Abstract

Objective

To examine proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) prescribing patterns over a 29-year period by quantifying annual prevalence and prescribing intensity over time.

Design

Population-based cross-sectional study.

Setting

More than 700 general practices contributing data to the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD).

Participants

Within a cohort of 14 242 329 patients registered in the CPRD, 3 027 383 patients were prescribed at least one PPI or H2RA from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2018.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Annual prescription rates were estimated by dividing the number of patients prescribed a PPI or H2RA by the total CPRD population. Change in prescribing intensity (number of prescriptions per year divided by person-years of follow-up) was calculated using negative binomial regression.

Results

From 1990 to 2018, 21.3% of the CPRD population was exposed to at least one acid suppressant drug. During that period, PPI prevalence increased from 0.2% to 14.2%, while H2RA prevalence remained low (range: 1.2%–3.4%). Yearly prescribing intensity to PPIs increased during the first 15 years of the study period but remained relatively constant for the remainder of the study period. In contrast, yearly prescribing intensity of H2RAs decreased from 1990 to 2009 but has begun to slightly increase over the past 5 years.

Conclusions

While PPI prevalence has been increasing over time, its prescribing intensity has recently plateaued. Notwithstanding their efficacy, PPIs are associated with a number of adverse effects not attributed to H2RAs, whose prescribing intensity has begun to increase. Thus, H2RAs remain a valuable treatment option for individuals with gastric conditions.

Keywords: epidemiology, gastroduodenal disease, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Largest and most comprehensive study to date describing trends of acid suppressant drug prescribing over a 29-year period.

Large sample size allows detailed description of trends by age group, sex and indication.

Prescriptions in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink are issued by general practitioners, so it was not possible to assess patient adherence.

We did not have data on prescriptions recorded in hospital, by specialists, or from over the counter.

Introduction

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are acid suppressant drugs used in the management of gastric conditions, including peptic ulcer disease and gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.1 2 The first H2RA, cimetidine, was approved for use in the UK in 1976, while omeprazole, a PPI, was later approved in 1989.3 4 While both drug classes have been used for over three decades, PPIs have been shown to have superior efficacy in reducing stomach acid compared with H2RAs1 and are thus more favourably used. Nonetheless, both drug classes are among the top 25 most prescribed medications in the hospital setting in the UK.5

In recent years, there have been concerns about the increasing uptake of PPIs, with emerging evidence that they are being prescribed to individuals without an evidence-based indication or for longer durations than necessary.6–10 Indeed, the number of individuals using PPIs has been increasing significantly since their introduction in 1989.11 In England alone, more than 50 million PPI prescriptions were dispensed in 2015.3 In contrast, there is limited information on the older drug class, H2RAs, with regard to their prescribing patterns in recent years. It is also less well known whether H2RAs are also being overprescribed in a similar fashion to PPIs.

While PPIs are generally well tolerated and perceived to have an excellent safety profile,1 9 recent evidence suggests that long-term use, beyond the recommended 4–8 weeks duration for most conditions, may be associated with certain adverse health outcomes. These include enteric infections such as Clostridium difficile, acute interstitial nephritis, hypomagnesaemia and increased intestinal colonisation with multidrug-resistant organisms.3 12–15 Given their widespread use and these potential adverse effects, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommended new treatment guidelines for PPI use in primary care in 2014.16 These new guidelines emphasise an annual review to determine ongoing need, and to use the lowest dose of PPI on an as-needed basis for symptom relief.16 Treatment with H2RAs is recommended when patients are unresponsive to PPIs.16 Prescribing patterns of PPIs have not been evaluated since the publication of these guidelines, and it remains unknown if the guidelines had an impact on the uptake of H2RAs. Thus, the objective of this utilisation study was to determine the prescribing patterns of PPIs and H2RAs in UK primary care over a 29-year period.

