Summary

Congenital ear anomalies have been known to cause lasting psychosocial consequences for children. Congenital ear anomalies can generally be divided into malformations (chondro-cutaneous defect) and deformations (misshaped pinna). Operative techniques are the standard for correction at a minimal age of 5–7, exposing the children to teasing and heavy complications. Ear molding is a non-operative technique to treat ear anomalies at a younger age. Having been popularized since the 1980s, its use has increased over the past decades. However, uncertainties about its properties remain. Therefore, this review was conducted to look at what is known and what has been newly discovered in the last decade, comparing different treatment methods and materials. A literature search was performed on PubMed, and 16 articles, published in the last decade, were included. It was found that treatment initiated at an early age showed higher satisfactory outcome rates and a shorter duration of treatment. A shorter duration of treatment also led to higher satisfactory rates, which might be attributable to age at initiation, individual moldability, and treatment compliance. Complications were minor in all articles. Recurrence rate was low and mostly concerned prominent ears, which proved to be the most difficult to correct deformity as well. Malformations, however, were even more difficult to treat than deformations. Our analysis shows ear molding to be a successful treatment method for ear anomalies with a preference for early diagnosis and treatment.

Introduction

Not every infant is born with anatomically correct ears (Fig. 1). Congenital ear anomalies are a defect that may occur during the fetal or perinatal period. There are two different kinds of ear anomalies: malformations, chondro-cutaneous defects occurring during fetal development,1–4 and deformations, which develop perinatally.1 Examples of malformations are microtia (small external ear), anotia (no external ear), or preauricular skin tags or sinuses.1,5 Examples of deformations are conchal crus, cryptotia, helical rim deformities, lidding/lop ear, Stahl’s/Spock ear, and prominent ear (Figs. 2–8).6 The pathogenesis of deformations is unknown, but it is believed that they are caused by either external pressure or abnormal ear muscle development, or genetic predisposition.7–10 A distinct kind is the constricted ear. This type of ear anomaly has the appearance of a cup ear but is seen as a malformation when severe. Malformations have a lower incidence than deformations.11

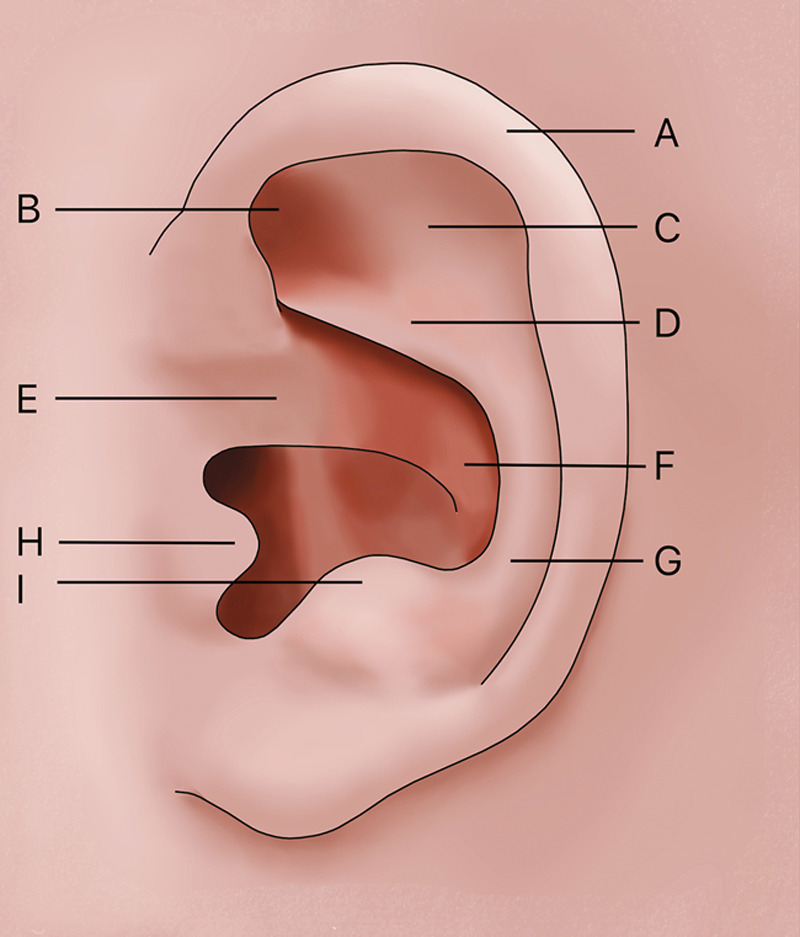

Fig. 1.

Diagram representing the normal anatomy of a neonatal ear. A: helix. B: triangular fossa. C: antihelix superior crus. D: antihelix inferior crus. E: root of helical crus. F: concha. G: tail of antihelix. H: tragus. I: antitragus.

