Abstract

Background and aims

Extraintestinal manifestations are common in inflammatory bowel disease patients, although there are few data available on their diagnosis, management and follow-up. We systematically reviewed the literature evidence to evaluate tools and investigations used for the diagnosis and for the assessment of the treatment response in inflammatory bowel disease patients with extraintestinal manifestations.

Methods

We searched in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science from January 1999–December 2019 for all interventional and non-interventional studies published in English assessing diagnostic tools and investigations used in inflammatory bowel disease patients with extraintestinal manifestations.

Results

Forty-five studies (16 interventional and 29 non-interventional) were included in our systematic review, enrolling 7994 inflammatory bowel disease patients. The diagnostic assessment of extraintestinal manifestations was performed by dedicated specialists in a percentage of cases ranging from 60–100% depending on the specific condition. The clinical examination was the most frequent diagnostic strategy, accounting for 35 studies (77.8%). In patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis or rheumatological symptoms, biochemical and imaging tests were also performed. Anti-TNF agents were the most used biological drugs for the treatment of extraintestinal manifestations (20 studies, 44.4%), and the treatment response varied from 59.1% in axial spondyloarthritis to 88.9% in ocular manifestations. No benefit was detected in primary sclerosing cholangitis patients after treatment with biologics.

Conclusions

In the clinical management of inflammatory bowel disease patients with extraintestinal manifestations the collaboration of dedicated specialists for diagnostic investigations and follow-up is key to ensure the best of care approach. However, international guidelines are needed to homogenise and standardise the assessment of extraintestinal manifestations.

Keywords: Extraintestinal manifestations, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, diagnosis and follow-up, axial spondyloarthritis, primary sclerosing cholangitis

Introduction

Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are both phenotypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1,2 The most frequent IBD symptoms involve the gut tract, although a variety of extra-intestinal manifestations (EIMs) can be observed.1,2 EIMs have a broad spectrum of clinical expression: articular (axial and peripheral spondyloarthritis, dactylitis and enthesitis), ocular (uveitis, episcleritis), cutaneous (pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum and Sweet syndrome), hepatobiliary (primary sclerosing cholangitis) and immune and inflammatory associated diseases (psoriasis, atopic dermatitis and hidradenitis suppurativa).3 Prevalence of these manifestations ranges from 25–40% in IBD patients.4–6 These manifestations have relevant consequences on patient’s quality of life and require complex and multidisciplinary management.7 Nowadays, a tumor necrosis factor antagonist (anti-TNF) is recognised as the best therapeutic option to manage EIMs of IBD patients,8–10 while recent vedolizumab data are disappointing.11 Other biologics (e.g. ustekinumab)12 and small molecules (e.g. tofacitinib)13 may be efficacious in these patients and have been proposed as a possible therapeutic option. However, diagnosis of EIMs and accurate evaluation of drug efficacy on EIMs are challenging and not standardised in IBD trials. Hence, available data are difficult to interpret. For this reason, we performed a systematic literature review to identify the most appropriate tools and investigations to be used for diagnosis and assessment of treatment efficacy in IBD patients with EIMs.

Methods

Search strategy

The Cochrane Handbook14 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)15 statement for reporting of systematic reviews were adopted as guidance for this work. We searched in PubMed, Embase and Web of Science databases to identify relevant studies from January 1999–December 2019. First, we screened all drug-related IBD studies (including anti-TNFα, vedolizumab, ustekinumab and tofacitinib). The following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms alone or matched with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ or ‘OR’ were used: ‘Inflammatory Bowel Diseases’, ‘IBD’, ‘Colitis, Ulcerative’, ‘Crohn Disease’, ‘tumor necrosis factor alpha’, ‘certolizumab pegol’, ‘adalimumab’, ‘infliximab’, ‘golimumab’, ‘vedolizumab’, ‘ustekinumab’ and ‘tofacitinib’. Secondly, we screened all EIM-related IBD studies. The following MeSH terms alone or matched with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ or ‘OR’ were used: ‘Inflammatory Bowel Diseases’, ‘IBD’, ‘Colitis, Ulcerative’, ‘Crohn Disease’, ‘extraintestinal manifestations’, ‘extra intestinal manifestation’, ‘erythema nodosum’, ‘pyoderma gangrenosum’, ‘primary sclerosing cholangitis’, ‘uveitis’, ‘episcleritis’, ‘ocular manifestation’, ‘ocular’, ‘spondyloarthropathy’, ‘spondyloarthritis’, ‘arthritis’, ‘arthralgia’. Two reviewers (LG and FD) independently scrutinised titles and abstracts to identify eligible studies. Subsequently, full-text articles were examined for inclusion. Any disagreements between investigators were resolved through collegial discussion. Finally, we accurately checked the reference lists of the included studies for any additional relevant work.

Selection criteria

The search strategies included common search strings for disease-related and drug-related terms. A two-step process was applied: title and abstract assessment (step one), followed by full text analysis of relevant articles (step two). The inclusion criteria were: (a) confirmed diagnosis of IBD; (b) confirmed diagnosis of ≥1 EIM; (c) studies reporting EIM assessment; (d) interventional or non-interventional study; (e) study published in English. All editorials, notes, comments, letters or review articles were excluded.

Data extraction

After screening from eligible studies, two reviewers (LG and FDA) extracted data regarding the type of EIM, study characteristics, study design, IBD phenotype, time of follow-up, tools and investigations for EIM assessment, treatment for IBD, treatment for EIM and evaluation of treatment efficacy for EIMs. Finally, a multidisciplinary panel of experts (gastroenterologist, ophthalmologist, dermatologist and rheumatologist) was involved in the analysis of the collected data and in the subsequent definition of recommendations for the assessment of EIMs.

Quality of studies

Quality of non-randomised trials was measured through the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS)16 score, while in randomised clinical trials the Jadad score17 was used. NOS is made up of eight items: ‘representativeness of the exposed cohorts’, ‘selection of the non-exposed cohort’, ‘ascertainment of exposure’, ‘demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study’, ‘comparability of cohorts on the basis of the design or analysis’, ‘assessment of the outcome’, ‘follow-up is long enough for outcomes to occur’ and ‘adequacy of the follow-up’. The NOS score ranges from 0–9 and is based on the assignment of two stars for comparability of cohorts, while the other items can be assigned only one star. A NOS score ≥6 indicated high quality studies, while studies with NOS values of 1–3 and 4–5 were defined as low and moderate quality studies respectively. The Jadad score ranges from 0–5 and assigns one point for each of the following parameters: randomised study, appropriate randomization, double blind study, appropriate double-blind study, description of withdrawals/dropouts. A study was of a good quality if the Jadad score was ≥3. Two authors (LG and FDA) independently graded the studies and disagreements were discussed with the other authors until their resolution.

