producing cell number and signs of pre-diabetic conditions. Altogether, our findings not only indicate a previously unappreciated role for Pbx1 in the pancreatic mesenchyme but also suggest distinct functions of Nkx3.2- and Nkx2.5-descendant mesenchymal populations.

Figure 3. β-cell differentiation is hampered by Pbx1 deletion in the Nkx2.5-mesenchyme.

A, Representative IF staining of Glucagon (Gcg), Insulin (Ins) and E-cadherin (Ecad) on control (CTRL) and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E18.5 mouse pancreatic cryosections. In white insets are shown higher magnification of boxed area. Scale bars, 200 μm. B, IF analysis of β-cell differentiation markers, Pdx1, MafA and Glut2, on control (CTRL) and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E18.5 mouse pancreatic cryosections. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification and in split channels at the bottom. Scale bars, 50 μm. C, Plots show measurement of Insulin+ and Glucagon+ areas, normalized by total epithelial Ecad+ area, in control (CTRL) and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E18.5 pancreata. Values shown are mean ± s.e.m. **p < 0.01. Insulin IF, n=5 pancreas (CTRL); n=5 pancreas (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ). Glucagon IF, n=4 pancreas (CTRL); n=5 pancreas (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ). D, Plot shows percentage (%) of MafA+/Pdx1+ cells within the total Pdx1+ cell population in E18.5 CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ islets. IF, n=3 pancreas (CTRL), n=3 pancreas (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ). ** p<0.01; two-tailed paired t-tests.

Pbx1 defines a specialized pro-endocrine Nkx2.5+ mesenchyme

We next set out to investigate how a Pbx-dependent paracrine crosstalk between mesenchyme and epithelium controls the number of insulin-producing cells. First, we further analyzed cell differentiation in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ and found that the exocrine pancreatic cell lineage and overall tissue-architecture are preserved in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata (Figure S4). Next, we addressed whether the reduction in insulin+ and glucagon+ cells might be due to defects in endocrine progenitor specification and/or differentiation in the mutant pancreata. Quantification of the endocrine progenitor pool at E12.5, as marked by the TF Neurogenin3 (Ngn3) and its direct target Pax6, revealed no differences between PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ and control embryos (Figure S4A and 4B), ruling out early defects in endocrine specification. RT-qPCR analysis on E14.5 dorsal pancreatic cells confirmed the reduction in insulin and glucagon, whereas Ngn3 expression in mutant embryos was unchanged compared to controls (Figure 2F). Consistently, IF analysis showed no difference in the number of Ngn3+ cells of PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5 pancreata compared to controls within the proximal trunk epithelium, as demarcated by Mucin1 staining (Figures 2C and 2D). Additionally, the range of Ngn3 levels (from high to low) was unchanged between control and mutant cells (Figure 2E), ruling out a reduction of the Ngn3high bona fide endocrine progenitors (Bankaitis et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2010). By contrast, the expression levels of endocrine TFs, such as Nkx2.2 and NeuroD1, which act downstream of Ngn3 in the endocrine differentiation cascade (Mastracci et al., 2013; Romer et al., 2019), were strongly downregulated at E14.5 (Figure 2F). This was confirmed by IF showing striking reduction in the number of NeuroD1+ cells in E14.5 mutant pancreata (Figures 2C and 2D). Finally, we measured no changes in cell proliferation and/or apoptosis in the PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata, as judged by IF for the phosphorylated form of the histone H3 (pHH3) and TUNEL assay, respectively (Figures S4G-I). Together, these data show that deletion of Pbx1 in the Nkx2.5-expressing mesenchymal population results in endocrine differentiation defects downstream of Ngn3.

Consistent with defective differentiation, we also found a reduced numbers of cells expressing the β-cell maturation TF MafA in the mutant islets at later stages (Figures 3B and 3D). MafA is a major regulator of insulin gene expression (Artner et al., 2010) and, recently, it has been reported to be downstream of NEUROD1 in both murine embryonic endocrine tissue and hESC-derived beta-like cells (Romer et al., 2019). Hence, a dysregulated NeuroD1/MafA transcriptional network might be responsible for the reduced β-cells and glucose clearance control in Pbx Nkx2.5MES-Δ mice.

We took advantage of the same genetic model to compare the role(s) of Pbx1 in the pancreatic mesenchyme to the one in the epithelium (Figure S3). Likewise in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ embryos, we found that conditional, Pdx1-Cre-mediated, deletion of Pbx1 in the pancreatic epithelium also leads to pancreatic developmental defects, including a reduced number of endocrine cells (Figures S3G-H). However, the loss of Pbx1 in the epithelium caused earlier defects in Ngn3+ endocrine progenitor specification (Figures S3I and S3J).

Pbx-downstream regulatory network in the pancreatic mesenchyme

To investigate how Pbx functions in the pancreatic mesenchyme and to dissect its downstream regulatory network, we performed RNA-Seq analysis. To separate mesenchymal cells from epithelial ones, we intercrossed the mT/mG mouse reporter strain with Nkx2.5-Cre;Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/− (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ) mutants and used a FACS-based isolation strategy (Figure S5A and Table S1). Nkx2.5+ recombined/mG and non-recombined/mT fractions were collected from mT/mG;PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ and mT/mG control E12.5 dorsal pancreata and subjected to bulk RNA-Seq. As expected, mesenchymal TFs Nkx2.5 and Nkx3.2 were enriched in the mG/mesenchymal [Mes] fraction, while Pdx1 and epithelial marker genes (e.g. Epcam, Cdh1) were exclusively expressed in the mT fraction, therefore referred to as mT/epithelial [Ep] (Figures S5B and S5C).

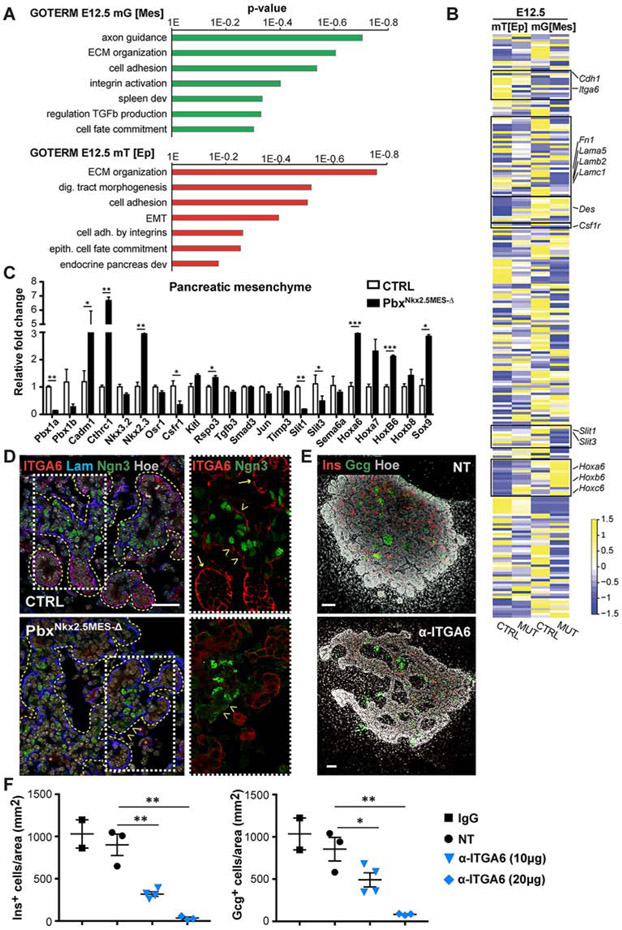

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEG) between control and mutant pancreatic mesenchymal cells revealed significant enrichment for biological processes (BP) categories, such as axon guidance signaling [e.g. Slit1, Slit3], ECM organization [e.g. Fn1, Lamb2, Lamc1, Cthrc1] and cell adhesion and integrin activation [e.g. Cadm1] (Figures 4A). Interestingly, similar GO terms were found significantly enriched among the DEGs in pancreatic epithelial fractions at matching stages, including ECM organization, cell adhesion mediated by integrins [e.g. Itga6], cell fate commitment (Figures 4A and 4B). As expected, we also found signatures, which are unique to each fraction, for instance the “Spleen development” BP term [e.g. Pbx1, Nkx2.3] was significantly enriched only in the mutant pancreatic mesenchyme (Figure 4A), which is in line with the previously reported role of Pbx in spleen formation (Koss et al., 2012). By contrast, transcripts from the “Endocrine pancreas development” GO category [e.g. NeuroD1, Ins1, Ins2] were specifically downregulated in the pancreatic mT[Ep] of PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ embryos (Figure 4A), in agreement with RT-qPCR and IF results (Figure 2).

