Key Points

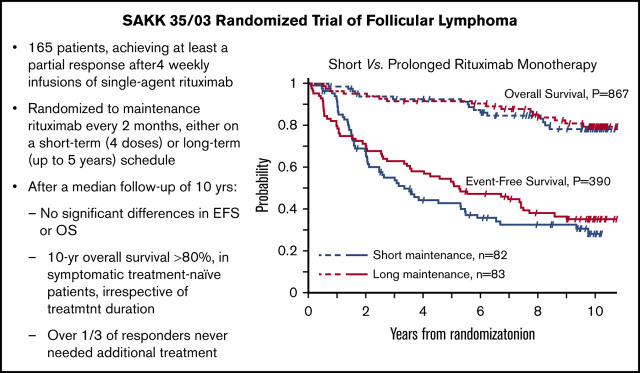

Upfront rituximab in advanced FL resulted in 10-year OS >80% in responsive patients, irrespective of maintenance duration.

At a follow-up of 10 years, one third of rituximab-responsive patients did not need additional treatment after rituximab monotherapy.

Abstract

The Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) conducted the SAKK 35/03 randomized trial (NCT00227695) to investigate different rituximab monotherapy schedules in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL). Here, we report their long-term treatment outcome. Two-hundred and seventy FL patients were treated with 4 weekly doses of rituximab monotherapy (375 mg/m2); 165 of them, achieving at least a partial response, were randomly assigned to maintenance rituximab (375 mg/m2 every 2 months) on a short-term (4 administrations; n = 82) or a long-term (up to a maximum of 5 years; n = 83) schedule. The primary end point was event-free survival (EFS). At a median follow-up period of 10 years, median EFS was 3.4 years (95% confidence interval [CI], 2.1-5.5) in the short-term arm and 5.3 years (95% CI, 3.5-7.5) in the long-term arm. Using the prespecified log-rank test, this difference is not statistically significant (P = .39). There also was not a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival or overall survival (OS). Median OS was 11.0 years (95% CI, 11.0-NA) in the short-term arm and was not reached in the long-term arm (P = .80). The incidence of second cancers was similar in the 2 arms (9 patients after short-term maintenance and 10 patients after long-term maintenance). No major late toxicities emerged. No significant benefit of prolonged maintenance became evident with longer follow-up. Notably, in symptomatic patients in need of immediate treatment, the 10-year OS rate was 83% (95% CI, 73-89%). These findings indicate that single-agent rituximab may be a valid first-line option for symptomatic patients with advanced FL.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), accounting for ∼35% of NHL cases.1 Although the past 2 decades have seen important progress in the treatment of FL, it continues to be considered a usually incurable disease. Progression of disease within 24 months of chemoimmunotherapy (POD24) has been associated with particularly poor survival.2 Clinical studies developed and conducted by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) and the Nordic Lymphoma Group (NLG) demonstrated that rituximab monotherapy can produce durable remissions in a substantial subset of FL patients, with overall survival (OS) similar to that achieved with immunochemotherapy but with less toxicity,3-8 providing a rationale for further development of front-line chemotherapy-free treatment strategies.9 Because the expected survival of FL patients is continuously improving, the long-term safety of treatment is becoming increasingly important, and there is a strong interest in developing therapeutic alternatives that may limit or delay cytotoxic exposure with its potentially serious late toxicity.10 The SAKK 35/03 trial, designed to better define the optimal duration of rituximab monotherapy, investigated 2 schedules of maintenance in patients with FL: patients achieving at least a partial response after 4 weekly doses of rituximab were randomly assigned to receive maintenance rituximab every 2 months on a short schedule (4 administrations) or on a prolonged schedule (up to 5 years). The trial, which recruited 270 patients with untreated and relapsed FL across 7 countries, did not meet its primary end point, because no statistically significant difference was shown in event-free survival (EFS) between the treatment arms.5 Here, we report a post hoc analysis of the trial with long-term results after a median follow-up of 10 years.

Patients and methods

Study design and treatment analysis

Patients with untreated, relapsed/progressed, stable, or chemotherapy-resistant histology-proven grades 1, 2, 3a, or 3b FL judged to be in need of therapy were included in this trial. For those previously treated with rituximab or radiolabeled anti-CD20 antibody, ≥12 months must have elapsed from the last administration. Patients were required to have a performance status ≤2, to be ≥18 years of age, HIV-negative, and free from serious underlying medical conditions that could impair their ability to participate in the trial. The presence of prior or concurrent malignancies, the transformation to high-grade lymphoma, and evidence of central nervous system involvement were considered exclusion criteria. Patients were registered and treated in 26 centers in 7 countries, and the trial was approved by the ethics committees of each participating institution and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before registration.

