Abstract

Purpose of review:

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a progressive adult onset neurodegenerative disease. Abnormally phosphorylated forms of the microtuble-associated protein tau containing four repeat domains (4R-tau) aggregate in neurons. Additionally, increasing evidence suggests that secretion and uptake of fragments of abnormal 4R-tau may play a role in disease progression. This extracellular tau is a natural target for immunotherapy.

Recent findings:

Three monoclonal antibodies targeting extracellular tau are in clinical stages of development. ABBV-8E12 and BIIB092 were safe in Phase 1, but both Phase 2 studies recently failed futility analyses. UCB0107 recently reported (in abstract form) Phase 1 safety results, and a Phase 2 study is under consideration. Stem cell therapy and the infusion of plasma is also being explored clinically

Summary:

The likely role of extracellular tau in the progression of PSP makes tau a natural target for targeted immunotherapy. Clinical trials are still in early stages, and while tau immunotherapy has largely been shown to be safe, efficacy has yet to be demonstrated.

Keywords: PSP, Progressive Supranuclear palsy, Tau, Immunotherapy

Background / Introduction

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) was first described by Richardson in 1963, and named by Steele, Richardson and Olszewski in 1964, describing a small series of patients with adult-onset vertical gaze palsy, dysarthria, axial rigidity, parkinsonism, and dementia[1,2]. Among patients with atypical parkinsonism, those with PSP are the most common, with the prevalence of PSP estimated between 1.4–8.3 per 100,000 [3–5]. Since then, the disorder has been further characterized clinically [6] and pathologically[7], though effective therapies to improve prognosis or slow progression have remained elusive[8].

There is significant clinical heterogeneity in PSP, particularly at disease onset. The initially described Richardson syndrome captures only a subset of patients (24% in one series[9]; 54% in another[10]), limiting accurate diagnosis (70% and 69% of patients in the two series, respectively). The International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) PSP study group published revised criteria in 2017, highlighting 4 core clinical features: 1) oculomotor dysfunction (classically vertical supranuclear gaze palsy); 2) postural instability within 3 years; 3) akinesia; and 4) cognitive dysfunction [6]. Additional supportive clinical features include levodopa resistance, dysarthria, dysphagia, and photophobia. Imaging findings of midbrain atrophy or hypometabolism, or postsynaptic striatal dopaminergic degeneration are also supportive of the diagnosis. The predominant clinical presentation and supportive factors are used to characterize the diagnostic certainty and clinical “predominance type.”

Despite these robust revised clinical criteria, the gold standard for diagnosis of PSP remains neuropathologic examination [6]. On autopsy, patients exhibit intracerebral aggregation of the protein tau. Formal neuropathologic diagnosis requires aggregates in the form of neurofibrillary tangles and neuropil threads in at least 3 of the pallidum, subthalamic nucleus, substantia nigra, or pons, and at least 3 of the striatum, oculomotor complex, medulla, or dentate [11]. Neuropathologic features also include oligodendroglial coiled bodies (tau positive perinuclear fibers) and tufted astrocytes [12].