Figure 4. Defining Pbx-dependent regulatory networks in the Nkx2.5+ pancreatic mesenchyme.

A, Gene Ontology (GO) biological process terms significantly enriched in differentially expressed genes (p<0.05) between E12.5 CTRL and mTmG;PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ (MUT) RNA-Seq datasets. RNA-Seq was performed on FACS-sorted mG+ and mT+ fractions from mTmG;Nkx2.5-Cre CTRL and mTmG;PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ (MUT) pancreata. The recombined mG+ fraction is referred to as mesenchyme [Mes] and the nonrecombined mT+ as epithelial [Ep], being strongly enriched of epithelial and pancreatic marker genes (see Figures S5B, C). n=5 embryonic pancreata per genotype were pooled for FACS/RNASeq. B, Heatmap of a subset of differentially expressed genes within the mT+ [Ep] epithelial and mG+ [Mes] compartments of CTRL and mTmG;PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ (MUT) pancreata at E12.5. Colors represent high (yellow) or low (blue) expression values based on Z-score normalized FPKM values for each gene (Supplemental Table 1). Boxes highlight gene sets validated by either RT-qPCR or IF analyses. C, RT-qPCR validation analysis of indicated marker genes on mG+ mesenchymal fractions derived from E12.5 CTRL and mutant embryos. Absence of Pbx1 (Pbx1a and Pbx1b isoforms) was confirmed in the PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreatic mesenchyme. Data are represented as relative fold change. Values shown are mean ± s.e.m. n≥3. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. D, IF analysis of Integrin a6 (ITGA6), Laminin (Lam), Neurogenin3 (Ngn3) on control (CTRL) and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E14.5 mouse pancreatic cryosections. Boxed area are shown at higher magnification on the right, displaying ITGA6 (Red) and Ngn3 (Green) channels. Yellow dashed lines mark pancreatic epithelium. Arrows indicate acinar structures; arrowheads indicate trunk regions. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, Whole-mount IF analysis of Glucagon (Gcg) and Insulin (Ins) on mouse pancreatic explants treated for 3 days with blocking antibodies against Integrin α6 (α-ITGA6) or left untreated as controls (NT). Hoechst (Hoe), nuclear counterstain. Scale bars, 100 μm. F, Quantification of Insulin+ and Glucagon+ cells in pancreatic explants after 3 days in culture with indicated doses of α-ITGA6 blocking antibody. Nontreated (NT) and Immunoglobulin G (IgG)-treated samples were used as controls. Cell counts were normalized to the average Ecad+ epithelium area (mm2). n=2 (IgG), n=3 (NT), n=4 (α-ITGA6 10μg), n=3 (α-ITGA6 20 μg) explants. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01; two-tailed paired t-tests.

ECM-Integrin interactions regulate the paracrine crosstalk between Nkx2.5+ pancreatic mesenchyme and the epithelium

Based on the GO enrichment analysis, we focused our validation and functional analyses on the ECM organization and axon guidance signaling categories that were the most significantly dysregulated ones upon Pbx-depletion in the mesenchyme (Figures 4, S5). We found that both ECM proteins, laminin and fibronectin, whose transcripts were downregulated in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata, display selective disrupted distribution at the basement membrane (BM). Specifically, we identified regions at the epithelial/mesenchyme interface, which lacked or displayed reduced laminin and fibronectin immunoreactivity (Figures S5D and S5F). The BM is a fundamental site of epithelial cell-ECM interactions that are mediated by a number of cell receptors, including the integrins (Horton et al., 2016; Humphries et al., 2019). Components of the BM and some integrins, such as Itgb1, have been shown to regulate pancreas morphogenesis and differentiation (Cirulli et al., 2000; Crisera et al., 2000; Mamidi et al., 2018; Shih et al., 2016). Concomitant with the BM defects, we found downregulated expression of Integrin α6 (Itga6) subunit, which is a receptor for laminin (Horton et al., 2016; Humphries et al., 2019), while other integrin receptors levels were unchanged in the PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreatic epithelium (Figures 4B and S5E). Next, we performed IF analysis to further validate the ITGA6 reduction in the pancreatic epithelium. Notably, ITGA6 displayed anisotropic distribution within the epithelium, preferentially accumulating at the terminal ends of the elongating branches (a.k.a. tip domains) at E14.5 (Figure 4D; see arrows). The tip regions contain cells that are progressively restricted to an acinar fate in the embryonic pancreas, while the trunk domain contains the endocrine/duct bi-potent progenitors (Larsen and Grapin-Botton, 2017; Pan and Wright, 2011). In PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ embryos ITGA6 levels were overall reduced, which resulted in a complete absence of this laminin receptor along the trunk region (Figure 4D; see arrowheads). To functionally interrogate the role of ITGA6 in the pancreatic epithelium and mimic its absence, we used pancreatic explants dissected from E12.5 wild-type embryos (Petzold and Spagnoli, 2012) and cultured ex vivo in the presence of a blocking antibody against ITGA6 (α-ITGA6), which hampers laminin-ITGA6 interaction. Pancreatic explants treated with α-ITGA6 showed a dose-dependent reduction of insulin+ and glucagon+ cells accompanied by morphogenetic defects as compared to both nontreated (NT) and Immunoglobulin G (IgG)-treated control samples (Figures 4E-F). These results indicate that Pbx1 deletion in the Nkx2.5+ pancreatic mesenchyme disrupts ECM and integrin interactions, particularly at the trunk domain, which in turn affects endocrine differentiation. This is in line with the current model of ‘regionalization’ of the pancreatic epithelial plexus, wherein the trunk serves as a niche harboring endocrine progenitors during organ growth and morphogenesis (Bankaitis et al., 2015; Pan and Wright, 2011).

Axon guidance signaling pathway is enriched in the Nkx2.5+ mesenchyme

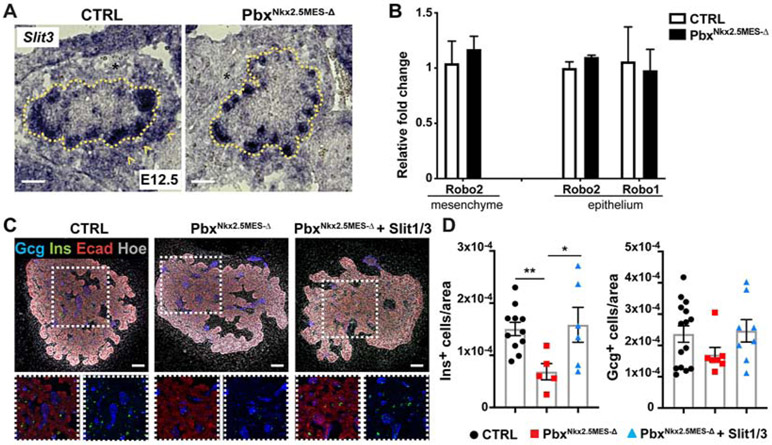

The “axon guidance” category was the most significantly enriched signaling pathway in the DEG list between control and pbxNkx2.5MES-Δ mesenchyme (Figure 4). Within this category, we found dysregulation of the secreted Slit glycoproteins, which are classic axon guidance molecules that act as repulsive cues through their well characterized receptors, Robo1/2, in the nervous system (Ypsilanti et al., 2010). More recently, the Slit/Robo pathway has been involved in various aspects of pancreas organogenesis as well as pancreatic cancer (Adams et al., 2018; Escot et al., 2018; Pinho et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2013). RT-qPCR and in situ hybridization confirmed the downregulation of both Slit1 and Slit3 expression in the mutant pancreatic mesenchyme (Figures 4C and 5A), while Robo1 and Robo2 levels were unchanged in both mesenchyme and epithelium (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. Role of Slit molecules in endocrine cell differentiation.