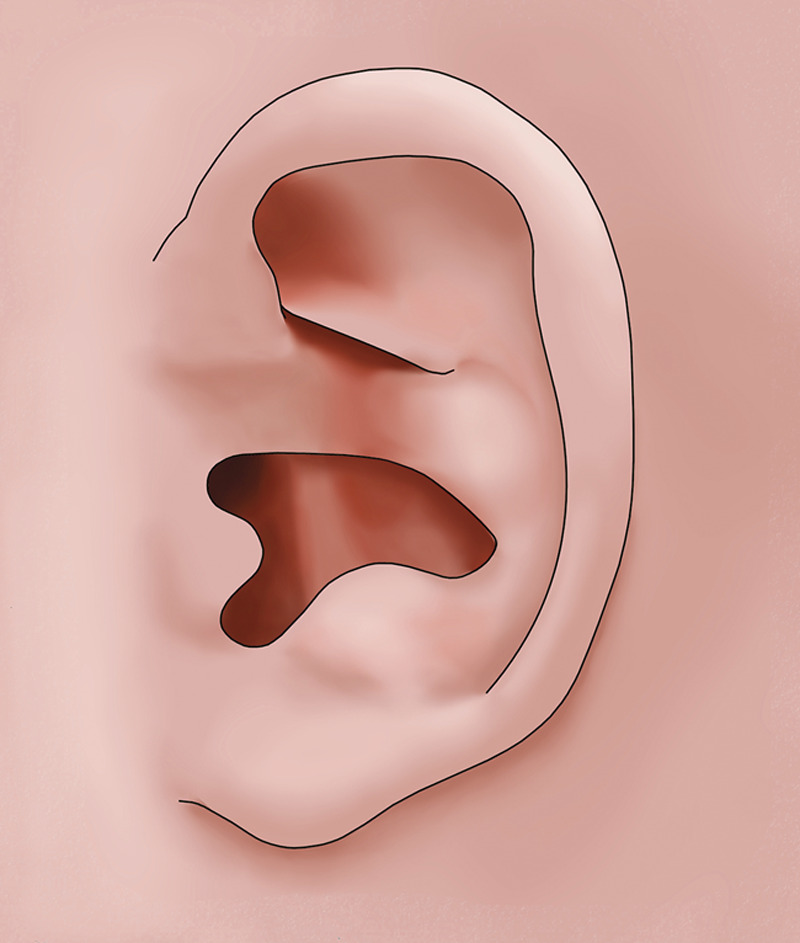

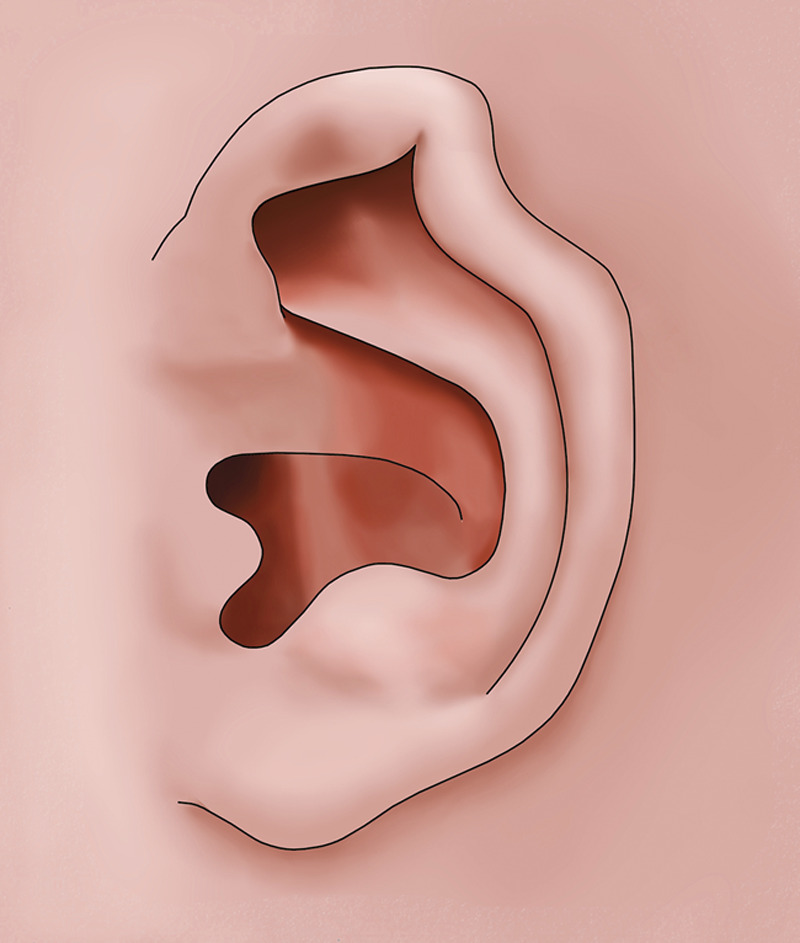

Fig. 2.

Image depicting the conchal crus deformity. A cartilaginous convex crus extends into the vertical wall of the concha and may cause outward bulging of the concha.

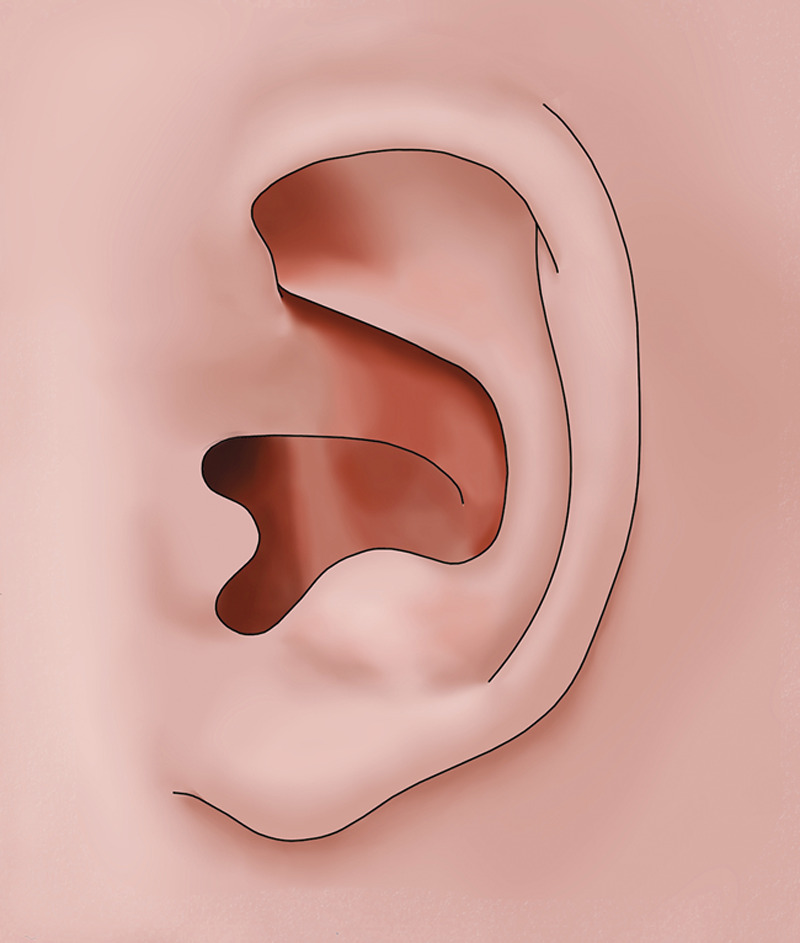

Fig. 8.

Illustration of a prominent ear deformity in which the conchal-mastoid angle is widened.

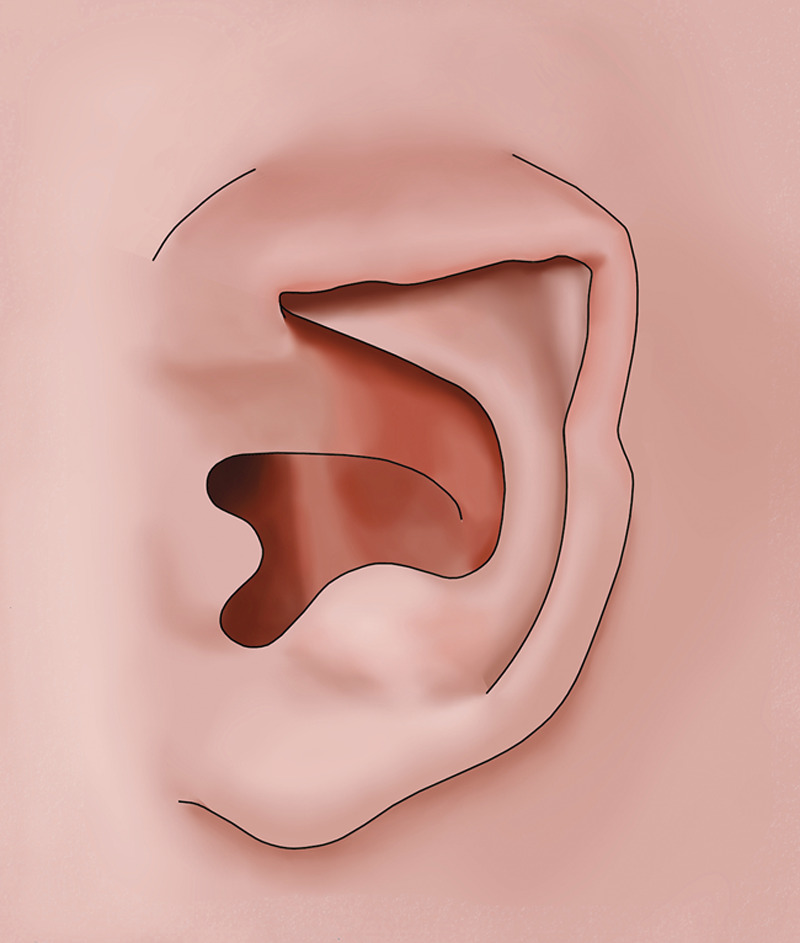

Fig. 3.

Diagram displaying the cryptotia deformity. There is no retroauricular skin sulcus.

