SUMMARY

Concurrent loss-of-function mutations in STK11 and KEAP1 in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) are associated with aggressive tumor growth, resistance to available therapies, and early death. We investigated the effects of coordinate STK11 and KEAP1 loss by comparing co-mutant with single mutant and wild-type isogenic counterparts in multiple LUAD models. STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation results in significantly elevated expression of ferroptosis-protective genes, including SCD and AKR1C1/2/3, and resistance to pharmacologically induced ferroptosis. CRISPR screening further nominates SCD (SCD1) as selectively essential in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. Genetic and pharmacological inhibition of SCD1 confirms the essentiality of this gene and augments the effects of ferroptosis induction by erastin and RSL3. Together these data identify SCD1 as a selective vulnerability and a promising candidate for targeted drug development in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD.

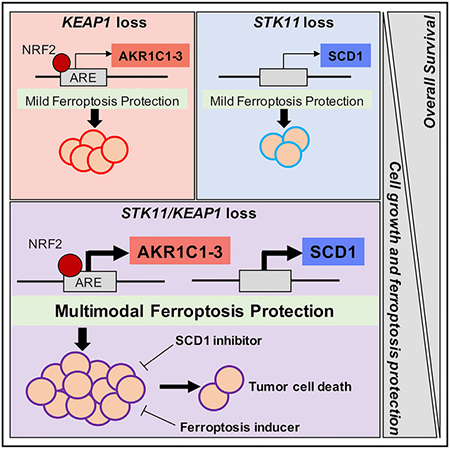

Graphical Abstract

In Brief

Wohlhieter et al. explore the global changes in gene expression and oncogenic signaling pathways driven by concurrent loss of function in two tumor suppressor genes, STK11 and KEAP1. They identify a molecular vulnerability, in which co-mutant cells depend on ferroptosis protective mechanisms for survival, and highlight SCD1 as an essential gene and promising drug target.

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer mortality, accounting for about 12% of newly diagnosed cases and about 18% of total cancer deaths worldwide (Bray et al., 2018). The most common histologic subtype of lung cancer is lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), making up approximately 50% of cases (Herbst et al., 2008). In recent years, dramatic progress has been made in tailoring therapies for subgroups of patients with LUAD harboring known oncogenic mutations or translocations in genes, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, 28%), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK, 3.8%), ROS proto-oncogene 1 (ROS1, 2.6%), and others (Jordan et al., 2017). Genetic profiling and targeting of these oncogenic drivers have markedly improved clinical outcomes of patients with these sub-types of LUAD. Unfortunately, only a few patients benefit from those approaches. At the other end of the spectrum of oncogenic mutations in LUAD are drivers that have not been successfully profiled or targeted to date and that are associated with particularly poor prognosis. Using mutational profiling data from a cohort of more than 1,000 patients with metastatic LUAD, our group recently identified concurrent loss-of-function mutations in two genes as a defining factor of strikingly poor prognosis in a subset of patients with LUAD; serine/threonine kinase 11 (STK11), encoding the protein LKB1, and Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1). This co-mutation occurs in10.2% of metastatic LUAD and defines a patient cohort with a median overall survival of only 7.3 months (Shen et al., 2019). Inactivating mutations in either STK11 or KEAP1 have been previously analyzed in the context of oncogenic KRAS mutations in LUAD, but their co-association with poor prognosis appears to be independent of KRAS status. Biological mechanisms favoring the coordinated loss of these two genes and clinically tractable therapeutic vulnerabilities of this subset of LUAD have not been defined. Identifying therapeutic strategies for those exceptionally poor prognosis LUAD cases is a critical need.

STK11 is the third most commonly mutated gene in LUAD, after TP53 and KRAS, and has been identified in up to 33% of primary LUADs (Gleeson et al., 2015). STK11 encodes a serine/threonine kinase, LKB1, which activates a family of 12 downstream kinases, including AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), and has a role in essential biological functions, including cellular energy regulation. We have previously reported STK11 mutations in the context of KRAS-mutant LUAD to be strongly associated with resistance to immunotherapy (Skoulidis et al., 2018).

Approximately 17% of patients with LUAD have loss-of-function mutations in KEAP1 (Collisson et al., 2014). KEAP1 encodes a key factor controlling the antioxidant response pathway, functioning as a negative regulator of the transcription factor nuclear factor erythroid-1 like 2 (NFE2L2/NRF2) (Rojo de la Vega et al., 2018). Loss of KEAP1 increases both protein stability and nuclear translocation of NRF2, which, in turn, alters the transcription of genes involved in cellular antioxidant, detoxification, and metabolic pathways. We have previously reported that KRAS-mutant LUADs with concomitant KEAP1 loss have an increased dependence on glutaminolysis (Romero et al., 2017) and shorter survival when treated with either chemotherapy or immunotherapy (Arbour et al., 2018).

To better define interventional targets for these therapeutically refractory cancers, this study investigated the global changes in gene expression and oncogenic signaling pathways driven by concomitant loss of STK11 and KEAP1 versus loss of either or neither of those genes. We characterized that co-mutation across multiple models, including isogenic human LUAD cell lines generated by selective gene knockout, and cell line xenografts from cancers harboring those mutations de novo. We used the isogenic models in a targeted CRISPR/Cas9 screen to define candidate therapeutic vulnerabilities specifically associated with concomitant STK11/KEAP1 loss. Our data demonstrate that concomitant loss of STK11 and KEAP1 drives ferroptosis protection and identifies a key negative regulator of this cell death pathway, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), as a critical and selective dependency in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD.

RESULTS

STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutation Predicts Short Overall Survival in Patients with LUAD, Independent of KRAS Status

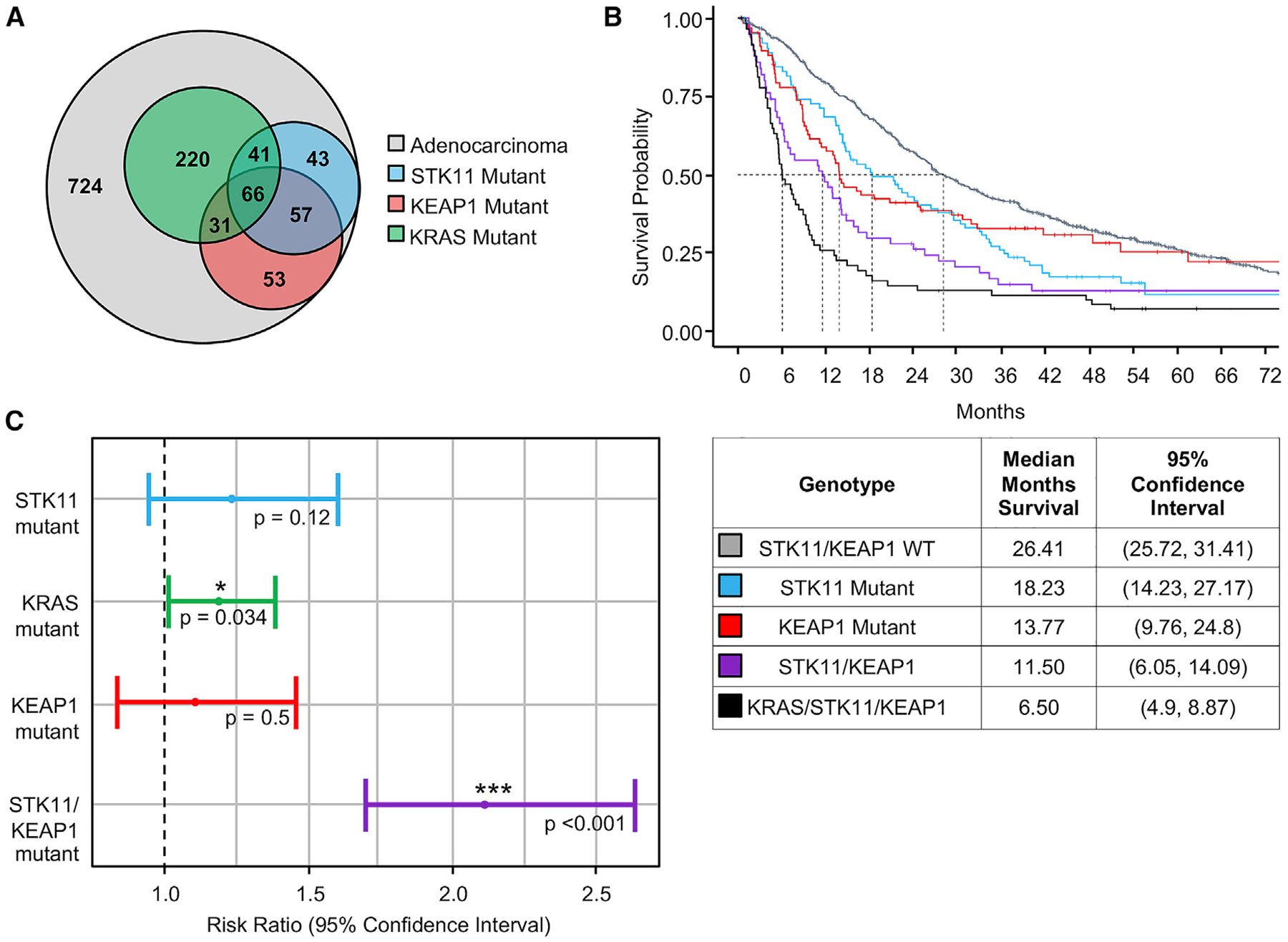

MSK-IMPACT (Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutation Profiling of Actional Cancer Targets) is a clinically deployed next-generation sequencing panel that detects mutations, select translocations, and copy number alterations in more than 340 cancer-associated genes (Cheng et al., 2015). We queried a cohort of 1,235 sequentially profiled metastatic LUAD patients for tumor-specific somatic mutations in STK11 only (n = 43), KEAP1 only (n = 53), or both (n = 57) (Figure 1A). We included a third mutation in our analysis, KRAS (n = 358), to specifically assess the role of KRAS mutation in dictating survival for STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant patients. KRAS mutations often co-occur with STK11 (n = 41), KEAP1 (n = 31), and STK11/KEAP1 (n = 66); however, recent findings suggest that STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation independently predicts a high-risk patient cohort (Shen et al., 2019). We observed a marked decrease in median overall survival from 26.4 months in patients with wild-type (WT) STK11/KEAP1 alleles to 11.5 months in patients harboring the STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation (KRAS WT) and to 6.5 months in patients harboring KRAS/STK11/KEAP1 triple-mutation, with single mutants having intermediate survival (Figure 1B). In multivariate analysis, STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant status significantly (p < 0.001) predicted poor survival, independent of KRAS status (Figure 1C). To date, the biological link between loss of STK11 and KEAP1 has only been studied in the context of a KRAS-driver mutation. Based on our data, these studies exclude nearly 50% of patients with STK11/KEAP1 co-mutations who do not harbor a KRAS mutation but who are still at exceptionally high risk for early death. Taken together, these findings support the need for a better understanding of the biology driving STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD, with or without a KRAS mutation, to identify therapeutic vulnerabilities for the entire high-risk patient cohort.

Figure 1. Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma and STK11 and KEAP1 Co-mutation Have Lower Overall Survival, Independent of KRAS Status.

(A) Venn diagram indicates number of patients with late-stage, metastatic lung adenocarcinoma in the MSK IMPACT database that are wild-type for STK11 and KEAP1 (light gray), mutant for STK11 (blue), mutant for KEAP1 (red), and mutant for KRAS (green).

(B) Kaplan-Meyer curve shows overall survival of patients with the indicated tumor genotype. Groups are mutually exclusive, where each patient falls into a single category with no overlap. The table indicates average overall survival across each group and 95% confidence interval.

(C) Multivariate Cox regression analysis for each indicated variable was performed. The risk ratio is the ratio of overall survival corresponding to each indicated variable. KRAS and STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant are independently identified as significant covariates for overall survival (p < 0.05).

