Abstract

Dopamine is an important neurotransmitter that plays a key role in a wide range of both locomotive and cognitive functions in humans. Disturbances on the dopaminergic system cause, among others, psychosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Antipsychotics are drugs that interact primarily with the dopamine receptors and are thus important for the control of psychosis and related disorders. These drugs function as agonists or antagonists and are classified as such in the literature. However, there is still much to learn about the underlying mechanism of action of these drugs. The goal of this investigation is to analyze the intrinsic chemical reactivity, more specifically, the electron donor–acceptor capacity of 217 molecules used as dopaminergic substances, particularly focusing on drugs used to treat psychosis. We analyzed 86 molecules categorized as agonists and 131 molecules classified as antagonists, applying Density Functional Theory calculations. Results show that most of the agonists are electron donors, as is dopamine, whereas most of the antagonists are electron acceptors. Therefore, a new characterization based on the electron transfer capacity is proposed in this study. This new classification can guide the clinical decision-making process based on the physiopathological knowledge of the dopaminergic diseases.

Subject terms: Biophysical chemistry, Biochemistry, Biophysics, Neuroscience, Medical research, Chemistry, Physics

Introduction

During the second half of the last century, a movement referred to as the third revolution in psychiatry emerged, directly related to the development of new antipsychotic drugs for the treatment of psychosis. Treatment of psychosis has evolved with the development of antipsychotic drugs. The dopamine hypothesis, which defines the physiological mechanism of schizophrenia (a type of psychosis) postulates that this is derived from a primary imbalance in the dopaminergic system1–44. Currently, there are at least eleven different types of dopaminergic drugs for the control of psychotic symptoms. To date, all drugs with antipsychotic efficacy show some affinity and activity at the D2 subtype of the dopamine receptor36.

Research focusing on new antipsychotics has led to greater knowledge on their biochemical effects; however, the physiological mechanism of action underlying their pharmacological therapy still requires explanation. For the most part, antipsychotics can be classified as antagonists or agonists, according to their functionality. Antagonist drugs are those that bind to receptors, in this case dopamine receptors and block them, while agonist drugs are those that interact with the receptors, thereby activating them. An agonist produces a conformational change in the dopamine receptors (coupled to a G-protein) that turns on the synthesis of a second messenger. Antagonists also produce a conformational change in the receptor but without change in signal transduction.

Experimentally, drugs are classified as either agonists or antagonists based on complex behavioral analysis, as well as rotational experiments with rats25,38,39. In addition to agonist–antagonist classification, antipsychotics have been classified according to having affinity for more than one receptor subtype, leading to first and second-generation of antipsychotics40.

Previous reports45–47 have used quantum chemistry calculations to help describe the pharmacodynamics of antipsychotic drugs, relating biological activity to chemical reactivity indices, such as chemical hardness and first ionization energy. There is also a comparative study of 32 oral antipsychotics used for treatment of schizophrenia (3 partial agonists and 29 antagonists) recently published48. Authors report specific aspects for the antipsychotics such as efficacy, quality of life and side effects. They conclude that, because so many antipsychotics options are available, this analysis should help to find the most suitable drug for each patient. They also found efficacy differences between molecules, but drugs differ more in their side effects than in the effectiveness. It is clear that more research is needed to explain the psychopharmacodynamic effect these drugs have.

In spite of all existing research on dopaminergic agents, to date, very little empirical and theoretical data exist to elucidate mechanisms of action. Based on the idea that all molecules have chemical properties that can be described in terms of response functions related to chemical reactivity, the principal aim of this investigation is to examine 86 molecules classified as agonists and 131 molecules classified as antagonists (Tables 1, 2) by applying Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. We analyzed electron transfer capacity as a response function, because it can be related to the pharmacodynamics of the molecules that control electrochemical signaling in cells, a function which is imbalanced during e.g. psychosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. The aim of the study is to explore the intrinsic properties of D2 ligands without the receptor, in an effort to predict some of their inherent characteristics prior to any biological interactions. We hypothesize that the dichotomy behavior of electron donation or acceptance provides an interesting and more precise way to classify ligands than the conventional agonist/antagonist biological profile.

Table 1.

Conventional classification of dopaminergic agents that are agonists reported in alphabetical order.

| 5OH-DPAT | Bifeprunox | Dihydroergocryptine | Lisuride | Quinpirole |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6Br-APB | (R)-Boldine | Dihydroergotamine | Mesulergine | RDS127 |

| 7OH-DPAT | (S)-Boldine | Dinapsoline | Methylphenidate | RO105824 |

| 7OH-PIPAT | Blonanserin | Ergocornine | Minaprine | Ropinirole |

| 8OH-DPAT | Brexpiprazole | α-Ergocryptine | (R)-Nuciferine | Rotigotine |

| A412997 | Brasofensine | β-Ergocryptine | OSU6162 | SKF38393 |

| A77636 | Brilaroxazine | α-Ergosine | PD128907 | SKF77434 |

| A86929 | Bromocryptine | β-Ergosine | PD168077 | SKF81297 |

| ACP104 | (R)-Bulbocapnine | Ergometrine | Pergolide | SKF82958 |

| Alentemol | (S)-Bulbocapnine | Ergotamine | PF216061 | SKF83959 |

| (S)-Amphetamine | Cabergoline | Epicryptine | PF592379 | SKF89145 |

| Aplindore | Cariprazine | Fenoldopam | Pardoprunox | Stepholidine |

| (R)-Apomorphine | Chanoclavine I | Flibanserin | Piribedil | Sumanirole |

| (S)-Apomorphine | cis8-OH-PBZI | (R)-Glaucine | Pramipexole | Talipexole |

| (R)-Aporphine | Dihydrexidine | (S)-Glaucine | (R)-Pukateine | Trepipam |

| (S)-Aporphine | Dihydroergocornine | Hordenine | Quinagolide | Vilazodone |

| Aripiprazole | Dihydroergocristine | Lergotrile | Quinelorane | Zelandopam |

| Bicifadine |

Table 2.

