Abstract

Purpose

To design, construct, and evaluate quantitative MR phantoms that mimic MRI signals from the liver with simultaneous control of three parameters: proton-density fat-fraction (PDFF), , and T1. These parameters are established biomarkers of hepatic steatosis, iron overload, and fibrosis/inflammation, respectively, which can occur simultaneously in the liver.

Methods

Phantoms including multiple vials were constructed. Peanut oil was used to modulate PDFF, MnCl2 and iron microspheres were used to modulate , and NiCl2 was used to modulate the T1 of water (T1,water). Phantoms were evaluated at both 1.5T and 3.0T using stimulated echo acquisition mode MR spectroscopy (STEAM-MRS) and chemical shift encoded (CSE) MRI. STEAM-MRS data were processed to estimate T1,water, T1,fat, , and for each vial. CSE-MRI data were processed to generate PDFF and maps, and measurements were obtained in each vial. Measurements were evaluated using linear regression and Bland-Altman analysis.

Results

High quality PDFF and maps were obtained with homogeneous values throughout each vial. High correlation was observed between imaging PDFF with target PDFF (slope=0.94–0.97, R2=0.994–0.997) and imaging with target (slope=0.84–0.88, R2=0.935–0.943) at both 1.5T and 3.0T. and were highly correlated with slope close to 1.0 at both 1.5T (slope=0.90, R2=0.988) and 3.0T (slope=0.99, R2=0.959), similar to the behavior observed in vivo. T1,water (500–1200ms) was controlled with varying NiCl2 concentration, while T1,fat (300ms) was independent of NiCl2 concentration.

Conclusion

Novel quantitative MRI phantoms that mimic the simultaneous presence of fat, iron, and fibrosis in the liver were successfully developed and validated.

Keywords

Quantitative imaging biomarkers, phantom, proton-density fat-fraction, , T1, liver

Introduction

Abnormal deposition of fat and iron in the liver, as well as cumulative scar (fibrosis) are principal histological features of many diseases in multiple organs. In the United States, there are an estimated 100 million people afflicted by non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)1, which is emerging as the leading cause of liver disease, and millions more with viral hepatitis and other forms of diffuse liver disease. Iron overload often coexists with NAFLD, and liver iron is also an important indicator of total body iron in patients with genetic hemochromatosis and those who receive multiple blood transfusions2–5. Abnormal liver fat and iron overload often lead to liver injury and fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis, liver failure and even hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)6. Importantly, fat, iron and fibrosis also commonly co-exist as key features of many other diseases involving the heart7–11, pancreas12,13, and kidney14–16, among others.

Tissue biopsy enables diagnosis of liver disease, but it is invasive, expensive, and suffers from poor sampling variability17. MRI provides multiple contrast mechanisms for the assessment of diffuse liver disease. Chemical shift encoded (CSE) MRI methods enable mapping of proton-density fat-fraction (PDFF)6,18 for liver fat quantification. Further, MRI is very sensitive to the presence of iron in tissue, which accelerates the signal decay rate, as also quantified using CSE-MRI methods19. Finally, fibrosis and inflammation increase the tissue extracellular volume, which results in increased T120. Indeed, T1 mapping has emerged over the past few years as a promising method for detection and staging of myocardial fibrosis8, as well as for assessing liver fibrosis21.

Noninvasive MRI biomarkers of fat (based on PDFF), iron (based on ), and fibrosis (based on T1) are emerging as promising quantitative biomarkers with high diagnostic performance6,8,18,19,21, and are increasingly adopted as endpoints in clinical trials for new therapeutics. However, the disease features of fat, iron and fibrosis are rarely isolated, and these three features commonly coexist to varying degrees22. This coexistence has substantial relevance because the presence of each of these disease features impacts the acquired MR signal, and therefore the ability of quantitative MRI methods to measure the other disease features. For example, the accumulation of iron leads to both increased and decreased T1, which is well known to confound the quantification of fat if it is unaccounted for in the PDFF estimation23–26. Similarly, the presence of liver fat can confound the quantification of 27,28 (i.e., small increases with increasing liver fat content, likely due to magnetic susceptibility differences between fat droplets and surrounding tissue) and the quantification of T1 with different acquisitions26,29. For these reasons, “confounder-corrected” quantitative MRI methods have been developed to measure PDFF, and T1 while correcting for relevant coexisting factors. Importantly, development and validation of these methods require MRI test objects (“phantoms”) that mimic the simultaneous presence of these three coexisting features.

Current, commercially available MRI phantoms only attempt to change one of PDFF, , and T1 independently. Quantitative fat phantoms30,31 have been developed and used in the validation of MR fat quantification methods. Modulating with chemicals (i.e., paramagnetic salts or iron oxide particles) has been demonstrated in previous works32–34. Phantoms with controlled T1 have been used in various applications35,36. In summary, previous phantoms generally mimic individual tissue features (fat, iron, or fibrosis) independently31,32,36.

However, simple combinations of the formulations applied in these PDFF, , or T1 phantoms do not mimic signal characteristics observed in tissue. A super-paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO)-based fat phantom enables the modulation of fat and iron simultaneously23. However, this phantom did not accurately mimic the single- behavior (i.e., similar observed relaxation decay for water and fat) that is observed in human liver24,25. A preliminary report of a fat-iron phantom with single- signal based on large iron particles showed promising results33,37, and another work using iron oxide particles also indicated the potential for single- signal behavior, although this was not demonstrated explicitly34. The development of phantoms that simultaneously control PDFF, (single- signal behavior: similar decay behavior of fat and water signals), T1, and other properties observed in vivo remains an unmet need for the validation and quality assurance of MRI-based methods for quantification of diffuse liver disease.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop and evaluate quantitative PDFF--T1 phantoms with the following design goals: i) simultaneous modulation of PDFF, , and T1; ii) similar relaxation rate behavior for fat and water in liver; iii) modulation of T1,water without changing T1,fat as seen in vivo.

Methods

Study Design

In this study, we first constructed a preliminary PDFF- phantom which explored two different approaches to modulate PDFF and simultaneously. Two different substances, paramagnetic salt (i.e., MnCl2) and iron microspheres, were used to control in two separate sets of vials. This phantom was used to assess different -modulating substances ( modulators) to evaluate their feasibility for replicating the single- signal behavior seen in vivo. Based on the results from the preliminary PDFF- phantom, two additional quantitative MRI phantoms were constructed: 1) a PDFF-single phantom was designed to demonstrate simultaneous control of PDFF and with single- behavior of fat and water; 2) a PDFF--T1 phantom was designed to enable simultaneous control of PDFF, , and T1,water. MR-based measurements include PDFF quantification as well as and T1 relaxometry. In addition, given the established relationship between R2 and liver iron concentration38,39, R2 relaxometry measurements were also performed.

Preliminary PDFF- Phantom

Two different methods for modulating were evaluated in the preliminary PDFF- phantom, based on paramagnetic salt MnCl2 and iron microspheres (2.9μm diameter, UMC3001, COMPEL, Bangs Labs, Fishers, IN). Two sets of vials were built with constant volume fat fraction of 20%. Details on the construction of the oil-water emulsions are provided below. The first set included five vials with varying MnCl2 concentration (1.03 mM, 1.99 mM, 2.95 mM, 3.91 mM, and 4.86 mM) to achieve varying over a range of physiological values. The second set included five vials with varying concentration of iron microspheres (5.82 μg Fe/mL, 15.39 μg Fe/mL, 24.96 μg Fe/mL, 34.53 μg Fe/mL, and 44.10 μg Fe/mL) to obtain a similar range as the first set. Each set was designed to have increasing target on the order of 100 s−1, 200 s−1, 300 s−1, 400 s−1, and 500 s−1. The required concentrations of MnCl2 and iron microspheres were based on a preliminary 3T calibration test in the absence of fat, derived below in this work: MnCl2 (mM) = 0.010× (s−1)+0.07, and iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) = 0.096× (s−1)−3.75.

