Abstract

We describe an emergency department (ED)-based, Latino patient focused, unblinded, randomized controlled trial to empirically test if automated bilingual computerized alcohol screening and brief intervention (AB-CASI), a digital health tool, is superior to standard care (SC) on measures of alcohol consumption, alcohol-related negative behaviors and consequences, and 30-day treatment engagement. The trial design addresses the full spectrum of unhealthy drinking from high-risk drinking to severe alcohol use disorder (AUD). In an effort to surmount known ED-based alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment process barriers, while addressing racial/ethnic alcohol-related health disparities among Latino groups, this trial will purposively use a digital health tool and seek enrollment of English and/or Spanish speaking self-identified adult Latino ED patients. Participants will be randomized (1:1) to AB-CASI or SC, stratified by AUD severity and preferred language (English vs. Spanish). The primary outcome will be the number of binge drinking days assessed using the 28-day timeline followback method at 12 months post-randomization. Secondary outcomes will include mean number of drinks/week and number of episodes of driving impaired, riding with an impaired driver, injuries, arrests, and tardiness and days absent from work/school. A sample size of 820 is necessary to provide 80% power to detect a 1.14 difference between AB-CASI and SC in the primary outcome. Showing efficacy of this promising bilingual ED-based brief intervention tool in Latino patients has the potential to widely and efficiently expand prevention efforts and facilitate meaningful contact with specialized treatment services.

Keywords: Alcohol screening, Behavioral intervention, Emergency department, Digital health, Health disparities, Latino

1. Introduction

1.1. U.S. Latinos and alcohol-related disease burden

Disparities in drinking-consequences carry heavy disease burden for U.S. Latinos. This is expected to worsen as the Latino population doubles by 2060 becoming nearly 1/3rd of the U.S. population [1–3]. Studies document greater burden of disease from both social and health perspectives (e.g., impaired driving/crashes; cirrhosis morbidity/mortality) among Latino drinkers [4–10]. The first national alcohol survey to emphasize race/ethnicity was conducted in 1984 [11]. Subsequent studies show complexity and importance of racial/ethnic variations in drinking and consequences [12–15]. Latino men have high prevalence of daily heavy drinking (more likely to binge drink) [6,16–21]. Moreover, while Non-Latino Whites are more likely to become dependent, once alcohol dependent, Latinos have higher prevalence of recurrent/persistent dependence [7,17,22,23]. Latinos also face higher rates of negative consequences (e.g., impaired driving, impaired driving-related arrests) [24,25]. While research on distinctions between/within Latino population subgroups and AUD prevalence has increased, it remains very limited.

1.2. U.S. emergency departments and alcohol use disorders

National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey data show that alcohol remains a major contributor to ED visits [26]. In 2017, U.S. EDs had more than 138 million visits (43.3/100 persons; over 22 million visits by Latinos); nearly 40 million injury-related. For the chronic alcohol-related condition category, there were over 4.2 million alcohol-misuse/abuse/dependence visits. Between 2006 and 2014, U.S. ED alcohol-related visits increased by over 61% [27]. Acute and chronic alcohol-related visits also increased by over 51% and 75% respectively. Another study showed that hours spent in care for alcohol-related ED visits nearly doubled from 5.6 million (2001) to 11.6 million (2011), a 108.5% increase while overall ED hours only increased 54.0% with corresponding 232.2% increase in ED resource utilization (e.g., lab tests, CTs/MRIs) [28]. A more recent study revealed that between 1999 and 2017, among those ≥16 y/o, annual alcohol-related deaths doubled (35,914 to 72,558) and alcohol-related death rate increased by 50% [29].

1.3. EDs offer opportunity to address alcohol-related disparities

ED visits coupled with alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (SBIRT), provide unique opportunity to intervene and address alcohol-related health disparities, particularly among vulnerable populations [30]. Nearly 20 years ago, ED-SBIRT was conceptualized. Since then, it has been rigorously tested in cohort and large RCTs [31–33]. Moreover, for approximately 15 years, the American College of Surgeons mandated SBIRT use in verified trauma centers [34]. However, past research identifies barriers (e.g., time burden, language, intervention fidelity) to consistently applying ED-SBIRT [35–37]. Use of automated bilingual (English and Spanish) computerized alcohol screening and intervention (AB-CASI) has shown it to be compelling in reducing time and resource burden while providing patient anonymity/confidentiality in self-disclosure of sensitive [38,39]. AB-CASI’s automated-bilingual-scripted intervention facilitates intervention consistency. So, it can bolster intervention fidelity and integrity by reducing individual variability found when care providers use face-to-face brief interventions. This is particularly important as variations exists in accuracy and reliability of measures across different racial/ethnic groups with tailored intervention feed-back [40–43]. We describe the construction of our AB-CASI clinical trial, highlighting design decisions and considerations.

2. Methods

With a health disparity focus, this randomized controlled trial will accomplish three aims: 1) To compare the efficacy of AB-CASI to Standard Care (SC) in the reduction of alcohol consumption in unhealthy (i.e., high-risk) drinkers [44]; 2) To compare the efficacy of AB-CASI to SC in the reduction of alcohol-related negative health behaviors and consequences; 3) To compare the efficacy of AB-CASI to SC in 30-day treatment engagement. Further, given the paucity of ED-based alcohol SBIRT research conducted in Latino subgroups, the trial will explore variation of AB-CASI on alcohol consumption, alcohol-related negative health behaviors and consequences, and 30-day treatment engagement across Latino subpopulations (Puerto-Rican, Mexican-American, Cuban-American, South/Central American) as well as other potential modifiers (age, birthplace, gender, preferred language, dependence, reason for ED visit, and smoking status). Participants will be consented and enrolled in English or Spanish according to their language preference.

At the time of development of this trial, the DSM-IV was widely in use. From the outset, this investigation encompassed the inclusion of the whole spectrum of unhealthy drinking which at that time, definitionally, included those drinking above the low-risk limits (i.e., women and all those older than 65 y/o who have > 3 drinks/occasion or > 7 drinks/week; men who have > 4 drinks/occasion or > 14 drinks/week) through dependence [44]. In May of 2013, the DSM-5 was released and what was previously categorized in the DSM-IV as two different alcohol disorders (i.e., alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence) became one disorder (i.e., AUD) with three levels of severity; mild, moderate, and severe. Currently, the NIAAA points to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans to reference high-risk drinking (i.e., for women ≥4 drinks on any day or ≥ 8 drinks per week; for men ≥5 drinks on any day or ≥ 15 drinks per week; binge drinking - drinking ≥4 drinks for women and ≥ 5 drinks for men within about 2 h) [45,46]. Here forward, we use the most current alcohol disorder nomenclature to minimize confusion.