Conventional classification of dopaminergic agents that are antagonists, reported in alphabetical order.

| Abaperidone | Cisapride | Imipramine | Olanzapine | Sertindole |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aceperone | Clebopride | Itopride | Paliperidone | Setoperone |

| Acepromazine | Cloroperone | Lenperone | Pentiapine | S142907 |

| Acetophenazine | Clotiapine | Levomepromazine | Perphenazine | SCH23390 |

| Alizapride | Clozapine | Lodiperone | Perospirone | Spiperone |

| Amiperone | Cyclindole | Loxapine | Pimavanserin | Spiroxatrine |

| Amisulpride | Declenperone | Lumateperone | Pimethixene | Sulpiride |

| Amoxapine | Desipramine | Lurasidone | Pimozide | Tefluthizol |

| Aptazapine | Diethazine | Mafoprazine | Pipamperone | Tenilapine |

| Asenapine | Dixyrazine | Mazapertine | Pipothiazine | Tetrabenazine |

| Azabuperone | Domperidone | Melperone | Prideperone | Thiethylperazine |

| Azaperone | Dothiepin | Mequitazine | Primaperone | Thioridazine |

| Batanopride | Droperidol | Mesoridazine | Proclorperazine | Thiothixene |

| Benperidol | Ecopipam | Metoclopramide | Promethazine | Tiapride |

| Biriperone | Enciprazine | Metopimazine | Propiomazine | Timiperone |

| BL1020 | Etoperidone | Metrenperone | Propyperone | Tiospirone |

| Bromopride | Fananserin | Mindoperone | Quetiapine | Trifluoperazine |

| Bromperidol | Flucindole | Mirtazapine | Raclopride | Trifluperidol |

| Buspirone | Fluphenazine | Molindone | Remoxipride | UH232 |

| Carperone | Flumezapine | Moperone | Renzapride | Veralipride |

| Carphenazine | Flupenthixol | Mosapride | Rilapine | Yohimbine |

| Chlorpromazine | Fluperlapine | Nafadotride | Risperidone | Zacopride |

| Chlorprothixene | Gevotroline | Nemonapride | Roxindole | Zetidoline |

| Cicarperone | Haloperidol | Nonaperone | Roxoperone | Zicronapine |

| Cinitapride | Homopipramol | Nortriptyline | Sarizotan | Ziprasidone |

| Cinuperone | Iloperidone | Ocaperidone | Seridopidine | Zoloperone |

| Zuclopenthixol |

Results

The hypothesis underlying our investigation is that agonist molecules have electron transfer properties similar to those of dopamine; whereas antagonists of dopamine have a different capacity to transfer charge. At molecular level, this may explain why antagonists bind to the receptors without activating them.

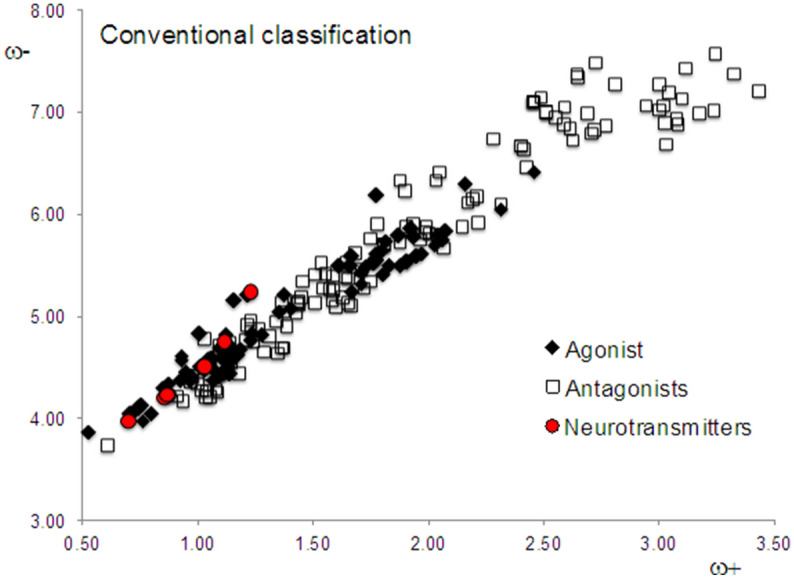

DAM of all studied compounds

We calculated the electrodonating and electroaccepting powers (ω− and ω+) of the endogenous neurotransmitter dopamine and the related compounds dopexamine, epinine, etilevodopa, ibopamine, levodopa and melevodopa, as well as dopaminergic ligands and closely related substances (86 agonists and 131 antagonists) in order to analyze their electron transfer properties. Dopamine and related compounds are calculated in order to compare their electron transfer properties with that of the pharmaceuticals studied (Table 3). The results are described in Fig. 1, where we present the DAM of all ligands including the neurotransmitter group. Black squares represent so-called agonists, whereas white squares represent antagonists (see Tables 1, 2). Evidently, there is no clear difference between these two and it is apparent that there are many exceptions to our hypothesis. There are several agonists that are not as good electron donors as dopamine and contrarily, there are many antagonists that have similar electron donor properties to dopamine.

Table 3.

Data of neurotransmitter dopamine and related compounds are reported.

| Name | ω+ | ω− | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | 0.87 | 4.23 | Endogenous agonist at dopamine receptor subtypes D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 receptors |

| Dopexamine | 0.86 | 4.20 | D2 full agonist |

| Epinine | 0.87 | 4.23 | Dopaminergic agonist |

| Etilevodopa | 4.50 | 1.03 | Prodrug of dopamine |

| Ibopamine | 5.24 | 1.23 | Prodrug of dopamine |

| Levodopa | 0.70 | 3.96 | Precursor of dopamine |

| Melevodopa | 1.12 | 4.75 | Prodrug of dopamine |

Figure 1.

DAM of all the studied compounds. Neurotransmitters are a reference group that includes dopamine and derivatives of dopamine with pharmacological related activity.

