Abstract

Background

Liver transplantation is the main treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). However, because of the limited supply of transplant organs, it is necessary to adopt a criterion that selects patients who will achieve adequate survival after transplantation. The aim of this review is to compare the two main staging criteria of HCC for the indication of liver transplantation (Milan and UCSF) and to analyze the post-transplantation survival rate at 1, 3 and 5 years.

Methods

This is a systematic review and meta-analysis in which scientific articles from 5 databases (PubMed, Lilacs, Embase, Central, and Cinahl) were analyzed. The studies included in the review consisted of liver transplantation in patients with HCC in different subgroups according to donor type (deceased × living), population (eastern × western) and tumor evaluation (radiological × pathological) and adopted the Milan or UCSF criteria for the indication of the procedure.

Results

There was no significant difference between the Milan and UCSF criteria in the overall survival rate at 1, 3 or 5 years, and the overall estimated value found was 1.03 [0.90, 1.17] at 1 year, 1.06 [0.96, 1.16] at 3 years and 1.04 [0.96, 1.12] at 5 years. Regarding the analysis of the subgroups, no significant difference was observed in any of the subgroups with a follow-up of 1, 3 or 5 years.

Conclusions

Both the Milan and UCSF criteria have equivalent survival rate. Thus, less restrictive method would not result in a great loss in the final overall survival rate and would benefit a greater number of patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation, liver diseases

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary cancer of the liver. It has an age-adjusted global incidence of 10.1 cases per 100,000 person-years, and it is ranked as the sixth most common neoplasm and the third leading cause of cancer death. HCC has been recognized as one of the leading causes of death among patients with cirrhosis, and it is estimated that the incidence of HCC will increase in the future (1).

HCC onset is usually based on chronic liver disease, but an increase in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is observed, even before cirrhosis. Most cases of HCC (80%) occur in sub-Saharan Africa and eastern Asia, where the major risk factors are hepatitis B infection and aflatoxin B1 exposure. In the US, Europe, and Japan, hepatitis C and alcohol abuse are major risk factors (2-4).

The staging of HCC is a crucial step in choosing the treatment strategy. In addition, since most patients have associated liver disease, the evaluation of these patients should incorporate not only the stage of the tumor but also the degree of impairment of liver function. Several proposals were made to stratify patients according to the results of exams (5). The most relevant are the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) (6), which has already been widely validated and is the most commonly used for the staging HCC, and the traditional TNM (Tumor, Node, Metastasis) systems. Other systems also exist, such as those developed by the Italian Program of Cancer of the Liver, the Groupe d’Étude et de Traitément du Carcinome Hépatocellulaire, the Chinese University Prognostic Index, the Japanese Integrated Staging System, the Taipei Integrated Scoring System, and more recently, the Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system (7).

The goal of treatment is to increase survival rate by maintaining the patient’s quality of life. Achieving the best outcome requires careful selection of candidates for each treatment option.

Liver transplantation for HCC

In general, liver transplantation is the best treatment option because it can cure both the tumor and the underlying cirrhosis. However, it should not be indicated in all cases. The probability of patient survival after transplantation remains the essential criterion for indicating this treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma.

The Milan criterion established by Mazzaferro et al. two decades ago (8) (single lesion ≤5 cm or up to three separate lesions, none larger than 3 cm) is the reference for predicting the best survival rate after transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma (>70% survival rate in 5 years, with a recurrence rate of <10% to 15%).

Since its inception, the Milan criterion has become the best predictor of good outcome and cost-effective transplantation. This criterion strongly influenced guidelines, recommendations and allocation policies for liver grafts from deceased donors (9-12). Over time, other criteria emerged for predicting the results of transplantation for HCC, beginning with that proposed by the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (single tumor ≤6.5 cm or ≤3 tumors with the largest tumor diameter ≤4.5 cm and total tumor diameter ≤8 cm) (13).

Since the implementation of the MELD (14) in 2002 as a model for the allocation of grafts in the USA and the philosophy of “the sickest first”, indications for HCC and its special scoring systems in the list have been questioned, favoring these patients to the detriment of other patients. However, the best analysis of the patient-favoring system shows that selecting HCC carriers for transplantation is the optimal method.

In this context, we chose to carry out a systematic review of existing publications using the Milan criteria and the UCSF criteria as a basis for indication of liver transplantation and to compare the overall survival rate between these groups.

