Abstract

Objective:

We sought to identify interactions between genetic factors and current/recent smoking, both of which influence SLE risk.

Methods:

673 SLE cases (1997 American College of Rheumatology criteria) were age-, sex- and race- (first 3 genetic principal components) matched to 3,272 controls. Smoking was classified as current/quit within 4 years before SLE diagnosis (or matched date) vs. distant past/never. 86 SNPs and 10 classical HLA alleles previously associated with SLE were included in a weighted genetic risk score (wGRS), dichotomized as low or high (≤ vs. > control median). Conditional logistic regression models estimated SLE and anti-double stranded DNA antibody(dsDNA)+ SLE risks. We tested for additive interactions using attributable proportion (AP) due to interaction and for multiplicative interactions using a 1 d.f. χ2 test for wGRS and for individual risk alleles. We repeated analyses among European-ancestry subjects.

Results:

Mean age at SLE diagnosis was 36.4 (± 15.3) years, 59.3% of cases were dsDNA+. 92.3% were female; 75.6% European, 4.5% Asian, 11.7% African, 8.2% other ancestry. High wGRS (OR 2.0, p 1.0×10−51 vs. low wGRS) and current/recent smoking (OR 1.5, p 0.0003 vs. distant/never smoking) were strongly associated with SLE risk, with significant additive interaction (AP 0.33, p 0.0012) and stronger findings for anti-dsDNA+ SLE risk. No significant multiplicative interaction was found for wGRS (p 0.58) or HLA-only wGRS (p 0.06). Findings were similar among European-ancestry individuals.

Conclusion:

The strong additive interaction between an updated SLE genetic risk score and current/recent smoking suggests smoking may influence specific genes in SLE pathogenesis.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, genetics, interactions, smoking, risk factors, pathogenesis, genetic risk score

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a complex and heterogeneous inflammatory autoimmune disease associated with a wide range of symptoms and organ-involvement. The disease primarily affects women of childbearing age with enormous social and financial impact1. SLE pathogenesis remains elusive, but both genetic and environmental factors play roles2. SLE heritability was recently estimated to be 44% using the Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database, with approximately 26% of phenotypic variance attributed to shared environmental factors2. The capacity to genotype numerous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across the genome in a robust, efficient, and cost-effective manner has allowed comprehensive genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in SLE. SLE GWAS have now identified more than 100 risk loci for SLE susceptibility across populations, adding to our understanding of disease pathogenesis3-8.

In a past meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies, we reported that current smoking increased SLE by 50%, whereas past smoking was not associated with SLE9. We also demonstrated that current/recent smoking specifically elevated risk of the subtype of SLE characterized by anti-dsDNA autoantibodies10. Interactions between genetic and environmental factors are involved in disease etiology but have yet to be examined in SLE across the genome. In statistical terms, a gene-environment interaction is present when the effect of genotype on disease risk depends on the level of exposure to an environmental factor, or vice versa11. In the current study, we sought to identify potential gene-smoking interactions in SLE susceptibility. We constructed an updated weighted genetic risk score for SLE, utilizing data from recent large GWAS and meta-analyses to assess for interactions between the exposure of current/recently quit smoking and known genetic risk factors, in aggregate and individually, influencing SLE risk.

Methods

Study Population and Smoking Exposure Data Collection.

We utilized genetic and epidemiologic data from 1,274 Nurses’ Health Studies (NHS) cohort participants and 2,675 Partners Healthcare Biobank (PHB) participants, including a total of 673 SLE cases and their 3,272 matched control subjects. The NHS and NHSII are female prospective cohort studies in which data on lifestyle, behavioral factors and disease outcomes have been collected every two years by questionnaire10. NHS began in 1976 and enrolled 121,700 registered female nurses ages 30-55 from 11 U.S. states; NHSII began in 1989 and enrolled 116,430 registered female nurses ages 25-42 from 14 U.S. States. The preponderance of the NHS cohorts’ participants is of European ancestry, given the demographics of the nursing profession in the years of enrollment. Participants were asked to report new physician diagnoses of SLE on biennial questionnaires. Those indicating a new diagnosis were asked to complete the Connective Tissue Disease Screening Questionnaire12 and to consent to the release of their medical records. Released medical records of all nurses who indicated SLE symptoms on this questionnaire were independently reviewed by two board-certified rheumatologists. Cases were identified based on four or more of the 1997 Updated American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for the classification of SLE and reviewers’ consensus13-15. For each case in the NHS, ten NHS controls without any history of reporting a connective tissue disease and with available GWAS data, were selected, matched on age at index date of SLE diagnosis (within five years), self-reported race, and genotyping platform (detailed below). In NHSII, four NHSII controls were similarly matched to each SLE case. Detailed smoking exposure data for all cases and controls, including age started smoking and updated numbers of cigarettes smoked per day at each two-year time interval, were prospectively reported on every questionnaire. Given our past findings that current and recently quit smokers (within four years before SLE diagnosis) have elevated SLE risk, whereas more distant past and never smokers did not, we defined a binary smoking status variable9,10.

