Abstract

Background

Determining the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus is important for defining screening strategies. We aimed to synthesize the available data, determine Barrett’s esophagus prevalence, and assess variability.

Methods

Three databases were searched. Subgroup, sensitivity, and meta-regression analyses were conducted and pooled prevalence was computed.

Results

Of 3510 studies, 103 were included. In the general population, we estimated a prevalence for endoscopic suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus of (a) any length with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia as 0.96% (95% confidence interval: 0.85–1.07), (b) ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia as 0.96% (95% confidence interval: 0.75–1.18) and (c) for any length with histologic confirmation of columnar metaplasia as 3.89% (95% confidence interval: 2.25–5.54) . By excluding studies with high-risk of bias, the prevalence decreased to: (a) 0.70% (95% confidence interval: 0.61–0.79) and (b) 0.82% (95% confidence interval: 0.63–1.01). In gastroesophageal reflux disease patients, we estimated the prevalence with afore-mentioned criteria to be: (a) 7.21% (95% confidence interval: 5.61–8.81) (b) 6.72% (95% confidence interval: 3.61–9.83) and (c) 7.80% (95% confidence interval: 4.26–11.34). The Barrett’s esophagus prevalence was significantly influenced by time period, region, Barrett’s esophagus definition, Seattle protocol, and study design. There was a significant gradient East-West and North-South. There were minimal to no data available for several countries. Moreover, there was significant heterogeneity between studies.

Conclusion

There is a need to reassess the true prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus using the current guidelines in most regions. Having knowledge about the precise Barrett’s esophagus prevalence, diverse attitudes from educational to screening programs could be taken.

Keywords: Barrett metaplasia, epidemiology, prevalence, worldwide

Introduction

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC) has been increasing.1 The poor prognosis of EAC has focused interest on Barrett’s esophagus (BE). Identification of BE with treatment of dysplasia is important to prevent invasive cancer. On the other hand, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been associated with an increased risk of BE. Despite recommendations against population-based screening, the majority of guidelines recommend considering screening of chronic GERD patients. However, 50% of EAC patients report no previous GERD.2–5 Therefore, understanding the epidemiology of BE is difficult because the majority remain undiagnosed. Indeed, the prevalence of BE is unknown: some studies estimate a 15% prevalence in chronic GERD patients and 1–2% in the general population.6 The BE prevalence (priori probability) is important to define and evaluate screening strategy.

BE has been an area of controversy.1–3 Its definition and practice have varied along time and across the world.7,8 The Prague classification, described in 2006, has improved BE diagnosis and increased reliability in reporting.9 While the European, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and American College of Gastroenterology define BE as intestinal metaplasia (IM) lining in the distal esophagus with a minimum length of 1 cm, the American Gastroenterological Association defines it as any extent of intestinal metaplasia and the British Society as any columnar metaplasia (CM) (fundic type, cardiac type, and intestinal type) lining in the distal esophagus with a minimum length of 1 cm.2–5

We aimed to synthesize the data of all studies assessing BE prevalence and determine its prevalence. We also aimed to assess the variability of BE prevalence according to the definition, geographical region, time period, and method used in order to identify the best methodology to determine it.

Methods

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic review according to the PRISMA guidelines. The research question was defined using the PICO acronym (P-population, I-intervention, C-comparator, O-outcome): what is the BE prevalence (O) in different settings (P) and which are the methodologies used (I). A sensitive search in PubMed, Scopus and Web of Knowledge was performed using the following query: “(prevalence(Title) OR epidemiolog*(Title) OR incidence(Title) OR risk(Title) OR screen*(Title)) AND (Barrett’s esophagus(Title/Abstract) OR Barrett(Title/Abstract) OR columnar-lined esophagus(Title/Abstract)).”

Selection of manuscripts

Inclusion criteria were original full-text articles published up to September 2018 and addressing BE in general and the GERD population, that met the globally accepted criteria for BE (endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) with or without histologic confirmation of any CM or IM) and with a sample size of ≥100 individuals. The general population was defined as any population with or without gastrointestinal symptoms or with or without indication for esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Exclusion criteria were reviews, case-reports, case-control studies with BE cases, and non-English, non-French, non-Spanish, and non-Portuguese language. An attempt to contact corresponding authors was made when the full text was not available. When similar data was identified, we included the most recent report.

After all references (n = 3510) were imported and duplicated records were discarded, the records (n = 1531) were screened by title and abstract by two independent investigators (gastroenterology trainees). Concordance between the reviewers was measured by proportion of agreement and k-statistics achieving a good agreement (83% of agreement). Full-text eligibility was done by the same investigators. Conflicts were resolved through discussion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

A data extraction sheet was developed. Data were extracted independently by both investigators and then cross-checked by one. Studies were divided into the general and GERD population. The pooled BE prevalence was estimated according to its definition: ESBE with histologic confirmation of IM (any length or ≥1 cm of length), ESBE with histologic confirmation of CM (any length or ≥1 cm of length) and ESBE only (any length or ≥1 cm of length). The group “ESBE any length” included the studies from the group “ESBE≥1 cm of length.” For studies assessing ESBE with histologic confirmation of IM, sources of variability were evaluated.

The appraisal of study quality was done independently by both investigators using the STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist and the NewCastle-Ottawa Scale. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Statistical analysis

The pooled prevalence was calculated using the random-effect model. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed by I2 statistic (<30%, 30–60%, 60–75% and >75% suggestive of low, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively). We explored sources of heterogeneity by subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and meta-regression. We used the z-test for the logit of the prevalence to examine the impact of different factors (year of publication, geographical setting, sample size, percentage of male, type of sampling, Seattle protocol, and ESBE length) on estimates. After logit transformation, we analyzed publication bias using funnel plot and Egger’s test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The STATA software was used.

Results

Study characteristics

After screening, 175 records were assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). We did not have access to 3% of these articles, with 66% unrecoverable records dating before 2006. We finally included 80 studies assessing BE prevalence in the general population (ESBE with IM: 49, ESBE with CM: 8 and ESBE only: 23) and 23 in the GERD population (ESBE with IM: 17, ESBE with CM: 1 and ESBE only: 5). Characteristics of studies are depicted in Table 1.10–112 Of the 80 studies in the general population, 12 studies performed a subgroup analysis in GERD patients: 11 studies were included in the GERD analysis,10,15,19,23,27,30,32,42,43,56,79 but one was not included due to the small sample (n = 26). There was considerable heterogeneity among studies. There was no data available regarding BE prevalence in the general and GERD populations for the majority of countries (Figures 1 and 2, Supplementary Material).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection. (*51 articles only published as abstracts). BE: Barrett’s esophagus.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies.

