Abstract

B cells mediate humoral immune response and contribute to the regulation of cellular immune response. Members of the Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-κB) family of transcription factors play a major role in regulating B-cell functions. NF-κB subunit c-Rel is predominantly expressed in lymphocytes, and in B cells, it is required for survival, proliferation, and antibody production. Dysregulation of c-Rel expression and activation alters B-cell homeostasis and is associated with B-cell lymphomas and autoimmune pathologies. Based on its essential roles, c-Rel may serve as a potential prognostic and therapeutic target. This review summarizes the current understanding of the multifaceted role of c-Rel in B cells and B-cell diseases.

Keywords: B lymphocytes, Transcription, Antibody production, Lymphoma, Autoimmunity

Introduction

The Nuclear Factor kappaB (NF-κB) family of proteins are evolutionarily conserved transcription factors that act as master regulators of the immune cell functions. It was first identified in 1986 as a protein that binds light-chain enhancer in B cells [1]. Mammalian NF-κB family consists of five functionally distinct members-NF-κB1 (p105 and its processed form p50), NF-κB2 (p100 and its processed form p52), RelA (p65), RelB, and c-Rel. These five subunits form 15 homo- or hetero-dimer functional complexes, of which the unique dimer RelB/p52 has been classified as alternate or non-canonical pathway of NF-κB activation, while all others constitute the classical or canonical pathway [2, 3]. These dimers regulate the expression of a wide array of genes involved in the regulation of immune responses, lymphoid cell proliferation, apoptosis, and differentiation [4].

c-Rel is unique among the members of the NF-κB family in that it shares homology with the avian counterpart Rev-T retroviral oncoprotein v-Rel [5]. c-Rel is highly expressed in B and T cells and thus believed to play a major role in lymphoid cells. Initial studies of c-Rel knockout (c-Rel KO) mice showed its role in mature B cells such as proliferation and immune function. c-Rel exists as homodimer or hetero-dimer, commonly with the canonical NF-κB pathway members, p50, p65, or p52, and they bind κB sites in the target gene to promote gene expression. However, several findings also suggest that it represses the expression of NF-κB target genes in T cells [6], B cells [7, 8], as well as in fibroblasts [9]. The activity of c-Rel in lymphocytes is regulated at multiple levels including its transcription, nuclear accumulation, dimerization with other subunits, as well as posttranslational mechanisms [10].

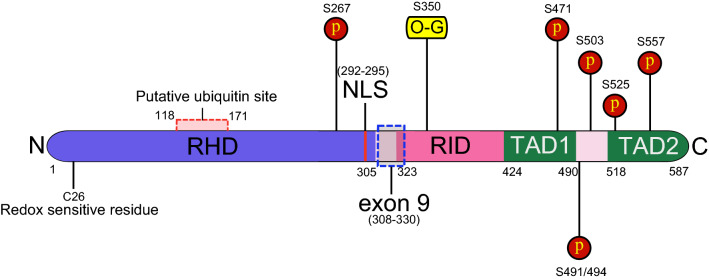

c-Rel protein structure consists of an N-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD), followed by Rel inhibitory domain (RID) and two c-terminal transcriptional activation domains (TAD) (Fig. 1). RHD is a highly conserved domain required for DNA binding, dimerization, nuclear localization, and inhibitor association. N-terminal RHD possesses a conserved redox-sensitive cysteine residue, C26, which has been shown to regulate phosphorylation of c-Rel and its DNA binding [11]. RHD also harbors a putative ubiquitination site between residues 118 and 171 [12].

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of c-Rel domains and posttranslational modification sites. The principal structural domains of c-Rel protein are shown, which include N-terminal Rel homology domain (RHD), nuclear localization sequence (NLS), Rel inhibitory domain (RID), and two transactivation domains (TAD). Amino acid positions of c-Rel domains and posttranslational modification sites such as ubiquitination, phosphorylation (P), and O-GlcNAcylation (O-G) complied from corresponding information for chicken, mouse, and human c-Rel are indicated in the figure. Blue dotted lines represent the position of amino acid sequence encoded by exon 9

RID (100 aminoacids, 323–422) is a region between RHD and TAD. The deletion of RID was shown to increase DNA binding and transactivation potential of c-Rel [13]. The RID region is largely unstructured and falls outside the region that has been crystallized with the DNA, aminoacids 7–281 of chicken c-Rel [14], making it hard to speculate any mechanism based on structure by which it alters c-Rel-dependent transcription. Interestingly, our previous study discovered a unique posttranslational modification of c-Rel with in the RID, at S350. We found that c-Rel was modified by the sugar N-acetylglucosamine, in a reversible process termed O-GlcNAcylation, which enhanced the DNA-binding ability of c-Rel and enhanced transactivation of selected CD28-responsive element-dependent genes [15]. Whether O-GlcNAcylation at S350, which lies within the RID, modifies the structure of the RID in a way that liberates its inhibitory function is an interesting question yet to be answered.

TAD is made of two subdomains (subdomain 1 and subdomain 2), which harbors sites for phosphorylation and ubiquitination in response to various stimuli [12, 16–18]. Though c-Rel harbors various phosphorylation sites, demonstrated largely in transient expression experiments, the physiological significance of these phosphorylation sites remains largely unknown [10]. Interestingly, most of the suggested phosphorylation sites fall within the TAD region (Fig. 1), which raises the possibility that phosphorylation might be involved in modulation of the transcriptional activity of c-Rel. Consistent to this, C-terminus of c-Rel has been shown to be phosphorylated by p66 c-Rel-TD kinase at an extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 (ERK1) consensus site (TPSMSPTDL), which is necessary for c-Rel’s transcriptional activity [17]. c-Rel has also been shown to be phosphorylated at its C-terminus by TNFR-associated factor family member-associated NF-kappaB activator (TANK)-binding kinase 1 (TBK1) and IKK epsilon (IKKε). Phosphorylation of c-Rel by TBK1 and IKKε promotes nuclear accumulation of c-Rel. IKKε phosphorylation has also been shown to cause dissociation of c-Rel from the inhibitor of kappaB (IκB) complex that hold c-Rel in the cytoplasm in the resting state [18].

Genetic evidences based on global c-Rel deficiency shows that c-Rel plays an important role in B-cell homeostasis by regulating mature B-cell function [19–21]. c-Rel function in B cells has also been suggested to be regulated by alterations of its expression level. Mice deficient in B-cell adapter for phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) (BCAP) displayed decreased c-Rel levels in B cells [22, 23]. Similarly, PU.1+/−, SpiB−/− B cells also displayed decreased expression of c-Rel [24]. Loss of miRNA-146a has been shown to increase levels of c-Rel in B cells, and reporter gene assays showed that miRNA-146a is a repressor of the c-Rel gene [25]. Thus, it is plausible that PI3K, miRNA-146a, PU.1, and SpiB may regulate B-cell functions by regulating the expression of c-Rel. Dysregulation in c-Rel expression is associated with B-cell lymphomas and autoimmunity [10]. In this review, we are attempting to summarize an update on the role of c-Rel in B-cell homeostasis (Table 1) and selected B-cell diseases (Table 2).

Table 1.

Role of c-Rel target genes in cellular process of B cells

| c-Rel target genes | Cellular process regulated | Experimental model | Functional outcome/cellular effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

E2F3a Cyclin E |

Proliferation/survival |

WT and c-Rel−/− mice c-Rel overexpression in B cells |

Cell cycle arrest at G1 phase in c-Rel-deficient B cells treated with anti-IgM Overexpression of cyclin E in c-Rel-deficient B cells restores cell cycle progression in cooperation with Bcl-xL c-Rel directly regulates E2F3a transcription, which in turn regulates transcriptional activation of cyclin E promoter |

[37] |

| Cyclin D3 | Proliferation/survival | WT and c-Rel−/− mice | Cell cycle arrest at G1 phase due to failure in induction of cyclin D3, cyclin E, incomplete phosphorylation of pRB, and poor expression of E2Fs in c-Rel-deficient B cells treated with anti-IgM | [33] |

| IRF4 | Proliferation | WT and c-Rel−/− mice |

Defective IRF4 expression and proliferation in c-Rel-deficient B cells Enforced expression of IRF4 transgene rescued proliferation defects in c-Rel-deficient B cells |

[36] |

|

BAFF-R NF-κB2 |

Cell survival | C57BL/6 mice | Increased expression of prosurvival protein BAFF-R and its downstream target NF-κB2 in T2 B cells treated with anti-IgM F(ab′)2 | [44] |

| Bcl2 | Apoptosis | WT and c-Rel/RelA double knockout fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells | Poor expression of prosurvival protein Bcl2 in immature c-Rel/RelA double knockout B cells and increased apoptosis | [35] |

| A1 | Apoptosis | WT and c-Rel−/− mice |

Low expression of A1 in c-Rel-deficient B cells compared to WT Enforced expression of A1 in c-Rel-deficient B cells rescued B cells from mitogen (anti-IgM) induced apoptosis |

