Abstract

Our previous studies have demonstrated that platelet-targeted FIX gene therapy can introduce sustained platelet-FIX expression in hemophilia B (FIXnull) mice. In this study, we aimed to enhance platelet-FIX expression in FIXnull mice with MGMT-mediated in vivo drug selection of transduced cells under a nonmyeloablative preconditioning. We constructed a novel lentiviral vector (2bF9/MGMT-LV), which harbors dual genes, the FIX gene driven by the αIIb promoter (2bF9) and the MGMT P140K gene under the murine stem cell virus promoter. Platelet-FIX expression in FIXnull mice was introduced by 2bF9/MGMT-mediated hematopoietic stem cell transduction and transplantation. The 2bF9/MGMT-transduced cells were effectively enriched after drug selection by O6-benzylguanine/1,3-bis-2-chloroethyl-1-nitrosourea. There was a 2.9-fold higher FIX antigen and a 3.7-fold higher FIX activity in platelets, respectively, post-treatment compared to pre-treatment. When a 6-hour tail bleeding test was used to grade the bleeding phenotype, the clotting time in treated animals was 2.6 ± 0.5 hours. In contrast, none of the FIXnull control mice were able to clot within 6 hours. Notably, none of the recipients developed anti-FIX antibodies after gene therapy. One of four recipients developed a low titer of inhibitors when challenged with rhF9 together with adjuvant. In contrast, all FIXnull controls developed inhibitors after the same challenge. Anti-FIX IgG were barely detectable in recipients (1.08 ± 0.54 μg/ml), an 875-fold lower level than in the FIXnull controls. Our data demonstrate that using the MGMT-mediated drug-selection system in 2bF9 gene therapy can significantly enhance therapeutic platelet-FIX expression, resulting in sustained phenotypic correction and immune tolerance in FIXnull mice.

Keywords: Hemophilia B, Gene therapy, platelet-targeted, Drug selection

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia B is an inherited bleeding disorder caused by a deficiency of factor IX (FIX). It occurs in 1 of 25,000 male worldwide. Current hemophilia management requires frequent intravenous protein replacement therapy of the deficient clotting FIX protein. This administration is inconvenient and costly, and around 5% of hemophilia B patients develop neutralizing antibodies to FIX, rendering FIX protein replacement therapy useless (Lillicrap, 2017; Peyvandi, Garagiola, & Young, 2016; Srivastava et al., 2013).

Gene therapy provides a great potential to treat and cure genetic bleeding disorders. Due to its monogenic nature, the small size of the FIX gene, and a broad therapeutic index, hemophilia B remains an ideal candidate for gene therapy. Indeed, gene therapy approaches for hemophilia B have been successful in recent clinical trials(Arruda, Doshi, & Samelson-Jones, 2017; George et al., 2017; Miesbach et al., 2018; Nathwani, Davidoff, & Tuddenham, 2017; Nathwani et al., 2014; Nathwani et al., 2011; Perrin, Herzog, & Markusic, 2019; Shomali et al., 2020; Weyand & Pipe, 2019). Among these, liver-directed adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated FIX gene therapy demonstrates encouraging results, in which therapeutic levels of FIX expression has persisted for more than 7 years during follow-up(Nathwani et al., 2014). However, the development of transient liver cell damage in 25% of recipients has been reported, which precludes the application of this strategy to patients with liver disease. Moreover, pre-existing immunity to the different AAV serotypes eliminates 30-50% of patients from these trials(Lillicrap, 2017; Makris, 2018; Perrin et al., 2019; Ramaswamy et al., 2018). In addition, although AAV is a non-integrating vector, trillions of vector particles delivered to these patients may result in the risk of vector integration into the host cell genome. Long-term safety of this strategy remains unknown(George, 2017; Pierce, Coffin, Members of the, & Organizing, 2019). Thus, the development of alternative gene therapy protocols using other vectors and targets is desired for the treatment of hemophilia B patients.

We have shown the significant advantages of lentivirus vector (LV)-mediated platelet-derived gene therapy for hemophilia A(Y. Chen et al., 2017; Kuether et al., 2012; Schroeder, Chen, Fang, Wilcox, & Shi, 2014; Shi et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007) and hemophilia B(Y. Chen, Schroeder, Kuether, Zhang, & Shi, 2014). Our previous studies have demonstrated that LV-mediated hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transduction and transplantation can introduce sustained levels of platelet-derived FIX (2bF9) expression in hemophilia B mice(Y. Chen et al., 2014). Although these results have been encouraging, challenges still remain. For example, the expression level of platelet-FIX activity in transduced recipients was only about 1 mU/108 platelets using a non-myeloablative conditioning regimen(Y. Chen et al., 2014). While increasing the multiplicity of infection is one option to enhance transduction efficiency and improve transgene expression levels, it may increase the potential risk of genotoxicities. The potential genotoxicities caused by integration site-mediated mutagenesis in HSCs are still under consideration in protocols based on a lentivirus-mediated HSC transduction and transplant approach(Montini et al., 2009; Pay et al., 2018; Persons, 2009). It has been shown that using a drug-selection system to enrich transduced cells could be an effective approach to enhance transgene expression and improve gene therapy efficacy (Falahati et al., 2012; Gajewski et al., 2005; Schroeder et al., 2014; D. Wang, Worsham, & Pan, 2008; H. Wang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2009; Zielske, Reese, Lingas, Donze, & Gerson, 2003). Introduction of a drug-resistance gene, O6-methylguanine-DNA-methyl-transferase (MGMT) P140K, in HSCs followed by in vivo chemoselection results in markedly increased donor chimerism, and accordingly enables reduction of the intensity and toxicity of the conditioning regimen(Falahati et al., 2012; H. Wang et al., 2019; Zielske et al., 2003).

Our previous study has shown that the incorporation of the MGMT-mediated drug selection system in our platelet-specific FVIII (2bF8) gene therapy strategy can efficiently enhance therapeutic platelet-derived FVIII expression, resulting in successful phenotypic correction and FVIII-specific immune tolerance induction in hemophilia A mice(Schroeder et al., 2014). Here, we hypothesize that incorporating the MGMT gene into the 2bF9 lentiviral vector will allow for post-transduction selection of 2bF9-transduced hematopoietic cells, which will lead to enhanced efficacy of platelet-FIX gene therapy for hemophilia B.

In this study, we tested the MGMT-mediated selection strategy for platelet-targeted FIX gene therapy of hemophilia B. We demonstrate that MGMT-modified repopulating hematopoietic cells were dramatically enriched and platelet FIX expression was markedly enhanced after drug-selection in our FIXnull murine model even under a nonmyeloablative regimen. Moreover, we demonstrate that FIX immune tolerance was induced by the novel gene therapy strategy in this study.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. ∣Mice

FIXnull mice, a kind gift from Paul Monahan(Monahan et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2017) (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gene Therapy Center, NC), used in this study were on a C57BL/6 background and maintained in our facility. All animal work was performed according to the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Medical College of Wisconsin. Both male and female animals were used in our studies. Isoflurane or ketamine was used for anesthesia.

