Abstract

Three studies examined the effects of receiving fewer signs of positive feedback than others on social media. In Study 1, adolescents (N = 613, M Age = 14.3 years) who were randomly assigned to receive few (vs. many) likes during a standardized social media interaction felt more strongly rejected, and reported more negative affect and more negative thoughts about themselves. In Study 2 (N=145), negative responses to receiving fewer likes were associated with greater depressive symptoms reported day-to-day and at the end of the school year. Study 3 (N = 579) replicated Study 1’s main effect of receiving fewer likes and showed that adolescents who already experienced peer victimization at school were the most vulnerable. The findings raise the possibility that technology which makes it easier for adolescents to compare their social status online—even when there is no chance to share explicitly negative comments—could be a risk factor that accelerates the onset of internalizing symptoms among vulnerable youth.

Keywords: adolescence, social media, social validation, evaluative feedback, depression, stress coping

In the last few years, there has been a worldwide increase in the use of Internet applications to publicly share content with others (i.e., social media), and this has created unprecedented opportunities for social connection, self-expression, and feedback. This trend has been especially pronounced among adolescents, who are typically the first to adopt new technologies (Spies Shapiro & Margolin, 2014). In the U.S., over 80 percent of 14- to 22-year-olds are currently active, daily users of social media (Rideout & Fox, 2018); nearly 70% say that they check their social media applications multiple times per day. Co-occurring with this increase in social media use has been a dramatic and alarming increase in youth mental health problems, leading some to question whether social media might be contributing to this trend (Beyens, Frison, & Eggermont, 2016; Blomfield-Neira & Barber, 2014; Kross et al., 2013; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015; Shakya & Christakis, 2017; Vernon, Modecki, & Barber, 2017).

New technological advances like social media, however, are unlikely to be uniformly good or uniformly bad (Odgers, 2018). Therefore, it is critical for research to understand for whom, and under what conditions interactions on social media might cause emotional distress. Odgers (2018) has argued that many interactions on social media are harmless or even positive, but some could magnify social-emotional vulnerabilities among subgroups of adolescents who are already struggling. Yet to date only a few small studies have begun to investigate this (e.g., Forest & Wood, 2012), and none have focused on the specific mechanisms that could explain it.

Our research examined one common experience on social media that could be a risk factor for youth: insufficient social validation, defined as not getting enough positive feedback from others about the content one has shared. We hypothesized that insufficient social validation could threaten adolescents’ need for status and acceptance and pose a risk factor for the development of internalizing symptoms, even in the absence of active, targeted social rejection or exclusion like cyberbullying or peer harassment. Furthermore, adolescents who are the most attuned to threats to their status—for instance, those who are suffering ongoing peer victimization—may be most negatively affected. If this proved to be the case, it would suggest that a common medium that millions of young people are using might contribute to feelings of inadequacy and reduced emotional well-being among vulnerable adolescents.

Adolescent Sensitivity to Social Status

Our research is grounded in the adolescent social-affective learning model (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Yeager, Dahl, & Dweck, 2018; Yeager, Lee, & Dahl, 2017) and we tie this together with the need-threat model (Williams, 2009) that has been used extensively to understand the effects of ostracism in adult populations. According to the adolescent social-affective learning model, adolescence is a developmental period characterized by heightened motivational and affective sensitivity to experiences that signal differences in social status among peers. Status-relevant experiences can therefore evoke intense emotional reactions. Many status-relevant experiences engender positive feelings (e.g. pride, respect) and can help adolescents adapt and thrive. However many status-relevant experiences are negative (being excluded, ignored, rejected, or humiliated), and are risk factors for internalizing mental health problems (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Past experiments with adolescents have shown that peer rejection events—those that threaten adolescents’ developmentally salient need for status and acceptance—can elicit psychological pain and emotional distress (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Guyer, Caouette, Lee, & Ruiz, 2014; Masten et al., 2011; Sebastian, Viding, Williams, & Blakemore, 2010; Silk et al., 2014; Thomaes et al., 2010). Furthermore, adolescents’ neural and affective responses to peer rejection events (e.g., being excluded from an online ball toss game; being disliked by interaction partners) have been associated with elevated risks for internalizing symptoms, most notably depression (Masten et al., 2011; Prinstein & Aikins, 2004; Silk et al., 2014). However, all past research on this topic focused on peer rejection events that involved explicitly negative feedback (e.g., dislike, exclusion). Prior experimental work on adolescents has not examined a network of people posting self-disclosures and exchanging “likes” as a means to gain public, quantifiable signs of social status as is done on typical social media platforms. Thus, there is not yet strong evidence about adolescents’ affective responses to insufficiently positive feedback that can threaten their needs for status.

Social media is increasingly a place where adolescents’ status is on public display, and therefore it could pose a risk for emotional distress among those whose social status is threatened. Users on social media typically contribute content—a link, a picture, a quip, or a personal disclosure—and expect that others will indicate their approval by giving it a like (i.e., clicking a button that says “like”) or something similar. Likes on social media are quantifiable, public signs of status (see Nesi & Prinstein, 2018 for digital status-seeking on social media), and so getting another person to like one’s self-expression elicits feelings of validation, conferring positive status and regard, and thus leads to positive emotions (Davey, Allen, Harrison, Dwyer, & Yücel, 2009; Gunther Moor, van Leijenhorst, Rombouts, Crone, & Van der Molen, 2010). By the same token, getting fewer likes than others can be a sign that one has low social status. In fact, a national survey of youth in the U.S. (Rideout & Fox, 2018) found that 56% of respondents said it was a negative experience to post content on social media and not receive enough likes. Similarly, some studies have suggested that positive evaluative feedback (e.g., likes) on social media has made unhealthy social comparisons salient (Appel, Gerlach, & Crusius, 2016; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015), especially among social or emotionally vulnerable individuals (Appel, Crusius, & Gerlach, 2015; Blease, 2015; Burrow & Rainone, 2017; Forest & Wood, 2012).

One lens for understanding this complex set of issues is the need-threat model of ostracism (Williams, 2009). In the need-threat model, being excluded or ignored by others without any explanation or overtly negative behaviors—that is, being ostracized (Williams, 2009)—threatens basic psychological needs, such as the need for social status and acceptance. Research on the need-threat model has shown that ostracism can elicit negative affect (Sebastian et al., 2010), and reduce self-esteem (Jamieson, Harkins, & Williams, 2010; Leary, Terdal, Tambor, & Downs, 1995) even in the absence of active, targeted negative feedback such as bullying, harassment, or aggression.

Insufficient validation on social media is a modern form of ostracism that may elicit feelings of rejection, a sign that adolescents’ developmentally salient need for status and acceptance have been threatened (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Dahl, Allen, Wilbrecht, & Suleiman, 2018; Yeager et al., 2018). Insufficient validation may then trigger consequences of this need threat, such as negative affect (e.g., feeling distressed, sad, anxious, or embarrassed), and negative self-relevant cognitions (viewing oneself as less worthy, or less likable), which are known risk factors for depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001; Masten et al., 2011; Slavich, O’Donovan, Epel, & Kemeny, 2010). Evidence supporting our proposal could provide mechanistic insight into the conditions under which social media use can be associated with poor mental health, and to whom insufficient validation could pose greater risks (Blomfield-Neira & Barber, 2014; Feinstein et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2016; Steers, Wickham, & Acitelli, 2014).

The Present Research

The primary goals of the current research were to: (1) test whether insufficient positive feedback on social media causes rejection feelings and negative affective-cognitive responses among adolescents during a socially stressful developmental stage (the first year of high school; Crosnoe, 2011, Yeager, Lee, & Jamieson, 2016) (Study 1); (2) examine whether feelings of rejection elicited from insufficient validation on social media predicted elevated risks for depression (Study 2); and (3) examine whether the effects of insufficient positive social media feedback were more pronounced among adolescents who more frequently experienced peer victimization in face-to-face peer contexts (Study 3).

Study 1 used a random-assignment experimental approach. This was important because the vast majority of studies in this area have used correlational designs that preclude direct claims about the causal effect of social media. We adapted a standardized social media interaction with a group of electronic confederates, previously used with adults (Schneider et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2015), to make it age-appropriate for adolescents. Previous studies with college students and older adults found that this manipulation (e.g., receiving few likes) created short-term threats to needs to belonging, control, and self-esteem relative to many likes condition (Schneider et al., 2017; Wolf et al., 2015). However, no prior studies have administered this task or similar social media-like interaction paradigms with adolescents, who are thought to be more vulnerable to status-relevant feedback and stress-induced internalizing disorders than adults (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Hammen, 2005). In school settings, we assigned adolescents to receive few likes (our operationalization of insufficient social validation) or many likes (our operationalization of sufficient social validation). Analyses tested whether getting few likes (but no explicitly negative feedback) would (a) increase feelings of rejection, which would be a sign that adolescents were interpreting the experience as a threat to their status and acceptance, and (b) elicit negative affect and self-relevant cognitions, which are consequences of need threat.

