Dear Editor,

Recent articles in this Journal have described the usefulness of saliva to detect SARS-CoV-2 infection through real-time reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) [1,2]. We analyzed the performance of antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests (Ag-RDT) in saliva and nasal samples.

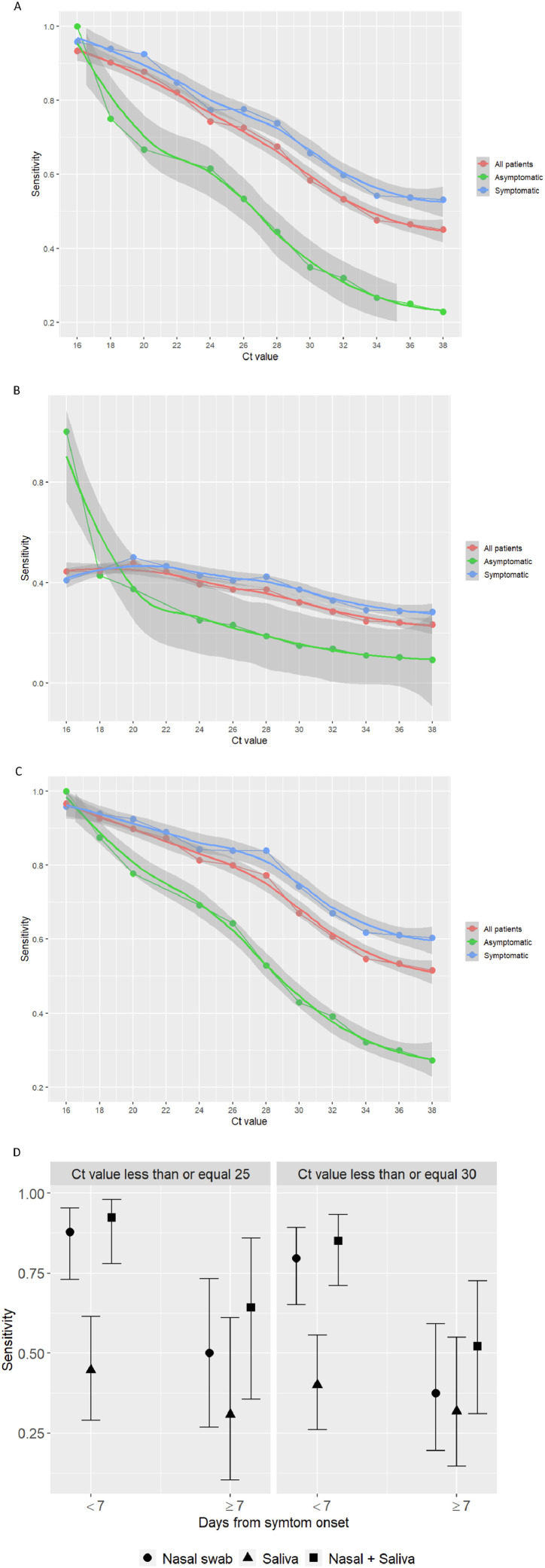

Ag-RDT directly identify SARS-CoV-2 proteins produced by replicating virus in respiratory secretions [3]. In contrast to the reference nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT), such as rRT-PCR, the Ag-RDT are relatively inexpensive, simple to perform, do not require infrastructure, and enable obtaining point-of-care results within a few minutes [4]. Accordingly, despite being less sensitive than NAAT, Ag-RDT are more advantageous for guiding patient management at point-of-care, repeat testing, and timely large-scale public health decisions to prevent transmission [5,6]. Panbio COVID-19 Ag-RTD (Abbott Rapid Diagnostic Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) is a recent generation, highly sensitive and specific antigen test for the qualitative detection of SARS-CoV-2 antigen in human nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) specimens. Because obtaining a NPS requires trained healthcare professionals and a personal protective equipment (PPE), availability of a simpler and accurate alternative sample that could even be self-collected, like nasal swab (NS) or saliva, would further ease the procedure and allow large-scale testing. We evaluated the performance of Panbio COVID-19 Ag-RDT in NS and saliva specimens compared with rRT-PCR in NPS in a large prospective study conducted in three primary care centers between 15th September and 29th October 2020. Consecutive adults and children, either with COVID-19 signs/symptoms or asymptomatic contacts, were included. Informed consent was obtained from all the patients, and the study was approved by the Hospital General Universitario de Elche COVID-19 Institutional Advisory Board. Patients were asked to fill a questionnaire about symptoms and to collect saliva into a 100 ml sterile empty container. Then, a NS and two consecutive NPS were obtained by a qualified nurse according to the recommended standard procedure. The antigen kit was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. rRT-PCR testing was performed according to the manufacturer's guidelines on Cobas z 480 Analyzer (Roche, Basilea, Suiza). Positive and negative percent agreement (PPA, NPA) were calculated for Panbio antigen test in the NPS, NS and saliva samples compared to the rRT-PCR test in NPS. The study included 659 patients with NS samples, of whom 610 (92.6%) had a saliva sample. 265 (40.2%) patients were asymptomatic and 394 (59.8%) had symptoms, with median (Q1-Q3) duration of 3 (2–5) days. Median (Q1-Q3) age was 38 (21–49.8) years, 76 (11.5%) had ≤14 years, 45 (7.6%) >65 years, 372 (56.4%) were women, and 157 (23.8%) had a comorbid condition, the most frequent hypertension in 46 (7%), dyslipidemia in 39 (5.9%), obesity in 29 (3.2%) and diabetes in 21 (4.4%) patients. rRT-PCR was positive in NPS in 132 (20%) patients, with median (Q1-Q3) cycle threshold (Ct) of rRT-PCR of 24 (17.6–31). Table 1 shows the performance of Ag-RDT in NS, saliva and NS/saliva. Ag-RDT was positive in 76 (11.7%), 59 (9%), 28 (4.6%) and 60 (9.1%) NPS, NS, saliva and any of NS or saliva (NS/saliva) samples, respectively. Median (Q1-Q3) Ct value in NPS of antigen-positive NS samples was 17 (14–21.5) and of antigen-negative NS samples 29.5 (25.6–33); and 17.9 (15.8–19.3) and 28 (19.6–32) in antigen-positive and antigen-negative saliva samples, respectively. The PPA (95% CI) was 57.3% (48.3–65.8) in NPS, 44.7% (36.1–53.6) in NS, 23.1% (16.2–31.9) in saliva, and 49.6% (40.4–58.8) in NS/saliva. In all cases, NPA was 100%. Ag-RDT performance was