[40] |

| Apoptosis | C57BL/6 mice | Increased expression of prosurvival protein A1 in T2 B cells treated with anti-IgM F (ab′)2 | [44] | |

| Bcl-xL | Apoptosis | WT, c-Rel−/−, NF-κB1−/−, and c-Rel−/− NF-κB1−/− mice |

Increased LPS-induced B-cell apoptosis in c-Rel NFKB1-deficient cells Vav-Bcl2 expression prevents LPS-mediated apoptosis in c-Rel NF-κB1 deficient cells |

[41] |

| Apoptosis | WT and c-Rel−/− mice |

Increased sensitivity of B cells from c-Rel-deficient mice to antigen receptor-mediated apoptosis with decreased expression of Bcl-xL Transgene expression of Bcl-xL rescue c-Rel-deficient B cells from antigen receptor-mediated apoptosis |

[42] | |

| Apoptosis | C57BL/6 mice | Increased expression of Bcl-xL in T2 B cells treated with anti-IgM F(ab′)2, which could contribute to increased resistance to apoptosis | [44] | |

| Immunoglobulin | Antibody production |

B cells genetically deficient in c-Rel TAD (Δ c-Rel) |

Decreased levels of germline CHγ3 and CHγ1 Absence of IgG3 and IgG1 class switching |

[70] |

| c-Rel−/− and NF-κB1−/− mice |

Reduced serum IgM levels Reduced antigen-specific IgG1 |

[34] | ||

| c-Rel−/− mice (C57BL/6) infected with Citrobacter rodentium | Decreased levels of Citrobacter rodentium specific IgG in colon and serum | [128] | ||

| c-Rel−/− with collagen-induced arthritis | Lower serum IgG levels | [106] |

Table 2.

c-Rel dysregulation in B-cell diseases

| B-cell diseases | Disease model | c-Rel status | Effect on c-Rel targets/c-Rel regulated cellular process | Phenotypic presentation | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-cell lymphomas | |||||

| B-cell lymphoma | c-Rel−/− Eμ-Myc mice, c-Rel−/− TCL1-Tg mice | No c-Rel | Decreased BTB and Bach2 expression in c-Rel−/− Eμ-Myc mice | Suppress B-cell lymphoma in both mouse models | [98] |

| Germinal center B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (GCB-DLBCL) | DLBCL patients | c-Rel nuclear expression | Correlated with decreased expression of AKT, Myc and p53 | Lack of prognostic effect | [90] |

| Activated B-cell diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (ABC-DLBCL) | DLBCL patients | c-Rel nuclear expression | – | Correlated with the poor survival in DLBCL patients with TP53 mutations | [90] |

| Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma (PMBL) | PMBL patients | c-Rel nuclear accumulation | – | May associate with PMBL progression | [91] |

| Large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) | Human LBCL cell lines | Increased c-Rel activation | Decreased CD154 gene expression | Aggravate large B-cell lymphoma | [97] |

| Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) | cHL patients | 2p16.1 (rs1432295, REL) identified as susceptibility loci | – | cHL progression | [89] |

| Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg (HRS) cells (Biopsies from cHL patients) | c-Rel nuclear accumulation | – | cHL progression | [85] | |

| HRS cells from cHL patients | REL amplification | – | cHL progression | [92] | |

| Marginal zone lymphoma (MZL) | B-cell lymphoma patient | Increase in c-REL gene expression | – | May associate with Marginal zone lymphoma | [84] |

| Autoimmune diseases | |||||

| Systemic autoimmunity |

Fas L(Δm/ Δm) c-Rel−/− mice |

No c-Rel | Decreased levels of cytokines and antinuclear autoantibodies | Reduce systemic autoimmunity | [105] |

| Inflammatory arthritis | c-Rel−/− mice with collagen-induced arthritis | No c-Rel |

Lower serum IgG levels in c-Rel−/− mice Low serum IgM levels at day 12 in c-Rel−/− mice, but no change at day 28 and 60 compared to WT mice Lower collagen-induced proliferation of inguinal lymph node T cells of c-Rel−/− mice |

Protects from collagen-induced arthritis | [106] |

| Immunodeficiency diseases | |||||

| X-HIGM syndrome patients with ectodermal dysplasia (XHM-ED) | Human patients | Defect in CD40 mediated c-Rel activation in B cells | Decreased expression of genes required for the Ig CSR (RAD50, LYL1 and DNA ligase IV) and nonhomologous recombination | Immunodeficiency | [73] |

| Combined immunodeficiency | Human patients with homozygous mutation in c-REL | Defect in c-Rel expression | Defect in B-cell activation. Defect in CD40 mediated B-cell proliferation. Defect in IL-21 secretion from B-cell in response to PHA and IL-23 | Susceptibility to opportunistic infections and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection | [121] |

| Immunodeficiency in mice infected with pathogen | c-Rel−/− mice (C57BL/6) infected with Citrobacter rodentium | No c-Rel | Decreased levels of Citrobacter rodentium specific IgG in colon and serum | No protection against Citrobacter rodentium infection | [128] |

Role of c-Rel in B-cell development

B-cell development is a highly sophisticated and regulated process, which begins in primary lymphoid organs [fetal liver (before birth) and bone marrow (after birth)] with subsequent maturation in secondary lymphoid organs (lymph nodes and spleen) [26]. In antigen-independent phase of B-cell development, progenitor B cells proliferate and undergo V-(D)-J recombination in bone marrow and further into immunocompetent naïve mature B cells. Whereas, in the antigen-dependent phase, mature B cells differentiate into either memory B cells or antibody-secreting plasma B cells upon antigen binding and co-stimulation. Many B-cell-extrinsic and intrinsic factors [26] including c-Rel [27] coordinate B-cell development and functions. Previous studies suggest that c-Rel is dispensable for the development of mature B cells from their progenitors, but it is critical for the maintenance of mature B-cell functions [20, 21]. It has been shown that c-Rel knockout mice (c-Rel−/−) develop normally with no defects in hematopoiesis and lymphocyte development, but display defects in mature B-cell activation and proliferation [19]. Subsequent studies with c-Rel knockout mice also showed no developmental defects in B-cell compartments, but displayed a significant decrease in memory and germinal center B cells (GC B) [20]. We generated c-Rel-deficient non obese diabetic (NOD) mice and found no adverse effect on the development of major hematopoietic cells including B cells [28]. These studies suggest that c-Rel plays minimal role in developmental process of B cells and it is essential for mature B-cell survival and functions (Table 1). In line with this, it has been shown that c-Rel expression remains low in B-cell precursors and it increases during later stages of B-cell development [29].

Role of c-Rel in B-cell proliferation and survival

The proliferation of B cells in response to cytokine stimuli and B-cell receptor crosslinking is an essential event for the generation of antibody-producing plasma cells and humoral immune response [30, 31]. c-Rel deficiency has been shown to reduce B-cell proliferation and survival in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), anti-IgM or CD40 [20, 32, 33]. Studies using c-Rel−/−/NF-κB1−/− double knockout mice also showed normal hematopoietic stem cell differentiation with defects in B-cell activation, proliferation/survival, and humoral immune response [34]. In cell culture, resting B cells from c-Rel−/−/NF-κB1−/− double knockout mice failed to proliferate in response to various mitogens [LPS, anti-IgM F(ab′)2, and anti-RP] due to G1 cell cycle arrest [34]. While B cells from NF-κB1−/− knockout mice displayed proliferation defects in response to LPS [34], c-Rel−/− B cells showed proliferation defects in response to multiple stimuli including LPS, anti-IgM, and anti-RP [19, 34]. Interestingly, treatment with combined mitogen stimuli overcomes this proliferation defect in c-Rel−/− B cells, indicating a plausible compensatory role of other NF-κB family members in the absence of c-Rel [34]. Similarly, mice engrafted with fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells from c-Rel−/−/RelA−/− mice displayed reduced number of mature B cells, which is attributed to survival defects caused by the decreased expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 and A1 [35].

