Abstract

Objective:

Our objectives were to explore attitudes regarding food retail policy and government regulation among managers of small food stores and examine whether manager views changed due to the 2014 Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance, a city policy requiring retailers to stock specific healthy products.

Design:

Manager interviewer-administered surveys were used to assess views on food retail policy four times from 2014 to 2017. We examined baseline views across manager and store and neighbourhood characteristics using cross-sectional regression analyses and examined changes over time using mixed regression models. In 2017, open-ended survey questions asked about manager insights on the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance.

Setting:

Minneapolis, MN, where the ordinance was enacted, and St. Paul, MN, a control community, USA.

Participants:

Managers from 147 small food retail stores.

Results:

At baseline, 48 % of managers were likely to support a policy requiring stores to stock healthy foods/beverages, 67·5 % of managers were likely to support voluntary programmes to help retailers stock healthy foods and 23·7 % agreed government regulation of business is good/necessary. There was a significant increase in overall support for food retail policies and voluntary programmes from 2014 to 2017 (P < 0·01); however, neither increase differed by city, suggesting no differential impact from the ordinance. Minneapolis store managers reported some challenges with ordinance compliance and offered suggestions for how local government could provide support.

Conclusions:

Findings suggest that managers of small food retail stores are becoming increasingly amenable to healthy food policies; yet, challenges need to be addressed to ensure healthy food is available to all customers.

Keywords: Food retail, Corner stores, Store managers, Policy views

Access to healthy foods is important for the promotion of healthy food choices, yet access remains unequal in the US – both among low-income communities and communities of colour(1,2). Small food stores, such as corner stores, gas stations and pharmacies, are prominent in these communities, and efforts to increase healthy foods in these venues increasingly recognise store managers as key players(1,3–5). Numerous voluntary intervention programmes have aimed to increase the healthfulness of foods available in stores via manager, owner and/or other stakeholder engagement; these demonstrated modest effects on availability and sales of healthy food(3,5). As store managers and owners play a critical role in the success of these interventions(4), it is important to understand the perceptions they hold around these and other healthy food retail interventions, including policy. Exploring how amenable managers are to various forms of intervention may help inform the types of strategies to consider in improving healthy food access.

To date, limited research has described perspectives that small food retail managers have about healthy food retail programmes and policies. Previous research describing managers’ policy perspectives has focused on reactions to federal policy change, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children requirements(5–9). Results indicate changes that widen retailers’ customer base and increase demand are positively favoured among management(5–8). For example, major Women, Infant and Children program policy changes in 2009 were perceived positively by retailers, as use of Women, Infant and Children program benefits is a major source of revenue for many retailers(5,6,10). However, it remains unclear whether similarly favourable views about policy are held among managers required to stock certain healthful products, rather than electing to participate in a programme that can practically assure revenue increases(6).

The current study examined retailer views about local food policy as part of the STaple Foods ORdinance Evaluation (STORE) study – a natural experiment evaluating impact of the 2014 Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance. In 2008, the Minneapolis City Council passed the first ordinance of its kind, which required all grocery-licensed stores to stock staple foods(11). In 2014, it was significantly revised to include minimum stocking requirements for ten product categories, such as fruits, vegetables, whole-grain products and low-fat dairy, and quality standards for perishable items(11). Despite significant input from retailers in developing ordinance language, STORE study data indicated few stores had yet fully complied with the revised ordinance in the 3 years following implementation(11). As such, understanding retailer views about local policy and other policy scenarios could help inform development of future policies to improve the healthfulness of local food retail.

The purpose of this study was to examine views about local food retail policy and government regulation among managers of small food stores. We examined whether views varied by manager, store, neighbourhood and city characteristics and investigated whether manager views changed over time or as a result of the 2014 Staple Food Ordinance. We also explored views specific to the 2014 Ordinance as described by store managers directly affected by the ordinance.

Methods

Study design and population

Data were derived from the STORE study, which collected data over four time points: pre-policy (July–December 2014, time 1) and three post-implementation time points, including September–October 2015 (time 2, implementation only, no enforcement), May–July 2016 (time 3, initiation of enforcement) and August–December 2017 (time 4, continued monitoring)(11). Data were collected from stores in Minneapolis (i.e. where the ordinance was enacted) and in an adjacent city, St. Paul, Minnesota, USA, which served as the study’s comparison. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Sampling procedures for STORE have been previously described(11). In total, 155 stores participated in the study at one or more time points, of which 54 % of stores were in Minneapolis and 46 % were in St. Paul. At each time, managers were asked to participate in an interviewer-administered survey. Across four time points, 147 stores had a manager to participate at least once and 57 % of these stores were in Minneapolis and 43 % were in St. Paul (n 412 observations). The store types that remained in the sample after applying exclusion criteria include pharmacies, convenience or small food stores, gas stations, dollar stores and general merchandisers.

