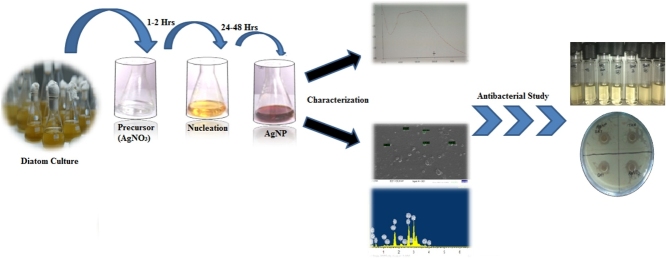

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antibacterial assay, Diatoms, Green synthesis, Nanotechnology, Silver nanoparticle

Highlights

-

•

Marine Diatoms have been envisaged for AgNP synthesis.

-

•

The average size of AgNP ranges from 150 to 350 nm.

-

•

Diatom based AgNP exhibits excellent biocidal activity.

-

•

These AgNP showed inhibition against both Gram-positive and Gram negative bacteria.

Abstract

Diatoms are a reservoir of metabolites with diverse applications and silver nanoparticle (AgNP) from diatoms holds immense therapeutic potentials against pathogenic microbes owing to their silica frustules. In the present study, Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp were used for synthesis of AgNP. The average particle size of AgNP synthesized was 149.03 ± 3.0 nm, 186.73 ± 4.9 nm, and 239.46 ± 44.3 nm as reported in DLS whereas 148.3 ± 46.8 nm, 238.0 ± 60.9 nm, and 359.8 ± 92.33 nm in SEM respectively. EDX analysis strongly indicates the confirmation of AgNP displaying a sharp peak of Ag+ ions within the spectra. High negative zeta potential values indicate a substantial degree of stabilization even after three months. The antibacterial efficacy of biosynthesized AgNP tested against Aeromonas sp., Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumonia exhibits broad-spectrum antibacterial activity. This study encourages the synthesis of diatom based AgNP for a variety of applications owing least toxicity and biodegradable nature.

1. Introduction

The impressive symbiosis stuck between technology and medical sciences unlock new front lines in the endlessly rising field of nanotechnology. Nano-biotechnology is the emerging topic dealing with the fabrication of nanoparticles integrating biological components thus influencing the nature of bulk material by modulating their atomic or molecular structures on the nanoscale [1]. The metal-based nanoparticle has attracted great attention that seems to be the building blocks of the next-generation technology because of their unique properties like the large surface area to volume ratio, high surface reaction activity, and strong thermal, mechanical stability, etc [2]. Though physio-chemical methods have been proposed for the synthesis of AgNP such as sol-gel, chemical, photochemical reduction, electrochemical method, laser ablation, ion sputtering, etc. However, these methods suffer from several drawbacks such as require toxic and expensive chemicals, complex synthetic route, release health-hazards by-products, thus leading to high risk. In contrast, biological synthesis is high on demand since they are non-toxic, eco-friendly, biocompatible, and commercially feasible [3,4]. Currently, naturally derived agents like plant extracts, algae, fungi, bacteria, yeast, enzymes, biopolymers, etc. are widely used for the synthesis of nanoparticle owing to their excellent reducing and capping behavior [2]. Phyconanotechnology is the upcoming exciting research area providing widespread opportunity in the synthesis of algae-based nanoparticles [5]. Diatoms algae are the most enduring system for the green synthesis of nanoparticles be it metallic nanoparticles, nanostructured polymers, or a diverse array of new nanomaterials [6].

Diatoms are unicellular, eukaryotic microalgae, ubiquitously found in the aqueous environment belong to class Bacillariophyceae with size ranges from 2−200 μm. More than 200,000 species of diatoms have been found across the globe [7]. They play a key role in total carbon fixation and serve as a food web for the entire aquatic ecosystem [8]. The most characteristic feature of diatoms is their silica cell wall known as frustules which they consume from the environment at a concentration that is less than 1μM and condenses it into their cell wall by silicon acid transporters (SITs) [9,10]. Diatoms are reported to have antibacterial [11], anticancer [12], antioxidants [13], and anti-inflammatory compounds [14], etc. Thus, all these qualities of diatom make them an outstanding aquatic body for nanotechnology research and applications.

Silver (Ag) metal has been used since ancient times for various applications such as a wound-healing agent in form of Ag plates, treatment of ulcer [15,16], and 1% solution of silver nitrate (AgNO3) as a neonatal eye drop to treat the eye infection [16,17]. Ag is the best conductor of electricity, but its high price restricts its use in the electrical industry. Among gold (Au), silver (Ag), palladium (Pd), platinum (Pt), iron (Fe), cadmium (Cd), titanium oxide (TiO2), zinc oxide (ZnO), and Ag-Au bimetallic nanoparticles, the AgNP plays an enormous and very effective role as it has unique thermal, optical, electrical and biocidal properties [18]. Due to their strong biocidal activity, it is used in the medical field to kill disease-causing microbes that have become several antibiotics, which is a great concern, therefore it is essential to develop a new technique to control pathogenic microbes [19]. It is reported that AgNP can control the growth of bacteria by interacting with its cell wall and destroy it thus inhibit the protein synthesis leading to cell death [20,21]. AgNP also utilized in wastewater remediation or dye effluent treatment, biomedical field, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, beverages, electronics components, dentistry, and wound healing [[22], [23], [24]].

Since the nano-silver is becoming the center point of the nano-industry, the biologically synthesized AgNP has been in great demand owing to its excellent antimicrobial property. AgNP have been synthesized from a different class of algae i.e. Cyanophyceae, Chlorophyceae, Rhodophyceae, and Phaeophyceae but diatoms (Bacillariophyceae) mediated AgNP is least studied since they enhance the activity of Ag to kill pathogenic microbes [5,25]. In the previous studies, Navicula utilized for AgNp synthesis intended for ammonia sensing [26]. Wishkerman et al. synthesized AgNP from Phaeodactylum tricornutum with the hope towards increase usage of AgNP for research and development purposes [6]. Garcia et al. investigated the detection of AgNPs in Thalassiosira pseudonana [27], several others have studied the toxic effects of AgNP in the diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana and Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp., [28], diatom Thalassiosira sp., Scenedesmus sp., [29], and Chaetoceros curvisetus [30]. Satishkumar et al., synthesized AgNP from bloom forming Trichodesmium erythraeum and studied its biological potential [31]. AgNP were also synthesized from Amphora, Navicula atamus, and Diadesmis gallica for various biotechnological applications [32,33]. Gupta et al., fabricated peptide mediated AgNP over the diatom surface [34]. All these have proved that biological synthesis is an easy and efficient method for different of nanoparticle synthesis.

