ABSTRACT

As another wave of COVID-19 outbreak has approached in July 2020, a larger scale COVID-19 pediatric Asian cohort summarizing the clinical observations is warranted. Children confirmed with COVID-19 infection from the Republic of Korea, the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) and Wuhan, China, during their first waves of local outbreaks were included. Their clinical characteristics and the temporal sequences of the first waves of local paediatric outbreaks were compared. Four hundred and twenty three children with COVID-19 were analyzed. Wuhan had the earliest peak, followed by Korea and HKSAR. Compared with Korea and Wuhan, patients in HKSAR were significantly older (mean age: 12.9 vs. 10.8 vs. 6.6 years, p < 0.001, respectively) and had more imported cases (87.5% vs. 16.5% vs. 0%, p < 0.001, respectively). The imported cases were also older (13.4 vs. 7.6 years, p < 0.001). More cases in HKSAR were asymptomatic compared to Korea and Wuhan (45.5% vs. 22.0% vs. 20.9%, p < 0.001, respectively), and significantly more patients from Wuhan developed fever (40.6% vs. 29.7% vs. 21.6%, p=0.003, respectively). There were significantly less imported cases than domestic cases developing fever after adjusting for age and region of origin (p = 0.046). 5.4% to 10.8% of patients reported anosmia and ageusia. None developed pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PMIS-TS). In general, adolescents were more likely to be asymptomatic and less likely to develop fever, but required longer hospital stays. In conclusion, majority patients in this pediatric Asian cohort had a mild disease. None developed PIMS-TS. Their clinical characteristics were influenced by travel history and age.

KEYWORDS: COVID-19, Asia, children, travel history, age-stratified

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in Wuhan, China in late December 2019. Subsequently, cases spread to other parts of China, then to neighbouring regions in Asia and worldwide. So far, more than 25 million people have been infected globally and over 860,000 have died due to COVID-19 [1]. The Republic of Korea (Korea) was one of the first Asian countries to be affected. The COVID-19 outbreak in Korea reached its peak in late February 2020, when a significant number of people were infected after attending a religious gathering [2]. In contrast, the COVID-19 outbreak in Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) appeared to peak in late March 2020 [3]. Most of the cases of COVID-19 in Hong Kong appeared to be imported from other parts of the world [4].

Studies on several regional pediatric cohorts from China and Europe have summarized the typical clinical characteristics of children with COVID-19 [5, 6]. However, a summary of the clinical observations in a large-scale Asian cohort of children with COVID-19 is still lacking. As another wave of COVID-19 outbreaks begin to sweep across the region in recent weeks, we could do well to learn from our clinical experiences in Asia during the first wave of COVID-19 to understand the differences between domestic and imported cases that can inform public health policy within the region.

Objectives

In this study, we compared the clinical characteristics of children with confirmed COVID-19 during the first wave of local outbreaks in Korea, HKSAR, and Wuhan. We also compared the clinical characteristics between domestic and imported pediatric COVID-19 cases and between different age groups across the three Asian regions.

Methods

Study population

Children from Korea, HKSAR, and Wuhan below 19 years of age with confirmed COVID-19 by positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of a respiratory specimen were retrospectively included in the study. The three regions have similar case identification, admission and discharge policies. These patients were identified either because of having symptoms suspicious of COVID-19 infection, having epidemiological links to COVID-19 infected patients or returned from abroad. All patients were admitted to isolation facilities regardless of whether they were symptomatic or not. Children with COVID-19 infection in Korea were isolated at 20 hospitals and two non-hospital isolation facilities across the country. Children in Wuhan were all admitted to the Wuhan Children’s Hospital, which was the main center assigned by the central government for treating children diagnosed with SARS-CoV-2 infection in Wuhan. Children in HKSAR were admitted to eight paediatric units with airborne isolation facilities. Discharge criteria were being asymptomatic with two consecutive nasopharyngeal specimens negative for SARS-CoV-2 PCR at least 24 hours apart.

