Abstract

Neuropsychiatric disorders (NPDs) have multiple etiological factors, mainly genetic background, environmental conditions and immunological factors. The host immune responses play a pivotal role in various physiological and pathophysiological process. In NPDs, inflammatory immune responses have shown to be involved in diseases severity and treatment outcome. Inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are involved in various neurobiological pathways, such as GABAergic signaling and neurotransmitter synthesis. Infectious agents are among the major amplifier of inflammatory reactions, hence, have an indirect role in the pathogenesis of NPDs. As such, some infections directly affect the central nervous system (CNS) and alter the genes that involved in neurobiological pathways and NPDs. Interestingly, the most of infectious agents that involved in NPDs (e.g., Toxoplasma gondii, cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex virus) is latent (asymptomatic) and co-or-multiple infection of them are common. Nonetheless, the role of co-or-multiple infection in the pathogenesis of NPDs has not deeply investigated. Evidences indicate that co-or-multiple infection synergically augment the level of inflammatory reactions and have more severe outcomes than single infection. Hence, it is plausible that co-or-multiple infections can increase the risk and/or pathogenesis of NPDs. Further understanding about the role of co-or-multiple infections can offer new insights about the etiology, treatment and prevention of NPDs. Likewise, therapy based on anti-infective and anti-inflammatory agents could be a promising therapeutic option as an adjuvant for treatment of NPDs.

Keywords: Infection, Inflammation, Neuropsychiatric disorders, Co-infection, Immunology, Microbiology, Infectious disease, Psychiatry

Infection; Inflammation; Neuropsychiatric disorders; Co-infection; Immunology; Microbiology; Infectious disease; Psychiatry.

1. Introduction

Neuropsychiatric disorders (NPDs) are among the most important morbidity and mortality worldwide [1,2]. According to the estimation, the global burden of mental illness accounts for 13.0% of disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) and 32·4% of years lived with disability (YLDs) [1]. Several factors, including environmental conditions, genetic background, immune dysregulation and some infectious agents are known to be involved in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs [3, 4, 5, 6]. In recent years, different investigations have shown the roles of inflammation in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs and anti-inflammatory agents as a therapeutic target of NPDs [7]. On the other hand, association of different NPDs with some infectious agents (Table 1), especially maternal infections have been demonstrated in various studies [8, 9]. Beyond the direct effects on the CNS, infections can augment inflammatory pathways, and consequently may have indirect roles in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs [10, 11, 12]. As well, the most of infectious agents that involved in NPDs, such as Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV) and Epstein Barr virus (EBV) is asymptomatic (latent) and co-or-multiple infection of them are common [13, 14, 15, 16, 17]. Although association of single infection with NPDs have been investigated in many studies [18, 19, 20, 21], little is known about the association of co-or-multiple infections and NPDs. Because co-or-multiple infections have more adverse outcome than single infection [22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30], the major question of this article is: May co-or-multiple infections enhance the risk of NPDs? And, what is the possible association of co-or-multiple infections with NPDs?

Table 1.

A snapshot on microbiology of the major infectious agents that involved in NPDs.

| Infectious agent | Microbiology, transmission, and prevalence | Major symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| T. gondii |

|

|

| CMV |

|

|

| HSV |

|

|

| Rubella |

|

|

| EBV |

|

|

| Influenza |

|

|

| VZV |

|

|

| BDV |

|

|

| Chlamydia pneumoniae |

|

|

2. Theory/hypothesis

Several indirect links proposed that co-or-multiple infections may be more involved in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs than single infection: 1) Some infections are associated with NPDs; 2) infections are associated with inflammation; 3) inflammation is associated with NPDs; 4) co-or-multiple infections enhanced a higher level of inflammatory biomarkers than single infections; 5) co-or-multiple infections have more severe outcome than single infection; Hence 6) co-or-multiple infections may have more influence in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs than single infection.

3. Evidences of the hypothesis

3.1. Inflammation and NPDs

In recent years, psychoneuroimmunology is a hot topic issue in NPDs and different studies have been focused on the role of immune disturbances in the etiology of NPDs [5, 31]. As reviewed elsewhere, inflammatory mediators are able to interact with multiple biological pathways related to NPDs, such as neuroendocrine activity, synaptic plasticity, neurocircuits as well as neurotransmitters and monoamine metabolism [31, 32]. For instance, neuroinflammation activate the kynurenine pathway that can modulate the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and diminish serotonin production, which consequently is involved in several NPDs, such as depressive disorders [8]. Inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α increase blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability, and blocking of them decreases stress-induced BBB opening [33, 34]. The result of a recent meta-analysis [12] demonstrated a significant increase in the levels of IL-17, IL-23, IL-6, TNF-α, soluble IL-2 receptor (sIL-2R), and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA) in acutely ill patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), schizophrenia, and bipolar mania compared with controls (P < 0.01). Indeed, a significant increase in the levels of IL-1β and sIL-2R was detected in patients with chronic schizophrenia and bipolar disorder [12]. Recent researches have shown that macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) plays a protective role in the development of MDD by upregulating the PI3k/Akt/mTOR pathway and production of inflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNFα [35, 36, 37]. On the other hand, in-vitro, in-vivo, and ex-vivo preclinical data, as well as data from Alzheimer' s disease patients have shown that MIF is increased during the course of the disease and that therapeutic targeting of MIF could beneficial effects on the Alzheimer' s disease course [38].