Detailed investigation on the role of c-Rel in B-cell proliferation has shown that c-Rel is required for B-cell receptor-induced cyclin D3 and cyclin E expression as well as activation of retinoblastoma protein (pRB) and expression of E2Fs in B cells [33]. Disruption of these functions in B cells as a result of c-Rel deficiency resulted in cell cycle arrest at G1 phase [33]. Several studies attributed the G1 cell cycle arrest and proliferation defect in c-Rel−/− B cells [20, 32, 34] to the decreased expression of pro-proliferative protein—interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) [36], decreased activity of G1 cyclin-dependent kinases CDK4/CDK6, cyclin D3, and cyclin E proteins [33, 37], which are essential for the cell cycle progression. Purified splenic B cells from c-Rel deficient B cells also displayed incomplete phosphorylation of pRB and decreased expression of E2F transcription factor E2F3a, critical in regulating G1 progression and S-phase entry [33, 37]. It was also observed that only mRNA levels of CCNE1, which encodes cyclin E, but not CCND3, which encodes cyclin D3, was affected in anti-IgM-treated c-Rel−/− B cells [33]. This suggests that c-Rel regulates cyclin E at transcriptional level and cyclin D3 regulation could be at posttranslational level in B cells. Increased apoptosis due to decreased expression of an antiapoptotic protein A1 could be another reason for the proliferation defects in the c-Rel−/− B cells [21, 32]. Furthermore, c-Rel directly regulates the expression of IRF4 via binding to κB sites in its promoter region [38]. IRF4 is critical regulator of immune system, which play essential role in B-cell development and maturation [39]. IRF4 functions as repressor of interferon (IFN) induced gene expression, which is anti-proliferative, and thus critical for normal B-cell proliferation [36]. It was also reported that mitogen-induced expression of IRF4 is Rel-dependent and enforced expression of IRF4 transgene restores proliferation block in c-Rel−/− B cells [36]. Furthermore, as a demonstration of the direct role for c-Rel in B-cell survival, it has been shown that the survival defect of B cells in PU.1+/− Spi-B−/− knockout mice is rescued by expression of c-Rel cDNA. c-Rel’s promoter contains three PU.1/Spi-B-binding sites that controls c-Rel expression. PU.1+/− Spi-B−/− mice have been shown to express significantly low amounts c-Rel in B cells [24]. Thus, the current shreds of evidence suggest that c-Rel controls B-cell proliferation directly via regulating transcription of proteins involved in cell cycle progression or indirectly via regulating proteins/transcriptional factors involved in B-cell apoptosis. These reports indicate that optimal c-Rel expression is required for the mature B-cell functions. Thus, alteration in c-Rel expression in B cells could increase or decrease the proliferation of mature B cells and can associate with B-cell diseases. Increase in c-Rel expression may potentially increase mature B-cell proliferation and could lead to B-cell lymphomas and increased antibody or autoantibody production. On the other hand, decrease in c-Rel expression may potentially decrease mature B-cell proliferation and could lead to decreased antibody production and lead to immunodeficiency disorders. Thus, disease-specific pharmacological targeting of c-Rel could be useful in developing treatment strategies against B-cell disease associated with altered B-cell proliferation.

Role of c-Rel in B-cell apoptosis

In the immune system, while apoptosis is essential to eliminate auto-reactive lymphocytes, inhibition of apoptosis is required for the proper cell cycle progression in activated B cells. c-Rel deficiency has been shown to promote apoptosis in mitogen-activated B cells but not in resting mature cells, indicating its essential role in the survival of activated mature B cells [32, 40]. c-Rel-mediated upregulation of prosurvival genes such as A1, an antiapoptotic Bcl2 homolog [40], and B-cell lymphoma-extra-large (Bcl-xL) [37] were shown to be critical for the protection of activated B cells against apoptosis. Furthermore, Bcl2 transgene expression or co-expression of A1 and Bcl-xL confers protection against apoptosis in activated c-Rel−/− B cells. Interestingly, enforced expression of A1 alone failed to protect against apoptosis in activated c-Rel−/− B cells [32, 40], indicating that A1 and Bcl-xL may not serve overlapping survival function. Later, it was shown that A1 expression peaks with an initial nuclear expression of c-Rel, whereas Bcl-xL expression occurs during the second wave of c-Rel expression in activated B cells [29]. Thus, c-Rel-mediated expression of A1 and Bcl-xL may be required to inhibit apoptosis during different stages of the cell cycle. c-Rel-induced expressions of A1 and Bcl-xL were also shown to be important to antagonize the activity of pro-apoptotic protein Bim (Bcl2 homology 3-only protein) in Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR-4)-activated B cells [41]. It was shown that c-Rel and NF-κB1 were essential for the survival of LPS activated B cells, where they initiate Bim degradation via two distinct mechanisms such as upregulation of A1/Bcl-xL and Tpl2-dependent ERK phosphorylation respectively [41]. c-Rel was also shown to be required for the protection of B cells from antigen receptor-mediated, but not Fas-mediated, apoptosis [42]. c-Rel-deficient B cells, which lack expression of antiapoptotic protein Bcl-xL, were sensitive to anti-IgM, gamma irradiation, and dexamethasone-induced apoptosis. Furthermore, transgene expression of Bcl-xL rescued this c-Rel−/− survival defect. Interestingly, anti-IgM signaling rescued c-Rel-deficient B cells from CD40-sensitized Fas-mediated apoptosis (cell extrinsic death pathway), indicating the role of independent players other than c-Rel and Bcl-xL in this process [42]. Thus, it appears that c-Rel confers protection predominantly against cell intrinsic death pathway, which is mediated by mitochondrial cytochrome c release and caspase activation [43].

c-Rel was also shown to be required for the survival and differentiation of late transitional B cells (T2 B cells) against BCR induced apoptosis. Protection from apoptosis in T2 B cells by c-Rel was suggested largely due to enhanced expression of antiapoptotic genes (A1 and Bcl-xL) along with prosurvival B-cell activating factor receptor (BAFF-R) and its downstream target NF-κB2 [44]. Conversely, T1 B cells are hypersensitive to BCR crosslinking due to low expression of c-Rel, which is essential for the expression of antiapoptotic genes. This report highlights the role of differential expression of c-Rel in transitional B cells and reveals the underlying mechanism involved in resistance or sensitization of cells to apoptosis by B-cell receptor (BCR), which is essential for the positive selection and negative selection of clonotypes in the periphery.

Role of c-Rel in germinal center B-cell maintenance

Germinal centers (GC) are the sites in the peripheral lymphoid organs, where high-affinity antibody-producing memory and plasma cells form during the T-cell-mediated immune response. GC B-cell maintenance and differentiation is an important step during B-cell development, which is regulated by NF-κB members such as c-Rel, RelA, and RelB/p52 [45, 46]. c-Rel and RelB/p52 independently regulate the proper maintenance of GC reactions and RelA play role in differentiation of GC B cells into plasma cells [45, 46]. c-Rel−/−/NF-κB1−/− double knockout mice and mice lacking C-terminal TAD domain of c-Rel show impairment in GC formation in response to T-cell-dependent immunization [34, 47]. The development of conditional GC B-cell knockout mice allowed the identification of the specific roles of NF-κB members in the GC formation and its maintenance and showed the specific role of c-Rel in GC B-cell development [45, 48]. Conditional deletion of c-Rel in GC B cells results in loss of B cells, which has been linked to a role of c-Rel in maintenance of the GC B-cell reaction rather than a role in the development of GC B-cell subsets. Specifically, c-Rel has been shown to control the expression of key metabolic genes such as phosphofructokinase, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase, enzymes involved in fatty acid oxidation, and amino acid transporters, which are required to support enhanced proliferation demands in GC B cells [45]. Conditional deletion of c-Rel in GC B cells resulted in the involution of GCs, indicating its role in the maintenance of established GCs [45]. In the absence of c-Rel, it was found that GCs collapsed after the formation of dark and light zones on day 7 of GC formation [45]. Initially, it was thought that the effect of c-Rel on GC formation was mediated by Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2), a histone methyltransferase, whose expression was shown to be regulated by c-Rel in lymphocytes [49]. EZH2 was highly expressed in GC B cells and its deficiency compromised the GC formation and antibody production [50]. Contrarily, expression of EZH2 was unaltered in c-Rel−/− GC B cells [45], indicating the involvement of other players in the disruption of GC B-cell development and maintenance in the absence of c-Rel. It was also shown defects in GC B cells in c-Rel-deficient mice which were associated with dysregulation of genes involved in the metabolic reprogramming that directs the cell growth before cell division, linking c-Rel to energy metabolism in B cells [45]. Recent evidences suggest that nutrients and metabolic by-products influence the different subset of B cells and regulate immune responses [51]. Thus, more studies are required to dissect the role of c-Rel in regulation of energy metabolism in B cells and their subsets. These studies could help in designing c-Rel centric treatment strategies to treat metabolic abnormalities associated with B-cell diseases. Earlier, c-Myc, which belongs to the family of regulator genes and proto-oncogenes, was also shown to be essential for the mature germinal center maintenance [52, 53]. Ablation or inhibition of c-Myc [52, 53] shares comparable defects in GC maintenance similar that of c-Rel−/− mice [45]. Interestingly, c-Myc potentially regulates many of the genes involved in the regulation of energy metabolism in normal T cells and in Burkitt’s lymphoma B cells [54]. Whether c-Rel and c-Myc cooperate in regulating energy metabolism and germinal B-cell maintenance remains an interesting area to be explored.