PDFF-single Phantom

The purpose of this phantom was to demonstrate control of both and PDFF in each vial, with similar decay behavior of fat and water signals (i.e., “single-” signals) as has been observed in vivo in the presence of simultaneous fat and iron deposition in the liver24. Four sets of vials were constructed with varying volume fat fraction of 5%, 10%, 20% and 30% in the phantom. These volume fat fractions were chosen to cover most of PDFF observed in the liver40. For each choice of PDFF, five vials with different were constructed, with the following target values: 100 s−1, 200 s−1, 300 s−1, 400 s−1, and 500 s−1, for a total of 20 vials. Single decay rate behavior of fat and water was controlled by modulating the combination of iron microspheres and MnCl2 based on results obtained from the preliminary PDFF- phantom (see Results section below). Details (i.e., target PDFF/, chemical concentration) regarding this proposed PDFF-single phantom are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Composition of each vial within the proposed PDFF-single phantom.

| Set I: Target PDFF (%) and (s−1) | 5/100 | 5/200 | 5/300 | 5/400 | 5/500 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 1.03 | 5.82 | 15.39 | 24.96 | 34.53 |

| MnCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

| Set II: Target PDFF (%) and (s−1) | 10/100 | 10/200 | 10/300 | 10/400 | 10/500 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 1.03 | 5.82 | 15.39 | 24.96 | 34.53 |

| MnCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

| Set III: Target PDFF (%) and (s−1) | 20/100 | 20/200 | 20/300 | 20/400 | 20/500 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 1.03 | 5.82 | 15.39 | 24.96 | 34.53 |

| MnCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

| Set IV: Target PDFF (%) and (s−1) | 30/100 | 30/200 | 30/300 | 30/400 | 30/500 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 1.03 | 5.82 | 15.39 | 24.96 | 34.53 |

| MnCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.50 | 0.79 | 1.17 |

PDFF--T1 Phantom

This phantom was intended to demonstrate simultaneous control of PDFF, , and T1. Three sets of five vials were constructed by attempting to control one MRI biomarker (i.e., PDFF, or T1,water) per set. Set I was designed to modulate PDFF, with five vials of varying volume fat fractions. Iron microspheres concentration and NiCl2 concentration were fixed in this set of vials to obtain approximately constant and T1,water. Set II was designed with five vials with different values of controlled by adding varying iron microspheres concentrations. The calibration relationship between iron microspheres concentration and target was the same as mentioned above (no MnCl2 was added in order to maintain T1 within a physiologically relevant range). In this set, the volume fat fraction and NiCl2 concentration were held constant. Set III included five vials with varying NiCl2 concentration, with constant volume fat fraction and iron microsphere concentration. The calibration between NiCl2 concentration and target T1,water was formulated as: NiCl2 (mM) = 1.37/T1 (s)−0.63, which was obtained in a preliminary 3T calibration test within this study. Details (i.e., target PDFF//T1,water, chemical concentration) regarding this proposed PDFF--T1 phantom are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Composition of each vial within the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom.

| Set I: Target PDFF (%) | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 |

| NiCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Set II: Target (s−1) | 50 | 100 | 200 | 400 | 600 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 1.03 | 5.82 | 15.39 | 34.52 | 53.65 |

| NiCl2 concentration (mM) | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Set III: Target T1 (ms) | 500 | 750 | 1000 | 1250 | 1500 |

| Volume fat-fraction (%) | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Iron concentration (μg Fe/mL) | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 | 15.39 |

| NiCl2 concentration (mM) | 2.10 | 1.19 | 0.74 | 0.46 | 0.28 |

Materials and Construction

Materials

Fat source: Peanut oil (Planters, Glenview, IL) was chosen in this study to mimic liver triglycerides41 because it has a proton NMR spectrum similar to that of triglyceride protons in adipose tissue42.

modulators: Two different materials were used to modulate in this study. Paramagnetic salt (MnCl2, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and iron microspheres (UMC3001, COMPEL, Bangs Labs, Fishers, IN) with density: 1.23 g/mL, diameter: 2.9±0.14 μm. Iron microspheres were in the form of a saline suspension with 5% solids by weight, of which 12.5% is in the form of magnetite. Note that iron concentration in the proposed phantoms was described as iron weight (i.e., μg Fe) per volume of solution (i.e., mL). Importantly, these modulators also result in increased R2 relaxation rate, as also observed in the presence of liver iron38,39.

T1 modulator: The longitudinal relaxation rate T1 was modulated by NiCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Base water-agar solution components: The proposed phantoms were based on a 2% w/v agar (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) gel (i.e., agar mixed with DI water), including 43 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as surfactant, and 3 mM sodium benzoate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) as preservative.

Construction

A water-agar solution (including agar, sodium dodecyl sulfate, and sodium benzoate, as described above) was heated to above 194°F in order for the mixture to gel upon returning to room temperature. Appropriate volumes of this solution were dispensed by weight into a beaker according to the desired volume agar fraction. Then, appropriate volumes of MRI biomarker modulators (i.e., peanut oil, MnCl2, iron microspheres, and NiCl2) were dispensed by weight or by pipetting the appropriate volume into the beaker according to the desired volume fat fraction and desired biomarker modulator concentration.

After pouring into the beaker, the mixing of MRI biomarker modulators and water-agar solution was performed using a hand-held homogenizer (Model D1000, Dot Scientific, Burton, MI) for a duration of 30 seconds in order to obtain a homogeneous emulsion with smaller fat droplets. Immediately after homogenization, the mixture in the beaker was poured into high-density polyethylene (HDPE)43 vials (volume: 25 mL; diameter: 20 mm). The mixed materials in the vials were left overnight in order for the gel to form prior to subsequent imaging experiments.

The preliminary PDFF- phantom and the PDFF-single phantom were imaged by placing the vials in the MR coil surrounded with cushioning pads. Note these vials were scanned without an additional housing because of the large number of vials. The PDFF--T1 phantom vials were placed in a custom-designed spherical acrylic housing (Calimetrix, Madison, WI) that accommodates 15 vials. The housing was filled with a water bath to optimize the magnetic field homogeneity of the volume surrounding these vials and to facilitate optimal scanning conditions.

Data Acquisition

The preliminary PDFF- phantom was imaged using a clinical 3.0T MRI system (MR 750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with an 8-channel phased-array head coil. The other two phantoms (PDFF-single phantom and PDFF--T1 phantom) were imaged using a clinical 1.5T MRI system (MR HDxt, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) with an 8-channel phased-array head coil, and also the same clinical 3.0T MRI system mentioned above. Note all phantoms were stored in the scanner room for at least 1 hour before imaging, in order to stabilize the phantom temperature. Multiple stimulated echo acquisition mode (STEAM) MRS acquisitions44 were performed in order to measure , T1, and full width at half maximum (FWHM) of each major signal peak (i.e., main methylene fat peak and water peak) within each vial. Multi-echo CSE-MRI acquisitions were performed in order to obtain PDFF and maps, and subsequently measure these parameters within each vial. Detailed descriptions of these acquisitions are provided below.

Multi-TR-TE STEAM MRS

To sample the MR spectrum and measure T1,water and T1,fat, single voxel multi-TR-TE STEAM-MRS was acquired with multiple repetition times (TRs) and echo times (TEs). Acquisition parameters for both 1.5T and 3.0T included spectral width = 5000 Hz, 256 samples per spectrum, and 32 spectra acquired with varying TRs (min = 150 ms, max = 1500 ms), and varying TEs (min = 10 ms, max = 110 ms)44. A small MRS voxel with size = 8mm×8mm×8mm was carefully placed in the center of each vial within each phantom in order to minimize B0 field inhomogeneity effects and avoid potential artifacts due to chemical shift.

Multi-TE STEAM-MRS

To sample the MR spectrum and obtain spectroscopy-based R2,water, R2,fat, FWHMwater, and FWHMfat, single voxel multi-TE STEAM-MRS was acquired with multiple echo times44. This acquisition had spectral width of 5000 Hz and higher spectral resolution (2048 samples) than multi-TR-TE STEAM, in order to enable improved assessment of spectral properties (eg: FWHMwater, and FWHMfat). Acquisition parameters for the 1.5T MR system included five echoes with TE1 = 10.3 ms and 5 ms spacing, TR = 3500 ms, voxel size = 8×8×8mm3. Acquisition parameters for the 3.0T MR system included ten echoes with TE1 = 10.4 ms and 4 ms spacing, TR = 3500 ms, voxel size = 8×8×8mm3. As described above, the voxel was carefully placed in the center of each vial within each phantom.

Chemical Shift Encoded MRI

Multi-echo 3D spoiled gradient-echo (SGRE) data were acquired to perform quantitative confounder-corrected CSE-MRI-based PDFF and mapping45. Acquisition parameters included slice thickness = 2 mm, FOV = 24×16 cm2, Nx×Ny = 128×128, flip angle = 5° (1.5T)/4° (3.0T), TE1 = 1.1 ms, ΔTE = 1.1 ms (1.5T)/0.8 ms (3.0T), echo number = 12 (1.5T)/ 8 (3.0T), number of shots = 2, echo train length = 6 (1.5T)/4 (3.0T), number of signal averages = 4, bandwidth = ±83.3 kHz.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

Data Processing

Data from the STEAM acquisitions were processed offline using an automated custom script46 that jointly fits all the acquired spectra and simultaneously estimates T1,water, T1,fat, R2,water, R2,fat, FWHMfat, and FWHMwater (used to estimate from MRS as described below), among other parameters. In addition, spectra were plotted for illustration of fat and water peaks in the presence of different fat and iron concentrations. In order to estimate individual of water and fat, FWHM of water and fat peaks in the acquired spectra were obtained. Spectroscopy measured and were approximately estimated as =FWHMfat/water× π. Note that these FWHM-based estimates may be overestimated due to intravoxel dephasing (i.e., magnetic susceptibility-related B0 field inhomogeneity effect) in relatively large MRS voxels. However, the relative difference between and is a relevant performance metric, as water and fat signals reflect identical intravoxel dephasing. In addition, a multi-fat-peak model was applied to estimate FWHMfat with the assumption that the FWHM of all fat peaks are equal. Note that this model does not capture the full complexity of the fat signal spectrum (e.g., additional peaks, J-coupling), but magnetic susceptibility-related B0 inhomogeneity is likely the dominant effect introducing bias in the measured spectral linewidth. Nevertheless, the proposed is expected to be representative of the signal behavior observed by CSE-MRI. MRS processing was implemented in MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA).

