Abstract

Racial microaggressions are common experiences for students of color on college campuses. Given prior research connecting microaggressions to negative mental health outcomes, it is important to better understand the social context and process through which microaggressions are associated with poorer mental health. In addition, we put forth a psycho-sociological approach to microaggressions, integrating an attention to both individual psychology and broader social structure. Specifically, the present study investigated whether the indirect association of school/workplace microaggressions and internalizing symptoms (i.e., depression, anxiety, and stress) through problem-focused thoughts (a subset of ruminative thinking) differed as a function of horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism among a racially diverse sample of non-White college students (n = 549) from two universities in the United States. As hypothesized, problem-focused thoughts mediated the associations between school/workplace microaggressions and all three negative mental health symptoms. Further, the indirect effect of school/workplace microaggressions on psychological health through problem-focused thoughts was stronger in students with high levels of vertical individualism (i.e., autonomous but recognize/accept inequality among individuals), compared to students with low or average levels. Our findings suggest that students of color who endorse vertical individualism are at a relatively greater risk of negative mental health outcomes related to school/workplace microaggressions via problem-focused thoughts. Future research is needed to examine additional factors that may buffer or strengthen the pathways between microaggressions and negative mental health in students of color.

Keywords: Microaggressions, rumination, internalizing symptoms, individualism, collectivism

Introduction

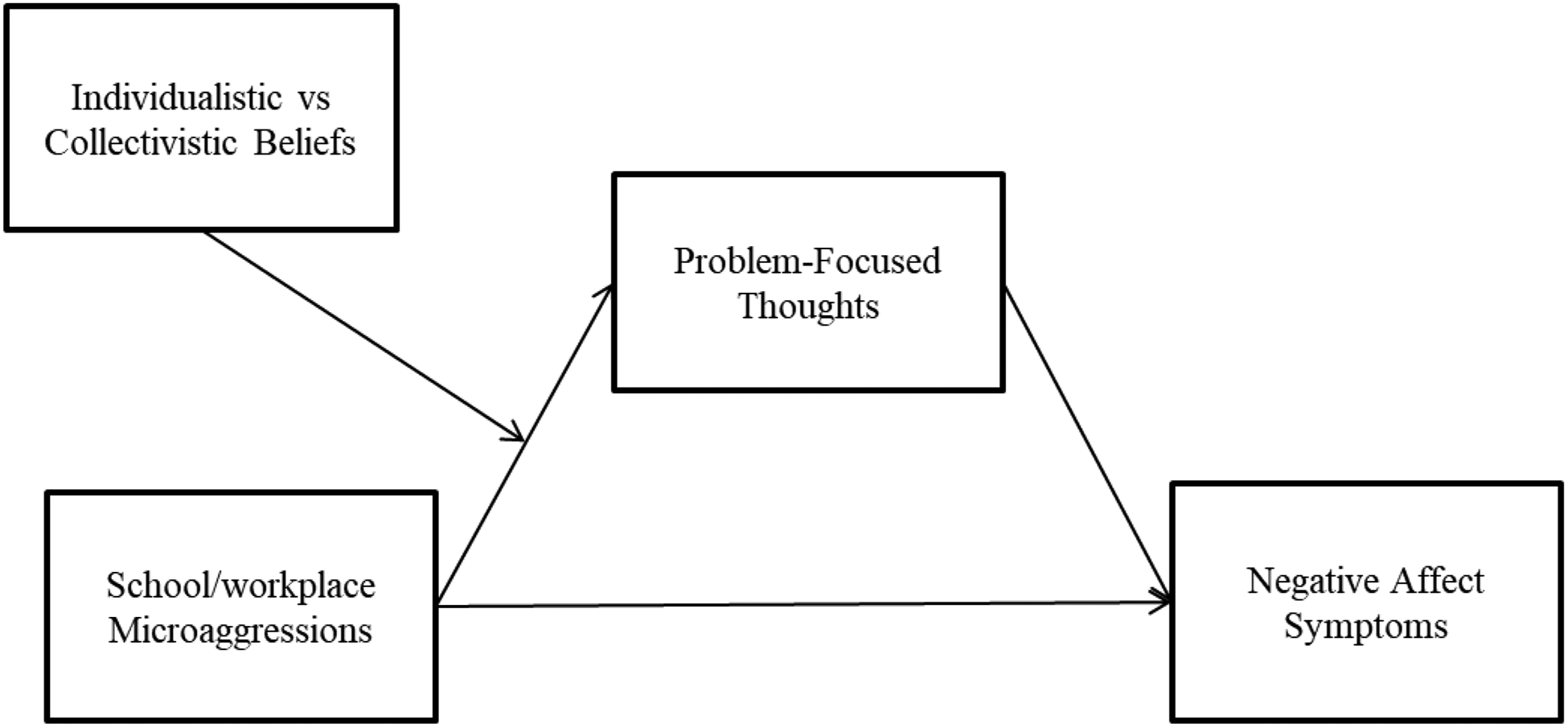

In a post-Civil Rights era, racism in the United States manifests on multiple levels, with various social and psychological impacts. While systemic racism, such as segregation, involves direct acts of discrimination [1], scholars have turned their attention toward microaggressions, or more subtle abuses based on race/ethnicity [2, 3], gender [4–7], sexual orientation [8, 9], religion [10, 11], or the intersections of societally marginalized identities [8, 12–14]. While research on racial/ethnic microaggressions has grown substantially across a variety of fields [15, 16], to date there are few interdisciplinary approaches toward examining the impact microaggressions have on mental health outcomes. This article puts forth a psycho-sociological approach (see Figure 1) to racial/ethnic microaggressions, integrating an attention to both individual psychology (i.e., ruminative thinking) and broader social structure (individualistic vs. collectivistic beliefs) as possible risk factors that link (i.e., mediate) and strengthen (i.e., moderate) the associations between racial/ethnic microaggressions and poorer mental health outcomes among college students. The approach affords us a more nuanced understanding about the structural origins and individual experiences related to microaggressions, informing future social policy, psychological practices, and institutional reforms among colleges.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of proposed moderated-meditational models.

