Abstract

Emergency care is in its nascency in most of the world and emergency health systems are developing throughout Africa, including Ethiopia. Ethiopia is a LMIC African nation that has committed to strengthening emergency care systems. A historical perspective provides the background of Ethiopian emergency care with the development of an emergency care taskforce to the first residency program and subsequent development of the Emergency and Critical Care Directorate. The goals of the directorate are discussed as well as their role in the development of the national integrated emergency medicine curriculum. Concurrently the development of multiple residencies as well as a nursing emergency and critical care training increased the human resources for emergency medicine. Recently, the WHO and Ministry of Health-Ethiopia have been working together to roll out an integrated emergency care system development agenda throughout the country bolstered by the recent passing of a world health assembly resolution to strengthen emergency care co-led by Ethiopia. With all the successes of Ethiopia in increasing human resources there have been both triumphs and challenges. The development of human resources for emergency care systems in Ethiopia provides insights and lessons learned to other nations on a similar pathway of strengthening emergency care systems.

Keywords: Ethiopia, Human resources for health, Emergency medicine, Emergency care systems

African relevance

-

•

As emergency medicine is an emerging specialty there is a dearth of human resources.

-

•

Other specialties have had success in developing human capacity to address health needs in low- and middle-income countries.

-

•

Ethiopia has made great strides to develop a robust emergency care system within a short timeline.

Introduction

Emergency care is a field of practice that focuses on the identification, diagnosis, stabilization, and disposition of urgent and emergent medical and traumatic conditions [1]. It encompasses the out of hospital setting including initial steps in emergency care at the scene through arrival and treatment at the emergency unit to disposition of the patient [1]. All these parts require the development of systems and protocols, which was only recently developed in the United States and other high-income countries [2]. Low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) are now realizing the need to develop a robust emergency care system.

Health workforce is defined as “all people engaged in actions whose primary intent is to enhance health” [3] This includes not only clinical staff but all those who contribute to health including managers, support staff, ambulance drivers, etc. A key challenge in developing health systems is the human resources needed for a robust system. Human resources for health (HRH) constitute all those that provide the day-to-day preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care to patients as well as the needs to perform their functions [3]. According to the World Health Organization Strategy on Human Resources for Health 18 million more health workers are needed in LMICs by 2030 to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals [4]. According to the Road Map for Scaling up Human Resources for Health: For Improved Health Service Delivery in African Region 2012–2025 the pressing HRH challenges in Africa include: weak HRH leadership and governance capacity, weak training capacity, inadequate utilization, retention and performance of available health workforce, insufficient information and evidence based decision making, weak regulatory capacity, uncoordinated partnerships and weak policy dialogue [5].

Strategies have been developed to address these concerns [5] and some countries have taken strides in improving HRH. Maternal and child health has shown success in task shifting and training lay health workers [6]. Task shifting is the process by which tasks are moved to health workers with less training or fewer qualifications allowing for efficient use of existing human resources providing more adequate service delivery [7]. Midwifery health system strengthening in 21 countries has been shown by Lerberghe et al. [8] Rural retention strategies have been employed to combat the “brain drain” [9]. Improvement in availability, accessibility, adaptability and quality has been shown in countries throughout Africa, Asia and South America [[10], [11], 12.]. Task shifting to improve access to care has been shown in Nepal by expanding the scope of practice of general practitioners [13]. As many countries succumb to both man-made and natural hazards human resources are a crucial part of responding to hazards with some successful models shown in conflict [14] and outbreak situations [15]. A large Human Resources for Health multi-year program was developed in Rwanda that paired high income universities with Rwandan medical departments to develop human resources capacity resulting in successful increase in human resources [[16], [17], [18], [19]].

As emergency medicine is an emerging specialty there is a dearth of human resources. Other specialties have had success in developing human capacity to address health needs in LMIC's as shown above but emergency medicine is still in its infancy in most countries and hence great need to build human resource capacity.

Ethiopia is one of the fastest growing economies and populations within Sub-Saharan Africa. The burden of disease is shifting from communicable to noncommunicable diseases. For example, road traffic accidents account for more than 56 deaths per 10,000 vehicles and a major cause of disability within the population according to the Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH). With a growing population and the shifting burden of disease the need for a robust emergency care in Ethiopia has never been so needed.