A, Representative ISH micrographs for Slit3 on cryosections of E12.5 CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ embryos. Dotted line demarcates the pancreatic epithelium. Arrowheads indicate expression in the mesenchyme. *, mesenchyme. Scale bars, 50 μm. B, RT-qPCR validation analysis of indicated Robo genes on mesenchymal and epithelial fractions from CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ embryos. Data are represented as relative fold change normalized on 36B4 expression. Values shown are mean ± s.e.m. n≥3. C, Representative whole-mount IF for Insulin (Ins) and Glucagon (Gcg) on pancreatic explants from CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E12.5 embryos cultured for two days in the presence of Slit1/Slit3 recombinant proteins or left untreated. Insets show boxed area in split channels. Scale bars, 50 μm. D, Scatter plots with bars showing the quantification of Insulin-and Glucagon-positive cells in pancreatic explants from CTRL and PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ E12.5 embryos cultured in the presence of Slit1/Slit3 or left untreated. Number of positive cells were normalized to the pancreatic epithelial (Ecad+) area (μm2). * p<0.05; two-tailed paired t-tests.

To test whether Slit signaling molecules play a role in endocrine cell differentiation, we performed rescue experiments in PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreatic explants (Figure 5). In rescue experiments, pancreatic explants were dissected from E12.5 control and mutant embryos and cultured in the presence of recombinant Slit1 and Slit3 proteins. Consistent with the in vivo phenotype (Figure 2), ex vivo cultured pbxNkx2.5MES-Δ pancreata showed a significant reduction in the number of insulin+ cells (Figures 5C-D), but not of glucagon+ cells; the addition of Slit1/Slit3 combination was sufficient to restore the number of insulin+ cells (Figure 5D). This result suggests that Slit molecules are among the mesenchymal signaling factors that non-cell autonomously regulate endocrine differentiation.

Conservation between human and mouse pancreatic mesenchyme

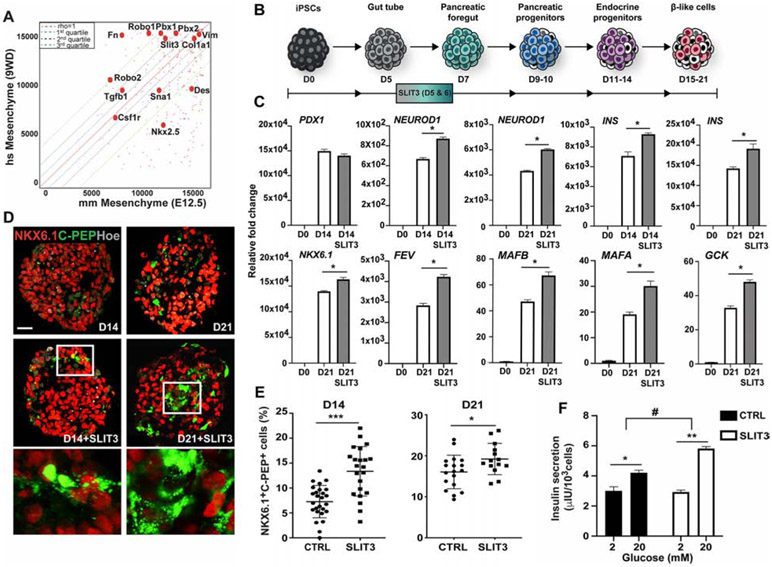

ROBO and SLIT have been previously found in human pancreatic tumor microenvironment (Pinho et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019), however it is unknown if they are also present in the microenvironment surrounding human embryonic pancreas. Moreover, to what extent the mouse pancreatic microenvironment is similar to the human one is yet an open question. To start answering these questions, we compared our E12.5 mouse mesenchyme RNASeq dataset to published datasets of human embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme at equivalent stages (week 9-gestational age) (Ramond et al., 2017). Besides the well-known mesenchymal marker VIMENTIN, whose relative expression in the mouse and human datasets was almost equivalent, we found PBX TFs and SLIT3 signaling factor to be present in the human embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme, too (Figure 6A). Next, to study the functional conservation of mesenchymal SLIT factors in human endocrine differentiation, we turned to a human pluripotent stem cell culture system for modeling human pancreatic development (Russ et al., 2015). Specifically, iPS cells undergoing pancreatic differentiation were treated with recombinant hSLIT3 protein for 48h and, subsequently, analyzed by RT-qPCR and IF at day (D) 14 and 21 (Figures 6B-E). We found that the ROBO2 receptor gene is expressed at highest levels at D5 stage of differentiation, which coincides with the induction of PDX1 expression in the culture (Figures S6A-B). Upon exposure to SLIT3, we observed an increase in the expression levels of NEUROD1 accompanied by higher levels of endocrine hormone transcripts, including INSULIN, GLUCAGON and SOMATOSTATIN (Figures 6C and S6F). Additionally, the human β-cell TFs MAFB and MAFA were robustly expressed in the treated β-like cells at D21 as well as other genes essential for human β-cell functionality, such as the GCK1 and KIR6.2 (Figures 6C and S6F).

Figure 6. Functional conservation of pro-endocrine mesenchymal signal factors.

A, Scatterplot between human pancreatic mesenchyme (9 weeks-GA) and mouse mesenchyme (E12.5) transcriptome datasets. Each point represents the ranks of a gene in each expression dataset. The overall Spearman rank order correlation between the mouse and human datasets was 0.679. Rho=1 is indicated by the red dashed line on the diagonal. Quartile distances from the rho=1 line are indicated by blue, black and green dashed lines, representing first quartile, second quartile and third quartile distances, respectively. The closer a point (gene) is to the diagonal, the higher the correlation between the ranks of the gene expression in the mouse and human datasets. Pbx genes and a subset of mesenchymal regulated genes are labeled in the scatterplot. B, Schematic representation of the differentiation protocol of iPSCs into β-like cells (Russ et al., 2015). Cell clusters were treated in suspension with SLIT3 for 48h at day (D) 5 of differentiation. C, RT-qPCR analysis of selected gene transcripts in undifferentiated iPSCs (D0) and differentiated cells at D14 and D21 cultured with SLIT3 or untreated. Data are represented as relative fold change. Values shown are mean ± s.e.m. n=3. * p <0.05. D, Representative IF images of NKX6.1 and C-Peptide (C-PEP) on differentiated clusters at D14 and D21. Hoechst (Hoe) was used as nuclear counterstain. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification. Scale bars, 50 um. E, Scatter plots show significant increase of NKX6.1- and C-PEPTIDE-double positive cells upon treatment with SLIT3. The number of NKX6.1+/C-PEP+ cells was normalized to the total number of cells contained in each cluster and shown as %. n=3 independent differentiation experiments. * p <0.05; *** p<0.001; two-tailed paired t-tests. F, Representative static Glucose Stimulation Insulin Secretion (GSIS) assay of D21 untreated control (CTRL) and SLIT3-treated iPSC-differentiated cultures. Cells were challenged sequentially with low [2mM] and high [20 mM] glucose with a 60 min incubation for each concentration. Values shown are mean ± s.d. n=3 independent differentiation experiments. * p <0.05; ** p<0.01; # p <0.05 two-tailed paired t-tests.

To test whether SLIT3 might affect proliferation or survival of iPSCs during directed differentiation, we quantified the number of pHH3+ and active Caspase-3 (CAS3)+ (marker of apoptosis) in the differentiated clusters (Figure S6H). IF staining showed no change in the number of proliferating nor apoptotic cells after treatment with SLIT3 compared to untreated cells undergoing differentiation (Figure S6H). Moreover, we did not detect mesenchymal cells during pancreatic differentiation of iPSCs, beside a modest induction of VIMENTIN (VMN) at the transcript level and protein level in a subset of pancreatic cells in the clusters (Figures S6D and S6G). This is in line with recent findings in human pancreatic islets by single-cell RNASeq and immunofluorescence analysis (Efrat, 2019; Segerstolpe et al., 2016), which reported VMN localization mostly in α-cells and to a less extent in β-cells or polyhormonal cells. In the presence of SLIT3, we did not find any changes in the expression of VMN or induction of other mesenchymal markers in hiPSC-derived clusters, suggesting that its activity is primarily on epithelial cells in this context (Figure S6E).