2.2 ∣. Vector construction, virus production

The FIX expression cassette (2.8 kb) was removed from the pWPT-2bF9 vector(Y. Chen et al., 2014) and replaced the FVIII expression cassette in the pWPT-2bF8/MGMT vector(Schroeder et al., 2014), resulting in a new lentiviral construct, pWPT-2bF9/MGMT. The 2bF9/MGMT lentivirus (2bF9/MGMT LV) was produced using the protocol as previously described(Y. Chen et al., 2014; Schroeder et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007).

2.3 ∣. Cell transduction and drug treatment in vitro

Dami cells (a promegakaryocyte cell line)(Greenberg, Rosenthal, Greeley, Tantravahi, & Handin, 1988) were transduced with 2bF9/MGMT LV or 2bF9 LV on RetroNectin (Takara Bio, Madison, WI, USA) coated plate using our virus titering protocol as previously reported(Luo et al., 2018). Briefly, cells were seeded at a cell dose of 1.5 × 105 per well of a 24-well, non-tissue culture-treated plate (Falcon-Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) coated with RetroNectin and transduced with lentivirus at a concentration of 1:50 (vol:vol) in 250 μl of X-VIVO 10 media (BioWhittaker, Rockland, ME, USA) plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA). Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. Additional media was added 48 hours after transduction. 2bF8/MGMT-LV and 2bF8-LV were used as control vectors in parallel.

Four days after transduction, genomic DNA was purified from sample cell pellets and 2bF9 transgenic expression was analyzed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Remaining cells were transferred to 6-well tissue culture plate and cultured for another 14 days in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (IMDM) (Gibco) with 10% horse serum (Gibco) to expand cell number for downstream studies. Supernatants were harvested for FIX assay to confirm protein expression during culture.

After confirming the successful transduction, one million Dami cells in each group were treated with 25 μM O6-benzylguanine (BG) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 hour followed by 250 μM 1,3-bis-2-chloroethyl-1-nitrosourea (BCNU) (Emcure Pharmaceuticals, Pune, India) in completed IMDM media for 2 hours at 37°C. After washing them with Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) (Corning Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA), cells were plated onto a 6-well plate in 2 ml completed IMDM media per well and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2. One milliliter of media together with cells was removed from each well for assays and an equal amount of fresh media was replenished at various time points during the study course. Cell number and FIX:Ag expression in the supernatant after plating were monitored by trypan blue staining and ELISA, respectively.

2.4 ∣. HSC transduction and transplantation

HSC transduction and transplantation were performed following procedures described in our previous reports(Y. Chen et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007). Briefly, Sca-1+ cells were isolated from donor FIXnull mice using the EasySep™ Mouse SCA1 Positive Selection Kit (STEMCELL™ Technologies, Cambridge, MA, USA) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The transduction of Sca-1+ cells with 2bF9/MGMT LV was performed following procedures as described in our previous reports(Y. Chen et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007). Two million 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced Sca-1+ cells were transplanted into each FIXnull mouse preconditioned with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen, 660 cGy total body irradiation (TBI). After bone marrow transplantation (BMT) and at least 4 weeks of bone marrow reconstitution, blood samples were collected from recipients for assays.

2.5 ∣. PCR and qPCR

Genomic DNA was purified from peripheral blood leukocytes using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The 2bF9 transgene expression was determined by PCR and quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) analyses as described in our previous reports(Y. Chen et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007).

2.6 ∣. In vivo selection of transduced cells

Beginning at 8 weeks after transplantation, animals were treated with BG followed by BCNU as described in our previous report(Schroeder et al., 2014). Briefly, BG was administered intravenously at a dose of 30 mg/kg body weight. BCNU was given intravenously 1 hour after BG administration at a dose of 5 mg/kg. Animals were treated once every 4 weeks for a total of 3 treatments.

2.7 ∣. FIX expression assays

FIX expression levels in supernatants of transfected Dami cells, mouse platelets, and plasma were monitored to evaluate drug selection efficacy. FIX expression was quantitated by FIX antigen (FIX:Ag) and functional FIX activity (FIX:C) assays. These assays were performed following the procedures as we previously described(Y. Chen et al., 2014). Human reference plasma was used as the standard for the FIX assays.

2.8 ∣. Mouse blood count

During the study course, blood samples were collected from BMT recipients and naïve FIXnull mice using sodium citrate as an anticoagulant following the procedure described in our previous report(Shi et al., 2008). Leukocytes, hemoglobin (Hb), and platelets were measured by the ABC Hematology Analyzer (Scil Animal Care Company, Gurnee, IL, USA).

2.9 ∣. Phenotypic correction assessment

The six-hour tail bleeding test as reported(Y. Chen et al., 2014). was used to grade the phenotypic correction of 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients at 6 weeks after the final BG/BCNU treatment. In brief, tail tips were clipped using a 1.6 mm diameter template. One milliliter of 0.9% NaCl was administered by subcutaneous injection over the interscapular area when the test started, and an additional 0.4 ml was administered at 4 hours after the test started. Animals were checked hourly for 6 hours and clotting time was recorded. Fifty microliters of blood were collected 3 days before the test and 6 hours after tail tips were transected, and Hb level was measured using the the ABC Hematology Analyzer. The Hb was normalized by defining the pretest levels of Hb as 100%. FIXnull and wild-type (WT) mice were used as parallel controls.

2.10 ∣. Immune response studies

At 16 weeks after the final BG/BCNU treatment, animals were immunized with recombinant human FIX (rhF9) (BeneFIX, Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Cambridge, MA, USA) at a dose of 200 U/kg in the presence of incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (IFA) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) by intraperitoneal injection twice with a 3-week interval. Two weeks after the second immunization, blood samples were collected, and plasmas were isolated. Anti-FIX inhibitor titers were determined by a modified Bethesda assay as described in our previous report(Y. Chen et al., 2014). The titers of total anti-FIX IgG antibodies were determined by ELISA following the procedures reported previously(Y. Chen et al., 2014). The sensitivity of the ELISA assay was 0.03 μg/ml.

