Abstract

Selectively targeting the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of cancer cells, though promising a new strategy for cancer therapy, remains underdeveloped. Enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA) is emerging as a promising approach for selectively targeting ER of cancer cells. This work reports an easily accessible branched peptide that consists a D-tetrapeptide backbone and a branch with the sequence of KYDKKKKDG, being an EISA substrate of typsin-1 (PRSS1), selectively inhibits cancer cells. Depending on the type of cells, the level of PRSS1 expression dictates the cytotoxicity of the branched peptide. Moreover, immunostaining and fluorescent imaging reveals that PRSS1 overexpresses on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of a high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell line (OVSAHO). The overexpression of PRSS1 renders the branched peptide to exhibit high selectivity against OVSAHO by the in situ formation of the peptide assemblies on the ER of OVSAHO cells, which causes ER stress and eventual cell death. This work, illustrating trypsin-guided EISA for inhibiting cancer cells by enzymatic reaction on ER for the first time, offers a new way to target the subcellular organelles of cancer cells for potential cancer therapy.

Keywords: enzyme, trypsin, peptides, self-assembly, cancer

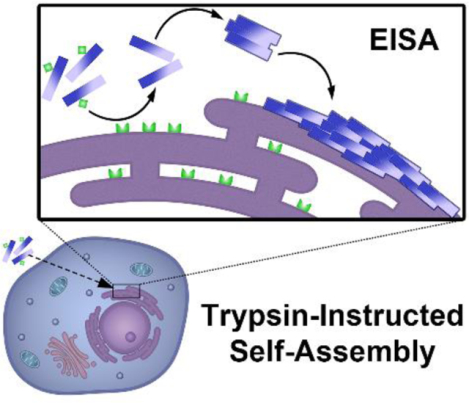

Graphical Abstract

Trypsin-instructed self-assembly, developed in this work, provides a novel strategy to subcellular organelle targeting of cancer cells. The trypsin-1, overexpressed on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of OVSAHO cell, allows to in situ enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA) of the peptides on ER, resulting in the selectively inhibition of OVSAHO cell.

Cancer remains a major burden to public health. Despite the considerable progresses in chemotherapy and molecular therapy, cancer therapy has still faced considerable challenges, especially cancer selectivity. Low cancer selectivity in cancer therapeutics leads to not only the increase in treatment-related toxicity which causes deleterious side effects on adjacent normal cells, also the decrease in efficacy of treatment.[1] Although prodrug, a pharmacologically inactive molecule being converted into the active drugs in vivo, has been developed to improve the selectivity of drugs for target cancer cell, the issue of drug resistance still remains in cancer therapy.[2] Recently, enzyme-instructed self-assembly (EISA), a process that integrates enzymatic reaction and molecular self-assembly, is emerging as a new approach that are receiving active exploration for cancer therapy.[3] Relying on the activity of the enzyme overexpressed in cancer cell, EISA is able to selectively inhibit the growth of cancer cells.[4] Moreover, the supramolecular assemblies formed by EISA reduce the acquired drug resistance in inhibiting cancer cells.[5] In contrast with individual drug molecules, which easily lost their efficacies due to efflux pump, the assemblies resulted from EISA hardly diffuse out from the targeted cancer cells. An increasing number of labs, accordingly, have developed EISA of the supramolecular assemblies of small molecules for inhibiting cancer cells[6] or for cancer theranostics.[7]

On the other hand, dysfunction of organelle has emerged as a novel strategy in developing effective cancer therapy, because the organelle plays multiple essential roles in metabolism.[8] Targeting the organelles, such as nucleus,[9] mitochondria,[10] lysosome,[11] and endoplasmic reticulum (ER),[12] allows to concentrate drugs at target subcellular compartment in which the drug acts, and consequently, disrupts the function of the organelle, providing the improved efficacy as well as the reduced risk of side effects.[13] For this reason, subcellular EISA for cancer therapy also promises high therapeutic efficacy by accumulating the assemblies in subcellular organelles.[5a, 14] ER, besides as the principal intracellular organelle responsible for metabolic processes, including gluconeogenesis, lipid synthesis, and the biogenesis of autophagosomes and peroxisomes,[15] also takes charge of the synthesis, folding, and posttranslational modifications of proteins destined for the secretory pathway, amount to almost 30% of the total proteome.[16] Accordingly, ER have been considered as the attractive target organelle in cancer therapy, leading to the development of functional groups that guide the peptide assemblies to disrupt ER.[17] However, the selectivity of EISA of peptides containing ER-guiding functional groups remains to be improved. For example, the assemblies of the L-homoarginine-conjugated peptides, which interact with lipid membrane, disrupt plasma membrane as well as ER membrane, leading to moderate cancer selectivity at the high-effective concentration.[17a] Moreover, most of EISA approaches still center on a limited number of enzymes, such as alkaline phosphatases,[4b] carboxylesterases,[4a] furin,[18] and cathepsins.[19] Therefore, it is necessary to develop a novel EISA strategy based on new enzymes for ER targeting to ensure high selectivity.

