Abstract

Importance:

Female sex is a major risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer Disease (AD), and sex hormones have been implicated as a possible protective factor. Neuroimaging studies that evaluated the effects of sex hormones on brain integrity have primarily emphasized neurodegenerative measures rather than amyloid and tau burden.

Objective:

We compared cortical amyloid and regional tau positron emission tomography (PET) deposition between cognitively normal males and females. We also compared preclinical AD pathology between females who have and have not used hormone therapy (HT). Finally, we compared the effects of amyloid and tau pathology on cognition, testing for both sex and HT effects.

Design, Setting, and Participants:

We analyzed amyloid, tau, and cognition in a cognitively normal cross-sectional cohort of older individuals (n = 148) followed at the Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center. Amyloid and tau PET, medication history, and neuropsychological testing were obtained for each participant.

Results:

Within cognitively normal individuals, there was no difference in amyloid burden by sex. Whether or not we controlled for amyloid burden, female participants had significantly higher tau PET levels than males in multiple regions, including the rostral middle frontal and superior and middle temporal regions. HT accounted for a small reduction in tau PET; however, males still had substantially lower tau PET compared to females. Amyloid PET and tau PET burden were negatively associated with cognitive performance, although increasing amyloid PET did not have a deleterious effect on cognitive performance for women with a history of HT.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Regional sex-related differences in tau PET burden may contribute to the disparities in AD prevalence between males and females. The observed decreases tau PET burden in HT users has important implications for clinical practice and trials and deserves future consideration in longitudinal studies.

INTRODUCTION

Estrogen may play a role in the development of symptomatic Alzheimer Disease (AD). Female sex is a major risk factor for late-onset AD1, and higher estrogen levels are linked to improved cognitive performance2. Women with decreased lifetime exposure to estrogen due to hysterectomy have a substantially greater risk of developing AD3. Female mouse models have also shown a depletion of sex hormones is associated with elevated amyloid, and hormone therapy (HT) reduces tau phosphorylation4.

Amyloid and tau are pathological hallmarks of AD. The Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) and Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) evaluated tau and amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) as a function of sex5. For ADNI but not HABS, females had higher regional tau PET deposition for a given level of amyloid PET burden. Although regional vulnerability to AD pathology may differ by sex, a global difference was not observed6,7.

The effects of estrogen on neuroimaging measures have primarily focused on neurodegeneration8,9. However, amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration (AT(N)) represent distinct phases in preclinical progression to AD7. It is important to consider the effects of sex on AT(N) biomarkers during preclinical stages.

We evaluated global amyloid and regional tau PET deposition in a cross-sectional cohort of cognitively normal individuals followed by the Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL) Knight Alzheimer Disease Research Center (ADRC). Using past medication history, we evaluated amyloid and tau PET burden in females who were or were not prescribed HT. Finally, we evaluated the effects of amyloid and tau PET on cognition, using the Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (PACC)10.

METHODS

Cognitively normal (Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) 0 participants (440 females, 333 males) were enrolled in imaging studies at the WUSTL Knight ADRC. Participants completed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET (Pittsburgh Compound B (PiB) and/or [18F]-Flortaucipir (AV1451)), genotyping for apolipoprotein ε4 (APOEε4), and cognitive assessment (PACC). A subset (n = 148) completed PiB and AV1451 within a 4 year window of cognitive assessment. The average time difference between measurements was 2.5 years.

Clinical visits were reviewed for each participant. At each visit, participants’ self-reported medication use was recorded. Female participants who reported using estradiol, estrogen, premarin, raloxifene, estrace, estrogens, prempro, estrogel, or fempatch were recorded as receiving HT. Dosage and duration were unavailable. This study was approved by the WUSTL Institutional Review Board, and each participant provided signed informed consent.

APOE Status

DNA samples were genotyped according to previously published methods11. Presence of the APOEε4 allele was included as a fixed effect in all linear models.

MRI Imaging

A T1-weighted magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo sequence was acquired on a 3T Siemens Trio scanner. Structural images were acquired using the ADNI protocol. MRI images were processed in FreeSurfer (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/).

