Abstract

Background

Many important clinical features of bronchiectasis have been reported. However, the factors were evaluated using a specific disease cohort. Thus, clinical factors associated with bronchiectasis have not been well assessed in comparison to the general population. The aim of this study was to evaluate the factors associated with bronchiectasis using a national representative database.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2009. To evaluate factors associated with bronchiectasis, a multivariable logistic analysis was used with adjustment for demographic and socioeconomic factors.

Results

In the present study, the prevalence of bronchiectasis was 0.4%. Compared with subjects without bronchiectasis, subjects with bronchiectasis were older (55.1 vs. 44.4 years, P<0.001) and had lower body mass index (BMI) (23.2 vs. 24.2 kg/m2, P<0.001). The proportions of low family income (70.5% vs. 40.2%, P<0.001) and low educational level (less than high school) (85.3% vs. 70.6%, P=0.041) were higher in subjects with bronchiectasis than in subjects without bronchiectasis. Regarding comorbidities, subjects with bronchiectasis were more likely to have asthma (17.8% vs. 2.9%, P<0.001), previous history of pulmonary tuberculosis (TB) (43.5% vs. 5.0%, P<0.001), osteoporosis (19.1% vs. 7.8%, P=0.002), and depression (9.3% vs. 3.0%, P=0.015) compared with subjects without bronchiectasis. In addition, subjects with bronchiectasis had more respiratory symptoms and poorer quality of life measured using the EuroQoL five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) index (0.87 vs. 0.93, P<0.001) than subjects without bronchiectasis. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, low family income (adjusted odds ratio, OR =3.83, 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.46–10.03), asthma (adjusted OR =3.73, 95% CI: 1.29–10.79), pulmonary TB (adjusted OR =7.88, 95% CI: 2.65–23.39), and the presence of airflow limitation (adjusted OR =2.98, 95% CI: 1.01–8.98) were independently associated with bronchiectasis.

Conclusions

Subjects with bronchiectasis suffered from more respiratory symptoms with limited physical activity and poorer quality of life than the general population. Factors independently associated with bronchiectasis were lower family income and comorbid pulmonary conditions, such as previous pulmonary TB, asthma, and airflow limitation.

Keywords: Epidemiologic factors, bronchiectasis, National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey

Introduction

Non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis (hereafter bronchiectasis) is a chronic structural respiratory disease characterized by permanent dilatation of bronchi and chronic respiratory symptoms such as cough, sputum, and dyspnea (1). Although bronchiectasis has been regarded as a neglected lung disease, the prevalence of bronchiectasis is increasing worldwide, and the burden of the disease is significant (2,3).

Fortunately, with a recent interest in this disease, many important clinical characteristics, comorbidity profiles, and socioeconomic factors of bronchiectasis have been elucidated. In several bronchiectasis cohort studies, patients with bronchiectasis were mainly elderly and females were more predominant than males (4-6). Previous pulmonary infectious conditions, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis (TB), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and asthma, are well established pulmonary comorbidities of bronchiectasis (7-12). Extra-pulmonary comorbidities of bronchiectasis include many conditions such as connective tissue disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and immunodeficiency (9,13,14). In addition, low socioeconomic status and low family income were associated with bronchiectasis in subjects 40 years of age or older (12).

In most previous studies, the clinical factors associated with bronchiectasis were evaluated in a specific disease cohort (e.g., asthma, COPD, and inflammatory bowel disease cohort) (15-17), or factors associated with poor outcomes were evaluated in bronchiectasis cohorts (18,19). Furthermore, factors associated with bronchiectasis have not been assessed in the general population. Accordingly, the associated factors for bronchiectasis have not been clarified after adjusting for various clinical and socioeconomic factors. This information could be helpful to provide doctors with clinical clues that can help diagnose bronchiectasis early and manage patients suffering from chronic respiratory symptoms properly.

Therefore, in the present study, we aimed to evaluate the factors associated with bronchiectasis subjects compared with the general population without bronchiectasis using national representative data in Korea. We present the following article in accordance with the STROBE reporting checklist (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4873).

