Abstract

Visceral pain from the distal colon and rectum (colorectum) is a major complaint of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mechanotransduction of colorectal distension/stretch appears to play a critical role in visceral nociception, and further understanding requires improved knowledge of the micromechanical environments at different sub-layers of the colorectum. In this study, we conducted nonlinear imaging via second harmonic generation to quantify the thickness of each distinct through-thickness layer of the colorectum, as well as the principal orientations, corresponding dispersions in orientations, and the distributions of diameters of collagen fibers within each of these layers. From C57BL/6 mice of both sexes (8–16 weeks of age, 25–35g), we dissected the distal 30 mm of the large bowel including the colorectum, divided these into three even segments, and harvested specimens (~8×8 mm2) from each segment. We stretched the specimens either by colorectal distension to 20 mmHg (reference) or 80 mmHg (deformed) or by biaxial stretch to 10 mN (reference) or 80 mN (deformed), and fixed them with 4% paraformaldehyde. We then conducted SHG imaging through the wall thickness and analyzed post-hoc using custom-built software to quantify the orientations of collagen fibers in all distinct layers. We also quantified the thickness of each layer of the colorectum, and the corresponding distributions of collagen density and diameters of fibers. We found collagen concentrated in the submucosal layer. The average diameter of collagen fibers was greatest in the submucosal layer, followed by the serosal and muscular layers. Collagen fibers aligned with muscle fibers in the two muscular layers, whereas their orientation varied greatly with location in the serosal layer. In colonic segments, thick collagen fibers in the submucosa presented two major orientations aligned approximately ±30 degrees to the axial direction, and form a patterned network. Our results indicate the submucosa is likely the principal passive load-bearing structure of the colorectum. In addition, afferent endings in those collagen-rich regions present likely candidates of colorectal nociceptors to encode noxious distension/stretch.

Keywords: Colorectum, Submucosa, Biaxial extension test, Confocal microscopy, Mechanotransduction, Visceral pain

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Visceral pain arising from the internal organs has unique clinical, psychophysical manifestations associated with organ biomechanics. It is mechanical distention/stretch of hollow visceral organs – not tissue-injurious pinching or cutting – that reliably evokes the perception of pain from the viscera; see (Feng and Guo, 2020) for a recent review. Non-mechanical stimuli to the colorectum (e.g. burning) often fail to evoke painful sensations (Feng and Guo, 2020). Hence, mechanotransduction of colorectal distension/stretch appears to play a critical role in visceral nociception. Specifically, visceral pain arising from distal colon and rectum (colorectum) is the cardinal complaint from patients with irritable bowel syndrome, a condition that affects up to 20% of the US population (Lovell and Ford, 2012).

Consistent with the importance of mechanotransduction in visceral pain, the majority of sensory afferent nerve endings in the colorectum are mechanosensitive, as systematically characterized by us previously using single-fiber recordings and a non-biased electrical search strategy (Feng and Gebhart, 2011). Mechanosensitive afferents make up 77% of the total afferent innervations of the colorectum in the lumbosacral pathway and 67% in the thoracolumbar pathway (Feng and Gebhart, 2011). Mechanically-insensitive afferents innervate the rest of the colorectum and appear to encode hyperosmotic and chemical stimuli (Feng et al., 2016). Hence, high-threshold mechanosensitive afferents that encode noxious colorectal distension are the likely candidates causing visceral pain.

To complement the wealth of literature on colorectal afferent neural encoding, we recently conducted macroscale biomechanical studies on mouse colorectal tissues via biaxial mechanical stretch and opening angle tests (Siri et al., 2019a; Siri et al., 2019b). Specifically, we uncovered differential biomechanical properties in colonic and rectal regions of the colorectum which correlate with the different dominant innervations by sensory afferents in the pelvic nerves (lumbosacral pathway) and lumbar splanchnic nerves (thoracolumbar pathway), respectively (Siri et al., 2019a). By conducting biaxial extension tests on separated sub-layers of the colorectal wall, we established direct biomechanical evidence supporting the role of submucosa as the load-bearing structure of distal colorectum (Siri et al., 2019b). Interestingly, sensory afferent endings concentrate in the submucosa and muscularis propria the colon and rectum (Spencer et al., 2014), which are focal regions of high mechanical stresses during physiological intestinal distension and peristalsis. The muscularis propria also consists of the myenteric plexus that provides major intrinsic innervation to the colon (Furness, 2012).

Further advancing our understanding of mechanotransduction requires microscale knowledge of the biomechanical environment within each sub-layer of the colorectal wall, each embedded with extrinsic sensory afferent endings except the serosal layer (Brookes et al., 2013; Spencer et al., 2014). The morphology, orientation, and content of collagen fibers largely determine the micromechanics of soft biological tissues and these fibers serve as the major load-bearing structures for many biological tissues (e.g. skin, tendon, cartilage, and blood vessels (Nimni and Harkness, 1988)). Thus determining the principal orientation and morphology of collagen fibers in the colorectum will likely provide key insights on the load-bearing regions that undergo noxious colorectal distension/stretch. Further, afferent endings in those collagen-rich regions are likely candidates for colorectal nociceptors to encode noxious distension/stretch.

Recent advances in nonlinear optical imaging established that second harmonic generation (SHG) confocal microscopy is a highly selective modality for detecting collagen fibers in biological tissues (Chu et al., 2009). The approach has since been leveraged to reveal the structure of collagen within arteries (Schriefl et al., 2012b), cartilages (Lilledahl et al., 2011), and the myocardium (Sommer et al., 2015), among several examples. Similarly, scanning or transmission electron microscopy provide information about the structure of collagen, and even interactions at a molecular level with remarkable magnification, but remain limited to imaging of exposed surfaces or sectioned tissues (Wang et al., 2020; Wenstrup et al., 2004). Conventionally the contents and morphology of collagen fibers were characterized in biological tissues by chromatic staining, e.g. polarized light microscopy (Kiraly et al., 1997; Whittaker and Canham, 1991), and fluorescent staining, e.g. antibody to collagen (Dolber and Spach, 1993; Vogel et al., 2015). To ensure proper binding of chromatic dye or antibodies to collagen fibers, staining was generally performed on thin sections of tissue less than 40 microns thick.

In contrast, SHG microscopy images collagen up to 1000 microns within soft tissues or less than < 100 microns within hard tissues ), thus facilitating images of the collagen architecture in-situ (Theer et al., 2003). A comparable depth of imaging can be achieved with line field optical coherence tomography, e.g. (Tognetti et al., 2020).

