Abstract

Inorganic arsenic (iAs) is one of the most endemic toxicants worldwide and oxidative stress is a key cellular pathway underlying iAs toxicity. Other cellular stress response pathways, such as the unfolded protein response (UPR), are also impacted by iAs exposure, however it is not known how these pathways intersect to cause disease. We optimized the use of zebrafish larvae to identify the relationship between these cellular stress response pathways and arsenic toxicity. We found that the window of iAs susceptibility during zebrafish development corresponds with the development of the liver, and that even a 24-hour exposure can cause lethality if administered to mature larvae, but not to early embryos. Acute exposure of larvae to iAs generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), an antioxidant response, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and UPR activation in the liver. An in vivo assay using transgenic larvae expressing a GFP-tagged secreted glycoprotein in hepatocytes (Tg(fabp10a:Gc-EGFP)) revealed acute iAs exposure selectively decreased expression of Gc-EGFP, indicating that iAs impairs secretory protein folding in the liver. The transcriptional output of UPR activation is preceded by ROS production and activation of genes involved in the oxidative stress response. These studies implicate redox imbalance as the mechanism of iAs-induced ER stress and suggest that crosstalk between these pathways underlie iAs-induced hepatic toxicity.

Keywords: Oxidative Stress, ER stress, Unfolded Protein Response, Arsenic, Zebrafish, Liver

INTRODUCTION

All life on earth exists in a chemically rich environment. Environmental toxicants, both natural and synthetic, exert selective pressures on cellular and physiological systems, favoring processes that mitigate the potential harmful effects of these chemicals. Such cellular stress response pathways include the oxidative stress response, which enhances the endogenous cellular antioxidant capacity, and the responses to mitigate the effects of unfolded proteins in the cytoplasm (i.e. the heat shock response) and in the endoplasmic reticulum (i.e. the unfolded protein response; UPR). These pathways serve to protect cells from stressors that are both exogenous, such as chemical toxicants, and endogenous, such as nutritional overload. However, despite intensive investigation into the mechanisms of activation and role of each of these cellular defense pathways, the functional relationship between them during toxicant exposure is poorly understood.

Animals have evolved in the presence of ubiquitous natural toxicants which are part of the earth’s crust. Among the most concerning and widespread is the metalloid arsenic. Although arsenic has long history as a therapeutic agent in Eastern, traditional and Western medical practice, unintentional and prolonged exposure is associated with adverse health effects (Hoonjan et al., 2018). Hundreds of millions of persons are at risk of exposure to unsafe levels of inorganic arsenic (iAs) through water and food. In many cases, water and food contamination may go unnoticed, posing an insidious risk. Strong data from epidemiological and animal studies have shown that exposure to high levels of arsenic is associated with diabetes, liver disease, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and premature death, and acute to very high levels are lethal (Smith et al., 2000; Naujokas et al., 2013; Kuo et al., 2017). These data place arsenic as the number one chemical on the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry hazardous substance priority lists.

Hepatocytes express high levels of the arsenic methyltransferase (As3mt) (Drobná et al., 2010; Bambino et al., 2018) and thus serve as the primary site of iAs metabolism in vertebrates (Twaddle et al., 2019), making the liver particularly sensitive to iAs toxicity. Studies in animal models, including our own (Bambino et al., 2018), show that iAs causes liver damage and fatty liver when administered as a single toxicant (Santra et al., 2000b; Bali et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2018) and also at subtoxic exposures, which can potentiate fatty liver caused by a high fat diet and other common liver disease etiologies (Arteel et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2011; Majhi et al., 2014; Bambino et al., 2018). This is an important consideration as hepatic toxicity is a potentially serious side effect of therapeutic use of arsenic; one study found that over 40% of patients undergoing arsenic-based therapy for acute promyelocytic leukemia developed hepatotoxicity (Mathews et al., 2006). Since liver damage, fatty liver, fibrosis and cancer are significant health risks faced by animals and humans exposed to iAs (Santra et al., 1999; Santra et al., 2000b; Guha Mazumder et al., 2001; Chen and Ahsan, 2004; Kosanovic et al., 2007; Arteel et al., 2008; Liaw et al., 2008; Liu and Waalkes, 2008; Hao et al., 2013; Frediani et al., 2018), the effects of iAs on liver biology is a serious concern for those inadvertently exposed and those where arsenic is administered as a treatment regimen.

Decades of work on the molecular toxicology of iAs have uncovered a prominent role for oxidative stress as a mechanism of iAs toxicity. Strong evidence from in vivo and in vitro systems have demonstrated that iAs exposure causes oxidative stress through 1. reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated through iAs metabolism, and 2. iAs binding to glutathione (GSH) and increasing levels of glutathione disulfide (GSSG), effectively depleting the endogenous antioxidant reserves (Flora, 2011; Jomova et al., 2011; Xu et al., 2017a). The functional relevance of oxidative stress to iAs-induced toxicity has been demonstrated by many studies in humans and rodents showing protective effects of antioxidants against iAs toxicity (Flora et al., 2007; Fuse et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017a; Mittal et al., 2018; Vineetha et al., 2018). In zebrafish, several studies indicate that oxidative stress is a conserved response to arsenic exposure (Sarkar et al., 2014; Adeyemi et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2015; Fuse et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2019). However, the prevailing paradigm that oxidative stress is the main underlying mechanism of iAs toxicity has overshadowed findings that other cellular pathways, such as the response to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress mediated by the UPR, are impacted by iAs.

The UPR serves as a mechanism to restore cellular homeostasis during ER stress or, if the source of the stress persists, to induce cell death to eliminate cells with a persistent burden of unfolded proteins. The ER maintains an oxidizing environment to counteract the reducing nature of disulfide bond formation that is essential for the proper folding of many membrane and secretory proteins (Benham, 2019). In vertebrate cells with ER stress, activation of one or more of the proximal UPR sensing mechanisms mediated by Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1), PKR-like ER kinase (PERK), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) (Walter and Ron, 2011) induces a transcriptional response that promotes expression of chaperones, quality control systems and proteins that function to ensure redox balance is maintained for efficient protein folding in the ER. This balance is critical for the oxidation of disulfide bonds in nascent proteins, facilitated by the ER resident proteins PDI and EROIa and abundant GSH (Tu and Weissman, 2004; Kim et al., 2012). Therefore, significant perturbation of the redox balance by exposures that cause oxidative stress can lead to unfolded proteins in the ER and activate the UPR.

Chronic activation of the UPR contributes to liver disease in experimental models (Rutkowski, 2018) and has been proposed as a mechanism of toxicant induced liver damage (Young et al., 2018). However, whether ER stress and the UPR underlie the pathophysiology of liver disease caused by arsenic remains to be determined. Studies in a variety of cell types in vitro and in vivo showed that iAs causes ER stress (Naranmandura et al., 2012; Weng et al., 2014; Srivastava et al., 2016a; Srivastava et al., 2016b; Xu et al., 2017b; Dodson et al., 2018), and we showed that zebrafish exposed to iAs throughout development have a transcriptional response reflecting oxidative stress and ER stress (Bambino et al., 2018). A link between these pathways is further supported by elegant studies in C. elegans, human cells (Hourihan et al., 2016) and yeast (Guerra-Moreno et al., 2019) where a surprising novel function of Ire1α was discovered: modification of Ire1α upon oxidative stress converts its function from activating the UPR to promoting an antioxidant response via p38 MAP kinase activation (Hourihan et al., 2016). This suggests that oxidative stress could either cause ER stress or, conversely, could redirect UPR components to augment the antioxidant response. These discoveries compel our investigation into the mechanism of ER stress in the context of arsenic induced toxicity, with a specific focus on the impact on the liver.

Our previous work demonstrated that zebrafish embryos treated with sodium meta-arsenite from 6 hours post fertilization (hpf) until 120 hpf have widespread gene expression changes in the liver reflecting xenobiotic metabolism, ER and oxidative stress (Bambino et al., 2018). Given the important contribution of ER stress and UPR activation to liver disease in other contexts, it is of interest to identify the mechanism of ER stress in response to iAs and to uncover the contribution of this pathway to iAs toxicity. Here, we test the hypothesis that iAs-induced ER stress in the liver is attributed to the pro-oxidant effects of iAs by carrying out a detailed analysis of the response of zebrafish embryos and larvae to acute (96-120 hpf) and chronic (6-120 hpf) iAs exposure and then assess how acute exposure impacts the oxidative stress and ER stress responses in the liver.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Zebrafish husbandry and embryo rearing

All procedures were approved by and performed in accordance with the New York University Abu Dhabi Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines. Adult wild type (WT; ABNYU, TAB5, and BNY14) and transgenic lines (Tg(fabp10a:nls-mCherry) and Tg(fabp10a:Gc-EGFP)) were maintained on a 14:10 light:dark cycle at 28 °C. All experiments were conducted in 6-well plates (Corning, USA) with 20 embryos in 10 mL rearing medium. Embryos were collected from group matings or single mating pairs, as indicated, within 2 hours of spawning and were reared at 28 °C according to standard conditions (Westerfield, 2000).

All experiments were carried out with embryos and larvae reared in embryo medium, unless indicated. The working solution of embryo medium was prepared fresh weekly, to a final concentration of: 13.7 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM KCl, 0.025 mM Na2HPO4, 0.044 mM KH2PO4, 3 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgSO4.7H2O, and 4 mM NaHCO3. Where indicated, egg water was used for rearing, which was prepared from a stock solution made up of 40 g Instant Ocean Salts (CrystalSea Marinemix) in 1 L RO water and a working solution was prepared from 1.5 mL stock per 1 L RO water.

Embryo exposure

Embryos were exposed to sodium meta-arsenite (Sigma-Aldrich,USA; heretofore referred to as iAs) by diluting 0.05 M stock solution to final concentrations ranging from 0.01 μM - 4 mM in embryo medium. For addition experiments, 2.0 mM of iAs was added to embryos at 6, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hpf. For subtraction experiments, 2.0 mM iAs was added at 6 hpf and removed at 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 hpf by transferring embryos in 10 mL of fresh embryo medium twice. Interval exposures were conducted every 24-hour ranges, 6-30, 24-48, 48-72, 72-96 and 96-120 hpf at the indicated concentration of iAs. For all experiments, mortality was scored daily, dead embryos were removed upon identification, and morphology was recorded at 120 hpf as readout of iAs toxicity.