Results

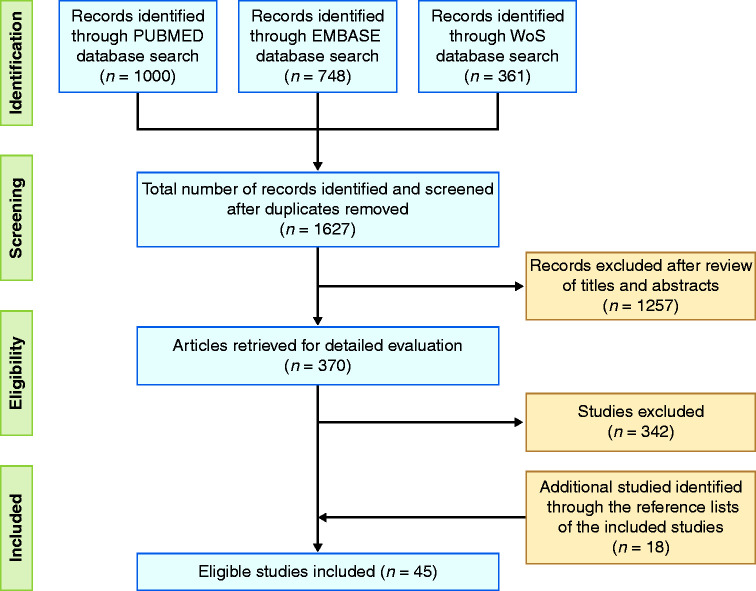

A flow diagram reporting the study selection process is provided in Figure 1. A total of 2109 eligible studies were identified through the literature search on Pubmed (1000), EMBASE (748) and Web of Science (361). After removal of duplicates, 1257 articles were excluded after screening of titles and abstracts. An additional 343 studies were excluded after full-text analysis of the manuscripts since they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Eighteen works were identified through the reference lists of the studies. Finally, 45 studies4,18–61 met the inclusion criteria and were evaluated. There were 15 interventional studies (14 open label (OL) trials20–27,30,32,33,36,49,50 and one randomised controlled trial (RCT)42) and 30 non interventional studies (12 retrospective cohort studies,28,31,45,48,52,54,56–61 10 case reports,18,19,35,38–41,43,44,47 four prospective cohort studies4,29,37,55 and four case control studies).34,46,51,53 A Jadad score = 4 was assigned to the RCT.42 Among the studies evaluated through the NOS scale there were four low (8.9%),19,35,39,43 15 moderate (33.3%)18,21,23,25,30,33,38,40,41,44,45,47–50 and 25 high quality studies (55.6%)4,20,22,24,26–29,31,32,34,36,37,46,51–61 (Supplementary Material Tables 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram reporting the study selection process.

Table 1.

Studies on rheumatological manifestations.

| Study | Type of EIM | IBD patients | Study design | Follow-up | Tools/method for diagnosis | Treatment for EIM | Efficacy assessment of EIM treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van den Bosch et al., 200018 | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 2) | CD (n = 2) | Case report | No data | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 2), 1 to 2 infusions | Clinical assessment + CRP; 2 complete response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 3) | CD (n = 3) | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 3), 2 infusions | Clinical assessment + CRP; 3 complete response | |||

| Ellman et al., 200119 | Sacroiliac joint (n = 1), lower back pain (n = 2) | CD (n = 2) UC (n = 1) | Case report | No data | Clinical evaluation + X-ray (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 4), ≥4 infusions | Clinical assessment; 2 complete and 2 partial response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis(n = 4) | CD (n = 3) UC (n = 1) | ||||||

| Herfarth et al., 200220 | Arthralgia (n = 43) | CD (n = 43) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 12 weeks | Clinical evaluation: painful, no swollen or joint effusion (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 43) | Clinical assessment: 4-point scale (severe, moderate, mild or none); 61% improved by at least 1 point |

| Reinisch et al., 200321 | Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 13) | IBD (n = 13) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 20 days | Clinical evaluation: swollen or joint effusion + HAQ (gastroenterologist) | Rofecoxib 12.5 to 25 mg/day (n = 11) | Clinical assessment + HAQ; 36% of response |

| Arthralgia (n = 19) | IBD (n = 19) | Clinical evaluation: joint pain + HAQ (gastroenterologist) | Rofecoxib 12.5 to 25 mg/day (n = 18) | Clinical assessment + HAQ; 50% of response | |||

| Generini et al., 200422 | Axial pain (n = 36) | CD (n = 36) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 3–18 months | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria (rheumatologist) | IFX 3 or 5 mg/kg (n = 24) | Clinical assessment, BASDAI, VAS; Significant improvement of BASDAI and VAS |

| Kaufman et al., 200423 | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 11), sacroiliitis (n = 3) | CD (n = 11) | OL prospective trial, single centre | No data | Clinical evaluation + X-ray (gastroenterologist or rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 11) | Clinical assessment; 7 complete or partial response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 3) | CD (n = 3) | Clinical evaluation (gastroenterologist or rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 3) | Clinical assessment; 1 complete and 2 no response | |||

| Arthralgia (n = 11) | CD (n = 11) | Clinical evaluation (gastroenterologist or rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 11) | Clinical assessment; 7 complete or partial response | |||

| Rispo et al., 200524 | Sacroiliitis (n = 5), ankylosing spondylitis (n = 5) | CD (n = 10) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 22 months | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria + bone scintigraphy and X-ray (New York criteria, BASRI) (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (10) | Clinical assessment, ASAS20/ASAS40, BASDAI; 80% ASAS20 and 60% ASAS40 |

| Arthralgia (n = 6) | CD (n = 6) | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 6) | Clinical assessment; 6 complete response | |||

| Conti et al., 200525 | Buttock pain (n = 11), spinal pain (n = 9), enthesopathy (n = 8) | CD (n = 3) UC (n = 4) IBD-U (n = 12) | OL prospective trial, single centre | No data | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria + X-ray and MRI (rheumatologist) | No data | No data |

| Vavricka et al., 20114 | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 39) | CD (n = 33) UC (n = 6) | Prospective cohort | 34 months | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion + X-ray (rheumatologist) | No exhaustive data | No data |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 272) | CD (n = 193) UC (n = 79) | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion: painful/ swollen/redness joints (rheumatologist) | No exhaustive data | No data | |||

| Löfberg et al., 201226 | Sacroiliitis (n = 34), ankylosing spondylitis (n = 16) | CD (n = 50) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 20 weeks | Assess by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 50) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 33 cases at Week 20 |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 82) | CD (n = 82) | Assessed by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 82) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 20 cases at Week 20 | |||

| Arthralgia (n = 445) | CD (n = 445) | Assess by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 445) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 252 cases at Week 20 | |||

| Barreiro-de-Acosta et al., 201227 | Sacroiliitis (n = 1), ankylosing spondylitis (n = 7) | CD (n = 8) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 6 months | Clinical evaluation + radiology (rheumatologist) | ADA 40 mg (n = 8) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 6 complete or partial response, 2 no response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 31) | CD (n = 31) | Clinical evaluation: swollen or joint effusion (rheumatologist) | ADA 40 mg (n = 31) | Clinical assessment; 19 complete or partial and 12 no response | |||

| Karmiris et al., 201628 | Sacroiliitis (n = 89), ankylosing spondylitis (n = 39) | CD (n = 104) UC (n = 21) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | Clinical evaluation + X-ray or MRI changes (rheumatologist) | No data | No data |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 221) | CD (n = 155) UC (n = 66) | Painful/swollen joints at clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Arthralgia (n = 311) | CD (n = 218) UC (n = 93) | Self-reporting + motility restriction + clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Landi et al., 201629 | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 45) | IBD (n = 45) | Observational cross-sectional multicentre study | No data | Clinical evaluation + ESSG criteria + New York modified criteria + BASDAI/BASRI/ BASFI/BASMI (rheumatologist) | No data | No data |

