Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) have a significant impact on families. Family nurses are in an ideal position to address the needs of families affected by ADRD. However, to be most effective, family nurses and researchers need culturally appropriate theories to guide practice and research. On November 17, 2018, five nurse researchers presented findings of their research with African American families at the Gerontological Society of America’s annual meeting. The results reported and the lively discussion that ensued suggested that the current paradigms framing research and practice with African American families affected by ADRD may not be adequate. There is a need to consider culturally congruent, family-centered theories to guide research and practice.

Keywords: cultural congruence, Alzheimer’s disease, nursing theory, older adult, family

The number of older adults living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) is projected to increase significantly over the next decade (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). Family caregivers of older adults with ADRD often perform complex tasks such as activities of daily living, financial management, and medication management (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). Yet these family caregivers are often unprepared for the responsibilities of the role (Skufca, 2017). As a result, ADRD caregiving is associated with negative effects on family caregivers’ health, including burden, depression, poor sleep, and poorer quality of life (Andreakou, Papadopoulos, Panagiotakos, & Niakas, 2016; Alzheimer’s Association, 2019; ((D’Aoust, Brewster, & Rowe, 2015). This caregiving role not only affects the caregivers themselves but also contributes to the placement of people living with ADRD into assisted living communities and nursing homes (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019).

Approximately one tenth of the 15 million family caregivers for adults living with ADRD in the United States of America are African American (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). ADRD is a major concern for African American family caregivers because African American individuals are twice as likely to develop ADRD compared to non-Hispanic White individuals (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). At the 2018 annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America (GSA), five nurse researchers presented a symposium focused on the experience of African American family caregivers of older adults with ADRD. Following the presentations, the researchers and the audience engaged in a lively discussion about some conceptual challenges identified while conducting each of these studies. The purpose of this commentary is to describe three of the conceptual challenges: family structure, caregiving burden, and the context of caregiving. In addition, we provide recommendations for future directions for research with African American family caregivers of persons living with ADRD.

The Family Structure of African American Family Caregivers

Family caregivers of persons living with ADRD are usually women— wives, daughters and daughters-in-law (Alzheimer’s Association, 2019). Frequently, researchers focus on individual caregivers (Epps, 2014) or caregiving dyads (Epps, Skemp, & Specht, 2016; Moss et al., 2018a; Nagpal, Heid, Zarit, & Whitlatch, 2015). Although studies of dyads can be meaningful, focusing solely on dyadic relationships may miss intergenerational kinship and multigenerational relationships, which are a source of strength for African American families.

