Abstract

Hybridization probes have been used for the detection of single nucleotide variations (SNV) in DNA and RNA sequences in the mix-and-read formats. Among the most conventional are Taqman probes, which require expensive quantitative PCR (qPCR) instruments with melting capabilities. More affordable isothermal amplification format requires hybridization probes that can selectively detect SNVs isothermally. Here we designed a split DNA aptamer (SDA) hybridization probe based on a recently reported DNA sequence that binds a dapoxyl dye and increases its fluorescence (Kato, T.; Shimada, I.; Kimura, R.; Hyuga, M., Light-up fluorophore-DNA aptamer pair for label-free turn-on aptamer sensors. ChemCommun 2016, 52, 4041–4044). SDA uses two DNA strands that have low affinity to the dapoxyl dye unless hybridizes to abutting positions at a specific analyte and forms a dye-binding site, which is accompanied by up to a 120-fold increase in fluorescence. SDA differentiates SNV in the inhA gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis at ambient temperatures and detects a conserved region of the Zika virus after isothermal nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA) reaction. The approach reported here can be used for detection of isothermal amplification products in the mix-and-read format as an alternative to qPCR.

Keywords: fluorescent sensor, binary aptamer, mutation analysis, dapoxyl aptamer, SNP differentiation, NASBA, point-of-care, isothermal analysis, mix-and-read

Graphical Abstract

Sequence-selective fluorescence sensors, such as molecular beacon (MB)1–4 and Taqman probes,5 have been widely used in quantitative real time PCR (qPCR) assays2,6–7 for diagnosis of infectious diseases and cancer, among other applications.8–17 The use of these expensive hybridization probes is justified by the need to detect single nucleotide variations (SNV) in nucleic acids. However, Taqman and MB probes can distinguish SNVs only if melting temperature profiles are recorded, which requires expensive qPCR instruments with melting capabilities.18 Moreover, qPCR-based technologies require expensive maintenances, software, and reagents as well as trained personnel. These are the reasons why molecular diagnostics is shifting towards adopting isothermal amplification reactions,19–23 which do not require expensive instrumentation and thus are potentially affordable not only by specialized diagnostic laboratories, but also by health care providers and individual patients.19–25 The genotyping potential of such affordable diagnostics depends on development of hybridization probes selective towards SNVs at constant temperatures and preferably label-free to further lower the assay costs. Here, we designed such a probe and demonstrated that it is suitable for the analysis of an amplicon after isothermal amplification.

Earlier, we have introduced the concept of split aptameric probes for nucleic acid analysis (Scheme 1A).26–28 The approach takes advantage of the aptamers that can bind a low fluorescence dye and thereby increase its fluorescence. Split aptameric probes consist of two unlabeled nucleic acid strands that bind a complementary DNA or RNA analyte sequence and form a dye-binding site. Binding of the dye to the aptamer increases its fluorescence.