Data collection

An electronic case report form was constructed in each region and merged for analysis. Physician-in-charge prospectively collected the clinical and laboratory data of each patient and entered into their regional centralized database, which was verified by the team leader. Information of these databases was combined for detailed analysis. The principal investigator would contact the corresponding doctors-in-charge for clarifications when necessary. Data including age at diagnosis, gender, travel history prior to COVID-19 confirmation, dates of admission and discharge and clinical symptoms were collected. The length of stay was defined as the duration between the dates of admission and discharge from the isolation facilities. All patients were classified into domestic and imported cases based on their travel histories. An imported case was defined by recent travel outside of the country within 2 weeks prior to symptoms onset. All patients were classified into different age categories: 0 to <1 year (infant), 1 to <5 years (pre-school), 5 to <12 years (primary school), and 12 to <19 years (secondary school).

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster Institutional Review Board (Reference number: UW 20-292) and the Research Ethics Board of the Wuhan Children’s Hospital (Reference number: WHCH 2020022). Ethics approval in Korea was obtained from the respective medical facilities as described previously [7].

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses were performed in SPSS version 26 (Armonk, New York, USA). Chi-square exact test was used to compare differences in the clinical symptoms and laboratory results between the Korean, HKSAR, and Wuhan cohorts, or between the different age groups. Fisher exact test was used when the conditions for Chi square were not met. One-way analysis of variances was used to detect differences in the mean age at diagnosis, mean length of hospital stay and laboratory results among the three Asian regions.