In this study, we conducted SHG imaging through the thickness of colorectal walls of mice harvested from three axially distinct locations: the colonic, intermediate, and rectal regions. To assess the effects of mechanical loading, we applied either 10 mmHg (innocuous) intraluminal distension or 60 mmHg (noxious) distension to the colorectum and analyzed SHG images from both groups. We implemented custom image analyses to systematically quantify the collagen network at different colorectal layers using the following parameters: relative contents, distribution of fiber orientation (orientation and dispersion), and diameters of fibers.

Materials and Methods

Specimen preparation

We harvested the distal 30 mm of the colorectum from twenty five mice of either sex for this study (C57BL/6, Taconic, Germantown, NY), which were 8–16 weeks in age and weighed 20–30 g. This age group includes young adult and adult mice consistent with prior studies focusing on colorectal afferent neurophysiology, e.g. (Brierley et al., 2005a; Brierley et al., 2004; Brierley et al., 2005b; Feng and Gebhart, 2011, 2015; Feng et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2013; Feng et al., 2012b; Feng et al., 2012c). We anesthetized mice by isoflurane inhalation, euthanized by exsanguination after perforating the right atrium, and transcardially perfused with oxygenated Krebs solution (in mM: 117.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 25 NaHCO3, 1.3 NaH2PO4, 1.2 MgSO4∙7H2O, 2.5 CaCl2, 11.1 D-Glucose, 2 butyrate, and 20 acetate) bubbled with carbogen (95% O2, 5% CO2). By performing a midline laparotomy and transecting the pubic symphysis, we exposed the pelvic floor organs to harvest the distal 30 mm of the large bowel, i.e. the distal colon and rectum. We carefully removed connective tissues and transferred specimens to modified Krebs solution with added nifedipine (4 μM; L-type calcium channel antagonist to block muscle activities), penicillin-streptomycin (100 U/ml, Fisher Scientific, Greenwich, RI), and protease inhibitors (P2714, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Consistent with prior electrophysiological and behavioral studies implementing colorectal distension, e.g. (Feng et al., 2012a), we cannulated and distended each colon with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) at room temperature and at ascending levels of graded intraluminal pressure: 15, 30, 45, 60 mmHg, ten sec per distension, at least four times. We divided the 30 mm colorectum segment axially into three segments of 10 mm each, i.e. the colonic, intermediate and rectal segments from proximal to distal locations.

Using 12 of the specimens of colorectum, we cut the cylindrical segments open into tissue squares of ~8 × 8 mm2 and applied biaxial extension using our custom mechanical testing setup reported previously (Siri et al., 2019a; Siri et al., 2019b). We stretched each square of tissue biaxially by either 10 mN (reference) or 80 mN (stretched) and fixed them in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) at room temperature for 60 min.

We divided the remaining 13 specimens of colorectum into two groups, either reference (seven colons) or stretched (six colons). We cannulated both groups of specimens and distended them with an intraluminal pressure of either 20 mmHg (reference) or 80 mmHg (stretched) at room temperature. We maintained the distension for 6 hours to eliminate any time-dependent mechanical effects within the tissue, consistent with the slow-ramped, biaxial stretch we used previously (Siri et al., 2019a; Siri et al., 2019b). We monitored the intraluminal pressure during distension and maintained it at 80 mmHg. We then fixed the distended colorectums in 4% PFA at room temperature for 60 min. Finally, we rinsed specimens in PBS three times (5 min each) to remove the PFA, divided them into three segments, cut each open, and mounted each onto glass slides (Permount, Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH) with the serosa side facing the cover slip (No 1.5).

Images via second harmonic generation confocal microscopy

We imaged through the wall thickness of the mounted colorectal specimens using nonlinear SHG imaging with two-photon microscopy. We imaged specimens that underwent biaxial stretching using an LSM 780 system (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, DE) equipped with a 40× objective (C-Apochromat 40×/1.2 W Corr, working distance of 280 μm). We imaged specimens distended by intraluminal pressure using a LSM 510 system (Carl Zeiss) with a 20× objective (W Plan-Apochromat 20×/1.0, working distance of 1.8 mm). We used a tunable two-photon light source (Chameleon, Coherent, Santa Clara, CA) at 900 nm (40×) and 850 nm (20×) to excite the SHG and collected the signal at 450 nm and 425 nm, respectively. Different bandpass filters available for the two microscopy systems required slight adjustments of excitation and recording wavelength. We carefully tested the wavelength we used to ensure proper detection of SHG signals. We obtained images at 1 μm steps through the thickness of the specimen.