Methods

Participants

Data from the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2009, a nationally representative survey collected by the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare (n=22,340), were used in this cross-sectional study. Participants with missing weighted variable information were excluded (n=2,489), and 19,851 subjects were included in this study. The participants were classified into two groups based on the presence of physician-diagnosed bronchiectasis: subjects with bronchiectasis (n=78) and subjects without bronchiectasis (n=19,773). The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chungbuk National University (application No. 2020-03-005). Informed consent was not required because this study was based on the NHANES database, which includes fully anonymized and de-identified data.

Measurements

Data on age; sex; body mass index (BMI); smoking history; physical activity; occupation; EuroQoL five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) index values, which range between 0 (worst imaginable health state) and 1 (best imaginable health state) (20); and spirometric results were obtained from the Korea NHANES database (21). Absolute values of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and forced vital capacity (FVC) were obtained, and the percentage of predicted values (% predicted) for FEV1 and FVC was calculated using the reference equation obtained from analysis of a representative Korean sample (22). Airflow limitation was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7 (23). Spirometry was performed in subjects 20 years of age or older. Type of occupation was categorized into four groups according to the 6th Korean Standard Classification of Occupation: manager, professional, office worker or service worker; agriculture or fishery worker; skilled labor or machine operator; and manual laborer (24). Comorbidities were based on questionnaires regarding previous physician diagnosis, which included asthma, pulmonary TB, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis, and depression (25).

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcome was factors associated with bronchiectasis using a representative nationwide database in Korea. The secondary outcome was symptomatic burden of subjects with bronchiectasis. Respiratory symptoms, physical activity limitations due to respiratory diseases, and quality of life measured using the EQ-5D index were compared between subjects with and without bronchiectasis.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using NHANES weights and survey (svy) commands in STATA (release 13.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to account for the complex multistage probability sampling design. The prevalence and 95% confidence interval (CI) for each variable were calculated for both groups. Intergroup comparisons of continuous variables and categorical variables between the two groups were performed using t-test and chi-squared test, respectively. To evaluate factors associated with bronchiectasis, both univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed. Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and factors with P values <0.2 in univariable analysis. Model 2 was additionally adjusted for presence of airflow limitation. Subjects with missing values in the pulmonary function test were not included in Model 2. Two-tailed analyses were conducted, and P values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

In the present study, the prevalence of bronchiectasis was 0.4%. As shown in Table 1, subjects with bronchiectasis were older and had lower BMI than subjects without bronchiectasis. The proportions of low family income and low educational level (less than high school) were higher in subjects with bronchiectasis than in those without bronchiectasis. Significant difference was not observed in type of occupation between the two groups. Regarding comorbidities, subjects with bronchiectasis were more likely to have asthma, previous history of pulmonary TB, osteoporosis, and depression compared with those without bronchiectasis.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

| Characteristics | Subjects without bronchiectasis (n=19,773) | Subjects with bronchiectasis (n=78) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 44.4 (43.8–44.9) | 55.1 (51.4–58.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male | 49.5 (48.2–50.9) | 50.5 (49.1–51.8) | 0.884 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.2 (24.1–24.3) | 23.2 (22.4–23.9) | <0.001 |

| Smoking history | 0.483 | ||

| Never-smoker | 54.3 (53.0–55.7) | 48.5 (32.7–64.5) | |

| Current- or ex-smoker | 45.7 (44.3–47.0) | 51.5 (35.5–67.3) | |

| Family income | <0.001 | ||

| Low | 40.2 (38.3–42.3) | 70.5 (55.4–82.1) | |

| High | 59.7 (57.7–61.7) | 29.5 (17.9–44.6) | |

| Educational level | 0.041 | ||

| High school or less | 70.6 (68.9–72.2) | 85.3 (70.6–93.3) | |

| College or above | 29.4 (27.7–31.1) | 14.7 (6.7–29.3) | |

| Type of occupation | 0.079 | ||

| Manager/professional/office worker/service worker | 59.2 (57.1–61.4) | 46.3 (24.3–69.9) | |

