Abstract

The aim of deformable brain image registration is to align anatomical structures, which can potentially vary with large and complex deformations. Anatomical structures vary in size and shape, requiring the registration algorithm to estimate deformation fields at various degrees of complexity. Here, we present a difficulty-aware model based on an attention mechanism to automatically identify hard-to-register regions, allowing better estimation of large complex deformations. The difficulty-aware model is incorporated into a cascaded neural network consisting of three sub-networks to fully leverage both global and local contextual information for effective registration. The first sub-network is trained at the image level to predict a coarse-scale deformation field, which is then used for initializing the subsequent sub-network. The next two sub-networks progressively optimize at the patch level with different resolutions to predict a fine-scale deformation field. Embedding difficulty-aware learning into the hierarchical neural network allows harder patches to be identified in the deeper sub-networks at higher resolutions for refining the deformation field. Experiments conducted on four public datasets validate that our method achieves promising registration accuracy with better preservation of topology, compared with state-of-the-art registration methods.

Keywords: deformable registration, brain MRI, cascaded neural network, difficulty-aware sampling

1. Introduction

Deformable image registration is fundamental to medical image processing and analysis, with applications in for example clinical diagnosis, radiation therapy planning, and morphometric analysis of anatomical structures. Deformable registration methods aim at finding a non-linear transformation that establishes anatomical correspondences between a pair of images (Sotiras et al., 2013). Conventional registration methods (Avants et al., 2008; Vercauteren et al., 2009; Muyan-Ozcelik et al., 2008; Lorenzi et al., 2013; Luo et al., 2015; Thirion, 1998; Vercauteren et al., 2007, 2008) utilize computationally expensive numerical optimization and require parameter tuning for different datasets, rendering them inefficient in clinical settings. Recently, deep learning registration methods have been shown to be more robust and computationally efficient, making them viable for real-world applications.

1.1. Related Work

1.1.1. Deep Learning Deformable Registration

Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), such as fully convolutional network (FCN) (Long et al., 2015) and U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015) are usually employed for deep learning deformable registration. The output of a registration network can either be a set of deformation parameters or a full deformation field (Balakrishnan et al., 2018; Dalca et al., 2018). Learning-based registration methods can be broadly divided into three categories according to the training strategy:

Supervised training (Dosovitskiy et al., 2015; Rohé et al., 2017; Sokooti et al., 2017) - Supervised training requires that the training dataset includes the corresponding ground-truth deformation fields in addition to the images. The deformation fields are obtained by conventional registration methods (Cao et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2018). The accuracy of the deformation fields depends greatly on the registration method. The errors of deformation fields negatively impact training. Alternatively, CNNs can also be trained with synthetic deformation fields (Eppenhof and Pluim, 2019; Eppenhof and P. W. Pluim, 2018). However, synthetic deformations do not necessarily reflect real deformations.

Weakly-supervised training (Hu et al., 2018a,b) - Weakly-supervised training is employed in multi-modal image registration methods. These methods do not register the images across modalities based directly on the intensity but on surrogates such as segmentation maps or landmarks. For example, Hu et al. (2018a) trained a network to maximize the overlap between the tissue labels of a pair of images. However, accurate tissue labeling is laborious and time consuming, and registration accuracy can be undermined by incorrect tissue labels.

Unsupervised training (de Vos et al., 2017, 2019a) - A unsupervised registration network is typically equipped with a spatial transformer network (STN) layer (Jaderberg et al., 2015), which warps the moving image with the learned deformation field. The network then evaluates the similarity of the fixed image and the warped moving image using a loss function defined based on metrics such as sum of squared differences (SSD) and normalized cross correlation (NCC) (Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2017). The gradient of the loss function is then backpropagated through the registration network for parameter update. In contrast to supervised and weakly-supervised registration methods, unsupervised registration methods do not require ground-truth deformation fields or tissue labels. Recent methods (Hering and Heldmann, 2019; Balakrishnan et al., 2018; Dalca et al., 2018) leverage this advantage for unsupervised registration.

1.1.2. Multi-Scale Registration

The aforementioned deformable registration methods are trained either image-wise or patch-wise. Image-wise registration methods (Balakrishnan et al., 2018; Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Dalca et al., 2018; Dosovitskiy et al., 2015; Eppenhof and Pluim, 2019; Eppenhof and P. W. Pluim, 2018; de Vos et al., 2017; Hering and Heldmann, 2019) can more effectively capture global contextual information, but require a large amount of GPU memory, which increases with the number of feature channels in the network. In contrast, by dividing a large image into small patches, training is more effective even with a limited number of images (Yang et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2019; Sokooti et al., 2017; Cao et al., 2018). Patches capture more localized information for characterizing subtle deformations. Due to the smaller input size, patch-wise methods allow a greater number of feature channels and deeper CNNs, thus extracting more features to improve registration accuracy. For instance, Fan et al. (2019) introduced a patch-based network for brain MRI registration, trained using single-scale patches extracted with equal spacing. Since not all patches provide meaningful information, Yang et al. (2017) devised a method to discard patches belonging to the background and further reduce the number of patches by increasing the stride of the sliding window. Although successful, these single-scale registration methods consider either global or localized information, failing to concurrently use the information from multiple scales.

Conventional registration methods typically utilize global and local contextual information in multiple resolutions and optimize the deformation field in a coarse-to-fine manner (Maintz and Viergever, 1998). Coarse-to-fine learning strategies have been shown to improve accuracy in classification (Murthy et al., 2016), segmentation (Zhao et al., 2018), detection (Li et al., 2015; Cai et al., 2015), pose estimation (Toshev and Szegedy, 2014), and registration (de Vos et al., 2019b; Hering et al., 2019). Multi-scale registration can be implemented as a cascade of sub-networks for registration at different resolutions (de Vos et al., 2019b; Hering et al., 2019). However, deformation interpolation errors at different scales can propagate, accumulate, and jeopardize registration accuracy. To mitigate interpolation error, RegNet (Sokooti et al., 2017) extracts features from patches at four different scales and concatenates these multi-scale features with convolution layers in the registration of 3D chest CT scans. However, direct concatenation does not necessarily make full use of information at different resolutions. A deep-supervision strategy was introduced to optimize deformation learning at multiple scales via diffeomorphic registration using a probabilistic model (DRPM) (Krebs et al., 2019). However, the number of feature channels of DRPM is limited by GPU memory, limiting the capacity of the network in capturing complex deformations.

1.1.3. Patch Sampling

Uniform and random sampling strategies are typically used for patch selection. However, not all patches provide information useful for guiding registration (Li et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2019). Different patches are associated with deformations with different degrees of complexity (Fig. 1). Uniform and random sampling is agnostic to patch contents and deformation complexity. Hard-to-register patches need to be identified so that the network can focus more on aligning these patches correctly.

Fig. 1:

Illustration of easy- and hard-to-register patches.

1.2. Contributions

In this work, we introduce an unsupervised learning strategy for multi-scale deformable image registration with a patch selection strategy that is driven by patch-based registration difficulty. The main contributions of our work are summarized below:

We devise a novel multi-scale registration network by incorporating multi-scale information into a cascaded framework to refine deformations in a coarse-to-fine manner. Coarse deformation fields predicted by a previous network are fed into a subsequent sub-network so that global contextual information can be used to guide local refinement.

We design a difficulty-aware module to progressively feedforward hard regions to subsequent sub-networks. This mechanism is implemented via an attentive skip connection module and an adaptive patch selection strategy. These two techniques effectively reduce the number of patches and allow the network to focus on image patch pairs with large structural differences.