Methods

This review is registered in International prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) about registration number CRD42016037265. The search strategy and selection of articles were based on the PRISMA guidelines.

A search, selection and evaluation of quality and data collection of the articles were carried out independently and systematically. The search was performed in 5 databases (PubMed, Lilacs, Embase, Central, and Cinahl), and there was no restriction regarding the language or date of publication of the articles. Only full-text articles were included.

The following sentence was used in PubMed: (Transplant * OR OLT) AND (Liver * OR Hepatic *) AND (Carcinoma * OR Hepatocellular * OR HCC) AND (“Milan” OR “UCSF”).

Included in the review were studies with hepatic transplantation (deceased × living donor) in patients with HCC, in which the Milan or UCSF criteria were adopted for the indication of the procedure. All selected clinical trials had data on the overall survival rate at 1, 3 or 5 years after liver transplantation according to the criteria adopted for the indication of transplantation, and global and subgroup analyses were performed.

In the case of studies with the same population, only the article containing the largest number of patients was included in the statistical analysis to ensure that there was no duplication of data. The risk of bias and quality of each included study were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale.

The following data were extracted from the studies: name of the author(s), year of publication, country, type of donor, follow-up time, type of study, method used for evaluation of tumor size (pathological × radiological) after 1, 3 or 5 years for both indication criteria (it was calculated when not explicitly stated) and the number of patients in the Kaplan-Meier curve being estimated, when not informed, for each time interval evaluated. The formula used for such estimation was described by Parmar et al. in 1998 (15).

For the statistical analysis of data, RevMan Software 5.0 (Cochrane; http://www.cochrane.org) was used. In the data analysis, because of variables of time to event (death), we opted for the calculation of hazard ratios, O-E and V, according to Wang et al. (16) and Vale et al. (17), following a meta-analysis of the data using the Peto Odds Ratio method {Exp [(O-E)/V], Fixed}. All results were indicated with 95% confidence intervals.

A sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate the heterogeneity among the studies, and articles with publication bias were eliminated to reach a value of heterogeneity (I2) <50%. To homogenize the obtained data and reduce bias, we performed analyses in a global manner and in subgroups (western × eastern population, deceased × living donor, pathological × radiological stratification).

Results

Selected studies

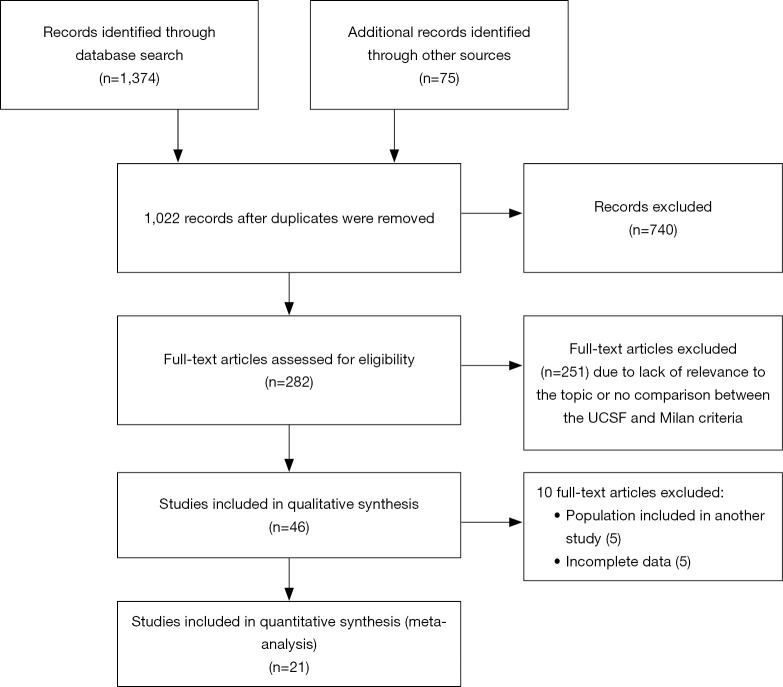

A total of 1,374 publications were identified in our search, of which 740 publications were excluded due to the lack of relevance to the topic. After the evaluation of the abstracts, 149 articles were excluded, and after reading the complete texts, another 92 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, did not have meta-analyzable data or they used the same populations as other papers. Finally, 21 articles were selected (18-38) for statistical analysis with a total of 5,569 patients (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Selection of articles from databases. The 21 eligible articles included a total of 5,569 patients. Articles with topics not relevant to the Milan and UCSF criteria, articles with incomplete data and articles with populations already studied in other articles were excluded.