Complex regulatory roles of NF-κB members in regulation of B-cell proliferation and differentiation in GC are very well appreciated [55–57]. De Silva et al. showed that plasma cells and their precursors in GC have higher expression of NF-κB2 and low expression of c-Rel [46]. In line with this, it was shown that dynamic repression of c-Rel by RelA-induced Blimp1 controls the switch from GC B-cell proliferation to antibody secreting cell (ASC) generation [8]. It was also shown that the ectopic expression of c-Rel blocks ASC differentiation by inhibiting the transcription factor Blimp1 [8]. This indicates that c-Rel and RelA do not compensate for each other; instead, they play distinct, antagonistic functions during B-cell proliferation and differentiation. Collectively, these reports signify the importance of c-Rel in GC B-cell maintenance and differentiation, which is essential for the normal immune response.

Role of c-Rel in antibody production

Antibody production is a hallmark function of B cells, which is essential for effective humoral immune response. Dysregulation of immunoglobulin (Ig) production is associated with autoimmunity [58–60] and immunodeficiency [61, 62]. The diverse array of Ig production includes highly intricate mechanisms such as V(D)J recombination, somatic hypermutation, and class switch recombination (CSR), which generates high-affinity antibodies diversifying antibody effector functions [63]. During early B-cell differentiation in the bone marrow, the V(D)J segments of Ig genes rearrange to generate a diverse repertoire of antibodies. During this process, Ig heavy chain (IgH) rearranges first, followed by Ig light chain to express a complete antigen receptor. The somatic joining of V(D)J gene segments is regulated by recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG 1 and 2) and cis-regulatory enhancer sequences that specifically alters the accessibility of recombinase machinery to the gene segments [64].

Various transcriptional factors, including NF-κB family members, regulate the production of Ig [65–69]. Initial study of c-Rel deficient mice showed impaired activation, defects in isotype class switching, and antibody production in mature B cells in response to antigenic stimuli [19]. Specifically, c-Rel was shown to be essential for efficient class switching to IgG1 and IgG2a [19]. In a similar study, B cells genetically deficient in c-Rel TAD (Δ c-Rel) were shown to display selective defects in germline CH transcription and Ig class switching [70]. Δ c-Rel B cells failed to switch to IgG3 and IgG1 with concomitant decrease in the levels of germline CHγ3 and CHγ1 [70]. In another study, combined loss of NF-κB1 and c-Rel in mice resulted in defects in humoral immunity due to reduced serum IgM levels and antigen-specific IgG1 [34]. Double deficiency of NF-κB1 and c-Rel showed lower levels of serum immunoglobulins compared to the animals with individual NF-κB subunit deficiency [34]. Furthermore, antigen-mediated IgG response was also negligible in NF-κB1 and c-Rel double deficient mice, indicating the important role of both NF-κB members in maintaining humoral immunity [34]. Similarly, serum Ig levels were undetectable in mice reconstituted with c-Rel−/−/RelA−/− mice fetal liver cells, which could be attributed to defect in B-cell terminal differentiation [35].

Emphasizing the role of NF-κB proteins, it was shown that that different B-cell activators such as T-cell-dependent antigens and LPS differentially affect IgG1 class switching by differential induction of NF-κB proteins [71]. It was shown that CD40 signaling induces germline γ1 transcription with concomitant induction of p50-RelA and p50-RelB, whereas LPS poorly induced germline γ1 transcription with induction p50-c-Rel and p50-p50 [71]. In murine B cells, c-Rel was shown to control the activity of 3′αE-hsl,2, an enhancer located 3′ to the CHα gene in the IgH locus (3αE), in response to CD40 [72]. Furthermore, c-Rel was also shown to be required for the CSR mediated by CD40 signaling [73]. B cells from X linked hyper-IgM (X-HIGM) syndrome with ectodermal dysplasia (XHM-ED) patients, characterized by defective CD40 signaling due to NF-κB essential modulator (NEMO) mutations, failed to activate c-Rel and CSR treated with CD40 and IL-4 [73]. It was also shown that XHM-ED patient B cells treated with CD40 ligand and IL-4 showed defects in expression of genes required for the CSR (RAD50, LYL1, and DNA ligase IV), nonhomologous recombination [73]. Later, it was found that c-Rel also plays a significant role in germline transcription, which is essential for CSR. Mutation in c-Rel abrogates CD40-induced enhancement of IL-4-dependent gamma 4 germline transcription, and it was shown that c-Rel selectively activates novel IL-4/CD40-responsive element in the human Ig γ4 germline promoter [74]. Similarly, c-Rel−/− B cells showed severe impairment in the germline γ1 transcript expression in response to both CD38 and CD40 ligation [75]. c-Rel was also shown to regulate Igκ gene transcription in pre-B cells [69]. Co-repression of RelA and c-Rel was shown to decrease germline Igκ transcription and rearrangement in pre-B cells without affecting RAG transcription [69]. This study showed that Igk enhancer activity was inhibited in c-Rel/RelA-arrested B cells and hypothesized that dual block in c-Rel and RelA might interfere with the expression of other factors implicated in Igκ transcription [69]. Thus, accumulating evidence suggests that c-Rel regulates different processes involved in antibody production. The varied roles of c-Rel implicated in antibody production may also influence autoantibody production and autoimmune diseases, which remains as an area to be explored in future investigations.

Role of c-Rel in B-cell diseases

c-Rel has been implicated in array of human diseases that affect both immune and non-immune compartments, which may include B cells in pathogenesis, including multiple cancers [76], fibrotic diseases [10, 77], inflammatory bowel diseases [78], and autoimmune diseases [79, 80]. Here, we will focus on selected diseases directly involving B cells (Table 2).

Role of c-Rel in B-cell lymphomas

Among the NF-κB members, c-Rel possesses a unique ability to transform avian lymphoid cells in-vitro and overexpression of mouse c-Rel and human c-Rel mutants has been shown to transform lymphoid cells in cultures [81, 82]. The role of c-Rel in B-cell lymphomas has been extensively reviewed recently [83]. Several types of B lymphomas are characterized by either c-Rel gene amplifications or c-Rel nuclear localization [84–92]. Several studies suggest that c-Rel inhibition aids to arrest the growth of various human B-cell lymphoma cell lines [93–95]. Earlier, CD154 (CD40 ligand), member of tumor necrosis factor superfamily protein, was implicated in lymphoma cell survival [96]. Later finding shed light into the mechanism of this phenomenon and showed that c-Rel activation in synergy with nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) aggravates large B-cell lymphoma (LBCL) via activating CD154 gene [97]. It is also possible that hyperactivation of c-Rel may be oncogenic considering its role in regulating metabolic genes in GC B cells [45] and may play role in GC lymphomagenesis. Glycolytic flux was found enhanced in the diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) subtype [86], and it will be interesting to know whether hyperactivation of c-Rel alters energy metabolism in B cells impacting B-cell lymphoma progression. c-Rel was also shown to exhibit tumor suppressor role in B-cell lymphoma development [98]. In a mouse B-cell lymphoma model, loss of c-Rel showed early onset of c-Myc-derived lymphoma due to significant downregulation of B-cell tumor suppressor BTB and CNC homology 2 (Bach2) [98]. Similarly, loss of c-Rel also increased lymphoma progression in T-cell lymphoma1 (TCL1) transgene-derived lymphoma [98], indicating that the tumor suppressor role of c-Rel is not limited to a particular model of lymphoma. Thus, c-Rel appears to possess both tumor promoter and suppressor function, warranting further comprehensive studies to decipher the precise mechanism involving c-Rel in the inverse regulation of B-cell lymphoma. There has been some progress in this area with recent evidences suggesting microRNAs (miRNAs) and their targets determining the tumor-promoting or suppressive functions of NF-κB in a cell and tissue-dependent manner [99]. Interestingly, miR-155 was shown to repress the expression of E3 ubiquitin ligase Peli1, which degrades c-Rel in T follicular cells [100]. Deficiency of miR-155, which results in increased Peli1 expression and decreased c-Rel expression, leads to decreased proliferation and CD40 ligand expression in T follicular cells, compromising their B helper function [100]. Peli1 has been shown to mediate K48 ubiquitination of c-Rel and prevent the nuclear accumulation of c-Rel by targeting it to the ubiquitin–proteasome-mediated degradation in T cells [101]. B cells isolated from Peli1-deficient mice show enhanced proliferation of B-cell in response to TLR2 and CD40 stimulations [102]. Whether Peli1 deficiency protects c-Rel from proteasomal degradation in B cells leading to enhanced c-Rel-dependent B-cell proliferation and the role of Peli1 in terminating c-Rel-mediated signaling in B cells remains to be investigated. Such studies will decode the interplay between c-Rel, Peli1 and miRNAs in B cells, which could prove helpful to further dissect the role of c-Rel in B-cell lymphomas.