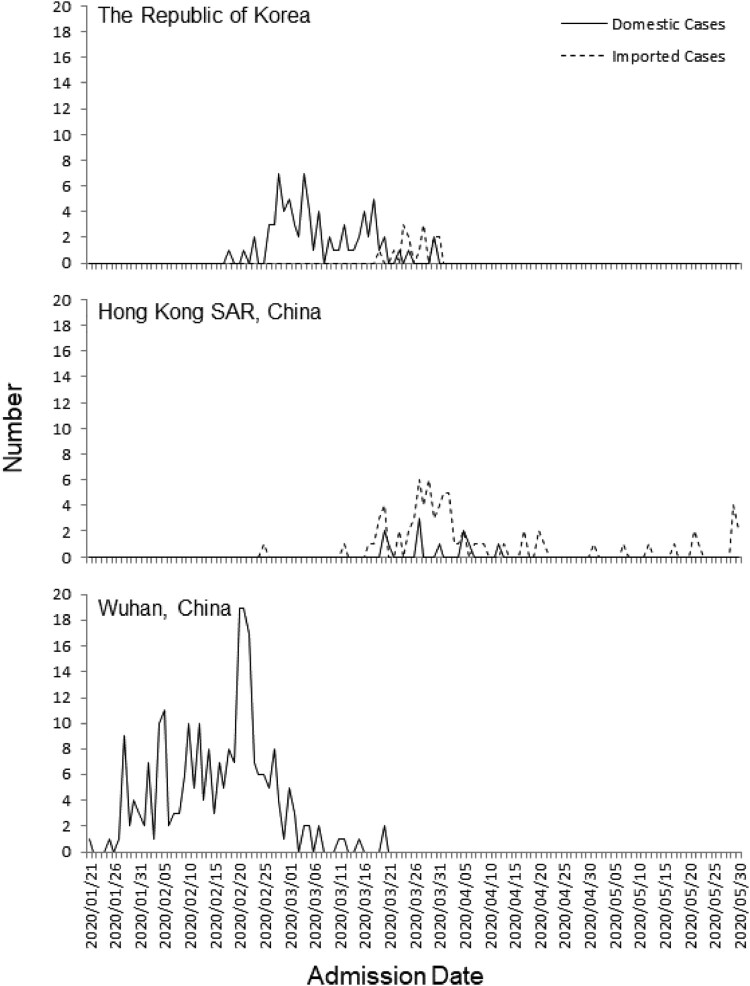

For the comparisons between domestic and imported cases, Chi square test was used to compare clinical symptoms, and unpaired t-test was used to compare mean age at diagnosis, mean length of stay and laboratory results. Multivariate regression analysis was used to adjust for potential confounders. Fisher exact test was used when the conditions for Chi-square were not met. The hospital admission in the Korean, HKSAR, and Wuhan cohorts were presented as plots by admission date. A two tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of pediatric COVID-19 cases between domestic and imported cases during the first wave in Korea, HKSAR, and Wuhan by admission date. Wuhan was first to reach a peak of COVID-19 pediatric cases in late February 2020, followed by Korea in mid-March, and HKSAR in late March to early April. The majority of the pediatric patients in HKSAR were imported cases, with admissions peaking in late March. The majority of the pediatric patients in Korea were domestic cases, and admissions peaked in late February to mid-March. In contrast, all pediatric COVID-19 cases in Wuhan were domestic cases. In Wuhan, the Wuhan Children’s Hospital was designated as the medical facility for treating children with COVID-19. All 244 children with COVID-19 admitted to this hospital between January 21 and March 20 were included. In Korea, the first pediatric COVID-19 patient was identified on February 18 [8]. From those admitted to 20 hospitals and two non-hospital isolation facilities up to March 31, 91 pediatric COVID-19 cases were included. In HKSAR, 88 pediatric COVID-19 cases admitted to eight pediatric hospitals between February 25 and May 31 were included.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the admission in domestic and imported pediatric COVID-19 cases in the Republic of Korea, and Hong Kong SAR and Wuhan during the first wave of COVID-19.

Tables 1 and 2 show the comparison of the clinical characteristics and laboratory results of the 423 children with COVID-19 in the Korean, HKSAR, and Wuhan cohorts. Patients from HKSAR were significantly older than in Korea and Wuhan (12.9 vs. 10.8 vs. 6.6 years, p < 0.001, respectively). Significantly more patients from HKSAR had travelled outside of the region prior to COVID-19 confirmation compared to Korea and Wuhan (87.5% vs. 16.5% vs. 0%, p < 0.001, respectively). There were significantly more asymptomatic patients in HKSAR (45.5% vs. 22.0% vs. 20.9%, p < 0.001, respectively). More patients in Wuhan had a fever compared to Korea and HKSAR (40.6% vs. 29.7% vs. 21.6%, p = 0.003, respectively). Patients in Korea and HKSAR reported ageusia (10.8% and 6.8%, respectively) and anosmia (5.4% and 8.0%, respectively). There were some significant differences in the number of patients having cough, sputum, and abdominal pain. No patients developed rashes or signs of Kawasaki Disease or Pediatric Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome Temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (PMIS-TS) compared to several cases reported in Western countries. No patients from Korea and HKSAR required intensive care support. One patient from Wuhan died of intussusception, which has been reported elsewhere [9].

Table 1.

Comparison of the characteristics of pediatric COVID-19 cases in the Republic of Korea, Hong Kong SAR (HKSAR), and Wuhan.

| South Korea N = 91 |

HKSAR N = 88 |

Wuhan N = 244 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| bAge, mean ± SD (years) | 10.8 ± 5.42 | 12.9 ± 5.5 | 6.6 ± 5.0 | <0.001 |

| cMale, n (%) | 53 (58.2) | 51 (58.0) | 150 (61.5) | 0.782 |

| cTravel history, n (%) | 15 (16.5) | 77 (87.5) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| United Kingdom | 4 (4.4%) | 58 (65.9%) | / | |

| USA | 8 (8.8%) | 3 (3.4%) | / | |

| Pakistan | 0 (0) | 10 (11.4%) | / | |

| Spain | 2 (2.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | / | |

| Sweden | 0 (0) | 2 (2.3%) | / | |

| France | 1 (1.1%) | 1 (1.1%) | / | |

| Japan (Princess Diamond) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1%) | / | |

| Singapore + Canada | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1%) | / | |

| bLength of hospital stay, mean ± SD (days) | 17.3 ± 6.1 | 20.7 ± 11.6 | 12.6 ± 5.8 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| cAsymptomatic | 20 (22.0) | 40 (45.5) | 51 (20.9) | <0.001 |

| cFever | 27 (29.7) | 19 (21.6) | 99 (40.6) | 0.003 |

| cMyalgia | 7 (9.1) | 3 (3.4) | 9 (3.7) | 0.120 |

| cRhinorrheaa | 24 (26.7) | 14 (15.9) | N/A | 0.100 |

| cNasal congestiona | 8 (8.9) | 9 (0.2) | N/A | 0.961 |

| cAgeusiaa | 8 (10.8) | 6 (6.8) | N/A | 0.535 |

| cAnosmiaa | 4 (5.4) | 7 (8.0) | N/A | 0.756 |

| cDizziness | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 3 (1.2) | 0.568 |

| cCough | 37 (41.1) | 19 (21.6) | 120 (49.2) | 0.003 |

| cSputum | 29 (32.2) | 9 (10.2) | 25 (10.2) | <0.001 |

| cDiarrhea | 11 (12.2) | 8 (9.1) | 15 (6.1) | 0.179 |

| cAbdominal paina | 6 (7.8) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (1.6) | 0.019 |

| dVomitinga | 6 (6.7) | 1 (1.1) | N/A | 0.118 |

Note: Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Data from Wuhan was not available.