Tau

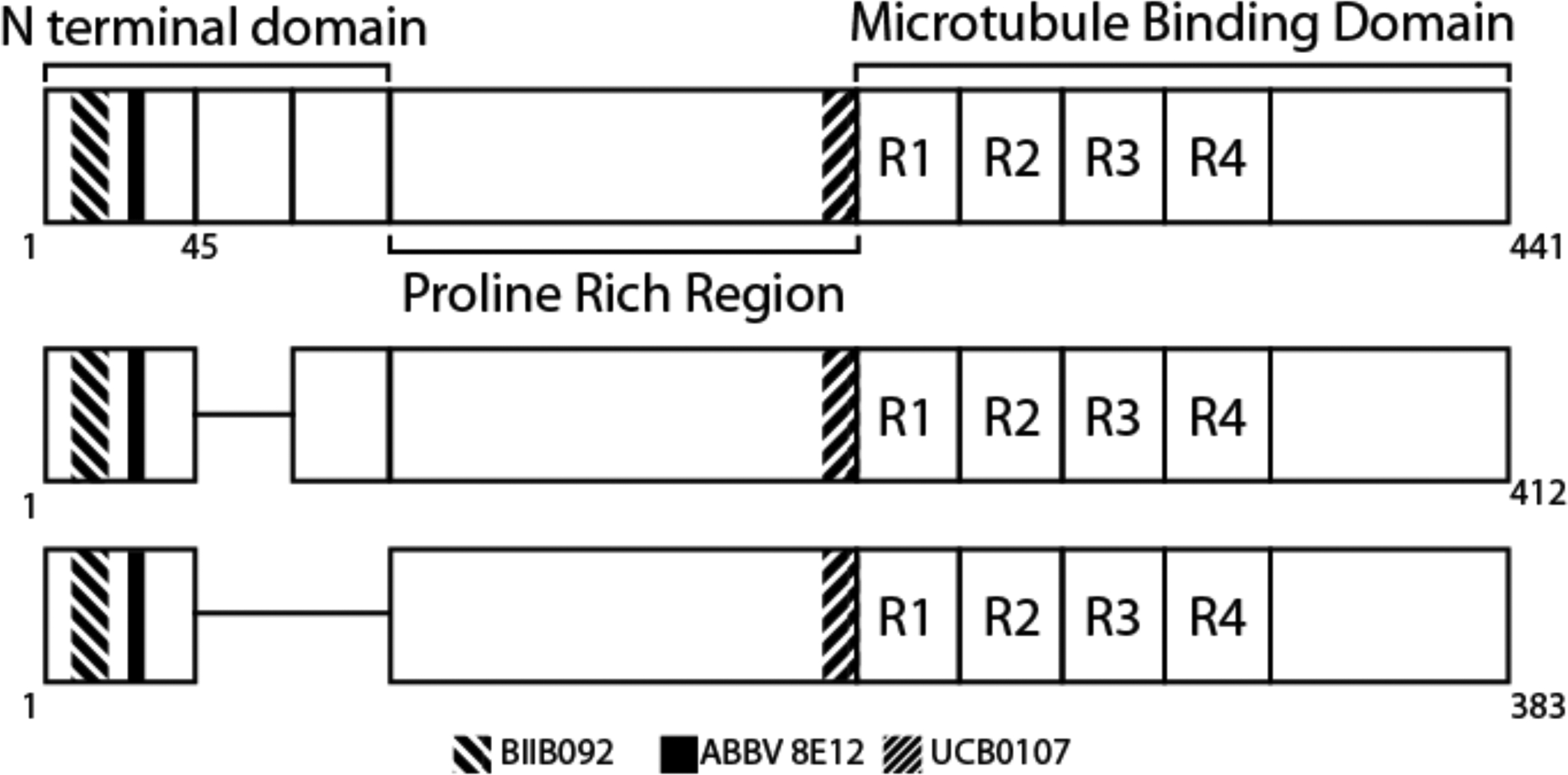

Tau is a microtubule associated protein involve in the polymerization and assembly of microtubules. It is encoded by the MAPT gene on chromosome 17. Alternative splicing of exons 2, 3, and 10 generate 6 isoforms, which differ in the number of insertions of a 29 amino acid sequence at the N-terminal end of the protein (0, 1, or 2 replicates) and the number of repeat domains (three, “3R”; or 4, “4R”) in the microtubule binding region (MBTR) (Figure 1). Patients with PSP demonstrate aggregations of the 4R but not the 3R isoform[7].

Figure 1:

PSP is characterized by aggregates of the 4R tau isoforms, so named because of inclusion of all four repeats in the microtubule binding domain. Monoclonal antibodies against tau are currently in clinical trials, each binding different epitopes of the protein.

A number of post-translational modifications create significant heterogeneity in the physiologic and likely also the pathologic tau proteome[13]. Hyperphosphorylation, truncation, nitration, glycation, glycosylation, and ubiquitination have all been described [13]. These post-translational modifications, particularly hyperphosphorylation, are likely responsible for the conversion of tau from its soluble to insoluble forms, where it aggregates, deposits, and causes neurodegeneration.

The exact mechanism of tau aggregation and propagation has not been fully established [14]. The propagation of abnormal tau has been proposed to correspond to clinical disease progression. There is mounting evidence in cellular and animal models for the secretion of tau fragments, so called “tau seeds”, from one cell to another, as well as for the ability of abnormal tau aggregates to induce the aggregation of non-aggregated tau, in a “prion-like” manner[14]. Ongoing work suggests that extracellular tau may play a role in the propagation of abnormal tau. The degree to which this mechanism contributes to human tauopathies is inherently difficult to assess.

The proposed role of secreted, extracellular tau in disease progression has made tau a natural target for immunotherapies as potentially disease modifying agents. In this review, we highlight recent updates in immunotherapy for the treatment of PSP. We focus on clinical trials and associated preclinical work using targeted immunotherapy strategies to reduce uptake and aggregation of tau as well as therapeutic strategies with broader immunomodulatory effect.

Immunotherapy in other neurodegenerative disorders, particularly Alzheimer disease, could have relevance for PSP; for a detailed discussion of tau immunotherapy in other conditions, see Novak et al[13]. Jadhav et al review the significant number of preclinical immunotherapies in development [15]. A broader discussion of therapies (including non-immunotherapies) in PSP is recently reviewed by Giagkou and Stamelou[16].