Given the size of the available clinical dataset, we explored whether particular mutations within STK11 or KEAP1 favored acquisition of the co-mutation and whether genomic profiling of single- and double-mutant tumors could inform the relative timing of STK11 and KEAP1 mutation in LUAD formation. For that analysis, we included patients with LUAD at all stages. Mutation location within the STK11 or KEAP1 genes did not differ between single mutants and co-mutants, consistent with a wide array of mutations resulting in loss of function (Figure S1A). In an attempt to gain insight into the ordering of mutations in tumorigenesis, we analyzed the cancer cell fraction (CCF) of STK11 and KEAP1 mutations in all patients with LUAD harboring the STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation in the MSK-IMPACT-sequencing cohort who had the necessary allele-specific copy number data (n = 292) (Shen and Seshan, 2016). We found that mutations in STK11 and KEAP1 are both clonal in 84% of samples containing both mutations (Figure S1B). Nearly 90% of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors demonstrate a loss-of-heterozygosity (LOH) event on chromosome 19, where both STK11 and KEAP1 reside. This rate of LOH is significantly higher (p < 0.001) than the occurrence of LOH in either single mutant and is nearly 60% higher than the occurrence in tumors with no loss of STK11 or KEAP1 (Figure S1C). Given the chromosomal proximity of STK11 and KEAP1, LOH as a mechanism of selecting against WT alleles by coordinately deleting a copy of both genes provides insight into the acquisition of the co-mutation in oncogenesis but, coupled with the observed clonality, prevents analysis into whether there is selective pressure in the temporal order of gene disruption.

STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutation Promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation In Vitro and Tumor Growth In Vivo

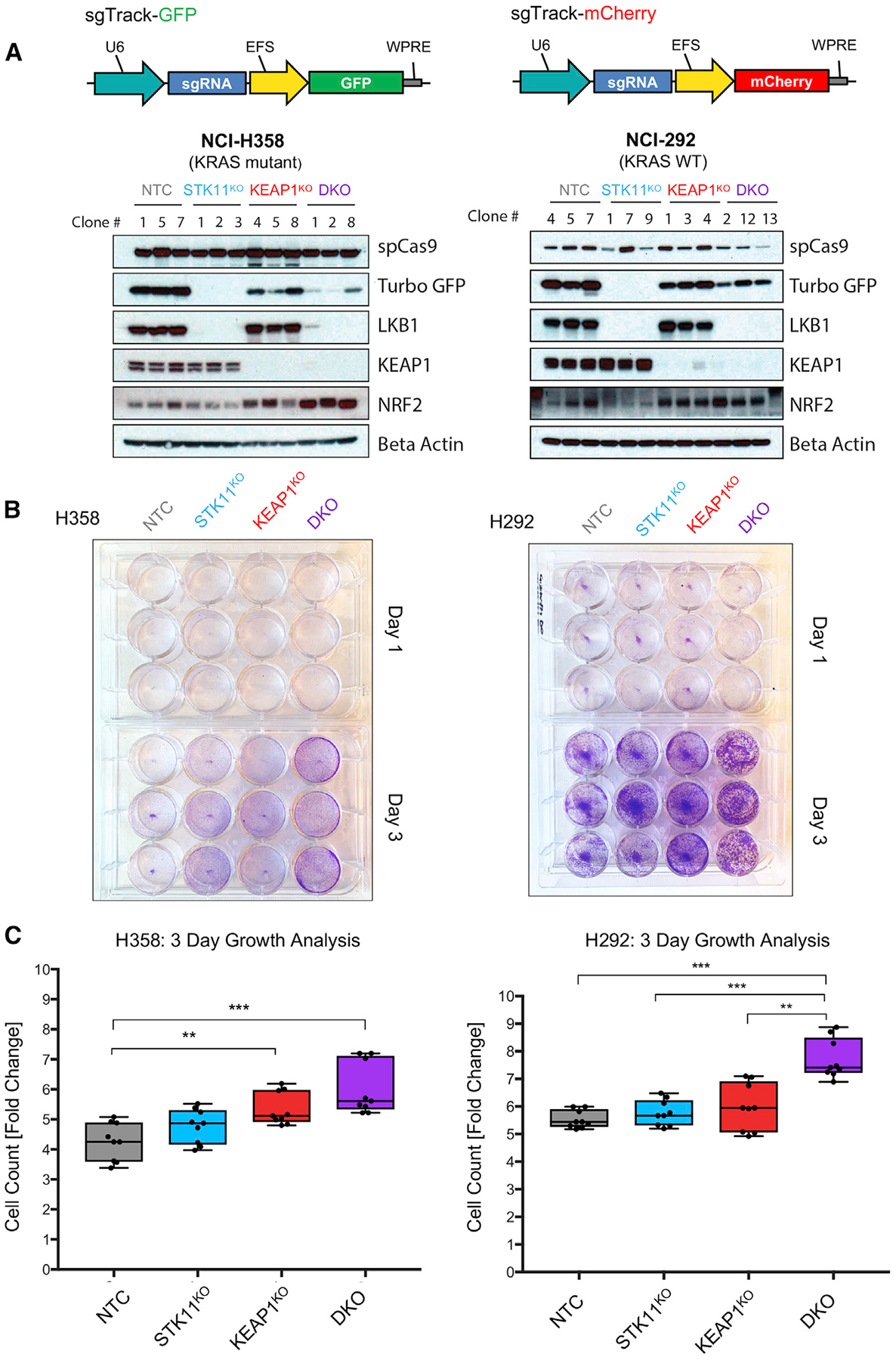

Mutations in STK11 and KEAP1 have each independently been reported to promote cell proliferation in the context of KRAS mutations (Murray et al., 2019; Romero et al., 2017). Given our clinical data supporting STK11/KEAP1 cooperativity, regardless of KRAS status, we investigated whether loss-of-function mutations in both STK11 and KEAP1 promote cell proliferation more than either single gene loss in a KRAS-independent manner. We used CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing to create stable knockouts of STK11, KEAP1, or both genes in two LUAD lines, H358 and H292. H358 harbors the oncogenic KRAS mutation G12C, whereas H292 is WT for KRAS. We created singe-cell clones harboring either a control non-targeting guide (NTC), STK11 mutation (STK11KO), KEAP1 mutation (KEAP1KO), or both (double-knockout [DKO]) (Figure 2A). To assess cell proliferation, we tracked the growth of H358 and H292 isogenic clones over time. Supporting the tumor-suppressive nature of STK11 and KEAP1, we observed an approximate doubling in growth rates in DKO derivatives of both H358 and H292 relative to WT controls (p = 0.0002 and p < 0.0001, respectively), with single-gene knockouts demonstrating intermediate phenotypes (Figures 2B and 2C). These data support our hypothesis that STK11 and KEAP1 co-mutations cooperate to promote cell growth, independent of KRAS status.

Figure 2. STK11 and KEAP1 Co-mutation Promotes Cell Growth, Independent of KRAS Mutation Status.

(A) Vector maps of the lentiviral vectors used to create single-cell isogenic clones expressing either GFP or mCherry as a marker of sgRNA expression. Immunoblots of protein expression in H358 and H292 cell lines transduced with Cas9 and one or more of the following guide RNA vectors: sgTrack-GFP-NTC (non-targeting control), sgTrack-mCherry-sgSTK11, and sgTrack-GFP-sgKEAP1. Clone number indicates the single-cell clones identified to have complete loss of the indicated protein(s).

(B) Crystal violet staining assays of the cell growth of three isogenic clones from each genotype group from day 1 after plating and day 3 in culture.

(C) Measurement of fold-change in fluorescent intensity over 3 days for each clone. Three technical replicates were performed for each of the three biological replicates. Significance was calculated by a two-sample t test between samples at each end of the bracket. A Bonferroni correction was performed across the six tests so that *p < 0.008, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002.

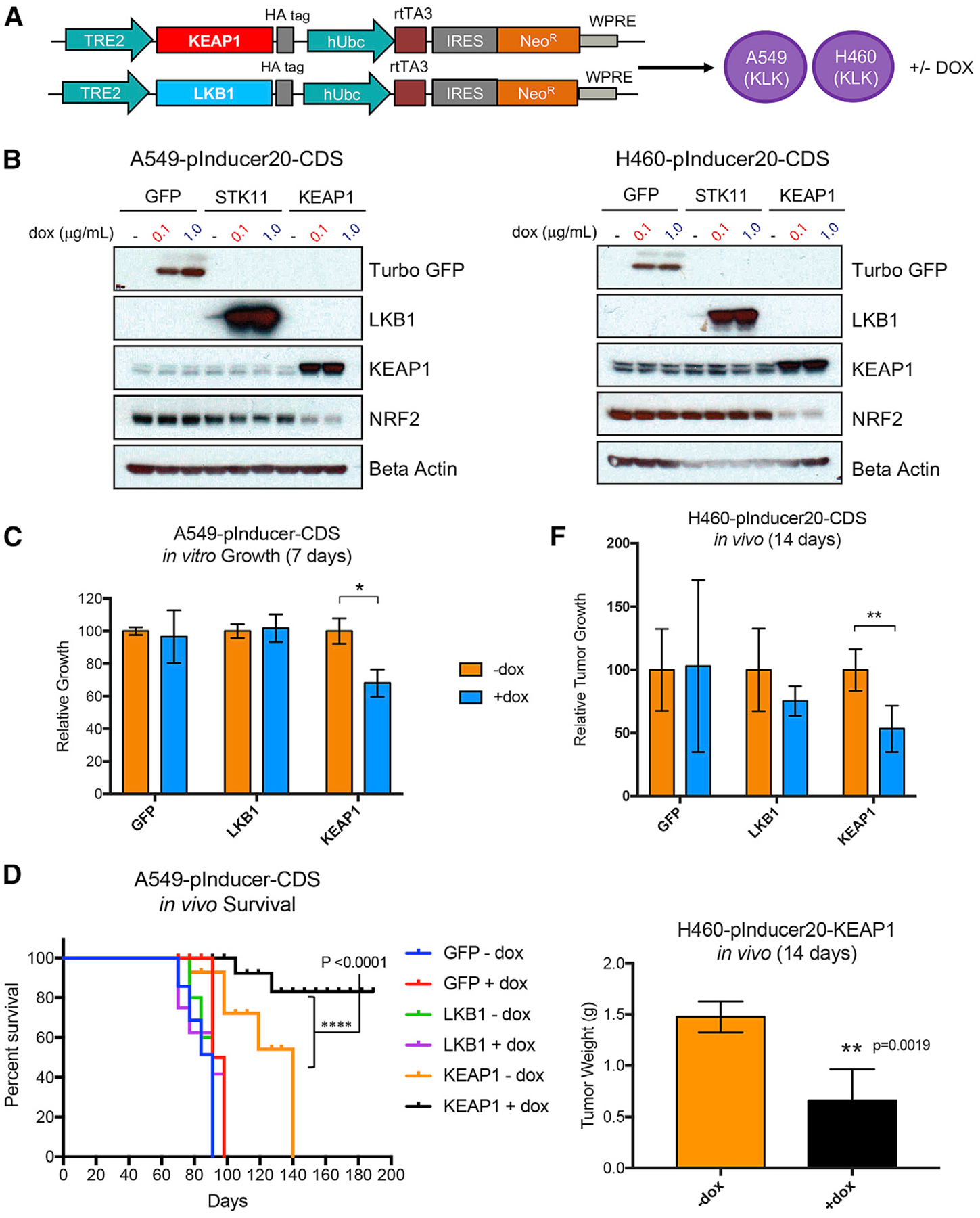

STK11 regulates a family of 12 AMPK-related kinases known to have major roles in diverse cellular functions, including growth, survival, and metabolism (Jeon et al., 2012; Lamming and Sabatini, 2013; Shaw et al., 2004). Although ultimately providing a growth advantage, loss of this master regulator would be predicted to alter cellular homeostasis and require cells to adapt to those new conditions. We hypothesized that concomitant loss of KEAP1 and resultant activation of NRF2-dependent antioxidant signaling could help cancer cells survive and proliferate in the context of STK11 loss. We investigated whether loss of function of both STK11 and KEAP1 augments cancer cell proliferation in vitro and tumor progression in vivo. We transduced A549 and H460 LUAD lines, both harboring de novo STK11 and KEAP1 co-mutations, with doxycycline-inducible lentiviral vectors expressing either WT STK11 (LKB1) or KEAP1 (Figure 3A). Both lines demonstrate tightly regulated, doxycycline-inducible expression of LKB1 or KEAP1 proteins and, consistent with KEAP1 protein function, we observed a decrease in NRF2 upon re-expression of KEAP1 (Figure 3B). We observed a significant decrease (p = 0.012) in A549 cell growth in vitro when KEAP1 protein was re-expressed (A549-KEAP1) (Figure 3C). In vivo, we observed a significant survival advantage (p < 0.0001) in doxycycline-treated mice bearing A549-KEAP1 tumors compared with all other groups: mice with tumors re-expressing KEAP1 survived 40 days longer than the next-longest-surviving group (KEAP1-dox) and approximately 90 days longer than A549-GFP and A549-STK11 mice, with or without doxycycline treatment (Figure 3D). In the H460 xenograft model, we observed significantly smaller tumor volume (p = 0.0028) and weight (p = 0.0019) in doxycycline-treated H460-KEAP1 compared with the untreated control group (Figure 3E). Surprisingly, in these two xenograft models, re-expression of LKB1 did not alter proliferation rate in vitro or tumor growth rate in vivo. These results indicate a requirement for KEAP1 loss of function in STK11/KEAP1 tumors to maintain the cell proliferation rate. This is consistent with recent findings suggesting an “NRF2-addicted” phenotype in KEAP1-mutant LUAD (Kitamura and Motohashi, 2018). STK11 loss of function was not required to maintain proliferative potential of the cells, suggesting that loss of STK11 has a role in tumorigenesis that is distinct from simply maximizing proliferative potential.

