Abstract

Oxytocin (OT) has broad effects in the brain and plays an important role in cognitive, social, and neuroendocrine function. OT has also been identified as potentially therapeutic in neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism and depression, which are often comorbid with epilepsy, raising the possibility that it might confer protection against the behavioral and seizure phenotypes in epilepsy. Dravet syndrome (DS) is an early-life encephalopathy associated with prolonged and recurrent early-life febrile seizures (FSs), treatment-resistant afebrile epilepsy, and cognitive and behavioral deficits. De novo loss-of-function mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel SCN1A are the main cause of DS, while genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+), also characterized by early-life FSs and afebrile epilepsy, is typically caused by inherited mutations that alter the biophysical properties of SCN1A. Despite the wide range of available antiepileptic drugs, many patients with SCN1A mutations do not achieve adequate seizure control or the amelioration of associated behavioral comorbidities. In the current study, we demonstrate that nanoparticle encapsulation of OT conferred robust and sustained protection against induced seizures and restored more normal social behavior in a mouse model of Scn1a-derived epilepsy. These results demonstrate the ability of a nanotechnology formulation to significantly enhance the efficacy of OT. This approach will provide a general strategy to enhance the therapeutic potential of additional neuropeptides in epilepsy and other neurological disorders.

Keywords: oxytocin, nanoparticles, seizure, Scn1a, behavior

Introduction

Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurrent and unprovoked seizures. The voltage-gated sodium channel SCN1A is one of the most important human epilepsy genes. Loss-of-function SCN1A mutations are the main cause of Dravet syndrome (DS)(L. Claes et al., 2001; Wallace et al., 2003) while mutations that alter the biophysical properties of SCN1A lead to genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+)(Escayg et al., 2001; Escayg et al., 2000; Wallace et al., 2001). DS is a devastating, treatment-resistant early-life encephalopathy associated with severe febrile and afebrile seizures, cognitive deficits and behavioral abnormalities(L. R. Claes et al., 2009; Escayg et al., 2010; Lossin, 2009). GEFS+ is characterized by febrile seizures (FSs) that persist beyond 6 years of age and the development of a variety of epilepsy subtypes. Current anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) often fail to provide adequate protection against the severe seizures and have little impact on the social behavior deficits often comorbid in patients with SCN1A mutations.

Mice with heterozygous deletion of Scn1a (Scn1a+/−) recapitulate many of the clinical features observed in DS patients, including spontaneous seizures, cognitive and behavioral abnormalities, and increased mortality(Han et al., 2012; Miller et al., 2014; Yu et al., 2006). We previously generated a mouse model of GEFS+ by knock-in of the human SCN1A GEFS+ mutation, R1648H(Martin et al., 2010). Heterozygous Scn1aR1648H/+ mutants (RH/+) exhibit spontaneous seizures, reduced seizure thresholds and behavioral deficits(Martin et al., 2010; Papale et al., 2013; Purcell et al., 2013). Homozygous mutants exhibit frequent spontaneous seizures and die between 3–4 weeks of age(Martin et al., 2010).

Oxytocin (OT) is a neuropeptide that can act both as a neurotransmitter and hormone within the brain(Buijs, 1983). OT has been shown to mediate several aspects of social behavior, including maternal care(Leng et al., 2008), pair bonding(Lim et al., 2006), and social recognition memory(Ferguson et al., 2000). In the well-established valproic acid (VPA) mouse model of autism, a single dose of intranasal OT (100–200 μg) significantly increased social interaction as evidenced by increased sniffing of an unfamiliar mouse in a reciprocal interaction task(Hara et al., 2017). Repeated intranasal OT exposure also improved social interaction in the VPA(Hara et al., 2017) and Cntnap2 mouse models of autism(Penagarikano et al., 2015). In addition, increasing endogenous OT levels has also been shown to improve social behavior. For example, stimulation of OT-producing neurons in the paraventricular nucleus using either a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist or DREADD technology, resulted in an increase of OT release and sociability in Cntnap2 mutants(Penagarikano et al., 2015). Of direct clinical relevance, intravenous OT infusion and intranasal OT(Guastella et al., 2010) has been shown to reduce repetitive behaviors and improve social behavior in patients diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder(Hollander et al., 2007; Hollander et al., 2003).