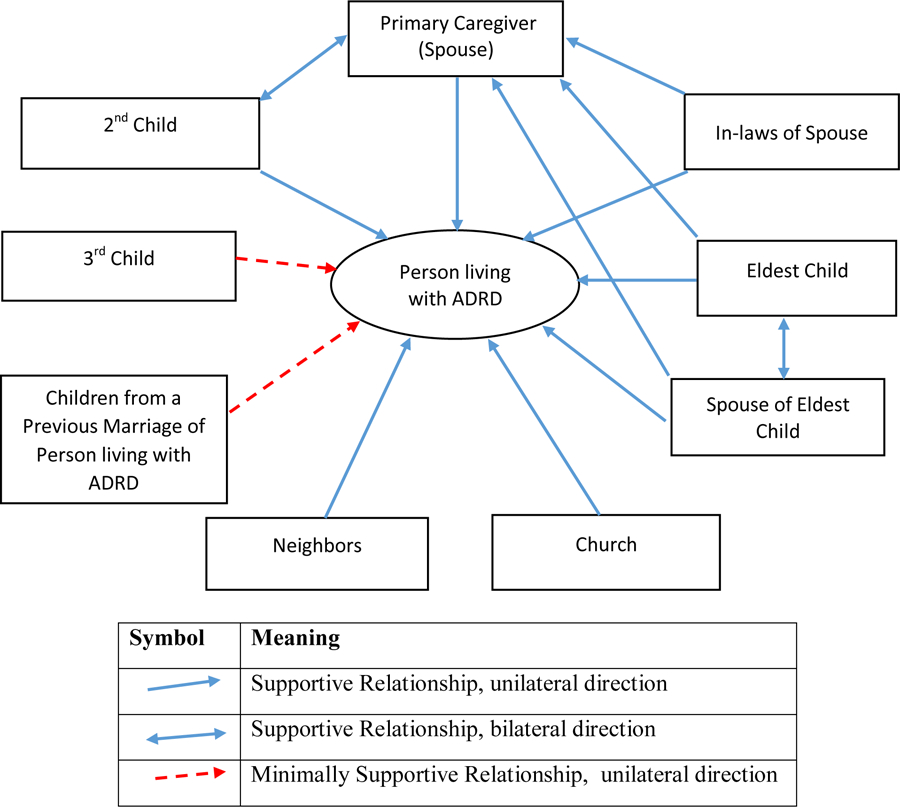

During the symposium, Dr. Fayron Epps reported on a qualitative study of 26 community-dwelling family caregivers and 18 persons living with ADRD (Epps, Rose, & Lopez, 2019). Her team used MindMaple Lite® (MindMaple Softonics, 2018) and created sociograms to depict the relationships within families (see Figure 1). These sociograms demonstrated that families were complex and composed of numerous people, including spouses, children, siblings, and non-blood relatives. Individual family members were connected by a variety of mechanisms including birth, marriage, adoption, friendship, and church membership. Some bonds were strong and supportive and were strengthened by familism, obligation, and religiosity. Family members provided physical, emotional, financial, social, and instrumental support. Some relationships were weak or broken by divorce, disagreements, or drug addiction. Frequently, support and care were unidirectional and directed to the family member living with ADRD. Although it was less frequent, it was interesting to note there were instances in which the person with ADRD also contributed to the family network. This occurrence was more common among people with less severe ADRD.

Figure 1.

Example of a sociogram of a family network. Solid lines represent supportive relationships. Dotted lines represent minimally supportive relationships. Arrows illustrate the direction of support and care. ADRD= Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias

Taken together, these findings demonstrate the importance of expanding the definition of family caregivers beyond dyads. African American families consist of complicated connections between functional relations, shared values, affiliations, geographic location, and blood ties (Allen, 1995). Families frequently consist of multiple relationships, including those among spouses, children and parents, extended family members, and friends. Especially in African American families, there may not be one central caregiver, but a group of people who coordinate the care of the person living with ADRD. These family networks provide support and strength to primary caregivers (Clay, Roth, Wadley, & Haley, 2008; Lincoln, Taylor, & Chatters, 2013). Primary caregivers who have an extended family network receive more social support and have positive views about caregiving (Cho, Ory, & Stevens, 2016; Heo, 2014). Moreover, the ability of the person with ADRD to provide reciprocity to their care provider reduces stress and burden experienced by a caregiver (Dwyer, Lee, & Jankowski, 1994). In addition, researchers and clinicians can focus on the ways in which persons living with ADRD contribute to and provide support within family networks.

Researchers and clinicians may benefit from theories that define family caregivers beyond dyads. Waites (2009) proposed The Afrocentric Intergenerational Solidarity Model to guide practice and research with African American families. The model provides a framework to explore how intergenerational relationships can be supported by identifying strengths and assets that each generation can provide. In addition, the model taps into power, resilience and capital from past and current traditions and relationships. The model identifies five solidarity elements: associational (family traditions), affectional (emotional connections), consensual (family values), functional (helping network), and normative (expectations family roles). Although developed for social work practice, the model holds promise as a framework to guide practice and research involving African American families. Expanding research to examine solidarity elements of African American caregiving networks may lead to a better understanding of the complex functioning of these networks, and the stressors and strengths experienced by these networks may help explain physical and emotional health outcomes for African American families affected by ADRD.