Immunotherapies currently in development

There are several strategies employed for immunotherapy in PSP and other tauopathies. Those in clinical trials are shown in Table 1 and discussed in detail below. These consist largely of monoclonal antibodies thought to target extracellular tau. It is unclear if antibodies would be able to enter neurons to target intracellular pathologic tau aggregates, pre-aggregate forms, or the aggregation process itself. Pre-clinical efforts targeting intracellular tau are ongoing, and other approaches include active vaccines [17,18] and antibodies that target tau-interacting partners[19]. Finally, other immunotherapies in early stages of development take a broader approach, engaging the innate immune system more generally [20].

Table 1:

Active or recently completed Immunotherapy Trials for PSP on Clinicaltrials.gov. PSPRS: PSP Rating Scale; FFP: Fresh Frozen Plasma.

| Compound (Alternate name) | Company/Sponsor | Number of Patients | Phase | NCT number | Primary Outcome measures | Status/Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABBV-8E12 (C2N-8E12, HJ8.5) |

AbbVie | Phase 2 Extension | NCT03391765 | Change in PSPRS, up to 5 years | Active, not recruiting | |

| 378 | Phase 2 | NCT02985879 | Change in PSPRS, up to 1 year; Adverse events | Active, not recruiting | ||

| Expanded Access | NCT03744546 | Active, not recruiting | ||||

| Phase 1 Extension | NCT03413319 | Adverse events | Active, not recruiting | |||

| 30 | Phase 1 | NCT02494024 | Safety and Tolerability | Completed | ||

| BIIB092 (BMS-986168, IPN007) |

Biogen | 490 | Phase 2 | NCT03068468 | Change in PSPRS, at 1 year; Adverse events | Active, not recruiting |

| Phase 1 Extension | NCT02658916 | Adverse events; Change in lab abnormalities, vital signs, ECGs, and physical exams | Active, not recruiting |

|||

| 48 | Phase 1 | NCT02460094 | Safety and Tolerability | Completed | ||

| UCB0107 (Antibody D) |

UCB Biopharma | 52 healthy males | Phase 1 | NCT03464227 | Adverse events | Completed |

| Autologous Bone Marrow Derived Stem Cells | MD Stem Cells | 300** | Not applicable | NCT02795052 | Activities of Daily Living, up to 1 year | Recruiting |

| FFP | University of California, San Francisco | 6 | Phase 1 | NCT02460731 | Drug limiting toxicity | Active, not recruiting |

This study is not recruiting patients exclusively with PSP, but rather a wide range of conditions

ABBV-8E12

ABBV-8E12 is a humanized murine monoclonal antibody that binds amino acids 25–30 near the N-terminus of tau (Figure 1). In vitro studies demonstrated the ability to block the uptake of tau aggregates into human and mouse neurons [21,22]. In vivo studies in human-tau transgenic mice showed that delivery of the antibody into the CSF or the peritoneum reduced levels of insoluble tau and reduced brain atrophy [22,23]. CSF delivery also rescued behavioral deficits in an associative learning task[22].

Based on these preclinical data, a phase 1 study was completed in 30 patients with possible or probable PSP [24]. 23 subjects were treated with a single ascending dose ranging from 2.5 mg/kg to 50 mg/kg with follow-up for 84 days; the remaining 7 subjects received placebo. Notably, patients had relatively early disease, with less than 5 years of symptoms and with the ability to walk 5 steps with minimal assistance. While adverse events occurred in 70% of the participants, the majority were rated by the blinded investigators to be mild to moderate and largely felt to be unrelated to the therapy.

A Phase 2 randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial in PSP (and separately, Alzheimer disease) recruited 378 patients with early PSP who received one of two doses or placebo every 4 weeks for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was change in PSP rating scale (PSPRS) at one year (Table 1), but this study was halted in July 2019 after it failed a futility analysis[25]. The details of this analysis have not been made public at the time of this writing but will be presented at the Tau2020 Global Conference in February, 2020. The Phase 2 trial in patients with Alzheimer disease is ongoing.

BIIB092

BIIB092 is a humanized murine monoclonal antibody that binds the amino acids 15–24 near the N-terminus of tau, immediately adjacent to the ABBV-8E12 epitope (Figure 1). Preclinical studies in vitro suggested that extracellular tau seeds are composed of predominantly N-terminal fragments of tau [26]. An early version of the antibody was shown to bind extracellular, but not intracellular, tau and to reduce the levels of tau fragments in the interstitial fluid and CSF [26].

