Abstract

Problem

Improvements in chronic disease management has led to increasing numbers of youth transitioning to adult healthcare. Poor transition can lead to high risks of morbidity and mortality. Understanding adolescents and young adults (AYA) perspectives on transition is essential to developing effective transition preparation. The aim of this metasynthesis was to synthesize qualitative studies assessing the experiences and expectations of transition to adult healthcare settings in AYAs with chronic diseases to update work completed in a prior metasynthesis by Fegran and colleagues (2014).

Eligibility criteria

A search of PubMed, Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL was conducted to gather articles published after February 2011 through June 2019.

Sample

Of 889 articles screened, a total of 33 articles were included in the final analysis.

Results

Seven main themes were found: developing transition readiness, conceiving expectations based upon pediatric healthcare, transitioning leads to an evolving parent role, transitioning leads to an evolving youth role, identifying barriers, lacking transition readiness, and recommendations for improvements.

Conclusions

Findings of this metasynthesis reaffirmed previous findings. AYAs continue to report deficiencies in meeting the Got Transition® Six Core Elements. The findings highlighted the need to create AYA-centered transition preparation which incorporate support for parents.

Implications

Improvements in transition preparation interventions need to address deficiencies in meeting the Got Transition® Six Core Elements. More research is needed to identify and address barriers implementing the transition process.

Keywords: adolescents and young adults, transition, transition readiness, qualitative metasynthesis

With increasing numbers of youth with chronic diseases living into adulthood, preparation for transition to adult healthcare settings merits attention. Though transition has been a recognized issue since the 1980’s, transition preparation and interventions are not consistently provided when appropriate, and health outcomes after transfer demonstrate higher risks of morbidity and mortality for young adults (Blinder et al., 2015; Greutmann et al., 2015; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2018; Ryscavage, Macharia, Patel, Palmeiro, & Tepper, 2016). Transition has been described as a complex process rather than just a handoff of the youth’s care from the pediatric healthcare team to the adult healthcare team. It involves, but is not limited to, transfer of disease management from parents to the adolescent or young adults (AYA), coordination of a new healthcare team to take over responsibility for the AYA, transfer of appropriate medical records and information necessary for continuity of care, and engaging and assisting healthcare providers to tailor their clinical practices to support AYAs undergoing transition (Got Transition, 2014a). Many recommendations have been made to encourage the development of transition interventions to prepare AYAs for transition; however, AYAs still face barriers during this time period (Fegran, Hall, Uhrenfeldt, Aagaard, & Ludvigsen, 2014; Lebrun-Harris et al., 2018). Pre-transition barriers include the AYA’s negative feelings towards transfer to an adult healthcare setting (Gray, Schaefer, Resmini-Rawlinson, & Wagoner, 2018), inadequate self-management skills and disease knowledge (Frost et al., 2016; Philbin et al., 2017) and AYA’s lack of interest in leaving their comfortable pediatric environment (Philbin et al., 2017). Barriers to establishing care in the adult healthcare setting include lack of referral to a healthcare provider (Garvey et al., 2014; Quillen, Bradley, & Calamaro, 2017), poor communication between the pediatric and adult healthcare providers (de Silva & Fishman, 2014; Garvey et al., 2014), and not being offered the chance to have a clinic visit with the adult healthcare provider before being discharged from pediatric healthcare (Garvey et al., 2014). After transition, AYAs also face challenges including inconsistency between the pediatric and adult healthcare settings (Frost et al., 2016). Developing interventions for preparation and to improve the handoff between the different healthcare settings is essential to reducing these difficulties faced by AYAs during the transition time period. Understanding the AYAs’ perspectives on transition is instrumental to developing effective interventions which will be perceived as relevant and informative. Fegran et al. (2014) completed a metasynthesis on qualitative studies assessing AYAs’ experiences of transition from 1999 through February 2011. Given the increasing attention to transition care and an expanding qualitative evidence base, including seeking the AYAs’ perspectives, this metasynthesis was conducted to update the work completed by Fegran et al. (2014). This metasynthesis looked to synthesize more recent articles and to build upon previous findings. The research questions which guided this metasynthesis were: 1) What are AYAs’ perspectives of transition preparation and transfer to the adult healthcare setting? 2) What are their recommendations for improving the transition process?, and 3) How do these findings compare to the findings of the prior metasynthesis?

Aims

The aim of this metasynthesis was to update and compare prior work competed by Fegran and colleagues by synthesizing qualitative studies published since 2011 assessing the experiences and expectations of transition to adult healthcare settings in AYA with chronic diseases.

Methods

The methods for this metasynthesis were designed using Sandelowski and Barroso’s (2007) guidelines for synthesizing qualitative research (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). According to Sandelowski and Barroso (2007), metasynthesis is a research method which entails interpretation and synthesizing the findings from a collection of primary qualitative studies (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007). The steps involved in conducting this metasynthesis included: developing the purpose and justification, searching for and gathering primary qualitative studies, selecting studies for final inclusion using selective criteria and critical appraisal, analyzing and coding the primary studies, and synthesizing the findings of the analysis (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2007).

Inclusion Criteria

In order to build upon work completed by the prior metasynthesis, similar selection criteria were chosen to identify relevant literature. For a study to be included it needed to comprise (or contain) either adolescent’s or young adult’s experiences or expectations with transition preparation and transfer from the pediatric to the adult healthcare setting. AYAs in the study must have been diagnosed with a chronic disease. The AYAs could still be receiving care in the pediatric healthcare setting or they may have already transitioned to adult healthcare. The study also needed to incorporate a qualitative design and to be peer-reviewed and published in English.

Search Strategies

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Medline, PsycINFO, and CINAHL in October 2018 with supplementary searches conducted in May 2019 and October 2019 to capture relevant articles which were newly published. The search strategy included the key words “youth OR teenager OR young adult OR adolescent” AND “sickle cell OR epilepsy OR diabetes OR cystic fibrosis OR chronic kidney disease OR cerebral palsy OR neurogenic bladder OR spina bifida OR congenital heart disease OR asthma OR HIV OR transplant OR chronic disease OR chronic illness” AND “transfer OR transition” AND “qualitative study OR phenomenology OR grounded theory OR hermeneutics OR qualitative”. The prior metasynthesis in this area assessed literature from 1999 through February 2011. This metasynthesis sought to identify articles published March 2011 through January 2019. In addition bibliographies of relevant articles were searched to identify additional articles.