Most of the work was performed in China (5), followed by Korea (4), the USA and France (3 studies each). Eleven studies were performed with western populations, totaling 1,067 patients, and 10 studies with eastern populations, totaling 4,502 patients. One study was prospective, and the other 20 were retrospective. Fifteen studies included deceased donor and living donor surgeries, and six studies evaluated the results of transplants only from living donors. The mean follow-up ranged from 19.6 to 96 months. All the studies obtained a good score in the Newcastle-Ottawa scale (>7). The characteristics of the studies and their individual results can be seen in the following tables (Tables 1,2).

Table 1. Selected articles for the meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | Criterion | Observation | Survival rate—UCSF | Survival rate—Milan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | |||||

| Yao (18) | 2002 | Pathological | 60 | 0.900 | 0.820 | 0.750 | 46 | 0.910 | 0.810 | 0.720 | ||

| Leung (19) | 2004 | Radiological | 81 | 0.858 | 0.648 | 0.519 | 74 | 0.859 | 0.637 | 0.509 | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | 46 | – | 0.881 | – | 42 | – | 0.899 | – | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | Living donor | 167 | – | 0.906 | – | 151 | – | 0.914 | – | |

| Decaens (21) | 2006 | Pathological | 223 | – | – | 0.695 | 184 | – | – | 0.704 | ||

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Pathological | Living donor | 50 | – | 0.760 | – | 43 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Radiological | Living donor | 41 | – | 0.780 | – | 37 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Kwon (23) | 2007 | Pathological | Living donor | 89 | – | – | 0.800 | 84 | – | – | 0.800 | |

| Lo (24) | 2007 | Pathological | 51 | 0.980 | 0.880 | 0.720 | 44 | 0.980 | 0.890 | 0.710 | ||

| Parfitt (25) | 2007 | Pathological | 59 | – | 0.771 | 0.726 | 50 | – | 0.830 | 0.830 | ||

| Lee (26) | 2008 | Pathological | Living donor | 174 | 0.874 | 0.800 | 0.759 | 164 | 0.866 | 0.794 | 0.760 | |

| Toso (27) | 2008 | Pathological | 193 | – | – | 0.800 | 157 | – | – | 0.820 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Pathological | 132 | 0.864 | 0.796 | 0.767 | 117 | 0.872 | 0.803 | 0.771 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Radiological | 126 | 0.873 | 0.786 | 0.731 | 112 | 0.884 | 0.795 | 0.743 | ||

| Fan (29) | 2009 | Pathological | 489 | 0.862 | – | 0.792 | 394 | 0.866 | – | 0.788 | ||

| Muscari (30) | 2009 | Radiological | 75 | – | – | 0.780 | 73 | – | – | 0.790 | ||

| Vakili (31) | 2009 | Pathological | Living donor | 26 | – | – | 0.832 | 21 | – | – | 0.871 | |

| Wang (32) | 2009 | Pathological | 110 | 0.981 | 0.799 | – | 75 | 0.986 | 0.861 | – | ||

| Piardi (33) | 2011 | Pathological | 134 | 0.900 | 0.830 | 0.760 | 106 | 0.900 | 0.850 | 0.770 | ||

| Unek (34) | 2011 | Pathological | 41 | 0.903 | 0.819 | 0.819 | 34 | 0.912 | 0.877 | 0.877 | ||

| Choi (35) | 2013 | Pathological | Living donor | 150 | – | 0.822 | 0.813 | 130 | – | 0.808 | 0.798 | |

| Kaido (36) | 2013 | Radiological | Living donor | 127 | – | – | 0.770 | 118 | – | – | 0.760 | |

| Bonadio (37) | 2015 | Pathological | 43 | – | – | 0.740 | 39 | – | – | 0.740 | ||

| Xu (38) | 2015 | Radiological | 3,049 | 0.906 | 0.804 | 0.759 | 2,626 | 0.909 | 0.814 | 0.770 | ||

A total of 21 retrospective studies with a mean follow-up of 19.6 to 96 months. Radiological and pathological criteria were used for the analysis of tumor size, and most of the studies used deceased donors.

