Abstract

Advance care planning is under-used among Black Americans, often because of experiences of racism in the health care system, resulting in a lower quality of care at the end of life. African American faith communities are trusted institutions where such sensitive conversations may take place safely. Our search of the literature identified five articles describing faith-based advance care planning education initiatives for Black Americans that have been implemented in local communities. We conducted a content analysis to identify key themes related to the success of a program’s implementation and sustainability. Our analysis showed that successful implementation of advance care planning programs in Black American congregations reflected themes of building capacity, using existing ministries, involving faith leadership, exhibiting cultural competency, preserving a spiritual/Biblical context, addressing health disparities, building trust, selectively using technology, and fostering sustainability. We then evaluated five sets of well-known advance care planning education program materials that are frequently used by pastors, family caregivers, nurse’s aides, nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains from a variety of religious traditions. We suggest ways these materials may be tailored specifically for Black American faith communities, based on the key themes identified in the literature on local faith-based advance care planning initiatives for Black churches. Overall, the goal is to achieve better alignment of advance care planning education materials with the African American faith community and to increase implementation and success of advance care planning education initiatives for all groups.

Keywords: advance care planning, faith-based program, health disparities, health education

Introduction

The National Academy of Medicine recognizes advance care planning (ACP) as a key facilitator of high-quality end-of-life (EOL) care.1 ACP refers to a health care decision process that includes discussing and planning care for the end of life in the event one is unable to communicate care preferences at the time.2 Informal ACP may involve a conversation with a family member or loved one about EOL care preferences. Formal ACP includes completion of legal documents, such as an advance directive (AD), in which an individual identifies preferences for EOL treatments and designates a durable power of attorney for health care.2 ACP is positively associated with a better quality death,3,4 higher rates of hospice use,5,6 lower medical expenditures,6,7 and less emotional distress for bereaved family members.4

Patients who participate in ACP are more likely to receive care that is less aggressive, to enroll in hospice care, and to experience greater satisfaction with care.3,7,8 Yet studies show that Black Americans are less likely to participate in ACP than non-Hispanic Whites.9–12 Evidence suggests numerous reasons for this disparity, including distrust resulting from experiences of discrimination in a medical setting,9,13–18 cultural values and spiritual beliefs that conflict with ACP,9,11,15,17,19–22 and lack of understanding or clarity regarding ACP.9,13,22

There is a need to present the concept and practices of ACP in clear, innovative, culturally relevant ways to reach underserved Black communities. Faith organizations offer an avenue for developing and disseminating ACP education within the Black community. Christian churches in the United States serving predominantly African American congregations are the African Methodist Episcopal and African Methodist Episcopal Zion Churches, the National Baptist Convention of America, and the Church of God in Christ, but also there are Black congregations within the largely White Southern Baptist Convention, and mainline Protestant and Roman Catholic churches; together they share an identity as the Black Church.23 The Black Church has long been a source of empowerment, social change, and a central organization for social justice movements, with pastors and other faith leaders playing respected and influential roles in many areas of community life,24 including EOL care.25 Faith-based, community-engaged ACP education programs have the potential to align these health care priorities with the faith organization’s belief system and may prove successful in increasing adoption of ACP by Black Americans.

This article seeks to identify the factors that could influence uptake of ACP in primarily Black faith organizations where these resources are under-used. In this article, we briefly review what is known about the WHY behind the pattern of underuse. We then identify articles that describe and evaluate ACP education programs that have been developed for Black Churches in local contexts and conduct a thematic content analysis on the characteristics of these programs. We then apply these themes to a set of programs developed nationally for increasing ACP in faith communities in general, to make them more aligned with the specific concerns and beliefs of Black Americans.

Background

The underuse of ACP by Black Americans has been a concern to bioethicists, palliative care providers, and others dedicated to improving care for patients at the end of life. Dozens of studies have been conducted to better understand factors producing this disparity between Black and non-Hispanic White Americans. This pattern is strongly related to other types of racial health disparities. In a special issue of the Journal of Palliative Medicine (2016) devoted to palliative and EOL care for African Americans, the editor writes, ‘the first step is recognizing, acknowledging, and respecting the inequity, disrespect, and disregard our African Americans patients have experienced’26 (p. 124).

In a systematic integrated review in that special issue of the factors impacting ACP use among African Americans, Sanders and colleagues27 identified 38 quantitative and 14 qualitative studies, most of which focused specifically on racial differences in the completion of ADs, living wills, do-not-resuscitate orders, health care proxies, and durable powers of attorney for health care. Quantitative studies were observational, with the majority finding that African Americans preferred more life-sustaining treatment (LST) and were less likely than Whites to undertake ACP. Qualitative studies, usually of focus groups, had their quoted material analyzed for themes. The authors note that ‘Religion was almost universally a source of both strength and motivation to pursue LST (life-sustaining treatment)’; other prominent themes more common to Blacks than Whites were distrust of medical care and discomfort discussing death27 (p. 218). The authors conclude that the history of systemic racism in the United States has resulted in these patterns of mistrust and that considerable efforts to improve communication are required to improve this disparity in the quality of care. More recent studies support these findings. Rhodes and colleagues22 conducted focus groups and interviews with African American health care providers, clergy, patients, and community members; along with lack of knowledge and medical mistrust, religion was again perceived as a barrier, in that use of ACP such as ADs ‘… takes something away from God’ (p. 512). Overall, there is great consistency in the literature on the racial disparities in ACP, and religion is central to these discussions.