C-PEPTIDE was used as a marker for detecting endogenous insulin production. IF results were consistent with the RT-qPCR data, revealing a higher fraction of cells positive for C-PEPTIDE that also expressed NKX6.1 in the SLIT3-treated clusters compared to untreated cells (Figures 6D-E). Notably, the C-PEPTIDE+/NKX6.1+ population has been reported to more closely resemble to endogenous human β-cells than the NKX6.1− population (Russ et al., 2015; Sneddon et al., 2018). Consistently, we found that exposure to SLIT3 leads to an improvement of the functional maturation of hiPSC-derived β-like cells, with the treated cells showing an increase of insulin release in response to glucose stimulation (Figure 6F). Taken together, these results indicate that the SLIT guidance pathway enhances endocrine differentiation from human pluripotent cells, suggesting functional conservation with the mouse.

Discussion

A stem cell or progenitor cell microenvironment is defined by the sum of cell-cell, cell-ECM and cell-soluble factor interactions, physical and geometric constraints that are experienced by a cell (Lander et al., 2012). We defined here a specialized microenvironment that favors in vivo the differentiation along the pancreatic endocrine lineage. Moreover, we unveiled a Pbx-dependent molecular network within this microenvironment, which locally regulates the epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk underlying endocrine differentiation. A previous study reported that Pbx1 constitutive inactivation in the mouse results into pancreatic hypoplasia and differentiation defects (Kim et al., 2002). Despite this fundamental original observation (Kim et al., 2002), the basic mechanisms underlying the requirements for PBX in mammalian pancreatic development remain largely unexplored. Here, we studied cell-type-specific requirements for Pbx1 using a conditional floxed allele in combination with various mesenchymal Cre Tg lines. We also showed that Pbx1 in the pancreatic epithelium is required for endocrine cell differentiation, but likely through earlier cell-autonomous control of Ngn3+ endocrine progenitor specification. Thus, these results suggest distinct roles of Pbx in the regulation of pancreatic differentiation depending of the cellular context, either mesenchymal or epithelial contexts, and, possibly, due to different Pbx co-factors availabilities.

The dramatic reduction in pancreatic organ size observed upon deletion of Pbx1 in the broad Nkx3.2-traced mesenchyme suggests a requirement of Pbx in the mesenchyme for the overall expansion of pancreatic progenitor cells. These defects resemble those observed after the elimination of Nkx3.2-mesenchyme via Cre-mediated mesenchymal expression of Diphtheria Toxin at the early stages of pancreas formation (Landsman et al., 2011). Given that Nkx3.2-Cre is widely active in mesenchymal cells surrounding the pancreas from the time of its fate specification, it is plausible that Pbx1 regulates the expression of a mesenchymal signal(s), which controls pancreatic progenitor proliferation, ensuring the expansion of all pancreatic cell types (both exocrine and endocrine compartments) in equal measures before differentiation has started. By contrast, Pbx1 in the Nkx2.5-descendant mesenchyme did not impact the early expansion of pancreatic progenitors and, therefore, its non-cell autonomous influence on endocrine lineage differentiation could become apparent. Hence, besides additional spatial information also more refined temporal control is needed to better resolve the functional diversity of mesenchymal populations in the pancreas.

Recent studies have started to provide insights into how three-dimensional microenvironment enhances endocrine differentiation in the developing pancreas (Bankaitis et al., 2015; Heymans et al., 2019; Mamidi et al., 2018; Shih et al., 2016). For example, Mamidi et al. (Mamidi et al., 2018) suggested that the choice of bi-potent progenitor cells within the pancreatic trunk region is dictated by the nature of ECM deposition. Enhanced laminin deposition has been suggested to induce endocrine differentiation, while activation of ITGA5 by fibronectin appears to inhibit endocrinogenesis (Mamidi et al., 2018). Thus, different “ECM-niches” in the embryonic pancreas microenvironment might exert different effects on progenitor cells influencing their fate decision. Here, we characterized a mesenchymal cell population that produces defined ECMs together with secreted signaling factors, promoting endocrine differentiation. In line with previous studies (Heymans et al., 2019; Mamidi et al., 2018), we identified laminin deposition along the BM that surrounds the pancreatic trunk region and showed that it is accompanied by a differential expression of ITGA6 along the tip-trunk region of pancreatic primary branches. Moreover, blocking the ITGA6-laminin axis perturbed endocrine differentiation. We therefore propose that a gradient of integrin receptors might help pancreatic progenitors to differentially interpret and respond to the environment/ECM and, in turn, activate distinct cell fates. Future systematic qualitative and quantitative analyses of the ECM components and respective integrin receptors at higher resolution are required to define blueprints for reproducing in vivo microenvironments.

Finally, the development of protocols for differentiating human pluripotent stem cells into pancreatic cells has provided extremely valuable models to study human pancreas development (Gaertner et al., 2019). Nevertheless, in vitro models do not always faithfully recapitulate the succession of events occurring in vivo during human embryonic pancreas. Moreover, the effects reported upon the addition of a certain molecule factor (e.g. SLITs) to the stem cell culture might not exactly reflect the extent of its in vivo activities, possible interactions with other signaling pathways or ECM proteins, which depend on spatial and temporal niches that we still cannot reproduce in vitro.

In conclusion, our work unveils that cell populations endowed with different functions exist within the mesenchyme of the developing pancreas. Insights into the complexity of the in vivo pancreatic microenvironment and lineage-specific crosstalk could potentially help in defining targeted protocols for differentiating human pluripotent stem cells into different pancreatic cell types.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Francesca M. Spagnoli (francesca.spagnoli@kcl.ac.uk).

Materials Availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and Code Availability

RNA-Seq data generated during this study are deposited in the GEO public database under accession number # GSE123759 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

EXPERIMENTAL MODELS AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mouse strains

The following mouse strains were used: Nkx2-5tm2(cre)Rph (Stanley et al., 2002), Nkx3-2tm1(cre)WeZ (Verzi et al., 2009), B6.FVB-Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv (Hingorani et al., 2003), Pbx1tm2Mlc (Koss et al., 2012), Pbx2tm1Mlc (Selleri et al., 2004), B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB_tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J (Muzumdar et al., 2007). Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/− were generated by inter-crossing mice heterozygous for both mutant alleles. For conditional ablation in the pancreatic mesenchyme, Pbx1flox/+;Pbx2+/− mice were intercrossed with Nkx2-5tm2(cre)Rph or Nkx3-2tm1(cre)Wez transgenic (Tg) strains. For conditional ablation in the pancreas, Pbx1flox/+;Pbx2+/− mice were intercrossed with Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv/Nci (a.k.a. Pdx1-Cre) mice.

All procedures relating to animal care and treatment conformed to the Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee of the MDC and Berlin State Office for Health and Social Affairs (LaGeSo), Germany and King’s College London. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free, temperature-controlled facility with a 12-h light/dark cycle in individual ventilated cages. Animals were provided food (standard rodent chow diet) and water ad libitum. Phenotypic analysis was performed on > 6 months old male mice. Metabolic assays were performed in adult male mice (6-12 months age).

Cell lines and cell culture

Human iPS cell lines BIHi043-A (XM001) (sex: female) (Wang et al., 2018) and BIHi005-A (sex: male) have been registered in the European Human Pluripotent Stem Cell Registry (hPSCreg) (https://hpscreg.eu/cell-line/HMGUi001-A) and were authenticated by karyotyping. Human iPSC lines were maintained on Geltrex-coated (Invitrogen) plates in home-made E8 media under hypoxic conditions. The medium was changed daily and cells were passaged every ~3 days as cell clumps or single cells using 0.5 mM EDTA (Invitrogen) or Accutase (Invitrogen), respectively. Medium was supplemented with 10 μM Rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) inhibitor Y-27632 (Sigma) when iPSCs were thawed or passaged as single cells.