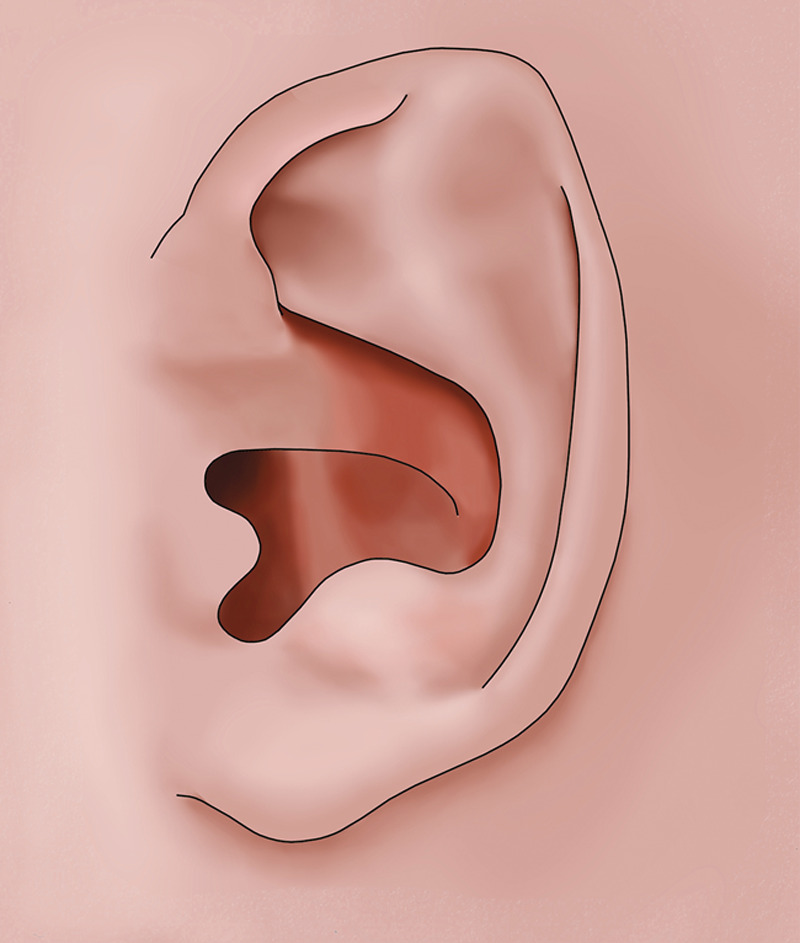

Fig. 4.

Illustration of the helical rim deformity. The helical rim may be absent or folded.

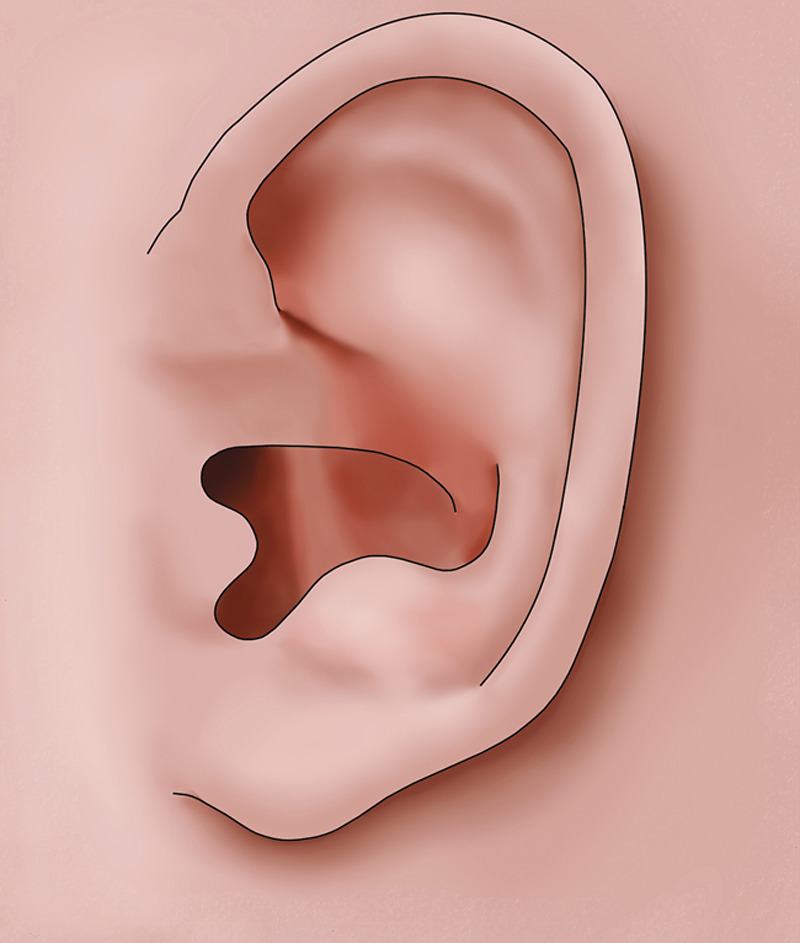

Fig. 5.

Diagram representing the lidding/lop ear deformity. The helical rim and sometimes scapha is folded over the rest of the ear.

Fig. 6.

Image depicting the Stahl’s/Spock ear deformity. A cartilaginous crus extends from the antihelix into the helical rim.

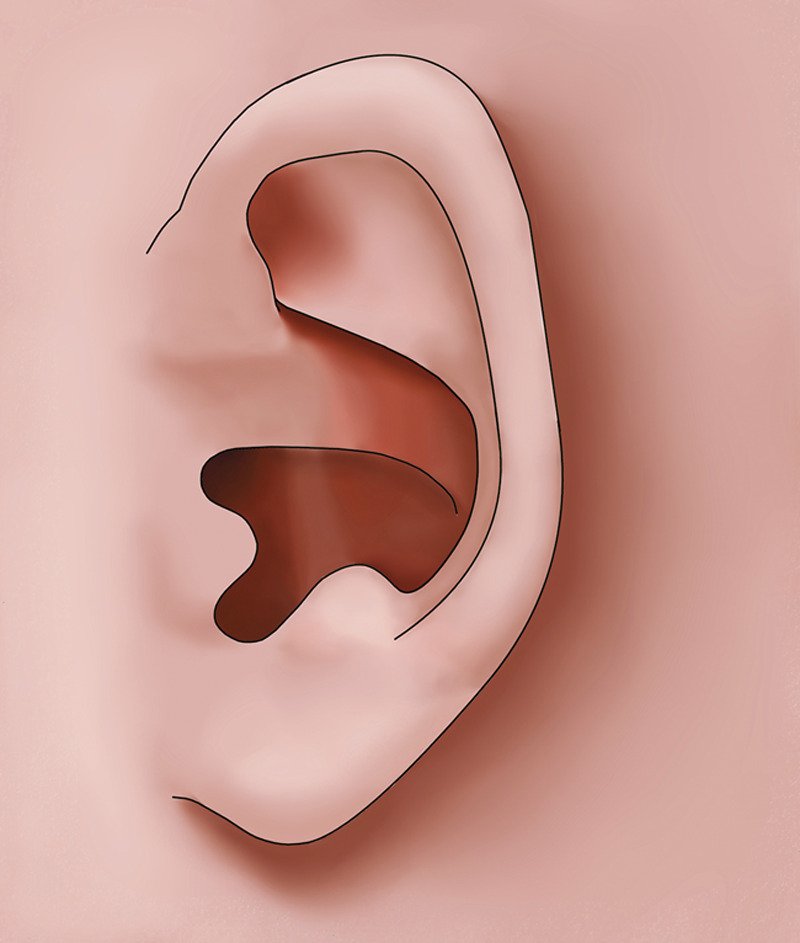

Fig. 7.

Illustration of a prominent ear deformity in which the antihelical fold is absent.

Although the incidence of ear anomalies is variable in literature,12–17 ear anomalies are widely known as consequential birth defects. These anomalies may have a lasting psychosocial impact as a consequence of teasing during childhood.17–19 Otoplasty is currently still the most acknowledged treatment, performed the earliest at age 5–7.16,20,21 Complications of such a procedure may be dreadful and may include tissue necrosis, hematoma, bleeding, infection, or hypertrophic scarring, with complication rates varying from 0% to 10%.22,23 Furthermore, psychosocial consequences will be mitigated, but will not always fully disappear by performing an otoplasty.18,19

Ear molding was popularized in the 1980s14,24–26 and has been an upcoming method of treatment. Due to this treatment being initiated at an early age, children are no longer exposed to the psychosocial consequences of having an ear anomaly. Furthermore, surgery will have psychosocial implication, whereas molding does not. Unfamiliarity about the technique, the duration of treatment, the age at which molding should be initiated, and what kind of ear anomalies can be treated have long been the reasons for a delay in the implementation of this technique.6,17,27–29 To find a general consensus about these different aspects of treatment, this review was conducted, including articles published during the last decade.

