Abstract

Religion, a prominent factor among Black diasporic communities, influences their health outcomes. Given the increase in Black Caribbeans living in the United States, it is important to understand how religion’s function among different ethnic groups of Black Americans. We systematically reviewed four databases and included articles of any study design if they (a) focused on the religious experiences of emerging adults (18–29 years) identifying as Black Caribbean in the United States, in light of medical, public health, or mental health outcomes, and (b) were published before November 30, 2018. Study results contribute to future studies’ conceptualization and measurement of religion among Black Caribbean emerging adults.

Keywords: Religion, Religiosity, Health, Afro-Caribbean, Black Americans

Introduction

Numerous scholars recognize religion as a key social determinant of health (Hankerson et al. 2018; Idler 2014; Taylor et al. 2003). Largely viewed as having a longstanding and supportive role for Black diasporic communities in the USA, religion and religious institutions typically offer a wide range of practical, social, and civic resources—reflective of this, religious involvement is often conceptualized as multidimensional (Mouzon 2017). For example, some scholars categorize aspects of religious involvement into three categories: organizational religious involvement (i.e., religious service attendance), non-organizational religious involvement (i.e., praying along, reading sacred texts), and subjective religiosity (i.e., individual perceptions of self and religious beliefs) (Chatters 2000; Levin et al. 1995; Maselko et al. 2007; Skipper et al. 2018; Taylor et al. 1999; Taylor et al. 2011b). Taken together, these categories only begin to reflect the myriad of ways that religion and health may be inextricably linked, studied, and relevant for understanding Black American health trajectories.

With respect to health, numerous systematic reviews and assessments of religious involvement overwhelmingly support positive associations between various dimensions of religion and health among Black Americans (Ledford 2010; Moyer et al. 2014; Rew and Wong 2006; Taggart et al., 2018, 2019). For example, those reporting greater religious activity are less likely to engage in health prohibiting behaviors such as substance use and risky sexual behaviors than less religious counterparts (Billioux et al. 2014; Chatters 2000; Garcia et al. 2013; Hope et al. 2019a; Koenig et al. 2012). Religiously active individuals also report better psychosocial outcomes including lowered depressive symptomatology and an overall positive well-being (Cole-Lewis et al. 2016; Hope et al. 2017; Koenig et al. 2012; Mackenzie et al. 2000).

However, much of the literature on religion and health among Black Americans does not examine whether ethnic differences between Black populations have an effect on the associations between religion and health. Often, scholars use terms such as Black and African American interchangeably, a practice that negates the ethnic diversity present within the Black community in the United States. For example, Williams and Jackson (2000) emphasize that “an African American born and raised in the South, a Jamaican, a Haitian, a Kenyan, and an African American born in the Northeast are all Black, but they are likely to differ in terms of beliefs, behavior, and perhaps even physical functioning. Such variation within the Black population also may predict important diversity in health status” (1729). With this perspective, it is imperative to provide a brief overview of Black Caribbean experiences in the United States, paying special attention to religiosity and its connections to health.

Black Caribbeans living in the USA comprise the majority of Black immigrants (U.S. Census Bureau 2011; Kent 2007; Williams and Jackson 2000). They also represent a sizeable portion of Black Americans in major metropolitan areas. Their experiences of being Black American are further punctuated by the additional demands of being immigrants, increasing already heightened risks to health (Livingston et al. 2007). These challenges are also influenced by how immigrants navigate Blackness in the United States, where they are now in the minority within a racially antagonistic context. Within religious contexts, the immigrant aspect of Black Caribbean identities may further undergird religious involvement (Nguyen et al. 2016). Many Black Caribbeans participate in religious communities located in cultural enclaves (Waters 1999), and some may not seek community outside of those enclaves (Louis et al. 2017). In turn, this may increase their attachment to their culture and provide greater social capital and support (Hope et al. 2019b; Taylor et al. 2007b).

Although the scholarship on the experiences of Black Caribbeans in the United States of America continues to grow, the majority of that scholarship that explores health and religion, in general, has been conducted using the National Survey of American Life: Coping with Stress in the twenty-first century (NSAL) (Heeringa et al. 2004). The NSAL is nationally representative and assesses Black American adults’ psychological, psychiatric, and health outcomes, with surveyed respondents ranging in age from 18 to 91 years old (Jackson et al. 2004). As of May 2019, 446 studies using NSAL data have been published in peer-reviewed outlets. However, out of those studies, those that focus on religion and health for Black adults tend to focus on those older in age and elderly (Chatters et al. 2008). When emerging adults are included in NSAL studies, analyses tend to focus on adulthood, broadly (Chatters et al. 2011; Himle et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2011a). Consequently, this work does not tend to highlight the developmental characteristics that differentiate emerging adult religiosity and health as distinct from individuals in other stages of adulthood.

Religion and Health in the Context of Black Emerging Adulthood

Emerging adulthood occurs when individuals transition from adolescence to early adulthood. This developmental period roughly spans 18–25 years of age (Arnett 2000; Arnett and Mitra 2018; Nelson and Barry 2005), and some scholars acknowledge that it may also continue until age 29 (Arnett et al. 2014). Characterized by increased autonomy and preparation for adulthood roles, this stage also overlaps with a decline in organizational religious involvement, such as attending religious services and other activities within a religious community (Denton and Culver 2015). Despite this decline, when compared to counterparts of other racial and ethnic groups, Black emerging adults report that their religion is important to them (Uecker et al. 2007) and do remain religiously involved (Arnett 2004; Lee et al. 2018a). For many Black emerging adults, religious involvement and racial/ethnic identity are intertwined (McGuire 2018). Others utilize religious involvement and beliefs as forms of coping (Kohn-Wood et al. 2012; Lee et al. 2018a; Patton and McClure 2009). Religious involvement, broadly, for better or for worse, has been shown to be significantly linked to a range of health behaviors and outcomes for Black emerging adults, in general (Horton et al. 2018; Lee et al. 2018b; Strayhorn 2011). However, studies on Black emerging adult religiosity neglect to address the contribution of ethnic differences within their samples. Going forward, a significant goal of our study is to extend what is known about the association between religion and health by addressing this link within the context of Black Caribbean emerging adulthood in the USA.

