Abstract

Exposure to childhood trauma is extremely common (>60%) and is a leading risk factor for fear-based disorders, including anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder. These disorders are characterized by deficits in fear extinction and dysfunction in underlying neural circuitry. Given the strong and pervasive link between childhood trauma and the development of psychopathology, fear extinction may be a key mechanism. The present study tests the impact of childhood trauma exposure on fear extinction and underlying neural circuitry. Children (N = 44, 45% trauma-exposed; 6–11 yrs) completed a novel two-day virtual reality fear extinction experiment. On day one, participants underwent fear conditioning and extinction. Twenty-four hours later, participants completed a test of extinction recall during fMRI. Conditioned fear was measured throughout the experiment using skin conductance and fear-related behavior, and activation in fear-related brain regions was estimated during recall. There were no group differences in conditioned fear during fear conditioning or extinction learning. During extinction recall, however, trauma-exposed children kept more distance from both the previously extinguished and the safety cue, suggesting poor differentiation between threat and safety cues. Trauma-exposed youth also failed to approach the previously extinguished cue over the course of extinction recall. The effects on fear-related behavior during extinction recall were accompanied by higher activation to the previously extinguished cue in fear-relevant brain regions, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula, in trauma-exposed relative to control children. Alterations in fear-related brain regions and fear-related behavior may be a core mechanism through which childhood trauma confers heightened vulnerability to psychopathology.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, childhood adversity, fear conditioning, fMRI, extinction recall

1. Introduction

Exposure to childhood trauma is considered to be a leading risk factor for psychiatric disorders, particularly fear-based disorders including anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), during childhood, adolescence, and adulthood [1–4]. Unfortunately, exposure traumatic events such as physical abuse or witnessing violence, is extremely common during childhood, with national survey studies showing that nearly two thirds of youth will experience one or more traumas before their 18th birthday [5,6]. In addition, epidemiological studies show that childhood trauma exposure may be even more common among lower socioeconomic status (SES) households [7]. Although the strong and pervasive link between exposure to childhood trauma and psychiatric disorders has been well-defined, we still lack mechanistic understanding of how childhood trauma alters brain development in ways that increase risk of future fear-based disorders.

A primary translational target for understanding the neurobiological basis of fear-based disorders is the neural circuitry involved in fear learning and extinction [8]. During Pavlovian fear conditioning, a previously innocuous cue (conditioned stimulus, CS+) is paired with an aversive unconditioned stimulus (US). After repeated pairings, presentation of the CS+ alone elicits a conditioned fear response, measured, for example, by elevated skin conductance responses (SCRs). Fear extinction is a form of fear regulation wherein the previously conditioned cue (CS+) is no longer paired with the aversive US. This new learning (i.e., CS-no aversive US association) interferes with the expression of conditioned fear, resulting in a gradual reduction of conditioned fear (e.g., lower SCRs) to the extinguished cue (CS+E) over the course of extinction learning. Importantly, adults with anxiety disorders and PTSD show deficits in extinction learning and the later ability to retain this learning, evidenced by heightened SCRs to the CS+E during a test of extinction recall [9–12]. A recent meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in adults with PTSD show that the deficits in extinction learning and recall are accompanied by a consistent pattern of increased activation of fear-relevant brain regions, including the amygdala, anterior insula (AI), and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) [13]. Hyperactivity of these brain regions, which promote the detection and expression of fear, was observed in patients with PTSD during extinction recall, as well as, during extinction learning and fear conditioning [13]. This pattern of hyperactivity is consistent with the clinical profile of prolonged and exaggerated threat responding in PTSD [13,14]. In addition, during extinction recall, adults with PTSD consistently show lower activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), a region linked to the successful recall of extinction learning in healthy adults [15–18]. Together, these activation patterns suggest aberrant activation of fear-related brain regions and/or deficient activation of brain regions supporting extinction recall in adults with anxiety and PTSD. Although fewer studies have been conducted in children and adolescents, impaired extinction learning is consistently reported across youth with anxiety disorders and PTSD [19,20]. In these studies, fear conditioning is largely comparable between youth with anxiety and unaffected controls, although poor discrimination between threat and safety cues has been reported in more anxious youth relative to less anxious youth during fear conditioning [see 21]. Together, given that alterations in fear extinction are commonly reported in anxiety disorders and PTSD in adults and in youth, exposure to childhood trauma may alter fear extinction and/or functioning of fear-relevant neural circuitry in a way that increases risk of fear-based disorders.

Emerging neuroimaging studies in youth support the hypothesis that exposure to fear-inducing events during childhood alters structure and function of fear-related neural circuitry. For example, childhood trauma exposure has been linked to increased volume of the amygdala [22], increased activation in regions involved in fear expression (e.g., amygdala, dACC) during emotion regulation tasks [22–24], and altered resting-state functional connectivity between fear-relevant brain regions (amygdala-dACC and amygdala-AI) [25,26]. To our knowledge, three studies have examined the impact of trauma exposure on fear conditioning and/or extinction learning in children. In a recent study of 4–7-year-olds, Machlin et al. [27] reported no main effects of trauma exposure (as defined by higher levels of early threat, e.g., violence) on SCR amplitude to the CS+ during fear conditioning, controlling for SCR amplitude to the CS−. There was, however, an age x trauma interaction for SCRs to the CS+ during early (but not late) fear conditioning such that SCRs increased with age among trauma-naïve (but not trauma-exposed) children [27]. In the trauma-exposed group, in contrast, children exhibited SCR responses to the CS+ across the entire age range (4–7 years). The authors interpreted this lack of age-related effects in the trauma-exposed group as an earlier emergence of differential fear conditioning in this group. Earlier emergence of fear conditioning fits with research suggesting accelerated development of fear learning processes in the context of dangerous and/or unpredictable threat (e.g., violence), which may be adaptive in the short-term but harmful in the long-term [28]. Indeed, in an older sample of 6–18 year-olds, McLaughlin et al. [29] demonstrated poorer differentiation in SCRs between the threat (CS+) and safety (CS−) cues during fear conditioning in trauma-exposed relative to unexposed children and adolescents. This effect was driven by blunted SCRs to the CS+ during conditioning in the trauma-exposed group [29]. Thus, the earlier emergence of aversive learning observed in younger trauma-exposed children may transition to a difficulty in discriminating between threat and safety cues by adolescence. In the same sample, trauma-exposed children showed higher SCRs to the CS+E during extinction learning, supporting the notion that fear and extinction learning may be altered among trauma-exposed children and adolescents [30].