A Phase 1 study was first completed in 65 healthy, relatively young (mean age 44) participants who each received a single IV infusion of BIIB092 in one of 6 doses (up to 4200 mg) to assess for safety. In general, adverse events were mild. As evidence of target engagement, CSF N-terminal tau levels were found to be suppressed in this healthy population, with 82–95% suppression after 85 days [27].

A subsequent Phase 1b study was conducted in 48 patients with probable or possible PSP, in early stages of the disease - with fewer than 5 years of symptoms and able to ambulate independently or with assistance [28]. One of 3 doses (150, 700, 2100mg) or placebo was administered intravenously every 4 weeks for 3 doses. The primary outcome was safety: 75% of patients reported an adverse event, which were largely mild and felt to be unrelated to the study drug. The CSF concentration of free N-terminal tau was reduced by 90% compared to placebo. Exploratory outcomes, including clinical rating scales (PSPRS and others) and brain volume, did not demonstrate a significant effect in this small study. An open-label extension study in 47 of these participants is ongoing.

A Phase 2 randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study in a similar population of patients with early PSP (and, separately, in Alzheimer disease) with primary clinical and safety outcomes completed enrollment of approximately 490 patients. The study was completed in December 2019 – BIIB092 did not show efficacy on the primary endpoint (change in PSPRS at 1 year) or secondary endpoints, according to a press release from the company[29]. The Phase 2 trial in patients with mild Alzheimer disease is ongoing.

UCB0107

UCB0107 is a humanized murine monoclonal antibody targeting a central tau epitope adjacent to the microtubule-binding repeats (Figure 1). Preclinical work identified antibodies that suppressed tau aggregation in an in vitro model and suggested that a central tau epitope antibody more strongly suppressed tau seeding (using human Alzheimer disease brain homogenate) and propagation than antibodies with N-terminal epitopes [30,31].

In a Phase 1 trial (reported in abstract form), 52 healthy male adults received intravenous UCB0107 or placebo. Adverse events occurred in 47% of subjects; none were serious or related to the therapy [32]. A Phase 2 trial is currently being planned, though it is not specified whether Alzheimer disease, PSP, or another tauopathy will be included.

Stem Cell Therapy

Bone marrow derived mesenchymal stromal or stem cells (MSCs) have been proposed as immunomodulatory therapy for a number of neurologic conditions, though as yet have not shown efficacy in neurodegenerative disorders. In animal models of Parkinson and Alzheimer disease, MSCs from bone marrow or other sources, or media derived from MSCs, have been suggested to reduce neural cell loss by inhibiting apoptosis[33], enhancing neurogenesis[34], modulating autophagy and enhance clearance of synuclein and amyloid[35,36], reducing hyperphosphorylated tau [37], and modulating neuroinflammation[38,39], in some cases with improvement on learning tasks[34,37,39,40] (for recent reviews see [41,42]).

A small Phase 1 study was completed in which 5 patients with PSP received autologous MSCs administered into the internal carotid and basilar arteries [43]. Patients had an average disease duration of 6 years, typically with severe disability but able to stand unassisted. Some microembolization was reported as a consequence of the intraarterial MSC delivery. The study was not designed to assess efficacy, however some patients reported mild subjective improvement and 4 of the patients were alive 1 year after treatment, compared to 24% of patients in a historical cohort followed by the authors.

There is one active study of intravenous and intranasal administration of autologous bone-marrow derived MSCs in PSP, in an open-label, non-randomized study (NCT02795052, Table 1). However, this study is generally recruiting patients with a wide variety of neurologic disorders with coarse outcome measures (ADLs); and substantial ethical and safety concerns have been raised [44,45].

Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFP)

Preclinical data has suggested that the transfusion of plasma from young mice improved performance in learning and memory tests when administered to a mouse model of Alzheimer disease[46]. Based on these preclinical studies, a phase 1 trial in 18 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease was conducted [47]. They received 1 unit of FFP from young male donors weekly for 4 weeks. The primary outcome was adverse events. One patient discontinued therapy due to urticaria. Adverse events were mild to moderate, and no serious adverse events were attributed to the therapy. The study was not powered to assess clinical benefit; subjective improvement in functional ability was reported by caregivers.

There is one active open-label, non-randomized study of transfusion of FFP from young, male donors in PSP (Table 1).

Notably, due to reports of for-profit commercial use of this therapy making unproven safety and efficacy claims, the FDA issued a statement warning the public of the risks of plasma from young donors outside of FDA reviewed clinical studies [48].

Discussion

The extracellular availability of tau, and the potential role of extracellular tau in the progression of the disease, makes the protein a natural target for immunotherapy. However, clinical trials are still in early stages, and, while these therapies have largely been shown to be safe, their efficacy has yet to be demonstrated.