Although the literature on the experiences of emerging adults has been growing, we have limited knowledge of the religious experiences of emerging adults who identify as Black Caribbean in the United States and how these experiences affect their health. We address this recognized gap in the evidence base, by presenting a comprehensive systematic review of the current published literature on Black Caribbean emerging adults’ religiosity and health. The aims of this systematic review are twofold: (1) to synthesize what is currently known about the role of religion on the health of Black Caribbean emerging adults, and (2) to understand the implications of religion on their health behaviors and outcomes.

Methods

This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (PRISMA, http://www.prisma-statement.org/), which outline ethical standards for systematic reviews, and was registered in the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017063814). We searched four online databases (i.e., MEDLINE including epublications ahead of print, in-process, and other non-indexed citations, PsycINFO, Embase, and CINAHL) using combinations of controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms such as “spirituality”), analogous headings in the PsycINFO Thesaurus, Emtree, and CINAHL Headings, and free text to identify potentially relevant papers. The MEDLINE search strategy can be found in “Appendix A.” Articles of any study design were included if they focused on the spiritual and/or religious experiences of emerging adults with Black Caribbean heritage living in the United States, referred to health outcomes or behaviors, and were published before November 30, 2018. “Black Caribbean heritage” was understood as used by the National Survey of American Life (Jackson et al. 2004; Williams et al. 2007). The exclusion criteria for identified articles were (1) primary focus was not on religion/spirituality and health; (2) study sample did not include Black Caribbean living in the USA; (3) study sample did not include people aged 18–29, or did not present data separately for this age group; and (4) commentary, letters to the editor or opinion pieces, book reviews, study/clinical protocols, and feature articles (i.e., narrative-style journalistic pieces).

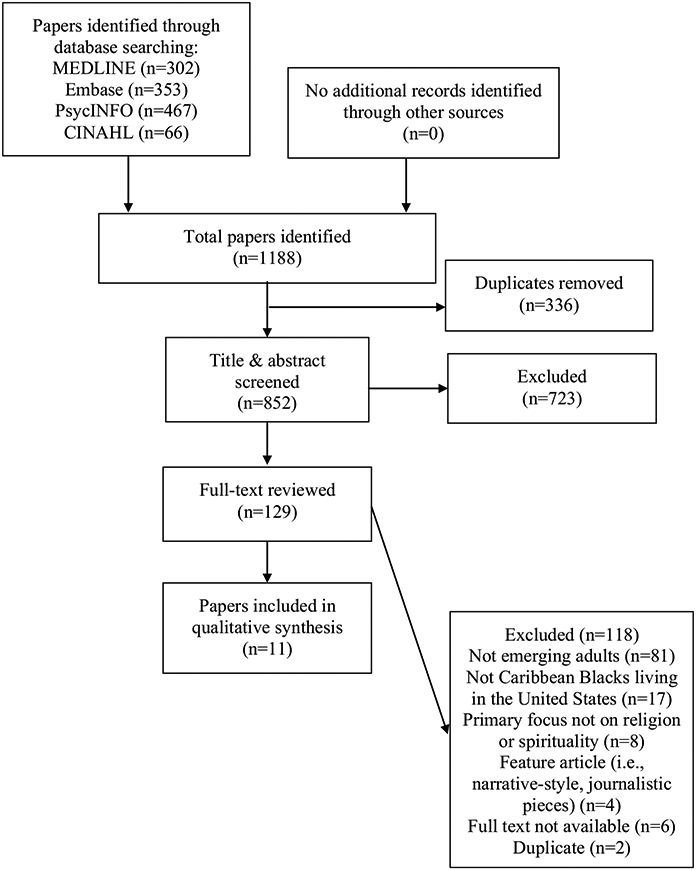

A search strategy was developed, tested, and applied to the four bibliographic databases by a medical librarian (KN). After duplicate citations had been removed, three authors (MH, TT, KG) screened the titles and abstracts against the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria using dual review. The interrater reliability among reviewers was 0.90, indicating strong agreement. Discrepancies were discussed within each dyad until consensus was reached; if no consensus was reached, the article underwent review by all three authors until consensus was reached. Two authors (MH, TT) reviewed and evaluated all full texts for inclusion. Studies excluded during the full-text review stage and their reasons for exclusion are listed in the PRISMA diagram (Fig. 1). Data were extracted using a data extraction form consisting of a set of 36 defined fields. The first and second authors (MH, TT) independently extracted data from each article and then reconciled their responses to ensure consistency. Extracted data were entered in a spreadsheet for analysis. Two members of the research team (MH, TT) conducted a quality assessment of the 11 included studies using a checklist tool for assessing quality in observational studies (Sanderson et al. 2007). The six domains used to assess risk of bias included (1) methods for selecting study participants, (2) methods for measuring exposure and outcome variables, (3) design-specific source of bias, (4) method to control confounding, (5) statistical methods, and (6) other biases (including conflict of interest and disclosure of funding sources). For each study, the quality of each of these six items was categorized as low risk (+), high risk (−), or unclear (?) as recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins and Green 2008). We added an additional category of not applicable (N/A).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram describing study selection process

Results

Screening Process

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA diagram which describes the study selection process. Initially, 1188 studies were retrieved from four databases: MEDLINE (n = 302), Embase (n = 353), PsycINFO (n = 467), and CINAHL (n = 66). All studies were transferred to Covidence for review. Three hundred and thirty-six duplicates were removed, and 723 studies were eliminated during initial title and abstract review. During the full-text review process, 118 studies were eliminated based on our exclusion criteria leaving 11 studies. Table 1 presents the quality assessments of the included studies. Only one study was at low risk for all six methodological quality items (Brown et al. 2015). The remaining 10 studies were at high or unclear risk of at least one of the bias items; none of the studies were at high risk for all bias items. A total of 11 studies were included in this review.

Table 1.