Overview of Microaggressions in College Settings

Microaggressions consist of particularly insidious expressions of bias, acts of discrimination, and environmental signals of systems of power and oppression that elicit feelings of anger, shame, and disillusionment in targeted individuals while reinforcing feelings of superiority among the members of dominant groups [2]. The three overlapping subcategories of microaggressions are microinvalidations, microinsults, and microassaults [17]. Microinvalidations involve behaviors that negate the experiences, thoughts, and feelings of marginalized group members or denials of the existence of interpersonal or systemic oppression (e.g., endorsement of colorblind racial ideology). Microinsults include statements or actions that demonstrate ignorance, unawareness, or cultural ignorance (e.g., a back-handed compliment). Most blatant are microassaults, or behaviors aimed at inciting harm (e.g., using pejoratives). The intentionality behind a behavior is tangential to the classification of an act as a microaggression; regardless of how purposive the act, microaggressions have the potential to incite acute distress in targeted individuals [17].

Microaggressions are multilayered; they are instances of “everyday racism” [18], or daily experiences of discrimination demonstrating invalidation, insensitivity, or ignorance embedded in broader systems of power and oppression. On the one hand, microaggressions are deeply rooted in institutional settings, embedded in broader systems of power and oppression. Yet on the other hand, microaggressions are interpersonal in nature and manifest cumulatively for individuals sustaining the experiences on both psychological and physiological levels. Specific to racial/ethnic microaggressions, these types of microaggressions are inherently personal and interactional, and simultaneously rooted in hierarchical social structures [2, 15, 16, 19–22]. Microaggressions can occur across a variety of institutional settings, including health care [14, 23, 24], schools [3, 21, 25], workplaces [26, 27], and public spaces such as grocery stores or public transportation settings [28]. However, some evidence has shown that microaggressions experienced in college settings may be particularly harmful to college students of color [29].

Scholarship about microaggressions in schools and higher education settings is so far understudied [30]. Research has begun to analyze how collegiate environments are structured by race and racism in “micro-level forms” [15, p. 63]. For instance, in-depth interviews with Black males demonstrated how they are stereotyped as targets of hyper-surveillance on elite White research campuses [31]. Further, research has demonstrated that microaggressions occur regularly on university campuses, with a survey finding that students of color experience on average more than three racial or ethnic microaggressions per day [32]. Important psychological [21] and academic [25] consequences of racial microaggressions in educational settings have been well-documented (see Yosso et al. [3] and Ogunyemi et al. [33] for reviews). Building on this research, our article illuminates how the meso, institutional setting of schools/workplaces generates interpersonal interactions that are harmful for the mental health of students of color. Following Embrick and colleagues’ [19] interdisciplinary approach to microaggressions, we illuminate individual psychological outcomes within the context of broader systems that uphold racism in everyday social interactions, particularly in the school/work setting.

Microaggressions and Psychological Health Outcomes among College Students

Research has addressed the immense impacts of experiencing racial microaggressions on psychological health and wellbeing among college students. Experiences of racial microaggressions have been connected to drug use [34] and problematic alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences [32, 35] among college students of color. Anxiety [32, 36], stress [33, 36], depressive symptoms [21, 37], general psychological distress [38, 39], as well as suicidal ideation [37] have also been found to correlate positively with reported experiences of racial microaggressions. A recent survey of university students of color found depression and perceived stress to mediate the relationship between racial microaggressions and somatic symptoms [40]. Additionally, problem-focused coping has been established as a mediator of the association between racial microaggressions on university campuses and mental health outcomes [41]. However, less understood is the interplay of both individual psychology (i.e., ruminative thinking) and broader social structure (individualistic vs. collectivistic beliefs) impacting the associations between racial/ethnic microaggressions and poorer mental health outcomes among college students.

Ruminative Thinking as a Mediator

Rumination refers to a style of thinking that involves a wide-ranging inclination to “think repetitively, recurrently, uncontrollably, and intrusively,” often about identifiable stressors [42, p. 4]. Rumination as a cognitive disposition has been associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression [43], and evidence suggests that ruminative thinking is a key component of major depressive disorder [44]. Further, rumination has been found to mediate the effects of perceived chronic stress on depression, anxiety, and poor sleep quality [45]. Numerous models have proposed that experiences of racial discrimination and social stigma constitute chronic stressors that culminate in racial health disparities for those who identify as people of color or multiracial [16, 46, 47]. Further, prior research has identified rumination as a mediator of the association between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial and ethnic minorities [48] as well as a mediator of the associations between perceived discrimination and depressive and anxiety symptoms among sexual minorities [49]. Building on this research, the present study examines the indirect effects of microaggressions—a facet of perceived discrimination—as chronic stressors on psychological outcomes (i.e., depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and stress symptoms) through ruminative thinking. Ruminative thoughts have been found to mediate the associations between microaggressions and more negative psychological health in samples of sexual [50] and gender minorities [51], as well as African Americans [52], but the present study extends prior findings by examining rumination as a mediator between racial microaggressions and internalizing symptoms in college students of color more generally.

Role of Social Structure Beliefs as a Moderator

Social structure refers to the “enduring patterns of social life that shape an individual’s attitudes and beliefs; behaviors and actions; and material and psychological resources” [53, p. 5]. Among such attitudes, individualism and collectivism represent a continuum of values and beliefs regarding the self, respective to the groups of which the self holds membership [54]. Overall, people and cultures that are more collectivistic tend to perceive individual people as fundamental components of a cohesive community and emphasize interdependence, cooperation, and group harmony relative to those who are more individualistic. On the other end of the spectrum, relatively individualistic people and cultures tend to view individuals as independent from the group and place more value in autonomy, self-reliance, and competition relative to those who are more collectivistic. Singelis, Triandis, Bhawuk, and Gelfand [55] added an orthogonal horizontal-vertical dimension to the traditional conceptualization of individualism and collectivism to account for variance in the belief that members of a group are similar, and equality is expected (horizontal) or dissimilar, and inequality is expected (vertical). In this framework, a person who sees the self as interdependent and expects equality in a society can be described as endorsing horizontal collectivism, whereas those who most value autonomy and expect societal inequality are best categorized as vertical individualistic. Singelis and colleagues [55] posited that vertical individualism is the dominant social structure belief system in the United States, a hypothesis that has since been supported [56]. For people of color, orientation on the horizontal and vertical axes of individualism and collectivism may play an important role in mental health as the social support and expectation of equality emphasized in horizontal collectivism may attenuate the deleterious impacts of societal stress. On the other hand, subscribing to a more vertically individualistic outlook is likely to be associated with resigning to inevitable inequality and impede help-seeking behaviors [57].