| Agriculture/fishery worker | 8.8 (7.2–10.6) | 23.3 (10.7–43.4) | |

| Skilled labor/machine operation | 18.8 (17.3–20.4) | 11.1 (3.2–31.9) | |

| Manual laborer | 13.2 (11.9–14.5) | 19.3 (7.4–41.8) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Pulmonary comorbidity | |||

| Asthma | 2.9 (2.5–3.3) | 17.8 (9.5–30.9) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary TB | 5.0 (4.5–5.6) | 43.5 (28.7–59.6) | <0.001 |

| Extra-pulmonary comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8.7 (8.0–9.5) | 9.1 (3.6–12.1) | 0.921 |

| Hypertension | 26.9 (25.6–28.4) | 26.7 (14.9–43.1) | 0.968 |

| Dyslipidemia | 39.5 (38.1–40.9) | 44.3 (28.8–61.0) | 0.563 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 2.6 (2.2–2.9) | 4.3 (1.1–1.6) | 0.451 |

| Osteoporosis | 7.8 (7.1–8.7) | 19.1 (10.3–32.7) | 0.002 |

| Osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis | 10.8 (10.1–11.6) | 26.4 (15.2–42.0) | 0.061 |

| Depression | 3.0 (2.5–3.4) | 9.3 (3.6–22.2) | 0.015 |

| Spirometry | |||

| FVC, L | 3.75 (3.72–3.78) | 3.36 (3.11–3.61) | 0.009 |

| FVC, % predicted | 92.8 (92.4–93.2) | 87.6 (83.6–91.6) | 0.001 |

| FEV1, L | 3.02 (2.99–3.05) | 2.47 (2.27–2.73) | <0.001 |

| FEV1, % predicted | 91.9 (91.5–92.3) | 81.9 (75.8–88.1) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio | 0.81 (0.80–0.81) | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) | <0.001 |

| Spirometric pattern* | <0.001 | ||

| Normal | 80.9 (79.7–82.0) | 50.0 (34.3–65.7) | |

| Restrictive | 11.1 (10.1–12.1) | 15.1 (6.5–31.3) | |

| Obstructive | 8.0 (7.4–8.7) | 34.9 (22.2–50.1) |

Data are presented as weighted mean (95% confidence interval) or weighted percentage (95% CI). *, spirometric pattern was classified as follows: normal spirometry was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ≥0.70 and FVC ≥80% predicted, the restrictive spirometric pattern was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ≥0.7 and FVC <80% predicted, the obstructive spirometric pattern was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7. BMI, body mass index; TB, tuberculosis; FVC, forced vital capacity; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; CI, confidence interval.

Respiratory symptoms and quality of life

As shown in Table S1, subjects with bronchiectasis had more respiratory symptoms including cough, sputum, dyspnea, and limitation in physical activity due to respiratory diseases than did those without bronchiectasis.

Quality of life estimated using the EQ-5D index was lower in subjects with bronchiectasis than subjects without bronchiectasis (0.87 vs. 0.93, P<0.001). Among the components of EQ-5D index, subjects with bronchiectasis had more difficulty in mobility, usual activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression than subjects without bronchiectasis.

Factors associated with bronchiectasis

In univariable analysis, age (unadjusted odds ratio, OR =1.04, 95% CI: 1.02–1.05), BMI (unadjusted OR =0.90, 95% CI: 0.83–0.98), low family income (unadjusted OR =3.54, 95% CI: 1.85–6.78), low educational level (unadjusted OR =2.42, 95% CI: 1.01–5.79), asthma (unadjusted OR =4.07, 95% CI: 1.46–11.37), pulmonary TB (unadjusted OR =8.93, 95% CI: 3.30–24.17), and airflow limitation (unadjusted OR =6.13, 95% CI: 3.24–11.59) were significant factors associated with bronchiectasis (Table 2).