Quality Assessment of Selected Studies

| Author, year | (1) Methods for selecting study participants |

(2) Methods for measuring exposure and outcome variables |

(3) Design- specific source of bias |

(4) Method of control confounding |

(5) Statistical methods |

(6) Other biases (including conflict of interest and disclosure of funding sources) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amos (2018) | − | + | − | + | + | ? |

| Brown et al. (2015) | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Gillespie-Johnson 2008 | + | N/A | + | N/A | + | + |

| Gonsalves and Bernard 1983 | − | + | − | ? | − | − |

| Gonsalves and Bernard (1985) | − | + | − | ? | − | − |

| Kane (2010) | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Ledford (2010) | − | N/A | + | N/A | + | − |

| Luna and MacMillan (2015) | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| Mollenkopf et al. (2005) | + | − | − | + | + | − |

| Turner et al. (2019) | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| Zeda Batista (1998) | − | + | − | − | − | ? |

Low risk of bias: +; High risk of bias: −; Unclear: ?; Not applicable: N/A

Study Characteristics

Table 2 presents the study characteristics of the included studies. Seven studies used a quantitative cross-sectional study design, and three studies used both a quantitative and qualitative cross-sectional study design. The majority of studies used convenience sampling (Amos 2018; Zeda Batista 1998; Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985; Kane 2010; Ledford 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015). All eleven studies reported the gender of study participants, and the majority included both men and women (Zeda Batista 1998; Brown et al. 2015; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985; Kane 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015; Mollenkopf et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2019). Only two studies included women only (Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Ledford 2010); no studies were exclusively focused on men. Of the nine studies that included men and women participants, five had a majority of female participants (Amos 2018; Agrawal et al. 2017; Zeda Batista 1998; Luna and MacMillan 2015; Mollenkopf et al. 2005). The majority of the studies collected data from samples from large cities in the USA including five in New York City and three in Miami/ South Florida. Two studies used data from a national sample (Brown et al. 2015; Turner et al. 2019).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies and samples

| Author (year) | Study design and method | Measure of religion | Sample size and ethnic composition |

Gender | Study site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amos (2018) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Spirituality (b) Spiritual coping (c) Ethereal indicators |

155 African American, Black, Caribbean Black, and mixed race | Men and women | USA |

| Brown et al. (2015) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | Religious non-involvement: (a) Service attendance b) Religious denomination c) Religious identification |

7356 African Americans 404 Caribbean Blacks 1954 Asians 6462 Hispanic 49,056 White non-Hispanic |

Men and women | USA |

| Gillespie-Johnson 2008 | Cross-sectional, qualitative | Religious beliefs: (a) Health belief model used to guide question development |

20 Jamaicans | Women only | Miami and Fort Lauderdale, USA |

| Gonsalves and Bernard 1983 | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Protestant ethic scale (b) Religious tradition |

22 African Americans 20 Caribbean Blacks |

Men and women | New York City, USA |

| Gonsalves and Bernard (1985) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Protestant ethic scale (b) Conservatism scale |

22 African Americans 20 Caribbean Blacks 31 White 10 Hispanics 9 Asians |

Men and women | New York City, USA |

| Kane (2010) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Willingness to seek help from clergy (b) Perceptions of clergy c) Perceptions of people who would seek help from clergy d) Religious service attendance |

92 White 64 African Americans and Caribbean Blacks 25 Latino 4 Other |

Men and women | South Florida, USA |

| Ledford (2010) | Cross-sectional, quantitative and qualitative | (a) Religious involvement (b) Religious support (c) Frequency of religious service attendance |

6 African Americans 4 Caribbean Blacks |

Women only | New York City, USA |

| Luna and MacMillan (2015) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Religious denomination (b) Spiritual transcendence index |

579 Latinos 228 African Americans 196 Caribbean Blacks 126 White |

Men and women | New York City and South Florida, USA |

| Mollenkopf et al. (2005) | Cross-sectional, quantitative and qualitative | (a) Importance of religion in life (b) Religious values and beliefs |

410 South American 424 Dominican 428 Puerto Rican 404 Caribbean Black 422 Black 607 Chinese 310 Russian 409 White |

Men and women | New York City and New Jersey, USA |

| Turner et al. (2019) | Cross-sectional, quantitative | (a) Importance of religion in life (b) Importance of spirituality in life |

4703 African American 305 Caribbean Black |

Men and women | USA |

| Zeda Batista (1998) | Cross-sectional, quantitative and qualitative | (a) Religious upbringing (b) Religious practices (c) Religious beliefs (d) Religious denominations (e) Visiting faith healers |

100 Puerto Rican | Men and women | Massachusetts and Connecticut, USA |

Nine studies reported the age of study participants; all selected studies included individuals ages 18 and older. Only one study (Ledford 2010) included individuals ages 18–29 years exclusively, while one study included individuals ages 18–30 years (Gillespie-Johnson 2008). Two studies did not report a specific age range (Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985); rather, the authors described their respective samples as undergraduates attending 4-year colleges.

All eleven studies reported participants’ racial and/or ethnic identity including, but not limited to African American, Black Caribbean, non-Hispanic White, Latino, Asian, and mixed race. Three studies included African American and Black Caribbean participants only (Gonsalves and Bernard 1983; Ledford 2010; Turner et al. 2019), while two studies included Black Caribbean participants only (Zeda Batista 1998; Gillespie-Johnson 2008). Six studies reported participants’ place of birth or ancestral ties (Zeda Batista 1998; Brown et al. 2015; Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Kane 2010; Ledford 2010; Mollenkopf et al. 2005). Of these, the majority of participants were born in or had ancestral ties to Jamaica (Gillespie-Johnson 2008) or Puerto Rico (Zeda Batista 1998; Mollenkopf et al. 2005). The predominant religious denominations mentioned in these studies were Catholic Christianity and Protestant Christianity.

The majority of studies included a guiding theoretical or conceptual framework (Amos 2018; Brown et al. 2015; Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985; Ledford 2010; Mollenkopf et al. 2005). These theories and conceptual frameworks included the health belief model, security axiom, Protestant work ethic, critical race theory, and womanist theories. Only one study included a developmental theory (Ledford 2010).

The Role of Religion Among Caribbean Black Emerging Adults

Operationalization of Religion

Religion was most often operationalized as frequency of religious service attendance (Brown et al. 2015; Ledford 2010) and religious involvement (Brown et al. 2015; Ledford 2010). Other terms reflecting aspects of religion indirectly referenced in these studies included religious beliefs, religious practices, religious socialization, and religious support.

Seven studies measured specific aspects of religion, but only five reported psychometric information for the measures of religion (Amos 2018; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985; Luna and MacMillan 2015) or provided details on the methods used for constructing the religious measures used in the study (Kane 2010). Four studies distinguished spirituality from religion (Brown et al. 2015; Kane 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015; Turner et al.2019).