OT exhibits neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects(Chilumuri et al., 2013; Kaneko et al., 2016; Karelina et al., 2011), including protecting the hippocampus from excitotoxicity(Morales, 2011). OT has also been shown to modulate neuronal excitability(Y. T. Lin & Hsu, 2018). Furthermore, mice lacking oxytocin receptors (OXTRs; Oxtr−/−) are susceptible to pentylenetetrazole (PTZ)-induced seizures(Sala et al., 2011), suggesting that OT can influence seizure susceptibility. However, inconsistent findings have been reported on the effects of OT administration on seizure susceptibility(Erbas et al., 2013; Loyens et al., 2012), possibly due to the systemic delivery of OT in those studies. OT has a short half-life and cannot readily cross the blood brain barrier (BBB); therefore, systemic administration is likely associated with limited bioavailability. These factors also present a challenge to the clinical use of OT. In the current study, we demonstrate that nanoparticle encapsulation of oxytocin (NP-OT) greatly increases its ability to confer and sustain seizure protection and improve social behavior in a mouse model of Scn1a-derived epilepsy.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male CF1 mice (Strain: 023, Charles River, 2 months old) were used to determine the relationship between OT dose and susceptibility to 6 Hz-induced seizures, the contribution of OT and vasopressin receptors to OT-mediated seizure protection, and the effect of melanotan on 6 Hz seizures. CF1 mice were also used to determine whether acute NP-OT administration elicited neurotoxic effects on motor coordination and whether repeated NP-OT administration is associated with increased neuroinflammation. Heterozygous Scn1aR1648H/+ mutants (RH/+) were generated as previously described(Martin et al., 2010) and maintained by backcrossing to C57BL/6J (Strain: 000664, Jackson Laboratories). Male and female RH/+ mutants and WT littermates were used for seizure induction. Social behavior was assessed in male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates. All mice were housed on a 12-h light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines, the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Emory University as well as the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Pharmaceutical compounds

The nanoparticles were formulated and packaged with oxytocin (Bachem, H-2510) as previously described(Oppong-Damoah et al., 2019; Zaman et al., 2018). Nanoparticle encapsulated OT (NP-OT) was prepared as a suspension at a concentration of 50 μg OT/50 μL vehicle (10% tween 80 in 0.9% sterile saline). Free OT (10–50 μg, Bachem, H-2510) was dissolved in 10% tween 80 in 0.9% sterile saline. The selective oxytocin receptor antagonist L-371,257 (Tocris Bioscience, 2410) and the arginine vasopressin V1a receptor antagonist SR49059 (Tocris Bioscience, 2310) were dissolved in 10% DMSO and 0.9% sterile saline and administered at a concentration of 0.12 μg/20 μL (300 μg/kg). Melanotan II acetic salt (1–10 mg/kg, Toronto Research Chemicals, M208750) was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline. Pentylenetetrazole (25–115 mg/kg, Millipore-Sigma) was dissolved in 0.9% sterile saline.

Intracerebrovascular cannulation surgery

Male adult CF1 mice and RH/+ mutants underwent intracerebrovascular (ICV) cannulation surgery. Briefly, a 26-gauge guide cannula (Plastics One) was implanted to target the right lateral ventricle at the following coordinates relative to bregma: AP −0.3 mm and ML +1.0 mm. A custom cannula targeting the coordinate relative to bregma (DV) −3.0 mm was used for ICV injections. For generation of the dose-response curve, saline or OT (1–20 μg in a volume of 2 μL) was injected (ICV) over a 5-minute period. The cannula remained in place for 2 minutes to prevent backflow. Seizure induction was conducted 20 minutes after saline or OT administration.

Seizure induction

6 Hz

6 Hz seizures were induced as previously described(Barton et al., 2001; Inglis et al., 2019; Shapiro et al., 2019; J. C. Wong, Dutton, S.B.B., Collins, S.D., Schachter, S., Escayg, A., 2016; J. C. Wong et al., 2019) in male CF1 WT mice, RH/+ mutants and WT littermates. Briefly, a topical anesthetic of 0.5% proparacaine ophthalmic solution (Patterson Veterinary) was applied to the cornea. Each mouse was manually restrained and subjected to corneal stimulation (22–24 mA) using a constant current device (ECT Unit 57800, Ugo Basile, Comerio, Italy). Behavioral seizures were scored on a modified Racine scale (RS): RS0, no abnormal behavior; RS1, immobile ≥ 3 s; RS2, head bobbing, forelimb clonus; and RS3, rearing and falling, and loss of posture.