Although the aforementioned studies suggest that trauma exposure alters fear-related learning in children, there have been no studies reporting the effects of childhood trauma on extinction recall. The effects of childhood trauma may be more apparent during extinction recall, in particular, because of immature neural circuitry. Indeed, previous studies by our group and others show that pre-adolescent children are capable of fear conditioning and extinction learning within-session [31,32]. However, overall, pre-adolescent children show poor between-session recall of extinction learning, as measured by heightened SCR amplitudes and an avoidant behavioral pattern 24 hours following extinction learning [31]. These conditioned fear measures indicate poor extinction recall in children, which was accompanied by activation of fear-relevant brain regions, including the dACC and AI, during extinction recall [31]. Together, these data suggest that the neural circuitry implicated in supporting extinction recall in healthy adults (e.g., vmPFC) is immature in pre-adolescent children, fitting with data suggesting protracted development of top-down connections from the vmPFC to amygdala [33]. Rather, pre-adolescent children show a pattern of fear expression that is similar to what is observed in healthy adults during contextual reinstatement of fear (i.e., higher SCRs and activation of the dACC and AI) [34]. These patterns also resemble those reported in adults with PTSD – i.e., poor recall and heightened activation of fear-relevant brain regions (i.e., dACC, AI, amygdala) [12]. Aberrant activation of fear-related brain regions during extinction recall may explain variability in between-session retention of therapeutic gain for treatments that rely on principles of extinction, such as exposure-based therapy [35]. Importantly, exposure to fear-inducing events during childhood may exacerbate activation of fear-related brain regions and fear-related behavior. Thus, trauma-exposed children may show aberrant activation of fear-relevant brain regions during extinction recall. Inappropriate activation of these regions may impair the development of neural networks supporting extinction recall, as seen in healthy adults [e.g., 18]. In other words, trauma-exposed children may have an adult-like ability to learn fear and extinguish fear within-session, but may not be able to easily overcome it, evidenced by the between-session return.

The present study uses a novel Pavlovian fear extinction paradigm previously adapted and validated by our group [32] to assess the impact of childhood trauma exposure on fear conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall in pre-adolescent children. Using fMRI, we also examine the effects of trauma on activation of fear-relevant brain regions during extinction recall. Based on prior studies of trauma exposure in youth [27,29,30], we predict that trauma-exposed pre-adolescent children will show higher conditioned fear to the CS+ or CS+E during fear conditioning and extinction learning, respectively, relative to trauma naïve youth. We also predict poorer extinction recall and increased activation of fear-relevant brain regions in children who have experienced trauma, relative to children who have not experienced trauma. These predictions are based on prior fMRI studies of extinction recall in adults with PTSD showing poor extinction recall and heightened activation of fear-relevant brain regions across all experimental phases (i.e., fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) [see meta-analysis; 13]. We also performed several exploratory analyses (given in the Supplemental Material) to test for effects of age, symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression, parental psychopathology (symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression), and number of total traumas experienced on conditioned fear and neural activation.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included data collected from 44 children, ages 6–11 years (M = 8.8, SD = 1.45 years, 22 females), who completed a two-day fear extinction experiment. This sample has been previously reported on as a part of a validation study of the VR paradigm, and overall patterns of extinction recall in pre-adolescent children [31,32]. The effects of trauma exposure have not yet been reported on in this sample. Participants were recruited through local and online advertisements or referrals from local (Metro Detroit) healthcare providers. The sample was separated into trauma-exposed (n = 20) and unexposed control (n = 24) groups, as defined below (see Table I). Trauma-exposed and control groups were matched on sex, race distribution, IQ, and pubertal development. However, there was a group difference in age (p = 0.01). Effects of age were explored in all analyses and patterns associated with conditioned fear responding were examined in trauma and control groups, separately. Non-native English speakers and children with a history of brain injury with loss of consciousness or a neurological condition (e.g., epilepsy) were excluded from this study. Participants were also free of MRI contraindications, obsessive compulsive disorder, psychotic disorder, or significant learning disorder. All study procedures were approved by the Wayne State University Institutional Review Board (IRB) and conducted in agreement with IRB guidelines. All parents/guardians and children provided written informed consent or oral assent, respectively.

Table I.

Participant demographics.

| Variable | Trauma-exposed | Unexposed | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, M (SD) | 9.44 (1.3) | 8.33 (1.4) | 0.01 |

| Sex, n females (%) | 8 (40%) | 14 (58.3%) | 0.23 |

| Handedness, n right-handed (%) | 18 (90%) | 23 (96%) | 0.45 |

| Pubertal Development | |||

| Pre/early (Tanner stages 1–2), n (%) | 15 (75%) | 19 (79.2%) | 0.74 |

| Middle/late (Tanner stages 3–5), n (%) | 5 (25%) | 5 (20.8%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 9 (45%) | 12 (50%) | 0.36 |

| African American, n (%) | 6 (30%) | 10 (42%) | |

| Latino/Latina, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Asian American, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Native American, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other or not reported, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 1 (4%) | |

| Annual Income | |||

| Less than $10,000, n (%) | 3 (15%) | 2 (8.3%) | 0.45 |

| $10–20,000, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| $20–30,000, n (%) | 6 (30%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| $30–40,000, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| $40–50,000, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| $50–60,000, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| $60–80,000, n (%) | 2 (10%) | 4 (16.7%) | |

| $80–100,000, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| $100–120,000, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| $120–140,000, n (%) | 3 (15%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| $140–160,000, n (%) | 3 (15%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| $160–200,000, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.2%) | |

| $200–250,000, n (%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| IQ (KBIT-2), M (SD) | 105.6 (9.8) | 100.4 (17.9) | 0.24 |

| Trauma type$ | N/A | ||

| Domestic violence, witness n (%) | 6 (30%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Bullying/peer victimization, n (%) | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Domestic violence, victim, n (%) | 1 (5%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Illness/medically-related trauma, n (%) | 15 (75%) | 0 (0%) |

Abbreviations: KBIT-2: Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition

Six children reported exposure to more than one type of trauma, as defined on the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV.

2.2. Testing Procedures

The experimental procedures took place over the course of two subsequent days (i.e., Saturday, Sunday). On the first day, parents and children completed interviews and self-report questionnaires. Children subsequently completed fear conditioning and extinction learning in VR (details provided below), with a 10-minute break between phases. On the second day, participants returned to complete a test of extinction recall during fMRI scanning.

2.2.1. Trauma exposure

Childhood trauma exposure was measured using parent and/or child report of trauma exposure, as defined by the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index (RI) for DSM-IV [36,37]. Participants were classified as either trauma or control based on parent and/or children reports of the child’s exposure to a Criterion A trauma listed on the UCLA PTSD RI (see Table I). Structured clinical interviews were performed with parents and children, separately, by a trained postdoctoral research fellow or clinical psychology PhD student. Additional measures (e.g., PTSD symptoms, number of adversities, parent psychopathology) were collected and used in exploratory analyses (see Supplemental Material).

2.3. Fear Extinction Paradigm

The present study used a virtual reality Pavlovian fear extinction paradigm (see Figure 1), previously validated for use in children in our lab [31,32]. This paradigm was adapted from Milad et al. [18] using interpersonal stimuli that model common fear-inducing events in our Detroit sample (e.g., abuse, violence exposure). The experiment took place over two days and consisted of three phases: fear conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall. Day 1 was performed in the lab using a VR platform (see Supplemental Material) and day 2 was performed during fMRI scanning. On day one, participants underwent fear conditioning, during which one conditioned stimulus (CS+) was paired with an aversive white noise burst (500 ms, 95 dB), which served as the US). One CS was never paired with the US, creating a safety cue (i.e., CS−). The CSs were virtual adult males of varied races (i.e., Caucasian, African American, Asian) to match the demographics of our population. Conditioning occurred in one of two virtual contexts (CXT+), which was either an indoor or outdoor hallway. Participants were instructed to approach the CS using a joystick or an MR compatible response device. The joystick or response device was also used to capture behavioral and subjective markers of conditioned fear (see Section 2.4 Measures of Conditioned Fear and Supplemental Material). The subsequent extinction learning phase occurred in the other virtual context (CXT−), creating a safety context. During extinction, the CS+ was extinguished (i.e., displayed in the absence of the US) creating an extinguished cue (i.e., CS+E). The safety cue (i.e., CS−) was also presented throughout. On day two (24 hours later), participants returned to complete a test of extinction recall during fMRI scanning using an adapted version of the VR task in 2D. During extinction recall, participants encountered the CS+E and CS− in the CXT−. Fear conditioning consisted of 8 CS− trials, and 6 reinforced and 2 non-reinforced presentations of the CS+. Extinction learning consisted of 8 trials each of the CS+E and CS−. Extinction recall consisted of 8 non-reinforced trials each of the CS+E and CS−. Of note, the experiment also included an extinction renewal phase and a third CS (CS+U, unextinguished) that was included in the design to test the integrity of the fear memory if children showed good extinction recall. However, as we have reported previously, children showed poor extinction recall and therefore assessment of the subsequent phase was not warranted. Thus, the present study focused on the extinction recall phase. For further details on the experimental task, please see [31,32].