From a sociological perspective, individualism emphasizes the ordering of the self above group interests [58], and the “rights of the individual as against the social” [59, p. 228]. Sociologists argue that individualism is a cultural construct that emerged with the collapse of feudal power and the rise of capitalist markets in Europe and North America from the 17th to the 19th centuries. The “culture and language of individualism” grew alongside Protestant beliefs, new forms of capitalist organization, and ideas of classical economic liberalism that emphasize “human life as an effort by individuals to maximize their self-interest” [60, p. 336]. Although Franklin D. Roosevelt spurred the growth of welfare liberalism with the New Deal, individualist, free-market ideas were revived in the 1970s, as the U.S. President Ronald Reagan defined the American people as a “special interest group” of self-reliant individuals who center both work and family [60, p. 262–263]. Individualism thus has a long cultural history in the United States and is deeply embedded in our institutions, social and economic policies, and political discourses. While American individualism is rife with contradictions, the individual remains “[a]t the center of American culture” [61, p. 369]. By pinpointing how current American cultural values of vertical individualism intersect with racism and mental health, the present study merges an attention to micro-individual experiences within the context of broader social structure.

Present Study

The purpose of the present study was to examine the impact ruminative thinking and individualistic vs. collectivistic beliefs have on the associations between racial/ethnic microaggressions and poorer mental health outcomes among non-White college students. Building off proposed mediation models of microaggressions [16], we first tested a mediational model linking school/workplace microaggressions to poor mental health outcomes (i.e., depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms) via ruminative thinking (i.e., problem-focused thoughts). In integrating a psycho-sociological perspective, we next conducted moderated-mediation models (see Figure 1) to explore whether the indirect associations between school/workplace microaggressions and poor mental health outcomes via problem-focused thoughts were moderated by individual differences in horizontal-vertical individualistic vs. collectivistic beliefs.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited from the Psychology Department participant pools at a large, U.S. southwestern university and a large, U.S. southeastern university. Although 884 students were recruited, to test study aims we limited our analytic sample to students who self-identified as racial/ethnic minorities (i.e., did not select White, non-Hispanic) and completed all the measures of study constructs. Among the 549 minority students, the majority were either Black/African-American (n = 179; 32.6%), or Hispanic, Latino, or of Spanish origin (n = 200; 36.4%), were female (n = 380; 70.2%), and reported a mean age of 20.64 (SD = 4.14, Median = 19.00) years. Of the participants who did not identify as Black or Latin(x), their racial/ethnic backgrounds were: 32 American Indian/Native American, 43 Asian, 12 Native Hawaiian, and 84 as other (e.g., mixed identity, or specific national groups [e.g., Middle Eastern]). The assessment battery took approximately one hour to complete, and participants received course credit for their participation. The institutional review boards at the respective institutions approved the studies.

Measures

For all measures (unless specified), composite scores were created by averaging items and reverse-coding items when appropriate such that higher scores indicate higher levels of the construct.

Microaggressions.

Microaggressions were assessed using a checklist version of the 45-item Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS-Checklist) [62] which assesses six distinct types of microaggressions: assumptions of inferiority, second-class citizen and assumptions of criminality, microinvalidations, exoticization/assumptions of similarity, environmental microaggressions, and workplace and school microaggressions. Each item was scored dichotomously (0 = no, 1 = yes) to reflect whether participants experienced that specific microaggression in the past six months. Given the college context, only the workplace/school microaggressions (4 items; e.g., “I was ignored at school or work because of my race”) subscale was examined. An initial examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the REMS-Checklist exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of microaggressions [6].

Rumination.

Rumination was assessed using the 20-item Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire (RTSQ) [42] measured on a 7-point response scale (1 = Not at all, 7 = Very Well). The participants were provided with instructions stating, “For each of the items below, please rate how well the item describes you.” Although an initial examination suggested a single factor structure, a more recent examination of the factor structure of the measure [63] revealed four rumination subcomponents: problem-focused thoughts, counterfactual thinking, repetitive thoughts, and anticipatory thoughts. For purposes of this study, only the problem-focused thoughts (e.g., consistent thinking of causes, consequences, and symptoms of negative affect) subscale was used. Recent psychometric work has provided further evidence of the validity and reliability of the four rumination subscales among college students [64].

Individualism and collectivism.

Beliefs of individualism (i.e., seeing the self as autonomous) and collectivism (i.e., seeing the self as part of a collective) were assessed using the 32-item Horizontal and Vertical Dimensions of Individualism and Collectivism Scale [55]. The measure categorizes individualism and collectivism by horizontal (equality among members) and vertical (inequality among members) dimensions. Specifically, four distinct subscales of social outlook exist: horizontal individualism (i.e., autonomous and recognize/accept equality among individuals), vertical individualism (i.e., autonomous but recognize/accept inequality among individuals), horizontal collectivism (i.e., collective and recognize/accept equality among individuals), and vertical collectivism (i.e., collective but recognize/accept inequality among individuals). Items were measured on a 9-point response scale (1 = never or definitely no, 9 = always or definitely yes), and all subscales consist of 8 items. Sample horizontal individualism subscale items include, “I often do ‘my own thing.’” Sample vertical individualism subscale items include, “Competition is the law of nature.” Sample horizontal collectivism subscale items include, “I feel good when I cooperate with others.” Sample vertical collectivism subscale items include, “I hate to disagree with others in my group.” An initial examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the scale exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of individualistic and collectivistic beliefs [55].

Anxiety symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms (i.e., worry) were assessed using the 16-item Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) [65] measured on a 5-point response scale (1 = not at all typical of me, 5 = very typical of me). Example items include, “Many situations make me worry” and “I have been a worrier all my life.” An examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the PSWQ exhibited good psychometric properties and is a valid measure of anxiety [66].

