Abstract

Disinfection is an important process to make the water free from harmful pathogenic substances, but sometimes it results in the formation of harmful by-products. Development of predictive models is required to define the concentration of THMs in pool water. Majority of studies reported inhalation to be the most significant THMs exposure route which is more likely to be dependent upon the concentration of THMs in pool water and in air. THMs concentration in the analyzed pool water samples and in air was found to be 197.18 ± 16.31 μg L−1 and 0.033 μg m3–1, respectively. Statistical parameters such as high correlation coefficients, high R2 values, low standard error, and low mean square error of prediction indicated the validity of MLR based linear model over non-linear model. Therefore, linear model can be most suitably used to pre-assess and predict the THMs levels in swimming pool water. Risk estimation studies was conducted by using the united states environmental protection agency (USEPA) Swimmer Exposure Assessment Model (SWIMODEL). The lifetime time cancer risk values related to chloroform exceeded 10−6 for both the sub-population. Inhalation exposure leads to maximum risk and contributed up to 99% to total cancer risk. Risk due to other exposure pathways like accidental ingestion and skin contact was found to be negligible and insignificant. Monte Carlo simulation results revealed that the simulated THMs risk values for the studied exposure pathways lies within ±3.1% of the average risk values obtained using SWIMODEL. Hence, the risk estimates obtained using SWIMODEL seemed to be appropriate in determining the potential risk exposure of THMs on human health. Variation in input parameters like body weight (BW) and skin surface area (SA) leads to difference in risk estimates for the studied population. Non cancer risk was found to be insignificant as represented by low hazard quotient (HQ < 1) values. Through monitoring and regulations on control of THMs in swimming pool water is required to minimize the risk associated.

Keywords: Swimming pool, Chloroform, Predictive models, Risk exposure, Hazard quotient

Introduction

Disinfection of swimming pool water is essential to maintain hygienic conditions and to avoid the outbreak of waterborne diseases like typhoid and cholera [41]. Several types of disinfectants like chlorine, bleaching powder, chlorine dioxide etc., have been used of which chlorine is the most widely used in swimming pool due to its efficacy, low cost and retentive power [6, 25]. However, during the course of disinfection, chlorinated compound reacts with natural organic matter (NOM) substances of swimmer’s origin (sunscreen, mucus, urine, skin particles and hairs), and results in the formation of undesirable harmful halogenated by-products known as disinfection byproducts (DBPs) [38]. Swimming pool water serves as water matrices with high concentrations of DBPs due to constant chlorination and the persistent organic load of swimmer’s origin. The occurrence and quantity of DBPs in swimming pools is governed by several factors such as the mode of disinfection, the type and concentration of disinfectant used, the NOM content, the physicochemical characteristics of treated waters etc. [11, 22, 47, 48]. Erratic addition of substances from swimmers, inconsistent interactions of different precursors (natural and swimmers origin) and considerable extended contact time with disinfectant intensifies the complexity of pool water chlorination in comparison to typical drinking water systems [14].

Till date, more than 600 DBPs have been identified in chlorinated waters, and many of them have been designated as mutagens or probable carcinogens [27, 46, 61]. Studies reported that THMs are the most prevalent DBPs and have been recognized as potential carcinogens [5]. Epidemiological studies revealed that THMs exposure leads to an increased risk of different type of cancer like bladder, colon and rectal [16, 28, 59, 60], birth defects [42], spontaneous termination of pregnancy [4], and other non-cancerous hazards [29]. Studies on animal suggested possible links between tumor formation (liver and kidney) with THMs exposure [36]. Due to the carcinogenic nature of THMs, it becomes essential to analyze the probable risk on human health. Cancer risk indicates a probability to develop cancer during his/her lifetime because of THMs exposure via different exposure pathways. Looking into the carcinogenic nature of THMs, regulations and guidelines has been recommended by several agencies like the world health organization (WHO) and USEPA [55, 63] for their control in drinking water supplies however, no guideline exists for swimming pool water.

Over the years, several empirical and kinetics based predictive models [1, 44] has been developed to determine the concentration levels of THMs in drinking water supplies. However, limited information is available with respect to swimming pool water. Looking into this, there is a need to develop models which can most suitably predict the concentration levels of THMs in pool water owing to the recreational value [40, 57]. The present study is an attempt to develop predictive empirical models using multi-linear regression (MLR) approach to define the concentration level of THMs in swimming pool water. The issue of health risks associated with exposure of THMs from swimming pool water was also evaluated for non-competitive swimmers.

Materials and methods

Sampling protocol

Five indoor swimming pools in and around Dhanbad area (Jharkhand, India) were selected as sampling locations. The pool water mainly uses chlorine gas or bleaching powder as disinfecting agents to achieve disinfection of pool water. Triplicate samples of pool water were collected on daily basis for a period of three months to determine the concentration of THMs in pool water. Samples for THMs analysis were collected in 40-mL clean glass vials until full and tightly sealed with a screw cap. Prior to sampling, de-chlorinating agent (ascorbic acid) was added to vials to quench any available free residual chlorine, if any to cease further THMs formation. Samples were collected separately to analyze water quality parameters like pH, temperature, organic matter content etc. pH and temperature were measured on the sample site itself using multi-parameter water quality test meter. For detailed analysis of other parameters like residual chlorine, total organic carbon (TOC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), ultra violet absorbance at 254 nm (UV254), bromide ion concentration, and THMs, samples were brought to the wastewater Engineering laboratory at Indian Institute of Technology (Indian School of Mines) Dhanbad, Jharkhand, and stored at <4 °C till further analysis.