| Luchetti et al., 201730 | Ankylosing spondylitis (n = 16), other (n = 13) | CD (n = 16) UC (n = 13) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 12 months | Clinical evaluation + BASDAI/ ASDAS/ BASFI/BASMI + ASAS criteria + MRI/X-ray (New York criteria) (rheumatologist) | ADA 40 mg (n = 20) | Clinical evaluation + BASDAI/ASDAS/BASFI/BASMI |

| Vavricka et al., 201731 | Axial arthropathy (n = 45) | CD (n = 35) UC (n = 9) IBD-U (n = 1) | Retrospective multicentre study | 4 years | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | IFX, ADA or CZP (n = 34) | Clinical assessment; 59.1 to 61.8% response rate |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 160) | CD (n = 131) UC (n = 24) IBD-U (n = 5) | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | IFX, ADA or CZP (n = 158) | Clinical assessment; 73.4 to 81.2% response rate | |||

| Tadbiri et al., 201732 | Axial arthropathy (n = 12) | IBD (n = 47) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 54 weeks | Clinical evaluation at baseline (gastroenterologist) | VDZ (n = 47) | Clinical assessment; 21 complete and 10 partial response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 41) | |||||||

| Orlando et al., 201733 | Axial arthropathy (n = 2) | IBD (n = 14) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 2.6 months (median) | Clinical evaluation | VDZ (n = 14) | Clinical assessment; 6 complete or partial response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 14) | |||||||

| Yamamoto-Furusho et al., 201834 | Sacroiliitis (n = 7), ankylosing spondylitis (n = 8), both (n = 1) | UC (n = 16) | Case control single centre study | No data | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | No data | No data |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 9) | UC (n = 9) | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Arthralgia (n = 138) | UC (n = 138) | Clinical evaluation (rheumatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Fleisher et al., 201835 | Sacroiliitis + ankylosing spondylitis (n = 1) | CD (n = 1) | Case report | 5 months 4–24 months | Clinical evaluation | VDZ (n = 1) | Clinical assessment; 1 complete response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 3) | CD (n = 1) UC (n = 2) | Clinical evaluation | VDZ (n = 3) | Clinical assessment; 3 complete response but 2 recurrence | |||

| Macaluso et al., 201836 | Axial arthropathy (n = 15) | IBD (n = 43) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 22 weeks | Clinical evaluation + ASAS criteria (rheumatologist) | VDZ (n = 43) | Clinical assessment; 17 complete or partial response |

| Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 39) | |||||||

| Feagan et al., 201937 | Peripheral spondyloarthritis (n = 793) | CD (n = 708) UC (n = 85) | Post hoc analyses of RCT | No data | Screening at baseline | VDZ (n = 590) | Assessed by investigator at each visit |

| Arthralgia (n = 793) |

ADA: adalimumab; ASAS20: 20% improvement in the ASAS; ASAS40: 40% improvement in the ASAS; ASDAS: ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; BASRI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Radiology Index; CD: Crohn's disease; CRP: C-reactive protein; CZP: certolizumab pegol; EIM: extra-intestinal manifestation; ESSG: European Spondylarthropathy Study Group; HAQ: health assessment questionnaire; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; IFX: infliximab; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; OL: open label; RCT: randomised controlled trial; SPA: spondyloarthropathy; UC: ulcerative colitis; VAS: visual analog scale; VDZ: vedolizumab.

Table 2.

Studies on dermatological manifestations.

| Study | Type of EIM | IBD patients | Study design | Follow-up | Tools/method for diagnosis | Treatment for EIM | Efficacy assessment of EIM treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tan et al., 200138 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 2) | CD (n = 2) | Case report | 3–12 months | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 2) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 1 complete and 1 partial response |

| Ljung et al., 200239 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 8) | CD (n = 8) | Case report | No data | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 8) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 3 complete, 3 partial (>50% reduction symptoms) and 2 no response |

| Regueiro et al., 200340 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 13) | CD (n = 12) UC (n = 1) | Case report | 1 day–4 years | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 13), 1 to 24 infusions+ CS (n = 9), AZA/6-MP (n = 11) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 13 complete response, 3 patients treated solely with IFX for PG |

| Sapienza et al., 200441 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 4) | CD (n = 4) | Case report | 9–20 months | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 4), 1 infusion (n = 3), 3 infusions (n = 1) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 4 complete response |

| Kaufman et al., 200423 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 4) | CD (n = 3) UC (n = 1) | OL prospective trial, single centre | No data | Clinical evaluation (gastroenterologist or rheumatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 4), 2 to 4 infusions | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 1 complete and 3 partial response |

| Rispo et al., 200524 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 1) | CD (n = 1) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 22 months | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); Complete response |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 2) | CD (n = 2) | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 2) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 2 complete response | |||

| Brooklyn et al., 200642 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 30) | CD (n = 13) UC (n = 6) No IBD (n = 11) | Multicentre RCT | 6 weeks | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy if clinical doubt (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg (n = 29), 1 infusion | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 6 complete, 14 partial and 9 no response |

| Baglieri et al., 201043 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 1) | UC (n = 1) | Case report | 14 weeks | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg, 4 infusions + AZA 50 mg/day | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); Nearly complete response |

| Vavricka et al., 20114 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 17) | CD (n = 9) UC (n = 8) | Prospective cohort | 34 months | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion (dermatologist) | No exhaustive data | No data |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 48) | CD (n = 36) UC(n = 12) | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion (dermatologist) | No exhaustive data | No data | |||

| Hayashi et al., 201244 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 1) | IBD-U(n = 1) | Case report | 22 weeks | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg, 5 infusions+ AZA 50 mg/day | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); Complete response |

| Löfberg et al., 201226 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 4) | CD (n = 4) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 20 weeks | Assess by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 4) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 2 cases at Week 20 |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 23) | CD (n = 23) | Assess by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 23) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 4 cases at Week 20 | |||

| Barreiro-de-Acosta et al., 201227 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 2) | CD (n = 2) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 6 months | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | ADA 40 mg (n = 2) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 2 complete or partial response |

| Argüelles-Arias et al., 201345 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 67) | CD (n = 41) UC (n = 25) IBD-U (n = 1) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | Clinical evaluation (gastroenterologist) | CS (n = 51), IFX (24), ADA (n = 7), AZA (n = 6), TC (n = 3), Cyclosporin (n = 10) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location) |

| Weizman et al., 201446 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 92) | CD (n = 57) UC (n = 35) | Retrospective multicentre case control study | No data | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy if clinical doubt (dermatologist) | No data | No data |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 103) | CD (n = 69) UC (n = 34) | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Karmiris et al., 201628 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 15) | CD (n = 7) UC (n = 8) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy if clinical doubt (dermatologist) | No data | No data |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 99) | CD (n = 75) UC (n = 24) | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy if clinical doubt (dermatologist) | No data | No data | |||