2.11 ∣. Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons of two groups were evaluated by either paired, unpaired two-tailed student t-test, or Mann-Whitney U-test. Statistical analysis was performed using SigmaPlot 12.5 software (Systat Software, Inc. San Jose, CA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). A value of P < 0.05 was considered as statistical significance.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Efficient in vitro drug-selection of Dami cells transduced with 2bF9/MGMT

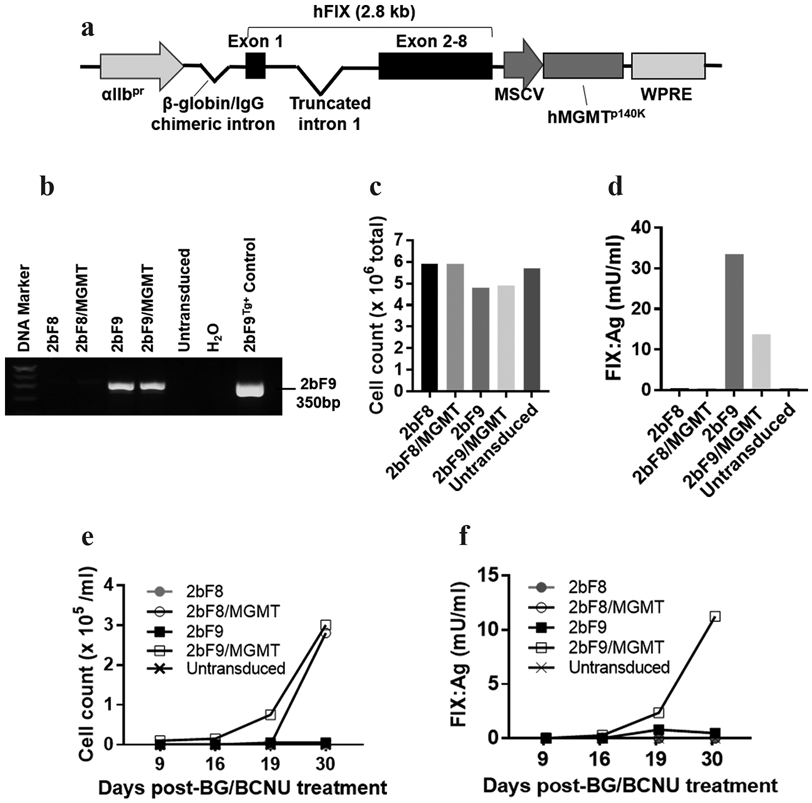

We developed a novel lentiviral construct, pWPT-2bF9/MGMT, which encodes both the 2bF9 gene and a drug-resistance gene, the MGMT P140K cassette (Figure 1a). To evaluate the feasibility of selection of the transduced cells and enhancement of neoprotein FIX expression using the 2bF9/MGMT vector, we first performed in vitro studies via transduction of Dami cells with 2bF9/MGMT LV. After transduction, the 2bF9 transgene expression cassette was detected in both the 2bF9 and 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced groups by PCR (Figure 1b). After in vitro cultured for 18 days, similar cell numbers were obtained from groups with and without MGMT (Figure 1c). FIX:Ag expression level was 33.6 mU/ml in the supernant of Dami cells transduced with 2bF9 LV, which was 2.5-fold higher than in the condition of 2bF9/MGMT LV (13.7 mU/ml) (Figure 1d).

FIGURE 1.

In vitro validation of the 2bF9/MGMT system via transduction of Dami cells. (a) Diagram of the pWPT-2bF9/MGMT construct. FIX is driven by the platelet-specific αIIb promoter. MGMT P140K is driven by the murine stem cell virus promoter (MSCV) promoter. (b) Dami cells were transduced with 2bF9, 2bF9/MGMT, or a control vector (2bF8 or 2bF8/MGMT). Cells were cultured for 18 days after transduction. Cells were sampled and genomic DNA was purified. 2bF9 transgene expression was analyzed by PCR. A 350 bp fragment from the 2bF9 expression cassette was amplified. Genomic DNA from a 2bF9 transgenic (2bF9Tg+) mouse was used as a positive control. DNA from untransduced Dami cells was used as a negative control. (c) Total cell number in each condition after 18 days of cell culture. Cell numbers were counted by trypan blue staining. (d) FIX antigen (FIX:Ag) expression in supernatants of Dami cells that were transduced with 2bF9 or 2bF9/MGMT lentivirus. FIX:Ag expression levels were determined by ELISA. Human reference plasma was used as the standard. (e, f) Transduced Dami cells (1×106 from each condition) were treated with BG for 1 hour and then BCNU for 2 hours. Cells were plated on a 6-well plate. Cell count and FIX:Ag expression were monitored after the treatment. The cell proliferation was measured by trypan blue staining (e). FIX:Ag expression in the supernatant was determined by ELISA (f).

Of note, after BG/BCNU treatment, cells in the vehicle control and untransduced groups were largely killed. However, Dami cells transduced with 2bF9/MGMT LV or 2bF8/MGMT LV survived beyond the BG/BCNU selection. Cell expansion was observed starting at around 2 weeks after the treatment and cell number rapidly increased in the 2bF8/MGMT LV- and 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced groups (Figure 1e). Meanwhile, FIX:Ag expression levels markedly increased in the supernatant of Dami cells transduced with 2bF9/MGMT LV, but not in the condition with 2bF9 LV (Figure 1f), indicating that 2bF9/MGMT-genetically manipulated promegakaryocytes, Dami cells, were selected via BG/BCNU treatment in vitro. These data demonstrate that it is feasible to select 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced cells using BG/BCNU drug selection system.

3.2 ∣. Introduction of the selectable 2bF9 transgene into HSCs of FIXnull mice

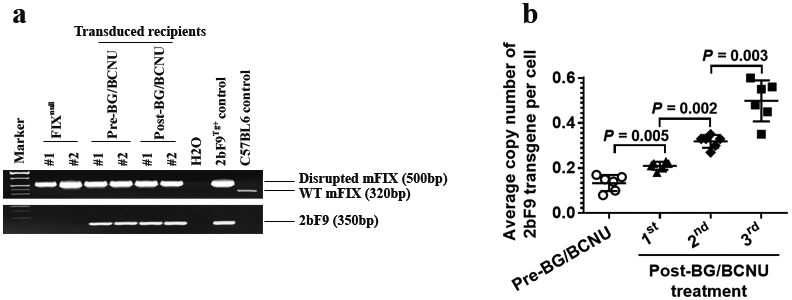

The 2bF9/MGMT expression cassette was introduced into FIXnull HSCs by transduction and transplantation under a nonmyeloablative conditioning of 660 cGy TBI. The 2bF9 expression cassette was detected by semi-quantitative PCR in all recipients that received 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced HSCs. Representative PCR results are shown in Figure 2a. The average copy number of 2bF9/MGMT proviral DNA per cell in recipients was quantitated by qPCR. The results confirm that 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced cells were effectively enriched after each round of BG/BCNU selective treatment in vivo. The average copy number of the 2bF9 expression cassette per cell significantly increased after each treatment. After three BG/BCNU treatments, the average copy number was 0.50 ± 0.04, which was 3.8-fold higher than pre-BG/BCNU treatment (0.13 ± 0.01) (Figure 2b). These results demonstrate that the engraftment of 2bF9/MGMT genetically-modified HSCs are viable in FIXnull mice under a clinically relevant nonmyeloablative preconditioning and that 2bF9/MGMT-transduced hematopoietic cells are selectable by BG/BCNU treatment in vivo.

FIGURE 2.

