Abstract

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, a group of fluoro-surfactants widely detected in the environment, wildlife and humans, have been linked to adverse health effects. A growing body of literature has addressed their effects on obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. This review summarizes the brief historical use and chemistry of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, routes of human exposure, as well as the epidemiologic evidence for associations between exposure to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and the development of obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. We identified 22 studies on obesity and 32 studies on diabetes, while only 1 study was found for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by searching PubMed for human studies. Approximately 2/3 of studies reported positive associations between per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances exposure and the prevalence of obesity and/or type 2 diabetes. Causal links between per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and obesity, diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease/ non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, however, require further large-scale prospective cohort studies combined with mechanistic laboratory studies to better assess these associations.

Keywords: Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, PFAS, obesity, diabetes, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, epidemiology

Introduction

Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are a group of man-made chemicals that share an aliphatic carbon backbone in which hydrogen atoms have been replaced by fluorine. In perfluoroalkyl substances, carbon atoms are completely saturated by fluorine; while in polyfluoroalkyl substances, carbon atoms are mostly replaced by fluorine, contain at least one perfluoroalkyl moiety CnF2(n+1)−, and still contain some carbon-hydrogen bonds. In both perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, the structures are characterized by the high amount of carbon-fluorine bonds, the forth strongest chemical bond in general and the strongest bond in organic chemistry (O’Hagan 2008). With increasing number of fluorine atoms on one carbon, the bonds become stronger (Lemal 2004). Due to this structural attribute, PFAS are generally stable and chemically inert, being able to withstand heat, acids, bases, reducing agents, oxidants, etc. In addition, the fluorocarbon chains of PFAS are non-polar, and hence highly hydrophobic. At the same time, these chains are highly lipophobic due to the lower ability to form instantaneous dipoles that forms the basis of London dispersion force (Lemal 2004). Additionally, the sulfate or carboxylate “head” groups are hydrophilic, which make PFAS amphipathic and ideal materials for use as surfactants. Because of these traits, PFAS, as well as surfactants and polymers made with the aid of PFAS have been extensively manufactured and used in a wide range of consumer products, including cleaners, fabrics, firefighting foam, food packages, makeup, non-stick products, paints, waxes, as well as in some production facilities, including electronics manufacturing, and oil recovery since the 1940s (Herzke, Olsson, and Posner 2012; Favreau et al. 2017).

As the result of extensive use, PFAS has now widely contaminated the environment through PFAS or fluoropolymer manufacturing (Emmett et al. 2006; Hoffman et al. 2011; Shin et al. 2011; Landsteiner et al. 2014; Hu et al. 2016; Hurley et al. 2016), waste (Sindiku et al. 2013; Allred et al. 2015; Eriksson, Haglund, and Karrman 2017; Lang et al. 2017; Gallen et al. 2018; Hamid, Li, and Grace 2018), aqueous film-forming foam concentrates (AFFF) used at airports, military bases and firefighter training sites (Houtz et al. 2013; Houtz et al. 2016; Hu et al. 2016), waste water treatment plants (Becker, Gerstmann, and Frank 2008a, 2008b, 2010; Becker et al. 2010), and degradation from precursor chemicals (Hagen et al. 1981; Young and Mabury 2010; Butt, Muir, and Mabury 2014; Wang et al. 2015). Drinking water, especially when localized with facilities using PFAS, is one of the primary exposure routes for PFAS. In fact, PFAS has been detected at relatively high concentrations in surface water worldwide (Post, Cohn, and Cooper 2012). Most PFAS are extremely stable and relatively resistant to degradation, which exacerbates their contamination in the environment. Longer chain PFAS, such as C8 PFAS, have been reported to bioaccumulate in wildlife (Houde et al. 2011). The bioaccumulation in animal- and plant-based food, as well as the direct contamination from food packaging, makes food an important route of exposure (Trudel et al. 2008). Alternatively, air, dust, and direct contact with PFAS-treated products, can also potentiate the exposure of PFAS to human. PFAS, especially perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), have been detected in the blood of humans worldwide (Post, Cohn, and Cooper 2012).

PFAS exposures have been extensively reported to induce adverse human health effects on reproduction (Bach et al. 2016), immune system (Chang et al. 2016), endocrine function (Kim et al. 2018), kidney function (Conway et al. 2018), cancer (Chang et al. 2014), metabolic diseases (Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019), and adverse developmental effects in offsprings, such as low birth weight, high incidences of diabetes and increased obesity risk (Heindel et al. 2017). Concerns about potential adverse effects of PFAS, especially the long-chain PFAS, on the environment, wildlife, and humans - led to the phase-out of perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) uses in 2000s. Alternative shorter-chain PFAS have been developed to replace the long-chain PFAS. In this review, we summarize the chemistry and historical uses of PFAS and present a review of the current epidemiology findings on associations between PFAS exposures and the development of metabolic syndrome and related diseases, including obesity, diabetes, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Classification of PFAS

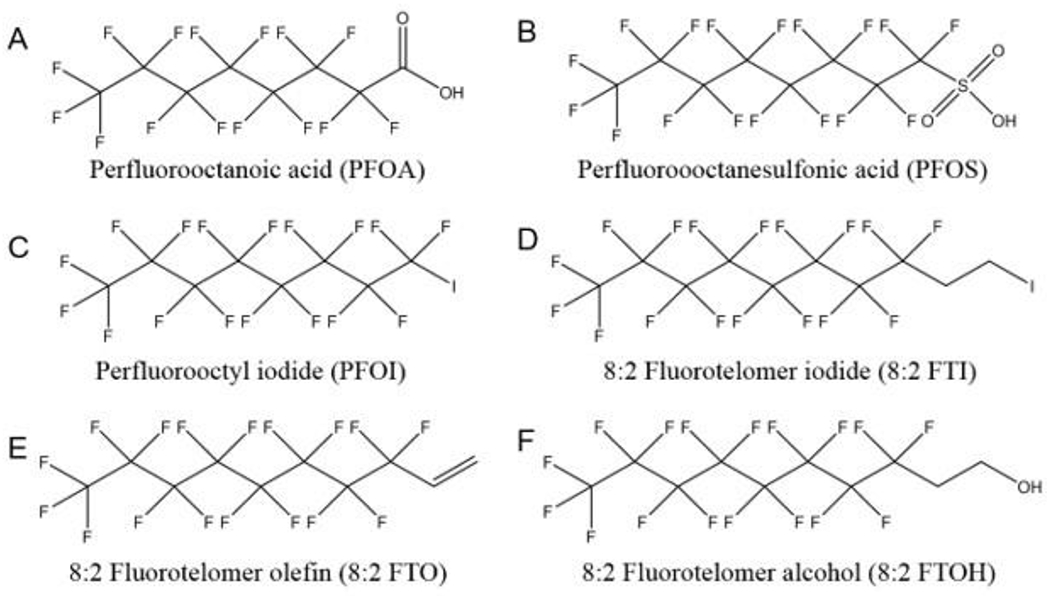

Characterized by their functional groups, PFAS can be placed into a number of chemical families. This section provides an overview of the common names, chemical structures, and some important properties and uses of most well studied PFAS that have been detected in environment and in humans. The structures for selected PFAS are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Structures of selected perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Perfluoroalkyl acids

Perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) are the most studied PFAS due to their extensive use in various industries and their high persistence in the environment and in animals. The PFAA family includes perfluoroalkyl carboxylic, sulfonic, sulfinic, phosphonic, and phosphinic acids.

Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids:

Perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids (PFCAs) are a group of compounds of the formula of CnF(2n+1)COOH. The chemical structures of these compounds consist of a hydrophilic carboxylate “head group” and a hydrophobic fluorocarbon chain. The most studied PFCA is PFOA, C7F15COOH (Figure 1A). PFOA can be synthesized by two major chemical processes, electrochemical fluorination (ECF) and telomerization. ECF is a technology replacing all the hydrogen atoms in an organic raw material with fluorine atoms by electrolysis in hydrogen fluoride (Simons 1949; Karsa 1995). In the early 2000s, a new method was introduced to produce higher percentages of linear products by oxidizing linear perfluorooctyl iodide (PFOI), F(CF2)8I (Figure 1C), which were synthesized by telomerization into PFOA (Ameduri and Boutevin 2004). PFOA, commonly used as its ammonium salt, ammonium perfluorooctanoate (APFO), which is produced exclusively by ECF, has been used since the 1940s as a surfactant to solubilize fluoromonomers in the manufacture of fluoropolymers, such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) (Ebnesajjad 2013). Perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), C8H17COOH, is another PFCA widely used in its ammonium form in the production of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) (Schué 1999). PFNA is produced mainly from the oxidation of fluorotelomer olefin (Buck et al. 2011).

In the recent decade, production of PFOA and its related precursors has been substantially reduced. In 2006, eight leading manufacturers of PFAS were invited by the US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) to join a global stewardship program aiming to achieve 95 % reduction in both emission and product content levels of PFOA, related higher molecular weight homologue chemicals and their precursor chemicals by 2010, and to eliminate these chemicals from emissions and products by 2015.

Besides their major use in the fluoropolymer industry, PFCAs are also considered the final biodegradation product of some precursor PFAS, especially fluorotelomer-based products including fluorotelomer alcohol, fluorotelomer olefin, fluorotelomer iodides, etc. (Hagen et al. 1981; Dinglasan et al. 2004; Frömel and Knepper 2010). It has been estimated, however, that ~80 % of PFCAs released to the environment are directly from the fluoropolymer production (Prevedouros et al. 2006).

Perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids:

Perfluoroalkyl sulfonic acids (PFSAs) are another group of major PFAAs. PFOS (Figure 1B), the 8 carbon PFSA, is the most used and well-studied among all the PFSAs. In 1949, the 3M company started to synthesize PFOS by the degradation of the precursor perfluorooctane sulfonyl fluoride (POSF) produced by ECF, and it is also produced by telomerization (Lehmler 2005). PFOS was later detected globally in wildlife and humans, and the biological half-life of PFOS was reported to be 5.4 years (Olsen et al. 2007; Li et al. 2018). Meanwhile, correlations were reported between blood serum levels of PFOS and the development of various diseases (Chang et al. 2014; Bach et al. 2016; Chang et al. 2016; Heindel et al. 2017; Kim et al. 2018). 3M announced the phase out of C8-based PFAS chemicals in early 2000s. In 2009, PFOS-based compounds were listed in Annex B of the Stockholm Convention on persistent organic pollutants. Perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), the 8 carbon PFSA and its salt are also used as a replacement for PFOS. However, the estimated half-life of PFHxS in human is equivalent to or even longer than PFOS (Olsen et al. 2007; Li et al. 2018). Thus, PFHxS was added to the candidate list of Substances of Very High Concern (SVHC) by the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) in 2007.

Since 2003, 3M started to use perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS) as a replacement of PFOS/PFHxS-based chemicals. PFBS is the 4 carbon PFSA with a half-life in humans of about a month (Olsen et al. 2009), which is significantly shorter than PFOS and PFHxS. In the last decade, the levels of PFBS detected in the environment, wildlife and human blood serum have been increasing (Hölzer et al. 2008; Glynn et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2013; Ruan et al. 2015; Lam et al. 2016), which poses a concern about the potential adverse effects on public health.

Other perfluoroalkyl acids:

Besides PFCAs and PFSAs, the environmental occurrence and detection in humans of perfluoroalkyl sulfinic acids (PFSIAs), perfluoroalkyl phosphonic acids (PFPAs) and perfluoroalkyl phosphinic acids (PFPIAs) are also increasing (D’Eon J et al. 2009; Ahrens and Ebinghaus 2010; Lee and Mabury 2011). PFSIAs are the biodegradation products of some precursors chemicals, including N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamidoethanol (N-EtFOSE) (Boulanger et al. 2005; Rhoads et al. 2008), while PFPAs and PFPIAs are widely used surfactants in various industries (Howard and Muir 2010).

Fluorotelomer-based chemicals

Fluorotelomers are a group of oligomers with multiple perfluoroalkyl moieties, synthesized by telomerization (Ameduri and Boutevin 2004). Some of these compounds have recently become of interest as they are recognized as the environmental precursors of PFCAs (Hagen et al. 1981; Dinglasan et al. 2004; Young and Mabury 2010; Butt, Muir, and Mabury 2014), although the contribution of these precursors to the total human exposure was reported to be variable among different PFCAs.

Perfluoroalkyl iodides (PFAIs), also known as Telomer A, with a common formula of CnF2n+1I are major raw materials in the production of PFAS-based surfactants by telomerization. They are usually obtained by the reaction between a shorter PFAI, the telogen, and tetrafluoroethylene (CF2=CF2), the taxogen. PFAIs are the most important precursors of fluorotelomer-based chemicals including fluorotelomer iodides, fluorotelomer alcohol and fluorotelomer olefin (Lehmler 2005). By inserting ethylene in the structure, n:2 fluorotelomer iodides (n:2 FTIs), CnF2n+1CH2CH2I, is obtained. The n:2 FTIs serve as the intermediate products in the synthesis of the n:2 fluorotelomer alcohols (n:2 FTOHs), as well as certain PFAS. The n:2 fluorotelomer olefins (n:2 FTOs), CnF2n+1CH=CH2, are synthesized by dehydrohalogenation of n:2 FTIs. As stated above, PFAS, for example PFNA, can be produced by the oxidation of the respective fluorotelomer olefin. The n:2 FTOs are also the byproducts of the synthesis of several fluorotelomer-based chemicals from n:2 FTIs. The n:2 fluorotelomer alcohols (n:2 FTOH), CnF2n+1CH2CH2OH, are the precursors of their acrylic and methacrylic esters, which can be used to form fluorinated polymers providing water and oil repellency (Rao and Baker 1994). These polymers are used in textile, paper and leather industry. The phosphoric mono- and di-esters of FTOH, which are also produced from FTOH, have been used as oil-proof food packaging (Begley et al. 2008; Yuan et al. 2016). In humans, n:2 FTOHs have been reported to be metabolized into PFCAs (Martin, Mabury, and O’Brien 2005; Henderson and Smith 2007), which could induce adverse effects.

Sources and pathways of human exposure

Exposure to PFAS can occur through a variety of sources and pathways, including but not limited to drinking water, food, indoor air and dust. Water contamination is considered one of the major sources, especially those near certain locations including industrial sites, military fire training sites, and wastewater treatment plants (Emmett et al. 2006; Vestergren and Cousins 2009; Egeghy and Lorber 2010; Hu et al. 2016). In a US national research project to determine the contaminants in drinking water, 50 % of samples were determined to contain more than two PFAS and 72 % of the detections occurred in ground water samples (Guelfo and Adamson 2018). Water supplies for 6 million US residents exceed US EPA lifetime advisory levels for PFOS and PFOA, which is 70 ng/L, according to a US national spatial analysis of PFAS concentrations in drinking water from 2013-2015 (Hu et al. 2016). In the last decades, while the detection levels of long chain PFAS, including PFOS and PFOA, have been declining, alternative PFAS, such as PFBS, are increasingly detected in the drinking water (Zhou et al. 2013; Ruan et al. 2015; Houtz et al. 2016).

Dietary intake is another important source of PFAS exposure. PFAS contamination in food accounts for the majority of non-occupational exposure to PFAS among all the contributing factors according to modeling studies (Gebbink, Berger, and Cousins 2015; Papadopoulou et al. 2017). Considering PFAS exposure from all potential exposure routes, Fromme et al. (Fromme et al. 2009) estimated that food accounts for over 90 % of PFOS/PFOA exposure. Recently, more individual-based daily PFAS intake studies further supported the conclusion that food is the main contributor of PFAS in humans (Tittlemier, Pepper, and Edwards 2006; Tittlemier et al. 2007; Haug et al. 2011; Vestergren et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2018; Jain 2018b). The most abundant individual PFAS in food are PFOA, PFOS and PFHxS according to research comparing multiple dietary assessment methods; PFOS is the main contributor in solid food, while PFOA contributes the most in liquid food (Papadopoulou et al. 2017).

Multiple causes can lead to the contamination of food by PFAS. As PFAS are bio-accumulative and persistent in environment, food derived from animals, in particular seafood, may contain PFAS due to the exposure of animals to the environment. Plant-based food can also be contaminated by being watered by PFAS contaminated water or grown in soil amended by contaminated biosolids. Direct exposure to food packaging can be another possible cause of contamination, as a great number of PFAS are widely used in food packaging as oil and/or water repellents, especially in fast food packaging (Begley et al. 2005; Tittlemier, Pepper, and Edwards 2006; Herzke, Olsson, and Posner 2012; Martinez-Moral and Tena 2012; Poothong, Boontanon, and Boontanon 2012; Yuan et al. 2016). The migration of PFAS from food packaging to food has also been extensively reported (Begley et al. 2005; Begley et al. 2008). Interestingly, the dietary exposure of PFAS is correlated with high consumption of fats, oils, eggs, milk, as well as foods in paper containers (Tian et al. 2018). PFOA residues in PTFE-coated non-stick cookware could likewise be a potential source of PFAS exposure through food, although it is generally not considered significant (Schlummer et al. 2015). Besides these dietary sources, the accumulation of PFAS in human milk, which is the most important source of PFAS exposure for infants, has also been well-studied, and a growing body of literature has suggested a link between postnatal exposure to PFAS and health effects in childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Sundstrom et al. 2011; Antignac et al. 2013; Kang et al. 2016; Lee et al. 2018; Macheka-Tendenguwo et al. 2018; Nyberg et al. 2018).

In addition to drinking water and food, it has been reported that humans can also be exposed to PFAS by indoor air, indoor dust, and direct contact with PFAS-treated consumer products (Harrad et al. 2010; Fraser et al. 2012), which could account for up to 50 % of PFAS exposure in certain individuals (Haug et al. 2011). It has also been suggested that the exposure of PFAS to pregnant women might also induce exposure of PFAS to embryos and fetus in placenta during gestation (Inoue et al. 2004; Apelberg et al. 2007; Fei et al. 2007; Midasch et al. 2007).

Along with the trend of restricting long chain PFAS production and use in the past decade, the blood serum levels of long chain PFAS, including PFOS and PFOA, have been reported to be decreasing globally, especially in Western countries and Japan (Olsen et al. 2012; Okada et al. 2013; Jain 2018a; Tsai et al. 2018; Shu et al. 2019). However, the concentration of the replacements of these long chain PFAS, for example a four-carbon cognate PFBS, is increasing over the same timeframe (Glynn et al. 2012), which calls for further investigation on their safety.