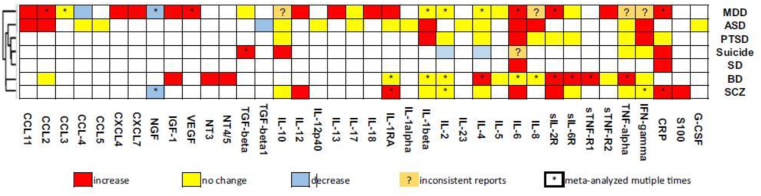

In an excellent article, Yuan et al. [39] performed an umbrella review of the meta-analyses regarding alterations of 38 inflammation-related factors in major NPDs. This study summarized the changes of different cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors in NPDs (Figure 1). Functionally, cytokines and chemokine are divided into proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory subsets. Abnormal levels of both pro-and anti-inflammatory cytokines and chemokine were detected in several NPDs (Figure 1) [39, 40, 41].

Figure 1.

Alterations of 38 inflammatory mediators in patients with different NPDs. schizophrenia (SCZ), bipolar disorder (BD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), major depression disorder (MDD), post-trauma stress disorder (PTSD), sleeping disorder (SD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and suicide. Reproduced from reference [39] (Open access article under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License).

3.2. Autoimmunity and NPDs

The association between autoimmune disorders with NPDs is another evidence that link between inflammation and NPDs [42, 43, 44]. So, higher co-morbidity of some autoimmune diseases and NPDs have been reported from the epidemiological investigations [44, 45, 46]. In a recent meta-analysis, Siegmann et al. [46] showed that patients with autoimmune thyroiditis had significantly higher scores on depression (OR = 3.56) and anxiety disorders (OR = 2.32). Depression and anxiety disorders are increased in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) as well [47]. In a cohort study among 5084 MS patients, the OR of depression and anxiety disorders was 1.4 and 1.23 in the prediagnostic period and the post-diagnostic period, respectively [48]. Rossi et al. [48] found that depression and anxiety disorders significantly increase inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL1-β, and IL-2 in the CSF samples of MS patients in the relapsing-remitting stage of the disease [49]. TH17 cells which has a highly inflammatory properties plays a critical pathogenic role in several autoimmune diseases [31]. Among the psoriasis patients, anti-IL-17A therapy resulted in remission of depression in about 40% of the patients with severe depression [50]. Depressive disorders are not only common in patients with diabetes [51, 52], but also increase risk of mortality among these patients (HR = 1.46) [53]. Psychiatric co-morbidity is also common in patients with other autoimmune disorders, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [54, 55], Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [56] and psoriasis [57].

3.3. Anti-inflammatory treatment for NPDs

Anti-inflammatory agents can be used as an adjuvant in combination with anti-psychotic drugs [58]. The results of different meta-analysis revealed a diminished level of depressive symptoms after anti-inflammatory treatment [59]. Indeed, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs significantly improved the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia patients [60]. In contrast, Quereda and colleagues [61] showed that treatment with Efavirenz and α-interferon in patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) and HIV co-infection were partially led to mood disorders. On the other hand, it has been suggested that an imbalanced production of cytokines may be involved in the pathogenesis and maintenance of NPDs. Taken together, cumulative evidences suggest the beneficial role of anti-inflammatory treatment as an adjuvant in treatment of NPDs.

3.4. Antipsychotic therapy modulates inflammatory biomarkers of NPDs

Another evidence that is shown the association of inflammation and NPDs is the effects of antipsychotic therapy on levels of inflammatory biomarkers. While clinical and experimental evidences reveal that the major antipsychotic agents, including lithium, haloperidol, valproate acid, perazine, clomipramine, fluoxetine and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) led to modulation of inflammatory biomarkers [58, 62, 63]. For instance, the SSRIs decreased peripheral levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-10 [64]. In vitro studies also revealed that inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) production were significantly impeded after exposure to haloperidol [65, 66]. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that clomipramine and fluoxetine decrease inflammatory cytokines IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, whilst venlafaxine and mirtazapine augment their levels [63].