We employ a dynamic anti-folding constraint to penalize folding and tearing so that the invertibility of the deformations fields can be preserved.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we present the proposed registration method. In Section 3, we describe the dataset and evaluation metrics used to test registration performance. In Section 4, we show evaluation results for inter-subject registration. Finally, we conclude the paper in Section 5.

2. Methods

Registration can be complicated by spatially-varying complexity of anatomical structures. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to equip a registration network with a difficulty-aware module to automatically identify hard-to-register regions for improving registration accuracy. The proposed deep neural network (DNN) leverages a cascaded framework to progressively improve deformation estimations in a coarse-to-fine manner. Across the cascade, each subsequent registration network focuses on a decreasing receptive field of view (FoV) in millimeters but maintains the same number of voxels within the FoV by image upsampling. The deformation estimated by the network at each scale initializes the subsequent finer-scale network. In this way, the proposed DNN can harness multi-scale contextual information to gradually improve registration accuracy. The proposed method is described next in detail.

2.1. Overview

Fig. 2 illustrates the architecture of our cascaded DNN, which performs registration in a multi-scale manner. The framework consists of three sub-networks for extracting features at multiple scales. Each sub-network, except the first one, is initialized with the deformation field obtained from the preceding sub-network, thus progressively improving the deformation field estimation at a finer scale.

Fig. 2:

Overview of the proposed DNN based registration framework.

All the three sub-networks have an identical registration network architecture, with the same input image size and the same number of feature channels. To design the network with limited GPU memory, a resizing module is also added to sub-network S1 and sub-network S2 for downsampling by factors of 4 and 2, respectively. Correspondingly, an upsampling module with linear interpolation is also added at the end of these two registration sub-networks for upsampling the predicted deformation field by factors of 4 and 2, respectively.

S1 takes the whole image as input, thus capturing global contextual information and generating a coarse deformation field. The subsequent sub-networks predict the fine-scale deformation fields using both image patches and deformation field patches extracted at different scales. Thus, our method is conceptually akin to the auto-context model (Tu and Bai, 2010), and estimates deformation field in a cascaded manner. As the registration progresses, it focuses on more localized discrepancies between fine-scale image patches. Here, we design a difficulty-aware guidance module to adaptively identify patches that characterize complex deformations for effectively optimizing the local deformation fields across patches for stable training. The architectures of registration network and the adaptive difficulty-aware guidance module are explained below.

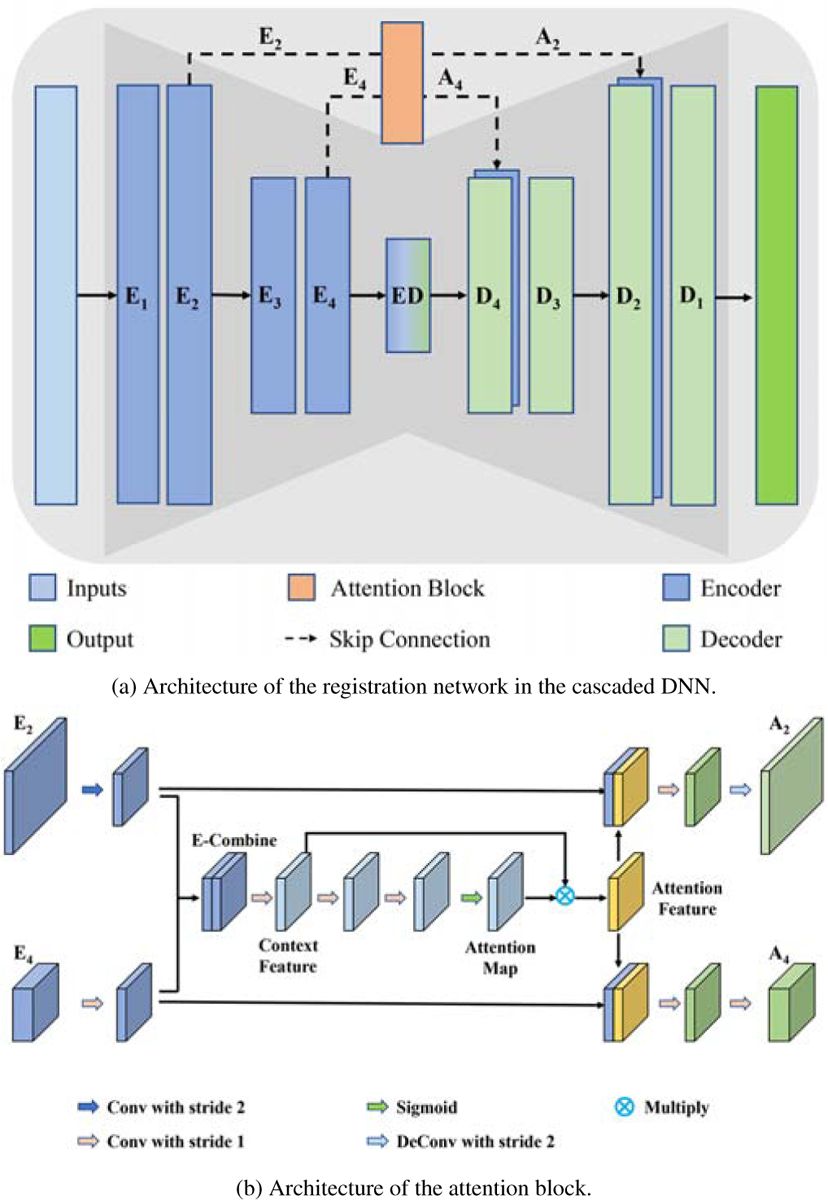

2.2. Registration Network Architecture

The registration network (Fig. 3(a)) is akin to U-Net (Ronneberger et al., 2015) and consists of an encoder-decoder with skip connections. 3D convolutions followed by Leaky ReLU activations are utilized in the encoder and decoder paths, with a convolutional kernel size of 3 × 3 × 3. Also, two convolution layers with a stride of 2 are employed in the encoder path to halve the spatial dimensions. Although all three registration sub-networks S1, S2 and S3 take 3D volumes as inputs, their channel sizes are different. That is, S1 concatenates only the input images into a 2-channel 3D volume, whereas S2 and S3 additionally concatenate the preceding sub-network generated deformation field into patches of size 56 × 56 × 56 × 5, consisting of the patches extracted from the moving image (moving patch), the fixed image (fixed patch), and the three components of the deformation field (i.e., deformations in x, y, z directions). Note that, an attentive skip connection replaces the skip connection to merge multi-level information in the encoder path into a context feature map. The output of the attention module can be concatenated with the corresponding layer in the decoder path to achieve a refined deformation field. The attention module is described next.

Fig. 3:

Illustration of the proposed registration network.

2.3. Adaptive Difficulty-Aware Guidance

Image registration accuracy is affected by the degree of alignment of regions with large structural discrepancies. Such regions are often associated with large deformations and are difficult to align. Thus, there is a need to devise an algorithm that focuses more on difficult-to-register image regions. Here, we propose to use an attentive skip connection to aggregate features maps for generating refined deformation fields and a patch selection strategy to automatically localize complex regions associated with large deformations.