Religion and Health Outcomes

Seven studies explicitly focused on the contributions of religion to health outcomes for Black Caribbean emerging adults (Amos 2018; Zeda Batista 1998; Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Kane 2010; Ledford 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015; Turner et al. 2019). Out of these, three examined links to mental health (Zeda Batista 1998; Kane 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015), and three examined aspects of religious support as a vehicle for seeking mental health care (Zeda Batista 1998; Kane 2010; Turner et al. 2019). Additional health outcomes included sexual health behaviors in general (Ledford 2010), HIV/AIDS prevention (Gillespie-Johnson 2008), coping (Amos 2018), and pregnancy (Ledford 2010).The remaining four studies that did not measure a specific health outcome, assessed either a health behavior or included implications for health (Brown et al. 2015; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985; Mollenkopf et al. 2004). In all eleven studies, religious determinants of health or other types of outcomes were self-reported, and only two cited a reliable and validated measure to assess the health outcome (Amos 2018; Luna and MacMillan 2015).

Religion as Health Benefit or Risk

As a part of our review, we also examined whether each study framed religion as beneficial or risky for health outcomes. We found that only four studies framed religion as contributing both benefits and risks to individuals (Zeda Batista 1998; Kane 2010; Ledford 2010; Luna and MacMillan 2015), whereas three studies did not report benefits or risks (Brown et al. 2015; Gonsalves and Bernard 1983, 1985). The remaining four studies presented religion as either a benefit (Amos 2018; Mollenkopf et al. 2005; Turner et al. 2019) or a risk (Gillespie-Johnson 2008).

Discussion

The aims of this systematic review were twofold: (1) to synthesize the current state of the literature regarding the role of religion for Black Caribbean emerging adults, and (2) to understand the contributions and implications of religion for their health behaviors and outcomes. Our search yielded eleven independent studies which investigated religious influences on the health of Black Caribbean emerging adults living in the United States. Three main points of discussion emerged from our systematic analysis. First, significant differences exist in the measurement of religion across studies. Second, an intersectional theoretical lens is needed to understand how religion, health, and sociocultural factors function for African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Third, there is a need for more rigorous research that allows for the examination of the mechanisms undergirding the associations between religiosity and Black Caribbean emerging adult health.

First, this review found significant differences across the definition and measurement of religion. It was most frequently operationalized as frequency of religious service attendance (Brown et al. 2015; Ledford 2010) as well as other forms of organizational and non-organizational religious involvement (e.g., prayer and reading religious texts). In addition, two studies operationalized religiosity by focusing on religious beliefs (Amos 2018; Gillespie-Johnson 2008). Studies that account for various dimensions (public behaviors, private devotional practices, subjective religiosity) of religious involvement can further solidify scholarly understanding regarding how different aspects of religion may (or may not) function as promotive health resources.

Furthermore, Black Caribbean religiosity often intersects with issues of immigration status, acculturation, and assimilation (Johnson 2008). This, in turn, often influences the form and nature of religious involvement and its subsequent impact on health outcomes. For example, newly immigrated and first-generation Black Caribbeans may strongly identify as Caribbean (as opposed to African American) and engage in religious contexts (e.g., faith-based settings) that explicitly reinforce ethnic identification and provide psychological and structural space for that identification (Waters 2001; Edwards 2008; Emerson et al. 2015). Many Black Caribbeans identify as Baptist or Catholic (Taylor et al. 2010), and they may gravitate to these denominations once in the United States. An emerging literature does examine religious involvement and the functions of immigrant churches for Black Caribbeans (Johnson 2008; Hayward and Krause 2015; Taylor et al. 2010). Often situated in immigrant enclaves, these churches provide a trusted institutional base, access to church-based support networks and local community resources, development of social capital, and reinforcement of ethnic identities and ties (Agyekum and Newbold 2016; Chaze et al. 2015; Shapiro 2018; Taylor et al. 2007a, b; Waters 1999).

Conversely, for families residing in the United States for two or more generations, acclimation and acculturation may lessen the degree to which significant cultural distinctions between Black Caribbeans and African Americans exist (Waters 1994). For many ethnic minorities, faith significantly informs ethnic and cultural identification (and vice versa) (Edwards 2008; Emerson et al. 2015). The role of religion with respect to positive, long-term health outcomes, and trajectories may depend on the degree to which individuals emphasize religiosity as a significant part of their ethnic identity (Cone 1984; Hayward and Krause 2015). Taken together, this research underscores the importance of ethnic group membership and the nature of the immigration experience in shaping distinctive religious involvement profiles for Black Caribbeans. To date, much of this work has focused on older adults, and much less so regarding Black Caribbean emerging adulthood.

Second, this systematic review underscores the importance of using parenthetical intersectionality. This theoretical framework highlights the intersection between multiple social identities (see Bowleg 2012 and Veenstra 2011) to better understand similarities and differences between African Americans and Black Caribbean in how religion, sociocultural, and other factors (e.g., gender) shape health beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors (see Cho et al. 2013). This is particularly important for examining distinct identities (i.e., racial, ethnic, immigrant) and social locations (i.e., education, income, language) that represent sources of both privilege and oppression within the context of the USA (Viruell-Fuentes et al. 2012). However, studies examined in the review did not employ an intersectional perspective. Although the majority of studies referenced a theoretical or conceptual framework, they lacked strong and explicit connections to the referenced theory, which may be partially due to differences in the extent to which specific disciplines are explicitly theory-driven. For example, Brown et al. (2015) used the security axiom theory proposed by Norris and Inglehart (2011) to address race and ethnic differences in the sociodemographic determinants of religious non-involvement, including differences by age cohort (e.g., Generation X/Millennials).

Lastly, the systematic review suggests that the next steps for further delineation of the mechanisms underlying religion’s connections to health behaviors, practices, and outcomes should focus on the type of health outcome and the respective role that religion may fulfill for that outcome. The type of health outcomes most frequently identified in the systematic review was sexual health and mental health. However, religion influences a wider range of health behaviors and health outcomes among Black Americans (Koenig and King 2012; Lee et al. 2018a, b; Smith and Denton 2005). For example, belief systems include distinct theological frameworks for understanding and addressing various medical conditions. Further, psychological and psychiatric conditions may be perceived as a punishment from God, or moral failings that can be simply dealt with by ignoring the problem or increased individual- or corporate-level religious engagement (Gillespie-Johnson 2008; Reese et al. 2012). However, because much of this research has primarily emphasized African Americans (Holt et al. 2003), more work is needed to ascertain how the link between religion and health functions for health outcomes within Black Caribbean populations in the United States and Black Caribbean emerging adults, in particular.

