Abstract

Introduction

The progression rate of Alzheimer's disease (AD) varies and might be affected by the triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells (TREM2) activity. We explored if cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) soluble TREM2 (sTREM2), a proxy of microglial activity, is associated with clinical progression rate.

Methods

Patients with clinical AD (N = 231) were followed for up to 3 years after diagnosis. Cognitively healthy controls (N = 42) were followed for 5 years. CSF sTREM2 was analyzed by enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay. Group‐based trajectory modeling revealed distinct clinical progression groups.

Results

Higher CSF sTREM2 was associated with slow clinical progression. The slow‐ and medium‐progressing groups had higher CSF sTREM2 than the cognitively healthy, who had a similar level to patients with rapid clinical progression.

Discussion

CSF sTREM2 levels were associated with clinical progression in AD, regardless of core biomarkers. This could be useful in assessing disease development in relation to patient care and clinical trial recruitment.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, Clinical Dementia Rating scale, disease progression, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (sTREM2), trajectories

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is biologically defined by brain amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques (A), neurofibrillary tangles (T), and neurodegeneration (N). 1 , 2 However, patients who meet the clinical criteria of an AD diagnosis 3 may develop ATN‐biomarker changes in different chronological order, 2 , 4 and may display different clinical symptoms and disease progression rates. 3 , 5 , 6 , 7 Understanding the course of cognitive‐ and functional decline among AD patients is important for providing information about prognosis, informing policy makers, recruiting patients to medical trials, and assessing drug efficacy. Neuroinflammation in AD pathology has attracted much interest in recent years. 8 In particular, the innate immune receptor triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2) has received special attention 9 , 10 as TREM2 variants increase the risk of AD, 11 , 12 , 13 other dementias, 14 , 15 , 16 and possibly other neurodegenerative diseases. 15

In the brain, TREM2 is predominantly expressed by microglia, 10 the resident macrophages of the central nervous system. TREM2 function is not fully understood, but it seems to include phagocytosis; modulation of inflammatory signaling; and microglial proliferation, survival, and migration. 17 In AD, TREM2 binds Aβ oligomers 18 and provides transit to a neurodegenerative phenotype, defined as disease‐associated microglia (DAM) 19 or microglial neurodegenerative (MgND) phenotype. 20 The TREM2 variants that increase AD risk 12 , 13 appear to be loss of function, as indicated by increased amyloid seeding, 21 suggesting a protective role of microglia. 17 , 21 , 22 Soluble TREM2 (sTREM2), an ectodomain part of TREM2, is discharged in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) 23 and is often used as a proxy to measure TREM2 and microglia activity.

Associations between CSF sTREM2, total tau (t‐tau), and phosphorylated tau181 (p‐tau) indicate that increased sTREM2 denotes microglial responses to tauopathy and the first signs of neurodegeneration. 24 , 25 , 26 However, this response is not AD‐specific. 27 , 28 In AD, the CSF level of sTREM2 seems to change during the course of the disease, with several studies showing a peak in the early symptomatic stage of sporadic, 24 , 25 , 29 and dominantly inherited AD. 25 Studies comparing CSF sTREM2 between AD patients and cognitively healthy controls have been contradictory. 22 , 24 , 27 , 29 , 30 Recently our research group found that CSF sTREM2 was associated with tauopathy, but not with CSF Aβ level, and that CSF sTREM2 could not discriminate the AD clinical stage (mild cognitive impairment [MCI] or dementia). 31 Interestingly, high CSF sTREM2 was recently linked to a decreased rate of memory decline in biologically defined AD patients. 32

In the present study, we explored the association between CSF sTREM2 and clinical progression rate in patients with clinical AD (MCI or dementia), who were followed for up to 3 years after diagnosis. Moreover, we compared the level of sTREM2 between the patients and cognitively healthy controls. We hypothesized that a high baseline level of CSF sTREM2 would be related to slow clinical progression in AD patients, due to its potential protective role, and that the sTREM2 level would be lower among the cognitively healthy controls.

HIGHLIGHTS

Higher cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (sTREM2) was associated with slower clinical progression in Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Patients with rapid progression had low CSF sTREM2 comparable to the cognitively healthy.

CSF sTREM2 could be a biomarker for AD progression.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

Systematic Review: Using PubMed, the authors searched the literature with a combination of the keywords “Alzheimer's disease,” “progression,” “trajectories,” “triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM2),” and “soluble TREM2 (sTREM2).” The importance of neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease (AD) is becoming evident; particularly, the microglial‐associated TREM2 is gaining interest. Few studies examine how microglial activity relates to the clinical progression of AD.

Interpretation: Microglial activity, measured by cerebrospinal fluid sTREM2, was associated with clinical progression, irrespective of AD core biomarkers; a higher level was protective in clinical AD.