In this work, we developed EISA strategy using trypsin-1 (PRSS1) to target the ER of cancer cell with exceptional cancer selectivity. Our studies show that the peptide assemblies of 2, formed by trypsin-1 catalyzed proteolysis of a branched peptide (1), mainly accumulate at the ER of the cells of a high-grade serous ovarian cancer cell line (OVSAHO), resulting in the inhibition of OVSAHO cancer cell. Compared with OVSAHO cells, the normal ovarian epithelial cells (HOSE636), which express low level of PRSS1, show high viability after treatment of 1. Further characterization indicates that PRSS1 locates on the ER of OVSAHO, suggesting that trypsin-instructed self-assembly occurs in situ on the ER of OVSAHO (Figure 1). As the first case of in situ EISA on ER, this work demonstrates a new strategy to inhibit target cancer cells with high selectivity and expands the scope of enzymes for developing a new strategy of EISA for inhibiting cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Illustration trypsin-instructed self-assembly on ER for inducing anticancer activity and the molecular structures of the substrate (1) of trypsin-1 and the products (2, 3) of trypsin-1 catalyzed proteolysis.

We originally synthesized 1 as a control of a branched peptide that consists of the FLAG-tag (DYKDDDDK) as the branch.[14a] 1 consists of D-peptide backbone (Nap-ffky) and L-peptide branch (KYDKKKKDG), which is a charge reversed sequence of the FLAG-tag. After synthesizing 1 via Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS) (Scheme S1), we unexpectedly found that, enterokinase (ENTK), the enzyme specifically catalyzing the cleavage of FLAG-tag, is able to cleave 1 (Figure S1a), albeit slowly. This observation leads us to realize that 1 is able to act as the substrate of trypsin-1, because trypsin-1 preferentially cleaves the lysine (K)-enriched substrate. Indeed, the time-dependent chemical composition analysis of the solution of 1 in the presence of trypsin-1 confirms the cleavage reaction (Figure S1b). Because, PRSS1, being overexpressed in various cancer cells to promote the tumor growth, has been reported as a tumor marker.[20] Thus, we decided to further examine EISA of 1 catalyzed by PRSS1 and to evaluate the inhibitory activity of 1 against cancer cells.