Analyses of images

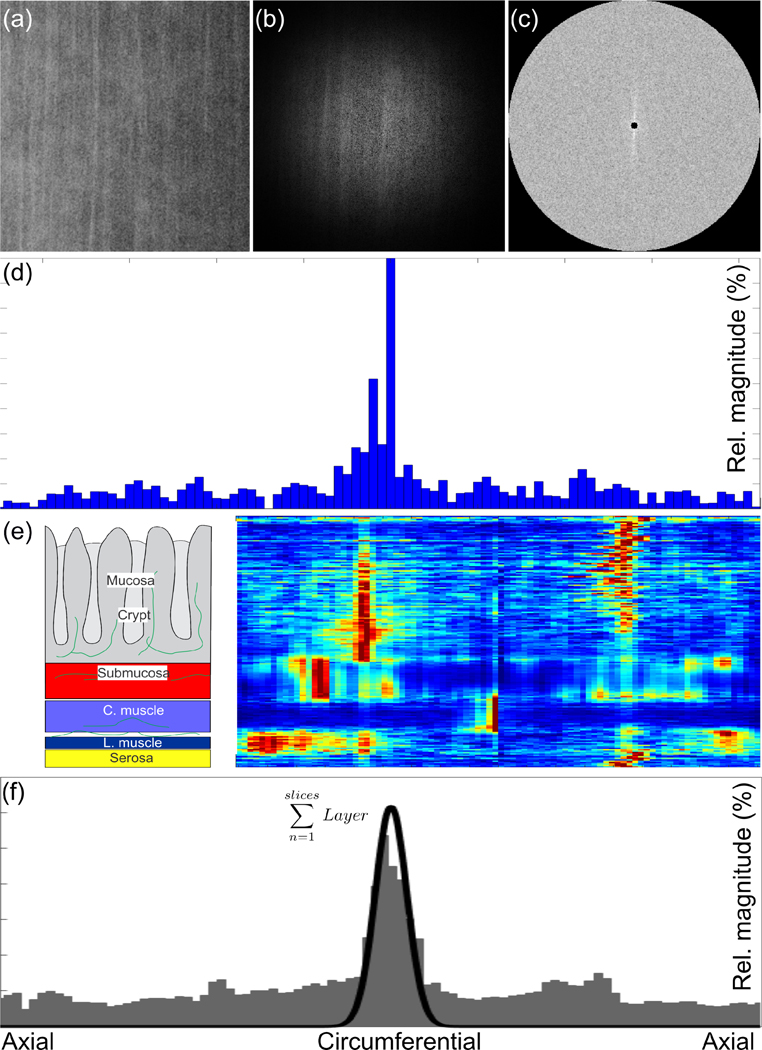

We applied a specialized analysis algorithm to determine the fiber direction from the image stacks we obtained, see Fig. 1 (Schriefl et al., 2012a; Schriefl et al., 2012b). Briefly, we first used ImageJ (1.52i, NIH, USA) to enhance the contrast of our images by histogram equalization and we manually adjusted brightness and contrast, if required. We then converted the Zeiss image stack into a sequence of bitmap images (jpgs). To account for potential rotation of the specimens on the glass slides we set the orientations of the fibers in the layer of circular muscle as a reference to 0°. Next we calculated the 2-D Fourier transformation and the power spectrum density. Via wedge filtering, we then obtained the radial intensity histogram. The peak locations in the histogram corresponded to the principal orientations of the fibers while the width of the peaks indicated the degree of alignment (conversely dispersion) of collagen fibers about the principal orientation.

Figure 1.

Overview of our analyses of the images obtained via SHG. We (a) applied a Hamming filter, (b) performed fast-Fourier transform, and (c) calculated the power spectral density. Using (c) we quantified, via wedge-filtering, the distribution of the fibers in the original image as a histogram. We repeated this process for all the images within a z-stack and (e) generated a 2-D representation of all of the histograms where red in the color scale corresponds to a maximum in the relative magnitude. We then (f) summed these histograms from each layer to obtain an overall histogram representing the fiber distribution within that layer, facilitating our fitting with a Von Mises distribution quantifying the principal orientation and dispersion in orientation (black line).

Two independent, trained observers (FRM, SAS) examined the image stacks to manually quantify the thicknesses of the individual layers through the thickness of each specimen. We leveraged this information about the thickness of each layer to generate averaged histograms (layer-specific histograms) representative of the collagen orientations within each corresponding layer. We used these layer-specific histograms to fit von Mises distributions to the orientation data of each functional layer within each specimen and thus obtain fitting parameters representing the collagen morphology (Lilledahl et al., 2011), i.e. the location parameter μ and the concentration parameter b, where b = 0 indicates isotropy and b → ∞ indicates perfect alignment, cf. (Gasser et al., 2006; Schriefl et al., 2012b). We also best fit lines to the corresponding cumulative distribution functions to determine the degrees of tissue anisotropy (Schriefl et al., 2012a; Schriefl et al., 2012b). Additionally, we combined the layer-specific histograms from all specimens to generate composite histograms for each location and treatment, and repeated the same fitting process. We used these combined analyses to quantify the overall, composite morphology of all the specimens we investigated. We completed all image analyses using a custom algorithm implemented in MATLAB (R2019b, MathWorks, Natick, USA).

Statistical analyses

We used three-way ANOVAs to identify statistically significant differences among both the thicknesses of layers and diameters of fibers based on configuration (reference vs. deformed) and tissue layers (serosa, muscle, submucosa, mucosa). We performed post-hoc power analyses for configuration (reference, deformed), segment (colonic, intermediate, rectal), layer (serosa, circular muscle, submucosa), configuration vs. segment, configuration vs. segment, and configuration vs. segment. We also used Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons for cases with significant F values for main effects.

Prior to data collection, we determined the sample sizes for our experiments by power analyses relying on standard deviations estimated from our prior biomechanical studies on the colorectums of mice (Siri et al., 2019a; Siri et al., 2019b). Additionally, we validated the statistical power of each factor (configuration, segment, layer, configuration × segment, segment × layer, and configuration × layer) after data collection as >0.8.

We completed all statistical analysis using SigmaPlot v14.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) with a significance level P < 0.05.

Results

Images via second harmonic generation confocal microscopy

SHG imaging of the mouse intestine tissue captured the characteristic layers, i.e. serosa, circumferential and axial muscle, submucosa, and mucosa, for all specimens, see Fig. 2. The through-thickness-intensity profile revealed that the SHG signal, which is proportional to the collagen content, was strongest in the submucosa. We needed to use contrast enhancement to reveal the morphology of fibers in the other layers.

Figure 2.

(a) A representative through-thickness image and corresponding intensity plot reveals the strongest signal originated from the submucosa. (b) We confirmed the finding by reviewing representative images before contrast enhancements. Only the submucosa (1) presents visible fibers, while the remaining specimens (2-5) appear black. (c) With enhanced contrast, we see clear fibers in the serosa (2) and blurry, but distinct, fibers in the circumferential (3) and axial (4) muscle layers and the mucosa (5). (d) With an intraluminal pressure of 20 mmHg (left) the reference specimen has wavy fibers while a pressure of 80 mmHg (right) causes the collagen fibers to stretch.

The stretching treatment resulted in fiber recruitment, i.e. stretching of the fibers. However, our equi-biaxial extension did not provide consistent recruitment and we could only observe this behavior reliably when inflating the specimen. Additionally, we could only observe stretched fibers in the colonic segments, while fibers in the intermediate and rectal segments remained wavy.

Analyses of images and statistical analyses

Thicknesses of layers

The mucosa layer was thickest in all segments (colonic, intermediate, rectal), followed in descending order by submucosa, muscle layer, and serosa, see Fig. 3. The layer thicknesses for reference vs. deformed (stretched) configurations showed significant differences (three-way ANOVA, F1,123 = 9.225, P = 0.003) for all three segments. Among the four layers of the colorectum the mucosa layer thinned significantly when we inflated the complete specimen (post-hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 29.762 μm, t = 5.844, P < 0.001). The thicknesses of the remaining layers did not undergo any significant changes (post-hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 2.294 μm, t = 0.548, P = 0.584 for submucosa; Difference of Means = 2.619 μm, t = 0.626, P = 0.532 for muscle layer; and Difference of Means = 1.581 μm, t = 0.372, P = 0.711 for serosa). We provided the corresponding data on the mean thickness of each individual layer determined from all specimens in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Layer thicknesses of specimens from (a) colonic, (b) intermediate, and (c) rectal locations show a similar pattern. The mucosa is thickest, followed in descending order by submucosa, muscle, and serosa. The * indicates a significant difference between reference and deformed configurations.

