Abstract

Background

COVID-19 and related containment policies have caused or heightened financial stressors for many in the USA. We assessed the relation between assets, financial stressors and probable depression during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Between 31 March 2020 and 13 April 2020, we surveyed a probability-based, nationally representative sample of US adults ages 18 and older using the COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being survey (n=1441). We calculated the prevalence of probable depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (cut-off ≥10) and exposure to financial stressors by financial, physical and social assets categories (household income, household savings, home ownership, educational attainment and marital status). We estimated adjusted ORs and predicted probabilities of probable depression across assets categories and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure groups.

Results

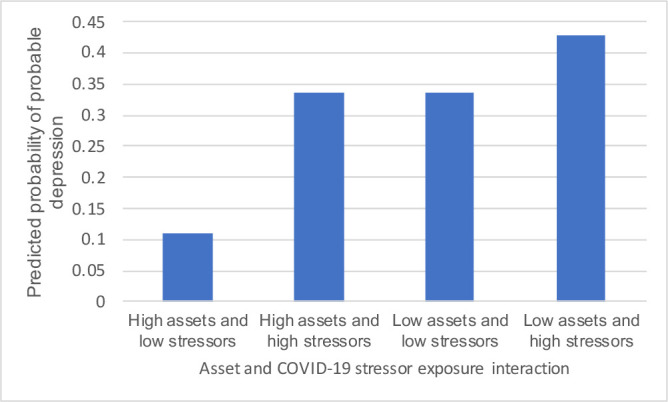

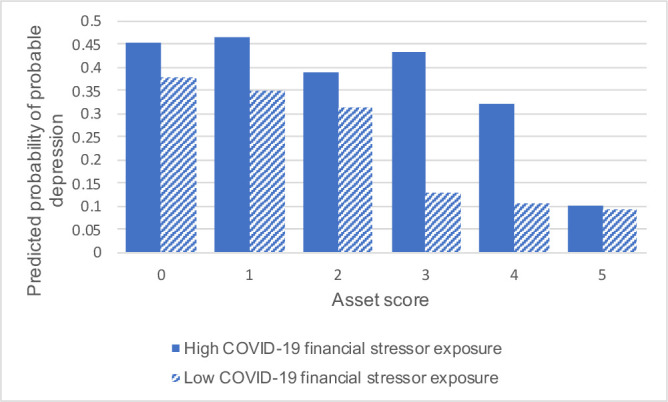

We found that (1) 40% of US adults experienced COVID-19-related financial stressors during this time period; (2) low assets (OR: 3.0, 95% CI 2.1 to 4.2) and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure (OR: 2.8, 95% CI 2.1 to 3.9) were each associated with higher odds of probable depression; and (3) among persons with low assets and high COVID-19 financial stressors, 42.7% had probable depression; and among persons with high assets and low COVID-19 financial stressors, 11.1% had probable depression. Persons with high assets and high COVID-19 financial stressors had a similar prevalence of probable depression (33.5%) as persons with low assets and low COVID-19 financial stressors (33.5%). The more assets a person had, the lower the level of probable depression.

Conclusion

Populations with low assets are bearing a greater burden of mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: depression, socio-economic, stress, inequalities, social inequalities

Introduction

The novel coronavirus outbreak has resulted in a pandemic that has changed the life of most Americans. By April 2020, 40 states were under stay-at-home orders and 39 closed non-essential businesses as the country attempted to mitigate the spread of the virus.1 As a consequence of the general national slowdown, the USA entered an economic recession, with 44.2 million unemployment claims as of June 2020.2

The co-occurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic recession set the stage for adverse mental health. There is abundant evidence that traumatic events are associated with an increased prevalence of mental illness.3–5 Examples include trauma related to natural disasters,6 terrorist events,7 and other epidemics such as Ebola8 and severe acute respiratory syndrome.9 Economic conditions are also associated with mental illness.10–13 Financial stress—made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic—is associated with higher odds of depression.14 Financial strain also has a cumulative effect on suicide attempts and ideation, with greater financial strain causing higher prevalence of suicide.15 Potential pathways to depression from economic recessions include unemployment,16 increased job stress, staff reduction and decreased wages,17 as well as cuts to mental health services.18

Lower socioeconomic indicators are associated with greater risk of mental illness19 20; conversely, wealth is associated with improved health, including mental health.21–23 There is ample evidence showing that as income increases the prevalence of common mood disorders and depression decreases.22 24–26 Outside of income, having access to liquid financial assets such as savings may also provide a safety net and reduce psychological distress; having more family wealth is associated with improved mental health.15 23 27 Having access to physical assets, such as owning a home, may afford additional stability associated with mental health. For example, housing instability is associated with mental illness,28 and home owners report lower levels of depression than renters.29 30 Mental illness is also greater among populations who have fewer social assets, such as lower educational attainment and being unmarried. Education is associated with improved mental health24 and reduced depression in particular.23 Being married is associated with improved mental health31 32 and confers with it improved economic standing.33 Populations who are at greater risk for mental illness before mass events are also most vulnerable to life disruptions after traumatic events occur3 and are also more likely to experience financial stressors related to those events.34