Data collection and measures

Data collection for STORE has been previously described(11). In this analysis, we examined three measurement domains – manager characteristics, store and neighbourhood characteristics, and manager views on policy and regulation. Manager characteristics were collected via an interviewer-administered survey, adapted from previous research and piloted prior to data collection (online Supplementary Appendix A). Manager views on local food retail policy and government regulation were also collected via the interviewer-administered survey and were assessed as close-ended questions at time 1–4 and open-ended questions at time 4. Close-ended items measured support for a stocking policy, support for a program to assist stores in providing fresh produce, and agreement that government regulation of business is good/needed (12,13). Open-ended items included five questions specific to the 2014 Minneapolis Ordinance (online Supplementary Appendix A).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted in SAS (SAS/STAT version 9.4). We first computed descriptive statistics for all manager characteristics across the four time points. Using time 1 data, we computed an unadjusted linear regression model to examine managers’ support of food retail policy and government regulation across manager, store and neighbourhood characteristics. We then tested changes in manager views over the four time points across the two cities, by computing mixed model regression analyses adjusting for covariates and repeated measures over time.

We analysed data gathered from time 4 open-ended questions using content analysis techniques. There were fifty-one managers who provided data at time 4 and whose stores were affected by the ordinance, that is, those in Minneapolis. We analysed responses from all five items together and coded responses using a data-derived coding system. Following multiple rounds of discussion with three authors (C.M.M., M.R.W., M.N.L.), we organised codes into two overarching categories (Challenges and Proposed Solutions).