Analytical methods

Analysis of water quality parameters like pH and temperature were performed as mentioned above. Residual free chlorine content determination was carried in accordance with the Standard Methods, 4500-Cl G [3]. TOC analysis was conducted by high-temperature combustion-infrared method [3] using TOC analyzer (Model TOC-L/CSH/E200, Shimadzu) equipped with NDIR detector and Pt catalyst. DOC and UV254 examination was conducted after filtering the samples through 0.45 μm (Millipore) filter paper using TOC analyzer and UV-Visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), respectively.

To analyze the THMs content in pool water samples, liquid-liquid extraction using pentane as extracting solvent was done. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the samples was carried out using gas chromatograph, GC (Model: Chemito CERES800 Plus, Thermo Fischer) coupled with an auto-sampler and Ni63 electron capture detector (ECD). Chromatographic separation was performed on fused silica DB-5 column (30 m × 0.32 mm I.D. × 0.30 μm film thicknesses). THMs analysis was carried out as per USEPA method 551.1 [50]. Temperature programme for the separation of THMs is taken as per Kumari and Gupta [30] study. Nitrogen was used as a carrier gas (GC-grade).

Development and validation of model to predict THMs concentration in pool water

Pearson correlation matrix using the SPSS software (SPSS version 22.0) was used to determine the correlation between THMs and water quality parameters. MLR approach based on correlation and regression analysis was carried out to develop models to predict the THMs level in pool water. Data was divided into two sections: section 1 for model development (65%), and section 2 for model validation (35%). Under section 1, several mixtures of this data was tested by SPSS software for MLR to identify the most suitable model, and the remaining data set (section 2) was used to validate the model developed. Here, parameters like pH, temperature, residual chlorine, contact time, TOC, DOC, SUVA and UV254, were taken as independent variables and THMs as the dependent variable. The most appropriate predictive model was determined on the basis of observed R2 value (high the R2 value, the more significant the model is), and p value at 95% level of significance. A graph was plotted between the predicted and observed THMs values to specify the validity of model developed. The best fit line was achieved using the correlation coefficient values and slope of regression followed by statistical t-test analysis to determine model skewness.

Risk estimation

This study used the USEPA SWIMODEL to assess the risk exposure effects of THMs on human health during swimming [52]. SWIMODEL focuses on potential chemical intakes only, and provides an exposure estimate tailored to swimmers exposed to pool chemicals [53]. Risk assessment was conducted in 4 stepwise approach comprising of hazard identification, exposure assessment, dose-response assessment, and risk characterization.

Hazard identification was conducted by identifying the concentration level of THMs in swimming pool water as mentioned above. Exposure assessment involved risk evaluation for three different exposure pathways i.e. through accidental ingestion of pool water (oral ingestion), absorption through skin contact (dermal route) and inhalation. The concentration of THMs in air was estimated using Henry’s law [52]. To estimate the risk exposure of THMs in pool water, two different sensitive populations i.e. male and female was considered. Dose-response study was conducted by determining the average daily dose (ADD, mg kg-day−1) for the pathways mentioned above using Eq. (1–3).

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

where, ET is the swimming exposure time (hr event−1, 1.3); IR is the ingestion rate (L day−1, 0.25 L); Cw is the concentration of THMs (μg L−1); EF is the swimming exposure frequency (events yr−1, 120); ED is the exposure duration (yr, 30); BW is the body weight (Kg, male 60; female 55); AT is the average time (yrs, 30); SA is the skin surface area (m2, male 1.94; female 1.69); Kp is the permeability coefficient (cm hr.−1, compound specific); Cvp is the concentration of THMs in air estimated using Henry’s law [52], and IR’ is the inhalation rate (m3 hr.−1, 1.0). The values of input parameters like BW and SA shows wide variations due to country of origin, daily routines and lifestyle adopted. Hence, to simulate the Indian conditions, these values were taken from the recommended Indian Council of Medical Research [23] and WHO [64] guidelines. Rest of the input parameter values IR, IR’, EF, ED, ET, AT etc., were taken as per USEPA [52].

Risk estimation was conducted by multiplying the estimated ADD values to cancer slope factor (CSF, mg kg-day−1). The total cancer risk of THMs exposure was calculated by adding up the estimated individual risk for all the three exposure route as mentioned in Eq. (4).

| 4 |

The non-cancer risk of exposure of THMs for sensitive sub-population was calculated by estimating hazard quotient (HQ). HQ was calculated as a ratio of ADD value to reference dose (RfD, mg kg-day−1) value i.e. ADD/RfDTHMs. HQs were estimated for oral ingestion and dermal absorption exposure routes. CSF and RfD values of THMs was taken from USEPA [54] and IRIS [24]. If the HQ ratio is observed to be less than 1, the risk exposure is considered to be controlled at the given exposure scenario. If the observed HQ ratio is more than 1, significant concern exists on human health and certain risk-management actions have to be taken [32].

Uncertainty and sensitivity analysis

Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis was carried out on risk estimates to characterize risk of THMs exposure. To be precise, 10,000 random values of input parameters (BW, IR, SA, EF, ED, IR, concentration of the contaminant etc.) was generated using MS Excel random function. Statistical summary (maximum, minimum, average and percentiles values) were used to characterize the risk values [31].

Sensitivity analysis is usually performed to identify the most influential parameter affecting risk estimates. Sensitivity analysis of the risk estimated for different exposure pathways was carried out by arranging all the input parameters in columns and the estimated risk in rows of an MS excel worksheet (MS Excel 2010). This was followed by a graphical plot by means of spider chart or radar plot to determine the most predominant parameter influencing risk estimates.