Research on religion and health connections among emerging adults should be cognizant of their unique characteristics and life circumstances and diversity within this life stage. Relatively young emerging adults (18–21 years) who may still be dependent on their family for financial and residential needs may adhere to the religious beliefs systems in which they are socialized. In contrast, older emerging adults (22–29 years) who may be less dependent on these relationships may have increased exposure to other communities and worldviews and be more comfortable exploring health beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors that are different from their religious or cultural community. Recognizing the potential contributions of religious belief systems to health outcomes can enhance the effectiveness of researchers and clinicians to generate effective, evidence-based treatments, and protocols for addressing medical, public health, and mental health issues, and trends in this population. We foresee that extant limitations identified in this systematic review will serve as guides for future lines of inquiry across disciplines.

Implications

All studies examined in this systematic review were cross-sectional studies. More longitudinal studies are needed to examine whether, how, and what aspects of religiosity remain potentially significant and protective resources for Black Caribbean emerging adults. As knowledge regarding the association between religion and health grows, continuing research should pose more complex questions focusing on the various mechanisms through which religion functions in this population. Exploring religious affiliation differences among Black Caribbeans may provide more nuanced information. Religious affiliation often reflects the residual impact of colonization (e.g., English, Spanish, French, Dutch), where colonizing nations emphasized particular religious traditions and practices over those held by colonized groups, shaping religious affiliation patterns for distinct Caribbean countries (e.g., Anglican, Catholicism, Baptist). In turn, the unique characteristics of these religious traditions may yield differentiating implications for Black Caribbeans’ health outcomes in the United States. More information regarding these links may further increase the effectiveness of evidence-based interventions, with an explicit focus on Black Caribbean emerging adulthood.

Understanding the wide range of Caribbean Black emerging adults’ religious and spiritual experiences may provide invaluable tools for clinicians and practitioners in the arenas of health care and social work. A willingness to integrate Black Caribbean emerging adults’ religiosity and spirituality into treatment plans may not only promote positive outcomes in a manner that is deeply salient to clients and patients but can also reveal potential obstacles that hinder clients’ ability to benefit from treatment. Those who identify as an ethnic minority are less likely to seek out psychological help than their majority-group counterparts (Gullatte et al. 2006; Poussaint and Alexander 2000). This may especially be the case for those from immigrant backgrounds. Results from a repeated cross-sectional study indicated that some ethnic minorities tend not to perceive that mental health treatment is needed (Breslau et al. 2017). Religion-related factors, such as religious socialization, currently held religious beliefs, or specific theological principles, may also influence whether or not individuals seek out, comply with, and remain in treatment.

Conclusion

As a growing body of research acknowledges the heterogeneity within the diasporic Black community in the United States, we recommend greater examination of the perspectives and experiences of diverse groups within this population. Religion, a prominent factor among Black Americans, often influences health behaviors and decisions, psychosocial well-being, and practical and applied understanding of disease. Examining how religion functions regarding health outcomes may reveal important and unique contributing factors in the development of culturally relevant and developmentally appropriate interventions for Black emerging adults.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Linda Chatters, Ph.D. for her feedback on this manuscript. This project was supported by NIH Grant No. 3R25CA057711, and it is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Additional support for Dr. Tamara Taggart was provided by a postdoctoral fellowship supported by Award Numbers T32MH020031 and P30MH062294 from the National Institute of Mental Health, and a Scholar with the HIV/AIDS, Substance Abuse, and Trauma Training Program (HA-STTP), at the University of California, Los Angeles (R25DA035692).

Appendix

Appendix A:

MEDLINE Search Strategy

| Line number | Search term |

|---|---|

| 1 | magic/ |

| 2 | Voodoo.tw. |

| 3 | (Vodun or Vodou or Vodoun or Vaudou or Vaudoux).tw. |

| 4 | priest*.tw. |

| 5 | (Santeria or Santero or Santera).tw. |

| 6 | Christian*.tw. |

| 7 | Catholic*.tw. |

| 8 | Protestant*.tw. |

| 9 | Hindu*.tw. |

| 10 | non-denominational.tw. |

| 11 | nondenominational.tw. |

| 12 | (Islam* or Muslim*).tw. |

| 13 | Five Percent Nation.tw. |

| 14 | Rastafari*.tw. |

| 15 | Rasta.tw. |

| 16 | Rastas.tw. |

| 17 | Spirituality/ |

| 18 | exp Religion/ |

| 19 | spiritual*.tw. |

| 20 | religio*.tw. |

| 21 | (churchgo* or church-go*).tw. |

| 22 | or/1–21 |

| 23 | (Anguilla or Anguillan or Anguillans or Anguillian or Anguillians).tw. |

| 24 | (Antigua or Antiguan or Antiguans or Barbuda or Barbudan or Barbudans).tw. |

| 25 | (Aruba or Aruban or Arubans).tw. |

| 26 | (Bahamas or Bahamian or Bahamians).tw. |

| 27 | (Barbados or Barbadian or Barbadians).tw. |

| 28 | (Belize or Belizean or Belizeans).tw. |

| 29 | (Bermuda or Bermudan or Bermudans).tw. |

| 30 | (British Virgin Islands or Virgin Islander or Virgin Islanders).tw. |

| 31 | Anegada.tw. |

| 32 | (Tortola or Tortolan or Tortolans).tw. |

| 33 | Virgin Gorda.tw. |

| 34 | (Cayman Islands or (Caymanian or Caymanians)).tw. |

| 35 | Cayman Brac.tw. |

| 36 | Grand Cayman.tw. |

| 37 | Little Cayman.tw. |

| 38 | (Dominica or Dominican or Dominicans).tw. |

| 39 | (French Guiana or Guianan or Guianans).tw. |

| 40 | (Grenada or Grenadines or Grenadian or Grenadians).tw. |

| 41 | Carriacou.tw. |

| 42 | (Guadeloupe or Guadeloupean or Guadeloupeans).tw. |

| 43 | Grenadines.tw. |

| 44 | (Guyana or Guyanese).tw. |

| 45 | (Haiti or Haitian or Haitians or Haitien or Haitiens).tw. |

| 46 | (Jamaica or Jamaican or Jamaicans).tw. |

| 47 | (Martinique or Martinican or Martinicans or Martiniquais).tw. |

| 48 | Monserrat.tw. |

| 49 | (Netherlands Antilles or Netherlands Antillean or Netherlands Antilleans).tw. |