Figure 3. KEAP1 Re-expression Disrupts Growth of STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells.

(A) Vector constructs used to transduce A549 and H460 lung adenocarcinoma cells with doxycycline inducible expression vectors for STK11 (LKB1) and KEAP1.

(B) Immunoblot of protein expression in cells transduced with the expression vectors from (A), selected with neomycin, and treated with vehicle or doxycycline at the indicated concentrations for 24 h.

(C) In vitro growth measurements in A549 cells expressing the indicated inducible vector systems treated with vehicle (−dox) or doxycycline at 0.1 μg/mL for 7 days. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

(D) Survival curve of mice bearing A549 tumors containing inducible expression vectors with the indicated gene with or without doxycycline treatment. Survival was measured by time to tumor size of 1,000 mm3.

(E) Relative tumor growth for mice harboring H460 tumors containing inducible expression vectors with the indicated gene. All tumors reached the endpoint of 1,000 mm3 or greater by week 2 (14 days), and all mice were sacrificed on the same day. The weight of H460-KEAP1 tumors treated with vehicle or doxycycline was measure at 14 days (below). Significance was calculated by a two-sample test. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, p < 0.0001. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

The primary known function of KEAP1 is negative regulation of the transcription factor NRF2. To further assess whether the growth advantage conferred by KEAP1 loss was attributable to NRF2 up-regulation, we treated H358-STK11KO cells with Ki-696, an NRF2 activator that increases NRF2 expression by disrupting the protein-protein interaction with KEAP1. The expected increase in NRF2 expression in the treated population was confirmed by western blot (Figure S2A). As predicted, H358-STK11KO cells treated with the NRF2 activator (1 μM, 3 days) grew significantly faster (p = 0.025) than vehicle-treated cells, phenocopying the growth potential of the H358-DKO cells (Figure S2B). Conversely, H358-DKO cells with Cas-9-mediated knockout of NRF2 experienced a decrease in growth rate, as measured by dropout of blue fluorescent protein (BFP), the marker for the single-guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting NRF2, over a period of 20 days (Figures S2C and S2D). Together, these findings confirm that NRF2 activation is primarily responsible for the growth advantage imparted by loss-of-function mutations in KEAP1.

STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Cells Have a Distinct Transcriptional Profile

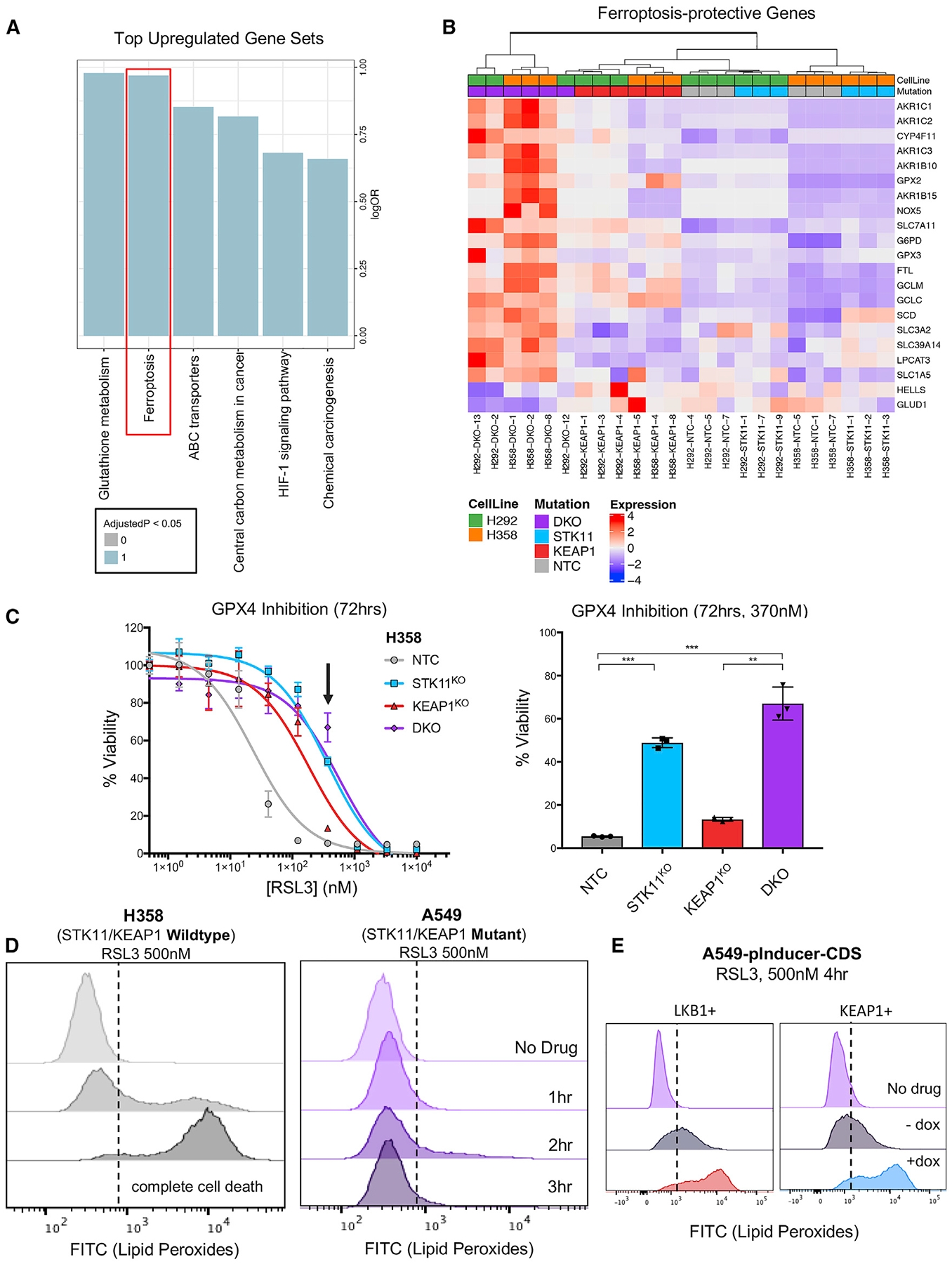

We next investigated how selective mutation in STK11 or KEAP1 alters the transcriptional profile of cancer cells, and how the transcriptional profile of co-mutant cells might uniquely affect cancer-related pathways, including control of proliferative potential, metabolic homeostasis, and cell death. We performed bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on NTC, STK11KO, KEAP1KO, and DKO single-cell clones (n = 3 per group) from both H358 and H292 cell lines. Principal component analysis (PCA) of our clones ordered each clone first by cell line, and later PCs separated clones by mutation status as anticipated (Figure S3A). RNA-seq results identified 1,084 differentially expressed genes in DKO clones compared with all other groups (q value < 0.05) (Table S1). Six pathways were identified as significantly over-represented among upregulated genes (adjusted p value < 0.05), whereas 10 pathways were significantly over-represented among down-regulated genes (adjusted p value < 0.05) (Figures 4A and S3B). Three of six pathways with upregulated genes were related to regulation of cellular metabolism. As an important internal validation of our data, the most significantly enriched of those pathways was glutathione metabolism (adjusted p value = 2.4E–05), consistent with previously published observations made in A549 KRAS/STK11/KEAP1-mutant cells (Galan-Cobo et al., 2019). Genes in that list include GCLM and GSR, two major components of the glutathione metabolism pathway that aid in reduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Interestingly, the second most enriched gene set among upregulated genes in DKO was ferroptosis (adjusted p value = 1.3E–03). Ferroptosis is a non-apoptotic form of cell death, characterized by a failure in glutathione-dependent antioxidant defenses, resulting in unchecked lipid peroxidation and subsequent cell death (Dixon et al., 2012). Ferroptosis can be induced by either impaired elimination or over-production of lipid peroxides leading to accumulation to lethal levels. Our analysis identified a transcriptional profile for STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells, independent of KRAS status, in which glutathione metabolism is upregulated to maintain metabolic homeostasis, and a ferroptosis-protective gene signature is enriched, which may promote cell survival.

Figure 4. Ferroptosis-Protective Genes Are Upregulated in STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutants and STK11 and KEAP1 Mutations Independently Protect Cells from Ferroptosis.

(A) Bar plot of top over-represented Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways among genes upregulated in double-knockout samples, across cell lines. Blue indicates a significant enrichment (q < 0.05).

(B) Heatmap of differentially expressed genes between double-knockout samples versus others that can be found in the KEGG pathway of ferroptosis or have other literature linking them to the pathway. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Manhattan distance and the Ward D method of clustering. Expression shown is a Z score of the normalized transcripts per million (TPM) after removing the effect of cell line.

(C) The dose-response curve of H358 isogenic clones treated with the indicated dose of ferroptosis-inducers RSL3 for 72 h. Arrow indicates the dose depicted in the bar graph. Significance was calculated by a two-sample test between samples at each end of the bracket. A Bonferroni correction was performed across the six tests so that *p < 0.008, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002.

(D) Lipid peroxidation, as measured by a C11-BODIPY probe, in H358 and A549 cells treated with RSL3 with 500 nM for the indicated time periods. A shift to the right indicates an increase in lipid peroxidation.

(E) Lipid peroxidation, as measured by C11-BODIPY probe, in A549 cells with de novo LKB1 and KEAP1 loss-of-function mutation (−dox) or re-expression (+dox) treated with RSL3 for 4 h. A shift to the right indicates an increase in lipid peroxidation and subsequent ferroptosis induction.

STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Cells Have Higher Expression of Genes Involved in Ferroptosis Protection and Are Resistant to Ferroptosis-Inducing Agents

The coordinated induction of an anti-ferroptosis program suggested a possible therapeutic vulnerability in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. We hypothesized that the metabolic shift associated with the loss of STK11 and KEAP1 might lower a cellular threshold to ferroptosis, making those cells dependent on the observed upregulation of anti-ferroptotic factors. To explore that possibility, we investigated how ferroptosis regulators might promote survival of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD when challenged with ferroptosis induction. Notably, NRF2 regulates expression of many genes in the ferroptosis pathway; however, our system differentiates gene-expression changes between KEAP1KO clones and DKO clones. That methodology provides an opportunity for comparison of single-mutant and co-mutant effects and identifies enhanced NRF2 activity in DKO mutants beyond that attributed to KEAP1 mutation alone.