Quality control and quality assurance

For this work, THMs calibration standards (analytical grade, AR; > 99.5% purity) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich, Germany. The GC temperature program was adjusted in accordance with retention time of the last analyzed peak. A non-polar organic solvent (Pentane) was run prior to the analysis of each batch of THMs samples to get a smooth baseline for further analysis. Mean recovery of THMs species for the method analyzed ranged from 86.9% to 102.3%. Field reagent blanks were analyzed to check for interferences in the samples. Relative percent difference (RPD) was calculated to identify the concentration level difference between two consecutive samples. Detection limit of the method was determined by replicate analysis of standard THMs solution at concentration level of 0.25 mg L−1. Good linearity with R2 values >0.989 was observed for all THMs species. Standard THMs calibration checks were performed after the analysis of every 20 sample. When the quantitative response between two analyzed samples differed by more than ±10%, the GC instrument was assumed to be out of calibration, and was subsequently recalibrated for further analysis.

Result and discussion

Water quality analysis of pool water

The average water quality data of five sampling locations is presented in Table 1. The study revealed that the pool water is slightly alkaline in nature and pH value ranged from 7.2 to 7.6. Temperature ranged from 31 °C to 33.4 °C. Both these values fall under the prescribed WHO guideline limits [62], and are similar to those reported in other research investigations [34, 39, 45]. Residual chlorine content of the samples varied from 0.0703 to 0.1418 Cl2 mL−1, which appeared to be quite low to achieve proper disinfection of swimming pool water. NOM substances like TOC and absorbance at UV254 are chief precursors for the formation of THMs in pool water [7]. These are vital and interrelated factors which determine the level of organic materials, particularly those with aromatic rings. The results revealed that TOC content showed wide variation with values ranging from 4.3 mg L−1 to 34.21 mg L−1. At swimming pool, an increase in TOC level does not happens suddenly but a considerable increase occurs over a time interval, and it is presumed that organic contaminants added to the pool water by bathers reacts with chlorinated compounds to form DBPs. It is also important to determine the level of nitrate in pool water as nitrogenous compounds constitute a part of the organic matter released from swimmers. These substances in reaction with chlorine forms by-products during the process of disinfection. Ammonia component of urine and sweat of swimmers are the possible source of nitrogen contamination particularly in the form of nitrates [8, 48]. The average concentration of nitrates found in tested pools was from 4.8 mg L−1 to 7.6 mg L−1. DOC constituted 86–95% of total organic fraction and demonstrated the dominance of heterogeneous mixture of humic substances. Substances of swimmers’ origin such as hair, sunscreen lotion, saliva and urine are the possible source and adds to the DOC content [10]. Increased levels of UV254 and SUVA in the samples indicated the presence of highly hydrophobic and aromatic contents of NOM in pool water [17].

Table 1.

Water quality status of swimming pool water (N = 900)

| Parameters | Range | Mean | [62]* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature, °C | 31–33.4 | 31.61 ± 0.70 | 26–30 |

| pH | 7.2–7.6 | 7.50 ± 0.13 | 7.2–7.8 |

| Residual Chlorine, Cl2 mL−1 | 0.070–0.283 | 0.157 ± 0.083 | < 1.2 |

| Bromide ion (Br−), mg L−1 | BDL | – | – |

| Nitrate, mg NO3 L−1 | 4.8–7.6 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | – |

| TOC, mg L−1 | 4.3–34.21 | 18.95 ± 9.42 | – |

| DOC, mg L−1 | 3.7–32.54 | 18.23 ± 8.06 | – |

| UV254, cm−1 | 0.178–0.789 | 0.27 ± 0.10 | – |

| SUVA, L mg-m−1 | 2.42–4.91 | 3.49 ± 0.19 | – |

| Chloroform, μg L−1 | 159–217 | 191 ± 1.45 | – |

| DBCM, μg L−1 | 2.0–4.0 | 2.93 ± 0.85 | – |

| BDCM, μg L−1 | 2.0–5.0 | 3.25 ± 0.93 | – |

| THMs, μg L−1 | 163–226 | 197.18 ± 16.31 | 100 |

*Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments. Volume 2: Swimming Pools and Similar Environments

Concentration of THMs ranged in pool water samples varied from 163 μg L−1 to 226 μg L−1 with an average value of 197.18 μg L−1. High level of observed THMs may be attributed to the presence of high level of NOM content in pool water [37]. A comparative study revealed that observed THMs levels were higher than those reported in countries like Korea [34], Italy [2], UK [15], Canada [45], Germany [33] and Spain [9]. As mentioned above, Henry’s law was used to estimate the concentration of THMs in air. Maximum concentration of THMs species in air was found to be 3.25E-02 μg m3–1 for chloroform, 1.28E-04 μg m3–1 for DBCM, and 3.33E-04 μg m3–1 for BDCM, respectively. As observed, chloroform was the most dominant THMs species, and contributed up to 99% to TTHMs in pool water. Bromoform was not detected in any of the analyzed samples which is probably due to the below detectable concentration of bromide ion. The study observed that chloro-THMs dominated bromo-THMs. The dominance of chloro-THMs can be linked to repeated chlorination in closed water systems where the treated water is virtually re-circulated and repeatedly disinfected which leads to an increase in the proportion of THMs species, and results in chloroform enrichment in comparison to other THMs [35, 47]. The observed THMs sequence was: chloroform > BDCM > DBCM > bromoform, similar to those reported in other research investigations [5, 19, 26, 45].

