Abstract

Background

The objective of the study was to assess the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings in COVID-19 patients.

Aims

This was an observational retrospective cohort from electronic medical records of hospitalized patients (n = 2655) with confirmed COVID-19 between February 15, 2020, and April 15, 2020, in 182 hospitals from a large health system in the USA. The review of data yielded to a total of 79 patients in 20 hospitals who had CSF analysis.

Methods

Outcomes during hospitalization, including hospital length of stay, disease severity, ventilator time, and in-hospital death were recorded. Independent variables collected included patient demographics, diagnoses, laboratory values, and procedures.

Results

A total of 79 patients underwent CSF analysis. Of these, antigen testing was performed in 73 patients. Ten patients had CSF analysis for general markers such as total protein, cell count, glucose, clarity, and color. Seven of the 10 cases (70%) had normal total cell count and normal white blood cell count in CSF. Sixty-three percent (5/8) had elevated total protein. Two patients had normal levels of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and 1 patient had significantly elevated (fourfold) neuron-specific enolase (NSE) level in CSF.

Conclusion

Unlike bacterial infections, viral infections are less likely to cause remarkable changes in CSF glucose, cell count, or protein. Our observations showed no pleocytosis, but mild increase in protein in the CSF of the COVID-19 patients. The fourfold elevation of NSE may have diagnostic/prognostic value as a biomarker in CSF for COVID-19 patients who have altered mental status.

Graphical abstract

Keywords: CSF, Cerebrospinal fluid, Hypernatremia, Sodium, COVID-19, SARS-CoV2

Introduction

The coronaviruses are RNA viruses that are responsible for zoonotic infections. The strains of coronaviruses that have caused outbreaks in recent history include the systemic acute respiratory syndrome by SARS-CoV and the Middle East respiratory syndrome by MERS-CoV. SARS-CoV was the causal agent of the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreaks in 2002 and 2003 in China, while MERS-CoV was the responsible agent for the outbreak in 2012 in Saudi Arabia [1]. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by a new strain of coronavirus type 2, SARS-COV-2 [2].

COVID-19 presents with various symptoms ranging from mild to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), as well as gastrointestinal symptoms, cardiovascular, and neurologic symptoms. There are worldwide reports of neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 [3–14]. Central nervous system manifestations were reported between 25 and 57% with less frequent symptoms of neuropathy and musculoskeletal signs. These symptoms vary from encephalitis, encephalopathy, acute demyelination, acute cerebrovascular events, altered mental status, impaired consciousness, dizziness, ataxia, seizures, hypogeusia, hyposmia, neuropathic pain, and headache.

In critically ill patients with neurological symptoms, the CSF analysis helps differential diagnosis and can serve as a marker of severity and prognosis, especially in bacterial infections. The CSF findings are also valuable in acute inflammation and demyelination [15]. In addition to the analysis of general components of CSF, antigen, antibody, and other biomarker tests can be valuable for prognosis. Several biomarkers such as S100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP) were shown to be associated with the clinical outcome in patients with head concussion trauma, ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, cardiac arrest, anoxic encephalopathy, encephalitis, brain metastasis, and status epilepticus [16–20].

In this observational cohort study, we evaluated the cerebrospinal fluid findings in hospitalized patients with confirmed COVID-19.

Methods

Study design

This observational retrospective cohort study was conducted through the electronic medical records (EMR) of 182 hospitals of large health system across the USA. The EMR of hospitalized patients (n = 2655) with confirmed novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) between February 15, 2020, and April 15, 2020, were reviewed. The data extraction yielded to a total of 79 patients in 20 hospitals who had encephalopathy and underwent CSF analysis.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who were hospitalized and had confirmed positive COVID-19 (ICD10 U07.1) were included in this study. Patients were considered to have confirmed COVID-19 infection if the initial nasopharyngeal swab result was positive for SARS-CoV-2 by the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing.