Early research on the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic suggests that mental illness is higher relative to pre-COVID-19 levels, consistent with data from other mass traumatic events.35–37 We do not know yet, however, which groups are experiencing the brunt of depression after COVID-19 or the role of financial stressors and assets in shaping this risk. It has been suggested that the economic recession emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic is ‘the most unequal in modern U.S. history’.38 Early reports suggest that persons most economically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic are the very people who were more vulnerable to begin with before the pandemic began; namely, persons with low income are more likely to experience unemployment.39 This double risk exposure—of having fewer assets to begin with and experiencing financial stressors due to COVID-19—may jointly contribute to greater influence on mental health, further deepening health divides. We aimed to understand (1) how assets are associated with the distribution of probable depression during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) how exposure to financial stressors during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with probable depression, and (3) how assets categories and exposure to financial stressors contribute jointly to probable depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. To address these questions, we assessed the relation between assets, COVID-19 financial stressors and depression in a nationally representative study of US adults ages 18 years and older in a 2-week period during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

This study was a cross-sectional observational study using original data collected through the COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being (CLIMB) survey. Surveys were distributed by NORC at the University of Chicago from 31 March 2020 through 13 April 2020. The survey was administered via web for most recipients (n=1385) and phone for others (n=85). Panellists were compensated a cash equivalent of $3 for taking our survey. Out of 2286 who were eligible, 1470 persons completed the survey, for a survey completion rate of 64.3%. Data were assigned poststratification weights to weigh survey responses to the February 2020 Current Population Survey. Informed consent was collected from participants when they joined the AmeriSpeak standing panel.

Sample

The sample for this study was a probability-based, nationally representative group of US adults ages 18 years and older from the NORC AmeriSpeak standing panel. NORC selects households using random selection with a known, non-zero probability from the NORC National Frame, which covers 97% of households in the USA. Panellists eligible for the survey were 18 years of age or over, spoke English and had completed a NORC survey in the past 6 months. Participants missing data on depression were excluded from the sample (n=29). The final sample included 1441 participants.

Key variables

Depression

We defined symptoms of probable depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). The PHQ-9 is a clinically validated diagnostic measuring past 2-week depression.40 Probable depression symptom scores were calculated, summing the total of the responses to the PHQ-9 questions. We used a symptoms cut-off score of 10 or greater, which has a sensitivity and specificity of 88%.40

COVID-19 financial stressors

COVID-19 financial stressor exposure was defined by endorsing one or more of the following COVID-19 life stressors: losing a job, a member of the household losing a job, having financial problems and having difficulty paying rent. High financial stressor exposure refers to endorsing COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure; low financial stressor exposure refers to the absence of endorsement of COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure.

Assets categories

Assets were defined as social assets (education and marital status), physical assets (home ownership) and financial assets (household income and household savings). Education was a categorical variable with four categories: ‘less than high school graduate, high school graduate or general education diploma (GED), some college, or college graduate or more’. Household income categories were defined across the IQR of income distributions: $0–$19 999; $20 000–$44 999; $45 000–$74 999; and ≥$75 000. Household savings were defined as $0–$4999; $5000–$9999; $10 000–$19 999; and ≥$20 000. Household savings included ‘money in all types of accounts, including cash, savings or checking accounts, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, retirement funds (such as pensions, IRAs, 401Ks, etc), and certificates of deposit’. We created an assets score from 1 to 5, with a value of 1 for having each of the following: household income above $45 000, household savings above $5000, home ownership, education (college or more) and being married. Persons with an assets score of ≥3 were included in the high assets group and persons with a score <3 were included in the low assets group. Assets score cut-offs were defined roughly at the median distribution of individual and cumulative assets.

COVID-19 stressors and assets interaction

We created an interaction term to represent the joint influence of COVID-19 stressors and assets during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using high/low financial stressor exposure and high/low assets grouping, we created four indicator terms representing the four potential scenarios: (1) high assets and low financial stressor exposure; (2) high assets and high financial stressor exposure; (3) low assets and low financial stressor exposure; and (4) low assets and high financial stressor exposure.

Demographics

We defined sex as a binary variable: female or male. We defined race/ethnicity as a categorical variable with five mutually exclusive categories: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Asian and other race (including multiple races). We defined age as a categorical variable across three groups: 18–39, 40–59 and ≥60 years. Household size was a categorical variable ranging from 1 to ≥7.

