Highlights

-

•

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is confined to the mediastinum or contiguous nodal areas in most cases.

-

•

PMBCL is characterized by a rapidly growing mediastinal mass, frequently accompanied by local invasiveness.

-

•

Gastrointestinal involvement of PMBCL may cause serious complications such as intestinal perforation.

-

•

PET-CT increases the sensitivity of staging by detecting unusual sites of disease localization.

Keywords: Large B-cell diffuse lymphoma, Bowel perforation, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Extra-nodal extension, Chemotherapy

Abstract

Introduction

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is an uncommon subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (2–3%), predominantly occurring in female young adults. Extrathoracic involvement is found in 10–20%. It can affect the kidneys, pancreas, stomach, adrenal glands, liver, and infrequently the central nervous system (6–9%). There is currently only one reported case of ileum dissemination with a single perforation.

Presentation of case

A 51-year-old woman with a history of PMBCL, hospitalized by a superior vena cava syndrome. PET-CT showed numerous lesions in the small intestine, pancreas, adrenal glands, and left kidney. During chemotherapy she presented abdominal symptoms, requiring an emergency laparotomy. On examination, six perforation sites were found in the small intestine. The pathology report revealed lesions compatible with PMBCL spread.

Discussion

There are few case series with reports of dissemination in the gastrointestinal tract, with the main location in the stomach. Knowing the visceral location of the PMBCL would allow us to plan a strict follow-up during the first phases of chemotherapy treatment, as well as the early diagnosis of unexpected complications, such as intestinal perforation.

Conclusion

The PMBCL is a rare entity. Visceral involvement should be suspected in these patients since intestinal perforation represents a complication with high morbidity and mortality. This is the first case reported with numerous intestinal locations and multiple post-chemotherapy perforations.

1. Introduction

Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is an aggressive B-cell lymphoma, accounting for 2–3% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL). It predominantly affects women, in a 2:1 ratio compared to men, commonly in their fourth decade of life [1]. It was previously considered a subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; however, in 2008 the World Health Organization has recognized PMBCL as a unique entity with different clinical and biological characteristics [2].

The most frequent presentation is as an oncological emergency, with a large anterior mediastinal mass that invades adjacent structures such as the pleura, lungs, and/or pericardium, and consequently a superior vena cava (SVC) syndrome [3,4].

We present the first case of a patient diagnosed with PMBCL with numerous extrathoracic locations and multiple intestinal perforations. This manuscript is reported in line with the SCARE criteria [5].

2. Presentation of case

A 51-year-old woman with a history of class I obesity (BMI 30 kg / m2) and a recent diagnosis of PMBCL (one month), no history of allergies, drug use, tobacco, alcohol abuse, or genetic alterations. She consulted with dyspnoea, chest discomfort, and facial swelling. She also reported febrile episodes, chills, and weight loss in recent weeks. On admission, her vital signs were: blood pressure 160/100 mmHg, pulse 110 / min, respiratory rate 24 / min, SpO2 89%, and body temperature 36 °C. On physical examination, she presented facial, neck, and upper trunk edema, with visible congested vessels consistent with SVC syndrome. Pre-phase treatment was started with steadily increasing corticosteroids (dexamethasone: 8 mg / d, 16 mg / d, up to 24 mg / d) and vincristine 2 mg / d.