Search Outcome

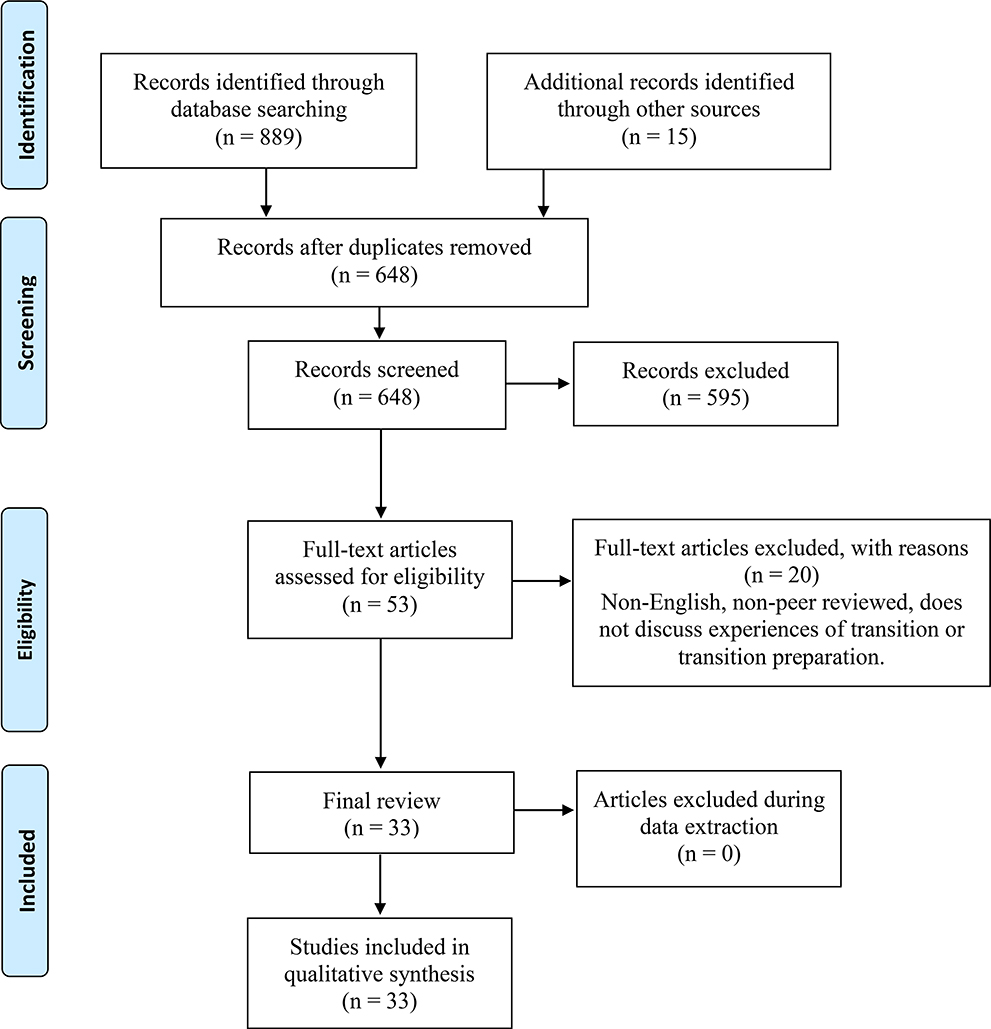

A PRISMA diagram (Figure 1) reflects the identification, inclusion, and exclusion of articles during the search process. A total of 889 records were identified through multiple database searches. After removing duplications a total of 648 abstracts were reviewed for relevance. A total of 53 full-text articles were retrieved since the abstracts appeared relevant to addressing the aims of this metasynthesis. Full-text articles were assessed using the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if they were not written in English, non-peer reviewed, or did not discuss experiences of transition or transition preparation. In total, 33 articles were included in the final analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA Flow Diagram

Assessment of Methodological Quality

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist was utilized to assess the quality of the studies. Two reviewers independently conducted quality appraisal (M.V. and K.P.K.) of all studies followed by discussion of their appraisals. Ten differences of opinion over specific items in the appraisal were resolved by consensus agreement. No studies were excluded as a result of the appraisal. Overall, a majority of the studies had clear statements of the aims, congruence between study purpose and methodology choices, appropriate research design and recruitment strategies, and clear statements of the findings. Only a few minor concerns were found regarding the rigor of data analysis. The CASP appraisal for the included articles can be found in the supplemental material.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Descriptive data were extracted from the primary studies including: chronic condition type, study aim, method of analysis, sample size, context (country in which study was conducted), process of recruitment, gender of participants, age range, data collection process, and summary of findings. Then the primary author (M.V.) extracted all the primary study findings to be analyzed utilizing the method developed by Sandelowski and Barroso (2007). For analysis, results sections from each primary article were copied in their entirety and placed in a table in Microsoft Word® along with the primary study citation. Microsoft Word® was utilized as not all of the authors had access to data analysis software or had training to utilized such software. M.V. conducted a thematic analysis on the pooled extracted study findings for all 33 articles. As new themes were recognized, sub-themes were created, and as repetitive sub-themes with similar content were recognized, subthemes were collapsed into themes. This process of reviewing the primary texts, creating, and collapsing sub-themes occurred until the researcher did not recognize any new themes, and the final theme and sub-themes could no longer be collapsed any further. An audit trail was maintained using a code book. After this initial analysis, two members of the study team (B.S.B. and L.P.) independently re-analyzed the extracted findings using the coding structure. Themes and subthemes were revised by the three primary researchers during team discussions. All disagreements were discussed until a consensus was reached.

The GRADE-CERQual approach was implemented in the analysis to provide an assessment of how much confidence could be placed in each of the theme findings. Lewin et al. (2010) developed this assessment to provide a transparent method for evaluating the findings of qualitative synthesis. It provides a structured approach which assesses four major components of the included studies that contributed evidence to the synthesis findings. These included methodological limitations, adequacy of the data, coherence, and relevance (Lewin et al., 2015). Methodological limitations refer to the issues related to the design or way in which the study was carried out (Lewin et al., 2015). The CASP appraisal checklist was utilized to assess methodological limitations. Adequacy of the data refers to quantity and degree of richness of data supporting a finding (Lewin et al., 2015). Coherence refers to how clear and convincing the fit is between the data from the primary studies and the review finding which synthesizes these data (Lewin et al., 2015). Finally, relevance refers to the extent to which the primary study findings supporting a synthesis finding is pertinent to the specific context (i.e. setting, population) of the metasynthesis research question (Lewin et al., 2015). More information on the GRADE-CERQual assessment for each main theme can be found in the supplemental material.

Results

A total of 33 studies were included in the final analysis. A majority of the studies were conducted in the United States (16); however, the studies were also conducted in the United Kingdom (5), Sweden (3), Germany (1), Switzerland (1), Canada (5), Belgium (1), Brazil (1), and France (1). Not all studies reported gender but across those which did, 55% of the participants were female. Fifteen different chronic condition types were reported. The studies utilized individual interviews, focus groups, and qualitative questionnaires to collect data. One study utilized a mixed-methods design to collect data, but only the qualitative data were utilized for this metasynthesis. More information on the studies’ characteristics can be found in the supplemental material.

AYAs’ experiences of transition preparation and processes from the 33 primary studies illustrated seven main themes: 1) developing transition readiness, 2) conceiving expectations based upon pediatric healthcare, 3) transitioning leads to an evolving parent role, 4) transitioning leads to an evolving youth role, 5) identifying barriers, 6) lacking transition readiness, and 7) recommendations for improvements. Definitions of the main themes can be found in Table 1. Definitions of the themes and subthemes can be found in the supplemental material.

Table 1.