Future directions: Microglial state biology, including TREM2‐activity, could be a target for disease‐modifying therapy, especially in the early stages of AD. Replication studies should be conducted in other patient cohorts and should combine methods, like bead or array‐based microglial fluid marker analyses, to discriminate between beneficial and harmful states of microglia.

2. METHODS

The current study followed 231 patients from two Norwegian memory clinics (140 patients from Oslo University Hospital [OUH] and 91 patients from St. Olav Hospital, University Hospital of Trondheim), along with 42 cognitively healthy controls from OUH and Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo. All participants and their next of kin signed an informed consent form. The study was approved by the regional Ethics Committee for medical research in the South‐East of Norway (REK2011/2052 and REK2017/371). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration.

2.1. Memory clinic patients, inclusion, and assessments

We included patients who met the clinical criteria of MCI (N = 37) or dementia (N = 194) due to AD, who underwent a lumbar puncture and received at least one follow‐up examination with the Clinical Dementia Rating scale (CDR) 33 after baseline. All patients underwent their first examination as part of the standard clinical practice between June 2009 and September 2016, following a comprehensive and uniform research protocol. 34 Clinical diagnoses of AD‐MCI, AD‐dementia, or AD‐dementia etiologically mixed presentation were made post hoc by the researchers, following the diagnostic criteria of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association. 3 , 35 We included patients regardless of their ATN classification, 1 because sTREM2 levels can increase independently of amyloidosis 24 , 36 and because patients fulfilling the clinical criteria of AD do not always follow the typical sequential order of A‐T‐N pathological core biomarkers appearance. 4 The patients underwent a battery of standardized cognitive tests, 34 among others including the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE; 0–30; lower values indicate greater cognitive impairment), the Clock Drawing Test (with pathological cut‐off ≤3/5 points), and the Trail Making Tests A and B (based on age‐adjusted cut‐off of –2 standard deviations [SD]). Patients also underwent a physical examination, blood sampling, a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping by the Illumina Infinium OmniExpress v1.1 chip at deCODE Genetics (Reykjavik, Iceland).

2.2. Cognitively healthy controls, recruitment, and assessments

The cognitively healthy controls were recruited after elective gynecological, orthopedic, or urological surgery. All underwent spinal anesthesia, and CSF was collected before the anesthetic was given. Detailed information about this cohort has been previously published. 37 The clinical examination, cognitive testing, 34 and APOE genotyping were performed in the same way as with the memory clinic patients (section 2.1). The analysis only included those with normal cognitive test results (in line with age‐ and education‐adjusted norms) at baseline, who did not show pathological levels of Aβ1‐42 (Aβ42) or p‐tau, and who did not experience cognitive decline (<1 SD decline in test results) within 5 years (N = 42).

2.3. CSF AD core biomarker measurements

CSF AD core biomarkers were analyzed by INNOTEST enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) (Fujirebio, Ghent, Belgium). The CSF samples of the patients were analyzed at the Akershus University laboratory, using non‐pathological cut‐offs: Aβ42 > 700 pg/mL and p‐tau < 80 pg/mL. Age‐adjusted cut‐offs for t‐tau were < 300 pg/mL for persons < 50 years, < 450 pg/mL for persons 50–70 years, and < 500 pg/mL for persons > 70 years. The CSF samples of the cognitively healthy were analyzed at the Sahlgrenska University Hospital laboratory, using non‐pathological cut‐offs: Aβ42 > 530 pg/mL, p‐tau < 60 pg/mL, and t‐tau < 350 pg/mL. 38

2.4. CSF sTREM2 measurements

CSF sTREM2 levels were determined by ELISA at the University of Oslo, as previously described. 30 To summarize, plates were coated with an anti‐humanTREM2 polyclonal antibody (AF1828, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA), and TREM2 was detected with a monoclonal mouse anti‐human TREM2 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated antibody (SEK11084, Sino Biologics, Beijing, China). The samples were analyzed in duplicate. Two CSF samples were used as internal standards to control for inter‐day variability.

2.5. Marker of clinical progression: The Clinical Dementia Rating scale

To measure cognitive and functional impairment, researchers (certified CDR raters) scored the patients’ CDRs post hoc for every visit, using all available information from the clinical records. In the cognitively healthy controls, CDR was scored at the 5‐year follow‐up examination. The categories memory, orientation, judgment and problem‐solving, community affairs, home and hobbies, and personal care were given a score of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, or 3, based on the severity of the impairment. 39 The different CDR items were then summed to create the continuous CDR Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SB; 0–18; higher scores indicate more severe cognitive and functional impairment). 40 , 41 For the patients, the clinical evaluation closest to the spinal tap was considered the baseline (mean 61 days [SD 66]). If more than 200 days elapsed between the clinical evaluation and the spinal tap (N = 2), the average of the two closest CDR‐SB examinations were chosen. To limit effects of survival bias, we restricted the follow‐up in the present study to 3 years.

