Abstract

Objective

To assess the effectiveness of corticosteroids on outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia requiring oxygen without mechanical ventilation.

Methods

We used routine care data from 51 hospitals in France and Luxembourg to assess the effectiveness of corticosteroids at 0.8 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone (CTC group) versus standard of care (no-CTC group) among adults 18–80 years old with confirmed COVID-19 pneumonia requiring oxygen without mechanical ventilation. The primary outcome was intubation or death by day 28. In our main analysis, characteristics of patients at baseline (i.e. time when patients met all inclusion criteria) were balanced by using propensity-score inverse probability of treatment weighting.

Results

Among the 891 patients included in the analysis, 203 were assigned to the CTC group. Use of corticosteroids was not significantly associated with risk of intubation or death by day 28 (weighted hazard ratio (wHR) 0.92, 95%CI 0.61–1.39) nor cumulative death rate (wHR 1.03, 95%CI 0.54–1.98). However, use of corticosteroids was associated with reduced risk of intubation or death by day 28 in the prespecified subgroups of patients requiring oxygen ≥3 L/min (wHR 0.50, 95%CI 0.30–0.85) or C-reactive protein level ≥100 mg/L (wHR 0.44, 95%CI 0.23–0.85). The number of hyperglycaemia events was higher for patients with corticosteroids than for those without, but the number of infections was similar.

Conclusions

We found no association between the use of corticosteroids and intubation or death in the broad population of patients 18–80 years old, with COVID-19, hospitalized in settings non intensive care units. However, the treatment was associated with a reduced risk of intubation or death for patients with ≥3 L/min oxygen or C-reactive protein level ≥100 mg/L at baseline. Further research is needed to confirm the right timing for corticosteroids in patients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen only.

Keywords: Causal inference, Corticosteroids, COVID-19, Observational study, Therapeutic evaluation

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia is associated with a hyper-inflammatory phase, which is deemed responsible for the clinical worsening of patients [1]. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, guidance regarding corticosteroids for patients without acute respiratory distress syndrome was mixed [2]. Only evidence from small observational studies, with contrasting results, was available, and practices varied widely across the world [[3], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8]].

In July 2020, the RECOVERY trial showed that dexamethasone reduced 28-day mortality for patients receiving oxygen with and without invasive mechanical ventilation [9]. The efficacy of corticosteroids in critically ill patients was confirmed in subsequent trials and in a meta-analysis [[10], [11], [12]]. However, for patients with less severe disease, the trial highlighted heterogeneity of the treatment effect, with a lower incidence of death among patients receiving oxygen but not among those without oxygen at randomization. We hypothesize that this relationship is a continuum, and that the more severe the disease the more effective the treatment. Differences in severity at baseline among the broad population of patients receiving oxygen only could explain the discordance between studies investigating the use of corticosteroids for COVID-19 [[13], [14], [15], [16]].

Our aim was to bring additional data to better understand the effectiveness of corticosteroids in COVID-19 pneumonia, exploring a potential heterogeneity of the treatment effect in the broad population of patients with COVID-19 receiving oxygen without mechanical ventilation.

Methods

We retrospectively used data collected from routine care to emulate a target trial aimed at assessing the efficacy and safety of corticosteroids in patients hospitalized with COVID-19, requiring oxygen and with an inflammatory syndrome [17].

Setting

Our study involved the internal medicine or infectious disease wards from 51 hospitals in France and Luxembourg, part of a network coordinated by REACTing (INSERM).

Study population

Physicians performed a patient-by-patient screening of all patients hospitalized between 1st March and 1st May 2020. First, they identified all consecutive patients aged 18–80 years who had PCR-confirmed severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections. Second, they assessed whether these patients had an inflammatory syndrome with C-reactive protein (CRP) level ≥40 mg/L and required oxygen by mask or nasal prongs during hospitalization. Third, they excluded (a) patients discharged from the intensive care unit (ICU) to standard care or requiring immediate admission to the ICU (including patients requiring non-invasive ventilation); (b) patients with a contraindication to corticosteroids; (c) patients who received corticosteroids or anti-interleukin agents before baseline; (d) patients with severe comorbidities (body mass index <16 kg/m2, renal diseases requiring dialysis, chronic heart failure New York Heart Association grade IV, liver cirrhosis Child grade C, or long-term oxygen therapy); (e) patients with a decision to limit active treatments before baseline; and (f) patients included in the DISCOVERY trial (NCT04315948).

The study received approval by the IRB of the Henri-Mondor Hospital (AP-HP), France (no. 00011558) and by the national ethics committee of Luxembourg (no. 0620-101). The study was based on data from routine care already collected at the time of the study. All patients were informed that their hospital data would be used for research purposes and could refuse this use.