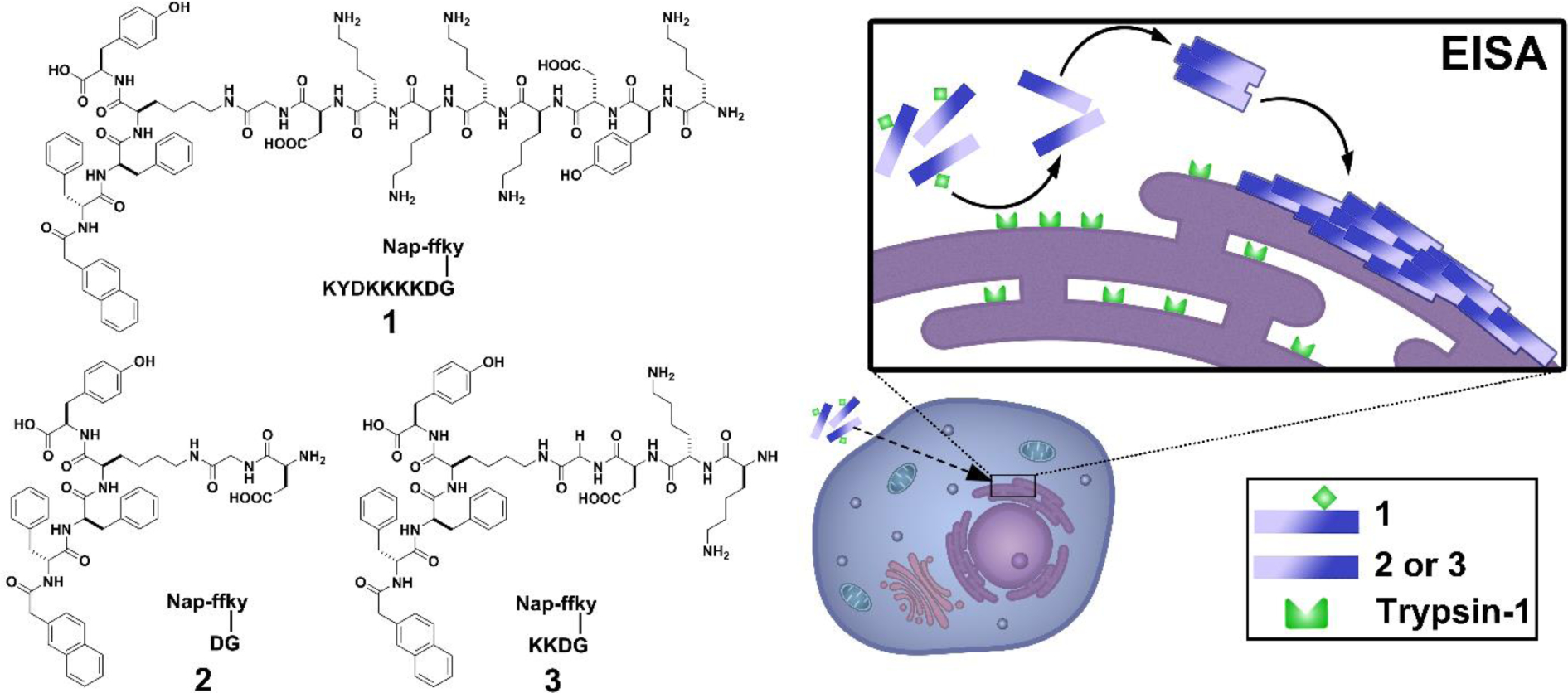

To confirm that 1 is a proper substrate of trypsin-1 for EISA, we incubated 1 (200 μM) with trypsin-1. After the 24-h incubation, liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC-MS) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) reveal the chemical composition (Figure S2) and the morphology of the peptide assemblies (Figure 2a), respectively. The peptide assemblies, resulted from EISA of 1 with trypsin-1, consist of 2 and 3 in 16:9 ratio, implying that 2 and 3 are sufficiently hydrophobic to be involved in the formation of the peptide assemblies. Although the reason of the absence of KDG and KKKDG in the hydrolysis products remains to be elucidated, it is possible that the D-peptide backbone blocks the conformations of the branched peptides needed for those specific proteolytic cleavage. In addition, the assemblies form bundles, in which the uniform nanofibers (8±1 nm in width) align, with several micrometers in length. Without the addition of trypsin-1, 1 self-assembles to form the micelles with diameters about 15±2 nm. The critical micelle concentration (CMC) of 1 is 194 μM (Figure S4). It is likely that the hydrophilic branch in 1 enables 1 to form micelles. After removing the most of the hydrophilic branch, the resulting molecule, 2, becomes more hydrophobic and provides more aromatic-aromatic interactions. Thus, 2 self-assembles into β-sheet. The morphology of the assemblies of 2, formed by incubating pre-synthesized 2, also validates that the aromatic-aromatic interactions play the important role in forming the self-assembled nanofibers (Figure S3). Therefore, the morphological transformation of the peptide assemblies via EISA indicates the success of EISA of 1 catalyzed by trypsin-1. Time-dependent circular dichroism (CD) analysis of the peptide assemblies shows that β-sheet (at 220 nm) conformation of the peptide increases over time (Figure 2b), likely due to the increase of the production of 2 and 3 via the enzymatic reaction. The estimation of the secondary structures of the peptide assemblies, formed via 24-h EISA, by DichroWeb program, indicates that the assemblies present predominantly in the β-sheet conformation (50%), plus 2% of α-helix, 23% of turn, and 25% of unordered structures. These results together, including chemical composition and secondary structure of the peptide assemblies, suggest that the 1 acts as a proper substrate for the trypsin-catalyzed EISA.

Figure 2.

Trypsin-instructed self-assembly of 1. (a,b) EISA of 1 at low concentration (200 μM). (a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the assemblies of 1 (top: without trypsin-1, bottom: with trypsin-1). Scale bars: 100 nm. (b) Time-dependent circular dichroism (CD) spectra of 1 assemblies (left), and the percentage of its secondary structure after the 24-h EISA (right). (c,d) EISA of 1 at high concentration (2.5 wt%). (c) Hydrogelation of 1 via 24-h EISA (top: without trypsin-1, bottom: with trypsin-1). (d) Strain sweeps (left) and frequency sweeps (right) of the hydrogel.

Hydrogelation of peptide is a facile approach to intuitively confirm EISA of the designed peptide. A variety of intermolecular noncovalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions, aromatic-aromatic interactions, or hydrophobic interactions, among the peptide product of EISA contributes to the formation of the organized supramolecular structures that entrap the surrounding water molecules, leading to the hydrogelation.[21] Our results show that trypsin-1 catalyzes the cleavage of 1 to form a hydrogel when 1 is at a relatively high concentration (2.5 wt%). Without the addition of trypsin-1, the solution of 1 remains as a liquid at 2.5 wt% (Figure 2c). Using the rheological analysis of the hydrogel, we evaluated the viscoelastic properties of the hydrogel (Figure 2d). The strain sweeps of the hydrogel shows that the values of the storage modulus (G′) dominate those of the loss modulus (G″) with a critical strain of about 10%, indicating that the peptide assemblies made of 2 and 3 form a hydrogel with tolerance to external shear force. The frequency sweep shows that the value of G′ is about 10 times higher than that of G″, suggesting that the hydrogel is viscoelastic.