2.6. Statistical analyses

Analyses were performed using Stata/IC 15.1 (StataCorpLLC 2018, Stata Statistical Software, revision 17 December 2018, College Station, Texas, USA). Continuous descriptive variables were compared using Student's t test or Kruskal‐Wallis test. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson's χ2. It was ensured that a Spearman's inter‐correlation between the variables was ≤0.6.

2.6.1. Clinical trajectory modeling

In the search of distinct developmental trajectory groups of patients’ clinical progression (based on change in CDR‐SB over time), we applied group‐based trajectory modeling, 42 using the Stata package traj. 43 AD develops over years, and the time from symptom debut to cognitive assessment varies, 44 making it especially difficult to set a common starting point. The advantage of group‐based trajectory modeling is that it uses the variation in the data as a statistical tool to group those with similar development, without constructing categories a priori, allowing the groups to have different starting points and course of development. 42 The number and shapes of the trajectory groups were decided, following Nagin and Odgers's 42 recommendations, by testing the number of groups best representing the heterogeneity in our data, ensuring clinical usefulness, and class size. The goodness‐of‐fit was estimated using Bayesian information criterion (closer to zero indicates better fit); the posterior probability of group membership was ≥0.7, and the odds of correct classification was at least five in each group. We also visually confirmed that no overlapping confidence intervals occurred between the trajectory groups.

2.6.2. Multiple logistic regression analyses

The association between CSF sTREM2 and clinical progression was assessed through multiple logistic regression models, with the trajectory groups as the outcome variable. In the selection of covariates, we applied clinical judgment along with a six‐step approach of reducing bias through directed acyclic graph (DAG), 45 aided by the DAGitty v.3.0 software (Figure S1 in supporting information). Because t‐tau was highly correlated with p‐tau (Spearman's rho 0.85), and the MRI examinations were conducted at multiple different centers with varying protocols, the level of neurodegeneration was not included in the analyses. In the first model we assessed whether CSF sTREM2, at a given age and level of Aβ42‐ and p‐tau, was associated with the clinical progression rate in patients with AD (MCI or dementia). To compare the effect size of the CSF biomarkers, we performed the same model using the standardized values of sTREM2, Aβ42, and p‐tau. We adjusted for clinical stage (MMSE), sex, and education in a sensitivity analysis.

In the second model, we assessed whether the CSF sTREM2 level of cognitively healthy controls was different from the level detected in the trajectory groups of clinical progression (of AD) at any given age. As the cognitively healthy all were A–T– (as judged by the CSF values), and the core biomarkers were analyzed at different laboratories, the CSF Aβ42‐ and p‐tau levels were not included in this model. Again, we adjusted for sex, education, and MMSE in the sensitivity analysis. The level of significance was set at P value ≤.05.

3. RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of all patients, the three trajectory groups, and the cognitively healthy control group. Within the 3‐year follow‐up period, the patients received 3.0 (SD 1.2) clinical examinations.

TABLE 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the patients and the cognitively healthy controls

| AD patients | Cognitively healthy | AD patients vs cognitively healthy | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |||

| Variables | N = 231 | N = 118 | N = 63 | N = 50 | N = 42 | P value |

| Age | 69.8 (6.5) | 69.8 (6.7) | 69.4 (6.8) | 70.6 (5.8) | 71.2 (5.5) | 0.22 |

| Female | 133 (57.6) | 72 (61.0) | 32 (50.8) | 29 (58.0) | 25 (59.5) | 0.04 |

| Education | 12.3 (3.6) | 12.7 (3.6) | 12.4 (3.6) | 11.0 (3.2) | 15.5 (3.1) | < .001 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| ‐ AD‐MCI | 37 (16.0) | 34 (28.8) | 2 (3.2) | 1 (2.0) | : | : |

| ‐ AD‐dementia | 143 (61.9) | 64 (54.2) | 50 (79.4) | 29 (58.0) | : | : |

| ‐ AD mixed with cerebrovascular disease | 51 (22.1) | 20 (17.0) | 11 (17.5) | 20 (40.0) | : | : |

| APOE Ɛ4 positive † | 157 (75.8) | 81 (74.3) | 42 (76.4) | 34 (73.9) | 12 (29.3) | < .001 |

| MMSE | 23.3 (4.4) | 25.4 (3.2) | 22.5 (3.1) | 19.2 (5.1) | 29.1 (1.1) | < .001 § |

| TMT‐A better than – 2 SD | 138 (64.5) | 91 (80.5) | 29 (50.0) | 18 (41.9) | 38 (90.5) | 0.001 |