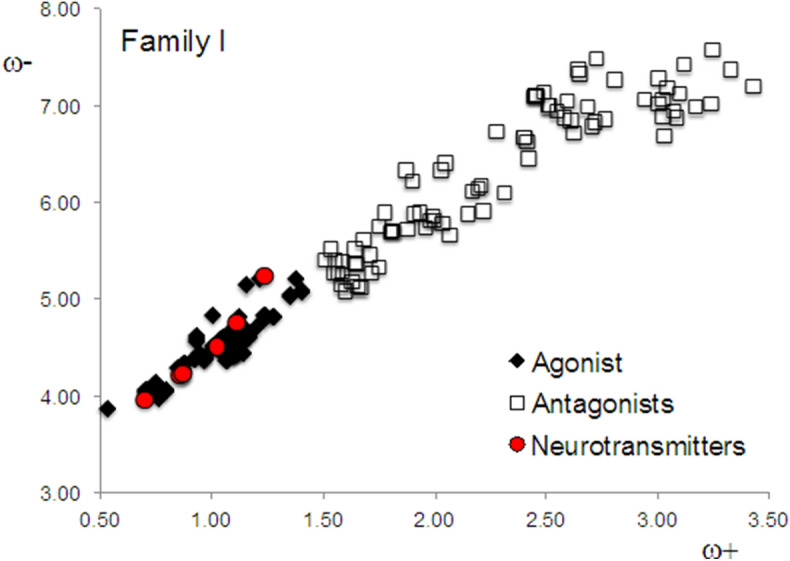

Family I of compounds

Analyzing the information available concerning the characteristics of these drugs, it turns out that certain molecules are neither exclusively agonists nor exclusively antagonists of D2 dopamine (complete list of references are given in Supplementary Information). They bind to multiple receptors or they are used as antidepressants, or they can act as either agonists and/or antagonists, depending on dosage. In order to analyze these results more carefully, we divided the system into two new families. Family I consists of those dopamine receptor ligands that can be easily characterized as either agonists or antagonists, and mainly bind to the D2 receptor of dopamine. In this family, there are 54 molecules classified as agonists and 88 molecules classified as antagonists. The DAM of Family I is reported in Fig. 2 and evidently the ordering is impressive. Apparently, these agonists have values of ω+ that are lower or equal to 1.5 and the antagonists of this family have values of ω+ higher than 1.5. All agonists are close to dopamine and the neurotransmitter group, and they are also better electron donors than the antagonists. Antagonists are good electron acceptors in contrast to dopamine, which is a good electron donor. Taking this set of molecules, we can conclude that agonists have similar electron transfer capacity to dopamine, whereas antagonists differ from dopamine in this sense.

Figure 2.

DAM of Family I.

Family II of compounds

Family II comprises 76 molecules that are reported as “partial” or “weak” agonists or antagonists, and some of them present binding affinity for multiple receptors. Regardless of whether they are reported as “weak” or “partial” agonists/antagonists, these molecules were included in the conventional classification of agonists/antagonists with antiparkinsonian or antipsychotic effects. Family II form a group that is heterogeneous, with molecules that have affinity for multiple receptors and they are also weak or partial agonists or antagonists. They do not present selectivity to dopamine receptors.

The DAM of Family II is included in Fig. 3. Surprisingly, the tendency is inverted, i.e. antagonists have similar electron donor properties to dopamine, whereas agonists have different electron donor properties. It is important to emphasize that previously reported experimental data concerning the reactivity of these molecules is either imprecise or indicates that these molecules bind to multiple receptors. The inverse association found in Family II is difficult to explain, but may be an indication of the complications related to the experimental classification of these drugs. The inherent uncertainty associated with the ex vivo or in vivo experiments is a non-parametric entity that is composed of at least two levels of contributions: the supramolecular and the organellar-cellular. The supramolecular contribution of that uncertainty is related to the lack of abstraction, or “isolation”, of the modeled system being studied (i.e., interference from other proteins that interact with the receptor, presence of some ligands, significant changes to membrane composition, etcetera). The organellar-cellular contribution of this uncertainty is a “background-noise-like" factor, related to variation in the post-translational modifications of proteins, assimilation of the response signals by several cellular components, termination of these signals by natural mechanisms, among others.

Figure 3.

DAM of Family II.

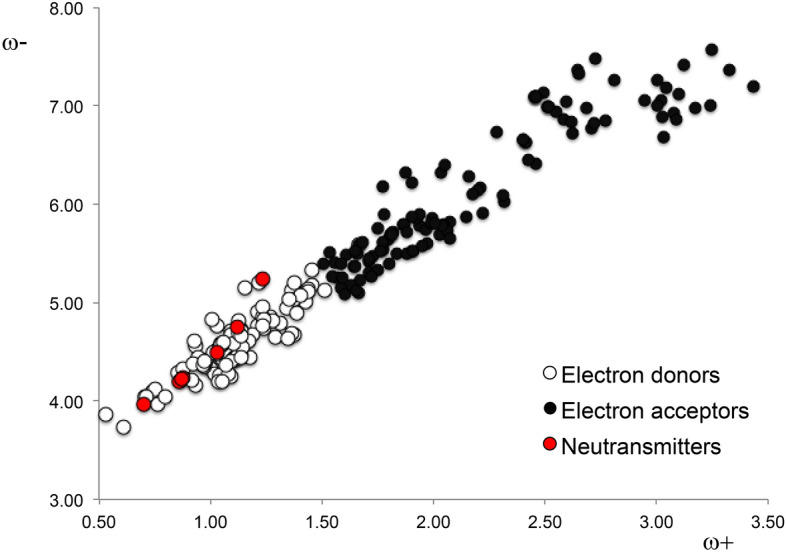

Discussion

Importantly, behavioral experiments undertaken with rats manifest a degree of ambiguity, inherent to the complexity of biological systems and also to the evaluation and interpretation of data. This degree of ambiguity is not present in quantum chemistry calculations. The hypothesis here is that drugs with electron-transfer properties similar to neurotransmitters will also manifest similar action mechanisms. We thus report new information about the electron donor–acceptor properties of the molecules. This new information is presented in Tables 4 and 5 with specific order. The dopamine receptor ligands with ω+ values below or equal to 1.5 are electron donors and those with ω+ values greater than 1.5 are electron acceptors. This new information generated the DAM reported in Fig. 4. We also included neurotransmitter-related molecules that constitute good electron donors (Table 3). The value of 1.5 for ω+ is arbitrary, but this number emerges when we consider experimental information related to the characterization of agonists and antagonists. Within this range, experimental information concurs with theoretical values because all adequately characterized agonists present ω+ values that are less or equal to 1.5, and all adequately characterized antagonists manifest values that exceed a ω+ value of 1.5. This enabled us to classify the molecules with reference to reported experimental and theoretical information.