There is both a need and a desire for church-based EOL care education. Hendricks Sloan and colleagues conducted a cross-sectional survey of parishioners at two large Black Baptist churches to determine parishioner beliefs about EOL care and potential desire for faith-based ACP. The authors found that the majority (93%) of African American parishioners would welcome a church-based program focused on improving EOL care education.28

A parallel study to our own is that of Campbell and colleagues,29 who conducted a literature review of faith-based health initiatives and identified 13 studies representing a wide range of health promotion programs including nutrition, physical activity, smoking cessation, and screening in primarily African American churches. Based on this review, the authors identify overarching themes that lend to successful church-based health promotion. Our aim for this study is to replicate this approach for initiatives focused specifically on ACP and to directly apply our findings to frequently used faith-based ACP programs and materials.

Methods

Data collection

We conducted a literature search to identify peer-reviewed empirical papers on ACP education programs in Black faith institutions using the electronic databases ProQuest and Google Scholar. We used the following keywords: ‘health education’, ‘African American’, ‘faith-based’, ‘education program’, ‘community-based’, ‘race’, and ‘church’. We included studies written in English and published between 2000 and 2019. The initial search yielded 497 ProQuest and 644 Google Scholar results. We then removed duplicates and eliminated dissertations, chapters, and other non-peer-reviewed papers. This resulted in a set of 65 papers for which we retrieved full texts, applying the following criteria for inclusion in the final sample:

Studies of faith-based programs for ACP education initiatives;

Studies that included African American faith institutions in the United States;

Studies that addressed program success and barriers.

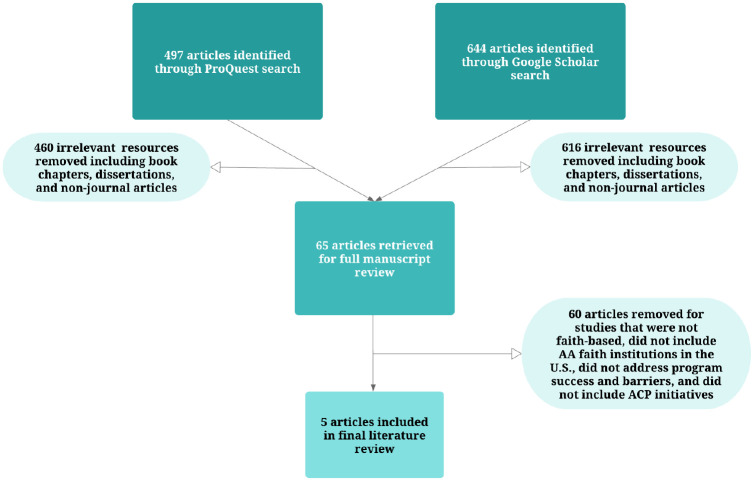

After applying the inclusion criteria, we identified five articles for the literature review. See Figure 1 for a flow chart of the literature review process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature review process.

Data analysis

To identify the key mechanisms that facilitate ACP uptake and sustainability within Black faith organizations, we identified and hand-coded key themes in these studies. We first compiled data as direct text and associated written memos using tables in Microsoft Word. For the thematic analysis, we coded in an iterative process in which themes were initially identified using an inductive process and subsequently re-coded as new themes emerged from the data. Using open and axial coding allowed us to flesh out conceptual dimensions and to discover and account for patterns and variation in the data.30 Selective coding then allowed us to winnow out emerging second-order themes rooted in the data. Henceforth, we refer to the results of axial and selective coding as first-order and second-order themes, respectively.

Findings from review of studies: derivation of themes

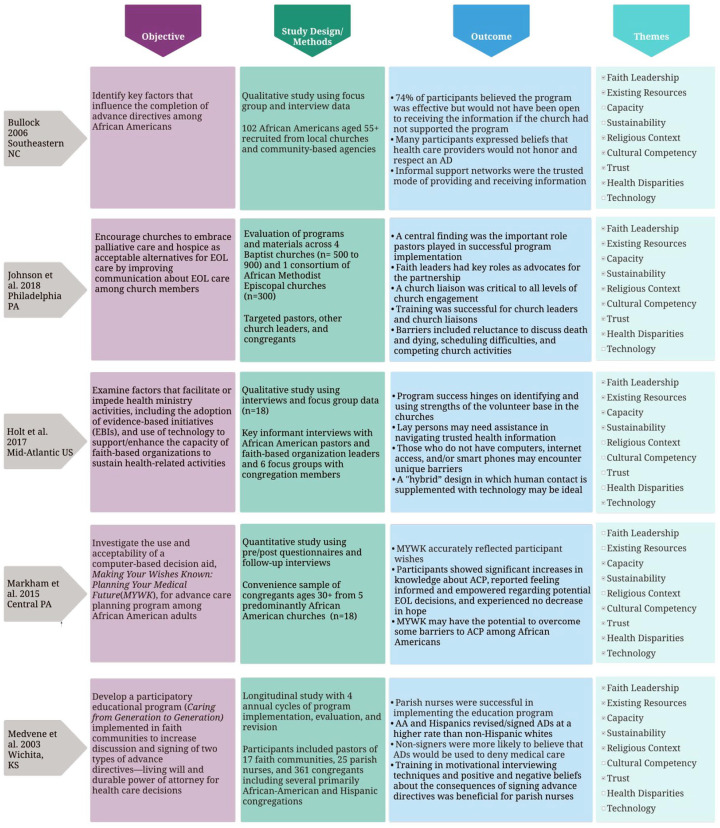

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the five studies we identified. They were published from 2003 to 2018. The ACP education programs reported on were implemented in African American faith communities in various parts of the United States, in various Christian, primarily Protestant, denominations. The content of the programs was created by local teams committed to increasing the use of ACP in these communities. The studies reported positive responses to the programs, including completion of ADs by substantial numbers of those participating.