Methods

Data source

This study was conducted using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), a large primary care database with records of over 15 million patients, shown to be well representative of the general UK population.17 18 The CPRD contains information on demographics, diagnoses and procedures,19 and prescriptions issued by general practitioners are recorded using the British National Formulary. The data are audited regularly, and diagnoses recorded in the CPRD have been extensively validated.20 21

Study population

Using the CPRD, we identified a cohort of patients who were registered with a general practitioner from 1 January 1990 to 31 December 2018. We did not impose any age restrictions to allow the evaluation of PPI and H2RA prescribing trends in both paediatric and adult populations. Patients were followed from the latest date at which their practice started contributing data to the CPRD, their personal date of registration with their general practice, or the start of the study period (1 January 1990). Follow-up ended at the earliest date at which their practice stopped contributing data to the CPRD, their personal end of registration with their general practice, or the end of the study period (31 December 2018).

Exposure definition

We identified all PPIs and H2RAs prescriptions within the study period using the British National Formulary (online supplemental tables 1 and 2). This included five PPI types (omeprazole, esomeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole) and four H2RA types (ranitidine, cimetidine, famotidine and nizatidine). Prescription duration was calculated using the number of days’ supply recorded in the CPRD. If this value was not recorded, we divided the prescription quantity by the numeric daily dose to ascertain duration. If none of these variables were recorded, we used the mode of the prescription duration for PPIs and H2RAs, separately.

bmjopen-2020-041529supp001.pdf (458.9KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

Prevalence

For each calendar year, we calculated the prevalence of PPIs and H2RAs, separately. The numerator for these prescription rates was the number of individuals receiving at least one acid suppressant drug in a given year (PPI and H2RA prescriptions were considered separately). The denominator was the total number of patients registered in the CPRD in a given year. Thus, prevalence was calculated per year by dividing the number of prescriptions over the number of patients in the CPRD for each calendar year between 1990 and 2018. Secondary analyses were conducted to determine prevalence among certain subgroups. Specifically, the rates were stratified by age (<18, 18–39, 40–59 and ≥60), sex and individual drug type.

Prevalence was also calculated among new users only by restricting the population to individuals receiving their first acid suppressant prescription (ie, PPI or H2RA) within the study period. To determine new use, individuals prescribed acid suppressants were required to have at least 1 year of medical history in the CPRD prior to their first prescription. Similarly, patients in the CPRD were required to have at least 1 year of follow-up to contribute to the denominator. Individuals coprescribed a PPI and H2RA as their first prescription were excluded from this analysis. Thus, prevalence was calculated for each year between 1991 and 2018 in new users and stratified according to the same variables described above.

Indications for use

Indications for use among new users (ie, first of either a PPI or H2RA prescription within the study period) was inferred using Read codes recorded at any time prior to the first prescription. Indications were classified as evidence based (dyspepsia, gastroprotection, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, Helicobacter pylori infection, Barrett’s oesophagus and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), non-evidence-based gastroprotection, off-label (stomach pain and gastritis or duodenitis), and no recorded indication.2 To define individuals using acid suppressant drugs for gastroprotection, we considered individuals prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or dual antiplatelet therapy within 90 days prior to their first PPI or H2RA prescription. To be classified as evidence-based gastroprotection, these patients additionally required at least one of the following risk factors (age ≥60, history of bleed or ulcer, or concomitant use of anticoagulants, antiplatelets, corticosteroids).2 All individuals with a coprescription for NSAIDs or dual antiplatelet therapy, but without a risk factor, were assumed to be using acid suppressants for non-evidence based gastroprotection. In secondary analyses, we stratified indications by sex and illustrated the incidence of indications over time by dividing the number of patients with each indication per year by the population in the CPRD with at least 1 year of follow-up.

Prescribing intensity

For each calendar year, we calculated the prescribing intensity of PPI and H2RA use, separately. The numerator for these rates was the number of prescriptions received for either acid suppressant drug in a given year (prescriptions longer than 30 days were converted into 30-day equivalents (eg, one 90-day prescription was equivalent to three 30-day prescriptions), for a maximum of 12 prescriptions per year). The denominator for these rates was the total person-years of follow-up that were contributed by drug users in a given year. Thus, yearly prescribing incidence rates were calculated by dividing the number of prescriptions over the person-years of follow-up for each year between 1990 and 2018. To determine whether prescribing intensity changed during the study period, we stratified the study period by 5-year intervals and estimated incidence rate ratios with 95% CIs using negative binomial regression, with log of follow-up time included as an offset variable.