Analysis

All calculations were weighted to the US population. First, we measured the prevalence of COVID-19 financial stressor exposure and probable depression presence by asset category. Second, we conducted two-tailed χ2 analyses to measure significance of the associations between assets and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, measuring significance at a p value of 0.05. Third, we estimated the prevalence and 95% CI of probable depression presence by high and low assets and by COVID-19 financial stressor exposure status.

Fourth, we calculated the adjusted odds of depression using a multivariable logistic regression across four models, controlling for sex, age, race/ethnicity and household size. Model 1 measured the OR of probable depression for having low relative to high assets, controlling for demographics. Model 2 measured the OR of probable depression for COVID-19 financial stressor exposure relative to no exposure, controlling for demographics. Model 3 measured the odds of probable depression including COVID-19 financial stressor exposure and high or low assets category, controlling for demographics. Model 4 included an interaction term for high and low assets and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, controlling for demographic characteristics.

Our final model, model 4, was as follows:

Fifth, we estimated the predicted probability of depression using the final model, model 4, to estimate the adjusted prevalence of depression among the four strata of assets and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure: persons with high assets with high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure; persons with high assets with high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure; persons with low assets with low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure; and persons with low assets with low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. Sixth, we estimated the predicted probability of probable depression presence using model 4 by COVID-19 financial stressor exposure across asset scores (0–5). Complete case analysis was used for regression models. Complete cases for the final model included 1327 participants. Cases were missing values for assets score (n=112) and/or financial stressors score (n=3), for a total of 114 incomplete cases or 7.9%. There was no significant difference in reporting probable depression between the complete and incomplete cases included in the models. We used STATA V.16.1 for statistical analyses.

Results

The sample population was slightly more male (50.2% male), was majority non-Hispanic white (64.8% non-Hispanic white; 9.9% non-Hispanic Black; 17.7% Hispanic; 2.5% Asian; and 5.1% other race) and had slightly more young persons (18–39 years, 43.0%; 40–59 years, 32.1%; and ≥60 years, 25.0%), and was similar to the US population.

Table 1 shows the weighted prevalence of COVID-19 financial stressor exposure and probable depression by three asset types: financial assets (household income and household savings), physical assets (home ownership) and social assets (education, marital status). Of US adults 40% experienced any COVID-19 financial stressor and 27.8% exhibited probable depression. Table 1 also shows the weighted prevalence of COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. Of the weighted sample 27.3% endorsed having financial difficulties, 18.9% had a member of their household lose a job, 14.4% had difficulty paying rent, and 12.7% lost their job due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lower educational attainment, not being married, having lower household income, having lower household savings and being a home renter were associated with a higher prevalence of experiencing COVID-19 financial stressors.

Table 1.

Associations between assets, probable depression and COVID-19 financial stressors in US adults

| Sample | Probable depression | COVID-19 financial stressor exposure | Job loss | Job loss of a household member | Financial difficulties | Difficulty paying rent | ||||||||

| n | % | % | P value | % | P value | % | P value | % | P value | % | P value | % | P value | |

| Total | 1441 | 100 | 27.8 | 40.0 | 12.7 | 18.9 | 27.3 | 14.4 | ||||||

| Education | ||||||||||||||

| Less than high school graduate | 65 | 9.8 | 29.2 | <0.001 | 50.5 | <0.001 | 23.5 | 0.004 | 26.1 | 0.0301 | 37.9 | 0.001 | 23.2 | <0.001 |

| High school graduate or GED | 274 | 27.9 | 35.0 | 48.5 | 15.1 | 22.8 | 33.9 | 19.3 | ||||||

| Some college | 637 | 27.8 | 32.0 | 41.8 | 13.5 | 19.9 | 28.3 | 15.7 | ||||||

| College graduate or more | 465 | 34.5 | 18.3 | 28.8 | 7.1 | 12.9 | 18.1 | 7.0 | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||||||

| Married | 712 | 47.8 | 18.3 | <0.001 | 34.7 | 0.002 | 8.9 | 0.002 | 17.9 | 0.4863 | 20.9 | <0.001 | 9.2 | <0.001 |

| Not married | 729 | 52.2 | 36.5 | 44.9 | 16.2 | 19.8 | 33.1 | 19.3 | ||||||

| Household income | ||||||||||||||

| $0–$19 999 | 246 | 19.8 | 46.9 | <0.001 | 57.1 | <0.001 | 17.1 | 0.001 | 23.7 | 0.0458 | 45.3 | <0.001 | 25.4 | <0.001 |

| $20 000–$44 999 | 357 | 25.8 | 31.1 | 49.1 | 20.0 | 23.2 | 33.9 | 18.5 | ||||||

| $45 000–$74 999 | 357 | 25.1 | 23.3 | 33.0 | 8.6 | 14.5 | 20.3 | 10.5 | ||||||

| ≥$75 000 | 447 | 29.3 | 16.9 | 27.1 | 7.9 | 16.0 | 15.8 | 6.9 | ||||||

| Household savings | ||||||||||||||

| $0–$4999 | 577 | 43.2 | 40.4 | <0.001 | 54.9 | <0.001 | 15.9 | 0.012 | 21.4 | 0.0386 | 43.2 | <0.001 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| $5000–$9999 | 130 | 9.1 | 27.7 | 44.9 | 19.0 | 26.8 | 28.8 | 14.4 | ||||||