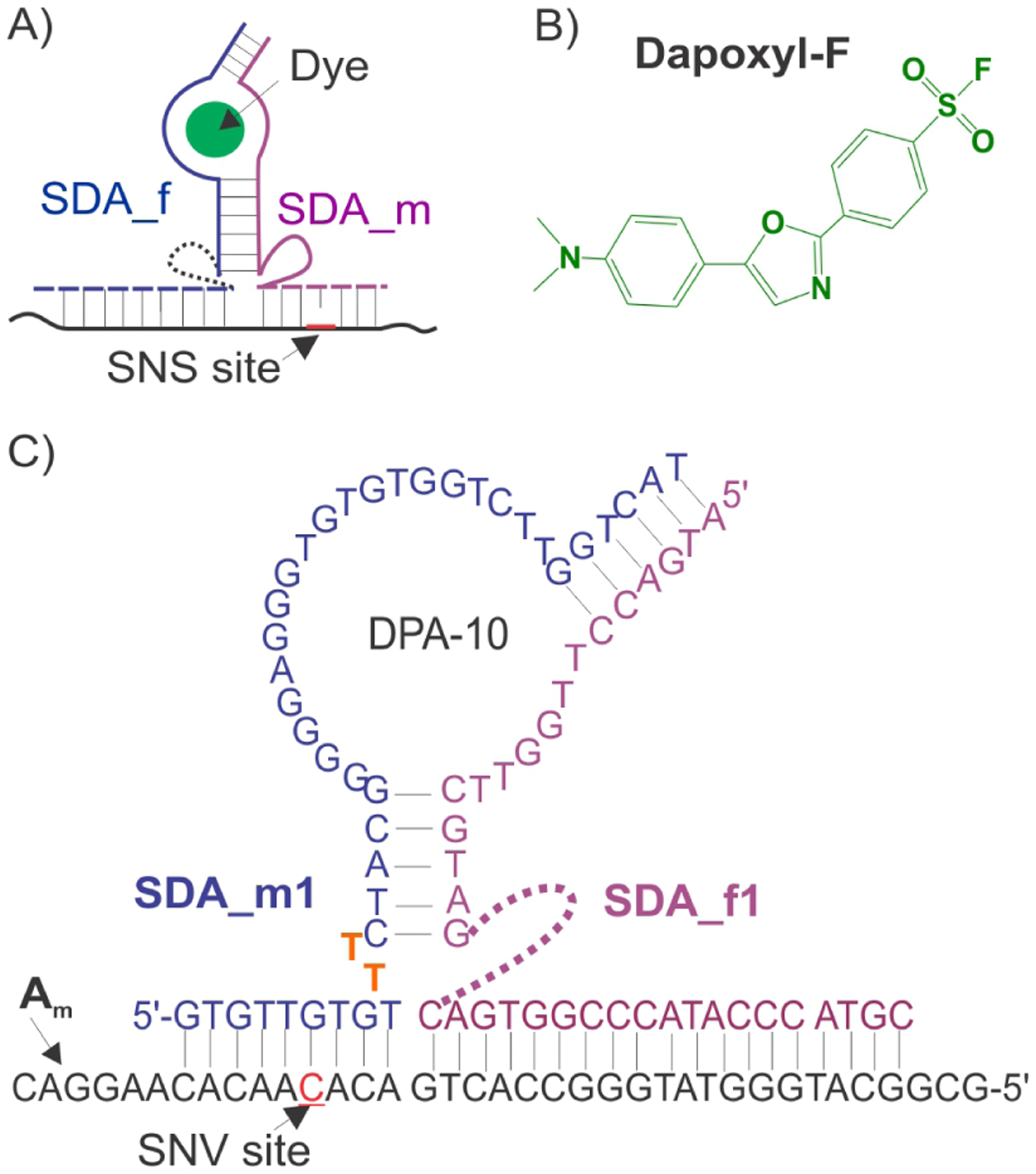

SCHEME 1.

Design of SDA probes for the analysis of single nucleotide substitutions (SNS). A) General scheme of a split aptameric probe: two RNA or DNA oligonucleotides bind an analyte and form a dye-binding site. Bound dye produces a fluorescent signal.26–28 B) Structure of dapoxyl-F dye; C) Detailed sequence of SDA in complex with fully matched analyte (Am), a fragment of inhA gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. SNS site is red underlined. SDA_f1 contains a triethylene glycol linker (dashed line). SDA_m1 contains dithymidine (TT) linker (orange).

Previously published constructs used RNA–based aptamers including malachite green26 and spinach.27,28 However, RNA is less chemically stable than DNA. Moreover, as a commercial product, synthetic RNA is about 20 times more expensive than DNA. The only example of a split probe based on a DNA aptamer requires Hoechst derivative as a fluorophore,29 which can be obtained only via a lengthy synthetic scheme and is not commercially available.

Recently a DNA aptamer, DAP-10 (Figure S1A, Table S1), was selected to bind dapoxyl dyes.30 In this study, we took advantage of DAP-10 structure to design a split dapoxyl aptamer (SDA) probe for highly selective detection of nucleic acid analysis at room temperature. Further, we demonstrate that SDA can selectively detect a sample of Zika virus RNA after isothermal nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA).22,23

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials and instruments.

All oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). Dapoxyl fluorine (dapoxyl-F, Scheme 1B) was synthesized as described by Diwu et al.31 Fluorescent spectra were recorded using Fluorescence Spectrometer LS55 (PerkinElmer) and Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Agilent). Unless otherwise noted, excitation wavelength was set to 390 nm and emission was taken at 505 nm. Time dependence experiments were performed using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer (Agilent). Zika Virus (strain 1840) obtained from World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses.

Source of Zika Virus RNA.

Zika Virus (strain 1840) obtained from World Reference Center for Emerging Viruses and Arboviruses as grown in Vero cells in DMEM media containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Viral RNA was extracted using Trizol LS (Life Technologies) and quantified via absorbance at 260 nm using a NanoDrop Onec (Thermo Scientific).

General Fluorescent assay for DAP-10.

Dapoxyl-F (0.5 μM) and DAP-10 (0.58 μM) or SDA_m and SDA_f1 (at indicated concentrations) were added to 30 μL of Buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2). Total volume was adjusted to 60 μL by water. Control samples contained only dapoxyl-F (0.5 μM). All samples were incubated at room (22.5 °C) temperature. Fluorescent spectra were recorded after indicated incubation times. Data of three independent experiments were processed using Microsoft Excel.

NASBA assay.

Viral RNA, was added to 1×NASBA reaction buffer (TrisHCl, pH 8.5 at 25 °C, MgCl2, KCl, DTT, and DMSO; Life Sciences Advanced Technologies Inc.), nucleotide mix (NECN-1–24) 250 nM reverse and forward primers (Table S1) to the final concentration of 50 fg/μL (total volume 12 μL with water). Samples were incubated at 65 °C for 2 min followed by cooling to 41 °C for 10 min. Three microliters of NASBA enzyme cocktail (AMV RT, RNase H, T7 RNAP, BSA, Life Sciences Advanced Technologies Inc.) was added and samples were incubated 90 min at 41 °C. Samples were analyzed in 2% Agarose gel (Figure 2B). The concentration of Z-147 amplicon was estimated based on the intensity of the correspondent band in gel and comparison with the intensity of the 200 nt band of RiboRuler Low Range RNA Ladder (ThermoFisher Scientific).