Comparing our DKO clones relative to all other groups, we identified significant upregulation of genes encoding negative regulators of ferroptosis. Those genes include components of the Xc- antiporter SLC7A11 (q value = 0.0058, β = 1.1) and SLC3A2 (q value = 0.011, β = 0.61) and regulators of GPX4-mediated reduction of lipid peroxidation, including members of the glutathione pathway GCLC (q value = 0.0090, b = 0.92), GCLM (q value = 0.031, β = 0.99), and G6PD (q value =0.0042, β = 1.07) (Figures 4B and S4A). Based on the increased expression of ferroptosis-protective genes in DKO clones, we postulated that those cells might be less responsive to known inducers of ferroptosis, including erastin, an inhibitor of the Xc- antiporter, and RSL3, an inhibitor of GPX4. We treated H358 isogenic clones with erastin at a dose of 2 μM for 72 h and observed a decrease in cell viability by 70% in NTC compared with 30% in H358-STK11KO, 40% in H358-KEAP1KO, and 35% in H358-DKO (Figure S4B) (p < 0.001 for comparison of DKO versus NTC). The difference in cell viability among genotypes was not as striking as we anticipated. The target of erastin, the Xc- antiporter, is upstream of the actual mechanism of ferroptosis induction, peroxidation of lipids. When blocking the Xc- antiporter, and therefore, the transport of cystine into the cell, glutathione/glutathione disulfide (GSH/GSSG) redox is inhibited from neutralizing ROS within the cell. High-cellular ROS can activate both ferroptosis and apoptosis cell-death mechanisms. To address whether apoptosis is a contributing cause of cell death via erastin, independent of genotype, we performed a flow cytometry assay for Annexin V/DAPI after treatment with erastin. We observed that H358 cells treated with erastin for up to 72 h do, in fact, induce apoptosis (Figure S4C). In contrast to the upstream mechanism of erastin, RSL3 directly inhibits GPX4, the protein responsible for neutralizing lipid peroxides and, therefore, directly inhibiting ferroptosis. We treated our H358 isogenic clones with RSL3 for 72 h at 370 nM and observed resistance in H358-STK11KO (p < 0.0001) and H358-DKO (p = 0.0002) compared with NTC (Figure 4C). Although it has been reported that KEAP1 loss induces NRF2-regulated expression of genes involved in ferroptosis protection, these data indicate that STK11 loss may have an important role in cell survival by ferroptosis evasion.

To further dissect the mechanism of ferroptosis-protection we identified in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD, we compared the production of lipid peroxides in H358 cells (STK11 and KEAP1 WT) to A549 cells (STK11 and KEAP1 mutant) treated with 500 nM RSL3. H358 cells demonstrated lipid peroxidation after 1 h of RSL3 treatment, and complete cell death by 3 h. In contrast, A549 cells were completely protected from lipid peroxidation for the entire 3-h treatment (Figure 4D). To determine whether STK11 and KEAP1 both have an independent role in ferroptosis protection, we used our A549 model for dox-inducible re-expression of LKB1 or KEAP1. Upon treatment with RSL3 at 500 nM for 4 h, we saw that re-expression of both LKB1 and KEAP1 independently sensitized A549 cells to lipid peroxidation (Figure 4E). Taken together, our findings indicate that STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors develop multi-modal ferroptosis-protective mechanisms, regulated by the loss of both STK11 and KEAP1.

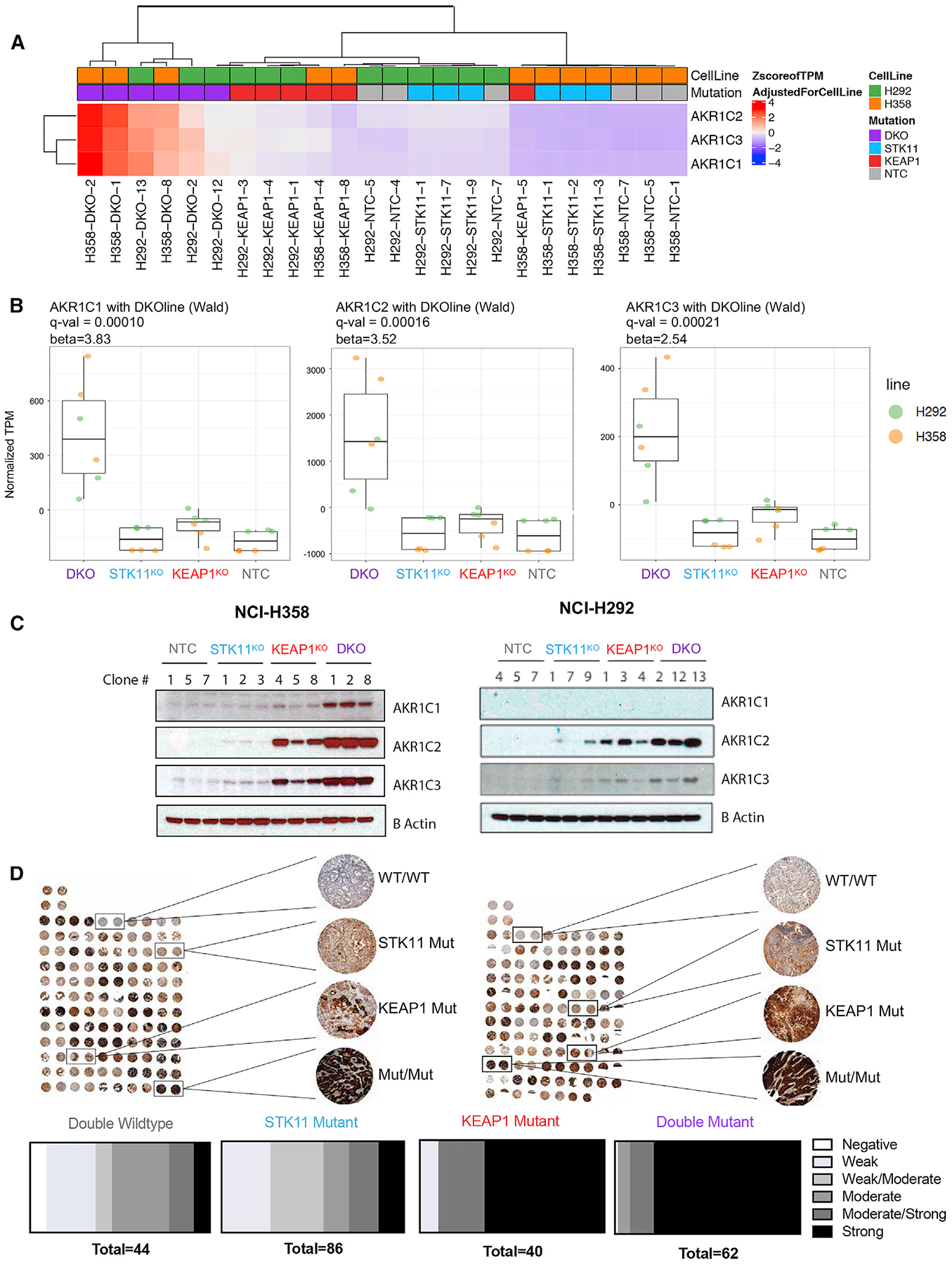

AKR1C Family Genes Are Significantly Upregulated and Aid Ferroptosis Evasion in STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Cells

Among the NRF2-regulated ferroptosis-protective genes, members of the aldo-keto-reductase-1C (AKR1C) family, AKR1C1, AKR1C2, and AKR1C3, were among the top genes upregulated in DKO cells as compared with all other groups (Wald test β = 3.83, 3.52, and 2.54, respectively) (Figures 5A and 5B). These increases in RNA transcript expression correlate with protein expression levels across cell lines (Figure 5C). Notably, protein expression was also partially induced in KEAP1KO lines. The substantial increase in AKR1C expression in DKO versus KEAP1KO supports our finding that NRF2 activity is enhanced in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD beyond that induced by KEAP1 mutation alone. AKR1C members have been shown to promote cell proliferation, metastasis, and chemo-resistance in multiple cancer models (Chang et al., 2019; Tian et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2018) and have been shown to protect melanoma cells from ferroptosis (Gagliardi et al., 2019).

Figure 5. AKR1C Family Is Highly Upregulated in STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutants.

(A) Heatmap of AKR1C expression in isogenic knockout clones from three cell lines. Expression shown is a Z score of the normalized TPM after removing the effect of cell line. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Manhattan distance and the Ward D method of clustering.

(B) Boxplots show normalized TPM (after removing cell line effect) of each AKR1C family member in three isogenic clones with indicated genotype.

(C) Immunoblots of protein expression of AKR1C family members in isogenic clones.

(D) Immunohistochemical staining for AKR1C1 in two independent tumor microarrays containing duplicate patient tumor samples from 60 (TMA1) and 58 (TMA2) patients with lung adenocarcinoma and known STK11 and KEAP1 status. Blind scoring was performed by a pathologist and retrospectively correlated to genotype for each tumor. Damaged samples were not considered in the scoring.

To assess whether the upregulation of AKR1C1 in our KEAP1KO and DKO cells was reflective of STK11/KEAP1 mutational status in patients with LUAD, we stained tissue microarrays containing 119 resected LUADs with an antibody to AKR1C1. We observed the highest expression of AKR1C1 in co-mutant samples with 79% (49/62) of samples with a co-mutation scoring as strong expressors, compared to 65% (26/40) of KEAP1 mutants, 14% (12/86) of STK11 mutants, and 9% (4/44) of double WT samples (Figure 5D). Taken together, RNA and protein expression analyses of our isogenic clones across cell lines, as well as patient data categorized by mutation sub-type, consistently supports the finding that STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors markedly upregulate AKR1C family members.

A challenge in defining a selective therapeutic strategy for ferroptosis induction in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors is to identify a protein target that can be inhibited without substantial toxicity in healthy tissues. Given that the upregulation of AKR family members is specific to STK11/KEAP1 mutants and that these proteins have a known role in ferroptosis protection, we hypothesized that they could represent effective therapeutic targets for this subtype of LUAD. We investigated whether genetic inhibition of AKR1C1 would be selectively effective against co-mutant LUAD. We transduced H358-DKO clones with a lentivirus containing a BFP-marked guide against AKR1C1 and observed a steady decrease in the percentage of BFP+ cells over 20 days, indicating a decrease in the cell growth rate (Figure S5A). Given that a viable population of BFP+ cells was maintained, we concluded that knockout of AKR1C1 alone was not sufficient to decrease the viability of H358-DKO cells. The other AKR1C family members (AKR1C2/3) have substantial redundancy and may compensate for the loss AKR1C1. Therefore, we treated H358 isogenic clones with a titration of medroxyprogesterone 17-acetate (MPA), a weak pan-AKR1C inhibitor, for 3 days. We observed a 35% decrease in cell viability in H358-DKO clones at a high dose of 10 μM MPA, a significantly greater response compared with NTC (p = 0.0056) (Figure S5B). Although MPA selective efficacy is supportive of AKR1C having a role in DKO survival, inhibition of AKR1C members by MPA as a single agent is not a clinically viable strategy because of our inability to reach the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) at a dose as high as 10 μM. Interestingly, the combination of MPA (10 μM) with the ferroptosis-inducer erastin (5 μM) resulted in a 4-fold decrease in cell viability (from ~80% in erastin treated cells to ~20% in cells treated with the combination of erastin and MPA) in H358-DKO cells (Figure S5C). These results support a role for AKR1C family members in protecting STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells from ferroptosis but do not support the pan-AKR1C inhibitor MPA as a therapeutic strategy.