Table 2. Factors associated with bronchiectasis using univariable and multivariable analysis.

| Variable | Univariable analysis (n=78) | Multivariable analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (n=78) | Model 2 (n=67) | |||||

| Unadjusted OR | P value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |||

| Age | 1.04 (1.02–1.05) | <0.001 | 1.03 (1.001–1.08) | 1.02 (0.99–1.07) | ||

| Male | 0.95 (0.48–1.88) | 0.884 | 0.53 (0.18–1.55) | 0.64 (0.18–2.20) | ||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.90 (0.83–0.98) | 0.018 | 3.09 (0.57–16.79) | 2.62 (0.47–14.65) | ||

| Family income | ||||||

| High | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Low | 3.54 (1.85–6.78) | <0.001 | 4.03 (1.45–11.19) | 3.83 (1.46–10.03) | ||

| Educational level | ||||||

| >High school | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| High school or less | 2.42 (1.01–5.79) | 0.048 | 1.13 (0.31–4.19) | 1.09 (0.42–2.86) | ||

| Type of occupation | ||||||

| Manager/professional/office worker/service worker | Ref | 0.074 | Ref | Ref | ||

| Agriculture/fishery worker | 3.40 (1.14–10.12) | 0.69 (0.10–4.66) | 0.58 (0.09–3.93) | |||

| Skilled labor/machine operation | 0.75 (0.17–3.30) | 0.50 (0.08–2.98) | 0.47 (0.07–2.85) | |||

| Manual laborer | 1.87 (0.52–6.69) | 0.72 (0.13–3.93) | 0.56 (0.11–2.79) | |||

| Pulmonary comorbidity | ||||||

| Asthma | 4.07 (1.46–11.37) | <0.001 | 5.75 (1.89–17.46) | 3.73 (1.29–10.79) | ||

| Pulmonary TB | 8.93 (3.30–24.17) | <0.001 | 8.95 (2.97–26.95) | 7.88 (2.65–23.39) | ||

| Pulmonary function | ||||||

| Without airflow limitation | Ref | <0.001 | – | Ref | ||

| With airflow limitation | 6.13 (3.24–11.59) | – | 2.98 (1.01–8.98) | |||

Data are presented as ratio (95% CI). Age, sex, BMI, family income, educational level, type of occupation, and pulmonary comorbidities (asthma and TB) were adjusted in Model 1. Variables in Model 1 and presence of airflow limitation were adjusted in Model 2. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; Ref, reference; BMI, body mass index; TB, tuberculosis.

In multivariable analysis when the pulmonary function test was not included (Model 1), age (adjusted OR =1.03, 95% CI: 1.00–1.08), low family income (adjusted OR =4.03, 95% CI: 1.45–11.19), asthma (adjusted OR =5.75, 95% CI: 1.89–17.46), and pulmonary TB (adjusted OR =8.95, 95% CI: 2.97–26.95) were significantly associated with bronchiectasis (Pseudo R2 =0.165). In Model 2, in which the presence of airflow limitation was further adjusted, low family income (adjusted OR =3.83, 95% CI: 1.46–10.03), asthma (adjusted OR =3.73, 95% CI: 1.29–10.79), pulmonary TB (adjusted OR =7.88, 95% CI: 2.65–23.39), and presence of airflow limitation (adjusted OR =2.98, 95% CI: 1.01–8.98) were significant factors associated with bronchiectasis (Pseudo R2 =0.174) (Table 2).