Table 1.

The mean layer thicknesses for all layers (serosa, muscle, submucosa, mucosa) for all segments of colorectum (colonic, intermediate, rectal) in both the reference and deformed configurations obtained via analyses of SHG images.

| Colonic | Intermediate | Rectal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Deformed | Reference | Deformed | Reference | Deformed | |

| Serosa (μm) | 16.83 | 16.14 | 23.40 | 15.83 | 31.83 | 44.83 |

| Muscle (μm) | 20.17 | 17.86 | 23.00 | 28.67 | 39.00 | 43.50 |

| Submucosa (μm) | 30.67 | 31.29 | 41.67 | 40.00 | 58.50 | 52.67 |

| Mucosa (μm) | 91.33 | 61.57 | 96.50 | 75.67 | 100.00 | 68.33 |

Morphologies of collagen networks

We established composite histograms with corresponding Von Mises fits for the colonic, intermediate, and rectal sections, respectively, for all layers and treatments, see Figs. 4–7. We provided the fitted data from the histograms of each individual layer for all specimens and for the (averaged) composite in Tables 2–4. We could not clearly distinguish the lateral (axial) muscle layer from the serosa layer in the images at 20x, and thus we pooled these data.

Figure 4.

Composite (overall) histograms of the orientation of fibers in the colonic segments for (a-b) the serosa, (c-d) the muscle layer, and (e-f) submucosa for both the (a,c,e) reference and (b,d,f) deformed configurations. The black line indicates the fitted Von Mises distribution.

Figure 7.

Fiber diameters of specimens from the colonic, intermediate, and rectal locations for the serosa, axial and circumferential muscle layers, and the submucosa. The * indicates a significance difference between the layers.

Table 2.

Fitted parameters for the mean fiber orientations (μi) and fiber dispersions (κi) for up to two families of fibers (i = 1,2) for the three mechanically relevant layers (serosa, muscle, submucosa) at the colonic location along the intestine. NA denotes missing data, i.e. we only successfully prepared, imaged, and analyzed five specimens. Isotropic denotes specimens with no predominant fiber orientation.

| Colonic | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference |

Deformed |

||||||||

| μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | ||

| serosa | - | - | |||||||

| 1 | 81.66 | 6.00 | - | - | 71.41 | 2.29 | - | - | |

| - | |||||||||

| 2 | 80.41 | 5.11 | - | - | 88.35 | 6.29 | - | - | |

| - | - | 11.4 | 64.9 | 10.8 | |||||

| 3 | 27.62 | 0.62 | - | - | 43.85 | 6 | 6 | 0 | |

| 10.9 | |||||||||

| 4 | 0.31 | 3 | - | - | 87.27 | 6.39 | - | - | |

| 79.5 | |||||||||

| 5 | 86.37 | 1.34 | - | - | 0.22 | 4.45 | 0 | 2.40 | |

| - | |||||||||

| 6 | 24.55 | 1.25 | - | - | NA | ||||

| C | Isotropic | 90.00 | 1.76 | ||||||

| muscle | 60.0 | - | 20.0 | 49.9 | 17.9 | ||||

| 1 | 0.67 | 0 | 72.68 | 5.08 | −1.83 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 60.0 | |||||||||

| 2 | 2.78 | 0 | - | - | −4.40 | 0.10 | - | - | |

| 60.0 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.75 | 0 | - | - | 0.74 | 1.30 | - | - | |

| 16.4 | - | 60.0 | 40.1 | ||||||

| 4 | −1.07 | 1 | 82.00 | 0 | 3.99 | 7 | - | - | |

| 50.7 | 19.4 | 29.2 | |||||||

| 5 | 2.75 | 3 | - | - | 0.49 | 4 | 8 | 2.96 | |

| 27.6 | |||||||||

| 6 | −3.54 | 3 | 32.44 | 3.93 | NA | ||||

| C | 0.13 | 35.0 1 |

- | - | 3.98 | 16.2 3 |

- | - | |

| submucosa | - | - | 60.5 | ||||||

| 1 | 70.42 | 1.42 | - | - | 60.56 | 6.13 | 7 | 3.09 | |

| - | |||||||||

| 2 | 39.18 | 1.04 | - | - | 71.01 | 1.39 | - | - | |

| - | - | 40.3 | |||||||

| 3 | 31.94 | 3.77 | 29.78 | 0.87 | 33.25 | 3.47 | 3 | 2.64 | |

| - | 20 | ||||||||

| 4 | 14.20 | 0.86 | - | - | 74.42 | 0.95 | - | - | |

| 5 | −1.03 | 5.26 | 52.70 | 2.39 | 65.79 | 1.55 | - | - | |

| 6 | 41.70 | 1.04 | - | - | NA | ||||

| - | 68.8 | ||||||||

| C | Isotropic | 58.84 | 3.23 | 4 | 3.23 | ||||

Table 4.

Fitted parameters for the mean fiber orientations (μi) and fiber dispersions (κi) for up to two families of fibers (i = 1,2) for the three mechanically relevant layers (serosa, muscle, submucosa) at the rectal location along the intestine. NA denotes missing data, i.e. we only successfully prepared, imaged, and analyzed five specimens. Isotropic denotes specimens with no predominant fiber orientation.