Genetic analysis of 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced HSC transplantation recipients. Peripheral blood from recipients was collected during the study course. Genomic DNA was purified from the peripheral blood cells. (a) Analysis of the 2bF9 transgene expression by PCR. A 350 bp fragment from the 2bF9 expression cassette was amplified. Genomic DNA from 2bF9 transgenic and FIXnull mice were used as controls. (b) The average copy number of the 2bF9 transgene per cell in transduced recipients was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. DNA was analyzed for the 2bF9 transgene with normalization to the ApoB gene. Data shown were summarized from 6 recipients and expressed as the mean ± SD. The paired t-test was used for comparison of two groups.

3.3 ∣. Enhancing platelet-derived FIX expression via MGMT-mediated in vivo selection in FIXnull mice

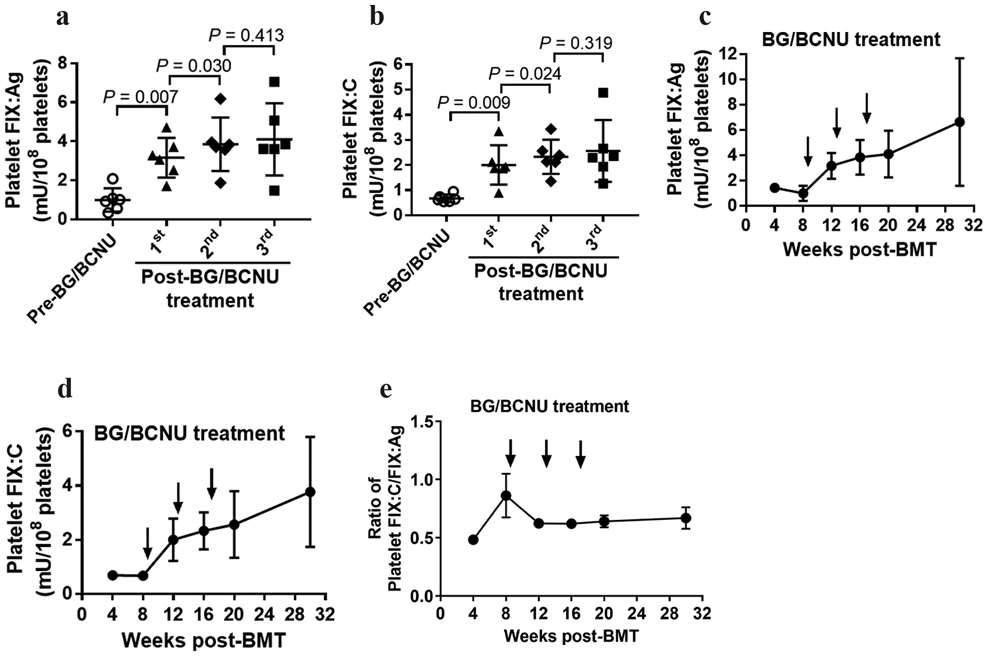

To evaluate the feasibility of the MGMT-mediated drug-selection system in platelet gene therapy of hemophilia B, we quantified the FIX expression in FIXnull mice that received 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced HSCs. FIX:Ag and FIX:C expression levels in platelet lysates were determined by ELISA and chromogenic assay, respectively. There was an approximately 2.9-fold increased FIX:Ag post-treatment compared to pre-treatment (4.11 ± 0.76 mU per 108 platelets vs. 1.43 ± 0.06 mU per 108 platelets, respectively) (Figure 3a). Platelet FIX:C in recipients was only 0.69 ± 0.04 mU per 108 platelets before treatment, which significantly increased to 2.56 ± 0.50 mU per 108 platelets after three BG/BCNU drug-selective treatments (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Platelet-FIX expression in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull recipients. Platelet-FIX expression in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients was monitored for 30 weeks. Platelets were isolated from peripheral blood and lysed in 0.5% CHAPS. The levels of FIX:Ag in platelet lysates were determined by ELISA and levels of FIX:C were determined by chromogenic assay. Platelets from FIXnull mice were used as a negative control. Data shown were summarized from 6 recipients and expressed as the mean ± SD. The paired t-test was used for comparison of two groups. (a) Expression levels of platelet-FIX:Ag from individual animals at time points of pre- and post-BG/BCNU treatment. (b) Expression levels of platelet-FIX:C from individual animals at time points of pre- and post-BG/BCNU treatment. (c) Average expression level of platelet-FIX:Ag over the study period. (d) Average expression level of platelet-FIX:C over the study period. (e) Average ratio of platelet-FIX:C to FIX:Ag over the study period.

The average activity level of FIX before BG/BCNU treatment was 0.67 ± 0.15 mU per 108 platelets, increasing to 3.77 ± 2.03 mU per 108 platelets after in vivo enrichment, whereas the average antigen levels of FIX increased from 1.00 ± 0.60 to 6.63 ± 5.05 mU per 108 platelets during the study period. The average levels of platelet FIX:Ag appear to be higher than those of FIX:C obtained from each time point in recipients (Figure 3c,d). The ratio of platelet FIX:C to FIX:Ag was at its lowest level of about 0.48 ± 0.08 at 4 weeks and increased with a peak of around 0.86 ± 0.46 at 8 weeks. The ratio decreased to 0.62 ± 0.09 at 12 weeks after the 2nd BG/BCNU treatment and remained stable over time at 12–30 weeks during the study course (Figure 3e).

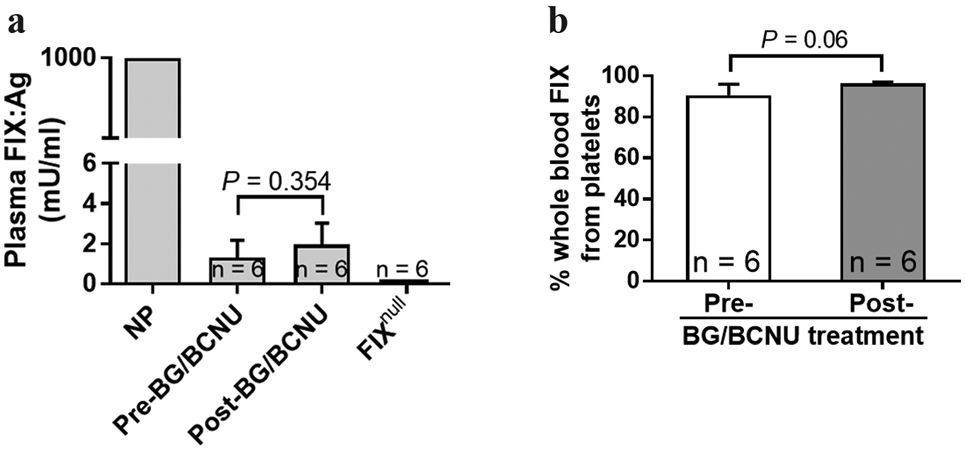

A small amount of FIX:Ag was detected in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipient plasma with average levels of 1.32 ± 0.87 mU per ml before treatment and 1.97 ± 1.06 mU per ml after three treatments (Figure 4a), respectively. When we normalized FIX:Ag levels to total whole blood FIX content, the results demonstrated that 96.32 ± 0.32% of whole blood FIX in BG/BCNU-treated animals was stored in platelets (Figure 4b).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis of FIX:Ag expression in plasma of 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients. (a) FIX expression levels in mouse plasma as measured by a human FIX-specific ELISA assay. Normal pool of human plasma was employed as the standard. Plasma from FIXnull mice was used as a negative control. (b) The distribution of the FIX transgene product in recipient whole blood. To analyze the distribution of FIX between platelets and plasma, we normalized FIX levels to total whole-blood FIX content in individual mice. Animals were analyzed at pre- and post-three rounds of BG/BCNU treatment. Data were presented as mean ± SD. The unpaired student t-test was used for the comparison of two groups.