Next, Study 2 examined whether adolescents who felt more strongly rejected by insufficient validation on the social media task might show heightened prospective risk for depression. To this end, Study 2 collected additional data from a subset of participants from two of the schools in Study 1 (N=145), including 10 days of diary reports of stressors and stress responses, and an 8-month follow-up on depressive symptoms. Study 2 examined whether adolescents who felt more intensely rejected by receiving few likes also reported greater negative affect and cognitions in response to daily stressors over 10 days, measured via a daily diary, and were more likely to show increases in depressive symptoms, measured 8 months later. Study 2 is unique in that it can contribute to identifying one mechanistic explanation for how positive social media feedback might worsen adolescents’ mental health outcomes. Moreover, Study 2 provides the ecological validity of the experimental task, that has long been of interest to developmentalists (c.f., Bronfenbrenner, 1977).

Finally, Study 3 replicated effects of Study 1 in a well-powered sample, and tested for a key moderator: adolescents’ reported frequency of prior peer victimization. This is the first direct test of Odgers’ (2018) hypothesis that social media might serve to magnify existing social-emotional vulnerabilities in youth. We expected that victimized adolescents might be more vulnerable to insufficient positive validation on social media for two complementary reasons. First, insufficient positive validation is attributionally-ambiguous, in that it is rarely obvious to a person why others did not like one’s post. A teen could ask: was it because they were distracted? Busy? Not on social media? Or do they truly dislike me or intentionally ignore me? Victimized youth might be more likely to “go beyond the information given” (Bruner, 1957) and attribute the cause of ambiguous social media interactions to negative characteristics of themselves (e.g., “maybe I’m not a likable person.”) and therefore exhibit stronger rejection distress and negative internalizing-type affect (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Schacter, White, Chang, & Juvonen, 2015). Second, peer victimization in face-to-face contexts might increase sensitivity to any experience relevant to social status, and therefore enhance the effects of insufficient validation on social media.

Study 1

Methods

Participants

Data were collected from N=613 ninth-grade adolescents (Mage= 14.3, SDage= 0.70) who were enrolled in a summer prep program, a public magnet school, or one of three urban public high schools. The sample size was determined by our attempt to recruit a maximum number of active consent students from the schools during the 2015–2017 school years; the decision to stop data collection was made without knowledge of the results of the studies. All schools were located in middle- to upper-middle class neighborhoods with varying degrees of racial/ethnic diversity. The sample included 55% females; 44.9% White/European American, 31.8% Hispanic/Latinx, 3.5% Black/African American, 12.3% Asian/Asian American/Pacific Islanders, 0.3% Native American Indians, and 6.8% multi-racial or another race/ethnicity. See Table 1 and Table S1 in the online supplement for demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

| Study 1 (N=613) |

Study 2 (N=145) |

Study 3 (N=579) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| School Site | a summer prep program, a public magnet school, three urban public high school | a public magnet school, an urban public high school | four urban public high school |

| Mean age (SD) | 14.3 (0.70) | 14.8 (0.55) | 15.3 (0.40) |

| Sex | |||

| % Boys | 45.0% | 48.6% | 50.3% |

| % Girls | 55.0% | 51.4% | 49.7% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| % White/European American | 44.9% | 57.6% | 53.5% |

| % Hispanic/Latinx | 31.8% | 19.4% | 32.5% |

| % Black/African American | 3.5% | 1.4% | 3.8% |

| % Asian/Pacific Islander | 12.3% | 14.6% | 6.5% |

| % Native American Indian | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.2% |

| % Multi-racial/Other | 6.8% | 6.9% | 3.5% |

| Maternal Education | |||

| % No high school degree | 15.4% | 2.0% | 5.6% |

| % High school degree | 23.1% | 14.3% | 19.3% |

| % 2-year associate degree | 5.5% | 5.1% | 5.1% |

| % 4-year college degree | 25.5% | 36.7% | 32.7% |

| % Master’s degree or above | 20.9% | 35.7% | 23.4% |

| % Participant did not know | 9.5% | 6.1% | 14.0% |

| Internalizing Symptoms | |||

| CDI score (SD) | 0.42 (0.32) | 0.46 (0.30) | 0.45 (0.32) |

Procedure

Participation occurred during the fall semester of 9th-grade (or, for one school, the summer before 9th-grade) in 2016–17. Data collection occurred in school classrooms or computer labs. Research assistants blind to condition assignment and to hypotheses verbally informed participants that they could skip any questions or withdraw from the study at any phase without penalty. Participants reported baseline psychosocial characteristics (i.e., depressive symptoms) 2–3 weeks before the social media task in a separate session. We did not detect any pre-existing differences in depressive symptoms and other psychological characteristics between randomly assigned groups (see the online supplement Table S2).

On the day that the social media task was administered, researchers informed students that they were invited to help the researchers pilot a new program called a “Get-to-Know-People Task,” purportedly designed to connect people. Participants were told that they would spend the next 3 minutes virtually interacting with other people on the task and then provide feedback on a brief questionnaire afterward. In actuality, these other people were pre-programmed computer scripts generated from pilot studies with hundreds of actual high school adolescents (see online supplement). Cardboard dividers or screen filters were set up on individual seats to ensure participants’ privacy as well as to minimize potential disruption from adjacent peers.

Computer scripts randomly assigned adolescents to either the “few likes” (insufficient social validation) or “many likes” (sufficient social validation) condition. We oversampled the “few likes” condition (N=454 vs. N=159) to ensure sufficient statistical power to analyze individual differences in acute rejection feelings within “few likes” condition (see Study 2). After the 3-minute interaction, students completed a brief questionnaire assessing post-task feelings of rejection, negative affect, negative self-referent cognitions, and open-ended feedback about their reactions to other people on the task.

At the end of the task, participants were debriefed to ensure that they felt no distress from having received few likes; they were thanked for their participation and compensated with a small gift (e.g., a college keychain worth under $5). Out of an abundance of caution, in a subsample (N=145) we tested whether random assignment to insufficient social validation (few likes) condition caused long-term changes in global self-esteem (Rosenberg, 1965) and perceived global stress (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). As expected, analyses found no long-term manipulation effects, b= 0.03, p= .765 for 8-month global self-esteem; b= −0.48, p= .424 for 8-month global stress, consistent with the conclusion that receiving few likes was meaningful in the moment (and therefore useful for testing the hypotheses), but does not cause enduring harm.

Social Media Task.

We adapted a paradigm developed by Wolf and colleagues (2015) to manipulate the level of social validation received by participants: (1) For credibility purposes, we collected actual high school students’ profiles from pilot studies and used them to create four parallel versions of the task with varying profile descriptions; (2) Our task included a “ranking board” that displayed the real-time rank order of the number of likes; and (3) The position of others’ profiles was randomized to create a variety of visual appearances, in order to minimize suspicion in the field setting (see online supplement). In a preliminary analysis, task versions did not significantly moderate adolescents’ acute negative responses, ps > .20, so task version is ignored in all subsequent analyses.

Participants were instructed that during the 3-minute interaction with a group of other people, they would read and react to each other’s profiles (that were written by actual high school students in pilot studies). Participants typed in their initials and then selected an avatar (a cartoon depiction to represent them during the task). Participants wrote a brief self-descriptive paragraph (up to 400 English characters) to ostensibly introduce themselves to other people during the interaction. Written instructions read:

“Write something you would like to say about yourself - anything you want to share. For instance, students usually write about their favorite movies, books, music, sports team, or hobbies. Also, you could write about your typical weekend plans, extracurricular activities, or any clubs you’re in. Feel free to add #Hashtags if you can think of words or phrases that represent who you are!”.