Details of the study design have been published.5 In brief, patients achieving a partial response or a complete response (CR) after 4 weekly administrations of single-agent rituximab (375 mg/m2 per week) were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to short rituximab maintenance (4 additional 375 mg/m2 courses given IV every 2 months) or to prolonged maintenance (375 mg/m2, every 2 months for a maximum of 5 years or until relapse, progression, or unacceptable toxicity).

Statistical analysis

The primary end point was EFS. Progression-free survival (PFS), OS, and toxicity were secondary end points. EFS was defined as the time from randomization until progressive disease (PD) or relapse, unacceptable toxicity, death from any cause, initiation of nonprotocol anticancer treatment, or secondary malignancy. PFS was defined as the time from randomization to relapse/progression or death from any cause. Patients not experiencing events were censored at the last known time that they were alive without PD or relapse. All randomly assigned patients were included in the analyses on an intent-to-treat basis. POD24 was defined according to the LymphoCare Study,2 excluding from the analysis the patients who, within 24 months from treatment start, died without PD or who were lost to follow-up without progression. Comparison of categorical data between the study arms was performed using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. Survival curves were estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method, and treatment arms were compared using the log-rank test.11 The assumption of proportional hazard was checked by using the Grambsch-Therneau test.12 Kaplan-Meier estimates of survival probabilities at 10 years were compared using a 2-sample test for survival curves at a fixed point in time.13 Cox proportional-hazard models were used for the estimation of hazard ratios (HRs) with their 95% confidence interval (CI), as well as to investigate the potential effects of stratification factors. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 software.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between August 2004 and September 2007, 270 patients were included in the trial, and 165 were randomly assigned to short-term (n = 82) or long-term (n = 83) maintenance. One hundred and five patients were not randomized because of PD/relapse (n = 17), stable disease (n = 75), toxicity (n = 2), refusal (n = 1), or other causes (n = 10). The characteristics of the patients were reported in detail.5 The 2 groups were well balanced, with the exception of elevated lactate dehydrogenase and extranodal disease, which were more frequent in the long-term maintenance arm. The median age was 55 years (range, 25-82), with a slight prevalence of females (62%). Bulky disease (>5 cm) was present in 27% of patients, and 15% had grade 3 FL. Almost 70% of the randomized patients had intermediate-risk or high-risk disease according to the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index. Seventy percent of patients were untreated at the time of study enrollment, and 10% of patients previously received anti-CD20 therapy. Table 1 summarizes the main clinicopathological features of the randomized patients.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Variable | Short maintenance | Long maintenance | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of randomized patients | 82 | 83 | 165 |

| Median age (range), y | 55 (34-81) | 57 (25-81) | 55 (25-81) |

| Males | 37 (45) | 26 (31) | 63 (38) |

| Stage III-IV disease | 63 (77) | 66 (80) | 129 (79) |

| Histologic grade 3 | 5 (6) | 8 (10) | 13 (9) |

| Therapy naive | 58 (71) | 59 (71) | 117 (71) |

| FLIPI high risk | 20 (25) | 27 (33) | 47 (28) |

| B symptoms | 14 (17) | 12 (14) | 26 (16) |

| Nodal areas >4 | 45 (55) | 49 (60) | 94 (57) |

| Extranodal involvement | 18 (22) | 37 (45) | 55 (33%) |

| Elevated LDH | 6 (7) | 19 (23) | 25 (15) |

| Bulky lesion >5 cm | 22 (27) | 23 (28) | 45 (27) |

Unless otherwise noted, data are n (%).

FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Outcome

The response rates to induction therapy were published previously and remained unchanged (overall response rate, 63%).5 Two patients in the short-term maintenance arm discontinued the treatment because of PD, and 37 patients in the long-term maintenance arm discontinued treatment primarily as a result of PD/relapse (n = 26) or unacceptable toxicity (n = 3).

At a median follow-up of 10 years, 107 events were recorded: 54 (65.9%) in the short-term maintenance arm, and 53 (63.9%) in the long-term maintenance arm. Table 2 describes the events according to the treatment arm.

Table 2.

Events for EFS analysis in the intent-to-treat population

| Short maintenance (n = 82) | Long maintenance (n = 83) | |

|---|---|---|

| Events | 54 (65.9) | 53 (63.9) |

| Censored | 28 (34.1) | 30 (36.1) |

| Type of event | ||

| Death | 3 (5.6) | 4 (7.6) |

| Disease progression or relapse | 47 (87.0) | 35 (66.0) |

| Secondary malignancy | 4 (7.4) | 7 (13.2) |

| Unacceptable toxicity | 0 (0) | 6 (11.3) |

| Initiation of nonprotocol anticancer treatment | 0 (0) | 1 (1.9) |

Data are n (%).

