Abstract

Purpose

Arteriovenous fistulas of the Vein of Galen region in adults (Ad-VGAVF) are an uncommon entity with specific anatomic features. The aim of this article is to present our experience in the endovascular treatment of this pathology and to propose a therapeutic strategy based precisely on the angioarchitecture of these lesions.

Materials and methods

During a 20-year period, 10 patients underwent endovascular treatment of Ad-VGAVF. They were nine men and one woman with a mean age of 50 years (23–66 years) treated with the same embolization strategy. Clinical presentation, angiographic characteristics, therapeutic strategy, and clinical outcomes were recorded.

Results

All patients were treated exclusively by endovascular approach. Transarterial access was performed in eight patients and combined transvenous and transarterial access in two. Complete obliteration of the fistula was obtained in all patients. There were no intraprocedural complications. Post-embolization neurological symptoms occurred in 5 of 10 with complete resolution at six months in all of them.

Conclusion

Arteriovenous fistulas of the Vein of Galen region in adults present uniform angioarchitecture despite their low prevalence. Based on this constant angioarchitecture and especially on the features of its venous drainage, judicious embolization strategy is feasible and effective. Ten cases treated entirely by endovascular approach with excellent clinical and angiographic outcomes show this treatment like a curative alternative for this entity of deep topography and severe prognosis.

Keywords: Angiography, arteriovenous dural fistula, arteriovenous malformation, therapeutic embolization, Vein of Galen

Introduction

Arteriovenous fistulas of the Vein of Galen (VOG) region in adults (Ad-VGAVF) are an uncommon entity with specific features attributable to the anatomy and location of the vein itself.

The VOG forms during the 6th and 11th weeks of gestation, from the fusion of the internal cerebral veins and the basal veins of Rosenthal, behind the pineal gland. At an earlier stage, a precursor to the VOG, namely, the median prosencephalic vein or vein of Markowski, drains the choroid plexus into a dorsal interhemispheric dural plexus known as the falcine sinus. This vein will regress at the end of the first trimester due to the development of the basal ganglia, leading to the development of the VOG. The true malformations of the Galen vein (VOGM) arise before that regression causing an arteriovenous fistula between the embryonic choroidal arteries and the median prosencephalic vein, which produces a high blood flow in this embryonic venous system preventing its regression and VOG development.1

Conversely, the arteriovenous fistulas of the VOG region that present in adults (Ad-VGAVF) are shunts with the fully developed VOG and therefore differ from the pediatric VOGM. On the other hand, with respect to adults, although the Ad-VGAVF could be considered a dural fistula, the location and anatomy of the VOG lead to differences in the angioarchitecture and natural history of this particular fistula and determine its therapeutic approach.

The aim of this article is to present our experience analyzing the angioarchitecture, treatment strategy, and results from a series of 10 patients with Ad-VGAVF treated exclusively with endovascular approach.

Materials and methods

A retrospective review of the database from three neurointerventional units, directed or supervised by the senior author of this article (AC), was performed. The database spanned globally from 1997 to 2018 and included a total of 543 cases (pial and dural AVMs). Selection criteria included patients older than 18 years old and presence of Ad-VGAVF treated by endovascular approach. A total of 10 patients were identified. The senior author treated 9 of the 10 patients.