| Rectal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference |

Deformed |

||||||||

| μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | ||

| serosa | 1 | 64.72 | 10.27 | - | - | 61.04 | 0.82 | - | - |

| 2 | Isotropic | 26.43 | 3.26 | - | - | ||||

| 2.6 | |||||||||

| 3 | 7.97 | 0.46 | - | - | 13.49 | 8.46 | 66.70 | 7 | |

| 4 | 67.26 | 1.90 | - | - | −83.89 | 2.57 | - | - | |

| 5 | Isotropic | 36.13 | 0.52 | - | - | ||||

| 6 | −45.73 | 1.05 | - | - | −71.13 | 2.23 | - | - | |

| C | 50.91 | 0.94 | - | - | Isotropic | ||||

| muscle | 1 | 1.51 | 40.32 | - | - | −0.49 | 5.15 | - | - |

| 2 | 0.39 | 8.76 | 81.52 | 15.75 | 3.04 | 17.60 | - | - | |

| 3 | 1.92 | 25.03 | 83.41 | 3.58 | 3.00 | 60.00 | - | - | |

| 4 | 4.54 | 4.82 | - | - | 0.58 | 34.60 | - | - | |

| 5 | 1.07 | 31.58 | - | - | 11.40 | 4.12 | - | - | |

| 1.0 | |||||||||

| 6 | 0.22 | 60.00 | - | - | 1.89 | 60.00 | −74.64 | 0 | |

| C | 1.63 | 41.55 | - | - | 3.78 | 10.48 | - | - | |

| submucosa | 1 | 43.43 | 1.44 | - | - | −59.68 | 0.84 | - | - |

| 2 | −45.77 | 1.03 | - | - | 20.97 | 2.44 | - | - | |

| 3 | Isotropic | −47.75 | 0.87 | - | - | ||||

| 4 | 29.13 | 0.41 | - | - | Isotropic | ||||

| 5 | 0.00 | 0.95 | - | - | 79.58 | 0.94 | - | - | |

| 6 | Isotropic | 88.35 | 1.66 | - | - | ||||

| C | Isotropic | Isotropic | |||||||

The serosa layer typically presented a single peak in individual specimens in the reference configurations. These same specimens then often presented two peaks (or even isotropic distributions) in the deformed configurations. In our analyses of the serosa layers we found differences between the individual specimens and our averaged composite.

The muscle layers presented a dominant peak at 0° across all specimens (high b), i.e. these are predominantly the circular muscle layer. We found that configuration (reference vs. deformed) did not influence the principal fiber orientation meaningfully, indicating that the muscle fibers are highly aligned in the reference configuration. Some individual specimens did present additional peaks of smaller amplitudes and higher dispersions. The averaged composite does represent the individual specimen well.

The submucosa layers generally presented significant dispersion through the thickness and different locations of the largest peak. Thus we found deviations among the individual specimens compared to the composite overall data, e.g. the composite histogram for the colonic specimen at reference configuration appears isotropic, while most individual specimens present one or two peaks.

Diameters of fibers

Comparing the fibers in the layers, submucosa had the largest diameters in all segments (colonic, intermediate, rectal), followed by fibers in the serosa and fibers in the muscle layers, see Fig. 7. Fiber diameters in all three layers (grouping circumferential and axial muscle layers) showed significant differences (three-way ANOVA, F2,3810 = 11.6, P < 0.001). However, comparing corresponding fibers in the colonic vs. rectal segments showed no significant differences (Post hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 0.139 μm, t = 2.344, P = 0.057). The supporting collagen fibers in the muscle layers were statistically indistinguishable. We only observed a marginal influence of our inflation treatment on the fiber diameter (difference in means = 0.23 μm) and thus pooled those results in Fig. 7.

Fiber diameters in specimens in the reference vs. deformed (stretched) configurations showed significant differences (3-way ANOVA, F1,3810 = 24.014, P < 0.001). As an example, fiber diameters in the serosa layers in the colonic and intermediate segments showed a significant difference between the reference and deformed configurations (Post hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 0.814 μm, t = 4.772, P < 0.001 for colonic, and Difference of Means = 0.6 μm, t = 3.493, P < 0.001 for Intermediate). Additionally, fiber diameters in the lateral (axial) muscle layers in the colonic and rectal segments showed a significant difference between the reference and deformed configurations (Post hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 0.638 μm, t = 4.007, P < 0.001 for colonic, and Difference of Means = 0.706 μm, t = 3.661, P < 0.001 for rectal). Moreover, fiber diameters for the submucosa layer in the intermediate segment showed a significant difference between the reference and deformed configurations (Post hoc comparison, Difference of Means = 0.995 μm, t = 6.675, P < 0.001).

The power of our statistical analyses for configuration (reference, deformed), segment (colonic, intermediate, rectal), layer (serosa, circular muscle, submucosa), configuration vs. segment, configuration vs. segment, and configuration vs. segment are 0.998, 0.989, 1.000, 0.986, 0.999, and 0.999 respectively with α = 0.05.

Discussion

Images via second harmonic generation confocal microscopy

Our microscopy setups allowed label free imaging, highly specific to collagen fibers, through the entire thickness of our specimens (Schriefl et al., 2012a; Schriefl et al., 2012b). We reported that the SHG signal strength in the submucosal layer is more than one order of magnitude higher than in the other sub-layers of mouse colorectum. The colorectal wall can be separated into inner and outer composite layers from the submucosal space (Siri et al., 2019b). The outer composite consists of two muscular layers and was traditionally considered load-bearing, whereas the inner composite consists mostly of the wavy mucosa and was considered inferior in mechanical strength versus the outer composite.

Our recent study using biaxial extension tests revealed a surprising load-bearing function of the inner composite: the mechanical stiffness of the inner composite is comparable to that of the corresponding outer composite, and the axial mechanical stiffness is larger in the inner composite than in the outer (Siri et al., 2019b). As revealed in our current study, submucosa contains concentrated collagen fibers relative to all other locations in the colorectum, and thus is likely the principal load-bearing structure of the inner composite. In addition, submucosa is relatively thin occupying only ~20% of the colorectal wall thickness which, in combination with its high collagen contents, indicates that mechanical stresses in the submucosa are likely much larger than in other layers.

In parallel, we recently labeled sensory neurons using a non-biased genetic promoter VGLUT2 and discovered that the density of sensory nerve endings in the submucosa is much higher than that in the muscular layers and the mucosa (Shah et al., 2018). The concentrated presence of sensory nerve endings at the region of concentrated mechanical stresses in the colorectum strongly indicates the nociceptive roles of nerve endings in detecting catastrophic mechanical failure of the colorectum to inform the central nervous system.

Analyses of images and statistical analyses

Thicknesses of layers

The wall of colorectum consists of, from external to internal, anatomically distinct serosal, circular muscular, longitudinal muscular, submucosal, and mucosal (sub-) layers. In the mouse model, many of the sub-layers are too thin (<40 μm) to study by sections parallel to the plane of the layers. Additionally, multiple sections perpendicular to the plane of the layer distorts the relevant microstructure and affects quantification of collagen fibers within. In our current study, we determined the micromechanical environments within each layer of mouse colorectum by nonlinear optical measurements through the thickness of the colorectal wall via SHG. This approach removed the need to section the tissue, thus preserved the integrity of the networks of collagen fibers within each sub-layer.