To test for synergy between iAs and H2O2, embryos were first exposed to 1 mM iAs from 72-96 hpf, were washed three times and replaced with fresh embryo medium, then 0.001% or 0.005% H2O2 was added from 96-120 hpf. Survival was assessed at 120 hpf in comparison to untreated larvae or larvae treated with either iAs or H2O2 as controls.

Image Acquisition

For whole mount imaging of live larvae, embryos were anesthetized with 500 μM tricaine (Ethyl 3-aminobenzoate methanesulfonate; Sigma-Aldrich), mounted in 3% methyl-cellulose on a glass slide and imaged on a Nikon SMZ25 stereomicroscope.

Live Imaging of transgenic Tg(fabp10:Gc-EGFP) was carried out in live 120 hpf larvae treated as described. Prior to imaging, iAs was washed out and 5 larvae were transferred to 0.17 mm imaging plates (FluoroDish) and were embedded in 1% low melt agarose gel (SeaPlaque Agarose, Lonza) containing 500 μM tricaine. A hair loop was used to embed and orient larvae with their left lateral side facing downward. After complete gel polymerization, the gel was covered with 500 μM tricaine in embryo medium and images were acquired using a Leica SP8 inverted confocal microscope with 63X water lens in the NYUAD Core Technology Platform. Time-lapse imaging was done on samples prepared as described above with laser power settings ranging 5-10% and temporal resolution as indicated in legends. Imaris was used to process all images and movies.

Western Blotting

Transgenic Tg(fabp10:Gc-EGFP) were treated as described and 5 livers were collected as pools at 120 hpf into 100 μL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% v/v NP-40, 10% v/v glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 2X protease inhibitors), sonicated and centrifuged. The supernatant was prepared in Laemmli buffer and boiled at 95 °C for 5 minutes. Samples were electroporated on an 8% gel for 1 hour at 100 V and transferred onto a PVDF membrane at 300 mA for 3 hours, blocked with 5% milk in TBST (1X TBS with 0.1% Tween-20) followed by incubation with rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Abcam-ab290), mouse anti-mCherry and rabbit anti-H3 antibodies (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, 10809) overnight. Secondary antibodies used were antirabbit HRP (1:2000;Promega; W401B) and anti-mouse HRP (1:2000; Promega; W402B). Development was performed in BioRad ChemiDoc with ECL Thermo-Pierce (Low sensitivity reagent), or ECL Clarity BioRad (Mid sensitivity reagent), or ECL Select Amersham-GE Healthcare Systems (High sensitivity reagent). Band intensity was quantified using GelAnalyzer software.

Gene Expression Analysis

Pools of at least 10 livers were microdissected from 120 hpf zebrafish larvae with transgenic marked livers (Tg(fabp10a:DsRed, ela: eGFP)) or (Tg(fabp10a:Caax-eGFP)). Larvae were anesthetized in tricaine and immobilized in 3% methyl cellulose and the livers were removed using 30-gauge needles. RNA was extracted from livers using TRIzol (Thermo Fisher, 15596026) and precipitated with isopropanol as described (Vacaru et al., 2014). RNA was reverse-transcribed with qScript (QuantaBio, 95048-025).

Gene expression was assessed using RNAseq or quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR was performed using Maxima Sybr Green/ROX qPCR Master Mix Super Mix (Thermo Fisher, K0221). Samples were analyzed in triplicate on QuantStudio 5 (Thermo Fisher). Target gene expression was normalized to ribosomal protein large P0 (rplp0) using the comparative threshold cycle (ΔCt) method. Expression in treated animals was compared to untreated controls from the same clutch to determine fold change. Primer sequences are listed in Table S4. RNAseq analysis used a previously generated dataset (Bambino et al., 2018) Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) access number GSE104953 with reads aligned to the Danio rerio GRCz10 reference genome. To curate putative transcript factor target lists, the 2016 Marbach database was accessed using the R package tftargets (Marbach et al., 2016). All code and R-packages used for analysis are provided in GITHUB.

ROS Assay

iAs-induced ROS level changes were determined with the use of 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA; Invitrogen). Medium from treated and control (untreated) larvae was placed in culture media containing 5 uM of CM-H2DCFDA for 90 minutes. Additionally, “blank” samples were prepared which contains the incubation solution (embryo medium with or without 1.5 mM iAs) without larvae. Fifty μL of blanks, untreated controls and treated solutions were loaded onto 96 well plates in 5 technical replicates. The fluorescence of each well was determined using Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Reader (BioTek), 485 nm and 538 nm emission (bottom read). To calculate the ROS ratio, the mean of the control untreated fish was subtracted from the mean of the blank. In parallel, the mean of the 1.5 mM treated fish was subtracted from the mean of the 1.5 mM iAs blank. Finally, ratio of the adjusted treated over the adjusted treated was taken.

Xbp1 Splicing

PCR reactions (20 μl total) contained 0.25% of the cDNA reaction, 1× buffer, 0.2 μM dNTPs, 0.5 μL Taq polymerase (Invitrogen) and 0.4 μM of each primer, and the reaction was carried out for 32 cycles. Primer sequences are listed in Table S4. PCR products were electroporated on a 4% agarose gel containing 1 μg/mL ethidium bromide for approximately 1 hour at 120 V. Band intensity was quantified using GelAnalyzer software.

Statistical analysis, rigor and reproducibility

All experiments were repeated on at least 2 clutches of embryos when possible, with all replicates indicated. Reproducibility was assured by carrying phenotype scoring and other key experiments by independent investigators. Data are presented as normalized values and, where appropriate, raw data is provided. Statistical tests were used as appropriate to the specific analysis, including Student’s T-test, ANOVA and Chi Square (Fisher’s exact test) using Graphpad Prism Software. P-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant in our analysis.

RESULTS

iAs toxicity in zebrafish is independent of genetic background and microbiome

To expand on previous work establishing zebrafish larvae as an effective model system to study the cellular basis of iAs toxicity (Li et al., 2009; Hamdi et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2015; Fuse et al., 2016; Beaver et al., 2017; Bambino et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019; Valles et al., 2020), we examined the genetic strain, culture condition and the microbiome as potential confounding factors that might influence iAs susceptibility in this system. We used mortality and morphological abnormalities as indicators of systemic iAs toxicity.

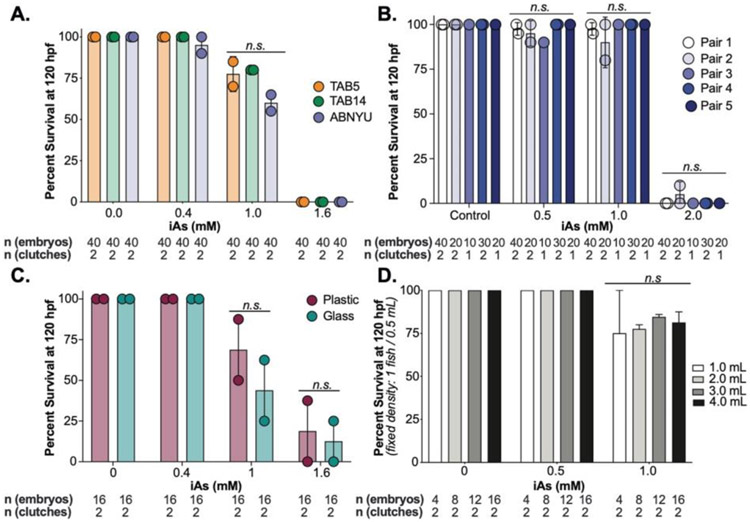

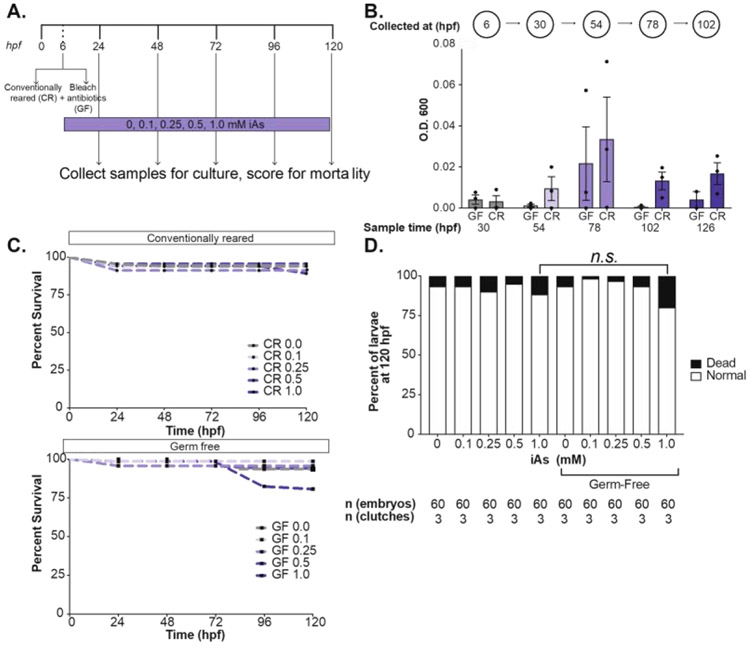

In previous studies we used a chronic treatment model whereby embryos were exposed to iAs throughout development. We used this exposure scheme to test experimental parameters that could potentially influence susceptibility to iAs concentrations ranging from 0.4-2 mM from 6-120 hours post fertilization (hpf) by measuring mortality and morphological changes. We use the inbred strains TAB5, TAB14 and the AB strain (called ABNYU in our facility) and found that embryos from these different genetic backgrounds did not differ in their susceptibility to iAs when we assessed the offspring of group matings (Figure 1A) nor when we compared offspring from mating single pairs of ABNYU adults (Figure 1B). This suggests that in zebrafish, iAs toxicity is consistent across these genetic backgrounds. Plastics can interact with some toxicants, but we found no difference in the response of embryos cultured in plastic or glass containers to iAs (Figure 1C). Since gas distribution can fluctuate based on the surface area of the media and animal density, we tested the effects of culture volume on iAs susceptibility by adjusting the volume of the culture media. Using a multi-well plate with a fixed density of 2 larvae per mL rearing medium, we altered the surface area/volume ratio, but found no difference in mortality across these conditions (Figure 1D). Finally, as one study showed iAs can alter the microbiome of zebrafish (Dahan et al., 2018), and we asked whether the microbiome influenced iAs toxicity by comparing embryos reared in conventional vs. germ free conditions (Milligan-Myhre et al., 2011) (Figure 2A-B). There was no significant difference in systemic iAs toxicity between germ-free and conventionally reared siblings (Figure 2C-D).