These results demonstrate that using the MGMT-mediated in vivo drug-selection system can effectively enrich 2bF9/MGMT-transduced cells and thereby enhance platelet-FIX expression in FIXnull mice after gene therapy under a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen.

3.4 ∣. Phenotypic correction of the coagulation defect in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull recipients after BG/BCNU treatment

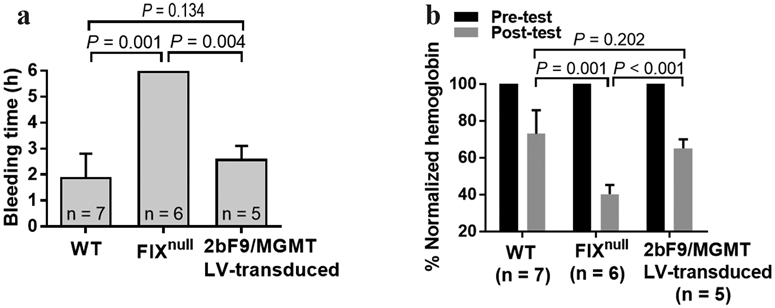

To grade phenotypic correction of the coagulation defect in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull recipients, a 6-hour tail bleeding test was used. All transduced recipients stopped bleeding within 6 hours with a clotting time of 2.6 ± 0.5 hours and a remaining Hb level of 65.1 ± 4.9%, which were not significantly different from those of the wild-type (WT) control group (1.7 ± 0.9 hours and 70.6 ± 13.9%). In contrast, none of the FIXnull control mice stopped bleeding within 6 hours with a remaining Hb level of 38.8 ± 6.7% (Figure 5), which were significantly different compared to those obtained from the 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients and the WT controls. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the hemophilic phenotype was rescued in FIXnull mice animals after receiving 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced HSCs followed by BG/BCNU treatment.

FIGURE 5.

Phenotypic correction of the coagulation defect in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull recipients after BG/BCNU treatment. (a) Tail-clipping bleeding test. Tail tips were clipped using a 1.6-mm diameter template. Blood clotting time was recorded. (b) Hemoglobin levels were measured before and 6 hours after tail clipping. The hemoglobin level of each animal before the test was defined as 100%. WT and FIXnull mice were used as parallel controls. The unpaired student t-test was used for the comparison of two groups.

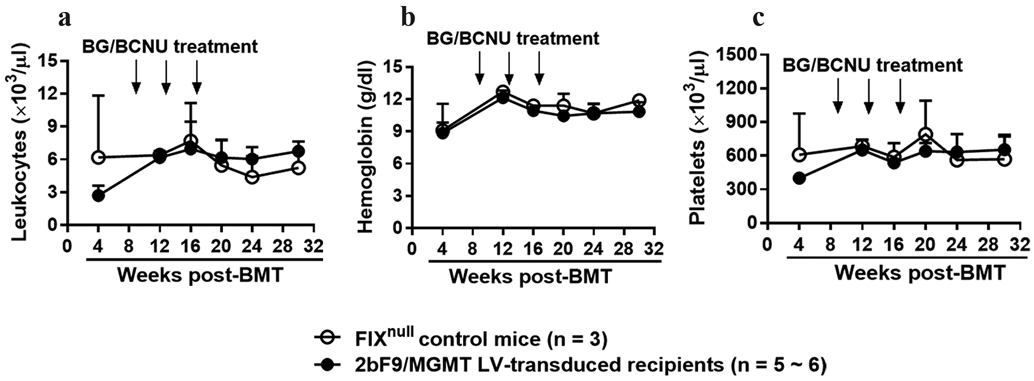

3.5 ∣. No overt hematological toxicity in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull mice after the last BG/BCNU treatment

Mouse blood counts were monitored during the study course. Leukocytes, Hb, and platelets from the peripheral blood in transduced recipients and FIXnull control mice were measured using an automatic animal blood counter. No significant effects on cell counts in peripheral blood were found in the 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients after the last BG/BCNU treatment when compared with those in the FIXnull parallel control mice (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Mouse blood count was monitored during the study course. Peripheral leukocytes (a) hemoglobin (b) and platelets (c) from transduced recipients and FIXnull control mice were measured by using an automatic animal blood counter during study course.

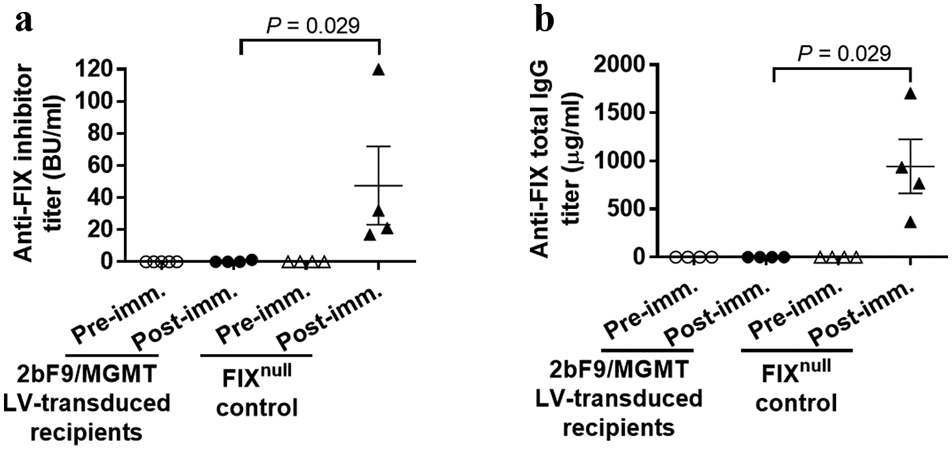

3.6 ∣. Immune tolerance development in BG/BCNU-treated 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced FIXnull recipients

To explore the immune response after 2bF9/MGMT gene therapy in FIXnull mice, anti-FIX inhibitor titers and anti-FIX total IgG levels in transduced recipient plasmas were measured by Bethesda assay and ELISA, respectively. None of the recipients developed anti-FIX inhibitors as measured by Bethesda assay after 2bF9/MGMT gene therapy followed by BG/BCNU in vivo drug-selection. When animals were challenged with rhF9 in the presence of IFA, one out of four recipients developed a low titer of inhibitors (1.3 BU per ml). In contrast, all of the FIXnull control mice developed inhibitors ranging from 17–120 BU per ml after the same challenge (Figure 7a).