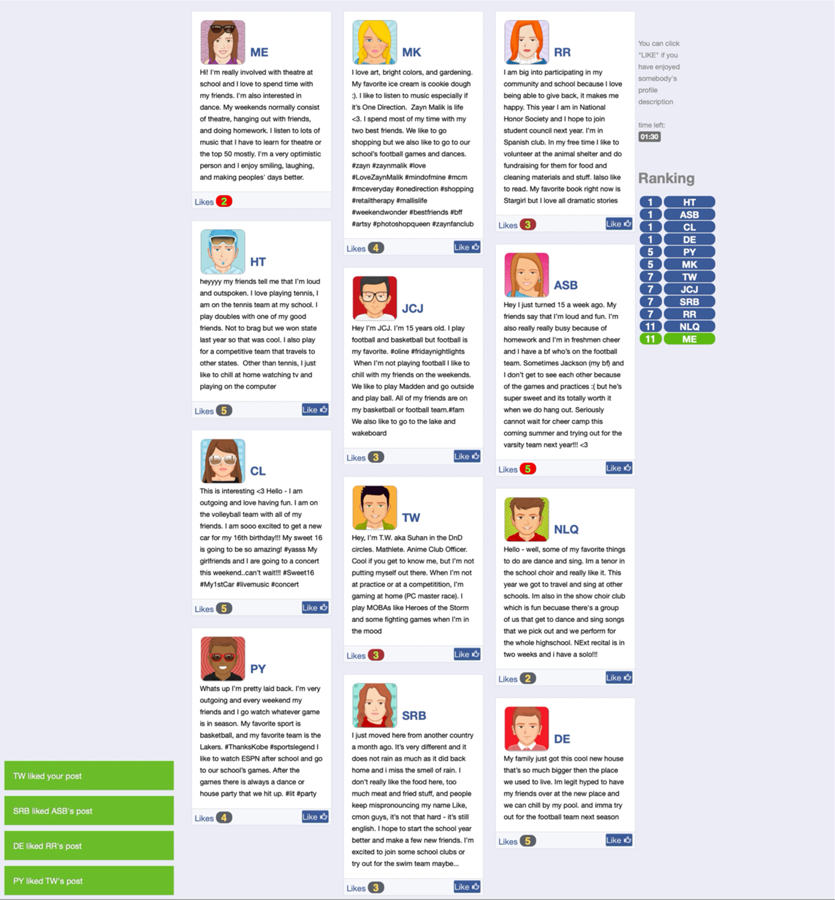

Before connecting, participants learned that they could endorse others’ profiles by clicking a like button, similar to the like button on real-world social media platforms, such as Facebook, Instagram, etc. See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An example of social media task stimuli, few likes condition.

Note: During the three-minute online interaction, participants were instructed to interact with eleven other people seemingly same-age peers, who were in fact controlled by pre-programmed computer scripts. Participant’s profile was always displayed on the top left corner, whereas others’ profiles were randomly displayed. When people received a like from another person, it updated the total number of likes below each profile, popped up a green notification window at the bottom left corner of the screen, and changed the rank order on the ranking board at the right corner, all of which made the experience of receiving likes highly salient.

Participants were presented with one of four equivalent task versions and were randomly assigned to either “few likes” condition (insufficient social validation) or “many likes” condition (sufficient social validation). In reality, other players’ like distributions were determined by pre-programmed computer scripts. In the few likes condition, participants received only two likes (approximately 18% of the maximum number of likes; comparable to the number of ball tosses in the Cyberball (Williams & Jarvis, 2006) exclusion condition from eleven people, which placed them at the bottom of the ranking board (12th place out of 12 people). In contrast, in the many likes condition, participants were endorsed with nine likes (approximately 82%), which placed them in the 2nd place out of 12 people. Meanwhile, the number of likes others received varied within a range of 3 to 10 likes (mean= 6.4, median= 6), which remained identical across task versions or likes manipulation conditions. Time schedules of likes distribution were randomly sampled between 10,000ms and 180,000ms and consistently applied across unique trials to make them more natural.

Suspicion Check.

At the end of the study, participants were given an opportunity to leave open-ended feedback about their task experience. A pair of trained research assistants coded participants’ open-ended feedback to detect any suspicion about the manipulation (inter-coder agreement ranged between 88% and 99%); 27 out of total 613 participants (4.4%) were coded as expressing suspicion about the task—e.g., asking whether other people were real—which is a low rate. To produce a conservative intent-to-treat effect, we kept these participants in the final sample for the primary analyses, but removing these participants’ data produced the same substantive conclusions (see Table S4 in the online supplement).

The social media task program, task stimuli, examples of adolescents’ profiles, and syntax for data analyses are posted online (osf.io/skzx6/).

Measures

Post-Task Survey Questions.

Feelings of rejection were measured with a single item: “I felt rejected by others during the task” (1=Strongly disagree ~ 7=Strongly agree). Higher values indicate more intense feelings of rejection following the social media interaction.

Negative affect was assessed with an average composite of three items: perceived stress, sadness, and anxiety. A single item measured perceived stress: “The Get-To-Know-People task was stressful” (1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree; linearly converted to a 5-point scale). Supplementing this, participants also reported feelings of sadness and anxiety (1=Not at all ~ 5= A great deal; inter-item correlation rs= .35 ~ .51, ps < .001).

Negative self-referent cognitions were measured with negative self-attributions, negative state self-esteem, and coping appraisals: (1) negative self-attributions were assessed with a single item, “Maybe I’m just not a likable person”; (2) negative state self-esteem was measured with two items: e.g., “How good or bad about yourself did the Get-To-Know-People task make you feel?”, “During the Get-To-Know-People task, I felt like a person of worth, at least on an equal basis with others (reversed),” r = .48, p < .001. Responses were rated on a 5-point scale (1= Not at all ~ 5= A great deal) and higher values correspond to more negative state self-concept; (3) coping appraisal was assessed with three items: e.g., “I felt like I could not handle the stress that I experienced during the Get-To-Know-People task”. Responses were rated on a 7-point scale (1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree; linearly converted to a 5-point scale) and higher values indicated more negative coping appraisal (inter-item correlation rs= .30 ~ .36, ps < .001). These three sub-concepts were aggregated by computing an unweighted average composite score of negative self-referent cognitions. See the online supplement Table S3 for item-level correlations.

Results

Main Effects of Number of Social Media Likes

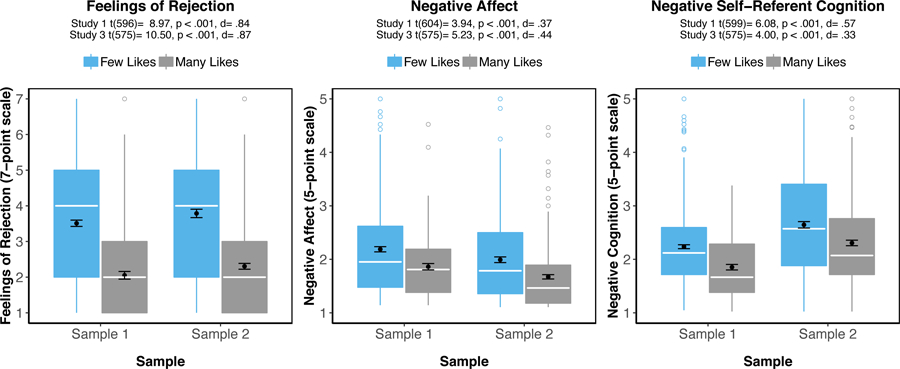

Adolescents reported significantly greater feelings of rejection when they were randomly assigned to receive few likes, relative to when they received many likes, Mfew likes= 3.51, SDfew likes= 1.86; Mmany likes= 2.05, SDmany likes= 1.34, t(596) = 8.97, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .84. See Figure 2. Thus, insufficient social validation caused an increase in feelings of rejection relative to sufficient social validation, even though no participants in our study received negative feedback (i.e., no bullying or harassment).

Figure 2.

Main effects of social media task social validation on adolescents’ feelings of rejection, negative affect, and negative self-referent cognitions, in Study 1 and 3.

Note: In Study 1 (N=613), Few Likes condition (N=454) vs. Many Likes condition (N=159); In Study 3 (N=579), Few Likes condition (N=279) vs. Many Likes condition (N=300); Black dots denote group means, black lines indicate standard errors of group means, and white lines indicate group median levels. Differences in degrees of freedom across outcomes within a study are due to small differences in participant non-response for a given item.

Analyses next examined whether these feelings of rejection might translate into risk factors for the development of depression: negative affect and negative self-referent cognitions. Preliminary analyses indicated that, as expected by the cognitive model of depression (Hankin & Abramson, 2001), feelings of rejection were correlated with negative affect, r= .52, p < .001, and negative self-referent cognitions, r= .62, p < .001.