One-way analysis of variances was used.

Chi-square test was used

Fisher exact test was used.

Table 2.

Comparison of the laboratory results of pediatric COVID-19 cases in the Republic of Korea, Hong Kong SAR (HKSAR), and Wuhan.

| South Korea Mean (SD) |

Hong Kong Mean (SD) |

Wuhan Mean (SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total White Cell (109/L) | 5.8 (1.7) | 6.7 (3.2) | 6.9 (2.6) | 0.004 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 (1.3) | 13.8 (1.4) | 12.6 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 271.7 (95.0) | 261.8 (83.0) | 304.6 (100.6) | 0.001 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 2.6 (1.2) | 3.6 (1.8) | 3.3 (5.3) | 0.325 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.4 (2.2) | 3.3 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 12.4 (0.8) | 12.1 (0.8) | 11.1 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| INR | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (Seconds) | 32.3 (5.7) | 30.7 (5.7) | 33.3 (22.5) | 0.814 |

| Creatinine (micromol/L) | 55.9 (20.4) | 59.3 (17.8) | 37.9 (22.7) | <0.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 256 (109.8) | 207 (59.6) | 262.8 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 27.6 (10.4) | 24.8 (4.5) | 39.3 (53.0) | 0.167 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 19.9 (12.6) | 20 (9.7) | 24 (41.0) | 0.516 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 0.2 (0.7) | 1.9 (3.2) | 3.7 (8.5) | 0.001 |

Note: One-way analysis of variances was used. Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Tables 3 and 4 show the in the clinical characteristics and laboratory results differences between domestic and imported cases. All patients from Wuhan were domestic cases. The majority of imported cases in HKSAR returned from the United Kingdom (65.9%) and Pakistan (11.4%); whereas imported cases in Korea returned from the USA (8.8%) and the United Kingdom (4.4%). Imported cases were significantly older than domestic cases (13.4 vs. 7.6 years, p < 0.001). More imported cases were asymptomatic (42.9% vs. 21.7%, p < 0.001), developed less fever (18.7% vs. 38.6%, p < 0.001) and cough (25.3% vs. 46.2%, p < 0.001), but required longer hospital stay (20.1 vs. 13.8 days, p < 0.001). Multivariate regression analysis showed that there was significantly less imported cases developed fever (p = 0.046) after adjusting for age and region of origin. There were no significant differences between imported and domestic cases in terms of lengths of stay, cough and being asymptomatic after the same adjustment.

Table 3.

Comparison of the characteristics of domestic and imported pediatric COVID-19 cases from Republic of Korea, Hong Kong SAR (HKSAR), and Wuhan.

| Domestic cases N = 332 |

Imported cases N = 91 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| bAge, mean ± SD (years) | 7.6 ± 5.3 | 13.4 ± 5.2 | <0.001 |

| dMale, n (%) | 203 (61.1) | 51 (56.0) | 0.399 |

| bLength of hospital stay, mean ± SD (days) | 13.8 ± 6.6 | 20.1 ± 10.9 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms, n (%) | |||

| dAsymptomatic | 72 (21.7) | 39 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| dFever | 128 (38.6) | 17 (18.7) | <0.001 |

| cMyalgia | 16 (5.0) | 3 (3.4) | 0.775 |

| dRhinorrheaa | 21 (24.1) | 17 (18.7) | 0.481 |

| dNasal Congestiona | 7 (8.0) | 10 (11.0) | 0.680 |

| dAgeusiaa | 6 (8.1) | 8 (9.1) | 1.0 |

| dAnosmiaa | 5 (6.8) | 6 (6.8) | 1.0 |

| cDizziness | 3 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 1.0 |

| dCough | 153 (46.2) | 23 (25.3) | <0.001 |

| dSputum | 46 (13.9) | 17 (18.7) | 0.333 |

| dDiarrhea | 24 (7.3) | 10 (11.0) | 0.346 |

| cAbdominal paina | 9 (2.8) | 3 (3.4) | 0.726 |

| cVomitinga | 6 (6.9) | 1 (1.1) | 0.06 |

Note: Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Data from Wuhan was not available.