Treatment strategies

We compared two treatment strategies: receiving at least one dose of corticosteroids at ≥0.8 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone or ≥0.4 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone if co-administered with lopinavir–ritonavir (CTC group) versus the standard of care (no-CTC group). These values were chosen to account for dose rounding by the physician and for the drug–drug interaction between ritonavir and steroids (i.e. patients receiving lopinavir–ritonavir require a lower dose of corticosteroids to obtain an effect) [18]. Standard of care consisted of supportive therapy and treatment of the symptoms to prevent respiratory failure. No systematic antibiotic prophylaxis or antiviral agents were provided to patients in the study centres. Patients in the CTC group could start corticosteroids within a prespecified ‘grace period’ of 5 days after baseline [17].

Our causal contrast of interest was the per-protocol effect; thus, patients receiving a lower dose of corticosteroids or starting corticosteroids after 5 days were dropped from the analysis. A specific sensitivity analysis mimicking an intention-to-treat analysis was performed in which all patients eligible for the study were analysed. For safety outcomes, all patients who received corticosteroids, whatever the dose and timing, were considered in the CTC group. The definition of group assignment based on patients' observational data is reported in Supplementary Material 1.

Start and end of follow-up

The start of follow-up (baseline or time zero) for each individual was the time when all eligibility criteria were checked. All patients were followed up from baseline until the occurrence of one of the following: (a) death, (b) loss to follow-up, or (c) end of follow-up, which occurred at least 28 days after baseline.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was intubation or death by day 28. Secondary outcomes were death from any cause by day 28, weaning from oxygen on day 28, and discharge from hospital to home/rehabilitation on day 28. All adverse events (e.g. infection, thromboembolic events, etc.) were abstracted from electronic health records in free text and independently re-coded by four physicians (XL, FG, TP and MM). In case of disagreement, consensus was obtained.

Statistical analysis

A non-parsimonious multivariable logistic regression model was constructed to estimate the probability of receiving corticosteroids given baseline covariates (i.e. the propensity score, PS). Variables of the PS model were prespecified before any outcome analyses and are detailed in Supplementary Material 2. Standardized differences were examined to assess balance, with a threshold of 10% to indicate clinically meaningful imbalance [19].

Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) was used to balance the two groups on potential confounders at baseline. Stabilized weights were used to reduce the variability of weights and standard errors of estimated treatment effects [20]. Cox proportional hazards models were used to compute IPTW hazard ratios (wHRs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). IPTW estimates of the relative risk (wRR) were computed for binary outcomes.

Outcomes are presented for the total population and for predefined subgroups: those with ≥3 L/min oxygen [21], CRP level ≥100 mg/L [22], and a high dose of corticosteroids (≥120 mg) at baseline [23]. We also performed two post-hoc subgroup analyses exploring the treatment effect by time since symptom onset ≤7 or >7 days [9] and among patients with both ≥3 L/min oxygen and CRP level ≥100 mg/L at baseline. In each subgroup, we recalculated the PS to balance the differences in baseline variables between treatment groups.

To account for immortal time bias, all patients in the no-CTC group who met the primary outcome (intubation or death) during the grace period were randomly assigned to one of the two groups, given that their observational data were compatible with both groups at the time of the event [17] (Supplementary Material 3).

We aimed for the maximal sample size achievable while accounting for logistical feasibility and costs. We supplemented our results with an a posteriori power calculation with an α risk of 0.05, based on the number of events observed in our data [24,25].

Missing baseline and outcome variables were handled by multiple imputations by chained equations by using the other variables available. All statistical analyses were performed with R v3.6.1 or later (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

Patients and baseline characteristics

Among the 965 patients eligible for analysis, 194 received corticosteroids at ≥0.8 mg/kg/d eq. prednisone (or 0.4 mg/kg/d eq. prednisone if co-administered with lopinavir–ritonavir) within 5 days from baseline; 697 did not receive corticosteroids, 28 received corticosteroids at a lower dose, and 46 received corticosteroids after 5 days from baseline.

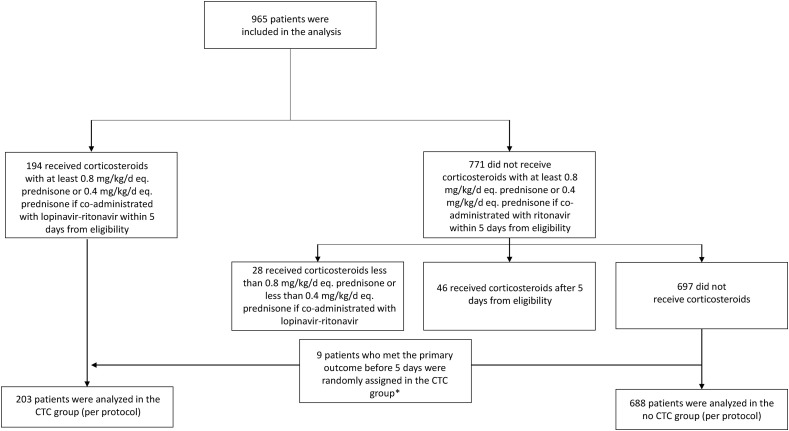

In all, 107 patients who did not receive corticosteroids met the primary outcome (intubation or death) during the grace period. To account for immortal time bias, we randomly assigned these 107 patients to the CTC or no-CTC group [17]. Thus, we compared 203 participants in the CTC group to 688 in the no-CTC group (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Material 3).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart. To account for immortal time bias, we randomly assigned patients who met the primary outcome during the grace period between the corticosteroid (CTC) and no-CTC groups.