| $10 000–$19 999 | 123 | 7.7 | 21.9 | 37.9 | 18.9 | 22.4 | 15.1 | 7.3 | ||||||

| ≥$20 000 | 566 | 40.0 | 16.9 | 24.7 | 7.9 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 5.6 | ||||||

| Home ownership | ||||||||||||||

| Renter | 529 | 32.0 | 36.4 | <0.001 | 50.6 | <0.001 | 12.7 | 0.636 | 20.7 | 0.1913 | 35.1 | <0.001 | 25.3 | <0.001 |

| Owner | 850 | 68.0 | 23.0 | 33.8 | 11.5 | 16.9 | 22.4 | 8.4 | ||||||

Data: The COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being (CLIMB) study collected from 31 March 2020 through 13 April 2020 (n=1441). Nationally representative of US adults ages 18 years and older. Percentages are weighted. CLIMB missing data: household income (n=34), household savings (n=45), home ownership (n=62) and all COVID-19 stressors (n=3).

Two-tailed χ2 analysis conducted for significance testing. Frequencies (n) are unweighted. Percentages are weighted.

COVID-19 financial stressor exposure signifies that a person experienced at least one of the following COVID-19 stressors: losing a job, having a family member lose a job, having financial difficulties and having difficulty paying rent.

Probable depression defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score cut-off of ≥10.

GED, general education diploma.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of probable depression with 95% CI by high or low assets and exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors in US adults. Among persons with high assets and low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, 10.1% (95% CI 0.7 to 13.7) had probable depression. Among persons with high assets and high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, 34.2% (95% CI 26.2 to 43) had probable depression. Among persons with low assets and low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, 34.4% (95% CI 27.4 to 42.0) had probable depression. Among persons with low assets and high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure, 45.2% (95% CI 38.0 to 52.6) had probable depression.

Table 2.

Prevalence of probable depression with 95% CI by binary assets score and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure in US adults

| Low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure | High COVID-19 financial stressor exposure | |||

| % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Low assets | 34.4 | 27.4 to 42.0 | 45.2 | 38.0 to 52.6 |

| High assets | 10.1 | 0.7 to 13.7 | 34.2 | 26.2 to 43.1 |

Data: COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being study collected from 31 March 2020 through 13 April 2020 (n=1441). Nationally representative of US adults ages 18 years and older.

High assets defined by having three or more of the following: household income (above $45 000), household savings (above $5000), home ownership, education (college or more) and being married. High COVID-19 financial stressor exposure defined by experiencing one or more of the following COVID-19 stressors: losing a job, having a family member lose a job, having financial difficulties and having difficulty paying rent. Low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure refers to the absence of endorsement of COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure.

Probable depression defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score cut-off of ≥10.

Table 3 shows the relation between high or low assets, exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors, and probable depression among US adults using multivariable logistic regression across four models. All models controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, age and household size. Model 1 shows that persons with low assets had 3.0 (95% CI 2.1 to 4.2) times the odds of having probable depression than persons with a high asset score, controlling for demographics. Model 2 shows that persons with high COVID-19 financial stressors had 2.8 (95% CI 2.1 to 3.9) times the odds of having probable depression relative to persons with low COVID-19 financial stressors, controlling for demographics. In the model that included both exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors and assets level (model 3), persons with high exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors had 2.3 (95% CI 1.6 to 3.2) times the odds of depression relative to persons with low COVID-19 financial stressors and persons with high assets had 2.6 (95% CI 1.8 to 3.7) times the odds of depression relative to persons with low assets, controlling for demographics. Model 4 shows the interaction of assets level and COVID-19 stressors. The OR comparing persons with low assets with high COVID-19 financial stressors compared with persons with high assets and low COVID-19 financial stressors would be 6.4 (95% CI 4.0 to 10.3).

Table 3.

Relation between assets, COVID-19 financial stressor exposure and probable depression among US adults

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | Beta | OR (95% CI) | |

| Assets | |||||

| Low | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.2) | 2.6 (1.8 to 3.7) | 1.4 | n/a | |

| High | – | – | – | – | |

| COVID-19 financial stressors | |||||

| Low | – | – | – | – | |

| High | 2.8 (2.1 to 3.9) | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.2) | 1.4 | n/a | |

| Assets*COVID-19 financial stressor indicator | −1 | n/a | |||

| Low assets, low stressors | 6.4 (4.0 to 10.3) | ||||

| Low assets, low stressors | 4.3 (2.6 to 6.9) | ||||

| High assets, high stressors | 4.2 (2.5 to 7.2) | ||||

| High assets, low stressors | 1 | ||||

Data: COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being study collected from 31 March 2020 through 13 April 2020 (n=1441). Complete case analysis used for multiple logistic regression resulting in n=1327 for this model. Nationally representative of US adults ages 18 years and older.