Table 1.

Five studies of advance care planning programs in Black faith communities.

|

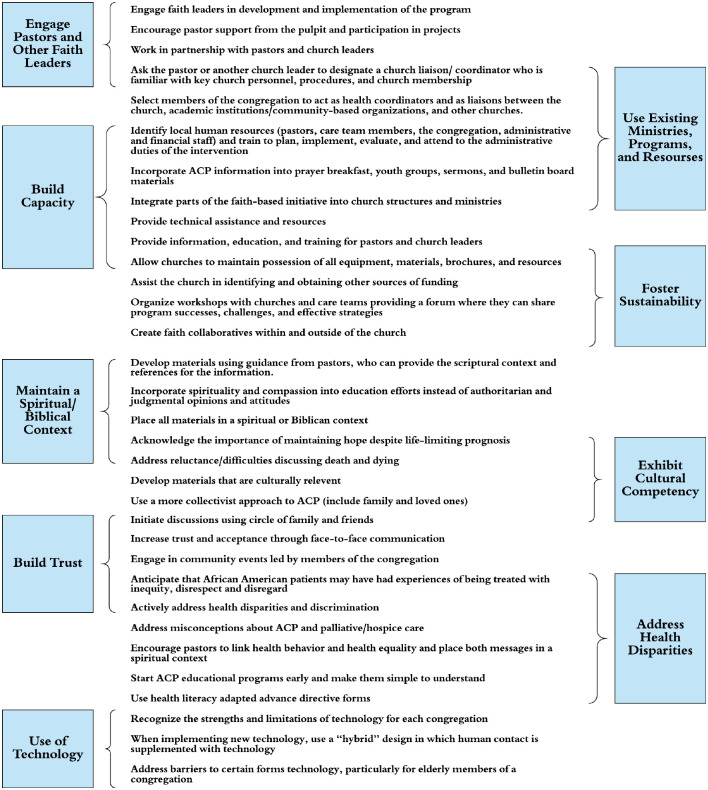

We identified 33 first-order themes as important to successful implementation of ACP programs in Black faith institutions, either as facilitating characteristics or as barriers to overcome. Many of these were related to each other and selective coding resulted in nine second-order themes that include building capacity within the faith-based organization, using existing ministries to establish ACP initiatives, encouraging continuous involvement of pastors and lay leaders, exhibiting cultural competency, working within a spiritual/Biblical context, addressing health disparities, building trust, using technology in a way that makes sense for members of the faith community, and fostering sustainability throughout implementation of initiatives. Barriers to successful ACP program implementation include organizational challenges, reluctance to discuss death and dying, lack of information or clarity regarding ACP, lack of trust and experiences of discrimination, and values and beliefs that conflict with ACP.

Many of the second-order themes are related to each other but also distinct. We have organized them visually in Figure 2 in a manner that represents their overlapping content. Engaging faith leadership in ACP education initiatives is related to using existing resources, for example, and use of existing ministries, programs, and resources helps to build capacity. In the final column of Table 1, we have indicated which themes were present in the reports of each of the five ACP programs. As can be seen, no single theme was present in the accounts of all programs, but several, including engaging faith leadership, building capacity, and emphasizing the Biblical/spiritual context of the material, were present for most. In what follows we describe these overlapping themes and the studies that exemplified them.

Figure 2.

Characteristics of faith-based ACP programs.

Build capacity and foster sustainability: seek support from faith leadership, invest in existing resources, and provide technical assistance

Religious community leaders serve as the key interface between religious organizations and public health professionals and agencies. Because faith leaders are familiar with key personnel, procedures, and lay members of the religious organization, they can help the initiative get off the ground and encourage wider member participation and commitment. Partnering with five primarily African American churches in the Philadelphia region, Johnson and colleagues31 worked with faith communities to develop a leadership education program for pastors, ministry leaders, and other church leaders; establish a training program for lay companions; and distribute education materials about EOL decision-making. Using a church-based health promotion model, Johnson and colleagues found that head pastors were critical for project start-up and implementation, and the most successful lay-companion training program was headed by a pastor who regularly attended leadership education and lay-companion training sessions.

According to Johnson and colleagues, church leaders were important because they represented the traditional organizational structure and authority of the churches, and their advocacy and endorsement was influential in garnering acceptance by congregants. Church leaders helped dispel dissent among congregation members and promoted congregational buy-in by presenting ACP program information to their congregants during church services, introducing members of the academic team to key leaders in the church, scheduling EOL decision-making presentations during church services, authorizing messaging in announcements and church bulletins, encouraging congregants to volunteer for lay-companion training, and participating in general problem solving.31

In addition to support and guidance from pastors and other faith leaders, investment in the existing ministries, programs, and resources of the faith organization may help build capacity and ensure long-term sustainability of faith-based ACP programs. Evaluations of faith-based health education initiatives have shown that using and enhancing existing resources is overwhelmingly preferred by members of faith organizations to initiatives delivered by outside experts.29,32 This pattern holds true for ACP education initiatives. Successful implementation and long-term sustainability of faith-based ACP education hinges on investment in members of the faith organization. Johnson and colleagues31 found that embracing the traditions, structures, and policies of the church lends to successful implementation and sustainability of EOL education. The research team judged success in terms of capacity to create and maintain all levels of the program. The two most successful church/public health partnerships designated church liaisons to serve as ambassadors, coordinators, and planners of the initiative; trained church leadership and existing ministry to advocate for the partnership; trained lay members to act as companions to church members with life-limiting illness; and engaged the general congregation via presentations on the overall project.31