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 20-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression-Revised (CESD-R) [67] measured on a 5-point response scale (1 = Not at all or Less than 1 day, 2 = 1–2 Days, 3 = 3–4 Days, 4 = 5–7 Days, 5 = Nearly Every day for 2 weeks). The CESD-R assesses participants’ depressive symptoms that closely reflect the DSM-5 criteria for depression [68]. As advised by Van Dam and Earlywine [69], the ‘5–7 days’ and ‘nearly every day…’ were collapsed into the same value (i.e., 4). Example items include, “Nothing made me happy” and “I could not get going.” An examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the CESD-R exhibited good psychometric properties and is an accurate and valid measure of depression [69].

Stress symptoms.

Stress symptoms were assessed using the 14-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [70] measured on a 5-point response scale (1 = Never, 5 = Very Often). Example items include, “In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things you had to do?” and “In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them?” An examination of the psychometric properties of the measure revealed that the PSS exhibited good psychometric properties and is a valid measure of stress [71].

Data Analysis Plan

Mediation and moderated-mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS 3.0 macro for SPSS [72]. We first conducted mediation analyses (Model 4 in PROCESS) to test parts of Wong et al.’s [16] psychological mediation model of microaggressions (i.e., workplace and school microaggressions→problem-focused thoughts→depression/anxiety/stress symptoms) (3 models, one for each outcome). We next conducted moderated-mediation analyses (Model 7 in PROCESS) with horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism as moderators of the association between school/workplace microaggressions and problem-focused thoughts (12 models, one for each outcome and dimension of individualism/collectivism). Variables were standardized to produce standardized regression coefficients. Statistical significance was determined by 95% percentile bootstrapped confidence intervals (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that do not contain zero, and interactions were probed at low (1 SD below the mean), medium (average levels), and high levels (1 SD above the mean of the moderator). For significant moderated-mediation effects, we further examined the conditional indirect effect of school/workplace microaggressions to negative affect symptoms via problem-focused thoughts at various levels of the dimensions of individualism/collectivism.

Results

Bivariate correlations, descriptive statistics, and internal consistency of all study variables are presented in Table 1. Among the mediation models, school/workplace microaggressions were significantly associated with higher levels of problem-focused thoughts (β = .10, 95% CI [.01, .18]), depressive symptoms (β = .20, 95% CI [.12, .28]) and stress symptoms (β = .08, 95% CI [.004, .15]), but not with anxiety symptoms (β = −.02, 95% CI [−.10, .05]). Further, problem-focused thoughts were significantly associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms (β = .33, 95% CI [.25, .41]), stress symptoms (β = .53, 95% CI [.46, .60]), and anxiety symptoms (β = .54, 95% CI [.47, .61]). In support of Wong et al.’s [16] microaggressions mediation model, problem-focused thoughts mediated the associations between school/workplace microaggressions and depressive symptoms (indirect β = .03, 95% CI [.003, .06]), stress symptoms (indirect β = .05, 95% CI [.004, .10]), and anxiety symptoms (indirect β = .05, 95% CI [.01, .10]). Specifically, higher rates of school/workplace microaggressions were associated with higher problem-focused thoughts; which in turn was associated with higher levels of negative affect symptoms.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations among study variables in total sample

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. School Microaggressions | .74 | 0.56 | 1.04 | ||||||||

| 2. Problem-focused Thoughts | .10 | .89 | 3.72 | 1.30 | |||||||

| 3. Vertical Individualism | .03 | .13 | .85 | 4.94 | 1.63 | ||||||

| 4. Horizontal Individualism | .02 | −.01 | .18 | .87 | 7.22 | 1.25 | |||||

| 5. Horizontal Collectivism | −.03 | −.02 | .02 | .38 | .85 | 6.84 | 1.30 | ||||

| 6. Vertical Collectivism | .08 | .09 | .11 | .07 | .41 | .82 | 5.69 | 1.44 | |||

| 7. Depressive Symptoms | .23 | .35 | .09 | −.10 | −.11 | .03 | .95 | 0.75 | 0.70 | ||

| 8. Anxiety (Worry) | .03 | .54 | .08 | −.01 | .10 | .09 | .34 | .86 | 3.24 | 0.83 | |

| 9. Stress Symptoms | .13 | .53 | .09 | −.06 | −.10 | −.04 | .44 | .48 | .73 | 2.93 | 0.44 |

Note. Significant correlations (p < .05) are bolded for emphasis. Cronbach’s alphas are underlined and shown on the diagonals.

Moderated-Mediation Models

Among the four dimensions of individualism/collectivism, only individual differences in vertical individualism significantly moderated the association between school/workplace microaggressions and problem-focused thoughts within the models: vertical individualism (β = .12, 95% CI [.04, .21]), vertical collectivism (β = −.01, 95% CI [−.09, .08]), horizontal individualism (β = −.01, 95% CI [−.09, .06]), and horizontal collectivism (β = −.02, 95% CI [−.10, .06]). Specifically, the association between school/workplace microaggressions and problem-focused thoughts was strongest among individuals with higher levels of vertical individualism: low level (1 SD below mean), β = −.04, 95% CI (−.16, .08), average level, β = .08, 95% CI (−.001, .16), and high level (1SD above mean), β = .20, 95% CI (.09, .31). In examining the three negative affect outcomes, each model indicated a significant moderated-mediation effect based on a PROCESS-provided index of moderation [73]: depressive symptoms (Index = .04, 95% CI [.01, .07]), stress symptoms (Index = .06, 95% CI [.02, .11]), and anxiety symptoms (Index = .07, 95% CI [.02, .11]). Specifically (see Table 2), for all negative affect symptoms the indirect effect coefficient for individuals with high vertical individualism was significantly stronger compared to individuals reporting average and low levels. The indirect effect coefficient for individuals reporting average vertical individualism was also significantly stronger than individuals reporting low levels. Taken together, these findings indicate a statistically significant moderated mediation effect, such that the indirect effect from school/workplace microaggressions to mental health outcomes via problem-focused thoughts was stronger among those reporting high levels of vertical individualism than among individuals reporting low levels of vertical individualism and average levels of vertical individualism.

