Abstract

RalA protein, a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases, is a tumor antigen that induces serum RalA antibodies (s-RalA-Abs). The present study explored the clinicopathological and prognostic significance of s-RalA-Abs in patients with colorectal cancer. Serum samples were obtained from 314 patients with colorectal cancer at stage 0/I (n=71), stage II (n=86), stage III (n=78), stage IV (n=64) and recurrence (n=15). Samples were analyzed for the presence of s-RalA-Abs using ELISA. The cutoff optical density value was fixed at 0.324 (mean of heathy controls + 3 standard deviations). The overall positive rate for serum anti-RalA antibodies was 14%. The presence of s-RalA-Abs was not significantly associated with clinicopathological characteristic factors. Additionally, the s-RalA-Abs(+) group demonstrated significantly poor relapse-free survival rates. The s-RalA-Abs (+)/carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)(+) group exhibited the worst prognosis and s-RalA-Abs(+)/CEA(+) was an independent risk factor for poor relapse-free survival. Although the positive rate was not high, s-RalA-Abs may be a useful predictor of poor relapse-free survival in patients with colorectal cancer.

Keywords: RalA, autoantibody, tumor antigen, colorectal cancer, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9

Introduction

RalA is a member of the Ras superfamily of small GTPases (1). The Ras-like GTPases are tumor antigens that are aberrantly induced during tumorigenesis by oncogenic Ras (2). Human cancers often contain RAS mutations (3), and 37.9-49.6% of colorectal cancers contain RAS mutations (4). RalA protein has been studied in various cancers (5), including colorectal cancer (6). RalA protein have been reported as key cancer phenotypic markers and biomarkers of cellular migration, invasion and metastasis (7,8).

We previously reported that serum IgG autoantibodies were useful for detecting early-stage colorectal cancer (9), monitoring treatment response, and monitoring after surgery (10-12). Serum RalA antibodies (s-RalA-Abs) have been reported to be a potential biomarker for various cancers (9,13-15). However, previous reports rather than our own reports (16,17), did not reveal details of the clinicopathological and prognostic significance. Furthermore, the relationship between the conventional serum markers, CEA and CA19-9, has not been analyzed.

Therefore, we evaluated the clinicopathological and prognostic significance of s-RalA-Abs status in colorectal cancer patients. Moreover, the use of combinatorial assays of s-RalA-Abs with CEA and/or CA19-9 was evaluated for their clinical impact.

Materials and methods

Patients

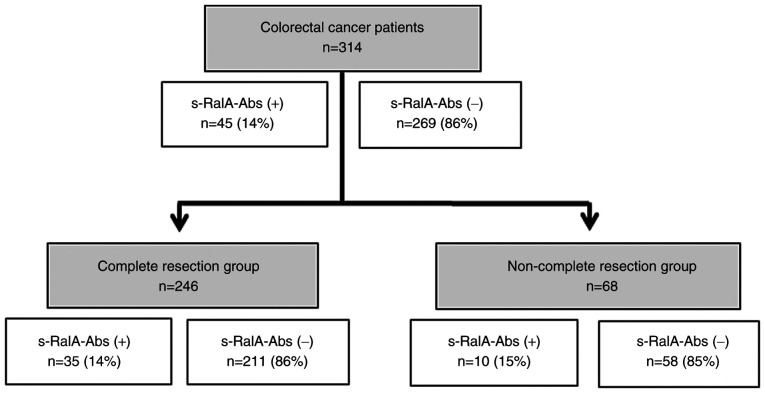

A total of 314 patients with colorectal cancer, including 165 patients from Toho University Omori Medical Center and 149 patients from Chiba Cancer Center, were analyzed to detect serum antibodies against RalA. Samples from 73 healthy controls were also obtained. Among the 314 patients, 194 were men (61.8%) and 120 were women (38.2%), with a median age of 66 (range, 27-90) years. The TNM stage of colorectal cancer was classified according to the General Rules for the Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Colorectal Cancer (7th Edition) (18). All patients were classified as stage 0 (n=10), stage I (n=61), stage II (n=86), stage III (n=78), stage IV (n=64), or recurrence (n=15). Serum RalA antibodies (s-RalA-Abs), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) were evaluated to compare clinicopathological significance. A flowchart showing the patient subgroups and s-RalA-Abs status is shown in Fig. 1. Written informed consent to publish any associated data was provided and obtained from all study participants.