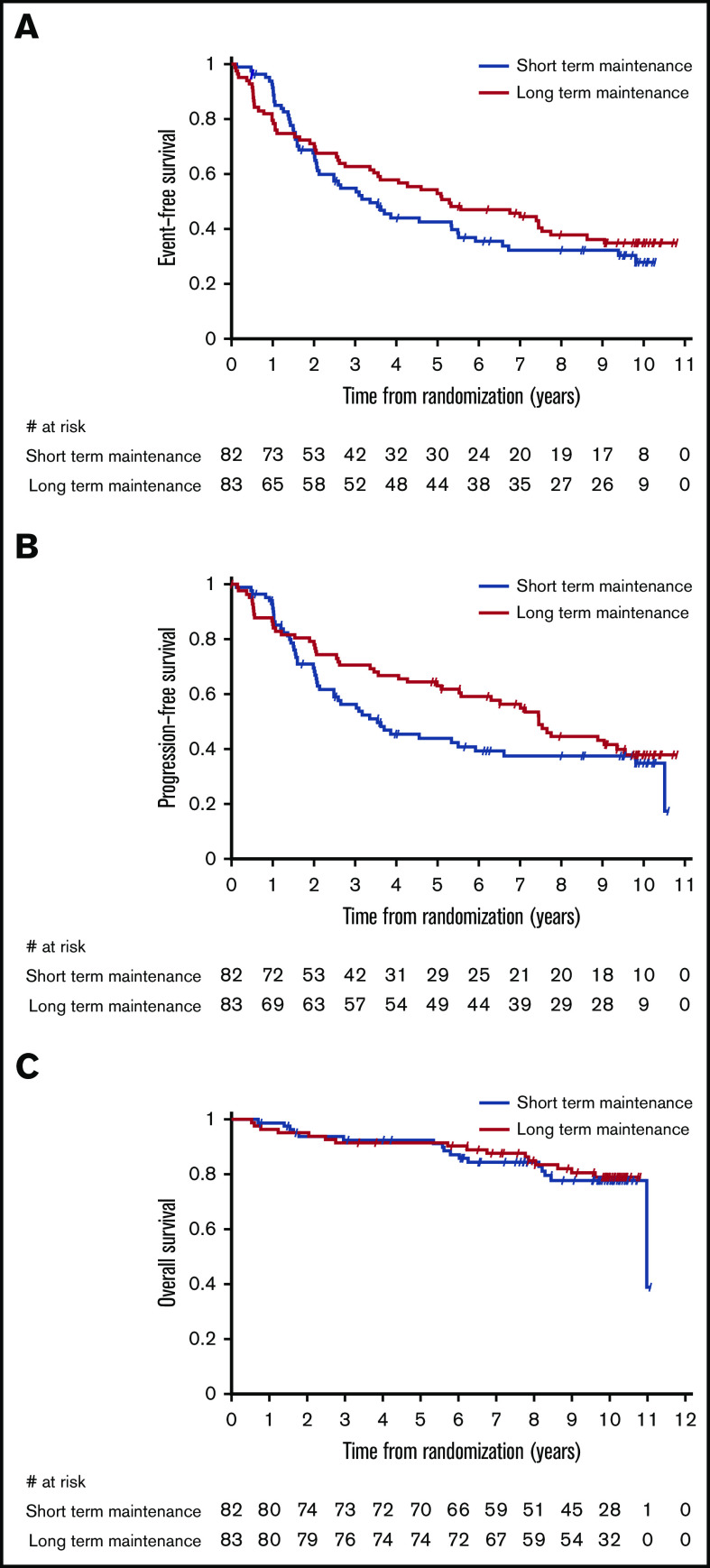

Figure 1 displays the Kaplan-Meier curves for EFS, PFS, and OS for each treatment arm. Despite the apparent crossing of the curves, no indication of nonproportional hazards was found for the analyzed time-to-event end points (P = .295 for EFS, P = .614 for PFS, and P = .964 for OS, Grambsch-Therneau test).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier estimates by maintenance duration in the intent-to-treat population. EFS (A), PFS (B), and OS (C).

Median EFS was 3.4 years (95% CI, 2.1-5.5) in the short-duration arm and 5.3 years (95% CI, 3.5-7.5) in the long-duration arm. Using the prespecified log-rank test, this difference is not statistically significant (P = .385; Table 3). Although in a multivariable Cox proportional-hazards model including the 146 patients still at risk after 8 months from randomization (time point corresponding to the treatment difference between the 2 arms), only the duration of maintenance maintained a significant effect on EFS (HR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.40-0.94; P = .024) after controlling for prior treatment and bulky disease. When the same analysis was performed for all 165 patients, the impact of treatment duration on EFS was no longer significant (HR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.57-1.22; P = .340).

Table 3.