Figure 1. iAs induced toxicity in zebrafish is independent of genetic background, plastic interactions, and volume.

A. Survival of zebrafish from TAB5 (orange), TAB14 (green) and ABNYU (blue) genetic background at 120 hpf after treatment from 6-120 hpf with 0, 0.4, 1.0 and 1.6 mM of iAs. Dots represent individual clutch values and bars indicate the mean between multiple clutches, n.s. indicates not significance, 2-way ANOVA. B. Survival analysis of single pairs of ABNYU zebrafish pairs treated with iAs (0 – 2.0 mM). No single pair exhibited resistance or sensitivity to iAs (n.s. = not significant per 2-way ANOVA). C. Survival analysis of zebrafish reared in plastic (maroon) and glass (teal) containers. n.s. indicates not significant by 2-way ANOVA. D. Survival analysis of zebrafish reared in a fixed density (1 fish/0.5 mL) in volumes ranging from 1-4 mL and exposure to iAs (6-120 hpf, 0-1 mM). n.s. indicates not significant, 2-way ANOVA. All experiments were performed in egg water. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM).

Figure 2. iAs toxicity is independent of microbiome.

A. Schematic of germ-free treatment strategy, whereby embryos were split at 6 hpf and bleached in either antibiotic embryo medium or conventional embryo medium before treatment with 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 mM iAs from 6-120 hpf. (CR: Conventionally-Reared, GF: Germ- Free). B. Spectrophotometer measurement of bacterial density (OD600) in each medium each day. C. Survival analysis of zebrafish treated with iAs as outlined in A. Fish were scored daily for mortality (n= 60, 3 clutches). D. Weighted average of percent of death and normal larvae per treatment condition (n= 60, 3 clutches). All experiments were performed in egg water. Error bars represent SEM.

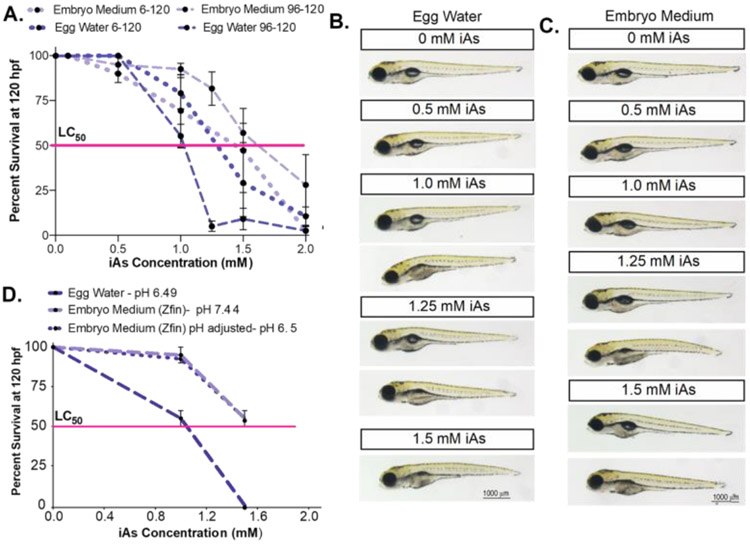

Zebrafish embryo mortality caused by iAs is altered by culture media

Next, we assessed whether the media in which the embryos are cultured affects iAs toxicity. There are two commonly used formulae for zebrafish embryo rearing medium during the first five days post fertilization (dpf) (Westerfield, 2000). One is “egg water,” a simple solution of reverse osmosis (RO) water and dehydrated ocean salts. The other is “embryo medium,” which includes calcium and magnesium salts, and a buffer with the pH adjusted 7.4. We tested the effect of these two mediums on iAs susceptibility in response to the chronic treatment described above and acute exposure from 96-120 hpf (Figure 3A). While untreated embryos reared in either media are indistinguishable (Figure 3B), embryos are more susceptible to iAs toxicity in egg water, where the lethal concentration at which 50% of larvae die (LC50) during chronic exposure is 1.25 mM iAs approximately, but is 1.5 mM iAs for those in embryo medium (Figure 3A). A robust difference was observed during the acute exposure to iAs, where the LC50 in egg water is 1 mM but is increased to 1.5 mM in embryo medium (Figure 3A). Interestingly, this study also showed that iAs is more toxic when administered later to embryos than those chronically exposed in egg water. However, in embryo medium, chronic exposure is more toxic to zebrafish embryos than acute exposure. We also observed that in both culture media, the elements of the phenotypes elicited by iAs did not differ in those that survived exposure, however, the number of embryos displaying these phenotypes was reduced in embryo medium (Figure 3B-C). This signifies that, although the embryo rearing medium changes the potency of iAs, the mechanistic basis of the cellular response to this toxicant is likely the same in both rearing media.

Figure 3. iAs toxicity is dependent on the rearing medium but independent of pH changes.

A. Survival curve of zebrafish larvae reared in embryo medium (pH 7.4, + Ca and Mg) or egg water (not buffered, mix of ocean salts) exposed to iAs (0-2.0 mM) from 6-120 hpf and 96-120 hpf. Pink line indicates the lethal concentration that causes 50% death (LC50). (n = 2-4 clutches, 20 fish per clutch) B & C. Representative images of zebrafish at 120 hpf reared in egg water (B) or embryo medium (C) and exposed to different concentrations of iAs. D. Survival curve of zebrafish larvae reared in egg water (pH 6.49), embryo medium (pH 7.4) or embryo medium with pH adjusted (pH 6.49) exposed to iAs (0-1.5 mM) from 96-120 hpf. Pink line indicates the lethal concentration that causes 50% death (LC50).(n = 2 clutches, 20 fish per clutch). Error bars represent SEM.

The pH of egg water and embryo medium are 6.49 and 7.44 respectively, and given that iAs speciation is sensitive to pH (Smedley and Kinniburgh, 2002), we assessed whether the observed difference in iAs toxicity in the two mediums were attributed to pH by generating embryo medium with pH 6.5. We found no difference in larval lethality compared to standard embryo medium at pH 7.44 in response to acute (96-120 hpf) iAs challenge (Figure 3D). This suggests that some feature other than the neutral pH of the embryo medium accounts for the higher tolerance of iAs. In summary, these studies optimize the treatment scheme for iAs exposure in zebrafish larvae where multiple confounding factors are controlled and provide a robust system for experiments addressing mechanisms of iAs toxicity in the liver. Henceforth, all experiments were carried out in conventionally reared embryos at 2 embryos/mL in plastic multi-well plates in embryo medium at pH 7.44 (unless otherwise specified).

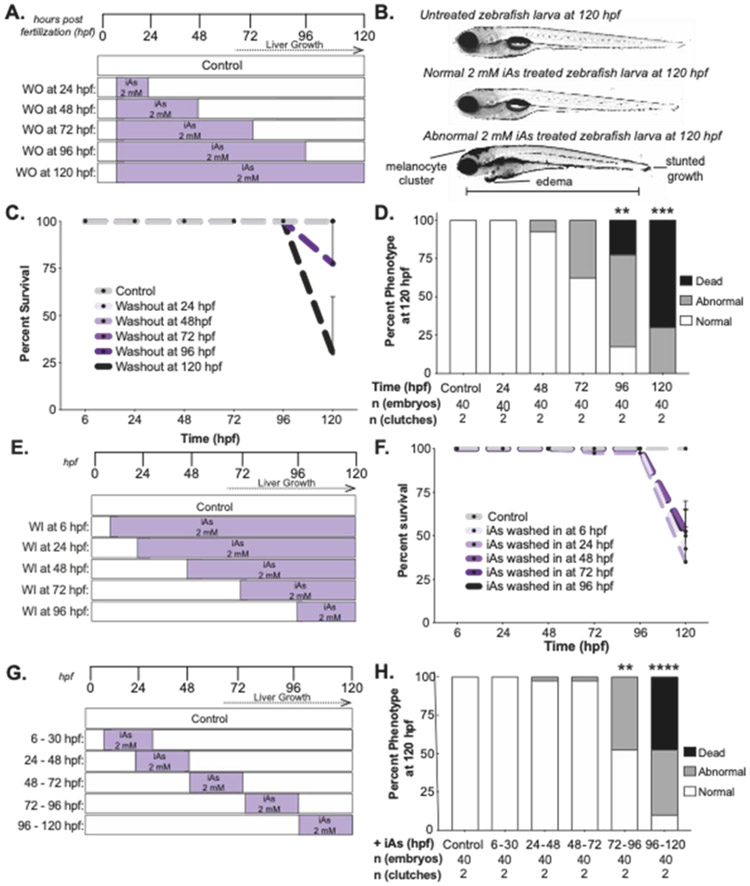

Zebrafish larvae at later developmental stages are more susceptible to iAs toxicity compared to early embryos

To determine the window of iAs susceptibility during development, “addition/subtraction” experiments were carried out (Figure 4) whereby iAs was added or removed sequentially across the developmental stages encompassing gastrulation (6 hpf) to full larval maturity (120 hpf). Larvae were scored at 120 hpf for mortality and morphological defects. Data from individual experiments are summarized in Table S1. For ease of comparison, we selected 2 mM iAs as the standard concentration in this series of experiments since this exceeded the LC50 for the acute exposure protocol and is the approximate LC50 for the chronic protocol (Figure 3A). For the subtraction experiments, 2 mM iAs was added to 6 hpf embryos and then removed at 24, 48, 72 or 96 hpf (Figure 4A). Surviving larvae were scored for morphological abnormalities including cranial melanocyte clusters, edema and stunted growth (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Larval recovery from iAs treatment is decreased after liver bud formation.