| TMT‐B better than – 2 SD | 91 (45.1) | 71 (64.6) | 16 (30.8) | 4 (10.0) | 38 (90.5) | < .001 |

| CDT ≥ 4/5 points | 114 (50.9) | 80 (70.2) | 23 (37.7) | 11 (22.5) | 41 (97.6) | < .001 |

| CSF sTREM2 (ng/mL) | 9.4 (4.6) | 9.9 (4.8) | 9.4 (4.8) | 8.3 (3.4) | 8.0 (2.7) | < .001 |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 557 (158) | 574 (168) | 545 (138) | 533 (157) | 786 (127) | ¶ |

| CSF total tau (pg/mL) | 730 (365) | 694 (318) | 722 (357) | 826 (458) | 287 (58) | ¶ |

| CSF phosphorylated tau (pg/mL) | 90.9 (37.1) | 88.7 (33.9) | 89.3 (38.0) | 97.9 (42.7) | 49.2 (7.8) | ¶ |

| AT classification | ||||||

| ‐ A+T+ | 125 (54.1) | 64 (54.2) | 33 (52.4) | 28 (56.0) | 0 (0.0) | # |

| ‐ A+T– | 71 (30.7) | 35 (29.7) | 20 (31.8) | 16 (32.0) | 0 (0.0) | :: |

| ‐ A–T+ | 16 (6.9) | 7 (5.9) | 5 (7.9) | 4 (8.0) | 0 (0.0) | †† |

| ‐ A–T– | 19 (8.2) | 12 (10.2) | 5 (7.9) | 2 (4.0) | 42 (100) | ‡‡ |

| CDR‐SB | 4.3 (2.4) | 3.0 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.5) | 7.0 (2.7) | 0.1 (0.2) ‡ | : |

| CDR‐SB annual change | 1.2 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 3.5 | : | : |

NOTE. Data are presented as N (%) and mean (SD). Independent t‐tests were used to compare the means, and proportions were compared using Pearson's χ2 tests unless otherwise specified.

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; AD, Alzheimer's disease; APOE Ɛ4, apolipoprotein Ɛ4 allele; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale; CDT, Clock Drawing Test; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE, Mini‐Mental State Examination; N, number; SB, Sum of Boxes; SD, standard deviation; sTREM2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2; TMT, Trail Making Test.

Not applicable.

Missing in 22.

After 5 years of follow‐up.

Kruskal–Wallis test applied.

Comparison was not possible due to difference in cut‐offs.

Pearson's χ2 between the AD patient groups yielded P = .928.

Pearson's χ2 between the AD patient groups yielded P = .936.

Pearson's χ2 between the AD patient groups yielded P = .831.

Pearson's χ2 between the AD patient groups yielded P = .411.

3.1. Trajectory groups

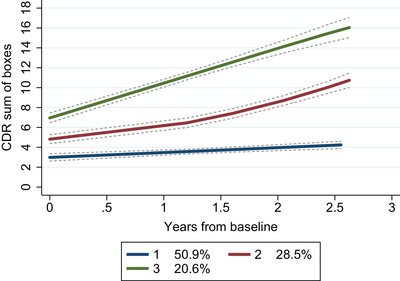

There were 3 distinct trajectories of cognitive‐ and functional decline (change in CDR‐SB; Figure 1). Table S1 in supporting information shows the trajectory class enumeration. Three classes were chosen to provide the best fitting shape, because four trajectory classes caused one group to be very small (11 patients). Group 1 (slow clinical progression; N = 118 [50.9%]) had a mean CDR‐SB of 3.0 (SD 1.2) at baseline and progressed the slowest (CDR‐SB annual change of 0.5). Group 2 (medium clinical progression; N = 63 [28.5%]) had a mean baseline CDR‐SB of 4.8 (SD 1.5) and progressed more rapidly with an annual change of 2.4. Group 3 (rapid clinical progression; N = 50 [20.6%]) had the worst CDR‐SB at baseline (mean CDR‐SB 7.0 [SD 2.7]) and progressed quickly (CDR‐SB annual change of 3.5). The percentage of patients in each group was based on the maximum probability assignment rule; therefore, they differ slightly from the estimated group probability. 42

FIGURE 1.

Trajectory groups of the patients based on change in Clinical Dementia Rating scale. Note: Group‐based trajectory modeling, with the trajectory shapes 1 2 1 (1 = linear‐ and 2 = quadratic shape). Group 1 (blue); number of patients (N) = 118, posterior probability of group membership = 0.94 and odds of correct classification = 15.2. Group 2 (red); N = 63, posterior probability of group membership = 0.86 and odds of correct classification = 17.0. Group 3 (green); N = 50, posterior probability of group membership = 0.91 and odds of correct classification = 37.6. The stippled lines denote the confidence intervals of the trajectory groups. Percentages are proportion of the patient population based on the maximum probability assignment rule. Abbreviation: CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating scale.