Multi-echo CSE-MRI source echo data were obtained and fitted for PDFF and estimation. All the source SGRE acquisition data were processed offline using a magnitude-based algorithm30,45 that corrects for all relevant confounding factors (including decay42, spectral complexity of fat signals42, temperature effects47 and residual phase errors48,49) in the acquired echo data to obtain PDFF and maps. CSE-MRI reconstructions were also implemented using MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA). A circular region of interest (ROI) with area of approximately 1.5cm2 was placed in the center of each vial to measure the imaging PDFF value and imaging value from the PDFF map and map, respectively.

Statistical Analysis

For the proposed preliminary PDFF- phantom, the correlation between and was plotted for each set of vials (i.e., one set with MnCl2 and another set with iron microspheres as modulators).

For the remaining two phantoms, linear regression and Bland-Altman analysis were performed to assess several relationships: (1) Imaging PDFF/ versus target PDFF/ for each field strength, in order to demonstrate the accuracy of PDFF and quantification; (2) R2,water versus imaging across different field strengths, in order to monitor R2 decay rate compared with decay. In previous work38, R2 and both increased with increasing liver iron concentration, however R2 increases more slowly than . (3) versus , in order to validate single behavior for water and fat, for the proposed PDFF-single phantom at both 1.5T and 3.0T. Comparisons between the three different sets of vials regarding PDFF, , T1,water, and T1,fat, R2,water, and R2,fat for the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom were plotted at both 1.5T and 3.0T. In this study, all statistical analyses were implemented with MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) and Python.

Results

Preliminary PDFF- Phantom

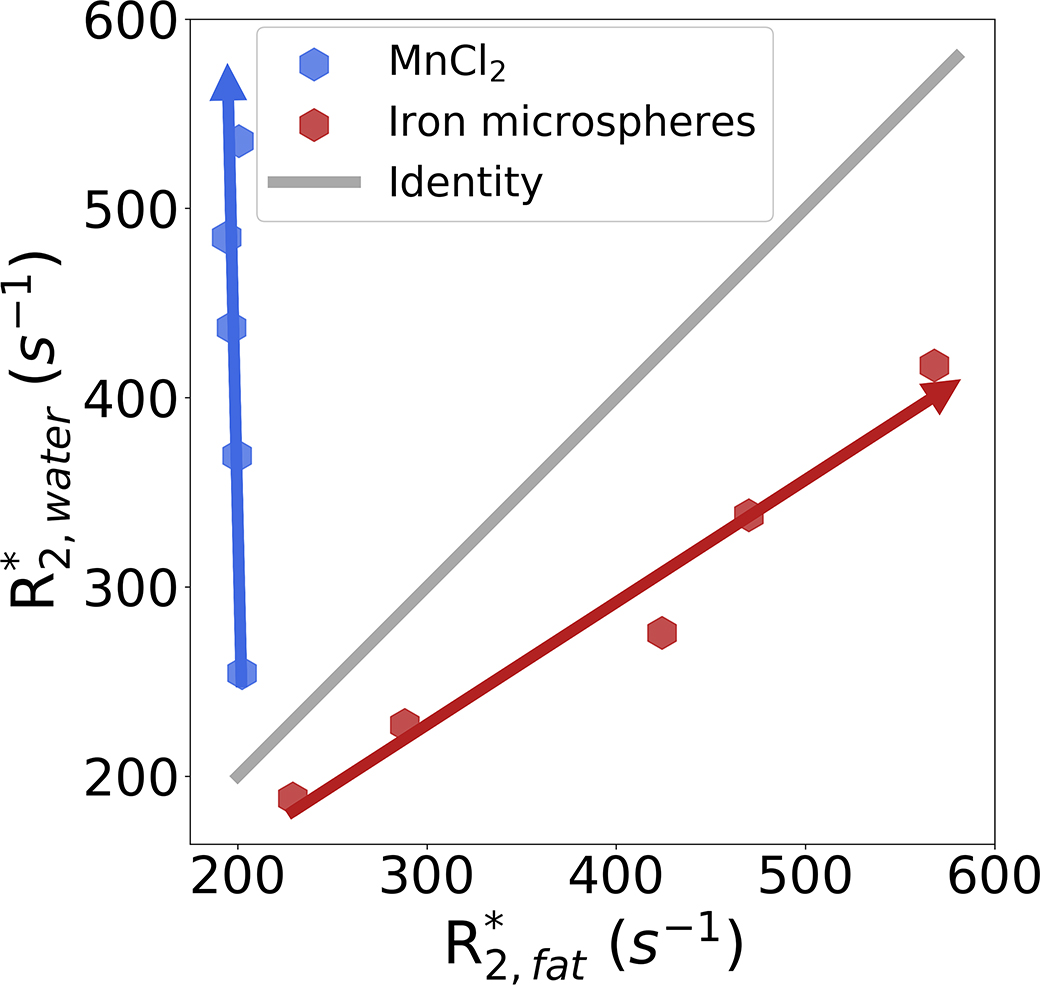

Figure 1 depicts the correlation between and for the two sets of vials with different modulators within the preliminary PDFF- phantom. For the set of vials using MnCl2 as the modulator, increasing MnCl2 concentration (indicated with a blue arrow) leads to increasing . The spectroscopy-based relaxivity for MnCl2 was calculated as: = 70.77 s−1/mM (3.0T). However, was unaffected by MnCl2 concentration. For the set of vials using iron microspheres as the modulator, and increased with increasing iron microsphere concentration (indicated with a red arrow), with relatively similar behavior for both water and fat. However, the spectroscopy-based relaxivity appears slightly higher for fat compared to water: = 5.94 s−1/μg Fe/mL, and = 8.99 s−1/μg Fe/mL (3.0T).

Figure 1.

Correlation between and for the two sets of vials within the preliminary PDFF- phantom. With increasing MnCl2 concentration, increases but remains unchanged. With increasing iron microspheres concentration, both and are increased. However, the relaxivities for water and fat are different. Note the arrowheads represent increasing concentration of MnCl2 and iron microspheres.