Receiving few likes, relative to many likes, led to significantly more intense negative affect (feeling stressed, sad, and anxious, α = .66), Mfew likes= 1.94, SDfew likes= 0.97; Mmany likes= 1.61, SDmany likes= 0.69, t(604)= 3.94, p < .001, d= .37, and negative self-referent cognitions (wondering whether they were not likable, reporting lower state self-esteem, and thinking they could not handle the demands, α = .66), Mfew likes= 2.13, SDfew likes= 0.81; Mmany likes= 1.69, SDmany likes= 0.65, t(599) = 6.08, p < .001, d = .57, both of which are risk factors for depression (Figure 2 and Table S4 in the online supplement report the results for individual items).

Gender and Race/Ethnicity Moderation

Analyses did not find moderation by gender. As in past research (Hankin & Abramson, 2001; Nesi & Prinstein, 2015), girls exhibited more negative internalizing responses overall: Feelings of rejection (Mboys= 2.83, SDboys= 1.78; Mgirls= 3.37, SDgirls= 1.89, t(589)= 3.47, p < .001), negative affect (Mboys= 1.70, SDboys= 0.91; Mgirls= 1.97, SDgirls= 0.91, t(596)= 3.51, p < .001), and negative self-referent cognitions (Mboys= 1.92, SDboys= 0.83; Mgirls= 2.09, SDgirls= 0.76, t(592)= 2.34, p = .02). However, girls and boys were not differentially impacted by the manipulation (that is, few likes), interaction ps > .20. See online supplement Table S5.

In addition, we explored whether racial/ethnic minority status moderated how adolescents responded to insufficient positive feedback on the social media task. We did not expect it would because our experimental task randomly displayed a diverse group of adolescent profiles with varying skin tones and physical appearances to rule out racial ingroup vs. outgroup exclusion effects. Consistent with our expectation, we did not find significant moderation effects by adolescents’ racial/ethnic minority status (such as, being identified as non-White/other racial or ethnic groups), interaction ps > .15. See online supplement Table S6.

These absent moderation effects by gender and race/ethnicity suggest that insufficient positive validation on social media can be impactful, almost regardless of adolescents’ demographic backgrounds.

Study 2

Study 2 tested whether adolescents who experienced more intense feelings of rejection when receiving insufficient social validation on social media (i.e., in the few likes condition) also coped poorly with real-world, day-to-day social stressors and showed a greater increase in depressive symptoms over time. To answer these questions, a sub-sample of participants from Study 1 was tracked during a 10-day daily diary and at an 8-month longitudinal assessment.

Methods

Participants

A total of N=174 (98.3%) students from two schools in Study 1 consented to participate in a more intensive longitudinal study involving up to 10-days of daily diaries. The subsample of Study 2 participants did not differ from Study 1 participants in terms of demographics and baseline depressive symptoms. Of those who participated in daily diary surveys and completed the social media task, N=145 had been randomly assigned to few likes condition (insufficient social validation) during the social media task, and thus constituted the primary Study 2 analytic sample. See Table 1 and Table S7 for demographic characteristics. None of the other schools who provided data for Study 1 participated in this longitudinal study; thus, Study 2 reports all data available to test the present hypotheses.

Procedure and Measures

Daily Diary Surveys.

Before the social media task administration, participants completed a daily survey over ten days during afternoon classes (between 1 p.m. to 4:30 p.m.). Students used computers or smartphones to respond. Students reported on events that occurred within the last 24 hours, and on their reactions to the events. Participants took approximately 5–10 minutes each day to complete the questionnaire. The completion rate for the daily surveys was satisfactory (80% ~ 100% across days, see Table S8).

Participants were asked to report up to two daily negative events in open-ended prompts that read: e.g., “Please write about one negative thing that happened today or that you thought a lot about today. Just write enough so we can understand what it was (5–10 words).” Participants then rated the perceived intensity of negativity using a 5-point scale (1= Not at all negative ~ 5= Extremely negative). In parallel with Study 1, participants’ daily negative affect and cognitions in response to daily stressors were assessed. Daily negative affect was assessed with a composite of daily stress, sadness, and anxiety. Level-1 inter-item correlations were rs= .30 ~ .40, ps < .001. Daily negative cognitions were measured with a composite of two sub-concepts: (1) daily maladaptive coping appraisal, saying they can’t handle the demand from the negative events; and (2) daily ruminative thinking, saying they can’t stop thinking about the negative events happened today (1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree). Level-1 inter-item correlations were rs= .54 ~ .73, ps < .001. See Table S9 in the online supplement.

Depressive Symptoms at 8-Month Follow-up.

We administered the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI), full version (Kovacs, 1992) to track longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms over 8 months. The CDI scale was administered at the beginning of ninth-grade school year (approximately two to three weeks before social media task administration); and once again at the end of ninth-grade school year. One item related to suicidal ideation was removed from the questionnaire resulting in a total of 26 items for the full inventory. Each item asked participants to report which of three levels of a symptom described their feelings best in the past two weeks (e.g., 2= “I am sad all the time,” 1= “I am sad many times,” 0= “I am sad once in a while”). Average scores (ranging between 0 and 2) were computed and then weighted with a total number of items to create a sum composite score (ranging between 0 and 52) at baseline (α = .88) and 8-month follow-up (α = .89) respectively. To measure 8-month increases in depressive symptoms, baseline CDI sum score was subtracted from the 8-month CDI sum score, so that a higher positive number indicates greater prospective increases in depressive symptoms over an 8-month period (M = −1.02, SD = 5.53, range = −28.2 ~ 16).

Results

Daily Diary Analytic Approach

Daily diary analyses were conducted in R using lme4 (Bates, Mächler, Bolker, & Walker, 2015) and lmerTest packages (Kuznetsova, Brockhoff, & Christensen, 2015). Daily survey responses (level 1) were nested within students (level 2). Multilevel analyses examined whether adolescents who felt more rejected by insufficient social validation (on the Study 1 social media task) also exhibited a stronger association between daily social stressors and negative affect or cognition. We assumed that adolescents who felt worse and thought more poorly of themselves when socially stressful events happened could be characterized as coping poorly.

To classify the intensity of the daily social stressors (the Level-1 predictor), two independent coders coded open-ended negative events (% agreement between coders mean 97.3%, min 90.2% ~ max 99.9% across event categories) and gave it a “1” if the event described any social evaluative domain (see Yeager, Lee, & Jamieson, 2016 for the coding scheme). To minimize measurement errors, we computed the average intensity of up to two daily negative social events to index how intensely negative social stressors occurred each day. Those who did not report any negative social events were re-coded with the lowest intensity (=1 out of 5-point scale) to avoid listwise deletion. The intensity of daily social stressors (Level 1-predictor) was person-mean centered to examine the within-person slopes. Random slope models were specified as below. Daily negative affect and cognitions for day i of student j were predicted by the cross-level interaction of intensity of daily social stressors (Level-1) and feelings of rejection after insufficient social validation (few likes) on the social media task (Level-2):

Level 1 (day level):

Level 2 (person level):

Where and . Here, the focal test is the significance of γ11 parameter. We predicted that adolescents who expressed greater rejection feelings after insufficient social validation (few likes) on social media might exhibit more intense negative affect and cognitions on days with intense social stressors.

Increased Negative Affective and Cognitive Reactivity in Response to Daily Stressors

As a preliminary matter, daily negative affect and negative cognitions repeatedly assessed over ten days in naturalistic social settings were associated with concurrent depressive symptoms, rs = .35 ~ .37, ps < .001, as expected.