Results

Manager characteristics and views on policy and regulation

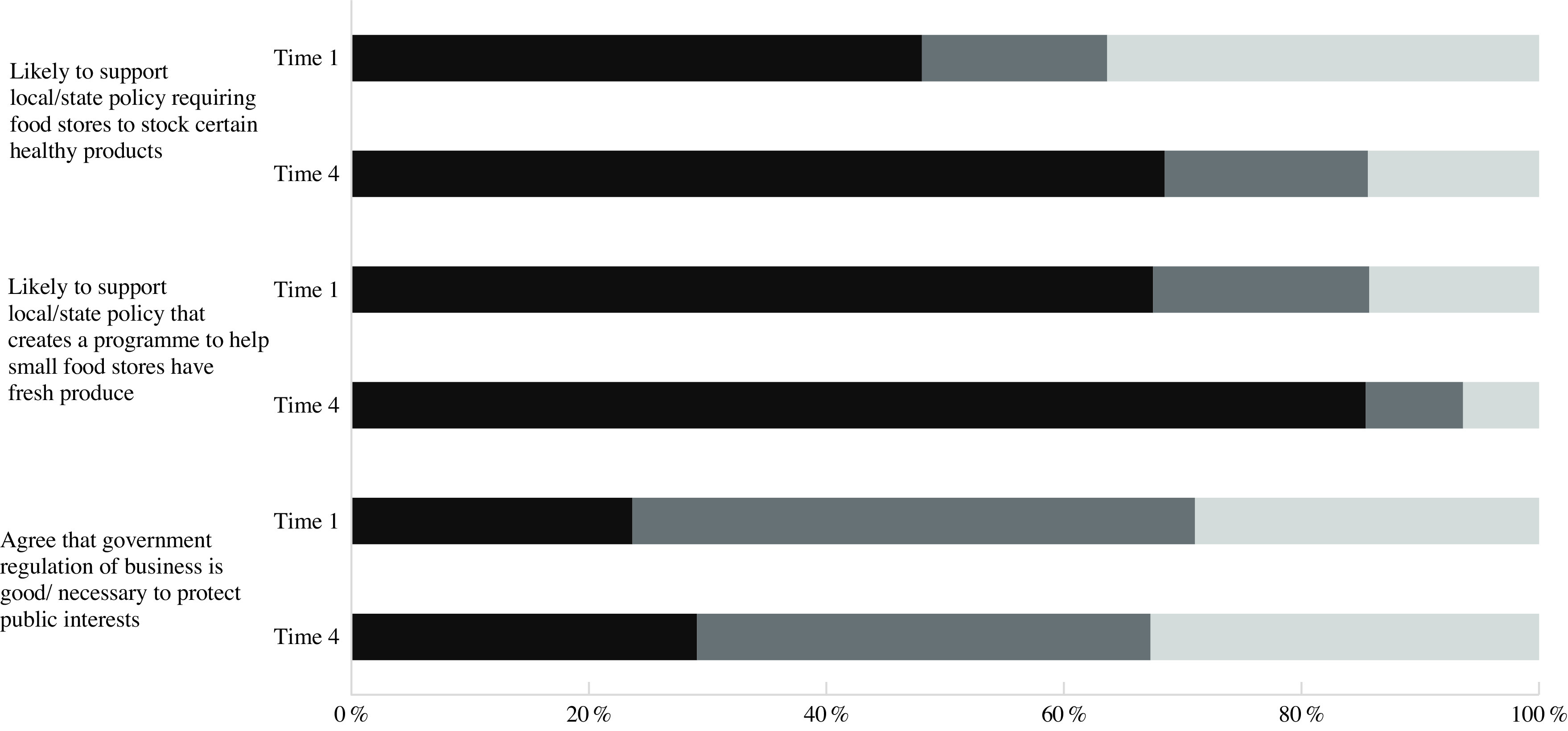

Descriptive characteristics of managers across the four time points are in online Supplementary Appendix B. For both support for a stocking policy and support for programmes that assist retailers, half of the managers supported these ideas pre-policy and both increased over time by approximately 20 percentage points (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Managers’ views on policy and regulation at time 1 (n 78) and time 4 (n 112) (unadjusted percentages).  , Support/agree;

, Support/agree;  , Neutral;

, Neutral;  , Unlikely/disagree

, Unlikely/disagree

Manager views on policy and regulation at time 1 (pre-policy) demonstrated few significant differences across manager and store and neighbourhood characteristics (online Supplementary Appendix C).

Changes in manager views over time

Table 1 presents changes in manager views on policy and government regulation across times 1–4 (2014–2017) in Minneapolis and St. Paul, adjusting for five manager characteristics (gender, US nativity, educational attainment, job title and age) that were shown to significantly differ between cities in bivariate comparisons (four time points collapsed) as covariates. There was a significant increase over time (P < 0·001) in support for policies requiring stores to stock healthy products, and though predicted means at times 1, 2 and 3 were higher in Minneapolis compared with St. Paul, differences by city were non-significant (P = 0·08). There was also no differential change in predicted means over time by city (P = 0·38), suggesting no impact of the Staple Food Ordinance on manager support for a stocking policy. Similarly, we identified a significant increase over time (P = 0·006) in likelihood to support a policy creating programmes to help stores offer fresh produce, but did not identify significant differences by city (P = 0·27) or over time by city (P = 0·24). Agreement that government regulation of business is good/needed did not demonstrate a significant overall effect over time, by city, or over time by city.

Table 1.

Impact of Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance over time (2014–2017) on adjusted means of manager views regarding policy and government regulation (n 412 observations across 147 stores)*

| Overall effects | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment period | Main effects | Interaction | ||||||||||

| Time 1, 2014 | Time 2, 2015 | Time 3, 2016 | Time 4, 2017 | Time | City | Time × City | ||||||

| Outcome | City | Mean | se | Mean | se | Mean | se | Mean | se | P (df = 3) | P (df = 1) | P (df = 3) |

| Likelihood to support stocking policy | ||||||||||||

| 1 = Very Unlikely | Minneapolis | 3·4 | 0·3 | 4·1 | 0·2 | 4·1 | 0·1 | 4·0 | 0·2 | <0·001 | 0·08 | 0·38 |

| 5 = Very Likely | St. Paul | 3·2 | 0·3 | 3·5 | 0·2 | 3·9 | 0·1 | 4·0 | 0·2 | |||

| P-net | – | 0·38 | 0·90 | 0·68 | ||||||||

| Likelihood to support programme to help stores have produce | ||||||||||||

| 1 = Very Unlikely | Minneapolis | 3·9 | 0·2 | 4·2 | 0·1 | 4·2 | 0·1 | 4·3 | 0·1 | 0·006 | 0·27 | 0·24 |

| 5 = Very Likely | St. Paul | 3·7 | 0·2 | 4·0 | 0·2 | 4·4 | 0·1 | 4·1 | 0·1 | |||