Data are being collected using electronic case report forms in the Oncore Clinical Trials Management System (Forte Research, Madison, WI). The protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by Human Research Protection Program and Institutional Review Board at Yale University and the trial was registered with Clinicaltrials.gov with identifier NCT02247388.

2.1. Design

This study is an unblinded, parallel group RCT designed to evaluate the efficacy of AB-CASI in reducing alcohol use when compared to SC among adult Latino ED drinkers. Table 1 lists key RCT planning design decision and respective rationale.

Table 1.

Design decisions and rationale.

| Decision | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Enrollment of self-identified Latino ED patients | Address alcohol-related health disparities in a highly vulnerable group in a ED-SBIRT context |

| Bilingual (English and Spanish) ED-SBIRT | Address known major language barrier limitation in ED-SBIRT |

| Prescreen [Health Screen] | Ensure enrollment of consistent above low-risk limit drinkers |

| 5 baseline assessments | Capture alcohol use quantity and frequency, severity of AUD, negative and injury-related outcomes, type and amount of treatment services received |

| Randomization | Facilitate testing efficacy of AB-CASI intervention |

| Stratification [dependence and language] | Explore treatment modification |

| 1-mo, 6-mo, 12-mo follow-up assessment | Longitudinal assessment testing efficacy in outcomes of interest |

2.2. Participants and setting

The study is being conducted in a large tertiary care center urban ED, American College of Surgeons verified Level 2 trauma center in the northeastern U.S. At the time when trial was started, the city in which the ED is located was known to have 44% of households speaking another language other than English at home and Latinos made up 38% of the more than 144,000 total residents. The population of the hospital’s primary catchment area was 400,000 and included a diverse ethnic and cultural mix. The annual census of the ED was over 77,000 visits of which 35% were Latino, 32% White, 31% Black, and Asian/American Indian/Hawaiian Pacific Islander/Other 2%. To be included in the study, the participant must be an ED patient, self-identify as Latino, and be found to be a high-risk drinker [44,46]. Further details of enrollment criteria are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Self-identified adult Latino ED patients | Current enrollment in alcohol or substance abuse treatment program |

| English and/or Spanish speaking | At the time of enrollment known to be pregnant |

| High-risk drinking [44,46] | Current ED visit for acute psychosis (i.e. suicidal or homicidal ideation) |

| Condition that precludes interview or AB-CASI use i.e., life threatening injury/illness including sexual assault, poor decisional capacity due to cognitive impairment | |

| Police custody | |

| Inability to provide two contact numbers for follow-up |

2.3. Measures

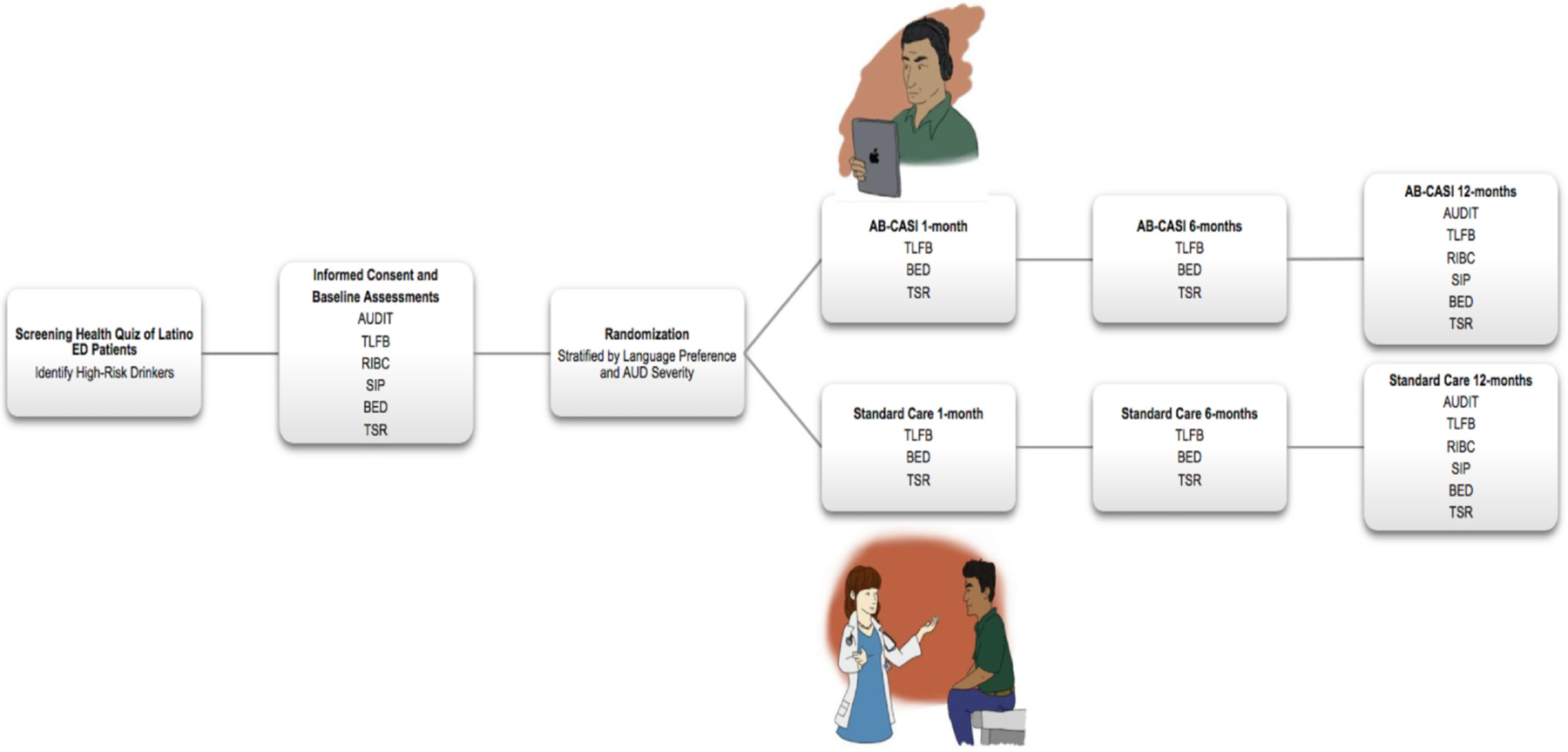

The study assessments and their respective timing (Fig. 1.) were organized in a manner that would allow for rigorous testing of efficacy of the AB-CASI intervention compared to a SC condition with relation to alcohol consumption, negative health behaviors and consequences, and 30-day treatment engagement. Although participants are not blinded to the intervention, interviewers conducting the assessments are blinded to intervention assignment.