Themes and their associated definitions identified in metasynthesis.

| Main Theme | Definition |

|---|---|

| Developing transition readiness | Adolescents and young adults view transition preparation as a time to obtain certain levels of knowledge, experience, support, and independence to help them succeed after transition to the adult healthcare setting. |

| Conceiving expectations based upon pediatric healthcare | Over their years of being taken care of by pediatric healthcare providers, adolescents and young adults have developed assumptions about their future adult healthcare teams which they carry with them while they are preparing for transfer and after they transfer to the adult healthcare setting. |

| Transitioning leads to evolving parent role | During transition to adult healthcare, AYA develop independence but still desire parents’ presence to assist with continuity of care and find them to be a source of comfort. |

| Transitioning leads to evolving youth’s role | The role of the adolescent and young adult transforms from a dependent and passive role to a more independent role with increased responsibility as they prepare or transition to adult healthcare. |

| Identifying barriers | Adolescents and young adults have recognized differences between the pediatric and adult setting, which causes concern for them during the transition. |

| Lacking transition readiness | A lack of transition preparation can lead to a variety of poor outcomes for youth in terms of health outcomes, relationships with new providers and their parents, and their perspective of the transfer to the adult healthcare setting. |

| Recommendations for improvement to transition preparation | Adolescents and young adults have numerous suggestions for assisting them as they plan for transition, which they would like to be implemented prior to transition to the adult healthcare setting. |

The GRADE-CERQual approach was used to establish the confidence level for the evidence contributing to each main theme. Themes were rated as having high confidence included “Developing Transition Readiness,” “Transitioning Leads to Evolving Parent Role,” “Lacking Transition Readiness,” and “Recommendations for Improvement.” Themes rated as having moderate confidence included “Conceiving Expectations Based Upon Pediatric Healthcare,” Transitioning Leads to Evolving Youth Role,” and “Identifying Barriers.”

Developing Transition Readiness

Increasing knowledge, especially information regarding what would happen after transition, provided comfort to AYAs, and they viewed it as a necessary tool for their new role after transition. Having information about the transition process alleviated surprise (Asp, Bratt, & Bramhagen, 2015; Sobota, Umeh, & Mack, 2015). Disease knowledge assisted them to determine which healthcare providers they needed to continue to see in the adult healthcare setting (Asp et al., 2015; Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Sobota et al., 2015). It also helped them to understand why they had undergone specific examinations in the past, why their treatment was important, and how to navigate going forward (Asp et al., 2015; Porter, Graff, Lopez, & Hankins, 2014). For AYAs, knowledge was the key to understanding the healthcare delivery process but was also a mechanism to increase their role in disease management.

Practicing independence in pediatric appointments readied AYAs for their new role after transition. Upon entering the adult healthcare setting, AYAs recognized a change in how the adult provider interacted with them in comparison to their pediatric provider, and AYAs felt that pediatric providers could assist with this difference by giving them an active role earlier (Nicholas et al., 2018; Ritholz et al., 2014; Sobota et al., 2015). They felt that taking part in self-management behaviors and engaging independently with pediatric providers let them learn skills for adulthood (Asp et al., 2015; Hilliard et al., 2014; Nicholas et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2014). Not all AYAs valued this practice while in pediatric health care settings, but retrospectively they found it to be beneficial (Sobota et al., 2015).

Trying out the new adult healthcare team prior to transition was another way to decrease the burden after transition. Meeting the team prior to transition increased feelings of security and confidence (Asp et al., 2015; Hilderson et al., 2013) and decreased feelings of uncertainty (Nicholas et al., 2018; Wright, Elwell, McDonagh, Kelly, & Wray, 2016). Having an overlapping clinic with both pediatric and adult providers helped to assure AYAs that information about their condition was going to be passed along; it also facilitated the development of their relationships with their new providers (Asp et al., 2015; Hilderson et al., 2013; Morsa et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2014; Tierney et al., 2013).

Developing independence and self-management was viewed as a natural development step for some AYAs during transition. Leaving pediatrics made them feel apprehensive; however, the benefit of leaving pediatrics included gaining independent decision-making and changing their relationship style with their provider (Bemrich-Stolz, Halanych, Howard, Hilliard, & Lebensburger, 2015; Burström, Öjmyr-Joelsson, Bratt, Lundell, & Nisell, 2016). Just as transferring settings was natural, so was the shifting of responsibilities between parents and AYAs (Hilliard et al., 2014). Providers could ensure that AYAs had increased independence by encouraging self-management, accountability, and providing education on disease self-management (Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Ritholz et al., 2014).

Conceiving Expectations Based Upon Pediatric Healthcare

Depending on when they were diagnosed with a chronic disease, AYAs may have spent years getting to know their pediatric providers which influenced their thoughts about future patient-provider relationships after transfer. They developed assumptions about their adult healthcare teams based upon their pediatric providers and worried about changes to come after transition (Wright et al., 2016). AYAs who had positive experiences with their pediatric team expected the same competence and level of familiarity with their new providers (Asp et al., 2015; Burström et al., 2016; Carroll, 2015; Morsa et al., 2018). Having strong relationships with pediatric providers led to AYAs having feelings of anxiety prior to transition (Wright et al., 2016). When they were not prepared for relationship changes, they expressed concerns with their first impressions and interactions (DiFazio, Harris, Vessey, Glader, & Shanske, 2014; Garvey et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2011). For AYAs with severe disease who had been more reliant on parents for disease management, they felt they could not meet the expectations of the adult providers and could not express themselves adequately (Huang et al., 2011). Change was not always negative though, as AYAs did see opportunity for personal growth as adult providers expected more in comparison to pediatric providers (Huang et al., 2011).

After transition, AYAs wanted to establish a trusting relationship with their adult provider. They had positive memories of their pediatric providers which influenced this desire (Carroll, 2015; Lewis & Noyes, 2013). Developing familiarity and trust with providers was considered a necessary step from the AYA’s perspective to smooth transition and helped to keep them engaged in their healthcare (Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Lochridge et al., 2013; Plevinsky, Gumidyala, & Fishman, 2015). AYAs described factors that helped to build trust including continuity of care, open communication active relationship building, and attentiveness to the AYAs’ needs (Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Machado, Galano, de Menezes Succi, Vieira, & Turato, 2016; Plevinsky et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2016). Factors that hindered the development of trust were AYAs’ concerns about the adult providers’ competence or concern that they would change their current treatment regimen (Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Lochridge et al., 2013; Porter et al., 2014). AYAs expressed that relationship building took time but could lead to a sense of partnership (Plevinsky et al., 2015; Price et al., 2011).

After transition, AYAs expected that their new adult healthcare provider would assist them in developing self-management and tailor this support to where the AYA was developmentally. Transition is a process and not all AYA are in the same place after transfer regarding their knowledge and abilities. They expected that the team should tailor their communication and expectations to meet the individual’s needs (Hilliard et al., 2014; Price et al., 2011). Providers could help AYA to self-manage by giving them practical advice regarding symptoms, lifestyle management, and self-care (Lewis & Noyes, 2013). Empowerment through assisting them to problem-solve and achieve independence in their healthcare was seen as a necessary and beneficial task of the adult provider (Price et al., 2011).

Transitioning Leads to an Evolving Parent Role

As the AYAs were heading into an unfamiliar setting with a new healthcare team, they continued to view their parents as a resource. During transition, they were enjoying their independence; however, they still found discussing their health with parents to be reassuring (Allen, Channon, Lowes, Atwell, & Lane, 2011). They wanted their parents’ role to focus less on disease management and more on providing support (Allen et al., 2011; Hilderson et al., 2013; Morsa et al., 2018). They were a resource for AYAs as they were trying to make decisions (Allen et al., 2011; Burström et al., 2017). Just maintaining connectedness with parents was considered a strength during this time (Ridosh, Braun, Roux, Bellin, & Sawin, 2011).