FIGURE 7.

Immune tolerance development in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients. Plasma samples were collected from transduced recipients before and after rhF9 plus incomplete Freund’s adjuvant challenge. (a) Anti-FIX inhibitory antibodies in mouse plasma were measured by Bethesda assay. (b) Total anti-FIX IgG in mouse plasma were determined by ELISA. Plasma from FIXnull naïve mice was used as a control in parallel. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for the comparison of two groups.

When total anti-FIX IgG levels were measured by ELISA before and after immunization, the amounts of total anti-FIX IgG were barely detectable in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients (1.08 ± 0.54 μg per ml, ranging from 0.09 to 2.36 μg per ml). In contrast, FIXnull control mice produced an 875-fold higher level of anti-FIX antibodies with an average of 945.00 ± 280.30 μg per ml (ranging from 368.73 to 1706.04 μg per ml) after rhF9 plus IFA immunization (Figure 7b). These results demonstrate that immune tolerance was developed in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients after BG/BCNU treatment.

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Employing new gene transfer strategies to improve safety and efficacy are desirable for gene therapy. In order to improve platelet-FIX expression without increasing the risk of genotoxicities of 2bF9 gene therapy for hemophilia B, we developed a clinically translatable approach based on the MGMT P140K-medicated HSC gene delivery and drug selection system. In this study, we examined the power of BG/BCNU-mediated in vivo selection of hematopoietic cells transduced with 2bF9/MGMT LV in a hemophilia B murine model under a nonmyeloablative transplant precondition.

We chose the MGMT-mediated system along with BG/BCNU in vivo chemoselection for our study because this drug selection approach has been successfully applied in the treatment of several diseases, such as melanoma(Gajewski et al., 2005) and gliosarcoma(Blumenthal et al., 2015), as well as in thalassemia gene therapy(H. Wang et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2009). This system is built on knowledge that alkyltransferase MGMT functions to repair cellular DNA damage at the O6 position of guanine, conferring resistance to the cytotoxic effects of alkylating agent BCNU on hematopoietic cells and BG can inactive endogenous MGMT and increase a cell’s sensitivity to BCNU(Gajewski et al., 2005; D. Wang et al., 2008; Zielske et al., 2003). Because the MGMT variant P140K is resistant to the inhibition of BG, incorporating such a variant into the 2bF9 LV allows to effectively enrich transduced cells treated with BG/BCNU drug-selection either in vitro or in vivo.

Our studies confirm the feasibility to enrich 2bF9 genetically modified cells and enhance FIX expression using MGMT-mediated BG/BCNU drug-selection. Using an in vitro Dami cell model, we show that the transduction with 2bF9/MGMT LV conferred considerable drug resistance in treated cells. Only Dami cells that coexpressed 2bF9 and MGMT survived and were sustantially enriched, resulting in increased FIX expression after the BG/BCNU treatment. This in vitro selection model could be translated into a clinical situation, in which stem cells would be harvested for in vitro introduction of a 2bF9 gene, followed by in vitro BG/BCNU selection and reintroduced into the patient in an autologous transplant. In this scenario, transplantation of a sufficient number of selected cells will be critical as the remaining endogenous cells after sub-lethal irradiation could compete with the transplanted cells. Further evaluation of the feasibility of in vitro selection before transplantation is needed.

Since BCNU is a cytotoxic agent and BG can sensitize cells to respond to BCNU, we carefully chose the doses for selection.To reduce the potential for adverse effects from BCNU chemotherapy, we selected a high dose of BG to sensitize untransduced cells in combination with a low dose of BCNU for the in vivo study according to previous reports(Falahati et al., 2012; Schroeder et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2009; Zielske et al., 2003). We demonstrate that the combination of nonmyeloablative preconditioning (660 cGy) for BMT together with BG/BCNU in vivo chemoselection after bone marrow reconstitution was well tolerated by the FIXnull animal model. No overt signs of hematological toxicities such as thrombocytopenia were found in the 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients which received BG/BCNU treatment.

Importantly, this strategy was sufficient to enable engraftment and efficient in vivo enrichment of 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced hematopoietic cells in FIXnull mice. Both platelet FIX:Ag and FIX:C expression levels were significantly increased after drug therapy. Notably, the functional platelet FIX:C level was enhanced almost 4-fold after BG/BCNU treatment compared to pretreatment. As we know that the ratio of functional platelet-FIX:C to FIX:Ag can reflect the degree to which FIX is carboxylated, we found 48% of platelet FIX was functionally carboxylated at the 4th week after transplantation, which was the lowest level during the study course. Since FIX is a vitamin K-dependent protein, this low level could be due to vitamin K deficiency at the early phase after BMT as we and other groups previously reported(Y. Chen et al., 2014; Elston, Dudley, Shearer, & Schey, 1995; Toor, Slungaard, Hedner, Weisdorf, & Key, 2002).

Our data indicate that total BG/BCNU-mediated in vivo drug selection may impact in vivo vitamin K levels causing less effective γ-carboxylation of newly synthesized neoprotein FIX compared to our protocol using 2bF9 LV without the MGMT-mediated drug selection system(Y. Chen et al., 2014). Although the mechanism of this impact is still unclear, we speculate it could be due to reduced digestion capacity during BG/BCNU treatment as most of chemotherapeutics can affect gut function. Nevertheless, the bleeding phenotype was effectively corrected in FIXnull mice after 2bF9/MGMT gene therapy followed by in vivo drug selection as confirmed by the tail bleeding test. Thus, our studies well document the feasibility of MGMT P140K-mediated hematopoietic selection by BG/BCNU for platelet-targeted FIX gene therapy in hemophilia B mice.

Preventing and reducing inhibitor development is one of the major goals for hemophilia management. Overcoming immune responses to the vector and transgene product has been identified as a main concern in the gene therapy field(Cesana et al., 2014; Greig et al., 2018; Hart et al., 2019; Perrin et al., 2019; Ragni, 2016; Shi, 2018; Stephens et al., 2019). In our previous studies, we have demonstrated that platelet-derived gene therapy can be successful in treating hemophilia A with or without pre-existing anti-FVIII immunity(Shi, 2018). This gene therapy strategy in particular may induce FVIII-specific immune tolerance in hemophilia A (FVIIInull) mice even with pre-existing anti-FVIII immunity(J. Chen, Schroeder, Luo, Montgomery, & Shi, 2019; Y. Chen et al., 2017; Kuether et al., 2012; Schroeder et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2007). We also showed that infusion of FVIII genetically-modified platelets elicits neither primary nor memory immune responses to FVIII in FVIIInull mice, indicating that platelet-derived FVIII may be particularly beneficial for hemophilia A patients, especially for those with anti-FVIII immunity(Y. Chen et al., 2016). Our further study demonstrated that immune tolerance induced by platelet-targeted gene therapy occurs in the CD4+ T cell compartment(Y. Chen et al., 2017). In our most recent study, we identified two distinct mechanisms involved in immune tolerance in platelet-targeted gene transfer: antigen-specific CD4+ T cell clone deletion and antigen-specific regulatory T (Treg) cell induction(Luo et al., 2018). Here we show that 2bF9/MGMT LV-mediated transduction and transplantation followed by BG/BCNU treatment allowed for the selection of transduced hematopoietic cells and therefore resulted in the significant increase of platelet FIX expression levels in FIXnull mice. Meaningfully, we didn’t find any detectable levels of inhibitory or non-inhibitory antibodies in the recipients after using this novel gene therapy strategy with in vivo drug selection.