Fig. 1.

Schedule of assessments.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test ((AUDIT); Timeline Followback (TLFB); Revised Injury Behavior Checklist (RIBC); Short Inventory of Problems (SIP); Brief Event Data (BED); Treatment Services Review (TSR).

2.4. Screening health quiz (pre-enrollment screening)

Administered in English or Spanish, the Health Quiz contains questions regarding alcohol, tobacco, exercise and seatbelt use [47,48]. The embedded questionnaire (i.e., brief alcohol use pattern screening embedded within a broader personal injury prevention survey) approach has been noted by the World Health Organization to improve the reliability of self-reported behavior. The alcohol questions embedded in the questionnaire ask three standard quantity and frequency questions [44]; 1) On average, how many days per week do you drink alcohol?; 2) On a typical day when you drink, how many drinks do you have?; 3) How many times in the past month have you had “X” or more drinks on any occasion?, where “X” is 5 for men and 4 for women. Patients who admit to a high-risk pattern drinking with consistency (e.g., frequent binge drinking) are identified and approached for consent and inclusion in the trial [44,46].

2.5. Alcohol use disorders identification test ((AUDIT) baseline)

The AUDIT is used at baseline to identify patients with alcohol dependence (AUDIT score ≥ 20) for the purpose of study sample stratification [49]. This metric has good operating characteristics in an emergency department setting [41]. The 10 AUDIT questions cover drinking behavior, adverse psychological reactions, alcohol-related problems, quantity and frequency of consumption. Examples of the AUDIT questions include, “On a typical week, how often do you have a drink containing alcohol- that is beer, wine, liquor, or distilled spirits?” with response options as never; monthly or less; two to four times a month; two to three times a week; four or more times a week; “How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking?” with response options of never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, daily or almost daily.

2.6. Timeline Followback ((TLFB) Baseline, 1-mo, 6-mo, 12-mo)

The validity of self-report data on alcohol consumption has been documented previously and has been used ubiquitously for decades in the alcohol use disorder literature. This overwhelming evidence supports our use of the 28-day TLFB by telephone interview as a good method for capturing quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption and frequency of binging episodes [50–52]. Typically, the interviewer uses a calendar to facilitate questioning of the study participant’s retrospective daily alcohol use (i.e., the previous month). By this method, the interviewer uses “anchors” (e.g., special days of the week for the participant, weekends, and/or holidays in a particular month) to enhance the study participant’s recall of their alcohol consumption both in quantity and frequency.

2.7. Revised injury behavior checklist ((RIBC) baseline, 12-mo)

The RIBC will facilitate assessment of the patient’s injury history, if they needed medical treatment for an injury, or were drinking within hours of an injury event. Originally developed for an adolescent population by Starfield [53], it was revised for use with an injured adult population by Longabaugh [54]. Its construct validity was established by relating it to the AUDIT variables in both college and ED populations. Examples of questions asked in the RIBC include, “During the past 6 months, were you injured while driving a car, truck, or bus?,” with response options as, no, yes, how many times were you injured, for how many of these injuries were you treated by a doctor, for how many of these injuries had you been drinking alcohol within 2 h of the injury; “During the past 6 months, were you injured by being physically attacked?,” with response options as, no, yes, how many times were you injured, for how many of these injuries were you treated by a doctor, for how many of these injuries had you been drinking alcohol within 2 h of the injury.

2.8. Short inventory of problems ((SIP) baseline, 1-mo, 6-mo, 12-mo)

As a validated shortened version of the Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) [55,56]. The SIP contains 15-items and measures several domains (i.e., physical, social, intra/interpersonal) of negative consequences due to drinking. Examples of questions asked in the SIP include, “In the past 6 months, how often have you done impulsive things that you regretted later when you have been drinking?,” with response options as, never, once or a few times, once or twice a week, daily or almost daily; “During the past 6 months, how much have you spent too much or lost a lot of money because of your drinking?,” with response options as, not at all, a little, somewhat, very much.

2.9. Brief event data ((BED) baseline, 1-mo, 6-mo, 12-mo)

The BED contains questions related to motor vehicle events, legal problems, and employment-related events. It provides information that will enable evaluation of alcohol- related negative consequences (driving impaired, riding with impaired driver, injuries, arrests, tardiness, days absent from school or work). Items from this assessment are from the Non-Study Medical Services Form [57,58]. Examples of questions asked in the BED include, “Have you been a driver of a car involved in a crash after drinking or being intoxicated (past 6 months)?,” with response options as, no, almost, yes–once, yes–more than once, and if yes is initially answered, additional questions about who were the passengers in the car (family members, close friends, co-workers, some other person, a minor) is asked; “In the past 30 days, how many full or part days have you missed work because of your own health problems or illness, a family member’s health problem or illness, because of a legal problem, or other problem?,” with response options as, how many were full-days, and how many were part-days.

2.10. Treatment services review ((TSR) Baseline, 1-mo, 6-mo, 12-mo)

The TSR is a brief structured interview that will be administered to collect information on the type and amount of services received by participants [59]. This includes ED visits, hospitalizations, primary medical care visits and self-help sources of support (e.g. Alcoholics Anonymous). All patients who self-report treatment at a specialized treatment facility will have their data verified by the agency. Consent to contact the treatment agency is part of the original consent. Examples of questions asked as part of the TSR include, “Were you hospitalized [INPATIENT] for at least one night for any of the following reasons during the past 6 months?,” with response options as yes or now for, medical problem, surgical problem, psychiatric disorder, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder; “Have you been to see a doctor, dentist, nurse, nurse practitioner, physician’s assistant, counselor, or chiropractor for medical care in an OUTPATIENT setting (include visits related to your participation in this study, or hospitalizations) for any of the following reasons during the past 6 months?,” with response options as yes or now for medical problem, problem related to STI, testing for HIV, surgical problem, psychiatric disorder, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder.