Table 2. Individual results of selected papers.

| Author | Year | Criterion | Observation | Survival rate—UCSF | Survival rate—Milan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | |||||

| Yao (18) | 2002 | Pathological | 60 | 0.900 | 0.820 | 0.750 | 46 | 0.910 | 0.810 | 0.720 | ||

| Leung (19) | 2004 | Radiological | 81 | 0.858 | 0.648 | 0.519 | 74 | 0.859 | 0.637 | 0.509 | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | 46 | – | 0.881 | – | 42 | – | 0.899 | – | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | Living donor | 167 | – | 0.906 | – | 151 | – | 0.914 | – | |

| Decaens (21) | 2006 | Pathological | 223 | – | – | 0.695 | 184 | - | - | 0.704 | ||

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Pathological | Living donor | 50 | – | 0.760 | – | 43 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Radiological | Living donor | 41 | – | 0.780 | – | 37 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Kwon (23) | 2007 | Pathological | Living donor | 89 | – | – | 0.800 | 84 | – | – | 0.800 | |

| Lo (24) | 2007 | Pathological | 51 | 0.980 | 0.880 | 0.720 | 44 | 0.980 | 0.890 | 0.710 | ||

| Parfitt (25) | 2007 | Pathological | 59 | – | 0.771 | 0.726 | 50 | – | 0.830 | 0.830 | ||

| Lee (26) | 2008 | Pathological | Living donor | 174 | 0.874 | 0.800 | 0.759 | 164 | 0.866 | 0.794 | 0.760 | |

| Toso (27) | 2008 | Pathological | 193 | – | – | 0.800 | 157 | – | – | 0.820 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Pathological | 132 | 0.864 | 0.796 | 0.767 | 117 | 0.872 | 0.803 | 0.771 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Radiological | 126 | 0.873 | 0.786 | 0.731 | 112 | 0.884 | 0.795 | 0.743 | ||

| Fan (29) | 2009 | Pathological | 489 | 0.862 | – | 0.792 | 394 | 0.866 | – | 0.788 | ||

| Muscari (30) | 2009 | Radiological | 75 | – | – | 0.780 | 73 | – | – | 0.790 | ||

| Vakili (31) | 2009 | Pathological | Living donor | 26 | – | – | 0.832 | 21 | – | – | 0.871 | |

| Wang (32) | 2009 | Pathological | 110 | 0.981 | 0.799 | – | 75 | 0.986 | 0,861 | – | ||

| Piardi (33) | 2011 | Pathological | 134 | 0.900 | 0.830 | 0.760 | 106 | 0.900 | 0.850 | 0.770 | ||

| Unek (34) | 2011 | Pathological | 41 | 0.903 | 0.819 | 0.819 | 34 | 0.912 | 0.877 | 0.877 | ||

| Choi (35) | 2013 | Pathological | Living donor | 150 | – | 0.822 | 0.813 | 130 | – | 0.808 | 0.798 | |

| Kaido (36) | 2013 | Radiological | Living donor | 127 | – | – | 0.770 | 118 | – | – | 0.760 | |

| Bonadio (37) | 2015 | Pathological | 43 | – | – | 0.740 | 39 | – | – | 0.740 | ||

| Xu (38) | 2015 | Radiological | 3,049 | 0.906 | 0.804 | 0.759 | 2,626 | 0.909 | 0.814 | 0.770 | ||

Individual survival rates at 1, 3 and 5 years.

Bias

The selected studies presented some differences in relation to the method used to evaluate the tumor (radiological × pathological) and donor type (deceased × living); hence, analysis by subgroups helped to reduce the influence of these biases using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for each article.

Most of the studies (seventeen) did not present the number of patients in the Kaplan-Meier curve for each follow-up interval; however, for such articles, we used an estimate, described above, which reduced the influence of this bias on the final result, as demonstrated by Vale et al. in 2002 (17). No study was left out from the funnel plot; thus, there were no exclusion for publication bias.