3.2. The association of CSF sTREM2 with clinical progression

Higher CSF sTREM2 at baseline decreased the likelihood of belonging to the rapid clinical progression group (Group 3; relative risk ratio [RRR] 0.85 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 0.94]). This was found after adjusting for age and continuous level of CSF Aβ42 and p‐tau, using the slow clinical progression group (Group 1) as reference (Table 2). Rapid clinical progression was more likely with higher CSF p‐tau (RRR 1.01 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.02]). Interestingly, repeating the analysis with standardized values to allow comparison of the effect sizes showed a larger effect size of sTREM2 (RRR = 1/0.49 = 2.04) compared to p‐tau (RRR 1.65). In the sensitivity analysis, in which we adjusted for sex, clinical stage (MMSE), education, and concentrations of CSF Aβ42 and p‐tau, the decreased risk of belonging to the rapid clinical progression group (Group 3) with higher levels of sTREM2 was stronger (RRR 0.79 [95% CI 0.68 to 0.92]). Thus, a higher sTREM2 level was associated with a reduced risk of rapid clinical progression in patients, and the effect size was bigger than that seen with elevated P‐tau.

TABLE 2.

Multinomial logistic regression model assessing trajectory‐group membership of the patients

| N = 231 | Group 2 vs group 1 | Group 3 vs group 1 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.95 to 1.05 | 1.05 | 0.99 to 1.11 |

| CSF Aβ42 (pg/mL) | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| CSF phosphorylated tau (pg/mL) | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.02 |

| CSF sTREM2 (ng/mL) | 0.97 | 0.90 to 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.77 to 0.94 |

NOTE. Bold values highlight significant differences (P ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: Aβ, amyloid beta; CI, confidence interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; N, number of patients; RRR, relative risk ratio; sTREM2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 .

3.3. CSF sTREM2 of the trajectory groups compared to the cognitively healthy controls

The slow clinical progression group (Group 1; RRR 1.14 [95% CI 1.03 to 1.23]) and the medium clinical progression group (Group 2; RRR 1.12 [95% CI 1.00 to 1.25]) had higher CSF sTREM2 levels than the cognitively healthy controls of the same age (Table 3). There was no difference in the level of sTREM2 between the cognitively healthy and the rapid clinical progression group (Group 3; Table 3). When sex, education, and clinical stage (MMSE) were adjusted for, only the slow clinical progression group (Group 1) had significantly higher level of sTREM2 than the cognitively healthy controls (RRR 1.16 [95% CI 1.01 to 1.33]).

TABLE 3.

Multinomial logistic regression model assessing the patient groups versus the cognitively healthy controls

| N = 273 | Group 1 vs cognitively healthy | Group 2 vs cognitively healthy | Group 3 vs cognitively healthy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI | RRR | 95% CI |

| Age | 0.95 | 0.89 to 1.00 | 0.94 | 0.88 to 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.92 to 1.05 |

| CSF sTREM2 (ng/mL) | 1.14 | 1.03 to 1.26 | 1.12 | 1.00 to 1.25 | 1.02 | 0.91 to 1.15 |

NOTE. Bold values highlight significant differences (P ≤ .05).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; N, number of patients; RRR, relative risk ratio; sTREM2, soluble triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 .

4. DISCUSSION

In patients with a clinical presentation of AD who were followed for up to 3 years after the time of diagnosis, we found three trajectories of clinical progression. The identified groups were much like the clinical progression trajectories of another memory clinic cohort comprising several dementia disorders, but mostly AD dementia. 46 At the same age and level of AD pathology, high baseline CSF sTREM2 was associated with slow clinical progression, and the effect size was bigger than that of p‐tau. Compared to cognitively healthy controls, patients with slow clinical progression had higher CSF sTREM2, even after adjusting for the baseline clinical stage (MMSE). In contrast, the cognitively healthy controls and the patients with rapid clinical progression had similar levels of CSF sTREM2 at baseline. This suggests that CSF sTREM2 could be used as a tool to predict clinical progression among AD patients.