A. iAs washout (WO) treatment strategy, whereby all embryos are treated with 2 mM iAs at 6 hpf and iAs is washed out at 24-hour intervals. Animals were monitored until 120 hpf. B. Brightfield images of representative untreated control larvae and those exposed to 2 mM iAs from 6-120 hpf. Scale bar represents 3100 μm. C. Survival of zebrafish treated with iAs as outlined in A. Embryos were scored daily for mortality (n= 40, 2 clutches). Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). D. Weighted average of percent of death, abnormal and normal larvae per treatment condition (n= 40, 2 clutches). ** and *** indicates p-value <0.005 and <0.0005, 2-way ANOVA. E. iAs wash in (WI) treatment strategy, whereby 2 mM iAs was added at 24-hour intervals and retained in the culture media until 120 hpf. F. Survival of larvae treated with iAs as outlined in E. Larvae were scored daily for mortality (n= 40, 2 clutches). Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). G. iAs treatment scheme to determine the developmental window of toxicity by 24-hour interval exposure. H. Weighted average of percent of death, abnormal and normal larvae per treatment interval (n= 40, 2 clutches). ** and **** indicates p-value <0.005 and p-value <0.0001, 2-way ANOVA.

Melanocyte clustering provided a quick and reliable phenotype for sorting embryos, and we further explored the cellular basis for this effect. Zebrafish can redistribute melanosomes to camouflage with their environment (Mizusawa et al., 2018) and we found that, as predicted, melanocytes expanded in untreated larvae kept in the dark and then contracted upon exposure to bright light (Figure S1A). In contrast, iAs-treated larvae retain the same expanded pigmentation pattern (Figure S1A-B), suggesting that iAs does not affect melanocyte development but instead impairs melanosome intracellular distribution, during both dark and light exposure of the skin. Although 2 mM is substantially higher than concentrations humans are exposed to, chronic, low dose exposure to arsenic in humans leads to similar pigmentation defects (Wei et al., 2018).

Exposure to toxicants that directly impair key cellular processes or those causing genomic instability typically causes death during acute exposure, as we recently reported with zebrafish embryos exposed to metals configured in trefoil knots (Benyettou et al., 2019). In contrast, most death in response to iAs exposure occurred between 96-120 hpf, regardless of the time of administration or removal of iAs (Figure 4C, F). This shows that iAs toxicity in zebrafish larvae is not a consequence of a developmental abnormality or cumulative effects. Instead, we concluded that some feature of mature larvae renders them hypersensitive to iAs. This is supported by the finding that 2 mM iAs exposure caused death and morphological abnormalities even if iAs was removed after 96 hpf (Figure 4D). A simple interpretation of this subtraction experiment is that toxicity is directly related to duration of the exposure. To test this, we carried out an addition experiment whereby iAs exposure started at 6, 24, 48, 72 or 96 hours and maintained in the water until 120 hpf (Figure 4E). There was death of nearly all larvae in all treatment groups by 120 hpf, even if the exposure duration was as short as 24 hours (Figure 4F). This shows that a concentration of iAs that is lethal in older larvae is well tolerated by early embryos and demonstrate that the window of iAs susceptibility occurs after 72 hpf. Thus, the phenotypic effects of iAs observed in embryos chronically exposed to iAs are not likely to be caused by the developmental effects of exposure, but instead we attributed these to the effects of iAs on tissues or cell types present at later developmental stages.

iAs metabolism largely occurs in hepatocytes, the primary site of arsenite methyltransferase (as3mt) expression in zebrafish (Bambino et al., 2018). If iAs toxicity is mediated by metabolism in hepatocytes, then iAs would be less toxic to embryos prior to the stage of liver development. We tested this by adding 2 mM iAs to individual cohorts of embryos for 24-hour intervals starting at 6, 24, 48, 72 and 96 hpf and monitored for morphological defects and mortality at 120 hpf (Figure 4G). iAs treatment from 96-120 hpf was the most toxic exposure interval (Figure 4H), and these results were consistent between clutches (Table S1C). These experiments demonstrate that toxicity during chronic exposure of zebrafish embryo development is largely due to effects sustained during the latter part of the exposure. Notably, this is the developmental time that correlates with the formation of mature hepatocytes (Chu and Sadler, 2009), and expression of as3mt (Bambino et al., 2018). These data are consistent with the hypothesis that iAs toxicity is enhanced by the presence of a mature liver and are consistent with findings in humans and other animal models showing that iAs is a hepatotoxicant (Santra et al., 1999; Mazumder, 2005; Tan et al., 2011; Nain and Smits, 2012; Hao et al., 2013). However, this coincidental finding does not exclude the possibility that other structures that develop at the same developmental stage as the liver could also contribute to iAs toxicity.

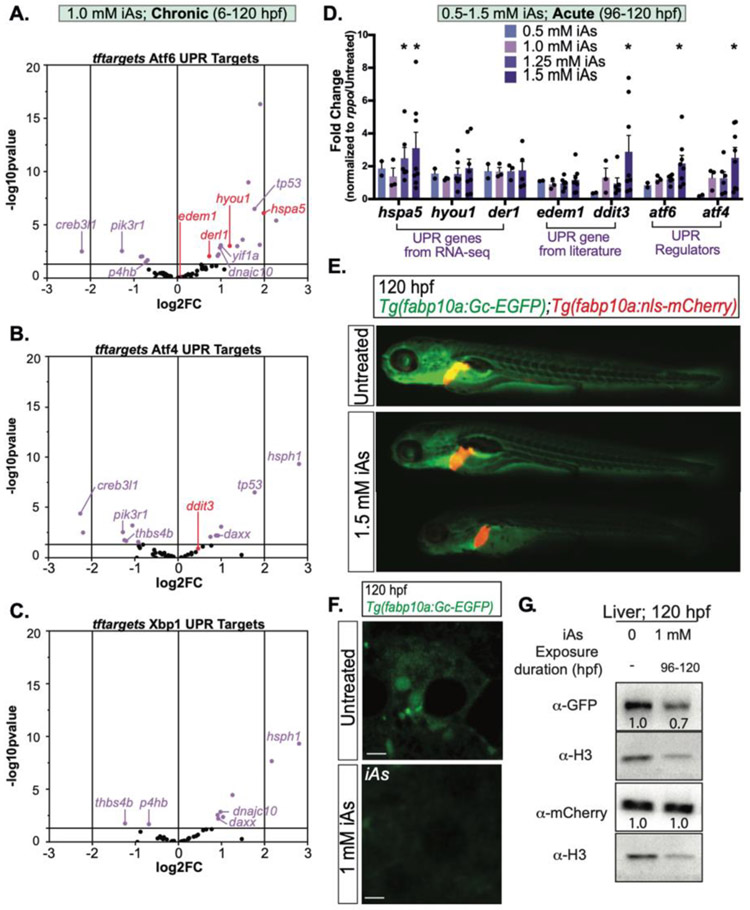

iAs treatment induces ER stress in zebrafish livers

Our previous work uncovered a unique gene expression pattern reflecting both an oxidative stress response and UPR activation based on RNAseq analysis of the liver of zebrafish larvae chronically exposed to 1 mM iAs (Bambino et al., 2018). We analyzed this RNAseq dataset to determine whether there was a specific UPR pathway preferentially activated. The UPR transcriptional response is largely mediated by the transcription factors Atf6, Atf4, and Xbp1 (Walter and Ron, 2011). We used the R package, tftargets (Marbach et al., 2016) to curate lists of putative targets of each of these, generating 996 potential target genes for Atf6, 2,347 for Atf4 and 1,998 for Xbp1 To focus on the target genes that play a role in the UPR, we filtered each geneset for those with gene ontology (GO) classification of UPR or ER stress (357 genes; Table S2A). This generated a UPR target specific list for each transcription factor, with 68 Atf6 targets, 44 Atf4 targets and 23 Xbp1 targets (Table S2B). We found that 29% of Atf6, 31% of Atf4 and 24% of Xbp1 targets were significantly differentially expressed (adjusted p-value < 0.05). The extensive crosstalk between pathways resulted in some genes being included on multiple lists (labeled genes in Figure 5A-C). Filtering for unique genes on each list revealed that 21%, 18% and 10% of Atf6, Atf4 and Xbp1 unique UPR target genes, respectively, were differentially expressed in the liver in larvae chronically exposed to iAs. These factors are commonly viewed as transcriptional activators and we found a trend towards upregulation of these targets for all branches, but we note that there were also UPR targets which were downregulated in each dataset, consistent with other studies (Erguler et al., 2013; Howarth et al., 2014; Bambino et al., 2018; Diedrichs et al., 2018). Notably, only 9 out of the 38 Xbp1 target genes were significantly differentially expressed, and, of these, only 4 are unique to the Ire1α /Xbp1 branch, suggesting that in zebrafish, iAs might also suppress Ire1α function in the UPR, as found in other species (Hourihan et al., 2016; Guerra-Moreno et al., 2019).

Figure 5. iAs treatment induces ER stress in zebrafish livers.

A-C. Expression of UPR genes that are putative targets of Atf6 (A), Atf4 (B) and Xbp1 (C) based on RNA-seq of zebrafish larval livers treated from 6-120 hpf with 1 mM iAs. Target lists were derived from R package tftargets. Purple dots indicate p-value <0.05. D. UPR gene expression derived from qPCR analysis on pools of 5 larval zebrafish livers per clutch treated with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.25, and 1.5 mM iAs from 96-120 hpf. Each black dot indicates mean value per clutch. * p-value <0.05, determined by two-tailed, one-sided t-test on dCt values. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). E. Representative images of 120 hpf larvae expressing both Gc-GFP and nuclear localized mCherry under a hepatocyte specific promoter (Tg(fabp10a: Gc-EGFP;fabp10a:nls-mCherry)). Larvae were treated with 1.5 mM iAs from 96-120 hpf. F. Confocal images of hepatocytes from Tg(fabp10a:Gc-EGFP) larvae that were untreated (top) or treated with 1 mM iAs from 96 – 120 hpf in egg water. Scale bar is 3 μm. G. Western blot of GFP, mCherry and H3 (control) in the livers of 120 hpf Tg(fabp10a: Gc-EGFP;fabp10a:nls-mCherry) larvae exposed to 1 mM iAs in egg water from 96-120 hpf compared to untreated siblings.