2.11. AB-CASI intervention

The theoretical underpinnings of the AB-CASI intervention are rooted in development and use of the Brief Negotiation Interview (BNI). Over the last 20 years, members of our study team and colleagues, have successfully developed, refined, and empirically tested the BNI in large clinical trials [31–33,60–63]. Originally developed with colleagues at Boston University in conjunction with Rollnick [64], the BNI has been improved over time and enhanced operationally to include 4 key components that include: 1) Raise the Subject of alcohol consumption; 2) Provide Feedback on the patient’s drinking levels and effects; 3) Enhance Motivation to reduce drinking; 4) Negotiate and Advise a plan of action [63]. Moreover, the psychometric properties of the BNI have been previously tested showing good to excellent results [65]. The purpose of the BNI is to assist patients to reduce or abstain from unhealthy alcohol use, or to engage in formal treatment. Combining techniques founded in motivational interviewing as well as the stages of change model, this alcohol SBIRT intervention takes approximately 10-min to complete and has been effectively used in other clinical intervention trials focused on alcohol and drugs [31,33,66,67].

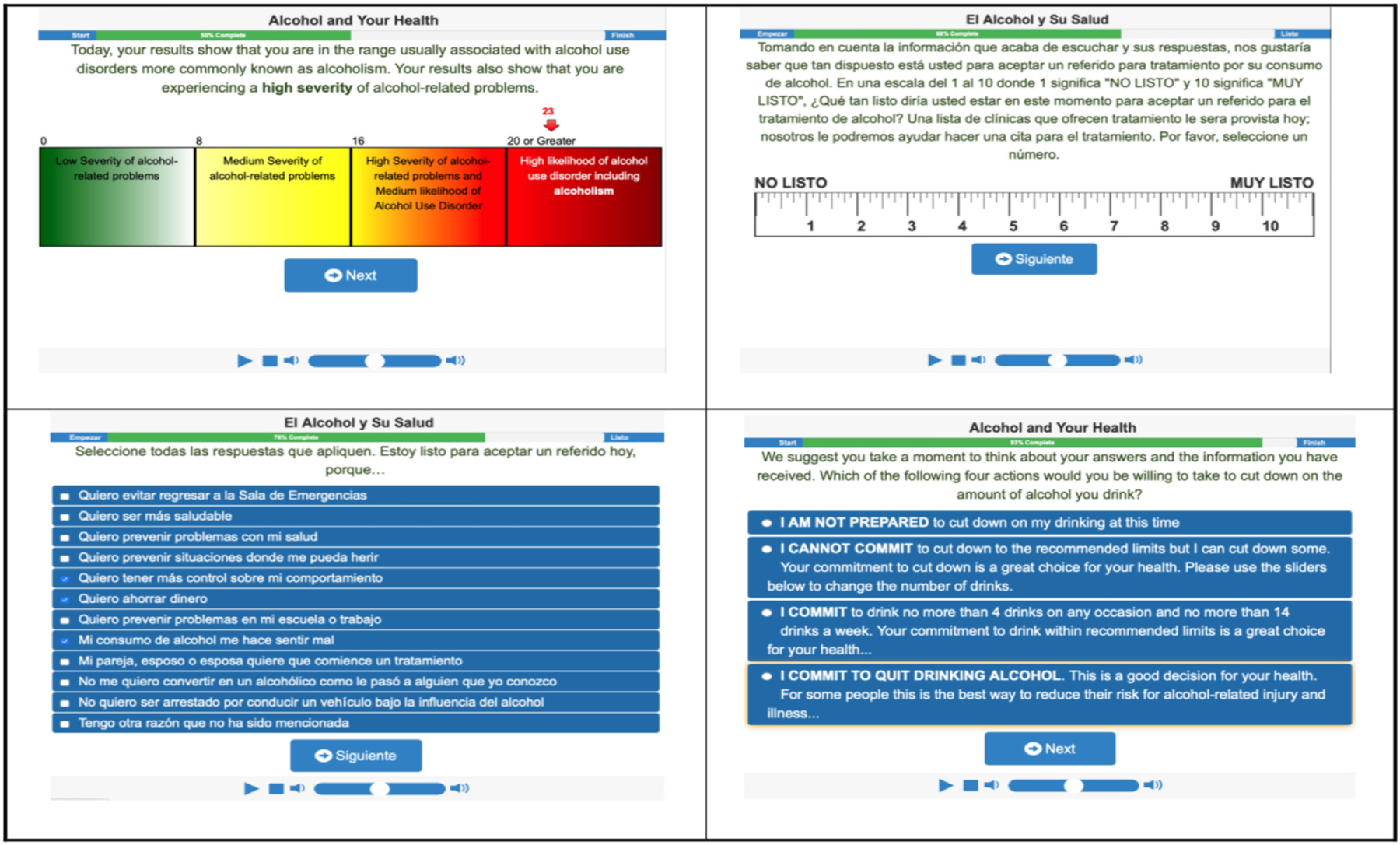

AB-CASI is a bilingual (English or Spanish) digital health tool that was developed for automated bilingual ED-SBIRT [39,68]. The version of the AB-CASI tool used runs on iPads® and is taken to the patient’s bedside by a trained bilingual research assistant. Questions and messages are displayed on the iPad® screen and spoken in English or Spanish through headphones for patient privacy. Recognizing that some Latino patients may be conversationally competent in English but prefer to consume more personal health information in Spanish, patients are able to select the tool interface language based upon their comfort and preference (i.e., in both text and audio) [68]. Demographic information is collected followed by automated administration of the AUDIT. With pre-programmed logic branching, patients who screen as high-risk drinkers receive an automated BNI, including automated personalized feedback, readiness to change evaluation, reasons for cutting down, goal setting, a printed personalized alcohol use reduction plan, and counseling referral information (Fig. 2.). Patients found to be dependent by the AUDIT also receive an automated BNI that includes respectful and reflective questioning, personalized non-judgmental feedback, and supportive communication intentionally focused on treatment engagement. AB-CASI is able to reliably identify high-risk drinkers and AUD in the ED, requires little time, and is highly accepted by patients [38,39].

Fig. 2.

Automated Bilingual Computerized Alcohol Screening and Intervention (AB-CASI): Example screen views in English and Spanish.