AYAs reported that transition required active participation from parents and reported specific functions which parents could assume in their new role during transition. Parents could advocate for them in adult healthcare, help them to remember their medical history, and help avoid misunderstandings with providers (Asp et al., 2015; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Lochridge et al., 2013; Nicholas et al., 2018; Ritholz et al., 2014). Parents acted as back-up for youth during this time (Hilliard et al., 2014). They could offer companionship during their first visits to the adult healthcare setting (Allen et al., 2011; Asp et al., 2015; Burström et al., 2017; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Ridosh et al., 2011; Wright et al., 2016). In addition, they aided AYAs during this time by slowly giving responsibility over to the AYA which was well-received by AYAs (Sobota et al., 2015).

Transitioning Leads to an Evolving Youth’s Role

Just as parents had an evolving role during transition, AYAs also recognized that their role would be changing and they saw the value and importance in assuming independence. AYAs expressed that the expected role change was natural and developing self-management was part of growing up (Lochridge et al., 2013; Morsa et al., 2018; Nguyen et al., 2016; Nicholas et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2014; Sobota et al., 2015). AYAs viewed this change in roles as an incremental process (Asp et al., 2015; Nicholas et al., 2018); they valued gaining knowledge and skills which would assist in increasing their ability to self-manage their disease and engage with their new providers (Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Sobota et al., 2015). To move forward with their life in areas like their education or careers, they knew they had to be more independent in their healthcare (Lochridge et al., 2013). This progression towards independence was viewed in a positive light even though they recognized many barriers to navigating transition such as identifying a new healthcare provider, making appointments, and understanding insurance issues (Plevinsky et al., 2015). Healthcare providers could assist with the role change by promoting and supporting the AYAs’ responsibility and accountability (Ritholz et al., 2014; Sobota et al., 2015). During transition, AYAs expressed a desire to feel like an adult and take on the adult role. They remarked that they liked that their adult healthcare provider treated their appointments more business-like (Hilderson et al., 2013). For youth with minor disease issues, this change in approach was welcomed as they wished to rely less upon others (Ridosh et al., 2011; Ritholz et al., 2014). However, AYAs with higher disease severity did not find this efficiency to be sufficient to address their worries (Huang et al., 2011). Transitioning to the adult healthcare system offered them an opportunity to increase independence, gain confidence in handling their medical issues, and reduced their feeling of being out of place in the pediatric setting (Lochridge et al., 2013). Being treated like an adult was also seen as a motivating factor to stay involved in their healthcare (Price et al., 2011). AYAs did also admit though that this adaption would need time for them to be comfortable (Tierney et al., 2013).

Identifying Barriers

AYAs felt that adult healthcare providers’ approach made it challenging to establish a new relationship with them after transition. AYAs viewed adult healthcare providers as less personable which suggested to the AYAs that they did not want to develop a relationship (Hilliard et al., 2014). In addition, AYAs also felt like actions taken by the adult healthcare providers indicated that they did not listen to the young adult causing them to experience poorer treatment and exposing them to worse outcomes such as unnecessary, additional emergency room visits (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015). Specific issues regarding adult healthcare providers’ approaches included their reduced time for appointments (Hilliard et al., 2014) and putting primary focus on clinical parameters during interactions (Tierney et al., 2013). Transition preparation did not necessarily lessen these concerns (Price et al., 2011). Even if the adult healthcare provider was capable or had the knowledge to care for the AYAs, the youth felt that this did not make up for the lack of personal connection (Wright et al., 2016).

AYAs expressed distress over losing their relationship with their pediatric provider at the time of transition. Pediatric providers were viewed like family and an important emotional connection (DiFazio et al., 2014; Porter et al., 2014). Having spent a period of time with their pediatric provider and having gotten used to a specific standard of care, AYAs developed reluctance towards transitioning (Lochridge et al., 2013; Machado et al., 2016; Porter et al., 2014). They also expressed feelings of abandonment (DiFazio et al., 2014). The loss of this relationship coupled with a negative experience in adult healthcare system prompted the AYA youth to return to the pediatric setting to seek care (Lochridge et al., 2013).

As they were struggling to let go of their pediatric healthcare teams, AYAs also expressed feelings that their adult providers did not know as much as their pediatric providers. In their first experiences with adult providers in places such as the emergency room and primary care, they noticed that the providers offered different treatments which made them think that the adult providers lacked expertise (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015; Carroll, 2015; DiFazio et al., 2014). Their adult providers did not give AYAs the impression that they knew them at all (Wright et al., 2016). For example, when the adult providers asked repetitive questions during appointments about medical history or disease self-management, this reinforced that adult providers were not acquainted with them and less capable than their pediatric providers (Porter et al., 2014; Wright et al., 2016).

Lacking Transition Readiness

When AYAs were not prepared for transition it shaped their perspectives of their future healthcare team even before they left the pediatric setting. Multiple studies found that youth either only had a brief conversation about transition or transition was not mentioned at all (Asp et al., 2015; Hilderson et al., 2013; Plevinsky et al., 2015). Abrupt transition led them to feel that independence was forced upon them (Hilderson et al., 2013). They did not understand how this change in their care team would impact them, why they had to make the change, who was responsible for them, or who would be a resource for them (Asp et al., 2015; Carroll, 2015; Catena et al., 2018; DiFazio et al., 2014; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lochridge et al., 2013; Morsa et al., 2018). They felt like novices as they interacted with adult providers as a result (Carroll, 2015). The uncertainty in their expectations was associated with reports of anxiety, fear, sadness, feelings of abandonment, and concerns about the future (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015; Garvey et al., 2014; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lochridge et al., 2013; Machado et al., 2016; Porter et al., 2014; Porter, Rupff, Hankins, Zhao, & Wesley, 2017).

AYAs reported that they did not have enough disease knowledge to actively participate in their healthcare after transition. AYAs reported not knowing specific details about their condition (Asp et al., 2015; Burström et al., 2016; Morsa et al., 2018; Ridosh et al., 2011; Sobota et al., 2015), and they reported being concerned that they did not know signs of deterioration for their conditions or when to seek help (Asp et al., 2015). They also reported uncertainty about how their disease could impact their future (Bomba, Herrmann-Garitz, Schmidt, Schmidt, & Thyen, 2017; Lopez et al., 2015). Lacking knowledge led AYAs to feel embarrassment and concern about conversations with their adult providers as they may not be able to answer all of the provider’s questions (Burström et al., 2016; Tierney et al., 2013). They felt lacking knowledge could make the difference in their health outcomes (Porter et al., 2017).