A brief history of emergency care in Ethiopia

Emergency medicine is a relatively new field of medicine beginning in the 1960's within the United States and the United Kingdom. In Africa, specifically South Africa, emergency medicine became a recognized specialty in 2003 with the African Federation for Emergency Medicine being established in 2009. Emergency care is growing throughout Africa. A paper by Azazh, et al. [20] outlines the development of emergency care in Ethiopia; pre-Ethiopian millennium and post-Ethiopian millennium.1

During the pre-Ethiopian millennium (2007 in the Gregorian calendar) several milestones were reached; the most significant of which was the formation of the Emergency Medicine Task Force (EMTF) in 2006. The EMTF was tasked to develop an emergency medicine training program at Addis Ababa University School of Medicine (AAUSOM) and within the country. AAUSOM led emergency medicine training during this time while the FMOH agreed to expand emergency medical services. During the Ethiopian Millennium, secondary to the expected size of celebrations, the FMOH led the development of an emergency care system over a short period of time. The emergency systems included the development of a communication system, and standards for emergency units which included standardized drugs, equipment, supplies and training. Also, during this time, the Ministry of Health (MoH), supported medical faculty to develop the first emergency services unit (EMSU) at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital (TASH or Black Lion). Achievements after the Ethiopian Millennium consisted of the development in both out of hospital and health facility level emergency care as well as human resource development through formalized emergency medicine training programs.

Recently the Federal Ministry of Health has shown a renewed commitment to emergency care systems by the development of the Emergency and Critical Care Directorate (ECCD) sitting within the MoH. The Directorate is charged with the creation of a robust emergency care system within the country. The ECCD was established in 2015 with the following objectives and outcomes (Table 1) to be met by 2020.

Table 1.

Emergency and critical care directorate objectives and targets.

| Objective | Targets |

|---|---|

| Reduce the incidence and impact of trauma/injuries | Reduce road traffic accident related mortality from the baseline 62/10,000 by one third |

| Improve quality of pre-hospital care services | 1. Increase ambulances operating with the set basic standards from 3.2% to 35%. 2. Increase ambulance coverage to 100% from the current 70% (in average 1:50,000) 3. Introduce 15 ALS ambulance for selected big cities in the country 4. Conduct base line Community satisfaction assessment and improve from the base line by 10% every year |

| Strengthen EMS system network | Establish call & dispatch center which will work with the set standards in all regions/zones |

| Reduce the health impact of natural and manmade disasters | Develop National medical disaster response system |

| Strengthen community-based emergency prevention and response | 1. Deliver first aid training to 100,000 people 2. Develop community-based injury and acute illness prevention awareness 3. Improve Job safety standards implementation |

| Improvement of facility-based emergency care | 1. Develop 2 nationally, to serve as centers of excellence in teaching, service and research 2. Advance 20 EDs to advanced EDs, 50EDs to intermediate level ED and all other EDs to basic level. 2. Increase ED patients' satisfaction from 60% to 85%. 3. Reduce 24 h ED mortality to 0.2%. |

| Establish and strengthen emergency and critical care structure, and EM coordination and referral system | 1. Establish EMCC structure in 100% of regions/zones 2. Establish emergency coordination and referral system in all zones/regions 3. Establish national referral networking will be 4. Increase the proportion of referrals through networking and communication to 40% |

| Strengthen and scale up critical care services in health facilities | 1. Enhance 10 ICUs to level I, 20 ICUs to level II and 20 ICUs to level III 2. Initiate new ICUs in 40 additional hospitals 3. Reduce ICU mortality to 25% |

| Develop and strengthen trauma care system | 1. Establish 8 trauma units 2. Establish trauma care system in 10 major cities |

| Strengthen and expand burn care service in health facilities | Establish 8 burn units and 1 burn center |

| Initiate and strengthen poisoning center service at selected facilities | Establish 1 national toxicology center and 4 satellite poisoning information centers |

| Emphasize the development of emergency and critical care in emerging regions and special population groups | 1. Link 10 institutions from emerging regions with better setups 2. Enhance emergency care access for special population for 40% of selected institutions |

| Enhance collaboration, networking and engagement with national, regional and international partners | Train 320 emergency unit staff on NIEM course |

Ethiopia has made great strides to meet these objectives as described below but challenges still exist mentioned later in this paper.