2.3.1. Attentive Skip Connection for Feature Aggregation

Similar to U-Net, each layer in the encoder path (Fig. 3(a)) is associated with information at different scales. Low-level features in the top layer (E2 in Fig. 3(a)) provide spatial details, which are beneficial for aligning image regions with small deformations, but are too noisy for providing semantic guidance. In contrast, high-level features in the bottom layer (E4 in Fig. 3(a)) provide relatively distinct semantic boundaries, allowing the recovery of large deformations. To leverage multi-level spatial and contextual information for feature aggregation, a common strategy is to use skip connection, which directly copies feature maps in the encoder path to the corresponding layer in the decoder path. However, the standard skip connection neglects the fact that not all the spatial information from the features of different levels in the encoder path contributes positively in generating the deformation field. This motivates us to design a novel skip connection to aggregate feature maps. Here, we introduce an attention mechanism (Vaswani et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2018; Fu et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017) to combine low-level and high-level information in the skip connection for facilitating the generation of a more accurate deformation field.

Fig. 3(b) shows the proposed attentive skip connection module. Here, we combine both the high-level and low-level feature maps. To effectively leverage the multi-level features and generate the context features, feature map E2 (low-level features) is first down sampled to the same size as feature map E4 (high-level features) by a convolution layer with kernel size 3 × 3 × 3 and stride 2. The number of feature channels of E4 is reduced to match E2 through a convolution layer with kernel size 1 × 1 × 1 and stride 1. Then, the two feature maps with the same size and the same number of feature channels are directly concatenated, denoted as E-combine in Fig. 3(b). In this way, E-combine is equipped with both the high-level and low-level information. Subsequently, a convolution layer with kernel size of 1 × 1 × 1 and stride of 1 is applied on E-combine to further fuse and refine the context features. Following two convolution layers with kernel size 3 × 3 × 3 and stride 1, and a sigmoid function, we can obtain the attention map, which is utilized to automatically select patches for the subsequent sub-networks. As shown in Fig. 4, the attention map highlights the hard-to-register regions, which can be used for localizing the regions that require further refinement. A higher value in the attention map is associated with a higher probability of large deformation. The subsequent element-wise multiplication of attention map with the context feature results in an attention feature map with rich context information (Fig. 3(b)). In order to fully utilize the context information for features at each level, the attention feature map is then concatenated with the resized E2 and E4, respectively. Refined feature map containing context information for high-level and low-level feature maps can be generated through a convolution layer with kernel size 3 × 3 × 3 and stride 1, and a convolution layer with kernel size 3 × 3 × 3 and stride 2, respectively. Finally, the refined level-wise feature map can be concatenated with the corresponding feature map in the decoder path, thus facilitating the registration network in generating the refined deformation field. Compared with the standard skip-connection, the effect of refinement of the attentive skip-connection module on features is presented in Section 1 of the supplemental material.

Fig. 4:

Illustration of the effectiveness of the attentive skip connection for feature aggregation. (a) Input image pair. (b)-(d) The features from sub-networks S1, S3, and S3. Feature maps and deformation magnitude maps are shown for the standard skip connection in the top row and the attentive skip connection in the bottom row. The attention maps are shown in the middle row. The feature maps of the standard and attentive skip connections are derived respectively from layer E2 and layer A2 of the three sub-networks. The deformation magnitude ranges from 0 to 10, and the attention value from 0 to 1.

Fig. 4 illustrates the feature maps and the corresponding magnitude of deformation derived from the top convolution layer in the U-Net with and without the attention module at each scale. Comparing the features without attention (first row of Fig. 4) and with attention (third row of Fig. 4) show that features are enhanced in each resolution with our attentive skip connection. Particularly, the magnitude images with the attention module are closer to the attention map than those without the attention module, indicating that the proposed attention module contributes to improving the prediction of large deformations.

2.3.2. Adaptive Patch Selection

Image patch pairs with large anatomical differences are difficult to align, requiring more efforts in determining structural correspondences. Image patches that are rich with structural information should be used to guide registration. As shown in Fig. 4, feature maps without attention module do not specifically focus on hard-to-register regions. In contrast, the attention map highlights the regions associated with large deformations, allowing the subsequent patch selection module to select the corresponding patches for focused registration. For instance, in Fig. 4 the attention map highlights the cortex and the lateral ventricles, which are often associated with large deformations, and suppresses the regions like white matter with less intensity variations.

In order to quickly extract the informative patches, we design a patch selection strategy based on a region proposal method and non-maximum suppression (NMS) algorithm (Ren et al., 2015; Girshick et al., 2014). The steps involved in patch selection are described below:

Candidate Patches – The attention map is first upsampled to the same size as the input to the preceding sub-network. The attention map is then traversed with a spatial window of size 112 and 56 for the low and middle resolution sub-networks, respectively, matching the input size of the corresponding sub-network. A score is computed for candidate patch covered by each window.

- Patch Scoring – For each candidate patch, an energy score is computed and the patches with higher energy values are selected, discarding the patches with extreme local maxima. The energy function for scoring each candidate patch is given as

where N refers to the total number of voxels within the patch P. Vi refers to the magnitude of the i-th voxel on the attention feature map. Nfg denotes the number of foreground voxels, which have higher magnitudes than the background. The first term in Eq. (1) defines the average value within each candidate patch. The second term defines the ratio of foreground voxels in the patch. The coefficient κ balances the two terms and is set to 10 based on grid search as described in Section 4 of the supplemental material. Thus, the energy score reflects the degree to which the candidate patch characterizes complex deformations.(1) Patch Pruning – Some of the high scoring patches determined from the previous step may overlap with each other. Thus, we need to discard redundant patches and retain only patches uniformly covering the brain region. To this end, we adopt NMS strategy with the intersection over union (IoU) threshold at 0.3 to select the non-overlapping patches.

Fig. 5 shows the intermediate results of patch selection module, where candidate patches signifying large deformations can be easily distinguished according to their respective energy scores. The NMS algorithm effectively reduces redundant patches with high overlap, allowing DNN training to be carried out effectively and efficiently.

Fig. 5:

Outputs of intermediate steps of the patch selection module.

2.4. Loss Function

2.4.1. Unsupervised Loss Function

The optimal deformation field ϕ is obtained by maximizing the following energy function:

| (2) |

where the first term Sim(IF, IM◦ϕ) corresponds to the similarity between the fixed image IF and the warped moving image IM◦ϕ, and the second term Reg(ϕ) refers to the regularization of the deformation field for preserving the smoothness of ϕ. We used NCC (Balakrishnan et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2017) as a similarity metric, and evaluated the smoothness of the deformation field by computing the spatial gradients. The loss function for each sub-network is defined as follows:

| (3) |

where Sj refers to different sub-networks, K corresponds to the neighboring voxels of the center voxel k, and α controls the balance between image alignment and deformation field smoothness. We empirically set the value of α to 1.5 for all the three sub-networks.

2.4.2. Dynamic Anti-Folding Constraint

For large values of α in Eq. (3), the deformation field would be excessively regularized, penalizing the registration accuracy. Contrastingly, smaller values improve registration accuracy but may cause folding artifacts. During image registration, all voxels do not necessarily undergo the same amount of deformation, thus, we need to penalize only voxels that undergo severe deformations and lead to folding and tearing. Here, we propose to use the dynamic anti-folding constraint defined as

| (4) |

where Γ(·) is an indicator function:

| (5) |

Δϕi(p) is the Laplacian of the deformation field ϕ along the i-th direction at voxel location p. Function Δ(·) is an index function used to localize the voxels with folding, which have negative second-order derivative. Thus, in addition to the smoothness constraint in Eq. (3), voxels undergoing folding will have an additional smoothness weight to strengthen the constraint of the regularization of deformations.