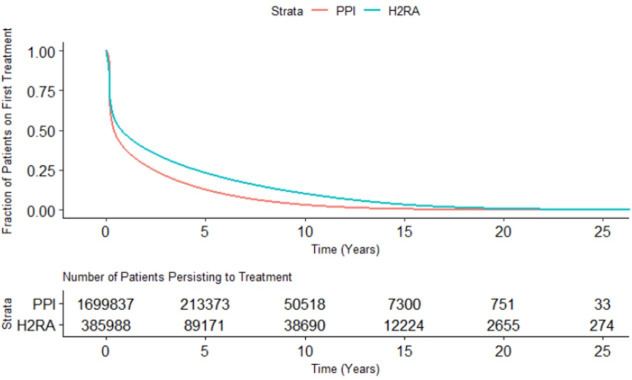

Persistence

As there is some evidence that PPIs are being used for inappropriate durations,6–10 but there is limited evidence on H2RA use, we examined persistence to both drugs by calculating the cumulative incidence of discontinuation in new users of PPIs and H2RAs. Time to discontinuation was defined as the time from the first prescription of an acid suppressant drug to the end of the first treatment episode. Exposure was considered continuous if the duration of one prescription overlapped with the start of the subsequent prescription, allowing for a 30-day grace period. The end of a treatment episode was defined as the first of: (1) a treatment gap exceeding 30 days, (2) a switch from PPI to H2RA or vice versa, or (3) administrative censoring (ie, if a practice stopped contributing data to the CPRD, a patient was no longer registered with their general practice, or if the study period ended). The length of the grace period was changed to 7 and 60 days in a sensitivity analysis. We used Kaplan-Meier curves to illustrate the cumulative incidence of discontinuation of PPIs and H2RAs, separately, as a function of duration of use to show the cumulative probability of persisting to the first treatment episode. In a secondary analysis, we described the cumulative incidence of discontinuation according to indications for use (evidence-based, non-evidence-based gastroprotection, off-label and no recorded indication). All analyses described above were conducted with SAS V.9.4 (SAS institute) and R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Patient involvement

We did not include patients as study participants, as our study involved the use of secondary data. Patients were not involved in the design or implementation of the study. We do not plan to involve patients in the dissemination of results, nor will we disseminate results directly to patients.

Results

Within a cohort of 14 242 329 patients (51.4% female) registered in the CPRD, 3 027 383 (21.3%) patients were prescribed at least one PPI or H2RA during the study period, corresponding to 58 926 373 and 9 386 908 prescriptions, respectively. Among patients prescribed an acid suppressant drug, there were 1 654 323 (54.7%) females and 2 920 176 (96.5%) adults (at least 18 years old). Throughout follow-up, there were 2 714 785 (19.1%) individuals prescribed at least one PPI, 855 248 (6.0%) individuals prescribed at least one H2RA, and 542 650 (3.8%) individuals prescribed both drug classes.

Among patients newly prescribed an acid suppressant drug (n=2 085 825), 81.5% (n=1 699 837) were initially prescribed a PPI, while 18.5% (n=385 988) were initially prescribed a H2RA. Table 1 presents the characteristics of these users at the time of their first prescription. PPI users were slightly older than H2RA users at the time of initial prescription, but there were no sex differences between the two groups. Only 43.5% and 45.3% of PPI and H2RA users, respectively, had an evidence-based indication for use, with dyspepsia being the most common recorded indication. Non-evidence-based gastroprotection was more common in PPI users (21.4%) than the H2RA users (13.3%). About one in five PPI and H2RA users did not have a recorded indication for use. When stratifying indications by sex, females were more commonly prescribed PPIs for off-label indications compared with males (online supplemental table 3). The incidence of indications for acid suppressant use was relatively consistent over time, with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease the only evidence-based indication that slightly increased over follow-up (online supplemental figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals newly prescribed proton pump inhibitors (PPI) and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RA)