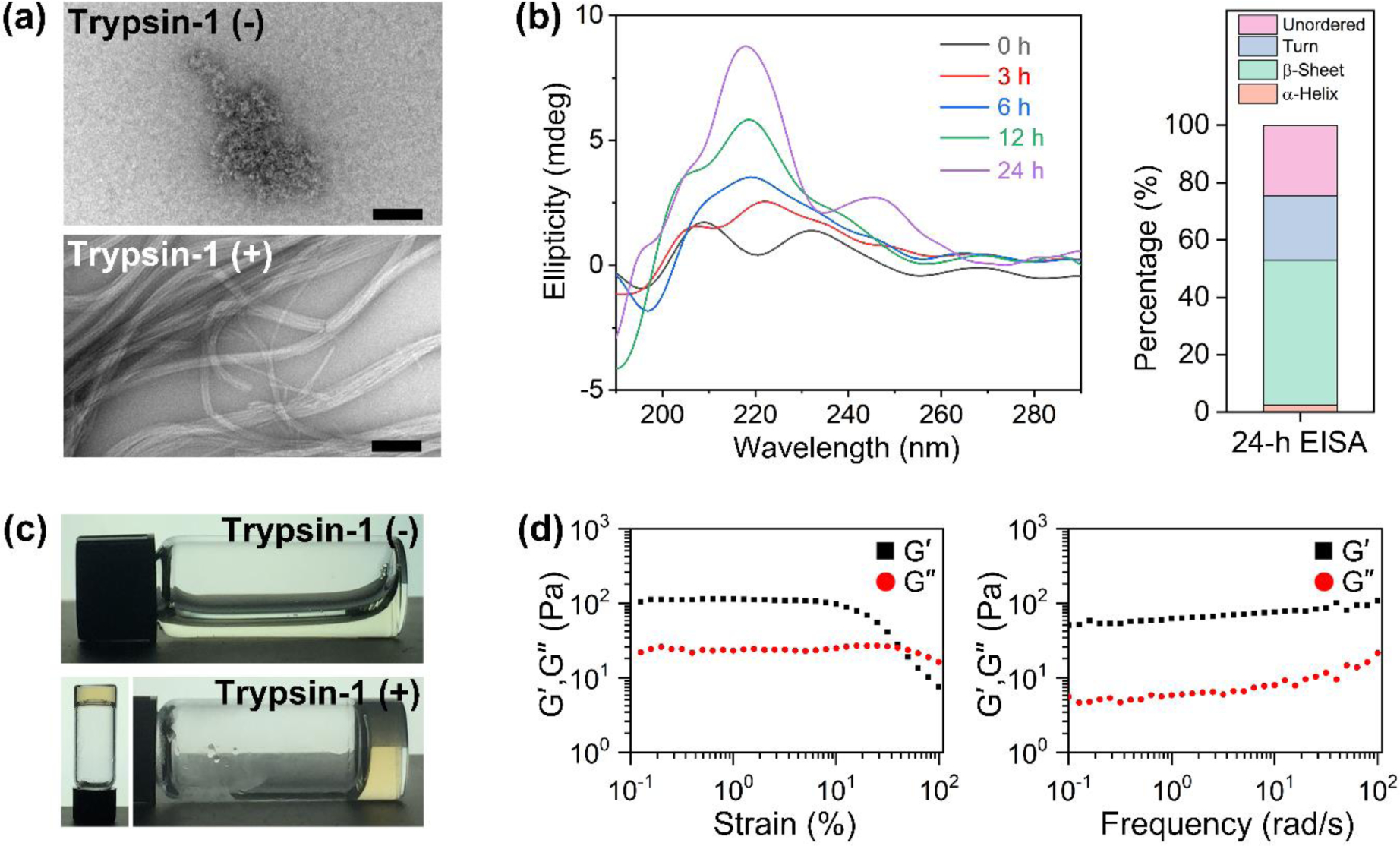

To compare the efficacies of 1 against various cancer cells that express different levels of PRSS1, we firstly obtained the information about the level of PRSS1 expression (i.e., information of copy number and mRNA expression) in the six kinds of human cancer cell lines, including OVSAHO, PC3, SKOV3, A2780, U87MG, and K562 cells, by searching cancer cell line encyclopedia (CCLE) (Figure 3a). CCLE, the bioinformatics database focusing on cancer, provides valuable bioinformation of various human cancer cells.[22] According to CCLE data, OVSAHO cell exhibits the highest level of PRSS1 expression among those cancer cells. In addition, although SKOV3 and A2780 cells cause ovarian carcinoma as OVSAHO cell, those cells show the lower levels of PRSS1 expression than OVSAHO cell. It is already demonstrated that the level of PRSS1 expression differs in ovarian carcinoma cell line, although most ovarian carcinoma cells express PRSS1 for malignant progression and metastatic behaviors.[23] More importantly, normal ovarian cells hardly express PRSS1.[24] Therefore, based on the CCLE data and the previous reports, we expected that OVSAHO cells are a proper target to be inhibited by trypsin-catalyzed EISA.

Figure 3.

Anticancer efficacy of 1 depending on the level of PRSS1 expression. (a) Cancer cell line encyclopedia (CCLE) data: mRNA expression and copy number of PRSS1 in various cancer cells. (b) Cell viabilities of OVSAHO, PC3, and HOSE636 cells treated with 1 or 2 (400 μM) for 48 h. (c) Western blot analysis of PRSS1 in wild type OVSAHO, PC3, and HOSE636 cells.

To confirm our assumption, we treated the six kinds of cancer cell lines and the normal ovarian epithelial cell (HOSE636) with 1 for evaluating the viability of the cells (Figure S5). Upon the treatment of 1, the viability of OVSAHO cells decreases most significantly, while the viability of PC3 cells drops slightly (Figure 3b). On the other hand, the normal ovarian cells, HOSE636, hardly lose any viability upon the treatment of 1. Therefore, the in vitro result of the anticancer efficacy of 1 agrees well with the expression levels of PRSS1 categorized in CCLE database. In addition, the time-independent cytotoxicity of 1 validates that 1 is stable in a variety of cell culture media until 3 days (Figure S5). In order to verify that the anticancer activity of 1 requires the enzymatic reaction (i.e., PRSS1-catalyzed EISA), we used the main molecular product of PRSS1-catalyzed EISA (i.e., 2) to treat to the cancer cells as well as the normal ovarian cell (Figure S6). Similar with the peptide assemblies formed via EISA of 1, 2 is able to form the assemblies, but via the thermodynamic self-assembly (Figure S3). As a result, 2 is still highly compatible to all the three types of cells. Because 3 is generated from 1 and also further degrades to become 2 in cell assay, it is unlikely that 3 would be the major contributor in the inhibition of OVSAHO cells. This result, similar to our previous study,[25] confirms that the peptide assemblies, only when being formed by in situ enzymatic reaction, can effectively kill the targeted cells. Since (i) 1 is ineffective without PRSS1 catalyzed proteolysis and (ii) 2, by itself, is ineffective, the activity must come from the molecular process of EISA. Therefore, this result, again, confirms the fundamental difference between EISA and ligand-receptor interactions for inhibiting cancer cells. To verify the correlation between the level of PRSS1 expression and the therapeutic efficacy of 1, we selected the three types of cell lines based on the anticancer efficacy of 1 (OVSAHO: high-efficacy, PC3: medium-efficacy, HOSE636: non-efficacy), and measured the expression of PRSS1 in each cell by Western blot analysis (Figure 3c). The result shows different levels of the expression of PRSS1 in those cells, and confirms that high level of PRSS1 expression contributes the high inhibitory activity of 1 against OVSAHO.