Methods

A literature search was performed in December 2019 using the PubMed database of the US National Library of Medicine, reviewing articles published between the fourteenth of December 2009 and the fourteenth of December 2019. The following search terms were used: ear, auricle, non-surgical ear treatment, non-surgical ear correction, ear molding, ear splinting, ear anomaly, ear deformity, congenital ear deformity, congenital ear anomaly, auricular anomaly, auricular deformity, congenital auricular deformity, and congenital auricular anomaly.

Articles were excluded if they were literature reviews or did not concern research on the non-surgical correction of anomalies of the external ear in neonates, when the article concerned only case reports or when the article did not report treatment results. Articles were also excluded if not fully available or when written in a language other than English, German, or French.

The search provided 200 results, of which 16 articles were included after application of the exclusion criteria by 3 authors independently. There were no disagreements in grading of the eligibility of the articles. From the reviewed articles, the treatment materials or devices and duration were listed (Table 1). The number of ears treated, the different kinds of deformations or malformations, the age at initiation of treatment, the results, complications, the follow-up period and the recurrence of the anomaly were also listed (Table 2).

Table 1.

Molding Materials Used per Article and Duration of Treatment

| Study | Treatment Material | Treatment Duration (range) | Study Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byrd6 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 6 wk | Prospective |

| Calonge20 | Moldable metal wire within a silicone feeding tube and adhesive fixation strips (SteriStrips) | 6 wk | Prospective |

| Chan30 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 4.1 wk (1–6 wk) | Prospective |

| Chang28 | A precut Velcro base piece, Dermabond skin adhesive, soft silicone rubber conformers, and polysiloxane gel | 3.85 wk (1.7–6.57 wk) | Retrospective |

| Daniali31 | EarWell Infant Corrective System, taping if indicated. | 37 d (12–109 d) | Retrospective |

| Doft32 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 14 d (7–42 d) | Prospective |

| Leonardi33 | Lead-free wire inserted in suction catheter and adhesive fixation strips (SteriStrips) | (5–8 wk) | Prospective |

| Matic34 | 8-French red rubber catheter, Mastisol liquid adhesive and adhesive fixation strips (SteriStrips) | 8 d (5–14 d) | Prospective |

| Mohammadi29 | Stainless steel wire within soft and flexible silicone with a 4-mm diameter and adhesive surgical tapes | 13.33 wk (11–18 wk) | Prospective |

| Petersson35 | 24-gauge copper wire through a 6- or 8-Fr silicone feeding tube with adhesive fixation strips (SteriStrips) | (4 d–4 wk) | Prospective |

| Schratt36 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 20 d (12–28 d) | Prospective |

| Van Wijk37 | A bendable, rounded splint, known as Earbuddies Ltd and tape, together with a Cavilon barrier film | (2 wk–19 wk)* | Prospective |

| Vincent38 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 5 wk | Prospective |

| Woo39 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 32.7 d (24–53 d) | Retrospective |

| Woo17 | Babyears; stainless wire in silicone tube with caps, combined with fixation adhesive tapes (SteriStrips) | 44.3 d (8–169 d) | Retrospective |

| Zhang40 | EarWell Infant Corrective System | 1.14 mo (0.33–4.0 mo) | Retrospective |

*As read from a boxplot. Not specified in text.

Table 2.

Overview of the Literature on the Nonsurgical Correction of Congenital Ear Anomalies

| Study | N. | Anomaly (%) | Age at the Initiation of Treatment | Results* | Scored by | Compl (%) | FU | R (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Byrd6 | 58 | Prominent/cup | 1 wk–? | Excellent/good >90% | Author, not specified | Skin excoriations (5%), skin rash (1.7%) | ? | ? | |

| Lidding/lop | |||||||||

| Mixed | Poor <10% | ||||||||

| Stahl’s ear | |||||||||

| Helical rim | |||||||||

| Conchal crus | |||||||||

| Cryptotia | |||||||||

| Calonge20 | 79 | Cryptotia | 0 wk – not specified “release from maternity ward” | Not specified, “16.8% needed surgery afterwards” | Author, not specified | None (0%) | ? | ? | |

| Cup ear | |||||||||

| Stahl’s ear | |||||||||

| Prominent | |||||||||

| Other | |||||||||

| Chan30 | 105 | Deformations (66.7%): | 15.7 d | Deformations | Clinician | Pressure ulcers/excoriation, dermatitis (46%) | 12.7 mo | 9% | 34 ears did not complete treatment and were not analyzed |

| Lidding (28.6%) | (0 – 97 d) | Excellent 69.6% | (6–32 mo) | ||||||

| Stahl’s ear (18.1%) | Good 28.3% | ||||||||

| Helical rim (9.5%) | Poor 2.2% | ||||||||

| Prominent (4.8%) | Malformations | ||||||||

| Lop ear (4.8%) | Excellent 32% | ||||||||

| Conchal crus (0.95%) | Good 32% | ||||||||

| Malformations (33.3%): | Poor 36% | ||||||||

| Constricted (32.4%) | |||||||||

| Cryptotia (0.95%) | |||||||||

| Chang28 | 33 | Stahl’s ears (24.2%) | 31.21 d | Excellent 46% | Clinician | Mild skin irritation (6%) | ? | ? | Retrospective |

| Lop ears (18.2%) | (6–106 d) | Good 46% | |||||||

| Prominent (21.2%) | Poor 7% | ||||||||

| Helical rim (30.3%) | |||||||||

| Mixed (6.1%) | |||||||||

| Daniali31 | 478 | Deformations (63.4%): | 12.5 d | Deformations | Clinician | Skin excoriations, allergic reaction, infection (7.6%) | ? | ? | Retrospective |

| Prominent (5.6%) | Excellent 74.9% | ||||||||

| Lidding (12.1%) | Good 19.5% | ||||||||

| Conchal crus (16.7%) | Poor 5.6% | ||||||||

| Stahl’s ear (13.2%) | Malformations | ||||||||

| Helical rim (15.7%) | Excellent/good 88.6% | ||||||||

| Malformations (36.6%): | |||||||||

| Constricted (35.9%) | Poor 11.4% | ||||||||

| Cryptotia (0.73%) | |||||||||

| Doft32 | 158 | Constricted (18%) | <2 wk | Excellent 70% | Parents | Mild pressure ulcerations (3%) | 6 mo, 12 mo | 3% | |

| Cryptotia (18.5%) | (0–6 wk) | Good 26% | |||||||

| Helical rim (38%) | Poor 4% | ||||||||

| Prominent (0.5%) | |||||||||

| Stahl’s ears (25%) | |||||||||

| Leonardi33 | 22 | Lop ears (27.3%) | 2–42 d | Excellent 72.73% | Author/parents | None (0%) | 6 mo | 18% | |

| Constricted (36.3%) | Good 27.28% | ||||||||

| Prominent (18.2%) | Poor 0.0% | ||||||||

| Stahl’s ear (18.2%) | |||||||||

| Matic34 | 33 | Stahl’s ear (100%) | 2 d | Excellent 97.0% | Clinician | None (0%) | 14 mo | 0% | |

| (1–7 d) | Good 3.0% | ||||||||

| Poor 0.0% | |||||||||

| Mohammadi29 | 29 | Prominent (37.9%) | 7.52 wk | Excellent 9.5% | Clinician/nurse | None (0%) | ? | 0% | 8 patients did not complete treatment and were not analyzed |

| Lop ear (27.6%) | (2 – 24 wk) | Good 47.6% | |||||||

| Constricted (34.5%) | Poor 42.9% | ||||||||

| Petersson35 | 17 | Cup ear (41.2%) | 1 d (47%) | Excellent 61.8% | Clinician/parents | None (0%) | 1 wk–12 mo | 5.9% | |