| Characteristic | PPI† | H2RA† |

| Total | 1 699 837 | 385 988 |

| Male, n (%) | 768 781 (45.2) | 167 683 (43.4) |

| Age, years (mean, SD) | 53.4 (18.9) | 48.6 (21.1) |

| Age group, n (%) | ||

| <18 years | 34 590 (2.0) | 30 057 (7.8) |

| 18–39 years | 393 052 (23.1) | 109 205 (28.3) |

| 40–59 years | 596 469 (35.1) | 116 174 (30.1) |

| ≥60 years | 675 726 (39.8) | 130 552 (33.8) |

| Evidence-based indication, n (%)* | 740 177 (43.5) | 174 836 (45.3) |

| Dyspepsia | 316 831 | 112 737 |

| Gastroprotection | 288 360 | 41 350 |

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease | 158 405 | 33 480 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 50 239 | 14 453 |

| Helicobacter pylori infection | 41 430 | 2526 |

| Barrett’s oesophagus | 4180 | 137 |

| Zollinger-Ellison syndrome | 24 | 5 |

| Non-evidence based gastroprotection, n (%) | 363 992 (21.4) | 51 476 (13.3) |

| Off-label indication, n (%)* | 253 591 (14.9) | 72 431 (18.8) |

| Stomach pain | 231 715 | 64 188 |

| Gastritis or duodenitis | 35 908 | 13 096 |

| No recorded indication, n (%) | 342 077 (20.1) | 87 245 (22.6) |

| Reason for discontinuation† | ||

| Switch to other class | 43 988 (2.6) | 124 648 (32.3) |

| Treatment gap >30 days | 893 230 (52.5) | 122 928 (31.8) |

| Administrative censoring | 762 619 (44.9) | 138 412 (35.9) |

*Indication categories are not mutually exclusive.

†Median (IQR) duration of first treatment course for PPI users and H2RA users was 144 (59–870) days and 279 (61–1645) days, respectively.