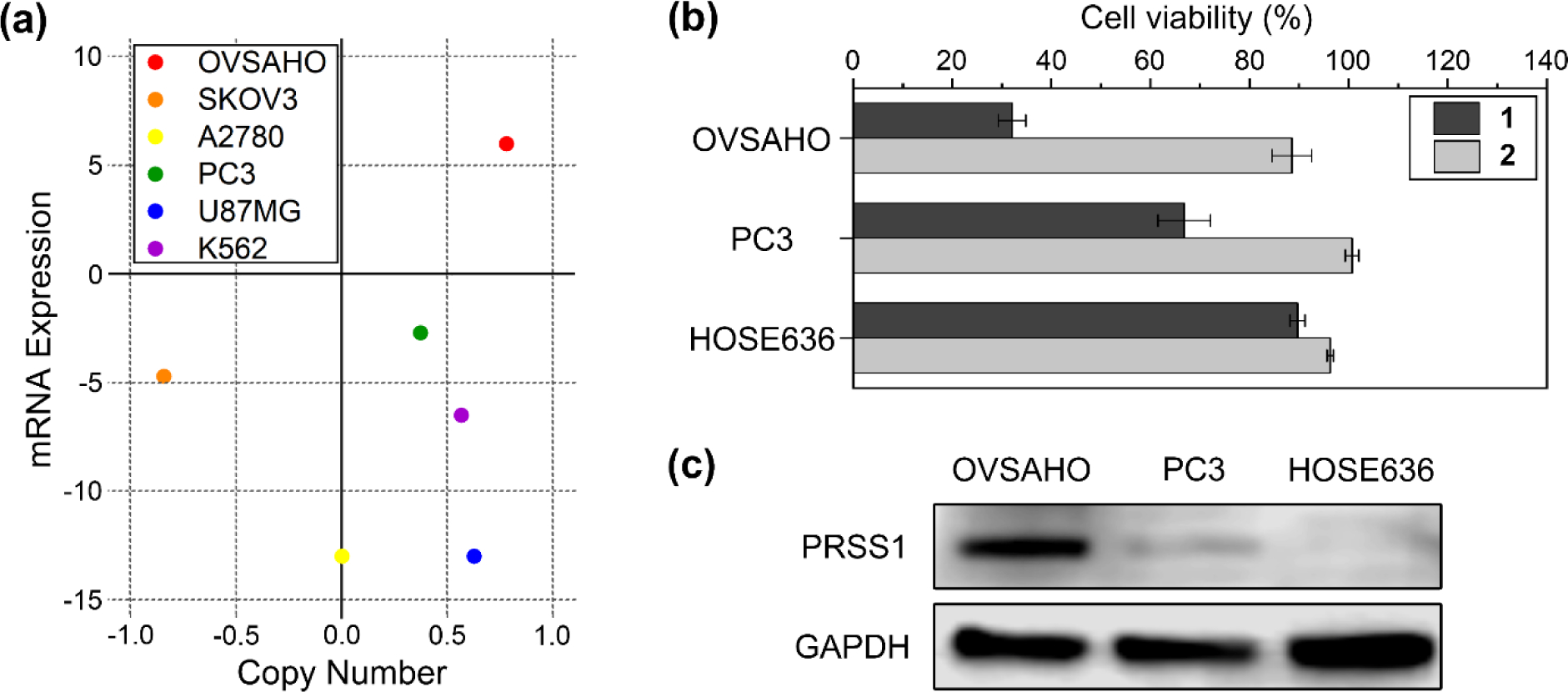

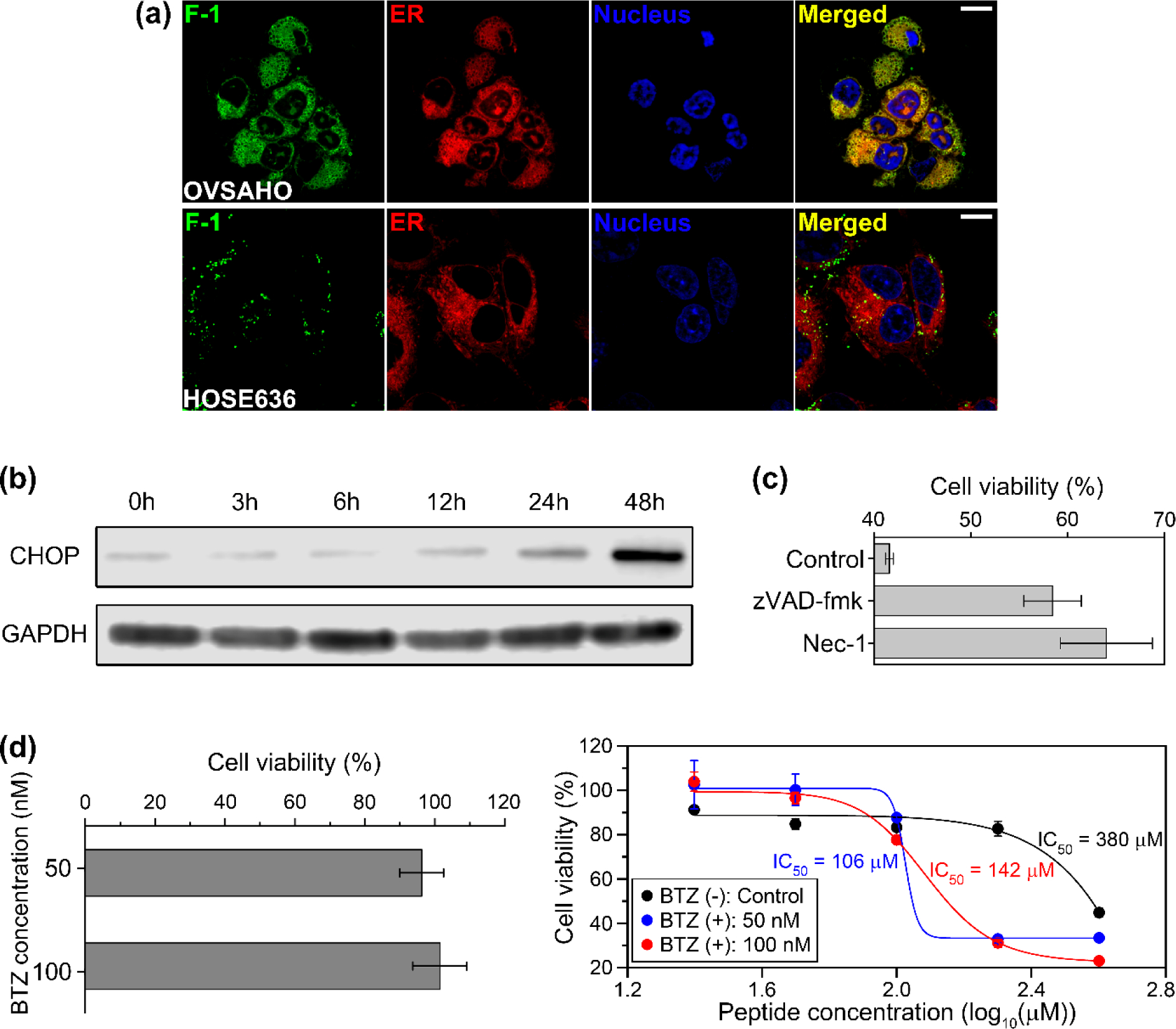

To investigate the mechanism of anticancer property derived from trypsin-catalyzed EISA of 1, it is necessary to track the peptide assemblies formed in the target cells. Therefore, we designed and synthesized F-1 by conjugating a 4-nitro-2, 1, 3-benzoxadiazole (NBD), the environment-sensitive fluorescent dye (Scheme S2). Trypsin-catalyzed EISA of F-1 not only leads to the accumulation of the fluorophores, but also provides the hydrophobic environment to increase the quantum yield of the fluorophores, enabling fluorescence analysis of trypsin-1 activity as well as dynamics and localization of the peptide assemblies in living cells.[26] Because only 400 μM of 1 shows the high efficacy against OVSAHO cell (Figure S4), we treated cells with 400 μM of 1 for the CLSM and ER-stress experiments. CLSM images show that the peptide assemblies accumulate at ER of OVSAHO cell after the treatment with F-1, while ER of HOSE636 cell is free from F-1. (Figure 4a, also see Movie S1). The F-1, uptake by HOSE636 cell, still maintains the spherical shape, implying that EISA of F-1 in HOSE636 cell (Figure S7) is inefficient or F-1 remains in endosomes. Moreover, OVSAHO cells, pre-treated with the trypsin inhibitor (AEBSF, 4-(2-aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride), hardly show the peptide assemblies in/on their cytosol and ER (Figure S8). The colocalization analysis facilitates the evaluation of the molecular target distribution.[27] The fairly high values of Pearson correlation coefficient and Manders’ overlap coefficients, obtained by the colocalization analysis of PRSS1 with ER, validates that PRSS1 also mainly lactates at the ER of OVSAHO cell (Figure S9b). Considering that OVSAHO is a cancer cell, such aberrant location is conceivable. Therefore, most of the molecules of F-1 still should enter the cells for EISA on the ER, although trypsin-1 on the surface of OVSAHO cells likely would cleave small amount of F-1 before endocytosis. In fact, Figure 2b indicates that trypsin-1 unlikely cleaves all the molecules of 1 instantly. Although trypsin-1 on the surface of OVSAHO cells likely would cleave small amount of 1 or F-1 before endocytosis, most of the molecules of 1 or F-1 still should enter the cells for EISA on the ER. Considering PRSS1 is mainly expressed on the ER of OVSAHO cell (Figure S9), these results indicate that the accumulation of the peptide assemblies, being formed by trypsin-catalyzed EISA on the ER, results in the inhibitory activity of 1.