PDFF-single Phantom

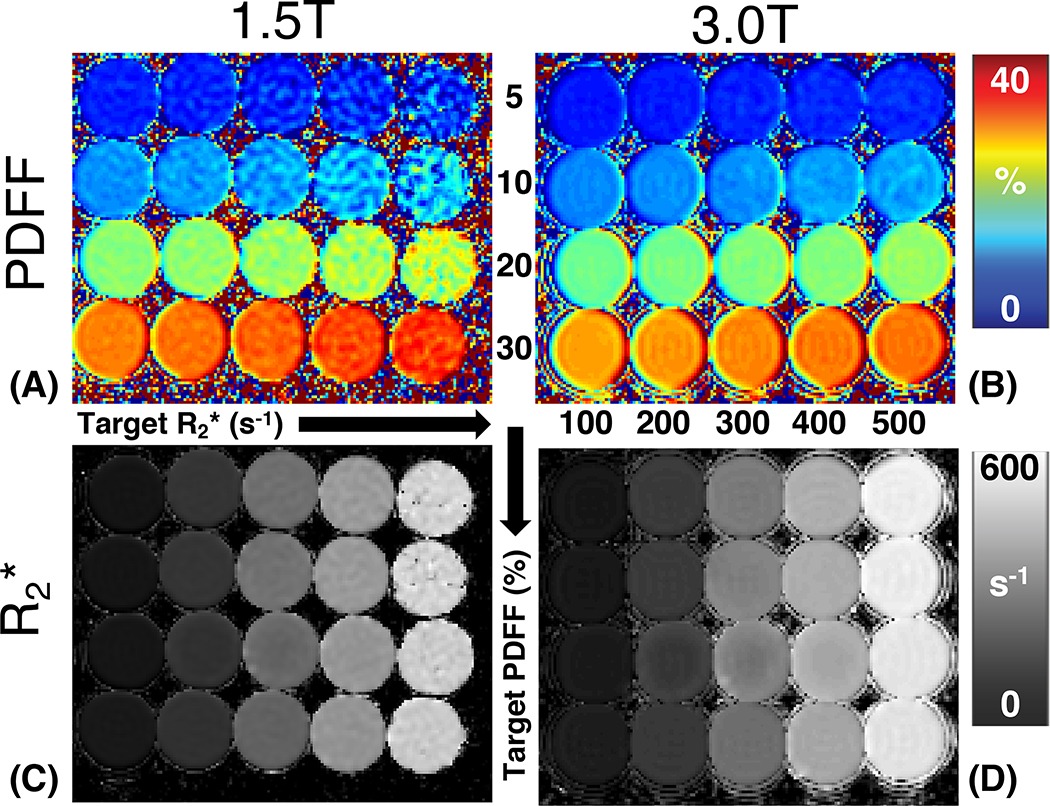

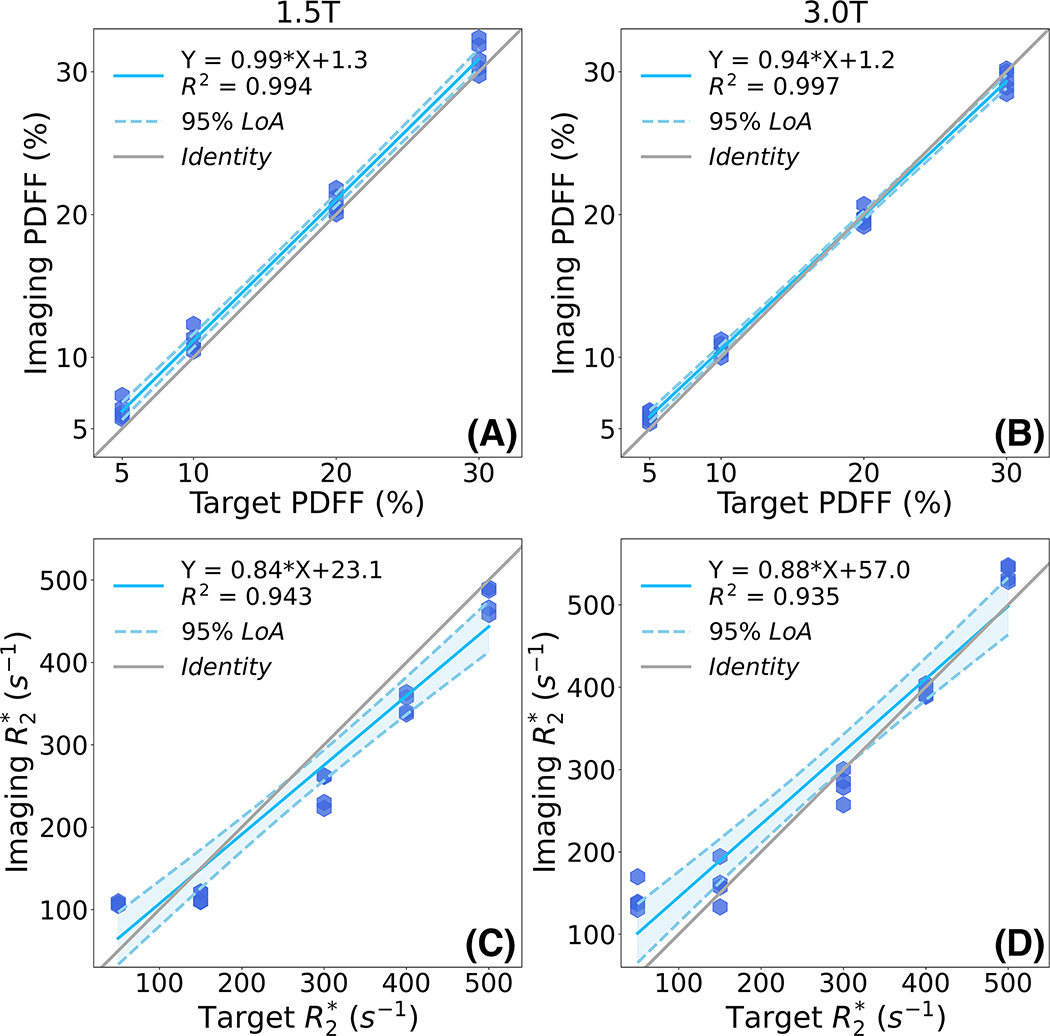

Figure 2 depicts representative PDFF and maps of the proposed PDFF-single phantom at 1.5T and 3.0T. Both the PDFF map and map show high image quality with homogeneous signal in each vial. PDFF remains approximately constant across varying iron and MnCl2 concentrations. remains approximately constant across varying volume fat fraction. Note the high noise observed in the 1.5T PDFF map within the high vials is likely due to severe noise propagation at 1.5T in the presence of high . In Figure 3, linear regression results (i.e., slope and intercept with standard deviation) are demonstrated regarding imaging-measured PDFF versus target PDFF and imaging-measured versus target at both 1.5T and 3.0T. Imaging PDFF shows high correlation with target PDFF at both 1.5T (slope = 0.99±0.04 × 10−1, intercept = 1.29±0.08, R2 = 0.994) and 3.0T (slope = 0.94±0.02 × 10−1, intercept = 1.15±0.05, R2 = 0.997). Similarly, imaging shows high correlation with target at both 1.5T (slope = 0.84±0.01, intercept = 23.10±3.52, R2 = 0.943) and 3.0T (slope = 0.88±0.01, intercept = 57.02±3.96, R2 = 0.935).

Figure 2.

Representative PDFF maps and maps of the proposed PDFF-single phantom at both 1.5T and 3.0T. Vials with varying iron and MnCl2 concentration (i.e., varying ) are arranged along the horizontal direction, and vials with varying volume fat fraction arranged along the vertical direction. At both field strengths, the PDFF map and map show high image quality, and homogeneous values within each vial.

Figure 3.

Linear regression plots demonstrate high correlation between imaging PDFF versus target PDFF (top row), as well as between imaging versus target (bottom row) at both 1.5T and 3.0T for the proposed PDFF-single phantom.

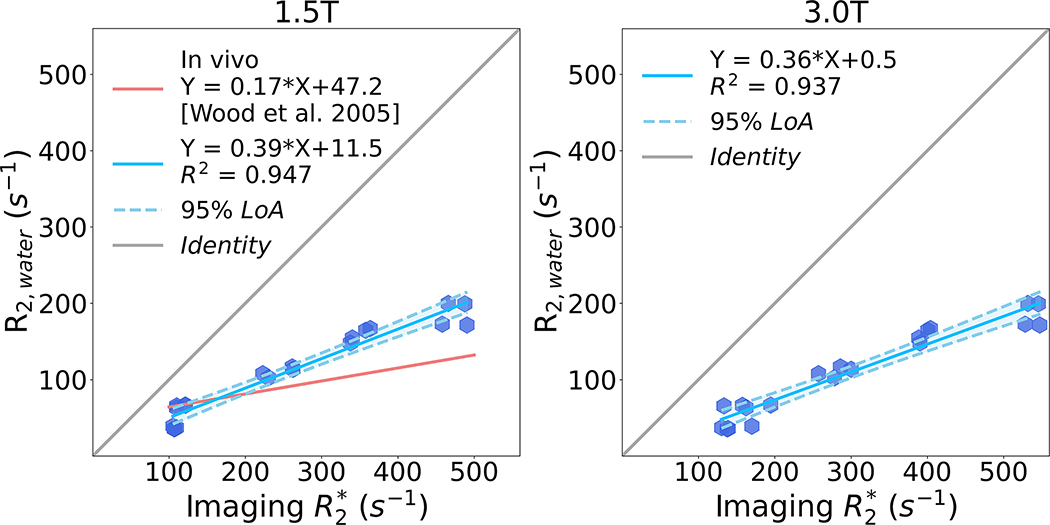

Linear regression analysis results (i.e., slope and intercept with standard deviation) comparing R2,water (measured using spectroscopy) and imaging at both 1.5T and 3.0T are shown in Figure 4. High correlation is observed between R2,water and imaging at both 1.5T and 3.0T. R2,water increases more slowly than with increasing iron and MnCl2 concentration. At 1.5T, the regression line has slope = 0.39 ± 0.04 × 10−1, intercept = 11.54 ± 1.41, and R2 = 0.947 compared with the in vivo relationship (slope = 0.17 and intercept = 47.2) from a previous study38. At 3.0T, the regression line has slope = 0.36±0.04×10−1, intercept = 0.54±1.69, and R2 = 0.937.

Figure 4.

Linear regression plots between R2,water and imaging at 1.5T and 3.0T for the proposed PDFF-single phantom. High correlation is observed between R2,water and imaging at both 1.5T and 3.0T. However, R2,water increases more slowly than with increasing iron and MnCl2 concentration, in qualitative agreement with the behavior observed in liver imaging in the presence of iron.