Adequacy of Current Caregiver Burden Measures

Much of the research on caregivers of persons living with ADRD assumes that caregiving is stressful and burdensome (Cheng, 2017; Chiao, Wu, & Hsiao, 2015). Burden has been conceptualized as the subjective and objective impact of the physical, psychological, social, and financial problems experienced by family caregivers, or the negative impact of caring for the person living with ADRD (Acton & Kang, 2001). However, research suggests that differences exist between how African American and non-Hispanic White family caregivers of persons living with ADRD experience and perceive stress and burden (Armstrong, Gitlin, Parisi, Roth, & Gross, 2019; Scott, Clay, Epps, Cothran, & Williams, 2018).

At the symposium, Dr. Susan McLennon described results of a mixed-methods study of burden among 14 African American family caregivers (McLennon, 2018). She found that despite providing care to family members with moderate to severe ADRD for an average of five years, the caregivers’ burden scores as measured by the Zarit Burden Scale, a self-report caregiver burden scale (Zarit, Reever, & Bach-Peterson, 1980), were low. However, qualitative data generated from in-depth interviews suggested otherwise. Most caregivers reported hardships including financial constraints, safety concerns such as wandering, and challenges related to providing physical care. Similarly, Dr. Karen Moss reported that in her mixed-methods study with African American caregivers, many participants reported stressful, negative aspects pertaining to caregiving, even though they scored relatively high on quantitative measures of quality of life (Moss et al., 2018b). These findings stimulated several thoughtful comments during the question and answer period of the symposium. For example, the audience conversed about whether burden was a culturally congruent concept among African American caregivers. Burden is a negative aspect of caregiving and is often accompanied by emotional lability, limited or overwhelmed coping mechanisms, and challenges with adapting or responding to the needs of the person with ADRD (Hansen, Hodgson, Budhathoki, & Gitlin, 2018; Roth, Fredman, & Haley, 2015). African American caregivers qualitatively reported challenges to caregiving both within themselves and within the dynamics of the changing relationship with the person living with ADRD (Hansen, Hodgson, & Gitlin, 2019). Although, fewer African American caregivers reported being upset by verbal aggression from persons living with ADRD compared with non-Hispanic White caregivers (Hansen et al., 2018).

Bias may be introduced in study measures with phrasing questions negatively such as, “Do you feel stressed between caring for your relative and trying to meet other responsibilities (work/family)?” rather than the use of neutral wording (Zarit et al., 1980). For African American families, caregiving may be considered a normal expectation rather than a disruption. Therefore, researchers should be cautious about their use of the term burden and consider using or developing instruments that are sensitive to racial differences in conceptualization of burden (Armstrong et al., 2019). One measure that considers the lived experiences of African American caregivers is the Cultural Justification Scale for Caregiving (Dilworth-Anderson, Goodwin, & Williams, 2004). The 10-item measure examines the cultural reasons for providing care and predicted physical health outcomes in African American caregivers (Dilworth-Anderson et al., 2004). Another measure that is not specifically focused on caregiving but on the experiences of African American women is the Giscombe Superwoman Schema Questionnaire (Woods-Giscombe et al., 2019). The questionnaire provides preliminary research supporting the five factors of the Superwoman Schema (Woods-Giscombe, 2010), which could explain the misalignment of burden and stress reported by African American caregivers.

African American cultural values including familism and filial piety could influence appraisal of stress and coping. Knight and Sayegh (2010) found that high levels of familism were associated with higher appraisal of burden. Reviewing the literature to identify causes of racial and ethnic differences on caregiving burden led them to conclude that differences in reported burden were better explained by cultural differences in social support and coping. Furthermore, an updated sociocultural stress and coping model should focus on research to identify specific cultural values associated with caregiver burden and positive and negative appraisals of caregiving.