The PHB includes self-reported exposure data collected at enrollment, blood samples and GWAS results, as well as linked electronic medical records, for > 40,000 patient volunteers from the Partners’ Healthcare System in the greater Boston area16. All SLE cases in the PHB included in this study met ≥ four of 11 of the 1997 Updated ACR criteria for SLE classification13-15. Cases were identified by prior inclusion in the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Lupus Registry or by ≥ three International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9/10 codes for SLE, each ≥ 30 days apart, followed by medical record review for the 1997 ACR criteria13-15. For each SLE case selected from the PHB, we matched four controls, each of whom had available GWAS and PHB questionnaire data, by age at index date of SLE diagnosis (within five years), sex and race (by the first three genetic principle components). Patients with a history of any ICD-9/10 codes for SLE (or related diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, mixed connective tissue disease, scleroderma, Sjӧgren’s syndrome) were excluded from the potential control matching pool. Each control was assigned an index date that matched the date of SLE diagnosis in their matched case (and as cases and controls were matched on age at blood draw, they were of similar ages at the matched index date as well). Detailed smoking data for cases and controls, including amount and duration of smoking at different time points in life, were collected on the PHB enrollment questionnaire. As in NHS, smoking status at and prior to SLE diagnosis (or the matched index date in controls) was defined as current smoking/recent quitting within four years vs. more distant quitting/never smoking. Missing data on smoking were collected by medical record review.

Genotyping.

As prior GWAS studies had been performed on the NHS/NHSII cohort subjects, a total of six different genotyping platforms were employed, including five in prior studies and the Illumina MEGA chip, which was performed for the subjects with no available GWAS results. All PHB subjects were genotyped on Illumina arrays including the Infinium MEGA array, Infinium Expanded Multi-Ethnic Genotyping Array (MEGA Ex) (both are pre-release forms of Illumina’s Multi-Ethnic Global (MEG)) and Infinium Multi-Ethnic Global (MEG) BeadChip. Standard quality control was done for genotyped data, followed by imputation using the 1000 Genomes reference panel from the Michigan imputation. Principal components analysis was performed and used to match the PHB cases to controls on the first three principal components as above. Classical HLA alleles were imputed using SNP2HLA17 for the NHS/NHSII and PHB matched cases and controls separately. SNP genotyped/imputed data were extracted from imputed dataset using VCFtools18.

Calculation of SLE weighted Genetic Risk Score (wGRS).

All SNPs previously reported associated with SLE with genome-wide significance (p ≤ 5×10−8) were identified (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gwas/). SNPs in linkage disequilibrium (LD) were pruned in favor of the most significant SNP, and the remaining SNP set included 86 SNPs with pair-wise LD R2 of ≤0.3. If an imputed SNP was used, the imputation information score had to be ≥0.8. As the literature supports that SNPs for complex traits are often consistent across populations with similar effect directions of the alleles upon traits19-21, and as most of our sample was of European or Asian ancestry, we included SNPs reportedly associated with SLE in populations of either European or Asian ancestry. Our wGRS was weighted by the odds ratio (OR) of reported associations, and calculated as: , where ORi is the effect size reported for SNPi and SNPi is the number of copies (0, 1, or 2) of the risk alleles or (0-2) dosage for imputed SNPs. Ten classical HLA alleles were included in the wGRS using SLE association results from Langefeld et al3. The 86 SNPs included in our wGRS and the ORs employed for weighting are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. The ten HLA alleles included and their effect sizes from the literature used for weighting are summarized in Supplementary Table 2. Employing receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis, we tested whether the wGRS based on European-derived GWAS SLE risk SNPs enabled separation of SLE cases and controls among all our samples, and whether SNPs derived from GWAS in Asian populations discriminated between cases and controls.

Main effect of gene and smoking analyses.

We studied the associations of a) smoking status, b) the wGRS, both as a continuous variable and dichotomized as low or high (≤ vs. > median in controls), with SLE status, utilizing conditional logistic regression, conditioning on the matched sets, and c) in addition, each risk locus (86 SNPs and 10 classical HLA alleles) as secondary analysis, as well as controlling for smoking status. Overall smoking status and wGRS association effects were combined for the NHS/NHSII and PHB datasets using the inverse variance weighting meta-analysis method.

Gene-smoking interaction analyses.