Developments in out of hospital emergency care in Ethiopia

Out of hospital emergency care (OHEC) in most of the world is not formalized, haphazard and decentralized with Ethiopia being no exception. OHEC has been slow to develop but with the government's commitment to emergency care, OHEC has taken on a renewed focus. Currently there is no centralized dispatch or ambulance service throughout the country. There are private enterprises in Addis Ababa that provide OHEC but are disjointed and do not cover the entirety of the city.

Currently, ambulance services are used mainly for maternal and child emergencies. Ambulances are also used for transport between facilities. Ambulance services have been utilized for mass casualty events, religious, cultural, and political mass gatherings. The ambulance service need has been growing with/in the country given the high prevalence of injury due to a growing population, urbanization, motorization and industrialization. Even with the purchase of numerous ambulances a large gap still exists.

The MoH, through community mobilization and matching funds, has procured 1153 ambulances over the last 2 years by partnering with regional health bureaus that mobilize the community to pay for 50% of the ambulance while the MOH pays the other 50%. According to the Ethiopian ambulance service utilization guidelines, ambulance dispatch should be prepared and established by city administration and woreda (districts) with a population of 100,000 individuals. The ministry has worked with other partners to establish standardized dispatching systems. The directorate has prepared a national ambulance protocol guiding document.

OHEC also consists of disaster management and early response to all-hazards. The ECCD provides facility-based surge capacity planning as well as a coordinated response to national disasters. To tackle this endeavor, the ECCD has developed a disaster management plan for hospitals including a checklist adapted from the WHO-Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office(EMRO) (http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/268766/Hospital-emergency-response-checklist-Eng.pdf) tool to equip all size hospitals and health facilities with the ability to have their own disaster management plan.

As part of disaster preparedness, the ECCD developed disaster medical assistance teams (DMAT). The DMAT initiative started at the Directorate with national emergency leaders taking a 2-day intensive disaster management course. Leaders ranged from health officers, nurses, and emergency specialists as well as surgeons, anesthesiologists, and general practitioners. These leaders then trained regional counterparts to respond to regional hazards. The DMAT teams have responded to five different incidents at the national and sub-national levels including large scale public mass gatherings and conflict related mass casualty incidents. The team was also deployed during the tragic Ethiopian Airlines crash in 2019. A key missing component, learned from the tragic crash, is training on forensic procedures for the deceased which would be useful to include in further disaster management trainings.

Health worker education

Training of emergency medicine physicians

Training began when six core faculty members from the EMTF were trained in the United States at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public health in emergency medicine sponsored by the MoH [20]. These individuals returned to Ethiopia under the EMTF to organize emergency medical services and graduate level training at AAUSOM [20]. Members from the EMTF developed curricula for an emergency medicine residency program as well as an emergency care and critical care (EMCC) nursing masters-level program [20,21]. The initial emergency medicine residency was developed for 3 years and the EMCC nursing masters level program for 2 years launched in 2010 [20].

There are now two residency programs in Ethiopia. Since the emergency medicine residency training program started in Ethiopia, 48 residents and 153 nurses have graduated from these programs. Though most graduates work in the capital city of Ethiopia, a good portion 30% of physicians and 40% of nurses of the graduates work in major cities outside of the capital. Most graduates work in Addis Ababa as leaders in emergency medicine training and service. Given the rapid expansion of emergency care in Addis Ababa more opportunities are available for trained emergency practitioners. The lack of organized emergency units and adequate teams trained in emergency and critical care outside Addis are also contributing factors to the paucity of emergency graduates working outside of Addis Ababa [22].

National Integrated Emergency Medicine (NIEM) training

The Ministry of Health established the Emergency and Critical Care Directorate in 2015 with a focus on capacity building and human resource development. Since the country would not be able to produce emergency professionals in parallel with the need, the Ministry developed the National Integrated Emergency Medicine course. NIEM is a five-day comprehensive training designed to provide all levels of health care workers with basic emergency medicine training, knowledge and skills to practice life-saving interventions in both the out of hospital and hospital settings. NIEM focuses on utilizing available resources to perform skills and procedure. This course was developed by a group of emergency care physicians and emergency trained nurses with a focus on the major illnesses presented to the Emergency Units. The objectives of the course are to describe the organization and function of emergency units, detect and manage ABC (airway, breathing, circulation) emergencies, describe and manage common medical, surgical, gynecologic, obstetric and pediatric emergencies. To date, 120 health facilities have received NIEM with 610 professionals trained. The challenges with the dissemination of NIEM included the heavy theory-based lessons, making it difficult for non-physicians to comprehend the material.