Table 4.

Pharmaceuticals with electron donor properties (ω+ < 1.5) similar to dopamine and related neurotransmitters, presented in alphabetical order.

| Name | ω+ | ω− | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-OH-DPAT | 0.74 | 4.10 | D2 and D3 receptor full agonist |

| 6-Br-APB | 1.05 | 4.58 | D1 full agonist |

| 7-OH-DPAT | 1.03 | 4.52 | Selective D3 full agonist |

| 7-OH-PIPAT | 1.04 | 4.53 | Selective D3 full agonist |

| A-412997 | 1.38 | 5.20 | Selective D4 full agonist |

| A-77636 | 0.75 | 4.12 | Selective D1 full agonist |

| A-86929 | 1.16 | 4.63 | D1, D2 and D5 full agonist |

| Amfetamine | 1.00 | 4.82 | Dopaminergic stimulant, agonist-binding |

| Aplindore | 1.07 | 4.47 | Partial D2 agonist |

| Aptazapine | 1.00 | 4.33 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Aripiprazole | 1.03 | 4.48 | D2 partial agonist |

| Asenapine | 1.03 | 4.77 | D1, D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Batanopride | 1.34 | 4.95 | D2 antagonist |

| BL-1020 | 1.38 | 4.68 | D2 antagonist |

| Blonanserin | 1.28 | 4.81 | D2 and D3 antagonist |

| Brasofensine | 1.21 | 5.2 | Antidepressant |

| Brilaroxazine | 1.19 | 4.67 | D2, D3 and D4 partial agonist |

| Bromopride | 1.45 | 5.18 | D2 antagonist |

| Cabergoline | 1.12 | 4.46 | D1 and D5 full agonist and D2, D3 and D4 partial agonist |

| Cariprazine | 1.24 | 4.83 | D2 and D3 partial agonist |

| Chanoclavine I | 1.11 | 4.43 | Dopamine agonist |

| Chlorpromazine | 1.37 | 4.69 | D1, D2, D3 and D5 antagonist |

| cis8-OH-PBZI | 1.05 | 4.57 | D3 selective full agonist |

| Cyclindole | 1.02 | 4.27 | D2 antagonist |

| Desipramine | 1.09 | 4.64 | Antidepressant |

| Diethazine | 1.18 | 4.44 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Dihydrexidine | 1.17 | 4.62 | D1 and D2 agonist |

| Dihydroergocornine | 1.10 | 4.43 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Dihydroergocristine | 1.11 | 4.43 | Dopamine partial agonist |

| Dihydroergocryptine | 1.11 | 4.45 | D2 full agonist and D1 and D3 partial agonist |

| Dihydroergotamine | 1.12 | 4.45 | Dopaminergic ligand |

| Dinapsoline | 1.11 | 4.62 | Selective D5 full agonist |

| Dixyrazine | 1.04 | 4.26 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Dosulepin | 1.43 | 5.02 | Antidepressant |

| Ecopipam | 1.21 | 4.91 | D1 and D5 antagonist |

| Enciprazine | 0.61 | 3.73 | Antipsychotic and anxiolytic |

| Epicriptine | 1.09 | 4.41 | D2 full agonist and D1 and D3 partial agonist |

| Etoperidone | 1.14 | 4.73 | Weak dopamine antagonist |

| Fenoldopam | 1.14 | 4.71 | Selective D1 and D5 full agonist |

| Flibanserin | 1.40 | 5.08 | Selective D4 partial agonist |

| Flucindole | 1.10 | 4.51 | D2 antagonist |

| Gevotroline | 1.24 | 4.75 | D2 antagonist |

| Hordenine | 0.71 | 4.05 | D2 agonist |

| Imipramine | 0.94 | 4.17 | Antidepressant |

| Lergotrile | 1.14 | 4.55 | Dopamine agonist |

| Levomepromazine | 1.09 | 4.25 | D2 antagonist |

| Lodiperone | 1.43 | 5.12 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Mafoprazine | 0.97 | 4.35 | D2 antagonist |

| Mazapertine | 1.51 | 5.12 | D2 antagonist |

| Mequitazine | 1.08 | 4.27 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Mesulergine | 1.14 | 4.44 | D2 partial agonist |

| Methylphenidate | 1.15 | 5.15 | D2 ligand |

| Metoclopramide | 1.27 | 4.86 | D2 antagonist |

| Mirtazapine | 1.31 | 4.80 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Nortriptyline | 1.37 | 5.13 | Antidepressant |

| Pardoprunox | 0.95 | 4.44 | D2 and D3 partial agonist |

| PD-128,907 | 1.23 | 4.76 | An experimental, selective D2 and D3 agonist |

| Perfenazine | 1.29 | 4.65 | D2 antagonist |

| Pergolide | 1.07 | 4.37 | Dopaminergic full agonist |

| PF-219061 | 1.12 | 4.82 | Selective D3 agonist |

| PF-592379 | 1.35 | 5.04 | Selective D3 agonist |

| Pimozide | 0.98 | 4.41 | D2 and D3 antagonist |

| Pramipexole | 0.77 | 3.97 | D2, D3 and D4 full agonist |

| Prochlorperazine | 1.35 | 4.63 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Promethazine | 1.14 | 4.47 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Quinagolide | 0.88 | 4.32 | D1 and D2 full agonist |

| Quinpirole | 0.53 | 3.87 | D2 and D3 full agonist |

| RDS-127 | 0.92 | 4.38 | Selective D2 agonist |

| Remoxipride | 1.46 | 5.33 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Ropinirole | 1.09 | 4.68 | D2, D3 and D4 agonist |

| Rotigotine | 0.71 | 4.04 | D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 agonist |