We assessed the impact of noxious intraluminal pressure on the thickness of the colorectal layers. We established that distension-induced wall thinning of the colorectum stems mostly from reduced thickness of the serosa. In contrast, the four remaining layers showed no significant reductions in thickness following 60 mmHg intraluminal distension. This finding suggests that submucosa, serosa, and the two muscular layers act as fiber-reinforced, composite structures with significant stiffness. In support, a recent study indicates that both aortic adventitia and intestinal submucosa consist of fluid-filled interstitial space supported by a thick network of collagen fibers (Benias et al., 2018).

Morphologies of collagen networks

We were the first to systematically quantify the orientation, morphology, and content of collagen fibers from intact colorectal wall. We determined the statistical distributions of collagen fiber orientations in all five layers. In the circular and longitudinal muscular layers, the collagen fibers aligned with the orientations of smooth muscle fibers in the circular and longitudinal directions, respectively, as reflected by a single distinct peaks in the distribution plots. In contrast, the distribution in fiber orientations within the mucosal layer does not present distinct peaks, reflecting that these fibers align principally with the basal tubular structures of the crypt.

In colorectums distended by 60 mmHg intraluminal pressure, collagen fibers in the submucosa of the colonic region demonstrates two dominant orientations aligned approximately ±30 degrees from the longitudinal (axial) direction, consistent with two prior studies showing similar fiber orientations in the submucosa of rat small intestine (Orberg et al., 1983; Orberg et al., 1982). These two families of fibers crisscross one another to form a fiber network that complicates the micromechanical environment in the submucosa, which is also heavily innervated by sensory nerve endings.

In contrast to dominant orientations in the colonic submucosa, we observed irregular patterns of collagen fiber orientations in the submucosal layers of the intermediate and rectal segments without any dominant orientations. This likely reflects the different functions in colorectal neural encoding within the colonic and rectal segments, which are predominately innervated by the lumbar splanchnic and pelvic nerves, respectively (Siri et al., 2019a). The lumbar splanchnic nerve and the major mesenteric arteries also enter the distal colorectum via the intermediate segment, which likely accounts for the irregular collagen fiber patterns in the intermediate submucosa.

SHG is commonly used for imaging non-birefringent biological tissues and tissue components, the most common example being collagen (Theodossiou et al., 2006; Zipfel et al., 2003), and is considered a reliable method to nondestructively image collagen within soft tissues (Fung et al., 2010; Theodossiou et al., 2006). Virtually all types of collagen produce SHG signals, and SHG can specifically reveal the two-dimensional and three-dimensional networks/structures of collagen (Brown et al., 2003). Mao et al. validated the specificity of SHG imaging for collagen fibers by conducting multimodal imaging using both Masson’s trichrome staining and SHG to detect collagen fibers in intestinal tissues (Mao et al., 2016). They confirmed that SHG and trichromatic staining detects comparable patterns of collagen fibers.

Previous reports of collagen in intestinal tissues generally included chromatic or fluorescent staining on sections of tissue around 10–40 μm in thickness (Graham et al., 1988). These staining methods were not intended to systematically determine the collagen fiber network in all layers of the colorectum, but to serve for other purposes. For example, studies applying Masson’s trichrome staining and Haematoxylin & Eosin (H & E) staining revealed the significant increase in type I, III, and V collagens in strictured intestine following chronic enteric Salmonella infection (Grassl et al., 2008). Other studies implemented polarization microscopy of sections stained with Picrosirius red to qualitatively evaluate the collagen within the intestinal wall and thus to follow the healing of anastomotic sites or diagnose collagen pathology (Rabau and Dayan, 1994). An additional study used staining with both H & E and Pyrofuchsin to assess the small intestines of patients with chronic heart failure by focusing on accumulation of collagen and subsequent dysfunction of the mucosal barrier (Arutyunov et al., 2008).

Diameters of fibers

The diameters of collagen fibers were significantly greater in the submucosa than in other layers, further supporting the dominant load-bearing role of the submucosa. As anticipated, the collagen fibers in the submucosa were curly when the colorectum was not distended (reference configuration), similar to fibers in other biological tissues that only undergo meaningful mechanical loading beyond a specific recruitment stretch (Nesbitt et al., 2015).

The diameters of collagen fibers were unchanged by noxious mechanical colorectal distension. Our measurements have a pixel resolution of 0.104 μm/pixel for our 40× images. In our statistical analyses of the fiber diameters, we only considered differences in means greater than 5 pixels as physically significant, i.e. 0.52 μm served as our threshold for reliable detection.

Limitations and outlook

The muscle layers presented a dominant peak at 0° across all specimens (high b parameter), but some individual specimens did present additional peaks of smaller amplitudes and higher dispersions. The additional peaks most likely originate from interference of the surrounding layers, i.e. the submucosa, intermuscularis, and axial muscle layers. Considering the large field off view (approximately 2 mm) and the relatively thin specimens, it is likely we did not image exactly through the thickness but at a slight tilt potentially causing multiple layers to appear within individual images. We removed five images at the beginning and at the end of each interface between layers to reduce this interference. In reviewing individual images from tissue layers, there was sometimes variability in the location and number of peaks, e.g. we could typically observe one or two distinct fiber families. However, in combining these data to generate composite overall data we sometimes washed out these sample-specific details.

We conducted nonlinear imaging via SHG to quantify the thickness of each distinct through-thickness layer of the colorectum, as well as the principal orientations, corresponding dispersions in orientations, and the distributions of diameters of collagen fibers within each of these layers. Our results reveal that submucosa is relatively thin, occupying only ~20% of the colorectal wall thickness, and contains a relatively high concentration of collagen and thus is likely the principal load-bearing structure of the inner mucosal-submucosal composite. Our results will facilitate analyses of both fundamental questions (e.g. structure-function relationships) and specific applications (e.g. device design in biomedical research). Furthermore, our quantitative results (measured parameters) also provide data for calibrating and/or validating computational models of colorectum, e.g. informing finite element analyses considering the longitudinal and through-thickness heterogeneity present in the colons of mice. Further studies should focus on the interaction between collagen fibers and nerve endings in the submucosa, which is likely to play a key role in colorectal mechanotransduction and especially mechano-nociception.

Figure 5.