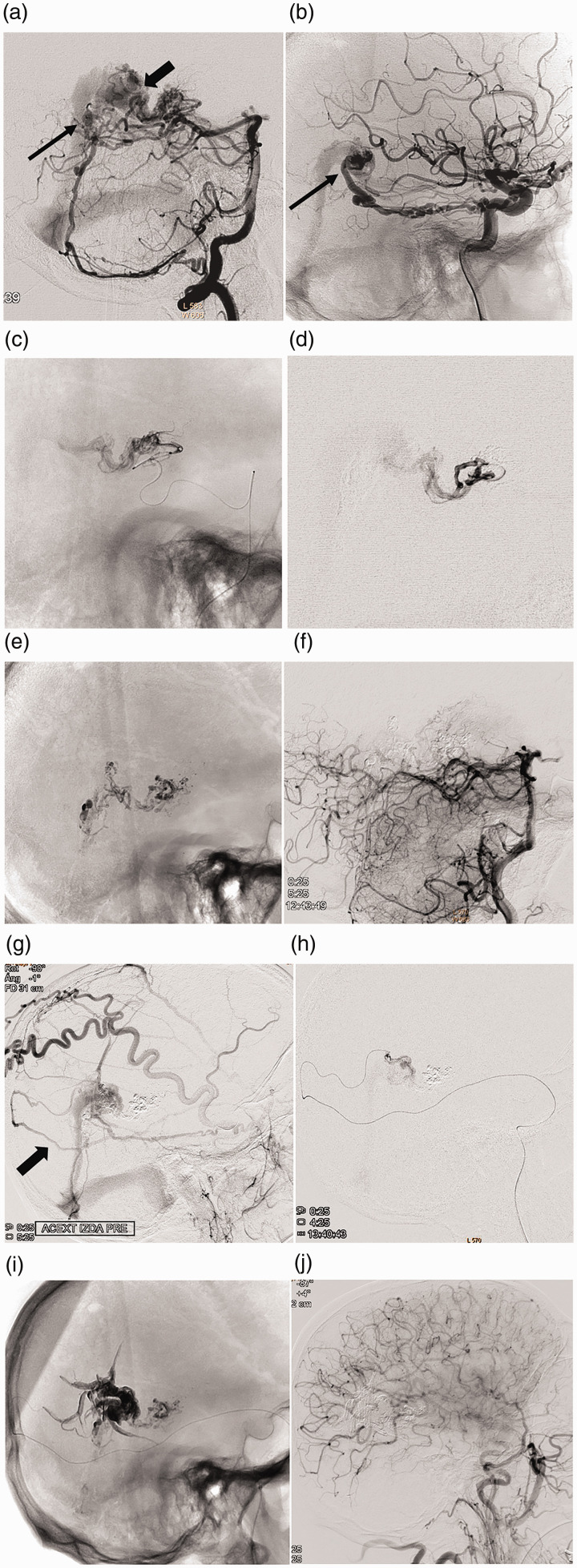

In all cases, the same embolization strategy was maintained. This strategy, summarized in the principles: to embolize “from anterior to posterior, from the pial to the dural feeders, and from the arterial to the venous side” (Figure 1), will be further expanded in the discussion section.

Figure 1.

Case 4: Embolization strategy “from front to back, from pial to dural, and from the arterial to the venous side.” Right VA (a) and right ICA (b) angiograms of an Ad-VGAVF fed by pial branches of the PCAs and dural branches of the VA (PMA), ICA (MHT) and ECA (MMA). Pial component draining into the anterior segment of the Vein of Galen (thick arrow in a) and dural component into the posterior segment of the vein (thin arrows in a and b); (c, d) successive catheterization of the pial component: medial posterior and lateral posterior choroidal arteries; (e) Glubran cast embolization; (f) left VA angiogram with complete occlusion of the vertebrobasilar pial component; (g, h) embolization of the dural component at the end of procedure, through the MMA (thick arrow in g), with Onyx; (i) final cast; (j) postembolization right CCA angiogram showing total occlusion of the fistula.

Eight of the 10 patients underwent arterial embolization exclusively. Flow-directed catheters (Magic 1.2; Balt) and N-butylcyanoacrylate (NBCA) (Glubran 2; GEM S.r.I.) were used for the fistulous component with pial supply, while detachable tip catheters (Sonic; Balt or Apollo; Medtronic) and non-adhesive liquid embolic agents (Onyx; Medtronic, Phil; Microvention; or Squid, Balt) were used for the dural component.

In the remaining two cases, treated back in the 1990s, a combined transarterial and transvenous approach was used, embolizing the arterial component with NBCA (Hystoacryl) and the venous component with coils. In these two cases, the treatment strategy was considered the same as the other eight cases because the venous occlusion was performed only at the end of embolization.

Seven of the 10 patients underwent two embolization sessions, the three remaining patients a single session.

The clinical presentation of patients, the angiographic characteristics of fistulas, and the treatment clinical and angiographic outcome were collected.

Clinical and imaging follow-up time was variable in all the patients, and an angiography was performed from three months to one-year post-embolization to confirm occlusion stability.

Results

There was a predominance of male patients with nine men and one woman. The mean age was 50 years (range, 23–66 years).

Clinical presentation

One of the patients presented with SAH, five with symptoms of intracranial venous hypertension (chronic cephalea, cognitive disorders, pulsatile tinnitus), one with unilateral chemosis, one with headache, and three patients were asymptomatic.

The main clinical characteristics of the patients and the treatment outcome are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical presentation, outcome and angiographic follow up.