Epidemiologic evidences

Methods

A review of pertinent literature was performed by searching PubMed and Web of Science for studies on perfluorinated compounds and obesity, diabetes or non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Three search terms were used. The first term was comprised of “PFAS”, “PFC”, OR an extensive list of specific PFAS. The second term was comprised of diseases including “obesity”, “diabetes”, “non-alcoholic fatty liver disease” OR “non-alcoholic steatohepatitis” and related terms that have been used often as markers of these diseases in epidemiologic study, which were selected based on author’s knowledge of the topic and key terms from known research. Related terms include “overweight”, “waist circumference”, “BMI”, “adiposity”, “blood glucose”, “blood insulin”, “HOMA-IR”, “beta cell function”. The third term was “human” “clinical” OR “epidemiology”. Searches were performed by joining three terms with AND operators. Data were collected from 1966 to March 2019. From the initial search, duplicates were eliminated, and articles were screened by evaluating titles and abstracts. For inclusion in this review, we required original research carried out in humans, providing information on the prevalence of the respective diseases or the markers related to the diseases. A total of 55 articles were included and their full texts were reviewed.

PFAS and obesity

Overall, of the 22 epidemiology publications we found, 15 studies reported positive associations between overweight or obesity and the exposure to at least one PFAS (summarized in Table 1). Among studies that examine obesity/overweight in general populations, at least one PFAS was found to be associated with increased body mass index (BMI), waist circumference or weight gain in three cohort studies (Jaacks et al. 2016; Cardenas et al. 2018; Liu, Dhana, et al. 2018) and three cross-sectional studies (Yang et al. 2018; Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019; Tian et al. 2019).

Table 1.

Summary of epidemiology studies of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances on risk of obesity or overweight in human.

| Study design | Demographics | N | Blood level median/mean* (μg/L)a | Summary of resultsb | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional | German men | 101 | PFOS: 10.5* | Negative association between serum PFOS and BMI in men | (Hölzer et al. 2008) |

| Cohort | Danish mother-child pairs | 1010 | PFOS: 33.4; PFOA: 5.21 |

Negative association between maternal PFOS/PFOA and weight at 12 months | (Andersen et al. 2010) |

| Cross-sectional | US aged 12-80 | 2094 | PFOS: 21.0; PFOA: 3.9; PFHxS: 1.8; PFNA: 1.0 |

No association between serum PFOS/PFOA/PFHxS/PFNA and BMI | (Nelson, Hatch, and Webster 2010) |

| Cohort | Danish mother-child pairs | 665 | PFOS: 21.5; PFOA: 3.7; PFNA: 0.3; PFOSA: 1.1 |

Positive association between maternal PFOA and increased BMI and waist circumference of female offsprings at 20 years of age; No association in male offsprings or other PFAS | (Halldorsson et al. 2012) |

| Cohort | British mother-daughter pairs | 447 | PFOS: 19.6; PFOA: 3.7; PFHxS: 1.6: |

Association between maternal PFOS and PFOA levels and low birth weight; Positive association between prenatal PFOS and body weight of female offsprings at 20 months, no difference for PFOA or PFHxS |

(Maisonet et al. 2012) |

| Cohort | Danish mother-child pairs | 811 | PFOS: 33.4; PFOA: 5.21 |

No association between maternal PFOS/PFOA and overweight at 7 years of age | (Andersen et al. 2013) |

| Cohort | Dutch mother-child pairs | 148 | PFOS: 1.60; PFOA: 0.87 |

No association between maternal PFOS/PFOA and weight at 12 months | (de Cock et al. 2014) |

| Cohort | Greenlandic and Ukrainian mother-child pairs | 1022 | PFOS Greenland: 20.2; PFOS Ukraine: 5.0; PFOA Greeland: 1.8; PFOA Ukraine: 1.0 |

No association between PFOS/PFOA and overweight; Significant increase in relative risks of having waist-to-height ratio>0.5 at 5 to 9 years | (Høyer et al. 2015) |

| Cohort | US mother-child pairs | 204 | PFOA: 5.3 | Positive association between maternal PFOA concentration and offsprings adiposity at 8 years of age, and BMI gain from age 2-8 | (Braun et al. 2016) |

| Cohort | Danish children | 201/202 | PFOS: 44.5 | Positive association between serum PFOS at 9 and overweight at 15 and 21 | (Domazet et al. 2016) |

| Cohort | US pregnant women with BMI< 25 kg/m2 | 218 | PFOS: 14.8* | Positive association between pre-pregnant serum PFOS and gestational weight gain | (Jaacks et al. 2016) |

| Cohort | US mother-child pairs | 1006/876 | PFOS: 24.8; PFOA: 5.6; PFHxS: 2.4; PFNA 0.6 |

Positive association between maternal PFOS, PFOA, PFNA, and PFHxS and mid-childhood (median, 7.7 years) overweight in female offsprings; No association in male or early childhood (median, 3.2 years) | (Mora et al. 2016) |

| Cohort | UK mother-daughter pairs | 359 | PFOS: 19.7; PFOA: 3.7; PFHxS: 1.6; PFNA: 0.5 |

Positive association between PFOA and body fat percentage of female offsprings of mothers at middle education level, and negative association for highest education group; No overall association between maternal PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS or PFNA and body fat percentage at 9 years of age | (Hartman et al. 2017) |

| Cohort | Faroese mother-child pairs | 444 | PFOS: 8.04*; PFOA: 1.37*; PFHxS: 0.19*; PFNA: 0.67*; PFDA: 0.26* |

Positive association between postpartum maternal PFOS/PFOA and overweight in offsprings at 5 years of age; No association in PFHxS, PFNA, and PFDA | (Karlsen et al. 2017) |

| Cohort | US adults | 210 | PFOS: 28.4; PFOA: 12.7; PFHxS: 2.65; PFNA: 0.50; PFDA: 0.10; PFOSA: 0.20; Me-PFOSA: 0.85; Et-PFOSA: 2.05 |

No association between serum levels of 8 PFASs and BMI | (Blake et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | US adults | 957 | Total PFAS: 40.6* | Positive association between total serum PFASs and weight and hip girth | (Cardenas et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | Norwegian and Swedish mother-child pairs | 412 | PFOS Norway: 9.62; PFOS Sweden: 16.3; PFOA Norway: 1.64; PFOA Sweden: 2.33 |

Positive association between maternal PFOS/PFOA concentration and odds of child overweight/obesity at 5 years of age, with stronger odds among Norwegian children | (Lauritzen et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | US overweight adults | 621 | PFOS: 27.2; PFOA: 5.2; PFHxS: 3.1; PFNA: 1.6; PFDA: 0.4 |

Positive association between baseline PFOS, PFOA, PFHxS, PFNA and PFDA and a greater weight re-gain in a diet-induced weight loss setting, primarily in women | (Liu et al. 2018) |

| Cross-sectional | Korean adults | 786 | PFOS: 12.4*; PFOA: 4.94*; PFHxS: 8.38*; PFNA: 2.03*; PFDA: 1.29* |

No association between serum levels of 13 PFASs and BMI | (Seo et al. 2018) |

| Cross-sectional | Chinese male adults | 148 | PFOS: 3.00; PFOA: 1.90; PFHxS: 3.80; PFNA: 0.50; PFDA: 0.40; PFUnDA: 0.30 |

Positive association between serum PFOA/PFNA and increased BMI | (Yang et al. 2018) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults | 2975 | PFOS: 8.4; PFOA: 2.8; PFHxS: 1.6; PFNA: 1.0; PFUnDA: 0.1 |

Positive association between serum PFNA and increased waist circumference; Negative association between serum PFUnDA and waist circumference |

(Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019) |

| Cross-sectional | Chinese adults | 1612 | PFOS: 24.2; PFOA: 6.2; PFHxS: 0.71; PFNA: 1.96; PFDA: 0.86 |

Positive association between serum PFOS, PFOA, PFNA and PFDA and overweight and waist circumference | (Tian et al. 2019) |

PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFHxS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; PFDA, perfluorodecanoic acid; PFOSA, perfluorooctane sulfonamide; Me-PFOSA, 2-(N-methyl perfluorooctane sulfonamide) acetic acid; Et-PFOSA, 2-(N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamide) acetic acid. Numbers are medians unless marked with * which represents means.

BMI, body mass index.

Blood levels of PFOS were positively correlated with markers of obesity (BMI or waist circumference); when median/mean levels of PFOS is higher than 25.0 ng/ml, 3 out of 4 studies reported positive association between PFOS levels and markers of obesity (Domazet et al. 2016; Blake et al. 2018; Liu, Dhana, et al. 2018; Tian et al. 2019), while when PFOS level is lower than 25.0 ng/ml, none reported positive association (Table 1). In addition, Jaacks et al. (Jaacks et al. 2016) reported the positive association between pre-pregnant serum PFOS level (with mean 14.81 ng/ml) and gestational weight gain.

Blood levels of PFOA were relatively lower than that of PFOS; median/mean of 1.9-12.7 ng/ml (Table 1). Among 8 studies reporting, no apparent dose response between PFOA and markers of obesity were observed; 3 reported positive association between blood levels of PFOA and weight gain/regain (Liu, Dhana, et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2018; Tian et al. 2019), while 5 reported no association (Nelson, Hatch, and Webster 2010; Høyer et al. 2015; Blake et al. 2018; Seo et al. 2018; Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019).