Unpaired t-test was used.

Fisher exact test was used.

Chi-square test was used

Table 4.

Comparison of the laboratory results of domestic and imported pediatric COVID-19 cases from Republic of Korea, Hong Kong SAR (HKSAR), and Wuhan.

| Domestic cases Mean (SD) |

Imported cases Mean (SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total white cell (109/L) | 6.7 (2.4) | 6.5 (3.1) | 0.534 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.8 (1.5) | 14.0 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 300.3 (99.2) | 252.0 (83.4) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 3.2 (4.8) | 3.4 (1.8) | 0.601 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 3.1 (1.7) | 2.4 (2.1) | 0.002 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 11.1 (1.2) | 12.2 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| INR | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (seconds) | 33.2 (21.8) | 30.9 (5.9) | 0.574 |

| Creatinine (micromol/L) | 41.0 (23.0) | 61.2 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 261.6 (100.5) | 212.6 (70.9) | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 37.2 (48.2) | 25.4 (10.3) | 0.304 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 23.3 (37.1) | 19.4 (9.5) | 0.358 |

| C-Reactive Protein (mg/dL) | 3.0 (7.7) | 1.6 (3.1) | 0.120 |

Note: Unpaired t-test was used. Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Tables 5 and 6 show the differences in the clinical characteristics and laboratory results between different age groups. Significantly more children in the older age group had travel histories, were asymptomatic, and developed myalgia, nasal congestion, and sputum. On the other hand, significantly more children in the younger age group developed fever and cough.

Table 5.

Comparison of the characteristics of children with COVID-19 by different age groups.

| 0 to <1 N = 62 |

1 to <5 N = 67 |

5 to <12 N = 140 |

12 to <19 N = 154 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bMale, n (%) | 36 (58.1) | 36 (53.7) | 87 (62.1) | 95 (61.7) | 0.649 |

| bTravel history, n (%) | 4 (6.5) | 7 (10.4) | 14 (10.0) | 66 (42.9) | <0.001 |

| cLength of hospital stay, mean ± SD (days) | 13.4 ± 7.8 | 13.9 ± 7.0 | 14.0 ± 7.1 | 16.6 ± 8.5 | 0.012 |

| bSymptoms, n (%) | |||||

| Asymptomatic | 4 (6.5) | 13 (19.4) | 43 (30.7) | 51 (33.1) | <0.001 |

| Fever | 31 (50.0) | 34 (50.7) | 43 (30.7) | 37 (24.0) | <0.001 |

| Myalgia | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.3) | 4 (2.9) | 13 (8.6) | 0.026 |

| Runny nosea | 2 (25.0) | 7 (33.3) | 6 (13.3) | 23 (22.1) | 0.306 |

| Stuffy nosea | 2 (25.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (12.5) | 0.046 |

| Ageusiaa | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.5) | 12 (11.7) | 0.316 |

| Anosmiaa | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.3) | 10 (9.7) | 0.273 |

| Dizziness | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.3) | 0.647 |

| Cough | 43 (69.4) | 30 (44.8) | 50 (35.7) | 53 (34.6) | <0.001 |

| Sputum | 11 (17.7) | 5 (7.5) | 16 (11.4) | 31 (20.3) | 0.044 |

| Diarrhea | 8 (12.9) | 6 (9.0) | 7 (5.0) | 13 (8.5) | 0.279 |

| Abdominal paina | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (5.0) | 5 (3.3) | 0.127 |

| Vomitinga | 1 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (4.8) | 0.396 |

Note: Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Data from Wuhan was not available.

Chi-square test was used

One-way analysis of variances was used.

Table 6.