| S-14297 | 1.05 | 4.44 | Dopamine antagonist |

| SCH-23390 | 1.23 | 4.96 | Selective D1 and D5 antagonist |

| Sertindole | 1.39 | 4.90 | D2 antagonist |

| SKF-38393 | 1.10 | 4.58 | D1 and D5 partial agonist |

| SKF-77434 | 0.97 | 4.38 | D1 partial agonist |

| SKF-81297 | 1.12 | 4.69 | D1 full agonist |

| SKF-82958 | 1.05 | 4.58 | A D1 full agonist |

| SKF-83959 | 1.06 | 4.59 | D1 full agonist |

| SKF-89145 | 1.14 | 4.67 | Selective D1 agonist |

| Spiroxatrine | 0.92 | 4.21 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Stepholidine | 0.97 | 4.37 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Sumanirole | 1.01 | 4.50 | Selective D2 full agonist |

| Talipexole | 0.80 | 4.04 | D2, D3 and D4 full agonist |

| Thiethylperazine | 1.05 | 4.20 | D1, D2 and D4 antagonist |

| Thioridazine | 1.03 | 4.20 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Trepipam | 0.93 | 4.61 | D1 agonist |

| Yohimbine | 1.14 | 4.54 | D2 and D3 antagonist |

| Zelandopam | 0.97 | 4.41 | A selective D1 agonist |

| Zetidoline | 1.09 | 4.71 | D2 antagonist |

| Zoloperone | 1.44 | 5.11 | Very weak dopamine antagonist |

Table 5.

Pharmaceuticals with electron acceptor properties (ω+ > 1.5), presented in alphabetical order.

| Name | ω+ | ω− | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abaperidone | 2.55 | 6.94 | D2 antagonist |

| Aceperone | 2.51 | 6.99 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Acepromazine | 3.17 | 6.97 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Acetophenazine | 3.24 | 7.00 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Alentemol | 1.83 | 5.49 | Selective D2S agonist |

| Alizapride | 2.59 | 6.87 | D2 antagonist |

| Amiperone | 2.60 | 7.04 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Amisulpride | 1.56 | 5.41 | D2S, D2L and D3 antagonist |

| Amoxapine | 2.21 | 6.17 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Apomorphine | 1.77 | 5.55 | D1 and D2 full agonist |

| Aporphine | 1.86 | 5.79 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Azabuperone | 3.12 | 7.42 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Azaperone | 3.04 | 7.19 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Benperidol | 2.71 | 6.78 | D2 antagonist |

| Bifeprunox | 1.66 | 5.50 | Weak D2 partial agonist |

| Biriperone | 3.08 | 6.93 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Boldine | 1.71 | 5.31 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Brexpiprazole | 2.32 | 6.03 | D2 partial agonist |

| Bromocryptine | 2.04 | 5.79 | D1, D2, D3 and D5 agonist and D4 antagonist |

| Bromperidol | 2.51 | 6.99 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Bulbocapnine | 1.73 | 5.47 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Buspirone | 1.75 | 5.75 | Weak D2 antagonist |

| Carperone | 2.64 | 7.37 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Carphenazine | 3.09 | 6.87 | D1, D2 and D5 antagonist |

| Chlorprothixene | 1.96 | 5.74 | D1, D2, D3 antagonist |

| Cicarperone | 2.73 | 7.48 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Cinuperone | 2.31 | 6.09 | D2 antagonist |

| Cloroperone | 2.65 | 7.33 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Clotiapine | 1.99 | 5.86 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Clozapine | 2.04 | 5.79 | D1, D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Declenperone | 2.77 | 6.86 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Droperidol | 2.72 | 6.82 | D2 antagonist |

| Ergocornine | 2.03 | 5.69 | Dopamine agonist |

| α-Ergocryptine | 1.97 | 5.61 | Dopamine agonist |

| β-Ergocryptine | 1.88 | 5.49 | Dopamine agonist |

| Ergometrine | 1.95 | 5.58 | Dopamine agonist |

| α-Ergosine | 1.90 | 5.53 | Dopamine agonist |

| β-Ergosine | 1.91 | 5.53 | Dopamine agonist |

| Ergotamine | 2.06 | 5.74 | Dopamine agonist |

| Fananserin | 2.94 | 7.06 | D4 antagonist |

| Flufenazine | 1.67 | 5.11 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Flumezapine | 1.75 | 5.33 | Dopamine agonist |

| Flupenthixol | 1.99 | 5.81 | D1 and D2, antagonist |

| Fluperlapine | 1.71 | 5.45 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Glaucine | 1.8 | 5.64 | D1 and D5 antagonist |

| Haloperidol | 2.51 | 6.99 | D1 and D2 antagonist and a D3 and D4 inverse agonist |

| Homopipramol | 5.87 | 2.15 | Antidepressant with some antipsychotic effects |

| Iloperidone | 2.40 | 6.66 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Lenperone | 2.49 | 7.14 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Lisuride | 1.80 | 5.40 | D2, D3 and D4 full agonist, and D1 and D5 antagonist |

| Loxapine | 2.20 | 6.14 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Lumateperone | 3.03 | 6.68 | D2S and D2L partial agonist |

| Lurasidone | 1.81 | 5.69 | D2 antagonist |

| Melperone | 2.46 | 7.10 | D2 antagonist |

| Mesoridazine | 1.63 | 5.17 | D2 antagonist |

| Metopimazine | 2.22 | 5.90 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Metrenperone | 2.63 | 6.72 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Minaprine | 1.93 | 5.85 | D1 and D2 agonist |

| Moperone | 2.81 | 7.26 | A D2 antagonist |

| Nafadotride | 3.01 | 7.27 | D3 and D2 antagonist |

| Nemonapride | 1.59 | 5.25 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Nonaperone | 2.45 | 7.09 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Norclozapine | 2.08 | 5.83 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Nuciferine | 1.82 | 5.72 | Dopamine weak antagonist |

| Ocaperidone | 2.43 | 6.45 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Olanzapine | 1.72 | 5.27 | D1, D2, D3, D4 and D5 antagonist |

| OSU-6162 | 1.77 | 6.19 | D2 partial agonist |

| Paliperidone | 1.78 | 5.89 | D1, D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| PD-168,077 | 2.16 | 6.28 | Selective D4 full agonist |

| Pentiapine | 1.68 | 5.61 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Perospirone | 1.81 | 5.70 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Pimethixene | 1.65 | 5.36 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Pipamperone | 2.62 | 6.83 | D4 and D2 antagonist |