Figure 1.

Flowchart demonstrating patient selection for the present study.

Analysis of s-RalA-Abs, CEA, and CA19-9

Serum samples were analyzed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described (19) using 96-well microtiter plates coated with purified recombinant RalA protein. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a SUNRISE Microplate Reader (Tecan Japan Co., Ltd.) (20). An optimized antibody titer cutoff value and a standard cutoff value corresponding to a value greater than that of the mean of the healthy control cohort plus three standard deviations were applied to RalA antibodies, and specificity was maintained at over 95% (21). The optical density cutoff value was fixed at 0.324. Details of the three standard deviations of autoantibody titers were described previously (22). The assay specificity was calculated as the percentage of the healthy controls showing a negative result. CEA and CA19-9 were measured as previously described (14).

Statistical analysis

Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the categorical variables. The age of the continuous variable in Table I was divided into two groups: Over or under 65 years old. Older age was analyzed using Fisher's exact as a single category. In figures, Fisher's exact was used to analyze the noteworthy positive rate between the two groups for comparison. Clinicopathological parameters associated with survival were evaluated by univariate analysis using log-rank test based on the Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Multivariate analyses were performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR statistical software (23). P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table I.

Comparison of clinicopathological features among 314 patients with colorectal cancer according to s-RalA-Abs status.

| Variable | Total number (n=314) | s-RalA-Abs positive (n=45) | s-RalA-Abs negative (n=269) | P-valuee |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.75 | |||

| ≥65 | 172 | 26 | 146 | |

| <65 | 142 | 19 | 123 | |

| Sex | 0.51 | |||

| Male | 194 | 30 | 164 | |

| Female | 120 | 15 | 105 | |

| Locationa | 0.73 | |||

| Rectum | 107 | 16 | 91 | |

| Colon | 192 | 25 | 167 | |

| Tumor depthb | 0.64 | |||

| T4 | 46 | 7 | 39 | |

| T1,T2,T3 | 234 | 30 | 204 | |

| Lymph node metastasisc | 0.59 | |||

| Positive | 116 | 17 | 99 | |

| Negative | 166 | 20 | 146 | |

| Stage | 0.29 | |||

| 0/I | 71 | 6 | 65 | |

| II | 86 | 14 | 72 | |

| III | 78 | 13 | 65 | |

| IV | 64 | 8 | 56 | |

| Recurrence | 15 | 4 | 11 | |

| Complete resection | ||||

| No | 68 | 10 | 58 | 1.00 |

| Yes | 246 | 35 | 211 | |

| Histologyd | ||||

| Muc, Por | 18 | 0 | 18 | 0.087 |

| Tub1, Tub2 | 285 | 43 | 242 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | ||||

| No | 79 | 10 | 69 | 0.22 |

| Yes | 85 | 17 | 68 | |

| CEA (cut off, 5.0 ng/ml) | ||||

| Positive | 129 | 21 | 108 | 0.42 |

| Negative | 185 | 24 | 161 | |

| CA19-9 (cut off, 37.0 U/ml) | ||||

| Positive | 59 | 7 | 52 | 0.69 |

| Negative | 255 | 38 | 217 |

aexclude rec., n=15;

bexclude rec., n=15 and unknown, n=19;

cexclude rec., n=15 and unknown, n=17;

dexclude unknown, n=11;

eFischer's exact probability test.

Results

Comparison of clinicopathological features in colorectal cancer patients according to s-RalA-Abs status

Among 314 patients with colorectal cancer, 45 (14%) were positive for s-RalA-Abs (Fig. 1). The positive rate of s-RalA-Abs in 246 patients in the complete resection (R0) group was 14%. The presence of s-RalA-Abs was slightly associated with differentiated type (P=0.087). No other clinicopathological factors were significantly associated with s-RalA-Abs (Table I). Furthermore, the presence of s-RalA-Abs was not significantly associated with CEA and CA19-9.