Role of c-Rel in B cell-mediated autoimmunity

Autoimmunity is characterized by defects in deletion of auto-reactive B and T lymphocytes and autoantibody production. Fas-induced apoptosis is critical in elimination of auto-reactive lymphocytes and protection against autoimmunity. Loss-of-function mutations in Fas and FasL genes are associated with systemic autoimmune disease in humans and mice [103, 104]. Immune cells of FasLΔm/Δm mice show increased activation of NF-κB2 and c-Rel that is associated with increased inflammatory cytokines in the serum [105]. Loss of c-Rel has been shown to reduce cytokine levels and antinuclear antibodies in FasLΔm/Δm mice, ameliorating systemic autoimmunity [105]. This protective effect resulting from c-Rel loss might be attributed to both cell intrinsic role of c-Rel in B cells as well as B-cell-extrinsic role of c-Rel in helper T cells and myeloid cells, which contribute to B-cell activation [27]. Interestingly, loss of NF-κB2 reduced proinflammatory cytokines and autoantibodies, but increased lymphoproliferative disease and mortality in FasLΔm/Δm mice [105]. Similar to decreased antibody production associated with loss of c-Rel in FasLΔm/Δm, c-Rel−/− C57BL/6 mice also show lower levels of serum IgG and resistance to collagen-induced arthritis [106]. This correlation of c-Rel inhibition/absence with decreased antibody production suggests that selective targeting of c-Rel may prove beneficial in treating systemic autoimmune diseases. As described above, c-Rel regulates class switching and germline transcription involved in antibody production [69, 70, 72, 74, 75]. Whether c-Rel plays a role in regulating antibody production in various autoimmune diseases remains an interesting area of investigation. This will require comprehensive analysis of antibody production in B cells and plasma cells conditionally targeted to delete c-Rel expression, and their functional studies in autoimmune disease models.

Role of immunometabolism in immune cell function and autoimmunity is an emerging area of research [107–109]. B-cell proliferation and antibody production are energy-demanding processes for which they undergo rapid metabolic reprogramming upon activation [110, 111]. Difference in the metabolic programming was observed between anergic and autoimmune-prone B cells [110]. It was shown that anergic B cells were kept under low-energy condition, and upon LPS activation, they showed moderate increase in glycolysis and oxygen consumption. Contrarily, B cells treated with elevated concentration of BAFF showed rapid increase in the glycolysis followed by increased antibody production [110]. B-cell-specific deletion of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) was shown to decrease B-cell number and antibody production [110]. c-Rel, being a critical regulator of B-cell proliferation and antibody production, may exploit metabolic pathways to meet the high-energy demand required by these processes. Consistent with this, in GC B cells, c-Rel was shown to regulate expression of the genes that are essential for B-cell metabolism [45]. Thus, c-Rel, which is associated with several autoimmune diseases [10], may drive B-cell proliferation and antibody production during autoimmune diseases via controlling expression of the genes that regulate B-cell metabolism.

Hexosamine biosynthetic pathway (HBP), a minor arm of glucose metabolism, regulates protein functions via inducing unique posttranslational modification called O-GlcNAcylation [112]. We have shown that c-Rel is O-GlcNAcylated at serine 350 in B cells and T cells, and this occurs at about 5% in basal state, which increases to 25% in hyperglycemic conditions [15]. O-GlcNAcylation of c-Rel increases its transcriptional activity in T cells and was suggested to promote autoimmunity by increasing cytokine production [15]. We also found that c-Rel was O-GlcNAcylated in B cells [15], which may alter B-cell functions including proliferation and antibody production. Cellular O-GlcNAcylation was shown to be required for B-cell activation and antibody production [113]. Thus, it will be interesting to know how O-GlcNAcylation of c-Rel due to increased glucose flux during autoimmune diabetes will alter c-Rel function in B cells. Such a study will help to design tailored therapeutic approach targeting disease-dependent posttranslational modification, i.e., c-Rel O-GlcNAcylation, to treat autoimmune diabetes.

Role of c-Rel in B-cell immune deficiencies

Defects in the activation of c-Rel may negatively impact B-cell function and lead to immunodeficiency diseases by impeding B-cell development and antibody production. Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is an immunodeficiency disease, characterized by a defect in ROS production and B-cell proliferation [114, 115]. ROS is important for sustained B-cell receptor signaling and B-cell proliferation [116–118]. NF-κB members including c-Rel are key modulators of oxidative stress [118, 119]. c-Rel was shown to be involved in LPS/IFN gamma stimulation-induced expression of nitric oxide synthase (NOS2), a reactive nitrogen species (RNS) causing oxidative stress, in Raw 264.7 cells [119]. NOS2−/− experimental autoimmune myasthenia gravis (EAMG) mouse model displayed increased B-cell activity associated with autoimmune IgG production [120]. However, a link between c-Rel-NOS2 axes in EAMG is murky. Additional studies are necessary using conditional knockout of c-Rel in B cells to learn the cell intrinsic role of c-Rel in regulating the expression of genes controlling ROS- and RNS-mediated oxidative stress. Such a system will reveal the role of c-Rel in regulating oxidative stress-dependent signaling in B cells and its effect on B-cell proliferation and antibody production during normal physiology and immune deficiencies.

Several human immunodeficiency diseases exhibit compromised c-Rel function in B cells [73, 121]. NEMO mutations have been associated with multiple immunodeficiency conditions including incontinentia pigmenti (IP), ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency (EDA-ID) [122], and X-HIGM syndrome with ectodermal dysplasia (XHM-ED) [73]. NEMO mutations result in hypomorphic effect on NF-κB activation as in EDA-ID or amorphic effect as in IP [123]. Moreover, NEMO-deficient mice exhibit a phenotype of embryonic lethality, similar to NF-κB p65 knockout mice [124] suggesting a strong link between NEMO functions and p65 functions. NEMO has also been shown to specifically regulate c-Rel function as NEMO mutations results in dysregulation in CD40 mediated c-Rel activation in B cells and B-cell terminal differentiation in XHM-ED [73]. Interestingly, TNF and TLR-mediated NF-κB activation is preserved in B cells of XHM-ED patients with a missense mutation in NEMO, indicating that the mutation affects only CD40 signaling in B cells [125]. B cells isolated from XHM-ED patients failed to activate c-Rel and p65 following CD40 ligand stimulation. Costimulation with CD40 ligand and IL-4 failed to restore c-Rel activity, but restored p65 activity in patient B cells, suggesting that NEMO dependency varies among NF-κB members in B cells [73]. Moreover, microarray analysis of XHM-ED patient’s B cells stimulated with CD40 ligand and IL-4 showed defects in the expression of several genes required for the Ig CSR (RAD50, LYL1, and DNA ligase IV) and nonhomologous recombination with no defect in AID [73]. This suggests that normal AID expression alone is insufficient for efficient CSR and SHM, which might depend on the expression of several other putative c-Rel target genes [73]. Although the microarray analysis has identified several genes that are modulated in XHM-ED patients, further molecular mechanistic studies are needed to examine the direct regulation of these genes by c-Rel.

Emphasizing the crucial role of c-Rel in immunodeficiency, a recent clinical study reported combined immunodeficiency in a patient with c-Rel deficiency [121]. This seminal report showed that a homozygous mutation abolished c-Rel expression that impaired T- and B-cell activation, susceptibility to opportunistic infections and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection [121]. c-Rel-deficient patient’s B-cell failed to proliferate after anti-CD40 stimulation indicating the critical role of c-Rel in B-cell proliferation. In vitro stimulation of patient’s B-cell with phytohemagglutinin (PHA) and IL-23 showed defective IL-21 production compared to healthy subjects. IL-21 is required for the development of germinal B cells, isotype switching, and antibody response to T-cell-dependent antigens [121]. This human patient report, which mirrors the immunological defects in c-Rel-deficient mice [19, 126, 127], highlights the contribution of c-Rel to host immunity in mammals. Further corroborating the role of c-Rel in host immune response in mammals, a recent study showed that c-Rel-deficient mice infected with Citrobacter rodentium failed to elicit antibody response against the pathogen [128].