2.4.3. Total Loss Function

The total loss function for the registration network is given as

| (6) |

where , , and correspond to the loss functions of sub-network S1, sub-network S2, and sub-network S3 (Fig. 2), respectively. In this study, the coefficients , , and are set to 1.

3. Experimental Settings

3.1. Data

Training and Validation Dataset –

We trained and validated our method on 40 T1-weighted MR brain images from LONI LPBA40 dataset (Klein et al., 2009). Particularly, 30 subjects (30 × 29 image pairs) were randomly selected for training, and the remaining 10 subjects were used for validation. Thus, a total of 90 (10 × 9) image pairs were used to validate, and the corresponding segmentation maps consisting of 54 labeled anatomical ROIs were warped using predicted deformation fields to measure registration accuracy.

Testing Dataset –

To evaluate the generalizability of our proposed registration network, we tested our trained network on multi-site public datasets, including IBSR18, CUMC12, and MGH10 (Klein et al., 2009). For each testing dataset, all the subject images were registered with each other i.e., IBSR18, CUMC12, and MGH10 provide 306, 132, and 90 image pairs for registration, respectively. To evaluate registration accuracy, we used segmentation maps comprising of 96, 128, and 106 labeled anatomical ROIs in IBSR18, CUMC12, and MGH10 datasets, respectively.

Preprocessing –

We performed standard pre-processing steps on all subjects. All scans were histogram matched to standardize the intensity range. Then, these scans were resampled to the same size (224 × 224 × 224) and same voxels resolution (1 × 1 × 1 mm3). Finally, all the datasets were affine registered using ANTs toolkit (Avants et al., 2008).

3.2. Implementation Details

The registration network was implemented using TensorFlow library on a single Nvidia TitanX (Pascal) GPU. We adopted Adam optimization with learning rate set to 1 × 10−4 for 300k iterations.

During the training stage, the three sub-networks in the cascade were learned progressively. First, the sub-network at the coarsest level was trained for a fixed number of epochs. The middle sub-network and the coarsest sub-network were then trained jointly. The coarsest sub-network provided both the initial deformation and the hard-to-register patches depending on the patch selection strategy for the middle sub-network. The same procedure was repeated at the finest level. During the testing stage, we removed the patch selection module (see Fig. 2) and used only image pairs with full resolution as input for the cascade. The final output was the deformations predicted by the sub-network at the finest scale.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and 95-th percentile Hausdorff distance (HD) between two boundaries in millimeters were used to measure the registration accuracy of labeled anatomical structures. We computed the average DSC and HD over all ROI labels.

The smoothness of the predicted deformation field is evaluated using the Jacobian determinant (JD), with positive values indicating invertibility and topology preservation. We computed the percentage of voxels with negative JD (NJD) values and the average value of the norm of the gradient of Jacobian determinant (NGJD) to gauge the compared registration methods in terms of deformation smoothness. A higher DSC with nearly zero NJD corresponds to better registration performance.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Baseline Methods

We compare our method, hierarchical difficulty-aware registration (HDAR), with

Three conventional registration methods, i.e., diffeomorphic demons (D. Demons, (Vercauteren et al., 2009)), LCC-Demons (Lorenzi et al., 2013), and Symmetric Normalization (SyN, (Avants et al., 2008)),

Two unsupervised single-scale deep-learning registration methods, i.e., two versions of VoxelMorph (VM): VM (CVPR) (Balakrishnan et al., 2018) and VM (MICCAI) (Dalca et al., 2018), and

Three recent multi-scale learning-based registration methods (de Vos et al., 2019b; Hering et al., 2019; Krebs et al., 2019).

Note that, the DSCs (mean (± std)) of the affine-aligned datasets are 67.5 (± 1.7), 47.4 (± 2.9), 54.5 (± 2.0), and 57.8(± 2.1) for LONI18, IBSR18, CUMC12, and MGH10, respectively. The corresponding HDs (mean (± std)) are 7.8 (± 1.0), 8.8 (± 1.0), 8.0 (± 1.3), and 9.2 (± 1.3).

4.1.1. Conventional Methods

We compared HDAR with D. Demons, LCC-Demons, and SyN, which are widely used traditional registration methods. Table 1 summarizes the results over all ROIs of the different datasets, indicating that HDAR yields the best accuracy with few foldings.

Table 1:

Summary of DSC, HD, NJD, and NGJD computed over all ROIs of the different datasets.

| D. Demons | LCC-Demons | SyN | HDAR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 72.1 (±1.6) | 5.8 (±0.4) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 4.6 (±0.5) | 72.6 (±1.7) | 5.8 (±0.4) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 6.6(±0.5) | 72.7 (±1.4) | 5.8 (±0.7) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 7.6(±0.5) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.6 (±0.4) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 6.1(±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 53.6 (±3.1) | 8.0 (±1.1) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 6.2 (±0.4) | 55.6 (±3.1) | 7.8 (±1.0) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 9.2(±0.4) | 57.2 (±3.0) | 7.7 (±0.8) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 10.2(±1.0) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.1) | 9.0(±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 62.1 (±1.7) | 7.1 (±1.1) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 5.5 (±0.5) | 65.3 (±1.7) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 8.5(±0.5) | 63.1 (±2.1) | 7.6 (±1.0) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 9.6(±0.7) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 7.3 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±0.7) | 8.5(±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 60.3 (±2.9) | 7.9 (±0.9) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 6.3 (±0.2) | 64.3 (±2.5) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 8.3(±0.2) | 64.1 (±2.5) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 0.0 (±0.0) | 9.4(±1.1) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 7.4 (±0.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) | 8.2(±0.4) |

Fig. 6 shows the registration results of the validation and testing datasets. The zoomed-in views show that the warped moving images obtained with HDAR are structurally more similar to the fixed image than D. Demons, LCC-Demons and SyN.

Fig. 6:

Example registration results given by D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, and HDAR for different datasets. The JD maps range from 0 to 10.

4.1.2. Single-Scale Deep Learning Methods

Two versions of Voxelmorph, i.e., non-diffeomorphic version VM (CVPR) and diffeomorphic version VM (MICCAI), were used in evaluation. We re-trained VM (CVPR) and VM (MICCAI) and optimized the training parameters for best results. Particularly, for VM (MICCAI), we increased the number of scaling and squaring network layers to 14. For fair comparison, we modified the registration network in Fig. 3(a) to use only full-resolution input images.

Table 2 shows that the single-scale methods achieve comparable HDs. Although the VM methods achieve slightly higher DSCs than the proposed method, the NGJD is higher and percentages of voxels with NJDs are at least five times higher than single-scale HDAR. Fig. 7 shows examples of registered moving images with the respective JD maps. The zoomed-in views demonstrate that HDAR yields results that are closer to the fixed images.