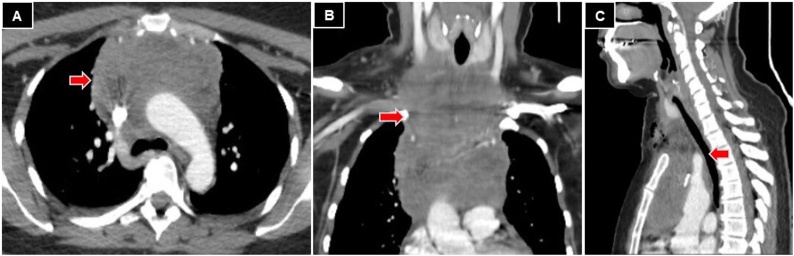

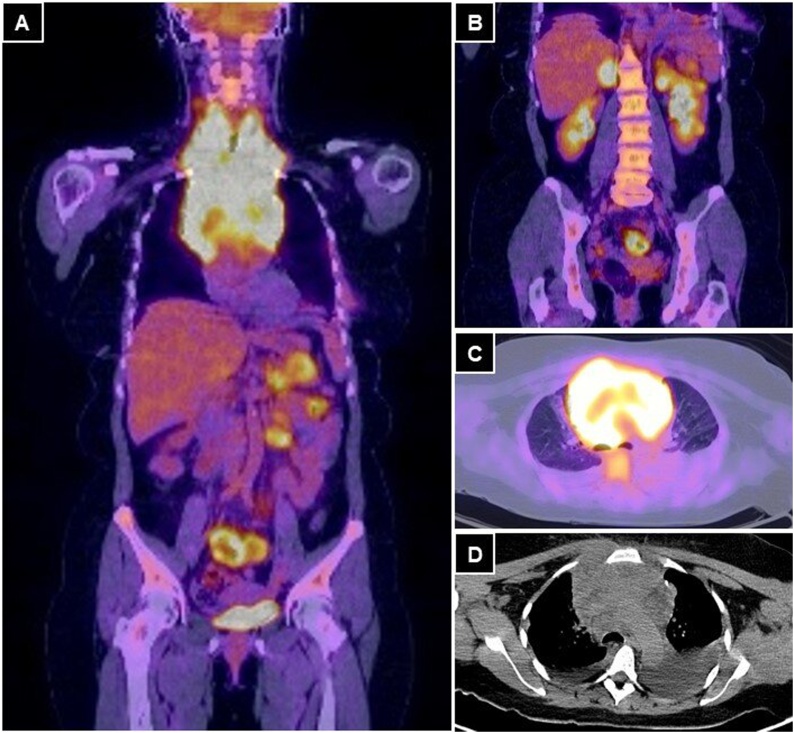

Chest computed tomography (CT) was performed, which showed a solid lesion of 14 × 10 × 7 cm in the craniocaudal, transverse, and anteroposterior diameters, respectively; that occupied the anterior mediastinum, in relation to the aortic arch and its branches. It also compromised SVC and it was in contact with the trachea and esophagus (Fig. 1). The tumoral stage was confirmed with a PET-CT that showed an intensely hypermetabolic tumor, of 18 × 12 × 11 cm in craniocaudal, transverse, and anteroposterior diameters, respectively; that involved neck vessels, aorta, SVC, and bilateral pulmonary nodules, with bilateral pleural effusion. In the abdominal cavity, hypermetabolic nodules were found in both adrenal glands, a left renal nodule, a lesion in the tail of the pancreas, and multiple hypermetabolic areas in the small bowel loops (Fig. 2). The bone marrow biopsy and cerebrospinal fluid analysis were negative.

Fig. 1.

Chest CT. A: axial view, neoproliferative lesion in the anterior mediastinum (red arrow). B: coronal view, 14 × 10 × 7 cm prevascular lesion (red arrow). C: sagittal view, tumor in contact with the esophagus and trachea (red arrow).

Fig. 2.

A and B: PET-CT coronal view, with multiple hypermetabolic foci in the small bowel wall, in both adrenal glands, in the left kidney and a tumor with an infiltrative aspect in the tail of the pancreas. C and D: axial views of a voluminous hypermetabolic mass in the anterior mediastinum that encompasses the great vessels.

The performance status of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group [6] was 2. It was classified as clinical stage IVB, with an International Prognostic Index (IPI) [7] of 4, considered high risk.

The patient presented clinical improvement, without acute tumor lysis due to the pre-phase treatment. At nine days, chemotherapy was started with the R-CHOP scheme (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone).

On the second-day post-chemotherapy, she presented sudden onset abdominal pain of severe intensity. The physical examination found blood pressure 150/100 mmHg, pulse 120 / min, respiratory rate 22 / min, SpO2 92%, and body temperature 37.7 °C, with abdominal guarding and generalized rebound tenderness.