Correlation of THMs with water quality parameters

Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) with two tailed level of significance (p) was used to determine the relationship of water quality parameters with THMs formation using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS, version 21.0) as mentioned above. The correlation matrix is represented by Table 2. Statistical analysis revealed that out of all the parameters analyzed, pH showed the strongest correlation (r = 0.872) with THMs for pool water samples. OH− ion hydrolysis of large carbon chain organic molecules at high pH results in increased THMs formation [20, 49]. Temperature was observed to be the second most important parameter (r = 0.854) of THMs formation. Temperature supplies the required bond energy for reaction between NOM and chlorine compounds. Richardson et al. [43] reported high temperature of pool water which accelerates the rate of THMs formation due to rapid chlorine decay. Other parameters like TOC showed moderate and positive correlation (r = 0.585) with THMs formation since high organic matter content results in increased THMs formation during disinfection. UV254 showed a positive but low correlation (0.492) with THMs. This low correlation can be an indicative of the presence of functional moieties like benzene rings, phenolic-OH groups, conjugated double bonds and hydrophobic groups in NOM content which showed maximum absorption at a wavelength of 254 nm [21]. Residual chlorine content showed negative correlation (r = −0.796) with THMs formation. Low residual chlorine in the pool water needs more chlorine to oxidize the NOM which subsequently results in high concentration of THMs.

Table 2.

Pearson correlation matrix to identify the relationship between water quality parameters with THMs

| pH | Temp | TOC | SUVA | UV254 | Residual Cl2 | Chloroform | THMs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 1 | 0.272 | −0.240 | 0.503* | 0.517* | 0.035 | 0.869 | 0.872 |

| Temp | 1 | −0.396 | 0.175 | 0.020 | −0.090 | 0.851 | 0.854 | |

| TOC | 1 | −0.442 | −0.017 | −0.171 | 0.576 | 0.585* | ||

| SUVA | 1 | 0.872** | −0.094 | 0.287 | 0.299 | |||

| UV254 | 1 | −0.143 | 0.491 | 0.492 | ||||

| Residual Cl2 | 1 | −0.798 | −0.796** | |||||

| Chloroform | 1 | 0.932 | ||||||

| THMs | 1 |

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Development of THMs model

Multi-linear and non-linear regression approach has been used to develop empirical models to predict the concentration of THMs in pool water. The most appropriate predictive linear and non-linear models to determine THMs concentration is represented by Eq. (5–6) as mentioned below:

Linear model:

| 5 |

Non-linear model:

| 6 |

where, TOC is the total organic carbon (mg L−1); SUVA is the specific ultra violet absorbance (L mg-m−1); UV254 is the ultra violet absorbance (cm−1); Residual chlorine (Cl2 mL−1) and a, b, c, d, e, f and g are the observed values of statistical coefficients.

Statistical analysis of developed predictive models (linear and non-linear) is presented in Table 3. The study observed that combination of independent variables (pH + temperature + TOC + SUVA +UV254 + residual Cl2) was found to be more statistically significant compared to other analysed combinations. R2 values, standard error of estimate and Durbin-Watson estimate for the proposed linear model was statistically more significant than non-linear model. High coefficient correlation (r = 0.985) and R2 (0.969) was observed for linear model. The value of Durbin-Watson estimate was found to be 1.720 which was within the range (1.5–2.5), and significant as well [56]. Therefore, on the basis of statistical tests conducted it can be said that linear model is most suitable and appropriate to predict the level of THMs in swimming pool water.

Table 3.

Summary of developed THMs model

| Model Parameters | Linear | Non Linear |

|---|---|---|

| Coefficient of correlation (r) | 0.985 | 0.723 |

| R2 | 0.969 | 0.522 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.951 | 0.236 |

| Standard error of the estimate | 0.023 | 0.510 |

| Durbin-Watson | 1.720 | 1.412 |

| Statistical Coefficients | ||

| a | 2.023 | −8.946 |

| b | −1.710 | −0.016 |

| c | −0.006 | 2.816 |

| d | 0.016 | 0.067 |

| e | −0.057 | −0.729 |

| f | 1.441 | 0.693 |

| g | −1.098 | −0.171 |

Model validation

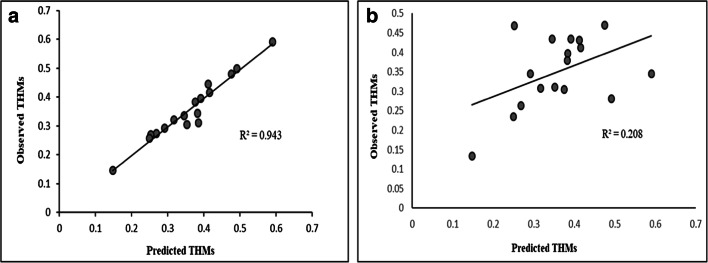

To check the applicability of the model for field conditions, model should be validated to see whether the experimental data fits well with the field data or not. For linear model, high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.943) was obtained for observed and predicted THMs values which indicated the efficacy of the model developed. Statistical t- test was carried out to determine the skewness of model developed. For linear model, low tcal value and the high p value (> 0.05) indicated the statistical significance of the model. However, for non-linear model, high tcal and low p value (< 0.05) was obtained. This indicated that model bias is insignificant for linear model as tcal value was lower than tcritcal value (Table 4). Other statistical parameters like mean square error of prediction (MSEP) and percentage error were also low for linear model compared to non-linear model. Previous research investigations are showed the applicability of linear model over non-linear models to predict the THMs levels in drinking water supplies [1, 30, 56]. Thus, the overall observation and validation indicated that MLR approach can prove to useful for swimming pool management to pre-assess the concentration level of THMs in pool water, and also to implement control practices for their regulation. (Fig. 1).