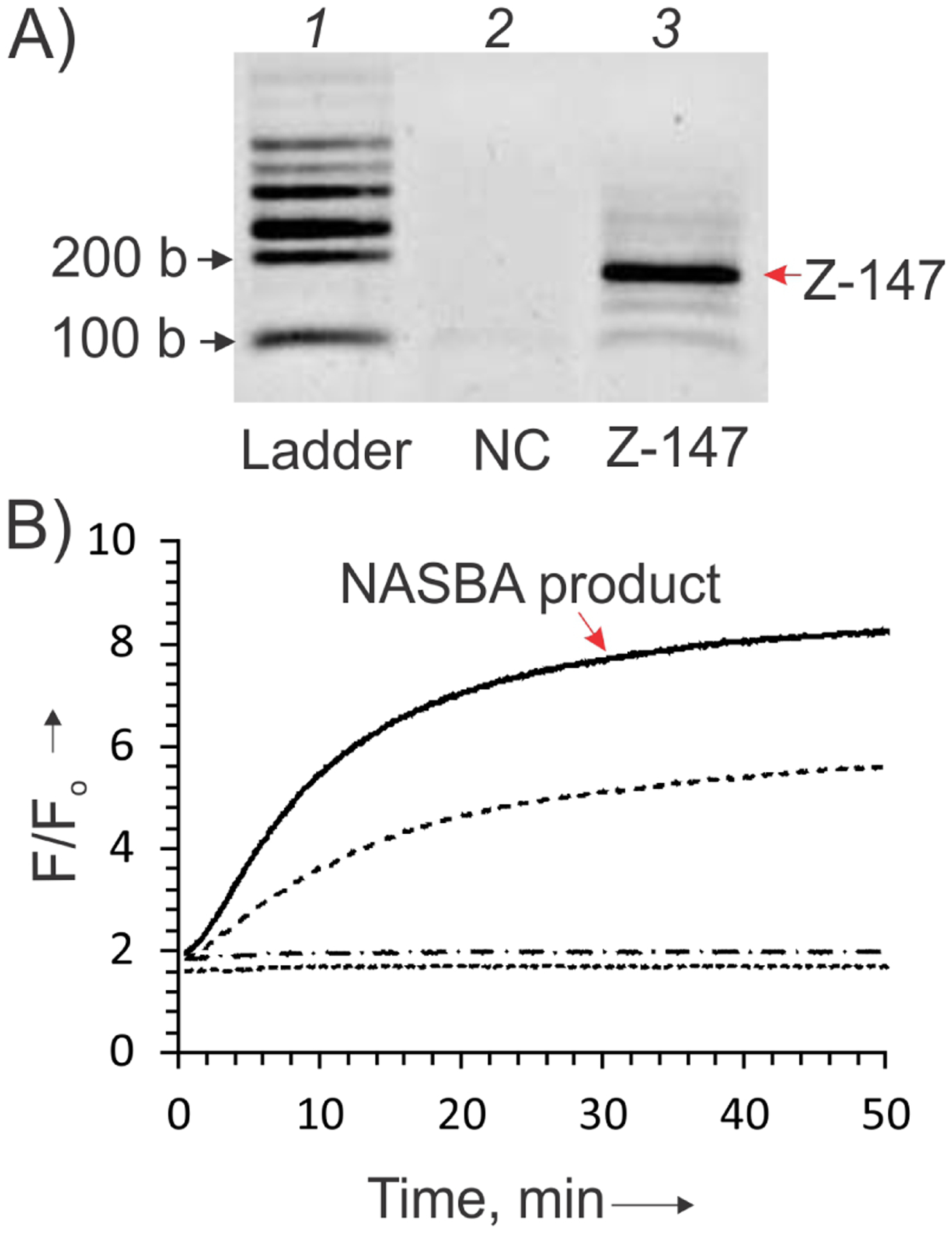

FIGURE 2.

SDA2 can detect RNA product of nucleic acid sequence based amplification (NASBA). A) Agarose gel analysis of Zika viral RNA amplicon (Z-147) obtained by NASBA amplification of a vial RNA sample as described in SI. Lane 1, 100 – 1000 nucleotide Low Range RNA Ladder. Lane 2, negative control (NC, no ZIKV RNA added for NASBA reaction). Lane 3, 147-nucleotide NASBA RNA amplicon Z-147. B) Time dependence for the fluorescent signal of SDA2 in presence of Z-147 amplicon (10%) in NASBA buffer (solid line). As negative controls, SDA2 in the absence of the analyte (dotted line) or in the presence of NASBA no-target control (dash-dotted line) was used. Positive control (dashed line) contained SDA2 in the presence of 100 nM Z-64 synthetic DNA analyte. All samples contained 0.5 μM dapoxyl-F, 4 μM SDA_f2 and 0.5 μM SDA _m2 strands in 60 μL NASBA buffer. Measurements were taken at room temperature (22.5°C).