After pooling NHS and PHB data, we first examined additive interactions between SLE wGRS and smoking status using the attributable proportion (AP) due to interaction to assess biologic interaction22. This tests whether subjects with both exposure, high risk wGRS and current/recent smoking, have excess risk attributable to the interaction between the two factors. Using methods previously described23-27, we calculated the AP for interaction between dichotomous low vs. high SLE wGRS and smoking status in influencing SLE risk. We performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to subjects of European ancestry for association and interaction analyses. Next, we tested for multiplicative interactions between smoking status and SLE wGRS, as well as individual risk SNPs and HLA alleles, influencing SLE risk. We assessed the multiplicative interaction term using a 1 d.f. χ2 test in a conditional logistic regression model, adjusted for cohort. The wGRS was examined as a continuous variable, as well as dichotomized into high and low using the median value the controls as the cutoff. We also plotted the SLE wGRS distribution for cases and controls separately, stratified by smoking status. We applied a false discovery rate (FDR) of <0.05 to correct for multiple comparisons. Analyses were conducted with SAS and R. The Partners’ Healthcare Institutional Review Board approved all aspects of this study.

Results

We identified 138 SLE cases in NHS/NHSII and 535 SLE cases in PHB, all of whom had GWAS results and smoking data from prior to SLE onset as above. The characteristics, including smoking exposures, of each dataset are shown in Table 1. The NHS cohorts were all female and 98% of European ancestry. Among the NHS SLE cases, 17.4% were current smokers at or within four years of SLE diagnosis vs. 14.9% in controls at matched index dates. Among the PHB SLE cases and their matched controls, 90% were female; 68.1% were of European ancestry (4.9% Asian, 14.2% African and 12.8% others). Among PHB SLE cases, 21.9% were current smokers or had quit within 4 years at the time of SLE diagnosis vs. 15.8% in matched controls at a similar index date.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of the SLE Cases and their Matched Controls at Index Date of SLE Diagnosis

| NHS SLE Cases (138) |

NHS Controls (1136) |

Partners Biobank SLE Cases (535) |

Partners Biobank Controls (2136) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age in years, (SD) | 51.8 (10.9) | 53.5 (10.3) | 32.4 (13.7) | 32.4 (13.8) |

| Non-European ancestry (%) | 1.5 | 1.4 | 30.4 | 30.8 |

| Female (%) | 100 | 100 | 90.3 | 90.3 |

| Never/Distant Smoker, (%) | 82.6 | 85.1 | 78.1 | 84.2 |

| Current/Recent Smoker, (%) | 17.4 | 14.9 | 21.9 | 15.8 |

| Mean number of 1997 American College of Rheumatology Criteria for SLE Classification, (SD) | 4.7(1.2) | -- | 5.1(1.6) | -- |

| ANA+ (%) | 94.9 | -- | 96.8 | -- |

| Arthritis | 76.1 | -- | 74.6 | -- |

| Hematologic involvement | 53.6 | -- | 67.3 | -- |

| Renal involvement | 14.5 | -- | 35.3 | -- |

| dsDNA+ | 39.1 | -- | 64.5 | -- |

The SLE clinical manifestations in each population are also summarized in Table 1. NHS cases and PHB cases had similar numbers of ACR criteria for classification of SLE, while a higher proportion were anti-dsDNA positive and had renal disease in the PHB cohort. PHB cases had more current/recent smoking compared to NHS cases (21.9% vs.17.9%, Table 1).

Main effects.

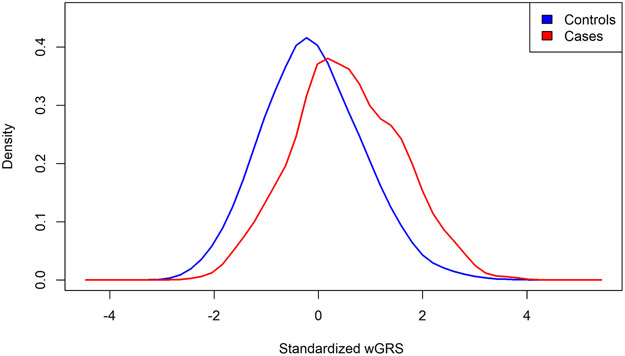

In our pooled case-control, current/recent smoking was associated with higher risk of SLE, OR 1.49 (95%CI 1.20-1.85, p 0.0003). The distribution of our updated wGRS for cases and controls is shown in Figure 1, which was comprised of 86 SNPs previously reported in genotyped or imputed SNP datasets, as well as imputed HLA classical alleles associated with SLE risks, as above. Our updated wGRS based on European-derived GWAS SLE risk SNPs enabled good differentiation of SLE cases and controls among all samples with ROC of 69.1% (Supplementary Figure 1). The SNPs derived from GWAS in Asian populations also worked well to separate cases and controls with ROC of 62.7% (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Standardized wGRS distribution for pooled cases and controls