All models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex and household size.

Probable depression defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score cut-off of ≥10.

Interaction indicator term: high or low assets*COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. High assets defined by having three or more of the following: household income (above $45 000), household savings (above $5000), home ownership, education (college or more) and being married. High COVID-19 financial stressor exposure defined by experiencing one or more of the following COVID-19 stressors: losing a job, having a family member lose a job, having financial difficulties and having difficulty paying rent. Low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure refers to the absence of endorsement of COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure.

Model 1 shows the odds of depression with no assets (not controlling for stressors). Model 2 shows the odds of depression with stressors (not controlling for assets). Model 3 shows the odds of depression with stressors and assets (no interaction term). Model 4 shows the odds of depression with stressors and assets and an interaction term between the two.

OR not given for variables where interactions are present since ORs are uninterpretable. Model parameters used to determine the relative odds of the relation between specific variables and depression.

n/a, not applicable.

Figure 1 shows the predicted probability of depression by high or low assets and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure cross-classification. Persons with low assets and high COVID-19 financial stressors had a predicted probability of depression of 42.7% (95% CI 35.4% to 49.9%).Persons with high assets and low COVID-19 financial stressors had a predicted probability of depression of 11.1% (95% CI 7.7 to 14.5). Persons with high assets and high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure had a predicted probability of depression of 33.5% (95% CI 25.2 to 41.8).

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of probable depression by asset level and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure interaction. Data: COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being study collected from 31 March 2020 through 13 April 2020 (n=1441). Nationally representative of US adults ages 18 years and older. All models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex and household size. Interaction indicator term: high or low assets*COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. High assets defined by having three or more of the following: household income (above $45 000), household savings (above $5000), home ownership, education (college or more) and being married. High COVID-19 financial stressor exposure defined by experiencing one or more of the following COVID-19 stressors: losing a job, having a family member lose a job, having financial difficulties and having difficulty paying rent. Low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure refers to the absence of endorsement of COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure. Probable depression defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score cut-off of ≥10.

Figure 2 shows the predicted probability of depression by assets score and COVID-19 financial stressor exposure interaction. Persons with a score of 1 had a predicted probability of depression of 45.4% among persons who had high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. Persons with a score of 5 had a predicted probability of depression of 10% among persons who had high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure.

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of probable depression by continuous assets score and COVID-19 stressor exposure interaction. Data: COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being study collected from 31 March 2020 to 13 April 2020 (n=1441). Nationally representative of US adults ages 18 years and older. All models controlled for age, race/ethnicity, sex and household size. Interaction indicator term: high or low assets*COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. High assets defined by having three or more of the following: household income (above $45 000), household savings (above $5000), home ownership, education (college or more) and being married. High COVID-19 financial stressor exposure defined by experiencing one or more of the following COVID-19 stressors: losing a job, having a family member lose a job, having financial difficulties and having difficulty paying rent. Low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure refers to the absence of endorsement of COVID-19-related financial stressor exposure. Probable depression defined as Patient Health Questionnaire-9 score cut-off of ≥10.

Discussion

Using data from a population-representative survey of the USA conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, we found the following: First, 40.0% of US adults experienced one or more COVID-19 financial stressors and 27.8% had probable depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Second, persons with fewer assets had a higher prevalence of both COVID-19 financial stressors and probable depression. We also found that having fewer assets and having financial stressors were each associated with probable depression. Third, there was an almost fourfold difference in the prevalence of probable depression for persons with low assets and high COVID-19 financial stressor exposure as compared with persons with high assets and low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure. Persons with high assets and high exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors had a similar prevalence of probable depression as persons with low assets and low COVID-19 financial stressor exposure.

Almost half of US adults experienced COVID-19 financial stressors and more than a quarter of US adults experienced probable depression during COVID-19. The percentage of the population with probable depression is consistent with what has been found during COVID-19. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on mental illness during COVID-19 found a pooled prevalence of depression of 28%, comparable with our finding of 27.8%.41 In a different study of US adults using the AmeriSpeak panel from 7 April to 13 April 2020, 13.6% of the population experienced serious psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic (relative to 27.8% experiencing probable depression in our survey).36 Our estimate of 12.7% reporting losing a job due to COVID-19 is comparable with a survey of 8869 adults using social media in the USA conducted in 14–16 March 2020, which reported 14.7% had lost their job or had reduced wages due to COVID-19.42