Our findings of a high CSF sTREM2 in patients with slow clinical progression are consistent with increased sTREM2 being associated with slower progression of episodic memory loss and hippocampal atrophy in subjects with AD pathology. 32 Ewers et al. 32 also found that a high CSF sTREM2 was associated with a slower global cognitive decline, but this finding was not significant after correction for multiple testing. Our results suggest that sTREM2 is associated with AD clinical progression, regardless of CSF Aβ42‐ and p‐tau levels. Moreover, we found sTREM2 that had a stronger association with clinical progression than p‐tau. Similar results in our study and Ewers et al. 32 —despite differences in population, outcome measures, and statistical methods—suggest that CSF sTREM2 might be a relevant measure of AD clinical progression. Repeating the findings 32 with a robust measure of cognitive and functional abilities (CDR‐SB) 41 further strengthens the clinical relevance.

CSF sTREM2 have been shown to positively correlate with CSF t‐tau and p‐tau, 24 , 27 , 29 , 30 which are related to rapid clinical progression of AD. 7 , 47 Here, we show that in patients with clinical AD at a given level of CSF Aβ42‐ and p‐tau, higher CSF sTREM2 could be beneficial, indicating a potentially protective effect. One potential explanation is that a high CSF sTREM2 reflects a healthy response of microglia; 48 consequently, despite high CSF t‐tau and p‐tau, the clinical progression is more benign. Through translocator protein PET imaging of activated microglia, two distinct patterns of microglial activation have been found to relate to clinical progression of AD. 49 A high baseline microglial activity that sustained at follow‐up was beneficial—independent of cortical amyloid load and clinical stage. Indeed, sTREM2 injected into the hippocampus of transgenic (5xFAD) mice attracted microglia, enhanced Aβ phagocytosis, and boosted synaptic function. 50 This aligns with our findings of high sTREM2 being associated with a slow clinical progression.

High CSF sTREM2 has been linked to increased cortical‐ and hippocampal thinning (partially related to CSF p‐tau but not to memory loss) in cognitively healthy older individuals, 51 indicating sTREM2 as an early marker of neurodegeneration. Here, we found low CSF sTREM2 in the cognitively healthy controls (without AD pathology) while the highest CSF sTREM2 was found in the slow clinical progression patient group. Thus, our results suggest a protective microglial response mechanism in the early symptomatic stages of AD. It has been proposed that TREM2 activation and microglial function become aberrant as AD progresses, and thus the protective effect is lost. 17 Supporting this, microglia change to the MgND/DAM phenotypes, 19 , 20 with impaired abilities to maintain cerebral health, after engulfing apoptotic neurons. 20 Moreover, in human brains, dystrophic microglia depended on the progression of AD neuropathological changes and were primarily seen in the late stages of the disease. 52 In APP‐mice studies, TREM2 deficiency increased Aβ deposition, 21 , 53 and facilitated amyloid seeding. 21 Interestingly, a recent study showed that mice with the TREM2 common variant had more brain atrophy, synapse loss, and microglial activation in a tauopathy model. 54 Taken together, this may indicate that in late AD stages (with greater tauopathy), as neurodegeneration increases, microglial function is no longer beneficial. 54 It might also be that reduced TREM2 function has differing pathogenic effects in primary tauopathies and AD.

Our results indicate that a forceful microglial response with high TREM2 activity in early clinical AD is beneficial. We speculate that patients with a low baseline CSF sTREM2 level—similar to the one in the cognitively healthy controls—fail to mount the necessary microglial response reaction and thus quickly develop cognitive and functional dysfunctions. 53 It is likely that sTREM2 exhibits a dynamic response during the course of AD; 17 further examination is needed on the molecular mechanisms behind potential shifts in the disease course, and how these could be regulated.

TREM2 genetic information was not available; however, the prevalence of TREM2 variants is rare, 11 , 13 and the likelihood of this study including patients with TREM2 variants is low. CSF sTREM2 has not been found to be related to anti‐inflammatory medication; 51 therefore, medication use was not included in the analyses. Because CSF sTREM2 is unable to discriminate between potentially beneficial and harmful states of microglia, other methods—like bead or array‐based microglial fluid marker analysis—deserve attention. Despite the selection of patient participants, our results should be transferable to other memory clinic populations. The cognitively healthy had more years of education (15.5 [SD 3.1]) than the memory clinic patients (12.3 [SD 3.6], P < .001). Adjusting for education together with sex and MMSE did not notably change the result and, therefore, presumably, this difference in years of education did not bias our findings.

One study strength is the use of well‐characterized cohorts, with patients examined using validated clinical assessment tools and biomarkers, followed over a long time period with CDR. The CDR is a robust measure of functional and cognitive abilities 33 across the stages of cognitive decline. 41 In the present study the CDR was scored post hoc using clinical records—although the records used were thorough and standardized with enough information to score all items—this is a study limitation because the CDR is meant to be used as a prospective tool. 33 Group‐based trajectory modeling used the actual variability in the data to categorize those with comparable progression rates. 42 However, when interpreting these results, one must consider that trajectory modeling is indeed exploratory.