The patients' median age was 63 years (interquartile range (IQR) 53–70), and 66.4% were men. The median time between symptom onset and baseline was 8 days (IQR 6–10). Oxygen requirement was lower for patients in the no-CTC than CTC group: 22 (10.8%) and 130 (18.9%) received ≤1 L/min oxygen at baseline. Among the 194 patients who received corticosteroids, 53 (27.3%) received dexamethasone, 71 (36.6%) methylprednisolone, 21 (10.8%) prednisolone and 49 (25.3%) prednisone. At baseline, 85 patients (9.6%) also received hydroxychloroquine and 60 (6.7%) lopinavir–ritonavir (Table 1 , Supplementary Material 4). During follow-up, 146 patients additionally received hydroxychloroquine, 111 lopinavir–ritonavir, 14 remdesivir, and 19 interleukin-6 inhibitors (Supplementary Material 5).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients in the corticosteroids (CTC) and no-CTC groups at baseline. The numbers in brackets in the first column correspond to the actual quantity of data available for the corresponding variables before imputation of missing baseline data by multiple imputations by chained equations using the other variables available

| Characteristic | Total | CTC | No-CTC group | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical data: | ||||

| Age, median (IQR) year | 63 (53–70) | 64 (56–72) | 62 (52–70) | 0.013 |

| Male sex | 66.4 (592) | 71.4 (145) | 65.0 (447) | 0.09 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Chronic respiratory disease (incl. asthma) | 5.6 (50) | 9.4 (19) | 4.5 (31) | 0.008 |

| Chronic heart failure (NYHA I–III) (n = 890) | 3.5 (31) | 3.9 (8) | 3.3 (23) | 0.69 |

| Cardiovascular diseases (incl. hypertension) | 44.7 (398) | 48.3 (98) | 43.6 (300) | 0.24 |

| Diabetes not requiring insulin (n = 886) | 17.6 (156) | 18.2 (37) | 17.4 (119) | 0.79 |

| Diabetes requiring insulin (n = 889) | 5.8 (52) | 4.5 (9) | 6.3 (43) | 0.34 |

| Chronic kidney failure | 3.0 (27) | 3.4 (7) | 2.9 (20) | 0.69 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 0.4 (4) | 0.5 (1) | 0.4 (3) | 1 |

| Immunosuppression (n = 890) | 5.4 (48) | 6.9 (14) | 4.9 (34) | 0.28 |

| BMI > 30 kg/m2 (n = 742) | 32.3 (240) | 27.8 (52) | 33.9 (188) | 0.12 |

| Treatment with ACEIs or ARBs (n = 888) | 26.8 (238) | 30.7 (62) | 25.7 (176) | 0.15 |

| COVID-19 data: | ||||

| Time from symptom onset to eligibility, median (IQR) days (n = 887) | 8 (6–10) | 8 (6–11) | 8 (6–10) | 0.25 |

| Confusion at date of eligibility | 7.9 (70) | 10.3 (21) | 7.1 (49) | 0.13 |

| Dehydration at date of eligibility (n = 888) | 7.2 (64) | 8.9 (18) | 6.7 (46) | 0.29 |

| Respiratory rate, median (IQR)/min (n = 739) | 24 (20–28) | 26 (21–30) | 24 (20–28) | 0.06 |

| Oxygen saturation (without oxygen), median (IQR) (n = 795) | 93 (90–95) | 92 (88–95) | 93 (91–95) | <0.0001 |

| Oxygen flow at admission, median (IQR) L/min | 2.0 (2.0–4.0) | 3.0 (2.0–4.0) | 2.0 (2.0–3.0) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (IQR) mmHg (n = 879) | 129 (116–140) | 129 (117–143) | 129 (115–140) | 0.90 |

| Neutrophil count, median (IQR)/mm3 (n = 851) | 4790 (3435–6498) | 5000 (3508–6900) | 4750 (3400–6290) | 0.06 |

| Lymphocyte count, median (IQR)/mm3 (n = 852) | 900 (690–1201) | 860 (642–1210) | 920 (700−1200) | 0.34 |

| Platelet count, median (IQR) x1000/mm3 (n = 878) | 197 (157–254) | 182 (146–254) | 198 (159–253) | 0.70 |