|

General population | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study first author (year) | Country | Sampling | Sample size | Male (%) | Mean age | Caucasian (%)/African-American (%)/Asian (%) | Quality of endoscopy reported ? | How EGJ was defined ? | Seattle protocol used? | Esophagitis present during BE diagnosis? | Prevalence (%) |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Crews (2016)10 | USA | Prospective population cohort | 205 | 46 | 70 | 98.5/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Unknown | No | 7.8 |

| Jacobson (2011)11 | USA | Women that underwent EGD | 20,167 | 0 | 30–55 (range) | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.73 |

| Jung (2011)12 | USA | Prospective population cohort | 182,605 | – | 63 | 89/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Unknown | Yes | 0.22 |

| Connor (2004)13 | USA | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent EGD | 264 | 95 | 57 | 73/22/- | Yes | Gastric folds | Unknown | Yes | 6.1 |

| Pascarenco (2014)14 | Romania | Patients that underwent EGD | 286 | 52.4 | 59.9 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 6.6 |

| Kuo (2010)15 | Taiwan | Patients that underwent EGD | 736 | 51 | 50.5 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | 1.8 |

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Rex (2003)16 | USA | Patients that underwent colonoscopy | 961 | 59.5 | 59 | 78/20.3/- | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | No | 3.3 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Khoury (2012)17 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 7308 | 36.4 | 57.3 | 83/14/- | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 1.57 |

| Kula (2007)18 | Poland | Patients that underwent EGD | 6326 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 1.1 |

| Elizondo (2017)19 | Mexico | Patients that underwent EGD | 500 | 37.6 | 54 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | No | 1.8 |

| Kim (2007)20 | South Korea | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 70,103 | – | 51 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Unknown | Yes | 0.22 |

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Gerson (2002)21 | USA | Asymptomatic patients that underwent colonoscopy | 110 | 91,8 | 61 | 73/14/4 | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 25 |

| Gerson (2009)22 | USA | Asymptomatic women that underwent colonoscopy or EGD before bariatric surgery | 126 | 0 | 58 (colonoscopy)42 (bariatric) | 72/2/20 (colonoscopy) 71/19/2 (bariatric) | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 6 |

| Zagari (2008)23 | Italy | Prospective population cohort | 1033 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1.3 |

| Zaninotto (2001)24 | Italy | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent their 1st EGD | 240 | 51.7 | 56 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Unknown | 0.83 |

| GOSPE (1991)25 | Italy | Patients that underwent EGD | 14,898 | 57.3 | 57 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | 0.46 |

| Katsinelos (2013)26 | Greece | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent an EGD | 1990 | 52 | 47.48 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 3.8 |

| Dina (2015)27 | Romania | Patients that underwent EGD | 1261 | 53 | 57 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 2.85 |

| Jonaitis (2011)28 | Lithuania | Patients n with upper gastrointestinal symptoms that underwent EGD | 4032 | 39.6 | 45.13 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 0.82 |

| Fagundes (2003)29 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 1276 | – | – | 100/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.63 |

| Csendes (2000)30 | Chile | Patients with dyspepsia | 306 | 32.7 | 48 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 0 |

| Amano (2006)31 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 1668 | 57.2 | 63.5 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 6.4 |

| Peng (2009)32 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 2580 | 49.5 | 45 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 1.05 |

| Zhang (2012)33 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 139,416 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 0,17 |

| Wong (2002)34 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 16,606 | – | 67.4 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 0.06 |

| Yeh (1997)35 | Taiwan | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 464 | 43.3 | 47 | −/−/96 | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1.98 |

| Khamechian (2013)36 | Iran | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent their 1st EGD | 1144 | – | 45.2 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | 3.7 |

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Chak (2014)37 | USA | Hospital cohort | 177 | 100 | 58 | 41/58/- | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4.5 |

| Ward (2006)38 | USA | Patients that underwent colonoscopy | 300 | 54 | 71.8 (median) | 83/14/2 | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 16.7 |

| Spechler (1994)39 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 156 | 48.7 | 53 | 90/7/1 | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 10 |

| van Zanten (2006)40 | Canada | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent their 1st EGD | 1040 | 95/−/− | No | Unknown | No | Unknown | 2.4 | ||

| Johansson (2005)41 | Sweden | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 769 | 43 | 53 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 3.8 |

| Ronkainen (2005)42 | Sweden | Population sample | 1000 | 49 | 53.5 (median) | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 1.6 |

| Voutilaine (2000)43 | Finland | Patients that underwent EGD | 1128 | 42 | 47 (median) | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.98 |

| de Mas (1999)44 | Germany | Patients that underwent EGD | 370 | 48.4 | 58.7 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 10 |

| Freitas (2008)45 | Brazil | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 104 | 49 | 65 | 85.6/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 3.8 |

| Cárdenas (2010)46 | Peru | Patients that underwent EGD | 11,970 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | 0.25 |

| Chacaltana (2009)47 | Peru | Population cohort | 2273 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.48 |

| Toruner (2004)48 | Turkey | Patients that underwent EGD | 395 | 43.3 | 57 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 7.4 |

| Lee (2011)49 | Malaysia | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 1895 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 0.37 |

| Rosaida (2004)50 | Malaysia | Patients with dyspepsia that underwent EGD | 1000 | 44.2 | 51.1 | −/−/68.9 | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 2 |

| Xiong (2010)51 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 2022 | 52 | 46.97 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 1.04 |

| Lee (2003)52 | South Korea | Patients n with upper gastrointestinal symptoms that underwent EGD | 1553 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Intramucosal vessels | No | Yes | 0.32 |

| Fireman (2001)53 | Israel | Patients that underwent EGD | 112 | 51.8 | 49.8 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | 2.7 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Bersentes (1998)54 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 1541 | 98 | 65 | 75.9/1.7/<0.1 | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 12.4 |

| Robles (1995)55 | Spain | Patients that underwent EGD | 5303 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.53 |

| De Carli (2017)56 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 5996 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.78 |

| Peña (2005)57 | Mexico | Patients that underwent EGD | 4947 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.26 |

| Yilmaz (2006)58 | Turkey | Patients that underwent EGD | 18,766 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | 0.4 |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) with histologic confirmation of columnar metaplasia | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Siwiec (2012)59 | USA | Volunteers | 150 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 3.3 |

| Connio (2001)60 | USA | Database with EGD | Unknown | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.08 |

| Cameron (1990)61 | USA | Autopsy with endoscopy performed in 83% of the autopsy esophagus | 733 | 61 | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 0.95 |

| Cameron (1992)62 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 51,311 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 0.83 |

| Coleman (2011)63 | North Ireland | Patients that underwent EGD | 197,635 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4.7 |

| Ford (2004)64 | UK | Patients that underwent EGD | 20,417 | 48 | 56 | 69/5/26 | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 3.6 |

| GOSPE (1991)25 | Italy | Patients that underwent EGD | 14,898 | 57.3 | 57 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | No | Yes | 0.58 |

| Taghipour-Zahir (2012)65 | Iran | Patients that underwent EGD | 681 | 62.7 | 62.04 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 18.86 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Andreollo (1997)66 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 2381 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 2.57 |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Yamagishi (2008)67 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 6307 | 49.2 | 62.7 | −/−/− | No | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Unknown | 1.7 |

| Azuma (2000)68 | Japan | Hospital cohort | 650 | 79 | 52.6 | −/−/− | No | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Unknown | 3.12 |