Long-term survival estimates in the intent-to-treat population

| End point | Treatment-naive patients in need of therapy | Randomized patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (N = 97) | Short maintenance (n = 46) | Long maintenance (n = 51) | P* | All (N = 165) | Short maintenance (n = 82) | Long maintenance (n = 83) | P* | |

| EFS | ||||||||

| Median (95% CI), y | 5.1 (3.1-7.4) | 5.5 (2.1-9.8) | 5.0 (2.6-NA) | .924 | 4.3 (3.1-5.6) | 3.4 (2.1-5.5) | 5.3 (3.5-7.5) | .385 |

| 10-y (95% CI), % | 36.3 (26.2-46.5) | 34.2 (19.1-49.9) | 38.8 (25.5-51.9) | .608 | 31.5 (24.1-39.1) | 27.8 (17.6-39.0) | 34.9 (24.6-45.3) | .364 |

| PFS | ||||||||

| Median (95% CI), y | 7.4 (4.6-NA) | 6.6 (2.1-NA) | 7.4 (4.0-NA) | .739 | 5.9 (3.6-7.6) | 3.5 (2.1-6.6) | 7.4 (5.5-9.5) | .189 |

| 10-y (95% CI), % | 42.5.0 (31.4-53.3) | 43.9 (27.2-59.3) | 42.0 (27.2-56.1) | .869 | 36.0 (27.9-44.1) | 34.8 (23.5-46.3) | 37.8 (26.6-48.9) | .716 |

| OS | ||||||||

| Median (95% CI), y | 11.0 (NA) | 11.0 (NA) | Not reached (NA) | .521 | 11.0 (11.0-NA) | 11.0 (11.0-NA) | Not reached (NA) | .797 |

| 10-y (95% CI), % | 83.2 (73.6-89.5) | 80.7 (65.0-89.9) | 85.3 (71.6-92.7) | .567 | 78.4 (70.7-84.3) | 77.9 (66.3-85.9) | 79.0 (67.9-86.7) | .867 |

NA, not assessable.

Log-rank test and 2-sample test for survival curves at a fixed point in time (see "Patients and methods").

Median PFS was 3.5 years (95% CI, 2.1-6.6) in the short-duration arm and 7.4 years (95% CI, 5.5-9.5) in the long-duration arm, but the difference was not statistically significant (P = .189, log-rank test; Table 3).

OS at 10 years in the entire study cohort was 78% (95% CI, 71-84): 78% (95% CI, 66-86) in the short-maintenance arm and 79% (95% CI, 68-87) in the long-maintenance arm. Median OS with short maintenance was 11.0 years (95% CI, 11.0 to not assessable) and was not reached in the long-maintenance arm, with no statistically significant difference (P = .797, log-rank test; Table 3).