Pancreatic explants culture

Dorsal pancreatic buds were microdissected from mouse embryos at E12.5 and cultured on glass-bottom dishes (Matek) pre-coated with 50 μg/ml sterile bovine Fibronectin (Invitrogen) in Basal Medium Eagle (BME, Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS (Invitrogen), 1% Glutamine, 1% Penicillin-Streptomycin (PS) (Invitrogen) (Petzold and Spagnoli, 2012).

METHOD DETAILS

Differentiation of pluripotent iPSCs into pancreatic β-like cells

Human iPSC lines [BIHi043-A (XM001) (Wang et al., 2018) and BIHi005-A] differentiation was carried out following a 21-day protocol previously described in (Russ et al., 2015). Briefly, iPSCs were dissociated using Accutase and seeded at a density of 5.5 x106 cells per well in ultra-low attachment 6-well plates (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in E8 medium supplemented with 10 μM ROCK inhibitor, 10 ng/ml Activin A (R&D Systems) and 10 ng/ml Heregulin (Peprotech). Plates were placed on an orbital shaker at 100 rpm to induce sphere formation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. To induce definitive endoderm differentiation, cell clusters were incubated in Day (D)1 medium [RPMI (Invitrogen) containing 0.2% FBS, 1:5000 ITS (Invitrogen), 100 ng/ml Activin A, 50 ng/ml WNT3a (R&D Systems)] into low attachment plates. Subsequently cell clusters were differentiated into β-like cells by exposure to the appropriate media as previously published (Russ et al., 2015). All recombinant proteins were purchased from R&D System unless otherwise stated (see Cytokines and Recombinant Proteins Resource Table).

For static GSIS assays, D21 cells (eight to ten clusters, equivalent to ~0.5–1.0 x 106 cells) were rinsed twice with Krebs buffer (129 mM NaCl, 4.8 mM KCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgSO2, 1 mM Na2HPO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 5 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, 0.1% BSA, in deionized water and then sterile filtered) and then preincubated in Krebs buffer for 60 minutes. After preincubation, the cells were incubated in Krebs buffer with 2 mM glucose for 60 minutes (first challenge) and supernatant collected. Then clusters were washed once in Krebs buffer, transferred onto another plate containing fresh Krebs buffer with 20 mM glucose (second challenge) and incubated for additional 60 minutes. Supernatant samples were collected after each incubation period and frozen at −70 °C for human C-peptide ELISA (#10-1141-01; Mercodia) and Insulin (#10-1132-01; Mercodia) measurement.

Pancreatic explants treatment

Dorsal pancreatic buds were microdissected from mouse embryos at E12.5 and cultured for up to 3 days at 37°C in 5% CO2. The day of plating is referred to as day 0. For the α6 Integrin inhibition assay, blocking antibodies were added to the culture medium on day 1 at the indicate concentrations. For rescue experiments, both mouse recombinant SLIT1 [500 ng/mL] and SLIT3 (R&D) [1250 ng/mL] were added to the culture medium on day 1. At the end of the experiment, explants cultures were fixed in 4% PFA, stained as whole-mounts as previously described (Petzold and Spagnoli, 2012).

Immunohistochemistry and in situ hybridization

Mouse embryos and pancreata were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C from 2 hours to overnight. For whole-mount immunostainings fixed mouse embryos were bleached for 1–2 h in 6% hydrogen peroxide solution, incubated in freshly prepared PBSMT blocking solution (2% milk powder, 0.5% TritonX-100 in 1X PBS), and afterwards with primary antibodies at the appropriate dilution overnight at 4°C (see Antibodies Resource Table). After extensive washes in fresh PBSMT solution at least 5–8 times, the embryos were incubated with secondary antibodies at 4°C. Whole mouse embryos from E9.5 onward were cleared in methyl salicylate for confocal microscope imaging. For cryosectioning, samples were equilibrated in 20% sucrose solution and embedded in OCT compound (Sakura). Cryosections (10 μm) were incubated with TSA (Perkin Elmer) blocking buffer for 1 hour at RT and afterwards with primary antibodies at the appropriate dilution (see Reagent Table). If necessary, antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the slides for 20 minutes in citrate buffer (Dako). Hoechst 33342 nuclear counterstaining was used at a concentration of 250 ng/mL. HCS Cell Mask Blue cytoplasmic/nuclear stain (H34558) was used as a cell delineation tool in the morphometric analysis of pancreatic islets. TUNEL staining was performed using the TUNEL Apo-Green Detection Kit (Biotool) after immunofluorescence, following manufacturer instructions.

In situ hybridization on cryosections were performed as described (Rodríguez-Seguel et al., 2013). Antisense Slit3 (gift of F. Bareyre) in situ probe was used. RNAscope in situ hybridisation was performed on cryosections of fixed tissue using the RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 (Advanced Cell Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer instructions. Protease Plus (diluted 1:5) was applied to permeabilise samples for 10 minutes. The Mm-Nkx3-2-C1 (cat#526401) and Mm-Nkx2-5-C2 (cat#428241-C2) probes were used in combination with Opal 520 and Opal 570 fluorophores. Images were acquired on Zeiss AxioObserver, Discovery and Zeiss LSM 700 laser scanning microscope. Zen software was used to create maximum confocal z-projections and Huygens software (SVI) and Imaris Bitplane software were used for 3D volume analysis of confocal z-stacks.

Fluorescent Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) of mouse embryonic cells

E12.5 and E14.5 Nkx2.5-Cre+;Pbx1flox/flox;Pbx2+/−;mT/mG (PbxNkx2.5MES-Δ) embryos and Nkx2.5-Cre+;mT/mG control embryos were dissected using an epifluorescence stereomicroscope (Discovery V12, Zeiss). mT+ dorsal pancreatic region was isolated together with the corresponding mG+ splenopancreatic mesenchymal region, dissociated in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Invitrogen) into single-cell suspensions. To stop the reaction, DMEM (Invitrogen) was added to the cell suspensions and centrifuged at 300g at 4°C, pellets were suspended in PBS/DEPC-treated and filtered through a BD Falcon tube with cell strainer cap (BD 352235). mT+ and mG+ cells were sorted at 4°C using a FACS Aria II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) using GFP and DsRed filters and by setting the gate on the GFP and Tomato fluorescence intensity. Conditions of sorting were as follows: 70-mm nozzle and sheath pressure of 70 psi. Sorted cells were collected directly in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) for RNA extraction. FACS-sorted cells were used for RNA extraction followed by total RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) or RT-qPCR.

GTT and metabolic assays

For the glucose tolerance test (GTT), mice were fastened overnight and blood was collected before and after intraperitoneal injection of glucose (2 g/kg body weight) at 15, 30, 60 and 120 minutes. Blood glucose levels were determined using a glucometer (Contour, Bayer). Plasma insulin concentration from mice was determined by radioimmunoassay kit (#RI-13K, Merck-Millipore). All animal experimentation was conducted in accordance with the local ethics committee (LaGeSO, Berlin, Germany) for animal care.

RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative PCR

Adult and embryonic tissues were dissected and snap-frozen on dry ice and RNA was extracted with Trizol® Reagent (Qiagen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche) was used for RNA extraction from cultured cells. Total RNA was processed for reverse transcription (RT) using Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche). Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using SYBRGreen Master Mix (Roche) or FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix on StepOne Plus cycler machine (Applied Biosystems) or LightCycler 96 system (Roche). Mouse Succinate dehydrogenase (Sdha), 36B4 or human GLYCERALDEHYDE 3-PHOSPHATE DEHYDROGENASE (GAPDH) were used as reference genes. Mouse and Human Primer sequences are provided in Table S2. Gene expression levels were determined by the 2−ΔΔCT method following normalization to reference genes. RT-qPCR experiments were repeated at least three times with independent biological samples; technical triplicates were run for all samples; minus RT and no template controls were included in all experiments.

For RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), total RNA from at least 3000 FACS-sorted cells was extracted with Trizol (Invitrogen) and purified on RNeasy RNA Mini Kit (Qiagen) columns following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was quantified by Agilent RNA 6000 Pico kit (Agilent Technologies). The quality of RNA samples prior to library preparation was determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, and only samples with high RIN (RNA integrity number) scores (>8.5) were further processed. Libraries preparation and sequencing were performed by Otogenetics Corporation Inc. (Atlanta, GA 30360, USA). Briefly, Illumina sequencing libraries from stranded cDNA were sequenced, paired-end, on Illumina HiSeq2500.

Bioinformatics

Transcriptome datasets were mapped against the UCSC mm10 reference annotation mouse genome using Star 2.4.0j (Dobin et al., 2013), analyzed with Cufflinks (2.2.1) for expression level measurement. Comparison of expression level between samples was conducted with Cufflinks.cuffdiff (2.2.1). Gene Ontology (GO) analysis was performed using David website (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (Huang et al., 2009). See also Supplementary Table 1.

The generated E12.5 mouse pancreatic mesenchyme [mG] and epithelial [mT] RNA-Seq data was compared to published data from human fetal pancreas from GSE96697 [PMID:28731406] (Ramond et al., 2017). First, normalized data from the human samples were downloaded from GEO accession number GSE96697 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE96697). From this dataset, human developing pancreas epithelia (GP2+ at 9WD; GSM2538439 and GSM2538440) and developing pancreas mesenchyme (Mesenchyme at 9WD; GSM2538435, GSM2538436, GSM2538437) at nine weeks of development (9WD) stage was compared with the E12.5 mouse pancreas samples. Human genes were matched to the mouse homologues using NCBI Homologene Release 68 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/homologene). In total, 16101 homologous genes were matched between the mouse and human transcriptome datasets. The Spearman correlation coefficient between the rank-order of expression values of cross-species mesenchyme (mouse vs human) was 0.679. A lower correlation coefficient was observed between mouse mesenchyme and human epithelia (Spearman rho = 0.644). These results show that the E12.5 mouse mesenchyme sample is most similar to mesenchyme, rather than epithelia.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

For quantification, the entire pancreas was serially sectioned (10 μm thick). Quantification of immunohistochemical markers focused on dorsal pancreas. The relative area occupied by cells per pancreas was obtained by counting immunopositive cells on every 5th (E12.5), 6th (E14.5) or 8th (E18.5) section, normalized to the total E-cadherin+ epithelium area. For cell counting, positive cells (matching a Hoechst+ nucleus) were manually counted or using Imaris Spot detection function. For Insulin and Glucagon area measurement at E18.5, the positive pixels (surface of section) were quantified using ImageJ software and normalized to the Cell Mask+ pancreatic area. In whole-mount pancreatic explants, the number of Insulin+ or Glucagon+ cells was counted manually and normalized by the average epithelial area (X.Y) multiplied by the number of focal planes analyzed in the explant (Z).

For cell segmentation, the ImarisCell module was applied to segment and analyze pancreatic mesenchyme cells based on mTomato/mGFP membrane staining. Numbers of segmented mGFP+ and mTomato+ cells were used to assess the contribution of Nkx3.2+ or Nkx2.5+ mesenchymal cells to the splenopancreatic mesenchyme, defined as the region surrounding the pancreas and located within the mesothelium border. Overlap between Nkx3.2- or Nkx2.5-descendant cells and the F4/80 macrophage marker membrane staining was also assessed using the ImarisCell module.

For single nuclear fluorescence intensity (FI) quantification, Neurogenin 3 intensity values of cells within each embryo were measured and, subsequently, corrected by linear normalization within each embryo to achieve a uniform dynamic range and improving comparability between embryos. Similarly, expression levels of Islet-1 were assessed by measuring Islet-1 fluorescence intensity within segmented mesenchymal cells.

Experiments were repeated minimum three times; one representative field of view is represented for each staining. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) or mean ± standard errors (s.e.m), as indicated. Sample sizes of at least n=3 were used for statistical analyses except where indicated. All experiments were repeated at least three times. The significance of differences between groups was evaluated using the nonparametric unpaired Mann-Whitney test unless otherwise indicated. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Table S2. List of Primers Used in This Study, Related to STAR Methods Section: “RNA isolation, reverse transcription and quantitative PCR”.

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit anti-AMYLASE (IHC 1:500) | Sigma | Cat #A8273 |

| Rabbit anti-CASPASE3 (IHC 1:300) | Cell Signaling | Cat #9661S |

| Rat anti-CD31 (PECAM-1) (IHC 1:100) | BD | Cat #550274 |

| Rabbit anti-C-PEPTIDE (IHC 1:250) | Cell Signaling | Cat #4593S |

| Rabbit anti-COLLAGEN I (IHC 1:500) | Abcam | Cat #ab34710 |

| Rabbit anti-DESMIN (IHC 1:100) | Cell Signaling | Cat #5332S |

| Rat anti-E-CADHERIN (IHC 1:1000) | Invitrogen | Cat #U3254 |

| Rat anti-F4/80 (IHC 1:100) | BioLegend | Cat #BLD 123101 |

| Rabbit anti-FIBRONECTIN (IHC 1:1000) | gift of Prof. K M. Yamada (NIH, USA) | N/A |

| Chicken anti-GFP (IHC 1:400) | Aves Labs | Cat #GFP-1020 |

| Rabbit anti-GLUCAGON (IHC 1:500) | Immunostar Inc. | Cat #20076 |

| Goat anti-GLUT2 (IHC 1:200) | Santa Cruz | Cat #sc-7580 |

| Guinea pig anti-INSULIN (IHC 1:400) | Invitrogen | Cat #PA1-26938 |

| Rat anti-INTEGRIN α6 (CD49f, VLA-6) (IHC 1:400) | Millipore | Cat #MAB1378 |

| Mouse anti-ISLET-1 (IHC 1:100) | Hybridoma Bank | Cat #39.4D5 |

| Rabbit anti-LAMININ (IHC 1:1000) | Sigma | Cat #L9393 |

| Rabbit anti-MAFA (IHC 1:500) | Abcam | Cat #ab26405 |

| Armenian hamster anti-MUCIN (IHC 1:500) | Thermo Scientific | Cat #HM-1630-P1 |

| Guinea pig anti-NEUROGENIN3 (IHC 1:400) | Millipore | Cat #AB10536 |

| Goat anti-NEUROGENIN3 (IHC 1:1200) | BCBC | Cat #AB2774 |

| Rabbit anti-NEUROD1 (IHC 1:800) | Abcam | Cat #ab213725 |

| Mouse anti-NKX6.1 (IHC 1:250) | Hybridoma Bank | Cat #F55A10 |

| Rabbit anti-PAX6 (IHC 1:500) | Covance | Cat #PRB-278P |

| Guinea pig anti-PDX1 (IHC 1:500) | Abcam | Cat #ab47308 |

| Rabbit anti-PDGFRb (IHC 1:500) | Abcam | Cat #ab32570 |

| Mouse anti-PHOSPHO-HISTONE H3 (Ser10) (IHC 1:100) | Cell Signaling | Cat #9706 |

| Rabbit anti-PHOSPHO-HISTONE H3 (Ser10) (IHC 1:200) | Millipore | Cat #06-570 |

| Rabbit anti-PBX1 (IHC 1:400) | Cell Signaling | Cat #4342 |

| Rabbit anti-PROX1 (IHC 1:200) | RELIATech GmbH | Cat #102-PA32S |

| RAT anti-RFP (IHC 1:400) | Chromotek | Cat #ABIN334653 |

| Rabbit anti-VIMENTIN (IHC 1:100) | Cell Signaling | Cat #5741S |

| Goat Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Anti-Chicken IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A11039 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Anti-Goat IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A11055 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 594-labeled Anti-Goat IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A11058 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (IHC 1:750) | Dianova | Cat #706-545-148 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 647-labeled Anti-Guinea Pig IgG (IHC 1:750) | Dianova | Cat #706-605-148 |