Social and Historical Context of Caregiving

Research evaluating interventions for family caregivers is important for guiding practice. Dr. Glenna Brewster presented the results of a secondary data analysis (Brewster et al., 2018), which tested the effect of The Great Village, a psychoeducational intervention with and without exercise, on sleep quality among 142 African American family caregivers of people living with ADRD over a six-month period of time. She and her team hypothesized that the intervention adapted for African American caregivers from the Savvy Caregiver program (Samson, Parker, Dye, & Hepburn, 2016) would improve sleep through the mediating effect of reduced caregiver burden and improved mental health outcomes and mastery (Brewster, Epps, Dye, Hepburn, Higgins, & Parker, 2019; Tomiyama et al., 2012; von Känel et al., 2010). While The Great Village reduced burden and improved mental health outcomes and mastery (Brewster et al., 2019), African American family caregivers experienced no significant improvement in their poor sleep quality. While there are many conceivable reasons that the intervention failed to achieve statistically significant changes in this population, the audience was also interested in whether the intervention was adequately adapted to meet the needs of African American family caregivers.

Gallagher-Thompson and colleagues (2000) suggest that interventions be carefully adapted to meet the special needs of various ethnic and racial populations. Superficial adaptations such as changing pictures to include African Americans does not account for actual cultural and contextual differences. Instead, researchers must be knowledgeable about African American explanatory models and culturally prescribed views about ADRD. For example, ADRD may be considered a symptom of stress, a normal part of aging, or minimized, if the older adult is able to participate in family activities (Hinton, Franz, Yeo, & Levkoff, 2005). Similarly, the impact of historical context such as (a) the effect of slavery on the development of the family and churches as primary support institutions, (b) the impact of the U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee and Henrietta Lacks’ story on the mistrust of researchers and health systems, and (c) the effects of implicit, explicit, and structural racism on mental and physical health must be considered from the design of the intervention to the selection of outcome measures (Ejiogu et al., 2011; Jones & Jablonski, 2014; Kennedy, Mathis, & Woods, 2007; Williams, Meisel, Williams, & Morris, 2011). These concerns highlight the importance of using culturally congruent theoretical frameworks to guide practice and research with African American family caregivers. According to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care and Services (2018), these frameworks should help identify mechanisms that increase risk for disparities among older adults living with ADRD and their caregivers.

Dr. Kalisha Bonds used The Negro Family as a Social System conceptual framework (Billingsley, 1968, 1988) to guide the study she presented at the symposium. The study examined modifiable risks and protective factors associated with quality of life of African American family caregivers and African American persons living with ADRD. This theory suggests that African American families should be examined for both their structure and function. Functions include instrumental (education, job stability, income house and health care), expressive (belonging, self-worth, family cohesion), and instrumental-expressive (education, adjustment to parent role, mental health of children). The theorist suggested that families should also be examined within the context of their community (regional location, socioeconomic status, and surrounding neighborhoods), as well as, the wider society (health care, education and political systems). While this theory has predominantly been used in sociology, the theory was useful in highlighting strengths of the African American family.

Additional theories that account for historical and structural policies may also contribute to a better understanding of African American family caregivers. For example, the Black Family Socio-Ecological Context model may guide researchers to explore connections between institutional, interpersonal, environmental, temporal, and cultural factors that shape the character of African American families (Allen, 1995). Similarly, Woods-Giscombe (2010) developed the Superwoman Schema using focus group discussions with diverse African American women. Through these focus groups, Dr. Woods-Giscombe characterized benefits and liabilities to the Superwoman role (Woods-Giscombe, 2010). Benefits included self-survival and preserving the African American family and community (Woods-Giscombe, 2010). But the Superwoman role also had liabilities, including relationship strain and stress-related behaviors (Woods-Giscombe, 2010). Each of these theoretical frameworks may guide clinicians and researchers to consider developing and testing interventions that are not superficial adaptations of interventions but interventions that are informed by critical analysis of the impact of race and gender, and are rooted in the African American experience, thus addressing the complexity of African American families.