World Health Organization (WHO)-ECCD collaboration

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed an emergency care system toolkit with a complementary range of materials to assist countries in developing emergency care systems (https://www.who.int/health-topics/emergency-care#tab=tab_1). In 2016, the MoH executed a national WHO Emergency Care System Assessment (ECSA) a process designed to help policy-makers and planners assess the national emergency care system, identify gaps and set priorities for system development across the following areas: system organization, governance and financing; data and quality improvement; scene care, transport, transfer; facility-based care; and emergency preparedness. The ECSA process entailed gathering input from a wide range of national stakeholders, including policymakers, clinical providers, administrators, private sectors, and others via a structured web-based tool. This was followed by a 2-day in-person meeting to determine consensus responses and derive and prioritize context-relevant action priorities. The ECSA process in Ethiopia was informed by a large survey of primary, general and tertiary hospitals led by the ECCD of the MoH. Priority actions identified in the ECSA were ranked on a range of criteria and used to develop the MoH Directorate of Emergency and Critical Care 5-year plan (objectives mentioned previously). The priorities based on this evaluation highlighted the need for mapping coordination across agencies, improving systematic data collection and use of emergency care data for system planning and emergency care training at all levels. Ethiopia has also been identified as one of the countries for the Implementation of GETI (The Global Emergency and Trauma Initiative) that strengthens the advocacy for and collaboration in emergency care systems.

The MoH and WHO, collaborated to establish the WHO Basic Emergency Care (BEC) course in Ethiopia for first line providers. The BEC course is geared towards providing and preparing medical providers on the frontline to recognize, evaluate and treat life-threatening conditions. This complements NIEM as NIEM is for more advanced practitioners and BEC is for frontline providers working in primary heath units. Following the trainer of trainees (TOT) model, the initial training took place in November 2018, training a total of 35 medical providers including emergency specialists, health officers and registered nurses. The 35 original master trainers trained additional regional trainers reaching 165 ToT trainers in BEC. To date, there have been 2525 healthcare workers trained in BEC, at a total of 155 woredas (districts) and 714 health care centers across Ethiopia.

The WHO-MoH collaboration has deepened with the plan to implement the entire toolkit in selected primary hospitals for concentrated impact monitoring and evaluation. This includes the BEC training itself, development of a triage system, standardized medical and trauma charts and checklists, and development of a resuscitation area. This collaboration between the MoH and WHO also includes the implementation of an international registry for trauma and emergency care, a tool designed to standardize the approach and charting for trauma and emergency, patients and provides much needed information about trauma incidence and care within the country. The goal is to implement these complementary services in 6 major cities throughout Ethiopia.

Other developments locally and globally

The Ethiopia's Health Sector Transformation Plan agenda aims at revamping healthcare provision at several levels of healthcare provision. The ECCD integrated and aligned its agenda with this transformation plan and is ensuring provision of emergency care at each level of the health system as well as creating referral linkages to improve patient outcomes. Emergency and critical care services are among the high priority areas in the revised Essential Health Services Package and have an implication on guiding further government investment and commitment.

The Ministry of Health of Ethiopia along with the Ministry of Health of Eswatini championed the efforts on Emergency Care to bring a resolution on Emergency Care at the 72nd World Health Assembly to ensure access and timely health care (https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_R16-en.pdf?ua=1). With Universal Health Care (UHC) dominating the agenda both at the World Health Assembly and High-Level Discussions at the United Nations General Assembly, the 72nd World Health Assembly offered a unique opportunity to bring the call for increased investment in Emergency Care Systems and emphasize the importance of fully integrating emergency care into ongoing universal health coverage planning processes (https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/97/9/19-240440/en/). Providing timely care for all acutely ill and injured persons, emergency care is an essential foundation for the execution of disease and population-specific health agendas. The 72nd World Health Assembly under the theme of “Universal Health Coverage: Leaving No-one Behind,” delegates from around the world convened to discuss health issues of global significance and among other actions, passed a pathbreaking resolution on emergency care (https://issuu.com/saemonline/docs/saem_pulse_sep-oct_19/16?ff).