This work demonstrates the green synthesis of AgNP from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp. The antibacterial activity of AgNP has been determined with the aim towards exploring the controlling capacity against disease-causing bacteria such as Aeromonas sp., Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pneumonia.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

All the chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade with maximum purity and obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, USA).

2.2. Preparation of diatom culture

In this study, three diatoms namely Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp., belonging to group Bacillariophyceae were isolated from the coast of Vishakhapatnam (17°6868′N, 83°2185′E) and Rameshwaram, India (92°876′ N, 79°3129′ E). The species were cultured in 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing artificial seawater enriched with f/2-Si media (Guillard and Ryther, 1962), at pH 8.3 and maintained in 12:12 light and dark conditions at a temperature of 23ºC with a luminous intensity of 100 μmol m−2 s-1 (Photoperiod cyclic timer, Genetix) and kept in Diatom Research Laboratory, AUUP, Noida, India.

2.3. Synthesis of AgNP from diatoms

The AgNP was synthesized from three diatoms species (Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp.) using AgNO3 as a precursor. The harvested biomass of each diatom species added slowly to the aqueous solution of AgNO3 with continues stirring separately. Initial color density changes from colorless to pale pink in 1−2 h which gradually changes to red brown after incubation at room temperature for 24−48 hours in the presence of light. The intensity of the color changes with time thus confirms the synthesis of AgNP [35].

2.4. Characterization of silver nonoparticles

2.4.1. UV–vis spectroscopy

The biosynthesis of AgNP was confirmed by taking absorption spectra from 300−800 nm using UV–vis spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1800) using a quartz cuvette with 1 cm path length and AgNO3 was taken as control. A known volume of the red-brown reaction mixture was taken, and its spectra were recorded to observe the bio reduction of Ag+ ions in the aqueous solution. The characteristic surface plasmon resonance (SPR) band of the biosynthesized AgNPs was noted which confirm the synthesis of AgNP [34].

2.4.2. Particle size and Zeta potential

The particle size distribution and zeta potential were calculated using Debye- Scherrer’s formula (L = 0.9 k/b cosh h) on a Malvern Zetasizer - Nano ZS (Malvern, UK) instrument with backscatter detection (173°), controlled by Dispersion Technology Software (DTS 5.03, Malvern, UK). 1 mL aliquot of reaction mixtures were diluted with double distilled water was taken and placed carefully in a typical cell to avoid air bubbles while electrodes on both sides of the cell holder provide necessary voltage to perform electrophoresis. The zeta potential was calculated automatically by the instrument at 25 °C using the henry equation [36]. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

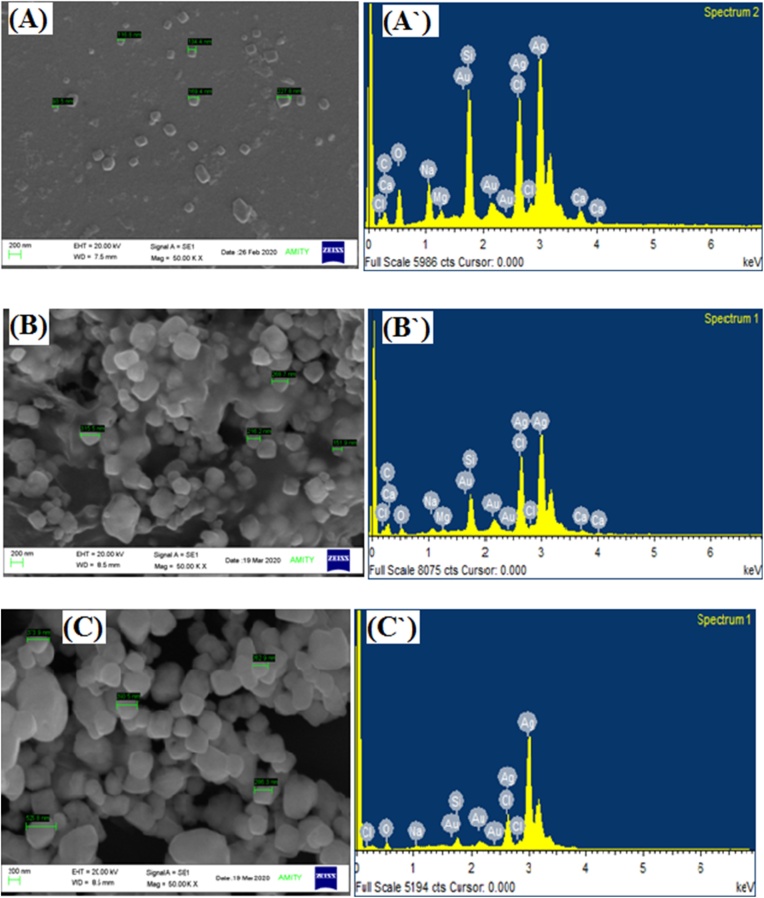

2.4.3. SEM-EDX analysis

The surface morphologies consisting of shape, size, and aggregates formation were analyzed through the Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) examination. The dried specimen was first suspended in ethanol, mounted on stubs and sputter-coated with gold and were investigated on SEM (ZEISS EVO 1800, Germany), operating at 20.00 kV arranged with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) model [1,33]. The corresponding EDX spectra were also taken for the elemental analysis of a sample.

2.5. Antibacterial assay

The antibacterial activity of AgNP was tested using the agar well diffusion method and microdilution assay method against both Gram-positive (Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Staphyloccocus aureus) and Gram-negative bacteria (Aeromonas and E. coli) obtained from culture collection center IMTECH, Chandigarh, India. Briefly, 10 mL of broth was taken in test tubes and the loop full bacteria were transferred and incubated overnight at 32 °C in a bacteriology incubator (Relitech, India). The overnight grown bacteria were further diluted to match 0.5 Mc Farland standard turbidity [37]. Microdilution assay was performed according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute [38] where the serial dilution was prepared using the broth. Similarly, in the agar well diffusion method, the bacteria were spread on agar plates then wells were made by using sterilized micropipette tips. In each well approx. 50 μl of each AgNP were loaded including AgNO3 as control. Then the plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C. A clear zone of inhibition (diameter) was then measured in millimeters (mm) [39].