Conclusion and future perspectives

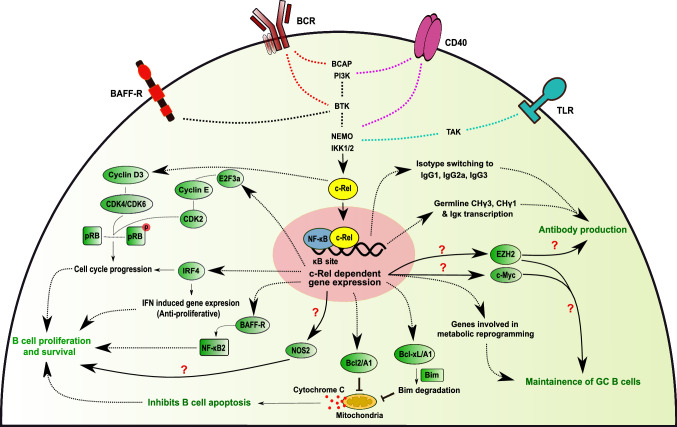

c-Rel regulates the expression of several genes (Table 1, Fig. 2), which play critical roles in B-cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell survival, germinal center formation, and antibody production. Although the role of c-Rel in B cells is endorsed by a substantial number of publications, there is a large gap in the knowledge on how c-Rel is regulated in physiological and pathological conditions by various posttranslational modifications. Studies on the regulation of c-Rel function by various metabolic sensors in B cells are emerging with great scopes of future research in the area of immunometabolism. Mechanisms modulating c-Rel expression such as transcriptional and epigenetic controls and specific roles of c-Rel-associated transcriptional complexes in B-cell-mediated autoimmunity, B-cell lymphomas, B cell-associated immunodeficiency, and non-autoimmune B-cell inflammatory disease need more comprehensive studies. A comparative study of c-Rel expression and c-Rel-dependent gene expression simultaneously in multiple B-cell disease models, preferably at single-cell level, holds great potential to reveal precise functional role of c-Rel in B-cell biology and pathology. Coupling CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing to knockdown c-Rel expression in patient-derived B cells along with the next-generation sequencing technologies will decipher disease-associated c-Rel-dependent transcriptome in B cells yielding big data for further studies. Considering its role in autoimmunity and lymphoma progression, specific inhibition of c-Rel seems to offer a potential therapeutic approach. However, the probable counterintuitive risks associated with pharmacological targeting of a key regulator of immune functions such as c-Rel need to be considered with prudence.

Fig. 2.

Signaling pathways and cellular processes regulated by c-Rel in B cells. Upon activation of BCR, CD40, TLR, and BAFF-R by their by cognate ligands, c-Rel/NF-κB complexes translocate into the nucleus, bind κB sites in the DNA, and control the expression of various genes. Alterations in the gene expression, in turn, regulate an array of cellular processes in B cells, as shown in the figure. Abbreviations used in the figure are as follows: BCR B-cell receptor, TLR Toll-like receptor, BAFF-R B-cell activating factor receptor, E2F3a E2F transcriptional factor 3a, CDK cyclin-dependent Kinase, pRB retinoblastoma protein, IRF4 Interferon regulatory factor 4, NF-κB2 Nuclear Factor kappaB 2, NOS2 nitric oxide synthase, Bcl2 B-cell CLL/Lymphoma 2 antiapoptotic protein, Bim Bcl2 homology 3-only protein, Bcl-xL B-cell lymphoma-extra-large, EZH2 Enhancer of zeste homolog 2. Question mark (?) indicates that the role of indicated gene/protein in c-Rel-mediated regulation of cellular process in B-cell is not yet certain