Comparison of the laboratory results of children with COVID-19 by different age groups.

| 0 to <1 Mean (SD) |

1 to <5 Mean (SD) |

5 to <12 Mean (SD) |

12 to <19 Mean (SD) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total white cell (109/L) | 8.0 (3.1) | 7.9 (3.4) | 6.5 (2.2) | 5.8 (1.6) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.6 (1.7) | 12.3 (0.9) | 13.0 (1.2) | 14.0 (1.3) | <0.001 |

| Platelets (109/L) | 374.6 (142.1) | 299.1 (84.8) | 282.5 (82.9) | 257.6 (67.1) | <0.001 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 2.4 (2.4) | 4.1 (10.3) | 3.3 (1.8) | 3.2 (1.4) | 0.216 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 4.8 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.5) | 2.5 (0.9) | 2.0 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Prothrombin time (seconds) | 11.2 (2.2) | 11.1 (1.1) | 11.1 (0.7) | 11.5 (0.9) | 0.220 |

| INR | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.9 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | 0.001 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time (seconds) | 34.3 (9.2) | 32.0 (6.6) | 34.0 (33.8) | 31.5 (4.8) | 0.822 |

| Creatinine (micromol/L) | 26.5 (12.0) | 35.5 (38.2) | 40.6 (10.4) | 61.7 (15.6) | <0.001 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) | 316.8 (90.0) | 310.3 (95.6) | 232.7 (93) | 206.7 (70.3) | <0.001 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/L) | 57.3 (84.5) | 39.3 (16.7) | 34.9 (43.6) | 22.9 (8.3) | <0.001 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/L) | 40.5 (74.7) | 16.0 (8.2) | 19.8 (19.1) | 20.2 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 3.5 (6.1) | 3.1 (9.8) | 2.3 (6.1) | 2.7 (6.7) | 0.729 |

Note: One-way analysis of variances was used. Bold values represent p-value <0.05.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first multi-regional Asian pediatric studies to summarize and compare the clinical characteristics of children infected with coronavirus during the first wave of the COVID-19 outbreak. We also explored the differences between imported and domestic cases and differences between age groups across the three regions.

First, almost all pediatric patients had a mild disease, 26% (111/423) of cases were asymptomatic, and only 34.2% (145/423) of patients developed a fever. A significant number of patients (6.8%– 0.8%) in our cohorts reported having anosmia and ageusia, which are unusual symptoms reported in other case series [10, 11]. There were no deaths, except one patient from Wuhan who died from intussusception, likely unrelated to COVID-19 [10, 11]. Younger children, especially those younger than 1 year old, developed fever, which was in line with other large-scale cohorts. Laboratory results were unremarkable. Although there were statistically significant differences in various laboratory results between groups, it is likely contributed by the age-related variation. A recent European study in April 2020 involving 582 children with COVID-19 showed that 8% of patients required intensive care, 4% required mechanical ventilation, and one patient required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Significantly more children younger than 12 months, being male gender, having pre-existing co-morbidities, and presenting with lower respiratory tract symptoms required intensive care [12]. Similarly, a study from China involving 2143 children with COVID-19 reported the majority of severe and critical cases occurred in children younger than 1 year [13]. Interestingly, none of the 423 children in our Asian cohort or the 2143 children in the study by Dong et al [13] developed Kawasaki Disease, despite it being normally more prevalent in Asia than in the west [14]. Similarly, none reported having Pediatric Inflammatory Multisystem Syndrome Temporally associated with SARS-COV-2 (PIMS-TS), which was reported in several case series from Europe and North America [15–18]. Whether East Asians are genetically non-susceptible to PIMS-TS needs to be investigated with larger-scale observation studies.

Second, the peak of the outbreaks differed in Korea, HKSAR, and Wuhan. Despite being closer to the epicenter of the initial outbreak, the majority of the pediatric cases in HKSAR were imported cases outside of China. The peak of these imported cases in late March occurred within the overall peak of COVID-19 cases in HKSAR [3], which also coincided with the beginning of the outbreak in Europe and with the World Health Organization declaring a pandemic on March 11, 2020 [19]. We found the imported COVID-19 cases were significantly older than the domestic cases. Many were teenage students studying abroad in Europe or North America, who chose to return home as schools and universities closed during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, the peak of COVID-19 outbreaks in Korea and Wuhan were much earlier [13, 20]. The domestic pediatric cases in Korea and Wuhan were significantly younger and had no travel histories, and were therefore more likely to have been from infections in the community.