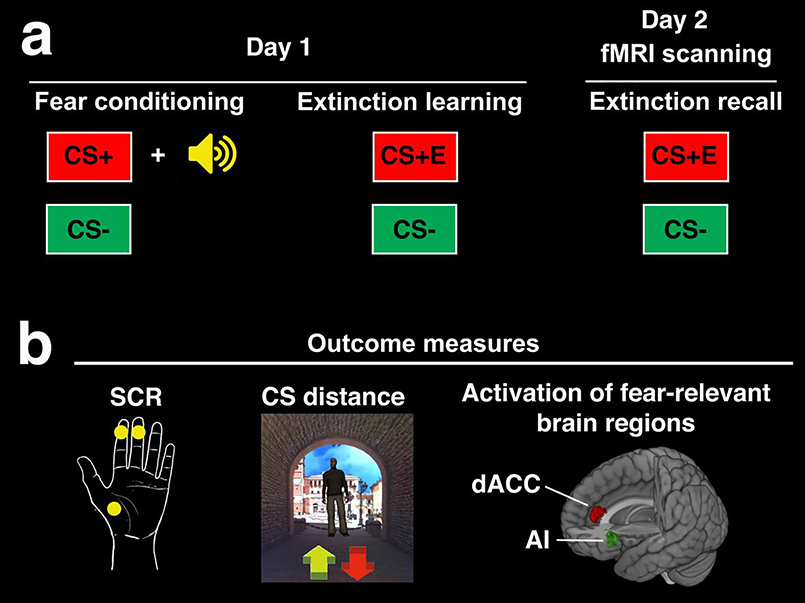

Figure 1. Experimental overview (a) and outcome measures.

(b). (a) Days 1 and 2 were conducted approximately 24 hours apart. Day 1 consisted of fear conditioning, during which one conditioned stimulus (CS+) was paired with a white noise burst, which served as the unconditioned stimulus (US). A second conditioned stimulus (CS−) served as the safety cue and was not paired with the US. During the subsequent extinction learning phase, the CS+ was extinguished (i.e., presented in the absence of the US) and is thus referred to as the extinguished cue (CS+E). Day 2 was conducted during fMRI scanning to examine activation of fear-relevant brain regions during extinction recall. We focused on activation of fear-relevant brain regions based on our prior research showing poor extinction recall, as measured by expression of conditioned fear to the CS+E, coupled with activation of fear-relevant brain regions in pre-adolescent children. (b) Conditioned fear responses to the CS+ or CS+E and CS− were measured throughout each phase using skin conductance responses (SCR) and distance kept from the CS (virtual meters). Of note, for SCR, the third palm electrode was used as a ground during fMRI scanning only. Fear and US expectancy ratings were also collected during each phase for use in exploratory analyses (see Supplemental Material). We also measured activation in fear-relevant brain regions during extinction recall. In particular, we focused on the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and anterior insula (AI) given that these regions consistently showed activation during extinction recall in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies in adults [38] and that adults with PTSD show a consistent pattern of overactivation in these regions during extinction recall and other phases [13].

2.4. Measures of Conditioned Fear

Conditioned fear responses to the CS+/CS+E and the CS− were measured throughout each phase using (1) SCRs and (2) distance kept from the CS in the virtual environment. SCR was measured throughout the experiment using two electrodes on the area of skin between the first and second phalanges of the second and third digits of the non-dominant hand. A third ground electrode was used during fMRI scanning. SCR data were collected and analyzed using an MP160 system and AcqKnowledge software v.5 (BIOPAC Systems, Inc). SCRs were calculated as the maximum response within a 0.5–4.5 s window following stimulus onset and controlling for a baseline period of 2 s prior to CS onset. SCRs were square root transformed to normalize the distributions across participants and the minimal response criterion was 0.02 μS. For paired CS-US trials during fear conditioning, we used a smaller window size (0–3.5 s latency) to assess the level of conditioned responding in anticipation of the aversive US separate from unconditioned responses to the noise bursts, themselves. Of note, this may have excluded peak SCRs to the CS+ that occurred after this window. For further details see [32]. Distance kept from the CS (forward-to-backward) was recorded as a measure of behavioral avoidance. Overall response to the CS+ or CS+E and CS− were calculated during each phase (fear conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall). We also calculated conditioned fear responding during the first (early) and second half (late) of each phase to assess effects of trauma over time (i.e., early vs. late).

2.5. fMRI

2.5.1. fMRI data acquisition

A subset of participants (n = 35, 18 trauma-exposed, 17 controls, χ(1)2 = 2.46, p = 0.11) underwent fMRI scanning during extinction recall. FMRI data were collected during extinction recall given our a priori interest in this phase. FMRI data were collected using a 2D version of the task with a research-dedicated Siemens 3T MAGNETOM Verio system (MRI Research Facility, Wayne State University). Extinction recall took place at the end of the scan period to mitigate effects of a novel scanning environment and we previously demonstrated no difference in conditioned fear responding for this experimental task inside vs. outside of the scanner [31]. A multi-echo/multiband (ME/MB) echo-planar imaging sequencing was used to acquire whole-brain blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) functional images. The following sequence was used for fMRI data collection: 51 slices, 186 mm field of view (FOV), 64 × 65 matrix size yielding 2.9 mm isotropic resolution, in-plane GRAPPA acceleration factor 2, flip angle (FA) = 83 degrees, repetition time (TR) = 1.5 s, and echo time triplet (TEs) = 15, 31, 46 ms. A magnetization prepared rapid acquisition GRE (MP-RAGE) sequence was also collected within the same scan session for fMRI image co-registration: 128 slices, 256 mm FOV, 384 × 384 matrix size yielding 0.7 × 0.7 × 1.3 mm resolution, in-plane GRAPPA acceleration factor 2, FA = 9 degrees, TR = 1.68 s, TE = 3.51 ms.

2.5.2. fMRI processing and analysis

ME-ICA software (v3, beta 1: https://bitbucket.org/prantikk/mei-ca) was used for fMRI preprocessing and denoising. Following ME-ICA, head motion, as measured by framewise displacement, was relatively low across the sample (M = 0.47, SD = 0.38 mm). Following preprocessing, SPM8 was used for first and second level fMRI analyses. Experimental conditions (CS+E, CS+U, CS−, context) were modeled at the first level using an event-related design, and analyses focused on neural response to the CS+E following our prior work [31]. To examine neural response to the safety cue and test for specificity of results as compared to the CS+E, we also examined neural response to the CS−.