ACP education efforts can capitalize on the strengths of the volunteer base in the churches, who are often women and those who have a previous health care background.33 Allying with existing care teams and ministries also provides a channel through which members of the religious community and public health professionals can share knowledge and work together within a trustworthy and familiar environment. In a pilot study to promote ACP in primarily African American faith organizations, Bullock9 collected interview and focus group data from 102 African Americans aged 55 years or older from churches in southeastern North Carolina. Interviewees all participated in an ACP education program developed by a collaboration between Truth in Youth and Family Services (TIY) and local churches. Bullock found that while 74% of participants believed the program was effective, most participants said they would not have been amenable to receiving the information or talking openly about EOL decisions if the church had not supported the program.9

Evidence shows there is a need for technical assistance in implementing and sustaining faith-based ACP programs.33 Providing technical assistance—in the form of workshops, education, and training—increases the capacity of faith-based organizations to administer sustainable efforts within their communities.31 Regular workshops can provide a forum in which members of the faith community can share intervention successes, challenges, and effective strategies. Johnson and colleagues31 found that during monthly support-group meetings, lay companions shared visit experiences and received feedback and support from other attendees.

Faith leaders often have high interest in promoting the health of their memberships but may lack the specific knowledge as to the best way to achieve it.34 In a longitudinal study with four annual cycles of ACP program implementation, evaluation, and revision across 17 faith communities, Medvene and colleagues34 found that while parish nurses wanted to work with congregants to increase knowledge about and engagement in ACP, they lacked the expertise. Training parish nurses in motivational interviewing techniques and information concerning positive and negative beliefs about the consequences of signing ADs helped nurses overcome lack of ACP expertise and successfully facilitate ACP discussions.

Offering formal training to faith leaders and lay members provides these members with the tools to successfully organize and manage the initiative and to act as liaisons between the religious organization, academic institution, public health agency, and the larger faith community.31,33 Identifying existing human resources within the congregation and providing training in planning, implementation, evaluation, and administrative duties embeds the skills and knowledge generated through partnerships between religious organizations and academic/public health institutions within the church community and fosters long-term sustainability.35 In addition, fostering a sense of ownership of the faith-based health initiative ensures wider program participation and distribution.29

Potential challenges to program implementation and sustainability include scheduling conflicts and time constraints.33 It may be difficult to schedule workshops or meetings when the church’s calendar is full. Also, competing priorities may reduce participation and pose a challenge to maintaining a sufficient volunteer base. Interview and focus group data from faith leaders and congregants across six churches in the Mid-Atlantic United States revealed that leaders in the faith organization may find time constraints particularly challenging.33 Church leaders often commit to multiple initiatives, and burnout was cited as a common problem. Diffusing responsibility across lay members of the church who are strongly committed to the initiative can help reduce burnout and ensure program sustainability.

Cultural and spiritual concordance

At its inception, the ACP education initiative should take into account the mission, belief system, values, and cultural norms of the faith organization. Public health professionals and agencies working with religious organizations must demonstrate respect for the organization’s values and customs and take care not to dismiss or disregard the importance of spiritual beliefs. Incorporating spirituality and compassion into education efforts and respecting these core values of the organization can help foster trust between health professionals, agencies, and faith communities.9,32

Focus group and interview data suggest that faith and spirituality are relevant factors when making EOL care decisions.9 One way to ensure that the spiritual and cultural values of the faith organization guide ACP program design and implementation is by involving faith leaders in the design of all materials. Faith leaders can provide scriptural context and references for all program information.31 Evidence suggests that lay members and leadership alike respond more favorably to information that does not seek to change core beliefs, and members of the faith-based organization may respond better to messages that include spiritual and Biblical references rather than biomedical expert recommendations.29,36

Program messages and materials should also be presented in a culturally congruent context as many Black Americans may have values and beliefs that conflict with ACP.9 A “good death”—defined in the research literature as a death that is free from avoidable distress and suffering for patients, families, and caregivers—may not find congruence with the beliefs and values of Black Americans. This conceptualization of death may conflict with cultural beliefs and attitudes about fighting to the end, not giving up hope, believing in a higher power, and not planning for the unknown.9

In addition, an individualistic approach to ACP may not align with values of many older Black Americans who value a more collectivist approach to EOL decision-making that includes family and other loved ones in the decision-making process.9,37,38 Many Black Americans prefer an informed, family-directed approach to EOL care.39 Black Americans, in contrast to Whites, are less likely to engage in written forms of ACP and more likely to rely on a family-centered approach to planning for the end of life.20 Because Black Americans culturally value informal support networks, health care professionals should be encouraged to involve community leaders, families, and friends in communication about ACP.9

Address racialized health inequities in order to build trust: do not ignore the pernicious effects of past and present racism

Leaders within the faith organization can link health disparities and health equity, and both can be presented in a spiritual context. In a series of leadership development seminars designed to engage faith leaders in a sustainable partnership to increase community participation in preventive HIV vaccine clinical research and to improve access to and utilization of HIV/AIDS prevention services, the most highly rated sessions were those focused on the social determinants of health.40 In a 2009 focus group study of clergy and lay members, one member articulated the connection between health behavior and health equity through the expression of God’s love as a catalyst for raising self-esteem and, consequently, taking steps to care for oneself and receive care from others.36 Focus group participants identified the religious organization as a good setting in which to have conversations about health disparities and experiences of discrimination. In every focus group, participants discussed experiences of discrimination and mistreatment by the health care system.36