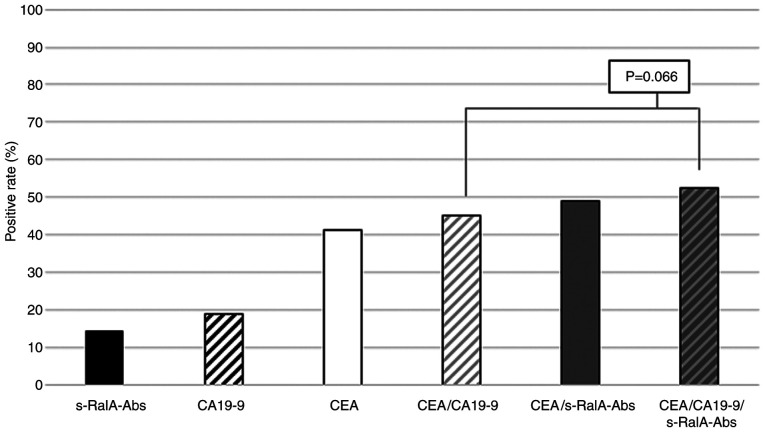

Positive rates of combined s-RalA-Abs, CEA and CA19-9

The positive rates of s-RalA-Abs, CA19-9 and CEA in all 314 patients were 14, 19 and 41%, respectively (Fig. 2). The positive rate of combined CEA/s-RalA-Abs was higher than that of combined CEA/CA19-9. Furthermore, the positive rate of combined CEA/CA19-9/s-RalA-Abs was higher than that of combined CEA/CA19-9 (53 vs. 45%, P=0.066) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Positive rates for combined serum RalA antibodies, CEA and CA19-9 in all patients. The positive rate was 53% for all three markers in all patients. The positive rate of combined CEA/s-RalA-Abs was higher than that of combined CEA/CA19-9, although the difference was not statistically significant. CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9; s-RalA-Abs, serum RalA antibodies.

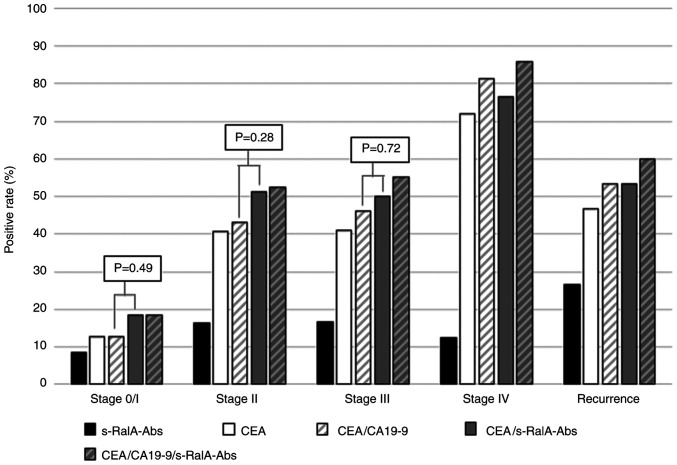

Positive rates of serum markers in colorectal cancer patients according to stage

There was no significant difference in the positive rates of s-RalA-Abs among the stage 0/I-IV, and recurrence groups (8, 16, 17, 13 and 27%, respectively). The positive rates of combined CEA/s-RalA-Abs were higher than that of combined CEA/CA19-9 in stage 0/I, II and III, although the differences were not statistically significant (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Positive rates for serum markers in patients with colorectal cancer according to stage. In patients at stage 0/I, the positive rates of s-RalA-Abs, CEA, CEA/CA19-9, CEA/s-RalA-Abs and CEA/CA19-9/s-RalA-Abs were 8, 13, 13, 18 and 18%, respectively. At stage 0/I, II, and III, the positive rates of combined CEA/s-RalA-Abs were higher than that of combined CEA/CA19-9, although the differences were not statistically significant. s-RalA-Abs, serum RalA antibodies; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