| C-reactive protein median (IQR) mg/L | 100 (64–149) | 111 (73–174) | 95 (61–141) | 0.001 |

| Percentage of lung affected >50% on CT scan (n = 694a) | 17.1 (119) | 28.4 (50) | 13.3 (69) | 0.0001 |

| Treatment data: | ||||

| Corticosteroidb | ||||

| Dexamethasone | 27.3 (53) | 27.3 (53) | ||

| Methylprednisolone | 36.6 (71) | 36.6 (71) | ||

| Prednisolone | 10.8 (21) | 10.8 (21) | ||

| Prednisone | 25.3 (49) | 25.3 (49) | — | — |

| High-dose corticosteroids (≥120 mg/day) | 41.8 (81) | 41.8 (81) | — | — |

| Corticosteroid treatment duration, median (IQR) days (n = 194) | 7 (6 −11) | 7 (6 −11) | — | — |

| Time from symptom onset to corticosteroids, median (IQR) days | 10 (8–13) | 10 (8–13) | — | — |

| Treatment with lopinavir–ritonavir at baseline (n = 890) | 6.7 (60) | 15.3 (31) | 4.2 (29) | <0.0001 |

| Treatment with hydroxychloroquine at baseline (n = 889) | 9.6 (85) | 12.4 (25) | 8.7 (60) | 0.11 |

Results are presented as % (absolute number) unless stated otherwise.

IQR, interquartile range; NYHA, New York Heart Association; BMI, body mass index; ACEIs, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARBs, angiotensin receptor blockers.

127 patients did not have a CT scan at admission.

Corresponds to the data for the 194 patients who received corticosteroids within 5 days of eligibility, with at least 0.8 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone or 0.4 mg/kg/day eq. prednisone if co-administered with lopinavir–ritonavir.

Propensity score model development

Propensity scores ranged from 0.08 to 0.89 and from 0.04 to 0.83 in the CTC and no-CTC groups, with 93.2% in the region of common support (0.08–0.83) (Supplementary Material 6). Among the 25 covariates in the planned PS, one (liver cirrhosis) was dropped from the final model because only one patient had liver cirrhosis in the CTC group. After applying IPTW, all 25 covariates (including liver cirrhosis) had weighted standardized differences <10% (Supplementary Material 7).

Follow-up and outcomes

Among the 891 patients included in the main analysis, 78 had follow-up <28 days (70 were discharged in good health status) and 63 died before day 28. Median follow-up for surviving patients was 80 days (IQR 38–94).

In the unweighted sample, by day 28, 18.0% (n = 36) and 19.4% (n = 131) of patients in the CTC and no-CTC groups had been intubated or died (HR 0.89, 95%CI 0.62–1.28). In total, 8.5% (n = 17) and 6.9% (n = 46) of patients died in the CTC and no-CTC groups (HR 1.23, 95%CI 0.70–2.13). On day 28, 79.9% (n = 148) and 83.6% (n = 522) of patients, respectively, were weaned from oxygen (RR 0.96, 95%CI 0.88–1.03). Furthermore, 81.6% (n = 151) and 84.4% (n = 529), respectively, were discharged to home/rehabilitation (RR 0.97, 95%CI 0.90–1.04). From the number of events observed in our data, our sample allowed for 45% to 70% power to detect an HR of 0.7 to 0.6, consistent with results for patients ≤70 years old in the RECOVERY trial.