Main outcomes and measures

Outcomes included hospital length of stay, disease severity, ventilator time, and in-hospital death. Patient demographics, diagnosis labs, and procedures were also reviewed.

Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the HCA Institutional Review Board (IRB) Manager system (Protocol no: 2020-551). The requirement for written informed consent was waived as the obtained data was de-identified.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from HCA but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of HCA.

Statistical analysis

The frequency analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software for Windows version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

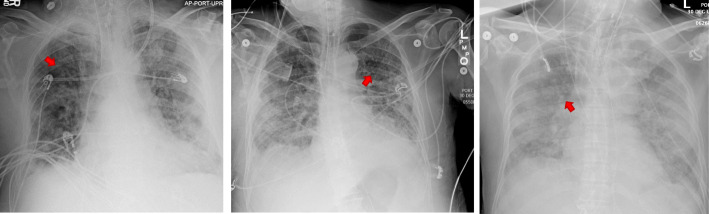

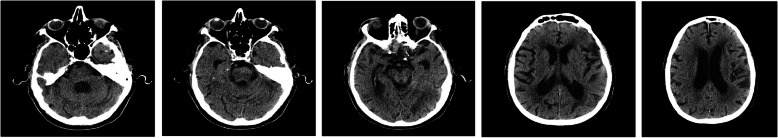

A total of 79 patients in 20 hospitals had CSF analysis. The mean age was 65 ± 15 years [range 25-90; median 68 years]. Seventy-five percent of the patients were 55 years old and above. Sixty-three percent were male. Twenty-four percent of the patients presented neurological symptoms such as encephalopathy, altered mental status, impaired consciousness, dizziness, ataxia, myoclonus, unspecified convulsions, loss of taste or smell, facial weakness nausea, vomiting, aphasia, dysphasia, and lack of coordination. Sixty-six percent stayed in the hospital for more than 3 days and 35% required ventilator support for more than 72 h (Table 1). The chest x-ray and brain MRI are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of the patients who had a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. N = 79

| N | (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | < 55 | 20 | 25.3 |

| ≥ 55 | 59 | 74.7 | |

| Sex | Male | 50 | 63.3 |

| Female | 29 | 36.7 | |

| Race | White | 46 | 58.2 |

| Black or African American | 22 | 27.8 | |

| Asian | 2 | 2.5 | |

| Other | 9 | 11.4 | |

| Hypernatremia | Yes | 20 (4 of them persistent) | 25.3 (20% of hypernatremia cases were ≥ 48 h) |

| No | 59 | 74.7 | |

| Disease severity | Mild-moderate | 37 | 46.8 |

| Severe-critical | 42 | 53.2 | |

| In-hospital mortality | Ex | 19 | 24.1 |

| Survivor | 60 | 75.9 | |

| Hospital length of stay | ≥ 1 week | 27 | 34.2 |

| < 1 week | 52 | 65.8 | |

| Ventilator time | ≥ 72 h | 28 | 35.4 |

| < 72 h | 3 | 3.8 | |

| None | 48 | 60.8 |

Fig. 1.

Chest X-rays of the three patients with COVID-19. Red arrows indicate the ground-glass opacities

Fig. 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain

Twenty of these patients had hypernatremia and 4 (20%) of these had persistent hypernatremia for ≥ 48 h.

The CSF was used for testing the presence of bacterial or viral antigens in 73 patients. The primary antigen testing was for Streptococcus pneumonia (74%) followed by adenovirus (17.8%). Ten patients had CSF analysis for proteins, cell count, glucose, and general appearance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis. N = 79 patients

| Type/detail | N (%) | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogen antigen/antibody | Streptococcus pneumonia | 54 (74.0) | 99% negative 1 positive for Streptococcus pneumonia 1 false positive for West Nile virus |