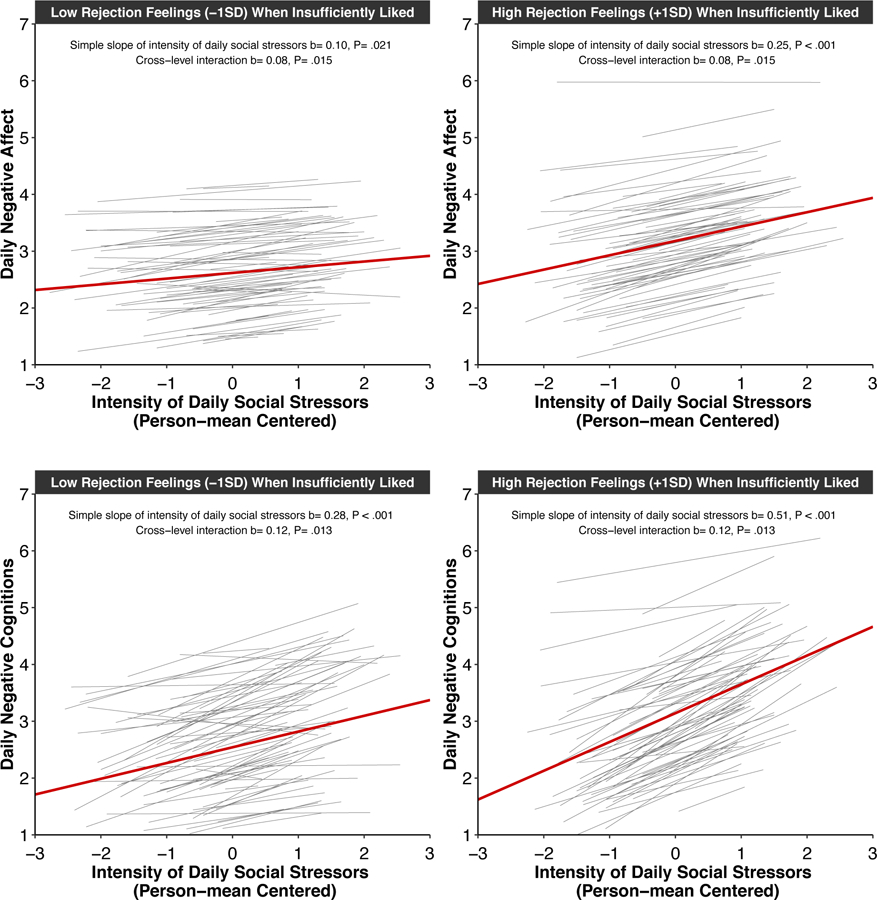

Next, there was a Daily Stressor (Level-1) × Social Media Feelings of Rejection (Level-2) cross-level interaction predicting daily negative affect, b= 0.08, SE=0.03, t(95)= 2.48, p= .015, and daily negative cognitions, b= 0.12, SE=0.05, t(109)= 2.53, p= .013. See Figure 3 and Table S10 in the online supplement. As predicted, adolescents with higher feelings of rejection in response to insufficient social validation (few likes) exhibited a stronger association between the intensity of daily social stressors and both daily negative affect and daily negative cognitions, relative to those who reported lower feelings of rejection after insufficient validation.

Figure 3.

Adolescents’ feelings of rejection after insufficient social validation on a social media task predicted daily negative affective and cognitive reactivity, in Study 2.

Note: Level 1 (day level) N= 1,266, Level 2 (person level) N= 145, Gray lines represent person-specific fitted random slopes from multilevel models in which daily negative affect (top row) and daily negative cognitions (bottom row) are predicted by the intensity of daily social stressors (person-mean centered). Red lines indicate the group average fixed-effect slopes, estimated at low (−1SD, left panel) vs. high (+1SD, right panel) feelings of rejection after insufficient social validation (few likes) on the social media task. b= unstandardized betas.

We probed these cross-level interactions by estimating the within-person slopes for daily stress among adolescents who reported high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) feelings of rejection after insufficient social validation. Among adolescents with higher rejection feelings (+1 SD) after the social media task, days with more negative social stressors were accompanied by greater negative affect, b= 0.25, SE= 0.04, t(106)= 5.90, p < .001, and negative cognitions, b= 0.51, SE= 0.06, t(119)= 8.06, p < .001. Among adolescents with lower feelings of rejection (−1 SD) after the social media task—those who seemed to cope better with insufficient social validation on social media—the intensity of daily negative social stressors was associated with daily negative affective and cognitive reactivity about half as much as those with higher rejection feelings after the social media task: negative affect, b= 0.10, SE= 0.04, t(84)= 2.34, p= .021; negative cognitions, b= 0.28, SE= 0.06, t(95)= 4.37, p < .001. See Figure 3 and Table S10. Supplementary analyses with sub-constructs of daily negative affect (see Figure S1) and daily negative cognitions (see Figure S2 in the online supplement) supported the same conclusions.

Increases in Depressive Symptoms at 8-Month Follow-Up

Two methods tested whether adolescents who experienced more acute feelings of rejection after few likes on social media would also exhibit an increase in depressive symptoms over time. First, ordinary linear regression models found that acute rejection feelings after insufficient likes predicted 8-month increases in depressive symptoms, while controlling for baseline depressive symptoms, b= 1.12, SE= 0.49, t(122)= 2.28, p= .025, β= 0.20 (see Table 2 Model I). Results did not change when controlling for gender (a known correlate of depression; Hankin & Abramson, 2001), b= 1.00, SE= 0.47, t(121)= 2.33, p= .022, β= 0.20 (Table 2 Model II). Second, a logistic regression found that acute rejection feelings after insufficient likes significantly predicted a binary outcome of clinically significant depression at 8-month follow-up (coded 1 if the 8-month CDI sum scores were above a standard cutoff score of 19 out of 52, which is suitable for non-clinical samples; Timbremont, Braet, & Dreessen, 2004), b= 1.00, SE= 0.45, z= 2.21, p= .027, OR=2.72, 95% CI[1.19, 7.22] (see Table 2 Model III). When controlling for gender, the effect of rejection feelings remained significant, b= 1.11, SE= 0.49, z= 2.29, p= .022, OR=3.06, 95% CI[1.26, 8.85] (Table 2 Model IV).

Table 2.

Social media feelings of rejection predicted 8-month prospective increases in depressive symptoms and the likelihoods of developing clinically significant depression, in Study 2.

| Linear regression (DV= 8-month increases in depressive symptoms) |

Logistic regression (DV= 8-month clinical depression binary outcome) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Model II | Model III | Model IV | |

| (Intercept) | −1.190* (0.461) | −2.851*** (0.668) | −3.793*** (0.736) | −4.807* (1.170) |

| Social media feelings of rejection (z-scored) | 1.123* (0.494) | 1.105* (0.474) | 1.001* (0.453) | 1.110* (0.486) |

| Covariates: | ||||

| Baseline CDI scores (z-scored) | −2.331*** (0.482) | −2.511*** (0.467) | 2.448*** (0.574) | 2.594*** (0.635) |

| Female | 2.977** (0.896) | 1.205** (0.880) | ||

| R2 | 0.165 | 0.235 | ||

| P | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 |

| N | 125 | 125 | 125 | 125 |

Note: Analysis included adolescents who completed baseline and 8-month CDI inventory. In Model I and II, 8-month increases in CDI scores were computed by 8-month CDI sum scores minus baseline CDI sum scores. In Model III and IV, logistic regression models used a binary outcome of clinically significant depression (8-month CDI sum scores above 19 out of 52).

p < .001

p < .01

p < .05.

Finally, feelings of rejection after receiving sufficient likes did not significantly predict increases in depressive symptoms 8 months later, b= −1.57, SE= 1.85, t(21)= −0.85, p= .406, β= - 0.26; neither did it predict the likelihood of developing clinical depression, b= −0.96, SE= 0.87, z= −1.11, p= .267, OR= 0.38, 95% CI[0.05, 1.74]. However, this exploratory analysis within sufficient likes condition is limited due to small sample size (N=24).

Study 3

Is social media use only harmful for those who are already struggling with face-to-face peer interactions, as some have suggested (Odgers, 2018)? To answer this, Study 3 randomly assigned likes to adolescents and tested for differential effects among adolescents who had been victimized in prior face-to-face peer interactions.

Our predictions were rooted in longstanding social-psychological models of attributional ambiguity. Namely, we expected that in the causally ambiguous context of insufficiently positive social media feedback, face-to-face peer experiences may provide a contextual framework through which adolescents “go beyond the information given” (Bruner, 1957) to interpret causally-ambiguous information as negative (for a related argument, see Crocker, Voelkl, Testa, & Major, 1991; Mendes, Major, McCoy, & Blascovich, 2008; Thomaes, Sedikides, Reijntjes, Brummelman, & Bushman, 2015). A secondary, though no less important, contribution of Study 3 was to replicate main effects of the manipulation observed in Study 1 in another large sample.

Methods

Participants

During the 2017–18 school year, a total N=735 ninth-grade students from four urban public high schools were recruited to participate. Of this sample, N=127 students did not complete the social media task and N=29 students did not answer post-task survey questionnaire due to various circumstances (e.g., conflicts with class schedules, absences, or voluntary withdrawal). The final sample included N=579 ninth-grade adolescents (Mage = 15.3, SDage = 0.40) who returned an active parental and student consent forms during recruitment visits, completed a social media task with a random assignment of likes feedback condition, and answered a questionnaire following the task. This sample size yielded >99% power to detect the effect size for feelings of rejection in Study 1 (d= .84) at p < .05. The Study 3 sample included 49.7% females; 53.5% White/European American, 32.5% Hispanic/Latinx, 3.8% Black/African American, 6.0% Asian/Asian American, 0.5% Pacific Islander, 0.2% Native American Indians/Alaskan, and 3.5% were multi-racial or another race/ethnicity. See Table 1 and Table S11.