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Zullo (2014)69 | Italy | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 1054 | 37 | 57.5 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 1.6 |

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Akiyama (2010)70 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD with intact stomach | 160 | 75.6 | 68 (median) | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | NA | Unknown | 47.5 |

| Alexandropoulou (2012)71 | UK | National database | Unknown | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 1.29 |

| Blankenstein (2005)72 | UK | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 21,899 | 50 | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 2.25 |

| Loffeld (2003)73 | Netherlands | Patients that underwent 1st EGD | 11,691 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 2.4 |

| López-Colombo (2018)74 | Mexico | Patients that underwent EGD | 239 | 45.6 | 53 | −/−/− | No | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Unknown | 23 |

| Shimoyama (2012)75 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 832 | 40.7 | 67.6 | −/−/− | Yes | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Yes | 22.1 |

| Okita (2008)76 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 5338 | 60 | 69 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | NA | Unknown | 37.6 |

| Fujiwara (2003)77 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 548 | 54 | 57.3 | −/−/− | Yes | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Unknown | 12.2 |

| Niu (2012)78 | China | Population cohort | 1995 | 72 | 44 | 0/0/100 | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 2.8 |

| Zou (2011)79 | China | Population sample | 1029 | 42.4 | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Yes | 1.8 |

| Tseng (2008)80 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 19,812 | 55.2 | 51.6 | 0/0/100 | Yes | Gastric folds | NA | Yes | 0.28 |

| Park (2009)81 | Korea | Patients that underwent EGD | 25,536 | 59.5 | 46.7 | 0/0/100 | No | NA | Yes | 3.4 | |

| Choi (2002)82 | Korea | Patients that underwent EGD | 847 | 45.1 | 48.7 | −/−/− | Yes | Intramucosal vessels | NA | Yes | 17 |

| Masri (2015)83 | Lebanon | Patients that underwent EGD | 16,787 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 1.3 |

| Rezailashkajani (2007)84 | Iran | Patients that underwent EGD | 501 | 39 | 44.7 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Yes | 0.2 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Smith (2009)85 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 135 | – | – | 12.6/1/- | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 3.6 |

| Masclee (2014)86 | Netherlands | National database | 1,487,191 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 0.15 |

| Alcedo (2009)87 | Spain | Patients that underwent EGD | 58,190 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Yes | 0.66 |

| Fujimoto (2013)88 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 18,792 | 70.8 | 54.2 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 7.9 |

| Akiyama (2009)89 | Japan | Patients that underwent EGD | 846 | 53 | 66 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | NA | Yes | 43 |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Crews (2016)10 | USA | Prospective population cohort | 68 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Unknown | No | 8.8 |

| Mathew (2011)90 | India | Patients with symptoms | 278 | 53.6 | 39.97 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | No | 8.99 |

| Kuo (2010)15 | Taiwan | Patients that underwent EGD | 344 | 55.5 | 49.8 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | 3.8 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Elizondo (2017)19 | Mexico | Patients that underwent EGD | 125 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | No | 7.2 |

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Romero (2002)91 | USA | Patients with GERD symptoms and no family relatives with BE | 100 | 59 | 47 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| Zagari (2015)23 | Italy | Prospective population cohort | 458 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1.5 |

| Dina (2015)27 | Romania | Patients that underwent EGD | 527 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4.93 |

| Fagundes (2003)29 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 326 | – | – | 100/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 2.5 |

| Csendes (2003)92 | Chile | Patients that underwent EGD | 1480 | – | 54.5 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 13.65 |

| Csendes (2000)30 | Chile | Patients with symptoms | 376 | 41.5 | 49 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 11.4 |

| Sharifi (2014)93 | Iran | Patients with symptoms | 736 | 55.8 | 48.9 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Yes | 4.6 |

| Fouad (2009)94 | Egypt | Patients with symptoms | 1000 | 76.4 | 38.81 | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | No | 7.3 |

| Zhang (2012)95 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 593 | 57.1 | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 4.6 |

| Peng (2009)32 | China | Patients that underwent EGD | 310 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Yes | 5.2 |

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Ramirez (2008)96 | USA | Patients with symptoms | 100 | 86 | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 27 |

| Ward (2006)38 | USA | Patients that underwent colonoscopy | 105 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Yes | Unknown | 19.8 |

| Jobe (2006)97 | USA | Patients with symptoms | 121 | 80 | 59 | 95/4/- | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 29.8 |

| Winters (1987)98 | USA | Patients with symptoms | 97 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | No | Unknown | 6.18 |

| Ronkainen (2011)99 | Sweden | Population cohort | 284 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Unknown | Unknown | Yes | 8.1 |

| Ronkainen (2005)42 | Sweden | Population sample | 399 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Yes | 2.3 |

| Voutilaine (2000)43 | Finland | Patients that underwent EGD | 248 | 52 | 56 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4 |

| Conio (1988)100 | Italy | Patients that underwent EGD | 102 | 55.9 | 30–83 (range) | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4.9 |

| Wani (2014)101 | India | Patients with symptoms | 378 | 66.7 | 48.15 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 2.38 |

| Yin (2012)102 | China | Patients with symptoms | 528 | – | – | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 6.06 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Chavalitdhamrong (2011)103 | USA | Patients that underwent esophageal capsule endoscopy | 502 | 54.9 | 54.2 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 1.19 |

| Banki (2005)104 | USA | Patients with symptoms | 796 | 58 | 52 | −/−/− | No | Gastric folds | Yes | Unknown | 26 |

| Spechler (2002)105 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 2477 | 48 | 58 | 87.8/10/2 | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 8.1 |

| De Carli (2017)56 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 1769 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 2.7 |

| Gado (2015)106 | Egypt | Patients that underwent EGD | 433 | 59 | 45 | −/−/− | Yes | Gastric folds | No | Unknown | 1.2 |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) with histologic confirmation of columnar metaplasia | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Siwiec (2012)59 | USA | Volunteers | 67 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 4.5 |

| Winters (1987)98 | USA | Patients with symptoms | 97 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | No | Unknown | 12.3 |

| Conio (1988)100 | Italy | Patients that underwent EGD | 102 | 55.9 | 30–83 (range) | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 11.8 |

| Arróspide (2003)107 | Peru | Patients that underwent EGD | 345 | 49.6 | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 5.8 |

| Endoscopic suspicion of BE (ESBE) | |||||||||||

| ESBE≥1 cm | |||||||||||

| ESBE irrespective of length | |||||||||||

| Prospective study | |||||||||||

| Lin (2018)108 | USA | Patients that underwent EGD | 73,535 | 48.2 | 53.8 | 80.9/4.2/1.8 | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 5.6 |

| Kulig (2004)109 | Germany, Austria, and Switzerland | Hospital based-cohort | 6215 | 53 | 54 | 99/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 11 |

| Pelechas (2013)110 | Greece | Patients with symptoms | 406 | 63.1 | 48.7 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 4.9 |

| Cross-sectional study | |||||||||||

| Abdul-Razzak (2007)111 | Jordan | Patients that underwent EGD | 100 | 50 | 37.62 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 4 |

| Zou (2011)79 | China | Population sample | 48 | – | – | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Yes | 2.1 |

| Retrospective study | |||||||||||

| Nassif (2012)112 | Brazil | Patients that underwent EGD | 207 | 34.78 | 47.43 | −/−/− | No | Unknown | NA | Unknown | 6.28 |