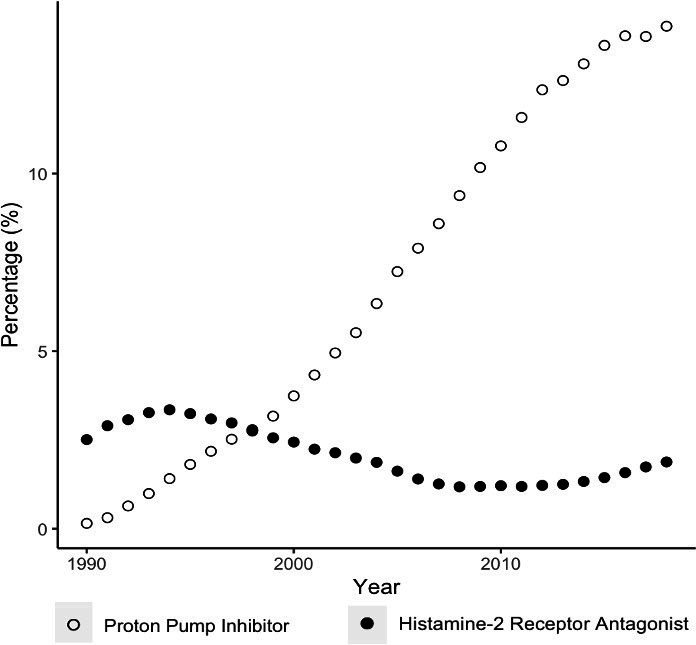

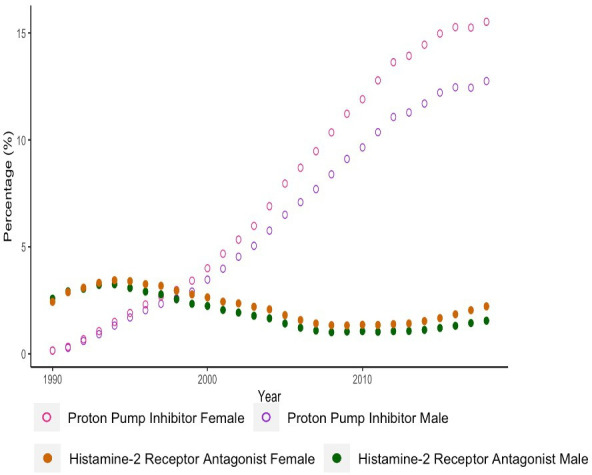

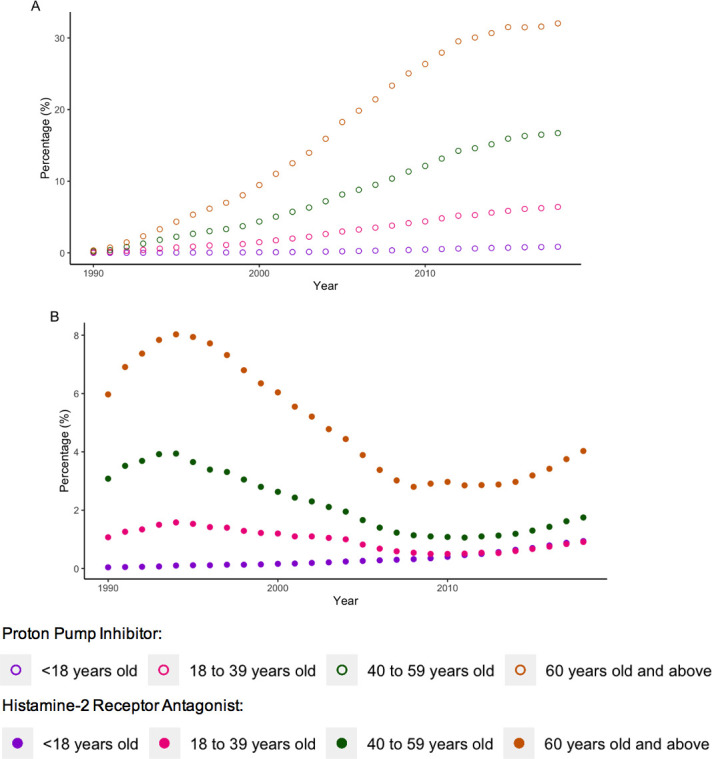

Figures 1–3 illustrate the overall, sex and age-stratified prevalence of PPI and H2RA, respectively. Throughout follow-up, PPI prevalence sharply increased from 0.2% in 1990 to 14.2% in 2018. In contrast, the prevalence of H2RAs remained consistently low throughout the study period (range: 1.2%–3.4%). PPIs were more commonly prescribed in females and both drug classes were more commonly prescribed in adults at least 60 years old. Overall and sex-stratified prevalence of use were similar among new users (online supplemental figures 2 and 3), though the prevalence of H2RA use among new users was consistent across all age categories over the past decade (online supplemental figure 4). Omeprazole was the most commonly prescribed PPI during the study period, followed by lansoprazole (online supplemental figure 5). At the beginning of the study period, ranitidine and cimetidine were both frequently prescribed, though after 2004 ranitidine was almost exclusively the only H2RA prescribed (online supplemental figure 5).

Figure 1.

Overall prevalence of proton pump inhibitor and histamine-2 receptor antagonist use.

Figure 2.

Sex-stratified prevalence of proton pump inhibitor and histamine-2 receptor antagonist use.

Figure 3.

Age-stratified prevalence of (A) proton pump inhibitor use and (B) histamine-2 receptor antagonist use.

Throughout the study period, the prescribing intensity of PPIs ranged from 0.07% in 1990, increasing to a peak intensity of 0.98% in 2012. In contrast, the prescribing intensity of H2RA use decreased over the study period from the highest intensity of 1.95% in 1990, to the lowest intensity of 0.08% in 2013 (online supplemental figure 6). PPI yearly prescribing intensity sharply increased during the first 5 years of the study period, moderately increased until 2004, after which prescribing intensity plateaued (online supplemental table 4). In contrast, H2RA yearly prescribing intensity decreased from 1990 to 2009, and has begun to increase slightly over the past 5 years.

Within new users of PPIs (n=1,699,837) the median duration of the first treatment course was 144 (IQR (IQR): 59–870) days. Reasons for discontinuation are presented in table 1, which illustrates that the majority of PPI users (52.5%) discontinued their first treatment course due to a gap of at least 30 days between prescriptions. Overall, a small percentage (2.6%) of PPI users discontinued their original treatment due to a switch to H2RAs. In contrast, the median duration of the first H2RA treatment course among new H2RA users (n=3 85 988) was 279 (IQR: 61–1645) days. Approximately one-third of H2RA users discontinued use due to each of the following: a treatment gap exceeding 30 days, administrative censoring, or because of a switch to a PPI. Online supplemental table 5 presents duration of treatment and reasons for discontinuation under alternate grace periods. When a grace period of 7 days was applied, the median (IQR) duration of PPI and H2RA use was 66 (36–560) and 149 (38–1479) days, respectively. When a grace period of 60 days was used, the median (IQR) duration of PPI use was 231 (89–1097) days, and H2RA use was 381 (91–1785) days. The reasons for discontinuation remained consistent when considering these alternate grace periods.