Our previous studies have demonstrated that FVIII-specific immune tolerance is established in hemophilia A mice after platelet-specific gene therapy when animals were challenged with antigen via intravenous administration(Schroeder et al., 2014). In the current study, we showed that even though mice were strongly challenged with exogenous rhF9 plus adjuvant, both anti-FIX inhibitors and total anti-FIX antibodies were barely detectable in BG/BCNU-treated 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients after immunization. In contrast, all FIXnull control mice produced high levels of anti-FIX antibodies. Our results suggest that FIX immune tolerance was induced in FIXnull mice after 2bF9/MGMT gene therapy and in vivo drug-selection of transduced cells. We previously reported that Treg cells play a critical role in immune tolerance induction in platelet-targeted gene therapy(Y. Chen et al., 2017; Luo et al., 2018). Although we have demonstrated that antigen-specific Treg cells are expanded after platelet-targeted gene therapy, it is unclear whether they are directly derived from genetically engineered by MGMT. If Treg cells were not genetically engineered by MGMT, they could be targeted and eliminated by BG/BCNU chemoselection. However, our data show that immune tolerance was still maintained in 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced recipients after BG/BCNU treatment. Our findings in the current study indicate that the Treg regulatory function might not be affected with this in vivo MGMT-mediated chemoselection of 2bF9/MGMT LV-transduced hematopoietic cells.

In summary, this current study demonstrates that the MGMT-mediated drug-selection system in platelet-targeted FIX gene therapy can significantly enhance therapeutic platelet-FIX expression, resulting in phenotypic correction and immune tolerance induction in FIXnull mice. Applying this strategy to a hemophilia B model with pre-existing immunity is worthy of further investigation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant HL-102035 (QS), the Bayer Hemophilia Foundation Award (QS), generous gifts from the Midwest Athletes Against Childhood Cancer Fund and the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin Children’s Research Foundation (QS), the Program of New Century Excellent Talents in Fujian Province University 2016B032 (YC), Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology in Fujian Province 2016Y9029 (YC), National Natural Science Foundation of China 81500158 (YC), and Backbone Talent Training Project of Fujian Provincial Health Commission 2019-ZQN-42 (YC).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