| Vavricka et al., 201731 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 11) | CD (n = 9) UC (n = 2) | Retrospective multicentre study | 4 years | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX, ADA or CZP (n = 11) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 54.5% response rate |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 25) | CD (n = 18) UC (n = 7) | Clinical evaluation (dermatologist) | IFX, ADA or CZP (n = 10) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 80% response rate (n = 10) | |||

| Fleisher et al., 201835 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 2) | CD (n = 1) UC (n = 1) | Case report | 12–20 monthsNo data | Clinical evaluation | VDZ (n = 2), 6 infusions (n = 1) + MTX (n = 1) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 1 complete and 1 complete response but recurrence |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 1) | CD (n = 1) | Clinical evaluation | VDZ, 3 infusions | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); Complete response | |||

| Perricone et al., 201847 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 1) | UC (n = 1) | Case report | 3 months | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | IFX, 4 infusions | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); Complete response |

| Feagan et al., 201937 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 10) | CD (n = 9) UC (n = 1) | Post hoc analyses of RCT | No data | Screening at baseline | VDZ (n = 9) | Assessed by investigator at each visit |

| Erythema nodosum (n = 57) | CD (n = 51) UC (n = 6) | Screening at baseline | VDZ (n = 41) | Assessed by investigator at each visit | |||

| De Risi-Pugliese et al., 201948 | Pyoderma gangrenosum (n = 4) | CD (n = 4) | Retrospective multicentre study | 12–47 months | Clinical evaluation + skin biopsy (dermatologist) | Ustekinumab (n = 4) + CS (n = 1), Topical TC (n = 1), dCS (n = 1) | Clinical assessment (number, size, location); 3 complete and 1 partial response (>50% reduction symptoms) |

6-MP: 6-mercaptopurine; ADA: adalimumab; AZA: azathioprine; CD: Crohn's disease; CS: corticosteroid; CZP: certolizumab pegol; dCS: dermo-corticosteroid; EIM: extra-intestinal manifestation; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; IFX: infliximab; MTX: methotrexate; OL: open label; RCT: randomised controlled trial; TC: tacrolimus; UC: ulcerative colitis; VDZ: vedolizumab.

Rheumatological manifestations

Axial spondyloarthritis

Eighteen studies reported axial signs of spondyloarthritis. A total of 468 patients were included: 311 CD (76.1%), 70 UC (20.1%), 13 IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) (3.8%) and 74 unspecified patients. The diagnostic evaluation was performed by rheumatologists in 14 studies (78%).4,18,19,22–25,27–31,34,36 The European Spondylarthropathy Study Group (ESSG) or the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria were used in seven studies (39%), which include careful evaluation of symptoms and medical history, clinical examination, radiographic assessment and biochemical tests (human leukocyte antigen (HLA) B27, C-reactive protein (CRP)).18,22,24,25,29,30,36 The other studies did not include clinical evaluation details. X-ray or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed in nine cases (50%).4,19,23–25,27–30 Concerning treatment, infliximab was used in six studies (33%),18,19,22–24,31 adalimumab in four (22%),26,27,30,31 vedolizumab in four (22%)32,33,35,36 and certolizumab in one (5.5%).31 The response to treatment was investigated in 13 articles18,19,22–24,26,27,30–33,35,36 and the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) was used in three studies (16.7%),22,24,30 while the Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDAS) was used in one case (5.5%).30 The axial spondyloarthritis showed a good response to anti-TNF agents. Interestingly, in a retrospective multicentre study by Vavricka et al.31 including 45 patients, the response rate to anti-TNF ranged from 59.1–61.8% (Table 1). Vedolizumab results varied depending on the study. In the work by Tadbiri et al.,32 21 complete (44.7%) and 10 partial responses (21.3%) were detected in 47 patients with axial and/or peripheral spondyloarthritis. Orlando et al.33 described six partial or complete responses (43%) in 14 patients with peripheral and/or axial spondyloarthritis. Finally, Fleisher et al.35 reported one complete response in one treated patient while, in the study of Macaluso et al.,36 17 cases of partial or complete response were found in 43 patients (39.5%).

Peripheral spondyloarthritis

Fifteen studies reported signs of peripheral spondyloarthritis. A total of 1688 patients were studied: 1310 CD (77.6%), 266 UC (15.8%), five IBD-U (0.3%) and 107 unspecified patients (6.3%). Rheumatologists performed the diagnostic assessment in nine studies (60%).4,18,19,23,27,28,31,34,36 ESSG or ASAS criteria were used in two studies (13.3%)18,36 and the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) was used in one case (6.6%).21 Clinical examination consisted in the count of painful and swollen joints in four articles (26.7%).4,21,27,28 The other studies did not include the details of the clinical evaluation. Surprisingly, X-ray or MRI were performed in only one case.19 Concerning treatment, vedolizumab was used in five studies (33.3%),32,33,35–37 infliximab in four (26.7%),18,19,23,31 adalimumab in three (20%)26,27,31 and certolizumab in one (6.7%).31 The response to treatment was evaluated through clinical examination in 12 trials.18,19,21,23,26,27,31–33,35–37 A good response to anti-TNF agents was achieved (Table 1). Indeed, the response rate ranged from 73.4–81.2% in the retrospective multicentre study by Vavricka et al.,31 which included 160 patients. Among vedolizumab-treated patients, Fleisher et al.35 reported one complete response (33.3%) and two partial responses (66.6%), while Macaluso et al.36 found partial or complete responses in 17/43 patients (39.5%).

Arthralgia

Eight studies assessed arthralgia. A total of 1766 patients were studied: 1431 CD (81%), 316 UC (17.9%) and 19 unspecified patients (1.1%). The diagnostic screening was carried out by rheumatologists in five studies (62.5%).20,23,24,28,34 Clinical examination (evaluation of painful joints without swelling and effusions) was performed in three trials (37.5%).20,21,28 The other studies did not provide specific information on the diagnostic approach. Infliximab was the most-used drug (three studies, 37.5%),20,23,24 while adalimumab and vedolizumab were administered in one study each (12.5%).26,37 The response to treatment was evaluated in six articles (75%) and improvement was assessed by clinical examination20,21,23,24,26,37 (Table 1).

Dermatological manifestations

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG)

PG was investigated in 20 studies, including a total of 289 patients: 186 CD (64.4%), 90 UC (31.1%), two IBD-U (0.7%) and 11 without IBD (3.8%). Dermatologists were involved in diagnosis in 15 studies (75%)4,24,27,28,31,38–44,46–48 and clinical evaluation (e.g. number, size and location) was the most adopted method (18/20, 90%).4,23,24,27,28,31,35,38–48 A skin biopsy was performed in eight studies (40%).24,28,42–44,46–48 Infliximab was the most-used treatment (12 studies, 60%),23,24,31,38–45,47 followed by adalimumab (four studies, 20%),26,27,31,45 vedolizumab (two studies, 10%),35,37 certolizumab (one study, 5%)31 and ustekinumab (one study, 5%).48 The response to treatment was clinically evaluated in 17 cases,23,24,26,27,31,35,37–45,47,48 assessing number, size and location of PG. A complete response was defined as a total resolution of the skin lesion in 12 studies (60%),23,24,27,35,38–42,44,47,49 while the partial response was defined in two studies as an improvement >50% of the lesion.39,48 In 12 studies a high PG response rate to TNF inhibitors was found23,24,27,31,38–44,47 with 32 complete responses and 26 partial responses (Table 2). In the randomised controlled trial by Brooklyn et al.,42 six complete responses, 14 partial responses and nine non-responses were found among 29 patients treated with infliximab. Vavricka et al.31 reported a response rate of 54.5%. De Risi-Pugliese et al.48 showed good response to ustekinumab with three complete responses and one partial response. Fleisher et al.35 found one complete response and one partial response in vedolizumab-treated patients.