| Goat DyLight 649-labeled Anti-Armenian Hamster IgG (IHC 1:750) | Dianova | Cat #127-495-099 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 594-labeled Anti-Mouse IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A21203 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 647-labeled Anti-Mouse IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A31571 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Anti-Rabbit IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A21206 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 594-labeled Anti-Rabbit IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A21207 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 647-labeled Anti-Rabbit IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A31573 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 488-labeled Anti-Rat IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A21208 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 594-labeled Anti-Rat IgG (IHC 1:750) | Invitrogen | Cat #A21209 |

| Donkey Alexa Fluor 647-labeled Anti-Rat IgG (IHC 1:750) | Dianova | Cat #712-605-153 |

| Biological Samples | ||

| Gastrointestinal tract dissected from mouse embryos and adults at different stages | This paper | N/A |

| Pancreatic explants from E12.5 mouse embryos | This paper | N/A |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| ALK5 Inhibitor II | Enzo Life Sciences | Cat #ALX-270-445-M001 |

| CTSTM B-27® Supplement, XenoFree (100X) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat #A1486701 |

| Hoechst 33342 (250 ng/mL) | Invitrogen | Cat #H1399 |

| HCS Cell Mask Blue (2μg/mL) | Invitrogen | Cat #H32720 |

| ITS, Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium Supplement (100X) | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat #41400-045 |

| LDN-193189 BMP inhibitor | Tebu-Bio | Cat #24804-0074 |

| Recombinant Human EGF | R&D Systems | Cat #236-EG-200 |

| Recombinant Human Heregulinβ-1 | Peprotech | Cat #100-03-10 |

| Recombinant Human KGF/FGF-7 Protein | R&D Systems | Cat #251-KG-050 |

| Recombinant Human/Mouse/Rat Activin A Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat #338-AC-050/CF |

| Recombinant Human Slit3 Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat #9067-SL-050 |

| Recombinant Human Wnt-3a Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat #5036-WN-010/CF |

| Recombinant Mouse Slit1 Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat #5199-SL-050 |

| Recombinant Mouse Slit3 Protein, CF | R&D Systems | Cat #9296-SL-050 |

| Rock Inhibitor Y-27632 | Sigma | Cat #SCM075 |

| TBP, α-Amyloid Precursor Protein Modulator - CAS 497259-23-1 - Calbiochem | Millipore | Cat #565740-1MG |

| TGF-β RI Kinase Inhibitor IV | Millipore UK Ltd | Cat #616454-2MG |

| TTNPB, stable retinoid analog | Sigma | Cat #T3757-10MG |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| FastStart Essential DNA Green Master Mix | Roche | Cat #06924204001 |

| High Pure RNA Isolation Kit | Roche | Cat #11828665001 |

| Human C-peptide ELISA kit | Mercodia | Cat #10-1141-01 |

| Human Insulin ELISA kit | Mercodia | Cat #10-1132-01 |

| RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent Reagent Kit v2 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | various |

| Radioimmunoassay kit | Merck-Millipore | Cat #RI-13K |

| SYBRGreen Master Mix | Sigma Aldrich Co Ltd | Cat #4913914001 |

| Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit | Roche | Cat #04379012001 |

| TUNEL Apo-Green Detection Kit | Biotool | Cat #B31115 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| RNAseq data from mouse pancreatic epithelial and mesenchymal populations | This paper | GEO accession number: GSE123759 |

| Transcriptome from human fetal pancreas | Ramond et al., 2017 | GEO accession number: GSE96697 |

| Experimental Models: Cell Lines | ||

| BIHi043-A (XM001) | Wang et al., 2018 | N/A |

| BIHi005-A | Berlin Institute of Health, Germany | N/A |

| Experimental Models: Organisms/Strains | ||

| Mouse: Nxk2.5-Cre | Stanley et al., 2002 | Nkx2-5tm2(cre)Rph |

| Mouse: Nxk3.2-Cre | Verzi et al., 2009 | Nkx3-2tm1(cre)We |

| Mouse: Pdx1-Cre | Hingorani et al., 2003 | B6.FVB-Tg(Ipf1-cre)1Tuv |

| Mouse: Pbx1flox/flox | Koss et al., 2012 | Pbx1tm2Mlc |

| Mouse: Pbx2 −/− | Selleri et al., 2004 | Pbx2tm1Mlc |

| Mouse: R26R-mTmG | Muzumdar et al., 2007 | B6.129(Cg)-Gt(ROSA)26Sortm4(ACTB-tdTomato,-EGFP)Luo/J |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Antisense I Slit3 for ISH | Gift of F. Bareyre (LMU, Munich, Germany) | N/A |

| Human primers for RT-qPCR | This paper | See Table S2 |

| Mouse primers for RT-qPCR | This paper | See Table S2 |

| RNAscope Probe-Mm-Nkx3-2-C1 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat #526401 |

| RNAscope Probe-Mm- Nkx2-5-C2 | Advanced Cell Diagnostics | Cat #428241-C2 |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| Cufflinks (2.2.1) | Trapnell lab | RRID:SCR_014597 |

| DAVID GO analysis | Huang et al., 2009 | RRID:SCR_001881 |

| GraphPad Prism 7 | GraphPad | RRID:SCR_002798 |

| ImageJ 1.53 | ImageJ | RRID:SCR_003070 |

| Imaris version 9.5 | BitPlane | RRID:SCR_007370 |

| R | N/A | RRID:SCR_001905 |

| Star 2.4.0j | Dobin et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Zen Digital Imaging for Light Microscopy | Carl Zeiss AG | RRID:SCR_013672 |

| Huygens software (SVI) | SVI | RRID:SCR_014237 |

HIGHLIGHTS.

Identification of functional heterogeneity within the pancreatic mesenchyme

Nkx2.5 marks a mesenchymal population in the embryonic pancreas

Pbx1 acts as a regulator of the Nkx2.5+ mesenchyme defining a pro-endocrine niche

Pbx non-cell autonomously controls endocrine differentiation via ECM and guidance cues

Acknowledgments.