2.12. Standard care (SC) condition

Patients randomized to SC do not receive the AB-CASI intervention. However, they receive SC as provided by the treating emergency care provider. All SC patients receive an informational sheet with primary care follow-up recommended. Consultation with social workers are at the discretion of the treating emergency care provider. All requirements for alcohol screening and treatment referral are performed according to the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Level 2 trauma designation [34]. Further, in order to assess the nature of the care provided by the treating emergency care provider, review of the ED record of each enrolled study patient assigned to standard condition will be coded for emergency care provider/physician-initiated assessment (alcohol-related), any intervention and/or referral to treatment services (i.e. any documented discussion about alcohol use or referral to treatment facility in the ED treatment record or discharge instructions).

2.13. Follow-up telephone assessments

Formal telephone assessments by blinded, bilingual research assistants are planned at 1-, 6-, and 12-months. The 1-month follow-up will focus on collecting the extent and frequency of early treatment engagement defined as patient’s report of receiving care in a treatment program that addresses their AUD (e.g. outpatient or inpatient detoxification, therapeutic community) and/or participation in a self-help program (e.g. A.A.). During this assessment, participants are asked if they received any physician-initiated advice regarding their use of alcohol during their visit to the ED. The 6-month follow-up is designed to collect early effects of the intervention on alcohol consumption and to allow enough time to collect sufficient number of negative behaviors and consequences (e.g., impaired driving motor vehicle crash, missing full or partial days of work, contact with the court/criminal justice system) by use of the BED measure, as well as all treatment engagement episodes. The 12-month follow-up assessment is designed to detect long-term effects on alcohol consumption, alcohol-related negative behaviors and consequences, and delayed referral to treatment engagement. Several successful brief intervention studies have used these time intervals and we have chosen the same intervals to facilitate later comparison of previously published studies [54,66,69]. Because of the possibility of a “sleeper effect” or delayed emergence of treatment efficacy [70] [71], it is imperative to conduct the assessments to the 12-month interval and evaluate the effect of the intervention at each follow-up. The use of ancillary services, the occurrence of other injuries and/or illnesses, or advice from other persons may reinforce the BNI. Each of these facets, like the BNI, have the potential to help facilitate readiness for change and movement within the stages of behavior change as described in Prochaska’s transtheoretical model for behavior change [72].

2.14. Data analytic plan

This study was designed as a single-site, randomized parallel group design to test the efficacy of AB-CASI compared to SC in reducing alcohol consumption, alcohol related negative health behaviors and consequences and increase 30-day treatment engagement in Latino unhealthy drinkers, from high-risk drinking to severe AUD. All analyses will consider participants according to their randomized assignment regardless of adherence to protocol (i.e., intention to treat analysis will be conducted).

2.15. Analysis of the primary outcome

The primary objective of the analysis is to test whether AB-CASI will reduce the number of binge episodes more than SC at 12 months. A generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) with a Negative Binomial distribution will be used to estimate differences in the number of binge drinking episodes in the past 28 days at 12 months. More specifically the mixed model will include fixed effects for intervention (AB-CASI vs. SC), time (1, 6, 12 months), and the interaction of intervention with time. Additional fixed effects will be included for baseline covariates (baseline number of drinks per week, baseline number of binge episodes, gender, English vs. Spanish preferred language and dependent status). This analysis will assume that missing data occurs at random (i.e. MAR, not informative). The inclusion of baseline, 1–6- and 12-months outcome data in the model will assist in meeting this assumption. Furthermore, we will evaluate patterns of missing data as well as determine baseline characteristics that are predictive of dropout. If identified, these characteristics will be included in the model to meet the MAR assumption. Modification of the intervention effect by preferred language will be evaluated at the 0.10 significance level by including two and three-way interactions of language with intervention and time. If not significant, these interactions will be excluded and intervention effects pooled across preferred language strata. Similar procedures will be used to assess modification by dependence status. Linear contrasts (at the 0.05 two-sided significance level) will be used to estimate intervention group differences and 95% confidence intervals at the 1-, 6- and 12-month time points.

2.16. Analysis of secondary outcomes

We will test whether number of drinks per week, negative behaviors and consequences (episodes of impaired driving, riding with an impaired driver, injuries, arrests, tardiness, days absent from work/school and SIP) during the 12-month follow-up will be improved in subjects receiving AB-CASI compared to those receiving SC. Similar repeated measures mixed model analysis as that specified for the primary outcome will be implemented for each of the secondary outcomes. Comparison of all secondary outcomes between study groups will be evaluated at the two-sided 0.01 significance level to control inflated type I error from multiple significance testing.

2.17. Analysis of tertiary outcome

We will test the effect of the AB-CASI compared to SC on 30-day treatment engagement. Mantel-Haenszel chi-square analysis will be used to compare the likelihood of 30-day treatment engagement in AB-CASI to SC while adjusting for preferred language and dependent status. Significance will be judged at the two-sided 0.05 significance level. Heterogeneity of treatment effect will be evaluated by the Breslow-Day test. Participants dropping out or lost-to-follow-up will be considered to be not engaged in treatment for the primary analysis.

2.18. Heterogeneity of treatment effects (HTE)

In addition to the stratification factors (AUD severity, preferred language), HTE on the primary outcome will be assessed for subgroups based on factors assessed at baseline (Latino ancestry, age, birthplace, gender, reason for ED visit and smoking status). These subgroup analyses will be conducted within the Generalized Linear Mixed Model framework in an evaluation similar to that proposed for investigating modification by the stratification factors of dependence status and preferred language as described above. Significant interactions will be followed by the estimation and summarization of intervention effects within subgroups at both 1-, 6- and 12-month time points.

2.19. Sample size

Estimation of sample size is based on randomizing and following a sufficient number of unhealthy drinkers to evaluate the primary hypothesis that AB-CASI will result in greater 12-month reductions in the primary outcome, the number of episodes of binge drinking over the past 28-days, compared to SC. Fleming et al. [69]. demonstrated that the number of binge episodes in the past 30-days was reduced by 1.14 in the intervention compared to control conditions. D’Onofrio et al. [73]. reported similar findings in an RCT conducted in hazardous and harmful drinkers. Given the following: 1) power of 80%, 2) a two-sided 0.05 significance level, 3) a standard deviation for number of binge episodes in the past 28 days of 5.2, and 4) a 1:1 intervention allocation, a sample size of 327 subjects per group will be required to detect a 1.14 difference between AB-CASI and SC in the number of binge episodes in the past 28 days at 12 months. A total of 820 unhealthy drinkers will be enrolled and randomized to accommodate up to 20% dropout. To maximize the ability to explore modification by preferred language, we will enroll an equal number of preferred English and Spanish speaking participants.