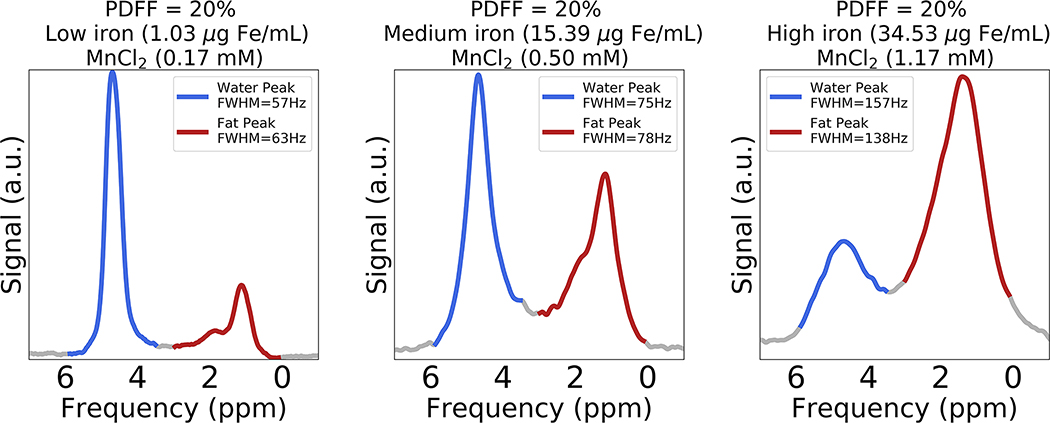

Figure 5 depicts representative spectra (TE = 10.3 ms) obtained from three vials with the same target PDFF (20%) but varying iron and MnCl2 concentration. In Figure 5 (left plot), both the water and fat peaks have moderate FWHM values (i.e., FWHMwater: 57 Hz, FWHMfat: 63 Hz) with low iron level (1.03 μg Fe/mL) and MnCl2 concentration (0.17 mM). In Figure 5 (middle plot), the FWHM values of water and fat peaks (i.e., FWHMwater: 75 Hz, FWHMfat: 78 Hz) increases with increasing iron level (15.39 μg Fe/mL) and MnCl2 concentration (0.50 mM) compared to the first vial. In Figure 5 (right plot), the FWHM values of water and fat peaks are broad (i.e., FWHMwater: 157 Hz, FWHMfat: 138 Hz) with high iron level (34.53 μg Fe/mL) and MnCl2 concentration (1.17 mM). Note that both the water and fat peaks demonstrate similar broadening with increasing iron level and MnCl2 concentration. The difference between the relative amplitude of water and fat peaks is due to the different R2 relaxation rates of water and fat (see below for R2,water and R2,fat measurements in the presence of iron).

Figure 5.

Spectra (TE = 10.3 ms) obtained from three vials with constant volume fat fraction (target PDFF = 20%) but increasing iron and MnCl2 concentrations. From left to right, the water and fat peaks become broader (i.e., increasing FWHM) simultaneously with increasing iron and MnCl2 concentration. FWHMfat was estimated using a multi-fat-peak model with an assumption that the FWHM of all fat peaks are equal. Note the difference between the relative amplitude of water and fat peaks is due to the different R2 relaxation rates of water and fat.

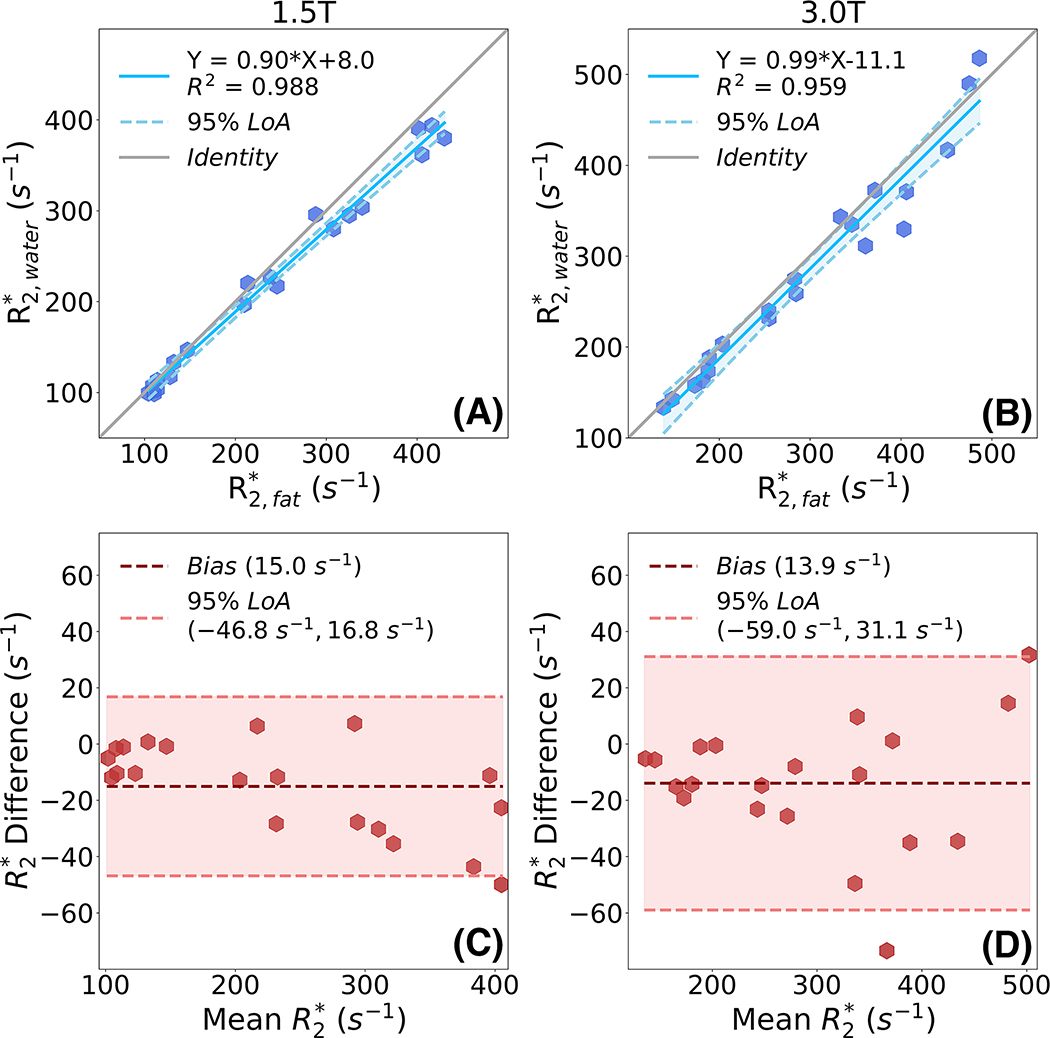

Linear regression analysis results comparing spectroscopy-measured versus at both 1.5T and 3.0T are shown in Figure 6. High correlation with slope close to 1 and intercept close to zero is observed between and at different field strengths. At 1.5T, the regression line has slope of 0.90±0.01 with intercept of 8.0±1.39 and R2 of 0.988. At 3.0T, the regression line has slope of 0.99±0.01 with intercept of 11.1±3.42 and R2 of 0.959. Bland-Altman analysis results comparing spectroscopy-measured versus at both 1.5T and 3.0T are shown in Figure 6 (bottom row). Importantly, the difference between water and fat is similar and small at both 1.5T (mean = 15.0 s−1, 95% LoA = [−46.8 s−1, 16.8 s−1]) and 3.0T (mean = 13.9 s−1, 95% LoA = [−59.0 s−1, 31.1 s−1]).

Figure 6.

High correlation and narrow limits of agreement are demonstrated by linear regression (top row) and Bland-Altman analysis (bottom row) between and at 1.5T and 3.0T for the proposed PDFF-single phantom. High correlation is observed between and at 1.5T (slope = 0.90, intercept = 7.98, R2 = 0.988) and 3.0T (slope = 0.99, intercept = −11.13, R2 = 0.959). Limits of agreement as assessed from Bland-Altman analysis were (−46.8 s−1,16.8 s−1) and (−59.0 s−1, 31.1 s−1) at 1.5T and 3.0T, respectively.