Positive associations of body weight were also reported on other commonly used PFAS. Among them, the most significant association was PFNA; 4 reports of positive association between blood levels of PFNA and obesity markers (Liu, Dhana, et al. 2018; Yang et al. 2018; Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019; Tian et al. 2019), while 3 others reported no association between them (Nelson; Blake; Seo). The levels of PFHxS were not associated with obesity markers, with an exception reporting positive association with weight regain and PFHxS (Liu). Other PFAS (PFOSA, PFDA, PFOSA and PFUnDA) had limited publications on contribution to obesity markers, with one reporting negative association between serum levels of PFUnDA and waist circumference (Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019).

Prenatal exposure to PFAS is another major focus of epidemiology study concerned with overweight outcomes or obesity. Several studies reported a positive correlation between maternal PFAS exposure and obesity or overweight in children at school age in Europe (Høyer et al. 2015; Hartman et al. 2017; Lauritzen et al. 2018) and US (Braun et al. 2016; Mora et al. 2016).

There are 10 studies reported potential association between blood levels of PFOS and outcome from offsprings with median/mean blood levels of PFOS ranged between 1.60 to 33.4 ng/ml (Table 1). Among them, two reported negative association between PFOS levels and weight at birth or 12 months age (Andersen et al. 2010; Maisonet et al. 2012). However, a follow-up study by Andersen et al. (2013) reports that an inverse association between higher PFOS maternal exposure and weight and BMI in the first year was diminished to no association when they were at the age of seven (Andersen et al. 2013). Among other studies with relatively higher serum PFOS levels (>20.0 ng/ml), 2 reported increased weight or waste-to-hip ratio (Høyer et al. 2015; Mora et al. 2016), while 2 reported no association between PFOS levels and weight of offsprings (Halldorsson et al. 2012; Andersen et al. 2013). However, a report by Lauritzen et al. (Lauritzen et al. 2018) compared the serum levels of PFOS in Norwegian and Swedish, where both group had relatively lower levels of PFOS levels (9.62 ng/ml for Norwegian and 16.3 ng/ml for Swedish) with positive associations to weight at 5 years old, they reported stronger odds of this correlation among Norwegian children even though maternal levels of PFOS was lower than that of Swedish. It is also important to point out that, two reported positive associations of PFOS levels and weight outcome limited to female offsprings (Maisonet et al. 2012; Mora et al. 2016).

The correlation between blood levels of maternal PFOA and obesity related outcome of offsprings were also reported (Table 1). The range of blood levels of PFOA are 0.87-5.6 ng/ml with 6 reported positive association between levels of PFOA and obesity markers (Halldorsson et al. 2012; Høyer et al. 2015; Braun et al. 2016; Mora et al. 2016; Karlsen et al. 2017; Lauritzen et al. 2018), while others reported negative association between PFOA and offsprings weights (Andersen et al. 2010; Maisonet et al. 2012) or no correlations (Andersen et al. 2013; de Cock et al. 2014; Hartman et al. 2017). Again, Similar to PFOS, a follow-up study by Andersen et al. (2013) reports that the negative correlation between maternal PFOA and weight at 12 month was disappeared when offsprings were 7 years old (Andersen et al. 2013). In addition, there were sex-dependent effects of PFOA and weight, which is limited to female offsprings but not males (Halldorsson et al. 2012; Mora et al. 2016).

There were 4 reports of maternal blood levels of PFHxS and PFNA on markers of obesity in offsprings, where both maternal levels of PFHxS and PFNA were positively associated with offsprings weight gain only in females, but not males (Mora et al. 2016), while 3 reported no correlation between PFHxS and PFNA and offsprings obesity markers. No association were reported between offsprings health and serum maternal PFOSA (Halldorsson et al. 2012) or postpartum maternal level of PFDA (Karlsen et al. 2017).

To summarize, obesity and overweight have been correlated with PFAS exposure to general populations, as well as maternal and childhood exposure. Although it may not be conclusive, there is indication of a positive association between PFAS exposure and overweight or obesity, which warrants further investigation.

PFAS and diabetes

Among 32 publications identified, 21 reported positive association between PFAS exposure and prevalence of diabetes (type 1, type 2, or gestational diabetes) or related markers (summarized in Table 2). There were 16 reports of blood levels of PFOS and markers of glucose homeostasis (Table 2). Blood levels of PFOS were varied greatly, with ranges from 0.49-41.5 ng/ml. Among 6 studies with PFOS levels greater than 20 ng/ml, 3 reported positive association between PFOS and increased markers of diabetes (i.e. increased insulin resistance, insulin, glucose or risk of developing type 2 diabetes) (Timmermann et al. 2014; Sun et al. 2018; Alderete et al. 2019). However, 10 studies with lower than 20 ng PFOS/ml, only 3 reported the positive association between PFOS and risk of diabetes, including risk for type 1 diabetes (Predieri et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016; Su et al. 2016).

Table 2.

Summary of epidemiology studies of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances on risk of altered glucose metabolism in human.

| Study design | Demographics | N | Blood level median/mean* (μg/L)a | Summary of resultsb, c | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort | US Dupont workers | 6027 | N/A | Mortality associated with diabetes significantly increases in workers in polymer production plant | (Leonard et al. 2008) |

| Cross-sectional | US adolescents and adults | 474+969 | PFOS adolescents: 22.4*; PFOS adults: 24.3*; PFOA adolescents: 4.53*; PFOA adults: 4.39*; PFNA adolescents: 0.70*; PFNA adults: 0.81* |

Negative association between serum PFNA and beta cell function in adolescents; Positive association between serum PFOS/PFOA and beta cell function in adults | (Lin et al. 2009) |

| Cohort | US 3M workers | 3993 | N/A | Mortality associated with diabetes significantly increases in workers in polymer production plan | (Lundin et al. 2009) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults | 13922 | PFOA: 28.1 | No association between serum PFOA and type 2 diabetes prevalence and fasting glucose | (MacNeil et al. 2009) |

| Cross-sectional | US aged 12-80 | 2094 | PFOS: 21.0; PFOA: 3.9; PFHxS: 1.8; PFNA: 1.0 |

No association between serum PFOS/PFOA/PFHxS/PFNA and HOMA-IR | (Nelson, Hatch, and Webster 2010) |

| Cross-sectional | Canadian adults | 3496 | PFOS: 8.40*; PFOA: 2.46*; PFHxS: 2.18* |

No association between serum PFOS/PFOA/PFHxS and blood insulin, glucose and HOMA-IR | (Fisher et al. 2013) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults | 32254 | N/A | No association between estimated cumulative serum PFOA and type 2 diabetes prevalence | (Karnes, Winquist, and Steenland 2014) |

| Cross-sectional | Swedish elderly aged 70 | 1016 | PFOS:13.2; PFOA: 3.3; PFHxS: 2.1; PFNA: 0.7; PFUnDA: 0.3; PFOSA: 0.11 |

Non-linear relationship between serum PFNA and type 2 diabetes prevalence; No association between PFASs and HOMA-IR | (Lind et al. 2014) |

| Cohort | Overweight Danish children aged 8-10 | 499 | PFOS: 41.5; PFOA: 9.3 |

Positive association between serum PFOS/PFOA and blood insulin/insulin resistance | (Timmermann et al. 2014) |

| Case-control | Italian children aged 2-14 | 44 | PFOS control: 0.49; PFOS T1DM: 0.95 |

Positive association between serum PFOS and type 1 diabetes prevalence | (Predieri et al. 2015) |

| Cohort | US Dupont workers | 3713 | PFOA: 113 | Significant positive trend for diabetes onset with PFOA | (Steenland, Zhao, and Winquist 2015) |

| Case-control | US pregnant women | 258 | PFOA non-GDM: 3.07*; PFOA GDM: 3.94* |

Positive association between serum PFOA and gestational diabetes prevalence | (Zhang et al. 2015) |

| Cross-sectional | US male adults aged > 50 | 154 | PFOS: 19.0; PFOA: 2.50; PFHxS: 1.80; PFNA: 1.40; PFDA: 0.52; PFUnDA: 0.29; PFHpS: 0.49 |

Positive association between serum PFNA/PFUnDA/PFDA and the prevalence of prediabetes or diabetes | (Christensen et al. 2016) |

| Case-control | US adults and children aged > 13 | 66899 | PFOS control: 23.1*; PFOS T1DM: 21.8*, PFOS T2DM: 25.2*; PFOA control: 82.3*; PFOA T1DM: 68.4*, PFOA T2DM: 92.8*; PFHxS control: 5.2*; PFHxS T1DM: 3.4*, PFHxS T2DM: 3.8*; PFNA control: 1.6*; PFNA T1DM: 1.4*, PFNA T2DM: 1.5* |

Negative association between serum PFOS/PFOA/ PFHxS/PFNA and type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes | (Conway, Innes, and Long 2016) |

| Cohort | Danish children | 201/202 | PFOA: 9.70 | Negative association between serum PFOA at 9 and beta cell function at 15 | (Domazet et al. 2016) |

| Double-blind trial | Korean elderly aged > 60 | 141 | PFOS: 9.30; PFDoDA: 0.25 |

Positive association between serum PFOS/PFDoDA and HOMA-IR index | (Kim et al. 2016) |

| Cross-sectional | Taiwanese adults | 571 | PFOS: 3.2; PFOA: 8.0; PFNA: 3.8; PFUnDA: 6.4 |

Positive association between serum PFOS and diabetes prevalence; Negative association between PFOA/PFNA/PFUnDA and diabetes prevalence | (Su et al. 2016) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults with high diabetes risk | 975 | PFOS: 26.4*; PFOA:4.8* |