| P-net | – | 0·79 | 0·39 | 0·55 | ||||||||

| Government regulation of business is good/needed | ||||||||||||

| 1 = Strongly disagree | Minneapolis | 2·8 | 0·2 | 2·9 | 0·1 | 2·8 | 0·1 | 3·0 | 0·2 | 0·91 | 0·17 | 0·12 |

| 5 = Strongly agree | St. Paul | 2·8 | 0·2 | 2·8 | 0·1 | 2·8 | 0·1 | 2·5 | 0·1 | |||

| P-net | – | 0·47 | 0·90 | 0·06 | ||||||||

Linear regression model adjusted for repeated measures over time and for manager gender, US nativity, educational attainment, job title and age (covariates that were significantly associated with city in bivariate analyses); P-net values refer to changes in time × city effect from time 1 to time 2, time 1 to time 3, and time 1 to time 4, respectively.

Manager views of the Minneapolis staple food ordinance

Table 2 presents both the Challenges and Proposed Solutions offered by managers in response to the Minneapolis Ordinance. Several types of challenges were described with regard to ordinance compliance. Of these, food waste and financial burden were the two most prominent. Managers also offered ideas to improve the ordinance and stores’ ability to comply. Some proposed distribution-related solutions, like assistance in fostering partnerships with staple food suppliers, farmers’ markets and community gardens, whereas others suggested reduced requirements or policy exemptions.

Table 2.

Types of challenges and suggestions for future action described by managers about the Minneapolis staple foods ordinance at time 4 (n 51, 2017, Minneapolis, MN, USA retailers only)*

| Description | Data sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Challenges | ||

| Food waste (n 15, 29 %) | Expressed concern about food waste or spoiling of fresh and canned products | ‘The only problem is that no one’s buying. [The required items] are expiring.’ |

| Financial burden (n 12, 24 %) | Concerned the ordinance will cause financial hardship due to lack of affordability of staple foods from vendors or food waste | ‘[The ordinance is] not feasible, unreasonable to force us to carry these products. Creates a financial burden for the store that is not benefiting the community…’ |

| Stocking (n 10, 20 %) | Difficulties in maintaining stock due to shelving space, storage or coolers | ‘Sometimes it’s hard to maintain stock of staple items…hard to keep up storage.’ |

| Enforcement challenges (n 9, 18 %) | Disputes or concerns encountered with ordinance enforcement | ‘They come in and make sure we have food Minneapolis wants…. They came in and told us you need more orange juice and beans. We had sold the oranges. She was serious and we was like “what?!”’ |

| Policy overreaching (n 7, 14 %) | Expressed that the ordinance is not necessary or lack of need for staple food items among customers | ‘Overly targeted to certain types [of stores]-if you really want to help go across street to dollar store.’ |

| Competition (n 5, 10 %) | Concerns about competing stores which offer staple foods | Response to question asking if the policy will result in more staple foods being bought in small food stores: ‘No, not in my neighborhood. There is already a grocery store and famer’s market nearby.’ |

| Proposed solutions | ||

| Distribution (n 15, 29 %) | Solutions related to distribution, including partnerships, financial assistance and farmers markets | ‘Need to help smaller stores who have trouble obtaining the products. Give them source suppliers.’ |

| Exemptions/reducing requirements (n 10, 20 %) | Discussion of proposed exemptions due to specific circumstances or ways to improve the ordinance requirements to be more feasible for stores to comply | ‘If you are in a two-block radius of [large grocery retailer] or other store with fresh and cheap products, don’t need to comply.’ |

| Big Government (n 9, 18 %) | Ways to improve staple food item sales or ordinance with larger state or federal government intervention | ‘[The government] should go after the food companies, have them put more healthy things in the food. People wouldn’t have a choice then.’ |

| Education/create customer demand (n 8, 16 %) | Ways to improve promotion of staple foods by targeting customers and increasing knowledge within the community and among retailers | ‘City advertise to public that healthy food is at convenience stores. Educate public.’ |

| Increase enforcement (n 3, 6 %) | Suggestions related to increasing enforcement | ‘The city could do more inspections. They don’t show up as often as I feel they should.’ |

Challenges and proposed solutions are listed in order by the number of managers citing each. We also examined responses to identify whether managers did or did not think the ordinance would result in more customers buying staple food items at their stores. Out of fifty-one managers, 22 (43 %) provided a response that indicated they thought the ordinance would result in more customers buying staple food items at their stores, 22 (43 %) did not think this would occur, and 7 (14 %) were unsure.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine views about healthy food retail policy and government regulation among managers of small food retail stores. Overall, our findings suggest support for policies requiring stores to stock certain healthy foods significantly increased in recent years among managers in Minneapolis/St. Paul. We identified only a few differences in manager views about food retail policies by manager- and store-level characteristics. Despite managers increasing support for food retail policies, those who were directly affected by the 2014 Minneapolis Staple Food Ordinance still expressed several challenges.