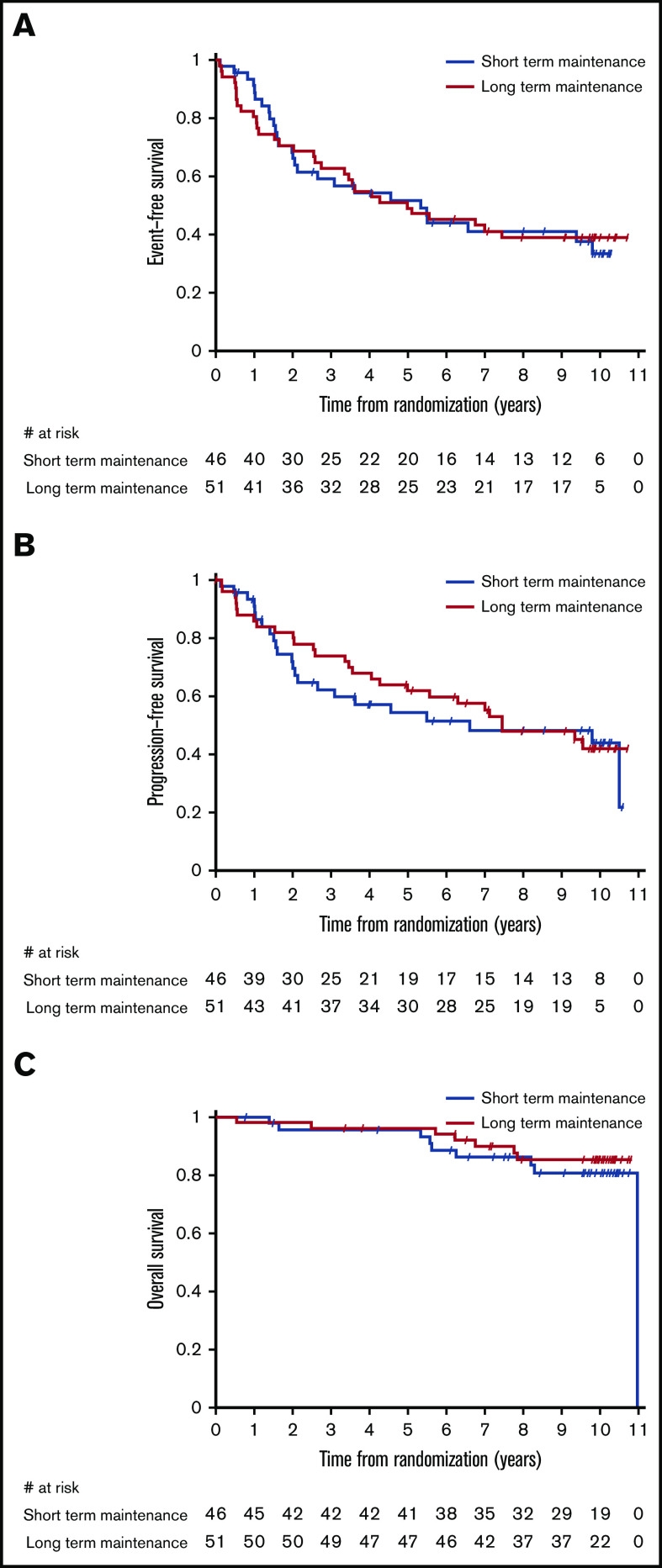

No impact of maintenance duration on time-related end points was evident between the study arms when the analysis was limited to the 117 patients who had no prior systemic treatment. In particular, median EFS, PFS, and OS of 97 treatment-naive patients with ≥1 of the clinical characteristics that generally define the need for active therapy (ie, bulky nodal masses, presence of B symptoms or cytopenias) were 5.1 years (95% CI, 3.1-7.4), 7.4 years (95% CI, 4.6 to not assessable), and 11.0 years (95% CI, not assessable), respectively, with no significant difference between arms (Figure 2). For patients responding after 4 weekly administrations of single-agent rituximab, 10-year survival was >80% in both arms, and more than one third of the patients did not require any further treatment after front-line rituximab (Table 3). In this subset of 97 symptomatic patients needing upfront therapy, the 10-year survival of 14 (15%) patients with POD24 was lower than in patients without POD24, although the difference was not significant (68.4%; 95% CI, 35.9-86.8 vs 85.6%; 95% CI, 75.5-91.8), and median OS was not reached.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier estimates by maintenance duration in the group of patients in need of therapy receiving rituximab alone as front-line treatment. EFS (A), PFS (B), and OS (C).

For the 48 patients previously treated for FL, median EFS and PFS were 2.6 and 3.0 years, respectively, whereas median OS was not reached.

Safety

As reported previously,5 a higher proportion of patients in the prolonged-maintenance arm experienced serious adverse events, most commonly infections. Table 4 summarizes the main adverse events of randomized patients.

Table 4.

Adverse events according to treatment arm

| Variable | Short maintenance (n = 82) | Long maintenance (n = 83) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All grades | Grade 3 or 4 | All grades | Grade 3 or 4 | |

| ≥1 AE | 41 (50.0) | 1 (1.2) | 63 (75.9) | 14 (16.9) |

| Hematologic AEs | ||||

| Neutropenia | — | — | — | 1 (1.2) |

| Nonhematologic AEs | ||||

| Infection | 17 | 1 (1.2) | 59 (71.1) | 4 (4.8) |

| Cardiac arrhythmia | — | — | 3 (3.6) | — |

| Hypertension | — | — | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) |

| Constitutional symptoms | 17 (20.7) | — | 49 (59.0) | — |

| Skin rash | 5 (6.1) | — | 29 (34.9) | 2 (2.4) |

| Gastrointestinal symptoms | 10 (12.2) | — | 49 (59.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (1.2) | 9 (10.8) | — | |

| Hepatobiliary/pancreas | — | — | 2 (2.4) | — |

| Edema | 3 (3.7) | — | 7 (8.4) | — |

| Musculoskeletal | — | — | 11 (13.3) | — |

| Neurological symptoms | 4 (4.9) | — | 22 (26.5) | 5 (6.0) |

| Ocular | 2 (2.4) | — | 4 (4.8) | — |

| Pain | 27 | — | 78 (94.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| Renal/genitourinary | 2 (2.4) | — | 7 (8.4) | — |

All data are n (%).

AE, adverse event; —, no adverse events.

Despite the fact that the number of patients with low immunoglobulin G levels in the follow-up phase was significantly higher in the prolonged maintenance arm, there was no evidence of a significant correlation between low immunoglobulin G levels and/or B-cell depletion and grade 3-4 infections.