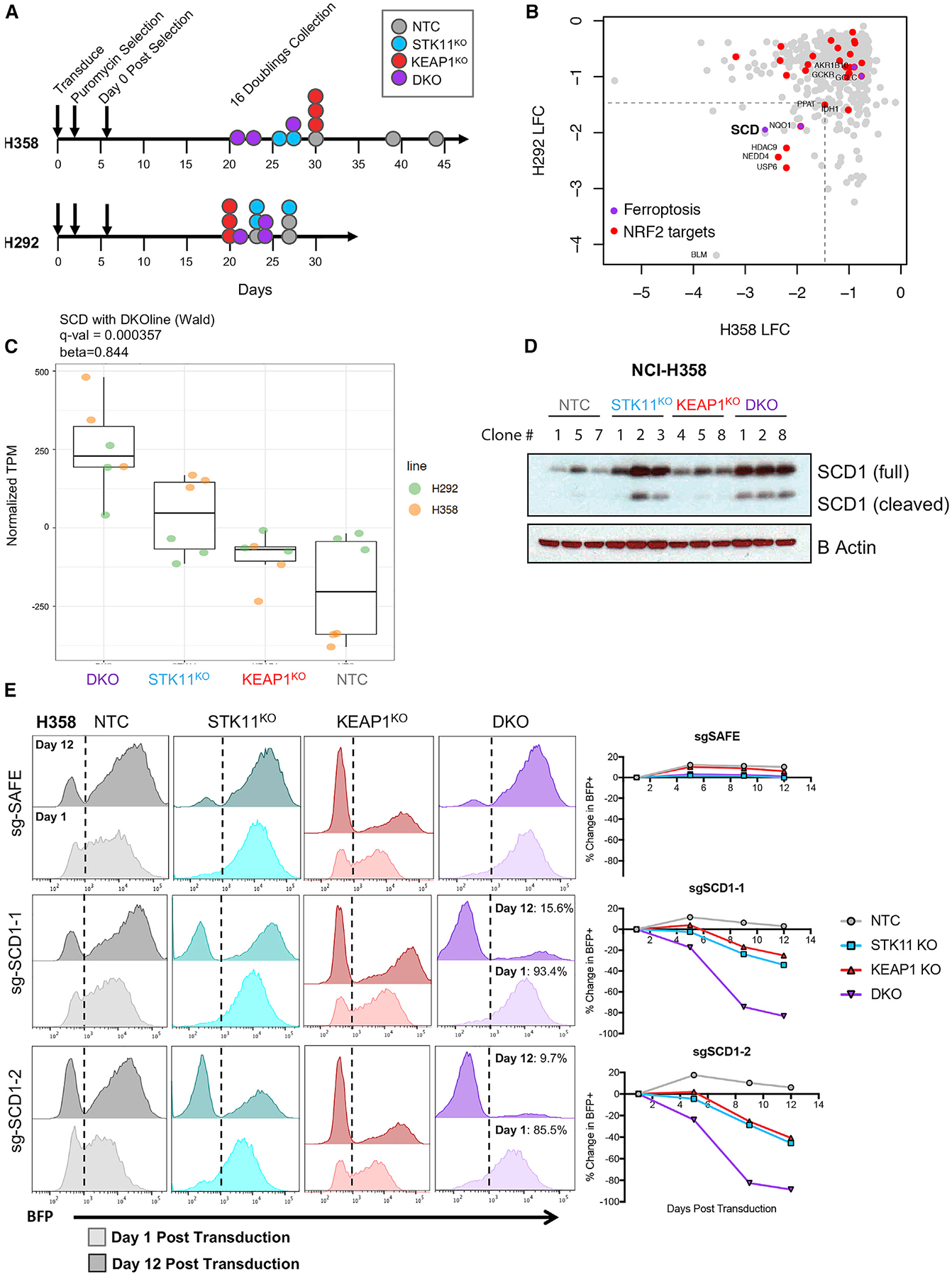

CRISPR/Cas9 Screen Identifies Ferroptosis Regulator SCD as an Essential Gene Required for Proliferation and Survival of STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Cells

To identify genetic vulnerabilities selective for STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors, we performed a CRISPR/Cas9 screen in our isogenic in vitro models. That screen was performed with a curated “druggable genome” sgRNA library that targets 1,463 genes encoding proteins that are direct targets of currently available drugs or are immediately downstream of a directly targetable protein (Table S2). That approach was taken so that any hits identified in the screen as preferentially maladaptive when disrupted in co-mutant clones could be readily targeted with a pharmacologic approach. That strategy increases the translational potential of our findings by providing immediate therapeutic options for this particularly aggressive subset of LUAD.

We performed that screen in our two cell lines, H358 (KRAS mutant) and H292 (KRAS WT) in all four mutant groups (NTC, STK11KO, KEAP1KO, and DKO) and across three isogenic clones per group. Clones were passaged separately throughout the screen and tracked for the number of doublings to control for variation in proliferation rate. Each clone was passaged for 16 doublings (Figure 6A). In agreement with a recent study (Galan-Cobo et al., 2019), we identified glutaminase (GLS) as a top-ranked hit in our H358 screen (KRAS mutant), increasing our confidence in the screen results. We did not, however, identify GLS as a hit in our H292 screen (KRAS WT), supporting the need for investigation of KRAS-independent genetic vulnerabilities in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. We compared the log-fold change (LFC) in hits from the H358 screen to that of the H292 screen to identify shared dependencies (Figure 6B). Notably, although AKR1C1/2/3 guides were in the sgRNA library, those genes were not detected as significant hits in either screen, again consistent with a possible functional redundancy among these family members.

Figure 6. SCD1 Activity Is Essential for Survival of STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Adenocarcinoma.

(A) Schematic indicating the timeline for each CRISPR screen.

(B) Differential sgRNA abundance between NTC and DKO clones was determined using MAGeCK in robust ranking algorithm (RRA) mode. Gene-wise log-fold changes (LFC) are plotted as the means of the statistically significant sgRNAs for each gene. A cutoff of −1.5 LFCs was chosen to identify candidate hits from the two screens. Results from H358 screen are plotted on the x axis and from H292 on the y axis.

(C) Boxplots show normalized TPM (after removing cell line effect) of SCD in three isogenic clones with indicated genotype from two cell lines (H358 and H292).

(D) Immunoblot of protein expression of SCD1 in H358 isogenic clones.

(E) BFP measurements at day 1 after transduction (lighter color) and day 12 after transduction (darker color) in H358 isogenic clones transduced with sgTrack-BFP vector containing the indicated sgRNA. Graphs quantify change in the percentage of BFP in each clone over time.

Two of the top 50 hits in both H358-DKO and H292-DKO compared with their NTC controls have known critical functions in ferroptosis protection, NQO1 and SCD1. NADPH quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) is an NRF2-regulated gene that has a role in quinone and hydroquinone reduction, preventing the production of free radical species. NQO1 has been previously implicated as a potential target for cancer therapeutics (Oh and Park, 2015). SCD/SCD1 is a regulator of lipid composition, which converts saturated fatty acids (SFAs) to monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) (Igal, 2010). MUFAs have been shown to compete with polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) to integrate into the plasma membrane, thereby decreasing the level of PUFAs available for lipid peroxidation and subsequent ferroptosis (Magtanong et al., 2019). SCD was depleted in H358-DKO with a LFC of −2.6 and in H292-DKO with a LFC of −1.9. To assess whether SCD was transcriptionally altered in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutants, we plotted RNA-seq differential-expression effect size (comparing DKO to other groups within the individual cell line) versus CRISPR LFC for H358 and H292 (Figures S6A and S6B). SCD stood out as a gene that is upregulated at the transcript level in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutants, is depleted in a dropout-dependency screen in both H358-DKO and H292-DKO, and has a role in ferroptosis protection. Unlike many of the ferroptosis-protective genes, SCD1 is not known to be regulated by NRF2. Together, these findings indicate that SCD1 may have an essential role in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD, which is distinct from the many NRF2-regulated antioxidant response proteins.

Genetic and Pharmacological Inhibition of SCD1 Prevents the Growth of STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Cells and Sensitizes Those Cells to Ferroptosis Induction

SCD1 has gained recognition in the past decade as a central regulator of cancer metabolism (Igal, 2016) and, more recently, as a protein responsible for protection against ferroptosis (Tesfay et al., 2019). In our RNA-seq dataset, we identified SCD as a top differentially expressed gene in our DKO subgroup compared with all other groups (q value = 3.6E 4, β = 0.84) (Figure 6C). At the protein level, both full-length SCD1 and cleaved SCD1 (Luyimbazi et al., 2010) were upregulated in DKO mutants compared with NTC and KEAP1KO mutants (Figure 6D). Cleaved SCD1 has been noted in the literature, but distinct functions for these two forms have not been reported. Interestingly, SCD1 was upregulated at the protein level in H358-STK11KO mutants compared with NTC as well, suggesting a role for STK11 in regulating SCD1 levels.

To genetically validate the essentiality of SCD1, we transduced our Cas9-containing H358 clones with a BFP-expression vector containing an sgRNA against SCD or a safe-targeting sgRNA as a control. This approach allowed us to track percentage of BFP over time as a marker for SCD1 knockout. Effective knockout of SCD1 was validated by western blot (Figure S6C). BFP expression was tracked over a period of 2 weeks to determine whether cells with knockout of SCD1 could survive in culture. Proliferation and viability of H358-NTC clones were unchanged with SCD1 knockout, confirming that SCD is not an essential gene in all cancer cells. Strikingly, we saw a dropout of ~90% of BFP+ cells in the DKO population over a period of 12 days after transduction (Figure 6E), suggesting that STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells cannot survive if SCD1 expression is lost. We saw ~30%–40% dropout of BFP+ cells in STK11KO and KEAP1KO single mutants suggesting that SCD1 plays an important role in each single mutation but is less essential to survival (Figure 6E). These results confirm that SCD is an essential gene for the survival of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells.

To ensure that this genetic dependency on SCD1 is not specific to our particular DKO cells, we performed a clonal competition experiment, as described in our previous work (Hulton et al., 2020), in A549-pSpectre cells expressing doxycycline-inducible Cas9. Briefly, these cells were transduced with a lentivirus containing either mCherry-sgNTC (non-targeting control) or BFP-sgSCD1. The positively selected populations were mixed 50/50 and treated with or without dox for 17 days. Dox-induced Cas9 was detected by western blot, and SCD1 knockout was confirmed at 10 days after dox treatment (Figure S6D). At 17 days, or 1 week after SCD1 knockout, we observed no change in the mCherry/BFP ratio in the −dox population. In the +dox population, we observed a depletion of BFP+ cells from 50% to 11%, confirming the lethality of SCD1 knockout in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant A549 cells (Figure S6E).