Prevalence of bronchiectasis in the context of pulmonary comorbidities

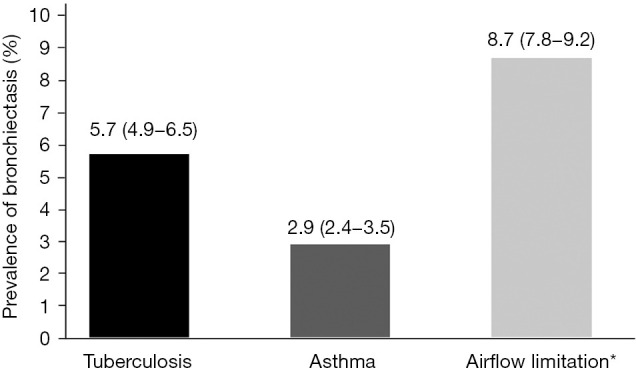

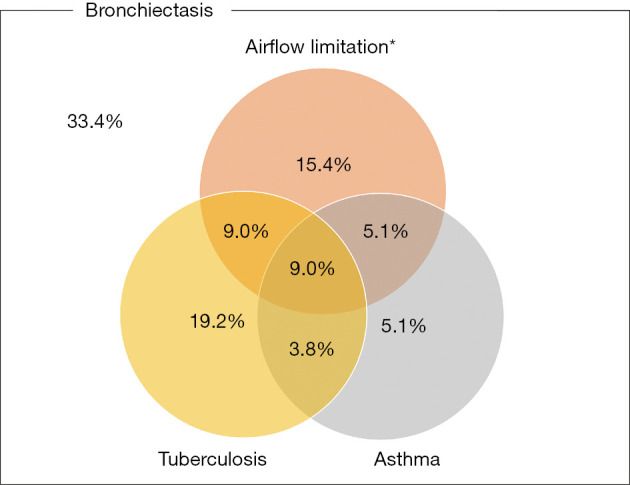

Figure 1 shows the prevalence of bronchiectasis in subjects with TB, asthma, and airflow limitation. Weighted percentage (95% CI) was 5.7% (4.9–6.5%) in subjects with TB, 2.9% (2.4–3.5%) in subjects with asthma, and 8.7% (7.8–9.2%) in subjects with airflow limitation. Figure 2 is a Venn diagram showing the proportions of TB, asthma, and airflow limitation in subjects with bronchiectasis. Among subjects with bronchiectasis (n=78), 9.0% had asthma, TB, and airflow limitation simultaneously.

Figure 1.

The prevalence of bronchiectasis in subjects with TB, asthma, and airflow limitation based on Korean NHANES 2007–2009 data. The prevalence is presented as weighted percentage (95% CI). *, airflow limitation was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7. TB, tuberculosis; NHANES, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram showing the rate of TB, asthma, and airflow limitation in subjects with bronchiectasis. *, airflow limitation was defined as pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7. TB, tuberculosis; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate factors associated with bronchiectasis using a nationally representative database. Factors associated with bronchiectasis included respiratory symptoms such as airflow limitation, pulmonary TB, a lower family income/educational level, and poorer quality of life, compared with subjects without bronchiectasis. Considering that bronchiectasis is still under-recognized, it is important to elucidate factors associated with bronchiectasis, which would help clinicians diagnose and manage bronchiectasis early in patients with chronic respiratory symptoms.

The most notable finding of this study was the factors associated with bronchiectasis. The factors comprised comorbid pulmonary conditions such as previous pulmonary TB, asthma, and presence of airflow limitation and low family income. Most previous studies focused on the clinical characteristics of bronchiectasis accompanying other diseases, including COPD or asthma (6,8,26,27). Older age, lower BMI, more severe respiratory symptoms, and more frequent exacerbations were observed in COPD or asthma patients with bronchiectasis compared to those without bronchiectasis (7,15,27). In addition, in terms of pulmonary function tests, COPD patients with bronchiectasis showed more severe airflow limitation than subjects without bronchiectasis (8,27). In contrast, the clinical features, comorbidities, pulmonary function, and quality of life associated with bronchiectasis in the general population were evaluated in the present study. In addition, socioeconomic factors were incorporated with clinical features of subjects with bronchiectasis, which provides clinicians a more complete picture of subjects with bronchiectasis.

In the present study, pulmonary comorbidities of asthma, previous pulmonary TB, and airflow limitation were independently associated with presence of bronchiectasis. In agreement with our findings, asthma and COPD were common etiologies and comorbidities in individuals with bronchiectasis in previous studies (5,6,18). In a recent cohort study performed in Finland, asthma was associated with 68% of the study population and was an estimated cause of bronchiectasis in one-fourth of the study population (6). In addition to the previous report, asthma was significantly associated with bronchiectasis in the present study. Furthermore, the rate of post-infectious bronchiectasis was reportedly 15–50% (28-30), and previous TB was the most well-known etiology of bronchiectasis among various factors (31). In agreement with the previous study, previous pulmonary TB was associated with bronchiectasis even after adjustment for various socioeconomic factors in the present study.