2.6. Statistical analyses

2.6.1. Conditioned fear

Overall patterns of conditioned fear (SCRs, CS distance) for each phase are presented in Figure S1 and also described in our previous work [31,32]. Our main analyses focused on effects of childhood trauma. First, we performed a 2 (group: control, trauma) x 2 (CS-type: CS+, CS−) x 2 (phase: fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) analysis of variance (ANOVA) for each conditioned fear measure (i.e., SCR amplitude, CS distance) to test for main effects or interactions of trauma exposure across the experiment. Next, we performed separate 2 (group: control, trauma) x 2 (CS-type: CS+, CS−) x 2 (time: early, late) ANOVAs for each phase (fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) and conditioned fear measure (SCR amplitude, CS distance), to test for within-phase effects of trauma exposure. Main effects and interactions were considered significant at p < 0.05 (two-tailed), and Hynh-Feldt correction was applied in the case of sphericity violation via Mauchly’s test. Post-hoc t-tests were performed following significant main effects or interactions. All statistical analyses were performed in SPSS v.26 (IBM Corp). Given the observed group difference in age (see Table I), we examined the impact of age on results in follow-up analyses and effects of time or CS-type were explored in trauma and control groups, separately. Various exploratory analyses were performed using Pearson Bivariate Correlation, including effects of age, number of adversities, parent psychopathology (symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression), and child psychopathology (symptoms of PTSD, anxiety, depression; see Supplemental Material). Potential outliers were detected using |Z| > 3. One child in the control group kept excess distance from both the CS+E and CS− during extinction learning. Reported results did not change when removing this participant

2.6.2. FMRI

Statistical analyses on fMRI data were performed using a region of interest (ROI) approach targeting the main regions of fear neural circuitry [39]. In particular, we focused on the AI and dACC given that these regions consistently showed activation during extinction recall in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies in adults [38] and that adults with PTSD show a consistent pattern of overactivation in these regions during extinction recall and other phases [13]. We previously reported activity in these regions in response to the CS+E during a test of extinction recall in children, which corresponded with conditioned fear responding [31]. These data suggest that, overall, children show activity in these fear-relevant structures during extinction recall. Interestingly, although the amygdala is often considered a core component of fear neural circuitry, activity in the amygdala is not consistently reported in fMRI studies of fear conditioning or extinction [38,40]. Nonetheless, we performed exploratory analyses on the amygdala as an additional ROI (see Supplemental Material). Although fear extinction neural circuitry appears to be immature during childhood, we also performed exploratory analyses on ROIs implicated in fear extinction, including the hippocampus and vmPFC [16,41] (see Supplemental Material). Our main analyses tested for group differences (trauma, control) in BOLD response to the (1) CS+E or (2) CS− during extinction recall, using two separate two-sample t-tests in SPM8. Group differences were evaluated within ROIs (10 mm radii spheres) using regions defined in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies on extinction learning and recall adults [38], using small volume familywise error correction (pFWE < 0.05, plus 5 voxel minimum). BOLD response to the CS+E or CS− was subsequently extracted from peak regions of group difference using 6 mm radii spheres and used for visualization of results (see Figure 4). These values were also submitted to Pearson Bivariate Correlation in SPSS for exploratory analyses, such as correlations between BOLD response and symptoms of PTSD (see Supplemental Material).

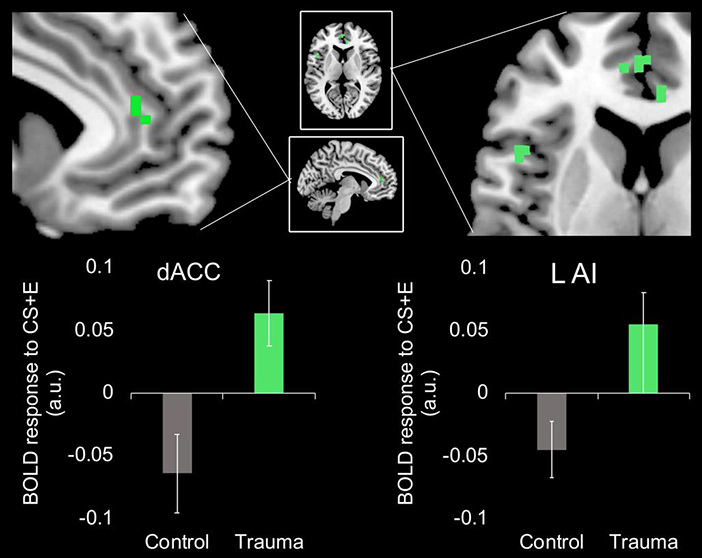

Figure 4. Effects of childhood trauma exposure on activation of fear-relevant brain regions during extinction recall.

Children who have experienced trauma, shown in green, show greater activation in the left AI and the dACC to the previously extinguished cue (CS+E) relative to children who have not experienced trauma (i.e., controls), shown in grey. Results significant using small-volume family-wise error correction (pFWE < 0.05) using regions defined in a meta-analysis of fMRI studies on extinction learning and recall adults [38]. Abbreviations: CS+E, previously extinguished conditioned stimulus; dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; L AI, left anterior insula; BOLD, blood-oxygen-level-dependent.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of trauma exposure on conditioned fear measures (SCRs, CS distance)

3.1.1. Group (control, trauma) x CS-type (CS+ or CS+E, CS−) x phase (fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) ANOVAs

A 2 (group: control, trauma) x 2 (CS-type: CS+, CS−) x 2 (phase: fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) ANOVA revealed a significant group x CS-type interaction (F(1,36) = 4.16, p = 0.049, ηp2 = 0.1) on SCRs. This interaction appeared to be driven by overall higher SCRs to the CS+ relative to the CS in the trauma (but not control) group. However, the main effect of CS-type within the trauma group did not reach significance, (F(1,15) = 3.39, p = 0.085, ηp2 = 0.18). There were no other significant main effects or interactions for SCRs. For CS distance, the 2 (group: control, trauma) x 2 (CS-type: CS+, CS−) x 2 (phase: fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall) ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of phase (F(1.39, 54.27) = 19.42, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.332). This main effect was driven by children keeping more distance from the CS during extinction recall, followed by fear conditioning, followed by extinction learning (all ts > 2.3, ps < 0.05). The overall large CS distance during extinction recall may be due to the change in response device from Day 1 to Day 2 (i.e., joystick to the MR-compatible SR box). There were no other significant main effects or interactions for CS distance. Figure 2 displays overall patterns of conditioned fear across initial learning sessions, by group (control, trauma). Of note, overall patterns (i.e., independent of trauma exposure) have been described previously [31,32].