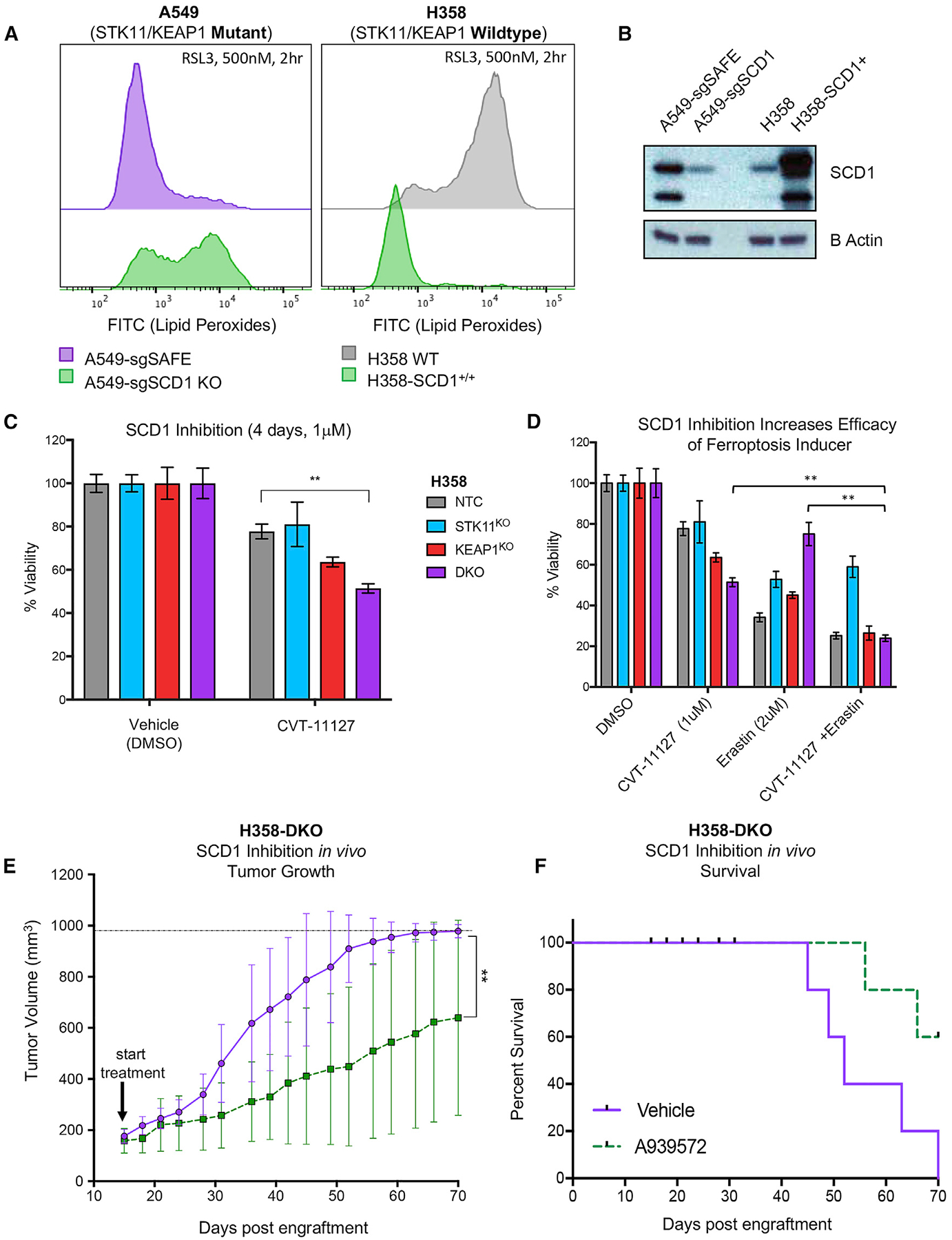

The process of lipid synthesis, storage, and degradation are finely regulated to maintain cellular homeostasis and protect cells from ferroptotic death. SCD1 has been shown to promote ferroptosis protection by promoting MUFA production, thereby regulating the levels of membrane PUFAs available for lipid peroxidation. To determine whether SCD1 expression alters pharmacologically induced lipid peroxidation, we knocked out SCD1 in A549 cells (STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant) and overexpressed SCD1 in H358 cells (STK11 and KEAP1 WT) and treated these cells with 500 nM RSL3 for 2 h. We observed that SCD1 knockout sensitizes A549 cells to RSL3, whereas SCD1 overexpression protects H358 cells from RSL3-induced lipid peroxidation (Figures 7A and 7B). These results validate the ferroptosis-protective mechanism of SCD1 and the specificity of this effect to STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD.

Figure 7. Pharmacologic Inhibition of SCD1 Is Effective in STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutants In Vivo and In Vitro Alone or in Combination with a Ferroptosis Inducer.

(A) Lipid peroxides, as measures by a C11-BODIPY probe, in A549 cells with Cas9-mediated knockout of SCD1 (left) and H358 cells with SCD1 overexpression (right) compared with their wild-type counterparts. A shift to the right indicated an increase in levels of lipid peroxides.

(B) Immunoblot of cell lines from (A) indicating knockout or overexpression of SCD1.

(C) Measurement of the percentage of viable cells comparing isogenic clones from H358 cell line treated with SCD1 inhibitor CVT-11127 at 1 μM for 4 days. Significance was calculated by a two-sample t test between samples at each end of the bracket. A Bonferroni correction was performed across the six drug treatment tests so that *p < 0.008, **p < 0.002, ***p < 0.0002. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

(D) Measurement of the percentage of viable cells comparing isogenic clones from H358 cell line treated with SCD1 inhibitor at 1 μM alone, erastin alone at 2 μM, or a combination of SCD1 inhibitor and erastin for 4 days. Significance was calculated by a two-sample t test in which specific hypotheses were tested for samples in the DKO group where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are represented as means ± SEM.

(E) Tumor volume of H358-DKO tumors treated with vehicle (purple) or 50 mg/kg SCD1 inhibitor A939572 (dotted green). Significance was calculated using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test where *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(F) Survival data of mice from (E) in which survival was denoted as the time from injection of cells to tumor volumes of 1,000 mm3.

To test the effects of SCD1 pharmacological inhibition, we treated H358 isogenic clones with an SCD1 inhibitor (CVT-11127) at 1 μM for 4 days and observed a significant decrease in cell viability in the DKO group compared with NTC (p =0.0004) (Figure 7C). We note that inhibition of SCD1 by CVT-11127 decreased expression of the cleaved form of SCD1 (Figure S7A). To ensure that the response to SCD1 inhibition is not cell line specific, we tested a panel of LUAD cell lines with or without STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation with CVT-11127 at 1 μM for 4 days. Viability of STK11/KEAP1 cell lines was significantly decreased (p < 0.0001) compared with control lines lacking those mutations (Figure S7B). That the pharmacological responses observed with CVT-11127 are not as pronounced as the more dramatic genetic evidence of SCD1 dependence points to the need for more potent and selective SCD1 inhibitors. However, these results agree with and further support out genetic validation of SCD1 as a selective dependency in the context of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD.

We next explored whether pharmacologic SCD1 inhibition could prime STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD for response to other ferroptosis-targeting agents. The combination of CVT-11127 (1μM) with the ferroptosis inducer erastin (2 μM) completely reversed the erastin resistance observed in DKO cells relative to single-mutant or NTC cells, reducing viability in DKO cell from 75% with single-dose erastin to 23% with the combination after 4 days treatment (p < 0.005) (Figure 7D). Interestingly, STK11KO clones did not respond to the combination, suggesting a model of complementary roles: STK11 loss upregulating SCD1 expression, and KEAP1 loss promoting dependence on SCD1 activity, together making co-mutants specifically SCD1 dependent.

Considering that both AKR1C1/2/3 and SCD1 have been implicated in ferroptosis protection, we hypothesized that the combination of MPA and CVT-11127, the small molecule inhibitors of pan-AKR1C and SCD1, respectively, would have a more potent killing effect on STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells compared with either single agent. Supporting this hypothesis, we saw a dose-dependent decrease in the IC50 of CVT-11127 in H358-DKO cells when combined with MPA. The IC50 of CVT-11127 was decreased ~1,000-fold in the presence of 0.1 μM MPA and ~5,000-fold in the presence of 10 μM MPA (Figure S7C). This combination was selectively effective against H358-DKO cells compared with H358-STK11KO, H358-KEAP1KO and H358-NTC cells (Figure S7D). These data suggest that AKR1C family members and SCD1 have complementary roles in maintaining cell survival of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. Optimization of selective combinatorial strategies targeting ferroptosis in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD deserves further investigation.

In Vivo Inhibition of SCD1 Defines a Selective Therapeutic Target in STK11/KEAP1 Co-mutant Adenocarcinoma

To further explore the translational implications of our in vitro findings, we assessed the efficacy of an SCD1 inhibitor in vivo. Given that the SCD1 inhibitor CVT-11127 is not suitable for in vivo experimentation, we chose an alternative SCD1 inhibitor, A939572, which has been formulated for in vivo use. A939572 has demonstrated preclinical efficacy in vivo in various cancer types, including clear cell renal cell carcinoma and EGFR-mutant lung cancer in combination with tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) (von Roemeling et al., 2013; She et al., 2019). We treated mice harboring H358-NTC tumors or H358-DKO tumors with vehicle or A939572 and assessed the tumor growth and overall survival over time (n = 5 per group). Our findings show that the single agent SCD1 inhibitor provides significant selective growth inhibition in H358-DKO tumors (p = 0.008) (Figure 7E), resulting in a survival benefit in this cohort relative to control (Figure 7F). In the H358-NTC model, however, mice treated with A939572 grew similarly to those treated with vehicle control (Figures S7E and S7F).

Taken together, our genetic and pharmacologic data across isogenic cell lines nominate SCD1 as a therapeutic target in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD irrespective of KRAS status. Our findings support the development of potent and specific SCD1 inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy that may be selectively effective in this exceptionally high-risk patient cohort.

DISCUSSION

Targeted therapies for LUAD have been successful in a subset of patients with tumors harboring some single driver mutations, most notably mutations leading to activation of oncogenic kinases. Unfortunately, that approach does not provide a therapeutic strategy for patients whose tumors harbor more-complicated tumor mutation profiles, including concomitant loss-of-function mutations in STK11 and KEAP1. In this study, we used multiple single- and double-gene knockout clones across two independent cell lines to specifically interrogate the differences in gene expression and gene dependency of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD relative to isogenic single-mutant and WT counterparts. We identified a therapeutic vulnerability for this particularly aggressive subtype of lung cancer. Our approach may pave the way for future studies to identify therapeutic strategies for other inadequately treated and genetically defined malignancies.

RNA sequencing identified a transcription profile specific to STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation, independent of KRAS status, in which co-mutants express higher levels of NRF2-regulated genes and upregulate ferroptosis-protective mechanisms. We identified ferroptosis evasion as a particularly enriched pathway in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. These cells upregulate several ferroptosis-protective genes, resulting in resistance to ferroptosis inducers. Multiple genes regulated by NRF2 encode proteins implicated in ferroptosis control, including regulators of glutathione metabolism SLC7A11, GCLC, GCLM, and GSS (Dodson et al., 2019). More notably, we were able to identify an NRF2-driven gene signature in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells that substantially enhances the component of NRF2-regulated transcription beyond that of KEAP1 mutants and, therefore, increases the genetic signatures of glutathione metabolism and ferroptosis protective mechanisms. These results indicate a cooperativity between STK11 and KEAP1 loss-of-function, independent of KRAS mutation status, in which cells augment and become more dependent on certain aspects of NRF2-dependent ferroptosis-protection.

Within this ferroptosis-protective gene list, we identified members of the aldo-keto reducatase-1C (AKR1C) family as having striking increases in transcript and protein expression in vitro, and corresponding increased protein expression in patient tumors harboring STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation. AKRs have a regulatory role in ferroptosis through promoting detoxification of reactive intermediates of aldehyde and ketone agents (Jung et al., 2013). Gene expression of AKR1C members was greater in co-mutant cells compared with KEAP1 mutants alone further supporting the enhanced NRF2-depedence we identified in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutants. Despite the impressive increase in protein expression across this family, our efforts to pharmacologically target AKR1C as a single-agent therapeutic strategy were limited by the potency and selectivity of the available drugs.

We performed CRISPR/Cas9 screens to identify genes that are essential to maintain growth and/or survival of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells. We rationalized that a dropout screen using a curated druggable genome library could uncover selective genetic vulnerabilities in this aggressive form of LUAD that we could then validate with available drugs. Through this approach, we identified SCD1, a master regulator of lipid metabolism and, interestingly, a known regulator of ferroptosis. The transcriptional regulation of SCD1 is not fully understood; however, the promoter region contains transcription factor binding sites for several well-known transcription factors including NF-1, AP-2, SREBP, and PPAR. A number of mitogens have been shown to stimulate SCD1 expression, including epidermal growth factor, retinoic acid, and members of the fibroblast growth factor family (Igal, 2010). In this study, we identified a link between STK11 loss of function and expression of SCD1; STK11 single-mutant cells upregulated SCD1 compared with control cells, and STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant cells upregulated SCD1 to a greater extent. Through both genetic and pharmacologic manipulation, we were able to validate SCD as an essential gene specific to STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant tumors. In addition, we found a strongly synergistic effect when inhibiting both AKR1C and SCD1, two ferroptosis-protective genes primarily affected by KEAP1 loss and STK11 loss, respectively. Taken together, our findings show that in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD, loss of each of these two genes has a distinct and potentially complementary role in promoting ferroptosis evasion allowing cells to survive and persist. Upregulation of this pathway appears to be necessary for maintenance of STK11/KEAP1 co-mutation in this context, as demonstrated by the strong selective lethality of genetically targeting a key regulator node, SCD1.

During the past decade, numerous studies have defined ways in which SCD1 contributes to the progression of cancer through effects on lipid metabolism, cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis (Tracz-Gaszewska and Dobrzyn, 2019). Despite robust pre-clinical findings supporting SCD1 as a therapeutic target for cancer, development of highly potent and specific SCD1 inhibitors has not been a primary therapeutic focus, and clinical deployment of existing SCD1 inhibitors has been limited to the treatment of type 2 diabetes (Zhang et al., 2014). Our study identifies SCD as an essential gene in STK11/KEAP1 co-mutant LUAD. Further studies to design and test targeted SCD1 inhibitors, either alone or in conjunction with agents targeting ferroptosis, represents a promising strategy to improve outcomes in this cohort of patients with limited therapeutic options and poor prognosis.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, CharlesM. Rudin (rudinc@mskcc.org).