We found manager support for policies requiring stores to stock healthy foods and beverages significantly increased over time and did not differ across cities. This suggests that managers of small food retail stores are increasingly amenable to policy and may be increasingly interested in offering healthier products to customers. However, these increases do not appear to be due to the 2014 Minneapolis Staple Food Ordinance, unless an effect in Minneapolis spilled over to St. Paul. These results are also consistent with literature on other policies, such as smoke-free laws, which suggest support for policy banning smoking increased after policy implementation(14–16). Overall, this support among managers is encouraging, as previous work indicates that having strong, or even moderate, owner support of a programme to increase stocking of healthy products can increase likelihood of success in changing and sustaining stocking practices(17).

Open-ended responses indicated managers were concerned with a range of challenges about maintaining stock and customer demand. This is consistent with other literature on food retailers, in which managers have expressed concern about stocking healthier food because of low consumer demand, spoilage and lack of profitability(18–22). While many managers indicated support for retail food policy overall, Minneapolis managers were divided on whether they believed the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance would increase sales of staple foods in their store, which may have been shaped by their perceived challenges.

Despite this study building upon a large body of literature on small food retail and expanding knowledge on managers’ perceptions of retail food policy, several limitations must be considered. Our study included managers from the same store over time; however, in this process, we often encountered different managers in any given store over time. Other limitations are that data were derived from stores in only one geographic area and in response to a single policy intervention. However, a major strength is that we used longitudinal data to explore explicit policy questions with managers of small food stores during a time of major changes in US federal administration and turmoil over government regulation and public health policy(23,24). In addition, while open-ended responses were brief and hand-recorded by surveyors, they helped illuminate the manager experiences and can help inform future efforts to improve the success of similar local food policies. Many factors, including store type, current manager stocking practices and perceived customer demand, may influence manager attitudes towards policy and should be examined in future studies to understand changes in increasing support over time.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest many managers support policies requiring stores to stock healthy foods, but challenges remain in implementing such policies. Although Minneapolis was the first and remains one of the only cities to adopt such a policy, understanding these challenges and managers’ perspectives has national implications, as the Staple Food Ordinance has received considerable attention and has been considered by other localities(25,26). Lessons learned through our evaluation of the Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance will be useful in developing and implementing future ordinances and other programmes which have the potential to improve both the nutritional quality of foods offered and purchased from small retail stores.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like acknowledge the valuable input and support provided by Ms. Kristen Klingler, Ms. Nora Gordon and their colleagues at the Minneapolis Health Department. In addition, we would like to thank Ms. Stacey Moe and Pamela Carr-Manthe for their leadership in data collection efforts, Mr. Bill Baker for his programming support and the many data collectors who were involved in this effort. Finally, we would like to thank the retailers who participated in this study and gave us permission to assess their stores and interview their customers. Financial support: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DK104348 (Principal Investigator: M.N.L.); and the Health Promotion and Disease. Prevention Research Center supported by Cooperative Agreement Number 5U48DP005022 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Principal Investigator: M.N.L.). Further support was provided to C.M.M. as a predoctoral fellow and M.R.W. as a postdoctoral fellow by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32DK083250 (Principal Investigator: R. Jeffery). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Funding agencies had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: C.M. M.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, analysing data and writing the manuscript. M.R.W.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, analysing data and writing the manuscript. K.M.L.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, analysing data and manuscript revision. L.H.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, designing the study and manuscript revision. D.J.E.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, designing the study and manuscript revision. M.N.L.: formulating the research question(s), formulating the analysis plan, analysing data, designing the study and manuscript revision. Ethics of human subject participation: This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki, and all procedures involving study participants were approved by The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Verbal consent was witnessed and formally recorded.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020000580.