PDFF--T1 Phantom

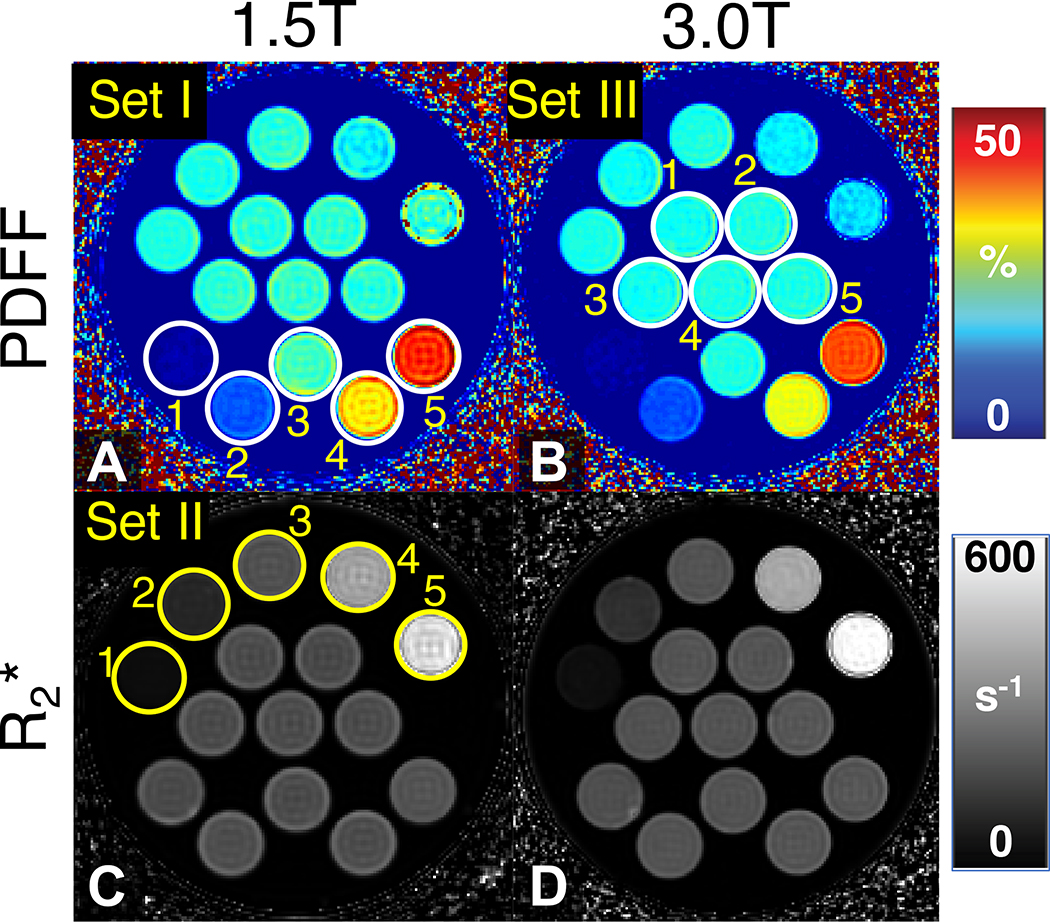

Figure 7 depicts representative PDFF maps and maps of the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom at 1.5T and 3.0T. Both the PDFF map and map show excellent image quality with homogeneous signal in each vial. Set I includes vials with varying volume fat-fraction but fixed iron and NiCl2 concentration. The five vials in Set I are labeled with white circles in the PDFF map at 1.5T. Accurate mapping of volume fat-fraction within each vial is demonstrated in the PDFF maps at both field strengths. Approximately constant is demonstrated in map at both field strengths. Set II contains vials with varying iron concentration but fixed volume fat fraction and NiCl2 concentration. The five vials in Set II are labeled with yellow circles in map at 1.5T. Varying is clearly depicted in the maps at both field strengths. Approximately constant volume fat fraction is demonstrated in the PDFF map at both field strengths across various values. Set III contains vials with varying NiCl2 concentration but fixed volume fat fraction and iron concentration. The five vials in Set III are labeled with white circles in the PDFF map at 3.0T. Approximately constant volume fat fraction is demonstrated in the PDFF map at both field strengths across various T1 values.

Figure 7.

Representative PDFF map and map of the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom at both 1.5T and 3.0T. Set I (labeled with white circles in the 1.5T PDFF map) includes five vials with varying target PDFF (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%, labeled as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively) with fixed iron and NiCl2 concentrations. Set II (labeled with yellow circles in the 1.5T map) includes five vials with varying iron concentration (i.e., varying target (50 s−1, 100 s−1, 200 s−1, 400 s−1, and 600 s−1, labeled as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively)) with fixed volume fat fraction and NiCl2 concentration. Set III (labeled with white circles at 3.0T PDFF map) includes five vials with varying NiCl2 concentration (i.e., varying target T1 (500 ms, 750 ms, 1000 ms, 1250 ms, and 1500 ms, labeled as 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively)) with fixed volume fat fraction and iron concentration.

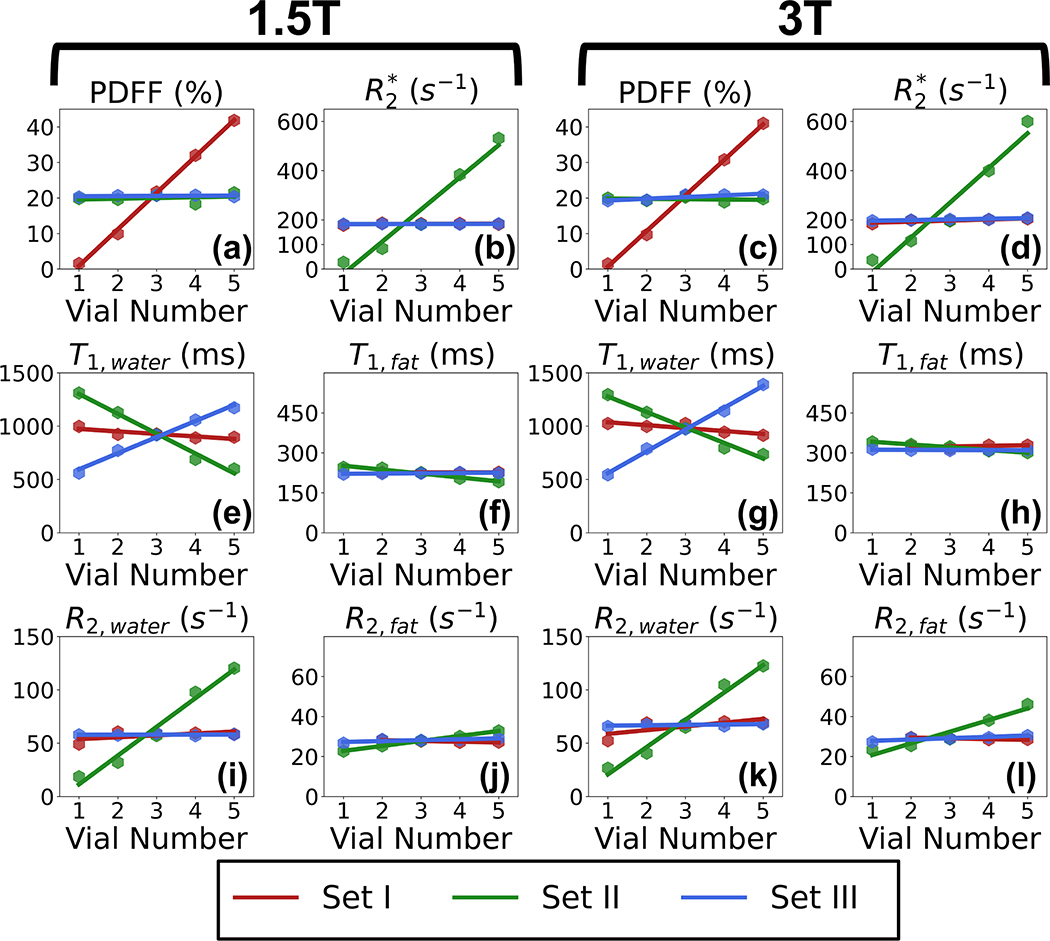

In Figure 8, the estimated imaging-based PDFF, imaging-based , spectroscopy-based T1,water, spectroscopy-based T1,fat, spectroscopy-based R2,water, and spectroscopy-based R2,fat are plotted for each vial within the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom, at both 1.5T and 3.0T. In each plot, vial number increases with increasing target PDFF, increasing iron concentration and decreasing NiCl2, for Set I, II, and III, respectively. In Figure 8 (a) and (c), the five vials from Set I show increasing measured PDFF (as expected) while the vials from Set II and Set III show nearly constant PDFF. In Figure 8 (b) and (d), the five vials from Set II show increasing as expected, while the of the vials from Set I and Set III remain approximately constant. In Figure 8 (e) and (g), T1,water of each vial is plotted for both 1.5T and 3.0T, respectively. The five vials of Set III show increasing T1,water as expected. The five vials of Set I have nearly constant T1,water of 1000 ms. However, T1,water decreases with increasing iron concentration in the vials from Set II, in qualitative agreement with the behavior observed in vivo26. In Figure 8 (f) and (h), all vials in the three Sets have nearly constant T1,fat of approximately 280 ms at 1.5T and 310 ms at 3.0T. Note that T1,fat is independent of iron concentration. In Figure 8 (i) and (k), R2,water of each vial is plotted for both 1.5T and 3.0T, respectively. The five vials of Set II have increasing R2,water, while Set I and Set III have nearly constant R2,water. In Figure 8 (j) and (l), R2,fat of each vial is plotted for both 1.5T and 3.0T, respectively. R2,fat remains nearly constant for all three sets at 1.5T. At 3.0T, R2,fat increases from 20 s−1 to 40 s−1 for the vials in Set II. R2,fat of the vials in Set I and Set III remains nearly constant under 3.0T.

Figure 8.