3.5. Association of latent infections with NPDs

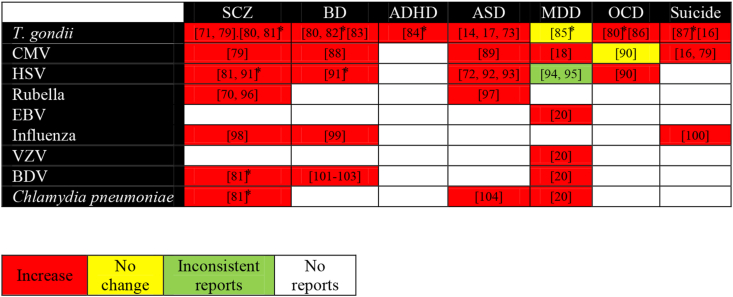

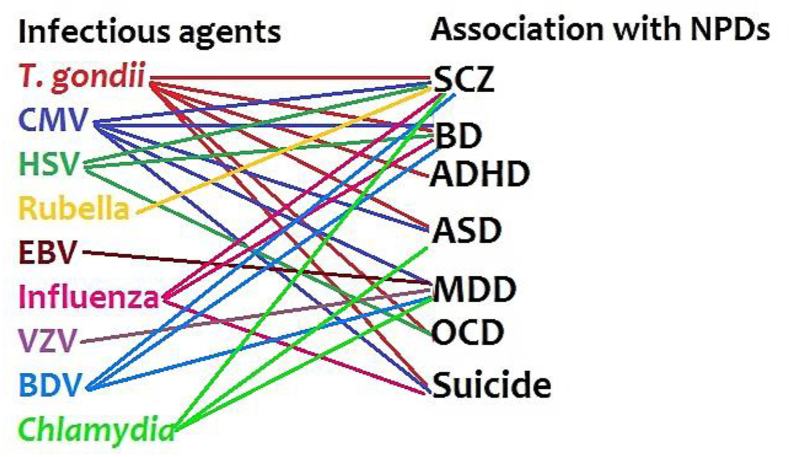

Inflammation is induced by multiple stimulating factors, including infectious agents [67]. Hence, infections act as an inflammation amplifier which consequently involves in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs. Till now, a number of researches demonstrated a positive correlation of different NPDs with several infectious agents (Table 1), including T. gondii, CMV, HSV, EBV, rubella, measles, influenza, Borna disease virus (BDV), varicella zoster virus (VZV) [13, 14, 19, 68], and Chlamydia [18, 20] infection (Figures 2 and 3). Beyond the direct effects of infections on the central nervous system (CNS), infections affect the immune system that leads to product inflammatory mediators, such as immune cells and cytokines. These mediators can pass through the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and generate neuroinflammation [8]. As such, maternal infections in pregnant women can increase risk of NPDs in the offspring in later life [14, 17, 69, 70, 71, 72]. On the other hand, depression increased the risk of infections among women with coronary artery bypass grafting compared to non-depressed women [73]. Despite the positive correlations between infections and NPDs, limited information is available about the role of co-or multiple-infections in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs.

Figure 2.

Association of single infections with NPDs. The related references are inserted in each box. ∗ Meta-analysis. [79], [80], [81], [82], [83], [84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92], [93], [94], [95], [96], [97], [98], [99], [100], [101].

Figure 3.

Association of infectious agents with NPDs (based on Figure 2).

3.6. Evidences for synergetic role of co-or-multiple infections on outcome of the diseases

Quite a few studies have demonstrated that co-or-multiple infections synergically enhance severity of the diseases. For example, viral co-infection has several virological and immunological consequences, such as enhanced virus replication and persistence, altered disease intensity and altered immunological responses [24]. In the “Spanish flu” pandemic, 95% of the mortality was attributed to co-infection with bacterial pneumonia as well [26]. Co-infection of Streptococcus pneumoniae with influenza virus promotes inflammatory responses with a strong IL-17A response that led to enhanced S. pneumoniae disease intensity in the nasopharynx of infected animals [103]. In vitro study in the human monocytic cell lines revealed that co-exposure of influenza virus with Staphylococcus aureus toxins enhanced pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [23]. HIV and hepatitis C virus co-infection promote hepatocellular injury that is linked to elevation of certain inflammatory cytokines [104]. In the HIV-infected patients, co-infection with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was associated with a persistent inflammation and immune activation [25]. Previous studies showed that maternal infection with ToRCH (toxoplasmosis, rubella, CMV and HSV) co-infection was associated with increased risk of abortion in pregnant women than their single infection [27]. As such, some studies indicated that co-infections synergically enhance the level of inflammatory mediators. In this regard, Souza et al. [30] reported that chronic infection with T. gondii exacerbates secondary polymicrobial sepsis in an experimental mouse model and in a human survey. The results revealed that chronic T. gondii infection suppresses anti-inflammatory T helper (TH)-2 cells and simultaneously intensifies local and systemic inflammatory TH1 cells and their inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and nitric oxide (NO) [30]. These phenomena were resulted in reduced diastolic and systolic blood pressures after induction of sepsis and led to a severe outcome than uninfected T. gondii mice with sepsis [30]. A clinical study was also performed by the same group of the researchers [30] regarding the correlation of T. gondii seropositivity with inflammatory biomarkers in patients with sepsis. They found that the sepsis severity was positively correlated with increased IFN-γ levels in T. gondii seropositive patients compare with T. gondii seronegative septic patients [30]. Hence, accumulating evidence reveals that co-or-multiple infections have more severe outcomes than single infection [22].