Procedure

Data collection occurred during the spring semester of the 2017–18 school year. Participants were invited to two study sessions (~ 30 minutes) in school computer labs. On the first day, participants completed a comprehensive self-report survey that assessed face-to-face peer victimization experience along with other demographic and psychosocial characteristics.

On the following day, participants were invited to a 2nd session in which they were instructed to complete a “Get-To-Know-People” task. The task materials, visual and text stimuli, and written instructions were identical to the materials used in Study 1. Again, participants were randomly assigned to receive few likes (N=279) vs. many likes (N=300) feedback from other players. Supplementary analyses indicated that the random assignment was successful, no pre-existing group differences were detected (see Table S12). Prior to the task, participants were verbally informed that they could skip any questions or withdraw from the study at any point without penalty. Upon completion, students were compensated with a small gift (e.g., a college wristband under $2 value). Students were verbally de-briefed about the purpose and nature of the computerized task. They were told that it did not involve actual likes given by real people, but instead the feedback was simulated by computer scripts for scientific research purposes.

Measures

Prior Peer Victimization.

We administered six items from the overt and relational victimization scale (Prinstein, Boergers, & Vernberg, 2001). Participants were asked: In your school, in the past two weeks, how often did the following things happen to you? Using a 5-point scale (1=Never, 2=Once or twice, 3=A few times, 4=About once a week; 5=A few times a week), participants rated how frequently they were (1) hit/ kicked/ pushed by another student in a mean way; (2) threatened to be hurt/ beaten up; (3) left out from an activity or a conversation; (4) not invited to a party or a social event; (5) not sit near at lunch or in class; and (6) got rumors or lies spread out to hurt my reputation. For moderation analyses, we used a composite score averaging all six items (α= .74; M= 1.30, SD= 0.45, Min 1 ~ Max 3.83, 53% adolescents with non-zero experience of face-to-face peer victimization in the past two weeks), in which a higher score indicates more frequent exposures to peer victimization.

Social Media Pre-Task Expectation.

Prior to task administration, students reported their pre-existing expectation of receiving positive feedback: “I expect that everyone will like me after reading my profile” (1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree; M= 3.69; SD= 1.44).

Social Media Post-Task Responses.

We administered a post-task questionnaire that was similar to Study 1 at the completion of the social media task interaction. A single item (“I felt rejected by others during the Get-To-Know-People task”) measured feelings of rejection (1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree). Negative affect was assessed with a composite score of four items: feeling stressful, sad, anxious, and embarrassed (1=Not at all ~ 5= A great deal), α = .74; rs = .37 ~ .54, ps < .001. Negative self-referent cognitions were measured with two sub-constructs: (1) negative state self-esteem (Thomaes et al., 2010), with three items (e.g., I feel satisfied with/ I feel good about/ I am proud of myself right now; 1=Not at all ~ 5= A great deal; reverse-coded), α = .97; rs = .85 ~ .95, ps < .001; and (2) characterological trait attributions (adapted from Schacter, White, Chang, & Juvonen, 2015), two items (e.g., Maybe I’m not a likable person; Kids like me are just not meant to be popular; 1= Strongly disagree ~ 7= Strongly agree), α = .80; r = .66, p < .001. See Table S13 for item-level correlations.

Results

Replication of Main Effects of Social Media Likes

Consistent with Study 1, adolescents who were randomly assigned to receive few likes during the social media task reported significantly greater feelings of rejection, Mfew likes= 3.79, SDfew likes= 1.95; Mmany likes= 2.30, SDmany likes= 1.42; t(575)= 10.50, p < .001, d= .87; and higher levels of negative affect (stressed, sad, anxious, and embarrassed), relative to those assigned to receive many likes, Mfew likes= 1.84, SDfew likes= 0.85; Mmany likes= 1.51, SDmany likes= 0.63; t(575)= 5.23, p < .001, d= .44. Those assigned to the few likes condition also reported significantly lower state self-esteem (feeling less positively about the self after the interaction), Mfew likes= 3.15, SDfew likes= 1.30; Mmany likes= 3.50, SDmany likes= 1.15; t(575)= −3.44, p < .001, d= −.29; and more intense characterological trait attributions, viewing themselves as not likable or not meant to be popular, Mfew likes= 2.85, SDfew likes= 1.47; Mmany likes= 2.41, SDmany likes= 1.35; t(573)= 3.81, p < .001, d= .32. See Figure 2, and also Table S14 in the online supplement for the results broken out by the individual items. Taken together, Study 3 replicated the main effects from Study 1 with similar effect sizes.

Moderation Analyses by Prior Peer Victimization

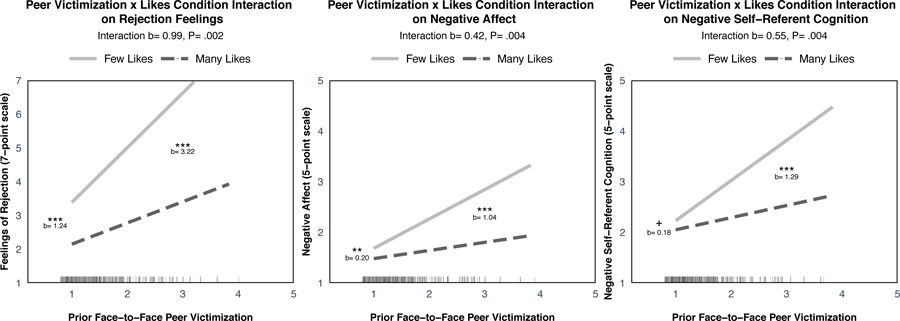

We observed a significant moderation effect on feelings of rejection. In a linear regression, the Prior Peer Victimization × Social Media Likes Condition interaction was significant, b= 0.99, t= 3.07, p= .002, β= 0.45, with region of significance (ROS) [0.40 ~ 5.00] at p < .05 level. Simple effects were estimated at 1 (no face-to-face peer victimization in the past two weeks) vs. 3 (moderate-high levels of face-to-face peer victimization) of the victimization composite scale value because −1SD from the sample mean (= 0.83) was a non-existent scale value. Simple effects analyses revealed that adolescents with moderate to high levels of prior peer victimization (centered at 3) reported significantly more intense rejection feelings when receiving few likes, relative to many likes (simple effect of likes condition b= 3.22, p < .001). Adolescents with no prior peer victimization experience in the past two weeks (centered at 1) reported significant yet weaker differences in rejection feelings between few vs. many likes condition (simple effect of likes condition b= 1.24, t= 7.12, p < .001). See Figure 4, first panel, and Table S15 in the online supplement.

Figure 4.

Adolescents’ prior peer victimization moderated feelings of rejection, negative affect, and negative self-referent cognitive responses to insufficient social validation on a social media task, in Study 3.

Note: N= 503, moderation analyses excluded participants who did not complete the peer victimization scale prior to the social media task administration. Interaction effects were tested in ordinary linear regression models with a full continuous moderator. We plotted simple slopes of prior face-to-face peer victimization at Few Likes (solid light gray lines) vs. Many Likes (dashed dark gray lines) condition. Simple effects of likes condition were tested at “no prior peer victimization” (at composite score= 1 of x-axis) vs. “moderate-high levels of prior peer victimization” (at composite score= 3 of x-axis). b= unstandardized betas; *** p < .001, ** p < .01, * p < .05, + p < .10.

Next, a significant Face-to-Face Peer Victimization × Social Media Likes Condition interaction emerged for negative affect, b= 0.42, t= 2.89, p= .004, β= 0.19, ROS [0.92 ~ 5.00] at p < .05 level. Simple effects tests showed that adolescents with moderate to high levels of face-to-face peer victimization (at 3) reported significantly more intense negative affect when receiving few likes, relative to many likes (simple effect of few likes condition at 3, b= 1.04, t= 4.07, p < .001; simple effect at 1, b= 0.20, t= 2.59, p= .01). See Figure 4, second panel, and Table S15. And there was a significant Face-to-Face Peer Victimization × Social Media Likes Condition interaction on negative self-referent cognitions, b= 0.55, t= 2.92, p= .004, β= 0.25, ROS [1.03 ~ 5.00] at p < .05 level. A simple effect analysis found a significant condition effect among those with moderate to high levels of face-to-face peer victimization (b= 1.29, t= 3.85, p < .001), but not among those with no face-to-face victimization (b= 0.18, t= 1.76, p= .08) (see Figure 4, third panel, and Table S15).