Figure 4 illustrates the time to discontinuation of both drug classes. While persistence to PPIs and H2RAs declined within the first year of use, 37.5% of PPI users and 46.9% of H2RA users persisted to their original treatment course beyond the 1 year recommended duration,16 and 12.6% of PPI users and 23.1% of H2RA users persisted to their original treatment course after 5 years. When examining persistence by indication, persistence to both PPIs and H2RAs was highest among patients with an off-label or no recorded indication for use (online supplemental figures 7 to 10).

Figure 4.

Persistence to original treatment course for proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) initiators.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive study conducted to date to examine prescribing patterns of both PPIs and H2RAs in the UK. Throughout the study period, 21.3% of the CPRD population received at least one prescription for an acid suppressant drug (PPI only: 19.1%, H2RA only: 6.0%, PPI and H2RA: 3.8%). The overall prevalence of PPI prescribing has increased from 1990 to 2018, while the prevalence of H2RA remained low. Yearly prescribing intensity to PPIs increased during the first 15 years of the study period but remained relatively consistent for the remainder of the study period. In contrast, yearly prescribing intensity of H2RAs decreased from 1990 to 2009 but has begun to increase over the past 5 years.

The overall high prevalence of PPI use in the UK is consistent with a utilisation study of PPIs using CPRD data, but whose follow-up period ended at the end of 2014.11 Importantly, our study further contextualises the landscape of prescribing acid suppressant drugs by also describing trends of H2RA use. While H2RAs are considerably less popular than PPIs, we observed almost 10 million prescriptions within our study period, suggesting that their use has not been completely supplanted by PPIs. While use of H2RAs may be associated with delirium and acute interstitial nephritis,22 23 they are generally well tolerated. Indeed, H2RAs are more commonly associated with mild adverse effects like headache and constipation,22 not the serious adverse effects associated with use of PPIs.3 12–15 Thus, H2RAs continue to represent an important treatment option for individuals with gastric conditions. Finally, while the prevalence of acid suppressant drugs is consistent with the market availability of both drug classes, it cannot be explained by an increase in the incidence of indications for PPIs and H2RAs, which have been relatively consistent over time.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe contemporary prescribing practices following the most recent NICE recommendations in 2014.16 Given that H2RA prescribing intensity has begun to increase following publication of the guidelines, this may suggest a gradual shift in prescribing to favour H2RAs. Indeed, the guidelines recommend treatment with PPIs at the lowest dose for the shortest amount of time, and thus may favour longer-term H2RA prescriptions. Future studies should investigate the impact of the NICE recommendations more thoroughly.

Our study demonstrated a sex difference among PPI prescribing patterns and an age difference among prescribing patterns of both PPIs and H2RAs; women were more frequently prescribed PPIs and adults at least 60 years old were more frequently prescribed both drug classes. As women are more likely to report symptoms of gastric reflux than men,24 this would lead to more frequent prescribing of acid suppressant drugs to manage these symptoms. Moreover, dyspepsia, the most common evidence-based indication, was more commonly diagnosed in women. The age difference may be explained by the increasing incidence of dyspepsia with age,25 or through an increased need for gastroprotection in the elderly, whereby patients over the age of 60 who are prescribed NSAIDs or dual antiplatelet therapy are indicated to receive an acid suppressant drug for gastroprotection.2

In recent years, there have been concerns about the increasing inappropriate use of PPIs.6 7 Indeed, between 40% and 55% of primary care patients in the USA and the UK do not have an evidence-based indication for long-term PPI use.26 27 This is particularly relevant as PPIs are associated with a number of serious adverse events including enteric infections and hypomagneasemia.3 12–15While there is some evidence that use of PPIs may also be associated with dementia, pneumonia and gastric cancer,3 28 not all studies have confirmed these associations.29 30 Our study adds to the growing literature surrounding inappropriate use, as we illustrated that these issues extend to H2RA users as well. Indeed, a little over 20% of PPI and H2RA users have no recorded indication for use, while 37.5% and 46.9%, respectively, remain on their original treatment course at 1 year of follow-up, despite recommendations to limit use to 4–8 weeks at a time for symptomatic treatment of gastro-oesophageal disease and peptic ulcer disease.16 As illustrated by the stratified persistence patterns, a significant portion of this high persistence is among patients with an off-label, or no recorded indication for use. This provides further evidence on the inappropriate use of acid suppressant drugs.