To determine if acute iAs exposure (96-120 hpf) also caused UPR activation, qPCR analysis of liver samples exposed to multiple doses of iAs (0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.25, and 1.5 mM) was carried out. A panel of UPR targets that were significantly changed in response to chronic iAs exposure (hspa5, hyou1, derl1), other known UPR targets from the literature (edem1 and ddit3) or key UPR regulators (atf4 and atf6; xbp1 was not significantly changed in the liver of larvae exposed to chronic iAs; Table S2B) were selected for analysis. Of these, hspa5, ddit3, atf6 and atf4 were significantly induced in the liver in response to acute 1.5 mM iAs exposure (Figure 5D). Notably, two of these (ddit3 and atf4) were not induced by chronic exposure. This suggests that acute exposure may cause a different stress response in the liver compared to that during chronic exposure, where hepatocytes may adapt to the stress.

During ER stress, secretory proteins are either retained in the ER or degraded. To understand the outcome of iAs-induced ER stress on protein folding and secretion, we used the transgenic zebrafish line that expresses a GFP-tagged glycoprotein (group complement [Gc], also called vitamin D–binding protein) under a hepatocyte-specific promoter (Tg(fabp10a:Gc-EGFP) (Xie et al., 2010; Howarth et al., 2013). Comparing Gc-EGFP to a non-secreted transgene (i.e. nuclear localized mCherry in Tg(fabp10a:nls-mCherry)), enabled monitoring of secretory protein fate as an in vivo assay for ER stress. Untreated larvae expressing both transgenes (i.e. Tg((fabp10a:nls-mCherry);(fabp10a:Gc-EGFP)) showed intense EGFP signal in the vasculature and in the liver reflecting the secretion of this protein from hepatocytes into circulation (Figure 5E). Acute (96-120 hpf) exposure to 1.5 mM iAs caused dramatic decrease of EGFP fluorescence in the vasculature and liver. In contrast, high expression of nls-mCherry was detected (Figure 2E). In vivo imaging of Gc-EGFP confirmed that there was dramatic reduction in EGFP levels in hepatocytes (Figure 5F, Movie1_Untreated (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BROQl455o-s) and Movie2_iAs-A (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HS3gCYlp7ZA) shows live confocal images and time lapse series taken with the same laser power). Western blotting of liver extracts to quantify the levels of EGFP and mCherry relative to histone H3 showed that acute iAs treatment (1 mM in egg water; 96-120 hpf) caused a marked reduction of Gc-EGFP while nls-mCherry in comparison showed no difference in relative expression (Figure 5G). Importantly, no significant reduction of gc-egfp or nls-mCherry mRNA was observed via qPCR, indicating that iAs challenge largely affects translation rather than transcription (Figure S2). Together, these data indicate that acute iAs treatment induces ER stress in hepatocytes which affects the folding and stability of secretory cargo.

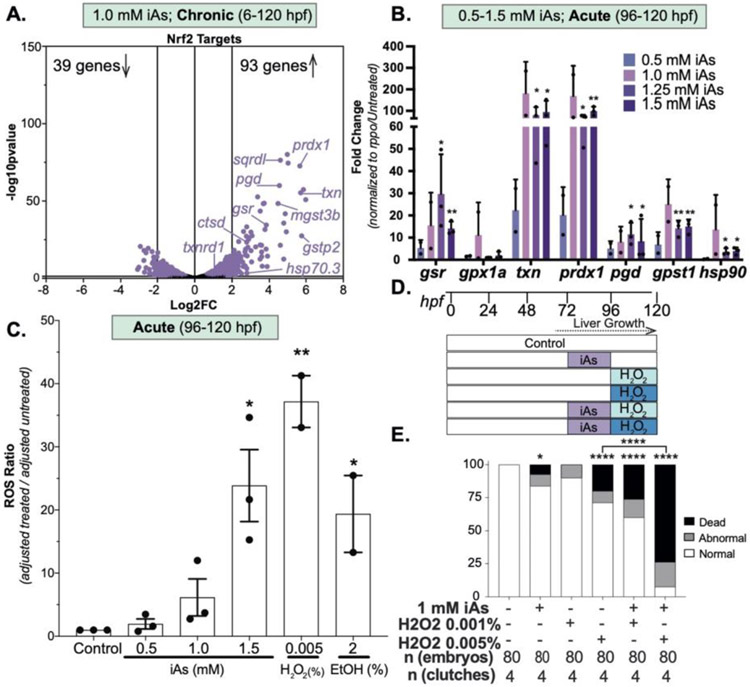

iAs induces oxidative stress in zebrafish

We asked whether iAs treatment induced an oxidative stress response in zebrafish livers. Nrf2, the primary regulator of the transcriptional response to oxidative stress, is activated in response to arsenic (Srivastava et al., 2013; Fuse et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2019), and is essential for arsenic toxicity in zebrafish (Fuse et al., 2016). We utilized tftargets to curate a list of 4,161 potential Nrf2 target genes in zebrafish. Of these, 3,122 were expressed in the liver, with 93 significantly upregulated and 39 significantly downregulated (adjusted p-value < 0.05 and Log2FC > 2 or < −2; Figure 6A). Importantly, genes that are essential for the oxidative stress response (sqrdl, pgd, txn, mgst3b, ctsd, gstp2, gsr and hsp70.3) and have been shown to be highly responsive to pro-oxidants in zebrafish (Hahn et al., 2014), were all upregulated in response to chronic exposure of iAs (Figure 6A). We examined a subset of these by qPCR (gsr, gpx1a, txn, prdx1 pgd, gpst1 and hsp90) in livers of larvae exposed to acute iAs and found all but gpx1a to be significantly upregulated by 1.0 and 1.5 mM iAs exposure (Figure 6B). This indicates that, as predicted, iAs activates the Nrf2 mediated oxidative stress response pathway in the liver. To assess the effects of iAs on ROS generation directly, we measured reactive oxygen species using CM-H2DCFDA, a dye that is nonfluorescent in its reduced form but becomes fluorescent upon oxidation. As a positive control, larvae were treated with 0.005% H2O2 and 2% ethanol (EtOH) from 96-120 hpf. ROS levels increased with acute iAs challenge in a dose dependent manner, reaching significance at 1.5 mM (Figure 6C). This demonstrates that acute iAs challenge causes ROS production, activating an oxidative stress response.

Figure 6.

iAs treatment induces the oxidative stress response in zebrafish livers. A. Gene expression of Nrf2 putative targets derived from R package tftargets. Well characterized Nrf2 targets are indicated. Each dot indicates an individual gene based on RNAseq from zebrafish larval livers treated from 6 to 120 hpf with 1 mM iAs. Purple dots indicate p-value <0.05. B. Oxidative stress gene expression derived from qPCR analysis on pools of 5 larval zebrafish livers treated with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.25 and 1.5 mM iAs from 96 to 120 hpf per clutch. Each bar indicates mean value across clutches. * p-value <0.05 and ** p-value <0.005 determined by two-tailed, one-sided t-test on dCt values Error bars represent the SEM. C. Samples were treated with 0, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 mM iAs, or 0.005% H2O2 or 2% ethanol from 96 to 120 hpf. Ratio of treated:controls, with blank values subtracted are displayed, with the bar marking the median values from 2 to 3 clutches (20 fish per condition); error bars indicating the SEM. * and ** indicate p-value <0.05 and <0.005 by Student’s t-test. D. iAs preatment strategy, whereby 1 mM iAs is added to the larvae culture from 72 to 96 hpf, washed out at 96 hpf and a subset were treated with H2O2 from 96 to 120 hpf. All conditions are scored at 120 hpf and carried out using egg water. E. Weighted average of percent of death, abnormal and normal larvae per treatment condition (n = 40, 2 clutches). * and **** indicate p-value <0.05 and <0.0001, Fisher’s exact test.

If iAs induced oxidative stress was a factor in toxicity in this model, then iAs should sensitize larvae to an H2O2 challenge. To test this, we used pre-treatment strategy whereby iAs was completely washed out prior to H2O2 challenge to circumvent any possible interaction between iAs and H2O2 in solution. Larvae from the same clutch were divided into the groups as untreated controls, exposed to 1 mM iAs from 72-96 hpf, exposed to 0.001% or 0.005% H2O2 from 96-120 hpf or combination of iAs (72-96 hpf) followed by H2O2 (Figure 6D). This revealed a synergistic response to iAs and H2O2 based both on morphological defects and mortality (Figure 6D), a result that was highly reproducible between clutches (Table S3). This suggests that acute iAs exposure generates ROS, initiating an oxidative stress response, leaving cells vulnerable to subsequent challenges.

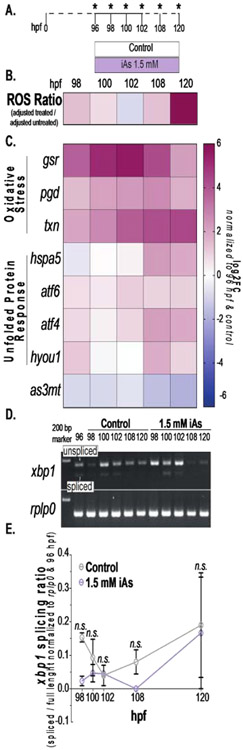

iAs induces an oxidative stress response the liver prior activation of UPR target genes

Excessive ROS can disrupt the redox balance in the ER and impair oxidative protein folding, leading to ER stress and UPR activation. In other settings, ROS has been shown to reduce UPR activation by redirecting Ire1α function from the UPR to enhance the oxidative stress response via p38/MAP kinase activation (Hourihan et al., 2016). If oxidative stress leads to UPR activation in response to iAs, then ROS production and induction of the oxidative stress response genes should precede the activation of key UPR genes. To test this, we quantified ROS and used qPCR to analyze the expression of genes that are highly responsive to ER and oxidative stress in the liver of control larvae and their siblings exposed to 1.5 mM iAs from 96-120 hpf collected at 98, 100, 102, 108 and 120 hpf, representing 2, 4, 6, 12 and 24 hours of exposure; samples were also collected from a pool of control larvae at 96 hours to enable comparison over time (Figure 7A). ROS values were adjusted to blank solutions (embryo medium with or without 1.5 mM iAs) and the log2FC of the ratio of the adjusted treated over the adjusted control was calculated (Figure 7B and S3A). Gene expression in treated larvae was normalized to untreated larvae from the same clutch, and to show change over time, the expression values for each gene at each time point were divided by the expression detected at 96 hours (i.e. t=0). The heatmap of log2FC of ROS levels shows that after 2 hours of 1.5 mM iAs exposure, ROS levels are elevated and are maximal at 120 hpf (Fig. 7B). This is accompanied by a bimodal expression pattern of the oxidative stress response genes gsr, pgd and txn (Figure 7C), which follows a parallel pattern of ROS levels, which return to baseline by 6 hours of treatment (at 102 hpf) but begin to increase again by 12 hours of exposure and reach their maximum at 24 hours of exposure (at 120 hpf; Figure 4B and S3A). The oxidative stress response genes follow the same pattern (Figures 7C and S3B). This suggests an initial oxidative stress response that serves to mitigate ROS generation by iAs exposure, but as the exposure persists, ROS generation overwhelms the endogenous antioxidant capacity. Importantly, while some UPR genes show a similar bimodal pattern of expression, hspa5, atf4, and hyoul are most significantly upregulated only after the oxidative stress response (Figure 7B-C and S3B). In contrast, as3mt expression showed a consistent down regulation throughout exposure (Figure 7C).