We did not detect any significant moderation effects on any outcomes by adolescents’ pre-task expectation of getting positive feedback, ps > .20. This is important for clarifying the moderating effect of victimization. It was not that victimized youth were expecting not to be liked; it was that, when insufficiently liked, they were differentially harmed by the experience.

Discussion

As social media has penetrated adolescents’ social lives, researchers have called for more theory-driven, ecologically valid, scientific studies of how social media affects adolescent emotional well-being and social development (Crone & Konijn, 2018; George & Odgers, 2015; Odgers, 2018; Spies Shapiro & Margolin, 2014). Here we tried to meet these calls in new ways. First, we drew on the adolescent social-affective learning model (Yeager, Lee, & Dahl, 2017) and the need-threat model (Williams, 2009) to generate predictions about the specific social media interactions which could relate to internalizing disorders and why. Further, we tested hypotheses about the subgroups of adolescents who might be most vulnerable.

Our studies found that insufficient validation on social media was a brief yet powerful emotional event that threatened adolescents’ social status and elicited emotional distress. And rejection feelings arising from insufficiently positive validation during a brief social media interaction were correlated with ecologically-valid risk factors for depression in adolescence (maladaptive day-to-day stress appraisals) and greater increases in depressive symptoms over 8 months. These findings are consistent with the adolescent social-affective learning model (Crone & Dahl, 2012; Yeager et al., 2018, 2017) and the need-threat literature (Jamieson et al., 2010; Sebastian et al., 2010; Wolf et al., 2015) in the sense that social media evaluative feedback that publicly signals undesirable social status triggered negative internalizing-type affective responses that are known risk factors for depression. And these findings are in line with previous research showing that adolescents’ affective sensitivity to peer rejection events is associated with prospective risk for depression (Masten et al., 2011; Nolan, Flynn, & Garber, 2003; Silk et al., 2014; Slavich et al., 2010).

Importantly, the rejection feelings adolescents reported were elicited from insufficient positive feedback, not explicit targeted rejecting feedback (e.g., dislike, exclusion, cyberbullying). This distinction is important to consider in future work on the adolescent social-affective learning model. It suggests that adolescents are highly attuned to symbolic social status cues communicated through differing amounts of positive evaluative feedback on social media and experience emotional distress when their momentary social status does not measure up to others. Study 2 uncovered a potential mechanism through which positive social media evaluative feedback could contribute to worse mental health outcomes during adolescence, which as mentioned is a developmental period when affective sensitivity to social status rises (see Crone & Dahl, 2012; Yeager et al., 2018).

Another contribution of our research was to confirm recent claims that some youth are more vulnerable to the negative effects of social media than others (Odgers, 2018). Study 3 found that previously victimized adolescents reported stronger rejection feelings, more negative internalizing-type affect, and greater characterological self-trait attributions (e.g., “maybe I am not a likable person”) in response to receiving few likes from unacquainted others (Study 3). These findings add to the prior literature on peer victimization by highlighting victimized youths’ cognitive vulnerabilities in using self-blaming attributions in response to causally ambiguous social interaction contexts (Graham & Juvonen, 1998; Schacter et al., 2015). Moreover, we extend prior research that victimized youths are more likely to be targeted for cyberbullying and peer harassment in online contexts (Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, 2014), to also examine emotional distress in responses to a simple lack of enthusiastic social validation in online contexts.

These findings have some relevance for practice. In particular, they raise the intriguing possibility that social media use may contribute to a negative evaluative feedback loop, differentially for teens who had been victimized in the past, and future research can test this directly. For example, victimized teens may turn to social media, posting self-disclosing content, with the hope of receiving validation from peers to satisfy their unmet needs for status and acceptance from peers. But their likes may not measure up to those garnered by others (especially their well-accepted, popular peers), leading some to feel rejected and inadequate, and also to develop more negative self theories (e.g., “I’m not a likable person”; “I’m not meant to be a high status person”). Indeed, a U.S. national survey (Rideout & Fox, 2018) found that adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms were nearly 30 percentage points more likely to say they posted content on social media that hardly received any comments or likes, relative to non-depressed counterparts (71% vs. 43%), suggesting vulnerable individuals’ impoverished positive feedback in virtual social contexts. Ironically, this might cause these social-emotionally vulnerable adolescents to turn to social media even more to avidly seek supportive social feedback, causing the initial cycle to repeat and intensify (c.f., Rideout & Fox, 2018).

From a translational research perspective, our research underscores the need to develop and test theoretically driven intervention programs that can better guide vulnerable youths to positively appraise the meaning of online social feedback. To our knowledge, no evidence-based interventions are currently available to address adolescents’ social and emotional struggles with social media feedback. Nor are most programs tailored to educate adolescents in terms of how to make sense of immense amounts of social status comparison cues on social media. Interventions might bolster vulnerable adolescents’ psychological resilience to repeated, quantifiable evaluative feedback online, or they might seek to reduce the pressure to demonstrate an unattainable social status. The next stage of research, therefore, might look into factors that buffer adolescents from the effects of social media use, and see how they can be embedded into rigorously evaluated programs.

Last but not least, methodologically the social media task adapted here with diverse adolescent profiles may prove useful as an experimental tool to investigate the developmental impact of social media across diverse groups of youth. To facilitate future research, we publicly post our experimental task stimuli and adolescent profiles database online (osf.io/skzx6/).

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current research. First, the effects of insufficient social validation reported here could actually be conservative. The range of the number of few vs. many likes feedback in our study was limited to 11 people. In real-world social media, quantified feedback may go well beyond this number, given the average size of friends network on social media (e.g., a median of 126 friends on Facebook, and 180 followers on Instagram; Rideout & Fox, 2018). Future studies should continue to alter the sizes of the groups.

Next, our study induced a single occasion of insufficient social validation in order to isolate its immediate causal effects and avoid potential ethical problems that could emerge from a stronger manipulation. In the real-world, however, repeated exposures to insufficient social validation could contribute to cycles of rejection distress and escalated internalizing symptoms. Or, alternatively, those who felt insufficiently validated might rather withdraw from the social media platforms over time or passively browse instead (though see Verduyn et al., 2015 for detrimental effects of passive social media use). Future studies should further explore the cumulative effects of insufficient social media validation and examine the alternative ways that adolescents cope with it.

Conclusion

Social media provides unique challenges and new opportunities to adolescents, parents, educators, clinicians, and engineers. By shining a light on how quantified social feedback can pose a risk for vulnerable adolescents, we hope that our results inform stakeholders and inspire improvements to platforms. For instance, it is encouraging that some social media applications have begun to acknowledge the possible negative psychological consequences of quantified evaluative feedback, and have modified (or considered doing so) platforms to not displaying real-time, quantified social validation to mitigate users’ psychological pressures (Newcomb, 2019, May 1). We also hope that our results help inform contemporary efforts to reduce adolescents’ reliance on social media (e.g., screen time features on digital devices that allow users to monitor their usage).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Support for this research came in part from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, R01 HD084772–01 awarded to authors, P2CHD042849 awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin, a William T. Grant Foundation scholars award granted to the corresponding author; and the Society for Research in Child Development Student and Early Career Council Dissertation Funding Award awarded to the first author. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funders. The authors are grateful to the students, parents, and faculty who participated in this research, and also to Dr. Andre Audette, Mallory Dobias, and undergraduate research assistants for their assistance in data collection.