Erythema nodosum (EN)

Eight studies investigated EN, enrolling a total of 358 patients: 275 CD (76.8%) and 83 UC (23.2%). The diagnosis was obtained by dermatologists in five studies (62.5%)4,24,28,31,46 and clinical evaluation of number, size and location of EN was the most frequent approach (six studies, 75%).4,24,28,31,35,46 A skin biopsy was performed in two trials.24,28 EN was treated with infliximab (two studies, 25%),24,31 adalimumab (two studies, 25%),26,31 vedolizumab (two studies, 25%)35,37 and certolizumab (one study, 12.5%).31 The response to treatment was clinically evaluated (number, size and location of EN) in five trials.24,26,31,35,37 In the study by Vavricka et al.,31 8/10 patients (80%) had a clinical response after therapy with anti-TNF agents, while in the experience of Rispo et al.,24 2/2 infliximab-treated patients (100%) achieved complete response (Table 2).

Ocular manifestations

Eleven studies reported ocular EIMs. Multiple symptoms were observed but uveitis and episcleritis were the two most common symptoms (88.5%). A total of 396 patients were involved: 270 CD (68.2%) and 126 UC (31.8%). Ophthalmologists were frequently implicated in the diagnosis (nine studies, 82%).4,24,27,28,31,35,49–51 Slit lamp examination, visual acuity measurement and tonometry were used for EIM assessment in two studies.49,50 The three-mirror Goldmann lens, fluorescein angiography and Break-Up Time (BUT) test were used by Felekis et al.50 The other studies did not provide specific information on diagnostic assessment. The most frequent treatments included adalimumab (three studies, 27.3%),26,27,31 infliximab (two studies, 18.2%),24,31 vedolizumab (two studies, 18.2%)35,37 and certolizumab (one study, 9.1%).31 The response to treatment was clinically evaluated in eight articles.24,26,27,31,35,37,49,50 Vavricka et al.31 reported a response rate ranging from 72–88.9% in 25 patients with uveitis treated with anti-TNF drugs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Studies on ocular manifestations.

| Study | Type of EIM | IBD patients | Study design | Follow-up | Tools/method for diagnosis | Treatment for EIM | Efficacy assessment of EIM treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rispo et al., 200524 | Uveitis (n = 2) Episcleritis (n = 1) | CD (n = 3) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 22 months | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | IFX 5 mg/kg | Clinical assessment; 3 complete response |

| Yilmaz et al., 200749 | Conjunctivitis (n = 10) Blepharitis (n = 8) Uveitis (n = 6) Cataract (n = 6) Episcleritis (n = 4) | CD (n = 12) UC (22) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 12 months | Slit lamp biomicroscopy, tonometry, indirect ophthalmoscopy, and visual acuity (ophthalmologist) | No data | Monthly clinical assessment |

| Felekis et al., 200950 | Episcleritis (n = 2) Iridocyclitis (n = 3) Conjunctivitis (n = 1) Dry eye (n = 13) Choroiditis (n = 1) Optic neuritis (n = 1) Retinal vasculitis (n = 1) | CD (n = 23) UC (n = 37) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 10 years (median) | Slit lamp, tonometry, visual acuity, 3-mirror Goldmann lens, Fluorescein angiography, BUT test (ophthalmologist) | CS (n = 1), CS drop (n = 2), NSAID drop (n = 2) | every 6 monthsclinical assessment |

| Vavricka et al., 20114 | Uveitis (n = 50) | CD (n = 36) UC (n = 14) | Prospective cohort | 34 months | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion (ophthalmologist) | No exhaustive data | No data |

| Löfberg et al., 201226 | Iritis (n = 7) Uveitis (n = 3) | CD (n = 10) | OL prospective trial, multicentre | 20 weeks | Assess by investigator at baseline | ADA 40 mg (n = 10) | Assessed by investigator at each visit and Week 20; 5 cases at Week 20 |

| Barreiro-de-Acosta et al., 201227 | Uveitis (n = 1) | CD (n = 1) | OL prospective trial, single centre | 6 months | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | ADA 40 mg (n = 1) | Clinical assessment; 1 complete or partial response |

| Taleban et al., 201651 | Episcleritis/scleritis/uveitis (n = 124) | CD (n = 90) UC/IBD-U (n = 34) | Retrospective multicentre case control study | No data | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | No data | No data |

| Karmiris et al., 201628 | Episcleritis (n = 16) Uveitis (n = 38) | CD (n = 44) UC (n = 10) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | No data | No data |

| Vavricka et al., 201731 | Uveitis (n = 33) | CD (n = 29) UC (n = 4) | Retrospective multicentre study | 4 years | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | IFX, ADA or CZP (n = 25) | Clinical assessment; 72 to 88.9% response rate |

| Fleisher et al., 201835 | Uveitis (n = 1) | UC (n = 1) | Case report | 1 year | Clinical evaluation (ophthalmologist) | VDZ (n = 1)+ CS (n = 1) | Clinical assessment; 1 complete response |

| Feagan et al., 201937 | Iritis/uveitis (n = 26) | CD (n = 22) UC (n = 4) | Post hoc analyses of RCT | No data | Screening at baseline | VDZ (n = 21) | Assessed by investigator at each visit |

ADA: adalimumab; CD: Crohn's disease; CS: corticosteroid; CZP: certolizumab pegol; EIM: extra-intestinal manifestation; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; IFX: infliximab; NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug; OL: open label; RCT: randomised controlled trial; UC: ulcerative colitis; VDZ: vedolizumab.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

Thirteen studies included screening for PSC. A total of 3844 patients were recruited: 706 CD (18.3%), 3024 UC (78.7%) and 114 IBD-U (3%). Hepato-gastroenterologists were involved in the diagnostic approach of all studies (100%).4,28,31,52–61 The diagnosis was obtained through clinical examination (three studies, 23%) which included careful examination of symptoms and medical history,4,31,60 elevation of alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (11 studies, 84.6%)28,52–61 and bile duct imaging (MRI or endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography (ERCP), 11 studies, 84.6%).28,52–61 A liver biopsy was performed in 10 studies (77%).28,52–59,61 The biological drugs used for treatment were infliximab (two studies, 15.4%),31,57 adalimumab (two studies, 15.4%),31,57 vedolizumab (two studies, 15.4%)60,61 and certolizumab (1, 7.7%).31 Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) was also administered in six trials (46.1%).52,54–57,61 The response to treatment was evaluated in only four articles through clinical assessment and biological decrease of ALP levels.31,57,60,61 In all studies, biologics had no impact on the PSC course (Table 4).

Table 4.