Composite (overall) histograms of the orientation of fibers in the intermediate segments for (a-b) the serosa, (c-d) the muscle layer, and (e-f) submucosa for both the (a,c,e) reference and (b,d,f) deformed configurations. The black line indicates the fitted Von Mises distribution.

Figure 6.

Composite (overall) histograms of the orientation of fibers in the rectal segments for (a-b) the serosa, (c-d) the muscle layer, and (e-f) submucosa for both the (a,c,e) reference and (b,d,f) deformed configurations. The black line indicates the fitted Von Mises distribution.

Table 3.

Fitted parameters for the mean fiber orientations (μi) and fiber dispersions (κi) for up to two families of fibers (i = 1,2) for the three mechanically relevant layers (serosa, muscle, submucosa) at the intermediate location along the intestine. NA denotes missing data, i.e. we only successfully prepared, imaged, and analyzed five specimens. Isotropic denotes specimens with no predominant fiber orientation.

| Intermediate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference |

Deformed |

||||||||

| μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | μ1(−) | κ1(−) | μ2(−) | κ2(−) | ||

| serona | 1 | −50.45 | 2.03 | - | - | Isotropic | |||

| 2 | −86.76 | 3.58 | - | - | Isotropic | ||||

| 3 | −52.51 | 1.67 | - | - | 0.96 | 1.63 | 71.41 | 18.34 | |

| 4 | Isotropic | 84.89 | 1.45 | - | - | ||||

| 5 | 13.10 | 0.51 | - | - | 74.08 | 1.18 | - | - | |

| 6 | NA | −4.16 | 37.63 | 87.64 | 2.11 | ||||

| C | −60.09 | 1.63 | - | - | −90.00 | 1.76 | - | - | |

| muscle | 60.0 | ||||||||

| 1 | 2.84 | 0 | −50.37 | 2.75 | 1.62 | 60.00 | - | - | |

| 37.7 | |||||||||

| 2 | 1.60 | 0 | 90.00 | 11.85 | Isotropic | ||||

| 48.8 | |||||||||

| 3 | 1.08 | 3 | - | - | 1.60 | 60.00 | - | - | |

| 60.0 | |||||||||

| 4 | 1.58 | 0 | - | - | 2.51 | 4.39 | - | - | |

| 51.9 | |||||||||

| 5 | 2.42 | 8 | - | - | 4.88 | 15.63 | - | - | |

| 6 | NA | Isotropic | |||||||

| 51.0 | |||||||||

| C | 1.50 | 0 | - | - | 1.00 | 60.00 | - | - | |

| submucosa | 1 | −37.03 | 1.44 | - | - | Isotropic | |||

| 2 | −72.46 | 0.97 | - | - | −36.87 | 11.28 | 62.55 | 2.63 | |

| 3 | Isotropic | 2.56 | 0.55 | - | - | ||||

| 4 | −84.99 | 1.21 | - | - | Isotropic | ||||

| 5 | −26.73 | 0.66 | - | - | −55.79 | 1.61 | 51.04 | 5.93 | |

| 6 | NA | −57.17 | 2.73 | 64.94 | 6.73 | ||||

| C | −58.84 | 1.08 | - | - | Isotropic | ||||

Article Highlights for JMBBM.

Instructions: 3–5 bullet points of 85 characters or less (including spaces) summarizing only the results of the paper

Via SHG, imaged layers within colorectums of mice: serosa, muscle, submucosa, mucosa

Quantified layers and layer-specific collagen morphologies in colorectums of mice

Mucosa was thickest in colonic, intermediate, rectal segments, followed by submucosa

Submucosa had largest fiber diameters in all segments, followed by serosa and muscle

Submucosa is thin, contains substantial collagen, and is a key load-bearing structure

Acknowledgment

This material is based upon work supported by NSF 1727185 and NIH 1R01DK120824–01.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