Positive association between serum PFOS/PFOA and beta cell function; Positive association between PFOS/PFOA and HOMA-IR | (Cardenas et al. 2017) |

| Cohort | US children | 665 | PFOS: 6.2*; PFOA: 4.2*; PFHxS: 2.2*; PFNA: 1.7* |

Negative association between children serum PFOA and HOMA-IR | (Fleisch et al. 2017) |

| Cohort | US adolescents | 402 | PFHxS comparison: 0.53; PFHxS WTCHR: 0.67 | Negative association between serum PFHxS and HOMA-IR | (Koshy et al. 2017) |

| Cohort | Spanish pregnant women | 1204 | PFOS: 5.77*; PFOA: 2.31*; PFHxS: 0.55*; PFNA: 0.64* |

Positive association between serum PFOS/PFHxS and gestational diabetes prevalence | (Matilla-Santander et al. 2017) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults | 7904 | PFOA male: 4.50*; PFOA female: 3.46*; PFOS male: 20.8*; PFOS female: 14.5*; PFHxS male: 2.88*; PFHxS female: 1.94*; PFNA male: 1.52*; PFNA female: 1.30* |

Positive association between serum PFOA and diabetes prevalence in male but not in female or other PFAS | (He et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | Danish pregnant women | 318 | PFOS: 8.31; PFOA: 1.71; PFHxS: 0.30; PFNA: 0.66; PFDA: 0.26 |

Positive association between PFHxS and fasting insulin, fasting glucose and HOMA-IR in women with high GDM risk; positive association between PFNA and fasting insulin and HOMA-β in women with high GDM risk | (Jensen et al. 2018) |

| Cross-sectional | US obese children aged 8-12 | 48 | PFOS: 2.79 PFOA: 0.99 PFHxS: 1.09 PFNA: 0.24 |

No association between serum PFOS/PFOA/PFHxS/PFNA and fasting glucose, insulin and HOMA-IR | (Khalil et al. 2018) |

| Cross-sectional | US adults in NHANES | 1871 | Linear PFOS: 3.70* Branched PFOS: 1.39* Total PFOS: 5.28* Linear PFOA: 1.75* Branched PFOA: 0.08* Total PFOA: 1.86* |

Positive association between serum linear PFOA and branched PFOS and beta cell function | (Liu et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | French women | 71270 | N/A | Non-linear relationship between dietary PFOS/PFOA and type 2 diabetes prevalence | (Mancini et al. 2018) |

| Case-control | US women | 29611 | PFOS: 35.7; PFOA: 4.96; PFHxS: 2.15; PFNA: 0.60; PFDA: 0.13 |

Positive association between plasma PFOS/PFOA and type 2 diabetes prevalence | (Sun et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | Chinese pregnant women | 560 | PFOS: 5.4; PFOA: 7.3 |

Positive association between serum PFOA and HOMA-IR and blood glucose; Negative association between PFOS and blood glucose | (Wang et al. 2018) |

| Cohort | US overweight Hispanic youth aged 8-14 | 40 | PFOS low DM risk: 10.9; PFOS high DM risk: 22.3; PFOA low DM risk: 2.50; PFOA high DM risk:3.35; PFHxS low DM risk: 1.44; PFHxS high DM risk: 1.52 |

Positive association between serum PFOS/PFOA and fasting glucose; Positive association between PFHxS and area under curve in oral glucose tolerance test | (Alderete et al. 2019) |

| Case-control | Swedish adults | 248 | PFDA control: 0.23; PFDA T2DM: 0.21; PFUnDA control: 0.18; PFUnDA T2DM: 0.16 |

Negative association between serum PFDA/PFUnDA and HOMA-IR | (Donat-Vargas et al. 2019) |

| Case-control | Chinese pregnant women | 439 | PFPeA non GDM: 0.05; PFPeA GDM: 0.07; PFHxA non GDM: 0.01; PFHxA GDM: 0.02 |

Positive association between serum short chain PFCAs (PFPeA, PFHxA) and gestational diabetes | (Liu et al. 2019) |

| Cohort | US pregnant women | 2334 | PFOS: 5.21*; PFOA: 1.99*; PFHxS: 0.76*; PFNA: 0.80*; PFDA: 0.27*; PFUnDA: 0.20*; PFHpA: 0.08*; PFDoDA: 0.06* |

Positive association between serum PFOA/PFNA/PFHpA/PFDoDA and gestational diabetes prevalence | (Rahman et al. 2019) |

DM: diabetes mellitus; GDM, gestational diabetes; N/A, not available;PFOS, perfluorooctanesulfonic acid; PFOA, perfluorooctanoic acid; PFNA, perfluorononanoic acid; PFHxS, perfluorohexanesulfonic acid; PFUnDA, perfluoroundecanoic acid; PFDA, perfluorodecanoic acid; PFDoDA, perfluorododecanoic acid; PFHpA, perfluoroheptanoic acid; PFHpS, perfluoroheptane sulfonate; PFOSA, perfluorooctane sulfonamide; PFPeA, perfluoropentanoic acid; PFHxA, perfluorohexanoic acid; WTCHR, World Trade Center Health Registry. Numbers are medians unless marked with * which represents means.

HOMA-IR, Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance.

HOMA-β, Homeostatic Model Assessment of β-cell Function.

Predieri et al. reported that serum concentrations of PFOS were significantly higher in patients with type 1 diabetes than in healthy controls (Predieri et al. 2015), although the significance of this result is limited by its small sample size of 44 children and adolescents. Similarly, Alderete et al. (2019) reported that serum levels of PFOS were higher with subjects with higher diabetes risk (22.3ng/ml) compared to those with lower diabetes risk (10.9 ng/ml). Others reported that serum levels of PFOS were negatively associated with type 1 diabetes in a larger case-control study among 66,899 participants in C8 Health Project (Conway, Innes, and Long 2016). This observation of protective effects of PFAS on type 1 diabetes is further supported by observation that PFOS levels were positively associated with improved beta cell functions (Lin et al. 2009; Cardenas et al. 2017; Liu, Wen, et al. 2018), particularly branched PFOS, but not linear PFOS, even though levels found were relatively lower than others (1.39 ng branched PFOS/ml).

Among studies reporting PFOA and diabetes, there seems to be no clear correlation between serum levels of PFOA and risk of developing either type 1 or type 2 diabetes (Table 2). Reports by Steenland et al. (2015) with Dupont workers had highest mean levels of PFOA in the blood with significant positive correlation of onset of type 2 diabetes, however, Conway et al (2016) reported mean concentrations of 82.3-92.8 ng PFOA/ml in serum with negative association between PFOA and both type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Similarly, studies with mean serum levels of PFOA in 0.99-9.3 ng/ml reporting mixed results on PFOA and markers of glucose homeostasis including risk of developing diabetes (Lin et al. 2009; MacNeil et al. 2009; Nelson, Hatch, and Webster 2010; Fisher et al. 2013; Karnes, Winquist, and Steenland 2014; Timmermann et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2015; Su et al. 2016; Cardenas et al. 2017; Fleisch et al. 2017; He et al. 2018; Khalil et al. 2018; Liu, Wen, et al. 2018; Mancini et al. 2018; Sun et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Alderete et al. 2019; Rahman et al. 2019).

There were 3 reports of PFOA (~1.86-4.82 ng/ml) positively associated in improved beta-cell function, but Domazet et al. (2016), which reported the highest PFOA serum levels among them (9.7 ng/ml), reported the negative association between PFOA and beta-cell function. This may suggest the dose-dependent response of PFOA on beta-cell function, although it is rather limited.

Serum levels of PFHxS were ranged at 0.30-3.8 ng/ml (Table 2). One reported the positive association between serum PFHxS and the area under curve in oral glucose tolerance test (Alderete et al. 2019), 2 reported negative correlation between PFHxS and markers or risk of diabetes (Conway, Innes, and Long 2016; Koshy et al. 2017), while 8 others reported no correlation between PFHxS and risk of diabetes. The majority of studies with PFNA reports no correlation between serum levels of PFNA and risk of diabetes, with exceptions by Christensen et al (Christensen et al. 2016) reporting positive association, while Conway et al (2016) and Su et al (2016) reporting negative correlation between PFNA and diabetes (both Type 1 and 2). It was also reported that PFNA levels were not correlated with beta-cell function (Lin et al. 2009).

There were 6 reports of potential correlation between PFAS and gestational diabetes (Zhang et al. 2015; Matilla-Santander et al. 2017; Jensen et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Rahman et al. 2019). It is apparently not clear if there is direct correlation between serum levels of specific PFAS and the risk of gestational diabetes as many reporting conflicting results or no correlation. However, it was recently reported that serum levels of total short chain PFCAs (C4-C7) were positively associated with gestational diabetes among pregnant Chinese women (Liu et al. 2019).

From the current evidences, it is not possible to make a conclusion that PFAS is positively associated with type 2 diabetes. According to a review summarizing the dose response curves of PFOA in several outcomes, non-monotonic dose-response curves, such as inverse U-shaped dose response curves, were observed in many studies (Post, Cohn, and Cooper 2012; Lind et al. 2014; Mancini et al. 2018). Therefore, the inconsistent results of PFAS exposure and type 2 diabetes risk might be due to the different exposure levels in the respective studies, as different PFOA levels might show different dose responses on diabetes. Similarly, there are rather limited and inconsistent results of the effects of PFAS on type 1 diabetes and gestational diabetes.