Proactively addressing health inequities can help identify and resolve misconceptions about palliative and hospice care.15 In a series of interviews with a diverse sample of Black Americans, participants expressed concern that completion of an AD or other similar document would mean that health care providers would no longer provide adequate care.22 Distrust of the health care system and experiences of racialized discrimination may lead Black Americans to fear exploitation and conclude that an AD will hasten death.17 It is important for professionals working with members of the Black community to anticipate that Black patients and their family members have very likely experienced racialized discrimination in a health care setting and that such experiences may directly create reluctance to engage in ACP.41,42

According to Bullock,9 narrative data obtained from older Black Americans demystifies the small percentage of Black participants who complete written ADs. Many participants voiced concern that health care professionals would not honor their expressed wishes at the end of life. Seventy-nine percent of participants expressed the belief that God will decide if and when you die, and 65% of participants viewed the withholding or withdrawal of life support as premature.9

Mistrust of medical institutions and professionals may pose a challenge to participation in health initiatives and collaborations between public health professionals and faith organizations. Underlying beliefs about the health care system and the racism and discrimination experienced by Black Americans over a lifetime permeate cultural beliefs and values about death and dying and frame decision-making about EOL care.19 Public health professionals must remain mindful of the factors that erode collaborative trust and work toward actively building a relationship with the communities with which they hope to partner. Establishing contact with leaders within the religious organization during the planning stage and using community-based participatory research principles may help foster a sense of partnership.

In a study using focus groups of Black Americans, participants expressed concern that the Black community may be suspicious of health officials who only wanted to talk about death and dying.17 To help build trust in a group who are wary of health care professionals and institutions, professionals should work with community liaisons who live and actively engage in the Black community. Informal support networks may be the trusted mode of providing and receiving information for Black Americans.9

Technology has a (limited) role

Email and text messages offer a promising avenue for electronic communication with church members, but lack of Internet access may limit communication for many, particularly older members. Evidence suggests that older members of a congregation may prefer more personal contact and may need to rely on younger family members to help bridge the digital divide.33 Financial barriers may also impact communication for people who do not have access to computers, Internet access, or smart phones. This suggests that while technology may play an important role in dissemination of information, the best mode of communication may involve a hybrid model in which direct human contact is supplemented with technology.33

Programs that facilitate ACP literacy may help increase ACP participation among Black Americans. Unclear language commonly used in verbal and written communication about ACP may result in greater disparities in the completion rates of advance care documents, but these barriers may be overcome through interactive computer programs such as Making Your Wishes Known: Planning Your Medical Future (MYWK). MYWK is a computer-based decision aid that uses audio-visual materials and plain language to explain medical decisions. It allows users to reflect on various clinical scenarios and helps them make informed decisions about treatment preferences. In a pilot study exploring the use of MYWK among a group of Black adults, Markham and colleagues38 found that this program can be an effective tool for ACP and may help overcome some barriers to ACP among Black Americans.

Overall, our qualitative analysis of the themes present in the five studies we identified as models for ACP in faith communities emphasizes the Black Church as a potential site of opportunity for improving quality of care at the end of life. But such programs can be successful only if they start from a position of respect for the unique values and concerns of Black Americans and recognition of the suffering the Black community has experienced due to racism in general and in health care settings in particular. Building strong partnerships with the Black faith community is contingent on ensuring that leadership for the program is placed solidly in the hands of trusted faith leaders.

Findings from review of national ACP programs: application of themes

Following the literature review on characteristics of programs that increase ACP capacity and ownership in Black faith institutions, we reviewed five sets of program materials selected by the ACP/Healthy Living Through Faith (HLTF) project that have been frequently used by pastors, family caregivers, nurse’s aides, nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains to disseminate education and increase participation in ACP. These materials included the Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Oncology (African American module), the Unbroken Circle Curriculum for congregations, the Compassion Sabbath Curriculum for clergy, the National Medical Association “Bridging the Gap” Medical and Spiritual Care Toolkit for clinicians, and the Conversation Project Guidebook “Getting Started Guide for Congregations.” Some details of these programs, along with web links to their materials, are presented in Table 2. We review these programs in the light of the themes we saw in the published studies.

Table 2.

Review of five program materials.

| Program name | Developed by | Available at | Designed for use by | Intended audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Oncology (EPEC): Cultural Considerations When Caring for African Americans | Northwestern University School of Medicine 1997 | https://tinyurl.com/umuxvkp | Health professionals | African American patients |

| The Unbroken Circle: A Toolkit for Congregations Around Illness, End of Life, and Grief | Duke Institute on Care at the End of Life in collaboration with Caring Connections and Project Compassion 1999 | https://www.amazon.com/Unbroken-Circle-Toolkit-Congregations-Illness/dp/097967901X | Professional clergy, faith community nurses, and lay leaders | Congregations and faith communities in general |

| Compassion Sabbath Resource Kit | Midwest Bioethics Center and the Compassion Sabbath Task Force 1999 | https://www.practicalbioethics.org/ | Pastors, religious educators | Congregation members and families |

| Key Topics on End-of-Life Care for African Americans | National Conference to Improve End of Life Care for African Americans and Duke Institute on Care at the End of Life 2004 | https://tinyurl.com/ue9ht2p | Pastors, religious educators in African American congregations | African American congregation members and families |

| The Conversation Project: Getting Started Guide for Congregations | The Conversation Project and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement 2018 | https://theconversationproject.org | Pastors, lay leaders | Congregations and faith communities in general |

EPEC, Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care.

The Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care (EPEC) program began in 1997 as a general education program for health professionals engaged in palliative and EOL care. Since that time the program has expanded to develop specific curricula for patient populations of interest, including children, veterans, and others. The EPEC-Oncology program was developed specifically for cancer patients, and it contained a supplement on caring for African Americans. Thus, while this supplement to one part of the EPEC is focused on issues relevant to African Americans, it is specific to the disease of cancer. Also, the material is written for health professionals and intended to be used in health care, rather than religious settings.