Third, there were significant differences in the clinical characteristics between imported and domestic cases and between different age groups. More imported cases and older children were asymptomatic and fewer developed fever or respiratory symptoms. Compared to Wuhan, which were all younger domestic cases, HKSAR had the most imported cases and older children with COVID-19. Although all patients were managed under the same admission and discharge criteria, and no paediatric patients in our cohort breached the discharge criteria due to tight bed demands, patients required significantly longer hospital stay in HKSAR than in Wuhan (20.7 ± 11.6 days vs. 12.6 ± 5.8 days, p < 0.001). Furthermore, our analysis demonstrated that travel history remained to be a significant factor associated with the development of fever, after adjustment for age and region of origin. We postulate that this might be related to imported cases of different SARS-CoV-2 strains from different parts of the world in various phases of the pandemic. A recent study showed there was a shift from the initial predominant D614 strain in China to the G614 strain that was dominant in Europe, North America, and Oceana, which eventually found its way to Asia (including China and HKSAR). This study suggested that the G614 strain is associated with a higher viral load, but not an increase in disease severity [21]. Both strains were shown to be effectively neutralized by SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies in convalescent plasma [22]. An in-vitro study also demonstrated that the G614 strain is capable of transmitting more efficiently than the D614 strain, but G614 does not bind more efficiently to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the receptor for SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [23]. Bunyavanich et al. demonstrated there was an age-dependent expression of ACE2 in the nasal epithelium and ACE2 gene expression was lowest in young children, which might explain why children with COVID-19 have less severe illness than adults [24]. Nevertheless, whether the G614 strain is associated with a more insidious infection needs to be further investigated.

Given that 26% of children with COVID-19 in our Asian cohort were asymptomatic, only a third developed a fever, and imported cases were less likely to develop fever, public health measures reducing the risk of community spread need to be continued. Simple measures that appeared to be useful during the SARS epidemic such as temperature screening [25] may not be sufficient for the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared to the high number of asymptomatic COVID-19 cases, the majority of SARS cases presented with fever, but serological study showed asymptomatic SARS carriers were extremely rare [26, 27]. Nevertheless, other measures such the universal use of face masks, border controls, and mandatory self-quarantine policies for travellers returning from high-risk areas should be kept in place until an effective COVID-19 vaccine becomes available [28].

This study needs to be interpreted with the following caveats. First, not all strains of SARS-CoV-2 have been identified. However, the imported cases from March 2020 onwards were predominantly associated with the G614 strain, and epidemiological studies confirmed a shift in the dominant strain in the community. Second, Korean pediatric COVID-19 cases included in this study comprised 14.5% (91/627) of cases up to March 31, 2020 [29], whereas almost all pediatric cases from HKSAR and Wuhan were included in the analysis. Nevertheless, the Korean patients were identified from 22 isolation facilities in different parts of Korea, and the clinical characteristics should be representative of pediatric patients during the first wave of COVID-19 in Korea. Third, specific data, such as gestational age, of affected infants were not included in this study, which may affect the interpretation of their clinical pictures. Finally, pediatric data from European countries and North America were not available for analysis in this study. Future collaborative studies will be needed for a direct comparison of the clinical characteristics of pediatric COVID-19 cases between different ethnicities.

In conclusion, the majority of pediatric COVID-19 cases in Asia were mild and a significant proportion was asymptomatic. Kawasaki disease or PIMS-TS was not seen in our COVID-19 cohort. Compared to domestic cases, significantly more patients returning from overseas were asymptomatic and these imported cases were less symptomatic. Further studies are needed to investigate if the less symptomatic and asymptomatic imported cases are associated with newer strains, and whether this requires further measures to avoid future waves.