Table 2.

Conditional indirect effects of workplace/school microaggressions to negative affect outcomes via problem-focused thoughts by levels of vertical individualism

| Outcome: Depressive Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conditional Indirect Effects | β | 95% CI |

| Vertical Individualism Level: High (1 SD) | .068 | [.032, .107] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Average | .028 | [.002, .057] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Low (−1 SD) | −.013 | [−.054, .031] |

| Indirect Effect Differences | β | 95% CI |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .081 | [.023, .138] |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Average Vertical Individualism | .041 | [.012, .069] |

| Average Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .041 | [.012, .069] |

| Outcome: Anxiety (Worry) | ||

| Conditional Indirect Effects | β | 95% CI |

| Vertical Individualism Level: High (1 SD) | .112 | [.055, .170] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Average | .045 | [.001, .092] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Low (−1 SD) | −.021 | [−.084, .050] |

| Indirect Effect Differences | β | 95% CI |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .133 | [.041, .218] |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Average Vertical Individualism | .067 | [.020, .109] |

| Average Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .067 | [.020, .109] |

| Outcome: Stress Symptoms | ||

| Conditional Indirect Effects | β | 95% CI |

| Vertical Individualism Level: High (1 SD) | .105 | [.047, .164] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Average | .043 | [−.001, .089] |

| Vertical Individualism Level: Low (−1 SD) | −.019 | [−.085, .050] |

| Indirect Effect Differences | β | 95% CI |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .124 | [.034, .211] |

| High Vertical Individualism vs. Average Vertical Individualism | .062 | [.017, .105] |

| Average Vertical Individualism vs. Low Vertical Individualism | .062 | [.017, .105] |

Note. Significant effects are in bold typeface for emphasis and were determined by a 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval (based on 10,000 bootstrapped samples) that does not contain zero.

Discussion

College students of color experience frequent microaggressions at school, with one recent study finding that 98.8% of students of color report such experiences [74]. These experiences act as chronic stressors [2] that can negatively impact well-being [75], even more so than overt forms of racism [15]. Consistent with previous research with secondary and post-secondary students [e.g., 21, 33, 36], our results demonstrated that non-White college students’ experiences of microaggressions are associated with greater depressive and stress symptoms. The present study also extended previous work by demonstrating that problem-focused thoughts (a form of ruminative thinking) mediated the associations between microaggressions and negative psychological symptoms. Furthermore, the indirect effect of self-reported microaggressions on mental health outcomes via problem-focused thoughts was stronger in students with high levels of vertical individualism than those with low or average levels. The interdisciplinary psycho-sociological approach sheds light on macro-structural inequalities as well as individual, psychological health outcomes.

The current study demonstrated that racial/ethnic minority participants who experienced more microaggressions also engaged in more problem-focused thinking, a type of rumination. Experiencing microaggressions is likely to lead to rumination given the ambiguity of microaggressions, as they are often not ill-intended [50]. Indeed, rumination is an emotion regulation strategy that allows individuals to cope with chronic stressors related to their stigmatized identity [76, 77], although it is typically ineffective as it can intensify negative psychological outcomes, consistent with our results [52, 77–79]. Previous research has demonstrated that rumination mediates the relationships between microaggressions and depressive symptoms in sexual minorities [50] and between microaggressions and psychological distress in sexual minorities, African Americans [52], and transgender individuals [51]. Our finding that problem-focused thoughts mediated the relationships between microaggressions, and mental health outcomes is consistent with this previous work but also extends the literature in important ways. First, we identified the problem-focused thoughts subscale of rumination as a mediator as it is specific to the causes, consequences, and symptoms of negative affect specifically, which are related to mental health outcomes. Second, previous research examining the relationships between microaggressions, rumination, and mental health outcomes has focused on non-college sexual minorities, [50, 52] although one study also included a small group of African American individuals [52]. Our use of a large sample of racial/ethnic minority undergraduates extends this previous work.

An additional goal of the current project was to assess individual differences on positionality of the horizontal-vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism as a potential moderator. Our findings suggested that the mediation model was stronger for individuals high in vertical individualism relative to those with lower levels. Individuals who are high in vertical individualism see their in-group members as different from one another rather than homogenous [80]. Furthermore, although these individuals feel that all people should have a right to be equal, they perceive inequality within the group and thus self-reliance within the competition of different group members is important [55, 80]. It is possible that differences in the coping mechanisms used by individuals high and low in vertical individualism differ in their responses to chronic stressors such as microaggressions. Individuals low in vertical individualism are less autonomous and thus may seek out social support from their peers, which decreases the relationship between victimization and psychological distress [81]. On the other hand, for individuals high in vertical individualism, who are more autonomous and socially isolated [82], ruminating about a negative interpersonal experience such as a microaggression might account more for the negative mental health outcomes. These findings can have implications for our understanding of individual differences in emotion regulation strategies.

This work makes an important contribution to the field but has several limitations that should be considered. First, we did not have high statistical power to analyze whether the above models would differ between specific ethnic/racial groups, but future research with larger samples should examine this possibility. In addition, it is important to include students of color from other racial groups as participants in future studies. Furthermore, although this study examined college students as its targeted population, it is unclear whether the effects found here would generalize to non-college samples. Our study was also limited by the use of students at American universities. Because vertical and horizontal individualism and collectivism differs by nationality [55], non-American samples will provide further information about the role of these individual differences in the link between experiencing microaggressions and mental health outcomes. Another limitation of our work is that this study was cross-sectional and thus it did not allow for the examination of causal relations; future longitudinal and experimental research is needed to test whether the relationships found in the current work demonstrate temporally ordered causal relationships. That is, it is possible that microaggressions cause more negative mental health outcomes, with problem-focused thoughts occurring temporally between these two measures; however, it is also possible that students with more negative mental health outcomes are more likely to perceive their interactions with others as microaggressions than those with less negative mental health outcomes, particularly if they are high in vertical individualism. Future research should seek to elucidate the temporal relationships between these variables.