We have no conflicts of interest to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arutyunov GP, Kostyukevich OI, Serov RA, Rylova NV, Bylova NA, 2008. Collagen accumulation and dysfunctional mucosal barrier of the small intestine in patients with chronic heart failure. International journal of cardiology 125, 240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benias PC, Wells RG, Sackey-Aboagye B, Klavan H, Reidy J, Buonocore D, Miranda M, Kornacki S, Wayne M, Carr-Locke DL, Theise ND, 2018. Structure and Distribution of an Unrecognized Interstitium in Human Tissues. Scientific Reports 8, 4947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley SM, Carter R, Jones W III, Xu L, Robinson DR, Hicks GA, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA, 2005a. Differential chemosensory function and receptor expression of splanchnic and pelvic colonic afferents in mice. Journal of Physiology 567, 267–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley SM, Jones RC 3rd, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA, 2004. Splanchnic and pelvic mechanosensory afferents signal different qualities of colonic stimuli in mice. Gastroenterology 127, 166–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brierley SM, Jones RC III, Xu L, Gebhart GF, Blackshaw LA, 2005b. Activation of splanchnic and pelvic colonic afferents by bradykinin in mice. Neurogastroenterology and motility : the official journal of the European Gastrointestinal Motility Society 17, 854–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookes SJ, Spencer NJ, Costa M, Zagorodnyuk VP, 2013. Extrinsic primary afferent signalling in the gut. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 10, 286–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, McKee T, Pluen A, Seed B, Boucher Y, Jain RK, 2003. Dynamic imaging of collagen and its modulation in tumors in vivo using second-harmonic generation. Nature medicine 9, 796–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu S-W, Tai S-P, Liu T-M, Sun C-K, Lin C-H, 2009. Selective imaging in second-harmonic-generation microscopy with anisotropic radiation. Journal of biomedical optics 14, 010504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolber PC, Spach M, 1993. Conventional and confocal fluorescence microscopy of collagen fibers in the heart. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry 41, 465–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Gebhart GF, 2011. Characterization of silent afferents in the pelvic and splanchnic innervations of the mouse colorectum. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300, G170–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Gebhart GF, 2015. In vitro functional characterization of mouse colorectal afferent endings. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE, 52310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Guo T, 2020. Visceral pain from colon and rectum: the mechanotransduction and biomechanics. Journal of Neural Transmission 127, 415–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Joyce SC, Gebhart GF, 2016. Optogenetic activation of mechanically insensitive afferents in mouse colorectum reveals chemosensitivity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 310, G790–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Kiyatkin ME, La J-H, Ge P, Solinga R, Silos-Santiago I, Gebhart GF, 2013. Activation of Guanylate Cyclase-C Attenuates Stretch Responses and Sensitization of Mouse Colorectal Afferents. The Journal of Neuroscience 33, 9831–9839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, La J.-h., Schwartz ES, Tanaka T, McMurray TP, Gebhart GF, 2012a. Long-term sensitization of mechanosensitive and-insensitive afferents in mice with persistent colorectal hypersensitivity. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 302, G676–G683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, La J.-h., Schwartz ES, Tanaka T, McMurray TP, Gebhart GF, 2012b. Long-term sensitization of mechanosensitive and -insensitive afferents in mice with persistent colorectal hypersensitivity. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology 302, G676–G683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, La JH, Tanaka T, Schwartz ES, McMurray TP, Gebhart GF, 2012c. Altered colorectal afferent function associated with TNBS-induced visceral hypersensitivity in mice. American journal of physiology. Gastrointestinal and liver physiology 303, G817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung DT, Sereysky JB, Basta-Pljakic J, Laudier DM, Huq R, Jepsen KJ, Schaffler MB, Flatow EL, 2010. Second harmonic generation imaging and Fourier transform spectral analysis reveal damage in fatigue-loaded tendons. Annals of biomedical engineering 38, 1741–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness JB, 2012. The enteric nervous system and neurogastroenterology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9, 286–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser TC, Ogden RW, Holzapfel GA, 2006. Hyperelastic modelling of arterial layers with distributed collagen fibre orientations. J R Soc Interface 3, 15–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham MF, Diegelmann RF, Elson CO, Lindblad WJ, Gotschalk N, Gay S, Gay R, 1988. Collagen content and types in the intestinal strictures of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 94, 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassl GA, Valdez Y, Bergstrom KS, Vallance BA, Finlay BB, 2008. Chronic enteric salmonella infection in mice leads to severe and persistent intestinal fibrosis. Gastroenterology 134, 768–780. e762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiraly K, Hyttinen M, Lapvetelainen T, Elo M, Kiviranta I, Dobai J, Modis L, Helminen H, Arokoski J, 1997. Specimen preparation and quantification of collagen birefringence in unstained sections of articular cartilage using image analysis and polarizing light microscopy. The Histochemical journal 29, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilledahl MB, Pierce DM, Ricken T, Holzapfel GA, Davies C.d.L., 2011. Structural Analysis of Articular Cartilage Using Multiphoton Microscopy: Input for Biomechanical Modeling. TRANSACTIONS ON MEDICAL IMAGING 30, 1635–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell RM, Ford AC, 2012. Global Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 10, 712–721.e714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao H, Su P, Qiu W, Huang L, Yu H, Wang Y, 2016. The use of Masson’s trichrome staining, second harmonic imaging and two‐photon excited fluorescence of collagen in distinguishing intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Disease 18, 1172–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt S, Scott W, Macione J, Kotha S, 2015. Collagen fibrils in skin orient in the direction of applied uniaxial load in proportion to stress while exhibiting differential strains around hair follicles. Materials 8, 1841–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimni ME, Harkness RD, 1988. Molecular structures and functions of collagen. Collagen Volume I Biochemistry, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Orberg J, Baer E, Hiltner A, 1983. Organization of collagen fibers in the intestine. Connective tissue research 11, 285–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orberg J, Klein L, Hiltner A, 1982. Scanning electron microscopy of collagen fibers in intestine. Connective tissue research 9, 187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabau M, Dayan D, 1994. Polarization microscopy of picrosirius red stained sections. A useful method for qualitative evaluation of intestinal wall collagen. Histology and histopathology. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriefl AJ, Reinisch AJ, Sankaran S, Pierce DM, Holzapfel GA, 2012a. Quantitative assessment of collagen fibre orientations from two-dimensional images of soft biological tissues. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 9, 3081–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriefl AJ, Zeindlinger G, Pierce DM, Regitnig P, Holzapfel GA, 2012b. Determination of the layer-specific distributed collagen fibre orientations in human thoracic and abdominal aortas and common iliac arteries. Journal of the Royal Society Interface 9, 1275–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri S, Maier F, Chen L, Santos S, Pierce DM, Feng B, 2019a. Differential biomechanical properties of mouse distal colon and rectum innervated by the splanchnic and pelvic afferents. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 316, G473–G481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siri S, Maier F, Santos S, Pierce DM, Feng B, 2019b. The load-bearing function of the colorectal submucosa and its relevance to visceral nociception elicited by mechanical stretch. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer G, Schriefl AJ, Andra M, Sacherer M, Viertler C, Wolinski H, Holzapfel GA, 2015. Biomechanical properties and microstructure of human ventricular myocardium. Acta Biomater 24, 172–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer NJ, Kyloh M, Duffield M, 2014. Identification of different types of spinal afferent nerve endings that encode noxious and innocuous stimuli in the large intestine using a novel anterograde tracing technique. PLoS One 9, e112466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theer P, Hasan MT, Denk W, 2003. Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 μm in living brains by use of a Ti: Al 2 O 3 regenerative amplifier. Optics letters 28, 1022–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodossiou TA, Thrasivoulou C, Ekwobi C, Becker DL, 2006. Second harmonic generation confocal microscopy of collagen type I from rat tendon cryosections. Biophysical Journal 91, 4665–4677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognetti L, Carraro A, Lamberti A, Cinotti E, Suppa M, Luc Perrot J, Rubegni P, 2020. Kaposi sarcoma of the glans: New findings by line field confocal optical coherence tomography examination. Skin Res Technol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel B, Siebert H, Hofmann U, Frantz S, 2015. Determination of collagen content within picrosirius red stained paraffin-embedded tissue sections using fluorescence microscopy. MethodsX 2, 124–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Brisson BK, Terajima M, Li Q, Hoxha K, Han B, Goldberg AM, Liu XS, Marcolongo MS, Enomoto-Iwamoto M, Yamauchi M, Volk SW, Han L, 2020. Type III collagen is a key regulator of the collagen fibrillar structure and biomechanics of articular cartilage and meniscus. Matrix Biology 85–86, 47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenstrup RJ, Florer JB, Brunskill EW, Bell SM, Chervoneva I, Birk DE, 2004. Type V collagen controls the initiation of collagen fibril assembly. J Biol Chem 279, 53331–53337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittaker P, Canham PB, 1991. Demonstration of quantitative fabric analysis of tendon collagen using two-dimensional polarized light microscopy. Matrix 11, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Webb WW, 2003. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nature biotechnology 21, 1369–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]