| 50 | Bonaire.tw. |

| 51 | Curacao.tw. |

| 52 | Saba.tw. |

| 53 | (Sint Eustatius or Statia or St Eustatius).tw. |

| 54 | (Sint Maarten or St Maarten or Maartener or Maarteners).tw. |

| 55 | (Saint Kitts or Nevis or St Kitts).tw. |

| 56 | (St Lucia or Saint Lucia or Saint Lucian or Saint Lucians or Sainte Lucie).tw. |

| 57 | (Saint Vincent or Vincentian or Vincentians or Grenadines).tw. |

| 58 | Bequia.tw. |

| 59 | Grenandines.tw. |

| 60 | (Suriname or Surinam or Surinamese).tw. |

| 61 | (Trinidad or Tobago or Trinidadian or Trinidadians or Tobagonian or Tobagonians).tw. |

| 62 | (Caicos or Turks Islands or (Turks and Caicos Islander) or (Turks and Caicos Islanders)). tw. |

| 63 | (United States Virgin Islands or Virgin Islands of the United States or USVI or US Virgin Islands or Virgin Islander or Virgin Islanders).tw. |

| 64 | (St Croix or Saint Croix or Crucian or Crucians).tw. |

| 65 | (Saint John and Virgin).tw. |

| 66 | (Saint Thomas and Virgin).tw. |

| 67 | (Leeward Islands or Leeward Islander or Leeward Islanders).tw. |

| 68 | (Windward Islands or Windward Islander or Windward Islanders).tw. |

| 69 | (West Indies or West Indian or West Indians).tw. |

| 70 | (British West Indies or BWI).tw. |

| 71 | (Puerto Rico or Puerto Rican or Puerto Ricans or Boricua).tw. |

| 72 | (Dominican Republic or Republica Dominicana or Dominican or Dominicans).tw. |

| 73 | (Cuba or Cuban or Cubans).tw. |

| 74 | (Panama or Panamanian or Panamanians).tw. |

| 75 | (Costa Rica or Costa Rican or Costa Ricans).tw. |

| 76 | (Nicaragua or Nicaraguan or Nicaraguans).tw. |

| 77 | (Honduras or Honduran or Hondurans or Garifuna or Garifunas).tw. |

| 78 | 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 or 72 or 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 |

| 79 | (Caribbean or caribbeans).tw. |

| 80 | Exp West Indies/ |

| 81 | Bermuda/ |

| 82 | Central America/ |

| 83 | Belize/ |

| 84 | Costa Rica/ |

| 85 | Honduras/ |

| 86 | Nicaragua/ |

| 87 | exp Panama/ |

| 88 | French Guiana/ |

| 89 | Guyana/ |

| 90 | Suriname/ |

| 91 | exp Caribbean Region/ |

| 92 | or/23–91 |

| 93 | exp African Continental Ancestry Group/ |

| 94 | (Afro* or black* or African*).tw. |

| 95 | 93 or 94 |

| 96 | 22 and 92 and 95 |

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Agrawal A, Grant JD, Haber JR, Madden PAF, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, et al. (2017). Differences between White and Black young women in the relationship between religious service attendance and alcohol involvement. American Journal of Addiction, 26(5), 437–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agyekum B, & Newbold BK (2016). Religion/spirituality, therapeutic landscape and immigrant mental well-being amongst African immigrants to Canada. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 19(7), 674–685. [Google Scholar]

- Amos BR (2018). Coping and Africultural adolescents. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Western Michigan University, Michigan, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M (2015). A rising share of the U.S. black population is foreign born. Pew Research Center. Retrieved November 1, 2019 from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/04/09/a-rising-share-of-the-u-s-black-population-is-foreign-born/.

- Anderson M, & Lopez G (2018). Key facts about Black immigrants in the U.S Pew Research Center: Retrieved November 2, 2019 from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/01/24/key-facts-about-black-immigrants-in-the-u-s. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2005). The developmental context of substance use in emerging adulthood. Journal of Drug Issues, 35(2), 235–254. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2007). Suffering, selfish, slackers? Myths and reality about emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(1), 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2014). Adolescence and emerging adulthood. Boston, MA: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, & Mitra D (2018). Are the features of emerging adulthood developmentally distinctive? A comparison of ages 18–60 in the United States. Emerging Adulthood. 10.1177/2167696818810073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, Žukauskienė R, & Sugimura K (2014). The new life stage of emerging adulthood at ages 18–29 years: Implications for mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 569–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baier CJ, & Wright BR (2001). “If you love me, keep my commandments”: A meta-analysis of the effect of religion on crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38(1), 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Billioux VG, Sherman SG, & Latkin C (2014). Religiosity and HIV-related drug risk behavior: A multidimensional assessment of individuals from communities with high rates of drug use. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(1), 37–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—An important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis CJ, & McConnell KM (2006). Quest orientation in young women: Age trends during emerging adulthood and relations to body image and disordered eating. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 16(3), 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Cefalu M, Wong EC, Burnam MA, Hunter GP, Florez KR, et al. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in perception of need for mental health treatment in a US national sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(8), 929–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RK, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2015). Race/ethnic and social-demographic correlates of religious non-involvement in America: Findings from three national surveys. Journal of Black Studies, 46(4), 335–362. [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM (2000). Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 21, 335–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Bullard KM, Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Neighbors HW, & Jackson JS (2008). Religious participation and DSM-IV disorders among older African Americans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 957–965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Nguyen A, & Joe S (2011). Church-based social support and suicidality among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Archives of Suicide Research, 15(4), 337–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaze F, Thomson MS, George U, & Guruge S (2015). Role of cultural beliefs, religion, and spirituality in mental health and/or service utilization among immigrants in Canada: A scoping review. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 34(3), 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Crenshaw KW, & McCall L (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 785–810. [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Lewis YC, Gipson PY, Opperman KJ, Arango A, & King CA (2016). Protective role of religious involvement against depression and suicidal ideation among youth with interpersonal problems. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(4), 1172–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone JH (1984). For my people: Black theology and the Black church. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, McGrady ME, & Rosenthal SL (2010). Measurement of religiosity/spirituality in adolescent health outcomes research: Trends and recommendations. Journal of Religion and Health, 49(4), 414–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debnam K, Holt CL, Clark EM, Roth DL, & Southward P (2012). Relationship between religious social support and general social support with health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(2), 179–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton ML, & Culver J (2015). Family disruption and racial variation in adolescent and emerging adult religiosity. Sociology of Religion, 76(2), 222–239. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KL (2008). Bring race to the center: The importance of race in racially diverse religious organizations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 47(1), 5–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & Levin JS (1998). The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior, 25(6), 700–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emerson MO, Korver-Glenn E, & Douds KW (2015). Studying race and religion: A critical assessment. Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 1(3), 349–359. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia G, Ellison CG, Sunil TS, & Hill TD (2013). Religion and selected health behaviors among Latinos in Texas. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(1), 18–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves SV, & Bernard GA (1983). The relationship between the Protestant ethic and social class for Afro-Caribbeans and Afro-Americans. Psychological Reports, 53(2), 645–646. [Google Scholar]