PET Imaging

PET imaging followed previously published scanning protocols12. PET imaging utilized PiB for amyloid and AV1451 for tau. Images were processed using a PET Unified Pipeline (github.com/ysu001/PUP)13. Global amyloid burden was defined as the mean of lateral orbitofrontal, medial orbitofrontal, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, superior temporal, middle temporal, and precuneus amyloid burden14. FreeSurfer was used to segment 35 grey matter regions evaluated for tau burden, including amygdala, entorhinal cortex, inferior temporal region, and lateral occipital cortex. The cerebellar cortex was used as the reference region for both amyloid and tau PET. All regions were partial volume corrected for intracranial volume.

Cognitive Testing

During their clinical visit participants completed four tests comprising the PACC: the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, the Logical Memory IIa subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale, the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, and the Mini-Mental State Examination10. For each neuropsychological test, scores were converted to test-specific z-scores, and then a global z-score composite was calculated for each participant within the cohort by averaging the four scores. For inclusion, participants completed the PACC within a year of their corresponding PET scan.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic group differences between males and females were compared using t- and Chi-square tests. Amyloid and tau PET values were log transformed. A series of linear regressions on a region-by-region basis was performed for all segmented grey matter for tau PET (Eq. (1)).

| (1) |

We applied heteroskedasticity consistent estimators and Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons (alpha=0.05), adjusting for the 35 FreeSurfer regions assessed. We then calculated the marginal effect of both sex and HT usage on tau burden in each of the regions where there was a significant sex difference in tau PET burden. We performed a principal components analysis on regions where a significant sex effect on tau PET burden was observed. The eigenvector associated with the first principal component was multiplied by an individual’s regional tau burden to generate a summary value describing sex-differentiated pathology. Two separate linear models (Eq. 2) were used to test for effects of HT on amyloid and tau PET burden, respectively.

| (2) |

A summary was calculated in lieu of separate regional tests because regions were highly correlated. The marginal effects of sex and HT history were calculated on both this summary tau burden value, as well as cortical amyloid burden. To test for effects of pathology on cognition, a linear regression (Eq. 3) was performed. We applied heteroskedasticity consistent estimators, and subsequently calculated the marginal effects of sex and HT history on the linear models.

| (3) |

For all regression results reported, we calculated Cohen’s f2 effect size. Analyses were conducted using R with code available at https://github.com/jwisch/SexDifferences_HT.