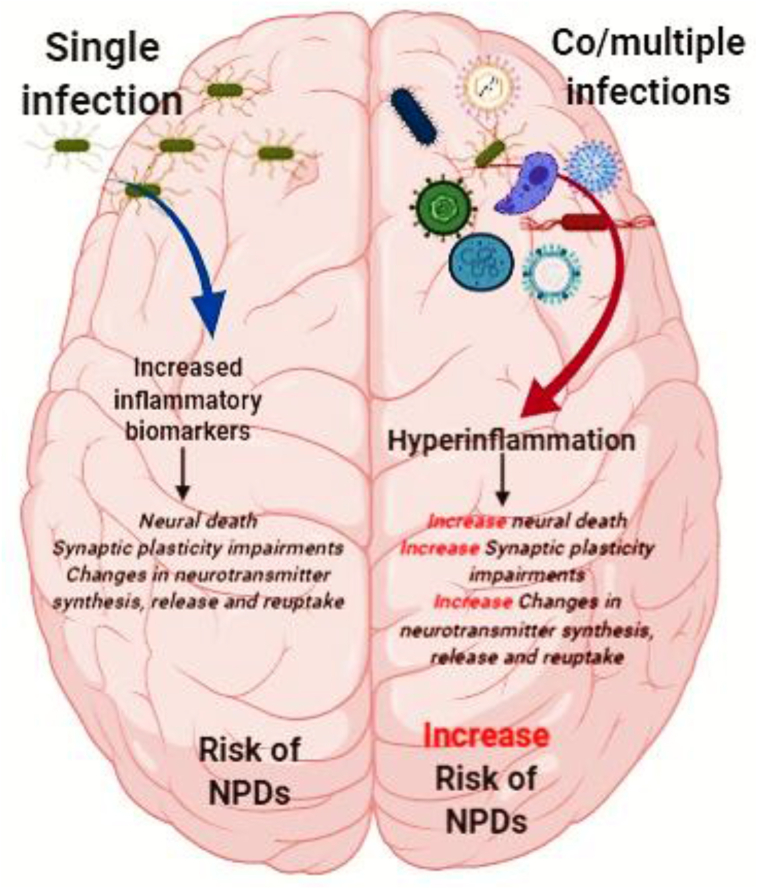

3.7. Possible role of co-or-multiple infections in increased risk of NPDs

In a large-scale study among Danish individuals with various psychiatric disorders, Burgdorf and colleagues [78] found a significant association between T. gondii and schizophrenia, and between CMV and attempting or committing suicide, neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders, and mood disorders. Nevertheless, T. gondii and CMV co-infection did not influence the overall findings [78]. Although, the levels of inflammatory markers were not reported in this study [78]. Nicolson et al [102] found that prevalence of either single infection or co-infection of Mycoplasma ssp., Chlamydia pneumoniae, and Human Herpes Virus-6 were higher in patients with ASD than the control group. Some studies have shown that patients with HCV and HIV co-infection may be at higher risk for depressive disorders than single infection [105, 106, 107]. Aibibula and colleagues [105] demonstrated that HIV patients with depressive symptoms had 1.32 times higher risk of HIV viremia. As such, in HIV-HCV co-infected patients, occurrence of depressive symptoms were a risk factor for persistent HIV viremia [105]. To our knowledge, there are not any immunological analyses regarding the influences of co-or-multiple infections in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs until now. Hence, it seems that co-or-multiple infections is a neglected topic in the area of NPDs (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

A hypothetical scheme on the possible role of single infection or co-or-multiple infections in the pathogenesis of NPDs. (The figure designed by BioRender online software).

4. Conclusion and future directions

As mentioned, various studies have shown the role of single infections in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs, but, the role of co-infections have not deeply investigated. Torrey and Yolken [6] mentioned that the role of genetic background in the etiology of schizophrenia may have been overestimated and an increased attention to gene-environmental interactions can accelerate research development on this disease. Furthermore, interaction of infectious agents with microbiota composition can produce a better clinical picture of NPDs [6]. The idea of infectious cause NPDs may open new opportunities for treatment of NPDs with some antibiotics, antiviral or antiprotozoal agents. As well, investigations on the role co-or-multiple infections can provide new insides into the pivotal role of infectious in the etiopathogenesis of NPDs rather than other etiological factors (e.g., genetic background). Further understanding about the influences of co-or-multiple on NPDs can provide new insights about the etiology, treatment, and prevention of NPDs.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

All authors listed have significantly contributed to the development and the writing of this article.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgement

The authors appreciate from two anonymous referees for their excellent comments that improved the quality of our article.