We thank all the members of the Spagnoli laboratory for their useful comments and suggestions on the study. We thank Matthew Koss and Julia Kofent for initial contribution to the project and Heike Naumann for technical help. We thank W. Zimmer (Texas A&M Health Science Center, USA) for sharing the Nkx3.2-Cre transgenic mouse strain, R. Harvey (VCCRI, Australia) for the Nkx2.5-Cre transgenic mouse strain and H. Lickert (Helmholtz Center, Munich, Germany) for the XM001 iPSC line. We thank F. Bareyre (LMU, Munich, Germany) for the Slit 3 plasmid and Kenneth M. Yamada (NIH, USA) for the antibody against Fibronectin. This research was supported by funds from the Helmholtz Association. The F.M.S. lab. was supported by the ERC-POC (TheLiRep #641036), EFSD/AZ, JDRF Innovative (1-INO-2018-634-A-N). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme Pan3DP FET Open, EU Horizon 2020 grant agreement No 800981. L.S. was supported by the NIH R01 HD061403 grant.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests. Authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams MT, Gilbert JM, Hinojosa Paiz J, Bowman FM, and Blum B (2018). Endocrine cell type sorting and mature architecture in the islets of Langerhans require expression of Roundabout receptors in β cells. Scientific Reports 8, 10876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahlgren U, Pfaff SL, Jessell TM, Edlund T, and Edlund H (1997). Independent requirement for ISL1 in formation of pancreatic mesenchyme and islet cells. Nature 385, 257–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelo JR, and Tremblay KD (2018). Identification and fate mapping of the pancreatic mesenchyme. Developmental Biology 435, 15–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artner I, Hang Y, Mazur M, Yamamoto T, Guo M, Lindner J, Magnuson MA, and Stein R (2010). MafA and MafB regulate genes critical to beta-cells in a unique temporal manner. Diabetes 59, 2530–2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asayesh A, Sharpe J, Watson RP, Hecksher-Sørensen J, Hastie ND, Hill RE, and Ahlgren U (2006). Spleen versus pancreas: strict control of organ interrelationship revealed by analyses of Bapx1−/− mice. Genes Dev 20, 2208–2213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attali M, Stetsyuk V, Basmaciogullari A, Aiello V, Zanta-Boussif MA, Duvillie B, and Scharfmann R (2007). Control of β-Cell Differentiation by the Pancreatic Mesenchyme. Diabetes 56, 1248–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizoglu DB, and Cleaver O (2016). Blood vessel crosstalk during organogenesis—focus on pancreas and endothelial cells. Dev Biol 5, 598–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankaitis ED, Bechard ME, and Wright CV (2015). Feedback control of growth, differentiation, and morphogenesis of pancreatic endocrine progenitors in an epithelial plexus niche. Genes Dev 29, 2203–2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhushan A, Itoh N, Kato S, Thiery JP, Czernichow P, Bellusci S, and Scharfmann R (2001). Fgf10 is essential for maintaining the proliferative capacity of epithelial progenitor cells during early pancreatic organogenesis. Development 128, 5109–5117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes L, Wong D, Subramaniam M, Meyer N, Gilchrist C, Knox S, Tward A, Ye C, and Sneddon J (2018). Lineage dynamics of murine pancreatic development at single-cell resolution. Nat Commun 9, 3922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagnaro L, Lenti E, Maruzzelli S, Spinardi L, Migliori E, Farinello D, Sitia G, Harrelson Z, Evans Sylvia M., Guidotti Luca G., et al. (2013). Nkx2-5+/Islet1+ Mesenchymal Precursors Generate Distinct Spleen Stromal Cell Subsets and Participate in Restoring Stromal Network Integrity. Immunity 38, 782–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli V, Beattie GM, Klier G, Ellisman M, Ricordi C, Quaranta V, Frasier F, Ishii JK, Hayek A, and Salomon DR (2000). Expression and Function of αvβ3 and αvβ5 Integrins in the Developing Pancreas. The Journal of Cell Biology 150, 1445–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisera CA, Kadison AS, Breslow GD, Maldonado TS, Longaker MT, and Gittes GK (2000). Expression and role of laminin-1 in mouse pancreatic organogenesis. Diabetes 49, 936–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis C, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, and Gingeras T (2013). STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efrat S (2019). Beta-Cell Dedifferentiation in Type 2 Diabetes: Concise Review. STEM CELLS 37, 1267–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escot S, Willnow D, Naumann H, Di Francescantonio S, and Spagnoli FM (2018). Robo signalling controls pancreatic progenitor identity by regulating Tead transcription factors. Nat Commun 9, 5082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner B, Carrano AC, and Sander M (2019). Human stem cell models: lessons for pancreatic development and disease. Genes Dev 33, 1475–1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geutskens SB, Otonkoski T, Pulkkinen MA, Drexhage HA, and Leenen PJ (2005). Macrophages in the murine pancreas and their involvement in fetal endocrine development in vitro. Journal of leukocyte biology 78, 845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittes GK, Galante PE, Hanahan D, Rutter WJ, and Debase HT (1996). Lineage-specific morphogenesis in the developing pancreas: role of mesenchymal factors. Development 122, 439–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golosow N, and Grobstein C (1962). Epitheliomesenchymal interaction in pancreatic morphogenesis. Dev Biol 4, 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari N, Sakhneny L, Khalifa-Malka L, Busch A, Hertel KJ, Hebrok M, and Landsman L (2019). Pancreatic pericytes originate from the embryonic pancreatic mesenchyme. Dev Biol 449, 14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecksher-Sørensen J, Watson RP, Lettice LA, Serup P, Eley L, Angelis CD, Ahlgren U, and Hill RE (2004). The splanchnic mesodermal plate directs spleen and pancreatic laterality, and is regulated by Bapx1/Nkx3.2. Development 131, 4665–4675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heymans C, Degosserie J, Spourquet C, and Pierreux CE (2019). Pancreatic acinar differentiation is guided by differential laminin deposition. Sci Rep 9, 2711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani S, Petricoin E, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz M, Ross S, Conrads T, Veenstra T, Hitt B, et al. (2003). Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell 4, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton ER, Humphries JD, James J, Jones MC, Askari JA, and Humphries MJ (2016). The integrin adhesome network at a glance. J Cell Science 129, 4159–4163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D, Sherman B, and Lempicki R (2009). Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID Bioinformatics Resources. Nat Protoc 4, 44–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries JD, Chastney MR, Askari JA, and Humphries MJ (2019). Signal transduction via integrin adhesion complexes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 56, 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, Selleri L, Lee JS, Zhang AY, Gu X, Jacobs Y, and Cleary ML (2002). Pbx1 inactivation disrupts pancreas development and in Ipf1-deficient mice promotes diabetes mellitus. Nat Genet 30, 430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss M, Bolze A, Brendolan A, Saggese M, Capellini Terence D., Bojilova E, Boisson B, Prall Owen W.J., Elliott DA, Solloway M, et al. (2012). Congenital Asplenia in Mice and Humans with Mutations in a Pbx/Nkx2-5/p15 Module. Dev Cell 22, 913–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander AD, Kimble J, Clevers H, Fuchs E, Montarras D, Buckingham M, Calof AL, Trumpp A, and Oskarsson T (2012). What does the concept of the stem cell niche really mean today? BMC biology 10, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landsman L, Nijagal A, Whitchurch TJ, VanderLaan RL, Zimmer WE, MacKenzie TC, and Hebrok M (2011). Pancreatic Mesenchyme Regulates Epithelial Organogenesis throughout Development. PLOS Biol 9, e1001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen BM, Hrycaj SM, Newman M, Li Y, and Wellik DM (2015). Mesenchymal Hox6 function is required for mouse pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation. Development 142, 3859–3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen H, and Grapin-Botton A (2017). The molecular and morphogenetic basis of pancreas organogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol 66, 51–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamidi A, Prawiro C, Seymour PA, de Lichtenberg KH, Jackson A, Serup P, and Semb H (2018). Mechanosignalling via integrins directs fate decisions of pancreatic progenitors. Nature 564, 114–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastracci TL, Anderson KR, Papizan JB, and Sussel L (2013). Regulation of Neurod1 contributes to the lineage potential of Neurogenin3+ endocrine precursor cells in the pancreas. PLoS Genet 9, e1003278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar M, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, and Luo L (2007). A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis 45, 593–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan FC, and Wright C (2011). Pancreas organogenesis: From bud to plexus to gland. Developmental Dynamics 240, 530–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petzold KM, and Spagnoli FM (2012). A system for ex vivo culturing of embryonic pancreas. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, e3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierreux CE, Cordi S, Hick A-C, Achouri Y, Ruiz de Almodovar C, Prévot P-P, Courtoy PJ, Carmeliet P, and Lemaigre FP (2010). Epithelial: Endothelial cross-talk regulates exocrine differentiation in developing pancreas. Dev Biol 347, 216–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinho AV, Van Bulck M, Chantrill L, Arshi M, Sklyarova T, Herrmann D, Vennin C, Gallego-Ortega D, Mawson A, Giry-Laterriere M, et al. (2018). ROBO2 is a stroma suppressor gene in the pancreas and acts via TGF-beta signalling. Nat Commun 9, 5083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramond C, Glaser N, Berthault C, Ameri J, Kirkegaard JS, Hansson M, Honoré C, Semb H, and Scharfmann R (2017). Reconstructing human pancreatic differentiation by mapping specific cell populations during development. eLife 6, e27564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Seguel E, Mah N, Naumann H, Pongrac IM, Cerdá-Esteban N, Fontaine J-F, Wang Y, Chen W, Andrade-Navarro MA, and Spagnoli FM (2013). Mutually exclusive signaling signatures define the hepatic and pancreatic progenitor cell lineage divergence. Genes Dev 27, 1932–1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romer AI, Singer RA, Sui L, Egli D, and Sussel L (2019). Murine Perinatal β-Cell Proliferation and the Differentiation of Human Stem Cell–Derived Insulin-Expressing Cells Require NEUROD1. Diabetes 68, 2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russ HA, Parent AV, Ringler JJ, Hennings TG, Nair GG, Shveygert M, Guo T, Puri S, Haataja L, Cirulli V, et al. (2015). Controlled induction of human pancreatic progenitors produces functional beta-like cells in vitro. The EMBO Journal 34, 1759–1772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]