Our SLE wGRS was significantly associated with SLE: each one standard deviation (SD) increase in wGRS corresponded to an odds ratio (OR) increase in SLE risk of 2.01 (p 1.0×10−51, Table 2). The association with SLE for each individual risk SNP/alleles were similar with the effect size reported on GWAS catalog. We did not observe smoking status to be a confounder to any of the risk SNP (data not shown). The alleles most significantly associated with SLE risk were HLA alleles DRB1-0301, IRF5 on chromosome 7, BLK on chromosome 8, STAT4 on chromosome 2, and TNIP1 on chromosome 5. For example, the HLA DRB1-0301 had an allele frequency of 0.18 for cases vs. 0.11 for controls, p 7.9×10−16.

Table 2.

Main Effects: Associations between dichotomized wGRS, Current/Recent Smoking and SLE Risk

| Beta | SE | Odds Ratio | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| wGRS | 0.70 | 0.05 | 2.01 | 1.0E-51 |

| wGRS nonHLA | 0.62 | 0.05 | 1.87 | 3.2E-40 |

| wGRS HLA | 0.35 | 0.04 | 1.42 | 1.1E-17 |

| Current/Recent Smoking vs. Never/Distant | 0.40 | 0.11 | 1.49 | 0.00031 |

Additive interactions between genetic risk for SLE and current/recent smoking.

SLE susceptibility was also strongly associated with high wGRS vs. low wGRS, dichotomized using the median value among the controls. Compared to the reference group of non-smokers in the low wGRS category, current/recently quit smokers with low wGRS had an OR of 1.28 (95%CI 0.81-2.01) for SLE, while non-smokers with high wGRS had an OR of 3.52 (95%CI 2.78-4.44). Among those who were both current/recent smokers and in the high SLE wGRS category, the OR was 5.67 (95%CI 4.12-7.79) for SLE. We observed a significant additive interaction between both high wGRS and current/recent smoking with an attributable proportion (AP) of 33% (95%CI 13-53%, p 0.0012, Table 3). Among those who had dsDNA+ SLE compared to their matched controls, we observed a stronger AP of 45% (95%CI 24%-66%, with p 0.00003, Table 3). The strongest additive scale interactions between individual SLE risk SNPs and current/recent smoking are reported in Table 4. Using FDR controlling for multiple testing, we found significant additive interactions for ETS1, FLI1, KIT, UHRF1BP1, BLK, GPR78, NR, UBE2L3, SMG7 and NCF2 with current/recent smoking.

Table 3.

Gene-Smoking Interactions in SLE Risk and in dsDNA+ SLE Risk

| GRS* | Smoking | Case N |

Control N |

All SLE OR (95% CI) |

dsDNA+ SLE OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additive | |||||

| Interactions | |||||

| Low wGRS* | Never/Distant | 126 | 1371 | 1.0 (Ref.) | 1.0 (Ref.) |

| Low wGRS* | Current/Recent | 30 | 265 | 1.28 (0.81-2.01) | 1.73 (0.93-3.21) |

| High wGRS* | Never/Distant | 406 | 1394 | 3.52 (2.78-4.44) | 4.64 (3.33-6.46) |

| High wGRS* | Current/Recent | 111 | 242 | 5.67 (4.12-7.79) | 9.74 (6.24-15.19) |

| Smoking + wGRS* | |||||

| Attributable Proportion (95%CI) | 0.33 (0.13-0.53) | 0.45 (0.24-0.66) | |||

| p for interaction | 0.0012 | 0.000027 | |||

| Multiplicative Interactions | |||||

| Smoking x wGRS* | |||||

| p for interaction | 0.38 | 0.58 | |||

wGRS includes 86 SLE SNPs + 10 HLA alleles, dichotomized at median among controls

Table 4.

Strongest Additive interactions between Individual SLE-risk SNPs and Smoking in risk of SLE

| Chr:bp | RS | Genes | AP (CI) | P | FDR | OR genetic only |

OR smoking only |

OR both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11:128499000 | rs7941765 | ETS1, FLI1 | 0.46 (0.22 - 0.69) | 0.00018 | 0.0097 | 0.90 | 1.17 | 1.96 |

| 4:55548475 | rs2855772 | KIT | 0.38 (0.18 - 0.59) | 0.00027 | 0.0097 | 4.63 | 1.34 | 8.07 |

| 6:35033854 | rs820077 | UHRF1BP1 | 0.36 (0.16 - 0.57) | 0.00041 | 0.0097 | 3.05 | 1.12 | 4.99 |

| 8:11343973 | rs2736340 | BLK | 0.41 (0.18 - 0.63) | 0.00042 | 0.0097 | 1.40 | 1.21 | 2.72 |

| 4:8558266 | rs13116227 | GPR78 | 0.43 (0.18 - 0.67) | 0.00066 | 0.011 | 1.04 | 1.13 | 2.03 |

| 11:118573519 | rs4639966 | NR | 0.34 (0.14 - 0.53) | 0.00071 | 0.011 | 4.15 | 1.18 | 6.54 |

| 22:21976934 | rs7444 | UBE2L3 | 0.32 (0.11 - 0.52) | 0.0021 | 0.025 | 3.95 | 1.26 | 6.16 |

| 1:183542323 | rs17849501 | SMG7, NCF2 | 0.34 (0.1 - 0.58) | 0.0048 | 0.045 | 2.54 | 1.36 | 4.40 |