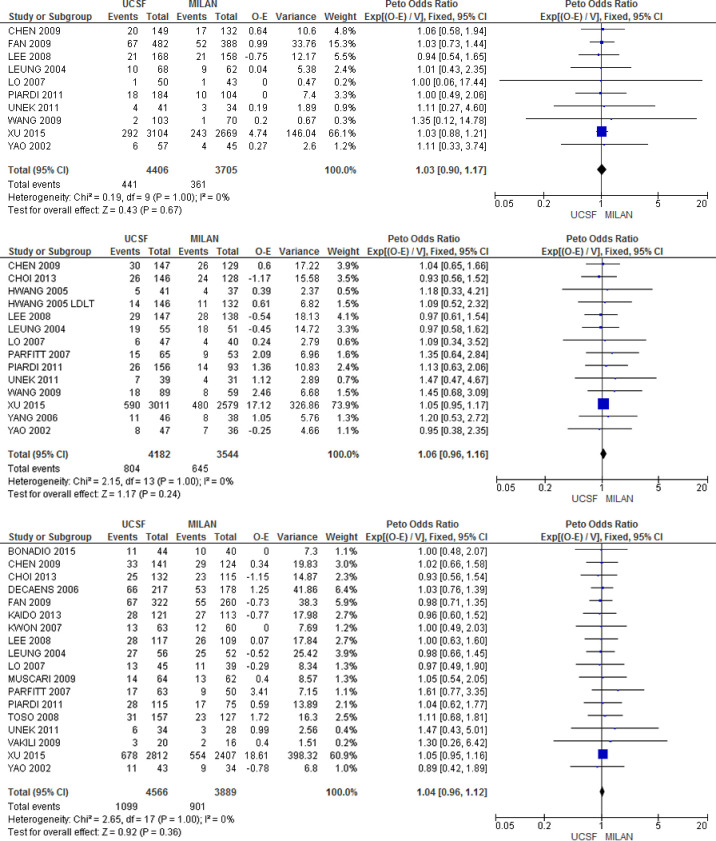

Global survival rate between the Milan and UCSF criteria

There was no statistically significant difference between the two criteria in overall survival at 1, 3 and 5 years of follow-up shown by estimated HRs of 1.03 [0.90, 1.17], 1.06 [0.96, 1.16] and 1.04 [0.96, 1.12], respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Comparison of global survival rates. The analysis of the overall survival rate between the different criteria (Milan and UCSF) did not identify significant differences at 1, 3 or 5 years in the included studies.

Overall survival rate by different subgroups comparing the Milan and UCSF criteria

When we analyzed survival by donor type (deceased × living), we did not observe a significant difference in survival rates at 1, 3 or 5 years in any of the two groups, with HRs of 1.03 [0.90, 1.18] at 1 year, 1.06 [0.96, 1.17] at 3 years and 1.04 [0.96, 1.13] at 5 years in the deceased donor transplant group. In the living donor group, the HRs were 0.94 [0.54, 1.65], 1.00 [0.75, 1.33] and 0.98 [0.76, 1.26] at 1, 3 and 5 years, respectively.

In the analysis according to the different populations (eastern × western), there was also no significant difference, with HRs of 1.03 [0.89, 1.18] and 1.04 [0.72, 1.51] at 1 year, 1.05 [0.95, 1.16] and 1.08 [0.83, 1.40] at 3 years, and 1.03 [0.95, 1.13] and 1.05 [0.90, 1.23] at 5 years, respectively.

Finally, comparing survival rates using the parameters adopted in the measurement of tumor size (pathological and radiological) we obtained HRs of 1.02 [0.81, 1.29] and 1.04 [0.89, 1.21] at 1 year, 1.08 [0.89, 1.32] and 1.05 [0.95, 1.16], and 1.03 [0.90, 1.18] and 1.04 [0.95, 1.14] at 5 years, respectively.

In summary, no significant difference was found in among the subgroups studied (Table 3).

Table 3. Results by different subgroups.

| Author | Year | Criterion | Observation | Survival rate—UCSF | Survival rate—Milan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | N | 1 year | 3 years | 5 years | |||||

| Yao (18) | 2002 | Pathological | 60 | 0.900 | 0.820 | 0.750 | 46 | 0.910 | 0.810 | 0.720 | ||

| Leung (19) | 2004 | Radiological | 81 | 0.858 | 0.648 | 0.519 | 74 | 0.859 | 0.637 | 0.509 | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | 46 | – | 0.881 | – | 42 | – | 0.899 | – | ||

| Hwang (20) | 2005 | Pathological | Living donor | 167 | – | 0.906 | – | 151 | – | 0.914 | – | |

| Decaens (21) | 2006 | Pathological | 223 | – | – | 0.695 | 184 | – | – | 0,704 | ||