| Stahl’s ear (35.3%) | 2 d (53%) | Good 38.2% | |||||||

| Prominent (23.5%) | Poor 0% | ||||||||

| Schratt36 | 32 | Helical rim (38%) | 6 d | Excellent 48.5% | Clinician/parents | Skin excorations, swelling, redness, pressure marks (12.5%) | 2 y | 12.5 – 25% | |

| Cup ear (25%) | (0–3 wk) | Good 40.5% | |||||||

| Antihelix (13%) | Poor 11% | ||||||||

| Stahl ear (15%) | |||||||||

| Other (9%) | |||||||||

| VanWijk37 | 209 | Prominent (100%) | 8.8 wk | Excellent 28% | Author/clinician | Skin irritation (4.8%) | 1 y | ? | 52 patients were lost to follow-up or did not complete treatment due to complications |

| (0–39W) | Good 36% | ||||||||

| Poor 36% | |||||||||

| Vincent38 | 42 | Conchal crus (2%) | 2 wk | Excellent 78% | Clinician/parents | Pressure mark (2%) | 6 mo | 14.3% | |

| Stahl’s ear (14%) | (0–6 wk) | Good 13.5% | |||||||

| Helical rim (29%) | Poor 8.5% | ||||||||

| Helical-scapha (33%) | |||||||||

| Helical-scapha –antihelical (21%) | |||||||||

| Woo39 | 28 | Constricted (64.2%) | (0–8 wk) | Excellent/good 89% | Parents | Pressure ulcer | 1 y | 0% | Retrospective |

| Stahl’s ear (21.4%) | Poor 11% | ||||||||

| Prominent (7.1%) | |||||||||

| Cryptotia (7.1%) | |||||||||

| Woo17 | 80 | Satyr ears (35%) | 52.9D | Excellent 43.9% | Clinician/parents | Skin problems (53.7%) scratching (14.6%) | 66.9 d (12–193 d) | ? | Retrospective |

| Darwinian notch (17.5%) | (21–90 d) | Good 48.8% | 22 ears did not complete treatment and were not analyzed | ||||||

| Overfolded (13.75%) | Poor 7.3% | ||||||||

| Cryptotia (5%) | |||||||||

| Lop ear (2.5%) | |||||||||

| Crimped (2.5%) | |||||||||

| Cupped ear (11.25%) | |||||||||

| Stahl’s ear (2.5%) | |||||||||

| Forward facing lobe (28.8%) | |||||||||

| Protruding (2.5%) | |||||||||

| Zhang40 | 141 | Cryptotia (17%) | 2.16 mo | Excellent 77.3% | Author, not specified | Skin rash (4.3%), skin lesion (3.5%) | ? | ? | |

| Lidding (20.6%) | (0.23–12 mo) | Good 19.2% | |||||||

| Cup ear (22%) | Poor 3.5% | ||||||||

| Helical rim (29.1%) | |||||||||

| Stahl’s ear (0.7%) | |||||||||

| Mixed (10.6%) |

N, number of ears treated; Compl, complications; FU, follow-up; R, recurrence; ?, unknown.

* If clinicians and parents scored ears differently, an average was calculated as the final score.

In this table, a differentiation was made between three different outcomes. The outcome could be excellent (indicating that treatment had resulted in a normal ear shape), good (indicating there had been improvement, which was considered successful), or poor (indicating no or very little improvement). These treatment outcomes were based on the classification used by Tan et al41 and implemented for all articles to create uniformity and easily comparable outcomes. Finally, the absolute number of deformities, rather than percentages, was listed, if given. If the article listed assessor differences or results specifically for each deformity, these were listed too (Table 3).

Table 3.

Absolute Numbers of Different Anomalies, the Assessment of these Anomalies when Specified and the Difference in the Overall Assessment between Clinician and Parents (If Present)

| Study | Anomaly and N | Results (Clinician/Parents) | Percentage Difference (Clinician/Parents) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excellent | Good | Poor | ||||

| Calonge20 | 24 Cryptotia | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 6 Cup ears | ||||||

| 6 Stahl’s ears | ||||||

| 5 Prominent | ||||||

| 2 Other | ||||||

| Chan30 | 46 Deformations | 32 | 14 | 0 | Not specified | |

| 20 Lidding | 15 | 5 | 0 | |||

| 12 Stahl’s ears | 8 | 4 | 0 | |||

| 5 Helical rim | 3 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 3 Prominent | 2 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 5 Lop ear | 4 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 1 Conchal crus | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||

| 25 Malformations | 8 | 8 | 9 | |||

| 24 Constricted | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| 1 Cryptotia | 1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Chang28 | 8 Stahl’s ears | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 6 Lop ears | ||||||

| 7 Prominent | ||||||

| 10 Helical rim | ||||||

| 2 Mixed | ||||||

| Daniali31 | 303 Deformations | 227 | 59 | 17 | Not specified | |

| 27 Prominent | 17 | 5 | 5 | |||

| 58 Lidding | 49 | 5 | 4 | |||

| 80 Conchal crus | 60 | 16 | 4 | |||

| 63 Stahl’s ears | 48 | 13 | 2 | |||

| 75 Helical rim | 53 | 20 | 2 | |||

| 175 Malformations | 155* | 0 | 20 | |||

| 172 Constricted | 152* | 0 | 20 | |||

| 3 Cryptotia | 3 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Doft32 | 28 Constricted | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 29 Cryptotia | ||||||

| 60 Helical rim | ||||||

| 1 Prominent | ||||||

| 40 Stahl’s ears | ||||||

| Leonardi33 | 6 Lop ears | 5/6 | 1/0 | 0/0 | Excellent | 68.18%/77.27% |

| 8 Constricted | 6/4 | 2/4 | 0/0 | Good | 31.82%/22.73% | |

| 4 Prominent | 0/3 | 4/1 | 0/0 | Poor | 0%/0% | |

| 4 Stahl’s ears | 4/4 | 0/0 | 0/0 | |||

| Matic34 | 33 Stahl’s ears | 32 | 1 | 0 | Not specified | |

| Mohammadi9 | 8 Prominent | 1 | 3 | 4 | Not specified | |

| 5 Lop ears | 1 | 4 | 0 | |||

| 8 Constricted | 0 | 3 | 5 | |||

| Petersson35 | 7 Cup ears | 3/5 | 4/2 | 0/0 | Excellent | 47.1%/76.5% |

| 4 Prominent ears | 1/2 | 3/2 | 0/0 | Good | 52.9%/23.5% | |

| 6 Stahl’s ears | 4/6 | 2/0 | 0/0 | Poor | 0%/0% | |

| Schratt36 | 12 Helical rims | Not specified | Excellent | 23%/74% | ||

| 8 Cup ears | Good | 68%/21% | ||||

| 4 Antihelix | Poor | 9%/5% | ||||

| 5 Stahl’s ears | ||||||

| 3 Other | ||||||

| VanWijk37 | 77 Prominent | 15 | Not specified | Not specified | ||

| ** 56 Concha-mastoid angle | 44 | |||||

| ** 63 Flat antihelix | ||||||

| Vincent38 | 1 Conchal crus | Not specified | Excellent | 75%/81% | ||

| 6 Stahl’s ears | Good | 16%/11% | ||||

| 12 Helical rim | Poor | 9%/8% | ||||

| 14 Helical - scapha | ||||||

| 9 Helical - scapha – antihelical | ||||||

| Woo39 | 18 Constricted | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 6 Stahl’s ears | ||||||

| 2 Prominent | ||||||

| 2 Cryptotia | ||||||

| Woo17 | 28 Satyr ears | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 14 Darwinian notch | ||||||

| 11 Overfolded | ||||||

| 4 Cryptotia | ||||||

| 2 Lop ears | ||||||

| 2 Crimped ears | ||||||

| 9 Cupped ears | ||||||

| 2 Stahl’s ears | ||||||

| 23 Forward facing ears | ||||||

| 2 Protruding | ||||||

| Zhang40 | 24 Cryptotia | Not specified | Not specified | |||

| 29 Lidding | ||||||

| 31 Cup ear | ||||||

| 41 Helical rim | ||||||

| 1 Stahl’s ear | ||||||

| 15 Mixed | ||||||

N, number.