3. Result and discussions

3.1. UV–vis spectroscopy analysis

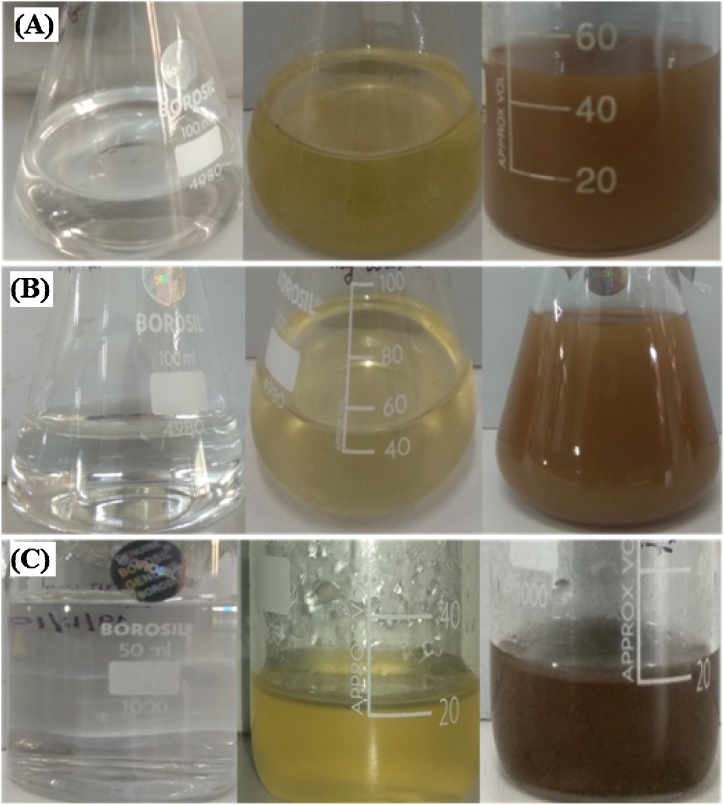

Herein, AgNO3 and Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., Thalassiosira sp., was utilized for the synthesis of AgNP. A known amount of harvested biomass was slowly added to the AgNO3 solution under continuous stirring at room temperature. A change in color was observed from colorless to pale yellow after 1−2 hours which then gradually converted to reddish-brown following incubation for 48 h as presented in Fig. 1. No color change was observed in AgNO3 solution taken as control. The change in color demarcates a visible sign for the initiation of reaction followed by nucleation and growth of nanoparticle wherein neighboring nucleonic particle associate together thereby forming thermodynamically stable AgNP [40,41].

Fig. 1.

Synthesis of AgNP from (A) Chaetoceros sp., (B) Skeletonema sp., and (C) Thalassiosira sp. (Change in color intensity from colorless to reddish brown confirm nanoparticle synthesis).

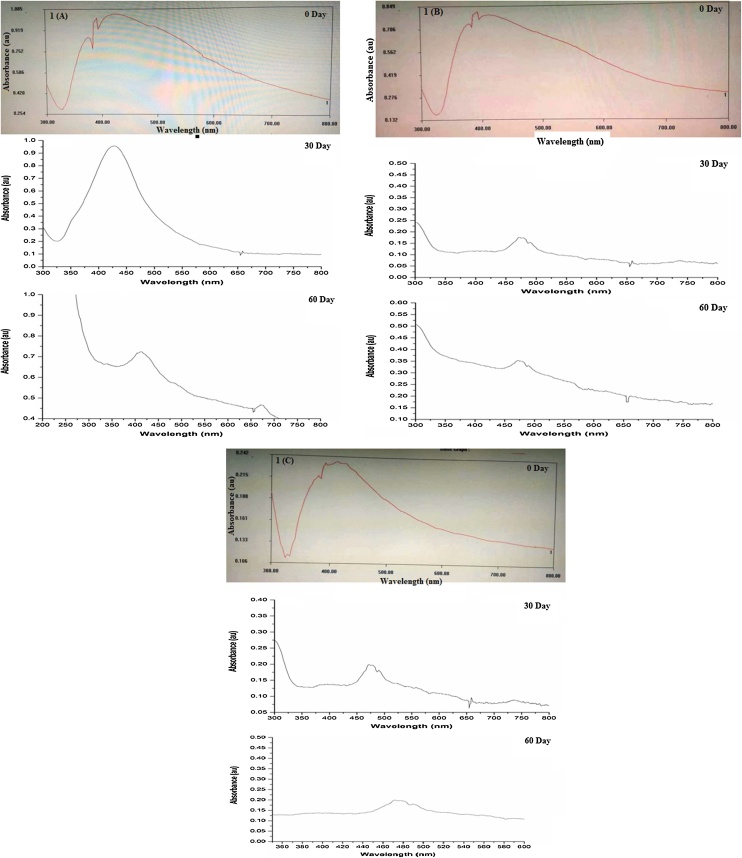

To further verify the results, the biosynthesized AgNPs were subjected to UV–vis spectroscopy analysis to confirm the formation and stability of nanoparticles. The absorption spectra which produced a maximum absorption peak at λ max 412 nm, 425 nm, and 430 nm revealed biosynthesized AgNPs from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., Thalassiosira sp., respectively as presented in Fig. 2. A broad peak obtained in the visible range is due to the change in color resulting from the excitation of free electrons that establish the SPR band because the conduction band and valence band lie close to each other in the case of metallic nanoparticles like AgNP. Light is a crucial factor for the bioreduction of Ag+ ions into stable Agº on diatoms cells during the participation of light-sensitive biomolecules in the reaction mechanism [26,31]. Principally, the radiations interact with metallic ions and facilitate the transition from lower energy to higher energy state thus an SPR band is obtained which determines the size and shape of metallic nanoparticles to a certain nanometer range [42,43]. According to Mie theory, the information regarding the size can be determined from the UV-spectra, the SPR band of AgNP from Chaeteroceros sp., obtained at a shorter wavelength of 412 nm, whereas the SPR band for AgNP from Skeletonema sp. and Thalassiosira sp. further shifts to the longer region of wavelength at 425 and 430 nm which is in good agreement with size estimated from DLS and SEM analysis [44]. The stability of biosynthesized AgNPs suspensions was further investigated by taking the absorption spectra at different time intervals for 2 months. The SPR band of biosynthesized AgNP from Chaeteroceros sp. has shown only a slight shift towards the longer region of wavelength and its size remains stable which is corroborated with the more negative surface charge. However, the band of AgNP from Skeletonema sp. and Thalassiosira sp. shifts strongly to the longer region and got weaken thus confirm their unstable nature supported by characterization techniques. Moreover, increasing the peak area of the band implies with the decrease in interparticle space thus confirm the aggregation leading to more particle size and less surface charge in case of AgNP synthesized from Skeletonema sp. and Thalassiosira sp. [45] The AgNP synthesized from Chaeteroceros sp. remains stable for a long time owing to its more surface charge which is preventing the aggregation of two particles due to coulombic repulsion leading to a metastable single particles solution. When van der waals force is dominant outside the metastable state, the more clusters will form leading to larger particle size as in the case of AgNP synthesized from Skeletonema sp. and Thalassiosira sp. as presented in Fig. 1[46].

Fig. 2.