References

- 1.Vigo D., Thornicroft G., Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psych. 2016;3(2):171–178. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker E.R., McGee R.E., Druss B.G. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis mental disorder Mortality Mental disorder mortality. JAMA Psych. 2015;72(4):334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burmeister M., McInnis M.G., Zöllner S. Psychiatric genetics: progress amid controversy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9(7):527. doi: 10.1038/nrg2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Os J., Kenis G., Rutten B.P. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature. 2010;468(7321):203. doi: 10.1038/nature09563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khandaker G.M., Cousins L., Deakin J., Lennox B.R., Yolken R., Jones P.B. Inflammation and immunity in schizophrenia: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Lancet Psych. 2015;2(3):258–270. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torrey E.F., Yolken R.H. Schizophrenia as a pseudogenetic disease: a call for more gene-environmental studies. Psychiatr. Res. 2019;278:146–150. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pape K., Tamouza R., Leboyer M., Zipp F. Immunoneuropsychiatry — novel perspectives on brain disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019;15(6):317–328. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0174-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Labrie V., Brundin L. Harbingers of mental disease—infections associated with an increased risk for neuropsychiatric illness in children. JAMA Psych. 2018;20019(76):3. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köhler-Forsberg O., Petersen L., Gasse C., Mortensen P.B., Dalsgaard S., Yolken R.H. A nationwide study in Denmark of the association between treated infections and the subsequent risk of treated mental disorders in children and adolescents. JAMA Psych. 2019;76(3):271–279. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes B.S., Steiner J., Molendijk M.L., Dodd S., Nardin P., Gonçalves C.-A. C-reactive protein concentrations across the mood spectrum in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psych. 2016;3(12):1147–1156. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraguas D., Díaz-Caneja C.M., Ayora M., Hernández-Álvarez F., Rodríguez-Quiroga A., Recio S. Oxidative stress and inflammation in first-episode psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Bull. 2018;45(4):742–751. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldsmith D., Rapaport M., Miller B. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol. Psychiatr. 2016;21(12):1696. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdoli A., Dalimi A. Are there any relationships between latent Toxoplasma gondii infection, testosterone elevation, and risk of autism spectrum disorder? Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2014;8:339. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2014.00339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdoli A., Dalimi A., Arbabi M., Ghaffarifar F. Neuropsychiatric manifestations of latent toxoplasmosis on mothers and their offspring. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2014;27(13):1368–1374. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2013.858685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coryell W., Wilcox H., Evans S.J., Pandey G.N., Jones-Brando L., Dickerson F. Latent infection, inflammatory markers and suicide attempt history in depressive disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;270:97–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flegr J., Horacek J. Negative effects of latent toxoplasmosis on mental health. Front. Psychiatr. 2019;10:1012. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.01012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ford B.N., Yolken R.H., Aupperle R.L., Teague T.K., Irwin M.R., Paulus M.P. Association of early-life stress with cytomegalovirus infection in adults with major depressive disorder. JAMA Psych. 2019;76(5):545–547. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arias I., Sorlozano A., Villegas E., de Dios Luna J., McKenney K., Cervilla J. Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2012;136(1-3):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X., Zhang L., Lei Y., Liu X., Zhou X., Liu Y. Meta-analysis of infectious agents and depression. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:4530. doi: 10.1038/srep04530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khandaker G., Zimbron J., Lewis G., Jones P. Prenatal maternal infection, neurodevelopment and adult schizophrenia: a systematic review of population-based studies. Psychol. Med. 2013;43(2):239–257. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orlovska S., Vestergaard C.H., Bech B.H., Nordentoft M., Vestergaard M., Benros M.E. Association of streptococcal throat infection with mental disorders: testing key aspects of the PANDAS hypothesis in a nationwide study. JAMA Psych. 2017;74(7):740–746. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hunter P. Co-infection: when whole can be greater than the sum: the complex reaction to co-infection of different pathogens can generate variable symptoms. EMBO Rep. 2018;19(8) doi: 10.15252/embr.201846601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jeannoel M., Casalegno J.-S., Ottmann M., Badiou C., Dumitrescu O., Lina B. Synergistic effects of influenza and Staphylococcus aureus toxins on inflammation activation and cytotoxicity in human monocytic cell lines. Toxins. 2018;10(7):286. doi: 10.3390/toxins10070286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar N., Sharma S., Barua S., Tripathi B.N., Rouse B.T. Virological and immunological outcomes of coinfections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2018;31(4):e00111–e00117. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00111-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masiá M., Robledano C., de la Tabla V.O., Antequera P., Lumbreras B., Hernández I. Coinfection with human herpesvirus 8 is associated with persistent inflammation and immune activation in virologically suppressed HIV-infected patients. PloS One. 2014;9(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0105442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morens D.M., Taubenberger J.K., Fauci A.S. Predominant role of bacterial pneumonia as a cause of death in pandemic influenza: implications for pandemic influenza preparedness. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198(7):962–970. doi: 10.1086/591708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rasti S., Ghasemi F.S., Abdoli A., Piroozmand A., Mousavi S.G.A., Fakhrie-Kashan Z. ToRCH “co-infections” are associated with increased risk of abortion in pregnant women. Congenital. Anom. 2016;56(2):73–78. doi: 10.1111/cga.12138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rinaldo C.R., Richter B.S., Black P.H., Callery R., Chess L., Hirsch M.S. Replication of herpes simplex virus and cytomegalovirus in human leukocytes. J. Immunol. 