Figure 4.

Study of inhibitory activity against cancer cells. (a) Confocal laser-scanning microscopy (CLSM) images of OVSAHO (top) and HOSE636 (bottom) cells treated with F-1 (400 μM) for 2 hours. All cells were stained with ER-Tracker™ red (for ER) and Hoechst 33342 (for nucleus). Scale bars: 10 μm. (b) Time-dependent Western blot analysis of ER-stress marker (CHOP) after treating OVSAHO cells with 1 (400 μM). (c) Cell viability of OVSAHO cells treated by 1 (400 μM) for 24 h in the presence of cell death signaling inhibitors (45 μM zVAD-fmk or 50 μM Nec-1). (d) 24-h cell viabilities of OVSAHO cells treated with solely bortezomib (BTZ) (left) and various concentrations of 1 in combination with BTZ (right).

To verify the anticancer activity induced from the accumulation of the peptide assemblies on ER, we performed the time-dependent of Western blot analysis to investigate the expression of ER stress marker (CHOP) (Figure 4b). The result shows that the level of CHOP, a unfolded protein response (UPR) mediator, in the OVSAHO cells treated with 1 increases with time, indicating that the peptide assemblies accumulate on ER to induce ER stress.[28] Because ER stress causes both apoptosis and necroptosis,[29] we incubated the OVSAHO cells, pre-treated with the inhibitors of apoptosis (zVAD-fmk) or necroptosis (Nec-1, necrostatin-1), with 1 (Figure 4c).[30] Our results indicate that the apoptosis inhibitor or the necroptosis inhibitor can only partially rescue the OVSAHO cells treated with 1, supporting that the peptide assemblies trigger ER stress to kill the OVSAHO cells via multiple death pathways.

To enhance the efficacy of EISA of 1 for inhibiting OVSAHO cancer cell, we treated OVSAHO cells with 1 in combination with bortezomib (BTZ), a proteasome inhibitor because BTZ is able to inhibit proteasome and suppress the NF-κB signaling pathway for the down-regulation of anti-apoptotic target gene.[31] At relatively low concentrations (50 nM and 100 nM), BTZ, although being cell compatible (Figure 4d), markedly enhances the cytotoxicity of 1. BTZ decreases the IC50 value of 1 from 380 μM to 106 μM or 142 μM, depending on the concentration of BTZ. Considering the CMC of 1 is 194 μM (Figure S3) and cells uptake peptide micelles via endocytosis,[14a, 32] it is reasonable that the viability of OVSAHO cell treated with BTZ drops significantly when the concentration of 1 is between 100 μM and 200 μM. Moreover, we confirm that EISA confers the synergism with BTZ for inhibiting OVSAHO cells when the concentration of 1 is above CMC by calculating the combination index (CI) of 1 and BTZ (Table S1).

In summary, this work demonstrates in situ trypsin-catalyzed EISA on ER with the high selectivity for inhibiting cancer cells, and provides a new approach for organelle targeting of cancer cells. Moreover, by the mechanism analysis of trypsin-instructed self-assembly in cellular milieu, this work reveals a new information that PRSS1 expresses on the ER of OVSAHO cell, suggesting that EISA also can act as an effective strategy to discover aberrant subcellular activities of enzymes in cancer cells. Based on the colocalization assay via PRSS1 immunostaining, PRSS1 is mainly expressed on the ER, less on the surface, of OVSAHO cell (Figure S9). This result excludes the possibility that majority of 1 are cleaved on cell surface before endocytosis. Although the driving force for 1 to approach remains to be elucidated, we speculate that the positive charges[33] from the branch of 1 may help 1 to approach ER before EISA. The synergy effect between BTZ and 1 offers a simple approach to enhance the efficacy of EISA, albeit the anticancer efficacy of 1 remains to be improved. In addition, it is possible to adopt a variety of strategies, such as enhancement of cellular uptake[34] and improvement of self-assembly ability,[35] for increasing the efficacy. Considering specific enzymes are mainly expressed in/on subcellular organelles (e.g., lysosomal hydrolase),[36] this approach introduced here should be useful for precisely targeting other subcellular organelles, including lysosome, Golgi, and nucleus.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by NIH (CA142746).

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor George M. Whitesides on the occasion of his 80th birthday