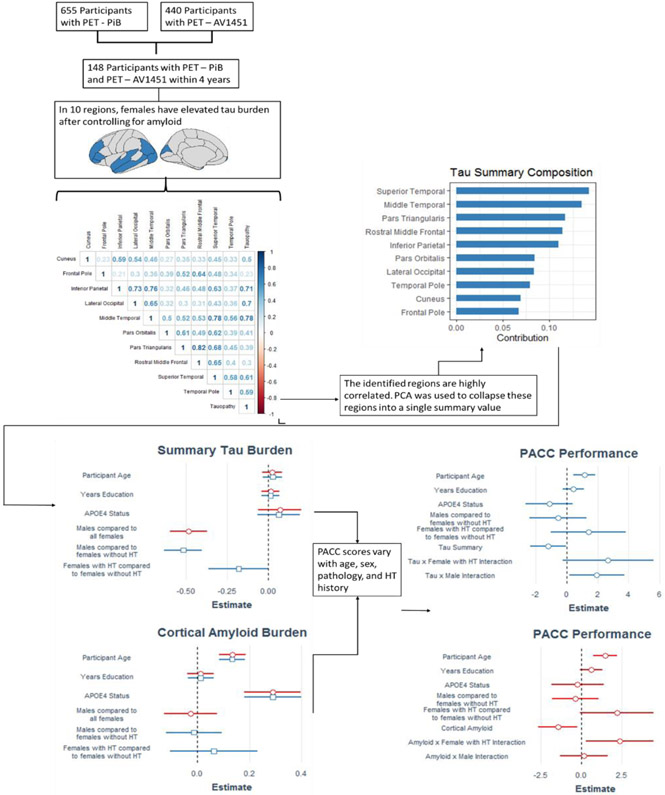

RESULTS

Demographics are presented in Table 1. The cohort was well-matched with respect to age, years of education, APOEε4, race, and cortical amyloid burden; however, females had significantly higher tau PET burden in ten regions (Supplemental Table) compared to males (p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction for 35 comparisons). The finding that females had greater tau PET burden in ten regions (Cuneus, Frontal Pole, Inferior Parietal, Lateral Occipital, Middle Temporal, Pars Orbitalis, Pars Triangularis, Rostral Middle Frontal, Superior Temporal and Temporal Pole) was robust whether or not amyloid PET burden was corrected. We calculated a tau summary value describing the tau PET burden in the ten regions identified as having sex differences. We performed PCA on the ten regions, identifying a summary value that was most heavily weighted towards the superior and middle temporal regions (Figure 1). We multiplied the eigenvector associated with the first principal component by each individual’s tau burden in the ten regions of interest, finding a summary measure of tau burden. Males had significantly reduced summary tau PET burden as compared to females (Cohen’s f2 = 0.309, p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Participant demographics and summaries of unadjusted pathology burden in selected regions. Participants were well matched on the basis of age, education and apolipoprotein (APOEε4) status. There were significant differences in regional tau burden, where females without a history of HT use had the highest tau positron emission tomography (PET) burden and males and the lowest tau PET burden

| Female, no HT |

Female, HT Use |

Male | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 70 | 16 | 62 | |

| Age (mean (sd)) | 68.47 (6.85) | 70.27 (8.11) | 70.12 (7.47) | 0.375 |

| Years Education (mean (sd)) | 16.19 (2.22) | 16.06 (2.64) | 16.23 (2.31) | 0.968 |

| APOEε4+ (%) | 20 (29.0) | 4 ( 25.0) | 21 (33.9) | 0.729 |

| Race (%) | 0.628 | |||

| Asian | 1 ( 1.4) | 0 ( 0.0) | 0 ( 0.0) | |

| African American | 4 ( 5.7) | 0 ( 0.0) | 5 ( 8.1) | |

| Non Hispanic White | 65 (92.9) | 16 (100.0) | 57 (91.9) | |

| Cortical Amyloid Burden (mean (sd)) | 0.20 (0.32) | 0.28 (0.43) | 0.23 (0.37) | 0.68 |

| Number of Amyoid Positive Participants (%) | 13 (18.6) | 4 ( 25.0) | 16 (25.8) | 0.586 |

| Tau Burden - Cuneus (mean (sd)) | 1.28 (0.14) | 1.22 (0.12) | 1.19 (0.16) | 0.003 |

| Tau Burden - Frontal Pole (mean (sd)) | 1.13 (0.32) | 1.08 (0.29) | 0.78 (0.24) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Inferior Parietal (mean (sd)) | 1.33 (0.19) | 1.28 (0.22) | 1.23 (0.19) | 0.011 |

| Tau Burden - Lateral Occipital (mean (sd)) | 1.33 (0.19) | 1.27 (0.25) | 1.15 (0.21) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Middle Temporal (mean (sd)) | 1.33 (0.19) | 1.29 (0.18) | 1.21 (0.17) | 0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Pars Orbitalis (mean (sd)) | 1.36 (0.20) | 1.25 (0.18) | 1.13 (0.24) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Pars Triangularis (mean (sd)) | 1.27 (0.20) | 1.24 (0.18) | 1.08 (0.18) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Rostral Middle Frontal (mean (sd)) | 1.12 (0.22) | 1.06 (0.19) | 0.89 (0.14) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Superior Temporal (mean (sd)) | 1.12 (0.17) | 1.06 (0.16) | 1.00 (0.13) | <0.001 |

| Tau Burden - Temporal Pole (mean (sd)) | 1.12 (0.20) | 1.07 (0.15) | 0.97 (0.19) | <0.001 |

| Tauopathy (mean (sd)) | 1.24 (0.20) | 1.19 (0.17) | 1.16 (0.20) | 0.078 |

Females with a history of hormone therapy (HT) were older than females with no HT. SD= standard deviation, APOE ε4= apolipoprotein ε4

Figure 1.