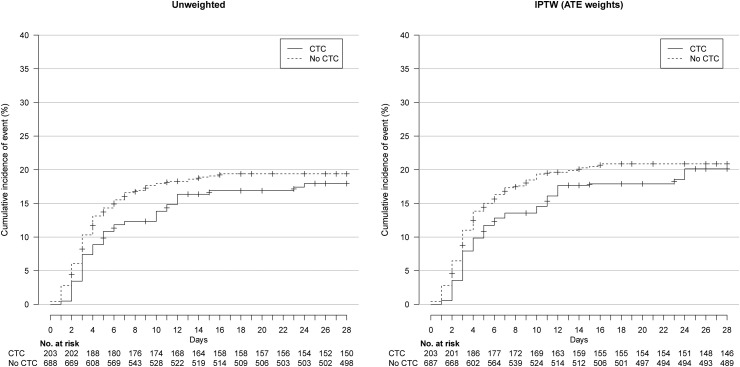

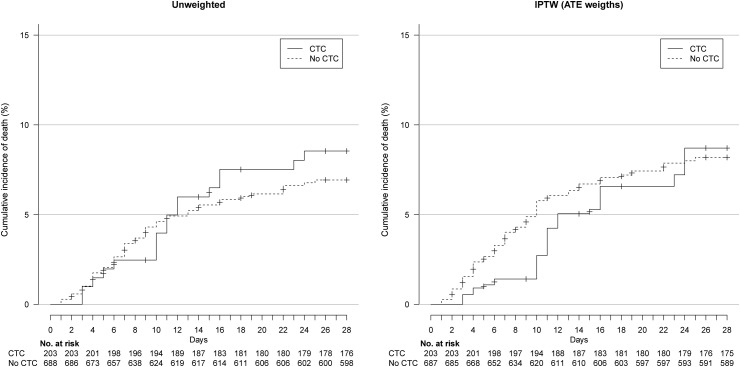

In the IPTW analyses, on day 28, 20.1% and 20.9% of patients in the CTC and no-CTC groups had been intubated or died (wHR 0.92, 95%CI 0.61–1.39) (Fig. 2 ) and 8.7% and 8.2% died, respectively (wHR 1.03, 95%CI 0.54–1.98) (Fig. 3 , Table 2 ). The two groups did not differ in oxygen weaning (wRR 0.98, 95%CI 0.89–1.07) or discharge to home/rehabilitation (wRR 1.00, 95%CI 0.92–1.09) (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Cumulative event curve for intubation or death in the unweighted and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) sample. ATE, average treatment effect.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative event curve for death in the unweighted and inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) sample. ATE, average treatment effect.

Table 2.

Primary and secondary outcomes at day 28. Inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) estimates the average treatment effect (ATE) on the whole population

| Outcomes | No. of events |

Ratio (95%CI) | IPTW ratioa (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTC group (n = 203) |

No-CTC group (n = 688) |

|||

| Intubation or death | 36 | 131 | HR 0.89 (0.62–1.28) | wHR 0.92 (0.61–1.39) |

| Death | 17 | 46 | HR 1.23 (0.70–2.13) | wHR 1.03 (0.54–1.98) |

| Oxygen weaning | 148/186a | 522/625a | RR 0.96 (0.88–1.03) | wRR 0.98 (0.89–1.07) |

| Discharge from hospital to home or rehabilitation | 151/186a | 529/627a | RR 0.97 (0.90–1.04) | wRR 1.00 (0.92–1.09) |

CTC, corticosteroids-receiving group; No CTC, standard of care, not receiving corticosteroids; HR, hazard ratio; RR, relative risk; wHR, weighted hazard ratio; wRR, weighted relative risk; CI, confidence interval.

Missing data were managed by using multiple imputations by chained equations.

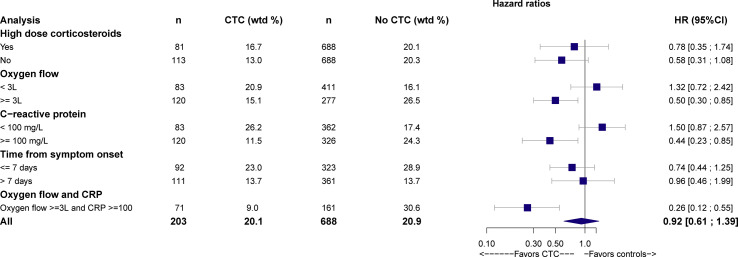

Results for subgroups are presented in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Material 8. Corticosteroids reduced the risk of intubation or death by day 28 for patients with oxygen ≥3 L/min (outcome met for 15.1% of 120 patients in the CTC group versus 26.5% of 277 patients in the no-CTC group, wHR 0.50, 95%CI 0.30–0.85) and CRP level >100 mg/L (11.5% of 120 patients in the CTC group versus 24.2% of 326 patients in the no-CTC group, wHR 0.44, 95%CI 0.23–0.85). Corticosteroids greatly reduced the risk of intubation or death for patients with both oxygen ≥3 L/min and CRP level >100 mg/L at baseline (9% of 71 patients in the CTC group versus 30.6% of 161 patients in the no-CTC group, wHR 0.26, 95%CI 0.12–0.55). Finally, we did not find a significant effect of corticosteroids among patients with a time since symptom onset >7 days (13.7% of 111 patients in the CTC group versus 13.7% of 361 patients in the no-CTC, wHR 0.96, 95%CI 0.46–1.99).

Fig. 4.

Effect of corticosteroids on 28-day intubation or death in subgroups defined by oxygen requirement, C-reactive protein (CRP) level and time from symptom onset, at baseline. CTC, corticosteroids; HR, hazard ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval.

We performed several sensitivity analyses, and all findings were consistent with the main analysis (Supplementary Material 9). We found no significant centre effect (Supplementary Material 10).

Safety

Overall, 845 adverse events were extracted from patient records; 464 patients experienced at least one adverse event (150/283, 53.0% and 314/682, 46.0%) among patients with and without corticosteroids (Table 3 ). Differences involved mainly a higher number of hyperglycaemia events for patients with corticosteroids (64/283, 22.6% versus 86/682, 12.6%). Rate of infection was not increased in patients with corticosteroids (50/283, 17.7% versus 128/682, 18.8%).