Finally, all the researchers agreed that future work must be relevant and contribute to healthcare improvements in the African American community. Community-based research designs— which engage study participants from conceptualization of the research questions to application of the findings— hold promise as a method to ensure the research is relevant. Given the historical mistreatment of African Americans in research, today’s researchers and nurse scientists must ensure that they engage with and give back to the community as they conduct and disseminate their research (Fryer et al., 2016).

Future Directions for ADRD African American Family Caregiving Research

We have several recommendations for future directions for research focused on ADRD caregiving in African American families. First, we suggest future researchers use multi-method research approaches to capture the experiences of African Americans in their caregiving roles. Second, the definition of family should be broadened to include everyone involved in coordinating care for the person living with ADRD. Third, the use of sociograms to diagram these relationships may be helpful. Fourth, conduct more qualitative/exploratory and mixed-methods research to better evaluate variations in families. Fifth, there is a need to clearly define the concept of burden to better describe the experiences of African American family caregivers. Lastly, the use of culturally sensitive conceptual frameworks or adaptation and development of new theoretical models, which focus on how different cultures experience ADRD family caregiving will be helpful in meeting the specific needs of this population.

Family nurses are especially well equipped to address the needs of families affected by ADRD. Aligning with the International Family Nursing Association (IFNA), the goal of family nursing practice is to identify families’ strengths, support family and individual growth, improve family self-management, facilitate successful life transitions, improve and manage health, and mobilize family resources (IFNA, 2018). To meet this goal, certain assumptions of family are necessary (IFNA, 2018). Families consist of a group of individuals connected by strong emotional ties and a desire to be together, families are made of unique individuals, and each family’s perspectives of health and culture is unique (IFNA, 2018). Family nurses must have essential knowledge of family nursing theory and aim for a culturally sensitive approach that incorporates each family’s context and cultural practices. A deeper understanding of the effect of ADRD within African American families is therefore particularly important for family nurses as it will enable the delivery of more person-centered, culturally appropriate family-friendly care.

Acknowledgements:

We acknowledge Dr. Karen Rose who was the discussant for the symposium. The National Institute of Nursing Research [P01-NR011587] and National Institute on Aging [R01AG054079] supported Dr. Glenna Brewster’s research. Dr. Kalisha Bonds’ work was supported by Oregon Health & Science University School of Nursing Dean’s Alumni Scholarship and Pierce Scholarship, her appointment as a Jonas Veterans Healthcare Scholar (2016–2018) through the Jonas Foundation, SAMHSA-ANA [1H79SM080386–01], and partially funded through the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research grant number [2T32NR012715] (PI: S. Dunbar) for trainee Kalisha Bonds. The views expressed in written training materials or publications and by speakers and moderators do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. government. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interest: None of the authors has any conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Acton GJ, & Kang J (2001). Interventions to reduce the burden of caregiving for an adult with dementia: A meta-analysis. Research in Nursing and Health, 24, 349–360. 10.1002/nur.1036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen WR (1995). African American family life in societal context: Crisis and hope. Sociological Forum, 10, 569–592. 10.1007/bf02095769 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2019). 2019 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Retrieved from https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures-2019-r.pdf

- Andreakou MI, Papadopoulos AA, Panagiotakos DB, & Niakas D (2016). Assessment of health-related quality of life for caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease patients. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 2016, 9213968 10.1155/2016/9213968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong NM, Gitlin LN, Parisi JM, Roth DL, & Gross AL (2019). Association of physical functioning of persons with dementia with caregiver burden and depression in dementia caregivers: an integrative data analysis. Aging and Mental Health, 23, 587–594. 10.1080/13607863.2018.1441263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billingsley A (1988). Black Families in White America. New York, New York: Touchstone Books; (Original work published 1968). [Google Scholar]