148 individuals were identified to have completed the requisite imaging for participation in this study. All amyloid PET, tau PET, and neuropsychological measures were collected within 4 years of one another. Within this cohort, females had greater tau PET burden than males after controlling for amyloid PET burden in the following regions: cuneus, frontal pole, inferior parietal, lateral occipital, middle temporal, pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, rostral middle frontal, superior temporal, and temporal pole. After correcting for multiple comparisons, these sex differences persisted. In order to maximize power, the 10 identified regions associated with greater tau PET burden in females were collapsed into a single summary value via principal components analysis. While there were no significant sex differences with respect to amyloid burden, males had significantly decreased tau PET across the summary regions (Cohen’s f2 = 0.309, p < 0.001). Females with a history of HT also had lower tau PET burden in these regions than females who had not used HT (Cohen’s f2 = 0.041, p = 0.059). These differences in pathology burden and historical HT usage had significant effects on cognitive performance. Increases in amyloid PET burden are associated with poorer PACC performance; however, having a history of HT usage effectively negates the deleterious impact of amyloid. Increases in tau PET burden are also associated with poorer PACC performance, but females without a history of HT see the greatest negative cognitive impact.

After assessing overall sex differences, we compared women who had taken HT to those who had not taken HT. There were no differences on a region-by-region basis between females who had or had not taken HT after correction for multiple comparisons. There was trend level evidence to suggest that females who had a history of HT may have a small reduction in tau PET burden (Cohen’s f2 = 0.041, p = 0.059). Age did not differentiate women who had taken HRT versus those who did not and may reflect historically changing recommendations on HT use (see Supplemental Table 1).

PACC performance was inversely associated with both pathologic measures: global amyloid PET burden (Cohen’s f2 = 0.081, p =0.017) and summary tau PET (Cohen’s f2 = 0.043, p = 0.018). There were no significant differences in PACC performance by sex; however, females with a history of HT performed better than females without HT after controlling for amyloid PET (Cohen’s f2 = 0.081, p = 0.043), but not tau PET (Cohen’s f2 = 0.119, p = 0.254). There was also a significant and positive interaction for females with a history of HT and amyloid PET burden (Cohen’s f2 = 0.081, p = 0.033).

DISCUSSION

Consistent with prior studies we did not identify a baseline sex difference in amyloid PET5,6. There was a large sex effect on regional tau PET burden. Whether or not controlling for global amyloid pathology, this difference persisted. Regional differences in tau PET burden due to sex are similar to prior reports5. This study extends previous findings by examining the link between sex hormones, suggesting that HT may be associated with reduced tau burden in females. Previous epidemiological work has identified a protective effect of HT15; however, relatively few studies have evaluated the protective effects of HT on biomarkers of AD, including amyloid and tau.

Further, these measures of pathology appear relevant to cognitive functioning. There was a significant decline in cognitive performance with increasing AD pathology for both males and females without HT usage; however, females with HT did not exhibit decreasing PACC scores even with elevated cortical amyloid PET burden. However, the sample size was small and larger studies are needed.

In this observational study, we employed self-reported data to identify HT usage. A limitation of is that the duration of HT is unknown. Longitudinal studies following hormone levels and menopause onset (e.g. 8,9) are needed to delineate the effects of sex hormones on tau PET burden. Future work that unifies attention to sex hormone levels with PET imaging is necessary, as this study suggests the importance of sex hormones on cognitive functioning and AD pathology.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question: Is there a sex-linked difference in tau burden?

Findings: Cognitively normal males have greater global amyloid burden; however, older females have significantly higher levels of tau positron emission tomography (PET) burden in the cuneus, frontal pole, inferior parietal, lateral occipital, pars orbitalis, pars triangularis, rostral middle frontal, and superior temporal regions, regardless of amyloid PET burden. Females with a history of hormone therapy (HT) have lower tau burden in these regions compared to females without HT.