PFAS and NAFLD/NASH

PFAS exposure is positively associated with increased serum liver enzyme levels of alanine transaminase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) (Gallo et al. 2012; Yamaguchi et al. 2013; Gleason, Post, and Fagliano 2015; Darrow et al. 2016; Salihovic et al. 2018; Nian et al. 2019), which indicates potential liver damage. Consistently, positive associations were observed between PFHxS/PFOA/PFNA and hepatocyte apoptosis markers in a report involving 200 adults in Ohio (Bassler et al. 2019), including cytokeratin-18, a fatty liver biomarker (Feldstein et al. 2009; He et al. 2017).

PFAS have been extensively reported to disrupt hepatic lipid metabolism and induce non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) or non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in animals, which can more specifically be referred to as Toxicant Associated Fatty Liver Disease (TAFLD) (Wahlang et al. 2012). Proposed mechanisms include the inhibition of fatty acid ß-oxidation, increased fatty acid uptake (Wan et al. 2012; Cheng et al. 2016), and the induction of oxidative stress (Khansari et al. 2017). However, epidemiology findings on the relationship between PFAS and NAFLD/NASH is scarce. Although it was not part of the original literature search, a recent publication by Jin et al. (2020) reported the positive correlation between the development of NASH and the increased concentrations of PFOS and PFHxS, but not PFOA, among 74 US children with physician-diagnosed NAFLD. The increased concentration of PFHxS was also found to be positively associated with liver fibrosis, lobular inflammation, and higher NAFLD activity score (Jin et al. 2020). Another suggestion of positive association was an elevated hazard ratio of enlarged liver, fatty liver and cirrhosis observed among Mid-Ohio Valley Dupont workers (Darrow et al. 2016). However, this positive association was limited to exposure at a 10-year lag, which was based on only 36 self-reported cases (Darrow et al. 2016). Two other occupational studies reported positive trends on non-hepatitis liver disease, but not on NAFLD or NASH (Winquist et al. 2013; Steenland, Zhao, and Winquist 2015). Even though no direct association between PFAS and NAFLD/NASH incidence was reported, PFAS exposure has been consistently reported to be associated with altered lipid profile in blood, including increased triglyceride, cholesterol, low density lipoprotein, and reduced high density lipoprotein (Maisonet et al. 2012; Fitz-Simon et al. 2013; Fletcher et al. 2013; Christensen, Raymond, and Meiman 2019). As obese subjects tend to be more susceptible to PFAS-induced dyslipidemia and NAFLD is well associated with obesity, PFAS exposure might contribute to NAFLD (Jain and Ducatman 2019).

In general, epidemiology data on the relationship between PFAS exposure and NAFLD/NASH are limited. However, even with currently limited evidence, it is important to follow up with additional studies to confirm the role of PFAS and NAFLD in near future.

Conclusion

Accumulating evidence supports the contention that an association between PFAS, especially PFCAs and PFSAs, and the onset or development of metabolic diseases, including obesity, diabetes and NAFLD/NASH, exists. However, inconsistent results can be found in many cases. Therefore, more clinical or epidemiology studies, especially prospective cohort studies, are needed to confirm this contention. There is also a critical need to investigate the potential underlying mechanisms leading to these interactions using in vitro and in vivo models, especially for the shorter chain PFAS that are currently being used significant amounts.

Acknowledgement

This project was in part supported by NIH R01ES028201.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors declare they have no actual or potential competing financial interests.