BE: Barrett’s esophagus; EGD: esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EGJ: means esophagogastric junction; ESBE: endoscopic suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus; GERD: gastroesophageal reflux disease; GOSPE: Gruppo Operativo per lo Studio delle Precancerosi dell’Esofago; NA: not applicable.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of all studies assessing the prevalence of endoscopic suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus (ESBE) any length with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia (IM) (a), of ESBE ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of IM (b), and of ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of columnar metaplasia (CM) (c) in general population.

BE prevalence according to various definitions

General population

The BE prevalence varied according to definition: 0.96% (95% confidence interval (CI95%): 0.85–1.07) for ESBE any length with IM, 0.96% (CI95%: 0.75–1.18) for ESBE ≥1 cm with IM, 3.89% (CI95%: 2.25–5.54) for ESBE any length with CM, 7.04% (CI95%: 6.35–7.74) for ESBE any length and 2.26% (CI95%: 0.90–3.61) for ESBE with ≥1 cm (Figure 2).

Regarding ESBE with IM, we analyzed the statistical outliers (Figure 2). Ward et al. (16.7% of BE prevalence) and Spechler et al. (10%) conducted studies in a population with a high prevalence of GERD. In the study of Spechler et al. and Pascarenco el al. (6.6%) esophagitis was present. Bersentes et al. (12.4%), Gerson et al. (2002) (20%) and Connor et al. (6.1%) conducted studies with a high percentage of males. In the study of Gerson et al. (2009) (6%), 50% of the population was obese/overweight. Bersentes et al., De Mas et al. (10%), Amano et al. (6.4%) and Toruner et al. (7.4%) did not consider ESBE≥1 cm. Crews et al. (7.8%) estimated BE prevalence by EGD and transnasal endoscopy in an older population. By excluding these outliers, the prevalence was: BE any length with IM – 0.70% (CI95%: 0.61–0.79); BE ≥1 cm with IM – 0.82% (CI95%: 0.63–1.01).10,13,14,21,22,31,38,39,44,48,54

GERD population

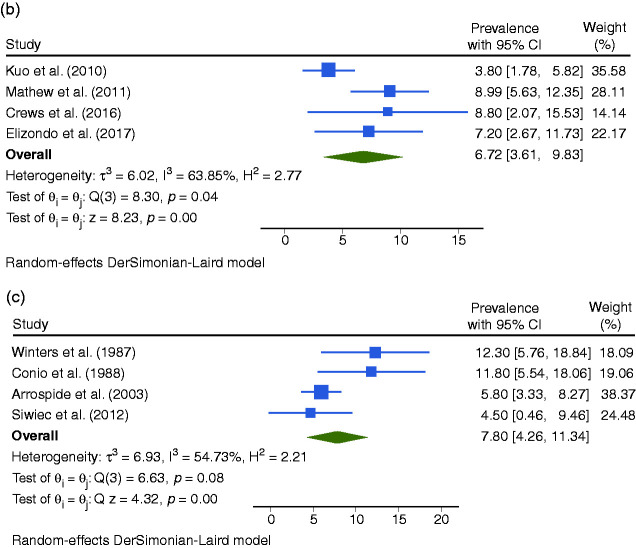

The BE prevalence varied based on the definition: 7.21% (CI95%: 5.61–8.81) for ESBE any length with IM, 6.72% (CI95%: 3.61–9.83) for ESBE ≥1 cm with IM, 7.80% (CI95%: 4.26–11.34) for ESBE any length with CM and 6.51% (CI95%: 3.34–9.68) for ESBE any length.

Regarding ESBE with IM, we analyzed the statistical outliers (Figure 3). Ward et al. (19.8% of BE prevalence) conducted a study in an older population. In the study of Jobe et al. (29.8%) and Ramirez et al. (27%) >80% were men. Banki et al. (26%) assessed patients that warrant evaluation for antireflux surgery. By excluding these studies, the pooled prevalence of ESBE any length with IM was 4.53% (CI95%: 3.46–5.60).38,96,97,104

Figure 3.

Forest plot of all studies assessing the prevalence of endoscopic suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus (ESBE) any length with histologic confirmation of intestinal metaplasia (IM) (a), of ESBE ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of IM (b), and of ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of columnar metaplasia (CM) (c) in the gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) population.

Variability in the prevalence of BE

Geographical setting

General population

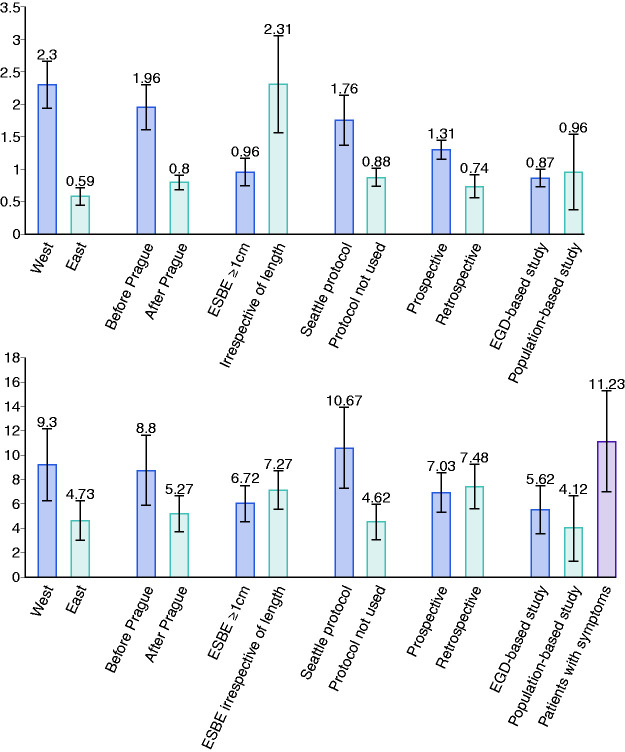

The pooled prevalence of BE in Western, Eastern and Latin American countries was 2.30% (CI95%: 1.94–2.65), 0.59% (CI95%: 0.45–0.73), and 0.51% (CI95%: 0.28–1.07) respectively (Figure 4). There was a North-South gradient in the West: in North was 2.97% (CI95%:2.44–3.50) and in South was 1.72% (CI95%:1.09–2.36).