UV–vis spectra of biosynthesized AgNPs synthesized from 1 (A) Chaetoceros sp., 1(B) Skeletonema sp., and 1(C) Thalssiosira sp. (The results show the stability studies for a period of 2 months. AgNP synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., is highly stable as reflected by UV–vis spectra whereas other biosynthesized AgNPs form aggregates showing a major shift in peak to the longer region of wavelength).

Diatoms phycoremediate heavy metals and eliminate them from the environment and this feature predicts diatoms as a model species for the fabrication of metallic nanoparticles [8]. Diatoms are equipped with lots of essential bioactive compounds like carbohydrates, proteins, minerals, oils, fats, and polyunsaturated fatty acids which have been acted as reducing and stabilizing agents [39]. They obtain golden brown color due to the presence of photosynthetic pigments such as fucoxanthin and Chlorophyll-c. The hydroxyl group present in fucoxanthin makes it a strong reducing agent along with proteins and other bioactive compounds in the presence of light which helps in the reduction of Ag+ ions into stable Agº inside diatom cells. The hydroxyl group of silanol is also responsible for the formation of AgNP as shown in the equation given below [47].

| AgNO3 +H2O → Ag+ + NO3− | (1) |

| Ag+ + Fucoxanthin /(−OH) → AgNP | (2) |

The nanosized particle of Ag has been developed which can be useful for various applications such as antimicrobials agents, healthcare and food industry, textile coatings and the fabrication of electronic devices [48].

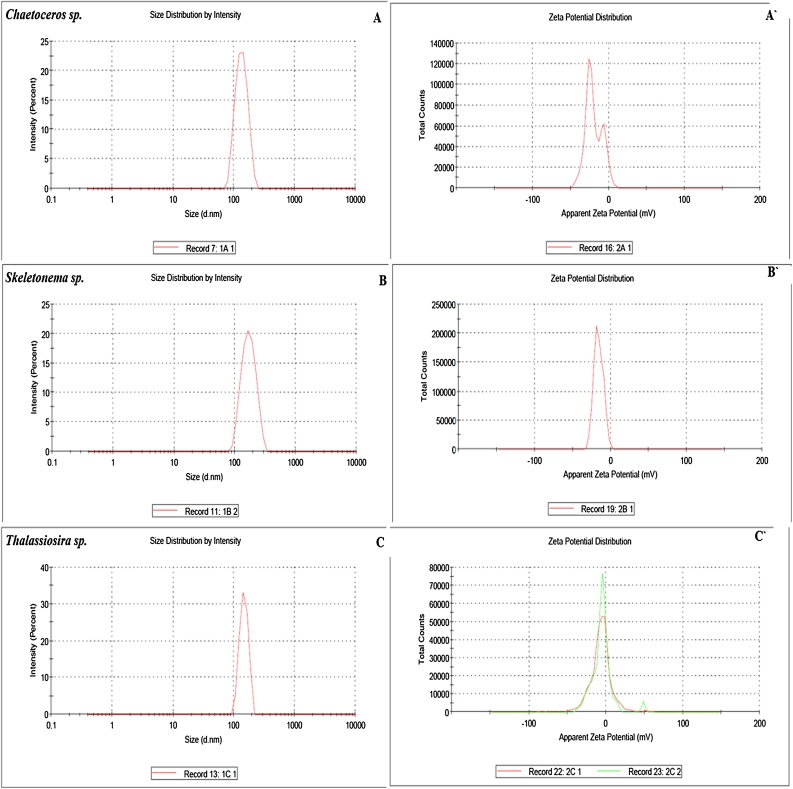

3.2. Particle size and zeta potential analysis

The particle size distributions obtained from Dynamic Light Scattering analysis (DLS) and surface charge investigations of the biosynthesized AgNPs were analyzed by particle size analyzer in an aqueous solution. The filtered and purified nanoparticles were dispersed in double distilled water at neutral pH and investigated utilizing a Malvern instrument representing size. The average particle size of AgNPs synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp., showing maximum intensity at 149.03 ± 3.04 nm, 186.73 ± 4.90 nm, and 239.46 ± 44.30 nm respectively. The graphs indicating an exceptionally homogenous uniform distribution curve of nanoparticle size [49]. The nanoparticle shows no sign of aggregation upon storage for three months at room temperature [50]. The particle size discussed here agreed-upon size obtained from SEM analysis as presented in Fig. 3 and Table 1.

Fig. 3.

DLS profile (A, B, C) and Zeta potential (A`, B`, C`) of AgNP synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp.

Table 1.

DLS and Zeta potential data obtained AgNP synthesized from diatoms.

| S. No. | Type of AgNP | Particle size (DLS) | Zeta potential (ζ) | Shape |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Chaetoceros sp. | 149.03 ± 3.04 | −19.4 ± 0.10 | Rectangular or square |

| 2. | Skeletonema sp. | 186.73 ± 4.90 | −16.33 ± 0.55 | Non spherical |

| 3. | Thalassiosira sp. | 239.46 ± 44.3 | −5.67 ± 0.467 | Non spherical |

The stability was studied by zeta potential measurements indicating charge present on the surface of the biosynthesized nanoparticle and their corresponding stability. The zeta potential of AgNPs synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp., observed to be in the order of -19.4 ± 0.10 > 16.33 ± 0.55> -5.67 ± 0.467 respectively as presented in Fig. 3 and Table 1. This suggests that AgNPs synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., is more stable due to more negative charge on its surface followed by Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp. The biosynthesized Nanoparticles shows no sign of aggregation even after three months of storage thus representing the substantial degree of stabilization [51] which might be due to the existence of numerous bioactive compounds present in the diatom cells which are acting as strong capping agents thus stabilize the AgNPs to a greater extent [52,53].

3.3. Surface morphological studies with SEM-EDX analysis

The shape, size, and surface morphology of diatoms mediated AgNP on frustules were characterized by SEM analysis as presented in the Fig. 4. The SEM micrograph validates the particle size showing the mean diameter of AgNPs synthesized from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp., was 148.3 ± 46.8 nm, 238.0 ± 60.9 nm, and 359.8 ± 92.33 nm which can be attributed to the UV spectra dispersed all over the sample. The shape of Chaeotoceros sp. is roughly rectangular to square, whereas Skeletonema sp. and Thalassiosira sp. are regular as confirmed by SEM analysis. Since the nanoparticle is dispersed uniformly throughout the sample without any direct contact indicates the fabrication through metabolites acting as capping and reducing agents that assist in preventing agglomeration of the nanoparticle along with boosting of antibacterial activity [50,54]. Previous studies also demonstrated the biosynthesis of AgNP attaining different shapes therefore the results confirmed that metabolites from diatom cells acting as strong reducing and capping agents in the biological synthesis of the nanoparticle [55]. A noteworthy point was taken out from the results that not much striking difference was obtained in the particle size of DLS and SEM emphasizing that diatom cells help in the synthesis of uniform particle size. The smaller particle size shown by DLS aggregated in the formation of somewhat larger particles in the SEM studies but with a minor difference thus both DLS and SEM results complement with each other. Thus physico-chemical properties do not have a direct influence on the particle size as shown in Fig. 3 [56].