3. Summary

The described first-of-a-kind ED-RCT, has been intentionally designed to address alcohol-related health disparities in adult U.S. Latino ED patients using AB-CASI. In this trial, we will test the efficacy of the AB-CASI intervention against a SC condition and compare alcohol consumption, negative health behaviors and consequences, and 30-day treatment engagement. Moreover, we will explore variations in intervention outcomes between Latino subpopulations. This study harnesses bilingual digital health tool providing a tablet-delivered brief negotiation interview (BNI). The intervention is conducted in a busy clinical setting that offers unique and important access to this vulnerable population that can benefit from directed disease prevention and health promotion efforts to close alcohol-related disparity gaps. Of particular note, this trial provides the opportunity to expand the evidence that well-known ED-SBIRT barriers (e.g., practitioner time burden, cost of intervention personnel, maintaining intervention fidelity, providing intervention in other languages) can be effectively surmounted. This could potentially reinvigorate and bolster prevention efforts to further advance national ED activities and programs addressing AUDs and ED-SBIRT practice known to currently lag behind national guidelines [74].

The design and efforts in this clinical trial are particularly unique for five reasons. First, the study is closely aligned with the NIAAA’s Strategic Plan to Address Health Disparities and its most recent overall Strategic Plan (2017–2021) committing to advance the science in health disparities and developing interventions that benefit the health of at-risk populations [75,76]. Second, the design of the AB-CASI intervention has been recognized and singled out as a promising approach to address alcohol-related health disparities among racial/ethnic minorities specifically in the area of screening and brief intervention in unique settings that call for the use of innovative methods [77]. Third, with few exceptions [78], nearly all U.S. ED-SIBRT studies have not enrolled Spanish speaking participants. Fourth, none have used an automated bilingual intervention approach that facilitates disclosure of sensitive information. As a result, opportunities have been missed to capitalize on such trials in order to advance the knowledge of AUD and more specifically alcohol-related health disparities in patient-oriented outcomes among the largest minority population in the U.S. Fifth, the described trial, unlike many preceding ED-SBIRT RCTs, sets out to address and enroll participant from the full spectrum of unhealthy drinkers from high-risk drinking to severe AUD. Every day emergency care providers treat patients that present to the ED as a result of unhealthy drinking. As such, an evaluation of a broader ED-SBIRT intervention approach, that is, enrolling the full spectrum of AUD, is more congruent with the what emergency care providers routinely encounter; AUD patients with severity that results in major adverse events, such as acute and chronic physical and/or psychological harm.

We recognize that while the preliminary study of AB-CASI, prior to its proposed scientific testing described here, has shown it to be promising [38,39], it is reasonable to consider that in some U.S. ED settings, the deployment of AB-CASI may still be limited in its full and consistent implementation. In this context, limitations may arise related to the training and accountability of the specific ED personnel/staff that would be responsible for deploying the AB-CASI intervention iPads®. Further, given the ever-rapid-advancing software and hardware technologies, it is possible that the ongoing cost of keeping the AB-CASI intervention technologically current could ultimately blunt or eliminate any significant financial advantage and cost-savings in administering and sustaining meaningful ED-SBIRT efforts. Finally, with the anticipated extensive individual variability of ED workflow in U.S. EDs, it is reasonable to consider that some barriers to optimal integration of the overall AB-CASI intervention process will arise. However, without a large pragmatic study of AB-CASI, it’s difficult to say with any level of certainty that the noted limitations would be insurmountable.

If found to be effective, the AB-CASI intervention could provide more definitive evidence that not only can many previously identified ED-SBIRT barriers by overcome, but also that ED-SBIRT in the described manner could be scaled up and pragmatically implemented to significantly enhance and improve current alcohol brief intervention efforts in the ED. Moreover, because the ED is healthcare safety net for more vulnerable populations that are at greater risk for the development of alcohol-related injury, AUD, and requiring referral for specialized treatment services, an AB-CASI approach could improve the early identification AUD patient and help facilitate their referral to treatment services. On an even broader scale, if AB-CASI is found to be effective, its logical to consider that this approach could afford valuable opportunities for intervention adaptation. That is, it may also lend itself to systematic implementation of AB-CASI in a number of other languages as well as use in primary care where more recent literature suggests the need for greater scope of not only intentional screening but also monitoring of reductions in alcohol use as well as medical treatment of AUDs, both to the benefit of patients [79,80].

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Vanessa Zuniga, Jessica Navarro, Renny Parrilla and Yesenia Torres for their tireless work and commitment to this important clinical trial. We thank the Yale Center for Clinical Investigation (YCCI) and their support and use of the OnCore Clinical Trials Management System (Forte Research, Madison, WI).

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health, Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health (OD), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) under Award Number R01AA022083.

References

- [1].Chartier KG, Caetano R, Trends in alcohol services utilization from 1991–1992 to 2001–2002: ethnic group differences in the U.S. population, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 35 (8) (2011) 1485–1497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Keyes KM, Liu XC, Cerda M, The role of race/ethnicity in alcohol-attributable injury in the United States, Epidemiol. Rev 34 (1) (2012) 89–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].U.S. Census Bureau, Hispanic Heritage Month, (2017), p. 2017.