Multiplicative interactions between genetic risk for SLE current/recent smoking.

We did not detect statistically significant multiplicative interactions between current/recently quit smoking and the continuous wGRS (p 0.58) (Supplementary Table 3). However, we did observe a borderline multiplicative interaction of current/recently quit smoking with the HLA allele-only wGRS (p 0.06), as well as with the non-HLA wGRS (p 0.1). Similar results were found when we restricted analyses to those of European ancestry only (p 0.04, p 0.12 respectively). HLA-DRB1-0102, a risk allele for SLE, did have a significant multiplicative interaction with current/recent quitting smoking with p = 0.002. The SLE-associated SNP in SPATA8, rs8023715, also had a multiplicative interaction with current/recent smoking (p 0.004). However, after FDR correction for multiple testing, these multiplicative interactions did not remain significant. The SLE wGRS distribution for cases and controls separately, stratified by smoking status, is shown in Supplementary Figure2. It would be expected that the controls have lower wGRS than SLE cases and that smoker SLE cases have lower wGRS than the non-smoker SLE cases, although the relatively small number of cases here produced somewhat overlapping wGRS in the latter two groups.

Discussion

In this largest gene-environment interaction study of SLE to date and the first, to our knowledge, to employ GWAS results rather than to investigate individual candidate polymorphisms, we created an updated weighted GRS compared to existing GRS papers on SLE28,29, and tested for interactions between SLE genetic factors and smoking status influencing SLE risk. We found that having high wGRS and current/recent smoking both individually strongly associated with SLE risk: each SD increase in the wGRS more than doubled SLE risk, while current and recently quit smokers had an approximately 50% increased SLE risk compared to never and more distant past smokers. It is believed that testing for the presence of additive interaction may be more relevant for some scientific objectives30. A number of researchers have shown that conceptual models for biologic interaction translate to the presence of interaction on the additive scale and not necessarily on the multiplicative scale22,27. We discovered a significant additive interaction between a high vs. low wGRS and current/recent vs. past/never smoking, where 33% of the excess risk of SLE among smokers with high wGRS was due to interaction. We also found a similar additive interaction between high wGRS and current/recent smoking for the risk of dsDNA+ SLE, where 45% of the excess risk of SLE among smokers with high wGRS was due to interaction. We found significant additive interactions for several individual SLE-related SNPs and current/recent smoking, including ETS1, FLI1, KIT, UHRF1BP1, BLK, GPR78, NR, UBE2L3, SMG7, NCF2. Significant multiplicative interactions were not found using the continuous SLE wGRS, but were found for current/recent smoking and specific SLE-risk genotypes, including HLA-DRB1 0102 and SPATA8. However, these associations were not significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons. We suspect that the reason that no formal interaction was found between wGRS and smoking in determining SLE risk is that we were testing for multiplicative interactions, rather than additive interactions. Multiplicative interaction, testing for a significantly greater than multiplicative interaction between the two risk factors on a logarithmic scale in a logistic regression analysis, is a higher bar for formal interaction testing than is the test for a greater than additive interaction between the two risk factors30.

Past studies and meta-analyses strongly associate current cigarette smoking with increased SLE risk9,10. Among women in the NHS cohorts, we reported strong and specific associations of current smoking, particularly with the subtype of dsDNA autoantibody+ SLE (HR 1.86 [1.14-3.04]), suggesting ongoing smoking is involved in SLE pathogenesis and that effects diminish after cessation10. Potential biologic mechanisms by which smoking may contribute to or accelerate SLE pathogenesis include damage to DNA and proteins, induction of oxidative stress31, stimulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6, and increased CD95 expression on B and CD4 T cells, inducing apoptosis and inducing autoimmunity32. Smoking also impairs NK cell function and may influence inflammatory Th17 and Th22 cell functions via the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), activated by benzopyrenes in cigarette smoke. We have also found that current smoking was associated with increased SLE-specific cytokines interferon (IFN)-α and B Lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) among women in the NHS cohorts without SLE33.