Pentylenetetrazole

Male CF1 WT mice and RH/+ mutants and WT littermates were administered PTZ (85–115 mg/kg) subcutaneously. The mice were observed for 30 minutes and the latencies to the first myoclonic jerk (MJ) and generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) were recorded. Susceptibility to PTZ-induced seizures was examined 20 minutes after ICV OT administration or 2 hours after NP-OT administration.

Hyperthermia

Two hours after NP-OT (100 μg OT) administration, P21–23 RH/+ mutants and WT littermates (N = 5–6/group) were subjected to hyperthermia as previously described(Dutton et al., 2017; J. C. Wong, Dutton, S.B.B., Collins, S.D., Schachter, S., Escayg, A., 2016; J. C. Wong et al., 2019). Briefly, the core body temperature of each mouse was maintained at 37.5°C for ten minutes, and was then increased by 0.5°C every two minutes until the first GTCS occurred or 42.5°C was reached. The temperature at which the mouse exhibited a GTCS was recorded.

Generation of dose-response curves

For ICV administration of OT or saline, male CF1 mice were implanted with a guide cannula targeting the right lateral ventricle. Two days after recovery, mice were administered OT (1–20 μg) or saline (2 μl) through the cannula (N = 6/group).

To generate a dose-response curve for intranasal administration of free OT, male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates were intranasally administered free OT (1–50 μg) or saline in a volume of 50 μl (N = 10/group). 6 Hz seizures were induced 20 minutes after ICV or intranasal administration of OT or saline.

Melanotan (MTII, 1–10 mg/kg) or saline was administered intraperitoneal (i.p.) to male CF1 mice. Mice were subjected to 6 Hz-induced seizures (22 mA) 20 minutes and 2 hours after MTII administration.

Evaluation of free OT

Based on the dose-response curve, 10 μg OT provided the most protection against 6 Hz seizures; therefore, this dose was further tested in RH/+ mutants and their WT littermates. Male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates were administered 10 μg OT or saline (2 μl) through the cannula (N = 5–10/group).

Comparison of free and encapsulated OT

Male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates (N = 8/group) were intranasally administered empty nanoparticles, free OT (10 μg), or NP-OT (100 μg OT). Each treatment was divided into two 50 μl intranasal administrations, 10 minutes apart. 6 Hz seizures were induced 20 minutes, 2 hours, and 6 hours after the last administration.

Administration of OT and vasopressin receptor antagonists

To evaluate whether NP-OT mediated seizure protection requires the oxytocin (OXTR) or vasopressin (AVPR1A) receptors, male CF1 mice were administered an OXTR antagonist (L-371,251) or an AVPR1A antagonist (SR49059) intranasally 45 minutes prior to NP-OT (100 μg) administration. 6 Hz seizures (22 mA) were induced 20 minutes and 2 hours after NP-OT administration.

Behavioral assessments

For all social behavioral assessments, male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates were used (3 months old, N = 12–14/treatment). Motor coordination was assessed in male CF1 WT mice (N = 10/treatment). Each mouse was administered (intranasally) empty nanoparticles or NP-OT (50 μg OT) at a concentration of 1 μg OT/μl vehicle two hours prior to behavioral testing.