Developing tau immunotherapy for PSP poses several challenges, including the lack of uniform preclinical models and the complex pathogenesis of tauopathies. Various in vitro and in vivo models are used, there is variability in how antibody response is quantified and reported, and outcome measures are diverse (neuronal loss, inflammatory response, performance on motor or learning tasks)[15]. Additionally, the optimal target epitope of the tau protein is unknown. The N-terminal region has been attractive due to its hypothesized role in tau seeding; other studies suggest targeting the MBTR[49]. The ideal mechanism of action to target is also unclear. Tau plays both an intracellular and extracellular role in the normal and abnormal cell. Tau antibodies in PSP thus far have targeted tau seeding; but this may represent an early event in pathogenesis that is no longer amenable to intervention by the time patients have established disease. Reduction of overall levels of tau or 4R-tau as well as reduction of tau phosphorylation, secretion, uptake, and aggregation via immunotherapy are also being explored. Additionally, glial tau represents a potential therapeutic target. Microglia play a role in tau processing and clearance, and tau pathology is also present in astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. Impaired clearance of tau by microglia, reactive gliosis due to tau pathology, and impairment in the ability of glia to maintain homeostasis resulting in neuronal loss likely contribute to disease progression – further understanding of these mechanisms will also guide future therapies[50–52].

Beyond the above preclinical challenges, clinical trials are constrained by the absence of a reliable biomarker and the clinical heterogeneity of disease. Classic PSP-RS (Richardson syndrome) accounts for the plurality but potentially not the majority of cases[9,10], and the rate of progression is different among different clinical phenotypes [8,9]. The ideal study population is unclear, and there are complex trade-offs. For example, a larger number of study subjects and longer duration of follow up may improve statistical power but comes at a financial cost, prioritizing phenotypic homogeneity may increase the likelihood of observing a therapeutic effect but does not reflect the diversity of the disease, and enrolling early stage patients who may be most responsive to therapy reduces diagnostic certainty. Currently, neuropathology at autopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis, though novel imaging techniques are being explored [53]. Volume loss on imaging is evident with disease progression, at least in PSP-RS[54], and so may be a valuable biomarker in assessing potential sub-clinical, early benefit of therapies across different clinical phenotypes. However, volume loss on MRI can be seen well before patients fulfill criteria for PSP, and so ongoing efforts towards early diagnosis will likely be necessary to improve therapeutic outcomes.

Finally, tau immunotherapy is not restricted to PSP. Several monoclonal antibodies and 2 vaccines are in clinical stages of development in Alzheimer disease[13], a mixed 3R/4R secondary tauopathy. While it is not yet clear if a therapy for one tauopathy will translate into a therapy for another, there are likely lessons to be learned from other immunotherapy trials.

Conclusion

Tau immunotherapy, and immunotherapy in general, is an exciting and active area of study for the treatment of Progressive Supranuclear Palsy. While there are challenges in the selection of therapies and design of trials, several agents are in clinical stages of development.

Key points:

Progressive supranuclear palsy is a rapidly progressive neurodegenerative disease, characterized by a clinically diverse population of patients. Classical symptoms include supranuclear vertical gaze palsy, dysarthria, axial rigidity, parkinsonism, and dementia.

Aggregates of 4R-tau in astrocytic tufts, neurofibrillary tangles, and neuropil threads are the pathologic hallmarks of the disease

Immunotherapies, largely consisting of monoclonal antibodies targeting extracellular tau, are hypothesized to disrupt transmission of abnormal tau from cell to cell.

Three monoclonal antibodies are in clinical stages of development: ABBV-8E12 and BIIB092 have recently failed a futility analyses, and UCB0107 has completed Phase 1 studies with a Phase 2 trial under consideration.

Financial Support and sponsorship:

Pavan A Vaswani: None

Abby L Olsen: None directly pertinent to this review; Grant support from NINDS K08 NS109344-01 and Department of Defense Parkinson’s Disease Early Investigator Award W81XWH-18-1-0395

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest:

Pavan A Vaswani: None

Abby L Olsen: None

References

- 1.RICHARDSON JC, STEELE J, OLSZEWSKI J. SUPRANUCLEAR OPHTHALMOPLEGIA, PSEUDOBULBAR PALSY, NUCHAL DYSTONIA AND DEMENTIA. A CLINICAL REPORT ON EIGHT CASES OF “HETEROGENOUS SYSTEM DEGENERATION”. Trans Am Neurol Assoc 1963; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * Original case series of patients with Richardson syndrome, now called PSP-RS

- 2.Steele JC, Richardson JC, Olszewski J. Progressive supranuclear palsy. Arch Neurol 1964;10:333–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * Early case series of 9 patients where the name Progressive Supranuclear Palsy was coined