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Pathological | Living donor | 50 | – | 0.760 | – | 43 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Yang (22) | 2006 | Radiological | Living donor | 41 | – | 0.780 | – | 37 | – | 0.800 | – | |

| Kwon (23) | 2007 | Pathological | Living donor | 89 | – | – | 0.800 | 84 | – | – | 0.800 | |

| Lo (24) | 2007 | Pathological | 51 | 0.980 | 0.880 | 0.720 | 44 | 0.980 | 0.890 | 0.710 | ||

| Parfitt (25) | 2007 | Pathological | 59 | – | 0.771 | 0.726 | 50 | – | 0.830 | 0.830 | ||

| Lee (26) | 2008 | Pathological | Living donor | 174 | 0.874 | 0.800 | 0.759 | 164 | 0.866 | 0.794 | 0.760 | |

| Toso (27) | 2008 | Pathological | 193 | – | – | 0.800 | 157 | – | – | 0.820 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Pathological | 132 | 0.864 | 0.796 | 0.767 | 117 | 0.872 | 0.803 | 0.771 | ||

| Chen (28) | 2009 | Radiological | 126 | 0.873 | 0.786 | 0.731 | 112 | 0.884 | 0.795 | 0.743 | ||

| Fan (29) | 2009 | Pathological | 489 | 0.862 | – | 0.792 | 394 | 0.866 | – | 0.788 | ||

| Muscari (30) | 2009 | Radiological | 75 | – | – | 0.780 | 73 | – | – | 0.790 | ||

| Vakili (31) | 2009 | Pathological | Living donor | 26 | – | – | 0.832 | 21 | – | – | 0.871 | |

| Wang (32) | 2009 | Pathological | 110 | 0.981 | 0.799 | – | 75 | 0.986 | 0.861 | – | ||

| Piardi (33) | 2011 | Pathological | 134 | 0.900 | 0.830 | 0.760 | 106 | 0.900 | 0.850 | 0.770 | ||

| Unek (34) | 2011 | Pathological | 41 | 0.903 | 0.819 | 0.819 | 34 | 0.912 | 0.877 | 0.877 | ||

| Choi (35) | 2013 | Pathological | Living donor | 150 | – | 0.822 | 0.813 | 130 | – | 0.808 | 0.798 | |

| Kaido (36) | 2013 | Radiological | Living donor | 127 | – | – | 0.770 | 118 | – | – | 0.760 | |

| Bonadio (37) | 2015 | Pathological | 43 | – | – | 0.740 | 39 | – | – | 0.740 | ||

| Xu (38) | 2015 | Radiological | 3,049 | 0.906 | 0.804 | 0.759 | 2,626 | 0.909 | 0.814 | 0.770 | ||

Final analysis of the different subgroups (donor type, population and tumor evaluation criteria did not show a significant difference and indicated the lack of possible selection biases).

Discussion

The treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma has evolved considerably in recent decades. Patients with HCC may benefit from options that improve their survival rates regardless of the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis (39).

Liver transplantation is still the best option for the definitive treatment of HCC in patients with impaired liver functions. However, as previously mentioned, an insufficient supply for demand obliges us to adopt criteria for the selection of patients who are candidates for transplantation. Therefore, many variables should be examined to determine the indication for transplantation. The balance between restriction and results is the key point for the definition of indication criteria for transplantation, which benefits a large number of cirrhotic patients without compromising the final outcomes. In this study, we analyzed only one of these indications: the relation between the Milan or UCSF criteria for tumor staging.

More restrictive allocation models theoretically guarantee the best long-term results but limit patients eligible for transplantation by preventing an acceptable survival rate. The inclusion of patients on a transplant list based on HCC was historically questioned with regard to the benefit of transplantation versus the low supply of viable grafts and donors. For many years after the introduction of the MELD for patient stratification, this special scoring regimen was questioned as a method that favored patient with HCC. However, it is unknown whether there is a good classification method that is equally effective for patients with and without HCC. Defining whether a staging criteria such as Milan and UCSF are equivalent to predict survival would be only the first step.

Our results from the quantitative analysis did not show a statistically significant difference between these two criteria, in any time frame or in any subgroup, for both deceased and living donors. There was a balance between the number of eastern versus western articles, but the eastern population was approximately 4 times larger, mainly due to the article by Xu et al. 2015 (38), which used a large Chinese national database. Concerning the method used by each study regarding the use of a radiological or pathological model to stratify tumor sizes, no influence on our final results was observed, since there was no significant difference between these two specific groups.