Meaning: Regional sex-related differences in tau PET burden may contribute to the disparities in AD prevalence between males and females; however, HT may have a protective effect, which deserves further study.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was funded by the National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01NR012907 (BA), R01NR012657 (BA), R01NR014449 (BA), P01AG00391 (JCM), P01AG026276 (JCM), and P01AG005681 (JCM). This work was also supported by the generous support of the Barnes-Jewish Hospital; the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences Foundation (UL1 TR000448); the Hope Center for Neurological Disorders; the Paula and Rodger O. Riney Fund; the Daniel J Brennan MD Fund; and Fred Simmons and Olga Mohan Fund.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

Julie K. Wisch reports no disclosures

Karin L. Meeker reports no disclosures

Brian A. Gordon reports no disclosures

Shaney Flores reports no disclosures

Aylin Dincer reports no disclosures

Elizabeth A. Grant reports no disclosures

Tammie L. Benzinger is a site investigator on clinical trials with Biogen, Roche, Jaansen, and Eli Lilly. She receives research support from Eli Lilly and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. Avid Radiopharmaceuticals provided the 18-F-AV-45 doses and assisted with scanning expenses, and provided precursor and technology transfer for the 18F-AV-1451 doses which were used in this study.

John C. Morris reports no disclosures.

Beau M. Ances reports no disclosures.

References

- 1.Gao S, Hendrie HC, Hall KS, Hui S. The relationships between age, sex, and the incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease: A meta-analysis. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1998;55(9):809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pike CJ. Sex and the development of Alzheimer’s disease [Internet]. J. Neurosci. Res 2017;95(1–2):671–680.[cited 2019 Dec 17 ] Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/jnr.23827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgakis MK, Beskou-Kontou T, Theodoridis I, et al. Surgical menopause in association with cognitive function and risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2019;106:9–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll JC, Rosario ER, Chang L, et al. Progesterone and estrogen regulate Alzheimer-like neuropathology in female 3xTg-AD mice. J. Neurosci 2007;27(48):13357–13365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buckley RF, Mormino EC, Rabin JS, et al. Sex Differences in the Association of Global Amyloid and Regional Tau Deposition Measured by Positron Emission Tomography in Clinically Normal Older Adults. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):542–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckley RF, Mormino EC, Chhatwal J, et al. Associations between baseline amyloid, sex and APOE on subsequent tau accumulation in cerebrospinal fluid [Internet]. Neurobiol. Aging 2019;[cited 2019 Mar 18 ] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197458019300697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Age-specific and sex-specific prevalence of cerebral β-amyloidosis, tauopathy, and neurodegeneration in cognitively unimpaired individuals aged 50–95 years: a cross-sectional study [Internet]. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(6):435–444.[cited 2018 Dec 6 ] Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442217300777#! [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Low LF, Anstey KJ, Maller J, et al. Hormone replacement therapy, brain volumes and white matter in postmenopausal women aged 60-64 years. Neuroreport 2006;17(1):101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schönknecht P, Henze M, Hunt A, et al. Hippocampal glucose metabolism is associated with cerebrospinal fluid estrogen levels in postmenopausal women with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychiatry Res. - Neuroimaging 2003;124(2):125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, et al. The Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite Measuring Amyloid-Related Decline. 2019;0949(8):961–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castellano JM, Kim J, Stewart FR, et al. Human apoE isoforms differentially regulate brain amyloid-β peptide clearance [Internet]. Sci. Transl. Med 2011;3(89)[cited 2019 Dec 17 ] Available from: www.ScienceTranslationalMedicine.org [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: Potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease [Internet]. Neurology 2006;67(3):446–452.[cited 2019 Dec 17 ] Available from: http://www.neurology.org/cgi/content/full/67/3/446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Su Y, Blazey TM, Snyder AZ, et al. Partial volume correction in quantitative amyloid imaging. Neuroimage 2015;107:55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Su Y, D’Angelo GM, Vlassenko AG, et al. Quantitative analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLoS One 2013;8(11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zandi PP, Carlson MC, Plassman BL, et al. Hormone replacement therapy and incidence of Alzheimer disease in older women: The Cache County Study. J. Am. Med. Assoc 2002;288(17):2123–2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.