In this study, subjects with bronchiectasis showed more respiratory symptoms, physical activity limitations, and poorer quality of life. Patients with bronchiectasis are known to suffer from more respiratory symptoms, including purulent sputum and recurrent respiratory infections (13,32-35). In addition to respiratory symptoms, physical activity limitation and poorer quality of life were observed more frequently in subjects with bronchiectasis than in subjects without bronchiectasis. Hypothetically, quality of life impairment and physical activity limitations may be more negatively affected by additional respiratory symptoms in subjects with bronchiectasis. However, among the EQ-5D index components, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were especially present in subjects with bronchiectasis in the present study. These results indicate that poorer quality of life may not be solely explained by more respiratory symptoms in subjects with bronchiectasis. Future studies are warranted to determine the underlying mechanisms of the phenomenon, which may help clinicians discover measures to improve the quality of life in subjects with bronchiectasis.

Bronchiectasis is often underreported or underdiagnosed (36) although it is associated with a significantly increased health burden worldwide, an annual exacerbation frequency of up to 3 per patient per year, and a clear attributable mortality (37). From this point of view, revealing factors associated with bronchiectasis would be very helpful in reducing the bronchiectasis-related health burden through early diagnosis and management of this disease. Our study showed that asthma and the presence of airflow limitation are associated with bronchiectasis. As comorbid bronchiectasis results in a poorer disease control and more frequent exacerbation in patients with COPD or asthma (7,38), our results strongly suggest that clinicians should suspect the presence of bronchiectasis when they encounter patients with poorly controlled airway diseases. Consistent with a previous report (39), this study also emphasizes that bronchiectasis is significantly associated with a previous history of pulmonary TB. Thus, bronchiectasis should be considered as a differential diagnosis when patients have persistent respiratory symptoms even after completion of TB treatment.

Another interesting finding is that subjects with bronchiectasis showed a lower family income and lower educational level. Due to the cross-sectional design, we could not fully explain the causal relationship between bronchiectasis and socioeconomic status. One possible explanation is that a low socioeconomic status could contribute to the development of bronchiectasis. Many studies have shown that a lower socioeconomic family is associated with respiratory infection, including TB, which is a well-known risk factor for bronchiectasis (1,40). In contrast, bronchiectasis could contribute to a low socioeconomic status in these patients. Patients with bronchiectasis could be at risk of disability and low work productivity (work loss, reduced work hours, absenteeism, and early retirement) due to substantial symptomatic burden, as shown in studies evaluating disability and job status in subjects with COPD (24). An increased medical burden in subjects with bronchiectasis could also contribute to their low socioeconomic status. Thus, long-term and large-scale prospective cohort studies are warranted to elucidate the causal inference of this phenomenon in the future.

The present study results have several important clinical implications. First, individuals with bronchiectasis experience more respiratory symptoms and poorer quality of life than subjects without bronchiectasis. Accordingly, this indicates that early diagnosis and adequate treatment are critical in individuals with bronchiectasis. Second, asthma and airflow limitations were the main factors associated with presence of bronchiectasis. Therefore, it is important for clinicians to determine whether bronchiectasis is co-existent in subjects with uncontrolled or airway diseases with airflow limitation. Third, pulmonary TB was a significant factor associated with bronchiectasis. From this perspective and considering the high prevalence of TB in many Asian countries, clinicians should carefully assess the development of bronchiectasis after TB treatment.

The present study had several limitations. First, due to the nature of the cross-sectional study design, evaluating a cause-and-effect relationship between bronchiectasis and associated factors was not possible. Second, because this study was conducted in the Korean population, the results might not be generalized to other races or ethnic groups. Third, bronchiectasis was diagnosed based on physician diagnosis. Therefore, more symptomatic subjects may have been included in the study, and subjects with minor symptoms may not have been included. Fourth, compared with the control group, the number of bronchiectasis subjects was relatively small, which may have led to some important factors lacking statistical significance.