Studies on primary sclerosing cholangitis.

| Study | IBD patients | Study design | Follow-up | Tools/method for diagnosis | Treatment for EIM | Efficacy assessment of EIM treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pardi et al., 200352 | UC (n = 52) | Retrospective study of single centre RCT | 166–189 person-years | ALP level + ERCP + biopsy | UDCA (n = 29) | No data |

| Moayyeri et al., 200553 | UC (n = 19) | Case control single centre study | 12.2 years (median) | ALP level + ERCP + biopsy | No data | No data |

| Claessen et al., 200954 | CD (n = 3) C (n = 24) | Retrospective multicentre study | 2.3–2.7 years (median) | ALP level + ERCP or biopsy | UDCA (n = 15) | No data |

| Vavricka et al., 20114 | CD (n = 4) UC (n = 13) | Prospective cohort | 34 months | Clinical exam + questionnaire at inclusion | No exhaustive data | No data |

| Eaton et al., 201155 | UC (n = 25) | Nested cohort study of multicentre RCT | 4.0 years (median) | ALP level + MRI or ERCP + biopsy | UDCA 28–30 mg/kg/day | No data |

| Navaneethan et al., 201256 | CD (n = 41) | Retrospective multicentre study | 17.3 years (median) | ALP level + MRI or ERCP + biopsy if clinical doubt | 5-ASA (n = 30), AZA (n = 3), MTX (n = 1), CS (n = 17) + UDCA (n = 36) | No data |

| Karmiris et al., 201628 | CD (n = 5) UC (n = 3) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | ALP level + MRI and/or biopsy | No data | No data |

| Franceschet et al., 201657 | CD (n = 10) UC (n = 38) IBD-U (n = 1) | Retrospective single centre study | 103.8 months (median) | ALP and γGT level + MRI or ERCP + biopsy (for small duct PSC) | 5-ASA (n = 42), AZA (n = 5), CS (n = 19), ADA (n = 2), IFX (n = 1) + UDCA (n = 49) | ALP and γGT level; No significant change of ALP and γGT level |

| Weismüller et al., 201758 | CD (n = 595) UC (n = 2761), IBD-U (113) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | ALP level + MRI or ERCP + biopsy | No data | No data |

| Vavricka et al., 201731 | CD (n = 6) UC (n = 4) | Retrospective multicentre study | 4 years | Diagnosis by gastroenterologist | IFX, ADA or CZP | Clinical and biological assessment |

| Park et al., 201859 | UC (n = 18) | Retrospective multicentre study | No data | ALP level + MRI or ERCP + biopsy | No data | No data |

| Christensen et al., 201860 | CD (n = 16) UC (n = 18) | Retrospective multicentre study | 9 months (median) | Clinical + ALP level + MRI or ERCP | VDZ (n = 34) | ALP level; No significant change of ALP level |

| Caron et al., 201961 | CD (n = 26) UC (n = 49) | Retrospective multicentre study | 6–54 weeks | ALP level + MRI + biopsy | VDZ (n = 75) + CS (n = 38), IS (n = 23), UDCA (n = 65) | ALP level; No significant change of ALP level |

5-ASA: 5-aminosalicylic acid; ADA: adalimumab; ALP: alkaline phosphatase; AZA: azathioprine; CD: Crohn's disease; CS: corticosteroid; CZP: certolizumab pegol; EIM: extra-intestinal manifestation; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; γGT: gamma-glutamyltransferase; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IBD-U: inflammatory bowel disease unclassified; IFX: infliximab; IS: immunosuppressant; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MTX: methotrexate; OL: open label; RCT: randomised controlled trial; UC: ulcerative colitis; UDCA: ursodeoxycholic acid; VDZ: vedolizumab.

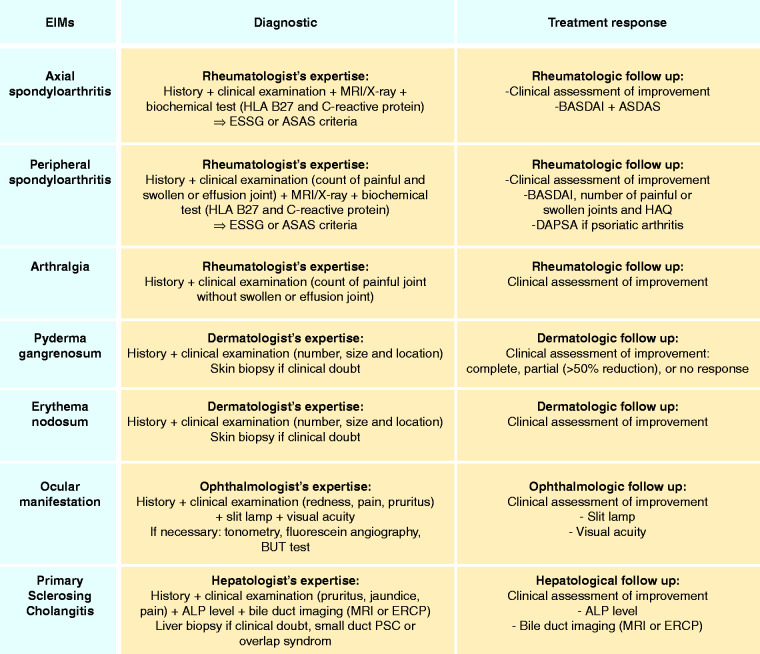

Recommendations for the assessment of EIMs

Proposed recommendations for the assessment of EIMs in upcoming IBD trials are reported in Figure 2. Based on our systematic literature review, recourse to specialist expertise is essential for both diagnosis and follow-up of each EIM. In patients with articular symptoms, the diagnostic approach should include clinical evaluation, biochemical tests (CRP and HLA B-27), and imaging (MRI/X-ray), while the response to therapy should be evaluated through clinical data and scores commonly used in clinical practice (BASDAI and ASDAS for axial spondyloarthritis,22,24,30,62,63 BASDAI, number of painful or swollen joints and HAQ for peripheral spondyloarthritis, Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) score for psoriatic arthritis).21,62,63 In cases of dermatologic manifestations the diagnosis should be clinical and a skin biopsy should be performed only in doubtful diagnoses.24,28,42–44,46–48 Follow-up should be based on clinical assessment and in patients with PG, response to therapy could be defined as a reduction >50% of symptoms.39,48 Ocular manifestations should be clinically investigated with the support of slit lamps and visual acuity tests. Similarly, ophthalmological follow-up should include clinical assessment, slit lamp and visual acuity tests.49,50 Further examinations (e.g. tonometry, fluorescein angiography and BUT test) should be adopted according to the symptoms reported by the patient.50 Finally, clinical, biochemical (ALP level), and bile duct imaging by MRI (currently preferred imagery) or ERCP should guide PSC assessment. Liver biopsy should not be systematically performed, but it should be reserved for doubtful situations, small duct PSC or overlap syndrome.4,28,52–59,61 In addition, clinical examination, ALP levels and MRI or ERCP should be used for the hepatological follow-up of PSC patients.31,57,60,61

Figure 2.

Proposed recommendations.