| Patient no. | Treatment date | Age/gender | Clinical presentation | Post procedural symptoms | Clinical outcome | Angiographic outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1993 | 36/M | Headache, memory loss | No | Resolution of previous symptoms | 6 m Obliterated |

| 2 | 1997 | 50/M | Blurred vision, headache, dizziness | Deafness | Definitive unilateral deafness. No other symptoms | 12 m Obliterated |

| 3 | 2013 | 52/M | Incidental | Blurred vision | Visual disturbance resolved in four months. Subsequently asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

| 4 | 2013 | 62/M | Headache | Acalculia | Acalculia resolved in five months. Subsequently asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

| 5 | 2014 | 66/M | Tinnitus, dizziness | 24 hours acute disorientation | Resolution of previous symptoms | 6 m Obliterated |

| 6 | 2017 | 54/M | Progressive cognitive impairment | Stuporous state. Bitaleral petechial hemorrhage. | Progressive improvement. Asymptomatic in two months | 6 m Obliterated |

| 7 | 2018 | 23/M | Headache. SAH | No | Asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

| 8 | 2018 | 45/F | Incidental | No | Asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

| 9 | 2018 | 65/M | Incidental | No | Asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

| 10 | 2018 | 45/M | Chemosis | No | Asymptomatic | 3 m Obliterated |

Angiographic anatomy

Angiographic arterial and venous anatomy and technical features of treatments are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Angiographic characteristics and treatment technique.

| Patient no. | Arterial dural supply | Arterial pial supply | Dominant supply | Venous Reflux ICVHTa | Straight sinus | Number of sessions | Stage 1: Approach and embolic agent | Stage 2: Approach and embolic agent | Associated venous patologies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ECA: OA, MMAVA: PMA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA | Dural | YesYes | Patent. Non functional | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply (+ TV occlusion test) | TV: VG occlusion with coils after negative occlusion test | No |

| 2 | VA: PMA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA | Pial | YesYes | Stenotic. Non functional | 2 | TA + TV: NBCA for pial supply. Coils in VG | TA: NBCA for dural supply | Right LS and JV occlusion |

| 3 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTA | PCA: LPChA | No | YesNo | Patent. Non functional | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply | TA: Onyx for dural supply | Dural AVF of SLS |

| 4 | ECA: OAVBS: PMA, SCA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA | No | YesYes | Patent. Non functional | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply | TA: Onyx for dural supply | SLS thrombosis |

| 5 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA | Dural | YesNo | Stenotic. Non functional | 1 | TA: NBCA for pial supply. Onyx for dural supply | – | Left C2 cervical epidural AV fistula |

| 6 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTA | PCA: MPChA, TPA | Dural | YesYes | Occluded | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply | TA: Squid for dural supply | SS occlusion |

| 7 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTAVBS: PMA, SCA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA, TPAACA: APA | No | NoNo | Absent. Patent FS | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply | TA: Onyx for dural supply | Persistent FS |

| 8 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTAVBS: PMA, SCA | PCA: MPChA | Dural | NoNo | Patent. Non functional | 2 | TA: NBCA for pial supply. Phil for dural supply | TA: Phil for dural supply | Left LS occlusion |

| 9 | ICA: MTAVBS: SCA | PCA: LPChAACA: APA | Dural | YesNo | Patent. Non functional | 1 | TA: NBCA for pial supply. Onyx for dural supply | – | Right TS thrombosis |

| 10 | ECA: MMA, OAICA: MTA | PCA: MPChA, LPChA | Pial | Yes (DVS and SOV) No | Occluded | 1 | TA: NBCA for pial supply. Phil for dural supply | – | SS occlusion |

ACA: anterior cerebral artery; APA: anterior pericallosal artery; BVR: basal vein of Rosenthal; ECA: external carotid artery; CCA: common carotid artery; ICA: internal carotid artery; LPChA: lateral posterior choroidal artery; MHT: meningohypophyseal trunk; MMA: middle meningeal artery; MPChA: medial posterior choroidal artery; MTA: marginal tentorial artery; OA: occipital artery; PCA: posterior cerebral artery; PICA: posterior inferior cerebellar artery; PMA: posterior meningeal artery; PPA: posterior pericallosal artery; RVA: right vertebral artery; SCA: superior cerebellar artery; TPA: thalamic perforating arteries: VA: vertebral artery; VBS: vertebrobasilar system; DVS: deep venous system; FS: falciform sinus; JV: jugular vein; LS: lateral sinus; SS: straight sinus; SLS: superior longitudinal sinus; SOV: superior ophthalmic vein; TS: transverse sinus; VG: Vein of Galen; DAVF: dural arteriovenous fistula; HT: hypertension; TA: transarterial; TV: transvenous; ICVHT: intracranial venous hypertension.

aAngiographic signs of intracranial venous hypertension: slowdown of the capillary phase, dilated medullary veins, and delay or absence of dural sinus filling.

Nine of the ten fistulas showed the typical angiographic pattern of Ad-VGAVF. One case showed a pattern similar to a pediatric VGM (case 7), that is, falciform sinus present and straight sinus absent and pial fistulous component supplied by typical arteries like choroidal arteries, anterior pericallosal artery, or thalamic perforating arteries.

Most of VGAVF had main supply from meningeal feeders. Only in two cases, the contribution from pial feeders was predominant.