- Gonsalves SV, & Bernard GA (1985). The relationship between parental social class and endorsement of items on the Protestant ethic and conservatism scales. Psychological Reports, 57(3), 919–922. [Google Scholar]

- Gullatte MM, Phillips JM, & Gibson LM (2006). Factors associated with delays in screening of self-detected breast changes in African-American women. Journal of National Black Nurses ’ Association: Journal of National Black Nurses Association, 17(1), 45–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall TW, Edwards E, & Wang DC (2016). The spiritual development of emerging adults over the college years: A 4-year longitudinal investigation. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 8(3), 206. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JB, Stewart JM, Thompson K, Alvarez C, Best NC, Amoah K, et al. (2017). Younger African American adults’ use of religious songs to manage stressful life events. Journal of Religion and Health, 56, 329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankerson SH, Wong EC, & Polite K (2018). The Black church and mental health In Griffith EE, Jones BE, Stewart AJ (Eds.), Black mental health: Patients, providers, and systems (pp. 183–193). Washington, DC: APA Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward RD, & Krause N (2015). Religion and strategies for coping with racial discrimination among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks. International Journal of Stress Management, 22(1), 70. [Google Scholar]

- Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, & Berglund P (2004). Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 221–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J, & Green S (2008). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Himle JA, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2012). Religious involvement and obsessive compulsive disorder among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(4), 502–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Clark EM, Kreuter MW, & Rubio DM (2003). Spiritual health locus of control and breast cancer beliefs among urban African American women. Health Psychology, 22(3), 294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MO, Assari S, Cole-Lewis YC, & Caldwell CH (2017). Religious social support, discrimination, and psychiatric disorders among Black adolescents. Race and Social Problems, 9(2), 102–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MO, Lee DB, Hsieh HF, Hurd NM, Sparks HL, & Zimmerman MA (2019a). Violence exposure and sexual risk behaviors: The protective role of natural mentorship and organizational religious involvement. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(1–2), 242–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope MO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, & Chatters LM (2019b). Church support among African American and Black Caribbean adolescents. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 25(11), 3037–3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton SE, Timmerman GM, & Brown A (2018). Factors influencing dietary fat intake among black emerging adults. Journal of American College Health, 66(3), 155–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler EL (Ed.). (2014). Religion as a social determinant of public health. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Torres M, Caldwell CH, Neighbors HW, Nesse RM, Taylor RJ, et al. (2004). The National Survey of American Life: A study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and mental health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 196–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson VMS (2008). What, then, is the African American?: African and Afro-Caribbean identities in Black America. Journal of American Ethnic History, 28(1), 77–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kane MN (2010). Predictors of university students’ willingness in the USA to use clergy as sources of skilled help. Mental Health, Religion, & Culture, 13(3), 309–325. [Google Scholar]

- Kent MM (2007). Immigration and America’s Black population (Vol. 62, No. 4). Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig H, King D, & Carson B (2012). Handbook of religion and health (Vol. B). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn-Wood LP, Hammond WP, Haynes TF, Ferguson KK, & Jackson BA (2012). Coping styles, depressive symptoms and race during the transition to adulthood. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 15(4), 363–372. [Google Scholar]

- Le D, Holt CL, Hosack DP, Huang J, & Clark EM (2016). Religious participation is associated with increases in religious social support in a national longitudinal study of African Americans. Journal of Religion and Health, 55, 1449–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford EM (2010). Young black single mothers and the parenting problematic: The Church as model of family and as educator. Fordham University. [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Hope MO, Heinze JE, Cunningham M, Caldwell CH, & Zimmerman MA (2018a). Psychological pathway from racial discrimination to the physical consequences of alcohol consumption: Religious coping as a protective factor. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 10.1080/15332640.2018.1540956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, & Neblett EW (2019). Religious development in African American adolescents: Growth patterns that offer protection. Child Development, 90(1), 245–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DB, Peckins MK, Miller AL, Hope MO, Neblett EW, Assari S, Muñoz-Velázquez J, & Zimmerman MA (2018b). Pathways from racial discrimination to cortisol/DHEA imbalance: Protective role of religious involvement. Ethnicity & Health. 10.1080/13557858.2018.1520815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (1995). A multidimensional measure of religious involvement for African Americans. The Sociological Quarterly, 36(1), 157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston IL, Neita M, Riviere L, & Livingston SL (2007). Gender, acculturative stress and Caribbean immigrants health in the United States of America: An exploratory study. West Indian Medical Journal, 56(3), 213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis DA, Thompson KV, Smith P, Williams HMA, & Watson J (2017). Afro-Caribbean immigrant faculty experiences in the American Academy: Voices of an invisible black population. The Urban Review, 49(4), 668–691. [Google Scholar]

- Luna N, & MacMillan T (2015). The relationship between spirituality and depressive symptom severity, psychosocial functioning impairment, and quality of life: Examining the impact of age, gender, and ethnic differences. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 18(6), 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie E, Rajagopal D, Meibohm M, & Lavizzo-Mourey R (2000). Spiritual support and psychological well-being: Older adults’ perceptions of the religion and health connection. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 6(6), 37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Kubzansky L, Kawachi I, Seeman T, & Berkman L (2007). Religious service attendance and allostatic load among high-functioning elderly. Psychosomatic Medicine, 69(5), 464–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire KM (2018). Religion’s afterlife: The noninstitutional residuals of religion in Black college students’ lived experiences. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(3), 309–324. [Google Scholar]