Fig. 4.

SEM micrograph (A-C) and corresponding EDX spectra (A`-C`) of AgNP synthesized from A. Chaetoceros sp., B.Skeletonema sp., C. Thalssiosira sp.

To further establish the presence of Ag + ions in the biosynthesized AgNP, the Energy Dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectra were recorded to investigate the weight %, atomic %, and characteristics energy levels of the nanoparticle composition. The occurrence of a pointed spectral signal in the region of 2.5–3 KeV denotes the presence of Ag + ions thus confirm the absorption of nano-crystallites in all three species. The spectra also illustrate the relative proportion of Si and O due to frustules whereas C peak signifies organic matter together with other elements that are found in the culture media for diatom growth. Therefore, results suggest that the presence of Si, C, and O band likely to originate from diatom cells that capped the nanoparticle thereby confirming the biosynthesis of AgNP as presented in Fig. 3 [26,31].

3.4. Determination of antibacterial activity of biosynthesized AgNPs

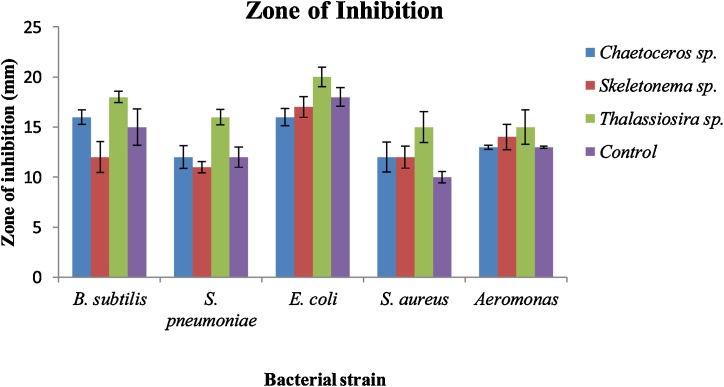

The AgNP exhibits antibacterial activity in a range of different magnitudes. The biological activity of AgNP synthesized from marine diatoms was tested against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. The highest zone of inhibition shown by Thalassiosira sp. was observed to be in the order of 20±1.0 mm>18±0.6 mm >16±0.8 mm >15±1.7 mm ∼15±1.5 mm against E. coli, B. subtilis, S. pneumonia, Aeromonas sp., and S. aureus. Skeletonema sp. demonstrate a high zone of inhibition in the order of 17 ± 1.0 mm >14 ± 1.3 mm >12 ± 1.5 mm ∼12 ± 1.1 mm >11 ± 10.6 mm against E. coli, Aeromonas sp., B. subtilis, S. aureus, and S. pneumonia, whereas Chaetoceros sp. shows in the order of 16 ± 0.9 mm ∼16 ± 0.7 mm >13 ± 0.2 mm >12 ± 1.5 mm ∼12 ± 0.7 mm against E. coli, B. subtilis, Aeromonas sp., S. aureus, and S. pneumonia respectively. The results indicate that AgNP synthesized from Thalassiosira sp. show strong antibacterial efficacy as compared to Skeletonema sp. and Chaetoceros sp. which also show very good antibacterial activity on a similar note but lower than Thalassiosira sp. comparatively. AgNO3 which was taken as control also tested against these bacteria exhibits antibacterial activity by showing an inhibition zone, but it was not as strong as it was with biosynthesized AgNPs. The data shown in Fig. 5 and Table 2 sum up the results obtained from the antibacterial study. In the results, Thalassiosira sp. shows the utmost inhibition in contrast to AgNO3 against both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria but the inhibition zone for Skeletonema sp., Chaetoceros sp., and AgNO3 were somewhat similar and comparable although in most cases it was smaller than Skeletonema sp., Chaetoceros sp., mediated AgNP. In brief, biosynthesized AgNP from Thalassiosira sp. expressed very high antibacterial activity after Skeletonema sp., Chaetoceros sp., then control experiment [57].

Fig. 5.

Inhibition zone of AgNP synthesized from marine diatoms. The results shows the average of 3 experiments. Errors bars represent standard deviation of the mean.

Table 2.

Inhibition zone of AgNPs against Gram -ve and Gram + ve bacteria.

| Bacteria | Diatoms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalassiosira | Skeletonema | Chaetceros | Control | |

| Bacillus subtilis | <15.625 μg/mL | <15.625 μg/mL | <15.625 μg/mL | 12.5 μg/mL |

| S. pneumoniae | <7.81 μg/mL | 7.81 μg/mL | <7.81 μg/mL | 12.5 μg/mL |

| E. coli | <16 μg/mL | 2 μg/mL | 4 μg/mL | <5.2125 μg/mL |

| S. aureus | <15.625 μg/mL | <15.625 μg/mL | <15.625 μg/mL | 8.35 μg/mL |

| Aeromonas | 3.125 μg/mL | 3.125 μg/mL | 6.25 μg/mL | 5.21 μg/mL |

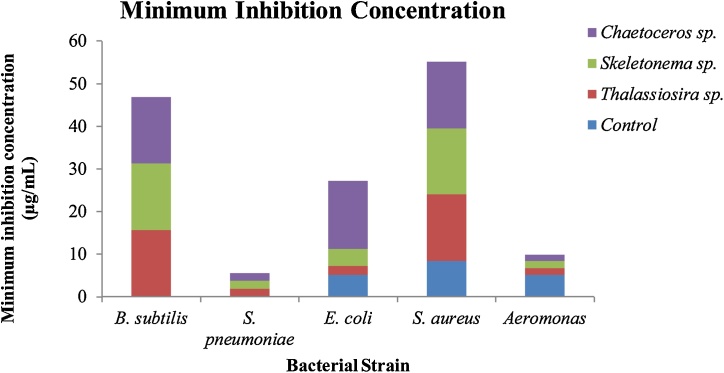

The antibacterial activity of biosynthesized AgNPs was also confirmed by the broth dilution method according to Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute [38] which assists in investigating inhibition at various concentrations of AgNPs thus determines Minimum Inhibition Concentration (MIC) as presented in Fig. 6 and Table 3. A working stock of biosynthesized AgNPs was serially diluted to obtain a concentration in the range of 100−1.5 μg/mL. The prepared bacterial suspension was added to all the tubes except the control tube and incubated overnight at 37 °C, the physiological temperature encouraging the growth of bacterial strains. The next day, all the tubes were analyzed for each concentration of AgNPs, and observation was recorded. AgNP against Gram-positive bacteria showed MIC in the range of <15.625 μg/mL to <7.81 μg/mL whereas in the case of Gram-negative bacteria it was between <16 μg/mL to 2 μg/mL. Thus, results indicate AgNP yields high antibacterial activity which is resistant towards a range of bacteria strains as presented in Table 3 [1].