Analysis of NASBA amplicon by SDA probe.

Time drive experiments were performed in NASBA buffer at room temperature (~22.5 °C) using a Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer in a kinetic mode. The samples contained 0.5 μM. Dapoxyl-F (0.5 μM), SDA_m2 (0.5 μM) SDA_f2 (4 μM) and either 10% NASBA amplicon Z-147 or 10% NASBA no-target control. Blank contained Dapoxyl-F (0.5 μM), SDA_m2 (0.5 μM) and SDA_f2 (4 μM) in the absence of an analyte. As a positive control, a sample containing 100 nM Z-64 (Table S1) synthetic DNA analyte instead of NASBA amplicon was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Dapoxyl-F dye (Scheme 1B) was synthesized according to the procedure described earlier.31 The compound was characterizes by H1 NMR (Figure S2). Dapoxyl-F was then tested for its ability to fluoresce upon binding to DAP-10 aptamer. The presence of a full DAP-10 aptamer resulted in 228-fold increase in the dapoxyl-F fluorescence (Figure S2C).

As a model analyte, we chose a fragment of inhA gene of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb). Point mutations in this gene fragment are associated with Mtb resistance to one of the key drug used for tuberculosis treatment – isoniazid.32 For optimization of SDA design, we used two model inhA-related analytes – a fully matched DNA analyte Am (5’-GCG GCA TGG GTA TGG GCC ACT GAC A C A ACA CAA GGA C) and a mismatched analyte Amm (5’-GCG GCA TGG GTA TGG GCC ACT GAC A T A ACA CAA GGA C) containing a C->T single nucleotide substitution (underlined nucleotides).