*Ears were graded as excellent to good.

**Prominent ears may be caused by either deep concha or flat antihelix or both.

Results

Ear Molding Materials and Method of Treatment

Treatment methods (Tables 1, 4) were not always similar. Parents were sometimes taught how to apply the molding material.20,35,37,40 If the material would come off, parents could reapply the material themselves.

Table 4.

Reported Rate of Satisfactory Improvement per Treatment Material

| Treatment Material | Average Satisfactory Improvement (%) |

|---|---|

| Wire in suction catheter | 100 |

| Red rubber catheter | 100 |

| Copper wire within silicone feeding tube | 100 |

| Babyears | 92.7 |

| Velcro system | 92 |

| EarWell Infant Corrective System | 91.5 |

| Metal wire in feeding tube | ~83.2 |

| Earbuddies Ltd® | 64 |

| Steel wire within silicone | 57.1 |

Byrd et al6 and Daniali et al31 used additional retention taping for large ears and for severe deformations or malformations respectively, while Woo et al17 used additional taping for all participants. Patients in the study of Chang et al28 and Mohammadi et al29 were advised to wear a headband during the day. Leonardi et al33 advised this in case of prominent ears only. In the treatment of cryptotia, Daniali et al31 stabilized the pinna out of its buried position before applying the EarWell device. Chan et al30 held the helix distracted for 2 weeks. Vincent et al38 used a self-developed system for Stahl deformities, as they considered the EarWell device unfit for this anomaly. The main problem encountered in use of the different treatment materials was mal-adhesion and early loosening of the material.6,28,30,31,35,36

Age at the Initiation of Treatment

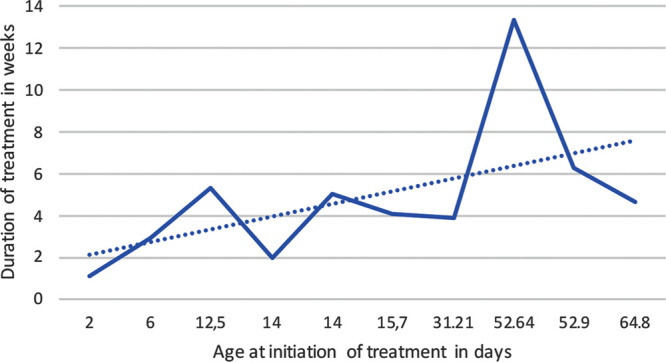

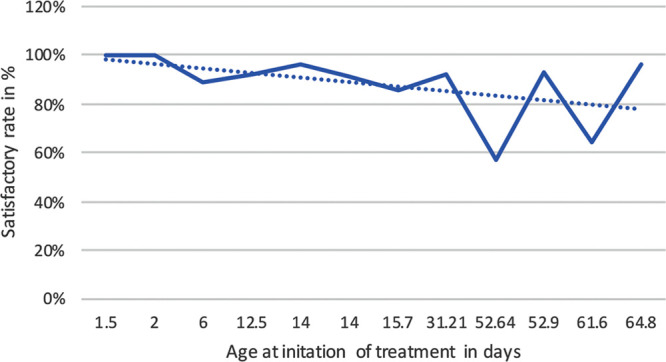

Figures 9 and 10 show age at treatment initiation set against duration of treatment and satisfactory rate respectively, based on data from Tables 1 and 2. One study in particular29 treated relatively old patients for a longer duration and achieved relatively poor results. It can be seen that on average, treatment duration becomes longer as the age of initiation is higher. With the exception of the study from Mohammadi et al, the satisfactory rate remains between 80% and 100%, with a moderate decline as age progresses.

Fig. 9.

Graph depicting age at the initiation of treatment (in days) set against duration of treatment (in weeks). A dotted gridline was added to show the linear relation.

Fig. 10.

Graph depicting age at the initiation of treatment (in days) set against the satisfactory rate (in percentage). A dotted gridline was added to show the linear relation.

Chan et al, Chang et al, and Mohammadi et al found no significant relation between the age at initiation of treatment and outcome,28–30 but Zhang et al mentioned that the success rate is higher for younger children.40 Van Wijk et al reported a significant negative correlation between age at initiation and result.37 Byrd et al, Doft et al, Vincent et al and Woo et al found a decrease in favorable outcomes and an increase in treatment duration in case treatment was delayed.6,32,38,39 Byrd et al stated that only 50% of molding therapy was effective if initiated after the first three weeks of life. Doft et al also noted that parents did not want to delay treatment, despite the possibility of self-correction of the anomaly. Some studies17,29,32,33 excluded infants over a certain age due to reports of treatment becoming less efficient. The age exclusion varied from older than 6 weeks32 to 6 months.29

Byrd et al and Chang et al decided to wait 1 week before initiating treatment, to give spontaneous correction the opportunity to occur.6,28 Mohammadi et al waited for 24 hours, while Schratt et al waited for 72 hours.29,36 In conclusion, there was no general consensus on the ideal waiting period to give spontaneous correction the opportunity to occur.

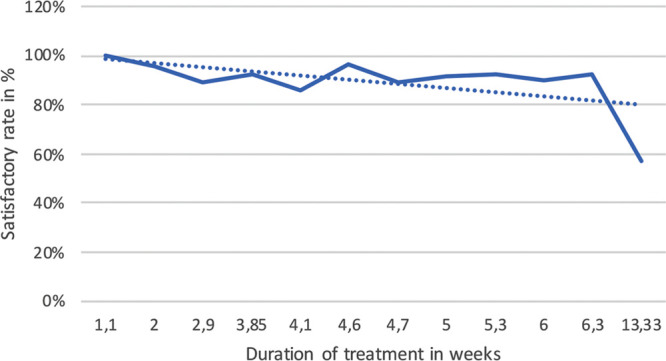

Duration of Treatment

The rate of satisfactory improvement seems to decrease with a longer duration of treatment (Table 1, Fig. 11), but this is more likely due to accompanying factors, such as compliance, comfort, individual moldability, prolonged treatment for dissatisfactory results, and age at initiation of treatment. Chang et al reapplied the treatment materials until results were satisfactory.28 Matic et al applied a 10-minute waiting period during check-ups.34 If the anomaly recurred, the treatment was continued. Petersson et al and Woo et al treated until stabilization of the correction was attained.17,35 Van Wijk et al added 1 week to the treatment duration when results were satisfactory, while terminating treatment in case no correction had been reached after 4 weeks.37 Treatment duration is often based on subjective assessment of intermediate results. Chang et al found that later initiation of treatment resulted in a longer duration of treatment, resulting in lower compliance.28 Chan et al found no significant relation between duration of treatment and outcome.30

Fig. 11.

// Graph depicting the duration of treatment (in weeks) set against satisfactory rate (in percentage). A dotted grid line was added to show the linear relation.

Doft et al and Woo et al observed that delaying treatment resulted in longer treatment duration.32,39 If initiated in the first week of life, treatment duration can be reduced from 6–8 weeks to 2 weeks or less, according to Doft et al and Matic et al 32,34 Breastfeeding is believed to prolong the ideal treatment interval, due to increased pliability of cartilage tissue. Chan et al, however, found no significant difference.30

Assessment of Results

In some cases, clinicians were independent28,30,37 or blinded.31 Treatment largely depended on subjective assessment due to a lack of objective tools.17,39 Byrd et al, Doft et al, and Van Wijk et al tried to implement an additional objective method of assessment by using a ruler to measure prominence.6,32,37 The grading moment varied. Most of the studies assessed the results immediately after treatment and at follow-up. Schratt et al, however, graded patients 2 years after treatment completion, while Chan et al graded patients 6 months after treatment.30,36 Doft et al 32 did not clarify the moment of assessment. In all studies, the majority of patients reached successful results. Two studies reached a relatively low score.29,37 Mohammadi et al believed low adherence to treatment guidelines and late presentation to be the cause of the low success rate.29 Van Wijk et al blamed late initiation of treatment due to ignorance.37 In most cases, parents are inclined to give higher ratings after treatment of the ear(s) of their child than clinicians (Table 3).