Pre-treatment angiography showed straight sinus occlusion in two patients and stenosis in two others. The other patients have no occlusion of the fistula venous drainage, with a normal-sized straight sinus or a patent falcine sinus (case 7). Interestingly, the straight sinus, even when patent, was never functional venous drainage to the brain.

In nine cases, there was a venous reflux to the deep venous system. Furthermore, one-fourth of them was angiographic evidence of intracranial venous hypertension.

Concomitantly, venous disorders at other levels of the central nervous system were observed in nine of the ten patients: stenosis-occlusion of dural sinuses in six patients (cases 2, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10), superior sagittal sinus thrombosis six months post-embolization in one patient (case 4), persistent falcine sinus in one patient (case 7), and other AV fistulas of de CNS in two patients (case 3: SSS dural fistula, case 5: left C2 cervical epidural fistula).

Treatment outcome

There were no intraprocedural complications. However, five patients presented post-embolization neurological symptoms, mostly mild and with spontaneous resolution. The new onset symptoms consisted of permanent unilateral deafness (case 2); visual disorder lasting several months post-embolization (case 3); acalculia lasting several weeks (case 4); desorientation for 24 h (case 5); and a stuporous state established on day 3 after embolization that gradually improved with I.V. steroids turning asymptomatic in two months (case 6). This last patient had bilateral thalamic petechial hemorrhage and hydrocephalus in non-contrast CT head (Figure 2). We attribute these symptoms to a venous origin, as discussed in the following section.

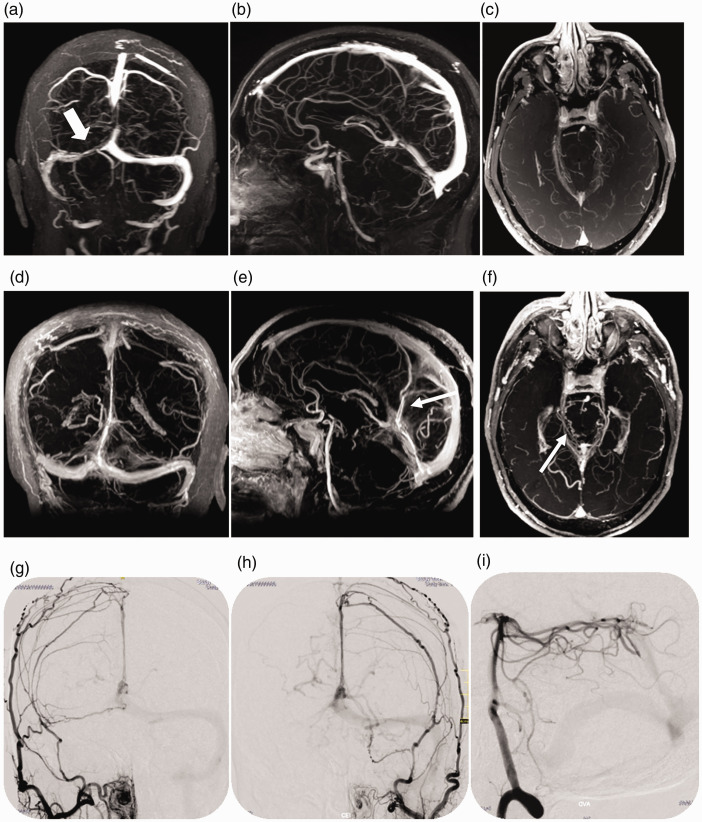

Figure 2.

Case 6: Postembolization complication (thalamic petechial hemorrhage). Right VA angiography, arterial (a) and venous phase (b), showing an Ad-VGAVF with predominantly pial supply and straight sinus occlusion. Significant cortical venous reflux demonstrating ICVHT (arrows in b); (c, d) postembolization right VA angiography showing complete occlusion of the vertebrobasilar fistulous component. Three days post-embolization, the patient presented decreased level of consciousness and coma and head computed tomography scan (e) demonstrated petechial thalamic hemorrhage (white arrows); (f) two months later, after corticotherapy and progressive improvement until asymptomatic, cranial CT showing disappearance of petechiae and decreased hydrocephalus.

Following embolization and complete occlusion of the Ad-VGAVF, the recovery of the VOG as cerebral venous drainage was observed in a single patient (case 3). All other patients presented the same cerebral venous drainage pattern 6–12 months after treatment as before embolization, with the deep venous system draining into the superficial venous system through anastomoses.

Discussion

The arteriovenous fistulas localized in the VOG region in the adults (Ad-VGAVF) have seldom been reported in the literature as a separate entity. This is because of its low prevalence, but also because of the lack of consideration as a different condition. As a result, the literature reports isolated cases2–7 and only one small series,8 and most publications present it as VOG malformations persisting in adulthood6 or as pial malformations4 or dural fistulas2,3,5,7–9 in the Galenic region. However, the uniform angioarchitectural features of these lesions, derived from their location and mainly from their venous drainage, make them interesting from both a pathophysiological and a therapeutic standpoint.