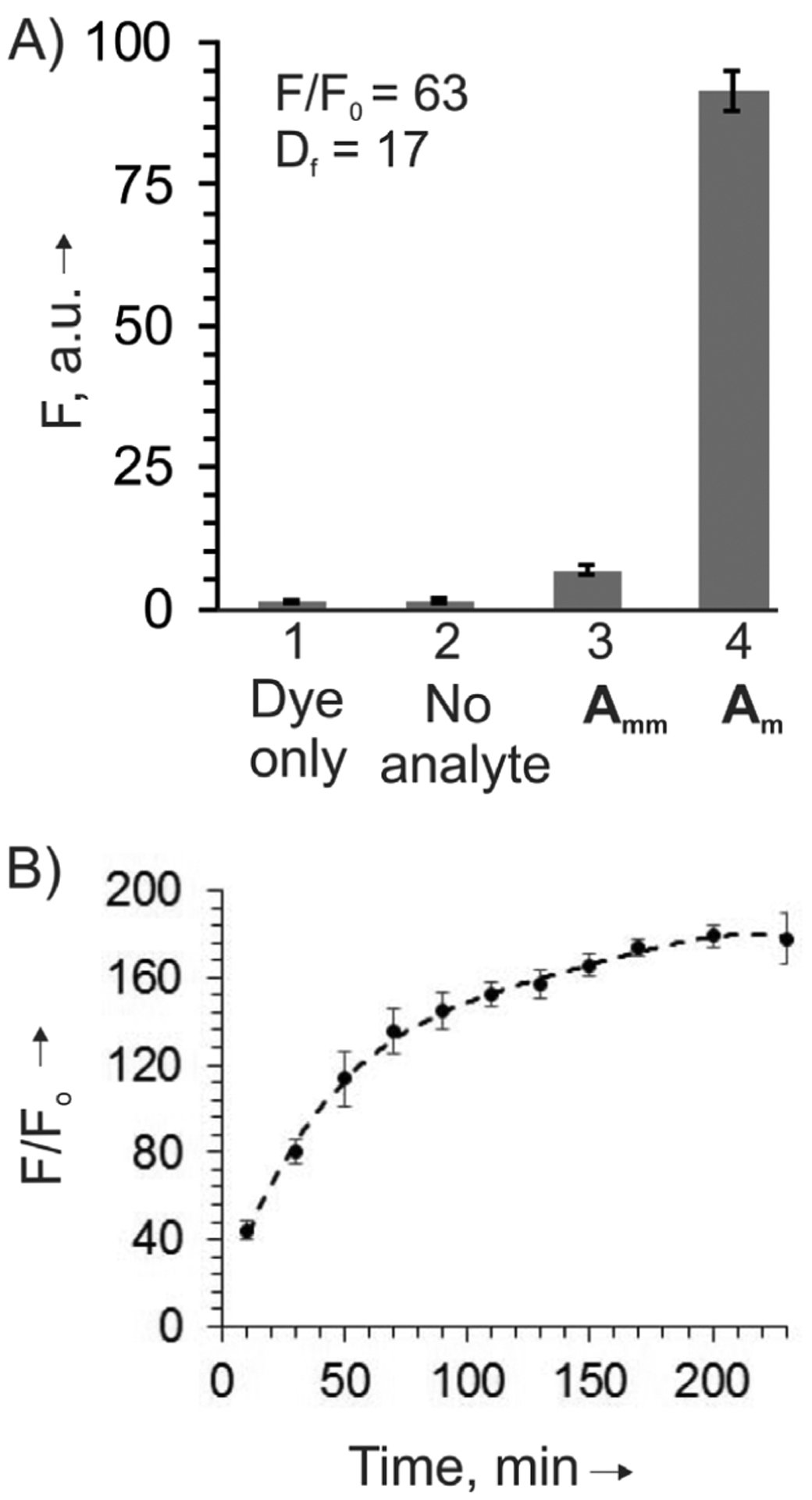

To construct a split aptameric sensor, DAP-10 structure was divided into two strands (SDA_f1 and SDA_m1, Scheme 1C and Figure S1), each of which was equipped with an analyte-binding arm. Splitting of the dye-binding aptamer prevented dapoxyl dye from binding to the two separated strands, which maintained low background signal (Figure 1A, compare bars 1 and 2). Sequence of stem 1 was chosen based on the constructs reported by Kato et. at.; two terminal A/T base pairs were added to increase stem stability. The hexanucleotide stem was, however, short enough (Tm = 15.6 °C), to pervert SDA_f1 and SDA_m1 association in the absence of analyte.’ When the analyte-binding arms of SDA_f1 and SDA_m1 hybridized to their complimentary Am fragments next to each other, the dapoxyl binding site was re-formed, and the dye’s fluorescence increased thus reporting the presence of the analyte (Figure 1A, bar 4). Each analyte-binding arm was connected to the aptamer half with a linker – either a trietyhylene glycol (teg) spacer or a dinucleotide bridge. These linkers impart flexibility to the aptameric structure, which is presumably required to ensure simultaneous formation of the dapoxyl-F-binding site and tight binding of the analyte.26–28 Indeed, in the absence of the linkers the SDA probe demonstrates either reduced signal-to-background ratio (F/Fo) or inability to differentiate Am from Amm analyte (Figure S3 and S4). SDA1 consisting of SDA_f1 and SDA_m1 produced F/Fo = 63 after 60 min of hybridization reaction (Figure 1A). However, longer incubation time further increased F/Fo to ~ 120 reaching plateau after ~200 min of incubation (Figure 1B). Generally, higher analyte concentration also increases signal (Figure S7). Despite this long time required to achieve maximum signal, up to 30-fold fluorescent increase was observed within the first 10 min of the hybridization reaction (Figure 1B), which is above or comparable to the fluorescent hybridization assays with conventional probes.1–3 Split probe produced lower turn on ratio (F/Fo ~120) than full DAP-10 aptamer (F/Fo ~ 228) due to possibly lower stability of the aptamer core. Indeed, in DAP-10 the core is formed within single DNA molecule, while formation of aptameric core for SDA hybridization probe requires association of 3 strands: SDA_f1, SDA_m1 and the analyte. In this later association (Scheme 1C) the aptameric core could be slightly disturbed by the presence of the anatyte.

FIGURE 1.

Analysis of Am and Amm by SDA1 probe. A) Selectivity of SDA towards matched analyte. All samples contained 0.5 μM dapoxyl-F in Buffer 1. In addition, Sample 2–4 contained 1 μM SDA_m1 and 0.2 μM SDA_f1 in the absence (bar 2, ~1.44 a.u.) or presence of 0.1 μM mismatched (Amm, bar 3, 6.7 a.u.) or 0.1 μM matched (Am, bar 4, ~91.5 a.u) analytes. Fluorescent measurements were taken after 60 min of incubation. The data is the average of 3 independent experiments with standard deviations as error bars. B) Fluorescence time dependence. Measurements were taken in the presence of 0.5 μM dapoxyl-F, 1 μM SDA_m1 and 0.2 μM SDA_f1 and 1 μM of Am in Buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 200 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2).The background fluoresce for SDA (no analyte) was ~1.5 (panel A, no analyte). Therefore, after 10 min F/Fo was ~27 and after 200 ~120.

SDA_ m1 was designed short enough to enable differentiation of the fully matched Am from a single-base mismatched Amm at room temperature. SDA1 demonstrated remarkable selectivity in recognition of fully matched Am. The differentiation factor (Df) of 17 was calculated from the data presented in Figure 1A according to the formula:

where Fm- fluorescence in the presence of Am; Fmm – fluorescence in the presence of Amm and F0 – fluorescence of SDA in the absence of the analytes. Importantly, this differentiation was achieved at room temperature, which is difficult to obtain using most common TaqMan and molecular beacon probes.2

Next, we determined the limit of detection (LOD) for the SDA1 probe based on the data shown in Figure S5. The found LOD of 0.44 nM is lower than or comparable to that of MB probes (typical LOD is ~1 nM),2 and is acceptable for nucleic acid analysis after amplification.