Figure 7. iAs treatment induces oxidative stress prior to the unfolded protein response in larval livers.

A. Schematic of iAs time course treatment strategy. Pools of 5 livers from control and 1.5 mM iAs treated larvae were collected at indicated timepoints. B. Heatmap of ROS ratio scores (adjusted to blank) between 1.5 mM iAs treated and controls (data generated from 2 clutches, 20 fish per condition). C. Heat-map of key oxidative stress response genes (gsr, pgd, and txn) and UPR (hspa5, aft6, atf4, and hyou1) and iAs metabolism (as3mt) gene expression over time from qPCR. Log2FC was calculated using the log2(ΔΔCT) normalized to 96 hpf and untreated control siblings (data generated from 4 clutches). D. Gel elec-trophoresis images of xbp1 splicing (top) and rplp0 (bottom) on control and 1.5 mM iAs treated zebrafish liver cDNA from time course (A). E. Quantification of spliced xbp1 ratio to unspliced xbp1 normalized to rplp0 and 96 hpf. Error bars represent standard error mean (SEM). n.s. indicates not significance, 2- way ANOVA.

Finally, to assess activation of the upstream UPR sensor, Ire1α, we monitored splicing of xbp1, a key downstream target of this pathway and primary UPR transcription factor. Using primers that amplify both the unspliced and spliced transcripts, we found xbp1 splicing to be dynamic over the developmental time frame analyzed in control livers, likely reflecting the highly secretory nature of hepatocytes. There were no significant differences in spliced xbp1 to full length between control in any of these samples (Figure 7D-E). This suggests that the transcriptional response to ER stress may be mediated by Atf6, which is another central mediator of the UPR transcriptional response and is upregulated in the liver of iAs treated larvae (Fig. 7C and (Bambino et al., 2018)). Taken together, these data support the conclusion that oxidative stress response precedes UPR activation, suggesting a potentially causative relationship between these responses.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we expanded the use of zebrafish larvae as a model to study iAs toxicity. We found that embryos and larvae are most susceptible to iAs exposure at late developmental stages, coinciding with formation of the liver. We report that, as expected, iAs induces ROS formation and an oxidative stress response in the liver. This is followed by impairment of protein folding in hepatocytes and UPR activation, signifying ER stress. We propose oxidative stress as a mechanism of ER stress in the liver of animals exposed to iAs.

The use of diverse model organisms in environmental toxicology provides advantages for experimental approaches and also uncovers conserved aspects of toxicant responses (Hahn and Sadler, 2020). Zebrafish have long been an important model system in toxicological studies as administering water soluble compounds is as simple as addition to the culture medium. While we acknowledge that the doses used here exceed the concentrations humans are naturally exposed to, our analysis provides molecular insights into iAs induced responses. We were surprised to find that the different rearing media routinely used for zebrafish embryos altered the susceptibility to iAs, as we have not found similar effects in response to other chemicals (not shown). Despite the difference in the LC50 conferred by rearing in embryo medium, the toxicological response appears to cause the same phenotype, indicating that the effect was not on mechanism of action but could instead be attributed to an effect on chelation or bioavailability of iAs. Determining the chemical basis of this difference is important for the many researchers using zebrafish to study environmental toxicology.

The contribution of oxidative stress to iAs toxicity is conserved across species (Santra et al., 2000a; Santra et al., 2000b; Liao and Yu, 2005; Ghatak et al., 2011; Fuse et al., 2016). However, the prevailing focus on oxidative stress has diverted attention from the contribution of other cellular stress response pathways in iAs toxicity. Despite the significant impact of arsenic on liver disease (Santra et al., 2000b; Lu et al., 2001; Chen and Ahsan, 2004; Arteel et al., 2008; Liaw et al., 2008; Liu and Waalkes, 2008; Ghatak et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2011; Canet et al., 2012; Massey et al., 2015; Li et al., 2016) the interplay between iAs induced oxidative stress and the UPR in hepatocytes is not well understood. We (Bambino et al., 2018) and others (Naranmandura et al., 2012; Weng et al., 2014; Srivastava et al., 2016b; Xu et al., 2017b) discovered that iAs exposure activates the UPR in a variety of cell types, including hepatocytes, suggesting that iAs causes ER stress. However, there is little known about the mechanism by which UPR activation is triggered by iAs. This is important, as the UPR is a central mechanism underlying many hepatic pathologies (Henkel and Green, 2013; Rutkowski, 2018; Maiers and Malhi, 2019).

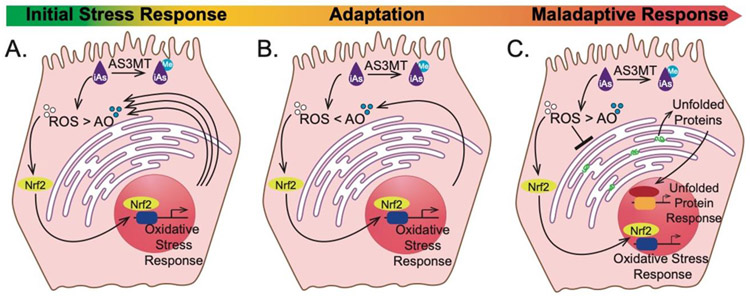

The current work shows that acute iAs exposure induces ROS, leading to a transcriptional induction of genes involved in the oxidative stress response, followed by induction of key UPR genes and reducing protein secretion from hepatocytes. Our finding that 12 hours of iAs exposure sensitizes larvae to a subtoxic challenge with a pro-oxidant demonstrates that oxidative stress is a mechanism of iAs toxicity in this model. These data are consistent with a model (Figure 8A-C) whereby ROS elevation caused either by iAs metabolism or through the direct depletion of endogenous antioxidant factors occurs in the initial 6-12 hours of exposure. This leads to the activation of Nrf2 target genes that function in the oxidative stress response, which serves to mitigate ROS accumulation and adapts cells to exposure (Figure 8B). However, as the exposure persists, ROS levels overwhelm the oxidative stress response capacity, disrupts the redox balance in the ER, leading to the transcriptional upregulation of key UPR genes and to impaired secretory protein processing, indicative of a maladaptive response (Figure 8C).

Figure 8. iAs induced redox imbalance triggers oxidative stress followed by UPR.

Working model of the hepatocyte response to iAs challenge: iAs (purple) shifts the redox balance by accumulation of ROS (white) due to metabolism (As3mt) and direct depletion of antioxidants (AO; blue) through thiol binding. To alleviate the imbalance, the oxidative response is initiated through Nrf2 to increase the antioxidant capacity of the hepatocytes (A). This is followed by an influx of antioxidants that allows for adaptation to the initial oxidative stress response where the hepatocytes are able to combat iAs-induced ROS production (B). Prolonged exposure shifts the response from adaptation to maladaptation, as the hepatocytes continue accumulating more ROS. This leads to accumulation of unfolded proteins (green) in the ER, which triggers the UPR in parallel to the oxidative response (C).

The liver is an essential site of xenobiotic metabolism and detoxification, making it particularly vulnerable to iAs toxicity. Indeed, the primary site of iAs metabolism via As3mt occurs in the liver, and thus people exposed to iAs are at increased risk for liver disease and cancer (Smith et al., 1992; Santra et al., 1999; Chen and Ahsan, 2004; Mazumder, 2005; Liaw et al., 2008; Liu and Waalkes, 2008; Hao et al., 2013; Naujokas et al., 2013; Frediani et al., 2018; Young et al., 2018). We report that susceptibility to both acute and chronic iAs toxicity in zebrafish larvae is correlated with the formation of the liver, suggesting that the liver is the main contributor to the systemic iAs toxicity. iAs toxicity is correlated to developmental stages, with larval stages after the development of a mature digestive tract as highly susceptible. We speculate that this is relevant to the formation of the liver but are cognizant that other developmental milestones – such as swallowing – also coincide with this time frame. Indeed, we find that that other cell types sensitive to redox imbalance are affected by iAs: the accumulation of melanocyte clusters, reminiscent of skin darkening observed in arsenic exposed populations (Wei et al., 2018) could be caused by oxidative stress, as melanin is produced through a series of oxidation reactions. A shift in the redox balance in melanocytes causes constitutive melanin production. Therefore, in both the liver and skin of zebrafish, oxidative stress caused by iAs exposure impacts cellular function.

The role of As3mt in the liver and its contribution to overall systematic toxicity remains to be examined. Our previous work supports the hypothesis that As3mt activity in the liver is correlated with iAs toxicity susceptibility as as3mt is enriched in the liver compared to the carcass (Bambino et al., 2018). Here, although we see iAs toxicity correlated with liver bud development, our time course analysis shows that as3mt expression is reduced over time throughout acute iAs challenge (Figure 7C). One possibility is that while the as3mt RNA is decreased, the As3mt protein levels may be unaffected during iAs challenge. Alternatively, there could also be a negative feedback loop as As3mt activity produces byproducts that are more detrimental to the cells than iAs at this concentration of iAs exposure. Arsenic metabolism by As3mt from trivalent forms to methylated forms could produce free radicals, including peroxide, and utilize GSH to promote oxidative damage (Flora, 2011). It is also possible that this methylation reaction could deplete the S-adenyl methionine, which is essential for DNA and protein methylation and cell survival. Our preliminary studies found that chronic iAs treatment had no impact on DNA methylation in zebrafish (not shown), however, whether methylation of proteins or locus specific DNA methylation changes are impacted by iAs remains to be examined. Further studies into the timing of liver growth and as3mt expression and activity will help elucidate the contribution of iAs, corresponding arsenic metabolites and systematic toxicity during iAs challenge.