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Health, NIH/NIAID grants R21AI144264 and R01AI116730 to P.R.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sen R, Baltimore D. Inducibility of kappa immunoglobulin enhancer-binding protein Nf-kappa B by a posttranslational mechanism. Cell. 1986;47:921–928. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90807-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pomerantz JL, Baltimore D. Two pathways to NF-kappaB. Mol Cell. 2002;10:693–695. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00697-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramakrishnan P, Wang W, Wallach D. Receptor-specific signaling for both the alternative and the canonical NF-kappaB activation pathways by NF-kappaB-inducing kinase. Immunity. 2004;21:477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oeckinghaus A, Ghosh S. The NF-κB family of transcription factors and its regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000034. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilmore TD. Malignant transformation by mutant Rel proteins. Trends Genet. 1991;7:318–322. doi: 10.1016/0168-9525(91)90421-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doerre S, Sista P, Sun SC, et al. The c-rel protooncogene product represses NF-kappa B p65-mediated transcriptional activation of the long terminal repeat of type 1 human immunodeficiency virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:1023–1027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sohur US, Dixit MN, Chen C-L, et al. Rel/NF-κB represses bcl-2 transcription in pro-B lymphocytes. Gene Expr. 1999;8:219–229. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy K, Mitchell S, Liu Y, et al. A Regulatory circuit controlling the dynamics of NFκB cRel transitions B cells from proliferation to plasma cell differentiation. Immunity. 2019;50:616–628.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jesús TJ, Centore JT, Ramakrishnan P. Differential regulation of basal expression of inflammatory genes by NF-κB family subunits. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019;16:720–723. doi: 10.1038/s41423-019-0242-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fullard N, Wilson CL, Oakley F. Roles of c-Rel signalling in inflammation and disease. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:851–860. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glineur C, Davioud-Charvet E, Vandenbunder B. The conserved redox-sensitive cysteine residue of the DNA-binding region in the c-Rel protein is involved in the regulation of the phosphorylation of the protein. Biochem J. 2000;352:583–591. doi: 10.1042/bj3520583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen E, Hrdlickova R, Nehyba J, et al. Degradation of proto-oncoprotein c-Rel by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:35201–35207. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.35201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leeman JR, Weniger MA, Barth TF, Gilmore TD. Deletion analysis and alternative splicing define a transactivation inhibitory domain in human oncoprotein REL. Oncogene. 2008;27:6770–6781. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang DB, Chen YQ, Ruetsche M, et al. X-ray crystal structure of proto-oncogene product c-Rel bound to the CD28 response element of IL-2. Structure. 2001;9:669–678. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramakrishnan P, Clark PM, Mason DE, et al. Activation of the transcriptional function of the NF-κB protein c-Rel by O-GlcNAc glycosylation. Sci Signal. 2013;6:ra75. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin AG, Fresno M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha activation of NF-kappa B requires the phosphorylation of Ser-471 in the transactivation domain of c-Rel. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:24383–24391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M909396199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fognani C, Rondi R, Romano A, Blasi F. cRel-TD kinase: a serine/threonine kinase binding in vivo and in vitro c-Rel and phosphorylating its transactivation domain. Oncogene. 2000;19:2224–2232. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris J, Olière S, Sharma S, et al. Nuclear accumulation of cRel following C-terminal phosphorylation by TBK1/IKK epsilon. J Immunol. 2006;177:2527–2535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Köntgen F, Grumont RJ, Strasser A, et al. Mice lacking the c-rel proto-oncogene exhibit defects in lymphocyte proliferation, humoral immunity, and interleukin-2 expression. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1965–1977. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.16.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tumang JR, Owyang A, Andjelic S, et al. c-Rel is essential for B lymphocyte survival and cell cycle progression. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4299–4312. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4299::AID-IMMU4299>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerondakis S, Grossmann M, Nakamura Y, et al. Genetic approaches in mice to understand Rel/NF-kappaB and IkappaB function: transgenics and knockouts. Oncogene. 1999;18:6888–6895. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamazaki T, Kurosaki T. Contribution of BCAP to maintenance of mature B cells through c-Rel. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:780–786. doi: 10.1038/ni949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Matsuda S, Mikami Y, Ohtani M, et al. Critical role of class IA PI3K for c-Rel expression in B lymphocytes. Blood. 2009;113:1037–1044. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-163725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu CJ, Rao S, Ramirez-Bergeron DL, et al. PU.1/Spi-B regulation of c-rel is essential for mature B-cell survival. Immunity. 2001;15:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho S, Lee H-M, Yu I-S, et al. Differential cell-intrinsic regulations of germinal center B and T cells by miR-146a and miR-146b. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2757. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05196-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-cell biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gilmore TD, Gerondakis S. The c-Rel transcription factor in development and disease. Genes Cancer. 2011;2:695–711. doi: 10.1177/1947601911421925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramakrishnan P, Yui MA, Tomalka JA, et al. Deficiency of nuclear factor-κB c-Rel accelerates the development of autoimmune diabetes in NOD mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:2367–2379. doi: 10.2337/db15-1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grumont RJ, Gerondakis S. The subunit composition of NF-kappa B complexes changes during B-cell development. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5:1321–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vazquez MI, Catalan-Dibene J, Zlotnik A. B cells responses and cytokine production are regulated by their immune microenvironment. Cytokine. 2015;74:318–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yam-Puc JC, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Toellner K-M. Role of B-cell receptors for B-cell development and antigen-induced differentiation. F1000Res. 2018;7:429. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.13567.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grumont RJ, Rourke IJ, O’Reilly LA, et al. B lymphocytes differentially use the Rel and nuclear factor kappaB1 (NF-kappaB1) transcription factors to regulate cell cycle progression and apoptosis in quiescent and mitogen-activated cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:663–674. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsia CY, Cheng S, Owyang AM, et al. c-Rel regulation of the cell cycle in primary mouse B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 2002;14:905–916. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pohl T, Gugasyan R, Grumont RJ, et al. The combined absence of NF-kappa B1 and c-Rel reveals that overlapping roles for these transcription factors in the B-cell lineage are restricted to the activation and function of mature cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:4514–4519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072071599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossmann M, O’Reilly LA, Gugasyan R, et al. The anti-apoptotic activities of Rel and RelA required during B-cell maturation involve the regulation of Bcl-2 expression. EMBO J. 2000;19:6351–6360. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grumont RJ, Gerondakis S. Rel induces interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF-4) expression in lymphocytes: modulation of interferon-regulated gene expression by rel/nuclear factor kappaB. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1281–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng S, Hsia CY, Leone G, Liou H-C. Cyclin E and Bcl-xL cooperatively induce cell cycle progression in c-Rel−/− B cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:8472–8486. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gugasyan R, Grumont R, Grossmann M, et al. Rel/NF-kappaB transcription factors: key mediators of B-cell activation. Immunol Rev. 2000;176:134–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065X.2000.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shukla V, Lu R. IRF4 and IRF8: governing the virtues of B lymphocytes. Front Biol (Beijing) 2014;9:269–282. doi: 10.1007/s11515-014-1318-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grumont RJ, Rourke IJ, Gerondakis S. Rel-dependent induction of A1 transcription is required to protect B cells from antigen receptor ligation-induced apoptosis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:400–411. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.4.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Banerjee A, Grumont R, Gugasyan R, et al. NF-κB1 and c-Rel cooperate to promote the survival of TLR4-activated B cells by neutralizing Bim via distinct mechanisms. Blood. 2008;112:5063–5073. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Owyang AM, Tumang JR, Schram BR, et al. c-Rel is required for the protection of B cells from antigen receptor-mediated, but not Fas-mediated, apoptosis. J Immunol. 2001;167:4948–4956. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shawgo ME, Shelton SN, Robertson JD. Caspase-mediated Bak activation and cytochrome c release during intrinsic apoptotic cell death in jurkat cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35532–35538. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807656200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Castro I, Wright JA, Damdinsuren B, et al. B-cell receptor-mediated sustained c-Rel activation facilitates late transitional B-cell survival through control of B-cell activating factor receptor and NF-κB2. J Immunol. 2009;182:7729–7737. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heise N, De Silva NS, Silva K, et al. Germinal center B-cell maintenance and differentiation are controlled by distinct NF-κB transcription factor subunits. J Exp Med. 2014;211:2103–2118. doi: 10.1084/jem.20132613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Silva NS, Anderson MM, Carette A, et al. Transcription factors of the alternative NF-κB pathway are required for germinal center B-cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:9063–9068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602728113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carrasco D, Cheng J, Lewin A, et al. Multiple hemopoietic defects and lymphoid hyperplasia in mice lacking the transcriptional activation domain of the c-Rel protein. J Exp Med. 1998;187:973–984. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Casola S, Cattoretti G, Uyttersprot N, et al. Tracking germinal center B cells expressing germ-line immunoglobulin gamma1 transcripts by conditional gene targeting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7396–7401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602353103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neo WH, Lim JF, Grumont R, et al. c-Rel regulates Ezh2 expression in activated lymphocytes and malignant lymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:31693–31707. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.574517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Caganova M, Carrisi C, Varano G, et al. Germinal center dysregulation by histone methyltransferase EZH2 promotes lymphomagenesis. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:5009–5022. doi: 10.1172/JCI70626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Boothby M, Rickert RC. Metabolic regulation of the immune humoral response. Immunity. 2017;46:743–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Calado DP, Sasaki Y, Godinho SA, et al. The cell-cycle regulator c-Myc is essential for the formation and maintenance of germinal centers. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1092–1100. doi: 10.1038/ni.2418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dominguez-Sola D, Victora GD, Ying CY, et al. The proto-oncogene MYC is required for selection in the germinal center and cyclic reentry. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ni.2428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dang CV. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1–11. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gerondakis S, Siebenlist U. Roles of the NF-κB pathway in lymphocyte development and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000182. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Klein U, Heise N. Unexpected functions of NFκB during germinal center B-cell development: implications for lymphomagenesis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:379–387. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kennedy R, Klein U. Aberrant activation of NF-κB signalling in aggressive lymphoid malignancies. Cells. 2018;7:189. doi: 10.3390/cells7110189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Taplin CE, Barker JM. Autoantibodies in type 1 diabetes. Autoimmunity. 2008;41:11–18. doi: 10.1080/08916930701619169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maurer M, Altrichter S, Schmetzer O, et al. Immunoglobulin E-mediated autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2018;9:689. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.00689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huijbers MG, Plomp JJ, van der Maarel SM, Verschuuren JJ. IgG4-mediated autoimmune diseases: a niche of antibody-mediated disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1413:92–103. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ballow M. Primary immunodeficiency disorders: antibody deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:581–591. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.122466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fried AJ, Bonilla FA. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of primary antibody deficiencies and infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:396–414. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kenter AL. Class-switch recombination: after the dawn of AID. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15:190–198. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(03)00018-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sleckman BP, Gorman JR, Alt FW. Accessibility control of antigen-receptor variable-region gene assembly: role of cis-acting elements. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:459–481. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Reimold AM, Iwakoshi NN, Manis J, et al. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 2001;412:300–307. doi: 10.1038/35085509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shapiro-Shelef M, Lin K-I, McHeyzer-Williams LJ, et al. Blimp-1 is required for the formation of immunoglobulin secreting plasma cells and pre-plasma memory B cells. Immunity. 2003;19:607–620. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00267-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rajaiya J, Nixon JC, Ayers N, et al. Induction of immunoglobulin heavy-chain transcription through the transcription factor bright requires TFII-I. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:4758–4768. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02009-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Guo M, Price MJ, Patterson DG, et al. EZH2 represses the B-cell transcriptional program and regulates antibody-secreting cell metabolism and antibody production. J Immunol. 2018;200:1039–1052. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scherer DC, Brockman JA, Bendall HH, et al. Corepression of RelA and c-rel inhibits immunoglobulin kappa gene transcription and rearrangement in precursor B lymphocytes. Immunity. 1996;5:563–574. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80271-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zelazowski P, Carrasco D, Rosas FR, et al. B cells genetically deficient in the c-Rel transactivation domain have selective defects in germline CH transcription and Ig class switching. J Immunol. 1997;159:3133–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lin SC, Wortis HH, Stavnezer J. The ability of CD40L, but not lipopolysaccharide, to initiate immunoglobulin switching to immunoglobulin G1 is explained by differential induction of NF-kappaB/Rel proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:5523–5532. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.5523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zelazowski P, Shen Y, Snapper CM. NF-kappaB/p50 and NF-kappaB/c-Rel differentially regulate the activity of the 3’alphaE-hsl,2 enhancer in normal murine B cells in an activation-dependent manner. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1167–1172. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.8.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jain A, Ma CA, Lopez-Granados E, et al. Specific NEMO mutations impair CD40-mediated c-Rel activation and B-cell terminal differentiation. J Clin Investig. 2004;114:1593–1602. doi: 10.1172/JCI21345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Agresti A, Vercelli D. c-Rel is a selective activator of a novel IL-4/CD40 responsive element in the human Ig gamma4 germline promoter. Mol Immunol. 2002;38:849–859. doi: 10.1016/S0161-5890(01)00121-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kaku H, Horikawa K, Obata Y, et al. NF-kappaB is required for CD38-mediated induction of C(gamma)1 germline transcripts in murine B lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 2002;14:1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hunter JE, Leslie J, Perkins ND. c-Rel and its many roles in cancer: an old story with new twists. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:1–6. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gaspar-Pereira S, Fullard N, Townsend PA, et al. The NF-κB subunit c-Rel stimulates cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:929–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang Y, Rickman BH, Poutahidis T, et al. c-Rel is essential for the development of innate and T cell-induced colitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:8118–8125. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.8118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Eyre S, Hinks A, Flynn E, et al. Confirmation of association of the REL locus with rheumatoid arthritis susceptibility in the UK population. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1572–1573. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.122887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Varadé J, Palomino-Morales R, Ortego-Centeno N, et al. Analysis of the REL polymorphism rs13031237 in autoimmune diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:711–712. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gilmore TD, Cormier C, Jean-Jacques J, Gapuzan ME. Malignant transformation of primary chicken spleen cells by human transcription factor c-Rel. Oncogene. 2001;20:7098–7103. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chin M, Herscovitch M, Zhang N, et al. Overexpression of an activated REL mutant enhances the transformed state of the human B-lymphoma BJAB-cell line and alters its gene expression profile. Oncogene. 2009;28:2100–2111. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kober-Hasslacher M, Schmidt-Supprian M. The unsolved puzzle of c-Rel in B-cell lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:941. doi: 10.3390/cancers11070941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Barth TF, Bentz M, Leithäuser F, et al. Molecular-cytogenetic comparison of mucosa-associated marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and large B-cell lymphoma arising in the gastro-intestinal tract. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;31:316–325. doi: 10.1002/gcc.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barth TFE, Martin-Subero JI, Joos S, et al. Gains of 2p involving the REL locus correlate with nuclear c-Rel protein accumulation in neoplastic cells of classical Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2003;101:3681–3686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Monti S, Savage KJ, Kutok JL, et al. Molecular profiling of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma identifies robust subtypes including one characterized by host inflammatory response. Blood. 2005;105:1851–1861. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lenz G, Wright GW, Emre NCT, et al. Molecular subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma arise by distinct genetic pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:13520–13525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804295105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Curry CV, Ewton AA, Olsen RJ, et al. Prognostic impact of C-REL expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Hematop. 2009;2:20–26. doi: 10.1007/s12308-009-0021-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Enciso-Mora V, Broderick P, Ma Y, et al. A genome-wide association study of Hodgkin’s lymphoma identifies new susceptibility loci at 2p16.1 (REL), 8q24.21 and 10p14 (GATA3) Nat Genet. 2010;42:1126–1130. doi: 10.1038/ng.696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Li L, Xu-Monette ZY, Ok CY, et al. Prognostic impact of c-Rel nuclear expression and REL amplification and crosstalk between c-Rel and the p53 pathway in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:23157–23180. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weniger MA, Gesk S, Ehrlich S, et al. Gains of REL in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma coincide with nuclear accumulation of REL protein. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2007;46:406–415. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Joos S, Menz CK, Wrobel G, et al. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma is characterized by recurrent copy number gains of the short arm of chromosome 2. Blood. 2002;99:1381–1387. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kalaitzidis D, Davis RE, Rosenwald A, et al. The human B-cell lymphoma cell line RC-K8 has multiple genetic alterations that dysregulate the Rel/NF-kappaB signal transduction pathway. Oncogene. 2002;21:8759–8768. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liang M-C, Bardhan S, Porco JA, Gilmore TD. The synthetic epoxyquinoids jesterone dimer and epoxyquinone A monomer induce apoptosis and inhibit REL (human c-Rel) DNA binding in an IκBα-deficient diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cell line. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tian W, Liou H-C. RNAi-mediated c-Rel silencing leads to apoptosis of B-cell tumor cells and suppresses antigenic immune response in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e5028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clodi K, Asgary Z, Zhao S, et al. Coexpression of CD40 and CD40 ligand in B-cell lymphoma cells. Br J Haematol. 1998;103:270–275. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1998.01031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pham LV, Tamayo AT, Yoshimura LC, et al. Constitutive NF-kappaB and NFAT activation in aggressive B-cell lymphomas synergistically activates the CD154 gene and maintains lymphoma cell survival. Blood. 2005;106:3940–3947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hunter JE, Butterworth JA, Zhao B, et al. The NF-κB subunit c-Rel regulates Bach2 tumour suppressor expression in B-cell lymphoma. Oncogene. 2016;35:3476–3484. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Markopoulos GS, Roupakia E, Tokamani M, et al. Roles of NF-κB signaling in the regulation of miRNAs impacting on inflammation in cancer. Biomedicines. 2018;6:40. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines6020040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liu W-H, Kang SG, Huang Z, et al. A miR-155-Peli1-c-Rel pathway controls the generation and function of T follicular helper cells. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1901–1919. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chang M, Jin W, Chang J-H, et al. The ubiquitin ligase Peli1 negatively regulates T cell activation and prevents autoimmunity. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1002–1009. doi: 10.1038/ni.2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Chang M, Jin W, Sun S-C. Peli1 facilitates TRIF-dependent Toll-like receptor signaling and proinflammatory cytokine production. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1089–1095. doi: 10.1038/ni.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Watanabe-Fukunaga R, Brannan CI, Copeland NG, et al. Lymphoproliferation disorder in mice explained by defects in Fas antigen that mediates apoptosis. Nature. 1992;356:314–317. doi: 10.1038/356314a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fisher GH, Rosenberg FJ, Straus SE, et al. Dominant interfering Fas gene mutations impair apoptosis in a human autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Cell. 1995;81:935–946. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O’Reilly LA, Hughes P, Lin A, et al. Loss of c-REL but not NF-κB2 prevents autoimmune disease driven by FasL mutation. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:767–778. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2014.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Campbell IK, Gerondakis S, O’Donnell K, Wicks IP. Distinct roles for the NF-kappaB1 (p50) and c-Rel transcription factors in inflammatory arthritis. J Clin Investig. 2000;105:1799–1806. doi: 10.1172/JCI8298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Stathopoulou C, Nikoleri D, Bertsias G. Immunometabolism: an overview and therapeutic prospects in autoimmune diseases. Immunotherapy. 2019;11:813–829. doi: 10.2217/imt-2019-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Teng X, Li W, Cornaby C, Morel L. Immune cell metabolism in autoimmunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2019;197:181–192. doi: 10.1111/cei.13277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Colamatteo A, Micillo T, Bruzzaniti S, et al. Metabolism and autoimmune responses: the microRNA connection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1969. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Caro-Maldonado A, Wang R, Nichols AG, et al. Metabolic reprogramming is required for antibody production that is suppressed in anergic but exaggerated in chronically BAFF-exposed B cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:3626–3636. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Waters LR, Ahsan FM, Wolf DM, et al. Initial B-cell activation induces metabolic reprogramming and mitochondrial remodeling. iScience. 2018;5:99–109. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.de Jesus T, Shukla S, Ramakrishnan P. Too sweet to resist: control of immune cell function by O-GlcNAcylation. Cell Immunol. 2018;333:85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu J-L, Chiang M-F, Hsu P-H, et al. O-GlcNAcylation is required for B-cell homeostasis and antibody responses. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1854. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01677-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cotugno N, Finocchi A, Cagigi A, et al. Defective B-cell proliferation and maintenance of long-term memory in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:753–761.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pozo-Beltrán CF, Suárez-Gutiérrez MA, Yamazaki-Nakashimada MA, et al. B subset cells in patients with chronic granulomatous disease in a Mexican population. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2019;47:372–377. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Feng Y-Y, Tang M, Suzuki M, et al. Essential role of NADPH oxidase-dependent production of reactive oxygen species in maintenance of sustained B-cell receptor signaling and B-cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2019;202:2546–2557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wheeler ML, Defranco AL. Prolonged production of reactive oxygen species in response to B-cell receptor stimulation promotes B-cell activation and proliferation. J Immunol. 2012;189:4405–4416. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Morgan MJ, Liu Z. Crosstalk of reactive oxygen species and NF-κB signaling. Cell Res. 2011;21:103–115. doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Cieslik KA, Deng W-G, Wu KK. Essential role of C-Rel in nitric-oxide synthase-2 transcriptional activation: time-dependent control by salicylate. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:2004–2014. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.026054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shi FD, Flodström M, Kim SH, et al. Control of the autoimmune response by type 2 nitric oxide synthase. J Immunol. 2001;167:3000–3006. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Beaussant-Cohen S, Jaber F, Massaad MJ, et al. Combined immunodeficiency in a patient with c-Rel deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144:606–608.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]