After a median follow-up of 10 years, 33 deaths were reported: 17 in the short-maintenance arm and 16 in the long-maintenance arm. The leading cause of death was lymphoma (12 and 9 patients in the short- and long-maintenance arms, respectively). The incidence of subsequent cancers increased in both arms over time; 9 patients were reported to develop cancer in the short-maintenance arm, including 3 cases with reported histological transformation (2 to classical Hodgkin lymphoma and 1 to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and 10 patients developed cancer in the long-maintenance arm. There was no major additional toxicity with longer follow-up.

Discussion

This long-term evaluation of the SAKK 35/03 trial provides important clinical information. Protracted exposure to rituximab was well tolerated and was not associated with unexpected toxicity. However, with a longer follow-up of 10 years, this study failed to demonstrate any advantage for prolonged maintenance in terms of EFS, PFS, or OS. This may be explained by the limited number of patients per arm; however, it should be noted that the significant benefit previously reported for PFS5 was no longer evident with prolonged follow-up. Nevertheless, more than one third of advanced FL patients responding to frontline rituximab monotherapy did not require further therapy and had a 10-year survival >80%, irrespective of maintenance duration.

The optimal duration of rituximab administration has not been completely clarified by the different clinical trials conducted over the last 20 years. Based on the results of this study, maintenance rituximab given every 2 months for 8 months (the short-term schedule) has been accepted as a front-line approach in most Swiss institutions. However, for patients treated with rituximab in association with chemotherapy, clinicians, in general, administer maintenance rituximab every 2 months for a total of 2 years based on the results of other studies (eg, the PRIMA or the GALLIUM trial).14,15 In this setting, maintenance therapy exceeding 2 years has also been associated with increased toxicity, in particular toward the end of maintenance,16 and it is currently not recommended. Several trials reported a higher rate of mortality not related to lymphoma, in particular in patients receiving maintenance after bendamustine-based combinations.15,17 The main cause of mortality in these patients was Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; for that reason, it is recommended to administer long-term prophylaxis with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or an alternative drug. Finally, prolonged rituximab administration may have an impact on the cost of medical care. For the present trial, we estimate an average total cost of 50 000 USD and 220 000 USD for the short-term and long-term schedules, respectively.

With our trial, we confirmed the results of the previous SAKK 35/98 trial4 indicating that a substantial proportion of patients with FL treated with 8 courses of front-line rituximab can have a favorable outcome. With a median follow-up of 10 years, more than one third of patients responding after 4 weekly administrations of single-agent rituximab and treated with either the short-term or the long-term schedule did not experience any events (ie, relapse, progression, death). Notably, the favorable outcomes and the lack of benefit from prolonged maintenance were also evident in the subset of patients with symptomatic advanced disease, even though there was no definition of need for therapy in the protocol. Indeed, when limiting survival analysis to patients presumed to need treatment, 10-year OS exceeded 80%. These results are in keeping with the 78% of patients alive at 10 years from diagnosis in a recent pooled analysis6 of 2 randomized NLG trials of upfront rituximab monotherapy, with or without interferon, in symptomatic FL.7,8

Even though a direct comparison with the outcome of patients treated with front-line immunochemotherapy will be misleading because of the diversity of the studied population, the long-term results of the 35/03 SAKK trial confirmed once again that single-agent rituximab is effective, well tolerated, and led to long-term remission and prolonged failure-free survival in a substantial portion of patients. Moreover, for patients responding to the induction therapy, upfront treatment with rituximab alone does not appear to hamper the chances of favorable long-term outcomes, because 10-year OS for patients was excellent and comparable to the one reported in the rituximab-chemotherapy trials (Table 5)18-24 without major safety issues. Our results provide further evidence supporting that single-agent rituximab may also be considered a first-line therapeutic option for patients with advanced symptomatic disease, not only for those with low tumor burden.25,26 Our results are also in line with the above mentioned NLG findings6 and indicate that chemotherapy can be safely delayed in the majority of patients.

Table 5.

Long-term survival rates in the present study compared with those reported with immunochemotherapy regimens

| Reference | Study | ClinicalTrials.gov identifier | Regimen | N | 10-y OS (95% CI), % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present study | SAKK 35/03 | NCT00227695 | 4× R weekly + short R maintenance | 82 | 77.9 (66.3-85.9) |

| 4× R weekly + long R maintenance | 83 | 79.0 (67.9-86.7) | |||

| Morschhauser et al, 201321 | FIT | NCT00185393 | Chemotherapy ± R* | 202 | 81 (NR) at 8 y |

| Chemotherapy ± R* +90Y-ibritumomab | 207 | 84 (NR) at 8 y | |||

| Bachy et al, 201318 | FL2000 | NCT00136552 | CHVP + interferon | 183 | 69.8 (63.1-76.6) at 8 y |