Table 2:

Summary of DSC, HD, NJD, and NGJD for single-scale deep-learning-based registration methods.

| VM (CVPR) | VM (MICCAI) | HDAR (Single Scale) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 72.3 (±1.7) | 5.7 (±0.5) | 13.1 (±1.7) | 11.0 (±0.4) | 72.4 (±1.7) | 5.8 (±0.5) | 6.8 (±1.2) | 10.7 (±0.4) | 71.9 (±1.7) | 5.8 (±0.5) | 1.5 (±0.3) | 6.5 (±0.4) |

| IBSR18 | 56.9 (±3.3) | 8.0 (±1.0) | 37.0 (±7.4) | 14.2 (±0.7) | 56.8 (±3.1) | 7.8 (±0.9) | 22.3 (±5.8) | 13.4 (±0.8) | 56.0 (±3.3) | 7.8 (±1.0) | 4.3 (±1.1) | 8.8 (±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 66.2 (±1.8) | 7.5 (±1.0) | 40.4 (±6.4) | 13.3 (±0.5) | 66.1 (±1.7) | 7.5 (±1.0) | 20.6 (±4.0) | 12.3 (±0.6) | 64.9 (±1.9) | 7.5 (±1.0) | 5.0 (±1.0) | 9.0 (±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 64.7 (±2.6) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 38.5 (±4.6) | 14.8 (0.4) | 65.1 (±2.6) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 20.4 (±3.0) | 13.7 (±0.5) | 64.1 (±2.5) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 4.8 (±0.6) | 8.4 (±0.4) |

Fig. 7:

Example registration results given by the single-scale deep-learning registration methods. The JD maps range from 0 to 10.

With the attention module, HDAR can focus on hard-to-register regions and generate a smoother deformation with less foldings. VM (MICCAI) yields comparable DSC and HD with less NJD values than VM (CVPR), but produces deformation fields that are more irregular than all other methods.

4.1.3. Multi-Scale Deep Learning Methods

We compared HDAR with three recent multi-scale learning-based registration methods (Hering et al., 2019; Krebs et al., 2019; de Vos et al., 2019b). Note that, these methods were modified by training the original architectures with the loss function defined in Section 2.4.

Table 3 shows that HDAR yields the highest DSC and the minimum HD. The percentages of NJD of mlRINET (Hering et al., 2019) and HDAR are better than the other two methods. The average NGJD of DRPM (Krebs et al., 2019) and HDAR are lower than the other two methods. Fig. 8 shows the warped moving images and the corresponding JD maps, indicating that HDAR gives the best agreement with the fixed images.

Table 3:

Summary of DSC, HD, NJD, and NGJD for multi-scale deep-learning-based registration methods.

| DLIR | DRPM | mlRIVNET | HDAR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 72.7 (±1.7) | 5.7 (±0.5) | 2.8 (±0.4) | 7.8(±0.4) | 72.8 (±1.8) | 5.7 (±0.5) | 3.1 (±0.5) | 7.1(±0.3) | 72.6 (±1.7) | 5.7 (±0.5) | 2.5 (±0.4) | 8.4(±0.3) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.6 (±0.4) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 6.1 (±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 57.1 (±3.1) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 7.9 (±1.9) | 10.8(±0.5) | 57.3 (±3.2) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 8.1 (±1.9) | 9.3(±0.6) | 56.0 (±3.1) | 4.0 (±1.8) | 7.8 (±1.0) | 10.2(±0.5) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.1) | 9.0 (±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 66.2 (±1.8) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 8.3 (±1.2) | 9.8(±0.3) | 66.5 (±1.8) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 8.5 (±1.4) | 8.6(±0.3) | 65.0 (±1.9) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 4.3 (±1.0) | 9.4(±0.2) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 7.3 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±0.7) | 8.5 (±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 65.4 (±2.6) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 8.7 (±0.9) | 10.6(±0.4) | 65.5 (±2.6) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 8.8 (±1.1) | 8.2 (±0.4) | 64.9 (±2.6) | 7.5 (±0.9) | 5.1 (±0.8) | 10.9(±0.3) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 7.4 (±0.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) | 8.2 (±0.4) |

Fig. 8:

Example registration results given multi-scale deep-learning registration methods. The JD maps range from 0 to 10.

DLIR and mlRIVNET are multi-scale methods that are based on cascaded networks. mlRIVNET incorporates an image pyramid into a cascaded network. DLIR employs multiple networks for multi-scale prediction of the displacements of B-spline control points. Both methods involve deformation composition, image warping at each scale, and feeding the warped image to the network for the next scale.

In contrast, DRPM and HDAR obviate the need for deformation composition. DRPM leverages deep supervision to harness multi-scale information. The layers in the decoding path of DRPM’s U-Net-like architecture are supervised by fixed images at coarser scales for learning of the full-resolution deformation. However, the number of feature channels of DRPM is limited by GPU memory, limiting the capacity of the network in capturing complex deformations. HDAR fully leverages both the global context and local information by employing a cascaded framework to progressively refine predictions in a coarse-to-fine manner. HDAR also circumvents deformation composition by directly incorporating the deformation predicted by a preceding coarser network as part of the input, in addition to the moving image and the fixed image, to the subsequent network for refinement. In addition, the difficulty-aware module automatically identifies hard-to-register regions. HDAR has a larger number of parameters but a lower number of floating-point operations (see Section 3 of the supplementary material).

4.1.4. Statistical Tests

Fig. 9 shows the box plots of the DSCs obtained for 54 labeled anatomical structures of the 10 validation subjects in LONI40 dataset. Paired t-tests show that the DSC improvement given by HDAR are statistically significant (p < 0.05) for 28, 35, 9, 30, 17, 22, 27, and 22 out of 54 ROIs against D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM (CVPR), VM (MICCAI), DLIR, DRPM, and mlRIVNET, respectively. The performance is comparable and for rest of the ROIs. HDAR achieves better performance for hard-to-register regions, like hippocampus in the sub-cortical region and postcentral gyrus in the cortical region. For IBSR18 dataset, our method gave statistically significant improvement in terms of DSC for 87, 66, 23, 46, 34, 17, and 59 out of 96 ROIs over D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM (MICCAI), DLIR, DRPM, and mlRIVNET, respectively, and the DSC scores for all the other ROIs were comparable. The DSC improvement with respect to VM (CVPR) is statistically significant for 53 ROIs, comparable for 15 ROIs and for rest of the ROIs VM (CVPR) performed better than our method. For CUMC12, our method gave statistically significant improvement in terms of DSC for 84, 60, 78, 55, 58, 21, 2, and 42 out of 120 ROIs over D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM (CVPR), VM (MICCAI), DLIR, DRPM, and mlRIVNET, respectively, and comparable performance for rest of the ROIs. For the MGH10 dataset, HDAR give statistically significant improvements in terms of DSC for 74, 37, 29, 25, 8, 11, and 7 out of 106 ROIs over D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM (CVPR), VM (MICCAI), DLIR, and mlRIVNET, respectively. In terms of DSC, HDAR is comparable to DRPM for the 106 ROIs.

Fig. 9:

Box plots of DSCs for 54 labeled anatomical structures of the 10 validation subjects from the LONI40 dataset. The top and bottom subfigures correspond to the left and right hemispheres, respectively. ROIs marked with light blue star  , cyan star

, cyan star  , royal blue star

, royal blue star  , light green star

, light green star  , green star

, green star  , and orange star

, and orange star  , orchid star

, orchid star  , and red star

, and red star  indicate that HDAR gives statistically significant improvements over D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM(CVPR), and VM (MICCAI), DLIR, DRPM, mlRIVNET, respectively.

indicate that HDAR gives statistically significant improvements over D. Demons, LCC-Demons, SyN, VM(CVPR), and VM (MICCAI), DLIR, DRPM, mlRIVNET, respectively.

4.2. Ablation Studies

We investigated the effectiveness of the difficulty-aware module, adaptive patch selection strategy, multi-resolution, and dynamic anti-folding constraint in boosting registration performance.