click here to view supplementary material

References

- 1. Larson N, Story M & Nelson MC (2009) Neighborhood environments disparities in access to healthy foods in the US. Am J Prev Med 36, 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beaulac J, Kristjansson E & Cummins S (2009) A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. Prev Chronic Dis 6, A105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gravlee CC, Boston PQ, Mitchell MM et al. (2014) Food store owners’ and managers’ perspectives on the food environment: an exploratory mixed-methods study. BMC Public Health 14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gittelsohn J, Laska MN, Karpyn A et al. (2014) Lessons learned from small store programs to increase healthy food access. Am J Health Behav 38, 307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gittelsohn J, Rowan M & Gadhoke P (2012) Interventions in small food stores to change the food environment, improve diet, and reduce risk of chronic disease. Prev Chronic Dis 9. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bailey H, Elena LS, Vivica IK et al. (2019) A systematic review of factors that influence food store owner and manager decision making and ability or willingness to use choice architecture and marketing mix strategies to encourage healthy consumer purchases in the United States, 2005–2017. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Andreyeva T, Middleton AE, Long MW et al. (2011) Food retailer practices, attitudes and beliefs about the supply of healthy foods. Public Health Nutr 14, 1024–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ayala G, Laska M, Zenk S et al. (2012) Stocking characteristics and perceived increases in sales among small food store managers/owners associated with the introduction of new food products approved by the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Public Health Nutr 15, 1771–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pinard CA, Fricke HE, Smith TM et al. (2016) The future of the small rural grocery store: a qualitative exploration. Am J Health Behav 40, 749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mayer VL, Young CR, Cannuscio CC et al. (2016) Perspectives of urban corner store owners and managers on community health problems and solutions. Prev Chronic Dis 13, E144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laska MN, Caspi CE, Lenk K et al. (2019) Evaluation of the first U.S. staple foods ordinance: impact on nutritional quality of food store offerings, customer purchases and home food environments. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 16, 1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Foltz JL, Harris DM and Blanck HM et al. (2012) Adults for local and state policies to increase fruit and vegetable access. Am J Prev Med 43, S102–S108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pew Research Center (2014) Political typology quiz. http://www.people-press.org/quiz/political-typology/ (accessed May 2015).

- 14. Rayens MK, Hahn EJ, Langley RE et al. (2007) Public opinion and smoke-free laws. Policy Polit Nurs Pract 8, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pacheco J (2013) Attitudinal policy feedback and public opinion: the impact of smoking bans on attitudes towards smokers, secondhand smoke, and antismoking policies. Public Opin Q 77, 714. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagelhout GE, Wolfson T, Zhuang Y-L et al. (2015) Population support before and after the implementation of smoke-free laws in the United States: trends from 1992–2007. Nicotine Tob Res 17, 350–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Song H-J, Gittelsohn J, Kim M et al. (2011) Korean American storeowners’ perceived barriers and motivators for implementing a corner store-based program. Health Promot Pract 12, 472–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gittelsohn J, Franceschini MCT, Rasooly IR et al. (2008) Understanding the food environment in a low-income urban setting: implications for food store interventions. J Hunger Environ Nutr 2, 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Malley K, Gustat J, Rice J et al. (2013) Feasibility of increasing access to healthy foods in neighborhood corner stores. J Community Health 38, 741–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ross A, Krishnan N, Ruggiero C et al. (2018) A mixed methods assessment of the barriers and readiness for meeting the SNAP depth of stock requirements in Baltimore’s small food stores. Ecol Food Nutr 57, 94–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McDaniel PA, Minkler M, Juachon L et al. (2018) Merchant attitudes toward a healthy food retailer incentive program in a low-income San Francisco neighborhood. Int Q Community Health Educ 38, 207–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim M, Budd N, Batorsky B et al. (2016) Barriers to and facilitators of stocking healthy food options: viewpoints of Baltimore City small storeowners. Ecol Food Nutr 56, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Eilperin J & Dennis B (2019) Trump administration to revoke California’s power to set stricter auto emissions standards. The Washington Post.

- 24. Reddy S, Sprout G & Lehmann J (2020) The Trump administration’s continued attack on the nutrition safety net: at what cost? Health Affairs Blog. doi: 10.1377/hblog20200114.268036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Change lab Solutions (2013) Licensing for Lettuce: A Guide to the Model Licensing Ordinance for Healthy Food Retailers. https://www.changelabsolutions.org/product/licensing-lettuce (accessed August 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 26. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) (2019) Counting Carrots in Corner Stores: The Minneapolis Staple Foods Ordinance, A Law and Health Policy Project Bright Spot. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/law-and-health-policy/bright-spot/counting-carrots-in-corner-stores-the-minneapolis-staple (accessed August 2019). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980020000580.

click here to view supplementary material