- 3.Golbe LI, Davis PH, Schoenberg BS, Duvoisin RC. Prevalence and natural history of progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology 1988;38(7):1031–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Quinn NP. Prevalence of progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy: A cross-sectional study. Lancet 1999;354(9192):1771–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fleury V, Brindel P, Nicastro N, Burkhard PR. Descriptive epidemiology of parkinsonism in the Canton of Geneva, Switzerland. Park Relat Disord 2018;54:30–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Höglinger GU, Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Josephs KA, Lang AE, et al. Clinical diagnosis of progressive supranuclear palsy: The movement disorder society criteria. Mov Disord 2017;32(6):853–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This systematic review, case series, and consensus describes inclusion and exclusion criteria and supportive features for the clinical diagnosis of PSP. It also describes the clinical phenotypes and gives criteria for diagnostic certainty.

- 7.Kovacs GG. Invited review: Neuropathology of tauopathies: Principles and practice. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2015;41(1):3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This review discusses our current knowledge of the neuropathology of the tauopathies, including PSP and Alzheimer disease

- 8.Armstrong MJ. Progressive Supranuclear Palsy: an Update. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep 2018;18(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This review summaries our knowledge about the clinical phenotype, course, diagnostics, and therapies in PSP

- 9.Respondek G, Stamelou M, Kurz C, Ferguson LW, Rajput A, Chiu WZ, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of progressive supranuclear palsy: A retrospective multicenter study of 100 definite cases. Mov Disord 2014;29(14):1758–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study describes the phenotypes observed in patients with PSP, which formed the basis, in part, for the 2017 MDS clinical diagostic criteria

- 10.Williams DR, De Silva R, Paviour DC, Pittman A, Watt HC, Kilford L, et al. Characteristics of two distinct clinical phenotypes in pathologically proven progressive supranuclear palsy: Richardson’s syndrome and PSP-parkinsonism. Brain 2005;128(6):1247–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litvan I, Hauw JJ, Bartko JJ, Lantos PL, Daniel SE, Horoupian DS, et al. Validity and reliability of the preliminary NINDS neuropatohlogic criteria for progressive supranuclear palsy and related disorders. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This case series described the clinical syndrome of PSP and formulated the diagnostic criteria, until 2017. The criteria in this work were used for the diagnosis of the majority of cases in the clinical trials discussed.

- 12.Dickson DW, Ahmed Z, Algom AA, Tsuboi Y, Josephs KA. Neuropathology of variants of progressive supranuclear palsy. Curr. Opin. Neurol 2010;23(4):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This review describes the pathology of PSP and its clinical variants

- 13.Novak P, Kontsekova E, Zilka N, Novak M. Ten years of tau-targeted immunotherapy: The path walked and the roads ahead. Front Neurosci 2018;12(NOV):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** Excellent review summarizing the state of tau immunotherapy in general, with a focus on future directions for the treatment of the tauopathies

- 14.Mudher A, Colin M, Dujardin S, Medina M, Dewachter I, Alavi Naini SM, et al. What is the evidence that tau pathology spreads through prion-like propagation? Acta Neuropathol Commun 2017;5(1):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This review summaries current knowledge regarding tau seeding and propagation

- 15.Jadhav S, Avila J, Schöll M, Kovacs GG, Kövari E, Skrabana R, et al. A walk through tau therapeutic strategies. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7(1):22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This review summaries the physiologic and pathologic role of tau, possible mechanisms of tau therapeutics, and highlights the immunotherapies in preclinical development.

- 16.Giagkou N, Stamelou M. Emerging drugs for progressive supranuclear palsy. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 2019;24(2):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This review highlights the therapies for PSP in clinical stages of development, including symptomatic and potential disease-modified therapies

- 17.Hovakimyan A, Antonyan T, Shabestari SK, Svystun O, Chailyan G, Coburn MA, et al. A MultiTEP platform-based epitope vaccine targeting the phosphatase activating domain (PAD) of tau: therapeutic efficacy in PS19 mice. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joly-Amado A, Davtyan H, Serraneau K, Jules P, Zitnyar A, Pressman E, et al. Active immunization with tau epitope in a mouse model of tauopathy induced strong antibody response together with improvement in short memory and pSer396-tau pathology. Neurobiol Dis 2020;134(May 2019):104636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomas S, Hoxha K, Tran A, Prendergast GC. Bin1 antibody lowers the expression of phosphorylated Tau in Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Biochem 2019;120(10):18320–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenzweig N, Dvir-Szternfeld R, Tsitsou-Kampeli A, Keren-Shaul H, Ben-Yehuda H, Weill-Raynal P, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade harnesses monocyte-derived macrophages to combat cognitive impairment in a tauopathy mouse model. Nat Commun 2019;10(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmes BB, Furman JL, Mahan TE, Yamasaki TR, Mirbaha H, Eades WC, et al. Proteopathic tau seeding predicts tauopathy in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(41):E4376–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanamandra K, Kfoury N, Jiang H, Mahan TE, Ma S, Maloney SE, et al. Anti-tau antibodies that block tau aggregate seeding invitro markedly decrease pathology and improve cognition in vivo. Neuron 2013;80(2):402–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the preclinical data for ABBV8E12 (HJ8.5) noting that injection into the CSF reduces the presence of tau aggregates and has a behavioral effect