The program begins from the stance that African Americans have different attitudes toward ACP than Whites. These differences are acknowledged to stem from communication disparities with health care providers, mistrust of the system, lack of access to care, a history of inequitable and sometimes unethical care, and other barriers to quality care. In other words, the role of providers of care is seen as a piece of the problem that needs to be addressed. Thus, there is a good representation of our themes of exhibiting cultural competency, building trust, and addressing health disparities. However, as the program is not intended for implementation in faith communities, there is no attention to building the capacity of these institutions or fielding their leadership and resources.

This program could potentially be adapted for use by Black faith communities by health professionals already in those communities—such as parish nurses—in order to gain the trust of congregation members and build community capacity. It would also be helpful for any such program to address a wider range of EOL issues in addition to cancer, including Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease, diabetes, and so on.

The Unbroken Circle: A Toolkit for Congregations around Illness, End of Life, and Grief is a program developed at Duke University. This extensive “toolkit” was developed for Judeo-Christian congregations, to assist them in leading their own ACP programs. It begins with a self-assessment tool for faith groups to help them discern their capacity to address these issues, as well as identifying what congregational resources are already available and what are needed. It provides a wide array of resources for congregational care, education, and other ministries on palliative and EOL care, as well as legal, financial, and final arrangements. It includes ideas for incorporating scripture, liturgy, and doctrinal teachings into worship, prayer groups, and other ministries.

This capacity-based, capacity-building approach was developed in 1999 by the Duke Institute on Care at the End of Life, in collaboration with the organizations Caring Connections and Project Compassion. Because it is an older program (one of the very first for lay leaders), its media resources could be updated. The program’s structure and detail are extensive and may be more in-depth than congregations with multiple priorities can fully take advantage of; at the same time the program provides options to choose from. The program takes a broad, ecumenical Judeo-Christian approach and thus is not tailored to any specific denominational groups or to the Black Church.

The Unbroken Circle program has strong representation of several of our important themes. The program addresses cultural competency by stressing a perspective-sharing approach, assuring that the range of participants’ wishes regarding, for example, ADs be treated with respect. It stresses employing faith leaders and assessing and utilizing existing resources, and from there, building capacity of the institution to lead the program in an autonomous and sustainable way, thereby building trust. Importantly, it provides guidance for faith leaders to set a spiritual/Biblical context for discussions. Its shortcoming for our purposes is that it does not address African American faith communities directly, or the context of experiences of racism and mistrust that set the context for discussions of these topics. Nevertheless, the strong emphasis on capacity-building and cultural competency could provide the basis for developing a more tailored program.

The Compassion Sabbath Resource Kit was a similarly early program from 1999, developed by the Midwest Bioethics Center and the Compassion Sabbath Task Force. This kit contains plans for workshops, curricula for educational programs, and worship and devotional materials. Like the Unbroken Circle program, the materials were designed expressly for congregations, but the Compassion Sabbath materials are developed more specifically for Christian, Jewish, Native American, Islamic, and Hindu communities. They are also different in that they are delivered by trainers from the program who work with the local faith leaders. The full curriculum consists of six 2-h sessions devoted to understanding palliative and hospice care, ACP, durable power of attorney for health care, and do-not-resuscitate orders. The program culminates in having participants complete an AD and promising to have a conversation with a loved one about their EOL preferences.

A strength of the program is that it approaches the concepts of “hope” and “a good death” with the understanding that this may mean different things in different communities and that a diversity of cultural views and values should be respected. The program is also very attentive to the spiritual context of the materials, so those themes are well-represented. However, the program does not have materials that are directed at the specific issues of health disparities and mistrust of the health care system that are common contexts for African American faith communities. Also, the fact that leadership for the program comes from outside the congregation gives the program less ability to build capacity in the faith community itself and to keep the initiative sustainable.

Key Topics on End-of-Life Care for African Americans is a set of resources assembled in 2004 for the National Conference to Improve End of Life Care for African Americans and the Duke Institute on Care at the End of Life. The many different resources that were assembled were intended for use by faith leaders and educators in African American congregations; many were derived from HIV/AIDS programs originally. Programs included the Palliative Training and Education Program (PTEP) that trained 130 pastors and lay people in local churches in Harlem to advocate for dying patients and their families; the Balm of Gilead initiative that trained faith communities to be centers for HIV/AIDS ministries in African American churches; the National Faith-Based HIV/AIDS Training and Technical Assistance Center that focuses on capacity-building in African American churches; and the Five Wishes© program used widely in many populations that promotes the use of living wills addressing medical as well as emotional, spiritual, and personal dimensions of EOL preferences.

The starting perspective for this project was that racism and poverty adversely affect the quality of care for African Americans at the end of life and that the history of slavery must be taken into account in understanding the general mistrust of Black Americans toward the health care system in general and ACP specifically. This perspective places the Black Church as a central resource in improving care at the end of life.

Capacity-building is a common theme among the programs, in that most were focused on training faith community leaders and members to start ministries in their own communities. Other notable strengths were their ability to address racial health disparities and to build trust.

The Conversation Project: Getting Started Guide for Congregations was developed in 2012 by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and has been regularly updated. The Conversation Project’s website is open to both individuals and groups to download videos and text resources that will jump-start “the conversation.” The program emphasizes a team-based approach, to “reach people where they live, work, and pray” and recommends starting with an assessment of the current knowledge, interest, and resources in the congregation. It also recommends recruiting the lay members of the congregation to be leaders in the effort but asserts that clergy leadership is essential. This guide suggests the use of sacred texts and traditions for teaching in faith communities. It uses a perspective-sharing approach that respects differences in beliefs about death and dying.