Despite the limitations of the study, the current work extends our understanding of the mechanisms underlying the negative mental health effects of experiencing microaggressions in racial/ethnic minority college students. By incorporating research, methods, and tools from sociology and psychology, this article answers Wong et al.’s [16] call for research that integrates multiple models of stress. We have provided a structural context for psychological health outcomes resulting from microaggressions in schools and workplaces, bridging sociology’s attention to institutional and social contexts with a cognitive and affective approach to process, by which experiences of microaggressions are associated with negative psychological well-being. Specifically, the identification of problem-focused thoughts as a mediator between microaggressions and negative psychological symptoms offers insight into the coping strategies that college students of color use. Future research may examine how teaching students of color more effective coping strategies such as relying on social support [81] can mitigate some of the negative mental health consequences that result from experiencing microaggressions. In addition, because individuals who confront instances of racism ruminate less and experience less depression than those who do not confront [83, 84], students of color may be encouraged to confront microaggressions by expressing dissatisfaction and anger to the source. Interventions such as mindfulness training may also be effective, as mindfulness moderates the effect of racial discrimination on depression and anxiety [85]. Finally, it may be fruitful to strengthen racial identity in students of color, as research has demonstrated that strong racial identity can reduce the negative effects of discrimination on psychological distress [86].

In addition to promoting individual coping strategies, scholars can continue to highlight the institutional and structural origins of microaggressions, and their intersections with cultural ideologies and social conditions, by drawing from quantitative data as well as in-depth qualitative methods such as interviews and observations. While microaggressions in undergraduate institutions are currently understudied [30], it is also important to diversify sites and geographic locations studied. Future research can incorporate an intersectional lens [87] to analyze the interplay between social identities, including race, gender, sexuality, or religion. Given that “faith often trumps individualism” [61, p. 367], scholarship can specifically explore the intersections between religiosity/access to faith groups, mental health, and experiences with racism and microaggressions. In addition, in testing this moderated-mediation model, we expand upon existing literature to better understand the role of the horizontal-vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism on shaping this process. The racial diversity of our sample, which includes Black, Asian, and Latinx students, also offers a comprehensive slice of how racial and ethnic minorities experience microaggressions in schools and workplaces, and the resulting specific psychological health effects. It is important that future research continues to seek racially diverse samples in order to tease out the various experiences of people encountering microaggressions across racial and ethnic groups.

This research has implications for social policy in schools, workplaces, and more broadly. State or federal level policies that target the physical and mental health of minority groups could provide material and social support to those who are more vulnerable to instances of everyday racism, such as microaggressions. Schools, workplaces, and other institutions can create clear pathways for individuals to report microaggressions, collecting experiences and data about the nature and frequency of these interactions in order to tailor organizational responses. Campbell [88] also emphasized the importance of workplace trainings to cultivate awareness of racial microaggressions on an individual level. In regard to university policies, Solorzano, Ceja, and Yosso [15, p. 62] have identified four elements of a positive collegiate racial climate:

(a) including students, faculty, and administrators of color; (b) a curriculum that reflects the historical and contemporary experiences of people of color; (c) programs to support the recruitment, retention and graduation of students of color; and (d) a college/university mission that reinforces the institution’s commitment to pluralism.

We echo these suggestions, underscoring how microaggressions reflect structurally-situated inequalities—such as a lack of visibility, inclusion, or retention of people of color on college campuses—and necessitate more racially-inclusive policies and practices.

Scholars can continue to explore the everyday experiences of microaggressions while integrating an attention to biological and psychological stress responses. Future research can also contextualize the specific policies and practices of higher learning institutions to assess racial climate and its impact on psychological health [15]. This study also suggests that identifying moderating individual difference variables such as horizontal-vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism is important in understanding the relations between microaggressions, coping strategies, and mental health outcomes.

Role of Funding Sources

Dr. Pearson is supported by a career development grant (K01-AA023233) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) in the United States.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflict of Interest: RF declares that she has no conflict of interest. EW declares that she has no conflict of interest. LH declares that he has no conflict of interest. CLD declares that she has no conflict of interest. MRP declares that he has no conflict of interest. AJB declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in our study were approved by the institutional review boards at the participating universities and in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the present study.

Contributor Information

Reya Farber, Department of Sociology, William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

Emma Wedell, Department of Psychological Sciences, William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

Luke Herchenroeder, Department of Psychological Sciences, William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

Cheryl L. Dickter, Department of Psychological Sciences, William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

Matthew R. Pearson, Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse, and Addictions, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico, USA.

Adrian J. Bravo, Department of Psychological Sciences, William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, USA.