Table 4.

Validation statistics of model developed

| THMs Model | ||

|---|---|---|

| Validation Statistics | Linear | Non- linear |

| Degree of freedom, df | 17 | 17 |

| Std. Deviation of prediction errors | 0.106 | 87.81 |

| Std. Error of estimated mean bias | 0.025 | 21.29 |

| Mean square error of prediction (MSEP) | 0.011 | 7710.59 |

| Error of prediction (%) | 1 | 61.11 |

| tcal (Calculated) | 0.423 | 9.933 |

| tcri (Critical) | 2.119 | 2.119 |

| Significant | No | Yes |

Fig. 1.

Correlation between observed and predicted THMs (a) Linear model (b) Non-linear model

Cancer risk evaluation and simulation

Risk assessment analysis was carried out for three different possible exposure pathways as mentioned above. As stated earlier that chloroform is the predominant THMs and constituted up to 99% to total THMs (TTHMs) in pool water thus, risk was estimated only for chloroform. Chen et al. [12] also reported chloroform as the most prevalent THM compound in the swimming pool water. The estimated average cancer risk through all the three exposure routes is presented in Table 5. Average cancer risk through the accidental ingestion of pool water was found to be 9.81E-08 for female and 9.41E-08 for male, respectively, and was very low and insignificant as per the USEPA cancer risk classification [51]. The risk values less than 10−6 is considered to be acceptable, and possess no possible risk on human health. Similarly, risk evaluated through skin contact (dermal route) was also well below the prescribed limit (10−6) for both the studied population as presented in Table 5. Hence, both these exposure pathway does not possess any risk to human health. The study observed that inhalation exposure was the most relevant and significant exposure pathway and the estimated risk values falls within the ‘very high’ category (male: 7.49E-03; female: 13.71E-03) as per the USEPA cancer risk assessment classification scheme [51]. Inhalation exposure risk values were approximately three times higher than the acceptable risk level (10−6) thus indicating significant risk and possible concerns on human health. Previous studies also reported inhalation to be the major route of exposure [18, 34]. Few studies, though, suggest dermal exposure to be the most significant pathway [13]. The variation mainly occurs due to use of permeability coefficient in various risk assessment studies. Risk exposure followed the sequence of inhalation > skin contact (dermal) > accidental ingestion. Female showed 1.43 times high risk values compared to male demonstrating that female is the most sensitive sub-population. This dissimilarity can be attributed to difference in input parameters like BW and SA used in risk assessment process.

Table 5.

Comparison of estimated and simulated risk values

| Exposure Pathways | Estimated risk | Simulated risk | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Oral ingestion | 9.41 E-08 | 9.81 E-08 | 9.33 E-08 | 9.95 E-08 |

| Dermal absorption | 4.82 E-07 | 5.16 E-07 | 5.23 E-07 | 5.82 E-07 |

| Inhalation | 7.49 E-03 | 13.71 E-03 | 8.22 E-03 | 14.60 E-03 |

Total risk analysis revealed that swimmers have higher chance of risk through inhalation exposure and contributed up to 99% to the total cancer risk. Research investigations reported inhalation and dermal exposure as the major routes of THMs risk in swimming pools while involvement of accidental ingestion may be negligible [12, 18, 34, 66].

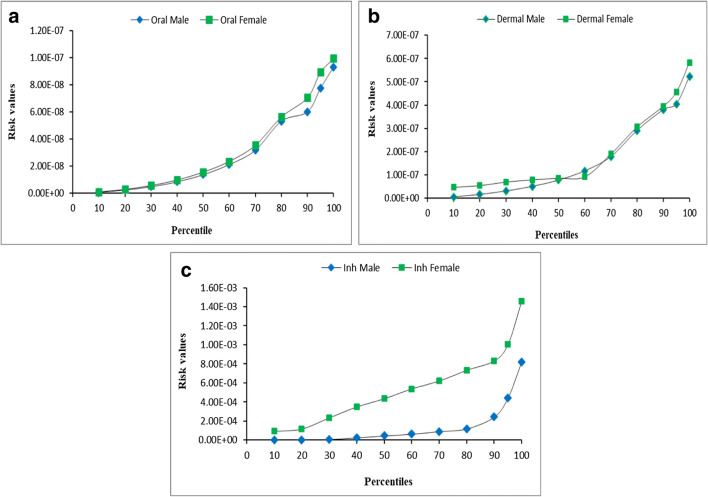

To identify variability in risk estimates, Monte Carlo simulation was conducted in which a total of 10,000 iterations was performed, and the average, 10th percentile to 95th percentile, and maximum risk values were determined for both the sub-populations. The obtained data was compared with the experimental data and the graphical representation is presented in Fig. 2. The results revealed that average risk estimated using SWIMODEL for the three exposure pathways fall within ±2.4% of the simulated average risk values obtained through Monte Carlo simulations. This indicated that risk estimated by USEPA model is appropriate and can be used to assess risk exposure of THMs on human health.

Fig. 2.

Monte Carlo simulations of estimated risk for the three exposure pathways

Non-cancer risk estimation

HQ was calculated to determine the non-cancer risk exposure of THMs in the studied sub-population. HQ values for both accidental ingestion (oral) and skin contact (dermal) exposure routes is given in Table 6. HQ values of oral and dermal routes were observed to be less than the USEPA prescribed risk level (HQ < 1), and thus do not possess any significant effects on human health. If the HQ value exceeds 1, possible concern exists on to human health. Therefore, the non-cancer effects of THMs exposure would be skeptical to cause diseases like jaundice, neuro-behavioral effects, subjective central nervous system effect and enlarged livers [58].