REFERENCES

- Arruda VR, Doshi BS, & Samelson-Jones BJ (2017). Novel approaches to hemophilia therapy: successes and challenges. Blood, 130(21), 2251–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DT, Rankin C, Stelzer KJ, Spence AM, Sloan AE, Moore DF Jr., … Rushing EJ (2015). A Phase III study of radiation therapy (RT) and O(6)-benzylguanine + BCNU versus RT and BCNU alone and methylation status in newly diagnosed glioblastoma and gliosarcoma: Southwest Oncology Group (SWOG) study S0001. Int J Clin Oncol, 20(4), 650–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana D, Ranzani M, Volpin M, Bartholomae C, Duros C, Artus A, … Montini E (2014). Uncovering and dissecting the genotoxicity of self-inactivating lentiviral vectors in vivo. Mol Ther, 22(4), 774–785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Schroeder JA, Luo X, Montgomery RR, & Shi Q (2019). The impact of GPIbalpha on platelet-targeted FVIII gene therapy in hemophilia A mice with pre-existing anti-FVIII immunity. J Thromb Haemost, 17(3), 449–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Luo X, Schroeder JA, Chen J, Baumgartner CK, Hu J, & Shi Q (2017). Immune tolerance induced by platelet-targeted factor VIII gene therapy in hemophilia A mice is CD4 T cell mediated. J Thromb Haemost, 15(10), 1994–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Schroeder JA, Chen J, Luo X, Baumgartner CK, Montgomery RR, … Shi Q (2016). The immunogenicity of platelet-derived FVIII in hemophilia A mice with or without preexisting anti-FVIII immunity. Blood, 127(10), 1346–1354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Schroeder JA, Kuether EL, Zhang G, & Shi Q (2014). Platelet gene therapy by lentiviral gene delivery to hematopoietic stem cells restores hemostasis and induces humoral immune tolerance in FIX(null) mice. Mol Ther, 22(1), 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elston TN, Dudley JM, Shearer MJ, & Schey SA (1995). Vitamin K prophylaxis in high-dose chemotherapy. Lancet, 345(8959), 1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falahati R, Zhang J, Flebbe-Rehwaldt L, Shi Y, Gerson SL, & Gaensler KM (2012). Chemoselection of allogeneic HSC after murine neonatal transplantation without myeloablation or post-transplant immunosuppression. Mol Ther, 20(11), 2180–2189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajewski TF, Sosman J, Gerson SL, Liu L, Dolan E, Lin S, & Vokes EE (2005). Phase II trial of the O6-alkylguanine DNA alkyltransferase inhibitor O6-benzylguanine and 1,3-bis(2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea in advanced melanoma. Clin Cancer Res, 11(21), 7861–7865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LA (2017). Hemophilia gene therapy comes of age. Blood Adv, 1(26), 2591–2599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LA, Sullivan SK, Giermasz A, Rasko JEJ, Samelson-Jones BJ, Ducore J, … High KA (2017). Hemophilia B Gene Therapy with a High-Specific-Activity Factor IX Variant. N Engl J Med, 377(23), 2215–2227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg SM, Rosenthal DS, Greeley TA, Tantravahi R, & Handin RI (1988). Characterization of a new megakaryocytic cell line: the Dami cell. Blood, 72(6), 1968–1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greig JA, Calcedo R, Kuri-Cervantes L, Nordin JML, Albrecht J, Bote E, … Wilson JM (2018). AAV8 Gene Therapy for Crigler-Najjar Syndrome in Macaques Elicited Transgene T Cell Responses That Are Resident to the Liver. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 11, 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart DP, Uzun N, Skelton S, Kakoschke A, Househam J, Moss DS, & Shepherd AJ (2019). Factor VIII cross-matches to the human proteome reduce the predicted inhibitor risk in missense mutation hemophilia A. Haematologica, 104(3), 599–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuether EL, Schroeder JA, Fahs SA, Cooley BC, Chen Y, Montgomery RR, … Shi Q (2012). Lentivirus-mediated platelet gene therapy of murine hemophilia A with pre-existing anti-factor VIII immunity. J Thromb Haemost, 10(8), 1570–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap D (2017). FIX It in One Go: Enhanced Factor IX Gene Therapy for Hemophilia B. Cell, 171(7), 1478–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo X, Chen J, Schroeder JA, Allen KP, Baumgartner CK, Malarkannan S, … Shi Q (2018). Platelet Gene Therapy Promotes Targeted Peripheral Tolerance by Clonal Deletion and Induction of Antigen-Specific Regulatory T Cells. Front Immunol, 9, 1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris M (2018). Hemophilia gene therapy is effective and safe. Blood, 131(9), 952–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesbach W, Meijer K, Coppens M, Kampmann P, Klamroth R, Schutgens R, … Leebeek FWG (2018). Gene therapy with adeno-associated virus vector 5-human factor IX in adults with hemophilia B. Blood, 131(9), 1022–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan PE, Sun J, Gui T, Hu G, Hannah WB, Wichlan DG, … Samulski RJ (2015). Employing a gain-of-function factor IX variant R338L to advance the efficacy and safety of hemophilia B human gene therapy: preclinical evaluation supporting an ongoing adeno-associated virus clinical trial. Hum Gene Ther, 26(2), 69–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montini E, Cesana D, Schmidt M, Sanvito F, Bartholomae CC, Ranzani M, … Naldini L (2009). The genotoxic potential of retroviral vectors is strongly modulated by vector design and integration site selection in a mouse model of HSC gene therapy. J Clin Invest, 119(4), 964–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani AC, Davidoff AM, & Tuddenham EGD (2017). Advances in Gene Therapy for Hemophilia. Hum Gene Ther, 28(11), 1004–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani AC, Reiss UM, Tuddenham EG, Rosales C, Chowdary P, McIntosh J, … Davidoff AM (2014). Long-term safety and efficacy of factor IX gene therapy in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med, 371(21), 1994–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathwani AC, Tuddenham EG, Rangarajan S, Rosales C, McIntosh J, Linch DC, … Davidoff AM (2011). Adenovirus-associated virus vector-mediated gene transfer in hemophilia B. N Engl J Med, 365(25), 2357–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pay SL, Qi X, Willard JF, Godoy J, Sankhavaram K, Horton R, … Boulton ME (2018). Improving the Transduction of Bone Marrow-Derived Cells with an Integrase-Defective Lentiviral Vector. Hum Gene Ther Methods, 29(1), 44–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin GQ, Herzog RW, & Markusic DM (2019). Update on clinical gene therapy for hemophilia. Blood, 133(5), 407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persons DA (2009). Hematopoietic stem cell gene transfer for the treatment of hemoglobin disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program, 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyvandi F, Garagiola I, & Young G (2016). The past and future of haemophilia: diagnosis, treatments, and its complications. Lancet, 388(10040), 187–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce GF, Coffin D, Members of the, W. F. H. G. T. R. T. P. C., & Organizing, C. (2019). The 1st WFH Gene Therapy Round Table: Understanding the landscape and challenges of gene therapy for haemophilia around the world. Haemophilia, 25(2), 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ragni MV (2016). Platelet VIII pack evades immune detection. Blood, 127(10), 1222–1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S, Tonnu N, Menon T, Lewis BM, Green KT, Wampler D, … Verma IM (2018). Autologous and Heterologous Cell Therapy for Hemophilia B toward Functional Restoration of Factor IX. Cell Rep, 23(5), 1565–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder JA, Chen Y, Fang J, Wilcox DA, & Shi Q (2014). In vivo enrichment of genetically manipulated platelets corrects the murine hemophilic phenotype and induces immune tolerance even using a low multiplicity of infection. J Thromb Haemost, 12(8), 1283–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q (2018). Platelet-Targeted Gene Therapy for Hemophilia. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 9, 100–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Fahs SA, Wilcox DA, Kuether EL, Morateck PA, Mareno N, … Montgomery RR (2008). Syngeneic transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells that are genetically modified to express factor VIII in platelets restores hemostasis to hemophilia A mice with preexisting FVIII immunity. Blood, 112(7), 2713–2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Kuether EL, Chen Y, Schroeder JA, Fahs SA, & Montgomery RR (2014). Platelet gene therapy corrects the hemophilic phenotype in immunocompromised hemophilia A mice transplanted with genetically manipulated human cord blood stem cells. Blood, 123(3), 395–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Wilcox DA, Fahs SA, Fang J, Johnson BD, Du LM, … Montgomery RR (2007). Lentivirus-mediated platelet-derived factor VIII gene therapy in murine haemophilia A. J Thromb Haemost, 5(2), 352–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomali N, Gharibi T, Vahedi G, Mohammed RN, Mohammadi H, Salimifard S, & Marofi F (2020). Mesenchymal stem cells as carrier of the therapeutic agent in the gene therapy of blood disorders. J Cell Physiol, 235(5), 4120–4134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A, Brewer AK, Mauser-Bunschoten EP, Key NS, Kitchen S, Llinas A, … Treatment Guidelines Working Group on Behalf of The World Federation Of, H. (2013). Guidelines for the management of hemophilia. Haemophilia, 19(1), e1–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens CJ, Lauron EJ, Kashentseva E, Lu ZH, Yokoyama WM, & Curiel DT (2019). Long-term correction of hemophilia B using adenoviral delivery of CRISPR/Cas9. J Control Release, 298, 128–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Hua B, Livingston EW, Taves S, Johansen PB, Hoffman M, … Monahan PE (2017). Abnormal joint and bone wound healing in hemophilia mice is improved by extending factor IX activity after hemarthrosis. Blood, 129(15), 2161–2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toor AA, Slungaard A, Hedner U, Weisdorf DJ, & Key NS (2002). Acquired factor VII deficiency in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplant, 29(5), 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Worsham DN, & Pan D (2008). Co-expression of MGMT(P140K) and alpha-L-iduronidase in primary hepatocytes from mucopolysaccharidosis type I mice enables efficient selection with metabolic correction. J Gene Med, 10(3), 249–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Georgakopoulou A, Psatha N, Li C, Capsali C, Samal HB, … Lieber A (2019). In vivo hematopoietic stem cell gene therapy ameliorates murine thalassemia intermedia. J Clin Invest, 129(2), 598–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyand AC, & Pipe SW (2019). New therapies for hemophilia. Blood, 133(5), 389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Pestina TI, Nasimuzzaman M, Mehta P, Hargrove PW, & Persons DA (2009). Amelioration of murine beta-thalassemia through drug selection of hematopoietic stem cells transduced with a lentiviral vector encoding both gamma-globin and the MGMT drug-resistance gene. Blood, 113(23), 5747–5756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zielske SP, Reese JS, Lingas KT, Donze JR, & Gerson SL (2003). In vivo selection of MGMT(P140K) lentivirus-transduced human NOD/SCID repopulating cells without pretransplant irradiation conditioning. J Clin Invest, 112(10), 1561–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]