To confirm that SDA design is universal for the detection of other analyte sequences, an additional DNA analyte - Z-64- was selected. Z-64 (Table S1) is a sequence corresponding to a highly conserved fragment of the Zika virus (ZIKV) genome. New f and m strands, SDA_f2 and SDA_m2 (Table S1) were designed to be complementary to the Z-64) analyte; otherwise, the design of the probes was as shown in Scheme 1. Up to ~54 for Z-64 F/F0 values were observed: (Figure S6). DF for this sensor was not measured, due to the absence of the practically significant mutations the require differentiation. Even though the maximum fluorescence intensity was the same for both Am and Z-64, the difference in the background fluorescence, which depends on analyte-independent association of strands SDA_m and SDA_f, accounted for the variation in F/Fo.

It is important that for each buffer conditions we optimized concentrations of dapoxyl dye and SDA_f and SDA_m strands using the following criteria: (1) highest F/Fo and (2) highest differentiation factor. The optimization was done similar to that shown in Figure S3 for optimization of linker design (data not shown). Our typical set up for split probes employs higher concentrations of strands with longer analyte binding arm (SDA_f in this case) and lower concentration of strand with shorter arm (SDA_m). The long arm of SDA_f binds the analyte with high affinity unwinds the analyte secondary structure, why low concentration of SDA_m with short analyte ensures high sequence selectivity, as was discussed in details in our earlier work.33

Most hybridization probes require higher concentrations of a nucleic acid analyte than can be obtained in clinical samples. Therefore, nucleic acid amplification step is required prior to the analysis. We, therefore, turned our attention to NASBA, which is known to produce high concentrations of a single-stranded RNA amplicon,22–23 and is considered one of the most promising isothermal amplification techniques.34–36 A fragment of the ZIKV envelope gene was amplified by NASBA using RNA ZIKV (Brazil 1840 isolate) isolated from vero cells to produce a 147-nt RNA amplicon (Z-147, Table S1). The production of Z-147 fragment by NASBA was confirmed by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 2A). In comparison with Buffer 1, NASBA Buffer increased the intensity of background dye fluorescence, possibly due to the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide.31 However, SDA2 was able to detect the NASBA product directly in NASBA buffer (Figure 2B) with the detection limit of 10 nM (Figure S5 B). Next we tested the performance of SDA2 in NASBA buffer at elevated temperatures. It was found that the sensor responded at 37°C with F/Fo up to 5. This turn on ratio was about 2 times lower than at 22.5°C, but still acceptable for NASBA product analysis (Figure S7). There was no signal above the background observed at 41°C, the temperature recommended for NASBA (data not shown).

We designed a new fluorescent hybridization probe, SDA which detected complementary analyte with high selectivity, turn-on ratio up to 120 and LOD in the subnanomolar range. It was capable of analyzing 147 nucleotide RNA Z-147. SDA maintained its function in complex NASBA buffer which contains a cocktail of enzymes and high concentration of DTT among other proprietary components. SDA maintained fluorescence at temperatures up to 37°C (Figure S7). NASBA reaction, however, requires 41°C. Under this temperate, SDA was found to lose its ability to produce appreciable signal, most likely due to lower affinity of dapoxyl-F to the aptamer core at this temperature. Lowering NASBA reaction temperature or re-selecting the dapoxyl-F-binding aptamer would enable development of real time NASBA isothermal alternative to qPCR. However, the presented analytical format allows NASBA product detection after NASBA and cooling samples to room temperature. In this non-optimized in terms of practical utility format, the assay requires two thermostats for 65 and 41°C (primer annealing and NASBA reaction temperatures) and ~ 15–25 min of total assay time (without accounting RNA purification time). The signal can be registered by a portable fluorimeter. Therefore, time and equipment requirement satisfy the ASSURED criteria of a point of care detection techniques37 and could be adopted by low-resources laboratories or doctor offices.

The LOD of SDA was in subnanomolar range similar to other aptameric sensors that do not used signal amplification streategies.38 For SDA, the LOD could be limited by aptamer-dye dissociation constant. Typical dissociation constants for an aptameric complex is from picomolar to mid nanomolar range.26–30 For dapoxyl dye binding aptamers, Kd values are in the range of 7–25 nM.30 Despite this limitation, the LOD is lower than that for MB probes (~ 1 nM)2 and, therefore, is acceptable for the detection of nucleic acids after amplification. The LOD for NASBA product was found to be 10 nM, which is high that that for synthetic analyte most likely due to the folded structure of RNA NASBA product, which reduced association of SDA probe with the analyte.