Lack of preparation for change in healthcare setting was associated with AYAs reports of the new environment being discomforting. They did not realize that they would have increased exposure to more of the long-term complications of their chronic disease or an older population (Garvey et al., 2014; Hilderson et al., 2013). This induced feelings of being in limbo. They felt too old for the pediatric setting but too young for the adult setting (Hilderson et al., 2013). Specifically, they did not feel prepared for the different approach of the healthcare team. The new environment was less friendly, unpleasant in terms of aesthetics, was too hurried, and mainly disease-focused rather than person-centered (Catena et al., 2018; Lochridge et al., 2013; Machado et al., 2016; Morsa et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2013). There was a decrease in the frequency of their follow-up appointments which led them to feel forgotten at times, get away with as minimal care as possible, and sometimes to disengage all together, especially if they perceived the adult provider did not care about them (Huang et al., 2011; Lewis & Noyes, 2013).

After AYAs transitioned to the adult healthcare setting, they felt uncertain of how to engage in the new setting. Though they want to be involved in their healthcare, AYAs’ lack of preparation left them unable to thoroughly understand what their adult healthcare team was asking of them or the language they used (Asp et al., 2015). Working alone with their provider made this lack of preparation increasingly evident (Asp et al., 2015). Even if they had begun to become more independent in disease self-management, this did not alleviate their concerns about feeling unprepared (Tierney et al., 2013). When parents had been responsible for most of the AYAs’ care, AYAs found it confusing to understand what their role and responsibilities would look like when in the adult healthcare setting (Asp et al., 2015). They reported being nervous about having conversations with adult providers as they were used to the communication styles of their pediatric providers (Wright et al., 2016). On a practical level they lacked preparation in identifying healthcare providers and other health resources (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015; Garvey et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2011). They found it challenging to understand insurance and how insurance affected their care (Bemrich-Stolz et al., 2015). When an AYA was not engaged in the system or with their new adult healthcare team after transition, then they often sought care at the minimum necessary (Garvey et al., 2014; Lewis & Noyes, 2013).

Recommendations for Improvements to Transition Preparation

AYAs wanted age pertinent information in light of living with a chronic disease. They asked that knowledge be given to them which was appropriate for where they were at personally in their lives (Bomba et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2016; Catena et al., 2018; Garvey et al., 2014; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lewis & Noyes, 2013; Lopez et al., 2015). For example, females wanted information on pregnancy and contraception, and they wanted healthcare providers to think carefully about timing of providing information as waiting until adult healthcare was often too late for this information (Bomba et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2016; Catena et al., 2018; Lopez et al., 2015). Both genders talked about wanting to know about hereditary issues (Burström et al., 2016). Other topics which AYAs reported desiring more knowledge on included drugs, alcohol, and other lifestyle related information (Bomba et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2017; Garvey et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2015; Morsa et al., 2018; Nicholas et al., 2018; Price et al., 2011). AYAs wanted pediatric and adult providers to recognize that emerging adults were a specific developmental group with unique needs (Bomba et al., 2017; Carroll, 2015; Freeman, Stewart, Cunningham, & Gorter, 2018; Garvey et al., 2014; Hilderson et al., 2013; Lopez et al., 2015).

AYAs also reported wanting specific details on how the transfer process would work. They recognized that they would go through a “system change” and wanted information on how this would be carried out (Bomba et al., 2017). They wanted lists of things to do in preparation (Lopez et al., 2015). Information on topics such as making appointments, filling prescriptions, communication with providers, and identifying future healthcare providers was valued (DiFazio et al., 2014; Lochridge et al., 2013; Lopez et al., 2015; Porter et al., 2017). They expected this to be provided in the pediatric setting or through programing directly aimed at emerging young adults (Garvey et al., 2014). They felt this would appropriately shape their expectations (Garvey et al., 2014). Providing this earlier rather than later was desired (DiFazio et al., 2014; Hilliard et al., 2014).

In providing this developmental-specific knowledge, AYAs desired for their pediatric providers to talk to and address them directly to model adult healthcare. They wanted their provider to address them and not their parents as this allowed them to reflect more on themselves and their healthcare needs (Burström et al., 2017; Tierney et al., 2013). Having the opportunity to discuss their opinions made them feel like an active partner in their care (Hilderson et al., 2013). Though AYAs wanted to be directly addressed and to have their pediatric providers should move away from the “parent-centric” approach, they still expressed a desire for their parents to remain involved while they were preparing for transition (Ritholz et al., 2014).

Another common suggestion to improve transition preparation was to engage AYAs with peers who had similar experiences. They felt that meeting with their peers would help them to learn how to prepare for transition (Morsa et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2017; Wright et al., 2016). Transition was seen as a challenging time for AYAs, and peers could be a resource (Burström et al., 2017; Lochridge et al., 2013; Lopez et al., 2015; Wright et al., 2016). Peers could provide support and mentorship for life before and after transition (Bomba et al., 2017; Freeman et al., 2018; Garvey et al., 2014; Lopez et al., 2015; Morsa et al., 2018; Porter et al., 2017). Peers could assist AYAs in developing communication skills (Burström et al., 2017). They could talk about issues that affect them daily such as friends, work, family planning, or any of the number of issues which would affect them in the future (Bomba et al., 2017; Hilderson et al., 2013). It did not matter if these peers came from similar backgrounds or had similar demographic characteristics (Lopez et al., 2015).

AYAs also spoke of the importance of coordination between pediatric and adult healthcare settings as a strategy to improve transition; they wanted the two systems to work together to ease the transfer process. AYAs felt that there should be communication between these two systems to help with continuity of care (Bomba et al., 2017; DiFazio et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2011; Nicholas et al., 2018). It was suggested that a period of overlap or having joint visits with the pediatric and adult providers could be beneficial (Bomba et al., 2017; Burström et al., 2017; Hilliard et al., 2014; Nicholas et al., 2018; Price et al., 2011). This overlap would facilitate relationship development with their future healthcare providers (Bomba et al., 2017). Meeting the team prior to transfer would help to decrease uncertainty and increase comfort with the new team (Wright et al., 2016). Finally, AYAs wanted their pediatric providers to stay connected after transition to ensure successful transfer (Ritholz et al., 2014).

To improve upon transition, AYAs talked about the importance of having a structured transition process. They wanted a formal process which introduced them to transition which offered them opportunity for learning (Bomba et al., 2017; Lochridge et al., 2013). They offered numerous suggestions for interventions to include in a structured process, including roleplaying, shadowing, providing written material, overlapping visits and engaging peers (Garvey et al., 2014; Lochridge et al., 2013; Porter et al., 2017). AYA felt that transition processes could encourage self-efficacy (Asp et al., 2015), self-advocacy, and self-management (DiFazio et al., 2014). AYAs reported that when they did not have structured preparation then transition felt like a foreign concept (Carroll, 2015).

Discussion

Due to improvements in pediatric chronic disease management increasing numbers of AYAs are transitioning to adult care. Our update of Fegran and colleagues’ metasynthesis covering qualitative research through February 2011 demonstrates increased research focus in this area. Between March 2011 and January 2019, an additional 33 articles met inclusion criteria almost doubling the previous research in this area. Our findings reaffirmed previous AYAs’ transition experiences and underscored the need to create AYA-centered transition preparation now. Our findings highlight the complexity of the transition process that requires preparation of both AYA and parent over several years of focused care coordination to ready the family for the AYA’s transition to adult care. Coordination begins in the pediatric setting but must continue in the adult care settings as the young adult learns the particulars of what to expect of their adult providers but also what their adult providers expect of them. In addition a complex transition of both parent and AYA roles occurs as the AYA prepares to enter the adult care medical complex.