We could define Ad-VGAVF as acquired vascular lesions presenting in adulthood, usually in the fourth to fifth decades of life, consisting of arteriovenous fistulas at the wall of the VOG or at pial veins that drain directly into the VOG. These lesions have mixed pial–dural arterial feeders, fistulous structure (arteriovenous or arteriolovenous),10 and venous drainage through the VOG. Its supply by purely meningeal arteries, especially from the external carotid artery, is usually dominant. This is why it is crucial to perform vertebral angiography to detect the contribution from posterior cerebral arteries, which enables an accurate diagnosis and changes the treatment strategy.

The Ad-VGAVF morphology depends on its primary venous drainage, the VOG. Anatomically, the VOG connects the deep venous system to the straight sinus, acting as a bridge between these two regions and itself having an anterior pial segment and a posterior dural segment. Histologically, the VOG has intermediate characteristics between a pial vein and a dural sinus being the only cerebral vein having vasa vasorum in its wall.11,12 All the arterial branches that pass through this region may supply the vascular network of the VOG wall, even if their final destination is the brain. A microsurgical study of this region injecting stained gel into the arteries showed that the arterioles present in the VOG wall were fed by cortical branches of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA). Even more dorsally, arterioles supplied by quadrigeminal branches of the PCA can be observed extending into the wall of the straight sinus.12 Thus, the rich vascularity of the VOG wall and neighboring meningeal layers (histology) would be prone to developing arteriovenous connections, and these connections, in turn, would arise from both pial and dural arteries (anatomical relations).

The pathophysiology of these lesions is probably the same as that of dural fistulas, because they share the same age of presentation and angioarchitecture. There would be a trigger (venous thrombosis, trauma, infection, iatrogenesis, constitutional factors, etc.) that would favor the irreversible opening of physiological arteriovenous connections of the venous wall and the surrounding connective tissue, giving rise to active AV fistulas.3,8,13,14 As stated in the Results section, concomitant venous disease was observed in 7 of our 10 patients, supporting venous occlusion or increased venous pressure as the primary etiology of these lesions. Even in a patient, the development of the fistula could be verified following dural sinus thrombosis, demonstrating its acquired character (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Case 9: acquired character of the Ad-VGAVFs. Two cranial MRIs carried out two years apart show the appearance of an Ad-VGAVF. MRI April 2016 (3D FLASH venography), coronal (a), sagital (b), and axial view (c) demonstrating partial thrombosis of the right transverse sinus (thick arrow in a) and absence of fistula (b and c). February 2018: MRI (3D FLASH venography with MIP reconstruction), coronal (d), sagital (e), and axial view (f) showing that sinus thrombosis has improved and anomalous vessels have appeared in the region of the Vein of Galen (narrow arrows in e and f). Right and left external carotid artery angiograms (g, h) and right vertebral angiogram (i) showing the dural and pial supply.

When analyzing this entity in the spectrum of known pathologies, they can be considered under two perspectives. On one hand, as a tentorial dural fistula,7,15,16 following Lawton’s description and classification in 2008.17 On the other hand, as a pathology close to the VOGM,18 taking into account the presence of pial feeders as a differentiating feature and the report of cases diagnosed in adults with anatomical characteristics of this pediatric entity6 like in case 7. In any case, both etiopathogenesis would produce lesions with similar physiology, symptomatology, and treatment strategy.

Clinically, in our series, most patients were mildly symptomatic, but some of them had hydrocephalus or intracranial hypertension that led to severe symptoms (cases 1, 2, and 6) as described by other authors.19 Specially, our sixth patient presented gait disorders and rapidly progressive cognitive impairment probably related to acute straight sinus thrombosis with consequent retrograde venous hypertension. Similar symptoms have been described in Ad-VGAVF and nearby lesions (both pial malformations and dural fistulas) draining into the VOG when associated with straight sinus thrombosis,3,8 even thalamic hyperintensities, or petechial hemorrhages can be observed,20,21 demonstrating a pathophysiology common to all situations of venous drainage obstruction in this region. Likewise, in the literature of dural fistulas, this correlation of deep venous system hypertension and dismal clinical course is clearly established.22,23

Regarding the possibility of bleeding of these lesions, our experience differs from that reported by other authors since only one patient in our series presented hemorrhage (case 7). In the literature, hemorrhage appears as the clinical presentation in several case reports4,6–8,15 and in 50% of Wu et al.16 series. In addition, the bleeding rate of tentorial dural fistulas is also high: 74% in the review by Lewis et al.5 and 54% described by Lawton et al.17