We found that persons with fewer assets were more likely to experience the financial stressors of COVID-19 and were more likely to have probable depression. Thus, the people who were more vulnerable before the pandemic (having lower assets at the onset of COVID-19) were more likely to bear the brunt of the financial stressors brought on by COVID-19. While there is a higher level of probable depression among all groups with exposure to COVID-19 financial stressors than without, persons with more assets fared better and persons with fewer assets fared worse. This is consistent with research outside of trauma,43 following other traumas,34 and COVID-19 in particular.35 44 Articles about COVID-19 and mental illness found that lower socioeconomic status (living in rural areas, having unstable income, having lower education) was associated with greater risk of depression globally. In the USA, in a national survey of adults during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of serious psychological distress was highest among lower household incomes, with 19.3% of adults with household incomes of less than $35 000 experiencing serious psychological distress.36 While all asset groups saw a higher-than-usual prevalence in probable depression, lower assets groups in particular had the higher burden of financial stressors and probable depression. Another study conducted in the USA found that participants who felt that coronavirus was a major threat to their personal finances or to the US economy were also significantly more likely to report psychological distress.44

We found that probable depression among persons with low assets and financial stressor exposure was more than six times greater than among persons with high assets and no financial stressors. Meanwhile, probable depression was similar among persons with low assets and low financial stressors and among persons with high assets and high financial stressors, speaking to the high levels of stress that low assets persons may feel even in the absence of COVID-induced stressors and to the inequity of probable depression between assets groups. Given what we know about economic recessions and financial strain, the period that follows the COVID-19 pandemic may expose vulnerable populations to ever greater hardship. During the Great Recession, US adults who had lower wealth before the recession experienced a larger increase in depressive symptoms relative to their counterparts with greater wealth.45 In a systematic review of 101 papers, economic recessions were associated with greater population mental illness.10 It is entirely possible, perhaps even likely, that there is a complex relation among the various stressors and depression. The trauma of the COVID-19 pandemic and its containment policies and the ensuing economic recession portends greater mental illness that likely will disproportionately affect low assets groups in the long term.

Given these findings, policy makers may consider enacting or enhancing policies to reduce the burden of financial stressors, particularly for low-resource groups, towards the end of mitigating mental illness. Policies that protect the social determinants of mental health, such as secure housing, income, employment and access to healthcare outside of employment, may reduce the impact of this moment on mental health.19 46 Policy makers may consider, for example, eviction moratoria,47 48 income support (such as through extending the Paycheck Protection Program49 or the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act stimuli,50 51 or other universal basic income interventions52), paid sick leave,53 and health insurance that is not tied to employment.53 In general, countries with more generous social and economic policies (such as family leave, social insurance and sick benefits) have lower rates of mental illness and lower levels of inequality.54 While the literature around specific policy interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic is still being developed, a nationally representative study conducted by Barry et al in April 2020 found broad public support for government-subsidised income support, health insurance and unemployment support to ameliorate the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.55 Support was strongest for 2-week paid sick leave for all workers. Policy efforts to reduce the economic influence of the pandemic could improve population mental health, reduce widening inequities and be met with public support. Last, providers should be aware of these trends, and may consider their patients’ financial and stressor contexts when screening for depression and identifying people who may benefit from mental health treatment.

There are three main limitations to this analysis. First, the relation between probable depression and financial strain can be bidirectional; given the cross-sectional nature of our study, we can speak only to observed associations. Because the construct of financial strain we have measured is tied to stressors caused by COVID-19, and because of the quick and broad nature of the effects of COVID-19, we feel more confident that financial stressors were more likely to be caused by COVID-19 than by the underlying mental illness of participants. Additionally, when we both controlled for, and stratified by, previous diagnosis of depression, we found that the association between COVID-19 financial stressors and depression remained statistically significant, suggesting that the presence of COVID-19-induced stressors may have influenced depression, even among those with no history of depression diagnosis. Second, COVID-19 peaked at different times in different cities, and the economic consequences of the pandemic may not have yet been realised across the full sample. This study was not designed to assess regional differences and provides a snapshot of probable depression, exposure to financial stressors and current assets between 31 March and 13 April 2020. We found no significant differences in variation of our outcomes of interest by four-level census regional divisions (Northeast Region, Midwest Region, South Region, West Region).56 Third, while the PHQ-9 is a validated instrument for assessing symptoms of probable depression,40 a gold standard for depression diagnosis would come from a clinician or medical professional. Nonetheless, the PHQ-9 allows for rapid and validated assessment of symptoms of probable depression, allowing us to ascertain with some confidence depressive symptoms in the surveyed population.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we found that (1) almost half of US adults experienced COVID-19-induced financial stressors; (2) lower assets were associated with higher prevalence of financial stressors and of probable depression during COVID-19; (3) having lower assets and experiencing financial stressors together created an even higher burden of mental illness; and (4) the people who are most at risk in society are also those who experienced the greatest stressors due to COVID-19, such as losing jobs or having household members lose jobs, financial difficulties, and difficulties paying rent. Left unchecked, the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic will accrue to persons who are already vulnerable, widening mental health divides in the USA.