Implications for Practice Translation of Consistent Research Findings

The CERQual analysis if combined with other research could make the justification for higher confidence in some of these themes. The CERQual analysis, however, can only grade the findings from the particular studies of focus in the metasynthesis and not beyond. Regardless, the CERQual analysis point at numerous areas for practice improvement and needed research. Furthermore, comparing our synthesis with the previous work of Fegran et al. we identified numerous findings that were similar and thus are now ready for practice integration. AYAs continued to report feeling unprepared for transition and identified barriers to the process (Fegran et al., 2014). Lack of preparation led to uncertainty about the new adult setting, AYAs were transferred based upon age and not readiness. They reported negative feelings toward transfer from pediatric adult care as they recognized differences between the pediatric and adult setting and formed assumptions about the adult healthcare team. Our work underscores the importance of starting transition preparation early and that that increasing knowledge and self-management is key to transition readiness. Self-management and independence need to begin in the pediatric setting with continuous support from the adult providers after transition. Shifting responsibilities between AYAs and parents was viewed as a natural yet valuable process, while AYAs recognized that the parents’ role would evolve and change overtime. Parents moved from being primary caregivers to a supportive role; however, they still held a critical role in assisting the AYA with communication with new adult providers. Parents often remembered medical history and could help to avoid misunderstandings with providers. They could be valuable during initial visits to adult healthcare and a resource for decision-making. These are important factors to consider when developing a transition program or facilitating transition from pediatric to adult care.

Our metasynthesis also found similar reports of AYA grieving the loss of longstanding pediatric relationships (Fegran et al., 2014). Upon meeting their new adult providers, they experienced negative first encounters due to their perceived impersonal and disease-focused approach of adult healthcare (Fegran et al., 2014). Effort should be made to prepare AYA for the change in environment and for ways to self-advocate within their new medical teams. There should also be steps taken to increase AYA-centered communication and approaches within adult healthcare practices. AYAs are a specific population with unique developmental needs that need to be addressed. This is critical as our findings demonstrate that when expectations were met, they were more likely to stay engaged with care.

Many nursing and medical organizations including the Society of Pediatric Nurses (Betz, 2017), the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners (2020), the American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing (2015), the National Association of School Nurses (2019), and American Academy of Pediatrics (2018) have published consensus statements or adopted recommendations which provide guidance on how nursing can take a leading role in improving transition processes. Nursing is aptly suited to improve transition processes and encourage both the pediatric and adult healthcare systems to view this issue from a family-focused and developmental age perspective. The Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ developed in 2009 to improve transition and have been promoted by Got Transition®, a cooperative agreement between the Maternal and Child Health Bureau and the National Alliance to Advance Adolescent Health (Got Transition, 2014b). This approach, though medical-centric, provides a framework for assessing progress towards improving transition processes. Though transition has been a recognized problem for almost 30 years and it has been a decade since the development of the core elements, the themes that arose in the 33 primary studies illustrated continued deficiencies in each of these six areas of transition. Table 2 provides a list of the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ and links them to AYAs’ reports from the metasynthesis regarding deficiencies and recommendation for practice improvements which are ready for translation. Nursing across the spectrum of chronic diseases need to assess their own clinical practices to identify strengths and deficiencies they are facing within their own setting. Efforts should be taken to address limitations in their current transition processes.

Table 2.

Deficiencies found in addressing Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition(TM) and recommendations based upon findings from metasynthesis.

| Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ | Deficiencies Reported by AYA | Recommendations Reported by AYA Ready for Practice Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Transition Policy | • Not told far enough in advance about transition • Report unsystematic transfers • Do not know what to expect with transition |

• Provide details about process and resources during transition • Talk about transition beginning at early ages • Provide a structured program to encourage preparation |

| Transition Tracking and Monitoring | • Not discussed by AYA in primary studies | • Not discussed by AYA in the primary studies |

| Transition Readiness | • Lack knowledge and ability to describe their disease condition, history, and current treatments • Not ready for disease self-management • Do not know when to seek care • Do not feel emotionally ready • Caregivers have trouble letting go of responsibilities |

• Provide repetitive education about disease conditions to help AYA become more knowledgeable about their medical conditions and needs • Encourage and support AYA to gradually assume more independence and responsibility as they grow up • Base transition upon individual readiness and not just age • Make AYA active participants in their pending transfer and encourage caregivers to support new roles for AYA |

| Transition Planning | • Do not know how to identify healthcare providers post-transition • AYA reported not knowing how to navigate insurance or how to obtain appointments with their insurance |

• If the healthcare system allows, AYAs should be encouraged to meet and get to know their adult healthcare providers prior to transition. • Encourage active, independent AYA role in clinic appointments earlier • Utilize peers to help provide insight into what to expect • Provide age pertinent information and resources (i.e. information on drugs, alcohol, pregnancy, lifestyle) • Provide information on transition in a creative method (i.e. workshop, shadowing, programming) |

| Transfer of Care | • Do not know how to identify new providers • Report poor communication between pediatric and adult providers |

• Provide assistance in identifying providers • Coordinate care between pediatric and adult providers or offer “joint clinics” |

| Transfer Complete | • Found adult providers’ expectations were unreasonable • Report having poor experiences with new adult providers and subsequently developing mistrust of the new providers • Reported periods of interruption to care • Reported negative feelings regarding environment or approach with first visits to adult providers settings |

• Encourage adult practices to tailor their care towards AYA and their needs • Develop collaborations between pediatric and adult practices to ensure continuity of care • Work with adult providers to reduce inconsistencies in care post-transition • Encourage adult provider to have person-centered communication that is appropriate for youth adults • Maintain pediatric provider role after transition to ensure success |

Study Limitations

One limitation of this metasynthesis is that it did not include parent and healthcare provider perspectives. Their perspectives are also pertinent to designing healthcare transition processes and ensuring effectiveness and feasibility. Their perspectives, especially parent’s views, offer insight into aspects of transition which may be overlooked or not considered as important to AYA when preparing for transition. Similar to the prior metasynthesis, we identified studies from a variety of countries, but the studies included were still predominantly from North America and Europe. This limits our ability to comment on culture issues which may be relevant. In addition, this metasynthesis was limited because a librarian did not independently conduct the literature search. Instead, the first author developed an updated search strategy based upon Fegran and colleagues’ work. A health sciences librarian was then consulted to confirm the quality of the search strategy. After this the first author independently conducted the search. Finally, many of the primary studies had minor methodological limitations. Researchers did not always describe their study procedures with enough detail to determine if their recruitment strategy was appropriate, if data collection was protected from bias, if the relationship between the researcher and participant had been considered for potential sources of bias, if ethical issues were considered, or if the data had been analyzed with rigor. As publishing limitations could have prevented adequate description of study methods, it was assumed that the lack of description did not presume lack of rigor. Though researchers may have carried out rigorous research, they did not provide enough details in their publications. Further details about research strategy could have increased the appraised validity of studies or possibly reduced the validity. Given the increasing use of supplementary materials in online publishing, qualitative and other researchers must begin to provide more details about their study procedures so that metasynthesis researchers can assess the evidence more accurately. It might become necessary to reach out to these researchers for these details as methods to translate qualitative research findings into practice using metasynthesis becomes more acceptable.