5. CONCLUSION

This study shows that CSF sTREM2 was associated with clinical progression rate in patients with clinical AD. A high CSF sTREM2 was associated with slow clinical progression, seemingly indicating a protective microglial state. Thus, microglial state biology—including TREM2 activity—could be an interesting target for disease‐modifying therapy, especially in the earlier stages of AD. Moreover, this study suggests CSF sTREM2 as a tool for predicting dementia progression, relevant for individualizing follow‐up regimes, and identifying appropriate candidates for clinical trials.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Edwin, Dr. Persson, and Dr. Knapskog report work with Roche BN29553; Dr. Edwin, Dr. Knapskog, and Dr. Saltvedt report work with Boehringer‐Ingelheim 1346.0023, outside the submitted work. Dr. Nilsson has received an honorarium from BioArctic, and has a collaboration with this company, outside the submitted work. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the patients and the staff involved in the Norwegian Registry of Persons Assessed for Cognitive Symptoms, and the cognitively healthy controls for their contribution to the study. The Norwegian Health Association and Alzheimerfondet Civitan Norge contributed with study funding but were not involved in any part of conducting the study or article preparation.

Edwin TH, Henjum K, Nilsson LN, et al. A high cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 level is associated with slow clinical progression of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Dement. 2020;12:e12128 10.1002/dad2.12128