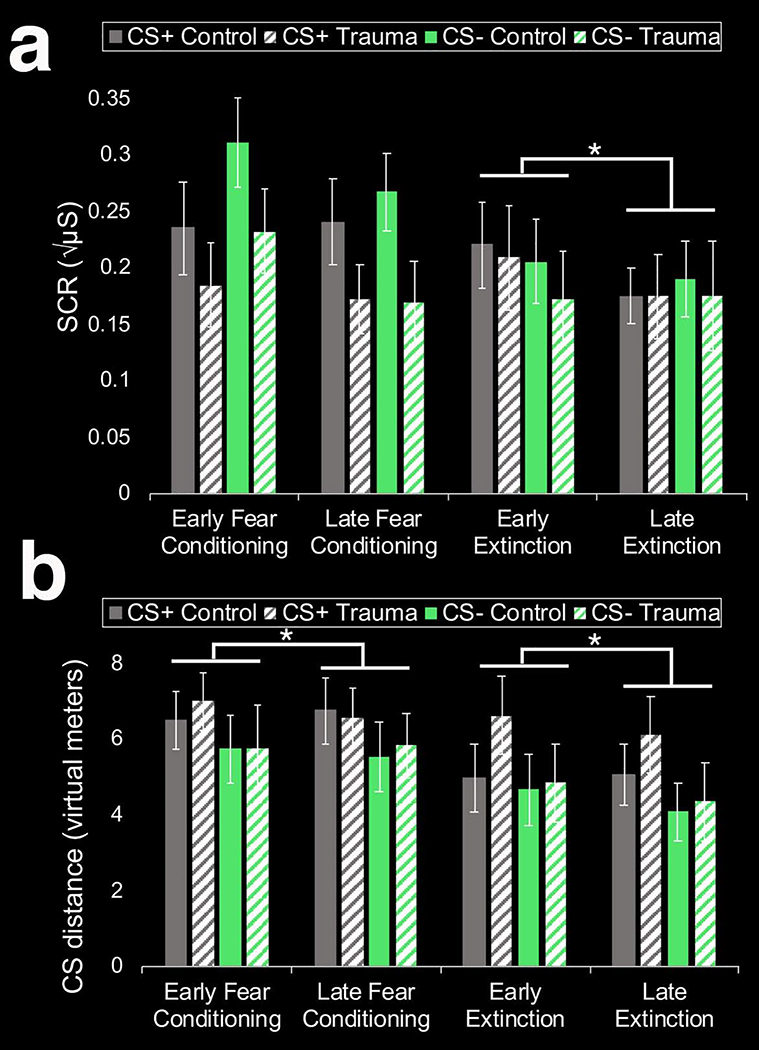

Figure 2. Overall patterns of conditioned fear across initial learning phases (fear conditioning, extinction learning), measured by SCR (a) or distance from the CS (b), by group (control, trauma).

(a) The overall patterns (i.e., independent of trauma exposure) across phases have been previously described [31,32]. Abbreviations: SCR, skin conductance responses; CS, conditioned stimulus; CS+, conditioned stimulus paired with the US and subsequently underwent extinction; US, unconditioned stimulus; CS−, safety cue that was not paired with the US. *p < 0.05, paired sample t-test.

3.1.2. Group (control, trauma) x CS-type (CS+E or CS+ vs. CS−) x time (early, late) ANOVA

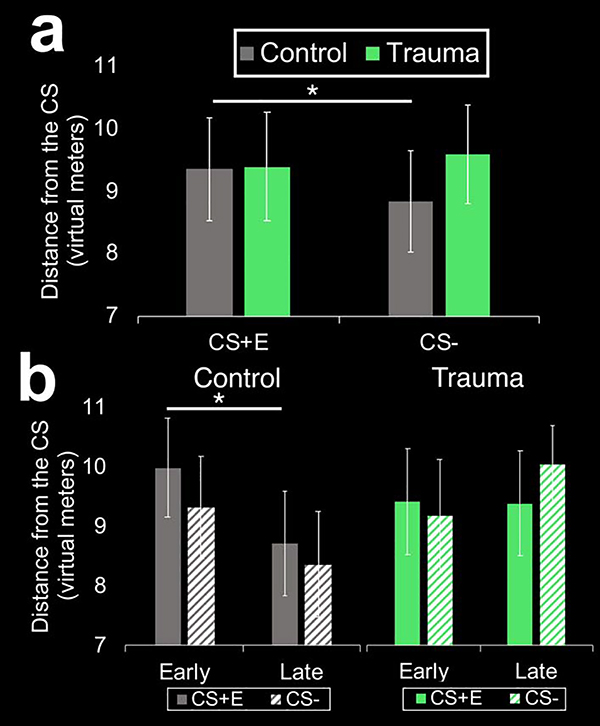

A 2 (group: control, trauma) x 2 (CS-type: CS+, CS−) x time (early, later) ANOVA found no significant main effects or interactions on SCRs during fear conditioning (Fs < 2.9, ps > 0.09). During extinction learning, there was a significant main effect of time (F(1,40) = 4.33, p = 0.044, ηp2 = 0.1) such that overall, SCRs decreased over time (see Figure 2A). There was also a significant main effect of time on SCRs during extinction recall (F(1,36) = 8.9, p = 0.005, ηp2 = 0.2), such that overall SCRs increased over time. There were no significant main effects of group or CS-type, and no significant interactions among group, CS-type, or time in SCRs during any phase. For CS distance, the main effect of time was significant for both fear conditioning (F(1,41) = 5.5, p = 0.023, ηp2 = 0.12) and extinction learning (F(1,40) = 8.79, p = 0.005 ηp2 = 0.18), such that overall, children approached the CS over time (see Figure 2B). There were no significant main effects of group, group x CS-type interactions, or group x time interactions for SCRs or CS distance during initial learning phases (i.e., fear conditioning, extinction learning). During extinction recall, however, the group x time (F(1,40) = 5.25, p = 0.027, ηp2 = 0.12) and group x CS-type interactions (F(1,40) = 5.29, p = 0.025, ηp2 = 0.12) reached significance for CS distance. The group x CS-type interaction was driven by control youth keeping more distance from the CS+E relative to the CS− (t(22) = 2.35, p = 0.025) whereas trauma-exposed youth kept distance from both cues during extinction recall (p = 0.34; see Figure 3A). The group x time interaction was driven by children in the control group approaching the CS+E over the course of extinction recall (i.e., early vs. late recall; t(22) = 2.67, p = 0.014; see Figure 3B). Trauma-exposed children, in contrast, failed to approach the CS+E over the course of extinction recall (t(18) = 0.12, p = 0.91). Overall, the time x CS-type interaction also reached significance (F(1,40) = 3.87, p = 0.028, ηp2 = 0.11) for CS distance during extinction recall. Post hoc t-tests suggested that the time x CS-type interaction was driven by overall, children approaching the CS+E (t(41) = 2.3, p = 0.027) but not the CS− (t(41) = 0.3, p = 0.76) over the course of extinction recall.

Figure 3. Effects of childhood trauma on fear-related behavior during extinction recall.