| Adenovirus ADV | 13 (17.8) | ||

| Cryptococcus sp. | 3 (4.1) | ||

| Herpes simplex virus HSV | 3 (4.1) | ||

| VDRL | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Cytomegalovirus | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Enterovirus | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Escherichia col | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Varicella zoster | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Influenza | 2 (2.7) | ||

| West Nile | 2 (2.7) | ||

| Total | 73 patients (97 results) | ||

| Antibody | Immunoglobulin G | 2 | 1 normal +1 high |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase | 2 | normal |

| NSE | Neuron specific enolase | 1 | Very high (fourfold) |

| CSF analysis | Clarity | 8 | 7 clear +1 cloudy |

| Color | 8 | 7 colorless +1 red | |

| Glucose | 8 | 7 high | |

| 1 normal | |||

| Total protein | 8 | 5 high | |

| 3 normal | |||

| Total cell count | 10 | 3 high | |

| 7 normal | |||

| WBC | 10 | 4 high | |

| 6 normal | |||

| Total | 79 patients (130 results) |

ADV adenovirus; HSV herpes simplex virus; LDH lactate dehydrogenase; NSE neuron-specific enolase; VDRL Venereal Disease Research Laboratory; WBC white blood cells; IRB Institutional Review Board

Discussion

Unlike bacterial infections, viral infections are less likely to cause remarkable changes in CSF glucose, cell count, or protein [15, 21]. However, there is increasing evidence about the neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 in COVID-19 resulting in disseminated encephalomyelitis and encephalopathies [22–27]. One hypothesis is that the respiratory failure could be partially due to the neuroinvasion of the brain issue—particularly brain stem and medulla oblongata [28]. The virus uses ACE2 to enter the cell, which is abundantly present in the capillary endothelium of the cerebral tissue [29]. The infection of SARS-CoV has been reported in the brains from both patients and experimental animals, where the brainstem was heavily infected [28]. However, the researchers from the USA could not detect SARS-CoV2 antigen in the CSF of two-stroke cases, which raises the doubt about blood-brain barrier disruption theory in COVID-19 infections [30]. Another paper also failed to detect the virus antigen in a patient with encephalopathy despite the marked increase in the interleukins predominantly IL-10 [31]. Hence, a study from Brazil reported a demyelinating disease in which the viral genome of SARS-CoV was detected in CSF [32]. Another surprising finding was that the virus RNA was detected in CSF but not in the nasopharyngeal swab taken from a patient with meningitis/encephalitis in Japan [27]. The same phenomenon was seen in a 20-year-old patient in Ireland [33].

A recent paper from the USA reported increased IgM and cytokine levels in the CSF of three patients with encephalopathy and encephalitis [23]. Increased protein and IgG but normal cell count was observed in a patient from Switzerland who had cerebral microbleeds, and focal EEG changes associated with COVID-19 [34] (Fig. 1). On the other hand, there was no significant change in the CSF of a COVID-19 patient with encephalitis in Wuhan. The total protein, WBC count, and glucose were within the normal range and they were not able to detect anti-SARS-CoV2 IgM and IgG in CSF [25]. Normal CSF findings were also reported for other two cases from Iran [22, 35]. Another 2 cases from France and 2 from the USA also revealed normal cytology and elevated protein and glucose [36, 37]. Consistent with these reports, our small cohort showed that 7 of the 10 cases (70%) had normal total cell count and normal WBC count in CSF. Sixty-three percent (5/8) had mildly elevated total protein. Additionally, two patients had normal levels of LDH and 1 patient had significantly elevated neuron-specific enolase in CSF, which is an indicator of neuronal damage. Supporting our findings, the CSF analysis of a patient from Sweden with COVID-19-related acute necrotizing encephalopathy, showed only a slight increase in protein and monocytes, while the levels of neuronal injury markers such as tau, NfL (neurofilament light), and GFAP were extremely high [24]. Based on the observation from our small cohort, we found that COVID-19 encephalopathy does not cause remarkable changes in CSF in terms of cell count and protein amount, but an increase in neuronal injury biomarker NSE (Fig. 2).