Materials Availability

Plasmids, cell lines, and screening libraries generated for this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Data and Code Availability

This study did not generate code. The RNaseq datasets generated during this study are available at ArrayExpress: E-MTAB-9724.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Patients for Survival Analyses

Patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma evaluated at Memorial Sloan Kettering with available MSK-IMPACT data were included in our analysis (Table S5). All patients provided informed consent for genetic profiling of their tumors under an active Institutional Review Board-approved biospecimen protocol. Electronic medical records were used to identify mutation signature and survival outcomes. Mutation cohorts are mutually exclusive, so no one patient is represented in more than one group. Overall survival was defined as the time from date of diagnosis of metastatic disease until death or last follow-up. In patients with more than one tumor biopsy available, we selected for each patient the corresponding biospecimen that was closest to the time of diagnosis of metastatic disease. When a metastatic sample was not available we selected the primary sample that was closest to the date of diagnosis of metastatic disease. The date of biopsy for the sample is the effective time for the genomic landscape. This date may be at a later time than the one of diagnosis, in which case patients would enter the risk set post the date of diagnosis leading to a survival bias. In this dataset, the majority of tumors were biopsied and sequenced within 30 days of diagnosis of metastatic disease. However, a fraction (20%) were sampled and sequenced more than six months from the metastatic recurrence date, with 15% more than a year. We adjusted the late entry by left-truncation to alleviate this “immortal” bias and ensure we are estimating the effective survival time of patients as previously described (Shen et al., 2019).

Patient Samples for LOH and CCF Analyses

The study cohort consisted of tumor samples that contained a mutation in both KEAP1 and STK11. Samples were derived from patients that underwent prospective sequencing as part of their clinical care at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Genomic sequencing was performed on tumor DNA extracted from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue and normal DNA. Genomic sequencing was performed with one of three versions of Memorial Sloan Kettering-Integrated Mutational Profile of Actionable Cancer Targets (MSK-IMPACT) (Cheng et al., 2015). Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions and deletions (Indels) were called using MuTect, Pindel, and Somatic Indel Detector as previously described (Zehir et al., 2017). FACETS (Shen and Seshan, 2016) EM algorithm was used for evaluation of copy number alterations (CNA), including loss of heterozygosity (LOH). The genomic data was frozen on January 17th, 2019.

Cell Culture and Cell Lines

All cell lines were maintained in RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and incubated at 37C with 5% CO2. The following cell lines were used in this study: NCI-H358 (ATCC Cat# CRL-5807, RRID:CVCL_1559), NCI-H292 (ATCC Cat# CRL-1848, RRID:CVCL_0455), NCI-A549 (ATCC Cat# CRM-CCL-185, RRID:CVCL_0023), NCI-H460 (ATCC Cat# HTB-177, RRID:CVCL_0459). Identity of cell lines were confirmed by STR profiling, and all lines tested mycoplasma negative. Isogenic A549 and H460 lines reconstituted with pInducer20-GFP (RRID:Addgene_44012), pInducer20-LKB1 (product of RRID:Addgene_44012 and RRID:Addgene_82320), or pInducer20-KEAP1 (product of RRID:Addgene_44012 and RRID:Addgene_81925) were obtained by lentiviral transduction under Neomycin selection (1000ug/mL). These lentiviral vectors were engineered using a gateway cloning protocol (Gateway LR Clonase II, Invitrogen, cat# 11791–020).

CRISPR/Cas9 Cell Lines

Small guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting human STK11, KEAP1, AKR1C1, NRF2, or SCD1 were selected using the optimized CRISPR design tool GuideScan (www.guidescan.com). Guides with high targeting scores and lowest probability of off target effects were chosen. Three guides per gene were chosen for validation and the most efficient guide, as assessed by protein expression, was used for cell line generation. Guides were cloned into lentiGuide-Puro (RRID:Addgene_52963), sgTrack-GFP (RRID:Addgene_114012), sgTrack-mCherry (RRID:Addgene_114013), or sgTrack-BFP (product of RRID:Addgene_114011 and RRID:Addgene_25891). Cloning was performed using the protocol generated by the Zhang lab (genome-engineering.org, rev20140509): Oligo annealing and cloning into backbone vectors with single-step digestion-ligation.

Generation of Single Cell Isogenic Clones

H358 and H292 NSCLC cell lines were lentivirally transduced with lentiCas9-Blast (RRID:Addgene_52962) and selected with blasticidin (2ug/mL). Upon confirmation of Cas9 expression by western blot H358 and H292 cell lines were transduced with sgTrack-GFP-sgKEAP1, sgTrack-mCherry-sgSTK11, or sgTrack-GFP-sgNTC to create the desired gene knockout using CRISPR/Cas9. Cells containing the fluorescent vector were selected using fluorescence associated cell sorting. Cells were plated into 96 well plates using a limiting dilution method (Sigma) and allowed to grow out from single cell for 1–2 months. Single cell clones were analyzed by western blot for loss of the gene targeted, and by sanger sequencing to identify a single indel or deletion introduced to ensure clonality.

Mouse Models

All animal experiments were approved by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Animal Care and Use Committee. Female nude mice (6–8 weeks old) were obtained from Charles Rivers Laboratories and housed in accredited facilities under pathogen-free conditions. Additional information on experimental methods in next section.

METHOD DETAILS

Lentiviral Production

Lentiviruses were produced using co-transfection of 293T cells with lentiviral backbone constructs and packaging vectors psPAX2 and pMD2.G and using polyethylenimine (PEI). Media was changed 16 hours post transfection and supernatant was collected 72 hours post transfection. Supernatant was concentrated using Lenti-X Concentrator (Fisher Scientific, NC0448638) and centrifugation. Viruses were resuspended in 1mL DMEM media and stored at −80C.

Lentiviral Transduction

Cells were plated in 10cm dishes at 1E6 cells/dish on day 0 and allowed to attach to the plate overnight. On day 1, media was aspirated from cell plates and replaced with 10mL of fresh RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS and 8ug/mL polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich, H9268). Concentrated lentivirus was quick-thawed in a 37C water bath and returned to ice. Lentivirus was added to cells in a drop-wise manner in a volume determined by viral titration, and cell plates were incubated overnight at 37C. On day 2, lentiviral media was aspirated from cell plates and replaced with fresh RPMI with 10% FBS. Cell selection began on day 3, where applicable.

Immunoblots

Whole cell lysates were prepared from frozen cell pellets or flash frozen tumor samples using RIPA lysis buffer supplemented with 1× HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Pierce, Thermo Fisher). Cell pellets were resuspended in 5 volumes of cold lysis buffer and incubated on ice for 15 minutes followed by sonication for 10 s with a 200V microtip sonicator set to 40% amplitude. Lysates were quantified and normalized using a BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Thermo Fisher). Samples were denatured at 75C for 10 minutes in NuPAGE LDS sample buffer with NuPAGE sample reducing agent. 15uL of total protein was loaded and resolved on a precast 4%–12% Bis-Tris Gel (NuPAGE, Invitrogen). Gels were wet-transferred to a 0.45μM Immobilin-P PVDF membrane (Millipore) for chemiluminescent detection. Films were incubated at room temperature in TBS (Fisher) supplemented with 0.1% Tween20 (Fisher) and 5% non-fat dry milk for blocking. Blots were then incubated overnight at 4C with primary antibody diluted in TBS (Fisher) supplemented with 0.1% Tween20 (TBS-T) (Fisher) and 5% BSA (Cell Signaling). Blots were then washed with TBS-T 3× and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour with the relevant secondary antibody diluted in TBS-T and 5% non-fat dry milk. Blots were detected using ECL Western Blotting Substrate (Pierce).

In Vitro Growth Assay

100,000 H358 or 30,000 H292 cells harboring one of the targeted mutations (STK11 loss, KEAP1 loss, both, or neither) were plated in two identical 12 well plates with one clone per well on day 0 in full growth media. The cells were allowed to attach to the plate overnight. On day 1 (after attachment), cells in one plate were fixed and stained using a solution of 0.5% crystal violet, 1% Methanol, and 1% Formaldehyde in PBS. The solution was left on cells for 15 minutes, and the fixed cells were washed 3× with water. On day 3 (48 hours after attachment), the cells from the second plate were fixed and stained using the same protocol. Photos were taken of both plates. Cells were resuspended in 200uL of 20% acetic acid solution and absorbance was measured at 500nm on a plate reader. Relative absorbance was calculated by dividing absorbance on day 3 to absorbance on day 1. Fold change indicates the change in absorbance over the 2-day period. Each clone was measured independently and graphed on the same axis to give an overall calculation of cell growth by genotype in three independent clones per group.

Cell Viability Assays

3000 cells per well of the indicated genotype were plated in 96 well plates in triplicate for each drug dose. Cells were allowed to attach to the plate overnight in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS. Drug titrations were performed in full serum media in a separate 96 well plate with column 11 containing the highest dose of the drug, column 3 containing the lowest dose of the drug, and column 2 containing no drug. Outside wells were filled with PBS to avoid liquid precipitation. Drug concentrations are indicated for each drug in dose/response curves. After cells were allowed to attached to the plate overnight, media was aspirated using a multi-channel aspirator, and replaced with drug media from the drug titration plates. Cells were inclubated at 37 degrees for 3–4 days as indicated. On the final day of drug treatment, media was once again aspirated using a multi-channel aspirator. Cells were washed 1× with PBS then fixed to the plate and stained with a solution of 0.5% crystal violet, 1% Methanol, and 1% Formaldehyde in PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature. After fixing and staining cells, plates were washed in water until no remaining stain was present. Plates were allowed to dry overnight. Fixed and stained cells were resuspended in 50uL of 20% acetic acid solution and absorbance was measured at 500nm on a plate reader. Cell count in each well was calculated using a standard curve of cell count versus absorbance. Cell viability was calculated by dividing cell count of drug treated cells in each well by the average cell count of untreated control cells. Percent viability indicates the change in cell number in each well compared to the control wells over the treatment period.

RNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Analysis

RNA extraction and sequencing was done in collaboration with Genewiz. Total RNA was extracted from fresh frozen cell pellet samples using QIAGEN RNeasy Plus Universal mini kit following manufacturer’s instructions (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). Extracted RNA samples were quantified using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and RNA integrity was checked using Agilent TapeStation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA).

RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina following manufacturer’s instructions (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). Briefly, mRNAs were first enriched with Oligo(dT) beads. Enriched mRNAs were fragmented for 15 minutes at 94C. First strand and second strand cDNAs were subsequently synthesized. cDNA fragments were end repaired and adenylated at 3′ends, and universal adapters were ligated to cDNA fragments, followed by index addition and library enrichment by limited-cycle PCR. The sequencing libraries were validated on the Agilent TapeStation (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as well as by quantitative PCR (KAPA Biosystems, Wilmington, MA, USA).

The sequencing libraries were clustered on 2 lanes of a flowcell. After clustering, the flowcell was loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument (4000 or equivalent) according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2×150bp Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software (HCS). Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina HiSeq was converted into fastq files and de-multiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq 2.17 software. One mismatch was allowed for index sequence identification.

Tumor Micro Array Construction

Lung adenocarcinoma TMAs were created in the MSKCC Pathology Core Lab, Precision Pathology Biobanking Center (PPBC) using the fully automated TMA Grand Master™ (3D Histech, Hungary) and TMA Control software (Version 2.4). The H&E slides of LUAD were reviewed by an attending thoracic pathologist (D.B. and N.R.) for selection of the most representative donor blocks. The areas to be punched for TMA construct were circled and matched with the corresponding donor blocks. A custom TMA layout was designed using the TMA Control software to accommodate 10× 15 1.0mm cores. Additionally, 4× 1.0mm cores of normal tissue were used as markers for the ease of orientation. TMAs were constructed utilizing the diagnostic blocks of LUAD from the archives of the Department of Pathology, MSKCC.