| Pipotiazine | 2.07 | 5.65 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Piribedil | 1.77 | 5.61 | D2 and D3 agonist |

| Prideperone | 2.03 | 6.33 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Primaperone | 2.46 | 7.10 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Propiomazine | 3.03 | 6.88 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Propyperone | 3.33 | 7.37 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Pukateine | 1.76 | 5.52 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Quetiapine | 1.88 | 5.72 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Quinelorane | 1.66 | 5.58 | D2 and D3 agonist |

| Raclopride | 2.40 | 6.66 | D2 and D3 antagonist |

| Rilapine | 3.02 | 7.06 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Risperidone | 1.54 | 5.51 | D1, D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Ro10-5824 | 1.61 | 5.49 | Selective D4 partial agonist |

| Roxindole | 1.6 | 5.09 | D2S, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Roxoperone | 2.45 | 7.09 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Sarizotan | 1.94 | 5.89 | D2 antagonist |

| Setoperone | 2.69 | 6.98 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Spiperone | 3.00 | 7.01 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Sulpiride | 2.05 | 6.40 | D2 and D3 antagonist |

| Tefluthixol | 1.59 | 5.39 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Tenilapine | 3.25 | 7.57 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Tetrabenazine | 1.65 | 5.52 | D2 ligand |

| Thiothixene | 2.18 | 6.10 | D1 and D2 antagonist |

| Tiapride | 1.90 | 6.22 | D2 and D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Timiperone | 3.10 | 7.12 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Tiospirone | 1.81 | 5.70 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Trifluoperazine | 1.66 | 5.12 | D2 antagonist |

| Trifluperidol | 2.46 | 7.10 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| UH-232 | 1.91 | 5.88 | D2 antagonist and D3 partial agonist |

| Veralipride | 2.28 | 6.73 | Dopamine antagonist |

| Vilazodone | 2.46 | 6.41 | D2 weak agonist |

| Ziprasidone | 1.81 | 5.70 | D2, D3 and D4 antagonist |

| Zuclopenthixol | 2.00 | 5.81 | D1, D2 and D5 antagonist |

Figure 4.

DAM of all compounds considering the information of Tables 4 and 5.

One purpose of antipsychotic treatment is to minimize schizophrenia symptoms, which are caused by a deep imbalance in the dopaminergic system. Reported physiological mechanisms of schizophrenia demonstrate an excess of dopamine activity (direct or indirect) in certain regions of the brain, and little dopamine activity in other regions. We use our information to postulate that electron donors could be useful for modulating schizophrenia symptoms related to little dopamine activity as well as Parkinson’s disease and electron acceptors may be useful for controlling psychosis associated with an excess of dopamine activity as well as Huntington’s disease. Our findings indicate that electron acceptors bind to dopamine receptors and block or inactivate them. Contrarily, agonists interact and donate electrons, thus activating the receptor in a similar way to dopamine.

The drugs reported here were classified in the literature as agonists or antagonists. Additionally, electrochemical signaling in cells is an essential process in humans, indicating that electron transfer may be related to the functionality of the molecules that control psychosis. Our results agree with this theory and thus, it is in accordance with the currently believed molecular action mechanism of these drugs. Therefore, we corroborate previously reported postulations with quantum chemistry calculations, and also propose new information for this group of antipsychotic drugs.

The main idea of this investigation was to compare intrinsic properties (electron donor–acceptor) between the drugs and neurotransmitters. These intrinsic properties of the molecules are not always in agreement with the conventional classification of agonists and antagonists, specifically for those molecules of Family II that are classified experimentally as “partial” or “weak” agonists/antagonists. The new information reported in this study permits us to define these molecules as "similar to" or "different from" the neurotransmitters.

The design of drugs for specific treatments is very demanding. After chemical synthesis and all characterizations have been accomplished, it is necessary to carry out biological tests on the drugs to determine their efficacy, and also in this specific case to define whether they are conventional agonists or antagonists of dopamine or other neurotransmitters. There are many dopaminergic agents available, which vary in terms of effectiveness and side effects, and no single treatment works for all patients. When it is necessary to change medications for specific patients, it is no easy task to decide which medication will help control symptoms. The perception that emerges from this dilemma is that along with the experimental determinations and biological tests, it is possible to do quantum chemical calculations on the molecules in order to obtain more information about their inherent reactivity and susceptibility for binding to receptors. All this information together, including the comparison of these intrinsic chemical properties, should help medical doctors define the most suitable medication for each individual patient.

Notably, in this analysis we do not include dopamine receptors in the form of G-Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs). This is because the principal aim of this investigation was to report information of the dopaminergic agents based on theoretical Density Functional Theory response functions, related to the electron transfer process. Previously45 it was reported that drugs are like light bulbs and receptors (GPCR proteins) resemble the sockets of a light bulb. Certain light bulb characteristics are independent of the sockets (for example, light bulbs can have different colors or voltage); in the same way that electron transfer properties of dopaminergic agents are independent of the receptors. This analogy is helpful in explaining the relevance of this information. All of these dopaminergic agents, ordered according to this new information, are reported in Tables 3 and 4. We also include Table 1S as supporting information with all the information reported until now about these drugs. We hope this information will be useful for better and rational treatment of psychosis.

Conclusions

In this study, new information of 217 antipsychotics is presented based on the theoretical response functions related to the electron transfer process. In order to bind to dopamine receptors and inactivate them, molecules should be electron acceptors. Contrarily, agonists donate electrons and activate them, as dopamine does.

As reported previously, clinical use of these drugs is based on their classification as agonists or antagonists, and many times these classifications (based on experiments with animals) is not precise and is insufficient. For this reason, we hope that this new and more rational information will be functional as a guide in the clinical use of the drugs, improving treatment of psychosis, Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. This research provides new information concerning intrinsic properties of dopaminergic agents, which may be apt for their classification, once affinities for other receptors and biological effects have been taken into account.