Another interesting observation was that our 6 of the 8 cases had hypernatremia, which was persistent in 4 cases lasting for more than at least 48 h. Our observation with hypernatremia has also been reported recently by other researchers [38]. They observed treatment-resistant hypernatremia in 6 of their 12 critically ill patients who required mechanical ventilation. There did not find any correlation between plasma sodium concentrations and sodium input. However, plasma chloride was elevated. This elevation was accompanied by a decrease in potassium, which was consistent with abnormally increased renal sodium reabsorption [38]. It is known that prolonged hypo- and hypernatremia may contribute to encephalopathy and osmotic demyelination and is associated with increased mortality [39]. As an indicator of neuronal injury, NSE increase in CSF in Guillain-Barre syndrome was shown in earlier studies [40]. Seven of our 8 patients also had severe sepsis resulting in multi-organ failure. Six of our 8 cases expired and the average length of stay in hospital for these 8 was 30 days. Furthermore, all of them required ventilator support varying between 5-28 days. The laboratory work revealed sepsis and morbidities associated with sepsis (Table 3). It is well-known that the metabolic changes in sepsis, particularly sodium imbalance may result in demyelination and disruption of blood-brain barrier which enables the entrance of the pathogen to the central nervous system.

Table 3.

The clinical profile of patients who had a CSF analysis. N = 8

| Hypernatremia | Normal sodium | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | ||

| Demographics | Age (years) | 79 | 66 | 76 | 77 | 58 | 82 | 64 | 64 |

| Sex | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | |

| Race | White | Asian | Asian | White | White | White | White | White | |

| Serum (highest) | White blood cell count (#/ul) | 10.0 | 23.1 | 31.4 | 13.63 | 19.8 | 10.3 | 45.9 | 18.2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 14.9 | 15.2 | 13.4 | 16.7 | 14 | 11.7 | 14.7 | 12.6 | |

| D-dimer (mg/L FEU) | 3.768 | 31.04 | 1.62 | 2.60 | 36.39 | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 34 | 54 | 157 | 95 | 164 | 75 | 93 | 36 | |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 99 | 65 | 122 | 91 | 226 | 62 | 91 | 77 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.21 | 1.18 | 7.27 | 2.61 | 2.85 | 1.41 | 7.82 | 10.60 | |

| Troponin I (ng/mL) | 0.036 | < 0.020 | 0.210 | 0.018 | 0.352 | 0.150 | 1.110 | 0.238 | |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 163 | 152 | 146 | 156 | 150 | 163 | 142 | 145 | |

|

Hypernatremia severity • Mild (146-150 mEq/L • Moderate (151-154 mEq/L) • Severe (≥ 155 mEq/L) |

Severe | Moderate | Mild | Severe | Mild | Severe | None | None | |

| Vitals (admission) | SpO2 (%) | ? | 89 | 93 | 91 | 90 | 92 | 93 | 88 |

| Temperature (F) | ? | 98.1 | 100.4 | 97.5 | 98.3 | 97.9 | 102.7 | 101.4 | |

| Pulse (beats/min) | ? | 105 | 107 | 71 | 97 | 97 | 146 | 74 | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) | ? | 142/69 | 132/66 | 139/68 | 113/55 | 128/76 | 133/95 | 183/69 | |

| Arrival mode to Emergency Department | Walk-in | Ambulance | Ambulance | Walk-in | Walk-in | ||||

| Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) analysis | White blood cell count (#/ul) | Normal | Normal | Normal | High | Normal | Normal | Normal | High |

| Total cell count (#/ul) | Normal | Normal | High | High | Normal | Normal | Normal | High | |

| Total protein (mg/dl) | High | High | Normal | High | Normal | Normal | High | High | |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | High | Normal | High | High | High | High | High | High | |