Fig. 6.

MIC of AgNP synthesized from marine diatoms.

Table 3.

MIC of AgNPs against Gram negative and Gram-positive bacteria.

| Bacteria | Diatoms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thalassiosira | Skeletonema | Chaetoceros | Control | |

| Bacillus subtilis | 18 mm ± 0.6 | 12 mm ± 1.5 | 16 mm ± 0.7 | 15 mm ± 1.8 |

| S. pneumoniae | 16 mm ± 0.8 | 11 mm ± 0.6 | 12 mm ± 1.2 | 12 mm ± 1.0 |

| E. coli | 20 mm ± 1.0 | 17 mm ± 1.0 | 16 mm ± 0.9 | 17 mm ± 0.9 |

| S. aureus | 15 mm ± 1.5 | 12 mm ± 1.1 | 12 mm ± 1.5 | 10 mm ± 0.6 |

| Aeromonas | 15 mm ± 1.7 | 14mm ± 1.3 | 13 mm ± 0.2 | 13 mm ± 0.1 |

In the previous studies, AgNP has shown excellent antibacterial efficacy due to its large surface area than AgNO3. It is hypothesized that AgNP enter deep inside the microorganism by attaching on its cell membrane and disturb its machinery [58]. Another report suggests that nanoparticles release Ag+ ions, that have bactericidal effects thus, enhance the bactericidal activity of the AgNP [59,60]. Synthesis of AgNP from Amphora sp. exhibits strong antibacterial activity against E. coli (17 mm), B. stearothermophilus (16 mm), and S. mutans (12 mm) respectively [33]. In another report, the biosynthesized AgNP from Brevibacterium frigoritolerans zone of inhibition against C. albicans (24 ± 1.4 mm), V. parahaemolyticus (25 ± 1.0 mm), S. enteric (12 ± 0.6 mm), B. anthracis (15 ± 0.8 mm), B. cereus (15 ± 0.5 mm), and E. coli (11 ± 0.2 mm) [57]. Fungus mediated AgNP displayed a good zone of inhibition of 10 mm, 10 mm, 7 mm, 6 mm, 9 mm, 8 mm, and 7 mm against E. coli, Staphyloccocus sp., Morganella morgenii, Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enteritidis, and Shigella boydii [61]. Report by Jain et al., indicate that AgNP inhibits the growth of microorganism at very low concentration [62]. Aboelfetoh et al., studied the antibacterial activity of AgNP synthesized using green algae (Caulerpa serrulata) exhibit a maximum inhibition zone against E. coli (21 mm) while the minimum inhibition zone against S. typhi (10 mm) and also added that AgNP strongly attached to the bacterial cell wall damaging and affecting the permeability of plasma membrane [43].

Although AgNP exhibits very strong bactericidal effects, the correct mechanism is still under investigation. However, it is hypothesized that when AgNP attaches to the bacteria cell wall, it causes some structural changes inside the membrane by the formation of free radicals confirmed by electron spin resonance studies. The release of Ag+ ions causing death because it attached to the negatively charged bacterial cell membrane apart from this electrostatic force could also be the factor for the interaction of AgNP with the bacteria [60].

The leading patron of AgNP is the pharmaceutical sector. They employed AgNP widely in the preparation of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) for the treatment of various diseases such as cancer and diabetes [63]. Diatom mediated AgNP exhibits strong cytotoxic activity against dangerous microorganisms because silicon made frustules in the diatom cell wall improved SPR of the AgNP thus showing unique therapeutic property against chronic disease due to the synergistic effect of the AgNP with the bacteria surface [64]. According to DBT, India guidelines on nanopharmaceuticals, a material show activity beyond the nanoscale range from 100−1000 nm ought to be considered as a nanomaterial for the development of nanopharmaceuticals (dbtindia.gov.in) [65]. Thus, it is essential to exploit the pharmacological activities of marine living organisms for clinical applications owing to increased bioavailability, enhanced drug apparent solubility, and dissolution rate [66].