- [4].Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE, Disparities in alcohol-related problems among white, black, and Hispanic Americans, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 33 (4) (2009) 654–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Rodriguez LA, The Hispanic Americans baseline alcohol survey (HABLAS): DUI rates, birthplace, and acculturation across Hispanic national groups, J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 69 (2) (2008) 259–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Witbrodt J, Mulia N, Zemore SE, Kerr WC, Racial/ethnic disparities in alcohol-related problems: differences by gender and level of heavy drinking, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 38 (6) (2014) 1662–1670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chartier K, Caetano R, Ethnicity and health disparities in alcohol research, Alcohol. Res. Health 33 (1–2) (2010) 152–160. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tapper EB, Parikh ND, Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999–2016: observational study, BMJ 362 (2018) k2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Flores YN, Yee HF Jr., Leng M, Escarce JJ, Bastani R, Salmeron J, Morales LS, Risk factors for chronic liver disease in blacks, Mexican Americans, and whites in the United States: results from NHANES IV, 1999–2004, Am. J. Gastroenterol 103 (9) (2008) 2231–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Stinson FS, Grant BF, Dufour MC, The critical dimension of ethnicity in liver cirrhosis mortality statistics, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 25 (8) (2001) 1181–1187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Alcohol Research Group and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Alcohol Survey: 1984, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Galvan FH, Caetano R, Alcohol use and related problems among ethnic minorities in the United States, Alcohol Res. Health 27 (1) (2003) 87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Caetano R, Clark CL, Trends in alcohol-related problems among whites, blacks, and Hispanics: 1984–1995, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 22 (2) (1998) 534–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Caetano R, Clark CL, Trends in alcohol consumption patterns among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984 and 1995, J. Stud. Alcohol 59 (6) (1998) 659–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chartier KG, Scott DM, Wall TL, Covault J, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mills BA, Luczak SE, Caetano R, Arroyo JA, Framing ethnic variations in alcohol outcomes from biological pathways to neighborhood context, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 38 (3) (2014) 611–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Alcohol Use and Alcohol use Disorders in the United States: Main Findings from the 2001–2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC), National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Caetano R, Prevalence, incidence and stability of drinking problems among whites, blacks and Hispanics: 1984–1992, J. Stud. Alcohol 58 (6) (1997) 565–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chartier KG, Vaeth PAC, Caetano R, Focus on: ethnicity and the social and health harms from drinking, Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev 35 (2) (2013) 229–237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Mulia N, Tam TW, Bond J, Zemore SE, Li L, Racial/ethnic differences in life-course heavy drinking from adolescence to midlife, J. Ethn. Subst. Abus 17 (2) (2018) 167–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Caetano R, Vaeth PA, Chartier KG, Mills BA, Epidemiology of drinking, alcohol use disorders, and related problems in US ethnic minority groups, Handb. Clin. Neurol 125 (2014) 629–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Levitt E, Ainuz B, Pourmoussa A, Acuna J, De La Rosa M, Zevallos J, Wang W, Rodriguez P, Castro G, Sanchez M, Pre- and post-immigration correlates of alcohol misuse among young adult recent Latino immigrants: an Ecodevelopmental approach, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16 (22) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF, Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on alcohol and related conditions, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64 (7) (2007) 830–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS, Huang B, Ruan WJ, Recovery from DSM-IV alcohol dependence: United States, 2001–2002, Addiction 100 (3) (2005) 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Caetano R, Alcohol-related health disparities and treatment-related epidemiological findings among whites, blacks, and Hispanics in the United States, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 27 (8) (2003) 1337–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Caetano R, Clark CL, Hispanics, blacks and White driving under the influence of alcohol: results from the 1995 national alcohol survey, Accid Anal. Prev 32 (1) (2000) 57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rui P, Kang K, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2017 Emergency Department Summary Tables, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/web_tables.htm, (2019).

- [27].White AM, Slater ME, Ng G, Hingson R, Breslow R, Trends in alcohol-related emergency department visits in the United States: results from the Nationwide emergency department sample, 2006 to 2014, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 42 (2) (2018) 352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mullins PM, Mazer-Amirshahi M, Pines JM, Alcohol-related visits to US emergency departments, 2001–2011, Alcohol Alcohol 52 (1) (2017) 119–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].White AM, Castle IP, Hingson RW, Powell PA, Using death certificates to explore changes in alcohol-related mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2017, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 44 (1) (2020) 178–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Havard A, Shakeshaft A, Sanson-Fisher R, Systematic review and meta-analysis of strategies targeting alcohol problems in emergency departments: interventions reduce alcohol-related injuries, Addiction 103 (3) (2008) 368–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, Busch SH, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, O’Connor PG, Brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department, Ann. Emerg. Med 51 (6) (2008) 742–750 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Academic ED SBIRT Research Collaborative, The impact of screening, brief intervention, and referral for treatment on Emergency Department Patients’ Alcohol Use, Ann. Emergency Med 50 (6) (2007) 699–710.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].D’onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O’Connor PG, A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients, Ann. Emerg. Med 60 (2) (2012) 181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].American College of Surgeons - Committee on Trauma, Screening and Brief Intervention Training for Trauma Care Providers, https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/trauma/publications/sbirtguide.ashx, (2007) (Accessed March 28 2020).

- [35].D’Onofrio G, Becker B, Woolard RH, The impact of alcohol, tobacco, and other drug use and abuse in the emergency department, Emerg. Med. Clin. North Am 24 (4) (2006) 925–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cherpitel CJ, Screening and brief intervention for alcohol problems in the emergency room: is there a role for nursing? J. Addict. Nurs 17 (2) (2006) 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Vaca FE, Winn D, The basics of alcohol screening, brief intervention and referral to treatment in the emergency department, West. J. Emerg. Med 8 (3) (2007) 88–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vaca FE, Winn D, Anderson CL, Kim D, Arcila M, Six-month follow-up of computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the emergency department, Subst. Abus 32 (3) (2011) 144–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Vaca F, Winn D, Anderson C, Kim D, Arcila M, Feasibility of emergency department bilingual computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment, Subst. Abus 31 (4) (2010) 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Cunningham RM, Bernstein SL, Walton M, Broderick K, Vaca FE, Woolard R, Bernstein E, Blow F, D’Onofrio G, Alcohol, tobacco, and other drugs: future directions for screening and intervention in the emergency department, Acad. Emerg. Med 16 (11) (2009) 1078–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Cherpitel CJ, Screening for alcohol problems in the emergency department, Ann. Emerg. Med 26 (2) (1995) 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].De Leeuw E, Hox J, Kef S, Computer-assisted self-interviewing tailored for special populations and topics, Field Methods 15 (3) (2003) 223–251. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tourangeau R, Smith TW, Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context, Public Opin. Q 60 (2) (1996) 275–304. [Google Scholar]

- [44].National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide Updated 2005 Edition US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2007, 2020. (Reprinted). [Google Scholar]

- [45].National Institute for Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rethinking Drinking, Alcohol and Your Health, https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/Is-your-drinking-pattern-risky/Drinking-Levels.aspx, (2020) (Accessed April 10 2020).

- [46].U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, Appendix 9. Alcohol, 101–103, 2015.