ALP: alkaline phosphatase; ASAS: Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society; BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP: C-reactive protein; DAPSA: Disease Activity in PSoriatic Arthritis; EIM: extraintestinal manifestation; ERCP: endoscopic retrograde cholangio-pancreatography; ESSG: European Spondylarthropathy Study Group; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PSC: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

Discussion

We investigated the diagnostic assessment of rheumatological, dermatological, ophthalmological and gastroenterological manifestations in approximately 8000 IBD patients. EIMs were diagnosed by dedicated specialists in percentages ranging from 60% for peripheral spondyloarthritis to 100% for PSC. The diagnostic approach was mainly based on clinical evaluation4,18–25,27–51,60 even if a considerable percentage of patients underwent biochemical and imaging tests.4,19,23–25,27–30,42–44,46–50,52–61 TNF inhibitors were the main biologic drugs for the treatment of EIMs and the response to therapy was primarily assessed through clinical data. Importantly, anti-TNF agents were confirmed to be effective in patients with EIMs, achieving a clinical response in over 50% of cases (except for PSC).18–20,22–24,26,27,30,31,38–45,47,57 These data are in line with a previous study, demonstrating the efficacy of anti-TNFs for musculoskeletal, cutaneous and ocular manifestations of IBD.8 Vedolizumab efficacy was evaluated in only eight articles (mainly case reports), preventing definitive conclusions from being drawn. However, in a recent systematic review no strong evidence supported the efficacy of vedolizumab for pre-existing EIMs, although its use could play a role in reducing the occurrence of new events.11 Only one study reported the efficacy of ustekinumab48 and no article on tofacitinib met our inclusion criteria, suggesting the lack of data in this field and the need for further studies. In 2016, a European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization consensus64 provided guidelines for diagnosis of IBD patients with EIMs, but no mention was made regarding follow-up and evaluation of the response to therapy. Based on the results of our research, we have proposed recommendations for evaluation and follow-up of each EIM. In the absence of clear guidelines, the approach to be used should be based on the most frequent management and all patients with EIMs should be referred to the dedicated specialist.

Regarding strengths, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review specifically designed to evaluate the diagnostic approach of EIMs in IBD patients. Secondly, the high number of studies and patients included are another relevant strength of our work. Thirdly, we adopted strict inclusion criteria, and study selection and data extraction were performed through the combined work of two authors who operated independently, reducing the risk of errors. Fourthly, more than 50% of the included studies were high quality studies according to globally accepted assessment scores such as the NOS and Jadad scores. On the other hand, several limitations must also be reported. First of all, there was a lack of standardised approach for EIM evaluation. In fact, the clinical characteristics leading to the diagnosis were rarely specified and the diagnostic accuracy could be questionable depending on the experience of the individual specialist. In addition, the analysed studies were heterogeneous as they included a wide variety of designs (e.g. randomised and open label trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and case reports) and there was no commonly accepted definition to assess the responses to different therapies, making data interpretation and comparison difficult. Finally, details of the clinical assessment of EIMs were not reported in the majority of the selected studies, probably due to their retrospective design preventing them from specifying if the evaluation of EIMs was performed before or after the IBD diagnosis and defining if this assessment had an impact on disease outcomes.

In conclusion, EIMs are challenging conditions and require the collaboration of dedicated specialists, from the dermatologist to the ophthalmologist, from the rheumatologist to the hepatologist according to the type of symptom, to guarantee the best management of these patients. In this context, it is essential that international expert organizations provide clear statements to homogenise and standardise the evaluation of IBD patients with EIMs. This consensus meeting will also clarify the role of imaging, such as ultrasound, in assessing EIMs.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ueg-10.1177_2050640620950093 for Assessment of extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and a proposed guide for clinical trials by Lucas Guillo, Ferdinando D’Amico, Mélanie Serrero, Karine Angioi, Damien Loeuille, Antonio Costanzo, Silvio Danese and Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet in United European Gastroenterology Journal

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Carmen Correale for her editorial assistance. The following author contributions were made: LG, FDA and MS wrote the article. LPB conceived the study. SD, KA, DL, AC and LPB critically revised the manuscript. The manuscript was approved by all authors.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: L Guillo, F D’Amico, M Serrero, K Angioi, D Loeuille and A Costanzo declare no conflict of interest. S Danese has served as a speaker, consultant, and advisory board member for Schering-Plough, AbbVie, Actelion, Alphawasserman, AstraZeneca, Cellerix, Cosmo Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Genentech, Grunenthal, Johnson and Johnson, Millenium Takeda, MSD, Nikkiso Europe GmbH, Novo Nordisk, Nycomed, Pfizer, Pharmacosmos, UCB Pharma and Vifor. L Peyrin-Biroulet has served as a speaker, consultant and advisory board member for Merck, Abbvie, Janssen, Genentech, Mitsubishi, Ferring, Norgine, Tillots, Vifor, Hospira/Pfizer, Celltrion, Takeda, Biogaran, Boerhinger-Ingelheim, Lilly, HAC- Pharma, Index Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Sandoz, Forward Pharma GmbH, Celgene, Biogen, Lycera, Samsung Bioepis and Theravance.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Literature review and medical writing support were funded by Arena Pharmaceuticals. Arena Pharmaceuticals was offered the opportunity to review the article but did not provide any additional comment and the manuscript was solely decided by the authors.

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel J-F, et al. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017; 389: 1741–1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 2017; 389: 1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ott C, Schölmerich J. Extraintestinal manifestations and complications in IBD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10: 585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vavricka SR, Brun L, Ballabeni P, et al. Frequency and risk factors for extraintestinal manifestations in the Swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zippi M, Corrado C, Pica R, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in a large series of Italian inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20: 17463–17467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Veloso FT, Carvalho J, Magro F. Immune-related systemic manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. A prospective study of 792 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol 1996; 23: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barreiro-de Acosta M, Iglesias-Rey M, Lorenzo A, et al. Influence of extraintestinal manifestations in health-related quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. J Crohns Colitis 2013; 7: S266–S267. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Van Assche G, Gómez-Ulloa D, et al. Systematic review of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15: 25–36.e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barrie A, Regueiro M. Biologic therapy in the management of extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007; 13: 1424–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vavricka S, Scharl M, Gubler M, et al. Biologics for extraintestinal manifestations of IBD. Curr Drug Targets 2014; 15: 1064–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chateau T, Bonovas S, Le Berre C, et al. Vedolizumab treatment in extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. J Crohns Colitis 2019; 10: 1569–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Armuzzi A, Ardizzone S, Biancone L, et al. Ustekinumab in the management of Crohn’s disease: Expert opinion. Dig Liver Dis 2018; 50: 653–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegmund B. Janus Kinase inhibitors in the New Treatment Paradigms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis 2020; 14: S761–S766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1 (updated March 2011). Cochrane, 2011. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. 2000 http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed on March 2020.