- Brewster GS, Epps F, Dye CE, Hepburn K, Higgins MK, & Parker ML (2019). The effect of the “Great Village” on psychological outcomes, burden, and mastery in African American caregivers of Persons living with dementia. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 10.1177/0733464819874574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brewster G, Parker MW, Epps F, Dye C, Higgins M, Bliwise DL, & Hepburn K (2018). Does a psychoeducational intervention with and without exercise affect sleep quality in African American caregivers? Innovation in Aging, 2, Issue suppl_1, 391 10.1093/geroni/igy023.1458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng ST (2017). Dementia caregiver burden: A research update and critical analysis. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19, 64 10.1007/s11920-017-0818-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao CY, Wu HS, & Hsiao CY (2015). Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 62, 340–350. 10.1111/inr.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho J, Ory MG, & Stevens AB (2016). Socioecological factors and positive aspects of caregiving: Findings from the REACH II intervention. Aging and Mental Health, 20, 1190–1201. 10.1080/13607863.2015.1068739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay OJ, Roth DL, Wadley VG, & Haley WE (2008). Changes in social support and their impact on psychosocial outcome over a 5-year period for African American and White dementia caregivers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 857–862. 10.1002/gps.1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aoust RF, Brewster G, & Rowe MA (2015). Depression in informal caregivers of persons with dementia. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10, 14–26. 10.1111/opn.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Goodwin PY, & Williams SW (2004). Can culture help explain the physical health effects of caregiving over time among African American caregivers? The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 59, S138–145. 10.1093/geronb/59.3.s138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer JW, Lee GR, & Jankowski TB (1994). Reciprocity, elder satisfaction, and caregiver stress and burden: The exchange of aid in the family caregiving relationship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 35–43. 10.2307/352699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ejiogu N, Norbeck J, Mason M, Cromwell B, Zonderman Z, & Evans M (2011). Recruitment and retention strategies for minority or poor clinical research participants: Lessons from the healthy aging in neighborhoods of diversity across the life span study. The Gerontologist, 51(S1), S33–S45. 10.1093/geront/gnr027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps F (2014). The relationship between family obligation and religiosity on caregiving. Geriatric Nursing, 35, 126–131. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps F, Skemp L, & Specht JK (2016). How do we promote health?: From the words of African American older adults with dementia and their family members. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 9, 278–287. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20160928-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epps F, Rose KM, & Lopez RP (2019). Who’s your family?: African American caregivers of older adults with dementia. Research in Gerontological Nursing, 12, 20–26. 10.3928/19404921-20181212-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer CS, Passmore SR, Maietta RC, Petruzzelli J, Casper E, Brown NA, … Quinn C (2016). The symbolic value and limitations of racial concordance in minority research engagement. Qualitative Health Research, 26, 830–841. 10.1177/1049732315575708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher-Thompson D, Aréan P, Coon D, Menendez A, Takagi K, Haley W, … Szapocznik J (2000). Development and implementation of intervention strategies for culturally diverse caregiving populations In Handbook on Dementia Caregiving, 151–185. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen BR, Hodgson NA, Budhathoki C, & Gitlin LN (2018). Caregiver reactions to aggressive behaviors in persons with dementia in a diverse, community-dwelling sample. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 0733464818756999 10.1177/0733464818756999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hansen BR, Hodgson NA, & Gitlin LN (2019). African-American caregivers’ perspectives on aggressive behaviors in dementia. Dementia (London), 18, 3036–3058. 10.1177/1471301218765946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo GJ (2014). Religious coping, positive aspects of caregiving, and social support among Alzheimer’s disease caregivers. Clinical Gerontologist, 37, 368–385. 10.1080/07317115.2014.907588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton L, Franz CE, Yeo G, & Levkoff SE (2005). Conceptions of dementia in a multiethnic sample of family caregivers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53, 1405–1410. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53409.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Family Nursing Association (IFNA). (2018). IFNA Position Statement on Graduate Family Nursing Education. Retrieved from https://internationalfamilynursing.org/2018/06/28/graduate-family-nursing-education/