The road to a WHA resolution is a long one—months prior to the Assembly, the Governments of Ethiopia and Eswatini proposed an item on emergency and trauma care, thus placing the topic on the agenda for discussion at WHA and calling on WHO to provide a background technical report. Ethiopia and Eswatini began working on a draft resolution, and a series of negotiations chaired by the Ethiopian representative over weeks to ensure that the language of the resolution captured the needs and priorities of all Member States (https://www.acepnow.com/article/the-world-health-assembly-adopts-an-emergency-care-resolution/).

With the commitment and cooperation of dozens of countries, the resulting resolution included a range of provisions on key issues, including creating policies for the provision of high-quality emergency care, financial risk protection, support and protection of frontline providers. After deliberation, the resolution was passed unanimously on May 25th, a triumphant moment for emergency medicine.

While this resolution will not solve all the problems in Emergency Care, we believe this resolution will gear policy makers towards the right direction to create policies for sustainable funding, effective governance and universal access to safe, high-quality, needs-based emergency care for all without regard to sociocultural factors and requirement for payment prior to care. With the advent of the resolution, it comes with no surprise that Ethiopia's upcoming Health Sector Transformation Plan (2020–2024) includes emergency care action items outlined in the resolution and interventions at each level of the health system. The ECCD of the FMOH has devised a plan to meet the resolution mandated with a timeline for meeting the resolution mandates with specific targets.

Sustainable Development Goals, WHA resolution and emergency care

With the passage of the WHA resolution on emergency care it is now noted that it is a crucial component of universal health care. With the resolution there are certain mandates that member states need to meet in order to comply with the resolution. Many of these correspond to the SDGs. Therefore, emergency care is crucial in achieving SDG 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. Emergency care is a cross-cutting discipline and the frontline for medical care. Without a robust emergency care system SDG 3 is unlikely to be met. Therefore, the resolution empower member states promote and implement robust emergency care systems.

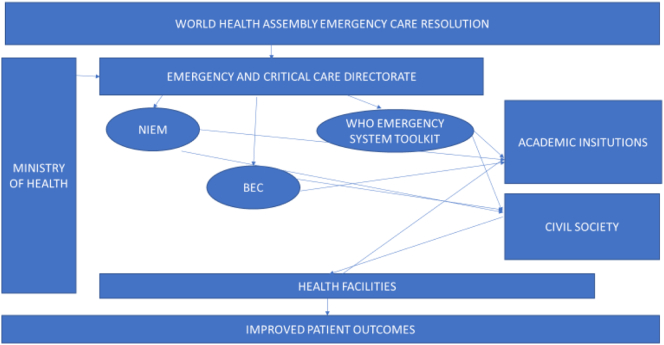

To better understand the relationship of emergency care in Ethiopia the following diagram (Fig. 1) has been developed.

Fig. 1.

Current emergency medicine structure in Ethiopia.

Challenges and suggestion

Despite all the concerted efforts in Ethiopia, Ethiopia's trained and specialized health workforce, the goal to provide timely emergency care has not been met for many reasons. We outline some of the challenges and possible solutions in Table 2.

Table 2.

Challenges and solutions for emergency care in Ethiopia.

| Challenges | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Specialized training at all hospitals |

|

| Lack of support from other specialties | |

| Improper ambulance utilization services |

|

| Lack of equipment and essential drugs |

|

Conclusion

Ethiopia, as a LMIC, has made great strides to develop a robust emergency care system within a short timeline. Many of the achievements stem from the governmental commitment to strengthening emergency and critical care. Without the support of the government the speed with which the emergency care system is changing would not be possible. Despite this commitment more work is needed to train individuals in basic emergency care, develop an out of hospital emergency care system and develop functioning, well-staffed emergency units at the facility level.