Table 6.

HQ for oral and dermal routes in male and female

| Oral | Dermal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Average | 1.54E-03 | 1.60E-03 | 7.89E-03 | 8.45E-03 |

| Minimum | 1.32E-03 | 1.38E-03 | 6.79E-03 | 7.27E-03 |

| Maximum | 1.81E-03 | 1.88E-03 | 9.27E-03 | 9.93E-03 |

Sensitivity analysis

In this study, spider chart or radar plot analysis was carried out to determine the most sensitive parameter of risk estimation. Sensitivity plot depicts the degree of dominancy of factors influencing risk. The plot analysis revealed that chloroform concentration is the chief parameter governing risk estimates (Fig. 3). The possible risk exposure can be minimized by regulating the concentration of THMs specially chloroform in the pool water, and monitoring the level of NOM, the major THMs precursor. EF appeared to be second most dominant factor followed by BW, ED, inhalation rate, IR, SA and ET. The trend observed was found to be similar for both the sub-population studied.

Fig. 3.

Spider chart for sensitivity analysis

Uncertainty in risk analysis

In human health risk evaluation, uncertainty analysis serves as an important tool to determine the variation in input parameters. Uncertainties may arise due to variation in input parameters used to assess the risk. Monte Carlo simulation was used to reduce uncertainty in risk estimation, however some of them may still exist. Risk analysis was carried out as per the recommended USEPA guidelines considering the average and maximum concentration levels for the normal and worst case scenarios. The risk was estimated only for chloroform as it was the predominant THMs species. But in life real situations, in addition to THMs, the pool water may also contain other harmful by-products for example chloramines, chloro-phenols, bromate, haloacetic acids, haloketones etc., which would add to the risk analyzed [65]. Regular monitoring and analysis of other by-products is required to achieve accuracy in risk estimation. The risk estimates described in this study represents only the probability of developing cancer but the actual cancer risk may be higher if the effect of all other unrecognized and unanalyzed DBPs are taken into account.

Conclusions

The study focused on development of predictive models to determine the concentration of THMs and assess their potential risk exposure for pool water samples. The pool water exhibited high concentration of THMs (average: 197.18 μg L−1) which is somehow related with high levels of NOM content (max: 34.21 mg L−1). MLR approach indicated that linear model is the most suitable to predict the level of THMs in swimming pool water with high correlation coefficients and high R2 values compared to non-linear model. Amongst the three different exposure pathways, inhalation leads to the maximum cancer risk and was found to be the most dominant while risk due to other two pathways was found to be insignificant. Radar plot analysis revealed that chloroform concentration is the most sensitive parameter governing risk estimates followed by EF and ED. Proper disinfection practices and control measures should be adopted to reduce the concentration of THMs in pool water leading to risk estimates. Inhalation exposure risk estimated using different mass transfer models may over or under-estimate the health risk thus, direct calculation of risk estimates from THMs concentration in air is required. In addition to this, bacteriological analysis of pool water needs to be carried out to determine the degree of contamination and to assess the pool water quality.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology (Indian School of Mines) Dhanbad, India, for providing research facilities and all necessary support required for this study.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there exists no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Abdullah A, Hussona SE. Predictive model for disinfection by-product in Alexandria drinking water, northern west of Egypt. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2013;20(10):7152–7166. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-1501-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggazzotti G, Fantuzzi G, Righi E, Predieri G. Environmental and biological monitoring of chloroform in indoor swimming pools. J Chromatogr A. 1995;710:181–190. doi: 10.1016/0021-9673(95)00432-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.APHA (American Public Health Association) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewaters. 22. Washington, DC: APHA, AWWA, WEF; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aschengrau A, Zierler S, Cohen A. Quality of community drinking water and the occurrence of late adverse pregnancy outcomes. Arch Environ Health. 1993;48(2):105–113. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1993.9938403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bessonneau V, Derbez M, Clement M, Thomas O. Determinants of chlorination by-products in indoor swimming pools. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2011;215(1):76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Black VC. White's handbook of chlorination and alternative disinfectants. Hoboken: Wiley; 2010. pp. 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bond T, Goslan EH, Parsons SA, Jefferson B. A critical review of trihalomethane and haloacetic acid formation from natural organic matter surrogates. Environ Technol Rev. 2012;1(1):93–113. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2012.705895. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bradford WL. What bathers put into a pool: a critical review of body fluids and a body fluid analog. Int J Aquatic Res Educ. 2014;8(2):168–181. doi: 10.1123/ijare.2013-0028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caro J, Gallego M. Assessment of exposure of workers and swimmers to trihalomethanes in an indoor swimming pool. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:4793–4798. doi: 10.1021/es070084c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carter RAA, Joll CA. Occurrence and formation of disinfection by-products in the swimming pool environment: a critical review. J Environ Sci. 2017;58:19–50. doi: 10.1016/J.JES.2017.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheema WA, Kaarsholm KMS, Andersen HR. Combined UV treatment and ozonation for the removal of by-product precursors in swimming pool water. Water Res. 2017;110:141–149. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen M-J, Lin C-H, Duh J-M, Chou W-S, Hsu H-T. Development of multi-pathway probalistic health risk assessment model for swimmers exposed to chloroform in indoor swimming pools. J Hazard Mater. 2011;185:1037–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chowdhury S. Predicting human exposure and risk from chlorinated indoor swimming pool: a case study. Environ Monit Assess. 2015;187(8):502. doi: 10.1007/s10661-015-4719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chowdhury S, Alhooshani K, Karanfil T. Disinfection byproducts in swimming pool: occurrences, implications and future needs. Water Res. 2014;53(0):68–109. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chu H, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ. Distribution and determinants of trihalomethane concentrations in indoor swimming pools. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:243–247. doi: 10.1136/oem.59.4.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Costet N, Villanueva CM, Jaakkola JJ, Kogevinas M, Cantor KP, King WD, Lynch CF, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Cordier S. Water disinfection by-products and bladder cancer: is there a European specificity? A pooled and meta-analysis of European case-control studies. Occup Environ Med. 2011;68(5):379–385. doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.062703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edzwald JK, Tobiason JE. Enhanced coagulation: US requirements and a broader view. Water Sci Technol. 1999;40(9):63–70. doi: 10.2166/wst.1999.0444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florentin A, Hautemanière A, Hartemann P. Health effects of disinfection by-products in chlorinated swimming pools. Int J Hyg Enviorn Health. 2011;214:461–469. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Font-Ribera L, Esplugues A, Ballester F, Martınez-Arguelles B, et al. Trihalometanos en el agua de piscinas en cuatro zonas de Espan˜a participantes en el proyecto INMA. Gac Sanit. 2010;24(6):483–486. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Villanova RJ, Garcia C, Gomez JA, Garcia MP, Ardanuy R. Formation, evolution and modeling of trihalomethanes in the drinking water of a town: I. At the municipal treatment utilities. Water Res. 1997;31:1299–1308. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(96)00335-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hang C, Zhang B, Gong T, Xian Q. Occurrence and health risk assessment of halogenated disinfection byproducts in indoor swimming pool water. Sci Total Environ. 2016;543:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ilyas H, Masih I, van der Hoek J. Disinfection methods for swimming pool water: byproduct formation and control. Water. 2018;10:797. doi: 10.3390/w10060797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Indian Council of Medical Research. Nutrient requirements and recommended dietary allowances for Indians. A Report of the Expert Group of the Indian Council of Medical Research, Chapter-3. 2009. pp. 24.