References

- Appel H, Crusius J, & Gerlach AL (2015). Social comparison, envy, and depression on Facebook: A study looking at the effects of high comparison standards on depressed individuals. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 34, 277–289. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2015.34.4.277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appel H, Gerlach AL, & Crusius J (2016). The interplay between Facebook use, social comparison, envy, and depression. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.10.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, & Walker S (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67, 1–48. doi: 10.18637/jss.v067.i01 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beyens I, Frison E, & Eggermont S (2016). “I don’t want to miss a thing”: Adolescents’ fear of missing out and its relationship to adolescents’ social needs, Facebook use, and Facebook related stress. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.083 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blease CR (2015). Too many ‘friends,’ too few ‘likes’? Evolutionary psychology and ‘Facebook depression’. Review of General Psychology, 19, 1–13. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blomfield-Neira CJ, & Barber BL (2014). Social networking site use: Linked to adolescents’ social self-concept, self-esteem, and depressed mood: SNS use and adolescent indicators of adjustment. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66, 56–64. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513–531. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruner JS (1957). On perceptual readiness. Psychological Review, 64, 123–152. doi: 10.1037/h0043805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow AL, & Rainone N (2017). How many likes did I get?: Purpose moderates links between positive social media feedback and self-esteem. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 69, 232–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2016.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, & Mermelstein R (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. doi: 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Voelkl K, Testa M, & Major B (1991). Social stigma: The affective consequences of attributional ambiguity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 218–228. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-08-088579-7.50019-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, & Dahl RE (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13, 636–650. doi: 10.1038/nrn3313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crone EA, & Konijn EA (2018). Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nature Communications, 9, 1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03126-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R (2011). Fitting in, standing out: Navigating the social challenges of high school to get an education. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE, Allen NB, Wilbrecht L, & Suleiman AB (2018). Importance of investing in adolescence from a developmental science perspective. Nature, 554, 441–450. doi: 10.1038/nature25770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey CG, Allen NB, Harrison BJ, Dwyer DB, & Yücel M (2009). Being liked activates primary reward and midline self-related brain regions. Human Brain Mapping, 660–668. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, & Williams KD (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290–292. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Hershenberg R, Bhatia V, Latack JA, Meuwly N, & Davila J (2013). Negative social comparison on Facebook and depressive symptoms: Rumination as a mechanism. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 2, 161–170. doi: 10.1037/a0033111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forest AL, & Wood JV (2012). When social networking is not working: Individuals with low self-esteem recognize but do not reap the benefits of self-disclosure on Facebook. Psychological Science, 23, 295–302. doi: 10.1177/0956797611429709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George MJ, & Odgers CL (2015). Seven fears and the science of how mobile technologies may be influencing adolescents in the digital age. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10, 832–851. doi: 10.1177/1745691615596788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, & Juvonen J (1998). Self-blame and peer victimization in middle school: An attributional analysis. Developmental Psychology, 34, 587–599. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.3.587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunther Moor B, van Leijenhorst L, Rombouts SARB, Crone EA, & Van der Molen MW (2010). Do you like me? Neural correlates of social evaluation and developmental trajectories. Social Neuroscience, 5, 461–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyer AE, Caouette JD, Lee CC, & Ruiz SK (2014). Will they like me? Adolescents’ emotional responses to peer evaluation. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 38, 155–163. doi: 10.1177/0165025413515627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C (2005). Stress and depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, & Abramson LY (2001). Development of gender differences in depression: An elaborated cognitive vulnerability–transactional stress theory. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 773–796. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson JP, Harkins SG, & Williams KD (2010). Need threat can motivate performance after ostracism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36, 690–702. doi: 10.1177/0146167209358882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory: Manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski RM, Giumetti GW, Schroeder AN, & Lattanner MR (2014). Bullying in the digital age: A critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 1073–1137. doi: 10.1037/a0035618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, … Ybarra O (2013). Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS ONE, 8, e69841. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, & Christensen RHB (2015). lmerTest: Tests in linear mixed effects models (Version 2.0–29). Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lmerTest/index.html

- Leary MR, Terdal SK, Tambor ES, & Downs DL (1995). Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: The sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 518–530. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.3.518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, & Yeager DS (2019). Adolescents with an entity theory of personality are more vigilant to social status and use relational aggression to maintain social status. Social Development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin L yi, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, … Primack BA (2016). Association between social media use and depression among U.S. young adults. Depression and Anxiety, 33, 323–331. doi: 10.1002/da.22466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Eisenberger NI, Borofsky LA, McNealy K, Pfeifer JH, & Dapretto M (2011). Subgenual anterior cingulate responses to peer rejection: A marker of adolescents’ risk for depression. Development and Psychopathology, 23, 283–292. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes WB, Major B, McCoy S, & Blascovich J (2008). How attributional ambiguity shapes physiological and emotional responses to social rejection and acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 278–291. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.2.278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, & Prinstein MJ (2015). Using social media for social comparison and feedback-seeking: Gender and popularity moderate associations with depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43, 1427–1438. doi: 10.1007/s10802-015-0020-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J, & Prinstein MJ (2018). In search of likes: Longitudinal associations between adolescents’ digital status seeking and health-risk behaviors. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–9. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2018.1437733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb A (2019, May 1). Twitter and Instagram are starting to imagine a world without ‘likes’. Fortune. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2019/05/01/twitter-instagram-facebook-like-button

- Nolan SA, Flynn C, & Garber J (2003). Prospective relations between rejection and depression in young adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 745–755. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odgers C (2018). Smartphones are bad for some teens, not all. Nature, 554, 432–434. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-02109-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, & Aikins JW (2004). Cognitive moderators of the longitudinal association between peer rejection and adolescent depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 147–158. doi: 10.1023/b:jacp.0000019767.55592.63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Boergers J, & Vernberg EM (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30, 479–491. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rideout V, & Fox S (2018). Digital health practices, social media use, and mental well-being among teens and young adults in the U.S. Hopelab, 1–95. Retrieved from: http://learning.wellbeingtrust.org/be-well/digital-health-practices-social-media-use-and-mental-well-being-among-teens-and-young-adults-in-the-u-s

- Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schacter HL, White SJ, Chang VY, & Juvonen J (2015). “Why me?”: Characterological self-blame and continued victimization in the first year of middle school. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44, 446–455. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.865194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider FM, Zwillich B, Bindl MJ, Hopp FR, Reich S, & Vorderer P (2017). Social media ostracism: The effects of being excluded online. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 385–393. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sebastian C, Viding E, Williams KD, & Blakemore S-J (2010). Social brain development and the affective consequences of ostracism in adolescence. Brain and Cognition, 72, 134–145. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakya HB, & Christakis NA (2017). Association of Facebook use with compromised well-being: A longitudinal study. American Journal of Epidemiology, 185, 203–211. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JS, Siegle GJ, Lee KH, Nelson EE, Stroud LR, & Dahl RE (2014). Increased neural response to peer rejection associated with adolescent depression and pubertal development. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 9, 1798–1807. doi: 10.1093/scan/nst175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavich GM, O’Donovan A, Epel ES, & Kemeny ME (2010). Black sheep get the blues: A psychobiological model of social rejection and depression. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35, 39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spies Shapiro LA, & Margolin G (2014). Growing up wired: Social networking sites and adolescent psychosocial development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17, 1–18. doi: 10.1007/s10567-013-0135-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steers M-LN, Wickham RE, & Acitelli LK (2014). Seeing everyone else’s highlight reels: How Facebook usage is linked to depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33, 701–731. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2014.33.8.701 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes S, Reijntjes A, Orobio de Castro B, Bushman BJ, Poorthuis A, & Telch MJ (2010). I like me if you like me: On the interpersonal modulation and regulation of preadolescents’ state self-esteem. Child Development, 81, 811–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomaes S, Sedikides C, Reijntjes A, Brummelman E, & Bushman BJ (2015). Emotional contrast or compensation? How support reminders influence the pain of acute peer disapproval in preadolescents. Developmental Psychology, 51, 1438–1449. doi: 10.1037/dev0000041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C, & Dreessen L (2004). Assessing depression in youth: Relation between the Children’s Depression Inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 33, 149–157. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verduyn P, Lee DS, Park J, Shablack H, Orvell A, Bayer J, … Kross E (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective well-being: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144, 480–488. doi: 10.1037/xge0000057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernon L, Modecki KL, & Barber BL (2017). Tracking effects of problematic social networking on adolescent psychopathology: The mediating role of sleep disruptions. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46, 269–283. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD (2009). Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 41, pp. 275–314). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, & Jarvis B (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 38, 174–180. doi: 10.3758/BF03192765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf W, Levordashka A, Ruff JR, Kraaijeveld S, Lueckmann J-M, & Williams KD (2015). Ostracism Online: A social media ostracism paradigm. Behavior Research Methods, 47, 361–373. doi: 10.3758/s13428-014-0475-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Dahl RE, & Dweck CS (2018). Why interventions to influence adolescent behavior often fail but could succeed. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13, 101–122. doi: 10.1177/1745691617722620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager DS, Lee HY, & Dahl RE (2017). Competence and motivation during adolescence In Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, & Yeager DS (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (Second, pp. 431–448).

- Yeager DS, Lee HY, & Jamieson JP (2016). How to improve adolescent stress responses: Insights from integrating implicit theories of personality and biopsychosocial models. Psychological Science, 27, 1078–1091. doi: 10.1177/0956797616649604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.