Dissemination of results

This was a discussion of the triumphs and challenges of emergency care human resources in Ethiopia and was shared with the Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Authors contributed as follow to the conception or designing of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: TF 35%; AG 10%; LW 10%; FE 10%; SP 35%. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

A seven- to eight-year gap between the Ethiopian and Gregorian calendars. Therefore, the Ethiopians celebrated the new millennium on September 1, 2000 Ethiopian calendar (September 12, 2007 Gregorian calendar).The Ethiopian and Coptic calendars consist of 13 months where the first 12 months have 30 days each, and the Last (thirteenth) month has 5 days (6 days in a leap year).

References

- 1.Reynolds T.A., Sawe H., Rubiano A.M., Do Shin S., Wallis L., Mock C.N. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017. Strengthening health systems to provide emergency care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suter R.E. Emergency medicine in the United States: a systemic review. World J Emerg Med. 2012;3(1):5. doi: 10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Working together for health. 2006. www.wma.net Published online.

- 4.World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030.

- 5.World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa Brazzaville . 2013. Adopted by the sixty-second session of the regional committee. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewin S., Munabi-Babigumira S., Glenton C. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2017(10) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Task Shifting Global Recommendations and Guidelines HIV/AIDS.

- 8.Van Lerberghe W., Matthews Z., Achadi E. Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. Lancet. 2014;384(9949):1215–1225. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60919-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jaskiewicz W. World Health Organization Phouthone Vangkonevilay, Lao PDR Ministry of Health Chanthakhath Paphassarang, Lao PDR Ministry of Health Inpong Thong Phachanh, Lao PDR Ministry of Health Laura Wurts; 2012. IntraHealth International Outavong Phathammavong. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingue S., Rosskam E., Bela A.C., Adjidja A., Codjia L. Renforcer les ressources humaines pour la santé à travers un leadership et des approches multisectorielles: Le cas du Cameroun. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(11):864–867. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.127829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell J., Buchan J., Cometto G. Human resources for health and universal health coverage: fostering equity and effective coverage. Campbell, J., Buchan, J., Cometto, G., David, B., Dussault, G., Fogstad, H., … Tangcharoensathien, V. (2013). Human resources for health and universal health. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:853–863. doi: 10.2471/BLT.13.118729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strengthening human resources for health through information, coordination and accountability mechanisms: the case of the Sudan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3853958/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Gauchan B., Mehanni S., Agrawal P., Pathak M., Dhungana S. Role of the general practitioner in improving rural healthcare access: a case from Nepal. Hum Resour Health. 2018;16(1) doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0287-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pavignani E. Human resources for health through conflict and recovery: lessons from African countries. Disasters. 2011;35(4):661–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2010.01236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosewell A., Bieb S., Clark G., Miller G., MacIntyre R., Zwi A. Human resources for health: lessons from the cholera outbreak in Papua New Guinea. West Pac Surveill Response J WPSAR. 2013;4(3):9–13. doi: 10.5365/WPSAR.2013.4.2.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uwizeye G., Mukamana D., Relf M. Building nursing and midwifery capacity through Rwanda’s human resources for health program. J Transcult Nurs Off J Transcult Nurs Soc. 2018;29(2):192–201. doi: 10.1177/1043659617705436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cancedda C., Cotton P., Shema J. Health professional training and capacity strengthening through international academic partnerships: the first five years of the human resources for health program in Rwanda. Int J Heal Policy Manag. 2018;7(11):1024–1039. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binagwaho A., Kyamanywa P., Farmer P.E. The human resources for health program in Rwanda - a new partnership. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(21):2054–2059. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1302176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ndenga E., Uwizeye G., Thomson D.R. Assessing the twinning model in the Rwandan Human Resources for Health Program: goal setting, satisfaction and perceived skill transfer. Glob Health. 2016;12(1) doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0141-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Azazh A., Teklu S., Woldetsadi A. Emergency medicine and its development in Ethiopia with emphasis on the role of Addis Ababa University, School of Medicine, Emergency Medicine Department. Ethiop Med J. 2014;(Suppl. 2):1–12. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25546904 Accessed August 6, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teklu S., Azazh A., Seyoum N. Development and implementation of an emergency medicine graduate training program at Addis Ababa University School of Medicine: challenges and successes. Ethiop Med J. 2014:13–19. Published online July 1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sultan M., Debebe F., Azazh A. vol. 56. 2018. The status of emergency medicine in Ethiopia, challenges and opportunities.https://www.emjema.org/index.php/EMJ/article/view/767 [Google Scholar]