- Jones C, & Jablonski R (2014). “I don’t want to be a guinea pig”: Recruiting older African Americans. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40, 3–4. 10.3928/00989134-20140116-01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy B, Mathis C, & Woods A (2007). African Americans and their distrust of the health care system: Healthcare for diverse populations. Journal of Cultural Diversity, 14, 56–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight BG, & Sayegh P (2010). Cultural values and caregiving: The updated sociocultural stress and coping model. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 65B(Suppl 1), 5–13. 10.1093/geronb/gbp096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2013). Correlates of emotional support and negative interaction among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 1262–1290. 10.1177/0192513x12454655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLennon S (2018). Burden and finding meaning in African American caregivers for individuals with dementia. Innovation in Aging, 2(suppl_1), 391 10.1093/geroni/igy023.1457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MindMaple Softonics [Computer software]. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.mindmaple.com/

- Moss KO, Deutsch N, Hollen P, Rovnyak V, Williams I, Rose K (2018a). End-of-life plans for African American older adults with dementia. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. 35, 1314–1322. 10.1177/1049909118761094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss KO, Deutsch N, Hollen P, Rovnyak VG, Williams IC, & Rose K (2018b). Health-related quality of life and self-efficacy among African American dementia caregivers. Innovation in Aging, 2(Suppl_1), 390 10.1093/geroni/igy023.1455 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services. (2018). National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers: Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/259156/FinalReport.pdf.

- Roth DL, Fredman L, & Haley WE (2015). Informal caregiving and its impact on health: A reappraisal from population-based studies. The Gerontologist, 55, 309–319. 10.1093/geront/gnu177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson ZB, Parker M, Dye C, & Hepburn K (2016). Experiences and learning needs of African American family dementia caregivers. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 31, 492–501. 10.1177/1533317516628518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott CB, Clay OJ, Epps F, Cothran FA, & Williams IC (2018). Associations of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and memory loss and employment status with burden in African American and Caucasian family caregivers. Dementia (London). 10.1177/1471301218788147 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Skufca L AARP Family Caregiving Survey: Caregivers’ Reflections on Changing Roles. Washington DC: AARP Research, November 2017. 10.26419/res.00175.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama AJ, O’Donovan A, Lin J, Puterman E, Lazaro A, Chan J, … Epel E (2012). Does cellular aging relate to patterns of allostasis? An examination of basal and stress reactive HPA axis activity and telomere length. Physiololgoy and Behavior, 106, 40–45. 10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Känel R, Mausbach BT, Dimsdale JE, Mills PJ, Patterson TL, Ancoli-Israel S, … Grant I (2010). Problem behavior of dementia patients predicts low-grade hypercoagulability in spousal caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65, 1004–1011. 10.1093/gerona/glq073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites C (2009). Building on strengths: Intergenerational practice with African American families. Social work, 54, 278–287. 10.1093/sw/54.3.278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M, Meisel M, Williams J, & Morris J (2011). An interdisciplinary outreach model of African American recruitment for Alzheimer’s disease research. The Gerontologist, 51(Suppl 1), S134–S141. 10.1093/geront/gnq098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombe CL (2010). Superwoman schema: African American women’s views on stress, strength, and health. Quality Health Research, 20, 668–683. 10.1177/1049732310361892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods-Giscombe CL, Allen AM, Black AR, Steed TC, Li Y, & Lackey C (2019). The Giscombe superwoman schema questionnaire: Psychometric properties and associations with mental health and health behaviors in African American women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40, 672–681. 10.1080/01612840.2019.1584654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Reever KE, & Bach-Peterson J (1980). Relatives of the impaired elderly: Correlates of feelings of burden. The Gerontologist, 20, 649–655. 10.1093/geront/20.6.649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]