The proposed PDFF--T1 phantom enables simultaneous control of PDFF, , and T1 while mimicking in vivo signal behavior. The plots show measurements of imaging PDFF, imaging , T1,water, T1,fat, R2,water, and R2,fat of each vial from different sets (Set I: varying target PDFF (0%, 10%, 20%, 30%, and 40%) with fixed iron and NiCl2 concentration; Set II: varying target (50 s−1, 100 s−1, 200 s−1, 400 s−1, and 600 s−1) with fixed volume fat fraction and NiCl2 concentration; Set III: varying target T1 (500 ms, 750 ms, 1000 ms, 1250 ms, and 1500 ms) with fixed volume fat fraction and iron concentration at 1.5T and 3.0T. Vial number increases with increasing target PDFF, increasing iron concentration and decreasing NiCl2, for Set I, II, and III, respectively. The five vials in Set I show increasing PDFF with increasing volume fat fraction. The five vials in Set II show increasing and R2,water with increasing iron concentration. The five vials in Set III show increasing T1,water with decreasing NiCl2 concentration.

Discussion

In this work, we have proposed and validated novel quantitative MRI phantoms designed to mimic the simultaneous presence of fat, iron, and across a range of T1 values in the liver by controlling different MR biomarkers (i.e., PDFF, , and T1, respectively). Two different phantom designs were introduced in this study. The PDFF-single phantom aimed to control PDFF and simultaneously with highly accurate single- behavior of fat and water. The PDFF--T1 phantom enabled simultaneous control of PDFF, , and T1 within each vial. The proposed phantoms in this study may provide a useful tool for validation and quality assurance of MRI-based fat quantification, /R2 mapping, and T1 mapping methods.

The proposed phantoms are able to mimic previously observed in vivo signal behavior, most notably a common, “single” effective value for in the liver24,25. As demonstrated in this study, simple combinations of previous PDFF and phantom formulations (particularly using paramagnetic salts to control ) do not result in realistic signal behavior that mimics the simultaneous presence of fat and iron in the liver. However, the combined use of MnCl2 and iron microspheres as modulators in the proposed PDFF-single phantom leads to single- signal behavior that accurately mimics in vivo signals24,25. In addition, both the proposed PDFF-single phantom and PDFF--T1 phantom demonstrate that R2 increases more slowly than with increasing iron concentration. This behavior also agrees qualitatively with what has been observed in vivo38, although the quantitative relationship appears different (e.g., in vivo slope: r2/ = 0.18 compared to 0.39 observed in the proposed phantoms). This discrepancy may be due to differences in the magnetic susceptibility properties and microscopic iron distributions, as well as differences in the diffusion coefficient of water between the proposed phantoms and iron-loaded liver50. Furthermore, T1,water is shorter with increasing iron concentration in the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom, which qualitatively mimics the T1 behavior in the presence of iron deposition in the liver26,51.

A number of previously developed quantitative MR phantoms enable the control of individual MRI biomarkers (including PDFF, , and T1). Quantitative fat phantoms30,31 have been used in previous works to demonstrate accurate and reproducible fat quantification. The ability to modulate has been demonstrated in various phantoms32–34, and phantoms that control T1 have also been used in the past35,36. However, these previous works did not enable simultaneous modulation of PDFF, , and T1. In this study, the proposed PDFF--T1 phantom is able to modulate each of three important MR biomarkers (i.e., PDFF, , and T1,water) while controlling the other two.

Our study has several limitations. One assumption in our phantom construction procedure was that the small fat droplets will result after homogenization. No direct evidence proved this, even though our results demonstrated similar of fat and water, which was the primary goal. Microstructural assessment of the proposed phantom (e.g., using a light or electron microscopy, particle sizing, etc.) is beyond the scope of this study, due to the potential complexity of adequate sample preparation (e.g., with controlled cooling rate) in order to replicate the structure of the proposed phantoms for microstructural analysis. Future studies may be needed for definitive assessment of the relationship between microstructural properties (e.g., droplet size and distribution) and MRI biomarkers (e.g., PDFF and ).

Further, the range targeted in the proposed phantoms was limited in this study. The highest target is less than 1000 s−1 in both of the proposed phantoms. Phantoms with higher may be needed to validate techniques aimed at assessing high iron overload. However, robust quantification of PDFF, , and T1 in these phantoms may require non-Cartesian imaging techniques. Also, the lowest values in these vials were slightly above those of normal liver52. Nevertheless, the phantoms constructed in this study provided a relatively broad range of while maintaining enough SNR to enable stable measurement of PDFF, , R2, and T1. A wider range of combinations of PDFF, , and T1 than shown in this study is expected to be highly feasible with the proposed formulation. However, further evaluation with wider sets of parameters may be needed in future studies.

Another limitation of this study was that all the acquisitions were performed at room temperature (approximately 70 °F) without close temperature control, though temperature stabilization procedure was performed for each acquisition. This may introduce a small degree bias in PDFF measurements due to potential temperature variability between acquisitions, although such bias is very low with complex-based CSE-MRI47. Note that this work used a temperature-corrected fat quantification signal model under the assumption of a constant chemical shift between water and the main fat peak (3.5 ppm, as derived in previous work47), based on a temperature of 72°F. Furthermore, preliminary results indicate that the relaxation properties of the proposed phantoms may remain relatively stable near room temperature (e.g., between 68°F to 86°F). Importantly, excellent accuracy and high reproducibility were observed in this study without control for specific temperature across different acquisitions.

The spectroscopy-based relaxivity measurements for MnCl2 and iron might be biased (due to magnetic susceptibility related line broadening) and showed discrepancy with our imaging-based measurements in the absence of fat. However, spectroscopy acquisitions enable separate measurement of the linewidth of different chemical species and were therefore selected for this study. T1,water and T1,fat measurements in this work were performed using a multi-TR-TE STEAM MRS approach. This approach is sensitive to B1 field heterogeneities which may introduce errors in the T1 measurements. Nevertheless, the ability to reach a wide range of T1,water is clearly demonstrated in this work. Further, the measured T1,fat remains nearly constant, as expected, which suggests that the overall technique is adequate. The observed MRI parameter behavior ( relaxivity, r2 relaxivity, T1,water and T1,fat) is qualitatively consistent with that observed in liver at a given field strength. However, the field strength dependence of these parameters in the proposed phantom does not mimic the dependence observed in vivo (e.g., and T1 are nearly constant with field strength in the proposed phantoms, unlike in liver). Also, although a wide range of values can be achieved, the specific calibration between and iron concentration in the phantom does not mimic the calibrations observed in liver in the presence of iron overload. Further, the proposed phantoms are not designed to mimic other MRI-relevant properties of the liver, including magnetization transfer, stiffness, or diffusion.

In conclusion, we developed and validated a PDFF-single phantom that simultaneously mimics the co-existence of fat and iron in liver with similar decay rate for water and fat. Further, we were able to modulate PDFF, , and T1 in a PDFF--T1 phantom, in order to mimic the co-existence of fat, iron, and fibrosis. Further, this phantom was evaluated quantitatively at both 1.5T and 3.0T. The proposed phantoms may have applications for validation of novel MRI-based quantification techniques, for acceptance testing and quality assurance in multi-center clinical trials (e.g., for drug development) as well as for quality assurance in clinical applications.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by several NIH grants (R41-EB025729, R44-EB025729, R01-DK117354, R01-DK100651, K24-DK102595, R01-DK083380, and R01-DK088925). The authors acknowledge GE Healthcare who provides research support to the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Calimetrix for providing a custom-designed phantom housing. The authors also want to thank Rachel Krause from Calimetrix for her assistance with phantom construction. Finally, Dr. Reeder is a Romnes Faculty Fellow, and has received an award provided by the University of Wisconsin-Madison Office of the Vice Chancellor for Research and Graduate Education with funding from the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation.