In the related autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), there is a statistical multiplicative interaction as well as additive interaction between RA genetic risk and smoking, in particular with HLA-DRB1 genes26,34. This interaction, strongest for seropositive RA, has been replicated in several populations, including US women and Swedish, Korean, and Malaysian groups26. The smoking-RA genetic risk interaction is thought to accelerate citrullination of peptides at mucosal surfaces, such as in the lungs, and the development of anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA)-targeted autoimmunity in RA. It is possible, although not yet thoroughly investigated, that similar processes arise from smoking and genetic interactions in driving the production of SLE-specific cytokines and autoimmune reactions, accelerating pathogenesis. Our current findings of interactions between current/recent smoking and SLE wGRS (with an OR of AP due to interaction 33% (95%CI 13-53%, p 0.0012)) and stronger interaction for dsDNA autoantibody+ SLE imply that smoking has a greater influence if these SLE genetic factors are present. Future studies should investigate the biologic mechanisms of gene-smoking interactions for SLE risk, such as immunologic mechanisms, anatomic site, autoantibody production, and timing prior to clinical onset.

To date, there have been only a few investigations of gene-environment interactions in SLE susceptibility, and these have been limited by small sample sizes35,36. Ours is the first to investigate all previously identified SLE genetic risk polymorphisms into a single genetic risk score. Small case-control studies in Japanese populations have reported additive interactions between candidate polymorphisms, including the SLE risk gene TNFRSF1B, as well as detoxification genes and genotypes CYP1A1, GSTM1, N-acetyltransferase-2 (NAT2), and ever/never smoking in elevating SLE risk35-37. In a study of 152 SLE cases and 427 controls in Japan, smoking and two candidate genes were studied for potential interactions with smoking. An interaction between TNFRSF1B risk genotypes GG or GT and smoking (ever/never) was found, with a significant attributable proportion of 0.49 (49% of the excess risk of SLE among smokers with a G allele was due to an interaction)36. No interaction between STAT4 SLE risk alleles and smoking was found. AsTNFRSF1B has not been confirmed as a SLE risk gene in other populations and did not reach genome-wide significance, it was not included in our updated wGRS for SLE. The same Japanese research group also studied interactions between smoking and detoxification genes, CYP1A1, GSTM1, N-acetyltransferase-2 (NAT2) in SLE risk in the same population37. An interaction between smoking (ever/never) and the NAT2 slow acetylator genotype was found with a significant attributable proportion due to interaction of 0.5035. Again, these genotypes were not included in our wGRS as they have not reached genome-wide significance in past SLE studies.

The current study has several strengths. It leveraged rich prospectively-collected exposure and genetic data from a large cohort of U.S. women who have been followed with detailed smoking exposure information from prior to SLE onset, as well as a large hospital-based SLE cohort with both self-reported questionnaire exposure data and linked electronic medical records. For both populations, non-affected controls were closely matched by age, sex and race. Importantly, prospective smoking exposure data were collected from the time prior to the SLE diagnosis or matched index date in controls and categorized based on smoking status and duration of cessation. All SLE cases were carefully validated by expert review of the medical records for the American College of Rheumatology criteria for SLE and expert reviewers’ consensus opinion. Using GWAS data, we developed an updated wGRS for SLE using the most comprehensive set of European and Asian risk alleles for SLE currently available. We investigated the interactions of current/recent smoking and genetic risk factors in determining the risk of anti-dsDNA positive SLE (59% of our cases), given our past finding that current smoking was a stronger risk factor for this SLE subtype, and found that the additive interaction effects were stronger in that subgroup. No SLE gene-environment studies have been performed to date using GWAS results as the populations employed for SLE GWAS have not had access to detailed data on environmental exposures. However, GWAS gene-environment interaction studies have been fruitful in many other complex diseases, in which they have helped to identify new pathologic mechanisms and synergies between genetic and environmental factors38

This study does have some limitations. We pooled data from two different SLE case-control populations. The NHS cohorts have prospectively collected data, and thus, the risk of potential misclassification of smoking status is lower than in the PHB where past exposure data were collected from prevalent SLE cases. On the other hand, the NHS cohorts are all female and >98% of European ancestry, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings from that population. Thirty percent of the PHB population was of Asian, African or Hispanic descent. Our wGRS SNPs and HLA were taken from large European and Asian GWAS, as large SLE GWAS in other ancestry populations have not been conducted to date4,39-45. One recent SLE GWAS was performed in Latin Americans (predominantly those of European and Native American origin)46. There is debate as to whether the risk alleles identified in European and Asian populations are similar to those found in populations of African or South American ancestry; studies point to many risk alleles having similar effects in different ancestry populations, whereas there are likely many more yet to be identified, given the lack of studies of diverse populations3,47. We found strong associations of SLE using European-derived SNPs in non-European populations and using Asian-derived SNPs in European populations. When we limited our study to those of European descent and the wGRS to European-only genotypes, we observed similar main effects and interaction results.