- 17.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996; 17: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van den Bosch F, Kruithof E, De Vos M, et al. Crohn’s disease associated with spondyloarthropathy: Effect of TNF-alpha blockade with infliximab on articular symptoms. Lancet 2000; 356: 1821–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ellman MH, Hanauer S, Sitrin M, et al. Crohn’s disease arthritis treated with infliximab: An open trial in four patients. J Clin Rheumatol 2001; 7: 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herfarth H, Obermeier F, Andus T, et al. Improvement of arthritis and arthralgia after treatment with infliximab (Remicade) in a German prospective, open-label, multicenter trial in refractory Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 2688–2690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reinisch W, Miehsler W, Dejaco C, et al. An open-label trial of the selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor, rofecoxib, in inflammatory bowel disease-associated peripheral arthritis and arthralgia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003; 17: 1371–1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Generini S, Giacomelli R, Fedi R, et al. Infliximab in spondyloarthropathy associated with Crohn’s disease: An open study on the efficacy of inducing and maintaining remission of musculoskeletal and gut manifestations. Ann Rheum Dis 2004; 63: 1664–1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufman I, Caspi D, Yeshurun D, et al. The effect of infliximab on extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Rheumatol Int 2005; 25: 406–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rispo A, Scarpa R, Di Girolamo E, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Scand J Rheumatol 2005; 34: 387–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Conti F, Borrelli O, Anania C, et al. Chronic intestinal inflammation and seronegative spondyloarthropathy in children. Dig Liver Dis 2005; 37: 761–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Löfberg R, Louis EV, Reinisch W, et al. Adalimumab produces clinical remission and reduces extraintestinal manifestations in Crohn’s disease: Results from CARE. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2012; 18: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barreiro-de-Acosta M, Lorenzo A, Domínguez-Muñoz JE. Efficacy of adalimumab for the treatment of extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2012; 104: 468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karmiris K, Avgerinos A, Tavernaraki A, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of extra-intestinal manifestations in a large cohort of Greek patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016; 10: 429–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landi M, Maldonado-Ficco H, Perez-Alamino R, et al. Gender differences among patients with primary ankylosing spondylitis and spondylitis associated with psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease in an IberoAmerican spondyloarthritis cohort. Medicine 2016; 95: e5652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luchetti MM, Benfaremo D, Ciccia F, et al. Adalimumab efficacy in enteropathic spondyloarthritis: A 12-mo observational multidisciplinary study. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23: 7139–7149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vavricka SR, Gubler M, Gantenbein C, et al. Anti-TNF treatment for extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in the Swiss IBD Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017; 23: 1174–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tadbiri S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Serrero M, et al. Impact of vedolizumab therapy on extra-intestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A multicentre cohort study nested in the OBSERV-IBD cohort. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orlando A, Orlando R, Ciccia F, et al. Clinical benefit of vedolizumab on articular manifestations in patients with active spondyloarthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: e31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sarmiento-Aguilar A. Joint involvement in Mexican patients with ulcerative colitis: A hospital-based retrospective study. Clin Rheumatol 2018; 37: 677–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleisher M, Marsal J, Lee SD, et al. Effects of vedolizumab therapy on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63: 825–833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Macaluso FS, Orlando R, Fries W, et al. The real-world effectiveness of vedolizumab on intestinal and articular outcomes in inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Liver Dis 2018; 50: 675–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ, Colombel J-F, et al. Incidence of arthritis/arthralgia in inflammatory bowel disease with long-term vedolizumab treatment: Post hoc analyses of the GEMINI Trials. J Crohns Colitis 2019; 13: 50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan MH, Gordon M, Lebwohl O, et al. Improvement of pyoderma gangrenosum and psoriasis associated with Crohn disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody. Arch Dermatol 2001; 137: 930–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ljung T, Staun M, Grove O, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum associated with Crohn disease: Effect of TNF-alpha blockade with infliximab. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002; 37: 1108–1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regueiro M, Valentine J, Plevy S, et al. Infliximab for treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 1821–1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapienza MS, Cohen S, Dimarino AJ. Treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 1454–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MGS, Shetty A, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2006; 55: 505–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baglieri F, Scuderi G. Therapeutic hotline. Infliximab for treatment of resistant pyoderma gangrenosum associated with ulcerative colitis and psoriasis. A case report. Dermatol Ther 2010; 23: 541–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashi H, Kuwabara C, Tarumi K, et al. Successful treatment with infliximab for refractory pyoderma gangrenosum associated with inflammatory bowel disease. J Dermatol 2012; 39: 576–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Argüelles-Arias F, Castro-Laria L, Lobatón T, et al. Characteristics and treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2013; 58: 2949–2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weizman A, Huang B, Berel D, et al. Clinical, serologic, and genetic factors associated with pyoderma gangrenosum and erythema nodosum in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20: 525–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perricone G, Vangeli M. Pyoderma gangrenosum in ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2018; 379: e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Risi-Pugliese T, Seksik P, Bouaziz J-D, et al. Ustekinumab treatment for neutrophilic dermatoses associated with Crohn’s disease: A multicenter retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 781–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yilmaz S, Aydemir E, Maden A, et al. The prevalence of ocular involvement in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 1027–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Felekis T, Katsanos K, Kitsanou M, et al. Spectrum and frequency of ophthalmologic manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A prospective single-center study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taleban S, Li D, Targan SR, et al. Ocular manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease are associated with other extra-intestinal manifestations, gender, and genes implicated in other immune-related traits. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10: 43–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pardi DS, Loftus EV, Kremers WK, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid as a chemopreventive agent in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 889–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moayyeri A, Daryani NE, Bahrami H, et al. Clinical course of ulcerative colitis in patients with and without primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005; 20: 366–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Claessen MMH, Lutgens MWMD, van Buuren HR, et al. More right-sided IBD-associated colorectal cancer in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009; 15: 1331–1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eaton JE, Silveira MG, Pardi DS, et al. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid is associated with the development of colorectal neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1638–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navaneethan U, G K Venkatesh P, Lashner BA, et al. Severity of primary sclerosing cholangitis and its impact on the clinical outcome of Crohn’s disease. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6: 674–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Franceschet I, Cazzagon N, Del Ross T, et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with inflammatory bowel disease: An observational study in a Southern Europe population focusing on new therapeutic options. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016; 28: 508–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Weismüller TJ, Trivedi PJ, Bergquist A, et al. Patient age, sex, and inflammatory bowel disease phenotype associate with course of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 2017; 152: 1975–1984.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park YE, Cheon JH, Park JJ, et al. Risk factors and clinical courses of concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: A Korean multicenter study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2018; 33: 1497–1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Christensen B, Micic D, Gibson PR, et al. Vedolizumab in patients with concurrent primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease does not improve liver biochemistry but is safe and effective for the bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 753–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caron B, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Pariente B, et al. Vedolizumab therapy is ineffective for primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: A GETAID multicentre cohort study. J Crohns Colitis 2019; 13: 1239–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smolen JS, Schöls M, Braun J, et al. Treating axial spondyloarthritis and peripheral spondyloarthritis, especially psoriatic arthritis, to target: 2017 Update of recommendations by an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77: 3–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 978–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Harbord M, Annese V, Vavricka SR, et al. The first European evidence-based consensus on extra-intestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10: 239–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ueg-10.1177_2050640620950093 for Assessment of extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel diseases: A systematic review and a proposed guide for clinical trials by Lucas Guillo, Ferdinando D’Amico, Mélanie Serrero, Karine Angioi, Damien Loeuille, Antonio Costanzo, Silvio Danese and Laurent Peyrin-Biroulet in United European Gastroenterology Journal