dependent on the Ct values and the presence of symptoms (Fig. 1 A-C). For symptomatic patients with Ct<25, the PPA (95% CI) was 78% (65–88) in NS, 41% (28–56) in saliva and 85% (72–93) in NS/saliva samples. Ag-RDT performed better with duration of symptoms <7 days (Fig. 1D). The best test performance was observed for NS/saliva in symptomatic patients with <7 days and Ct≤25, with PPA (95% CI) of 92% (78–98), and 85.1% (71.1–93.3) for Ct ≤ 30. In NS, PPA was 87.8% (72.9–95.4) and 79.6% (65.2–89.3) for Ct ≤ 25 and Ct ≤ 30, respectively, and <7 days with symptoms. Symptoms associated with higher sensitivity of the Ag-RDT in NS/saliva samples were sore throat, with PPA (95% CI) of 69% (49–84), and ageusia with 66% (12.5–98.2). Results from this large study show that the overall sensitivity of Panbio Ag-RDT was lower in NS and saliva than in NPS, particularly in asymptomatic patients, although the specificity was 100% in all samples. The same as with Ag-RDT in NPS, sensitivity was highly dependent on the Ct values and the presence and duration of symptoms [7]. In NS samples, the sensitivity in symptomatic patients with Ct ≤ 30 and duration of symptoms <7 days met the minimum test performance requirements to be adequate for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection [5], although the greatest performance was observed with the combination of NS and saliva samples. Therefore, although the saliva alone did not show a satisfactory performance, it added sensitivity to the NS for SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis. Infectivity risk has been associated with Ct values and duration of symptoms, with no viral growth observed in samples with PCR Ct values >25–30 [8,9], and symptom duration >8 days [9,10]. Consequently, the contagious risk of symptomatic patients not detected by the Ag-RDT in NS/saliva samples may be low. In addition to self-collection, NS and saliva samples allow performing the test without safe isolation conditions requirement to avoid propagation, thereby widening the settings where the test can be performed, and facilitating the procedure in children since it causes much less discomfort. Moreover, the same diagnostic kit could even be used to analyze both samples, through insertion of the NS in the saliva specimen. In conclusion, because of the low performance observed in asymptomatic patients, NS and saliva samples are not good options for screening or surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 with Ag-RDT. However, in settings with no availability of PPE or trained personnel, or with no safe conditions for the Ag-RDT procedure, the combination of saliva and nasal samples could be a suitable alternative to the NPS for the point-of-care diagnosis of symptomatic patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Table 1.

Performance of the Panbio COVID-19 antigen Rapid Test Device.

| Overall | TP | FP | TN | FN | PPA (95% CI) | NPA (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP sample | 76 | 1 | 519 | 56 | 57.3% (48.3–65.8) | 99.8% (98.8–100) |

| Nasal sample | 59 | 0 | 527 | 73 | 44.7% (36.1–53.6) | 100% (99.1–100) |

| Saliva sample | 28 | 0 | 489 | 93 | 23.1% (16.2–31.9) | 100% (99–100) |

| Nasal+saliva | 60 | 0 | 489 | 61 | 49.6% (40.4–58.8) | 100% (99–100) |

| Nasal sample | ||||||

| Symptomatic | 51 | 0 | 297 | 46 | 52.6% (42.2–62.7) | 100% (98.4–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 78% (65–88) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 48 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 66% (54–76) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 43 | 54% (44–64) | |

| Asymptomatic | 8 | 0 | 230 | 27 | 22.9% (11–40.6) | 100% (98–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 62% (32–85) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 35% (17–57) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 25% (0–69) | |