4. Conclusion

Herein, a cost-effective and eco-friendly route for the biological synthesis of AgNP has been proposed from Chaetoceros sp., Skeletonema sp., and Thalassiosira sp. The bioactive compounds from diatoms help to reduce AgNO3 into a stable AgNP. Through UV–vis spectroscopy, the formation of AgNP has been confirmed whereas DLS, SEM, and EDX demonstrated the size, shape, and validated the presence of Ag+ ions. Stability was investigated by Zeta potential measurements. Furthermore, biosynthesized AgNP showed excellent bactericidal activity against both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria respectively. In the future, diatoms mediated nanoparticles could be a potential tool for environmental, pharmaceutical, medical, and biotechnological applications.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Bharti Mishra: Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - original draft. Abhishek Saxena: Conceptualization, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Archana Tiwari: Conceptualization, Visualization, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), New Delhi, India for providing financial assistance under project Grant No: BT/PR/15650/AAQ/3/815/2016 for conducting research.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.btre.2020.e00571.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Arya A., Gupta K., Chundawat T.S., Vaya D. Biogenic synthesis of copper and silver nanoparticles using green alga Botryococcus braunii and its antimicrobial activity. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2018;2018:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/7879403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pugazhendhi A., Edison T.N.J.I., Karuppusamy I., Kathirvel B. Inorganic nanoparticles: a potential cancer therapy for human welfare. Int. J. Pharm. 2018;539:104–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Duran N., Marcato P.D., Duran M., Yadav A., Gade A., Rai M. Mechanistic aspects in the biogenic synthesis of extracellular metal nanoparticles by peptides, bacteria, fungi, and plants. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011;90:1609–1624. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3249-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Encarnacion E.B., Gonzalez C.E.E., Anzaldo X.G.V., Cardenas M.E.C., Ramirez J.R.M. Silver nanoparticles synthesized through green methods using Escherichia coli top 10 (Ec-Ts) growth culture medium exhibit antimicrobial properties against nongrowing bacterial strains. J. Nanomater. 2019;2019:8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khanna P., Kaur A., Goyal D. Algae-based metallic nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization and applications. J. Microbiol. Meth. 2019;163 doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2019.105656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wishkerman A., Arad M.S. Production of silver nanoparticles by the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Proc. SPIE. 2017;10248 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanchez C., Cristóbal G., Bueno G. Diatom identification including life cycle stages through morphological and texture descriptors. Peer J. 2019;7:e6770. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marella T.K., Saxena A., Tiwari A. Diatom mediated heavy metal remediation: a review. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;305 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marella T.K., Lopez-Pacheco I.Y., Parra-Saldívar R., Dixit S., Tiwari A. Wealth from waste: diatoms as tools for phycoremediation of wastewater and for obtaining value from the biomass. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;724 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marella T.K., Tiwari A. Marine diatom Thalassiosira weissflogii based biorefinery for co-production of eicosapentaenoic acid and fucoxanthin. Bioresour. Technol. 2020;307 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauritano C., Martín J., Cruz M.D.L., Reyes F., Romano G., Ianora A. First identification of marine diatoms with anti-tuberculosis activity. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:2284. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andrade K.A.M., Lauritano C., Romano G., Ianora A. Marine microalgae with anti-cancer properties. Mar. Drugs. 2018;16:165. doi: 10.3390/md16050165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smerilli A., Balzano S., Maselli A., Blasio M., Orefice I., Galasso C., Sansone C., Brunet C. Antioxidant and photoprotection networking in the coastal diatom Skeletonema marinoi. Antioxidants. 2019;8(2019):154. doi: 10.3390/antiox8060154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elagoz A.M., Ambrosino L., Lauritano C. De novo transcriptome of the diatom Cylindrotheca closterium identifies genes involved in the metabolism of anti-inflammatory compounds. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:4138. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-61007-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alexander S.K., Azencott1 R., Bodmann B.G., Bouamrani A., Chiappini C., Ferrari M., Liu X., Tasciotti E. SEM image analysis for quality control of nanoparticles. In: Jiang X., Petkov N., editors. Vol. 5702. Springer; Berlin: 2009. (Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns. CAIP 2009. Lecture Notes in Computer Science). [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGillicuddy E., Murray I., Kavanagh S., Morrison L., Fogarty A., Cormican M., Dockery P., Prendergast M., Rowan N., Morris D. Silver nanoparticles in the environment: sources, detectionand ecotoxicology. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;575:231–246. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maillard J.Y., Hartemann P. Silver as an antimicrobial: facts and gaps in knowledge. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2013;39:373–383. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2012.713323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saravanan M., Arokiyaraj S., Lakshmi T., Pugazhendhi A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Phenerochaete chrysosporium (MTCC-787) and their antibacterial activity against human pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2018;117:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sibanda T., Okoh A.I. The challenges to overcoming antibiotic resistance: plant extract as potential source as antimicrobial and resistance modifying agent. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2007;6:2886–2896. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu L., Zhu G., Zhang X. Silver nanoparticles inhibit denitrification by altering the viability and metabolic activity of Pseudomonas stutzeri. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;9 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aritonang H.F., Koleangan H., Wuntu A.D. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using aqueous extract of medicinal plants (Impatiens balsamina and Lantana camara) fresh leaves and analysis of antimicrobial activity. Int. J. Microbiol. Res. 2019;2019:8. doi: 10.1155/2019/8642303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marimuthu S., Antonisamy A.J., Malayandi S., Rajendran K., Tsai P.C., Pugazhendhi A., Ponnusamy V.K. Silver nanoparticles in dye effluent treatment: a review on synthesis, treatment methods, mechanisms, photocatalytic degradation, toxic effects and mitigation of toxicity. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 2020;205(2020) doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanmuganathan R., Karuppusamy I., Saravanan M., Muthukumar H., Ponnuchamy K., Ramkumar V.S., Pugazhendhi A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their biomedical applications - a comprehensive review. Curr. Phar. Des. 2019;25:2650–2660. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190708185506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bharti S., Mukherji S., Mukherji S. Water disinfection using fixed bed reactors packed with silver nanoparticle immobilized glass capillary tubes. Sci. Total Environ. 2019;689:991–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.06.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Terra A.L.M., Kosinski R.D.C., Moreira J.B., Costa J.A.V., Morais M.G. Microalgae biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles for application in the control of agricultural pathogens. J. Environ. Sci. Health B. 2019;54:709–716. doi: 10.1080/03601234.2019.1631098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chetia L., Kalita D., Ahmed G.A. Synthesis of Ag nanoparticles using diatom cells for ammonia sensing. Sens. Biosens. Res. 2017;16:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia C.P., Burchardt A.D., Carvalho R.N., Gilliland D., Antonio D.C., Rossi F., Lettieri T. Detection of silver nanoparticles inside marine diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana by electron microscopy and focused ion beam. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burchardt A.D., Carvalho R.N., Valente A., Nativo P., Gilliland D., Garcìa C.P., Passarella R., Pedroni V., Rossi F., Lettieri T. Effects of silver nanoparticles in diatom Thalassiosira pseudonana and cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;16(46):11336–11344. doi: 10.1021/es300989e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pham T.L. Effect of silver nanoparticles on tropical freshwater and marine microalgae. J. Chem. 2019;2019:7. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lodeiro P., Browning T.J., Achterberg E.P. Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle toxicity to the coastal marine diatom Chaetoceros curvisetus. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:10777. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11402-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sathishkumar R.S., Sundaramanickam A., Srinath R., Ramesh T., Saranya K., Meena M., Surya P. Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles by bloom forming marine microalgae Trichodesmium erythraeum and its applications in antioxidant, drug-resistant bacteria, and cytotoxicity activity. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2019;23:1180–1191. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oscar F.L., Vismaya S.K., Kumar A., Thajuddin N. 2016. Algal Nanoparticles: Synthesis and Biotechnological Potentials, Chemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jena J., Pradhan N., Dash B.P., Panda P.K., Mishra B. Pigment mediated biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles using diatom Amphora sp. and its antimicrobial activity. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2015;19:661–666. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta S., Kashyap M., Kumar V., Jain P., Vinayak V., Joshi K.B. Peptide mediated facile fabrication of silver nanoparticles over living diatom surface and its application. J. Mol. Liq. 2018;249:600–608. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mankad M., Patil G., Patel D., Patel P., Patel A. Comparative studies of sunlight mediated green synthesis of silver nanoparaticles from Azadirachta indica leaf extract and its antibacterial effect on Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae. Arabian J. Chem. 2020;13:2865–2872. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saxena A., Bhattacharya A., Kumar S., Epstein I.R., Sahney R. Biopolymer matrix for nano-encapsulation of urease – a model protein and its application in urea detection. J. Coll. Int. Sci. 2017;490:452–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gee D.M., Archera L., Smythb T.J., Flemingc G.T.A., Touzet N. Bioprospecting and LED-based spectral enhancement of antimicrobial activity of microalgae isolated from the west of Ireland. Algal Res. 2020;45 [Google Scholar]