In this large SLE case-control study of gene-environment interactions, we have found that individuals with both high SLE genetic risk (wGRS) and current or recent smoking had a greater than an additive risk of developing SLE, compared to having only genetic risk or only smoking as a risk factor. We found a greater than multiplicative interaction between HLA-DRB1-0102 SLE risk allele and current/recent smoking in influencing SLE risk (p 0.002). These novel findings support the hypothesis that current smoking triggers SLE in presence of genetic factors, with a greater than additive interaction with overall genetic risk and potentially greater than multiplicative interaction with certain genotypes. Studies should now investigate mechanisms of these interactions and whether smoking influences function of these genes in SLE pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the participants in the NHS and NHSII cohorts for their dedication and continued participation in these longitudinal studies, as well as the staff in the Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School for their assistance with this project.

Disclosures and funding: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health UM1 CA186107, P01 CA87969, R01 CA49449, R01 HL034594, R01 HL088521, U01 CA176726, R01 CA67262, R01 AR057327 and Supplement to Advance Research (STAR) R01 AR057327-S1, as well as K24 AR066109, R01 AR AR049880 and NIAMS-funded NIH-P30-AR072577 (VERITY). The Partners HealthCare Biobank is supported by Partners HealthCare System. Dr. Raychaudhuri is supported by 1R01AR063759-01A1, NIH NIAID UM1AI109565. Dr Knevel is supported by the Dutch Arthritis fund 15-3-301.