Many studies have concluded that arsenic causes toxicity through ROS production and redox imbalance in diverse cell types (Ahamed et al., 2019; Kaushal et al., 2019; Lv et al., 2019). iAs metabolism through a series of methylation reactions mediated by As3mt produces free radicals, including peroxide. This reaction also utilizes GSH, which contributes to elevated ROS levels (Flora, 2011). How could oxidative stress lead to ER stress in this model? One possibility is that excessive ROS prevents the redox cycle between protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) and ERO1α (Sapra et al., 2015), fixing PDI in an oxidized state so that it cannot serve as an electron recipient during sulfhydryl bond formation on nascent proteins in the ER (Sevier and Kaiser, 2006) and fixing ERO1 in an oxidized and inactive state (Sevier and Kaiser, 2008). In this scenario, iAs exposure could cause ER stress and UPR activation through an indirect mechanism due to shifting the redox balance in the ER to a hyperoxidized state. A second mechanism is that free arsenal species can indirectly modulate cellular ROS levels through promiscuous interactions with thiol groups and antioxidants, including GSH (Park et al., 2018). The thiol-binding properties of iAs can directly impair the oxidative folding of nascent proteins in the ER by preventing PDI-mediated disulfide bond formation, leading to unfolded protein accumulation. In this scenario, iAs exposure would cause ER stress due to direct effects on protein folding. Another possibility is suggested by the exciting finding that iAs and other pro-oxidants modify a key UPR mediator, Ire1α, interfering with UPR signaling and, in parallel, activating the Nrf2 mediated antioxidant response pathway via p38 signaling (Hourihan et al., 2016). This suggests extensive crosstalk between these two pathways in iAs exposed cells. However, the impact of this crosstalk on disease-relevant outcomes of iAs exposure have not been explored.

Deciphering whether iAs induces ER stress due to a direct effect caused by thiol-binding or to indirect mechanisms due to disrupting of the redox balance in the ER, or a combination of these two pathways, remains to be investigated. Our finding that iAs induces both oxidative stress and ER stress suggests that both stress responses underlie hepatotoxicity, which is a significant cause of iAs mediated disease. Given the prominent role of the UPR in liver disease, including fatty liver (Henkel and Green, 2013; Rutkowski, 2018; Maiers and Malhi, 2019), it will be important for future work to decipher how this pathway contributes to liver disease caused by iAs.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Arsenic induced mortality in zebrafish larvae is correlated with liver development.

Acute arsenic exposure induces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antioxidant response in the liver of zebrafish larvae.

Arsenic induced ROS accumulation and an oxidative stress response precedes activation of the unfolded protein response in the liver.

Endoplasmic reticulum stress is a late cellular response in the liver of zebrafish larvae exposed to arsenic.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to K. Bambino for preliminary data, to S. Ranjan for expert animal care, J. Thattamparambil for the scientific illustration, to members of the Sadler lab for input and technical support and to M. Hahn for insightful comments and fruitful discussion. Additionally, the authors are indebted to the NYUAD Core Technology Platform Imaging Facility, especially R. Rezgui, M. Sultana, M. Arnoux, and N. Drou, for continued technical support and careful maintenance of the facilities.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the NYUAD Faculty Research Fund and the NIH (to KCS 5R01AA018886).

Abbreviations:

- iAs

Inorganic Arsenic

- ER

Endoplasmic Reticulum

- UPR

Unfolded Protein Response

- ROS

Reactive Oxygen species

- hpf

hours post fertilization

- dpf

days post fertilization

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione disulfide

- Ire1α

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1 α

- PERK

Protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase

- Atf6

Activating transcription factor 6

- Nrf2

Nuclear factor erythroid-2-related factor 2

- PDI

Protein disulfide-isomerase

- Ero1

Endoplasmic reticulum oxidation 1

- As3mt

Arsenite methyltransferase

- Gc

Group-complement

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- nls

nuclear localizing signal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Database: RNA-Seq dataset (GEO access number GSE104953)