Although there could be a selection bias in the clinical presentation in our series because patients presenting with intracranial hemorrhage may be admitted in neurosurgery and less symptomatic patients may consult neurointerventionalists, there could also be differences in the rate of bleeding depending on the venous drainage of the fistula. Based on Merland–Cognard classification of dural fistulas that correlates venous drainage with bleeding presentation,24,25 the bleeding risk of Ad-VGAVF could be “relatively low” when the fistula involves directly the VOG (10–18%, similar to type II dural fistula, since the structure of the VOG is close to that of a dural sinus; rate of presentation with bleeding), while the risk could be higher when the arteriovenous shunts primarily involve a leptomeningeal vein draining into the VOG (33–42%, like that of a type III dural fistula: direct fistula to the leptomeningeal vein).25–27 Recently, lower overall bleeding rates have been reported in dural fistulas, but leptomeningeal venous drainage continues to appear as key risk factor.28 Other factors like venous occlusion, venous ectasia, previous bleeds, etc. may increase the bleeding risk.29–32 In summary, though it seems to be established that Ad-VGAVF may bleed, its low prevalence makes it difficult to define the actual risk of spontaneous bleeding.

The treatment indication for these lesions is to avoid a possible hemorrhage and to resolve symptoms due to intracranial venous hypertension. Interestingly, endovascular treatment as the only therapy has seldom been reported in the literature.7,15,16,19 In 1981, O‘Reilly et al.2 presented a case of therapeutic abstention (corticosteroids); in 1988, Mayberg et al.3 presented symptomatic treatment by ventriculoperitoneal shunt; in 1991, Fournier et al.8 reported non-curative embolizations in four patients; in 2003, Joao et al.6 presented a radiosurgery treatment without reporting the outcome; and in 2004, Sato et al.4 presented a curative surgical treatment. Lawton et al.17 described seven cases of tentorial Galenic DAVF treated combining surgery and endovascular approach, all of them obliterated. Finally, Wu et al.16 presented six cases embolized with Onyx, achieving complete occlusion in five of them with 33% periprocedural hemorrhage, and other authors reported isolated cases of curative embolization.7,15,19 We present 10 cases of Ad-VGAVF treated entirely by endovascular approach, with complete obliteration in all of them and without major hemorrhagic complications.

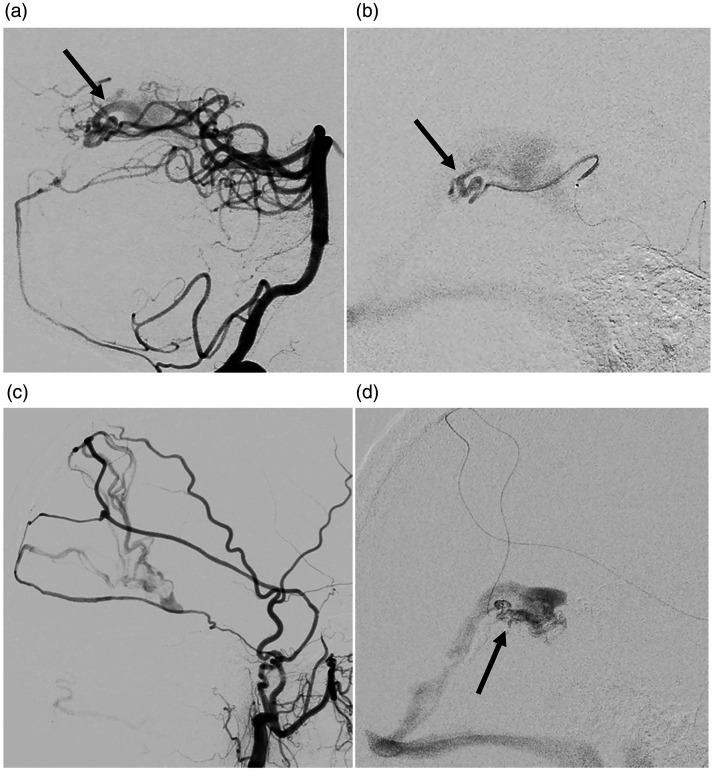

Regarding complications of endovascular treatment, although Ad-VGAVF has a predominantly fistulous angioarchitecture,10 its structure is more complex than that of the dural AVF, with veins interposed between the shunts and the VOG itself that can be pial veins (Figure 4), which increases the risk of peri-procedural bleeding.16 To minimize these risks, an adequate embolization strategy is mandatory.

Figure 4.

Case 5: Ad-VGAVF with angioarchitecture similar to that of the choroidal form of pediatric VGM. Right VA angiography (a) and selective catheterization (b) and right ECA angiography (c) and selective catheterization (d) demonstrating venules draining into the VG (arrows) from both the “pial component” (a, b) and the “dural component” (c, d).