| R-CHVP + interferon | 175 | 78.6 (72.5-84.7) at 8 y | |||

| Rummel et al, 201723 | StiL NHL1 | NCT00991211 | R-bendamustine | 261 | 71 (NR) |

| R-CHOP | 253 | 66 (NR) | |||

| Nastoupil et al, 201722 | MDACC | NCT00577993 | FND, followed by R and IFN | 78 | 76 (67-86) |

| R-FND followed by IFN | 80 | 73 (64-84) | |||

| Luminari et al, 201820 | FOLL05 | NCT00774826 | R-CVP | 178 | 85 (77-91) at 8 y |

| R-CHOP | 178 | 83 (75-89) at 8 y | |||

| R-FM | 178 | 79 (71-85) at 8 y | |||

| Shadman et al, 201824 | SWOG-S0016 | NCT00006721 | R-CHOP | 267 | 81 (75.9-85.4) |

| CHOP + 131I-tositumomab | 264 | 75 (69.3-80.2) | |||

| Bachy et al, 201919 | PRIMA | NCT00140582 | R-CHOP/R-CVP/R-FCM | 513 | 79.9 (NR) |

| R-CHOP/R-CVP/R-FCM + R maintenance | 505 | 80.1 (NR) |

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), vincristine, and prednisolone; CHVP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin hydrochloride (hydroxydaunorubicin), etoposide, and prednisolone; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; IFN, interferon; NR, not reported; R, rituximab; R-FCM, rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone; R-FM, rituximab, fludarabine, and mitoxantrone; R-FND, rituximab, fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone; ±, with or without.

First-line therapy with chlorambucil, CVP, CHOP, CHOP-like, fludarabine combinations, with or without rituximab.

As stated in our previous report,5 this trial has some limitations; patients were enrolled at the discretion of the treating physician, without a precise definition of need for therapy in the protocol, and the study population is heterogeneous, including untreated and pretreated patients. Detailed information regarding subsequent therapies after progression/relapse was not prospectively collected and neither was the proportion of patients showing histological transformation.

In conclusion, prolonged maintenance was associated with increased toxicity and did not lead to a significant improvement in the outcome. Unlike in the primary trial report,5 at a median follow-up of 10 years, we no longer found an indication of nonproportional hazards in EFS, despite the apparent crossing of the curves. Moreover, the observed difference in PFS also has become statistically insignificant. Nevertheless, the OS observed in this trial supports the use of a front-line chemotherapy-free approach as an alternative to standard immunochemotherapy for a substantial portion of patients. Rituximab monotherapy (at the standard dose of 375 mg/m2, given ≥8 times) may still represent an appropriate benchmark upon which to build future clinical trials exploring chemotherapy-free alternatives in FL.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the investigators, research nurses, and data managers of the SAKK 35/03 trial at each study center, as well as the central study team at the SAKK coordinating center for administrative support with collecting data and conducting the study.

This work was supported in part by the Italian Ministry of Health with Ricerca Corrente and 5x1000 funds. The SAKK 35/03 trial was supported by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd, who provided rituximab for the maintenance therapy, by a scientific grant from Oncosuisse (OCS 01468-02-2004), and by research agreements with the following institutions: the Swiss State Secretary for Education, Research and Innovation, the Swiss Cancer Research Foundation, and the Swiss Cancer League.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 60th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, San Diego, CA, 1-4 December 2018.

For original data, please contact Sämi Schär (saemi.achaer@sakk.ch).

Authorship

Contribution: A.A.M., C.T., and E.Z performed research and analyzed data; C.T. and M.G. designed the study and performed research; A.A.M. and E.Z wrote the manuscript; S.S., S.R., and S.H performed statistical analyses and contributed to data analyses and interpretation; C.B.R. coordinated the trial; C. Ruegsegger and C. Rusterholz provided administrative support and contributed to data collection and management; and all authors contributed to patient management or data collection, reviewed and approved the manuscript, and share final responsibility for the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict--interest disclosure: A.A.M. has served on advisory boards for Roche, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Takeda. F.H. has served on the advisory board for Roche. M.G. has received honoraria from Roche, Gilead Sciences, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, and Mundipharma. E.Z. has received research funding from Celgene, Roche, and Janssen Pharmaceuticals; has served on advisory boards for Celgene, Roche, Mei Pharma, AstraZeneca, and Celltrion Healthcare; has had travel expenses to meetings paid by AbbVie and Gilead Sciences, and has provided expert statements to Gilead Sciences, Bristol Myers Squibb, and MSD. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Alden A. Moccia, Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana, Clinica di Oncologia Medica, Ospedale San Giovanni, 6500 Bellinzona, Switzerland; e-mail: alden.moccia@eoc.ch.