Implications for Future Research

Research is needed to evaluate the impact of wrap around services with equal focus on pediatric and adult care facilities. Thus far the majority of this research has been conducted by pediatric providers; however, including adult providers is critical to solving the transition process for AYAs with chronic illness. Further research is needed to understand what factors may help to better facilitate relationships between AYA and their new adult healthcare providers. This could include assessing healthcare provider and staff communication, roles of healthcare providers and staff, and clinic structure/processes. For existing transition programs, efforts should be taken to assess for deficiencies in meeting the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition™ such as those identified within this metasynthesis and actions should be taken to address any concerns found. AYAs and families should be included in this process to increase the effectiveness of changes made. In addition, the role of nurses should expand when possible to take on more responsibility for improving transition processes as their training encompasses both knowledge of disease treatment and methods for improving disease self-management. For example, in the United States the role of the family nurse practitioner should be assessed, as they could engage in care of AYAs across the transition process and remain involved in the AYAs care as a consistent healthcare provider across the settings.

Family research should examine the evolving roles of both parent and AYA, including the impact on and care needs within the adult care environment. The most vulnerable time for the transitioning AYA is the time immediately after transfer. New findings from this metasynthesis underscore role transition of both parent and AYA in conjunction with a need for adult providers to recognize and provide additional supports for both during this initial transition timeframe. AYAs reported that parents should continue to have a role post-transition; however, they did not clearly define this role. Further research should be completed to understand these roles and how they could impact transition success.

Conclusions

This metasynthesis has demonstrated a call to arms for improvement in transition processes because AYA with chronic illness continue to report leaving pediatric care without adequate preparation. AYAs reported that deficiencies within our current transition processes do not adequately prepare them to assume full responsibility for their healthcare or to reduce their concerns about the impending change to their healthcare team. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that despite numerous consensus statements and guidelines from national organization both in nursing and medicine, transition care is not being consistently implemented. Transition is an inevitable process for every child diagnosed with a chronic condition. It requires involvement of both the pediatric and adult healthcare systems. Current systems of care must be changed to reduce the impact on the AYA and their health. Youth with chronic conditions need adult healthcare providers who focus on chronic condition management, which includes attention to the specific developmental needs of young adults after transition so that they are not lost in traditional adult-focused systems of care.

Nursing can and should take a larger role assessing their clinical environments for adherence to the current guidelines on transition. Pediatric and adult nurses must take ownership of implementing clinical practices to provide mechanisms for supporting AYAs and families during transition preparation and transfer into adult care systems. They need to collaborate with their medical colleagues to raise awareness of the negative impact of transition, while also advocating for evidence-based practice changes to improve transition preparation and transfer. While disease management is an essential focus of clinical encounters, transition preparation should be given just as much attention for AYAs. The knowledge and skills to be gained from transition care will be vital to accessing and participating in disease management after transfer to adult healthcare. Evidence-based transition care processes must become the norm and not the exception.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

AYAs report transition processes are deficient in meeting the Got Transition® Six Core Elements.

Healthcare providers must design system processes to provide resources necessary for transition.

Research identifying family processes to support AYA assumption of responsibility is needed.

Several evidence-based recommendations are ready for implementation as confirmed by findings.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers T32NR015426 and F31NR018574. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen D, Channon S, Lowes L, Atwell C, & Lane C (2011). Behind the scenes: The changing roles of parents in the transition from child to adult diabetes service. Diabetic Medicine, 28(8), 994–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Ambulatory Care Nursing. (2015). Joint statement: The role of the nurse leader in care coordination and transition management across the health care continuum. Nursing Economics, 33(5), 281–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asp A, Bratt E-L, & Bramhagen A-C (2015). Transfer to adult care: Experiences of young adults with congenital heart disease. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(5), e3–e10. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Halanych JH, Howard TH, Hilliard LM, & Lebensburger JD (2015). Exploring adult care experiences and barriers to transition in adult patients with sickle cell disease. International Journal of Hematology & Therapy, 1(1), doi: 10.15436/2381-1404.15.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz CL (2017). SPN position statement: Transition of pediatric patients into adult care. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 35, 160–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blinder MA, Duh MS, Sasane M, Trahey A, Paley C, & Vekeman F (2015). Age-related emergency department reliance in patients with sickle cell disease. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 49(4), 513–522.e1. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.12.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bomba F, Herrmann-Garitz C, Schmidt J, Schmidt S, & Thyen U (2017). An assessment of the experiences and needs of adolescents with chronic conditions in transitional care: A qualitative study to develop a patient education programme. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 652–666. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burström Å, Bratt E-L, Frenckner B, Nisell M, Hanséus K, Rydberg A, & Öjmyr-Joelsson M (2017). Adolescents with congenital heart disease: Their opinions about the preparation for transfer to adult care. European Journal of Pediatrics, 176(7), 881–889. doi: 10.1007/s00431-017-2917-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burström Å, Öjmyr-Joelsson M, Bratt E-L, Lundell B, & Nisell M (2016). Adolescents with congenital heart disease and their parents: Needs before transfer to adult care. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 31(5), 399–404. doi: 10.1097/jcn.0000000000000288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll EM (2015). Health care transition experiences of young adults with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 30(5), e157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catena G, Rempel GR, Kovacs AH, Rankin KN, Muhll IV, & Mackie AS (2018). “Not such a kid thing anymore”: Young adults’ perspectives on transfer from paediatric to adult cardiology care. Child: Care, Health & Development, 44(4), 592–598. doi: 10.1111/cch.12564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva PSA, & Fishman LN (2014). Transition of the patient with IBD from pediatric to adult care—An assessment of current evidence. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, 20(8), 1458–1464. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiFazio RL, Harris M, Vessey JA, Glader L, & Shanske S (2014). Opportunities lost and found: Experiences of patients with cerebral palsy and their parents transitioning from pediatric to adult healthcare. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 7(1), 17–31. doi: 10.3233/PRM-140276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fegran L, Hall EOC, Uhrenfeldt L, Aagaard H, & Ludvigsen MS (2014). Adolescents’ and young adults’ transition experiences when transferring from paediatric to adult care: A qualitative metasynthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(1), 123–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M, Stewart D, Cunningham CE, & Gorter JW (2018). “If I had been given that information back then”: An interpretive description exploring the information needs of adults with cerebral palsy looking back on their transition to adulthood. Child: Care, Health & Development, 44(5), 689–696. doi: 10.1111/cch.12579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost JR, Cherry RK, Oyeku SO, Faro EZ, Crosby LE, Britto M, Tuchman LK, Horn IB, Homer CJ, & Jain A (2016). Improving sickle cell transitions of care through health information technology. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 51(1 Suppl 1), S17–S23. doi.org/ 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garvey KC, Beste MG, Luff D, Atakov-Castillo A, Wolpert HA, & Ritholz MD (2014). Experiences of health care transition voiced by young adults with type 1 diabetes: A qualitative study. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics, 5, 191–198. doi: 10.2147/AHMT.S67943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Got Transition. (2014a). Introduction. Retrieved from https://www.gottransition.org/providers/integrating.cfm

- Got Transition. (2014b). The six core elements of health care transition 2.0. Retrieved from https://www.gottransition.org/providers/index.cfm