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) in general population (a), and in gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) patients (b) for geographical setting, date of publication, length of endoscopic suspicion of Barrett’s esophagus (ESBE) considered, use of Seattle protocol, study design, and type of sampling.

GERD population

The pooled prevalence of BE in Western, Eastern, and Latin American countries was 9.30% (CI95%: 6.35–12.25), 4.73% (CI95%: 3.11–6.35) and 7.43% (CI95%: 2,50–8.81) respectively (Figure 4).

Time trends

General population

There was a temporal trend with the most recent studies reporting lower estimates especially in the West. Indeed, the BE prevalence was 0.80% (CI95%: 0.69–0.92) when considering only the studies published after 2006 (date of publications of Prague classification) while it was 1.96% (CI95%: 1.62–2.30) when considering only the studies published before 2006. This difference was also found in a subgroup analysis for Western (before: 4.05% (CI95%: 3.16–4.95) vs after: 1.71% (CI95%: 1.25–2.17)) and Eastern countries (before: 1.28% (CI95%: 0.81–1.74) vs after: 0.54% (CI95%: 0.45–0.73)) (Figure 4).

GERD population

Likewise, there was a temporal trend: 5.27% (CI95%: 3.79–6.76) when considering only the studies published after 2006 vs 8.80% (CI95%: 5.91–11.69) when considering only the studies published before 2006 (Figure 4).

Length of BE

General population

When comparing studies that considered ESBE with ≥1 cm with those that did not, the prevalence of BE was significantly different (0.96% (CI95%: 0.75–1.18) vs 2.31% (CI95%: 1.56–3.05)) (Figure 4).

GERD population

The prevalence of BE was similar between studies that considered ESBE ≥1 cm and studies that did not (6.72% (CI95%: 3.61–9.83) vs 7.27% (CI95%: 5.53–8.81)) (Figure 4).

Use of the Seattle protocol

General population

When comparing studies that used Seattle protocol with those that did not, the prevalence was significantly different (1.76% (CI95%: 0.85–1.07) vs 0.88% (CI95%: 0.74–1.02)) (Figure 4).

GERD population

When comparing studies that used Seattle protocol with those that did not, the prevalence was significantly different (10.67% (CI95%: 7.31–14.02) vs 4.62% (CI95%: 3.13–6.12))(Figure 4).

Study characteristics

General population

The studies with larger sample size, lower male percentage, and lower mean/median age had the lowest BE prevalence. Prospective studies estimated a higher BE prevalence than retrospective studies (1.34% (CI95%: 1.16–1.53) vs 0.74% (CI95%: 0.56–0.91)). When comparing studies that estimated BE prevalence in patients undergoing EGD and studies that estimated BE prevalence in population cohorts/sample (these studies proposed endoscopy to individuals from a cohort conducted for unrelated reasons to BE or GERD or from a population sample) there was no difference (0.96 (CI95%: 0.85–1.07) vs 0.87 (CI95%: 0.74–1.01)) (Figure 4).

GERD population

The studies with the larger sample size, lower percentage of males, and with lower mean/median age had a lower prevalence. The prevalence was similar between prospective and retrospective studies. There was no difference between studies that estimated BE prevalence in patients undergoing EGD and studies that estimated BE prevalence in population cohorts/sample. However, the BE prevalence significantly increased to 11.23% (CI95%: 7.04–15.41) if studies assessed patients with GERD (Figure 4).

Meta-regression

General population

The univariate analysis showed a significant relationship between the BE prevalence and the geographical setting, sample size, and percentage of males. Considering the univariate and the subgroup analysis, we included publication date, geographical setting, sample size, percentage of male, and ESBE≥1 cm as independent variables in a multivariate analysis. Although only sample size had a significant impact on BE prevalence (p<0.0001), 55.63% of cross-study variance could be explained by this model (R2 = 55.63%).

GERD population

The univariate analysis showed a significant relationship between pooled prevalence and the use of Seattle protocol. Considering the univariate and the subgroup analysis, we included year of publication, geographical setting, sample size, percentage of male, type of sampling, and Seattle protocol in a multivariate analysis. Although 64.96% of the variance inter-studies was explained by this model, only year of publication (p = 0.011) and type of sampling (p = 0.016) had a significant impact on BE prevalence.

Quality assessment

Among the 103 studies, 65% were at a high risk of bias due to sample characterization and 87% due to endoscopic practice (Supplementary Material Figure 3).

Publication bias

For the general population, the funnel plot and the Egger test (p = 0.1177) indicated low risk of bias. For the GERD population, although the funnel plot indicated low risk of bias, the p-value was 0.0016 with a z-statistic of -2.06 in the Egger test (Supplementary Material Figure 4).

Discussion

The poor prognosis of EAC has been focus attention to BE. Despite BE surveillance, EAC incidence has been rising, bringing into question whether the population at risk is being correctly identified. Indeed, the precise prevalence of BE is unknown.

This study is an important review assessing global BE prevalence according to the most recent guidelines and the first study assessing variability of BE prevalence due to BE definition, geographical region, time period, and methodology. We have found that there are no data available from the majority of the countries. In some countries, the estimations are higher than expected because of BE definition and methodology used (Supplementary Material Figures 1 and 2). We also found heterogeneity among the studies.

In the general population, we estimated a pooled prevalence of 0.96% (CI95%: 0.85–1.07) for ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of IM, 0.96% (CI95%: 0.75–1.18) for ESBE ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of IM and 3.89% (CI95%: 2.25–5.54) for ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of CM. By excluding studies with high risk of bias, the prevalence of ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of IM was 0.70% (CI95%: 0.61–0.79) and of ESBE ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of IM was 0.82% (CI95%: 0.63–1.01). Therefore, it would be necessary to perform endoscopy in 122 individuals of the general population for the diagnosis of one patient with BE. There is no difference in the prevalence between BE any length with IM and BE ≥1 cm with IM, because the first included the studies from the last group. Indeed, when comparing studies that considered ESBE with ≥1 cm with those that did not, the prevalence was significantly different (Figure 4). In GERD, we estimated a pooled prevalence of 7.21% (CI95%: 5.61–8.81) for ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of IM, 6.72% (CI95%: 3.61–9.83) for ESBE ≥1 cm of length with histologic confirmation of IM and, 7.80% (CI95%: 4.26–11.34) for ESBE any length with histologic confirmation of CM. The prevalence was significantly influenced by the date of publication, geographical setting, BE length, the use of Seattle protocol, and the study design. There was a significant gradient East-West and North-South of BE prevalence. By including studies prior to 2006, we found a temporal trend with the most recent studies reporting lower prevalence, particularly after Prague classification.9 Moreover, the presence of esophagitis was a source of bias, probably by making BE diagnosis difficult. The impact of ethnicity was not assessed since the studies did not estimate BE prevalence by ethnic group.