Acknowledgements

GT Chua, X Xiong and EH Choi drafted the manuscript. JH Kim, P Ip, MYW Kwan supervised the study. WHS Wong, CSL Chui, X Li performed the statistical analysis. MS Han, SH Chang, BL Jun, EJ Lee, BN Kim, MK Kim, K Doo, JH Seo, YJ Kim, YJ Kim, JY Park, SB Suh, H Lee, EY Cho, DH Kim, JM Kim, HY Kim, SE Park, JK Lee, DS Jo, SM Cho, JH Choi, KJ Jo, YJ Choe, KH Kim, S Chi, ST Tang, H Qin, LS Zhou, P Chen, JSC Wong, KCC Chan, FYS Yau, SY Lam, CCK Chow, TW Wong, V Chan, GWK Poon were responsible for data collection in three regions. YL Lau, GCF Chan, MHK Ho, ICK Wong, PKH Tam, KKW To critically appraised the manuscript. All authors agreed on and finalized the current manuscript. This study was approved by the University of Hong Kong/Hospital Authority Hong Kong West Cluster Institutional Review Board (Reference number: UW 20-292) and the Research Ethics Board of the Wuhan Children’s Hospital (Reference number: WHCH 2020022). Ethics approval in Korea was obtained from the respective medical facilities as described previously.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard ; [cited 2020 Sep 4]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/

- 2.Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung GM, Cowling BJ, Wu JT.. From a sprint to a marathon in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hamer M, Gale CR, Kivimäki M, et al. Overweight, obesity, and risk of hospitalization for COVID-19: A community-based cohort study of adults in the United Kingdom. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(35):21011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xiong XL, Wong KK, Chi SQ, et al. Comparative study of the clinical characteristics and epidemiological trend of 244 COVID-19 infected children with or without GI symptoms. Gut. 2020 May 19. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Götzinger F, Santiago-García B, Noguera-Julián A, et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(9):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han MS, Choi EH, Chang SH, et al. Clinical Characteristics and Viral RNA Detection in Children With Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the Republic of Korea. JAMA Pediatr. 2020 Aug 28:e203988. DOI: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JY, Han MS, Park KU, et al. First pediatric case of coronavirus disease 2019 in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(11):e124–e124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Huang Z, Ying G, et al. Study of the lymphocyte change between COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 pneumonia cases suggesting other factors besides uncontrolled inflammation contributed to multiorgan injury. medRxiv 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.02.19.20024885 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mak PQ, Chung KS, Wong JS, et al. Anosmia and ageusia: Not an uncommon presentation of COVID-19 infection in children and adolescents. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39(8):e199–e200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gane SB, Kelly C, Hopkins C.. Isolated sudden onset anosmia in COVID-19 infection. A novel syndrome? Rhinology. 2020;58(3):299–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Götzinger F, Santiago-García B, Noguera-Julián A, et al. COVID-19 in children and adolescents in Europe: a multinational, multicentre cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 Sep;4(9):653–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong Y, Mo X, Hu Y, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China. Pediatrics. 2020: e20200702.32179660 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Uehara R, Belay ED.. Epidemiology of Kawasaki disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(2):79–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones VG, Mills M, Suarez D, et al. COVID-19 and Kawasaki disease: novel virus and novel case. Hosp Pediatr. 2020 Jun;10(6):537–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toubiana J, Poirault C, Corsia A, et al. Kawasaki-like multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children during the covid-19 pandemic in Paris, France: prospective observational study. Br Med J. 2020;369:m2094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607–1608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verdoni L, Mazza A, Gervasoni A, et al. An outbreak of severe Kawasaki-like disease at the Italian epicentre of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10239):1771–1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mavragani A. Tracking COVID-19 in Europe: Infodemiology Approach. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2):e18941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) in China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41(2):145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 Spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020;182(4):812-827.e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang L, Jackson CB, Mou H, et al. The D614G mutation in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein reduces S1 shedding and increases infectivity. bioRxiv 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.06.12.148726 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;581(7807):221–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bunyavanich S, Do A, Vicencio A.. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2427–2429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan KP. Control of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Singapore. Environ Health Prev Med. 2005;10(5):255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiong X, Chua GT, Chi S, et al. A comparison between Chinese children infected with coronavirus disease-2019 and with severe acute respiratory syndrome 2003. J Pediatr. 2020;224:30–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee PP, Wong WH, Leung GM, et al. Risk-stratified seroprevalence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus among children in Hong Kong. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1156–e1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TWY, et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e279–e288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eastin C, Eastin T.. Epidemiological characteristics of 2143 pediatric patients with 2019 coronavirus disease in China. J Emerg Med. 2020;58(4):712–713. [Google Scholar]