Treatability of Different Anomalies

Prominent ears showed most difficult to correct.6,29,31,35,37 (Tables 3, 5). This could be attributable to them being overlooked, an unnoticed conchal crus, or genetic predisposition.6,31. Van Wijk et al showed symmetric results in treatment of bilateral prominence, adding to the genetic theory. Treatment of prominent ears is still considered useful, as ear shape would be optimized for surgical correction.31. The number of deformities posed another difficulty in treatment. Daniali et al reported more than a single deformity in 102 ears and 91 ears having a mixed deformity. Only 88% of mixed deformities had a successful outcome, whilst single deformities showed a success rate of 97%.31 Byrd et al, Chang et al and Zhang et al mentioned “mixed” deformities as being difficult to treat.6,28,40. Due to the different anomalies varying in severity, sometimes only one type of anomaly is treated while the other is overlooked.

Table 5.

Rate of Satisfactory Improvement per Ear Anomaly

| Ear Anomaly | Rate of Satisfactory Improvement (%) |

|---|---|

| Cryptotia | 100 |

| Cup ears | 100 |

| Lop ears | 100 |

| Stahl’s ears | 98.3 |

| Helical rim | 96.3 |

| Conchal crus | 95.1 |

| Lidding ears | 94.9 |

| Constricted | 93.4 |

| Prominent | 80.4 |

Two articles reported on the treatment of malformations,30,31, including constriction and cryptotia as malformations. Chan et al showed that the success rate of treatment is lower in malformations than in deformations, but stated that parents were more inclined to opt for ear molding despite this, due to malformations appearing more severe. Daniali et al measured a significant improvement for treated malformations (P < 0.01). They also stated that even in the case of severe constriction, results of ear molding were still better than the contours after surgical repair. Mohammadi et al did not find a significant difference in duration of treatment between different ear anomalies and results.29

Complications

No severe complications (Table 2) were mentioned. Minor side effects occurred with an average of 9.7%–11%, consisting of pressure marks and irritation in the periauricular area.

Chan et al showed one of the highest rates of complications (46%),30 attributing this to the warm and humid climate of Singapore. A correlation was found between age and occurrence rate of complications (22.1 days versus 10.6 days, P = 0.037). This was attributed to the immune system becoming more hyperreactive with age and progressive hardening of the cartilage, making ears more prone to dermatitis and pressure ulcers, respectively.30

Most complications resolved spontaneously. Other cases had to be conservatively or topically treated6,30,32,36 or treatment was (temporarily) stopped.28,32,36 Daniali et al noticed more complications in malformations than in deformations.31

Recurrence

The exact amount of recurrence (Table 2) is unknown due to unilaterality or bilaterality of recurrence not always being specified, such as in Schratt et al36 The average recurrence rate is therefore a range of 7.0%–8.4%. The highest score only concerned prominent ears,33, which was echoed by other articles and attributed to family history and age at the initiation of treatment.6,38 Doft et al added that prominence due to an increased conchal-mastoid angle may develop during the 3rd to 4th month of life.32

Control Groups

Byrd et al and Woo et al mentioned that 30% of congenital ear anomalies self-correct and believes 15%–20% of all newborns to be possible candidates for ear molding.6,17

A control group, provided by Vincent et al, showed a complete spontaneous correction in 9% of cases, a partial correction in 19%, and no correction in 62% of cases.38

Discussion

This literature analysis shows ear molding to be an effective method to treat congenital ear anomalies. The main issue noticed in our analysis is the lack of consensus, as mentioned by Van Wijk et al2 Although there are speculations in regard to treatment material, duration, category of ear anomaly, and age at initiation, all studies had a different set-up, based on different literature references. Early diagnosis and treatment have been advised in earlier literature.24,41,42 Multiple articles in our review have echoed this. It is theorized that treatment during the neonatal period is the most effective due to maternal estrogen still present in the neonatal circulation, which would make the ear more pliable.43–46 Some articles, however, have concluded molding to be effective up until an older age, countering this theory.47–51 Another issue without consensus is a delay in ear molding treatment to allow for spontaneous correction to occur. Self-correction rates differ greatly between different study populations, varying from 0%52 to 84%,53 which might depend on ethnicity or type of ear anomaly.53

Although consensus has been lacking in regard to topics discussed above, treatment results have been very good, exceeding the success rate of otoplasty40 and therefore partially obviating otoplasty as treatment. Consensus may be useful for treatment protocol but does not necessarily benefit the success rate of treatment. Outcome assessment is often based on subjectivity. With a standardized treatment, duration and initiation could be off. Consensus is an admirable and often desirable concept, but it would be unwise to let it get in the way of optimal treatment. Furthermore, up until now, there have been no randomized controlled trials, which makes it difficult to compare treatment populations and reach consensus.

One of the difficulties faced in reviewing the literature is the different terminology used for different congenital ear anomalies. Cryptotia/constricted ears and lop/lidding ears were anomalies seen as either malformation or deformation. Therefore, a distinction in results was made in some of the articles, but not in others, which might have affected results. A method to differentiate was described by Porter et al,3 who uses digital pressure to create a normal ear shape. If this is not possible, this indicates a chondro-cutaneous defect, thus malformation. This might be a useful method to use in the future as a consensus.

Vincent et al38 refrained from most of the common terminology and instead named the affected anatomical structures. Lastly, prominence may occur during the first year of life due to lying supine or may be related to ear muscle development.8,10,32,54 The recurrence might therefore not be related to treatment, but rather to environmental and genetic factors.

Limitations of this study are the non-systematic method of review, which leads to inability to formulate concrete statements regarding the uses of ear molding. Another limitation was the design of the reviewed studies, as they differ between prospective and retrospective studies. No randomized clinical trials were available.

Future Possibilities

Research on the effect of estrogen injections into ear cartilage has been conducted using rabbits.55,56 This showed increased moldability of the auricle, therefore possibly prolonging the time frame for effective molding. Further research is necessary to assess its applicability in humans, and is therefore warranted. The effect of breastfeeding on the pliability of neonatal ears could also be studied more thoroughly. Although it has been suggested by Tan et al that the treatment interval may increase due to breastfeeding increasing estrogen levels, there is little data available on the subject.30,57

Furthermore, the availability of an objective ear-shape evaluation would be desirable. Although some articles6,32,37 tried implementing helical-mastoid distance to objectify assessment of prominent ears, this measurement has proved to vary between populations and not be applicable to other anomalies.58 Zhao et al tried to find a method of objectification through digital imaging of the ear, comparing the proportions of the ear to the EarWell Infant Corrective System standard.59 Another concept with possibilities for the treatment of ear anomalies is the concept of screening. Petersson et al35 looked into the training of audiologists and audiology technicians, who often visit neonates in the first week to test hearing. By implementing screening at an early stage of life, treatment may be initiated early, leading to a shorter duration of treatment and possibly better results.

Conclusions

Ear molding seems to be an efficient technique to fully correct or improve congenital ear anomalies in neonates. Although no consensus is found about different aspects of treatment, the subjective assessment of the appearance of the ear after treatment seems very good. Furthermore, ear molding seems to have no lasting negative complications or implications and has a relatively low recurrence rate.

Footnotes

Published online 30 November 2020.

Disclosure: Drs. Feijen is a subdistributor of the Earwell Infant Corrective System in the Netherlands. She is not paid for this position, nor has she received any financial aid for writing this article. This disclosure only concerns the use of the specific non-operative treatment method for congenital ear anomalies in children in the affiliated work location. All the other authors have no financial information to disclose. No funding was received for this article.