Shiota et al.113 conducted a systematic review of BE prevalence in Asia, estimating a BE prevalence of 1.3% (0.7–2.2) in the general population with high heterogeneity. This higher value might result from studies in high-risk patients and studies that diagnosed BE without IM confirmation. They also included studies that excluded patients with known BE (that estimated incidence). No study from this review was excluded in ours.113 Qumseya et al.114 have conducted a systematic review of 47 studies assessing BE prevalence in different risk populations. They included studies with less than 100 patients and studies that excluded patients with known BE. Moreover, the authors differentiate the prevalence of population without any risk factor (0.8%) from the prevalence of population with ≥50 years (6.7%). However, the majority of the studies included in the first group had a mean/median age higher than 50 years and the last group included studies with mean age of 45 years.114

The limitations of our analysis extend from the various biases within each study and the heterogeneity among studies impacting our meta-analysis. Although the BE prevalence varied based on the definition, we have attempted to provide precise estimates based on the population being evaluated (general vs GERD), BE length (any vs ≥1 cm), using Seattle protocol and geographical location.

Our findings confirm the need for well-conducted studies in order to accurately estimate BE prevalence and decrease heterogeneity. In the future, prospective population-based or EGD-based studies with a minimum sample size of 100 individuals and according to the most recent guidelines, namely using the definition of BE with ≥1 cm and histologic confirmation of IM, the Prague classification, the Seattle protocol, and in the absence of esophagitis, should be conducted.

Having knowledge about precise BE prevalence, we could draw more tailored screening strategies and ultimately assess their impact.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ueg-10.1177_2050640620939376 for The global prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus: A systematic review of the published literature by Inês Marques de Sá, Pedro Marcos, Prateek Sharma and Mário Dinis-Ribeiro in United European Gastroenterology Journal

Acknowledgements

The author contributions were as follows. IM: screening, data extraction, quality assessment, statistical analysis, and writing the manuscript; PM: screening, data extraction, and quality assessment; PS: guidance and review; MD: guidance and review.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Not applicable.

ORCID iD: Inês Marques de Sá https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8835-7183