References

- 1.Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107(1):265-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Casulo C, Byrtek M, Dawson KL, et al. Early relapse of follicular lymphoma after rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone defines patients at high risk for death: an analysis from the National LymphoCare Study [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 20;34(12):1430]. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(23):2516-2522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghielmini M, Schmitz SF, Cogliatti SB, et al. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event-free survival and response duration compared with the standard weekly x 4 schedule. Blood. 2004;103(12):4416-4423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martinelli G, Schmitz SF, Utiger U, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with follicular lymphoma receiving single-agent rituximab at two different schedules in trial SAKK 35/98. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4480-4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taverna C, Martinelli G, Hitz F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for a maximum of 5 years after single-agent rituximab induction in follicular lymphoma: results of the randomized controlled phase III trial SAKK 35/03. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):495-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lockmer S, Østenstad B, Hagberg H, et al. Chemotherapy-free initial treatment of advanced indolent lymphoma has durable effect with low toxicity: results from two Nordic Lymphoma Group trials with more than 10 years of follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(33):3315-3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimby E, Jurlander J, Geisler C, et al. ; Nordic Lymphoma Group . Long-term molecular remissions in patients with indolent lymphoma treated with rituximab as a single agent or in combination with interferon alpha-2a: a randomized phase II study from the Nordic Lymphoma Group. Leuk Lymphoma. 2008;49(1):102-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kimby E, Östenstad B, Brown P, et al. ; Nordic Lymphoma Group (NLG) . Two courses of four weekly infusions of rituximab with or without interferon-α2a: final results from a randomized phase III study in symptomatic indolent B-cell lymphomas. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56(9):2598-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zucca E, Rondeau S, Vanazzi A, et al. ; Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research and the Nordic Lymphoma Group . Short regimen of rituximab plus lenalidomide in follicular lymphoma patients in need of first-line therapy. Blood. 2019;134(4):353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karmali R, Kimby E, Ghielmini M, Flinn IW, Gordon LI, Zucca E. Rituximab: a benchmark in the development of chemotherapy-free treatment strategies for follicular lymphomas. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(2):332-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan EMP. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53(282):457-481. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. New York, NY: Springer Verlag New York; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klein JP, Logan B, Harhoff M, Andersen PK. Analyzing survival curves at a fixed point in time. Stat Med. 2007;26(24):4505-4519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salles G, Seymour JF, Offner F, et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):42-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marcus R, Davies A, Ando K, et al. Obinutuzumab for the first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1331-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr PM, Li H, Burack WR, et al. R-CHOP, radioimmunotherapy, and maintenance rituximab in untreated follicular lymphoma (SWOG S0801): a single-arm, phase 2, multicentre study. Lancet Haematol. 2018;5(3):e102-e108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyan E, Sonet A, Brice P, et al. ; Lymphoma Study Association (LYSA) . Bendamustine and rituximab in elderly patients with low-tumour burden follicular lymphoma. Results of the LYSA phase II BRIEF study. Br J Haematol. 2018;183(1):76-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachy E, Houot R, Morschhauser F, et al. ; Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) . Long-term follow up of the FL2000 study comparing CHVP-interferon to CHVP-interferon plus rituximab in follicular lymphoma. Haematologica. 2013;98(7):1107-1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachy E, Seymour JF, Feugier P, et al. Sustained progression-free survival benefit of rituximab maintenance in patients with follicular lymphoma: long-term results of the PRIMA Study. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2815-2824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luminari S, Ferrari A, Manni M, et al. Long-term results of the FOLL05 Trial comparing R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage symptomatic follicular lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):689-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morschhauser F, Radford J, Van Hoof A, et al. 90Yttrium-ibritumomab tiuxetan consolidation of first remission in advanced-stage follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: updated results after a median follow-up of 7.3 years from the international, randomized, phase III First-LineIndolent trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(16):1977-1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nastoupil LJ, McLaughlin P, Feng L, et al. High ten-year remission rates following rituximab, fludarabine, mitoxantrone and dexamethasone (R-FND) with interferon maintenance in indolent lymphoma: results of a randomized Study. Br J Haematol. 2017;177(2):263-270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rummel MJ, Maschmeyer G, Ganser A, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab (B-R) versus CHOP plus rituximab (CHOP-R) as first-line treatment in patients with indolent lymphomas: nine-year updated results from the StiL NHL1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15 suppl):7501. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shadman M, Li H, Rimsza L, et al. Continued excellent outcomes in previously untreated patients with follicular lymphoma after treatment with CHOP plus rituximab or CHOP Plus 131I-tositumomab: long-term follow-up of phase III randomized study SWOG-S0016. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(7):697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardeshna KM, Qian W, Smith P, et al. Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):424-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kahl BS, Hong F, Williams ME, et al. Rituximab extended schedule or re-treatment trial for low-tumor burden follicular lymphoma: eastern cooperative oncology group protocol e4402. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3096-3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]