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Adeyemi JA, da Cunha Martins-Junior A, Barbosa F Jr., 2015. Teratogenicity, genotoxicity and oxidative stress in zebrafish embryos (Danio rerio) co-exposed to arsenic and atrazine. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol 172-173, 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahamed M, Akhtar MJ, Khan MAM, Alrokayan SA, Alhadlaq HA, 2019. Oxidative stress mediated cytotoxicity and apoptosis response of bismuth oxide (Bi2O3) nanoparticles in human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells. Chemosphere 216, 823–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arteel GE, Guo L, Schlierf T, Beier JI, Kaiser JP, Chen TS, Liu M, Conklin DJ, Miller HL, von Montfort C, States JC, 2008. Subhepatotoxic exposure to arsenic enhances lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 226, 128–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bali İ, Bilir B, Emir S, Turan F, Yılmaz A, Gökkuş T, Aydin M, 2016. The effects of melatonin on liver functions in arsenic-induced liver damage. Ulus Cerrahi Derg 32, 233–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bambino K, Zhang C, Austin C, Amarasiriwardena C, Arora M, Chu J, Sadler KC, 2018. Inorganic arsenic causes fatty liver and interacts with ethanol to cause alcoholic liver disease in zebrafish. Disease Models & Mechanisms 11, dmm031575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaver LM, Truong L, Barton CL, Chase TT, Gonnerman GD, Wong CP, Tanguay RL, Ho E, 2017. Combinatorial effects of zinc deficiency and arsenic exposure on zebrafish (Danio rerio) development. PLoS One 12, e0183831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benham AM, 2019. Endoplasmic Reticulum redox pathways: in sickness and in health. FEBS J 286, 311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benyettou F, Prakasam T, Nair AR, Witzel II, Alhashimi M, Skorjanc T, Olsen JC, Sadler KC, Trabolsi A, 2019. Potent and selective in vitro and in vivo antiproliferative effects of metal-organic trefoil knots. Chemical Science 10, 5884–5892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canet MJ, Hardwick RN, Lake AD, Kopplin MJ, Scheffer GL, Klimecki WT, Gandolfi AJ, Cherrington NJ, 2012. Altered arsenic disposition in experimental nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug Metab Dispos 40, 1817–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Ahsan H, 2004. Cancer burden from arsenic in drinking water in Bangladesh. Am J Public Health 94, 741–744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu J, Sadler KC, 2009. New school in liver development: lessons from zebrafish. Hepatology 50,1656–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahan D, Jude BA, Lamendella R, Keesing F, Perron GG, 2018. Exposure to Arsenic Alters the Microbiome of Larval Zebrafish. Front Microbiol 9, 1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diedrichs DR, Gomez JA, Huang CS, Rutkowski DT, Curtu R, 2018. A data-entrained computational model for testing the regulatory logic of the vertebrate unfolded protein response. Mol Biol Cell 29, 1502–1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson M, de la Vega MR, Harder B, Castro-Portuguez R, Rodrigues SD, Wong PK, Chapman E, Zhang DD, 2018. Low-level arsenic causes proteotoxic stress and not oxidative stress. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 341, 106–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobná Z, Walton FS, Paul DS, Xing W, Thomas DJ, Stýblo M, 2010. Metabolism of arsenic in human liver: the role of membrane transporters. Archives of Toxicology 84, 3–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erguler K, Pieri M, Deltas C, 2013. A mathematical model of the unfolded protein stress response reveals the decision mechanism for recovery, adaptation and apoptosis. BMC Syst Biol 7,16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora SJ, 2011. Arsenic-induced oxidative stress and its reversibility. Free Radic Biol Med 51, 257–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora SJ, Bhadauria S, Kannan GM, Singh N, 2007. Arsenic induced oxidative stress and the role of antioxidant supplementation during chelation: a review. J Environ Biol 28, 333–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frediani JK, Naioti EA, Vos MB, Figueroa J, Marsit CJ, Welsh JA, 2018. Arsenic exposure and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) among U.S. adolescents and adults: an association modified by race/ethnicity, NHANES 2005-2014. Environ Health 17, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuse Y, Nguyen VT, Kobayashi M, 2016. Nrf2-dependent protection against acute sodium arsenite toxicity in zebrafish. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 305, 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatak S, Biswas A, Dhali GK, Chowdhury A, Boyer JL, Santra A, 2011. Oxidative stress and hepatic stellate cell activation are key events in arsenic induced liver fibrosis in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 251, 59–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra-Moreno A, Ang J, Welsch H, Jochem M, Hanna J, 2019. Regulation of the unfolded protein response in yeast by oxidative stress. FEBS Lett 593, 1080–1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guha Mazumder DN, De BK, Santra A, Ghosh N, Das S, Lahiri S, Das T, 2001. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonate (DMPS) in therapy of chronic arsenicosis due to drinking arsenic-contaminated water. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 39, 665–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME, McArthur AG, Karchner SI, Franks DG, Jenny MJ, Timme-Laragy AR, Stegeman JJ, Woodin BR, Cipriano MJ, Linney E, 2014. The transcriptional response to oxidative stress during vertebrate development: effects of tert-butylhydroquinone and 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. PLoS One 9, e113158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn ME, Sadler KC, 2020. Casting a wide net: use of diverse model organisms to advance toxicology. Dis Model Mech 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi M, Yoshinaga M, Packianathan C, Qin J, Hallauer J, McDermott JR, Yang HC, Tsai KJ, Liu Z, 2012. Identification of an S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) dependent arsenic methyltransferase in Danio rerio. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 262, 185–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao L, Zhao J, Wang X, Wang H, Wang H, Xu G, 2013. Hepatotoxicity from arsenic trioxide for pediatric acute promyelocytic leukemia. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 35, e67–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel A, Green RM, 2013. The unfolded protein response in fatty liver disease. Semin Liver Dis 33, 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoonjan M, Jadhav V, Bhatt P, 2018. Arsenic trioxide: insights into its evolution to an anticancer agent. J Biol Inorg Chem 23, 313–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourihan JM, Moronetti Mazzeo LE, Fernandez-Cardenas LP, Blackwell TK, 2016. Cysteine Sulfenylation Directs IRE-1 to Activate the SKN-1/Nrf2 Antioxidant Response. Mol Cell 63, 553–566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth DL, Lindtner C, Vacaru AM, Sachidanandam R, Tsedensodnom O, Vasilkova T, Buettner C, Sadler KC, 2014. Activating transcription factor 6 is necessary and sufficient for alcoholic fatty liver disease in zebrafish. PLoS Genet 10, e1004335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth DL, Yin C, Yeh K, Sadler KC, 2013. Defining hepatic dysfunction parameters in two models of fatty liver disease in zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish 10, 199–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Yu C, Yao M, Wang L, Liang B, Zhang B, Huang X, Zhang A, 2018. The PKCδ-Nrf2-ARE signalling pathway may be involved in oxidative stress in arsenic-induced liver damage in rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 62, 79–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomova K, Jenisova Z, Feszterova M, Baros S, Liska J, Hudecova D, Rhodes CJ, Valko M, 2011. Arsenic: toxicity, oxidative stress and human disease. Journal of applied toxicology : JAT 31, 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaushal S, Ahsan AU, Sharma VL, Chopra M, 2019. Epigallocatechin gallate attenuates arsenic induced genotoxicity via regulation of oxidative stress in balb/C mice. Mol Biol Rep 46, 5355–5369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Sideris DP, Sevier CS, Kaiser CA, 2012. Balanced Erol activation and inactivation establishes ER redox homeostasis. J Cell Biol 196, 713–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosanovic M, Hasan MY, Subramanian D, Al Ahbabi AA, Al Kathiri OA, Aleassa EM, Adem A, 2007. Influence of urbanization of the western coast of the United Arab Emirates on trace metal content in muscle and liver of wild Red-spot emperor (Lethrinus lentjan). Food Chem Toxicol 45, 2261–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CC, Moon KA, Wang SL, Silbergeld E, Navas-Acien A, 2017. The Association of Arsenic Metabolism with Cancer, Cardiovascular Disease, and Diabetes: A Systematic Review of the Epidemiological Evidence. Environ Health Perspect 125, 087001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Li P, Tan YM, Lam SH, Chan EC, Gong Z, 2016. Metabolomic Characterizations of Liver Injury Caused by Acute Arsenic Toxicity in Zebrafish. PLoS One 11, e0151225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li D, Lu C, Wang J, Hu W, Cao Z, Sun D, Xia H, Ma X, 2009. Developmental mechanisms of arsenite toxicity in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Aquatic toxicology 91, 229–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao VH, Yu CW, 2005. Caenorhabditis elegans gcs-1 confers resistance to arsenic-induced oxidative stress. Biometals 18, 519–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaw J, Marshall G, Yuan Y, Ferreccio C, Steinmaus C, Smith AH, 2008. Increased childhood liver cancer mortality and arsenic in drinking water in northern Chile. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17, 1982–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Waalkes MP, 2008. Liver is a target of arsenic carcinogenesis. Toxicol Sci 105, 24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Liu J, LeCluyse EL, Zhou YS, Cheng ML, Waalkes MP, 2001. Application of cDNA microarray to the study of arsenic-induced liver diseases in the population of Guizhou, China. Toxicol Sci 59, 185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv X, Li Y, Xiao Q, Li D, 2019. Daphnetin activates the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response to prevent arsenic-induced oxidative insult in human lung epithelial cells. Chem Biol Interact 302, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhang C, Gao XB, Luo HY, Chen Y, Li HH, Ma X, Lu CL, 2015. Folic acid protects against arsenic-mediated embryo toxicity by up-regulating the expression of Dvr1. Sci Rep 5, 16093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiers JL, Malhi H, 2019. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Metabolic Liver Diseases and Hepatic Fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis 39, 235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majhi CR, Khan S, Leo MD, Prawez S, Kumar A, Sankar P, Telang AG, Sarkar SN, 2014. Acetaminophen increases the risk of arsenic-mediated development of hepatic damage in rats by enhancing redox-signaling mechanism. Environ Toxicol 29, 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marbach D, Lamparter D, Quon G, Kellis M, Kutalik Z, Bergmann S, 2016. Tissue-specific regulatory circuits reveal variable modular perturbations across complex diseases. Nat Methods 13, 366–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey VL, Stocke KS, Schmidt RH, Tan M, Ajami N, Neal RE, Petrosino JF, Barve S, Arteel GE, 2015. Oligofructose protects against arsenic-induced liver injury in a model of environment/obesity interaction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 284, 304–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews V, Desire S, George B, Lakshmi KM, Rao JG, Viswabandya A, Bajel A, Srivastava VM, Srivastava A, Chandy M, 2006. Hepatotoxicity profile of single agent arsenic trioxide in the treatment of newly diagnosed acute promyelocytic leukemia, its impact on clinical outcome and the effect of genetic polymorphisms on the incidence of hepatotoxicity. Leukemia 20, 881–883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazumder DN, 2005. Effect of chronic intake of arsenic-contaminated water on liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 206, 169–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan-Myhre K, Charette JR, Phennicie RT, Stephens WZ, Rawls JF, Guillemin K, Kim CH, 2011. Study of host-microbe interactions in zebrafish. Methods Cell Biol 105, 87–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M, Chatterjee S, Flora SJS, 2018. Combination therapy with vitamin C and DMSA for arsenic-fluoride co-exposure in rats. Metallomics 10, 1291–1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizusawa K, Kasagi S, Takahashi A, 2018. Melanin-concentrating hormone is a major substance mediating light wavelength-dependent skin color change in larval zebrafish. General and Comparative Endocrinology 269, 141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nain S, Smits JE, 2012. Pathological, immunological and biochemical markers of subchronic arsenic toxicity in rats. Environ Toxicol 27, 244–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranmandura H, Xu S, Koike S, Pan LQ, Chen B, Wang YW, Rehman K, Wu B, Chen Z, Suzuki N, 2012. The endoplasmic reticulum is a target organelle for trivalent dimethylarsinic acid (DMAIII)-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 260, 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naujokas MF, Anderson B, Ahsan H, Aposhian HV, Graziano JH, Thompson C, Suk WA, 2013. The broad scope of health effects from chronic arsenic exposure: update on a worldwide public health problem. Environ Health Perspect 121, 295–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park WH, Han BR, Park HK, Kim SZ, 2018. Arsenic trioxide induces growth inhibition and death in human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells accompanied by mitochondrial O2*- increase and GSH depletion. Environ Toxicol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, 2018. Liver function and dysfunction - a unique window into the physiological reach of ER stress and the unfolded protein response. FEBS J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra A, Das Gupta J, De BK, Roy B, Guha Mazumder DN, 1999. Hepatic manifestations in chronic arsenic toxicity. Indian J Gastroenterol 18, 152–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra A, Maiti A, Chowdhury A, Mazumder DN, 2000a. Oxidative stress in liver of mice exposed to arsenic-contaminated water. Indian J Gastroenterol 19, 112–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santra A, Maiti A, Das S, Lahiri S, Charkaborty SK, Mazumder DN, 2000b. Hepatic damage caused by chronic arsenic toxicity in experimental animals. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol 38, 395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapra A, Ramadan D, Thorpe C, 2015. Multivalency in the inhibition of oxidative protein folding by arsenic(III) species. Biochemistry 54, 612–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Mukherjee S, Chattopadhyay A, Bhattacharya S, 2014. Low dose of arsenic trioxide triggers oxidative stress in zebrafish brain: expression of antioxidant genes. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 107, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier CS, Kaiser CA, 2006. Disulfide transfer between two conserved cysteine pairs imparts selectivity to protein oxidation by Ero1. Mol Biol Cell 17, 2256–2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevier CS, Kaiser CA, 2008. Ero1 and redox homeostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783, 549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley PL, Kinniburgh DG, 2002. A review of the source, behaviour and distribution of arsenic in natural waters. Applied Geochemistry 17, 517–568. [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Hopenhayn-Rich C, Bates MN, Goeden HM, Hertz-Picciotto I, Duggan HM, Wood R, Kosnett MJ, Smith MT, 1992. Cancer risks from arsenic in drinking water. Environ Health Perspect 97, 259–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AH, Lingas EO, Rahman M, 2000. Contamination of drinking-water by arsenic in Bangladesh: a public health emergency. Bull World Health Organ 78, 1093–1103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava R, Sengupta A, Mukherjee S, Chatterjee S, Sudarshan M, Chakraborty A, Bhattacharya S, Chattopadhyay A, 2013. In Vivo Effect of Arsenic Trioxide on Keap1-p62-Nrf2 Signaling Pathway in Mouse Liver: Expression of Antioxidant Responsive Element-Driven Genes Related to Glutathione Metabolism. ISRN Hepatol 2013, 817693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava RK, Li C, Ahmad A, Abrams O, Gorbatyuk MS, Harrod KS, Wek RC, Afaq F, Athar M, 2016a. ATF4 regulates arsenic trioxide-mediated NADPH oxidase, ER-mitochondrial crosstalk and apoptosis. Arch Biochem Biophys 609, 39–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava RK, Li C, Wang Y, Weng Z, Elmets CA, Harrod KS, Deshane JS, Athar M, 2016b. Activating transcription factor 4 underlies the pathogenesis of arsenic trioxide-mediated impairment of macrophage innate immune functions. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 308, 46–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun HJ, Zhang JY, Wang Q, Zhu E, Chen W, Lin H, Chen J, Hong H, 2019. Environmentally relevant concentrations of arsenite induces developmental toxicity and oxidative responses in the early life stage of zebrafish. Environ Pollut 254, 113022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan M, Schmidt RH, Beier JI, Watson WH, Zhong H, States JC, Arteel GE, 2011. Chronic subhepatotoxic exposure to arsenic enhances hepatic injury caused by high fat diet in mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 257, 356–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu BP, Weissman JS, 2004. Oxidative protein folding in eukaryotes: mechanisms and consequences. J Cell Biol 164, 341–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twaddle NC, Vanlandingham M, Beland FA, Doerge DR, 2019. Metabolism and disposition of arsenic species from controlled dosing with dimethylarsinic acid (DMAV) in adult female CD-1 mice. V. Toxicokinetic studies following oral and intravenous administration. Food and Chemical Toxicology 130, 22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]