Grant support:

R41-EB025729, R44-EB025729, R01-DK117354, R01-DK100651, K24-DK102595, R01-DK083380, and R01-DK088925

References

- 1.Ahmed A, Wong RJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Review: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(12):2062–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muñoz M, García-Erce JA, Remacha ÁF. Disorders of iron metabolism. Part II: iron deficiency and iron overload. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64(4):287–296. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2010.086991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brittenham GM. Iron-Chelating Therapy for Transfusional Iron Overload. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(2):146–156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct1004810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittenham GM, Badman DG. Noninvasive measurement of iron: report of an NIDDK workshop. Blood. 2003;101(1):15–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brittenham GM, Cohen AR, McLaren CE, et al. Hepatic iron stores and plasma ferritin concentration in patients with sickle cell anemia and thalassemia major. Am J Hematol. 1993;42(1):81–85. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830420116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeder SB, Sirlin C. Quantification of Liver Fat with Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2010;18(3):337–357. doi: 10.1016/j.mric.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson LJ, Holden S, Davis B, et al. Cardiovascular T2-star (T2*) magnetic resonance for the early diagnosis of myocardial iron overload. Eur Heart J. 2001;22(23):2171–2179. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haaf P, Garg P, Messroghli DR, Broadbent DA, Greenwood JP, Plein S. Cardiac T1 Mapping and Extracellular Volume (ECV) in clinical practice: a comprehensive review. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2016;18(1):89. doi: 10.1186/s12968-016-0308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muniyappa R, Noureldin R, Ouwerkerk R, et al. Myocardial Fat Accumulation Is Independent of Measures of Insulin Sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):3060–3068. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rijzewijk LJ, van der Meer RW, Smit JWA, et al. Myocardial steatosis is an independent predictor of diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(22):1793–1799. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins RL, Metzger GJ, et al. Myocardial triglycerides and systolic function in humans: In vivo evaluation by localized proton spectroscopy and cardiac imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):417–423. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smits MM, van Geenen EJM. The clinical significance of pancreatic steatosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8(3):169–177. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wood JC. Use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging to Monitor Iron Overload. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2014;28(4):747–764. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2014.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sáenz Medina J, Carballido Rodríguez J. A review of the pathophysiological factors involved in urological disease associated with metabolic syndrome. Actas Urol Esp Engl Ed. 2016;40(5):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.acuroe.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Targher G, Byrne CD. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an emerging driving force in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2017;13(5):297–310. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2017.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yokoo T, Clark HR, Pedrosa I, et al. Quantification of renal steatosis in type II diabetes mellitus using dixon-based MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44(5):1312–1319. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Heurtier A, et al. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):1898–1906. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rehm JL, Wolfgram PM, Hernando D, Eickhoff JC, Allen DB, Reeder SB. Proton density fat-fraction is an accurate biomarker of hepatic steatosis in adolescent girls and young women. Eur Radiol. 2015;25(10):2921–2930. doi: 10.1007/s00330-015-3724-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernando D, Levin YS, Sirlin CB, Reeder SB. Quantification of Liver Iron with MRI: State of the Art and Remaining Challenges. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2014;40(5):1003–1021. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoad CL, Palaniyappan N, Kaye P, et al. A study of T₁ relaxation time as a measure of liver fibrosis and the influence of confounding histological factors. NMR Biomed. 2015;28(6):706–714. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Banerjee R, Pavlides M, Tunnicliffe EM, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance for the non-invasive diagnosis of liver disease. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell EE, Ali A, Clouston AD, et al. Steatosis is a cofactor in liver injury in hemochromatosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(6):1937–1943. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hines CDG, Agni R, Roen C, et al. Validation of MRI Biomarkers of Hepatic Steatosis in the Presence of Iron Overload in the ob/ob Mouse. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(4):844–851. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horng DE, Hernando D, Hines CDG, Reeder SB. Comparison of R2* Correction Methods for Accurate Fat Quantification in Fatty Liver. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2013;37(2):414–422. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horng DE, Hernando D, Reeder SB. Quantification of liver fat in the presence of iron overload: Liver Fat in Iron Overload. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;45(2):428–439. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wood John C, Maya Otto-Duessel, Michelle Aguilar, et al. Cardiac Iron Determines Cardiac T2*, T2, and T1 in the Gerbil Model of Iron Cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112(4):535–543. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.504415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernando D, Kramer JH, Reeder SB. Multipeak Fat-Corrected Complex R2* Relaxometry: Theory, Optimization, and Clinical Validation. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(5):1319–1331. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karlsson M, Ekstedt M, Dahlström N, et al. Liver R2* is affected by both iron and fat: A dual biopsy-validated study of chronic liver disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;50(1):325–333. doi: 10.1002/jmri.26601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mozes FE, Tunnicliffe EM, Pavlides M, Robson MD. Influence of fat on liver T 1 measurements using modified Look–Locker inversion recovery (MOLLI) methods at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016;44(1):105–111. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernando D, Sharma SD, Aliyari Ghasabeh M, et al. Multisite, multivendor validation of the accuracy and reproducibility of proton-density fat-fraction quantification at 1.5T and 3T using a fat-water phantom: Proton-Density Fat-Fraction Quantification at 1.5T and 3T. Magn Reson Med. 2017;77(4):1516–1524. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernard CP, Liney GP, Manton DJ, Turnbull LW, Langton CM. Comparison of fat quantification methods: A phantom study at 3.0T. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27(1):192–197. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hines CDG, Yu H, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. T1 Independent, T2* Corrected MRI with Accurate Spectral Modeling for Quantification of Fat: Validation in a Fat-Water-SPIO Phantom. J Magn Reson Imaging JMRI. 2009;30(5):1215–1222. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharma SD, Hernando D, Yokoo T, et al. Development and Multi-Center Validation of a Novel Water-Fat-Iron Phantom for Joint Fat and Iron Quantification. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine Singapore, Singapore Published online 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mobini N, Malekzadeh M, Haghighatkhah H, Saligheh Rad H. A hybrid (iron–fat–water) phantom for liver iron overload quantification in the presence of contaminating fat using magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med. Published online November 16, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10334-019-00795-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haimerl M, Verloh N, Zeman F, et al. Assessment of Clinical Signs of Liver Cirrhosis Using T1 Mapping on Gd-EOB-DTPA-Enhanced 3T MRI. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085658 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christoffersson JO, Olsson LE, Sjöberg S. Nickel-doped agarose gel phantoms in MR imaging. Acta Radiol Stockh Swed 1987. 1991;32(5):426–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reeder SB, Hernando D, Sharma SD. Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation, assignee. Phantom for iron and fat quantification magnetic resonance imaging. United States patent US 10,036,796 Published online July 31, 2018.

- 38.Wood JC, Enriquez C, Ghugre N, et al. MRI R2 and R2* mapping accurately estimates hepatic iron concentration in transfusion-dependent thalassemia and sickle cell disease patients. Blood. 2005;106(4):1460–1465. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.St. Pierre TG, Clark PR, Chua-anusorn W, et al. Noninvasive measurement and imaging of liver iron concentrations using proton magnetic resonance. Blood. 2005;105(2):855–861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yokoo T, Serai SD, Pirasteh A, et al. Linearity, Bias, and Precision of Hepatic Proton Density Fat Fraction Measurements by Using MR Imaging: A Meta-Analysis. Radiology. 2018;286(2):486–498. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bydder M, Hamilton G, Middleton M, Sirlin C. MRI-based fat double bond mapping. Published online September 12, 2017 Accessed February 26, 2020 https://patents.google.com/patent/US9759794B2/en

- 42.Yu H, Shimakawa A, McKenzie CA, Brodsky E, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Multi-Echo Water-Fat Separation and Simultaneous R2* Estimation with Multi-Frequency Fat Spectrum Modeling. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1122–1134. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nemiroski A, Soh S, Kwok SW, Yu H-D, Whitesides GM. Tilted Magnetic Levitation Enables Measurement of the Complete Range of Densities of Materials with Low Magnetic Permeability. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(4):1252–1257. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b10936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hamilton G, Middleton MS, Hooker JC, et al. In vivo breath-hold 1H MRS simultaneous estimation of liver proton density fat fraction, and T1 and T2 of water and fat, with a multi-TR, multi-TE sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(6):1538–1543. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hernando D, Kellman P, Haldar JP, Liang Z-P. Robust Water/Fat Separation in the Presence of Large Field Inhomogeneities Using a Graph Cut Algorithm. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(1):79–90. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hernando D, Artz N, Hamilton G, Roldan A, Reeder SB. Fully Automated Processing of Multi-Echo Spectroscopy Data for Liver Fat Quantification. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Milan, Italy Published online 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hernando D, Sharma SD, Kramer H, Reeder SB. On the Confounding Effect of Temperature on Chemical Shift-Encoded Fat Quantification. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(2):464–470. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu H, Shimakawa A, Hines CDG, et al. Combination of Complex-Based and Magnitude-Based Multiecho Water-Fat Separation for Accurate Quantification of Fat-Fraction. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(1):199–206. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hernando D, Hines CDG, Yu H, Reeder SB. Addressing Phase Errors in Fat-Water Imaging Using a Mixed Magnitude/Complex Fitting Method. Magn Reson Med Off J Soc Magn Reson Med Soc Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):638–644. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ghugre NR, Wood JC. Relaxivity-iron calibration in hepatic iron overload: Probing underlying biophysical mechanisms using a Monte Carlo model. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65(3):837–847. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Henninger B, Kremser C, Rauch S, et al. Evaluation of MR imaging with T1 and T2* mapping for the determination of hepatic iron overload. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(11):2478–2486. doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2506-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schwenzer N, Machann J, Haap M, et al. T2* Relaxometry in Liver, Pancreas, and Spleen in a Healthy Cohort of One Hundred Twenty-Nine Subjects–Correlation With Age, Gender, and Serum Ferritin. Invest Radiol. 2008;43(12):854–860. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0b013e3181862413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nofiele JT, Cheng H-LM. Ultrashort Echo Time for Improved Positive-Contrast Manganese-Enhanced MRI of Cancer. Bathen TF, ed. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]