The laboratory reported C - reactive protein 350 (VN: <5 mg / l), LDH: 2087 (VN: 105 - 333 IU / l), the rest of the parameters didn’t have alterations.

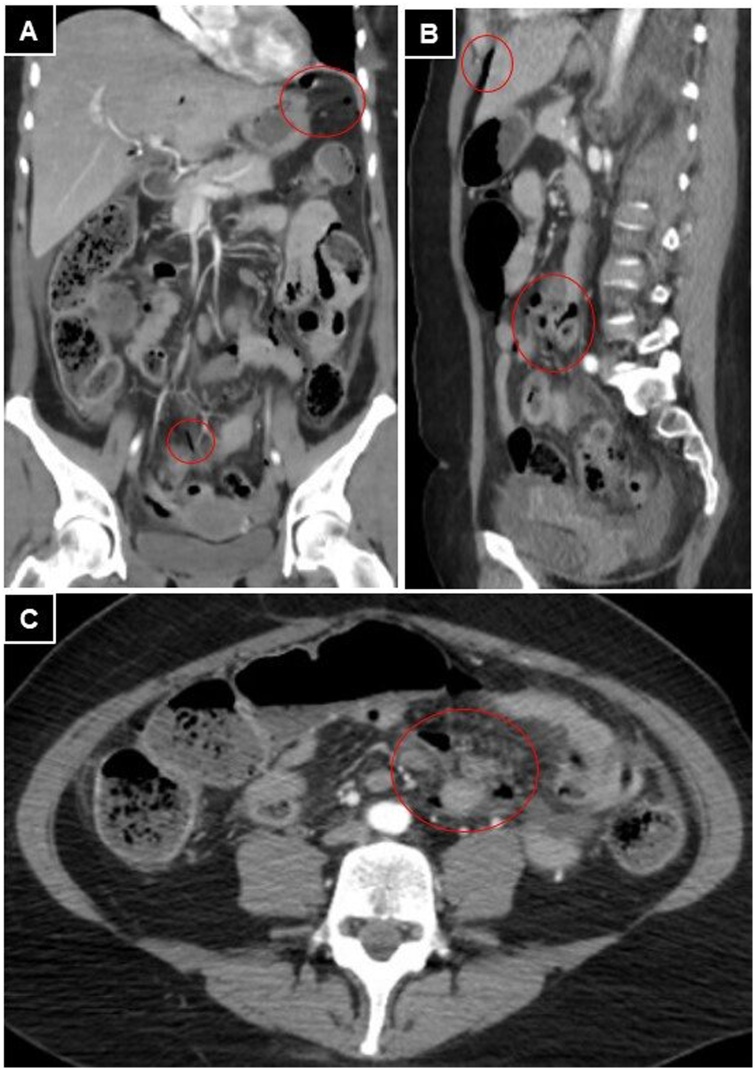

An abdominal CT scan showed the presence of extraluminal gas, free fluid, and paralytic ileus with parietal thickening with defect areas, compatible with multiple intestinal perforations (Fig. 3). Emergency surgery was decided.

Fig. 3.

Abdominal and pelvis CT. A, B, and C: presence of free intraperitoneal air (red circles) and free fluid in the decline regions of the abdomen.