Table 3.

Adverse events (counted in the safety population, without weighting)

| Adverse event | CTC group (n = 283) |

No-CTC group (n = 682) |

Difference (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any | 53.0 (150) | 46.0 (314) | 7.0 (0.0–13.9) |

| Expected with corticosteroids: | |||

| Infection (incl. ventilator-associated pneumonia) a | 17.7 (50) | 18.8 (128) | –1.1 (–6.4–4.2) |

| Bacterial | 7.1 (20) | 7.5 (51) | 0.4 (–4.0–3.2) |

| Viral | 0.7 (2) | 0.7 (5) | 0 (–1.2–1.1) |

| Fungal | 1.1 (3) | 0.7 (5) | 0.3 (–1.0–1.7) |

| Undocumented b | 9.5 (27) | 9.5 (77) | –1.7 (–5.9–2.4) |

| Ventilator-associated pneumonia | 6.0 (17) | 8.9 (61) | –2.9 (–6.4–0.6) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 22.6 (64) | 12.6 (86) | 10.0 (4.5–15.5) |

| Hypertension | 10.6 (30) | 11.1 (76) | –0.5 (–4.8–3.8) |

| Confusion or psychiatric manifestation | 1.4 (4) | 1.9 (13) | –0.5 (–2.2–1.2) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4.6 (13) | 3.8 (26) | 0.8 (–2.0–3.6) |

| Hypokalaemia or fluid overload | 1.1 (3) | 1.3 (9) | –0.3 (–1.7–1.2) |

| Other severe adverse events: | |||

| Thromboembolic event (incl. pulmonary embolism) | 2.8 (8) | 3.5 (24) | –0.7 (–3.1–1.7) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 2.1 (6) | 2.6 (18) | –0.5 (–2.6–1.5) |

| Increased serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase | 5.3 (15) | 4.4 (30) | 0.9 (–2.1–3.9) |

| Renal failure | 2.5 (7) | 2.6 (18) | –0.2 (–2.3–2.0) |

Results are presented as % (absolute number).

Total number of infections differs from the sum of subcategories because a patient may have had multiple infectious adverse events of different nature.

Undocumented infections refer to clinical and biological presentations suggestive of an infectious episode without formal identification of a specific pathogen.

Discussion

We report a multicentre study that used real-world data to emulate a target trial on the effectiveness of corticosteroids for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in non-ICU settings. We found no difference in risk of intubation or death between patients who received and did not receive corticosteroids, although the result was compatible with a 40% reduction in risk. However, rate of intubation or death was lower for patients receiving corticosteroids with ≥3 L/min oxygen or with CRP level >100 mg/L at baseline.

In all, our results are consistent with the hypothesis that that the more severe the disease (i.e. requiring higher oxygen flow and with a more severe inflammatory syndrome), the more effective the treatment. Difference between our results and those from the RECOVERY trial may be due to the fact that we included a large number of patients who had limited requirements for oxygen (e.g. in the no-CTC group, 18% of patients received ≤1 L/min oxygen at baseline) and whose condition may be closer to the subgroup of patients who were not under oxygen at the time of randomization in the RECOVERY trial. Second, to maximize comparability between the two groups, we also chose to exclude patients with severe chronic conditions. This could explain the difference in death rates by 28 days in the no-CTC groups (8.2% in our study and 25% in the RECOVERY trial).

In all, our findings question the benefit/risk balance of corticosteroids in patients with the least severe disease. Indeed, although we found no increase in secondary infections, hyperglycaemia occurrence was higher in patients with corticosteroids than in those without.

Our study is based on the analysis of a large number of consecutive patients and provides insight into the management of COVID-19 during the study period in France and Luxembourg. All safety data were reviewed in duplicate and independently by several clinicians, which strengthens our confidence in the absence of any warning signal for using corticosteroids in COVID-19 pneumonia in terms of secondary bacterial or fungal infection.

Our study has several limitations. First, despite the use of robust methods to draw causal inferences, our study is observational, and potential unmeasured confounders may bias our results [26]. Second, our study dealt with a heterogeneous prescription of corticosteroids in terms of drugs, time of start, dose, administration mode and duration. Third, we could not account for duration of corticoid prescription. Indeed, we may have observed only 3 days of corticosteroid treatment for a given patient because an event occurred on the fourth day. Only trials in which the dose and duration are specified before treatment, in ‘intent-to-treat’, can answer this question. Fourth, because we used data from a large number of hospitals, we could not standardize the process of identifying patients eligible to participate in the study. This situation may have led to missing some patients. Fifth, our sample was limited to the number of eligible patients available at the time of analysis, and we cannot rule out that our findings are due to a lack of power.