Reference

- Ahrens L, and Ebinghaus R. 2010. “Spatial Distribution of Polyfluoroalkyl Compounds in Dab (Limanda Limanda) Bile Fluids from Iceland and the North Sea.” Marine Pollution Bulletin 60 (1):145–8. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderete TL, Jin R, Walker DI, Valvi D, Chen Z, Jones DP, Peng C, Gilliland FD, Berhane K, Conti DV, Goran MI, and Chatzi L. 2019. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances, Metabolomic Profiling, and Alterations in Glucose Homeostasis among Overweight and Obese Hispanic Children: A Proof-of-Concept Analysis.” Environment International 126:445–53. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allred BM, Lang JR, Barlaz MA, and Field JA. 2015. “Physical and Biological Release of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Municipal Solid Waste in Anaerobic Model Landfill Reactors.” Environmental Science & Technology 49 (13):7648–56. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b01040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ameduri B, and Boutevin B. 2004. “Chapter 1 - Telomerisation Reactions of Fluorinated Alkenes” In Well-Architectured Fluoropolymers: Synthesis, Properties and Applications, edited by Ameduri Bruno and Boutevin Bernard, 1–99. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen CS, Fei C, Gamborg M, Nohr EA, Sørensen TIA, and Olsen J. 2013. “Prenatal Exposures to Perfluorinated Chemicals and Anthropometry at 7 Years of Age.” American Journal of Epidemiology 178 (6):921–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen CS, Fei C, Gamborg M, Nohr EA, Sørensen TIA, and Olsen J. 2010. “Prenatal Exposures to Perfluorinated Chemicals and Anthropometric Measures in Infancy.” American Journal of Epidemiology 172 (11):1230–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antignac JP, Veyrand B, Kadar H, Marchand P, Oleko A, Le Bizec B, and Vandentorren S. 2013. “Occurrence of Perfluorinated Alkylated Substances in Breast Milk of French Women and Relation with Socio-Demographical and Clinical Parameters: Results of the Elfe Pilot Study.” Chemosphere 91 (6):802–8. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apelberg BJ, Goldman LR, Calafat AM, Herbstman JB, Kuklenyik Z, Heidler J, Needham LL, Halden RU, and Witter FR. 2007. “Determinants of Fetal Exposure to Polyfluoroalkyl Compounds in Baltimore, Maryland.” Environmental Science & Technology 41 (11):3891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach CC, Vested A, Jorgensen KT, Bonde JP, Henriksen TB, and Toft G. 2016. “Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances and Measures of Human Fertility: A Systematic Review.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 46 (9):735–55. doi: 10.1080/10408444.2016.1182117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassler J, Ducatman A, Elliott M, Wen S, Wahlang B, Barnett J, and Cave MC. 2019. “Environmental Perfluoroalkyl Acid Exposures Are Associated with Liver Disease Characterized by Apoptosis and Altered Serum Adipocytokines.” Environmental Pollution 247:1055–63. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AM, Gerstmann S, and Frank H. 2008a. “Perfluorooctane Surfactants in Waste Waters, the Major Source of River Pollution.” Chemosphere 72 (1):115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AM, Gerstmann S, and Frank H. 2008b. “Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in the Sediment of the Roter Main River, Bayreuth, Germany.” Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987) 156 (3):818–20. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AM, Gerstmann S, and Frank H. 2010. “Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate in Two Fish Species Collected from the Roter Main River, Bayreuth, Germany.” Bulletin of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology 84 (1):132–5. doi: 10.1007/s00128-009-9896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AM, Suchan M, Gerstmann S, and Frank H. 2010. “Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate Released from a Waste Water Treatment Plant in Bavaria, Germany.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 17 (9):1502–7. doi: 10.1007/s11356-010-0335-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley TH, Hsu W, Noonan G, and Diachenko G. 2008. “Migration of Fluorochemical Paper Additives from Food-Contact Paper into Foods and Food Simulants.” Food Additives & Contaminant. Part A Chemistry Analysis Control Exposure & Risk Assessment 25 (3):384–90. doi: 10.1080/02652030701513784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Begley TH, White K, Honigfort P, Twaroski ML, Neches R, and Walker RA. 2005. “Perfluorochemicals: Potential Sources of and Migration from Food Packaging.” Food Additives and Contaminants 22 (10):1023–31. doi: 10.1080/02652030500183474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake BE, Pinney SM, Hines EP, Fenton SE, and Ferguson KK. 2018. “Associations between Longitudinal Serum Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Levels and Measures of Thyroid Hormone, Kidney Function, and Body Mass Index in the Fernald Community Cohort.” Environmental Pollution 242:894–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulanger B, Vargo JD, Schnoor JL, and Hornbuckle KC. 2005. “Evaluation of Perfluorooctane Surfactants in a Wastewater Treatment System and in a Commercial Surface Protection Product.” Environmental Science & Technology 39 (15):5524–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun JM, Chen A, Romano ME, Calafat AM, Webster GM, Yolton K, and Lanphear BP. 2016. “Prenatal Perfluoroalkyl Substance Exposure and Child Adiposity at 8 Years of Age: The Home Study.” Obesity 24 (1):231–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck RC, Franklin J, Berger U, Conder JM, Cousins IT, de Voogt P, Jensen AA, Kannan K, Mabury SA, and van Leeuwen SP. 2011. “Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances in the Environment: Terminology, Classification, and Origins.” Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management 7 (4):513–41. doi: 10.1002/ieam.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt CM, Muir DC, and Mabury SA. 2014. “Biotransformation Pathways of Fluorotelomer-Based Polyfluoroalkyl Substances: A Review.” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 33 (2):243–67. doi: 10.1002/etc.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A, Gold DR, Hauser R, Kleinman KP, Hivert MF, Calafat AM, Ye XY, Webster TF, Horton ES, and Oken E. 2017. “Plasma Concentrations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances at Baseline and Associations with Glycemic Indicators and Diabetes Incidence among High-Risk Adults in the Diabetes Prevention Program Trial.” Environmental Health Perspectives 125 (10). doi: 10.1289/ehp1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardenas A, Hauser R, Gold DR, Kleinman KP, Hivert M-F, Fleisch AF, Lin P-ID, Calafat AM, Webster TF, Horton ES, and Oken E. 2018. “Association of Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances with Adiposity.” JAMA network open 1 (4):e181493–e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang ET, Adami HO, Boffetta P, Cole P, Starr TB, and Mandel JS. 2014. “A Critical Review of Perfluorooctanoate and Perfluorooctanesulfonate Exposure and Cancer Risk in Humans.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 44 Suppl 1:1–81. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2014.905767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang ET, Adami HO, Boffetta P, Wedner HJ, and Mandel JS. 2016. “A Critical Review of Perfluorooctanoate and Perfluorooctanesulfonate Exposure and Immunological Health Conditions in Humans.” Critical Reviews in Toxicology 46 (4):279–331. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2015.1122573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WL, Bai FY, Chang YC, Chen PC, and Chen CY. 2018. “Concentrations of Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Foods and the Dietary Exposure among Taiwan General Population and Pregnant Women.” Journal of Food and Drug Analysis 26 (3):994–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.jfda.2017.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Lv S, Nie S, Liu J, Tong S, Kang N, Xiao Y, Dong Q, Huang C, and Yang D. 2016. “Chronic Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) Exposure Induces Hepatic Steatosis in Zebrafish.” Aquatic Toxicology 176:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2016.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KY, Raymond M, and Meiman J. 2019. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Metabolic Syndrome.” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 222 (1): 147–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen KY, Raymond M, Thompson BA, and Anderson HA. 2016. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Older Male Anglers in Wisconsin.” Environment International 91:312–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway B, Innes KE, and Long D. 2016. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Beta Cell Deficient Diabetes.” Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications 30 (6):993–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway B, Badders AN, Costacou T, Arthur JM, and Innes KE. 2018. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Kidney Function in Chronic Kidney Disease, Anemia, and Diabetes.” Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 11:707–16. doi: 10.2147/DMSO.S173809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Eon JC, Crazier PW, Furdui VI, Reiner EJ, Libelo EL, and Mabury SA. 2009. “Perfluorinated Phosphonic Acids in Canadian Surface Waters and Wastewater Treatment Plant Effluent: Discovery of a New Class of Perfluorinated Acids.” Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry 28 (10):2101–7. doi: 10.1897/09-048.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darrow LA, Groth AC, Winquist A, Shin H-M, Bartell SM, and Steenland K. 2016. “Modeled Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) Exposure and Liver Function in a Mid-Ohio Valley Community.” Environmental Health Perspectives 124 (8): 1227–33. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1510391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cock M, de Boer MR, Lamoree M, Legler J, and van de Bor M. 2014. “First Year Growth in Relation to Prenatal Exposure to Endocrine Disruptors—a Dutch Prospective Cohort Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 11 (7):7001–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinglasan MJ, Ye Y, Edwards EA, and Mabury SA. 2004. “Fluorotelomer Alcohol Biodegradation Yields Poly- and Perfluorinated Acids.” Environmental Science & Technology 38 (10):2857–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domazet SL, Grontved A, Timmermann AG, Nielsen F, and Jensen TK. 2016. “Longitudinal Associations of Exposure to Perfluoroalkylated Substances in Childhood and Adolescence and Indicators of Adiposity and Glucose Metabolism 6 and 12 Years Later: The European Youth Heart Study.” Diabetes Care 39 (10):1745–51. doi: 10.2337/dc16-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donat-Vargas C, Bergdahl IA, Tornevi A, Wennberg M, Sommar J, Kiviranta H, Koponen J, Rolandsson O, and Åkesson A 2019. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Risk of Type Ii Diabetes: A Prospective Nested Case-Control Study.” Environment International 123:390–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebnesajjad S. 2013. “7 - Manufacturing Polytetrafluoroethylene” In Introduction to Fluoropolymers, edited by Ebnesajjad Sina, 91–124. Oxford: William Andrew Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Egeghy PP, and Lorber M. 2010. “An Assessment of the Exposure of Americans to Perfluorooctane Sulfonate: A Comparison of Estimated Intake with Values Inferred from Nhanes Data.” Journal Of Exposure Science And Environmental Epidemiology 21:150. doi: 10.1038/jes.2009.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett EA, Shofer FS, Zhang H, Freeman D, Desai C, and Shaw LM. 2006. “Community Exposure to Perfluorooctanoate: Relationships between Serum Concentrations and Exposure Sources.” Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 48 (8):759–70. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000232486.07658.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson U, Haglund P, and Karrman A. 2017. “Contribution of Precursor Compounds to the Release of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) from Waste Water Treatment Plants (Wwtps).” Journal of Environmental Sciences (China) 61:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favreau P, Poncioni-Rothlisberger C, Place BJ, Bouchex-Bellomie H, Weber A, Tremp J, Field JA, and Kohler M. 2017. “Multianalyte Profiling of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Liquid Commercial Products.” Chemosphere 171:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei C, McLaughlin JK, Tarone RE, and Olsen J. 2007. “Perfluorinated Chemicals and Fetal Growth: A Study within the Danish National Birth Cohort.” Environmental Health Perspectives 115 (11):1677–82. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein AE, Wieckowska A, Lopez AR, Liu YC, Zein NN, and McCullough AJ. 2009. “Cytokeratin-18 Fragment Levels as Noninvasive Biomarkers for Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Multicenter Validation Study.” Hepatology 50 (4):1072–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Arbuckle TE, Wade M, and Haines DA. 2013. “Do Perfluoroalkyl Substances Affect Metabolic Function and Plasma Lipids?--Analysis of the 2007–2009, Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) Cycle 1.” Environmental Research 121:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitz-Simon N, Fletcher T, Luster MI, Steenland K, Calafat AM, Kato K, and Armstrong B. 2013. “Reductions in Serum Lipids with a 4-Year Decline in Serum Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorooctanesulfonic Acid.” Epidemiology 24 (4):569–76. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31829443ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisch AF, Rifas-Shiman SL, Mora AM, Calafat AM, Ye XY, Luttmann-Gibson H, Gillman MW, Oken E, and Sagiv SK. 2017. “Early-Life Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Childhood Metabolic Function.” Environmental Health Perspectives 125 (3):481–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher T, Galloway TS, Melzer D, Holcroft P, Cipelli R, Pilling LC, Mondal D, Luster M, and Harries LW. 2013. “Associations between PFOA, PFOS and Changes in the Expression of Genes Involved in Cholesterol Metabolism in Humans.” Environment International 57-58:2–10. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser AJ, Webster TF, Watkins DJ, Nelson JW, Stapleton HM, Calafat AM, Kato K, Shoeib M, Vieira VM, and McClean MD. 2012. “Polyfluorinated Compounds in Serum Linked to Indoor Air in Office Environments.” Environmental Science & Technology 46 (2):1209–15. doi: 10.1021/es2038257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frömel T, and Knepper TP. 2010. “Biodegradation of Fluorinated Alkyl Substances” In Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology Volume 208: Perfluorinated Alkylated Substances, edited by Pim De Voogt, 161–77. New York, NY: Springer New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme H, Tittlemier SA, Volkel W, Wilhelm M, and Twardella D. 2009. “Perfluorinated Compounds--Exposure Assessment for the General Population in Western Countries.” International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 212 (3):239–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallen C, Eaglesham G, Drage D, Nguyen TH, and Mueller JF. 2018. “A Mass Estimate of Perfluoroalkyl Substance (PFAS) Release from Australian Wastewater Treatment Plants.” Chemosphere 208:975–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo V, Leonardi G, Genser B, Lopez-Espinosa MJ, Frisbee SJ, Karlsson L, Ducatman AM, and Fletcher T. 2012. “Serum Perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) Concentrations and Liver Function Biomarkers in a Population with Elevated Pfoa Exposure.” Environmental Health Perspectives 120 (5):655–60. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1104436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbink WA, Berger U, and Cousins IT. 2015. “Estimating Human Exposure to Pfos Isomers and Pfca Homologues: The Relative Importance of Direct and Indirect (Precursor) Exposure.” Environment International 74:160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleason JA, Post GB, and Fagliano JA. 2015. “Associations of Perfluorinated Chemical Serum Concentrations and Biomarkers of Liver Function and Uric Acid in the Us Population (NHANES), 2007–2010.” Environmental Research 136:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glynn A, Berger U, Bignert A, Ullah S, Aune M, Lignell S, and Darnerud PO. 2012. “Perfluorinated Alkyl Acids in Blood Serum from Primiparous Women in Sweden: Serial Sampling During Pregnancy and Nursing, and Temporal Trends 1996–2010.” Environmental Science & Technology 46 (16):9071–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guelfo JL, and Adamson DT. 2018. “Evaluation of a National Data Set for Insights into Sources, Composition, and Concentrations of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in U.S. Drinking Water.” Environmental Pollution (Barking, Essex: 1987) 236:505–13. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.01.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen DF, Belisle J, Johnson JD, and Venkateswarlu P. 1981. “Characterization of Fluorinated Metabolites by a Gas Chromatographic-Helium Microwave Plasma Detector- -the Biotransformation of 1 h, 1 h, 2h, 2h-Perfluorodecanol to Perfluorooctanoate.” Analytical Biochemistry 118 (2):336–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halldorsson TI, Rytter D, Haug LS, Bech BH, Danielsen I, Becher G, Henriksen TB, and Olsen SF. 2012. “Prenatal Exposure to Perfluorooctanoate and Risk of Overweight at 20 Years of Age: A Prospective Cohort Study.” Environmental Health Perspectives 120 (5):668–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamid H, Li LY, and Grace JR. 2018. “Review of the Fate and Transformation of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Landfills.” Environmental Pollution 235:74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrad S, de Wit CA, Abdallah MA-E, Bergh C, Björklund JA, Covaci A, Darnerud PO, de Boer J, Diamond M, Huber S, Leonards P, Mandalakis M, Ostman C, Haug LS, Thomsen C, and Webster TF. 2010. “Indoor Contamination with Hexabromocyclododecanes, Polybrominated Diphenyl Ethers, and Perfluoroalkyl Compounds: An Important Exposure Pathway for People?” Environmental Science & Technology 44 (9):3221–31. doi: 10.1021/es903476t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman TJ, Calafat AM, Holmes AK, Marcus M, Northstone K, Flanders WD, Kato K, and Taylor EV. 2017. “Prenatal Exposure to Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Body Fatness in Girls.” Childhood Obesity 13 (3):222–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haug LS, Huber S, Becher G, and Thomsen C. 2011. “Characterisation of Human Exposure Pathways to Perfluorinated Compounds — Comparing Exposure Estimates with Biomarkers of Exposure.” Environment International 37 (4):687–93. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Deng L, Zhang Q, Guo J, Zhou J, Song W, and Yuan F. 2017. “Diagnostic Value of Ck-18, Fgf-21, and Related Biomarker Panel in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Biomed Research International 2017:9729107. doi: 10.1155/2017/9729107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He XW, Liu YX, Xu B, Gu LB, and Tang W. 2018. “Pfoa Is Associated with Diabetes and Metabolic Alteration in Us Men: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003– 2012.” Science of the Total Environment 625:566–74. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.12.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heindel JJ, Skalla LA, Joubert BR, Dilworth CH, and Gray KA. 2017. “Review of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease Publications in Environmental Epidemiology.” Reproductive Toxicology 68:34–48. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2016.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson WM, and Smith MA. 2007. “Perfluorooctanoic Acid and Perfluorononanoic Acid in Fetal and Neonatal Mice Following in Utero Exposure to 8-2 Fluorotelomer Alcohol.” Toxicological Sciences 95 (2):452–61. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzke D, Olsson E, and Posner S. 2012. “Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in Consumer Products in Norway - a Pilot Study.” Chemosphere 88 (8):980–7. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K, Webster TF, Bartell SM, Weisskopf MG, Fletcher T, and Vieira VM. 2011. “Private Drinking Water Wells as a Source of Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA) in Communities Surrounding a Fluoropolymer Production Facility.” Environmental Health Perspectives 119 (1):92–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hölzer J, Midasch O, Rauchfuss K, Kraft M, Reupert R, Angerer J, Kleeschulte P, Marschall N, and Wilhelm M. 2008. “Biomonitoring of Perfluorinated Compounds in Children and Adults Exposed to Perfluorooctanoate-Contaminated Drinking Water.” Environmental Health Perspectives 116 (5):651–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde M, De Silva AO, Muir DCG, and Letcher RJ. 2011. “Monitoring of Perfluorinated Compounds in Aquatic Biota: An Updated Review Pfcs in Aquatic Biota.” Environmental Science & Technology 45 (19):7962–73. doi: 10.1021/es104326w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtz EF, Higgins CP, Field JA, and Sedlak DL. 2013. “Persistence of Perfluoroalkyl Acid Precursors in Afff-Impacted Groundwater and Soil.” Environmental Science & Technology 47 (15):8187–95. doi: 10.1021/es4018877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houtz EF, Sutton R, Park J-S, and Sedlak M. 2016. “Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances in Wastewater: Significance of Unknown Precursors, Manufacturing Shifts, and Likely Afff Impacts.” Water Research 95:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard PH, and Muir DC. 2010. “Identifying New Persistent and Bioaccumulative Organics among Chemicals in Commerce.” Environmental Science & Technology 44 (7):2277–85. doi: 10.1021/es903383a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høyer BB, Ramlau-Hansen CH, Vrijheid M, Valvi D, Pedersen HS, Zviezdai V, Jönsson BAG, Lindh CH, Bonde JP, and Toft G. 2015. “Anthropometry in 5-to 9-Year-Old Greenlandic and Ukrainian Children in Relation to Prenatal Exposure to Perfluorinated Alkyl Substances.” Environmental Health Perspectives 123 (8):841–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu XC, Andrews DQ, Lindstrom AB, Bruton TA, Schaider LA, Grandjean P, Lohmann R, Carignan CC, Blum A, Balan SA, Higgins CP, and Sunderland EM. 2016. “Detection of Poly- and Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFASs) in U.S. Drinking Water Linked to Industrial Sites, Military Fire Training Areas, and Wastewater Treatment Plants.” Environmental Science & Technology Letters 3 (10):344–50. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley S, Houtz E, Goldberg D, Wang ΜM, Park JS, Nelson DO, Reynolds P, Bernstein L, Anton-Culver H, Horn-Ross P, and Petreas M. 2016. “Preliminary Associations between the Detection of Perfluoroalkyl Acids (PFAAs) in Drinking Water and Serum Concentrations in a Sample of California Women.” Environmental Science & Technology Letters 3 (7):264–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.estlett.6b00154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Okada F, Ito R, Kato S, Sasaki S, Nakajima S, Uno A, Saijo Y, Sata F, Yoshimura Y, Kishi R, Nakazawa H. 2004. “Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Related Perfluorinated Compounds in Human Maternal and Cord Blood Samples: Assessment of Pfos Exposure in a Susceptible Population During Pregnancy.” Environmental Health Perspectives 112 (11): 1204–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaacks LM, Barr DB, Sundaram R, Grewal J, Zhang C, and Louis GMB. 2016. “Pre-Pregnancy Maternal Exposure to Persistent Organic Pollutants and Gestational Weight Gain: A Prospective Cohort Study.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13 (9):905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RB 2018a. “Time Trends over 2003–2014 in the Concentrations of Selected Perfluoroalkyl Substances among Us Adults Aged ≥20 Years: Interpretational Issues.” Science of the Total Environment 645:946–57. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.07.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RB, and Ducatman A. 2019. “Roles of Gender and Obesity in Defining Correlations between Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Lipid/Lipoproteins.” Science of the Total Environment 653:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RB 2018b. “Contribution of Diet and Other Factors to the Observed Levels of Selected Perfluoroalkyl Acids in Serum among Us Children Aged 3–11 Years.” Environmental Research 161:268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen RC, Glintborg D, Timmermann CAG, Nielsen F, Kyhl HB, Andersen HR, Grandjean P, Jensen TK, and Andersen M. 2018. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Glycemic Status in Pregnant Danish Women: The Odense Child Cohort.” Environment International 116:101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin R, McConnell R, Catherine C, Xu S, Walker DI, Stratakis N, Jones DP, Miller GW, Peng C, Conti DV, Vos MB, and Chatzi L. 2020. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Severity of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver in Children: An Untargeted Metabolomics Approach.” Environment International 134:105220. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Choi K, Lee HS, Kim DH, Park NY, Kim S, and Kho Y. 2016. “Elevated Levels of Short Carbon-Chain Pfcas in Breast Milk among Korean Women: Current Status and Potential Challenges.” Environmental Research 148:351–9. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen M, Grandjean P, Weihe P, Steuerwald U, Oulhote Y, and Valvi D. 2017. “Early-Life Exposures to Persistent Organic Pollutants in Relation to Overweight in Preschool Children.” Reproductive Toxicology 68:145–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnes C, Winquist A, and Steenland K. 2014. “Incidence of Type Ii Diabetes in a Cohort with Substantial Exposure to Perfluorooctanoic Acid.” Environmental Research 128:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsa DR 1995. “Fluorinated Surfactants: Synthesis Properties Applications, by Kissa Erik. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, 1994, Pp. Vii + 469, Price Us$165.00. Isbn 0–8247-9011–1” Polymer International 36 (1):101-. doi: 10.1002/pi.1995.210360113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil N, Ebert JR, Honda M, Lee M, Nahhas RW, Koskela A, Hangartner T, and Kannan K. 2018. “Perfluoroalkyl Substances, Bone Density, and Cardio-Metabolic Risk Factors in Obese 8–12 Year Old Children: A Pilot Study.” Environmental Research 160:314–21. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khansari MR, Yousefsani BS, Kobarfard F, Faizi M, and Pourahmad J. 2017. “In Vitro Toxicity of Perfluorooctane Sulfonate on Rat Liver Hepatocytes: Probability of Distructive Binding to Cyp 2E1 and Involvement of Cellular Proteolysis.” Environmental Science and Pollution Research International 24 (29):23382–8. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9908-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Park HY, Jeon JD, Kho Y, Kim SK, Park MS, and Hong YC. 2016. “The Modifying Effect of Vitamin C on the Association between Perfluorinated Compounds and Insulin Resistance in the Korean Elderly: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial.” European Journal of Nutrition 55 (3):1011–20. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0915-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Moon S, Oh BC, Jung D, Ji K, Choi K, and Park YJ. 2018. “Association between Perfluoroalkyl Substances Exposure and Thyroid Function in Adults: A Meta Analysis.” PloS One 13 (5):e0197244. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]