The team-based approach, the initial assessment of resources, and the goal of meeting people where they already are exemplify the themes of capacity-building, employing faith clergy and lay leadership, and using existing resources, as well as nurturing sustainability. The recommendation of using sacred texts is another important theme that comports with the themes of successful programs for African American faith communities. The Conversation Project, however, has not specifically developed materials that have a starting point of the Black experience of health disparities and health care access that has been shaped by systemic racism.

The materials from these five sources had similarities and differences. We found that while all of these materials include invaluable guidance on ACP education and dissemination, several have not been updated in as many as 20 years; almost all would benefit from incorporating the findings of the recent research reviewed above. Furthermore, these materials were often quite elaborate and not always as accessible, intuitive, or practically useful as they might be. Accessibility is a particular issue for those that require Internet access, which may be slow or nonexistent in rural or otherwise underserved areas. We suggest that many of them could benefit from more condensed versions that could be meshed with the other priorities of a congregation or faith-based organization. Overall, the goal remains as important as ever: to achieve better alignment of ACP education materials with the African American faith community, and ultimately to accomplish long-term implementation and success of ACP education initiatives for all groups by outreach to the most underserved.

Conclusion

In this article, we have attempted to tether empirical findings from recent studies of individual ACP education initiatives in African American congregations to frequently used standard ACP education program materials in order to achieve better alignment of these materials with the needs of the African American faith community. In doing so, we build upon the significant contributions of researchers in the field of health disparities research.

Content analysis of five empirical studies of ACP education initiatives in African American faith institutions revealed nine key themes related to program success and sustainability. Successful implementation and ongoing effectiveness of ACP programs in primarily African American congregations is contingent on building capacity and fostering sustainability by involving faith leadership, using existing resources and ministries, exhibiting cultural competency, preserving a spiritual/Biblical context, addressing health disparities, building trust, and selectively employing technology.

Evaluation of five well-known ACP education program materials frequently used by pastors, family caregivers, nurse’s aides, nurses, physicians, social workers, and chaplains from a variety of religious traditions revealed a need to tailor these materials for use by African American faith communities. While these materials all include invaluable guidance on ACP education, almost all would benefit from incorporating the key findings of the literature reviewed above.

Ensuring equitable, goal-concordant care at the end of life is one way to reduce patient and family distress during life’s most vulnerable moments. A dignified death is one that aligns treatment with a patient’s goals and values. To be considered goal-concordant, care must reflect the patient’s care preferences and objectives. While ACP offers a path toward successful communication and fulfillment of patients’ physical, emotional, and spiritual needs at the end of life, racialized disparities between Black and White Americans persist in EOL care planning.

The Black Church was born in slavery and has remained the most continuously independent, stable, and dominant institution in Black communities for 400 years. It has been the central site for organizing for social justice, overcoming racism, and improving the lives of Black Americans. Working with Black faith communities to increase ACP awareness and education is one way to bring the goals and values of Black Americans into alignment with the treatment they receive at the end of life. Faith-based ACP education initiatives that are effective and stable over time may help forge the link between care preference and lived experience. This will require partnership between the faith sector and the health sector. As Dr Richard Payne43 writes,

Serious engagement with the religiously minded majority of African Americans to promote earlier referral to palliative care and hospice, longer lengths of stay, and fewer withdrawals from hospice care requires partnerships between community-based clergy, chaplains, and hospice personnel that provide ongoing conversations and education to engage deeply specific aspects of theology and religious belief. (p. 132)

There is much promise in forging those partnerships but they will require wise engagement and honest acknowledgment of the lived reality of Black Americans in order to achieve the goal of reducing the stark disparities in EOL care.

Acknowledgments

This review and analysis was begun by Dr Richard Payne, who died suddenly in January 2019 as this project was underway. Dr Payne was a giant in the field of palliative care medicine who held appointments at leading cancer treatment centers including the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston and Memorial Sloan Kettering in New York. His perspective on palliative care was equally informed by his involvement in religion and ethics, with appointments at the Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City, MO, and the Duke University Divinity School. No one could have been better placed to make a difference in the quality of end-of-life care for African Americans; his loss is deeply felt across many institutions. The ACP/HLTF project was started by Dr Payne to increase African American participation in ACP activities throughout the life span. The project connected local hospice organizations with nine churches in five cities (Atlanta, Chicago, Dallas, Philadelphia, and West Palm Beach) to offer educational resources and advice on ACP to lay “ACP Ambassadors.” The ACP/HLTF project also convened the African American Advance Care Planning/Palliative Care (AA ACP/PC) network to discuss ongoing projects and identify opportunities for collaboration between ACP and palliative care experts. This work identified pastoral education on end-of-life care issues as critical to strengthening the ties between faith communities and health care providers and institutions (https://practicalbioethics.org/programs/advance-care-planning-for-african-american-faith-communities.html). The authors would like to thank the Center for Practical Bioethics and the John and Wauna Harman Foundation for their support of this project; Dr Tammie Quest for bringing us together; Dr Richard Payne and Danna Hinton for their initial identification of the programs; and the many authors and developers of these programs for their work in improving end of life care for all people. The authors were tasked with taking up the review of programs that Dr Payne had started before his untimely death in 2019; we have tried to remain true to the intention and vision of the project he began.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Support was provided by the John and Wauna Harman Foundation through the Center for Practical Bioethics.