- 38.CLSI . CLSI Supplement M100. 29th ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; Wayne, PA: 2019. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shalini A.A., Ali M.S., Anuradha V., Yogananth N., Bhuvana P. GCMS analysis and invitro antibacterial and anti-inflammatory study on methanolic extract of Thalassiosira weissflogii. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019;19 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fawcett D., Verduin J.J., Shah M., Sharma S.B., Poinern G.E.J. A review of current research into the biogenic synthesis of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles via marine algae and seagrasses. Int. J. Nanosci. 2020;2017:15. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Prasad R., Pandey R., Barman I. Engineering tailored nanoparticles with microbes: quo vadis? Nanomed. Nanobi. 2016;8:316–330. doi: 10.1002/wnan.1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shukla A.K., Iravani S. Metallic nanoparticles: green synthesis and spectroscopic characterization. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2017;15:223–231. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aboelfetoh E.F., El-Shenody R.A., Ghobara M.M. Eco-friendly synthesis of silver nanoparticles using green algae (Caulerpa serrulata): reaction optimization, catalytic and antibacterial activities. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017;189:349. doi: 10.1007/s10661-017-6033-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duque J.S., Blandon J.S., Riascos H. Localized Plasmon resonance in metal nanoparticles using Mie theory. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2017;850 012017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jha P.K. Size distribution of silver nanoparticles: UV-visible spectroscopic assessment. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. Lett. 2012;4:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moreno-Martin G., EugeniaLeón-González M., Madrid Y. Simultaneous determination of the size and concentration of AgNPs in water samples by UV–vis spectrophotometry and chemometrics tools. Talanta. 2018;188(October):393–403. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2018.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lechner C.C., Becker C.F.W. Silaffins in silica biomineralization and biomimetic silica precipitation. Mar. Drugs. 2015;13:5297–5333. doi: 10.3390/md13085297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tevan R., Govindaraju M., Jayakumar S., Govindan N., Rahim M.H.A., Maniam G.P., Ichwan S.J.A. Antimicrobial activities of silver nanoparticles bio-synthesized from diatom Amphora sp. J. Eng. Sci. Res. 2017;2:176–184. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oves M., Aslam M., Rauf M.A., Qayyum S., Qari H.A., Khan M.S., Alam M.Z., Tabrez S., Pugazhendhi A., Ismail I.M.I. Antimicrobial and anticancer activities of silver nanoparticles synthesized from the root hair extract of Phoenix dactylifera. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2018;89:429–443. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samuel M.S., Jose S., Selvarajan E., Mathimani T., Pugazhendhi A. Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Bacillus amyloliquefaciens; application for cytotoxicity effect on A549 cell line and photocatalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol. J. Phytochem. Photobiol. B. Biol. 2020;202 doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.111642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elamawi R.M., Al-Harbi R.E., Hendi A.A. Biosynthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Trichoderma longibrachiatum and their effect on phytopathogenic fungi. Egypt J. Biol. Pest. Control. 2018;28 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shanmuganathan R., Ali D.M., Prabakar D., Muthukumar H., Thajuddin N., Kumar S.S., Pugazhendhi A. An enhancement of antimicrobial efficacy of biogenic and ceftriaxone-conjugated silver nanoparticles: green approach. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shankar P.D., Shobana S., Karuppusamy I., Pugazhendhi A., Ramkumar V.S., Arvindnarayan S., Kumar G. A review on the biosynthesis of metallic nanoparticles (gold and silver) using biocomponents of microalgae: formation mechanism and applications. Enz. Microbiol. Technol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pak Z.H., Abbaspour H., Karimi N., Fattahi A. Eco-friendly synthesis and antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles using Dracocephalum moldavica seed extract. Appl. Sci. 2016;6:69. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jacob J.M., John M.S., Jacob A., Abitha P., Kumar S.S., Rajan R., Natarajan S., Pugazhendhi A. Bactericidal coating of paper towels via sustainable biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using Ocimum sanctum leaf extract. Mater. Res. Express. 2019;6 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pugazhendhi A., Prabakar D., Jacob J.M., Karuppusamy I., Saratale R.G. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles using Gelidium amansii and its antimicrobial property against various pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh S.P., Bhargava C.S.Dr., Dubey V.Dr., Mishra A., Singh Y. Silver nanoparticles: biomedical applications, toxicity, and safety issues. Int. J. Res. Pharm Pharm. Sci. 2017;2:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saravanan M., Barikb S.K., Ali D.M., Prakashd P., Pugazhendhie A. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles from Bacillus brevis (NCIM 2533) and their antibacterial activity against pathogenic bacteria. Microb. Pathog. 2018;116:221–226. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morones J.R., Elechiguerra J.L., Camacho A., Holt K., Kouri J.B., Ramirez J.T., Yacaman M.J. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology. 2005;16:2346–2353. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/16/10/059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qais F.A., Shafiq A., Khan H.M., Husain F.M., Khan R.A., Alenazi B., Alsalme A., Ahmad I. Antibacterial effect of silver nanoparticles synthesized using Murraya koenigii (L.) against multidrug-resistant pathogens. Bioinorg. Chem. Appl. 2019;2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/4649506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gond S.K., Mishra A., Verma S.K., Sharma V.K., Kharwar R.N. Synthesis and characterization of antimicrobial silver nanoparticles by an endophytic fungus isolated from Nyctanthes arbor-tristis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., India, Sect. B Biol. Sci. 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jain J., Arora S., Rajwade J.M., Omray P., Khandelwal S., Paknikar K.M. Silver nanoparticles in therapeutics: development of an antimicrobial gel formulation for topical use. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;6:1388–1401. doi: 10.1021/mp900056g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mathur P., Jha S., Ramteke S., Jain N.K. Pharmaceutical aspects of silver nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018;46:115–126. doi: 10.1080/21691401.2017.1414825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kratošová G., Vávra I., Horská K., Zˇivotský O., Neˇmcová Y., Bohunická M., Slabotinský J., Rosenbergová K., Kadilak A., Schröfe A. Synthesis of metallic nanoparticles by diatoms–prospects and applications. In: Rai M., Posten C., editors. Green Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles: Mechanisms and Applications. © CAB International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 65.2019. Guidelines for Evaluation of Nanopharmaceuticals in India.http://dbtindia.gov.in/sites/default/files/uploadfiles/Guidelines_For_Evaluation_of_Nanopharmaceuticals_in_India_24.10.19.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 66.Macha I.J., Ben-Nissan B., Müller W.H., Cazalbou S. Vol. 149. 2019. Marine nanopharmaceuticals for drug delivery and targeting; pp. 207–221. (Marine-Derived Biomaterials for Tissue Engineering Applications). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.