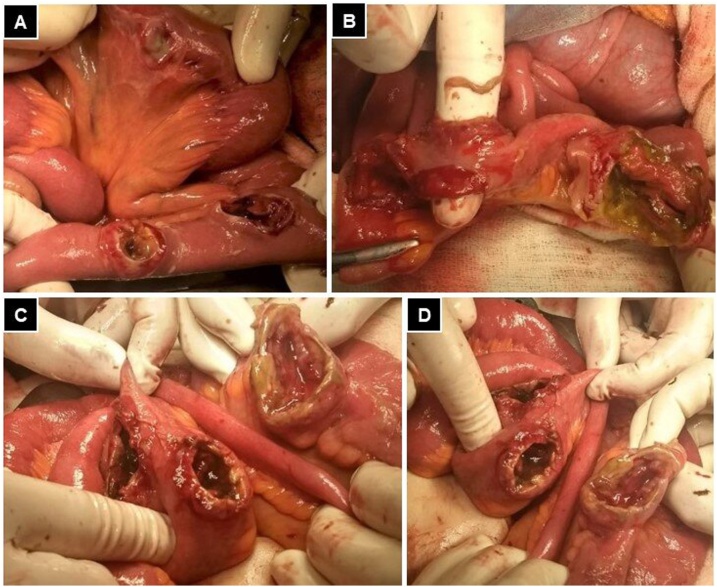

An exploratory laparotomy was performed and revealed moderate enteric fluid in the abdominal cavity and six perforation sites on the wall of the small intestine, described from the angle of treitz to the ileocecal valve at 35, 40, 60, 130, 150, and 200 cm (Fig. 4). During surgery, the patient presented hemodynamic instability that improved after volume and vasoactive drug administration. Three simple closures were performed in those perforations that did not compromise more than 50% of the circumference and resection with primary anastomosis in a 70 cm segment of the small intestine, where the perforations presented necrotic borders. The surgical time was three hours, with an estimated blood loss of 250 cc. Blood transfusion was not required.

Fig. 4.

A: three isolated tumoral lesions are observed that were repaired with simple raffia. B, C and D: presence of consecutive lesions in the small bowel segment with transmural involvement and devitalized margins.

Immediate postoperative follow-up was performed in the intensive care unit. Fifteen days after surgery, hospital discharge was indicated due to a favorable evolution, with scheduled controls to continue with chemotherapy.

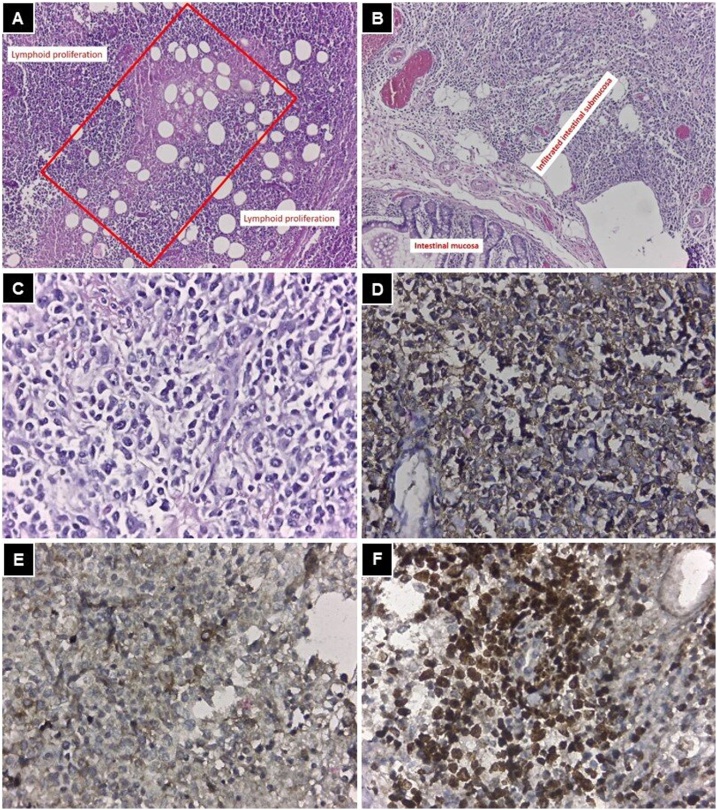

The pathology report revealed infiltration by malignant neoplasia compatible with NHL, with positive immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CD20, CD30, Bcl-2, and with a proliferation index > 50% (Ki67) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

A: mediastinum (HE 100x), central necrotic area (red rectangle), which indicates that the neoplasm is aggressive and proliferation of cells with scarce cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei around it. B: small bowel (HE 100x), the intestinal mucosa is seen without neoplastic infiltration, while from the submucosa to the serosa it is infiltrated by the neoplasm. C: HE 400x, cells that infiltrate the intestine with the same characteristics as the mediastinal ones. D: IHC positive for CD20, identifying B lymphocytes. E: IHC positive for CD30. F: Ki67 +, with more than 50% of the cells in on mitosis indicating a high-grade lymphoma.