ORCID iDs: Jenny McDonnell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8518-4405

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8518-4405

Ellen Idler  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3616-5275

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3616-5275

Contributor Information

Jenny McDonnell, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Ellen Idler, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, USA.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine. Dying in America: improving quality and honoring individual preferences near the end of life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2015, http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18748 (accessed 27 November 2018). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institute on Aging. Advance care planning: healthcare directives. National Institute on Aging, https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/advance-care-planning-healthcare-directives (accessed 5 June 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010; 340: c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Teno JM, Gruneir A, Schwartz Z, et al. Association between advance directives and quality of end-of-life care: a national study: advance directives and the quality of end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007; 55: 189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bischoff KE, Sudore R, Miao Y, et al. Advance care planning and the quality of end-of-life care in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013; 61: 209–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, et al. Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life Medicare expenditures. JAMA 2011; 306: 1447–1453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med 2009; 169: 480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright AA. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008; 300: 1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bullock K. Promoting advance directives among African Americans: a faith-based model. J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 183–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carr D. Racial differences in end-of-life planning: why don’t Blacks and Latinos prepare for the inevitable? Omega 2011; 63: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson KS, Kuchibhatla M, Tulsky JA. What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? Racial differences in beliefs about end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008; 56: 1953–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wicher CP, Meeker MA. What influences African American end-of-life preferences? J Health Care Poor Underserved 2012; 23: 28–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang IA, Neuhaus JM, Chiong W. Racial and ethnic differences in advance directive possession: role of demographic factors, religious affiliation, and personal health values in a national survey of older adults. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 149–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee M, Reddy K, Chowdhury J, et al. Overcoming the legacy of mistrust: African Americans’ mistrust of medical profession. J Healthc Ethics Adm 2018; 4: 16–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: S17–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sewell AA. Disaggregating ethnoracial disparities in physician trust. Soc Sci Res 2015; 54: 1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Waters CM. Understanding and supporting African Americans’ perspectives of end-of-life care planning and decision making. Qual Health Res 2001; 11: 385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. West SK, Hollis M. Barriers to completion of advance care directives among African Americans ages 25-84: a cross-generational study. Omega 2012; 65: 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bullock K. The influence of culture on end-of-life decision making. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care 2011; 7: 83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Caralis P, Davis B, Wright K, et al. The influence of ethnicity and race on attitudes toward advance directives, life-prolonging treatments, and euthanasia. J Clin Ethics 1993; 4: 155–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: a review of the literature: spirituality and African-American culture. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005; 53: 711–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rhodes RL, Elwood B, Lee SC, et al. The desires of their hearts: the multidisciplinary perspectives of African Americans on end-of-life care in the African American community. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2017; 34: 510–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH, Mamiya LH. The Black Church in the African American Experience. Duke University Press, 1990, https://books.google.com/books?id=W_oSBFOgzJYC [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cone JH. A Black theology of liberation. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mazanec PM, Daly BJ, Townsend A. Hospice utilization and end-of-life care decision making of African Americans. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2010; 27: 560–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elk R. and Special Issue Guest Editor. The first step is recognizing, acknowledging, and respecting the inequity, disrespect, and disregard our African American patients have experienced. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 124–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sanders JJ, Robinson MT, Block SD. Factors impacting advance care planning among African Americans: results of a systematic integrated review. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 202–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hendricks Sloan D, Peters T, Johnson KS, et al. Church-based health promotion focused on advance care planning and end-of-life care at Black Baptist churches: a cross-sectional survey. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Campbell MK, Hudson MA, Resnicow K, et al. Church-based health promotion interventions: evidence and lessons learned. Annu Rev Public Health 2007; 28: 213–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Charmaz K. The grounded theory method: an explication and interpretation. In: Emerson RM. (ed.) Contemporary field research: a collection of readings. Toronto, ON, Canada: Little, Brown and Company, 1983, pp. 109–126. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Johnson J, Hayden T, Taylor LA, et al. Engaging the African American Church to improve communication about palliative care and hospice: lessons from a multilevel approach. J Palliat Care 2018; 34: 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Francis SA, Liverpool J. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. J Relig Health 2009; 48: 6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holt CL, Graham-Phillips AL, Daniel Mullins C, et al. Health ministry and activities in African American faith-based organizations: a qualitative examination of facilitators, barriers, and use of technology. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2017; 28: 378–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Medvene LJ, Wescott JV, Huckstadt A, et al. Promoting signing of advance directives in faith communities. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18: 914–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abara W, Coleman JD, Fairchild A, et al. A faith-based community partnership to address HIV/AIDS in the Southern United States: implementation, challenges, and lessons learned. J Relig Health 2015; 54: 122–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kaplan SA, Ruddock C, Golub M, et al. Stirring up the mud: using a community-based participatory approach to address health disparities through a faith-based initiative. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2009; 20: 1111–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Elk R. The need for culturally-based palliative care programs for African American patients at end-of-life. J Fam Strengths 2017; 17: 14. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Markham SA, Levi BH, Green MJ, et al. Use of a computer program for advance care planning with African American participants. J Natl Med Assoc 2015; 107: 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Born W, Greiner KA, Sylvia E, et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs about end-of-life care among inner-city African Americans and Latinos. J Palliat Med 2004; 7: 247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alio AP, Lewis CA, Bunce CA, et al. Capacity building among African American faith leaders to promote HIV prevention and vaccine research. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2014; 8: 305–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holloway KFC. Their bodies, our conduct: how society and medicine produce persons standing in need of end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 127–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kennard CL. Undying hope. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 129–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Payne R. Racially associated disparities in hospice and palliative care access: acknowledging the facts while addressing the opportunities to improve. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]