What is already known on this subject.

Persons with low assets are known to have higher rates of depression than their wealthier counterparts, and that they fare worse following traumatic events and economic recessions.

We do not know the mental health of low assets persons during the COVID-19 pandemic, the prevalence of COVID-19 financial stressors, or the joint effect of how having low assets and financial stressor exposure may influence depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What this study adds.

This paper documented the relation between assets, financial stressors and probable depression among US adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We found that persons with fewer assets had higher exposure to financial stressors due to COVID-19 and a higher prevalence of probable depression than persons with more assets.

Predicted probability of depression among persons with low assets exposed to financial stressors during COVID-19 was four times greater than among persons with high assets without financial stressors.

The findings showed that persons with low assets were most likely to have poor mental health during COVID-19 and that this burden was compounded by the joint influence of COVID-19 financial stressors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Melissa Clark and Dr Sylvia Shangani for their help in the design and execution of this study. The authors also wish to thank the study participants for sharing their experience during a challenging time for the country.

Footnotes

Contributors: CKE designed the study, analysed data and wrote the paper. SMA contributed edits to the paper. GHC and LS contributed to the analysis and edits to the paper. PMV and SG provided supervision to the study, assisted with study design, contributed to the analysis and edited the paper.

Funding: This study was funded in part through support from the Rockefeller Foundation-Boston University 3-D Commission. CKE worked on this project while funded by the National Institutes of Health (T32 AG 23 482-15).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by NORC Institutional Review Board (IRB00000967) (IRB protocol number: 20.03.17; project number: 8787) and Boston University Medical Campus (IRB number: H-39986).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data from the COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being (CLIMB) study available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Raifman J, Nocka K, Jones D, et al. . COVID-19 US state policy database (CUSP), 2020. Available: www.tinyurl.com/statepolicies

- 2.U.S. Department of Labor Unemployment insurance Weekly claims. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Labor, 2020. https://www.dol.gov/ui/data.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tracy M, Norris FH, Galea S. Differences in the determinants of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression after a mass traumatic event. Depress Anxiety 2011;28:666–75. 10.1002/da.20838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clous EA, Beerthuizen KC, Ponsen KJ, et al. . Trauma and psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017;82:794–801. 10.1097/TA.0000000000001371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kraan T, Velthorst E, Smit F, et al. . Trauma and recent life events in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 2015;161:143–9. 10.1016/j.schres.2014.11.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldmann E, Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:169–83. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H, et al. . Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. N Engl J Med 2002;346:982–7. 10.1056/NEJMsa013404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jalloh MF, Li W, Bunnell RE, et al. . Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000471. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, et al. . SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10:1206–12. 10.3201/eid1007.030703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frasquilho D, Matos MG, Salonna F, et al. . Mental health outcomes in times of economic recession: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 2016;16:115. 10.1186/s12889-016-2720-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilkinson LR. Financial strain and mental health among older adults during the great recession. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2016;71:745–54. 10.1093/geronb/gbw001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haw C, Hawton K, Gunnell D, et al. . Economic recession and suicidal behaviour: possible mechanisms and ameliorating factors. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2015;61:73–81. 10.1177/0020764014536545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, et al. . Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet 2013;381:1323–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60102-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dijkstra-Kersten SMA, Biesheuvel-Leliefeld KEM, van der Wouden JC, et al. . Associations of financial strain and income with depressive and anxiety disorders. J Epidemiol Community Health 2015;69:660–5. 10.1136/jech-2014-205088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elbogen EB, Lanier M, Montgomery AE, et al. . Financial strain and suicide attempts in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Am J Epidemiol 2020;189:1266–74. 10.1093/aje/kwaa146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marazziti D, Avella MT, Mucci N, et al. . Impact of economic crisis on mental health: a 10-year challenge. CNS Spectr 2020:1–7. 10.1017/S1092852920000140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mucci N, Giorgi G, Roncaioli M, et al. . The correlation between stress and economic crisis: a systematic review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:983–93. 10.2147/NDT.S98525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Hal G. The true cost of the economic crisis on psychological well-being: a review. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2015;8:17–25. 10.2147/PRBM.S44732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen J, Marmot M, World Health Organization, . Social determinants of mental health, 2014. Available: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112828/1/9789241506809_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 20 Jul 2019].