This study has several strengths. To our knowledge, this is the largest and most comprehensive study to date describing the trends of acid suppressant drugs over time. Our study describes the use of PPIs and H2RAs over a 29-year period, which is almost the entirety of PPI market availability. Importantly, we provide new data on the recent use of H2RAs, which indicates that this drug class is gaining favour among general practitioners. Second, the data we used in this study has been well validated,20 21 and shown to be representative of the UK general population.17 18 Finally, the large sample size allowed us to provide detailed information of trends by age group and sex, and investigate use among rare indications, including Barrett’s oesophagus and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

This study also has some limitations. Prescriptions recorded in the CPRD are those issued by general practitioners, and thus, it is not possible to assess patient adherence or determine if a patient filled a prescription. While this may slightly affect the estimate of cumulative incidence of discontinuation, the rest of our analyses focus on physician prescribing trends. These would not be influenced by patient adherence and are a better indicator of whether physicians are following guidelines. Second, it is possible that the trends reported in this study are underestimated, as we do not have information on prescriptions recorded in hospital or by specialists. However, this is unlikely to lead to substantial underestimation, as general practitioners in the UK are responsible for long-term patient care.31 However, it remains possible that the lack of hospitalisation data led to the underestimation of patients requiring short-term treatment with acid suppressant drugs. Third, this study uses data from the UK only, and as such, it is possible that prescribing trends will differ in alternate settings. Finally, this study did not include data on over the counter use of medications. Thus, the relatively high prevalence of patients exposed to acid suppressant drugs (21.3%) would be even higher if over the counter PPI and H2RA usage was considered. Lack of over the counter data may have led to the underestimation of patients using acid suppressant drugs for gastroprotection, as it is possible that some patients receive an NSAID prescription over the counter.

This study demonstrates that while prevalence of PPI use has increased with time, its prescribing intensity has plateaued over the past 15 years. In contrast, while prevalence of H2RAs was consistently low throughout the study period, its prescribing intensity has begun to slightly increase over the past 5 years. Given that PPIs are associated certain adverse effects not attributed to H2RAs, H2RAs remain a valuable treatment option for individuals with gastric conditions.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @DevinAbrahami, @DrEmilyMcD, @mirschnitzer, @LaurentAzoulay0

Contributors: DA, EGM, MS and LA conceived and designed the study. LA acquired the data. DA and LA did the statistical analyses. DA, EGM, MS and LA analysed and interpreted the data. DA wrote the manuscript and EGM, MS and LA critically revised the manuscript. LA supervised the study and is the guarantor. DA, EGM, MS and LA approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for the accuracy of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by a Foundation Scheme Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-143328). DA is the recipient of a Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. EGM holds a Chercheur-Clinicien Junior 1 award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé. MS holds a New Investigator Salary Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and is the recipient of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research Canada Research Chair, Tier 2. LA holds a Chercheur-Boursier Senior award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé and is the recipient of a William Dawson Scholar Award from McGill University.

Disclaimer: The sponsor had no influence on design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee of the CPRD (protocol number 19_119RA) and by the Research Ethics Board of the Jewish General Hospital. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