References

- 1.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212–5. 10.2105/ajph.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, Esquilin M. Racial microaggressions in everyday life: implications for clinical practice. Am Psychol. 2007;62:271–86. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yosso TJ, Smith WA, Ceja M, Solórzano DG. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate for Latina/o undergraduates. Harv Educ Rev. 2009;79:659–91. 10.17763/haer.79.4.m6867014157m707l [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaskan E, Ho I. Microaggressions and female athletes. Sex Roles. 2014;74(7):275–87. 10.1007/s11199-014-0425-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadal KL, Davidoff KC, Davis LS, Wong Y. Emotional, behavioral, and cognitive reactions to microaggressions: transgender perspectives. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2014;1(1):72–81. 10.1037/sgd0000011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Microaggressions Nordmarken S.. Transgender Studies Quarterly. 2014;1(1–2):129–34. 10.1215/23289252-2399812 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulice-Farrow L, Brown TD, Galupo MP. Transgender microaggressions in the context of romantic relationships. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4(3):362–73. 10.1037/sgd0000238 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadal KL, Davidoff KC, Davis LS, Wong Y, Marshall D, McKenzie V. Intersectional identities and microaggressions: influences of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and religion. Qual Psychol. 2015;2(2):147–63. 10.1037/qup0000026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shelton K, Delgado-Romero EA. Sexual orientation microaggressions: the experience of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer clients in psychotherapy. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2013;1(S), 59–70. 10.1037/2329-0382.1.S.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng ZH, Pagano LA Jr., Shariff AF. The development, validation, and clinical implications of the Microaggressions Against Religious Individuals Scale (MARIS). Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2017;11(4):327–38. 10.1037/rel0000126 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nadal K, Griffin KE, Hamit S, Leon J, Tobio M, Rivera D. Subtle and overt forms of Islamophobia: microaggressions toward Muslim Americans. J Muslim Ment Health. 2012;6(2):16–37. 10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0006.203 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keum BT, Brady JL, Sharma R, Lu Y, Kim YH, Thai CJ. Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Asian American Women: development and initial validation. J Couns Psychol. 2018;65(5):571–85. 10.1037/cou0000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis JA, Neville HA. Construction and initial validation of the Gendered Racial Microaggressions Scale for Black women. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):289–302. 10.1037/cou0000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olkin R, Hayward H, Abbene MS, VanHeel G. The experiences of microaggressions against women with visible and invisible disabilities. J Soc Issues. 2019;75(3):757–85. 10.1111/josi.12342 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solorzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: the experiences of African American college students. J Negro Educ. 2000;69(1/2):60–73. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong G, Derthick AO, David EJ, Saw A, Okazaki S. The what, the why, and the how: a review of racial microaggressions research in psychology. Race Soc Probl. 2013;6(2):181–200. 10.1007/s12552-013-9107-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sue DW, editor. Microaggressions and marginality: manifestation, dynamics, and impact. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Essed P Understanding everyday racism: an interdisciplinary theory. Newbury Park, California: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Embrick DG, Domínguez S, Baran K. More than just insults: rethinking sociology’s contribution to scholarship on racial microaggressions. Sociol Inq. 2017;87(2):193–206. 10.1111/soin.12184 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huber LP, Solorzano DG. Racial microaggressions as a tool for critical race research. Race Ethn Educ. 2015;18(3):297–320. 10.1080/13613324.2014.994173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keels M, Durkee M, Hope E. The psychological and academic costs of school-based racial and ethnic microaggressions. Am Educ Res J. 2017;54(6):1316–44. 10.3102/0002831217722120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Omi M, Winant H. Racial formation in the United States. New York: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livingston NA, Berke DS, Ruben MA, Matza AR, Shipherd JC. Experiences of trauma, discrimination, microaggressions, and minority stress among trauma-exposed LGBT veterans: unexpected findings and unresolved service gaps. Psychol Trauma. 2019;11(7):695–703. 10.1037/tra0000464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson JG, Jabson Tree JM, Kamen C. Cultural competency and microaggressions in the provision of care to LGBT patients in rural and appalachian Tennessee. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(11):2081–90. 10.1016/j.pec.2019.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills KJ. ‘It’s systemic’: environmental racial microaggressions experienced by Black undergraduates at a predominantly White institution. J Divers High Educ. 2019; 10.1037/dhe0000121 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Firmin RL, Mao S, Bellamy CD, Davidson L. Peer support specialists’ experiences of microaggressions. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(3):456–62. 10.1037/ser0000297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitcan M, Park TJ, Hayslett J. Black men and racial microaggressions at work. Career Dev Q. 2018;66(4):300–14. 10.1002/cdq.12152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houshmand S, Spanierman LB, De Stefano J. “I have strong medicine, you see”: strategic responses to racial microaggressions. J Couns Psychol. 2019;66(6):651–64. 10.1037/cou0000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nadal KL, Wong Y, Griffin KE, Davidoff K, Sriken J. The adverse impact of racial microaggressions on college students’ self-esteem. J Coll Stud Dev. 2014;55(5):461–74. 10.1353/csd.2014.0051 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baker J Through the looking glass: White first-year university students’ observations of racism in St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Sociol Inq. 2017;8(2):362–84. 10.1111/soin.12165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith WA, Allen W, Danley LL. “Assume the position…you fit the description”: psychosocial experiences and racial battle fatigue among African American male college students. Am Behav Sci. 2007;51(4):551–78. 10.1177/0002764207307742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blume AW, Lovato LV, Thyken BN, Denny N. The relationship of microaggressions with alcohol use and anxiety among ethnic minority college students in a historically White institution. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2012;18:45–54. 10.1037/a0025457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogunyemi D, Clare C, Astudillo YM, Marseille M, Manu E, Kim S. Microaggressions in the learning environment: a systematic review. J Divers High Educ. 2019; 10.1037/dhe0000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Forrest-Bank SS, Jenson JM. The relationship among childhood risk and protective factors, racial microaggression and ethnic identity, and academic self-efficacy and antisocial behavior in young adulthood. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2015;50:64–74. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su J, Kuo SI-C, Derlan CL, Hagiwara N, Guy MC, Dick DM. Racial discrimination and alcohol problems among African American young adults: examining the moderating effects of racial socialization by parents and friends. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019; 10.1037/cdp0000294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huynh VW. Ethnic microaggressions and the depressive and somatic symptoms of Latino and Asian American adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2012;41(7):831–46. 10.1007/s10964-012-9756-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Keefe VM, Wingate LR, Cole AB, Hollingsworth DW, Tucker RP. Seemingly harmless racial communications are not so harmless: racial microaggressions lead to suicidal ideation by way of depression symptoms. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2015;45(5):567–76. 10.1111/sltb.12150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Forrest-Bank SS, Cuellar MJ. The mediating effects of ethnic identity on the relationships between racial microaggression and psychological well-being. Soc Work Res. 2018;42(1):44–56. 10.1093/swr/svx023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez D, Adams WN, Arango SC, Flannigan AE. Racial-ethnic microaggressions, coping strategies, and mental health in Asian American and Latinx American college students: a mediation model. J Couns Psychol. 2018;65(2):214–25. 10.1037/cou0000249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Torres-Harding S, Torres L, Yeo E. Depression and perceived stress as mediators between racial microaggressions and somatic symptoms in college students of color. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2019; 10.1037/ort0000408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hernández RJ, Villodas MT. Overcoming racial battle fatigue: the associations between racial microaggressions, coping, and mental health among Chicana/o and Latina/o college students. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019; 10.1037/cdp0000306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brinker JK, Dozois DJA. Ruminative thought style and depressed mood. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1–19. 10.1002/jclp.20542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalmbach DA, Pillai V, Ciesla JA. The correspondence of changes in depressive rumination and worry to weekly variations in affective symptoms: a test of the tripartite model of anxiety and depression in women. Aust J Psychol. 2016;68(1):52–60. 10.1111/ajpy.12090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang M, Kim B, Lee E, Lee D, Yu B, Jeon HJ, Kim J. Diagnostic utility of worry and rumination: a comparison between generalized anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;68(9):712–20. 10.1111/pcn.12193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zawadzki MJ. Rumination is independently associated with poor psychological health: comparing emotion regulation strategies. Psychol Health. 2015;30(10):1146–63. 10.1080/08870446.2015.1026904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African Americans: a biopsychosocial model. Am Psychol, 1999;54(10):805–16. 10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miranda R, Polanco-Roman L, Tsypes A, Valderrama J. Perceived discrimination, ruminative subtypes, and risk for depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2013;19(4):395–403. 10.1037/a0033504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liao KY-H, Kashubeck-West S, Weng C-Y, Deitz C. Testing a mediation framework for the link between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among sexual minority individuals. J Couns Psychol. 2015;62(2):226–41. 10.1037/cou0000064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaufman TML, Baams L, Dubas JS. Microaggressions and depressive symptoms in sexual minority youth: the roles of rumination and social support. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4(2):184–92. 10.1037/sgd0000219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Timmins L, Rimes KA, Rahman Q. Minority stressors and psychological distress in transgender individuals. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2017;4(3):328–40. 10.1037/sgd0000237 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: the mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychol Sci. 2009;20(10):1282–9. 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S15–S27. 10.1177/0022146510383838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sampson EE. The debate on individualism: Indigenous psychologies of the individual and their role in personal and societal functioning. Am Psychol. 1988;43(1):15–22. 10.1037/0003-066X.43.1.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singelis TM, Triandis HC, Bhawuk DP, Gelfand MJ. Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: a theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross Cul Res. 1995;29(3):240–75. 10.1177/106939719502900302 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chiou J-S. Horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism among college students in the United States, Taiwan, and Argentina. J Soc Psychol. 2001;141(5):667–78. 10.1080/00224540109600580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shavitt S, Cho YI, Johnson TP, Jiang D, Holbrook A, Stavrakantonaki M. Culture moderates the relation between perceived stress, social support, and mental and physical health. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2016;47(7):956–80. 10.1177/0022022116656132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parsons T, Shils E. Toward a general theory of social interaction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1951. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abrams P Historical Sociology. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bellah RN, Madsen R, Sullivan WM, Swidler A, Tipton SM. Habits of the heart: individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fischer C Paradoxes of American individualism. Sociol Forum. 2008;23(2):363–72. 10.1111/j.1573-7861.2008.00066.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nadal KL. The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): construction, reliability, and validity. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(4):470–80. 10.1037/a0025193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tanner A, Voon D, Hasking P, Martin G. Underlying structure of ruminative thinking: factor analysis of the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire. Cognit Ther Res. 2013;37(3):633–46. 10.1007/s10608-012-9492-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bravo AJ, Pearson MR, Pilatti A, Mezquita L, Ibáñez MI, Ortet G. Ruminating in English, ruminating in Spanish: psychometric evaluation and validation of the Ruminative Thought Style Questionnaire in Spain, Argentina, and USA. Eur J Psychol Assess. 2018;35:779–90. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000465 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behav Res Ther. 1990;28(6):487–95. 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Molina S, Borkovec TD. The Penn State Worry Questionnaire: psychometric properties and associated characteristics. In: Davey GCL, Tallis F, editors. Worrying: perspectives on theory, assessment, and treatment. Oxford, England: John Wiley & Sons; 1994. pp. 265–83. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. (2004). Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). In Maruish ME, editor. The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 363–77. [Google Scholar]