In relation to other comparative studies regarding these criteria, Patel et al. in 2012 (40) compared these criteria using a large multi-institutional cohort and identified no difference in survival rates between these groups. This study was not included in our meta-analysis due to lack of data needed for our statistical analysis. However, its methodology, using large databases, provided us with great information about liver transplantation and indication criteria, as well as the results of our study, since a prospective and randomized study on the subject is practically unfeasible due to ethical and legal issues.

Currently, we know that other factors affect the evolution of the tumors, including vascular and neural invasion and biomarkers, such as alpha fetoprotein (22,41). The identification of new targets and predictors of post-transplantation prognosis through a molecular profile is needed. This approach may identify new therapeutic strategies and perhaps be used for indication of transplantation. The identification of circulating tumor products (liquid biopsy) may overcome these limitations, but this strategy is still being investigated (42).

What we know for sure is that the prevention of the accumulation of risk factors for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma is the best strategy to reduce mortality. It is predicted that the reduction in hepatitis C virus infection by the introduction of effective antiretroviral agents will have an impact on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Initiatives such as mass vaccination for hepatitis B virus, promotion of healthy lifestyles, including a decrease in alcohol abuse and prevention of metabolic syndrome, will also impact the incidence of HCC (43).

In addition, there are promising new treatment strategies, such as new immunotherapies, which are being studied. For example, nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) immune checkpoint inhibitor, demonstrated antitumor potential with a response rate of 15–20% (44,45).

In summary, given the complexity of the disease and the large number of potentially useful treatments, hepatocellular carcinoma patients must be examined by teams specialized in the subject.

Conclusions

Both the Milan and UCSF criteria are equivalent in terms of 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates, leading us to believe that the use of a less restrictive method would not result in a great loss in the final overall survival rate and would benefit a greater number of patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Statement: This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the non-commercial replication and distribution of the article with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are made and the original work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Footnotes