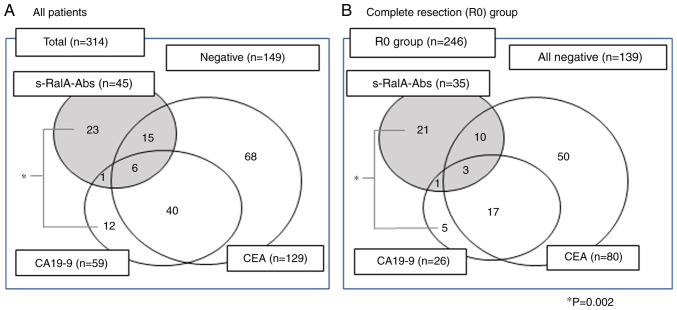

Correlation between s-RalA-Abs, CEA, and CA19-9

Positive tumor markers were found in 165 out of 314 (52.5%) patients in total (Fig. 4A). Among s-RalA-Abs-positive patients, 23 out of 45 (51%) were positive for s-RalA-Abs only. On the other hand, among CA19-9-positive patients, 12 out of 59 (20%) were positive for CA19-9 only. This tendency was also found in the complete resection group (Fig. 4B). Among s-RalA-Abs-positive patients, 21 out of 35 (60%) were positive for s-RalA-Abs only. On the other hand, among CA19-9-positive patients, 5 out of 26 (19%) were positive for CA19-9 only. The s-RalA-Abs single positive rate was significantly higher than that for CA19-9 (P=0.002).

Figure 4.

Relationship between serum RalA antibodies, CEA, and CA19-9 status. (A) Total number of patients (n=314). (B) Total number of patients with complete tumor resection (n=246). The single-positive rate of s-RalA-Abs was significantly higher than that of CA19-9 (*P=0.002). R0, complete resection. P-value: Fischer's exact probability test.

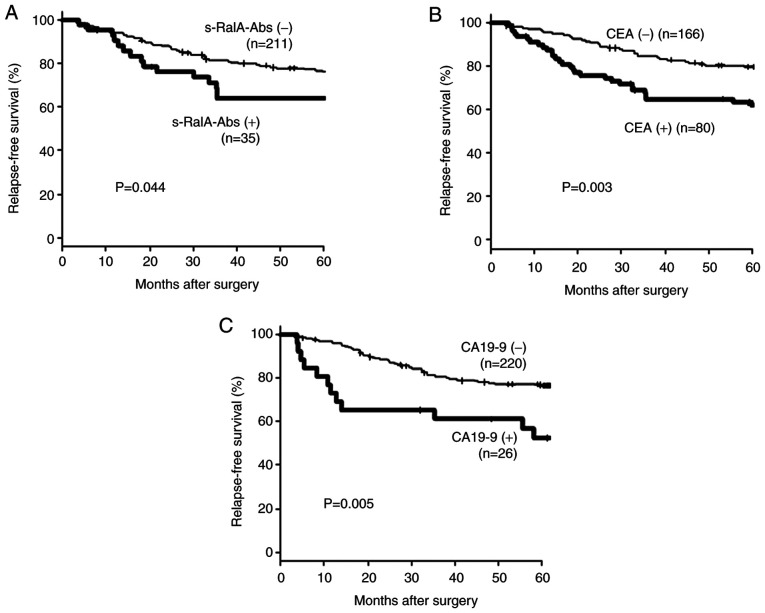

Relapse-free survival in patients in the completed resection group

Fig. 5 shows the relapse-free survival of 246 patients with complete resection according to the preoperative serum marker status. Patients with a positive preoperative status for tumor markers were significantly associated with poor prognosis.

Figure 5.

Relapse-free survival of the complete resection group according to serum marker status (n=246). A total of 246 patients underwent completed resection. Relapse-free survival according to (A) s-RalA-Abs, (B) CEA and (C) CA19-9 status is presented. Patients with a positive preoperative tumor marker status were significantly associated with poor prognosis. s-RalA-Abs, serum RalA antibodies; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; CA19-9, carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