The probe required up to 200 min to reach maximum fluorescent response. However, the resulting repose maximum was higher than that of conventional fluorescent probes (e.g MB probe).2 Importantly, F/Fo ~ 27 appears in the first 10 min of incubation with fully complementary probe (Fig 1B), which is acceptable for analytical purposes. While the delay in response should be investigated in details, we speculate that intimate slow structural adjustments of the dapoxyl dye in the aptameric site may be the reason for additional fluorescent increase after initial aptamer-dye binding. Indeed, some long-lasted fluorescent adjustments have been described for fluorophore-labeled DNA probes.39

SDA offers high selectivity at ambient temperatures, as was well-documented for other representatives of split probes,40 but not for conventional Taqman and molecular beacon probes.2 Another SDA advantage is the straightforward design: adjustments of analyte binding arms of SDA_f and m strands is the only change required for tailoring SDA to each new analyte. Finally, each SDA probe requires synthesis of a pair of inexpensive label-free DNA oligonucleotides, which together have about 10–20 time lower cost than a typical MB or Taqman probe obtained from commercial venders. Therefore, SDA probes promise to lower the cost of designing and mass producing SNV-selective sensors.

Conclusion.

In this study we divided the DAP-10 into two separate parts and equipped each part with analyte-binding arm for hybridization to specific DNA or RNA analytes. The resultant SDA probe was able to fluorescently report the presence of a specific nucleic acid at 22.5°C and 37°C with high selectivity toward SNV in analytes. The novelty of this manuscript is twofold: (1) DNA split aptameric probed was used for the 1st time. It is inexpensive label free and highly selective. There has been no such a combination of properties reported so far. (ii) Split probe was for the 1st time used to detect a biological samples straight after NASBA amplification without downstream processing of the sample this is an unprecedented example that can eventually lead to real time NASBA reaction with a potential to replace real time PCR at least in some applications. SDA therefore, is cost efficient hybridization probe in a mix-and-read format that can be used with NASBA amplification and potentially in other isothermal amplification formats.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Hyeryun Choe from the Department of Immunology and Microbiology, Scripps Research Institute for providing Zika virus RNA.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by the Florida Department of Health, Biomedical Research Program (grant 7ZK33) to YVG. Funding from NSF CBET 1706802, R21AI123876 that support studies in DMK and YVG, respectively are greatly appreciated.