| Saliva sample | ||||||

| Symptomatic | 25 | 0 | 277 | 64 | 28.1% (19.3–38.8) | 100% (98.3–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 41% (28–56) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 37% (26–50) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 29% (20–40) | |

| Asymptomatic | 3 | 0 | 212 | 29 | 9.4% (2.5–2.6) | 100% (97.8–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 25% (7–57) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 15% (4–39) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 10% (3–28) | |

| Nasal+saliva | ||||||

| Symptomatic | 55 | 0 | 277 | 37 | 58.4% (47.5–68.6) | 100% (98.3–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 45 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 85% (72–93) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 74% (62–84) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 55 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 62% (51–72) | |

| Asymptomatic | 9 | 0 | 212 | 24 | 27.3% (13.9–45.8) | 100% (97.8–100) |

| Ct ≤ 25 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 69% (39–90) | |

| Ct ≤ 30 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 43% (23–66) | |

| Ct ≤ 35 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 30% (0–69) | |

Unless specified, all analyses have been performed in nasopharyngeal samples. TP, true positive; FP, false positive; TN, true negative; FN, false negative; PPA, positive percent agreement; NPA, negative percent agreement; NP, nasopharyngeal; Ct, cycle threshold of RT-PCR.

Fig. 1.

Performance of Panbio COVID-19 antigen Rapid Test Device in nasal, saliva and nasal + saliva samples according to the presence of symptoms and cycle threshold values. A: Performance in nasal samples. B: Performance in saliva samples. C: Performance in nasal + saliva samples. D: Performance in symptomatic patients according to cycle threshold values and days from symptom onset.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

Members of the COVID19-Elx-Rapid Diagnostic Tests Study Group

Félix Gutiérrez, Mar Masiá, Sergio Padilla, Guillermo Telenti, Lucia Guillen, Cristina Bas, María Andreo, Fernando Lidón, Vladimir Ospino, José López, Marta Fernández, Vanesa Agulló, Gabriel Estañ, Javier García, Cristina Martínez, Leticia Alonso, Joan Sanchís, Ángela Botella, Paula Mascarell, María Selene Falcón, Sandra Ruiz, José Carlos Asenjo, Carolina Ding, Mar Carvajal, Inmaculada Candela, Jorge Guijarro, Cristina la Moneda, Cristina Jara, Raquel Mora, Juan Manuel Quinto, Sergio Ros, Daniel Canal, Pascual Pérez, Montserrat Ruiz, Alba de la Rica, Carolina Garrido, Manuel Sánchez, Jaime Sastre, Carlos de Gregorio, Francisco Carrasco, Juan Navarro, Andrés Navarro, Nieves Gonzalo, Clara Pérez, Adoración Alcalá, José Luis Rincón, Juan Antonio Gutiérrez.

Funding

This work was supported by the RD16/0025/0038 project as a part of the Plan Nacional Research + Development + Innovation (R + D + I) and cofinanced by Instituto de Salud Carlos III - Subdirección General de Evaluación y Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional; Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias [grant number PI16/01740; PI18/01861; CM 19/00160, COV20–00005]).

References

- 1.Azzi L., Carcano G., Gianfagna F., et al. Saliva is a reliable tool to detect SARS-CoV-2. J Infect. 2020;81:e45–e50. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.005. [PMID: 32298676] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwasaki S., Fujisawa S., Nakakubo S., et al. Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 detection in nasopharyngeal swab and saliva. J Infect. 2020;81:e145–e147. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.071. [PMID: 32504740] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.La Marca A., Capuzzo M., Paglia T., et al. Testing for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19): a systematic review and clinical guide to molecular and serological in-vitro diagnostic assays. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020;41:483–499. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2020.06.001. [PMID: 32651106] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young S., Taylor S.N., Cammarata C.L., et al. Clinical evaluation of BD Veritor SARS-CoV-2 point-of-care test performance compared to PCR-based testing and versus the Sofia 2 SARS Antigen point-of-care test. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JCM.02338-20. [PMID: 330239] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antigen-detection in the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection using rapid immunoassays. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/antigen-detection-in-the-diagnosis-of-sars-cov-2infection-using-rapid-immunoassays.

- 6.Interim Guidance for Rapid Antigen Testing for SARS-CoV-2. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/resources/antigen-tests-guidelines.html#:∼:text=CDC%20recommends%20that%20laboratory%20and,the%20previous%207%E2%80%9310%20days.

- 7.Lambert-Niclot S., Cuffel A., Le Pape S., et al. Evaluation of a Rapid Diagnostic Assay for Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antigen in Nasopharyngeal Swabs. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58:e00977. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00977-20. -20[PMID: 32404480] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gniazdowski V., Morris C.P., Wohl S., et al. Repeat COVID-19 Molecular Testing: correlation of SARS-CoV-2 Culture with Molecular Assays and Cycle Thresholds. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1616. [PMID: 33104776] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullard J., Dust K., Funk D., et al. Predicting infectious SARS-CoV-2 from diagnostic samples. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa638. [PMID: 32442256] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wölfel R., Corman V.M., Guggemos W., et al. (2020). Virological assessment of hospitalized patients with COVID-2019. Nature. 2020;581:465–469. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2196-x. [PMID: 32235945] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]