- 24.IRIS. Integrated Risk Information system. 2017. http://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris/search/index.cfm?first_letter=C. Accessed 31 Aug 2019.

- 25.Judd SJ, Black SH. Disinfection by-product formation in swimming pool waters: a simple mass balance. Water Res. 2000;34:1611–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0043-1354(99)00316-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Judd SJ, Jeffrey JA. Trihalomethane formation during swimming pool water disinfection using hypobromous and hypochlorous acids. Water Res. 1995;29:1203–1206. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(94)00230-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khallef M, Liman R, Konuk M, Cigerci IH, Benouareth D, Tabet M, Abda A. Genotoxicity of drinking water disinfection by-products (bromoform and chloroform) by using both allium anaphase-telophase and comet tests. Cytotechnology. 2015;67:207–213. doi: 10.1007/s10616-013-9675-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.King WD, Marrett LD, Woolcott CG. Case-control study of colon and rectal cancers and chlorination by/products in treated water. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2000;9:813–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klotz JB, Pyrch LA. Neural tube defects and drinking water disinfection by-products. Epidemiology. 1999;10(4):383–390. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199907000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumari M, Gupta SK. Modelling of trihalomethanes in drinking water supplies-a case study of eastern region of India. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22:12615–12623. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4553-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kumari M, Kumar A. Human health risk assessment of antibiotics in binary mixtures for finished drinking water. Chemosphere. 2020;240:124864. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.124864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumari M, Gupta SK, Mishra BK. Multi-exposure cancer and non-cancer risk assessment of trihalomethanes in drinking water supplies – a case study of eastern region of India. Ecotox Environ Safe. 2015;113:433–438. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lahl U, Batjer K, Duszeln JV, Gabel B, Stachel B, Thiemann W. Distribution and balance of volatile halogenated hydrocarbons in the water and air of covered swimming pools using chlorine for water disinfection. Water Res. 1981;15(7):803–814. doi: 10.1016/0043-1354(81)90133-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee J, Ha K-T, Zoh K-D. Characteristics of trihalomethanes (THMS) production and associated health risk assessment in swimming pool waters treated with different disinfection methods. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:1990–1997. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lourencetti C, Grimalt JO, Marco E, Fernandez P, Font-Ribera L, Villanueva CM, Kogevinas M. Trihalomethanes in chlorine and bromine disinfected swimming pools: air-water distributions and human exposure. Environ Int. 2012;45:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manasfi T, Coulomb B, Boudenne J-L. Occurrence, origin, and toxicity of disinfection byproducts in chlorinated swimming pools: an overview. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2017;220(3):591–603. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matilainen A, Vepsalainen M, Sillanpaa M. Natural organic matter removal by coagulation during drinking water treatment: a review. Adv Colloid Interf Sci. 2010;159:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cis.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pandics T, Hofer Á, Dura G, Vargha M, Szigeti T, Tóth E. Health risk of swimming pool disinfection by-products: a regulatory perspective. J Water Health. 2018;16(6):947–957. doi: 10.2166/wh.2018.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Panyakapo M, Soontornchai S, Paopuree P. Cancer risk assessment from exposure to trihalomethanes in tap water and swimming pool water. J Environ Sci (China) 2008;20:372–378. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)60058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peng D, Saravia F, Abbt-Braun G, Horn H. Occurrence and simulation of trihalomethanes in swimming pool water: a simple prediction method based on DOC and mass balance. Water Res. 2016;88:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2015.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powick PEJ. Swimming pools-brief outline of water treatment and management. Water Sci Technol. 1989;21(2):151–160. doi: 10.2166/wst.1989.0043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reif JS, Hatch MC, Bracken M, Holmes LB, Schwetz BA, Singer PC. Reproductive and developmental effects of disinfection by-products in drinking water. Environ Health Perspect. 1996;104(10):1056–1061. doi: 10.1289/ehp.961041056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Richardson SD, DeMarini DM, Kogevinas M. What's in the pool? A comprehensive identification of disinfection byproducts and assessment of mutagenicity of chlorinated and brominated swimming pool water. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:1523–1530. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1001965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sadiq R, Rodriguez MJ. Disinfection by-products (DBPs) in drinking water and predictive models for their occurrence: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2004;321(1–3):21–46. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2003.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simard S, Tardif R, Rodriguez MJ. Variability of chlorination by-product occurrence in water of indoor and outdoor swimming pools. Water Res. 2013;47:1763–1772. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stayner LT, Pedersen M, Patelarou E, Decordier I, Vande LK, Chatzi L, Espinosa A, Fthenou E, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Gracia-Lavedan E, Stephanou EG, Kirsch-Volders M, Kogevinas M. Exposure to brominated trihalomethanes in water during pregnancy and micronuclei frequency in maternal and cord blood lymphocytes. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122:100–106. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tardif R, Rodriguez M, Catto C, Charest-Tardif G, Simard S. Concentrations of disinfection by products in swimming pool following modifications of the water treatment process: an exploratory study. J Environ Sci. 2017;58:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Teo TLL, Coleman HM, Khan SJ. Chemical contaminants in swimming pools: occurrence, implications and control. Environ Int. 2015;76:16–31. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.11.012/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thacker NP, Nitnaware V. Factors influencing formation of trihalomethanes in swimming pool water. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2003;71:633–640. doi: 10.1007/s00128-003-8650-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.USEPA (1995) United States Environmental Protection Agency Method 551. Determination of chlorinated disinfection by-products and chlorinated solvents in drinking water by Liquid–liquid Extraction and Gas Chromatography with Electron-capture Detection. Environmental Monitoring Systems Laboratory, Office of Research and Development, Cincinnati, Ohio.