1978;120(1):130–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shmagel K.V., Saidakova E.V., Shmagel N.G., Korolevskaya L.B., Chereshnev V.A., Robinson J. Systemic inflammation and liver damage in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection. HIV Med. 2016;17(8):581–589. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Souza M.C., Fonseca D.M., Kanashiro A., Benevides L., Medina T.S., Dias M.S. Chronic Toxoplasma gondii infection exacerbates secondary polymicrobial sepsis. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2017;7:116. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beurel E., Toups M., Nemeroff C.B. The bidirectional relationship of depression and inflammation: double trouble. Neuron. 2020;107(2):234–256. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haroon E., Raison C.L., Miller A.H. Psychoneuroimmunology meets neuropsychopharmacology: translational implications of the impact of inflammation on behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(1):137–162. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng Y., Desse S., Martinez A., Worthen R.J., Jope R.S., Beurel E. TNFα disrupts blood brain barrier integrity to maintain prolonged depressive-like behavior in mice. Brain Behav. Immun. 2018;69:556–567. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Menard C., Pfau M.L., Hodes G.E., Kana V., Wang V.X., Bouchard S. Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20(12):1752–1760. doi: 10.1038/s41593-017-0010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petralia M.C., Fagone P., Basile M.S., Lenzo V., Quattropani M., Bendtzen K. Pathogenic contribution of the Macrophage migration inhibitory factor family to major depressive disorder and emerging tailored therapeutic approaches. J. Affect. Disord. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Günther S., Fagone P., Jalce G., Atanasov A.G., Guignabert C., Nicoletti F. Role of MIF and D-DT in immune-inflammatory, autoimmune, and chronic respiratory diseases: from pathogenic factors to therapeutic targets. Drug Discov. Today. 2019;24(2):428–439. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira C.S., de Bock C.E., Molloy T.J., Sadeqzadeh E., Geng X.Y., Hersey P. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor engages PI3K/Akt signalling and is a prognostic factor in metastatic melanoma. BMC Canc. 2014;14(1):630. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Petralia M.C., Battaglia G., Bruno V., Pennisi M., Mangano K., Lombardo S.D. The role of macrophage migration inhibitory factor in alzheimer′ s disease: conventionally pathogenetic or unconventionally protective? Molecules. 2020;25(2):291. doi: 10.3390/molecules25020291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yuan N., Chen Y., Xia Y., Dai J., Liu C. Inflammation-related biomarkers in major psychiatric disorders: a cross-disorder assessment of reproducibility and specificity in 43 meta-analyses. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):233. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0570-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petralia M.C., Mazzon E., Fagone P., Basile M.S., Lenzo V., Quattropani M.C. The cytokine network in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder. Close to translation? Autoimmun. Rev. 2020:102504. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stuart M.J., Baune B.T. Chemokines and chemokine receptors in mood disorders, schizophrenia, and cognitive impairment: a systematic review of biomarker studies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014;42:93–115. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bergink V., Gibney S.M., Drexhage H.A. Autoimmunity, inflammation, and psychosis: a search for peripheral markers. Biol. Psychiatr. 2014;75(4):324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mané-Damas M., Hoffmann C., Zong S., Tan A., Molenaar P.C., Losen M. Autoimmunity in psychotic disorders. Where we stand, challenges and opportunities. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019;18(9):102348. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2019.102348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Petralia M.C., Mazzon E., Fagone P., Basile M.S., Lenzo V., Quattropani M.C. The cytokine network in the pathogenesis of major depressive disorder. Close to translation? Autoimmun. Rev. 2020;19(5):102504. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2020.102504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benros M.E., Eaton W.W., Mortensen P.B. The epidemiologic evidence linking autoimmune diseases and psychosis. Biol. Psychiatr. 2014;75(4):300–306. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegmann E.-M., Müller H.H.O., Luecke C., Philipsen A., Kornhuber J., Grömer T.W. Association of depression and anxiety disorders with autoimmune thyroiditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psych. 2018;75(6):577–584. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boeschoten R.E., Braamse A.M.J., Beekman A.T.F., Cuijpers P., van Oppen P., Dekker J. Prevalence of depression and anxiety in Multiple Sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017;372:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoang H., Laursen B., Stenager E.N., Stenager E. Psychiatric co-morbidity in multiple sclerosis: the risk of depression and anxiety before and after MS diagnosis. Multiple Sclero. J. 2016;22(3):347–353. doi: 10.1177/1352458515588973. PubMed PMID: 26041803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi S., Studer V., Motta C., Polidoro S., Perugini J., Macchiarulo G. Neuroinflammation drives anxiety and depression in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2017;89(13):1338–1347. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffiths C.E.M., Fava M., Miller A.H., Russell J., Ball S.G., Xu W. Impact of Ixekizumab treatment on depressive symptoms and systemic inflammation in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis: an integrated analysis of three phase 3 clinical studies. Psychother. Psychosom. 2017;86(5):260–267. doi: 10.1159/000479163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dybdal D., Tolstrup J.S., Sildorf S.M., Boisen K.A., Svensson J., Skovgaard A.M. Increasing risk of psychiatric morbidity after childhood onset type 1 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia. 2018;61(4):831–838. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gilsanz P., Karter A.J., Beeri M.S., Quesenberry C.P., Whitmer R.A. The bidirectional association between depression and severe hypoglycemic and hyperglycemic events in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(3):446–452. doi: 10.2337/dc17-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Dooren F.E.P., Nefs G., Schram M.T., Verhey F.R.J., Denollet J., Pouwer F. Depression and risk of mortality in people with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2013;8(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frolkis A.D., Vallerand I.A., Shaheen A.-A., Lowerison M.W., Swain M.G., Barnabe C. Depression increases the risk of inflammatory bowel disease, which may be mitigated by the use of antidepressants in the treatment of depression. Gut. 2019;68(9):1606–1612. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moulton C.D., Pavlidis P., Norton C., Norton S., Pariante C., Hayee B. Depressive symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease: an extraintestinal manifestation of inflammation? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2019;197(3):308–318. doi: 10.1111/cei.13276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roberts A.L., Kubzansky L.D., Malspeis S., Feldman C.H., Costenbader K.H. Association of depression with risk of incident systemic lupus erythematosus in women assessed across 2 decades. JAMA Psych. 2018;75(12):1225–1233. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleming P., Bai J.W., Pratt M., Sibbald C., Lynde C., Gulliver W.P. The prevalence of anxiety in patients with psoriasis: a systematic review of observational studies and clinical trials. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017;31(5):798–807. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sommer I.E., van Westrhenen R., Begemann M.J.H., de Witte L.D., Leucht S., Kahn R.S. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory agents to improve symptoms in patients with schizophrenia: an update. Schizophr. Bull. 2013;40(1):181–191. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Köhler O., Benros M.E., Nordentoft M., Farkouh M.E., Iyengar R.L., Mors O. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psych. 2014;71(12):1381–1391. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sommer I.E., de Witte L., Begemann M., Kahn R.S. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in schizophrenia: ready for practice or a good start? A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatr. 2012;73(4):414–419. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06823. PubMed PMID: 22225599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Quereda C., Corral I., Moreno A., Pérez-Elías M.J., Casado J.L., Dronda F. Effect of treatment with efavirenz on neuropsychiatric adverse events of interferon in HIV/HCV-coinfected patients. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2008;49(1):61–63. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817bbeb9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Balõtšev R., Haring L., Koido K., Leping V., Kriisa K., Zilmer M. Antipsychotic treatment is associated with inflammatory and metabolic biomarkers alterations among first-episode psychosis patients: a 7-month follow-up study. Early Interven. Psych. 2019;13(1):101–109. doi: 10.1111/eip.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Baumeister D., Ciufolini S., Mondelli V. Effects of psychotropic drugs on inflammation: consequence or mediator of therapeutic effects in psychiatric treatment? Psychopharmacology. 2016;233(9):1575–1589. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-4044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang L., Wang R., Liu L., Qiao D., Baldwin D.S., Hou R. Effects of SSRIs on peripheral inflammatory markers in patients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019;79:24–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Moots R., Al-Saffar Z., Hutchinson D., Golding S., Young S., Bacon P. Old drug, new tricks: haloperidol inhibits secretion of proinflammatory cytokines. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 1999;58(9):585–587. doi: 10.1136/ard.58.9.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yamamoto S., Ohta N., Matsumoto A., Horiguchi Y., Koide M., Fujino Y. Haloperidol suppresses NF-kappaB to inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory response in RAW 264 cells. Med. Sci. Mon. 2016;22:367–372. doi: 10.12659/MSM.895739. PubMed PMID: 26842661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Johnson K.V.-A., Foster K.R. Why does the microbiome affect behaviour? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018;1 doi: 10.1038/s41579-018-0014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tucker J.D., Bertke A.S. Assessment of cognitive impairment in HSV-1 positive schizophrenia and bipolar patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2019;209:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown A.S., Cohen P., Harkavy-Friedman J., Babulas V., Malaspina D., Gorman J.M. Prenatal rubella, premorbid abnormalities, and adult schizophrenia. Biol. Psychiatr. 2001;49(6):473–486. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01068-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brown A.S., Schaefer C.A., Quesenberry C.P., Jr., Liu L., Babulas V.P., Susser E.S. Maternal exposure to toxoplasmosis and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2005;162(4):767–773. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mahic M., Mjaaland S., Bøvelstad H.M., Gunnes N., Susser E., Bresnahan M. Maternal immunoreactivity to herpes simplex virus 2 and risk of autism spectrum disorder in male offspring. mSphere. 2017;2(1):e00016–e00017. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00016-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Spann M.N., Sourander A., Surcel H.-M., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki S., Brown A.S. Prenatal toxoplasmosis antibody and childhood autism. Autism Res. 2017;10(5):769–777. doi: 10.1002/aur.1722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doering L.V., Martínez-Maza O., Vredevoe D.L., Cowan M.J. Relation of depression, natural killer cell function, and infections after coronary artery bypass in women. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2008;7(1):52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tenter A.M., Heckeroth A.R., Weiss L.M. Toxoplasma gondii: from animals to humans. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000;30(12):1217–1258. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00124-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cannon M.J., Schmid D.S., Hyde T.B. Review of cytomegalovirus seroprevalence and demographic characteristics associated with infection. Rev. Med. Virol. 2010;20(4):202–213. doi: 10.1002/rmv.655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Carbone K.M. Borna disease virus and human disease. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2001;14(3):513–527. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.3.513-527.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mazaheri-Tehrani E., Maghsoudi N., Shams J., Soori H., Atashi H., Motamedi F. Borna disease virus (BDV) infection in psychiatric patients and healthy controls in Iran. Virol. J. 2014;11(1):161. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Burgdorf K.S., Trabjerg B.B., Pedersen M.G., Nissen J., Banasik K., Pedersen O.B. Large-scale study of Toxoplasma and Cytomegalovirus shows an association between infection and serious psychiatric disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sutterland A.L., Fond G., Kuin A., Koeter M.W.J., Lutter R., van Gool T. Beyond the association. Toxoplasma gondii in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and addiction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2015;132(3):161–179. doi: 10.1111/acps.12423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Arias I., Sorlozano A., Villegas E., Luna JdD., McKenney K., Cervilla J. Infectious agents associated with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr. Res. 2012;136(1):128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.de Barros J.L.V.M., Barbosa I.G., Salem H., Rocha N.P., Kummer A., Okusaga O.O. Is there any association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and bipolar disorder? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2017;209:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Snijders G.J., van Mierlo H.C., Boks M.P., Begemann M.J., Sutterland A.L., Litjens M. The association between antibodies to neurotropic pathogens and bipolar disorder. Transl. Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0636-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nayeri T., Sarvi S., Moosazadeh M., Hosseininejad Z., Amouei A., Daryani A. Toxoplasma gondii infection and risk of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pathog. Glob. Health. 2020;114(3):117–126. doi: 10.1080/20477724.2020.1738153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chegeni T.N., Sharif M., Sarvi S., Moosazadeh M., Montazeri M., Aghayan S.A. Is there any association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2019;14(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0218524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Flegr J., Horáček J. Toxoplasma-infected subjects report an Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder diagnosis more often and score higher in Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory. Eur. Psychiatr. 2017;40:82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sutterland A.L., Kuin A., Kuiper B., van Gool T., Leboyer M., Fond G. Driving us mad: the association of Toxoplasma gondii with suicide attempts and traffic accidents – a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019;49(10):1608–1623. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719000813. Epub 2019/04/23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Frye M.A., Coombes B.J., McElroy S.L., Jones-Brando L., Bond D.J., Veldic M. Association of cytomegalovirus and Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers with bipolar disorder. JAMA Psych. 2019;76(12):1285–1293. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Slawinski B.L., Talge N., Ingersoll B., Smith A., Glazier A., Kerver J. Maternal cytomegalovirus sero-positivity and autism symptoms in children. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2018;79(5) doi: 10.1111/aji.12840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Khanna S., Ravi V., Shenoy P.K., Chandramuki A., Channabasavanna S.M. Cerebrospinal fluid viral antibodies in obsessive compulsive disorder in an indian population. Biol. Psychiatr. 1997;41(8):883–890. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zappulo E., Riccio M.P., Binda S., Pellegrinelli L., Pregliasco F., Buonomo A.R. Prevalence of HSV1/2 congenital infection assessed through genome detection on dried blood spot in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Vivo. 2018;32(5):1255–1258. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mora M., Quintero L., Cardenas R., Suarez-Roca H., Zavala M., Montiel N. Association between HSV-2 infection and serum anti-rat brain antibodies in patients with autism. Invest. Clin. 2009;50(3):315–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gale S.D., Berrett A.N., Erickson L.D., Brown B.L., Hedges D.W. Association between virus exposure and depression in US adults. Psychiatr. Res. 2018;261:73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Simanek A.M., Cheng C., Yolken R., Uddin M., Galea S., Aiello A.E. Herpesviruses, inflammatory markers and incident depression in a longitudinal study of Detroit residents. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;50:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Brown A.S., Cohen P., Greenwald S., Susser E. Nonaffective psychosis after prenatal exposure to rubella. Am. J. Psychiatr. 2000;157(3):438–443. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hutton J. Does rubella cause autism: a 2015 reappraisal? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016;10(25) doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2016.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brown A.S., Begg M.D., Gravenstein S., Schaefer C.A., Wyatt R.J., Bresnahan M. Serologic evidence of prenatal influenza in the etiology of schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 2004;61(8):774–780. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Parboosing R., Bao Y., Shen L., Schaefer C.A., Brown A.S. Gestational influenza and bipolar disorder in adult offspring. JAMA Psych. 2013;70(7):677–685. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Okusaga O., Yolken R.H., Langenberg P., Lapidus M., Arling T.A., Dickerson F.B. Association of seropositivity for influenza and coronaviruses with history of mood disorders and suicide attempts. J. Affect. Disord. 2011;130(1):220–225. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fu Z.F., Amsterdam J.D., Kao M., Sharikar V., Koprowski H., Dietzschold B. Detection of borna disease virus-reactive antibodies from patients with affective disorders by western immunoblot technique. J. Affect. Disord. 1993;27(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Bode L., Dürrwald R., Rantam F., Ferszt R., Ludwig H. First isolates of infectious human Borna disease virus from patients with mood disorders. Mol. Psychiatr. 1996;1(3):200–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Amsterdam J.D., Winokur A., Dyson W., Herzog S., Gonzalez F., Rott R. Borna disease virus: a possible etiologic factor in human affective disorders? Arch. Gen. Psychiatr. 1985;42(11):1093–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790340077011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nicolson G.L., Gan R., Nicolson N.L., Haier J. Evidence for Mycoplasma ssp., Chlamydia pneunomiae, and human herpes virus-6 coinfections in the blood of patients with autistic spectrum disorders. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85(5):1143–1148. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ambigapathy G., Schmit T., Mathur R.K., Nookala S., Bahri S., Pirofski L-a. Double-edged role of interleukin 17A in Streptococcus pneumoniae pathogenesis during influenza virus coinfection. J. Infect. Dis. 2019;220(5):902–912. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiz193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shmagel K., Saidakova E., Shmagel N., Korolevskaya L., Chereshnev V., Robinson J. Systemic inflammation and liver damage in HIV/hepatitis C virus coinfection. HIV Med. 2016;17(8):581–589. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Aibibula W., Cox J., Hamelin A.-M., Moodie E.E., Anema A., Klein M.B. Association between depressive symptoms, CD4 count and HIV viral suppression among HIV-HCV co-infected people. AIDS Care. 2018;30(5):643–649. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1431385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fialho R., Pereira M., Harrison N., Rusted J., Whale R. Co-infection with HIV associated with reduced vulnerability to symptoms of depression during antiviral treatment for hepatitis C. Psychiatr. Res. 2017;253:150–157. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Clifford D.B., Evans S.R., Yang Y., Gulick R.M. The neuropsychological and neurological impact of hepatitis C virus co-infection in HIV-infected subjects. Aids. 2005;19:S64–S71. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192072.80572.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.