REFERENCES

- 1. Jack CR Jr, Bennett DA, Blennow K, et al. NIA‐AA Research Framework: toward a biological definition of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2018;14(4):535‐562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263‐269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tan M‐S, Ji X, Li J‐Q, et al. Longitudinal trajectories of Alzheimer's ATN biomarkers in elderly persons without dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Haaksma ML, Rizzuto D, Leoutsakos J‐MS, et al. Predicting cognitive and functional trajectories in people with late‐onset dementia: 2 population‐based studies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(11):1444‐1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kester MI, van der Vlies AE, Blankenstein MA, et al. CSF biomarkers predict rate of cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73(17):1353‐1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Snider BJ, Fagan AM, Roe C, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers and rate of cognitive decline in very mild dementia of the Alzheimer type. Arch Neurol. 2009;66(5):638‐645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Heneka MT, Carson MJ, El Khoury J, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):388‐405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colonna M. TREMs in the immune system and beyond. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(6):445‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hickman SE, Kingery ND, Ohsumi TK, et al. The microglial sensome revealed by direct RNA sequencing. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(12):1896‐1905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jonsson T, Stefansson H, Steinberg S, et al. Variant of TREM2 associated with the risk of Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):107‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sims R, van der Lee SJ, Naj AC, et al. Rare coding variants in PLCG2, ABI3, and TREM2 implicate microglial‐mediated innate immunity in Alzheimer's disease. Nat Genet. 2017;49(9):1373‐1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Guerreiro R, Wojtas A, Bras J, et al. TREM2 variants in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):117‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Guerreiro RJ, Lohmann E, Bras JM, et al. Using exome sequencing to reveal mutations in TREM2 presenting as a frontotemporal dementia‐like syndrome without bone involvement. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70(1):78‐84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Carmona S, Zahs K, Wu E, Dakin K, Bras J, Guerreiro R. The role of TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2018;17(8):721‐730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paloneva J, Manninen T, Christman G, et al. Mutations in two genes encoding different subunits of a receptor signaling complex result in an identical disease phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71(3):656‐662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gratuze M, Leyns CEG, Holtzman DM. New insights into the role of TREM2 in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2018;13(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhao Y, Wu X, Li X, Jiang LL, Gui X, Liu Y, et al. TREM2 is a receptor for β‐Amyloid that mediates microglial function. Neuron. 2018;97(5):1023‐1031.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Keren‐Shaul H, Spinrad A, Weiner A, et al. A unique microglia type associated with restricting development of Alzheimer's Disease. Cell. 2017;169(7):1276‐1290.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Krasemann S, Madore C, Cialic R, et al. The TREM2‐APOE pathway drives the transcriptional phenotype of dysfunctional microglia in neurodegenerative diseases. Immunity. 2017;47(3):566‐581.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Parhizkar S, Arzberger T, Brendel M, et al. Loss of TREM2 function increases amyloid seeding but reduces plaque‐associated ApoE. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22(2):191‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleinberger G, Yamanishi Y, Suárez‐Calvet M, et al. TREM2 mutations implicated in neurodegeneration impair cell surface transport and phagocytosis. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(243):243ra86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Piccio L, Buonsanti C, Cella M, et al. Identification of soluble TREM‐2 in the cerebrospinal fluid and its association with multiple sclerosis and CNS inflammation. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 11):3081‐3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Suárez‐Calvet M, Kleinberger G, Araque Caballero M, et al. sTREM2 cerebrospinal fluid levels are a potential biomarker for microglia activity in early‐stage Alzheimer's disease and associate with neuronal injury markers. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(5):466‐476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Suárez‐Calvet M, Araque Caballero M, Kleinberger G, et al. Early changes in CSF sTREM2 in dominantly inherited Alzheimer's disease occur after amyloid deposition and neuronal injury. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(369):369ra178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ulrich JD, Ulland TK, Colonna M, Holtzman DM. Elucidating the Role of TREM2 in Alzheimer's Disease. Neuron. 2017;94(2):237‐248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piccio L, Deming Y, Del‐Aguila JL, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 is higher in Alzheimer disease and associated with mutation status. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2016;131(6):925‐933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wilson EN, Swarovski MS, Linortner P, et al. Soluble TREM2 is elevated in Parkinson's disease subgroups with increased CSF tau. Brain. 2020;143(3):932‐943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Heslegrave A, Heywood W, Paterson R, et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 concentration in Alzheimer's disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2016;11:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Henjum K, Almdahl IS, Arskog V, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid soluble TREM2 in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Knapskog AB, Henjum K, Idland AV, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid sTREM2 in Alzheimer's disease: comparisons between clinical presentation and AT classification. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):15886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ewers M, Franzmeier N, Suárez‐Calvet M, et al. Increased soluble TREM2 in cerebrospinal fluid is associated with reduced cognitive and clinical decline in Alzheimer's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2019;11(507):eaav6221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hughes CP, Berg L, Danziger WL, Coben LA, Martin RL. A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1982;140:566‐572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braekhus A, Ulstein I, Wyller TB, Engedal K. The Memory Clinic–outpatient assessment when dementia is suspected. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2011;131(22):2254‐2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270‐279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dani M, Wood M, Mizoguchi R, et al. Microglial activation correlates in vivo with both tau and amyloid in Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141(9):2740‐2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Idland AV, Sala‐Llonch R, Borza T, et al. CSF neurofilament light levels predict hippocampal atrophy in cognitively healthy older adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:138‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Buchhave P, Londos E, Blennow K, Minthon L. Association between CSF biomarkers and incipient Alzheimer's disease in patients with mild cognitive impairment: a follow‐up study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(3):228‐234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morris JC. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). Current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43(11):2412‐2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Williams MM, Storandt M, Roe CM, Morris JC. Progression of Alzheimer's disease as measured by Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes scores. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1 Suppl):S39‐S44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cedarbaum JM, Jaros M, Hernandez C, et al. Rationale for use of the Clinical Dementia Rating Sum of Boxes as a primary outcome measure for Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1 Suppl):S45‐S55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group‐based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jones BL, Nagin DS. A Note on a stata plugin for estimating group‐based trajectory models. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(4):608‐613. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Helvik AS, Engedal K, Šaltytė Benth J, Selbæk G. Time from symptom debut to dementia assessment by the specialist healthcare service in Norway. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2018;8(1):117‐127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Edwin TH, Strand BH, Persson K, Engedal K, Selbæk G, Knapskog AB, Trajectories and risk factors of dementia progression: A memory clinic cohort followed up to three years from diagnosis Accepted for publication in Int Psychogeriatr August 20th 2020. 10.1017/S1041610220003270 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47. Degerman Gunnarsson M, Ingelsson M, Blennow K, Basun H, Lannfelt L, Kilander L. High tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid predict nursing home placement and rapid progression in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2016;8(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhong L, Chen XF, Wang T, et al. Soluble TREM2 induces inflammatory responses and enhances microglial survival. J Exp Med. 2017;214(3):597‐607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hamelin L, Lagarde J, Dorothée G, et al. Distinct dynamic profiles of microglial activation are associated with progression of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018;141(6):1855‐1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhong L, Xu Y, Zhuo R, et al. Soluble TREM2 ameliorates pathological phenotypes by modulating microglial functions in an Alzheimer's disease model. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1365.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Halaas NB, Henjum K, Blennow K, et al. CSF sTREM2 and tau work together in predicting increased temporal lobe atrophy in older adults. Cereb Cortex. 2020;30(4):2295‐2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Prokop S, Miller KR, Labra SR, et al. Impact of TREM2 risk variants on brain region‐specific immune activation and plaque microenvironment in Alzheimer's disease patient brain samples. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2019;138(4):613‐630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Jay TR, Hirsch AM, Broihier ML, et al. Disease progression‐dependent effects of TREM2 deficiency in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci. 2017;37(3):637‐647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gratuze M, Leyns CE, Sauerbeck AD, et al. Impact of TREM2R47H variant on tau pathology‐induced gliosis and neurodegeneration. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:4954‐4968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information