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was a free submission to the journal. The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/tgh.2020.01.06). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Wallace MC, Preen D, Jeffrey GP, et al. The evolving epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: a global perspective. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;9:765-79. 10.1586/17474124.2015.1028363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2012;142:1264-73.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyson J, Jaques B, Chattopadyhay D, et al. Hepatocellular cancer: the impact of obesity, type 2 diabetes and a multidisciplinary team. J Hepatol 2014;60:110-7. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, et al. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:301-8.e1. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forner A, D.az-Gonzalez A, Liccioni A, et al. Prognosis prediction and staging. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2014;28:855-65. 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Llovet JM, Brú C, Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis 1999;19:329-38. 10.1055/s-2007-1007122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yau T, Tang VY, Yao TJ, et al. Development of Hong Kong Liver Cancer staging system with treatment stratification for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 2014;146:1691-700.e3. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 1996;334:693-9. 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Omata M, Lesmana LA, Tateishi R, et al. Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver consensus recommendations on hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Int 2010;4:439-74. 10.1007/s12072-010-9165-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruix J, Sherman M, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53:1020-2. 10.1002/hep.24199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Association For The Study Of The Liver. European Organisation For Research And Treatment Of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012;56:908-43. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazzaferro V, Bhoori S, Sposito C, et al. Milan criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis of 15 years of experience. Liver Transpl 2011;17 Suppl 2:S44-57. 10.1002/lt.22365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao FY. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology 2001;33:1394-403. 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merion RM, Wolfe RA, Dykstra DM, et al. Longitudinal assessment of mortality risk among candidates for liver transplantation. Liver Transpl 2003;9:12-8. 10.1053/jlts.2003.50009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y, Zeng T. Response to: Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2013;14:391. 10.1186/1745-6215-14-391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vale CL, Tierney JF, Stewart LA. Effects of adjusting for censoring on meta-analyses of time-to-event outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:107-11. 10.1093/ije/31.1.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: comparison of the proposed UCSF criteria with the Milan criteria and the Pittsburgh modified TNM criteria. Liver Transpl 2002;8:765-74. 10.1053/jlts.2002.34892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung JY, Zhu AX, Gordon FD, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes for early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results of a multicenter study. Liver Transpl 2004;10:1343-54. 10.1002/lt.20311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hwang S, Lee SG, Joh JW, et al. Liver transplantation for adult patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Korea: comparison between cadaveric donor and living donor liver transplantations. Liver Transpl 2005;11:1265-72. 10.1002/lt.20549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decaens T, Roudot-Thoraval F, Hadni-Bresson S, et al. Impact of UCSF criteria according to pre- and post-OLT tumor features: analysis of 479 patients listed for HCC with a short waiting time. Liver Transpl 2006;12:1761-9. 10.1002/lt.20884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang SH, Suh KS, Lee HW, et al. A revised scoring system utilizing serum alphafetoprotein levels to expand candidates for living donor transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2007;141:598-609. 10.1016/j.surg.2006.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kwon CH, Kim DJ, Han YS, et al. HCC in living donor liver transplantation: can we expand the Milan criteria? Dig Dis 2007;25:313-9. 10.1159/000106911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lo CM, Fan ST, Liu CL, et al. Living donor versus deceased donor liver transplantation for early irresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2007;94:78-86. 10.1002/bjs.5528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Parfitt JR, Marotta P, Alghamdi M, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transplantation: use of a pathological score on explanted livers to predict recurrence. Liver Transpl 2007;13:543-51. 10.1002/lt.21078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SG, Hwang S, Moon DB, et al. Expanded indication criteria of living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma at one large-volume center. Liver Transpl 2008;14:935-45. 10.1002/lt.21445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Toso C, Trotter J, Wei A, et al. Total tumor volume predicts risk of recurrence following liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2008;14:1107-15. 10.1002/lt.21484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen JW, Kow L, Verran DJ, et al. Poorer survival in patients whose explanted hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) exceeds Milan or UCSF Criteria. An analysis of liver transplantation in HCC in Australia and New Zealand. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:81-9. 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2009.00022.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fan J, Yang GS, Fu ZR, et al. Liver transplantation outcomes in 1,078 hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a multi-center experience in Shanghai, China. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009;135:1403-12. 10.1007/s00432-009-0584-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muscari F, Foppa B, Kamar N, et al. Liberal selection criteria for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2009;96:785-91. 10.1002/bjs.6619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vakili K, Pomposelli JJ, Cheah YL, et al. Living donor liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Increased recurrence but improved survival. Liver Transpl 2009;15:1861-6. 10.1002/lt.21940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang ZX, Song SH, Teng F, et al. A single-center retrospective analysis of liver transplantation on 255 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Transplant 2010;24:752-7. 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2009.01172.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Piardi T, Gheza F, Ellero B, et al. Number and tumor size are not sufficient criteria to select patients for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2012;19:2020-6. 10.1245/s10434-011-2170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Unek T, Karademir S, Arslan NC, et al. Comparison of Milan and UCSF criteria for liver transplantation to treat hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:4206-12. 10.3748/wjg.v17.i37.4206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi HJ, Kim DG, Na GH, et al. Clinical outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after living-donor liver transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:4737-44. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i29.4737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaido T, Ogawa K, Mori A, et al. Usefulness of the Kyoto criteria as expanded selection criteria for liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Surgery 2013;154:1053-60. 10.1016/j.surg.2013.04.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bonadio I, Colle I, Geerts A, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma comparing the Milan, UCSF, and Asan criteria: long-term follow-up of a Western single institutional experience. Clin Transplant 2015;29:425-33. 10.1111/ctr.12534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu X, Lu D, Ling Q, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria. Gut 2016;65:1035-41. 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yegin EG, Oymaci E, Karatay E, et al. Progress in surgical and nonsurgical approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma treatment. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2016;15:234-56. 10.1016/S1499-3872(16)60097-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patel SS, Arrington AK, McKenzie S, et al. Milan Criteria and UCSF Criteria: A Preliminary Comparative Study of Liver Transplantation Outcomes in the United States. Int J Hepatol 2012;2012:253517. 10.1155/2012/253517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berry K, Ioannou GN. Serum alpha-fetoprotein level independently predicts posttransplant survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl 2013;19:634-45. 10.1002/lt.23652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mader S, Pantel K. Liquid Biopsy: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Oncol Res Treat 2017;40:404-8. 10.1159/000478018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lodato F, Mazzella G, Festi D, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma prevention: a worldwide emergence between the opulence of developed countries and the economic constraints of developing nations. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12:7239-49. 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prieto J, Melero I, Sangro B. Immunological landscape and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:681-700. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 2017;389:2492-502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]