(a) Children in the control group kept more distance from the previously extinguished cue (CS+E) relative to the safety cue (CS−) during a test of extinction recall whereas trauma-exposed youth kept distance from both cues. (b) Children in the control group approached the CS+E over the course of extinction recall (i.e., early to late recall), whereas trauma-exposed children failed to show this approach behavior to the CS+E. *p < 0.05

3.2. Effects of trauma exposure on activation of fear-relevant brain regions

Relative to trauma-naïve controls, children exposed to trauma showed higher response in the left AI (xyz = −45, 15, 9, Z = 3.62, 5 voxels, pFWE = 0.032) and the dACC (xyz = −7, 43, 12, Z = 4.7, 6 voxels, pFWE = 0.001) to the CS+E during extinction recall (see Figure 4). These results remained significant when controlling for age. There were no ROIs showing the opposite pattern of greater neural response to the CS+E in controls relative to trauma-exposed children. There were also no ROIs showing group differences in activation to the CS− during extinction recall.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to report effects of trauma exposure on extinction recall in children. Using both autonomic (SCRs) and behavioral (distance from the CS) measures of conditioned fear, we found relatively limited main effects of trauma exposure on conditioned fear across all experimental phases (i.e., fear conditioning, extinction learning, extinction recall). While trauma exposure was not associated with differences in SCRs, there was an effect of trauma exposure on fear-related behavior during extinction recall. In particular, children who experienced trauma kept more distance from both the previously extinguished cue (CS+E) and the safety cue (CS−) as compared to children in the control group. In addition, children who experienced trauma kept more distance from the CS+E over the course of extinction recall whereas children who did not experience trauma approached the cue over time. These fear-related behavioral patterns were accompanied by increased activation in fear-relevant brain regions (i.e., dACC, AI) during extinction recall in trauma-exposed youth relative to unexposed controls. Interestingly, these patterns are similar to those reported in studies of contextual fear renewal in healthy adults [34], and adults with PTSD during extinction recall [13]. Together, these findings demonstrate alterations in fear-related behavior and overactivation of fear-relevant brain regions in trauma-exposed youth during a test of extinction recall. Overactivation of fear-relevant brain regions may interfere with the typical development of neural circuitry supporting extinction recall in healthy adults (e.g., vmPFC) [17,18]. These patterns suggest that trauma-exposed children are able to learn fear associations and subsequently extinguish fear within-session. However, when later encountering those cues, the fear memory prevails, suggesting that fear memories are resistant to extinction over time. Taken together, alterations in fear-related behavior and activation of fear-relevant brain structures may be important for understanding the link between childhood trauma exposure and heightened risk of fear-based disorders.

Interestingly, the acquisition and within-session extinction of conditioned fear were intact across trauma-exposed and trauma-naïve groups on Day 1. On Day 2, however, there was a group difference in fear-related behavior during a test of extinction recall. There were no group differences during extinction recall in SCRs or in subjective measures of fear (the latter results reported in the Supplemental Material). The divergent effects of childhood trauma exposure on different measures of conditioned fear during extinction recall is in line with the notion that different outcome measures capture different dimensions of fear, e.g., behavioral (CS distance), autonomic (SCRs), affective (valence ratings), and cognitive (US-expectancy) responses [42,43]. Divergent patterns of responses across different conditioned fear measures has been reported in previous work, for example, in adults with PTSD [43]. Thus, our data suggest that childhood trauma exposure may have distinct effects on different dimensions of fear. One advantage of the present study is that we also assessed fear-related behavior, measured by distance from the CS. Behavioral avoidance of the CS may capture the behavioral domain of fear and PTSD pathology that is not commonly measured in fear conditioning paradigms. We found that trauma-exposed children kept more distance from the CS+E and the CS− during extinction recall and failed to approach the CS+E over the course of extinction recall. Trauma-naïve children, in contrast, kept more distance from the CS+E as compared to the CS− but approached the CS+E over the course of recall. The lack of approach behavior and difficulty in discriminating between the CS+E and CS− during extinction recall may suggest an avoidant behavioral pattern in trauma-exposed youth. Avoidance is considered to be a core feature of PTSD, and avoidant symptoms have specifically been linked to heightened activation of fear circuitry (e.g., amygdala, insula) during conditioning and extinction learning [44]. Avoidance is also an important symptom cluster in PTSD in children, in particular, and behavioral avoidance has been shown to predict chronicity of PTSD across childhood [45]. Thus, the observed pattern of behavioral avoidance coupled with heightened activation of fear circuitry in trauma-exposed children in the present study may reflect heightened susceptibility to PTSD or other fear-based disorders. Links among childhood trauma exposure, avoidance, and psychopathology have been demonstrated in prior studies. For instance, a recent study in 432 adults found that experiential avoidance (e.g., attempts to avoid certain thoughts, memories or feelings) meditates the link between childhood trauma and symptoms of PTSD [46]. Taken together, our data suggest a pattern of behavioral avoidance during extinction recall in trauma-exposed children. Future studies should test whether this pattern is associated with the future development of anxiety or PTSD symptoms during adolescence or adulthood.

In addition to behavioral effects, trauma-exposed children exhibited greater activation in brain regions involved in the promotion of fear signal detection, including the dACC and AI, during extinction recall. Interestingly, a similar pattern of activation was reported in a previous study of adults with PTSD such that patients with PTSD showed greater activation in the dACC and the AI during extinction recall as compared to trauma-exposed controls without PTSD [12]. These patterns were replicated in a recent meta-analysis of fMRI studies in PTSD, and suggest that heightened activation of fear-relevant brain regions (e.g., dACC and AI) may be evident across all experimental phases (i.e., fear conditioning extinction learning, extinction recall)[13]. The authors of the meta-analysis suggest that these activation patterns may contribute to a prolonged and exaggerated threat response that characterizes PTSD [13]. Thus, heightened activity of fear-relevant brain regions observed here in trauma-exposed children may reflect increased vulnerability to the development of psychopathology.

In addition to contributing to exaggerated threat responding, overactivation of fear neural circuitry in trauma-exposed youth may inhibit the typical development of fear extinction neural circuitry. Extinction recall is intact in healthy young adults and has been shown to depend on vmPFC-based circuitry [17,18]. Adults with PTSD demonstrate poor extinction recall (e.g., heightened SCRs to the CS+E), overactivation of fear neural circuitry, and lower activation in brain regions supporting extinction recall, such as the vmPFC [13]. Importantly, we previously demonstrated that overall, pre-adolescent children show poor extinction recall, which suggests that the capacity to recall extinction learning develops between childhood and adulthood [31]. Exposure to trauma during childhood may impair the typical development of fear extinction neural circuitry during adolescence, and thus inhibit trauma-exposed youth from developing the ability to successfully recall extinction learning. This hypothesis is fitting with data showing protracted development of vmPFC-based circuitry through adolescence, including top-down vmPFC-amygdala connections [33] and connections between the vmPFC and hippocampus [47]. Further, a study by Keding et al. [48] reported lower volume of the vmPFC in youth with PTSD relative to healthy youth. Altered development of fear extinction neural circuitry in trauma-exposed youth may lead to increased susceptibility to fear-based disorders – a hypothesis that should be tested in future work.

Our results in 6–11 year-olds have both similarities and differences to those reported in prior studies of childhood trauma exposure and fear conditioning [27,29,30]. In 6–18 year olds, McLaughlin et al. reported blunted SCRs to the CS+ and poor differentiation between the threat and safety cues in trauma-exposed children relative to controls during fear conditioning and extinction [29,30]. In a younger sample of 4–7 year olds, there were no main effects of trauma exposure on SCRs during fear conditioning, but there was an age x trauma interaction for SCR amplitude to the CS+ during fear conditioning [27]. In particular, this effect was driven by an age-related increase in SCR amplitude to the CS+ in the trauma-naïve (but not trauma-exposed) group [27]. Similar to the study by Machlin et al. (2019), we found no main effect of trauma exposure on SCRs during fear conditioning, but we did find an effect of trauma exposure on fear-related behavior during extinction recall.