Measuring Lipid Peroxide Levels

In a 10cm dish, 500,000 cells per dish were seeded and allowed to attach overnight. Cells were then treated with media containing the indicated dose of drug or equivalent dose of DMSO vehicle and returned to incubation at 37C. After the indicated time, drug media was supplemented with 2μM of C11-BODIPY 581/591 Lipid Peroxidation Sensor (Invitrogen, D3861) and incubated for another 20 minutes at 37C. Cells were then washed with PBS, harvested by trypsinization, and washed again with PBS. Cells were resuspended in FACS buffer at 500uL and analyzed by flow cytometry using a Fortessa Flow Cytometer. An unstained control population was used to fate for FITC negative cells. Mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells treated with RSL3 for 3 hours were used as a positive control to gate for FITC positive cells induced by RSL3 treatment. Vehicle treated cells were compared to drug treated cells with a shift in the FITC curve to the right indicating an increase in lipid peroxidation.

Annexin V/DAPI Apoptosis Assay

100,000 H358 cells were plated in a 12 well plate in RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS and allowed to attach to the plate overnight. On day 1 after attachment, media was aspirated from on well of the plate and replaced with media containing 20uM of erastin for the 72 hour time point. This was repeated on day 2 and day 3 for the 48hr and 24hr time points respectively. Two wells remained in erastin-free media to act as the negative control (no drug) and FACS minus one control (no stain). On day 4 following the treatment time course, cells were trypsonized from the plate and washed 2× in cold PBS followed by 1× wash in cold Annexin V binding buffer (BD, 556454). Cells were resuspended in 100uL of Annexin V binding buffer supplemented with 4uL of Annexin V-APC (BioLegend, 640920) and incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes in the dark. After incubation, 200uL of Annexin V binding buffer supplemented with 1× DAPI (Thermo Fischer, D1306) was added to each sample. Samples were analyzed on a Fortessa Flow Cytometer using negative controls for gating negative and negative APC and DAPI. A549 cells treated with 1uM staurosporine for 5 hours were used as a positive control to gate Annexin V and DAPI positive cells. Histograms of flow cytometry results were made using the FlowJo software.

BFP Tracking for sgRNA Expression Changes

H358 isogenic clones (NTC, STK11KO, KEAP1KO, DKO) were plated in 10cm dishes at 1E6 cells/dish and allowed to attach to the plate overnight. After cell attachment, cells were transduced with a lentiviral vector containing BFP and a targeted sgRNA (as indicated) at an MOI of 2.0 (80%–90% infection). Transductions were performed as outlined in the section “Lentiviral Transductions.” One day post transduction, media was changed in each plate with fresh RPMI media supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were incubated for an additional 24 hours to allow for expression of BFP and the targeting sgRNA. Cells were then trypsinized and split into new 10cm dishes to remain in culture. A small portion of each transduced cell population was prepared for flow cytometry to assess starting expression of BFP. Cells used for flow cytometry were washed 3× in FACS Buffer (2% FBS, 1% Pen/Strep, 0.02% EDTA in PBS) and analyzed on a Fortessa flow cytometer. During each split of the cell populations (day 5, 9, 12 post transduction) cells were prepared for flow to assess expression of BFP within the population indicating expression of the targeted sgRNA. Percent change in BFP was measured over time using the equation %Change in BFP = ((%BFP on day(n) − %BFP on day 1)/%BFP on day 1)*100. Graphs of flow cytometry histograms were created using FlowJo software.

CRISPR Screen Process and Sequencing

Cells were transduced with the Saturn V library 1 and 2 (Table S2) on day 0, put on puromycin selection on day 3, and collected after 4 days puro selection on day 7 post transduction. This first collection was considered day 0 post selection and acted as the day 0 time point for all analyses. Cells were counted biweekly and passaged separately. When a clone reached 16 doublings, cells were cryo-preserved and used as the endpoint sample for analysis. Sequencing libraries were assessed using the Agilent Tapestation 4200 (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and quantified by using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) as well as by quantitative PCR (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The sequencing libraries were clustered on 1 lane of a flow cell and loaded on the Illumina HiSeq instrument according to manufacturer’s instructions. The samples were sequenced using a 2×150 Paired End (PE) configuration. Image analysis and base calling were conducted by the HiSeq Control Software (HCS). Raw sequence data (.bcl files) generated from Illumina HiSeq was converted into FASTQ files and de-multiplexed using Illumina’s bcl2fastq 2.17 software. One mis-match was allowed for index sequence identification.

STK11/KEAP1 Gain of Function Animal Studies

Mice in the +dox groups were fed a diet of doxycycline chow 3 days prior to injecting cells and throughout the remainder of the experiment. Mice in the -dox group were fed a diet of amoxicillin chow to avoid skin rash. Subcutaneous flank tumors were generated by injecting 5E6 A549 or 2E6 H460 confluent cells (n = 5 per group) suspended in 50% Matrigel into the right flank. Tumor dimensions were taken by caliper once weekly and tumor volume was calculated using the equation V = π/6*L*W2 (L length; W width). For A549, overall survival was denoted by time from injection to tumor volume of 1000mm3 or greater. H460 tumors grew to greater than 1000mm3 over a period of 2 weeks, requiring all mice to be sacrificed at the 2-week measurement. Tumor weights were measured on a scale.

SCD1 Inhibition In Vivo

Subcutaneous single flank tumors were generated by injecting 2.5E6 H358-NTC or 2.5E6 H358-DKO cells suspended in 50% Matrigel into the right flank of each mouse (n = 10 per group). Tumor dimensions were taken by caliper twice weekly and tumor volume was calculated using the equation V = π/6*L*W2 (L length; W width). When tumors reached 100mm3, mice were randomized within each genotype group and placed into subgroups for vehicle treatment (n = 5) and A939572 treatment (n = 5). The vehicle for this experiment was a solution of 10% DMSO, 40% PEG300, 5% Tween-80, and 45% Saline. A939572 (MedChem Express, HY-50709) was given at a dose of 50mg/kg P.O, QDx5 and vehicle treatment was given at equal volume. Survival was denoted by time from injection to tumor volume of 1000mm3 or greater.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATITICAL ANALYSIS

Loss of Heterozygosity and Cancer Cell Fraction Genomic Analyses

292 samples from 276 patients with cancer type of non-small cell lung cancer or lung adenocarcinoma in cBioPortal (Cerami et al., 2012) have mutations in both KEAP1 and STK11 and FACETS fits (meaning that both the tumor and normal were sequenced and neither sample was contaminated). The cancer cell fractions for STK11 and KEAP1 are plotted in Figure S1B.

In order to compare frequency of LOH across genotypes, we focused on 3,399 non-small cell lung or lung adenocarcinoma patients in cBioPortal that had a single segment covering both KEAP1 and STK11 on chromosome 19. Because there is only one segment we could identify the copy number state. We consider LOH any region where the lower copy number is zero. We then compared the frequency of LOH status among different mutational profiles in Figure S1C.

Immunohistochemistry and TMA Scoring

Immunohistochemistry was performed on BOND RX using the bond polymer detection kit (Leica, DS9800). Manufacturer’s standard protocol was implemented using 30 minutes of heat induced epitope retrieval with ER2 buffer and 30 minute incubation of primary antibody at 1:200 dilution.

TMA slides of LUAD containing a total of 119 cores stained with AKR1C1 were evaluated by a pathologist (U.K.B). TMAs were analyzed under the microscope and the results entered on a grid corresponding to the TMA. Each core was examined individually both under low and intermediate magnification (10× & 20×). The positive and negative controls were examined before the analysis of TMAs. The intensity of staining was graded as follows: No staining (0), Weak positive (+), Weak/Moderate (+/++), Moderate positive (++), Moderate/Strong (++/+++), and Strong positive (+++). Samples denoted Weak/Moderate or Moderate/Strong express a variable intensity across the tumor sample.

RNA-sequencing Differential Expression Analysis

RNA expression was calculated using Kallisto (v.0.46.0) (Bray et al., 2016) with Ensembl GRCh37, release 75. Differential expression was performed using Sleuth (v0.30.0) (Pimentel et al., 2017). Sleuth was used to plot PCA and the percentage of variance explained based on Transcripts Per Million (TPM) using the functions “plot_pca” and “plot_pc_variance” in Figure S4A. Heatmaps of gene expression show the Z-score of TPM after removal of the cell line effect. Cell line effect was removed by subtracting the average expression of each cell line for each gene.

Differentially expressed genes between double knockout samples and the other samples (including single mutants and samples wild-type for KEAP1 and STK11) across the three cell lines were identified using the following model: Expression ~CellLine + MutationStatus. This was followed by a Wald test, testing the effect of MutationStatus where MutationStatus is 1 or 0 for double knockout samples and not, respectively. A q-value cut-off of 0.05 was used to identify 1084 differentially expressed genes. Differential expression was also calculated per cell line in order to use the betas for comparison with the CRISPR study in Figure S7. The Wald test was carried out with the following model: Expression ~MutationStatus. MutationStatus is a 1 or 0 to denote double knock-out status in samples versus not.

Pathway enrichment was performed comparing to pathways found in KEGG_2019_Human using R Library enrichR (v2.1). Pathways were considered enriched if adjusted p value < 0.05. The drawing of the ferroptosis pathway in Figure S5 was designed following the KEGG Pathway from 4/12/2019 from Kanehisa Laboratories with additions of some genes (NFE2L2, AKR1C1, AKR1C2, AKR1C3, SCD) and fatty acids SFA and MUFA based on literature search.

CRISPR Screen Bioinformatics

Differential sgRNA abundance was determined using MAGeCK (Li et al., 2014) in Robust Ranking Algorithm (RRA) mode (Tables S3 and S4) (Li et al., 2014). Safe-targeting sgRNAs were used as a controls for library size normalization and differential abundance testing (Morgens et al., 2017). Genewise log fold changes are plotted as the mean of the statistically significant sgRNAs for each gene. Genes were ranked by mean log fold change (LFC) in sgRNA abundance for all statistically differentially abundant sgRNAs (p < 0.05) between NTC and DKO groups.

Statisical Analysis for In Vitro Cell Line Assays

In all experiments where two conditions are being tested, a Student t test was used where p < 0.05 was considered significant, as in Figure 3C. In all experiments where multiple conditions were being tested, a Bonferroni correction was performed to create an adjusted p value suitable for multiple comparison testing. For example, in Figure 2C, the number of tests is equal to 6, and therefore the a result is considered significant if p < 0.05/6 or p < 0.008. In all in vitro experiments, significance was calculated using a two-sample t test comparing the two samples denoted by brackets.

Statisical Analysis for In Vivo SCD1 Inhibition Assay

For in vivo experiments in Figures 7E and S7E, significance was established using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test where *p <0.05, **p < 0.01.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| AbFlex Anti-Cas9 | Active Motif | Active Motif Cat# 91123; RRID:AB_2793783 |

| Anti-TurboGFP | Invitrogen | Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# PA5–22688; RRID:AB_2540616 |

| Anti-LKB1 (D60C5) | Cell Signaling | Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 3047; RRID:AB_2198327 |

| Anti-KEAP1 (P586) | Cell Signaling | Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 4678; RRID:AB_10548196 |

| Anti-NRF2 | AB Clonal | ABclonal Cat# A11159; RRID:AB_2758436 |

| Anti-Beta Actin | Cell Signaling | Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 4967; RRID:AB_330288 |

| Anti-AKR1C1 | Abcam | Abcam Cat# ab183078 |

| Anti-AKR1C2 | Cell Signaling | Cell Signaling Technology Cat# 13035; RRID:AB_2798094 |

| Anti-AKR1C3 | Abcam | Abcam Cat# ab84327; RRID:AB_1859768 |

| Anti-SCD1 | Invitrogen | Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat# PA5–19682; RRID:AB_10982251 |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| Erastin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E7781 |

| RSL3 | Selleck Chemicals | Cat# S8155 |

| KI-696 | MedKoo | Cat# 407974 |

| Medroxyprogesterone 17-acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# M1629 |

| CVT-11127 | Aobious | Cat# AOB2425 |

| A939572 | MedChem Express | Cat# HY-50709 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| Crystal Violet | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# C6158 |

| BODIPY 581/591 C11 | Invitrogen | Cat# C3861 |

| Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher | Cat# 23227 |

| NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris Protein Gels | Thermo Fisher | Cat# NP0322 |