- [47].Fleming MF, Barry KL, A three-sample test of a masked alcohol screening questionnaire, Alcohol Alcohol 26 (1) (1991) 81–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Fleming MF, Bruno M, Barry K, Fost N, Informed consent, deception, and the use of disguised alcohol questionnaires, Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 15 (3) (1989) 309–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG, The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care, World Health Organization, Department of Mental Health and Substance Dependence, Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Breslin C, Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Buchan G, Kwan E, Aftercare telephone contacts with problem drinkers can serve a clinical and research function, Addiction 91 (9) (1996) 1359–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sobell LC, Appendix: Instrument fact sheets, alcohol timeline Followback (TLFB), in: Allen JP, Willson VB (Eds.), Assessing Alcohol Problems: A Guide for Clinicians and Researchers, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, 2003, pp. 301–305. [Google Scholar]

- [52].Cohen BB, Vinson DC, Retrospective self-report of alcohol consumption: test-retest reliability by telephone, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 19 (5) (1995) 1156–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Starfield B, Injury Behavior Checklist (Adapted Version) Subscale, Adolescent Health Status Instrument John Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- [54].Longabaugh R, Woolard RE, Nirenberg TD, Minugh AP, Becker B, Clifford PR, Carty K, Sparadeo Licsw F, Gogineni A, Evaluating the effects of a brief motivational intervention for injured drinkers in the emergency department, J. Stud. Alcohol 62 (6) (2001) 806–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R, The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse Test manual (Project MATCH Monograph Series Vol 4), National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Rockville, MD, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- [56].Marra LB, Field CA, Caetano R, von Sternberg K, Construct validity of the short inventory of problems among Spanish speaking Hispanics, Addict. Behav 39 (1) (2014) 205–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Polsky D, Glick HA, Yang J, Subramaniam GA, Poole SA, Woody GE, Cost-effectiveness of extended buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for opioid-dependent youth: data from a randomized trial, Addiction 105 (9) (2010) 1616–1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Murphy SM, Campbell AN, Ghitza UE, Kyle TL, Bailey GL, Nunes EV, Polsky D, Cost-effectiveness of an internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: data from a multisite randomized controlled trial, Drug Alcohol Depend 161 (2016) 119–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].McLellan TA, Zanis D, Incmikoski R, Treatment Service Review (TSR) the Center for Studies in Addiction, Philadelphia VA Medical Center & The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Department of Psychiatry, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC, Norcross JC, In search of how people change: applications of addictive behaviors, Am. Psychol 47 (9) (1992) 1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].D’Onofrio G, O’Connor PG, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Busch SH, Owens PH, Bernstein SL, Fiellin DA, Emergency department-initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial, JAMA 313 (16) (2015) 1636–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ryan S, Pantalon MV, Camenga D, Martel S, D’Onofrio G, Evaluation of a Pediatric resident skills-based screening, Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) Curriculum for Substance Use, J. Adolesc. Health 63 (3) (2018) 327–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].D’Onofrio G, Pantalon MV, Degutis LC, Fiellin DA, O’Connor G, Development and implementation of an emergency practitioner-performed brief intervention for hazardous and harmful drinkers in the emergency department, Acad. Emerg. Med 12 (3) (2005) 249–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].D’Onofrio G, Bernstein E, Rollnick S, Motivating patients for change: a brief strategy for negotiation, in: Bernstein E, Bernstein J (Eds.), Case studies in Emergency Medicine and the health of the Public Jones and Bartlett, 1996, pp. 295–303 Boston. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Pantalon MV, Martino S, Dziura J, Li FY, Owens PH, Fiellin DA, O’Connor PG, D’Onofrio G, Development of a scale to measure practitioner adherence to a brief intervention in the emergency department, J. Subst. Abus. Treat 43 (4) (2012) 382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Neumann T, Neuner B, Weiss-Gerlach E, Tonnesen H, Gentilello LM, Wernecke KD, Schmidt K, Schroder T, Wauer H, Heinz A, Mann K, Muller JM, Haas N, Kox WJ, Spies CD, The effect of computerized tailored brief advice on at-risk drinking in subcritically injured trauma patients, J. Trauma 61 (4) (2006) 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].D’Onofrio G, Degutis LC, Integrating project ASSERT: a screening, intervention, and referral to treatment program for unhealthy alcohol and drug use into an urban emergency department, Acad. Emerg. Med 17 (8) (2010) 903–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Abujarad F, Vaca FE, mHealth tool for alcohol use disorders among Latinos in emergency department, Proc. Int. Symp. Hum. Factors Ergon Healthc 4 (1) (2015) 12–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Fleming MF, Barry KL, Manwell LB, Johnson K, London R, Brief physician advice for problem alcohol drinkers. A randomized controlled trial in community-based primary care practices, Jama 277 (13) (1997) 1039–1045. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].O’Malley SS, Jaffe AJ, Chang G, Rode S, Schottenfeld R, Meyer RE, Rounsaville B, Six-month follow-up of naltrexone and psychotherapy for alcohol dependence, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 53 (3) (1996) 217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Nich C, Gordon LT, Wirtz PW, Gawin F, One-year follow-up of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for cocaine dependence. Delayed emergence of psychotherapy effects, Arch. Gen. Psychiatr 51 (12) (1994) 989–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, The transtheoretical model of health behavior change, Am. J. Health Promot 12 (1) (1997) 38–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, Chawarski MC, Owens PH, Degutis LC, Busch SH, Bernstein SL, O’Connor PG, A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients, Annals of emergency medicine 60 (2) (2012) 181–192, 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Cunningham RM, Harrison SR, McKay MP, Mello MJ, Sochor M, Shandro JR, Walton MA, D’onofrio GD, National survey of emergency department alcohol screening and intervention practices, Ann. Emerg. Med 55 (6) (2010) 556–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, NIAAA’s Strategic Plan to Address Health Disparities, http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/HealthDisparities/Strategic.html (Accessed March 28 2020).

- [76].National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Strategic Plan 2017–2021 https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/StrategicPlan_NIAAA_optimized_2017-2020.pdf, (2017) (Accessed March 28 2020).

- [77].Zemore SE, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Mulia N, Kerr WC, Ehlers CL, Cook WK, Martinez P, Lui C, Greenfield TK, The future of research on alcohol-related disparities across U.S. racial/ethnic groups: a plan of attack, J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs 79 (1) (2018) 7–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Field CA, Caetano R, Harris TR, Frankowski R, Roudsari B, Ethnic differences in drinking outcomes following a brief alcohol intervention in the trauma care setting, Addiction 105 (1) (2010) 62–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Carvalho AF, Heilig M, Perez A, Probst C, Rehm J, Alcohol use disorders, Lancet 394 (10200) (2019) 781–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Witkiewitz K, Kranzler HR, Hallgren KA, O’Malley SS, Falk DE, Litten RZ, Hasin DS, Mann KF, Anton RF, Drinking risk level reductions associated with improvements in physical health and quality of life among individuals with alcohol use disorder, Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res 42 (12) (2018) 2453–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]