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Dubecz A, Gall I, Solymosi N, et al. Temporal trends in long-term survival and cure rates in esophageal cancer: A SEER database analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: 443–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weusten B, Bisschops R, Coron E, et al. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy position statement. Endoscopy 2017; 49: 191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 111: 30–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fitzgerald RC, di Pietro M, Ragunath K, et al. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus Gut 2015; 63: 47–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spechler SJ, Sharma P, Souza RF, et al. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on the management of Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011; 140: 1084–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuipers EJ, Spaander MC. Natural history of Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci 2018; 63: 1997–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh M, Gupta N, Gaddam S, et al. Practice patterns among U.S. gastroenterologists regarding endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Endosc 2013; 78: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curvers WL, Peters FP, Elzer B, et al. Quality of Barrett’s surveillance in The Netherlands: A standardized review of endoscopy and pathology reports. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20: 601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett’s esophagus: The Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology 2006; 131: 1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crews NR, Johnson ML, Schleck CD, et al. Prevalence and predictors of gastroesophageal reflux complications in community subjects. Dig Dis Sci 2016; 61: 3221–3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson BC, Giovannucci EL, Fuchs CS. Smoking and Barrett’s esophagus in women who undergo upper endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci 2011; 56: 1707–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung KW, Talley NJ, Romero Y, et al. Epidemiology and natural history of intestinal metaplasia of the gastroesophageal junction and Barrett’s esophagus: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1447–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor MJ, Weston AP, Mayo MS, et al. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and erosive esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy for dyspepsia in a VA population. Dig Dis Sci 2004; 49: 920–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pascarenco OD, Boeriu A, Mocan S, et al. Barrett’s esophagus and intestinal metaplasia of gastric cardia: Prevalence, clinical, endoscopic and histological features. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2014; 23: 19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo CJ, Lin CH, Liu NJ, et al. Frequency and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in Taiwanese patients: A prospective study in a tertiary referral center. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55: 1337–1343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rex DK, Cummings OW, Shaw M, et al. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in colonoscopy patients with and without heartburn. Gastroenterology 2003; 125: 1670–1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khoury JE, Chisholm S, Jamal MM, et al. African Americans with Barrett’s esophagus are less likely to have dysplasia at biopsy. Dig Dis Sci 2012; 57: 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kula Z, Welshof A. The prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus in own material of 6326 endoscopies. Gastroenterol Pol 2007; 14: 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elizondo JLH, Robles RM, Compean DG, et al. Prevalencia de esófago de Barrett: Estudio observacional en una clínica de gastroenterología. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2017; 82: 296–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JH, Rhee PL, Lee JH, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett’s esophagus in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 22: 908–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerson LB, Shetler K. and Triadafilopoulos G. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic individuals. Gastroenterology 2002; 123: 461–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gerson LB, Banerjee S. Screening for Barrett’s esophagus in asymptomatic women. Gastrointest Endosc 2009; 70: 867–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zagari RM, Fuccio L, Wallander MA, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms, oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus in the general population: The Loiano-Monghidoro study. Gut 2008; 57: 1354–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zaninotto G, Avellini C, Barbazza R, et al. Prevalence of intestinal metaplasia in the distal oesophagus, oesophagogastric junction and gastric cardia in symptomatic patients in north-east Italy: A prospective, descriptive survey. Dig Liver Dis 2001; 33: 316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gruppo Operativo per lo Studio delle Precancerosi dell’Esofago (GOSPE) . Barrett’s esophagus: Epidemiological and clinical results of a multicentric survey. Int J Cancer 1991; 48: 364–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katsinelos P, Lazaraki G, Kountouras J, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in Northern Greece: A prospective study. Hippokratia 2013; 17: 27–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dina L, Pacurariu A, Tanţău M. Prevalence and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Study in a hospital population in a tertiary care center. HVM Bioflux 2015; 7: 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jonaitis L, Kriukas D, Kiudelis G, et al. Risk factors for erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in a high Helicobacter pylori prevalence area. Medicina 2011; 47: 434–439. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fagundes RB, Cantarelli JC, Bassi LAP, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus at the digestive endoscopy unit of a reference hospital in the central region of the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Gastrenterologia Endoscopia Digestiva 2003; 22: 213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Csendes A, Smok G, Burdiles P, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus by endoscopy and histologic studies: A prospective evaluation of 306 control subjects and 376 patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esophagus 2000; 13: 5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amano Y, Kushiyama Y, Yuki T, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus with intestinal predominant mucin phenotype. Scand J Gastroenterol 2006; 41: 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng S, Cui Y,. Xiao LY, et al. Prevalence of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in the adult Chinese population. Endoscopy 2009; 41: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Fan XS, Zou XP. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus remains low in Eastern China: Single-center 7-year descriptive study. Saudi Med J 2012; 33: 1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong WM, Lam SK, Hui WM, et al. Long-term prospective follow-up of endoscopic oesophagitis in southern Chinese – prevalence and spectrum of the disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 2037–2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeh C, Hsu CT, Ho AS, et al. Erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in Taiwan: A higher frequency than expected. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42: 702–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khamechian T, Alizargar J, Mazoochi T. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in outpatients with dyspepsia in Shaheed Beheshti Hospital of Kashan. Iranian J Med Sci 2013; 38: 263–266. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chak A, Alashkar BM, Isenberg GA, et al. Comparative acceptability of transnasal esophagoscopy and capsule esophagoscopy: A randomized controlled trial in a veteran population. Gastrointest Endosc 2014; 80: 774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward EM, Wolfsen HC, Achem SR, et al. Barrett’s esophagus is common in older men and women undergoing screening colonoscopy regardless of reflux symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 12–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spechler SJ, Zeroogian JM, Antonioli DA, et al. Prevalence of metaplasia at the gastro-oesophageal junction. Lancet 1994; 344: 1533–1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Zanten V, Thomson SJ, Barkun AB, et al. The prevalence of Barrett’s oesophagus in a cohort of 1040 Canadian primary care patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia undergoing prompt endoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006; 23: 595–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johansson J, Håkansson HO, Mellblom L, et al. Prevalence of precancerous and other metaplasia in the distal oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal junction. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40: 893–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronkainen J, Aro P, Storskrubb T, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in the general population: An endoscopic study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 1825–1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Voutilainen M, Sipponen P, Mecklin JP, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Prevalence, clinical, endoscopic and histopathological findings in 1,128 consecutive patients referred for endoscopy due to dyspeptic and reflux symptoms. Digestion 2000; 61: 6–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Mas CR, Kramer M, Seifert E, et al. Short Barrett: Prevalence and risk factors. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999; 34: 1065–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Freitas MC, Moretzsohn LD, Coelho LG. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in individuals without typical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Arq Gastroenterol 2008; 45: 46–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cárdenas V. Barrett’s esophagus: Prevalence and risk factors in the National Hospital Arzobispo Loayza in Lima-Peru. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 2010; 30: 284–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chacaltana A, Urday C, Ramon W, et al. Prevalencia, características clínico-endoscópicas y factores predictivos de esófago de Barrett. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 2009; 29: 24–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toruner M, Soykan I, Ensari A, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: Prevalence and its relationship with dyspeptic symptoms. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 19: 535–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee YY, Sharif SET, Syed SHSA, et al. Barrett’s esophagus in an area with an exceptionally low prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection. International Scholarly Research Network Gastroenterology 2011; 2011: 1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosaida MS, Goh KL. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, reflux oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a multiracial Asian population: A prospective, endoscopy based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004; 16: 495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiong LS, Cui Y, Wang JP, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Barrett’s esophagus in patients undergoing endoscopy for upper gastrointestinal symptoms. J Dig Dis 2010; 11: 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee JI, Park H, Jung HY, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in an urban Korean population: A multicenter study. J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 23–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fireman Z, Wagner G, Weissman J, et al. Prevalence of short-segment Barrett’s epithelium. Dig Liver Dis 2001; 33: 322–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bersentes K, Fass R, Sukhdeep P, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in Hispanics is similar to Caucasians. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43: 1038–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Robles SC, Peciña FS, Orta MDR. Barrett esophagus. An epidemiological study in an area of Spain. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 1995; 87: 353–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.De Carli DM, Araujo AF, Fagundes RB. Low prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in a risk area for esophageal cancer in South of Brazil. Arq Gastrenterol 2017; 54: 305–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Peña NG, Manrique MA, García MA, et al. Prevalencia de esófago de Barrett en pacientes no seleccionados sometidos a esofagogastroduodenoscopia y factores de riesgo associados. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2005; 70: 20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yilmaz N, Tuncer K, Tunçyürek M, et al. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and erosive esophagitis in a tertiary referral center in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol 2006; 17: 79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Siwiec RM, Dua K, Surapaneni SN, et al. Unsedated transnasal endoscopy with ultrathin endoscope as a screening tool for research studies. Laryngoscope 2012; 122: 1719–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conio M, Cameron AJ, Romero Y, et al. Secular trends in the epidemiology and outcome of Barrett’s oesophagus in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gut 2001; 48: 304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cameron AL, Lomboy CT. Barrett’s esophagus: Age, prevalence, and extent of columnar epithelium. Gastroenterology 1992; 103: 1241–1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cameron AJ, Zinsmeister AR, Ballard DJ, et al. Prevalence of columnar-lined (Barrett’s) esophagus. Gastroenterology 1990; 99: 918–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coleman HG, Bhat S, Murray LJ, et al. Increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus: A population-based study. Eur J Epidemiol 2011; 26: 739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ford AC, Forman D, Reynolds PD, et al. Ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status as risk factors for esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Epidemiol 2005; 162: 454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taghipour-Zahir S, Binesh F, Mosavi NS. Prevalence and trends of malignant and benign esophageal lesions in Iran between 1997 and 2007. Esophagus 2012; 9: 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andreollo NA, Michelino MU, Brandalise NA, et al. Incidence and epidemiology of Barrett’s epithelium at the “Gastrocentro.” Arq Gastroenterol 1997; 34: 22–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yamagishi H, Koike T, Ohara S, et al. Tongue-like Barrett’s esophagus is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14: 4196–4203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Azuma N, Endo T, Arimura Y, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus and expression of mucin antigens detected by a panel of monoclonal antibodies in Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in Japan. J Gastroenterol 2000; 35: 583–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zullo A, Esposito G, Ridola L, et al. Prevalence of lesions detected at upper endoscopy: An Italian survey. Eur J Intern Med 2014; 25: 772–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Gastric surgery is not a risk factor for erosive esophagitis or Barrett’s esophagus. Scand J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 403–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Alexandropoulou K, van Vlymen J, Reid F, et al. Temporal trends of Barrett’s oesophagus and gastro-oesophageal reflux and related oesophageal cancer over a 10-year period in England and Wales and associated proton pump inhibitor and H2RA prescriptions: A GPRD study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 25: 15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.van Blankenstein M, Caspar WN, Looman MS. Age and sex distribution of the prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus found in a primary referral endoscopy center. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Loffeld RJLF, van der Putten ABMM. Rising incidence of reflux oesophagitis in patients undergoing upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Digestion 2003; 68: 141–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.López-Colombo A, Jiménez-Toxqui M, Gogeascoechea-Guillén PD, et al. Prevalencia y características clínicas de pacientes con parche de mucosa gástrica ectópica en esófago. Rev Gastroenterol Mex 2018; 84: 442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shimoyama S, Ogawa T, Toma T, et al. A substantial incidence of silent short segment endoscopically suspected esophageal metaplasia in an adult Japanese primary care practice. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 4: 38–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Okita K, Amano Y, Takahashi Y, et al. Barrett’s esophagus in Japanese patients: Its prevalence, form, and elongation. J Gastroenterol 2008; 43: 928–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fujiwara Y, Higuchi K, Shiba M, et al. Association between gastroesophageal flap valve, reflux esophagitis, Barrett’s epithelium, and atrophic gastritis assessed by endoscopy in Japanese patients. J Gastroenterol 2003; 38: 533–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Niu CH, Zhou YL, Yan R, et al. Incidence of gastroesophageal reflux disease in Uygur and Han Chinese adults in Urumqi. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 8: 7333–7340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zou D, He J, Ma X, et al. Epidemiology of symptom-defined gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis: The systematic investigation of gastrointestinal diseases in China (SILC). Scand J Gastroenterol 2011; 46: 133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tseng PH, Lee YC, Chiu HM, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of Barrett’s esophagus in a Chinese general population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008; 42: 1074–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park JJ, Kim JW, Kim HJ. The prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in a Korean population: A nationwide multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009; 43: 907–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Choi DW, Oh SN, Baek SJ, et al. Endoscopically observed lower esophageal capillary patterns. Korean J Intern Med 2002; 17: 245–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Masri O, Ibrahim F, Badreddine R, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in Lebanon. Turk J Gastroenterol 2015; 26: 214–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rezailashkajani M, Roshandel D, Shafaee S, et al. High prevalence of reflux oesophagitis among upper endoscopies of Iranian patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 19: 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Smith JG, Li W, Rosson RS. Prevalence, clinical and endoscopic predictors of Helicobacter pylori infection in an urban population. Conn Med 2009; 73: 133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Masclee GMC, Coloma PM, Wilde M, et al. The incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands is levelling off. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 1321–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Alcedo J, Ferrández A, Arenas J, et al. Trends in Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis in Southern Europe: Implications for surveillance. Dis Esophagus 2009; 22: 239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fujimoto Ai, Hoteya S, Iizuka T, et al. Obesity and gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2013; 2013: 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Akiyama T, Yoneda M, Inamori M, et al. Visceral obesity and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus in Japanese patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol 2009; 9: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mathew P, Joshi AS, Shukla A, et al. Risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in Indian patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26: 1151–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Romero Y, Cameron AJ, Schaid DJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: Prevalence in symptomatic relatives. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Csendes A, Smok G, Burdiles P, et al. Prevalence of intestinal metaplasia according to the length of the specialized columnar epithelium lining the distal esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux. Dis Esophagus 2003; 16: 24–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sharifi A, Dowlatshahi S, Tabriz HM, et al. The prevalence, risk factors, and clinical correlates of erosive esophagitis and Barrett’s esophagus in Iranian patients with reflux symptoms. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2004; 2014: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fouad YM, Makhlouf MM, Tawfik HM, et al. Barrett’s esophagus: Prevalence and risk factors in patients with chronic GERD in Upper Egypt. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 3511–3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhang M, Fan XS, Zou XP. The prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus remains low in Eastern China. Saudi Med J 2012; 33: 1324–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ramirez FC, Akins R, Shaukat M. Screening of Barrett’s esophagus with string-capsule endoscopy: A prospective blinded study of 100 consecutive patients using histology as the criterion standard. Gastrointest Endosc 2008; 68: 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jobe BA, Hunter JG, Chang EY, et al. Office-based unsedated small-caliber endoscopy is equivalent to conventional sedated endoscopy in screening and surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus: a randomized and blinded comparison. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 2693–2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Winters C, Jr, Spurling TJ, Chobanian SJ, et al. A prevalent, occult complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology 1987; 92: 118–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ronkainen J, Talley NJ, Storskrubb T, et al. Erosive esophagitis is a risk factor for Barrett’s esophagus: A community-based endoscopic follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106: 1946–1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Conio M, Bonelli L, Munizzi F, et al. Prévalence de l’endobrachy-œsophage chez les patients avec reflux gastro-œsophagien. Acta Endoscopica 1998; 18: 339–346. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wani IR, Showkat HI, Bhargav DK, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus in patients with GERD in Northern India: Do methylene blue-directed biopsies improve detection of Barrett’s esophagus compared the conventional method? Middle East J Dig Dis 2014; 6: 228–236. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yin C, Jun Z, Maicang G, et al. Epidemiological investigation of Barrett’s esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease in Northwest China. Mil Med Res 2007; 27: 187–197. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Chavalitdhamrong D, Chen GC, Roth BE, et al. Esophageal capsule endoscopy for evaluation of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux symptoms: Findings and its image quality. Dis Esophagus 2011; 24: 295–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Banki F, Demeester SR, Mason RJ, et al. Barrett’s esophagus in females: A comparative analysis of risk factors in females and males. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 560–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Spechler SJ, Jain SK, Tendler DA, et al. Racial differences in the frequency of symptoms and complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002; 16: 1795–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gado A, Ebeid B, Abdelmohsen A, et al. Prevalence of reflux esophagitis among patients undergoing endoscopy in a secondary referral hospital in Giza, Egypt. Alex J Med 2015; 51: 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Arróspide MT, Aguinaga MM, Vásquez GR. Hiatal hernia as a risk factor for erosive esphagitis: Experience and endoscopic findings of a Peruvian population with heartburn. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 2003; 23: 36–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lin EC, Holub J, Lieberman D, et al. Low prevalence of suspected Barrett’s esophagus in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease without alarm symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 17: 857–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kulig M, Nocon M, Vieth M, et al. Risk factors of gastroesophageal reflux disease: Methodology and first epidemiological results of the ProGERD study. J Clin Epidemiol 2004; 57: 580–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pelechas E, Azoicăi D. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: Epidemiological data, symptomatology and risk factors. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 2013; 117: 183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Abdul-Razzak KK, Bani-Hani KE. Increased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric cardia of patients with reflux esophagitis: A study from Jordan. J Dig Dis 2007; 8: 203–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nassif PA, Pedri LE, Martins PR, et al. Incidence and predisponent factors for the migration of the fundoplication by Nissen-Rossetti technique in the surgical treatment of GERD. Araq Bras Cir Dig 2012; 25: 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Shiota S, Singh S, Anshasi A, et al. Prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus in Asian countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13: 1907–1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qumseya BJ, Bukannan A, Gendy S, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc 2019; 90: 707–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-ueg-10.1177_2050640620939376 for The global prevalence of Barrett’s esophagus: A systematic review of the published literature by Inês Marques de Sá, Pedro Marcos, Prateek Sharma and Mário Dinis-Ribeiro in United European Gastroenterology Journal