Three-chamber social interaction

Sociability and social discrimination were tested using the three-chamber social interaction paradigm as previously described(Dutton et al., 2017). Each chamber of the apparatus (20 × 40 × 22 cm) was separated by a Plexiglas partition with a small opening (5 × 5 cm) to allow access between chambers. A wire cup was used as the inanimate object. Five pairs of age- and sex-matched stranger mice (Strain: 000664, C57BL/6J, Jackson laboratories) were acclimated to the wire cups within the three-chamber apparatus the day prior to testing of the experimental mice. Each pair of stranger mice was only used once each day. Experimental mice (RH/+ mutants or WT littermates, N = 12–14/group) were intranasally administered empty nanoparticles or NP-OT (50 μg OT) and then 2 hours later were tested in three consecutive 10-minute trials. In Trial 1, each experimental mouse was placed into the center chamber of the apparatus, with an empty wire cup in the left and right chambers, and allowed to freely explore. In Trial 2, a stranger mouse was placed under a wire cup in either the left or right chamber, and the experimental mouse was allowed to freely explore between the stranger mouse and inanimate object (wire cup). In Trial 3, a novel stranger mouse was placed into the previously empty wire cup; therefore, the experimental mouse could choose to explore the familiar (from Trial 2) or novel mouse. The time spent exploring the inanimate object or stranger mouse (Trial 2) and the time spent exploring the familiar or stranger mouse (Trial 3) were recorded. Exploration was defined by the time spent actively sniffing either the object or mouse.

Rotarod

The rotarod was used to evaluate motor coordination as a measure of neurotoxicity. Following intranasal administration of vehicle (50 μl), empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT (50 μg OT), each mouse (N = 10/group) was given two one-minute practice trials on a constant slow-moving rotarod (5 RPM, Columbus Instruments, Columbus OH, USA). This was followed by a 5-minute test trial on an accelerating rotarod (0.01 meters per second; 0–40 RPM), and the latency to fall was recorded. Each mouse had one minute of rest between each trial.

Repeated NP-OT administration and qRT-PCR

CF1 mice were intranasally administered vehicle, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT (100 μg OT) at a concentration of 1 μg OT/μl vehicle once each day for five consecutive days (N = 4–5 mice/group). Twenty-four hours after the last administration, the mice were perfused with 10X PBS. Total RNA was extracted from whole brain samples. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed as previously described(Lamar et al., 2017). PCR amplification of TNF-α, Iba1, LCN2, and GFAP were performed using the following primer pairs: TNF-α-F: TCTTCTGTCTACTGAACTTCGG, TNF-α-R: AAGATGATCTGAGTGTGAGGG; Iba1-F: GGATTTGCAGGGAGGAAAAG, Iba1-R: TGGGATCATCGAGGAATT; LCN2-F: ACCCTGTATGGAAGAACCAAGG, LCN2-R: CCACACTCACCACCCATTCA; GFAP-F: TGGAGGTGGAGAGGGACAAC, GFAP-R: CTTCATCTGCCTCCTGTCTATACG. Each primer pair produced standard curves with 90–100% efficiency. Real-time analysis was performed in technical triplicates using BioRad CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System and SYBR Green fluorescent dye (BioRad). Expression levels were normalized to actin.

Statistical analyses

A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare Racine scores following 6 Hz seizure induction between CF1 mice administered different doses of OT (ICV). A log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to compare the latency to the first GTCS following PTZ administration in RH/+ mutants and WT littermates. A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare Racine scores following 6 Hz-induced seizures in RH/+ mutants and WT littermates administered free OT, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT. A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare Racine scores following 6 Hz-induced seizures between CF1 mice administered the OXTR antagonist, AVPR1A antagonist, or melanotan. A two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare the time spent exploring the inanimate object versus stranger mouse and the time exploring the familiar versus stranger mouse in the three-chamber social interaction paradigm. A one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare the latency to fall from the rotarod in CF1 mice administered vehicle, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT. A Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to compare the fold change from vehicle (qRT-PCR) between empty nanoparticle and NP-OT treated CF1 mice. See Supplementary Table 1 for all statistical analyses.