In conclusion, subjects with bronchiectasis were more likely to be older, have lower BMI, lower family income, lower educational level, more pulmonary comorbidities, and decreased lung function compared with those without bronchiectasis. Subjects with bronchiectasis suffer from more respiratory symptoms with physical activity limitation and decreased quality of life than those without bronchiectasis. Furthermore, lower family income and pulmonary comorbidities of previous pulmonary TB, asthma, and presence of airflow limitation were independently associated with bronchiectasis. Appropriate management to reduce disease burden associated with respiratory symptoms, poor quality of life, and comorbid pulmonary conditions is needed in subjects with bronchiectasis.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, Information and Communications Technologies (NRF-2020R1F1A1070468 to HL & NRF-2019R1G1A1008692 to HC). The funder had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work and ensure that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013). This study was approved by the institutional review board of Chungbuk National University (application No. 2020-03-005). Informed consent was not required because this study was based on the NHANES database, which includes fully anonymized and de-identified data.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the STROBE reporting checklist. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4873

Peer Review File: Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4873

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/atm-20-4873). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Chalmers JD, Chang AB, Chotirmall SH, et al. Bronchiectasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4:45. 10.1038/s41572-018-0042-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choi H, Yang B, Nam H, et al. Population-based prevalence of bronchiectasis and associated comorbidities in South Korea. Eur Respir J 2019;54:1900194. 10.1183/13993003.00194-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringshausen FC, de Roux A, Pletz MW, et al. Bronchiectasis-associated hospitalizations in Germany, 2005-2011: a population-based study of disease burden and trends. PLoS One 2013;8:e71109. 10.1371/journal.pone.0071109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Visser SK, Bye PTP, Fox GJ, et al. Australian adults with bronchiectasis: The first report from the Australian Bronchiectasis Registry. Respir Med 2019;155:97-103. 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aksamit TR, O'Donnell AE, Barker A, et al. Adult Patients With Bronchiectasis: A First Look at the US Bronchiectasis Research Registry. Chest 2017;151:982-92. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mäntylä J, Mazur W, Törölä T, et al. Asthma as aetiology of bronchiectasis in Finland. Respir Med 2019;152:105-11. 10.1016/j.rmed.2019.04.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-García MÁ, Soler-Cataluna JJ, Donat Sanz Y, et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in patients with COPD. Chest 2011;140:1130-7. 10.1378/chest.10-1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin J, Yu W, Li S, et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in patients with moderate-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e4219. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guan WJ, Gao YH, Xu G, et al. Sputum bacteriology in steady-state bronchiectasis in Guangzhou, China. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2015;19:610-9. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi Q, Wang W, Li T, et al. Aetiology and clinical characteristics of patients with bronchiectasis in a Chinese Han population: A prospective study. Respirology 2015;20:917-24. 10.1111/resp.12574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie C, Wen Y, Zhao Y, et al. Clinical Features of Patients with Bronchiectasis with Comorbid Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in China. Med Sci Monit 2019;25:6805-11. 10.12659/MSM.917034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang B, Choi H, Lim JH, et al. The disease burden of bronchiectasis in comparison with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a national database study in Korea. Ann Transl Med 2019;7:770. 10.21037/atm.2019.11.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang HY, Chung FT, Lo CY, et al. Etiology and characteristics of patients with bronchiectasis in Taiwan: a cohort study from 2002 to 2016. BMC Pulm Med 2020;20:45. 10.1186/s12890-020-1080-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quint JK, Millett ER, Joshi M, et al. Changes in the incidence, prevalence and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016;47:186-93. 10.1183/13993003.01033-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padilla-Galo A, Olveira C, Fernández de Rota-Garcia L, et al. Factors associated with bronchiectasis in patients with uncontrolled asthma; the NOPES score: a study in 398 patients. Respir Res 2018;19:43. 10.1186/s12931-018-0746-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agusti A, Calverley PM, Celli B, et al. Characterisation of COPD heterogeneity in the ECLIPSE cohort. Respir Res 2010;11:122. 10.1186/1465-9921-11-122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stockley RA. Commentary: bronchiectasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Thorax 1998;53:526-7. 