- Gray WN, Schaefer MR, Resmini-Rawlinson A, & Wagoner ST (2018). Barriers to transition from pediatric to adult care: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 43(5), 488–502. doi.org/ 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greutmann M, Tobler D, Kovacs AH, Greutmann-Yantiri M, Haile SR, Held L, Ivanov J, Williams WG, Oechslin EN, Silversides CK, & Colman JM (2015). Increasing mortality burden among adults with complex congenital heart disease. Congenital Heart Disease, 10(2), 117–127. doi.org/ 10.1111/chd.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilderson D, Eyckmans L, Van der Elst K, Westhovens R, Wouters C, & Moons P (2013). Transfer from paediatric rheumatology to the adult rheumatology setting: Experiences and expectations of young adults with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Clinical Rheumatology, 32(5), 575–583. doi: 10.1007/s10067-012-2135-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilliard ME, Perlus JG, Clark LM, Haynie DL, Plotnick LP, Guttmann-Bauman I, & Iannotti RJ (2014). Perspectives from before and after the pediatric to adult care transition: A mixed-methods study in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 37(2), 346–354. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang JS, Gottschalk M, Pian M, Dillon L, Barajas D, & Bartholomew LK (2011). Transition to adult care: Systematic assessment of adolescents with chronic illnesses and their medical teams. The Journal of Pediatrics, 159(6), 994–998.e992. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrun-Harris LA, McManus MA, Ilango SM, Cyr M, McLellan SB, Mann MY, & White PH (2018). Transition planning among US youth with and without special health care deeds. Pediatrics, 142(4), e20180194. doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2018-0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S, Glenton C, Munthe-Kaas H, Carlsen B, Colvin CJ, Gülmezoglu M, … Rashidian A (2015). Using qualitative evidence in decision making for health and social interventions: An approach to assess confidence in findings from Qualitative Evidence Syntheses (GRADE-CERQual). PLOS Medicine, 12(10), e1001895. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SA, & Noyes J (2013). Effective process or dangerous precipice: Qualitative comparative embedded case study with young people with epilepsy and their parents during transition from children’s to adult services. BMC Pediatrics, 13, 169–169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-13-169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochridge J, Wolff J, Oliva M, & O’Sullivan-Oliveira J (2013). Perceptions of solid organ transplant recipients regarding self-care management and transitioning. Pediatric Nursing, 39(2), 81–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez KN, Karlsten M, Bonaduce De Nigris F, King J, Salciccioli K, Jiang A, … Thompson D (2015). Understanding age-based transition needs: Perspectives from adolescents and adults with congenital heart disease. Congenital Heart Disease, 10(6), 561–571. doi: 10.1111/chd.12283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado DM, Galano E, de Menezes Succi RC, Vieira CM, & Turato ER (2016). Adolescents growing with HIV/AIDS: Experiences of the transition from pediatrics to adult care. The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 20(3), 229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morsa M, Lombrail P, Boudailliez B, Godot C, Jeantils V, & Gagnayre R (2018). A qualitative study on the educational needs of young people with chronic conditions transitioning from pediatric to adult care. Patient Preference and Adherence, 12, 2649–2660. doi: 10.2147/ppa.s184991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, Lestishock L, Disabato J, Daley AM, Cuomo C, Seeley A, & Chouteau W (2020). NAPNAP position statement on supporting the transition from pediatric to adult focused health care. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 34(4), 390–394. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2020.03.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of School Nurses (2019). Transition planning for students with healthcare needs. Retrieved from https://www.nasn.org/advocacy/professional-practice-documents/position-statements/ps-transition

- Nguyen T, Henderson D, Stewart D, Hlyva O, Punthakee Z, & Gorter JW (2016). You never transition alone! Exploring the experiences of youth with chronic health conditions, parents and healthcare providers on self-management. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(4), 464–472. doi: 10.1111/cch.12334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas DB, Kaufman M, Pinsk M, Samuel S, Hamiwka L, & Molzahn AE (2018). Examining the transition from child to adult care in chronic kidney disease: An open exploratory approach. Nephrology Nursing Journal, 45(6), 553–559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philbin MM, Tanner AE, Chambers BD, Ma A, Ware S, Lee S, Fortenberry JD, & The Adolescent Trials Network (2017). Transitioning HIV-infected adolescents to adult care at 14 clinics across the United States: Using adolescent and adult providers’ insights to create multi-level solutions to address transition barriers. AIDS Care, 29(10), 1227–1234. doi.org/ 10.1080/09540121.2017.1338655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plevinsky JM, Gumidyala AP, & Fishman LN (2015). Transition experience of young adults with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD): A mixed methods study. Child: Care, Health & Development, 41(5), 755–761. doi: 10.1111/cch.12213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JS, Graff JC, Lopez AD, & Hankins JS (2014). Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: Perspectives on the family role. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(2), 158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2013.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JS, Rupff RJ, Hankins JS, Zhao MS, & Wesley KM (2017). Pediatric to adult care transition: Perspectives of young adults with sickle cell disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 42(9), 1016–1027. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsx088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CS, Corbett S, Lewis-Barned N, Morgan J, Oliver LE, & Dovey-Pearce G (2011). Implementing a transition pathway in diabetes: A qualitative study of the experiences and suggestions of young people with diabetes. Child: Care, Health and Development, 37(6), 852–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quillen J, Bradley H, & Calamaro C (2017). Identifying barriers among childhood cancer survivors transitioning to adult health care. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 34(1), 20–27. doi.org/ 10.1177/1043454216631953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridosh M, Braun P, Roux G, Bellin M, & Sawin K (2011). Transition in young adults with spina bifida: A qualitative study. Child: Care, Health & Development, 37(6), 866–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01329.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritholz MD, Wolpert H, Beste M, Atakov-Castillo A, Luff D, & Garvey KC (2014). Patient-provider relationships across the transition from pediatric to adult diabetes care: A qualitative study. The Diabetes Educator, 40(1), 40–47. doi: 10.1177/0145721713513177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryscavage P, Macharia T, Patel D, Palmeiro R, & Tepper V (2016). Linkage to and retention in care following healthcare transition from pediatric to adult HIV care. AIDS Care, 28(5), 561–565. doi.org/ 10.1080/09540121.2015.1131967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, & Barroso J (2007). Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Sobota AE, Umeh E, & Mack JW (2015). Young adult perspectives on a successful transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease. Journal of Hematology Research, 2(1), 17–24. doi: 10.12974/2312-5411.2015.02.01.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney S, Deaton C, Jones A, Oxley H, Biesty J, & Kirk S (2013). Liminality and transfer to adult services: A qualitative investigation involving young people with cystic fibrosis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(6), 738–746. doi:/ 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.04.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Transition G (2014). The six core elements of health care transition 2.0. Retrieved from https://www.gottransition.org/providers/index.cfm

- White P, & Cooley W (2018). Supporting the health care transition from adolescence to adulthood in the medical home. Pediatrics, 142(5) Retrieved from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/142/5/e20182587.full.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Elwell L, McDonagh JE, Kelly DA, & Wray J (2016). “Are these adult doctors gonna know me?” Experiences of transition for young people with a liver transplant. Pediatric Transplantation, 20(7), 912–920. doi: 10.1111/petr.12777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.