- 68.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale—revised (CESD-R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2011;186(1):128–32. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cohen S, Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the U.S. In: Spacapam S, Oskamp S, editors. The social psychology of health. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1988. pp. 31–67. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hayes AF. An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behav Res. 2015;50(1):1–22. 10.1080/00273171.2014.962683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lilly FR, Owens J, Bailey TC, Ramirez A, Brown W, Clawson C, et al. The influence of racial microaggressions and social rank on risk for depression among minority graduate and professional students. Coll Stud J. 2018;52(1):86–104. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carter RT, Forsyth J. Reactions to racial discrimination: emotional stress and help-seeking behaviors. Psychol Trauma. 2010;2(3):183–91. 10.1037/a0020102 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Miller CT, Kaiser CR. A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. J Soc Issues. 2001;57(1):73–92. 10.1111/0022-4537.00202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3(5):400–24. 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hatzenbuehler ML, McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Emotion regulation and internalizing symptoms in a longitudinal study of sexual minority and heterosexual adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49(12):1270–8. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.01924.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Michl LC, McLaughlin KA, Shepherd K, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a mechanism linking stressful life events to symptoms of depression and anxiety: longitudinal evidence in early adolescents and adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(2):339–52. 10.1037/a0031994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Triandis HC, Bontempo R, Villareal MJ, Asai M, Lucca N. Individualism and collectivism: cross-cultural perspectives on self-ingroup relationships. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(2):323–88. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.2.323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ueno K Sexual orientation and psychological distress in adolescence: examining interpersonal stressors and social support processes. Soc Psychol Q. 2005;68(3):258–77. 10.1177/019027250506800305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Triandis HC. Individualism and collectivism: past, present, and future. In: Matsumoto D, editor. The handbook of culture and psychology. New York: NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hyers LL. Resisting prejudice every day: exploring women’s assertive responses to anti-Black racism, anti-Semitism, heterosexism, and sexism. Sex Roles. 2007;56(1–2):1–12. 10.1007/s11199-006-9142-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):193–207. 10.2307/2676348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zapolski TC, Faidley MT, Beutlich MR. The experience of racism on behavioral health outcomes: the moderating impact of mindfulness. Mindfulness. 2019;10(1):168–78. 10.1007/s12671-018-0963-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):302–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crenshaw K Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–99. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Campbell J Cultivating awareness of racial microaggressions. Social Innovations Journal. 2018. https://socialinnovationsjournal.org/editions/issue-42/75-disruptive-innovations/2724-cultivating-awareness-of-racial-microaggressions. Accessed 28 Apr 2020. [Google Scholar]