This study is novel because it examined extinction recall and activation of fear-relevant brain regions in children who have experienced trauma and a comparison group of trauma-naïve children. Although the study had several strengths, including assessment of various measures of conditioned fear (SCRs, behavioral, neural activation), the limitations warrant mention. First, fMRI data were collected during extinction recall only. Future studies should test whether the observed heightened activation of fear-relevant brain regions in trauma-exposed children relative to unexposed controls during extinction recall also extend to different phases (i.e., fear conditioning, extinction learning), as observed in studies of adults with PTSD [13]. In addition, although we took steps to reduce the potential influence of the novel scan environment on fear responding (e.g., mock scanner pre-training, extinction recall task performed at the end of the scan), we cannot rule out the potential impact of the scan environment on contextual processing during the task. Next, the relatively limited sample size precluded our power to detect effects and interactions with other important variables, such as age. Future studies with larger longitudinal samples are needed to fully examine patterns of age-related change and effects of other important variables (e.g., caregiver support) [see 47]. Future studies in adolescents should also consider examining the effects of pubertal development and/or pubertal steroid hormones, in light of emerging data in adults linking estradiol levels with extinction recall, which may explain the elevated risk of PTSD in females relative to males [50]. In addition, the trauma group consisted of a large number of children with medically related trauma who were recruited from healthcare providers. Greater involvement with healthcare may be associated with enhanced psychosocial support from medical providers (e.g., nurses), which may buffer trauma-exposed children from the expression of psychopathology. This may explain the fact that overall, trauma and control groups did not differ in current anxiety and depressive symptoms (see Supplemental Material). Future work should evaluate different forms of trauma (e.g., community violence) and the impact of potential moderating variables (e.g., psychosocial support, parent-child relationship). Nonetheless, results of the present study suggest that early interventions that target fear-related behavior and overactivation of fear-circuitry, or augment the development of fear extinction neural circuitry, may be explored to prevent the emergence of psychopathology among trauma-exposed children.

4.1. Conclusions

The present study reports altered fear-related behavior coupled with increased activation of fear-relevant brain regions (dACC, AI) during extinction recall in trauma-exposed children relative to unexposed children. Given that alterations in fear extinction are commonly reported in anxiety disorders and PTSD in adults and in youth, exposure to childhood trauma may alter fear extinction and/or functioning of fear-relevant neural circuitry in a way that increases vulnerability to fear-based disorders. Further research is needed to direct targeted intervention strategies for trauma-exposed youth to prevent the development of psychopathology.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Childhood trauma is a leading risk factor for fear-based disorders

We examined fear and neural activation in trauma-exposed and trauma-naïve children

No group differences in fear during fear conditioning or extinction learning

During extinction recall, however, trauma linked to enhanced fear-related behavior