Methods

From the databases UniProt50, DrugBank 5.051, Guide to Pharmacology52 and Inxight: Drugs53 pharmaceuticals with dopamine receptor affinity used as antipsychotics were selected for this study, particularly focusing on drugs used to treat psychosis. In total 217 (86 molecules categorized as agonists and 131 molecules classified as antagonists) compounds (Tables 1, 2) were selected and analyzed applying Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

Gaussian09 was used for all electronic calculations54. Initial structures were taken from PubChem55 when available or several initial structures were used for the optimization. Geometry optimizations without symmetry constraints were implemented at M06/6–311 + G(2d,p) level of theory56–59, while applying the continuum solvation model density (SMD) with water, in order to mimic a polar environment60. M06 is one of the hybrid exchange correlation functional designed for main group thermochemistry. This functional has 27% of exact exchange; for the systems studied in this investigation higher percent is not required. Since negative ions are calculated, a triple-ζ basis set was used with diffuse and polarized functions. Harmonic analyses were calculated to verify local minima (zero imaginary frequencies). We considered protonated states of all drugs following the available experimental evidence. All molecular data of the optimized structures are available on request.

The response functions that we used in this investigation are the electro-donating (ω−) and electro-accepting (ω+) powers, previously reported by Gázquez et al.61,62. These authors defined the propensity to donate charge or ω− (1) as follows:

| 1 |

whereas the propensity to accept charge or ω+ (2) is defined as

| 2 |

I and A are vertical ionization energy and vertical electron affinity, respectively. Note that in ω− the ionization energy has a higher weight in the equation and in ω+ electron affinity, which is in accordance with chemical intuition. Lower values of ω− imply greater capacity for donating charge. Higher values of ω+ imply greater capacity for accepting charge. In contrast to I and A, ω− and ω+ refer to charge transfers, not necessarily from one electron. This definition is based on a simple charge transfer model expressed in terms of chemical potential and hardness. The Donor–Acceptor Map previously defined49 is a useful graphical tool that has been used successfully in many different chemical systems63–65. We have plotted ω− and ω+ (Fig. 5) on this map, enabling us to classify substances as either electron donors or acceptors. Electrons are transferred from good donor systems (down to the left of the map) to good electron acceptor systems (up to the right of the map). In order to analyze electron-donor acceptor properties, vertical ionization energy (I) and vertical electron affinity (A) were obtained from single point calculations of the corresponding cationic and anionic molecules, using the optimized structure of the neutrals. The same level of theory was used for all computations.

Figure 5.

Donor–acceptor map (DAM).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by DGAPA-PAPIIT and Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT). Guillermo Goode-Romero is very grateful with CONACyT (No. 749523/857743). This work was carried out using Miztli HP Cluster 3000 supercomputer, provided by Dirección General de Cómputo y Tecnologías de Información y Comunicación (DGTIC), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). Authors would like to acknowledge Oralia L Jiménez, María Teresa Vázquez and Cain González for their technical support. Guillermo Goode-Romero and Laura Dominguez thank to LANCAD-UNAM-DGTIC-306. Ana Martínez thanks to LANCAD-UNAM-DGTIC-141. Dedicated to Antonio Martínez.

Author contributions

All the authors contributed to the manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guillermo Goode-Romero, Email: guillermo_david_goode@comunidad.unam.mx.

Ana Martínez, Email: martina@unam.mx.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-78446-4.