| IgG | Normal | High | |||||||

| Neuron specific enolase (NSE) | High | ||||||||

| Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) | Normal | Normal | |||||||

| Clinical outcome | Neurological symptoms | Myoclonus, metabolic encephalopathy, unspecified convulsions, anorexia | Metabolic encephalopathy, encephalitis and encephalomyelitis, unspecified convulsions | Nausea, seizures, encephalopathy | Cerebral infarction, quadriplegia, unspecified, febrile convulsions, dysphagia | Metabolic encephalopathy, absence epileptic syndrome, intractable, with status epilepticus | |||

| Other diagnosis | Sepsis, ARDS, hypertension, benign prostate hypertrophy | Sepsis, ARDS, cardiac arrest, acute kidney failure, type 2 DM | Sepsis, ARDS, acute kidney failure, acute liver failure | Sepsis, ARDS, type 2 DM, diabetic neuropathy, nephropathy, acute diastolic heart failure | ARDS, Morbid obese, type 2 DM, HT | ARDS, type 2 DM, HL, cardiac arrest | |||

| Disease severity | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | Severe/critical | |

| Ventilator need | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Ventilator time | ? | 28 days | 25 days | 17 days | 27 days | 16 | 11 | 5 | |

| Length of stay in hospital | 26 | 41 | 45 | 20 | 39 | 20 | 31 | 17 | |

| In-hospital mortality | Ex | Ex | Ex | Ex | Discharged | Ex | Discharged | Ex | |

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort to report the CSF findings in COVID-19 patients. However, further studies are needed to have a significant analysis to evaluate the association between CSF findings and clinical outcome.

Disclaimer

This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA and/or an HCA affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA or any of its affiliated entities.

Abbreviations

- ADV

Adenovirus

- ARDS

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EMR

Electronic medical records

- GFAP

Glial fibrillary acid protein

- HSV

Herpes simplex virus

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LDH

Lactate dehydrogenase

- NfL

Neurofilament light

- NSE

Neuron-specific enolase

- PCR

Polymerase chain reaction

- SARS

Severe acute respiratory syndrome

- VDRL

Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

- WBC

White blood cells

Authors’ contributions

Study design: HT Data extraction and analysis: HT, CS Drafting the manuscript: HT Critical revision of the manuscript: HT, CS, LG, EC, JH, ES. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None

Availability of data and materials

The data stored electronically and the datasets used and/or analyzed are available at the HCA GME Research repository on request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the HCA Institutional Review Board (IRB) Manager system (Protocol no: 2020-551). The requirement for written informed consent was waived as the obtained data was de-identified and the study was an observational retrospective cohort.

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

None. The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hale Toklu, Email: Hale.toklu@ucf.edu.

Latha Ganti, Email: latha.ganti@hcahealthcare.com.

Ettore Crimi, Email: Ettore.crimi@hcahealthcare.com.

Cristobal Cintron, Email: Cristobal.cintron@hcahealthcare.com.

Joshua Hagan, Email: Joshua.hagan@hcahealthcare.com.

Enrique Serrano, Email: Enrique.serrano@hcahealthcare.com.