Supporting Information

Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

References

- [1].Pavet V, Portal M, Moulin J, Herbrecht R, Gronemeyer H, Oncogene 2011, 30, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cheetham AG, Chakroun RW, Ma W, Cui H, Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 6638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Kim BJ, Xu B, Bioconjugate Chem. 2020, 31, 492; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou J, Xu B, Bioconjugate Chem. 2015, 26, 987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].a) Yang Z, Xu K, Guo Z, Guo Z, Xu B, Adv. Mater 2007, 19, 3152; [Google Scholar]; b) Kuang Y, Shi J, Li J, Yuan D, Alberti KA, Xu Q, Xu B, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2014, 53, 8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Wang H, Feng Z, Wang Y, Zhou R, Yang Z, Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 16046; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Wang H, Feng Z, Yang C, Liu J, Medina JE, Aghvami SA, Dinulescu DM, Liu J, Fraden S, Xu B, Mol. Cancer Res 2019, 17, 907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Zhan J, Cai Y, He S, Wang L, Yang Z, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2018, 57, 1813; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liang C, Zheng D, Shi F, Xu T, Yang C, Liu J, Wang L, Yang Z, Nanoscale 2017, 9, 11987; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Pires RA, Abul-Haija YM, Costa DS, Novoa-Carballal R, Reis RL, Ulijn RV, Pashkuleva I, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 576; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Tanaka A, Fukuoka Y, Morimoto Y, Honjo T, Koda D, Goto M, Maruyama T, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 770; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e) Yuan Y, Wang L, Du W, Ding Z, Zhang J, Han T, An L, Zhang H, Liang G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54, 9700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Dong L, Qian J, Hai Z, Xu J, Du W, Zhong K, Liang G, Anal. Chem 2017, 89, 6922; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yuan Y, Zhang J, Qi X, Li S, Liu G, Siddhanta S, Barman I, Song X, McMahon MT, Bulte JW, Nat. Mater 2019, 18, 1376; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Huang P, Gao Y, Lin J, Hu H, Liao H-S, Yan X, Tang Y, Jin A, Song J, Niu G, ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9517; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d) Liu Y, Miao Q, Zou P, Liu L, Wang X, An L, Zhang X, Qian X, Luo S, Liang G, Theranostics 2015, 5, 1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Sakhrani NM, Padh H, Drug Des. Dev. Ther 2013, 7, 585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pan L, Liu J, Shi J, Chem. Soc. Rev 2018, 47, 6930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Muratovska A, Lightowlers RN, Taylor RW, Wilce JA, Murphy MP, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2001, 49, 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Groth-Pedersen L, Jäättelä M, Cancer Lett. 2013, 332, 265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Banerjee S, Zhang W, ChemBioChem 2018, 19, 2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Biswas S, Torchilin VP, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 2014, 66, 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].a) Rai AK, Chen JX, Selbach M, Pelkmans L, Nature 2018, 559, 211; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) He H, Guo J, Lin X, Xu B, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed DOI: 10.1002/anie.202000983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [15].a) Urra H, Dufey E, Avril T, Chevet E, Hetz C, Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 252; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Schwarz DS, Blower MD, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2016, 73, 79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Verfaillie T, Garg AD, Agostinis P, Cancer Lett. 2013, 332, 249; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hetz C, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2012, 13, 89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) Feng Z, Wang H, Wang S, Zhang Q, Zhang X, Rodal AA, Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 9566; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang S, Hu X, Mang D, Sasaki T, Zhang Y, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 7474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liang G, Ren H, Rao J, Nat. Chem 2010, 2, 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lock LL, Reyes CD, Zhang P, Cui H, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 3533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Miyata S, Koshikawa N, Higashi S, Miyagi Y, Nagashima Y, Yanoma S, Kato Y, Yasumitsu H, Miyazaki K, J. Biochem 1999, 125, 1067; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Weissleder R, Tung C-H, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A, Nat. Biotechnol 1999, 17, 375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Du X, Zhou J, Shi J, Xu B, Chem. Rev 2015, 115, 13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, Wilson CJ, Lehár J, Kryukov GV, Sonkin D, Nature 2012, 483, 603; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia Consortium & The Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer Consortium, Nature 2015, 528, 84.26570998 [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hirahara F, Miyagi Y, Miyagi E, Yasumitsu H, Koshikawa N, Nagashima Y, Kitamura H, Minaguchi H, Umeda M, Miyazaki K, Int. J. Cancer 1995, 63, 176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hirahara F, Miyagi E, Nagashima Y, Miyagi Y, Yasumitsu H, Koshikawa N, Nakatani Y, Nakazawa T, Udagawa K, Kitamura H, Gynecol. Oncol 1998, 68, 162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Du X, Zhou J, Wang H, Shi J, Kuang Y, Zeng W, Yang Z, Xu B, Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].a) Gao Y, Shi J, Yuan D, Xu B, Nat. Commun 2012, 3, 1; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou J, Du X, Berciu C, He H, Shi J, Nicastro D, Xu B, Chem 2016, 1, 246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Dunn KW, Kamocka MM, McDonald JH, Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol 2011, 300, C723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nishitoh H, J. Biochem 2012, 151, 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Saveljeva S, Mc Laughlin S, Vandenabeele P, Samali A, Bertrand M, Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G, Cell Res. 2019, 29, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Chen D, Frezza M, Schmitt S, Kanwar J, P Dou Q, Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2011, 11, 239; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhou J, Du X, Chen X, Wang J, Zhou N, Wu D, Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Li X, Li B, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun X, Yu Y, Wang L, Yu J, Future Oncol. 2019, 15, 995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Ziska A, Tatzelt J, Dudek J, Paton AW, Paton JC, Zimmermann R, Haßdenteufel S, Biol. Open 2019, 8, bio040691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Zhou J, Du X, Li J, Yamagata N, Xu B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2015, 137, 10040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Feng Z, Wang H, Du X, Shi J, Li J, Xu B, Chem. Commun 2016, 52, 6332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Piao S, Amaravadi RK, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 2016, 1371, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.