Based on the characteristics of these lesions, we propose the embolization strategy followed in our 10 patients, which we consider optimal to increase the effectiveness and to reduce the complications of endovascular treatment. This strategy is based in three principles:

Occlusion should proceed from the anterior fistulous point to the posterior fistulous point of the fistula in order not to close off the distal portion of venous drainage earlier than the proximal portion and not to submit arteriovenous shunts (normally located ahead) to high pressures by occluding their venous outlet (normally located behind).

The fistulous component fed by pial arteries (most frequently posteromedial choroidal artery, posterolateral choroidal artery, and posterior pericallosal artery) should be occluded first, because it is the most fragile and most frequent plexiform component, the portion least protected by surrounding connective tissue, and the portion which, in case of rupture, would cause the greatest neurological damage because of its location and flow destination. Other authors16 have expressed their agreement with this principle in pointing out that their high rate of hemorrhagic complications (33%) could be lowered by “obliterating pial feeding arteries before fistula embolization for avoiding hemorrhagic complications.” Furthermore, it is advisable to approach this component using the thinnest, most atraumatic microcatheters to achieve the most distal embolization possible in vessels supplying the brain (pial vessels). Therefore, flow-directed catheters and cyanoacrylate would be the most appropriate option.

Third, it also seems logical to embolize the AVF from the arterial side to the venous side to minimize the risk of peri-procedural bleeding.

The embolization strategy could therefore be summed up as: embolize “from front to back, from pial to dural, and from the arterial side to the venous side.”

Occlusion of the VOG is usually necessary at the end of the procedure to achieve complete AVF obliteration. In addition, sometimes, transvenous approach is the only access to the fistula (cases 1 and 2, in the 90s, with non-adhesive embolic agents not developed). In this case, transvenous embolization should be performed after the “pial” AVM component has been occluded and seeking to conserve patency of the deep venous drainage as much as possible.

It is also advisable, before embolization, to make sure that the VOG and the straight sinus are non-functional, that is, the VOG not fill on cerebral venous return and/or exist reflux into the pial veins from the VOG filled through the fistula. This question has been discussed by other authors,7 who pointed out the importance of SS function on embolization outcomes, with lower risk endovascular treatment in patients with SS initially occluded.

Even so, we think that venous occlusion is the main source of complications when embolizing these lesions either because of too-early occlusion of the venous component (resulting in bleeding) or overly extensive occlusion of the venous component (resulting in progressive thrombosis and venous infarct). We assume that neurologic symptoms postembolization in five of our patients had a venous origin because there were no other apparent causes, there was no evidence of ischemic lesions in the three patients who underwent MRI post-embolization, most of the deficits resolved slowly but spontaneously and completely, and in one case (case 6), there was a latency time of three days between embolization and full onset of clinical symptoms (not typical of arterial ischemia). In this case, also, there was a severe venous congestion problem from previous straight sinus thrombosis and postembolization thalamic petechial hemorrhage was present.

In view of the frequent occurrence of neurological symptoms post-embolization and the importance we attribute to venous occlusion as a cause, it could be worthwhile to consider the benefit of anticoagulation therapy post-intervention, once the AVF has been completely obliterated.

Conclusion

In this article, we present 10 cases of AVM of VOG region with arterial pial supply in adults treated endovascularly with the same embolization strategy: AVF occlusion from front to back, from pial to dural, and from the arterial to the venous side. The cases are presented to emphasize both the uniform angioarchitecture of these lesions, representing an individual entity because of the features of their venous drainage, and the feasibility and effectiveness of judicious embolization. Finally, we would like to emphasize “extensive venous occlusion” as a key factor in the pathophysiology of these lesions and as a source of unexpected neurological symptoms post-embolization.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in the studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

ORCID iD: Laura Paúl https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1307-1695