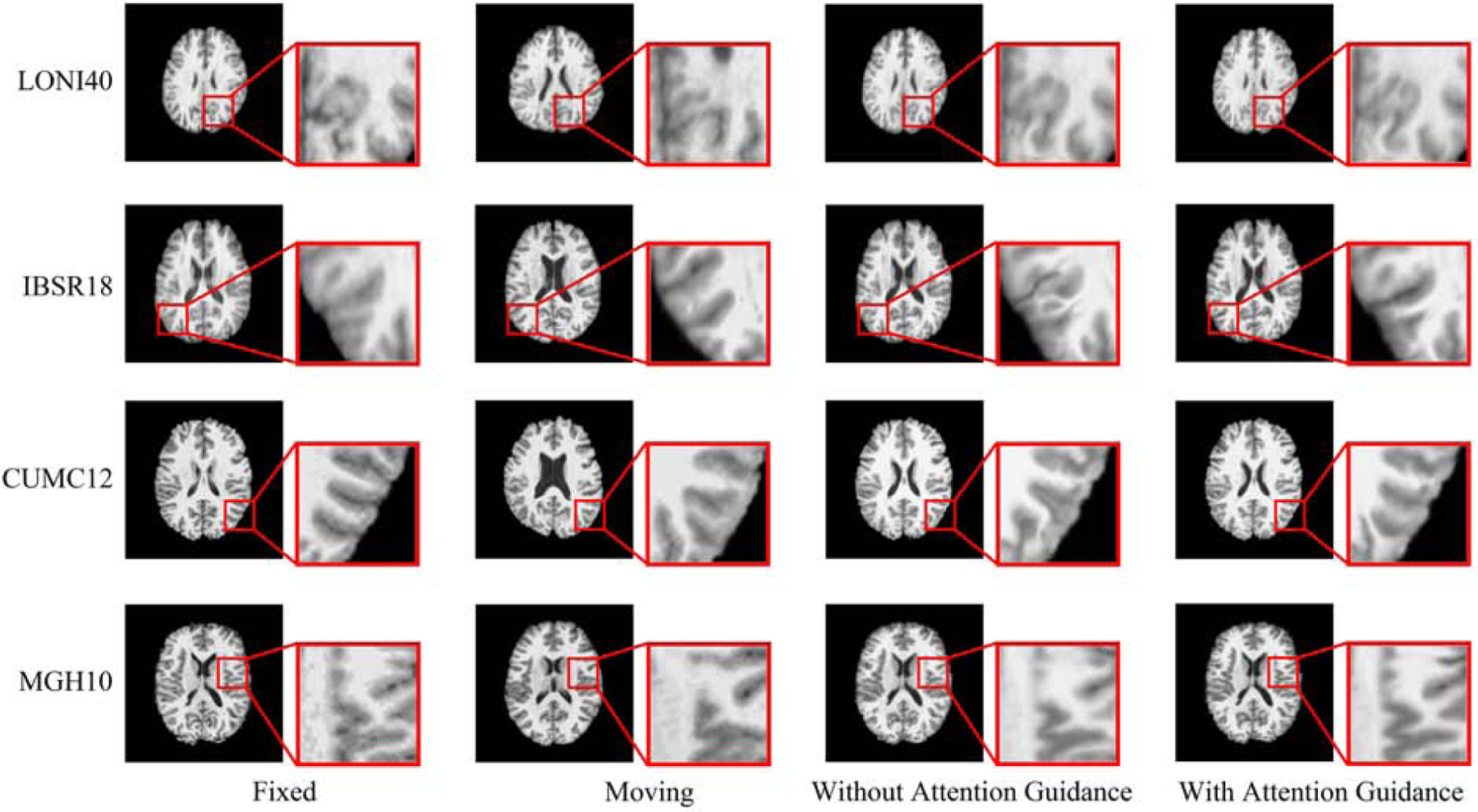

4.2.1. Difficulty Awareness

We evaluated registration performance with and without the attentive skip connection module. The network without attentive skip connection module uses skip connections typical in U-Net. For fair comparison, patches selected by the attention map of the skip attentive connection were used for training in both configurations.

Table 4 summarizes the results for both configurations with and without attention guidance using the validation and testing datasets. The absence of the attention module results in lower DSCs, higher HDs, and greater deformation irregularity. Fig. 10 confirms the improvements given by attention guidance. This shows that the skip connection in the typical U-Net architecture is less effective in feature aggregation, compared with our attention guidance module, which allows adaptive learning of the features for the different layers in the decode path.

Table 4:

With and without attention guidance.

| Without Attention Guidance | With Attention Guidance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC(%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 71.9 (±1.7) | 5.8 (±0.5) | 2.1 (±0.3) | 7.8 (±0.3) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.6 (±0.4) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 6.1 (±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 55.8 (±3.2) | 8.0 (±1.0) | 6.6 (±1.7) | 10.2 (±0.4) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.1) | 9.0 (±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 65.0 (±1.8) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 7.3 (±1.7) | 9.1 (±0.3) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 7.3 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±0.7) | 8.5 (±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 64.4 (±2.6) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 6.3 (±0.8) | 10.4 (±0.4) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 7.4 (±0.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) | 8.2 (±0.4) |

Fig. 10:

Example registration results with and without attention guidance.

4.2.2. Patch Selection Strategy

We compared our difficulty-aware patch selection strategy with uniform and random sampling. The number of patches selected at each iteration during training was kept the same for all sampling schemes. The number was determined by our patch selection strategy (see Section 2.3.2).

Table 5 presents quantitative results in terms of registration accuracy and deformation smoothness. The proposed strategy yields the highest DSCs and the lowest HDs while maintaining deformation smoothness.

Table 5:

The effects of patch selection.

| Random Sampling | Uniform Sampling | Difficulty-aware Sampling | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 71.9 (±1.8) | 5.8 (±0.5) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 7.9 (±0.3) | 72.5 (±1.8) | 5.8 (±0.5) | 2.3 (±0.4) | 8.3(±0.3) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.6 (±0.4) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 6.1 (±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 55.7 (±3.2) | 7.9 (±0.9) | 4.9 (±1.3) | 10.0 (±0.4) | 58.7 (±2.5) | 7.9 (±1.0) | 7.9 (±2.1) | 10.6(±0.4) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.1) | 9.0 (±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 64.5 (±1.8) | 7.5 (±1.0) | 5.4 (±0.9) | 8.8 ±(0.3) | 65.9 (±1.5) | 7.5 (±1.0) | 8.1 (±1.5) | 9.5(±0.3) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 7.3 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±0.7) | 8.5 (±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 64.3 (±2.5) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 5.2 (±0.6) | 10.1 (±0.2) | 65.4 (±2.6) | 7.7 (±0.9) | 8.0 (±1.1) | 10.8(±0.3) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 7.4 (±0.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) | 8.2 (±0.4) |

Fig. 11 shows the convergence time and average DSC over segmentation maps, illustrating the learning curves of the third full-resolution sub-network. The loss curve in the figure shows that our sampling strategy allows the network to converge after ~100k iterations, whereas uniform and random sampling strategies require almost double the number of iterations (~200k) to converge. It is also evident from the figure that our sampling strategy is more stable over iterations.

Fig. 11:

Convergence analysis of the training stage of different patch selection techniques in terms of (left) loss and (right) DSC.

4.2.3. Deformation Initialization

We compared registration performance with and without initialization with coarse-scale deformation. Only patches selected via the attention module are passed to the network at the next scale. Table 6 shows that more foldings occur without deformation initialization. Fig. 12 shows that NJD and NGJD increase and DSC and HD decrease without initialization. This demonstrates that coarse-level deformations can provide a more global context that serves as a prior for further fine-scale refinement of the deformation.