References

- 1.Kaufman K, Shobhit K, Cristobal C, Hossein A. The coronaviruses: past, present, future. HCA Healthcare Journal of Medicine. 2020;1(2):53–63. doi: 10.36518/2689-0216.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P, Yang XL, Wang XG, Hu B, Zhang L, Zhang W, Si HR, Zhu Y, Li B, Huang CL, et al. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad I, Rathore FA. Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID-19: a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed MU, Hanif M, Ali MJ, Haider MA, Kherani D, Memon GM, Karim AH, Sattar A. Neurological manifestations of COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2): a review. Front Neurol. 2020;11(518). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Azim D, Nasim S, Kumar S, Hussain A, Patel S. Neurological consequences of 2019-nCoV infection: a comprehensive literature review. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8790. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger JR. COVID-19 and the nervous system. J Neurovirol. 2020;26(2):143–148. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00840-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ozdag Acarli AN, Samanci B, Ekizoglu E, Cakar A, Sirin NG, Gunduz T, Parman Y, Baykan B. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from the point of view of neurologists: observation of neurological findings and symptoms during the combat against a pandemic. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2020;57(2):154–159. doi: 10.29399/npa.26148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mao L, Jin H, Wang M, Hu Y, Chen S, He Q, Chang J, Hong C, Zhou Y, Wang D, et al. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Garg RK, Paliwal VK, Gupta A. Encephalopathy in patients with COVID-19: a review. J Med Virol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Romoli M, Jelcic I, Bernard-Valnet R, Garcia Azorin D, Mancinelli L, Akhvlediani T, Monaco S, Taba P, Sellner J. Infectious Disease Panel of the European Academy of N: A systematic review of neurological manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection: the devil is hidden in the details. Eur J Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Romero-Sánchez CM, Díaz-Maroto I, Fernández-Díaz E, Sánchez-Larsen Á, Layos-Romero A, García-García J, González E, Redondo-Peñas I, Perona-Moratalla AB, Del Valle-Pérez JA, et al. Neurologic manifestations in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: the ALBACOVID registry. Neurology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Tsai ST, Lu MK, San S, Tsai CH. The neurologic manifestations of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a systemic review. Front Neurol. 2020;11:498. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsivgoulis G, Palaiodimou L, Katsanos AH, Caso V, Köhrmann M, Molina C, Cordonnier C, Fischer U, Kelly P, Sharma VK, et al. Neurological manifestations and implications of COVID-19 pandemic. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2020;13:1756286420932036. doi: 10.1177/1756286420932036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernández-Fernández F, Valencia HS, Barbella-Aponte RA, Collado-Jiménez R, Ayo-Martín Ó, Barrena C, Molina-Nuevo JD, García-García J, Lozano-Setién E, Alcahut-Rodriguez C, et al. Cerebrovascular disease in patients with COVID-19: neuroimaging, histological and clinical description. Brain. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Hrishi AP, Sethuraman M. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis and interpretation in neurocritical care for acute neurological conditions. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019;23(Suppl 2):S115–S119. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima JE, Takayanagui OM, Garcia LV, Leite JP. Use of neuron-specific enolase for assessing the severity and outcome in patients with neurological disorders. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37(1):19–26. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2004000100003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lamers KJ, Vos P, Verbeek MM, Rosmalen F, van Geel WJ, van Engelen BG. Protein S-100B, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), myelin basic protein (MBP) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and blood of neurological patients. Brain Res Bull. 2003;61(3):261–264. doi: 10.1016/S0361-9230(03)00089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall RJ, Watne LO, Cunningham E, Zetterberg H, Shenkin SD, Wyller TB, MacLullich AMJ. CSF biomarkers in delirium: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(11):1479–1500. doi: 10.1002/gps.4720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celtik C, Acunaş B, Oner N, Pala O. Neuron-specific enolase as a marker of the severity and outcome of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Brain Dev. 2004;26(6):398–402. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orhun G, Esen F, Özcan PE, Sencer S, Bilgiç B, Ulusoy C, Noyan H, Küçükerden M, Ali A, Barburoğlu M, et al. Neuroimaging findings in sepsis-induced brain dysfunction: association with clinical and laboratory findings. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(1):106–117. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seehusen DA, Reeves MM, Fomin DA. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(6):1103–1108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdi S, Ghorbani A, Fatehi F. The association of SARS-CoV-2 infection and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis without prominent clinical pulmonary symptoms. J Neurol Sci. 2020;416:117001. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2020.117001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benameur K, Agarwal A, Auld SC, Butters MP, Webster AS, Ozturk T, Howell JC, Bassit LC, Velasquez A, Schinazi RF, et al. Encephalopathy and encephalitis associated with cerebrospinal fluid cytokine alterations and coronavirus disease, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Virhammar J, Kumlien E, Fällmar D, Frithiof R, Jackmann S, Sköld MK, Kadir M, Frick J, Lindeberg J, Olivero-Reinius H, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy with SARS-CoV-2 RNA confirmed in cerebrospinal fluid. Neurology. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Ye M, Ren Y, Lv T. Encephalitis as a clinical manifestation of COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, Collange O, Boulay C, Fafi-Kremer S, Ohana M, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(23):2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moriguchi T, Harii N, Goto J, Harada D, Sugawara H, Takamino J, Ueno M, Sakata H, Kondo K, Myose N, et al. A first case of meningitis/encephalitis associated with SARS-coronavirus-2. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:55–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YC, Bai WZ, Hashikawa T. The neuroinvasive potential of SARS-CoV2 may play a role in the respiratory failure of COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol. 2020;92(6):552–555. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baig AM. Is there a cholinergic survival incentive for neurotropic parasites in the brain? ACS Chem Neurosci. 2017;8(12):2574–2577. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al Saiegh F, Ghosh R, Leibold A, Avery MB, Schmidt RF, Theofanis T, Mouchtouris N, Philipp L, Peiper SC, Wang ZX, et al. Status of SARS-CoV-2 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 and stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Farhadian S, Glick LR, Vogels CBF, Thomas J, Chiarella J, Casanovas-Massana A, Zhou J, Odio C, Vijayakumar P, Geng B, et al. Acute encephalopathy with elevated CSF inflammatory markers as the initial presentation of COVID-19. BMC Neurol. 2020;20(1):248. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01812-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Domingues RB, Mendes-Correa MC, de Moura Leite FBV, Sabino EC, Salarini DZ, Claro I, Santos DW, de Jesus JG, Ferreira NE, Romano CM, et al. First case of SARS-COV-2 sequencing in cerebrospinal fluid of a patient with suspected demyelinating disease. J Neurol. 2020:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Lyons S, O’Kelly B, Woods S, Rowan C, Brady D, Sheehan G, Smyth S. Seizure with CSF lymphocytosis as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in an otherwise healthy young man. Seizure. 2020;80:113–114. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.De Stefano P, Nencha U, De Stefano L, Mégevand P, Seeck M. Focal EEG changes indicating critical illness associated cerebral microbleeds in a Covid-19 patient. Clinical neurophysiology practice. 2020;5:125–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cnp.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afshar H, Yassin Z, Kalantari S, Aloosh O, Lotfi T, Moghaddasi M, Sadeghipour A, Emamikhah M. Evolution and resolution of brain involvement associated with SARS- CoV2 infection: a close clinical - paraclinical follow up study of a case. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders. 2020;43:102216. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2020.102216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andriuta D, Roger PA, Thibault W, Toublanc B, Sauzay C, Castelain S, Godefroy O, Brochot E. COVID-19 encephalopathy: detection of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in CSF. J Neurol. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Espinosa PS, Rizvi Z, Sharma P, Hindi F, Filatov A. Neurological complications of coronavirus disease (COVID-19): encephalopathy, MRI brain and cerebrospinal fluid findings: case 2. Cureus. 2020;12(5):e7930. doi: 10.7759/cureus.7930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zimmer MA, Zink AK, Weißer CW, Vogt U, Michelsen A, Priebe H-J, Mols G. Hypernatremia—a manifestation of COVID-19: a case series. A&A Practice. 2020;14(9):e01295. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lindner G, Funk GC. Hypernatremia in critically ill patients. J Crit Care. 2013;28(2):216.e211–216.e220. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brettschneider J, Petzold A, Sussmuth S, Tumani H. Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers in Guillain-Barre syndrome--where do we stand? J Neurol. 2009;256(1):3–12. doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-0097-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data stored electronically and the datasets used and/or analyzed are available at the HCA GME Research repository on request.