10.1136/thx.53.6.526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lonni S, Chalmers JD, Goeminne PC, et al. Etiology of Non-Cystic Fibrosis Bronchiectasis in Adults and Its Correlation to Disease Severity. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:1764-70. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-472OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olveira C, Padilla A, Martínez-García M, et al. Etiology of Bronchiectasis in a Cohort of 2047 Patients. An Analysis of the Spanish Historical Bronchiectasis Registry. Arch Bronconeumol 2017;53:366-74. 10.1016/j.arbr.2017.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Balestroni G, Bertolotti G. EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D): an instrument for measuring quality of life. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 2012;78:155-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005;26:319-38. 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi JK, Paek D, Lee JO, et al. Normal predictive values of spirometry in Korean population. Tuberc Respir Dis 2005;58:230-42. 10.4046/trd.2005.58.3.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lange P, Celli B, Agustí A, et al. Lung-Function Trajectories Leading to Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. N Engl J Med 2015;373:111-22. 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shin SH, Park J, Cho J, et al. Severity of airflow obstruction and work loss in a nationwide population of working age. Sci Rep 2018;8:9674. 10.1038/s41598-018-27999-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee H, Shin SH, Gu S, et al. Racial differences in comorbidity profile among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Med 2018;16:178. 10.1186/s12916-018-1159-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martínez-García MA, de la Rosa Carrillo D, Soler-Cataluña JJ, et al. Prognostic value of bronchiectasis in patients with moderate-to-severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013;187:823-31. 10.1164/rccm.201208-1518OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gatheral T, Kumar N, Sansom B, et al. COPD-related bronchiectasis; independent impact on disease course and outcomes. Copd 2014;11:605-14. 10.3109/15412555.2014.922174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimakou K, Triantafillidou C, Toumbis M, et al. Non CF-bronchiectasis: Aetiologic approach, clinical, radiological, microbiological and functional profile in 277 patients. Respir Med 2016;116:1-7. 10.1016/j.rmed.2016.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shoemark A, Ozerovitch L, Wilson R. Aetiology in adult patients with bronchiectasis. Respir Med 2007;101:1163-70. 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao YH, Guan WJ, Liu SX, et al. Aetiology of bronchiectasis in adults: A systematic literature review. Respirology 2016;21:1376-83. 10.1111/resp.12832 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhar R, Singh S, Talwar D, et al. Bronchiectasis in India: results from the European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) and Respiratory Research Network of India Registry. Lancet Glob Health 2019;7:e1269-e1279. 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30327-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magis-Escurra C, Reijers MH. Bronchiectasis. BMJ Clin Evid 2015;2015:1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franks LJ, Walsh JR, Hall K, et al. Measuring airway clearance outcomes in bronchiectasis: a review. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190161. 10.1183/16000617.0161-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Contarini M, Finch S, Chalmers JD. Bronchiectasis: a case-based approach to investigation and management. Eur Respir Rev 2018;27:180016. 10.1183/16000617.0016-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menéndez R, Mendez R, Polverino E, et al. Factors associated with hospitalization in bronchiectasis exacerbations: a one-year follow-up study. Respir Res 2017;18:176. 10.1186/s12931-017-0659-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aliberti S, Chalmers JD. Get together to increase awareness in bronchiectasis: a report of the 2nd World Bronchiectasis Conference. Multidisciplinary Respiratory Medicine 2018;13:28. 10.1186/s40248-018-0138-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Loebinger MR, Wells AU, Hansell DM, et al. Mortality in bronchiectasis: a long-term study assessing the factors influencing survival. Eur Respir J 2009;34:843-9. 10.1183/09031936.00003709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coman I, Pola-Bibian B, Barranco P, et al. Bronchiectasis in severe asthma: Clinical features and outcomes. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2018;120:409-13. 10.1016/j.anai.2018.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi H, Ryu J, Kim Y, et al. Incidence of bronchiectasis concerning tuberculosis epidemiology and other ecological factors: A Korean National Cohort Study. ERJ Open Res 2020;6:00097-2020. 10.1183/23120541.00097-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alsan MM, Westerhaus M, Herce M, et al. Poverty, Global Health, and Infectious Disease: Lessons from Haiti and Rwanda. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2011;25:611-22, ix. 10.1016/j.idc.2011.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The article’s supplementary files as