Table 6:

Registration with and without deformation initialization.

| Without Initialization | With Initialization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | DSC (%) | HD (mm) | NJD (%) | NGJD (10−2) | |

| LONI40 | 72.9 (±1.7) | 5.7 (±0.5) | 3.4 (±0.5) | 9.0 (±0.3) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.6 (±0.4) | 1.8 (±0.3) | 6.1 (±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 57.3 (±3.1) | 7.7 (±1.0) | 8.8 (±2.0) | 11.2 (±0.6) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 4.6 (±0.1) | 9.0 (±0.6) |

| CUMC12 | 66.7 (±1.9) | 7.4 (±1.0) | 9.4 (±1.4) | 10.4 (±0.3) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 7.3 (±1.0) | 4.9 (±0.7) | 8.5 (±0.3) |

| MGH10 | 65.6 (±2.6) | 7.6 (±0.9) | 10.0 (±1.5) | 11.9 (±0.4) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 7.4 (±0.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) | 8.2 (±0.4) |

Fig. 12:

Registration with and without deformation initialization.

4.2.4. Coarse-to-Fine Refinement

To demonstrate that the multi-scale framework improves registration accuracy, Table 7 shows the DSCs achieved at different scales. Fig. 13 shows that the deformation field obtained at the fine-scale captures deformations that are more complex than the coarser scales.

Table 7:

DSCs at the coarse, intermediate, and fine levels.

| Coarse | Intermediate | Fine | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LONI40 | 69.7 (±1.6) | 72.4 (±1.7) | 73.4 (±1.7) |

| IBSR18 | 52.5 (±3.0) | 56.8 (±3.0) | 58.4 (±3.1) |

| CUMC12 | 61.9 (±1.5) | 65.4 (±1.8) | 67.0 (±1.9) |

| MGH10 | 61.7 (±2.5) | 65.2 (±2.5) | 66.1 (±2.5) |

Fig. 13:

Registration at different resolution levels.

4.2.5. Anti-Folding Constraint

To investigate the effects of the anti-folding constraint, we compare two loss functions: (i) Eq. (6) with global smoothness weight α > 0 only and; (ii) Eq. (6) with both global smoothness weight α and adaptive smoothness weight β.

Table 8 shows that the DSCs achieved with and without the dynamic smoothness constraint is comparable but foldings are reduced by a factor of ~1/3 with the constraint. Fig. 14 shows that the deformation field obtained without the constraint shows folding artifacts.

Table 8:

The effects of the dynamic smoothness constraint.

| DSC | NJD (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without β | With β | Without β | With β | |

| LONI40 | 73.2 (±1.6) | 73.4 (±1.7) | 5.7 (±0.8) | 1.8 (±0.3) |

| IBSR18 | 58.4 (±3.0) | 58.4 (±3.1) | 13.6 (±2.6) | 4.6 (±0.1) |

| CUMC12 | 66.3 (±1.9) | 66.1 (±2.5) | 16.1 (±1.9) | 5.5 (±0.7) |

| MGH10 | 67.2 (±1.8) | 67.0 (±1.9) | 14.9 (±2.2) | 4.9 (±0.7) |

Fig. 14:

Registration with and without the dynamic smoothness constraint.

The dynamic smoothness constraint penalizes the deformations that exhibit folding or shearing and leave the deformations at other locations unchanged, therefore maintaining accuracy while greatly reducing deformation irregularity.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we have introduced a multi-scale framework equipped with difficulty-aware patch selection scheme for deformable registration. Our hierarchical framework predicts the deformation field in a multi-scale fashion by fully integrating the global and local contextual information. The deformation field predicted at a coarser-scale helps the subsequent sub-networks in refining the deformation at a finer-scale. Our difficulty-aware module helps the registration network focus on candidate regions that are difficult to align, thus promoting effective recovery of complex deformations. A dynamic smoothness constraint is employed to regularize the deformation field for reducing foldings. Experimental results indicate that our method performs better than conventional and deep learning registration methods both in terms of registration accuracy and deformation regularity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A novel multi-scale registration framework that leverages global and local information for estimation of non-linear deformation fields.

A difficulty-aware module is incorporated to progressively refine the registration of hard-to-register regions.

Sub-networks to progressively refine the deformation from coarse to fine.

A dynamic anti-folding constraint to penalize the voxels that lead to folding and tearing.

Extensive experiments conducted on four public datasets validate that our method improves registration accuracy with better preservation of topology.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH grants (AG053867 and EB008374). Yunzhi Huang was supported by the China Scholarship Council.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Avants B, Epstein C, Grossman M, Gee J, 2008. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: Evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Medical Image Analysis 12, 26–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan G, Zhao A, Sabuncu MR, Guttag J, Dalca AV, 2018. An unsupervised learning model for deformable medical image registration, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 9252–9260. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan G, Zhao A, Sabuncu MR, Guttag J, Dalca AV, 2019. VoxelMorph: A learning framework for deformable medical image registration. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 1–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z, Saberian MJ, Vasconcelos N, 2015. Learning complexity-aware cascades for deep pedestrian detection. 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 3361–3369. [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yang J, Zhang J, Nie D, Kim M, Wang Q, Shen D, 2017. Deformable image registration based on similarity-steered cnn regression, in: Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2017 – 20th International Conference, Proceedings, Springer Verlag; pp. 300–308. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-66182-7_35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yang J, Zhang J, Wang Q, Yap P, Shen D, 2018. Deformable image registration using a cue-aware deep regression network. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 65, 1900–1911. doi: 10.1109/TBME.2018.2822826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Yang Y, Wang J, Xu W, Yuille AL, 2016. Attention to scale: Scale-aware semantic image segmentation, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 3640–3649. [Google Scholar]

- Dalca AV, Balakrishnan G, Guttag J, Sabuncu MR, 2018. Unsupervised learning for fast probabilistic diffeomorphic registration, in: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Springer; pp. 729–738. [Google Scholar]

- Dosovitskiy A, Fischer P, Ilg E, Hausser P, Hazirbas C, Golkov V, Van Der Smagt P, Cremers D, Brox T, 2015. Flownet: Learning optical flow with convolutional networks, in: Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision, pp. 2758–2766. [Google Scholar]

- Eppenhof K, Pluim, J. PW, 2018. Error estimation of deformable image registration of pulmonary ct scans using convolutional neural networks. Journal of Medical Imaging 5, 1. doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.5.2.024003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eppenhof KAJ, Pluim JPW, 2019. Pulmonary ct registration through supervised learning with convolutional neural networks. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 38, 1097–1105. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2018.2878316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan J, Cao X, Yap PT, Shen D, 2019. Birnet: Brain image registration using dual-supervised fully convolutional networks. Medical Image Analysis 54, 193–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Liu J, Tian H, Li Y, Bao Y, Fang Z, Lu H, 2019. Dual attention network for scene segmentation, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 3146–3154. [Google Scholar]

- Girshick R, Donahue J, Darrell T, Malik J, 2014. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Hering A, van Ginneken B, Heldmann S, 2019. mlvirnet: Multilevel variational image registration network, in: International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Springer; pp. 257–265. [Google Scholar]