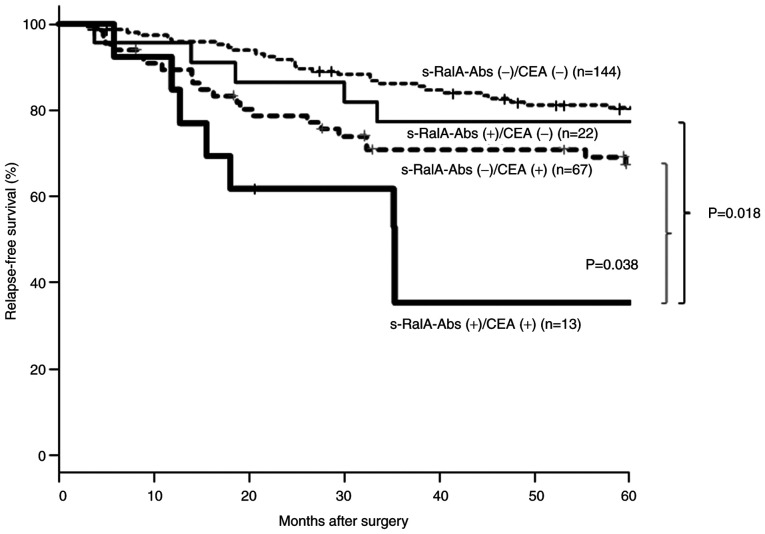

Relapse-free survival according to tumor marker combination status for patients in the complete resection group

Fig. 6 shows a comparison of relapse-free survival according to tumor marker combination status. Among CEA(-) patients, the s-RalA-Abs(+) group showed worse relapse-free survival than the s-RalA-Abs(-) group; however, the difference was not statistically significant. On the other hand, in the CEA (+) groups, the s-RalA-Abs(+) group showed significantly worse relapse-free survival than that of the RalA-Abs(-) group (P=0.038). The double-positive s-RalA-Abs(+)/CEA(+) group showed the worst relapse-free survival.

Figure 6.

Relapse-free survival of the complete resection group according to s-RalA-Abs and CEA status. Among patients with a status of CEA (+), the s-RalA-Abs (+) group demonstrated significantly poorer relapse-free survivals than the-RalA-Abs (-) group (P=0.038). The double-positive s-RalA-Abs (+)/CEA (+) group demonstrated the poorest relapse-free survival. s-RalA-Abs, serum RalA antibodies; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of risk factors for relapse-free survival in the complete resection group

Table II shows the association of risk factors with relapse-free survival. Univariate and multivariate analyses revealed that T4, lymph node metastasis, and CEA(+)/s-RalA-Abs(+) double-positivity were significant poor risk factors for reduced relapse-free survival.

Table II.

Analysis of the risk factors associated with relapse-free survival in patients with colorectal cancer patients with complete resection (n=246).

| Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total number | P-valuee | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P-valuef |

| Age (years) | 0.51 | ||||

| ≥65 | 109 | ||||

| <65 | 137 | ||||

| Sex | 0.11 | 1.65 | 0.97-2.80 | 0.063 | |

| Male | 148 | ||||

| Female | 98 | ||||

| Locationa | 0.48 | ||||

| Rectum | 83 | ||||

| Colon | 156 | ||||

| Tumor depthb | <0.001 | 2.29 | 1.18-4.45 | 0.015 | |

| T4 | 22 | ||||

| T1,T2,T3 | 217 | ||||

| Lymph node metastasisc | <0.001 | 2.84 | 1.71-4.71 | <0.001 | |

| Positive | 83 | ||||

| Negative | 156 | ||||

| Histrogyd | 0.24 | ||||

| Muc, Por | 12 | ||||

| Tub1, Tub2 | 232 | ||||

| s-RalA-Abs (+)/CEA (+) | <0.001 | 2.35 | 1.06-5.20 | 0.035 | |

| Yes | 13 | ||||

| No | 233 | ||||

| CEA(+)/CA19-9(+) | 0.071 | 1.75 | 0.74-4.13 | 0.20 | |

| Yes | 17 | ||||

| No | 229 | ||||

aexclude rec., n=7;

bexclude rec., n=7;

cexclude rec., n=7;

dexclude unknown, n=2;

eLog-rank test;

fCox proportional hazards model. CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

The overall s-RalA-Abs positive rate was 14% in colorectal cancer patients. However, s-RalA-Abs status was not associated with any clinicopathological factors and was not associated with CEA and CA19-9 status. Combined CEA/s-RalA-Abs and CEA/CA19-9/s-RalA-Abs showed higher positive rates than CEA/CA19-9; however, this difference did not reach statistical significance. The s-RalA-Abs(+) group showed poor relapse-free survival, particularly in the CEA(+) group.