- 51.USEPA (1999) United States Environmental Protection Agency A risk assessment–multiway exposure spreadsheet calculation tool. Washington, DC.

- 52.USEPA (2003) United States Environmental Protection Agency, User's manual swimmer exposure assessment model (SWIMODEL) Version 3.0. U.S. EPA Office of Pesticide Programs Antimicrobials Division.

- 53.USEPA (2005) United States Environmental Protection Agency Guidelines for carcinogen risk assessment, risk assessment forum, Washington, DC; EPA/630/P/03/001F.

- 54.USEPA (2009) United States Environmental Protection Agency, National Primary Drinking Water Regulations. United States Environmental Protection Agency (Accessed: 31 June 2019) EPA816-F-09-004. http://water.epa.gov/drink/contaminants/upload/mcl-2.pdf.

- 55.USEPA . United States Environmental Protection Agency, Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories. Washington, DC: Office of Water U.S. EPA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uyak V, Ozdemir K, Toroz I. Multiple linear regression modeling of disinfection by-products formation in Istanbul drinking water reservoirs. Sci Total Environ. 2007;378:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Veldhoven KV, Keski-Rahkonen P, Barupal DK, Villanueva CM, Font-Ribera L, et al. Effects of exposure to water disinfection by-products in a swimming pool: a metabolome-wide association study. Environ Int. 2018;111:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viana RB, Cavalcante RM, Braga FMG. Risk assessment of trihalomethanes from tap water in Fortaleza Brazil. Environ Monit Assess. 2009;151(1–4):317–325. doi: 10.1007/s10661-008-0273-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Villanueva CM, Font-Ribera L. Health impact of disinfection by-products in swimming pools. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 2012;48:387–396. doi: 10.4415/ANN_12_04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Villanueva CM, Cordier S, Font-Ribera L, Salas LA, Levallois P. Overview of disinfection by-products and associated health effects. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015;2:107–115. doi: 10.1007/s40572-014-0032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang S, Zheng W, Liu X, Xue P, Jiang S, Lu D, Zhang Q, He G, Pi J, Andersen ME, Tan H, Qu W. Iodoacetic acid activates Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response in vitro and in vivo. Environ Sci Technol. 2014;48:13478–13488. doi: 10.1021/es502855x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.WHO. Guidelines for safe recreational water environments. Volume 2: swimming pools and similar environments. Chapter 4. Geneva: WHO; 2006.

- 63.WHO. World Health Organization, guidelines for drinking-water quality, 4th edn. Geneva: WHO; 2011. pp 427–30.

- 64.WHO. World Health Organization, World health statistics. 2013. http://www.who.int/gho/publications/world_health_statistics/EN_WHS2013_Full.pdf. Accessed 15 Aug 2019.

- 65.Wyczarska-Kokot J. The problem of chloramines in swimming pool water technological research experience. Desalin Water Treat. 2018;134:7–14. doi: 10.5004/dwt.2018.22455. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zwiener C, Richardson SD, De Marini DM, Grummt T, Glauner T, Frimmel FH. Drowning in disinfection byproducts? Assessing swimming pool water. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:363–337. doi: 10.1021/es062367v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]