Trauma also linked to hyperactivity of fear-related brain regions during recall

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Shelley Paulisin, Sajah Fakhoury, Limi Sharif, Xhenis Brahimi, Farah Sheikh, Suzanne Brown, Ph.D., Laura M. Crespo, Ph.D., Kelsey Sala-Hamrick, Ph.D., Klaramari Gellci, Richard Genik, Ph.D., and Pavan Jella, M.S., of Wayne State University (WSU) for assistance in participant recruitment and data collection. Thank you also to the adolescents and families who generously shared their time to participate in this study. This work was supported, in part, by the WSU Department of Pharmacy Practice and by the American Cancer Society (14-238-04-IRG to CR). Dr. Rabinak is supported by NIH National Institute of Mental Health grant R61 MH111935. Dr. Marusak is supported by NIH National Institute of Mental Health grant K01 MH119241.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Hinesley J, Chan RF, Aberg KA, Fairbank JA, van den Oord EJCG, Costello EJ, Association of Childhood Trauma Exposure With Adult Psychiatric Disorders and Functional Outcomes, JAMA Netw. Open 1 (2018) e184493 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders., Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67 (2010) 113–123. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kaufman J, Plotsky PM, Nemeroff CB, Charney DS, Effects of early adverse experiences on brain structure and function: clinical implications, Biol. Psychiatry 48 (2000) 778–790. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)00998-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson D, Webb E, Janson S, Burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries, Lancet. 373 (2009) 68–81. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61706-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Copeland WE, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ, Traumatic Events and Posttraumatic Stress in Childhood, Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 64 (2007) 577–584. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC, Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents, J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry (2013). 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Finkelhor D, Ormrod R, Turner H, Hamby SL, The Victimization of Children and Youth: A Comprehensive, National Survey, Child Maltreat. 10 (2005) 5–25. 10.1177/1077559504271287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Graham BM, Milad MR, The study of fear extinction: implications for anxiety disorders, Am. J. Psychiatry 168 (2011) 1255–1265. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11040557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Duits P, Cath DC, Lissek S, Hox JJ, Hamm AO, Engelhard IM, Van Den Hout MA, Baas JMP, Updated meta-analysis of classical fear conditioning in the anxiety disorders, Depress. Anxiety 32 (2015) 239–253. 10.1002/da.22353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Garfinkel SN, Abelson JL, King AP, Sripada RK, Wang X, Gaines LM, Liberzon I, Impaired Contextual Modulation of Memories in PTSD: An fMRI and Psychophysiological Study of Extinction Retention and Fear Renewal, J. Neurosci 34 (2014) 13435–13443. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4287-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jovanovic T, Norrholm SD, Blanding NQ, Davis M, Duncan E, Bradley B, Ressler KJ, Impaired fear inhibition is a biomarker of PTSD but not depression, Depress. Anxiety 27 (2010) 244–251. 10.1002/da.20663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Milad MR, Pitman RK, Ellis CB, Gold AL, Shin LM, Lasko NB, Zeidan MA, Handwerger K, Orr SP, Rauch SL, Neurobiological Basis of Failure to Recall Extinction Memory in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Biol. Psychiatry 66 (2009) 1075–1082. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Suarez-Jimenez B, Albajes-Eizagirre A, Lazarov A, Zhu X, Harrison BJ, Radua J, Neria Y, Fullana MA, Neural signatures of conditioning, extinction learning, and extinction recall in posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies, Psychol. Med (2019). 10.1017/S0033291719001387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liberzon I, Abelson JL, Context Processing and the Neurobiology of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, Neuron. 92 (2016) 14–30. 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Åhs F, Kragel PA, Zielinski DJ, Brady R, LaBar KS, Medial prefrontal pathways for the contextual regulation of extinguished fear in humans, Neuroimage. 122 (2015) 262–271. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kalisch R, Korenfeld E, Stephan KE, Weiskopf N, Seymour B, Dolan RJ, Context-dependent human extinction memory is mediated by a ventromedial prefrontal and hippocampal network., J. Neurosci 26 (2006) 9503–9511. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2021-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Milad MR, Quinn BT, Pitman RK, Orr SP, Fischl B, Rauch SL, Thickness of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in humans is correlated with extinction memory., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102 (2005) 10706–10711. 10.1073/pnas.0502441102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Milad MR, Wright CI, Orr SP, Pitman RK, Quirk GJ, Rauch SL, Recall of Fear Extinction in Humans Activates the Ventromedial Prefrontal Cortex and Hippocampus in Concert, Biol. Psychiatry 62 (2007) 446–454. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McGuire JF, Orr SP, Essoe JKY, McCracken JT, Storch EA, Piacentini J, Extinction learning in childhood anxiety disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder: implications for treatment, Expert Rev. Neurother (2016). 10.1080/14737175.2016.1199276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Geller DA, McGuire JF, Orr SP, Pine DS, Britton JC, Small BJ, Murphy TK, Wilhelm S, Storch EA, Fear conditioning and extinction in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder, Ann. Clin. Psychiatry 29 (2017) 17–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jovanovic T, Nylocks KM, Gamwell KL, Smith A, Davis TA, Norrholm SD, Bradley B, Development of fear acquisition and extinction in children: Effects of age and anxiety, Neurobiol. Learn. Mem 113 (2014) 135–142. 10.1016/j.nlm.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].van Rooij SJH, Smith RD, Stenson AF, Ely TD, Yang X, Tottenham N, Stevens JS, Jovanovic T, Increased activation of the fear neurocircuitry in children exposed to violence, Depress. Anxiety n/a (2020). 10.1002/da.22994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Cisler JM, Privratsky A, Smitherman S, Herringa RJ, Kilts CD, Large-scale brain organization during facial emotion processing as a function of early life trauma among adolescent girls, NeuroImage Clin 17 (2018) 778–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Marusak HA, Martin KR, Etkin A, Thomason ME, Childhood trauma exposure disrupts the automatic regulation of emotional processing, Neuropsychopharmacology. 40 (2015) 1250–1258. 10.1038/npp.2014.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Herringa RJ, Birn RM, Ruttle PL, Burghy CA, Stodola DE, Davidson RJ, Essex MJ, Childhood maltreatment is associated with altered fear circuitry and increased internalizing symptoms by late adolescence, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1310766110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Thomason ME, Marusak HA, Tocco MA, Vila AM, McGarragle O, Rosenberg DR, Altered amygdala connectivity in urban youth exposed to trauma, Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci 10 (2014). 10.1093/scan/nsv030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Machlin L, Miller AB, Snyder J, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Differential Associations of Deprivation and Threat With Cognitive Control and Fear Conditioning in Early Childhood, Front. Behav. Neurosci 13 (2019) 1–14. 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, McCarry TW, Nurse M, Gilhooly T, Millner A, Galvan A, Davidson MC, Eigsti IM, Thomas KM, Freed PJ, Booma ES, Gunnar MR, Altemus M, Aronson J, Casey BJ, Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation, Dev. Sci (2010). 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Gold AL, Duys A, Lambert HK, Peverill M, Heleniak C, Shechner T, Wojcieszak Z, Pine DS, Maltreatment Exposure, Brain Structure, and Fear Conditioning in Children and Adolescents., Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol 41 (2016) 1956–1964. 10.1038/npp.2015.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Jenness JL, Miller AB, Rosen ML, McLaughlin KA, Extinction Learning as a Potential Mechanism Linking High Vagal Tone with Lower PTSD Symptoms among Abused Youth, J. Abnorm. Child Psychol 47 (2019) 659–670. 10.1007/s10802-018-0464-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Marusak HA, Peters C, Hehr A, Elrahal F, Rabinak CA, Poor between-session recall of extinction learning and hippocampal activation and connectivity in children, Neurobiol. Learn. Mem (2018). 10.1016/j.nlm.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Marusak HA, Peters CA, Hehr A, Elrahal F, Rabinak CA, A novel paradigm to study interpersonal threat-related learning and extinction in children using virtual reality, Sci. Rep 7 (2017). 10.1038/s41598-017-17131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Bouwmeester H, Smits K, Van Ree JM, Neonatal development of projections to the basolateral amygdala from prefrontal and thalamic structures in rat, J. Comp. Neurol (2002). 10.1002/cne.10321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Hermann A, Stark R, Milad MR, Merz CJ, Renewal of conditioned fear in a novel context is associated with hippocampal activation and connectivity, Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci (2016). 10.1093/scan/nsw047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pittig A, van den Berg L, Vervliet B, The key role of extinction learning in anxiety disorders: behavioral strategies to enhance exposure-based treatments., Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 29 (2016) 39–47. 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Birmaher B, Khetarpal S, Brent D, Cully M, Balach L, Kaufman J, Neer SMK, The Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders (SCARED): Scale construction and psychometric characteristics, J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry (1997). 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Steinberg AM, Brymer MJ, Kim S, Briggs EC, Ippen CG, Ostrowski SA, Gully KJ, Pynoos RS, Psychometric Properties of the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index: Part I, J. Trauma. Stress 26 (2013) 1–9. 10.1002/jts.21780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fullana MA, Albajes-Eizagirre A, Soriano-Mas C, Vervliet B, Cardoner N, Benet O, Radua J, Harrison BJ, Fear extinction in the human brain: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies in healthy participants, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev (2018). 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Quirk GJ, Mueller D, Neural mechanisms of extinction learning and retrieval., Neuropsychopharmacology. 33 (2008) 56–72. 10.1038/sj.npp.1301555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fullana MA, Harrison BJ, Soriano-Mas C, Vervliet B, Cardoner N, Àvila-Parcet A, Radua J, Neural signatures of human fear conditioning: An updated and extended meta-analysis of fMRI studies, Mol. Psychiatry (2016). 10.1038/mp.2015.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Phelps EA, Human emotion and memory: Interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex, Curr. Opin. Neurobiol 14 (2004) 198–202. 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Lonsdorf TB, Menz MM, Andreatta M, Fullana MA, Golkar A, Haaker J, Heitland I, Hermann A, Kuhn M, Kruse O, Meir Drexler S, Meulders A, Nees F, Pittig A, Richter J, Römer S, Shiban Y, Schmitz A, Straube B, Vervliet B, Wendt J, Baas JMP, Merz CJ, Don’t fear ‘fear conditioning’: Methodological considerations for the design and analysis of studies on human fear acquisition, extinction, and return of fear, Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 77 (2017) 247–285. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Blechert J, Michael T, Vriends N, Margraf J, Wilhelm FH, Fear conditioning in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence for delayed extinction of autonomic, experiential, and behavioural responses., Behav. Res. Ther 45 (2007) 2019–2033. 10.1016/j.brat.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Sripada R, Garfinkel S, Liberzon I, Avoidant symptoms in PTSD predict fear circuit activation during multimodal fear extinction, Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 (2013) 672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Feldman R, Vengrober A, Ebstein R, Affiliation buffers stress: cumulative genetic risk in oxytocin-vasopressin genes combines with early caregiving to predict PTSD in war-exposed young children, Transl. Psychiatry. 4 (2014) e370–e370. 10.1038/tp.2014.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Hosseini Ramaghani N, Rezaei F, Sepahvandi MA, Gholamrezaei S, Mirderikvand F, The mediating role of the metacognition, time perspectives and experiential avoidance on the relationship between childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, Eur. J. Psychotraumatol 10 (2019) 1648173 10.1080/20008198.2019.1648173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Calabro FJ, Murty VP, Jalbrzikowski M, Tervo-Clemmens B, Luna B, Development of Hippocampal–Prefrontal Cortex Interactions through Adolescence, Cereb. Cortex (2019). 10.1093/cercor/bhz186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Keding TJ, Herringa RJ, Abnormal structure of fear circuitry in pediatric post-traumatic stress disorder, Neuropsychopharmacology. (2015). 10.1038/npp.2014.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].McLaughlin KA, Colich NL, Rodman AM, Weissman DG, Mechanisms linking childhood trauma exposure and psychopathology: a transdiagnostic model of risk and resilience., BMC Med. 18 (2020) 96 10.1186/s12916-020-01561-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Garcia NM, Walker RS, Zoellner LA, Estrogen, progesterone, and the menstrual cycle: A systematic review of fear learning, intrusive memories, and PTSD., Clin. Psychol. Rev 66 (2018) 80–96. 10.1016/j.cpr.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.