The s-RalA-Abs positive rate was not high using a single biomarker. Since s-RalA-Abs was independent of CEA or CA19-9, it could be useful to apply this in combination with CEA. Although the s-RalA-Abs positive rates in patients with esophageal cancer gradually increased in association with tumor stages (13), we were unable to confirm a similar tendency in colorectal cancer patients. In the present study, the s-RalA-Abs positive rate of stage 0/I/II was similar to that of stage III/IV.

Although s-RalA-Abs was not associated with tumor stage, the s-RalA-Abs(+) group showed a significantly poor relapse-free survival. The malignant potential of RalA(+) cancer cells was partly explained by the biological effects of the RalA molecule on cancer progression and/or metastases (24,25). Interestingly, these effects of s-RalA-Abs seemed to be limited in the CEA(+) group. However, the potential mechanisms for the biological effects of RalA/s-RalA-Abs remain unclear.

The present study has two major limitations. First, s-RalA-Abs titers were not monitored after surgery. Previous studies based on s-p53-Abs monitoring after surgery showed that the presence of s-p53-Abs, even after surgery, indicated residual cancer cells (26). Therefore, further assessment should be performed in future. Second, there was a lack of data for RalA immunoreactivity of the tumor cells. Since RalA is a tumor antigen that induces serum antibodies, there may have been tumor cell overexpression of RalA protein in the sera of the s-RalA-Abs(+) group. Such a positive association has been confirmed in patients with esophageal cancer (13).

In conclusion, although the positive rate was not high, s-RalA-Abs may be a candidate biomarker to detect colorectal cancer and may also be a useful predictor of poor relapse-free survival in colorectal cancer patients after curative resection.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms. Seiko Otsuka (Toho University) for her support with sampling and data presentation for the current study.

Funding

The present study was supported by a research grant from JSPS KAKENHI (grant no. JP26462029).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

MU, HSh and YN conceived and designed the current study. MU, HSo, NT, TK and KF acquired patient samples. MU, HSo, NT, TK and KF contributed to the acquisition of the patient's clinicopathological data. AK supported the development of the ELISA system used to measure antibody titers. MU, FS, IH and HSh analyzed patient data. MU and HSh drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and patient consent to participate

The present study was performed in adherence to the international and national regulations in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants for sampling, analyses and publication. The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Toho University Omori Medical Center (approval nos. 26-255 and M19213) and the Chiba Cancer Center (approval no. 30-220).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish any associated data was provided and obtained from all study participants.