Drs. Feijen and van Cruchten contributed equally to the article and are both to be considered as the first author.

References

- 1.Schultz K, Guillen D, Maricevich RS. Newborn ear deformities: early recognition and novel nonoperative techniques. Semin Plast Surg. 2017;31:141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Wijk MP, Breugem CC, Kon M. Non-surgical correction of congenital deformities of the auricle: a systematic review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:727–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Porter CJ, Tan ST. Congenital auricular anomalies: topographic anatomy, embryology, classification, and treatment strategies. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;115:1701–1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiumariello S, Del Torto G, Guarro G, et al. The role of plastic surgeon in complex cephalic malformations. Our experience. Ann Ital Chir. 2014;85:166–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spinelli HM. Congenital ear deformities. Pediatr Rev. 1993;14:473–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byrd HS, Langevin CJ, Ghidoni LA. Ear molding in newborn infants with auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1191–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CS, Bartlett SP. Deformations of the ear and their nonsurgical correction. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2019;58:798–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yotsuyanagi T, Yamauchi M, Yamashita K, et al. Abnormality of auricular muscles in congenital auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:78e–88e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yotsuyanagi T, Nihei Y, Shinmyo Y, et al. Stahl’s ear caused by an abnormal intrinsic auricular muscle. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:171–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guyuron B, DeLuca L. Ear projection and the posterior auricular muscle insertion. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:457–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luquetti DV, Leoncini E, Mastroiacovo P. Microtia-anotia: a global review of prevalence rates. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2011;91:813–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lennon C, Chinnadurai S. Nonsurgical management of congenital auricular anomalies. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018;26:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindford AJ, Hettiaratchy S, Schonauer F. Postpartum splinting of ear deformities. BMJ. 2007;334:366–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuo K, Hirose T, Tomono T, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in the early neonate: a preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:38–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith W, Toye J, Reid A, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital ear abnormalities in the newborn: case series. Paediatr Child Health. 2005;10:327–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ullmann Y, Blazer S, Ramon Y, et al. Early nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:907–913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woo JE, Park YH, Park EJ, et al. Effectiveness of ear splint therapy for ear deformities. Ann Rehabil Med. 2017;41:138–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bradbury ET, Hewison J, Timmons MJ. Psychological and social outcome of prominent ear correction in children. Br J Plast Surg. 1992;45:97–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horlock N, Vögelin E, Bradbury ET, et al. Psychosocial outcome of patients after ear reconstruction: a retrospective study of 62 patients. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;54:517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calonge WM, Sinna R, Dobreanu C, et al. [Neonatal molding for minor deformities of auricular cartilage: a simple method]. Arch Pediatr. 2011;18:349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farkas LG, Posnick JC, Hreczko Anthropometric growth study of the ear. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 1992;29:324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Limandjaja GC, Breugem CC, Mink van der Molen AB, et al. Complications of otoplasty: a literature review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naumann A. Otoplasty – techniques, characteristics and risks. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;6:Doc04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown FE, Colen LB, Addante RR, et al. Correction of congenital auricular deformities by splinting in the neonatal period. Pediatrics. 1986;78:406–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurozumi N, Ono S, Ishida H. Non-surgical correction of a congenital lop ear deformity by splinting with Reston foam. Br J Plast Surg. 1982;35:181–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakajima T, Yoshimura Y, Kami T. Surgical and conservative repair of Stahl’s ear. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984;8:101–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anstadt EE, Johns DN, Kwok AC, et al. Neonatal ear molding: timing and technique. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20152831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang CS, Bartlett SP. A simplified nonsurgical method for the correction of neonatal deformational auricular anomalies. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohammadi AA, Imani MT, Kardeh S, et al. Non-surgical management of congenital auricular deformities. World J Plast Surg. 2016;5:139–147. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan SLS, Lim GJS, Por YC, et al. Efficacy of ear molding in infants using the EarWell infant correction system and factors affecting outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:648e–658e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daniali LN, Rezzadeh K, Shell C, et al. Classification of newborn ear malformations and their treatment with the EarWell infant ear correction system. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:681–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Doft MA, Goodkind AB, Diamond S, et al. The newborn butterfly project: a shortened treatment protocol for ear molding. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:577e–583e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leonardi A, Bianca C, Basile E, et al. Neonatal molding in deformational auricolar anomalies. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:1554–1558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matic DB, Boyd KU. Nonsurgical correction of Stahl’s deformity: an inexpensive, short-term, reproducible method of splinting. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:183e–185e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petersson RS, Recker CA, Martin JR, et al. Identification of congenital auricular deformities during newborn hearing screening allows for non-surgical correction: a Mayo Clinic pilot study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:1406–1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schratt J, Kuegler P, Binter A, et al. [Non-invasive correction of congenital ear deformities with the EarWell correction system: a prospective study]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2020;52:350–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Wijk MP, Breugem CC, Kon M. A prospective study on non-surgical correction of protruding ears: the importance of early treatment. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:54–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vincent PL, Voulliaume D, Coudert A, et al. [Congenital auricular anomalies: early non-surgical correction by splinting]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2019;64:334–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woo T, Kim YS, Roh TS, et al. Correction of congenital auricular deformities using the ear-molding technique. Arch Plast Surg. 2016;43:512–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang JL, Li CL, Fu YY, et al. Newborn ear defomities and their treatment efficiency with Earwell infant ear correction system in China. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;124:129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan ST, Abramson DL, MacDonald DM, et al. Molding therapy for infants with deformational auricular anomalies. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;38:263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan ST, Shibu M, Gault DT. A splint for correction of congenital ear deformities. Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47:575–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hascall VC, Heinegård D. Aggregation of cartilage proteoglycans. II. Oligosaccharide competitors of the proteoglycan-hyaluronic acid interaction. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4242–4249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kenny FM, Angsusingha K, Stinson D, et al. Unconjugated estrogens in the perinatal period. Pediatr Res. 1973;7:826–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.SCHIFF M, BURN HF. The effect of intravenous estrogens on ground substance. Arch Otolaryngol. 1961;73:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uzuka M, Nakajima K, Ohta S, et al. Induction of hyaluronic acid synthetase by estrogen in the mouse skin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;673:387–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorribes MM, Tos M. Nonsurgical treatment of prominent ears with the Auri method. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:1369–1376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yotsuyanagi T. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in children older than early neonates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114:190–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yotsuyanagi T, Yokoi K, Sawada Y. Nonsurgical treatment of various auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29:327–32, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muraoka M, Nakai Y, Ohashi Y, et al. Tape attachment therapy for correction of congenital malformations of the auricle: clinical and experimental studies. Laryngoscope. 1985;95:167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yotsuyanagi T, Yokoi K, Urushidate S, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in children older than early neonates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101:907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Merlob P, Eshel Y, Mor N. Splinting therapy for congenital auricular deformities with the use of soft material. J Perinatol. 1995;15:293–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsuo K, Hayashi R, Kiyono M, et al. Nonsurgical correction of congenital auricular deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;17:383–395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tan ST, Gault DT. When do ears become prominent? Br J Plast Surg. 1994;47:573–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cottler PS, McLeod MD, Payton JI, et al. Plasticity of auricular cartilage in response to hormone therapy. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;786S Suppl 5S311–S314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.THOMAS L. Reversible collapse of rabbit ears after intravenous papain, and prevention of recovery by cortisone. J Exp Med. 1956;104:245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan S, Wright A, Hemphill A, et al. Correction of deformational auricular anomalies by moulding–results of a fast-track service. N Z Med J. 2003;116:U584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao H, Lin G, Seong YH, et al. Anthropometric research of congenital auricular deformities for newborns. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:1176–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao H, Ma L, Qi X, et al. A morphometric study of the newborn ear and an analysis of factors related to congenital auricular deformities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]