Conclusions

We found no association between the use of corticosteroids and intubation or death in a broad sample of patients 18–80 years old hospitalized for COVID-19 pneumonia in non-ICU settings in France. However, the use of corticosteroids was associated with reduced rates of intubation or death for patients receiving oxygen ≥3 L/min or CRP level ≥100 mg/L at baseline. These data support the hypothesis that the more severe the disease, the more effective the treatment, and call for discussion of the treatment for patients requiring low oxygen flow.

Ethical approval

This study conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of the Henri-Mondor Hospital (AP-HP), France (no. 00011558) and by the National ethics committee of Luxembourg (no. 0620-101).

Dissemination to related patient and public communities

We plan to issue a press release on official publication of this manuscript and to disseminate our findings through social media outlets, to ensure the results of the study have broad public outreach. The lead author (X. Lescure) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained.

Author contributions

V-TT, EP, PR and F-XL conceived the study. MM, FB, OB, TP, LG, FG and F-XL participated in data collection. V-TT, EP and PR performed the statistical analyses. MM, OB, TP, FG and F-XL reviewed the data for adverse events. MM, LG, and F-XL provided administrative and logistic support. V-TT, MM and F-XL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All members of the writing committee contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All members of the writing committee meet the ICMJE criteria. All members of the writing committee agree with the manuscript results and conclusions. F-XL is the guarantor, had full access to the data in the study, and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Transparency declaration

F-XL received personal fees for lectures from Gilead sciences, bioMerieux and MSD, outside of the submitted work. MM received research funds from GSK, personal fees for lectures from LFB and Amgen, outside of the submitted work. OR reports personal fees and non-financial support from Gilead, personal fees and non-financial support from ViiV, personal fees and non-financial support from MSD, outside the submitted work. FG reports grants from Biomerieux, personal fees from GILEAD, non-financial support from PFIZER, non-financial support from CORREVIO, outside the submitted work. PR reports personal fees from Inato, outside the submitted work. TP, FB, LG and V-TT have nothing to disclose.

Editor: L. Scudeller

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2020.11.035.

Contributor Information

COCORICO Collaborative Group:

François-Xavier Lescure, Viet-Thi Tran, Matthieu Mahévas, Firouze Bani-Sadr, Olivier Robineau, Thomas Perpoint, Elodie Perrodeau, Laure Gallay, Philippe Ravaud, François Goehringer, François-Xavier Lescure, François-Xavier Lescure, Laure Gallay, Matthieu Mahévas, Viet-Thi Tran, Viet-Thi Tran, Elodie Perrodeau, Philippe Ravaud, Sophie Ismaël, François Goehringer, François-Xavier Lescure, Matthieu Mahévas, Thomas Perpoint, Viet-Thi Tran, François-Xavier Lescure, Cédric Laouénan, Jennifer Soulier, Oriane Puéchal, Eric D’Ortenzio, Yazdan Yazdanpanah, Laurence Maulin, Stéphanie Martinez, Diane Sanderink, Pascale Fialaire, Séverine Ansart, Lucas Perez, Anne - Laure Destrem, Chloé Moulin, Pascal Gicquel, Frédéric Rivière, Martin Martinot, Mahsa Mohseni Zadeh, Tomasz Chroboczek, Thibaut Challan Belval, Lionel Piroth, Thibault Sixt, Florian Moretto, André Cabié, Jérémie Pasquier, Ornella Cabras, Marine Morrier, Jean Reuter, Thomas Henin, Pierre Braquet, Helene Desmurs-Clavel, Arnaud Hot, Thomas Perpoint, Boris Bienvenu, Belkacem Asselate, Nicolas Vignier, Steve Nguala, Sylvain Diamantis, Guillemette Frémont, Pierre Louis Nivose, Mathilde Thiébaut, François Goehringer, Benjamin Lefevre, Hélène Auge, Paul le Turnier, Naila Benkalfate, Olivier Grossi, Samuel Pineau, Elisa Demonchy, Julie Merindol, Claire Durand, Nathalie Tieulié, Viviane Queyrel, Didier Laureillard, Paul Loubet, Ségolène Greffe, Nathalie Dournon, Youssouf Mohamed Kassim, Cyrille Gourjault, Alexandre Lahens, François-Xavier Lescure, Paul Legendre, Caroline Morbieu, Matthieu Mahevas, Giovanna Melica, Jean-Daniel Levièvre, Frédéric Schlemmer, Simone Tunesi, Claire Leblanc, Anne Bourgarit-Durand, Alexandre Bleibtreu, Gianpiero Tebano, Jérôme Pacanowski, Jean-Benoit Zabbe, Mathilde Devaux, Laurent Bellec, Marine Gosset-Woimant, Céleste Lambert, Firouze Bani-Sadr, Maxime Hentzien, Amélie Servettaz, Kevin Alexandre, Manuel Etienne, Romain Leguillon, Marion Dollat, Rémi Lefrancois, Anne Pouvaret, Yvon Ruch, Yannick Dieudonné, Guillaume Martin-Blondel, Xavier Boumaza, Margaux Lafaurie, Olivier Robineau, Macha Tetart, Adrien Lemaignen, Nicole Ferreira-Maldent, Amélie Duréault, Marie Gousseff, Claire Chantepie, Francesca Bisio, Fanny Pommeret, Emeline Colomba Blamble, and Claire Ara Somohano