References

- 1.Raybaud CA, Strother CM, Hald JK. Aneurysms of the vein of Galen: embryonic considerations and anatomical features relating to the pathogenesis of the malformation. Neuroradiology 1989; 31: 109–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O‘Reilly GV, Hammerschlag SB, Mullally WJ. Aneurysmal dilatation of the Galenic venous system caused by a dural arteriovenous malformation. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1981; 5: 899–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mayberg MR, Zimmerman C. Vein of Galen aneurysm associated with dural AVM and straight sinus thrombosis. J Neurosurg 1988; 68: 288–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato M, Sato S, Kodama N. Thalamic arteriovenous malformation with an unusual draining system. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2004; 44: 298–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adam I, Lewis TA, Tomsick JMT. Management of tentorial dural arteriovenous malformations: transarterial embolization combined with stereotactic radiation or surgery. J Neurosurg 1994; 81: 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joao X, Viriato A, Cristiana V, et al. Malformaçao aneurismática da veia de Galeno no adulto. Acta Méd Portuguesa 2003; 16: 203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laviv Y, Kasper E, Perlow E., Single session, transarterial complete embolization of Galenic dural AV fistula. Acta Neurochir 2016; 158: 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fournier D, Rodesch G, Terbrugge K, et al. Acquired mural (dural) arteriovenous shunts of the vein of Galen. Report of 4 cases. Neuroradiology 1991; 33: 52–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dan T, Xuan Ch, Xianli L, et al. Current status of endovascular treatment for dural arteriovenous fistulae in the tentorial middle region: a literature review. Acta Neurol Bel 2019; 119: 5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Houdart E, Gobin YP, Casasco A, et al. A proposed angiographic classification of intracranial arteriovenous fistulae and malformations. Neuroradiology 1993; 35: 381–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruchoux MM, Renjard I, Monegier du Sorbier C, et al . Histopathologie de la veine de Galiene. Neurochirurgie 1987; 33: 272–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Velut S, Santini JJ. Anatomic microchirurgicale de l'ampoule de Galien. Neurochirurgie 1987; 33: 264–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerber CW, Newton TH. The macro and microvasculature of the dura mater. Neuroradiology 1973; 6: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Piske RL, Lasjaunias P. Extrasinusal dural arteriovenous malformations. Report of three cases. Neuroradiology 1988; 30: 426–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyun-Jung K, Ji-Ho Y, Hong-Jae L, et al . Tentorial dural arteriovenous fistula treated using transarterial onyx embolization. J Kor Neurosurg Soc 2015; 58: 276–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu Q, Zhang XS, Wang HD, et al. Onyx embolization for tentorial dural arteriovenous fistula with pial arterial supply: case series and analysis of complications. World Neurosurg 2016; 92: 58–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawton MT, Mejia ROS, Pham D, et al. Tentorial dural anteriovenous fistulae: operative strategies and microsurgical results for six types. Neurosurgery 2008; 62: 110–124; discussion 124-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paramasivam S, Niimi Y, Meila D, et al. Dural arteriovenous shunt development in patients with vein of Galen malformation. Interventional Neuroradiology 2014; 20: 781–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vikram H, Syed Zafer M, Romnesh D, et al. Endovascular treatment of vein of Galen dural arteriovenous fistula presenting as dementia. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014; 17: 451–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morparia N, Miller G, Rabinstein A, et al. Cognitive decline and hypersomnolence: thalamic manifestations of a tentorial dural arteriovenous fistula (dAVF). Neurocrit Care 2012; 17: 429–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta R, Miyachi S, Matsubara N, et al. Pial arteriovenous fistula as a cause of bilateral thalamic hyperintensities: an unusual case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Surg 2013; 74 (Suppl 1): 18–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lasjaunias P, Chiu M, ter Brugge K, et al. Neurological manifestations of intracranial dural arteriovenous malformations. J Neurosurg 1986; 64: 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awad IA, Little JR, Akarawi WP, et al. Intracranial dural arteriovenous malformations: factors predisposing to an aggressive neurological course. J Neurosurg 1990; 72: 839–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djindjian R, Merland JJ. Super-selective arteriography of the external carotid artery. New York, NY: Springer Verlag, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cognard C, Gobin YP, Pierot L, et al. Cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas: clinical and angiographic correlation with a revised classification of venous drainage. Radiology 1995; 194: 671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Castainge P, Bories J, Brunet P, et al. Les fistules artérioveineuses méningées pures à drainage veinoux cortical. Rev Neurol 1976; 132: 169–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gross BA, Du R. The natural history of cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulae. Neurosurgery 2012; 71: 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gross BA, Albuquerque FC, McDougall CG, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of the untreated course of cerebral dural arteriovenous fistulas. J Neurosurg 2018; 129: 1114–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baltsavias G, Spessberger A, Hothorn T, et al. Cranial dural arteriovenous shunts. Part 4. Clinical presentation of the shunt with leptomeningeal venous drainage. Neurosurgery Rev 2015; 38: 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bulters DO, Mathad N, Culliford D, et al. The natural history of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulae with cortical venous reflux – the significance of venous ectasia. Neurosurgery 2012; 70: 312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lucas C de P, Caldas JG, Prandini MN. Do leptomeningeal venous drainage and dysplastic venous dilation predict hemorrhage in dural arteriovenous fistula? Surg Neurol 2006; 66 (Suppl 3): S2–S5; discussion S5–S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marc J, van Dijk C, Terbrugge KG, et al. Clinical course of cranial dural arteriovenous fistulas with long-term persistent cortical venous reflux. Stroke 2002; 33: 1233–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]