- 23.Yanamandra K, Jiang H, Mahan TE, Maloney SE, Wozniak DF, Diamond MI, et al. Anti-tau antibody reduces insoluble tau and decreases brain atrophy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2015; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This pre-clinical study of ABBV-8E12 (HJ8.5) demonstrates that intraperitoneal injection decreases tau aggregates and may have a clinical effect in P301S mice

- 24.West T, Hu Y, Verghese PB, Bateman RJ, Braunstein JB, Fogelman I, et al. Preclinical and Clinical Development of ABBV-8E12, a Humanized Anti-Tau Antibody, for Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Tauopathies. J Prev Alzheimer’s Dis 2017;4(4):236–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the results of the Phase 1 study of ABBV-8E12 in 30 paitents with PSP

- 25.AbbVie’s Tau Antibody Flops in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy | ALZFORUM [Internet]. AlzForum; 2019. [cited 2020 Feb 4];Available from: https://www.alzforum.org/news/research-news/abbvies-tau-antibody-flops-progressive-supranuclear-palsy [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bright J, Hussain S, Dang V, Wright S, Cooper B, Byun T, et al. Human secreted tau increases amyloid-beta production. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36(2):693–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qureshi IA, Tirucherai G, Ahlijanian MK, Kolaitis G, Bechtold C, Grundman M. A randomized, single ascending dose study of intravenous BIIB092 in healthy participants. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv 2018;4:746–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the result of the Phase 1 trial of BIIB092 in 65 healthy participants

- 28.Boxer AL, Qureshi I, Ahlijanian M, Grundman M, Golbe LI, Litvan I, et al. Safety of the tau-directed monoclonal antibody BIIB092 in progressive supranuclear palsy: a randomised, placebo-controlled, multiple ascending dose phase 1b trial. Lancet Neurol 2019;18(6):549–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the results of the Phase 1b trial of BIIB092 in 48 patients with PSP

- 29.Biogen Reports Top-Line Results from Phase 2 Study in Progressive Supranuclear Palsy | Biogen [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 15];Available from: http://investors.biogen.com/news-releases/news-release-details/biogen-reports-top-line-results-phase-2-study-progressive

- 30.Albert M, Mairet-Coello G, Danis C, Lieger S, Caillierez R, Carrier S, et al. Prevention of tau seeding and propagation by immunotherapy with a central tau epitope antibody. Brain 2019;142(6):1736–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This preclinical study of UCB0107 suggests that an antibody targetting the mid-region of tau may be more effective at reducing tau pathology than antibodies with N-terminal targets

- 31.Courade JP, Angers R, Mairet-Coello G, Pacico N, Tyson K, Lightwood D, et al. Epitope determines efficacy of therapeutic anti-Tau antibodies in a functional assay with human Alzheimer Tau. Acta Neuropathol 2018;136(5):729–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Buchanan T, De Bruyn S, Fadini T, Watanabe S, Germani M, Mesa ABIR, et al. A randomised, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study with a central Tau epitope antibody – UCB0107. Int Congr Park Dis Mov Disord Nice, Fr Sept 22–26, 2019 - Late Break Abstr 2019; [Google Scholar]; * This late-breaking conference abstract at MDS 2019 reports the Phase 1 results for UCB0107