References

- 1.Perala J, et al. Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2007;64:19–28. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American-Psychiatric-Association D. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Philadelphia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volk DWDA. Lewis In Rosenberg’s Molecular and Genetic Basis of Neurological and Psychiatric Disease. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Konopaske GT, Coyle JT. Schizophrenia. In: Zigmond MJ, Coyle JT, Rowland L, editors. Neurobiology of Brain Disorders. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2015. pp. 639–654. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fröhlich F. Network Neuroscience. Cambridge: Academic Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zielasek J, Gaebel W. Schizophrenia. In: Wright JD, editor. International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioral Sciences. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hosak L, Hosakova J. The complex etiology of schizophrenia—general state of the art. Neuroendrocinol. Lett. 2015;36:631–637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rădulescu A. A multi-etiology model of systemic degeneration in schizophrenia. J. Theor. Biol. 2009;259:269–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walter E, Kestler L, Bollini A, Hochman KM. SCHIZOPHRENIA: etiology and course. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2004;55:401–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dean B. Neurochemistry of schizophrenia: the contribution of neuroimaging postmortem pathology and neurochemistry in Schizophrenia. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12:2375–2392. doi: 10.2174/156802612805289935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li P, Snyder GL, Vanover KE. Dopamine targeting drugs for the treatment of schizophrenia: past, present and future. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016;16:3385–3403. doi: 10.2174/1568026616666160608084834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wickelgren I. A new route to treating schizophrenia? Science (80-) 1998;281:1264–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marino MJ, Knutsen LJ, Williams M. Emerging opportunities for antipsychotic drug discovery in the postgenomic era. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:1077–1107. doi: 10.1021/jm701094q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forray C, Buller R. Challenges and opportunities for the development of new antipsychotic drugs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017;143:10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delay J, Deniker P, Harl JM. Therapeutic method derived from hiberno-therapy in excitation and agitation states. Ann. Med. Psychol. (Paris) 1952;110:267–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chauhan A, Mittal A, Arora PK. Atypical antipsychotics from scratch to the present. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;4:184–204. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Potkin SG, et al. Aripiprazole, an antipsychotic with a novel mechanism of action, and risperidone vs placebo in patients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60:681–690. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burris KD, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel antipsychotic, is a high-affinity partial agonist at human dopamine D2 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2002;302:381–389. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.033175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mauri MC, et al. Clinical pharmacology of atypical antipsychotics: an update. Exp. Clin. Sci. Int. Online J. Adv. Sci. 2014;13:1163–1191. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapur S, Seeman P. Does fast dissociation from the dopamine D2 receptor explain the action of atypical antipsychotics? A new hypothesis. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:360–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. Br. Med. J. 2000;321:1371–1376. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7273.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ananth J, Burgoyne KS, Gadasalli R, Aquino S. How do the atypical antipsychotics work? J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2001;26:385–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seeman P. Atypical antipsychotics: mechanism of action. Can. J. Psychiatry. 2002;47:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horacek J, et al. Mechanism of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs and the neurobiology of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:389–409. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyamoto S, Duncan GE, Marx CE, Lieberman JA. Treatments for schizophrenia: a critical review of pharmacology and mechanisms of action of antipsychotic drugs. Mol. Psychiatry. 2005;10:79–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stahl SM. Drugs for psychosis and mood: unique actions at D3, D2, and D1 dopamine receptor subtypes. CNS Spectr. 2017;22:375–384. doi: 10.1017/S1092852917000608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stepnicki P, Kondej M, Kaczor A. Current concepts and treatments of schizophrenia. Molecules. 2018;23:2087. doi: 10.3390/molecules23082087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laborit H, Huguenard P, Aullaume R. Un nouveau stabilisateur végétatif (le 4560 R.P.) Le Press Médicale. 1952;60:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.López-Muñoz F, et al. History of the discovery and clinical introduction of chlorpromazine. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;17:113–135. doi: 10.1080/10401230591002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell P. Chlorpromazine turns forty. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 1993;27:370–373. doi: 10.3109/00048679309075791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenbloom M. Chlorpromazine and the psychopharmacologic revolution. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2002;287:1860–1861. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1860-JMS0410-6-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd-Kimball D, et al. Classics in chemical neuroscience: chlorpromazine. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2019;10:79–88. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meltzer HY, Bastani B, Ramirez L, Matsubara S. Clozapine: new research on efficacy and mechanism of action. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1989;238:332–339. doi: 10.1007/BF00449814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wenthur CJ, Lindsley CW. Classics in chemical neuroscience: clozapine. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2013;4:1018–1025. doi: 10.1021/cn400121z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seeman P. Clozapine, a fast-off-D2 antipsychotic. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014;5:24–29. doi: 10.1021/cn400189s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chopko TC, Lindsley CW. Classics in chemical neuroscience: risperidone. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018;9:1520–1529. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tyler MW, Zaldivar-Diez J, Haggarty SJ. Classics in chemical neuroscience: ketamine. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017;8:444–453. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.7b00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robinson TE. Behavioral sensitization: characterization of enduring changes in rotational behavior produced by intermittent injections of amphetamine in male and female rats. Psychopharmacology. 1984;84:466–475. doi: 10.1007/BF00431451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Robinson TE, Becker JB. Enduring changes in brain and behavior produced by chronic amphetamine administration: a review and evaluation of animal models of amphetamine psychosis. Brain Res. 1986;396:157–198. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(86)90002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herrera-Marschitz M. Effect of the dopamine D-1 antagonist SCH 23390 on rotational behaviour induced by apomorphine and pergolide in 6-hydroxy-dopamine denervated rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1985;109:349–354. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(85)90395-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carlsson A. Thirty years of dopamine research. Adv. Neurol. 1993;60:1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl SM, Shayegan DK. The psychopharmacology of ziprasidone: receptor-binding properties and real-world psychiatric practice. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2003;64:6–12. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v64n0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Edwards AC, Bacanu S-A, Bigdeli TB, Moscati A, Kendler KS. Evaluating the dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia in a large-scale genome-wide association study. Schizophr. Res. 2016;176:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mailman RB, Gay EA. Novel mechanisms of drug action: functional selectivity at D2 dopamine receptors. Med. Chem. Res. 2004;13:115–126. doi: 10.1007/s00044-004-0017-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martínez A, Ibarra IA, Vargas R. A quantum chemical approach representing a new perspective concerning agonist and antagonist drugs in the context of schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0224691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martínez A, Vargas R. A component of the puzzle, when attempting to understand antipsychotics: a theoretical study of chemical reactivity indexes. J. Pharmacol. Pharm. Res. 2018;1:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Martínez A. Dopamine antagonists for the treatment of drug addiction: PF-4363467 and related compounds. Eur. J. Chem. 2020;11:84–90. doi: 10.5155/eurjchem.11.1.84-90.1970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huhn M, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394:939–951. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martínez A, Rodríguez-Gironés MA, Barbosa A, Costas M. Donator acceptor map for carotenoids, melatonin and vitamins. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2008;112:9037–9042. doi: 10.1021/jp803218e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bateman A, et al. UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wishart DS, et al. DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1074–D1082. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harding SD, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D1091–D1106. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. NCATS. NCATS Creates Drug Development Data Portal. National Center for Advancing (2020).

- 54.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.08. (2009).

- 55.Kim S, et al. PubChem substance and compound databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D1202–D1213. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Petersson GA, et al. A complete basis set model chemistry. I. The total energies of closed-shell atoms and hydrides of the first-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 1988;89:2193–2218. doi: 10.1063/1.455064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Petersson GA, Al-Laham MA. A complete basis set model chemistry. II. Open-shell systems and the total energies of the first-row atoms. J. Chem. Phys. 1991;94:6081–6090. doi: 10.1063/1.460447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McLean AD, Chandler GS. Contracted Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. I. Second row atoms, Z=11–18. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:5639–5648. doi: 10.1063/1.438980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krishnan R, Binkley JS, Seeger R, Pople JA. Self-consistent molecular orbital methods. XX. A basis set for correlated wave functions. J. Chem. Phys. 1980;72:650–654. doi: 10.1063/1.438955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Marenich AV, Cramer CJ, Truhlar DG. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Chem. Phys. B. 2009;113:6378–6396. doi: 10.1021/jp810292n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gázquez JL, Cedillo A, Vela A. Electrodonating and electroaccepting powers. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111:1966–1970. doi: 10.1021/jp065459f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gázquez JL. Perspectives on the density functional theory of chemical reactivity. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2008;52:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Martínez A. Donator acceptor map of psittacofulvins and anthocyanins: are they good antioxidant substances? J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:4915–4921. doi: 10.1021/jp8102436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cerón-Carrasco JP, Bastida A, Requena A, Zuñiga J, Miguel BA. Theoretical study of the reaction of β-carotene with the nitrogen dioxide radical in solution. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2010;114:4366–4372. doi: 10.1021/jp911846h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alfaro RAD, Gómez-Sandoval Z, Mammino L. Evaluation of the antiradical activity of hyperjovinol-A utilizing donor-acceptor maps. J. Mol. Model. 2014;20:2337. doi: 10.1007/s00894-014-2337-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.