- 20.Stansfeld SA, Head J, Marmot MG. Explaining social class differences in depression and well-being. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998;33:1–9. 10.1007/s001270050014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollack CE, Chideya S, Cubbin C, et al. . Should health studies measure wealth? A systematic review. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:250–64. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kourouklis D, Verropoulou G, Tsimbos C. The impact of wealth and income on the depression of older adults across European welfare regimes. Ageing Soc 2020;40:2448–79. 10.1017/S0144686X19000679 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Galea S. Is wealth associated with depressive symptoms in the United States? Ann Epidemiol 2020;43:25–31. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawachi I, Adler NE, Dow WH. Money, schooling, and health: mechanisms and causal evidence. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010;1186:56–68. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ettner SL. New evidence on the relationship between income and health. J Health Econ 1996;15:67–85. 10.1016/0167-6296(95)00032-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Golberstein E. The effects of income on mental health: evidence from the social security Notch. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2015;18:27–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lê-Scherban F, Brenner AB, Schoeni RF. Childhood family wealth and mental health in a national cohort of young adults. SSM Popul Health 2016;2:798–806. 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burgard SA, Seefeldt KS, Zelner S. Housing instability and health: findings from the Michigan recession and recovery study. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:2215–24. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Szabo A, Allen J, Alpass F, et al. . Longitudinal trajectories of quality of life and depression by housing tenure status. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2018;73:e165–74. 10.1093/geronb/gbx028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ettman CK, Cohen GH, Vivier PM, et al. . Savings, home ownership, and depression in low-income us adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2020. doi: 10.1007/s00127-020-01973-y. [Epub ahead of print: 11 Nov 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horwitz AV, White HR, Howell-White S. Becoming married and mental health: a longitudinal study of a cohort of young adults. J Marriage Fam 1996;58:895–907. 10.2307/353978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braithwaite S, Holt-Lunstad J. Romantic relationships and mental health. Curr Opin Psychol 2017;13:120–5. 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stimpson JP, Wilson FA, Peek MK. Marital status, the economic benefits of marriage, and days of inactivity due to poor health. Int J Popul Res 2012;2012:1–6. 10.1155/2012/568785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, et al. . Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress 2008;21:357–68. 10.1002/jts.20355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, et al. . Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113172. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, et al. . Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA 2020;324:93. 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, et al. . Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2019686. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Long H, van Dam A, Fowers A, et al. . The covid-19 recession is the most unequal in modern U.S. history. Washington post. Available: https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/2020/business/coronavirus-recession-equality/ [Accessed 1 Oct 2020].

- 39.Baer EM Theo Francis and Justin The Covid economy Carves deep divide between haves and have-nots. wall Street Journal, 2020. Available: https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-covid-economy-carves-deep-divide-between-haves-and-have-nots-11601910595 [Accessed 6 Oct 2020].

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, et al. . The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020;291:113190. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. . US public concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic from results of a survey given via social media. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1020–2. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cronkite RC, Woodhead EL, Finlay A, et al. . Life stressors and resources and the 23-year course of depression. J Affect Disord 2013;150:370–7. 10.1016/j.jad.2013.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holingue C, Badillo-Goicoechea E, Riehm KE, et al. . Mental distress during the COVID-19 pandemic among US adults without a pre-existing mental health condition: findings from American trend panel survey. Prev Med 2020;139:106231. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Riumallo-Herl C, Basu S, Stuckler D, et al. . Job loss, wealth and depression during the great recession in the USA and Europe. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:1508–17. 10.1093/ije/dyu048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shim RS. Mental health inequities in the context of COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2020104. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsai J, Huang M. Systematic review of psychosocial factors associated with evictions. Health Soc Care Community 2019;27:e1–9. 10.1111/hsc.12619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vásquez-Vera H, Palència L, Magna I, et al. . The threat of home eviction and its effects on health through the equity lens: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2017;175:199–208. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Humphries JE, Neilson CA, Ulyssea G. Information frictions and access to the Paycheck protection program. J Public Econ 2020;190:104244. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.U.S. Department of the Treasury The cares act provides assistance to workers and their families. Available: https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/cares/assistance-for-american-workers-and-families [Accessed 11 Nov 2020].

- 51.Wright AL, Sonin K, Driscoll J, et al. . Poverty and economic dislocation reduce compliance with COVID-19 shelter-in-place protocols. J Econ Behav Organ 2020;180:544–54. 10.1016/j.jebo.2020.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnson MT, Johnson EA, Webber L, et al. . Mitigating social and economic sources of trauma: the need for universal basic income during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychol Trauma 2020;12:S191–2. 10.1037/tra0000739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lynch J, Equity H. Health equity, social policy, and promoting recovery from COVID-19. J Health Polit Policy Law 2020;45:983–95. 10.1215/03616878-8641518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McAllister A, Fritzell S, Almroth M, et al. . How do macro-level structural determinants affect inequalities in mental health? - a systematic review of the literature. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:180. 10.1186/s12939-018-0879-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barry CL, Han H, Presskreischer R, et al. . Public support for social safety-net policies for COVID-19 in the United States, April 2020. Am J Public Health 2020;110:1811–3. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.The United States Census Bureau Geographic levels. Available: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/economic-census/guidance-geographies/levels.html [Accessed 11 Nov 2020].