- 33.Cova L, Bossolasco P, Armentero MT, Diana V, Zennaro E, Mellone M, et al. Neuroprotective effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on neural cultures exposed to 6-hydroxydopamine: Implications for reparative therapy in Parkinson’s disease. Apoptosis 2012;17(3):289–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reza-Zaldivar EE, Hernández-Sapiéns MA, Gutiérrez-Mercado YK, Sandoval-Ávila S, Gomez-Pinedo U, Márquez-Aguirre AL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes promote neurogenesis and cognitive function recovery in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural Regen Res 2019;14(9):1626–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Park HJ, Shin JY, Kim HN, Oh SH, Lee PH. Neuroprotective effects of mesenchymal stem cells through autophagy modulation in a parkinsonian model. Neurobiol Aging 2014;35(8):1920–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin JY, Park HJ, Kim HN, Oh SH, Bae JS, Ha HJ, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells enhance autophagy and increase β-amyloid clearance in Alzheimer disease models. Autophagy 2014;10(1):32–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HJ, Lee JK, Lee H, Carter JE, Chang JW, Oh W, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells improve neuropathology and cognitive impairment in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model through modulation of neuroinflammation. Neurobiol Aging 2012;33(3):588–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lykhmus O, Koval L, Voytenko L, Uspenska K, Komisarenko S, Deryabina O, et al. Intravenously injected mesenchymal stem cells penetrate the brain and treat inflammation-induced brain damage and memory impairment in mice. Front Pharmacol 2019;10(MAR). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mehrabadi S, Motevaseli E, Sadr SS, Moradbeygi K. Hypoxic-Conditioned Medium from Adipose Tissue Mesenchymal Stem Cells Improved Neuroinflammation through Alternation of Toll like receptor (TLR) 2 and TLR4 Expression in Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Rats. Behav Brain Res 2019;379(September 2019):112362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mendes-Pinheiro B, Anjo SI, Manadas B, Da Silva JD, Marote A, Behie LA, et al. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cells’ Secretome Exerts Neuroprotective Effects in a Parkinson’s Disease Rat Model. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019;7(November):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakari-Khiavi F, Dolati S, Chakari-Khiavi A, Abbaszadeh H, Aghebati-Maleki L, Pourlak T, et al. Prospects for the application of mesenchymal stem cells in Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Life Sci 2019;231(June). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Staff NP, Jones DT, Singer W. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapies for Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):892–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Canesi M, Giordano R, Lazzari L, Isalberti M, Isaias IU, Benti R, et al. Finding a new therapeutic approach for no-option Parkinsonisms: Mesenchymal stromal cells for progressive supranuclear palsy. J Transl Med 2016;14(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the results for the Phase 1 study of infusion of mesenchymal stromal cells into the cerebral vasculature.

- 44.Sipp D, Robey PG, Turner L. Clear up this stem-cell mess. Nature 2018;561(7724):8–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner L The US direct-to-consumer marketplace for autologous stem cell interventions. Perspect Biol Med 2018;61(1):7–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Middeldorp J, Lehallier B, Villeda SA, Miedema SSM, Evans E, Czirr E, et al. Preclinical assessment of young blood plasma for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol 2016;73(11):1325–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sha SJ, Deutsch GK, Tian L, Richardson K, Coburn M, Gaudioso JL, et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Feasibility of Young Plasma Infusion in the Plasma for Alzheimer Symptom Amelioration Study: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2019;76(1):35–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; * This study reports the results of a Phase 1 trial of the infusion of FFP from young male donors in patients with Alzheimer disease

- 48.Statement from FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., and Director of FDA’s Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Peter Marks, M.D., Ph.D., cautioning consumers against receiving young donor plasma infusions that are promoted as unproven treatment [Internet]. [cited 2019 Dec 2];Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/statement-fda-commissioner-scott-gottlieb-md-and-director-fdas-center-biologics-evaluation-and-0

- 49.Weisová P, Cehlár O, Škrabana R, Žilková M, Filipčík P, Kováčech B, et al. Therapeutic antibody targeting microtubule-binding domain prevents neuronal internalization of extracellular tau via masking neuron surface proteoglycans. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2019;7(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kahlson MA, Colodner KJ. Glial tau pathology in tauopathies: Functional consequences. J Exp Neurosci 2015;9s2:43–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perea JR, Llorens-Martín M, Ávila J, Bolós M. The role of microglia in the spread of Tau: Relevance for tauopathies. Front Cell Neurosci 2018;12(July):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leyns CEG, Holtzman DM. Glial contributions to neurodegeneration in tauopathies. Mol Neurodegener 2017;12(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This review summaries our current understanding of the role of glia in the tauopathies, including the role they play in the spread of tau as well as the indirect ways tau may affect the inflammatory response and neuronal homeostasis

- 53.Whitwell JL, Höglinger GU, Antonini A, Bordelon Y, Boxer AL, Colosimo C, et al. Radiological biomarkers for diagnosis in PSP: Where are we and where do we need to be? Mov Disord 2017;32(7):955–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ** This systematic review summarizes the current understanding of neuroimaging in PSP.

- 54.Dutt S, Binney RJ, Heuer HW, Luong P, Attygalle S, Bhatt P, et al. Progression of brain atrophy in PSP and CBS over 6 months and 1 year. Neurology 2016;87(19):2016–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]