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Tay M.Z., Poh C.M., Rénia L., MacAry P.A., Ng L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:363–374. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhimraj A., Morgan R.L., Shumaker A.H., Lavergne V., Baden L., Cheng V.C. Infectious diseases society of America guidelines on the treatment and management of patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa478. Apr 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fadel R., Morrison A.R., Vahia A., Smith Z.R., Chaudhry Z., Bhargava P. Early short course corticosteroids in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J., Huang J., Zhu G., Liu Y., Xiao H., Zhou Q. Systemic corticosteroids and mortality in severe and critical COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:e4230–e4239. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bani-Sadr F., Hentzien M., Pascard M., N’Guyen Y., Servettaz A., Andreoletti L. Corticosteroid therapy for patients with COVID-19 pneumonia: a before–after study. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56:106077. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.106077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu X., Chen T., Wang Y., Wang J., Yan F. Adjuvant corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:241. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02964-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haberman R., Axelrad J., Chen A., Castillo R., Yan D., Izmirly P. Covid-19 in immune-mediated inflammatory diseases - case series from New York. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:85–88. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu X.W., Wu X.X., Jiang X.G., Xu K.J., Ying L.J., Ma C.L. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-Cov-2) outside of Wuhan, China: retrospective case series. BMJ. 2020;368:m606. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horby P., Lim W.S., Emberson J.R., Mafham M., Bell J.L., Linsell L. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sterne J.A.C., Murthy S., Diaz J.V., Slutsky A.S., Villar J., Angus D.C. Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus D.C., Derde L., Al-Beidh F., Annane D., Arabi Y., Beane A. Effect of hydrocortisone on mortality and organ support in patients with severe COVID-19: the REMAP-CAP COVID-19 Corticosteroid Domain Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2020;324:1317–1329. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tomazini B.M., Maia I.S., Cavalcanti A.B., Berwanger O., Rosa R.G., Veiga V.C. Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2020;324:1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeronimo C.M.P., Farias M.E.L., Val F.F.A., Sampaio V.S., Alexandre M.A.A., Melo G.C. Methylprednisolone as adjunctive therapy for patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (Metcovid): a randomised, double-blind, phase IIb, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartoletti M., Marconi L., Scudeller L., Pancaldi L., Tedeschi S., Giannella M. Efficacy of corticosteroid treatment for hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19: a multicenter study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corral L., Bahamonde A., Arnaiz delas Revillas F., Gomez-Barquero J., Abadia-Otero J., Garcia-Ibarbia C. GLUCOCOVID: a controlled trial of methylprednisolone in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00508-020-01805-8. 10.1101/2020.06.17.20133579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu Z., Li X., Fan G., Zhou F., Wang Y., Huang L. Low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids treatment in hospitalized adults with COVID-19. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:112–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hernan M.A., Robins J.M. Using big data to emulate a target trial when a randomized trial is not available. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;183:758–764. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Josephson F. Drug-–drug interactions in the treatment of HIV infection: focus on pharmacokinetic enhancement through CYP3A inhibition. J Intern Med. 2010;268:530–539. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Austin P.C. Balance diagnostics for comparing the distribution of baseline covariates between treatment groups in propensity-score matched samples. Stat Med. 2009;28:3083–3107. doi: 10.1002/sim.3697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robins J.M., Hernan M.A., Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550–560. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hermine O., Mariette X., Tharaux P.L., Resche-Rigon M., Porcher R., Ravaud P. Effect of tocilizumab vs usual care in adults hospitalized with COVID-19 and moderate or severe pneumonia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zeng Z., Yu H., Chen H., Qi W., Chen L., Chen G. Longitudinal changes of inflammatory parameters and their correlation with disease severity and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 from Wuhan, China. Crit Care. 2020;24:525. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-03255-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buttgereit F., da Silva J.A., Boers M., Burmester G.R., Cutolo M., Jacobs J. Standardised nomenclature for glucocorticoid dosages and glucocorticoid treatment regimens: current questions and tentative answers in rheumatology. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:718–722. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.8.718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bacchetti P., McCulloch C.E., Segal M.R. Simple, defensible sample sizes based on cost efficiency. Biometrics. 2008;64:577–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2008.01004_1.x. discussion 586-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bacchetti P. Current sample size conventions: flaws, harms, and alternatives. BMC Med. 2010;8:17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hernán M.A. The C-word: scientific euphemisms do not improve causal inference from observational data. Am J Public Health. 2018;108:616–619. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.