References

- 1.Strand DS, Kim D, Peura DA. 25 years of proton pump inhibitors: a comprehensive review. Gut Liver 2017;11:27–37. 10.5009/gnl15502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benmassaoud A, McDonald EG, Lee TC. Potential harms of proton pump inhibitor therapy: rare adverse effects of commonly used drugs. CMAJ 2016;188:657–62. 10.1503/cmaj.150570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Connelly D. The development and safety of proton pump inhibitors. The Pharm J 2016;296. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molinder HK. The development of cimetidine: 1964-1976. a human story. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994;19:248–54. 10.1097/00004836-199410000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audi S, Burrage DR, Lonsdale DO, et al. . The 'top 100' drugs and classes in England: an updated 'starter formulary' for trainee prescribers. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84:2562–71. 10.1111/bcp.13709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh K, Kwan D, Marr P, et al. . Deprescribing in a family health team: a study of chronic proton pump inhibitor use. J Prim Health Care 2016;8:164–71. 10.1071/HC15946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katz MH. Failing the acid test: benefits of proton pump inhibitors may not justify the risks for many users. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:747–8. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prescribing PPIs. Drug Ther Bull 2017;55:117-120. 10.1136/dtb.2017.10.0541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, et al. . Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician 2017;63:354–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ 2008;336:2–3. 10.1136/bmj.39406.449456.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Othman F, Card TR, Crooks CJ. Proton pump inhibitor prescribing patterns in the UK: a primary care database study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2016;25:1079–87. 10.1002/pds.4043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nehra AK, Alexander JA, Loftus CG, et al. . Proton pump inhibitors: review of emerging concerns. Mayo Clin Proc 2018;93:240–6. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, George KC, Shang W-F, et al. . Proton-Pump inhibitors use, and risk of acute kidney injury: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017;11:1291–9. 10.2147/DDDT.S130568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonald EG, Milligan J, Frenette C. Continuous proton pump inhibitor therapy and the associated risk of recurrent Clostridium difficile InfectionPPI therapy and recurrent C difficile InfectionPPI therapy and recurrent C difficile infection. JAMA Internal Medicine 2015;175:784–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Willems RPJ, van Dijk K, Ket JCF, et al. . Evaluation of the association between gastric acid suppression and risk of intestinal colonization with multidrug-resistant microorganisms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:561–71. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gastro-Oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management National Institute for health and care excellence, 2014 [PubMed]

- 17.Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. . Data resource profile: clinical practice research Datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:827–36. 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolf A, Dedman D, Campbell J, et al. . Data resource profile: clinical practice research Datalink (CPRD) aurum. Int J Epidemiol 2019;48:1740 10.1093/ije/dyz034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Read codes United Kingdom National health service 2010. Available: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/research/umls/sourcereleasedocs/current/RCD/ [Accessed 2017].

- 20.Jick SS, Kaye JA, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C, et al. . Validity of the general practice research database. Pharmacotherapy 2003;23:686–9. 10.1592/phco.23.5.686.32205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrenson R, Williams T, Farmer R. Clinical information for research; the use of general practice databases. J Public Health 1999;21:299–304. 10.1093/pubmed/21.3.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nugent CC, Terrell JM. H2 blockers. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher AA, Le Couteur DG. Nephrotoxicity and hepatotoxicity of histamine H2 receptor antagonists. Drug Saf 2001;24:39–57. 10.2165/00002018-200124010-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim YS, Kim N, Kim GH. Sex and gender differences in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2016;22:575–88. 10.5056/jnm16138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Piessevaux H, De Winter B, Louis E, et al. . Dyspeptic symptoms in the general population: a factor and cluster analysis of symptom groupings. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2009;21:378–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01262.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heidelbaugh JJ, Goldberg KL, Inadomi JM. Magnitude and economic effect of overuse of antisecretory therapy in the ambulatory care setting. Am J Manag Care 2010;16:e228–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batuwitage BT, Kingham JGC, Morgan NE, et al. . Inappropriate prescribing of proton pump inhibitors in primary care. Postgrad Med J 2007;83:66–8. 10.1136/pgmj.2006.051151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wan Q-Y, Wu X-T, Li N, et al. . Long-Term proton pump inhibitors use and risk of gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of 926 386 participants. Gut 2019;68:762-764. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park S-K, Nam JH, Lee H, et al. . Beyond uncertainty: negative findings for the association between the use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of dementia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;34:2135–43. 10.1111/jgh.14745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. . Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, Multi-Year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology 2019;157:682–91. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahrens D, Behrens G, Himmel W, et al. . Appropriateness of proton pump inhibitor recommendations at hospital discharge and continuation in primary care. Int J Clin Pract 2012;66:767–73. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02973.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-041529supp001.pdf (458.9KB, pdf)