- Hering A, Heldmann S, 2019. Unsupervised learning for large motion thoracic ct follow-up registration, in: Medical Imaging 2019: Image Processing, International Society for Optics and Photonics; p. 109491B. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Modat M, Gibson E, Ghavami N, Bonmati E, Moore CM, Emberton M, Noble JA, Barratt DC, Vercauteren T, 2018a. Label-driven weakly-supervised learning for multimodal deformable image registration, in: 2018 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI 2018), IEEE; pp. 1070–1074. [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Modat M, Gibson E, Li W, Ghavami N, Bonmati E, Wang G, Bandula S, Moore CM, Emberton M, Ourselin S, Noble JA, Barratt DC, Vercauteren T, 2018b. Weakly-supervised convolutional neural networks for multimodal image registration. Medical Image Analysis 49, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2018.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaderberg M, Simonyan K, Zisserman A, kavukcuoglu k., 2015. Spatial transformer networks, in: Cortes C, Lawrence ND, Lee DD, Sugiyama M, Garnett R (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 28. Curran Associates, Inc., pp. 2017–2025. URL: http://papers.nips.cc/paper/5854-spatial-transformer-networks.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Klein A, Andersson J, Ardekani BA, Ashburner J, Avants B, Chiang MC, Christensen GE, Collins DL, Gee J, Hellier P, Song JH, Jenkinson M, Lepage C, Rueckert D, Thompson P, Vercauteren T, Woods RP, Mann JJ, Parsey RV, 2009. Evaluation of 14 nonlinear deformation algorithms applied to human brain MRI registration. NeuroImage 46, 786–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs J, Delingette H, Mailhé B, Ayache N, Mansi T, 2019. Learning a probabilistic model for diffeomorphic registration. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 38, 2165–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Lin Z, Shen X, Brandt J, Hua G, 2015. A convolutional neural network cascade for face detection, in: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 5325–5334. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7299170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu Z, Luo P, Change Loy C, Tang X, 2017. Not all pixels are equal: Difficulty-aware semantic segmentation via deep layer cascade, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 3193–3202. [Google Scholar]

- Long J, Shelhamer E, Darrell T, 2015. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation, in: 2015 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), pp. 3431–3440. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2015.7298965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzi M, Ayache N, Frisoni GB, Pennec X, (ADNI, A.D.N.I., et al. , 2013. Lcc-demons: a robust and accurate symmetric diffeomorphic registration algorithm. NeuroImage 81, 470–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y.g., Liu P, Shi L, Luo Y, Yi L, Li A, Qin J, Heng PA, Wang D, 2015. Accelerating neuroimage registration through parallel computation of similarity metric. PloS one 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maintz J, Viergever MA, 1998. A survey of medical image registration. Medical Image Analysis 2, 1–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murthy VN, Singh V, Chen T, Manmatha R, Comaniciu D, 2016. Deep decision network for multi-class image classification, in: Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, pp. 2240–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Muyan-Ozcelik P, Owens JD, Xia J, Samant SS, 2008. Fast deformable registration on the gpu: A cuda implementation of demons, in: 2008 International Conference on Computational Sciences and Its Applications, IEEE; pp. 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Xie Z, Shi Y, Wen W, 2019. Difficulty-aware image super resolution via deep adaptive dual-network, in: 2019 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo (ICME), IEEE; pp. 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Ren S, He K, Girshick R, Sun J, 2015. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks, in: Advances in neural information processing systems, pp. 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohé MM, Datar M, Heimann T, Sermesant M, Pennec X, 2017. Svf-net: Learning deformable image registration using shape matching, in: Descoteaux M, Maier-Hein L, Franz A, Jannin P, Collins DL, Duchesne S (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2017, Springer International Publishing, Cham: pp. 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T, 2015. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation, in: Navab N, Hornegger J, Wells WM, Frangi AF (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2015, pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Sokooti H, de Vos B, Berendsen F, Lelieveldt BPF, Išgum I, Staring M, 2017. Nonrigid image registration using multi-scale 3d convolutional neural networks, in: Descoteaux M, Maier-Hein L, Franz A, Jannin P, Collins DL, Duchesne S (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2017, Springer International Publishing, Cham: pp. 232–239. [Google Scholar]

- Sotiras A, Davatzikos C, Paragios N, 2013. Deformable medical image registration: A survey. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 32, 1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirion JP, 1998. Image matching as a diffusion process: an analogy with maxwell’s demons. Medical image analysis 2, 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toshev A, Szegedy C, 2014. Deeppose: Human pose estimation via deep neural networks, in: 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 1653–1660. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2014.214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Bai X, 2010. Auto-context and its application to high-level vision tasks and 3D brain image segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 32, 1744–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani A, Shazeer N, Parmar N, Uszkoreit J, Jones L, Gomez AN, Kaiser L.u., Polosukhin I, 2017. Attention is all you need, in: Guyon I, Luxburg UV, Bengio S, Wallach H, Fergus R, Vishwanathan S, Garnett R (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30. Curran Associates, Inc., pp. 5998–6008. URL: http://papers.nips.cc/paper/7181-attention-is-all-you-need.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Vercauteren T, Pennec X, Malis E, Perchant A, Ayache N, 2007. Insight into efficient image registration techniques and the demons algorithm, in: Biennial International Conference on Information Processing in Medical Imaging, Springer; pp. 495–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercauteren T, Pennec X, Perchant A, Ayache N, 2008. Symmetric logdomain diffeomorphic registration: A demons-based approach, in: International conference on medical image computing and computer-assisted intervention, Springer; pp. 754–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercauteren T, Pennec X, Perchant A, Ayache N, 2009. Diffeomorphic demons: Efficient non-parametric image registration. NeuroImage 45, S61–S72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos BD, Berendsen FF, Viergever MA, Sokooti H, Staring M, Išgum I, 2019a. A deep learning framework for unsupervised affine and deformable image registration. Medical Image Analysis 52, 128–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos BD, Berendsen FF, Viergever MA, Sokooti H, Staring M, Išgum I, 2019b. A deep learning framework for unsupervised affine and deformable image registration. Medical image analysis 52, 128–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos BD, Berendsen FF, Viergever MA, Staring M, Išgum I, 2017. End-to-end unsupervised deformable image registration with a convolutional neural network, in: Cardoso MJ, Arbel T, Carneiro G, Syeda-Mahmood T, Tavares JMR, Moradi M, Bradley A, Greenspan H, Papa JP, Madabhushi A, Nascimento JC, Cardoso JS, Belagiannis V, Lu Z (Eds.), Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support, Springer International Publishing, Cham: pp. 204–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Jiang M, Qian C, Yang S, Li C, Zhang H, Wang X, Tang X, 2017. Residual attention network for image classification, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 3156–3164. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Deng Z, Hu X, Zhu L, Yang X, Xu X, Heng PA, Ni D, 2018. Deep attentional features for prostate segmentation in ultrasound, in: Frangi AF, Schnabel JA, Davatzikos C, Alberola-López C, Fichtinger G (Eds.), Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention - MICCAI 2018, Springer International Publishing, Cham: pp. 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Dou H, Hu X, Zhu L, Zhu L, Yang X, Xu M, Qin J, Heng P, Wang T, Ni D, 2019. Deep attentive features for prostate segmentation in 3d transrectal ultrasound. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 1–1doi: 10.1109/TMI.2019.2913184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Kwitt R, Styner M, Niethammer M, 2017. Quicksilver: Fast predictive image registration - a deep learning approach. NeuroImage 158, 378–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Qi X, Shen X, Shi J, Jia J, 2018. Icnet for real-time semantic segmentation on high-resolution images, in: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y (Eds.), Computer Vision - ECCV 2018, Springer International Publishing, Cham: pp. 418–434. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.