References

- 1.Lotstein DS, Ward MM, Bush TM, Lambert RE, van Vollenhoven R, Neuwelt CM. Socioeconomic status and health in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. The Journal of rheumatology. 1998;25(9):1720–1729. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Valdes AM, et al. Familial Aggregation of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Coaggregation of Autoimmune Diseases in Affected Families. JAMA internal medicine. 2015;175(9):1518–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Langefeld CD, Ainsworth HC, Cunninghame Graham DS, et al. Transancestral mapping and genetic load in systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature communications. 2017;8:16021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bentham J, Morris DL, Graham DSC, et al. Genetic association analyses implicate aberrant regulation of innate and adaptive immunity genes in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2015;47(12):1457–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gateva V, Sandling JK, Hom G, et al. A large-scale replication study identifies TNIP1, PRDM1, JAZF1, UHRF1BP1 and IL10 as risk loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2009;41(11):1228–1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris DL, Sheng Y, Zhang Y, et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis in Chinese and European individuals identifies ten new loci associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2016;48(8):940–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada Y, Shimane K, Kochi Y, et al. A genome-wide association study identified AFF1 as a susceptibility locus for systemic lupus eyrthematosus in Japanese. PLoS genetics. 2012;8(1):e1002455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.International Consortium for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus G, Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costenbader KH, Kim DJ, Peerzada J, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus: a meta-analysis. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2004;50(3):849–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbhaiya M, Tedeschi SK, Lu B, et al. Cigarette smoking and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus, overall and by anti-double stranded DNA antibody subtype, in the Nurses' Health Study cohorts. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2018;77(2):196–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clayton D, McKeigue PM. Epidemiological methods for studying genes and environmental factors in complex diseases. Lancet. 2001;358(9290):1356–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karlson EW, Sanchez-Guerrero J, Wright EA, et al. A connective tissue disease screening questionnaire for population studies. Annals of epidemiology. 1995;5(4):297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis and rheumatism. 1997;40(9):1725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan EM, Cohen AS, Fries JF, et al. The 1982 revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25(11):1271–1277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merola JF, Bermas B, Lu B, et al. Clinical manifestations and survival among adults with (SLE) according to age at diagnosis. Lupus. 2014;23(8):778–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karlson EW, Boutin NT, Hoffnagle AG, Allen NL. Building the Partners HealthCare Biobank at Partners Personalized Medicine: Informed Consent, Return of Research Results, Recruitment Lessons and Operational Considerations. Journal of personalized medicine. 2016;6(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jia X, Han B, Onengut-Gumuscu S, et al. Imputing amino acid polymorphisms in human leukocyte antigens. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e64683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2011;27(15):2156–2158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ntzani EE, Liberopoulos G, Manolio TA, Ioannidis JP. Consistency of genome-wide associations across major ancestral groups. Human genetics. 2012;131(7):1057–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marigorta UM, Navarro A. High trans-ethnic replicability of GWAS results implies common causal variants. PLoS genetics. 2013;9(6):e1003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C, Ahlford A, Jarvinen TM, et al. Genes identified in Asian SLE GWASs are also associated with SLE in Caucasian populations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2013;21(9):994–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andersson T, Alfredsson L, Kallberg H, Zdravkovic S, Ahlbom A. Calculating measures of biological interaction. European journal of epidemiology. 2005;20(7):575–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim K, Jiang X, Cui J, et al. Interactions between amino acid-defined major histocompatibility complex class II variants and smoking in seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ. 2015;67(10):2611–2623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han SS, Rosenberg PS, Garcia-Closas M, et al. Likelihood ratio test for detecting gene (G)-environment (E) interactions under an additive risk model exploiting G-E independence for case-control data. American journal of epidemiology. 2012;176(11):1060–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim S, Wang M, Tyrer JP, et al. A comprehensive gene-environment interaction analysis in Ovarian Cancer using genome-wide significant common variants. International journal of cancer. 2019;144(9):2192–2205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlson EW, Chang SC, Cui J, et al. Gene-environment interaction between HLA-DRB1 shared epitope and heavy cigarette smoking in predicting incident rheumatoid arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2010;69(1):54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kallberg H, Ahlbom A, Alfredsson L. Calculating measures of biological interaction using R. European journal of epidemiology. 2006;21(8):571–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen L, Wang YF, Liu L, et al. Genome-wide assessment of genetic risk for systemic lupus erythematosus and disease severity. Human molecular genetics. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reid S, Alexsson A, Frodlund M, et al. High genetic risk score is associated with early disease onset, damage accrual and decreased survival in systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2020;79(3):363–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sparks JA, Costenbader KH. Genetics, environment, and gene-environment interactions in the development of systemic rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2014;40(4):637–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pryor WA SK. Oxidants in cigarette smoke. Radicals, hydrogen peroxide, peroxynitrate, and peroxynitrite. . Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;686:12–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walczak H, Krammer PH. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) apoptosis systems. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256(1):58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leatherwood C, Liu X, Malspeis S, et al. Associations between Current Cigarette Smoking and SLE-Related Cytokine and Chemokine Biomarkers Among U.S. Female Nurses without SLE [abstract]. Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2018;70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundstrom E, Kallberg H, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Padyukov L. Gene-environment interaction between the DRB1 shared epitope and smoking in the risk of anti-citrullinated protein antibody-positive rheumatoid arthritis: all alleles are important. Arthritis and rheumatism. 2009;60(6):1597–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kiyohara C, Washio M, Horiuchi T, et al. Cigarette smoking, N-acetyltransferase 2 polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. Lupus. 2009;18(7):630–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kiyohara C, Washio M, Horiuchi T, et al. Cigarette smoking, STAT4 and TNFRSF1B polymorphisms, and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. The Journal of rheumatology. 2009;36(10):2195–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiyohara C, Washio M, Horiuchi T, et al. Risk modification by CYP1A1 and GSTM1 polymorphisms in the association of cigarette smoking and systemic lupus erythematosus in a Japanese population. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. 2012;41(2):103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simon PH, Sylvestre MP, Tremblay J, Hamet P. Key Considerations and Methods in the Study of Gene-Environment Interactions. Am J Hypertens. 2015;29(8):891–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harley JB, Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Criswell LA, et al. Genome-wide association scan in women with systemic lupus erythematosus identifies susceptibility variants in ITGAM, PXK, KIAA1542 and other loci. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):204–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hom G, Graham RR, Modrek B, et al. Association of systemic lupus erythematosus with C8orf13-BLK and ITGAM-ITGAX. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(9):900–909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nath SK, Han S, Kim-Howard X, et al. A nonsynonymous functional variant in integrin-alpha(M) (encoded by ITGAM) is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):152–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozyrev SV, Abelson AK, Wojcik J, et al. Functional variants in the B-cell gene BANK1 are associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2008;40(2):211–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han JW, Zheng HF, Cui Y, et al. Genome-wide association study in a Chinese Han population identifies nine new susceptibility loci for systemic lupus erythematosus. Nature genetics. 2009;41(11):1234–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang W, Zhao M, Hirankarn N, et al. ITGAM is associated with disease susceptibility and renal nephritis of systemic lupus erythematosus in Hong Kong Chinese and Thai. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18(11):2063–2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang W, Shen N, Ye DQ, et al. Genome-wide association study in Asian populations identifies variants in ETS1 and WDFY4 associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS genetics. 2010;6(2):e1000841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alarcon-Riquelme ME, Ziegler JT, Molineros J, et al. Genome-Wide Association Study in an Amerindian Ancestry Population Reveals Novel Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Risk Loci and the Role of European Admixture. Arthritis & rheumatology (Hoboken, NJ. 2016;68(4):932–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hanscombe KB, Morris DL, Noble JA, et al. Genetic fine mapping of systemic lupus erythematosus MHC associations in Europeans and African Americans. Human molecular genetics. 2018;27(21):3813–3824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.