- Mollenkopf J, Waters MC, Holdaway J, Kasinitz P, Setterstein R, Furstenberg F, et al. (2005). The ever winding path: Ethnic and racial diversity in the transition to adulthood In Settersten RA, Furstenberg FF, & Rumbaut RG (Eds.), On the frontier of adulthood: Theory, research, and public policy (pp. 454–497). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mouzon D (2017). Religious involvement and the Black–White paradox in mental health. Race & Social Problems, 9(1), 63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer A, Goldenberg M, Schneider S, Sohl S, & Knapp S (2014). Psychosocial interventions for cancer patients and outcomes related to religion or spirituality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psycho-Social Oncology, 3(1). [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LJ, & Barry CM (2005). Distinguishing features of emerging adulthood: The role of self-classification as an adult. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20(2), 242–262. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AW, Taylor RJ, & Chatters LM (2016). Church-based social support among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research, 58(3), 385–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris P, & Inglehart R (2011). Sacred and secular: Religion and politics worldwide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patton LD, & McClure ML (2009). Strength in the spirit: A qualitative examination of African American college women and the role of spirituality during college. Journal of Negro Education, 78, 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Poussaint A, & Alexander A (2000). Lay my burden down: Unraveling suicide and the mental health crisis among African Americans. Bostn, MA: Beacon Press Books. [Google Scholar]

- PROSPERO. (2017). Galbraith-Gyan Kayoll V., Hope Meredith O., Taggart Tamara, Nyhan Kate. Caribbean American emerging adults and religiosity: A systematic review of religious influences on health outcomes. CRD42017063814 Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017063814. [Google Scholar]

- Reese AM, Thorpe RJ Jr., Bell CN, Bowie JV, & Laveist TA (2012). The effect of religious service attendance on race differences in depression: Findings from the EHDICSWB Study. Journal of Urban Health, 89(3), 510–518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rew L, & Wong YJ (2006). A systematic review of associations among religiosity/spirituality and adolescent health attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(4), 433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson S, Tatt ID, & Higgins JP (2007). Tools for assessing quality and susceptibility to bias in observational studies in epidemiology: A systematic review and annotated bibliography. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(3), 666–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E (2018). Places of habits and hearts: Church attendance and Latino immigrant health behaviors in the United States. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(6), 1328–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat DE, & Ellison CG (1999). Recent developments and current controversies in the sociology of religion. Annual Review of Sociology, 25(1), 363–394. [Google Scholar]

- Skipper A, Moore TJ, & Marks L (2018). “The prayers of others helped”: Intercessory prayer as a source of coping and resilience in Christian African American families. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 37(4), 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C (2003). Theorizing religious effects among American adolescents. Sociology of Religion, 64(1), 111–133. [Google Scholar]

- Smith C, & Denton ML (2005). Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stoppa TM, & Lefkowitz ES (2010). Longitudinal changes in religiosity among emerging adult college students. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20(1), 23–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strayhorn TL (2011). Singing in a foreign land: An exploratory study of gospel choir participation among African American undergraduates at a predominantly white institution. Journal of College Student Development, 52, 137–153. [Google Scholar]

- Taggart T, Gottfredson N, Powell W, Ennett S, Chatters LM, Carter-Edwards L, et al. (2018). The role of religious socialization and religiosity in African American and Caribbean Black Adolescents’ sexual initiation. Journal of Religion and Health, 57, 1889–1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taggart T, Powell W, Gottfredson N, Ennett S, Eng E, & Chatters LM (2019). A person-centered approach to the study of Black adolescent religiosity, racial identity, and sexual initiation. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29(2), 402–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Jackson JS (2007a). Religious participation among older Black Caribbeans in the United States. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 62, S251–S256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Jackson JS (2007b). Religious and spiritual involvement among older African Americans, Caribbean Blacks and Whites: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. The Journals of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 62, S238–S250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Joe S (2011a). Religious involvement and suicidal behavior among African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 199(7), 478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Joe S (2011b). Non-organizational religious participation, subjective religiosity, and spirituality among older African Americans and Black Caribbeans. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(3), 623–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Levin J (2003). Religion in the lives of African Americans Social, psychological, and health perspectives. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Mattis JS, & Joe S (2010). Religious involvement among Caribbean Blacks in the United States. Review of Religious Research, 52(2), 125–145. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, & Nguyen AW (2013). Religious participation and DSM IV major depressive disorder among Black Caribbeans in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 15(5), 903–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Mattis J, & Chatters LM (1999). Subjective religiosity among African Americans: A synthesis of findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology, 25(4), 524–543. [Google Scholar]

- Turner N, Hastings JF, & Neighbors HW (2019). Mental health care treatment seeking among African Americans and Caribbean Blacks: What is the role of religiosity/spirituality? Aging & Mental Health, 23(7), 905–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uecker JE, Regnerus MD, & Vaaler ML (2007). Losing my religion: The social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Social Forces, 85(4), 1667–1692. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2011). Overview of race and hispanic origin: 2010. Washington, DC: U.S. Census. [Google Scholar]

- Veenstra G (2011). Race, gender, class, and sexual orientation: Intersecting axes of inequality and selfrated health in Canada. International Journal for Equity in Health, 10(1), 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, & Adulrahim S (2012). More than culture: Structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Social Science and Medicine, 75(12), 2099–2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC (1994). Ethnic and racial identities of second generation black immigrants in New York City. International Migration Review, 28(4), 795–820. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC (1999). Black identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waters MC (2001). Black identities: West Indian immigrant dreams and American realities. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Haile R, Gonzalez HM, Neighbors H, Baser R, & Jackson JS (2007). The mental health of Black Caribbean immigrants: Results from the National Survey of American Life. American Journal of Public Health, 97(1), 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, & Jackson JS (2000). Race/ethnicity and the 2000 census: recommendations for African American and other black populations in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 90(11), 1728–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarrett N, & Eccles J (2006). The passage to adulthood: Challenges of late adolescence. New Directions in Youth Development, 111(17), 13–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeda Batista J (1998). Puerto Rican client expectations of therapists and folkloric healers. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Massachusetts; Amherst, Massachusetts, USA. [Google Scholar]