Chemotherapy was restarted 30 days after surgery, receiving three cycles of R-CHOP regimen. Due to evidence of progressive deterioration of her general condition, chemotherapy was suspended, and she died four months after surgery.

3. Discussion

PMBCL was described for the first time in 1980, based on a review of 184 cases in adults with NHL, corresponding to a subtype of lymphoma with highly aggressive behavior [4]. Only 20% of patients have B symptoms and 80% increase lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [8], similar to the clinical findings found in the patient.

Extrathoracic involvement at the time of diagnosis represents 10–20%. With the progression of the disease, its dissemination can involve the kidneys, pancreas, adrenal glands, liver, stomach, ovaries, bone, bone marrow, and rarely the central nervous system (6–9%) [9]. However, these organs are more frequently affected during relapses (93%) [9].

The clinical management of PMBCL varies among hospitals, without a standard of care. Currently, there is no consensus on the optimal chemotherapy regimen [10]. In the United States, the R-CHOP regimen has historically been the standard treatment for PMBCL, which is also radiosensitive. The combination of chemotherapy followed by mediastinal radiation therapy has been shown to be associated with a 5-year survival rate of 75–85% [8]. However, the role of radiation therapy in all patients, particularly those with a good response to chemotherapy, remains uncertain [11]. The patient in this report presented numerous complications as a consequence of the local and distant invasion, both at the time of diagnosis and post-treatment follow-up, the reason for which chemotherapy was suspended and she did not receive radiotherapy.

Perforation has been reported after chemotherapy in patients with intestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, with a mean presentation of 46 days after chemotherapy began [12]. In PMBCL with gastrointestinal location, we found no information in this regard.

The stages of PMBCL are classified in the same way as other lymphomas. It is classified by measuring infiltrated lymph node groups, their relationship with the diaphragm, the extension to extra lymphatic organs, and patient symptoms [13]. 75% of patients present a tumor greater than 10 cm at the time of diagnosis, and they are in clinical stage I or II [6]. In this case, a clinical stage IVB and an IPI of 4 were established, which implies an infrequent initial presentation and a 26% overall survival at 5 years, and a 44% complete response to treatment.

PET-CT with fluorodeoxyglucose is considered the most sensitive and specific technique for classifying the stage of lymphoma in patients. It is used to evaluate responses before, during, and after treatment, since the metabolic changes precede the morphological ones [14,15]. In this case, our patient`s PET-CT was performed at the most stable moment of her clinical evolution, allowing us to detect numerous extrathoracic locations during the initial staging. The prognostic value and knowledge of unusual PMBCL locations with PET-CT can change the clinical approach, which would support the inclusion of this imaging study at the time of diagnosis, making the detection of gastrointestinal involvement possible [13,16].

Gastrointestinal involvement by PMBCL is extremely rare. It has been reported in a cohort of 204 patients, where only one patient showed evidence of gastric involvement [16].

There is currently only one reported case of PMBCL with ileal dissemination [13], in which the patient presented rebound tenderness during treatment with corticosteroids, which led to surgical exploration, finding a single site of intestinal perforation. In our case, the abdominal symptoms appeared after chemotherapy in the context of a SVC syndrome, which initially responded favorably to the corticosteroids administration. This report would be the second case with intestinal dissemination, but unlike the first one, multiple perforation sites were found on surgical exploration. The real incidence at this location is unknown.

Knowing the visceral location of the PMBCL would allow us to plan a strict follow-up during the first phases of treatment or to anticipate complications, such as intestinal perforation [13,17]. Gradual treatment was started in the patient before formal chemotherapy to assess the impact of tumor lysis. However, intestinal perforation could also be conditioned by factors specific to the tumor.