Competing interests

HSh received a research grant from Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd. AK is an employee of Medical & Biological Laboratories Co., Ltd.. All other authors declare that there they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Shirakawa R, Horiuchi H. Ral GTPases: Crucial mediators of exocytosis and tumorigenesis. J Biochem. 2015;157:285–299. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moghadam AR, Patrad E, Tafsiri E, Peng W, Fangman B, Pluard TJ, Accurso A, Salacz M, Shah K, Ricke B, et al. Ral signaling pathway in health and cancer. Cancer Med. 2017;6:2998–3013. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Hyperactive ras in developmental disorders and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo TA, Wu YC, Tan C, Jin YT, Sheng WQ, Cai SJ, Liu FQ, Xu Y. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic value of KRAS, NRAS and BRAF mutations and DNA mismatch repair status: A single-center retrospective study of 1,834 Chinese patients with stage I-IV colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019;15:1625–1634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan C, Theodorescu D. RAL GTPases: Biology and potential as therapeutic targets in cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2018;70:1–11. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin TD, Samuel JC, Routh ED, Der CJ, Yeh JJ. Activation and involvement of ral GTPases in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:206–215. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oxford G, Owens CR, Titus BJ, Foreman TL, Herlevsen MC, Smith SC, Theodorescu D. RalA and RalB: Antagonistic relatives in cancer cell migration. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7111–7120. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith SC, Baras AS, Owens CR, Dancik G, Theodorescu D. Transcriptional signatures of ral GTPase are associated with aggressive clinicopathologic characteristics in human cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3480–3491. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ushigome M, Nabeya Y, Soda H, Takiguchi N, Kuwajima A, Tagawa M, Matsushita K, Koike J, Funahashi K, Shimada H. Multi-panel assay of serum autoantibodies in colorectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2018;23:917–923. doi: 10.1007/s10147-018-1278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda A, Shimada H, Nakajima K, Imaseki H, Suzuki T, Asano T, Ochiai T, Isono K. Monitoring of p53 autoantibodies after resection of colorectal cancer: Relationship to operative curability. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:50–53. doi: 10.1080/110241501750069828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suzuki T, Shimada H, Ushigome M, Koike J, Funahashi K, Nemoto T, Kaneko H. Three-year monitoring of serum p53 antibody during chemotherapy and surgery for stage IV rectal cancer. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:55–58. doi: 10.1007/s12328-016-0633-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ushigome M, Shimada H, Miura Y, Yoshida K, Kaneko T, Koda T, Nagashima Y, Suzuki T, Kagami S, Funahashi K. Changing pattern of tumor markers in recurrent colorectal cancer patients before surgery to recurrence: Serum p53 antibodies, CA19-9 and CEA. Int J Clin Oncol. 2020;25:622–632. doi: 10.1007/s10147-019-01597-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nanami T, Shimada H, Yajima S, Oshima Y, Matsushita K, Nomura F, Nagata M, Tagawa M, Otsuka S, Kuwajima A, Kaneko H. Clinical significance of serum autoantibodies against ras-like GTPases, RalA, in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Esophagus. 2016;13:167–172. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang P, Qin J, Ye H, Li L, Wang X, Zhang J. Using a panel of multiple tumor-associated antigens to enhance the autoantibody detection in the immunodiagnosis of ovarian cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120:3091–3100. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubota Y, Ogata H, Otsuka S, Kuwajima A, Saito F, Shimada H. Presence of autoantibodies against ras-like GTPases in serum in stage I/II breast cancer. Toho J Med. 2017;3:125–130. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okada R, Otsuka Y, Wakabayashi T, Shinoda M, Aoki T, Murakami M, Arizumi S, Yamamoto M, Aramaki O, Takayama T, et al. Six autoantibodies as potential serum biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective multicenter study. Int J Cancer. 2020;23(1002) doi: 10.1002/ijc.33165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nanami T, Hoshino I, Ito M, Yajima S, Oshima Y, Suzuki T, Shiratori F, Nabeya Y, Funahashi K, Shimada H. Prevalence of autoantibodies against ras-like GTPases, RalA, in patients with gastric cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2020;13(28) doi: 10.3892/mco.2020.2098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, Fritz AG, Greene FL, Trotti A (eds) AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edition. Springer, New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y, Karjalainen A, Koskinen H, Hemminki K, Vainio H, Shnaidman M, Ying Z, Pukkala E, Brandt-Rauf PW. P53 autoantibodies predict subsequent development of cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:157–160. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoshino I, Nagata M, Takiguchi N, Nabeya Y, Ikeda A, Yokoi S, Kuwajima A, Tagawa M, Matsushita K, Satoshi Y, Hideaki S. Panel of autoantibodies against multiple tumor-associated antigens for detecting gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:308–315. doi: 10.1111/cas.13158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang JY, Casiano CA, Peng XX, Koziol JA, Chan EL, Tan EM. Enhancement of antibody detection in cancer using panel of recombinant tumor-associated antigens. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:136–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okada R, Shimada H, Tagawa M, Matsushita K, Otsuka Y, Kuwajima A, Kaneko H. Profiling of serum autoantibodies in Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Toho J Med. 2017;3:84–92. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2013;48:452–458. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2012.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tchevkina E, Agapova L, Dyakova N, Martinjuk A, Komelkov A, Tatosyan A. The small G-protein RalA stimulates metastasis of transformed cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:329–335. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan C, Liu D, Li L, Wempe MF, Guin S, Khanna M, Meier J, Hoffman B, Owens C, Wysoczynski CL, et al. Discovery and characterization of small molecules that target the GTPase ral. Nature. 2014;515:443–447. doi: 10.1038/nature13713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shimada H, Okazumi S, Matsubara H, Shiratori T, Akutsu Y, Nabeya Y, Tanizawa T, Matsushita K, Hayashi H, Isono K, Ochiai T. Long-term results after dissection of positive thoracic lymph nodes in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. World J Surg. 2008;32:255–261. doi: 10.1007/s00268-007-9213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.