ABBREVIATIONS

- SDA

split DNA aptamer

- MB

molecular beacon

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- Mtb

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- SNV

single nucleotide variation

- TEG

triethylene glycol

- F/F0

fluorescence turn-on ratio

- Df

differentiation factor

- NASBA

nucleic acid sequence based amplification

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

- LOD

limit of detection

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website. It contains list of oligonucleotides used in this study; NMR spectrum of Dapoxyl-F dye; detailed design of SDA contracts; original data for calculation of LODs of SDA; Selectivity data for SDA; SDA performance at 37°C.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tyagi S; Kramer FR, Molecular beacons: Probes that fluoresce upon hybridization. Nature Biotech. 1996, 14, 303–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kolpashchikov DM, An Elegant Biosensor Molecular Beacon Probe: Challenges and Recent Solutions. Scientifica 2012, 2012, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tan X; Wang Y; Armitage BA; Bruchez MP, Label-free Molecular Beacons for Biomolecular Detection. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 10864–10869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juul S; Obliosca JM; Liu C; Liu Y-L; Chen Y-A; Imphean DM; Knudsen BR; Ho Y-P; Leong KW; Yeh H-C, NanoCluster Beacons as reporter probes in rolling circle enhanced enzyme activity detection. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 8332–8337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris T; Robertson B; Gallagher M, Rapid reverse transcription-PCR detection of hepatitis C virus RNA in serum by using the TaqMan fluorogenic detection system. J. Clin. Microbiol 1996, 34, 2933–2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Juskowiak B, Nucleic acid-based fluorescent probes and their analytical potential. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2011, 399, 3157–3176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suzuki Y; Yokoyama K, Development of functional fluorescent molecular probes for the detection of biological substances. Biosensors 2015, 5, 337–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyle DG; Boyle DB; Olsen V; Morgan JAT; Hyatt AD, Rapid quantitative detection of chytridiomycosis (Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis) in amphibian samples using real-time Taqman PCR assay. Dis. Aquat. Organ 2004, 60, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smythe LD; Smith IL; Smith GA; Dohnt MF; Symonds ML; Barnett LJ; McKay DB, A quantitative PCR (TaqMan) assay for pathogenic Leptospira spp. Bmc Infec. Dis 2002, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callison SA; Hilt DA; Boynton TO; Sample BF; Robison R; Swayne DE; Jackwood MW, Development and evaluation of a real-time Taqman RT-PCR assay for the detection of infectious bronchitis virus from infected chickens. J. Virol. Methods 2006, 138, 60–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moody A; Sellers S; Bumstead N, Measuring infectious bursal disease virus RNA in blood by multiplex real-time quantitative RT-PCR. J. Virol. Methods 2000, 85, 55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pai M; Kalantri S; Dheda K, New tools and emerging technologies for the diagnosis of tuberculosis: Part II. Active tuberculosis and drug resistance. Exp. Rev. Mol. Diagn 2006, 6, 423–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marras SAE; Tyagi S; Kramer FR, Real-time assays with molecular beacons and other fluorescent nucleic acid hybridization probes. Clinica Chimica Acta 2006, 363, 48–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vogelstein B; Kinzler KW, Digital PCR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1999, 96, 9236–9241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xiao Y; Pavlov V; Niazov T; Dishon A; Kotler M; Willner I, Catalytic beacons for the detection of DNA and telomerase activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 7430–7431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabert J; Beillard E; van der Velden VHJ; Bi W; Grimwade D; Pallisgaard N; Barbany G; Cazzaniga G; Cayuela JM; Cave H; Pane F; Aerts JLE; De Micheli D; Thirion X; Pradel V; Gonzalez M; Viehmann S; Malec M; Saglio G; van Dongen JJM, Standardization and quality control studies of ‘real-time’ quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction of fusion gene transcripts for residual disease detection in leukemia - A Europe Against Cancer Program. Leukemia 2003, 17, 2318–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Si ML; Zhu S; Wu H; Lu Z; Wu F; Mo YY, miR-21-mediated tumor growth. Oncogene 2007, 26, 2799–2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlando C, Pinzani P, Pazzagli M. Developments in quantitative PCR. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med 1998, 36, 255–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Asiello PJ; Baeumner AJ, Miniaturized isothermal nucleic acid amplification, a review. Lab on a Chip 2011, 11, 1420–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Craw P; Balachandran W, Isothermal nucleic acid amplification technologies for point-of-care diagnostics: a critical review. Lab on a Chip 2012, 12, 2469–2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parida M; Sannarangaiah S; Dash PK; Rao PVL; Morita K, Loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): a new generation of innovative gene amplification technique; perspectives in clinical diagnosis of infectious diseases. Rev. Med. Vir 2008, 18, 407–421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kievits T; Vangemen B; Vanstrijp D; Schukkink R; Dircks M; Adriaanse H; Malek L; Sooknanan R; Lens P, NASBA isothermal enzymatic invitro nucleic-acid amplification optimized for the diagnosis of hiv-1 infection. J. Virol. Methods 1991, 35, 273–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Compton J, Nucleic-acid sequence-based amplification. Nature 1991, 350, 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao X, Dong T. Multifunctional sample preparation kit and on-chip quantitative nucleic acid sequence-based amplification tests for microbial detection Anal. Chem. 2012, 84, 8541–8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niemz A; Ferguson TM; Boyle DS, Point-of-care nucleic acid testing for infectious diseases. Trends in Biotechnology 2011, 29, 240–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolpashchikov DM, Binary malachite green aptamer for fluorescent detection of nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 12442–12443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kikuchi N; Kolpashchikov DM, Split Spinach Aptamer for Highly Selective Recognition of DNA and RNA at Ambient Temperatures. ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 1589–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kikuchi N; Kolpashchikov DM, A universal split spinach aptamer (USSA) for nucleic acid analysis and DNA computation. Chem. Comm 2017, 53, 4977–4980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sando S; Narita A; Aoyama Y, Light-up Hoechst-DNA aptamer pair: Generation of an aptamer-selective fluorophore from a conventional DNA-staining dye. Chembiochem 2007, 8, 1795–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kato T; Shimada I; Kimura R; Hyuga M, Light-up fluorophore-DNA aptamer pair for label-free turn-on aptamer sensors. Chem. Comm 2016, 52, 4041–4044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diwu Z; Lu Y; Zhang C; Klaubert DH; Haugland RP, Fluorescent Molecular Probes II. The Synthesis, Spectral Properties and Use of Fluorescent Solvatochromic Dapoxyl Dyes. Photochemistry and Photobiology 1997, 66, 424–431. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y; Heym B; Allen B; Young D; Cole S, The catalase peroxidase gene and isoniazid resistance of mycobacterium-tuberculosis. Nature 1992, 358, 591–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nguyen C; Grimes J; Gerasimova YV; Kolpashchikov DM, Molecular beacon-based tricomponent probe for SNP analysis in folded nucleic acids. Chemistry: A European J. 2011, 17, 13052–13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma Y, Teng F, Libera M. Solid-Phase Nucleic Acid Sequence-Based Amplification and Length-Scale Effects during RNA Amplification. Anal. Chem 2018, 90, 6532–6539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reinholt SJ; Behrent A; Greene C; Kalfe A; Baeumner AJ; Isolation and amplification of mRNA within a simple microfluidic lab on a chip. Anal. Chem 2014, 86, 849–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mader A, Riehle U, Brandstetter T, Stickeler E, zur Hausen A, Rühe J. Microarray-based amplification and detection of RNA by nucleic acid sequence based amplification. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2010, 397, 3533–3541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pai NP; Vadnais C; Denkinger C; Engel N; Pai M PLoS Med.2012, 9, e1001306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bengtson HN; Kolpashchikov DM Chembiochem 2014, 15, 228–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lake A, Shang S, Kolpashchikov DM Molecular logic gates connected through DNA four-way junctions. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010. 49, 4459–4462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kolpashchikov DM Binary probes for nucleic acid analysis Chem. Rev 2010, 110, 4709–4723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.