4. Conclusion

PMBCL is an infrequent neoplasm that could present visceral involvement, which should be studied in depth before starting chemotherapy and should be highly suspicious of eventual intestinal perforation since it represents a complication with high morbidity and mortality. This is the first case reported with numerous intestinal locations and multiple post-chemotherapy perforations.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Funding

No source to be stated.

Ethical approval

This is a case report study and ethical approval not required.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Dr. René Manuel, Palacios Huatuco (data analysis and interpretation, writing the paper).

Dr. Diana Alejandra, Pantoja Pachajoa (data analysis and interpretation, writing the paper and approved the final version).

Dr. Agustín Ezequiel, Pinsak (data collection and data analysis).

Dr. Luciano, Salvano (literature review and data analysis).

Dr. Alejandro Marcelo, Doniquian (study concept and approved the final version).

Dr. Facundo Ignacio, Mandojana (literature review and surgical treatment of the patient).

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Dr. René Manuel, Palacios Huatuco: manuelpalacioshuatuco@gmail.com.

Dr. Diana Alejandra, Pantoja Pachajoa: dianaalejandrapantoja@gmail.com.

Dr. Facundo Ignacio, Mandojana: facundomandojana@gmail.com.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Patient perspective

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gabriela Sambuelli: Contribution to the paper: Histopathological examination, interpretation of the histological pictures, immunohistochemically examination.

References

- 1.Harris N.L., Jaffe E.S., Stein H., Banks P.M., Chan J.K., Cleary M.L. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84(5):1361–1392. doi: 10.1182/blood.v84.5.1361.bloodjournal8451361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campo E., Swerdlow S.H., Harris N.L., Pileri S., Stein H., Jaffe E.S. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117(19):5019–5032. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-293050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazzarino M., Orlandi E., Paulli M., Sträter J., Klersy C., Gianelli U. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors for primary mediastinal (thymic) B-cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 106 patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 1997;15(4):1646–1653. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.4.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lichtenstein A.K., Levine A., Taylor C.R., Boswell W., Rossman S., Feinstein D.I. Primary mediastinal lymphoma in adults. Am. J. Med. 1980 doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(80)90294-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A.J., Orgill D.P. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oken M., Creech R., Tormey D., Horton J., Davis T., McFadden E. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 1982 doi: 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.A predictive model for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993 doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giulino-Roth L. How I treat primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 2018 doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-791566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishop P.C., Wilson W.H., Pearson D., Janik J., Jaffe E.S., Elwood P.C. CNS involvement in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999 doi: 10.1200/jco.1999.17.8.2479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malenda A., Kołkowska-Leśniak A., Puła B., Długosz-Danecka M., Chełstowska M., Końska A. Outcomes of treatment with dose-adjusted EPOCH-R or R-CHOP in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Eur. J. Haematol. 2020 doi: 10.1111/ejh.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zelenetz A.D., Gordon L.I., Abramson J.S., Advani R.H., Bartlett N.L., Caimi P.F. NCCN guidelines insights: B-cell lymphomas, version 3.2019. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019 doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2019.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vaidya R., Habermann T.M., Donohue J.H., Ristow K.M., Maurer M.J., Macon W.R. Bowel perforation in intestinal lymphoma: incidence and clinical features. Ann. Oncol. 2013 doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Philippis C., Di Chio M.C., Sabattini E., Bolli N. Bowel perforation from occult ileal involvement after diagnosis in a case of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. BMJ Case Rep. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-216317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juweid M.E., Stroobants S., Hoekstra O.S., Mottaghy F.M., Dietlein M., Guermazi A. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the imaging subcommittee of international harmonization project in lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2007 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cheson B.D., Fisher R.I., Barrington S.F., Cavalli F., Schwartz L.H., Zucca E. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Papageorgiou S.G., Sachanas S., Pangalis G.A., Tsopra O., Levidou G., Foukas P. Gastric involvement in patients with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:6717–6723. PMID: 25368280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lees C., Keane C., Gandhi M.K., Gunawardana J. Biology and therapy of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: current status and future directions. Br. J. Haematol. 2019;185(1):25–41. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]