Results

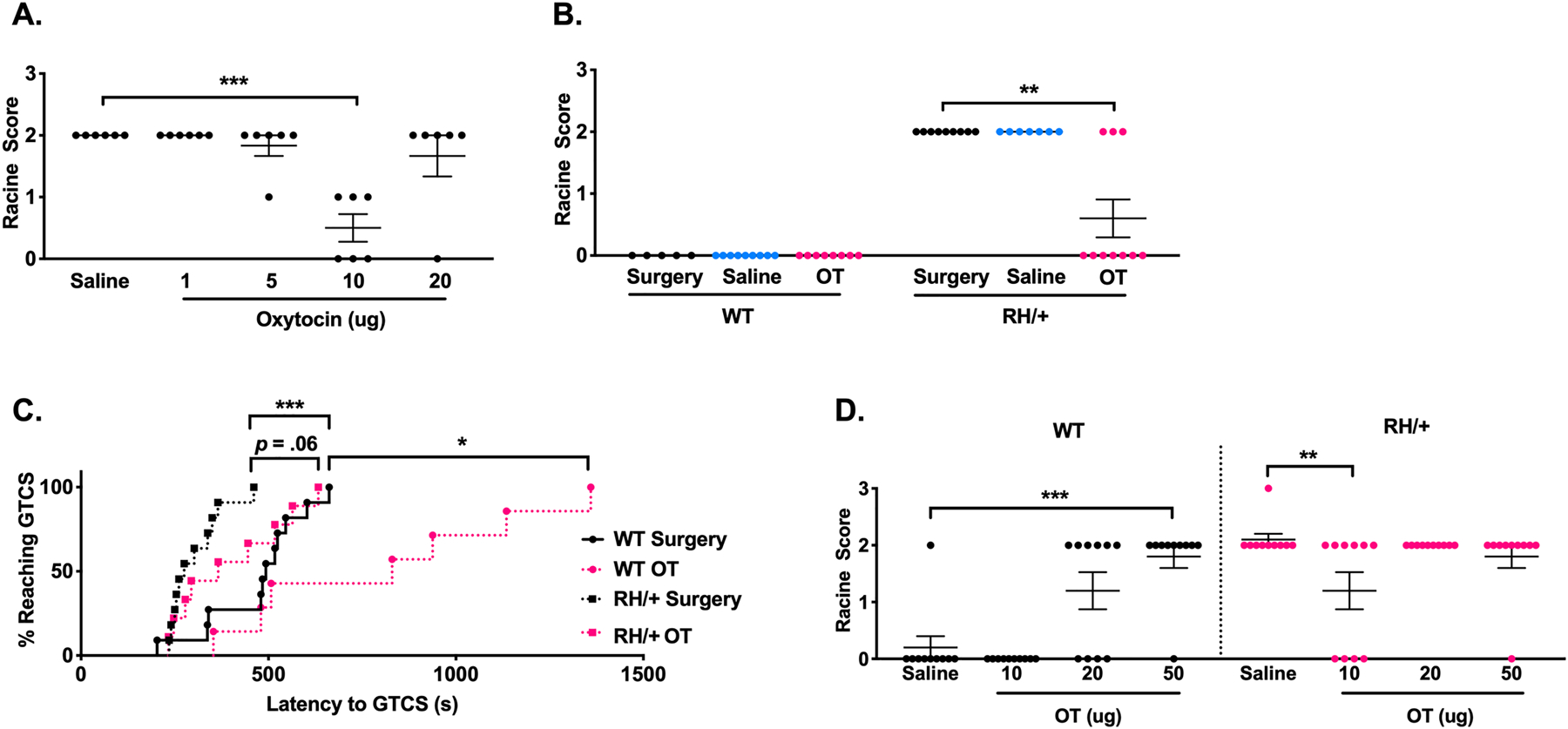

Intracerebral administration of oxytocin confers protection against induced seizures

To determine the effect of direct brain OT administration on seizure susceptibility, we first generated a dose-response curve. Susceptibility to seizures induced by the 6 Hz paradigm were determined 20 minutes after administration of a range of OT doses (0–20 μg) via intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection into the right lateral ventricle of male CF1 mice (Figure 1A). We observed RS2 seizures in 6/6 saline-treated mice; however, direct brain administration of OT (10 μg) prevented seizure generation in 3/6 mice, and milder RS1 seizures were seen in the remaining 3 mice (p < 0.001). We next examined whether ICV administration of OT could similarly increase seizure resistance in Scn1aR1648H/+ (RH/+) mutants and their WT littermates. All surgery control and saline-treated RH/+ mutants exhibited RS2 seizures, whereas 7/10 OT-treated RH/+ mutants were completely protected against 6 Hz-induced seizures (Figure 1B, p < 0.01). None of the WT littermates in the surgery control, saline, or OT-treated groups exhibited a seizure (Figure 1B). Following direct brain administration of OT, there was a trend towards an increased latency to the first PTZ-induced generalized tonic-clonic seizure (GTCS) in RH/+ mutants (Figure 1C, p = 0.06), while a significant increase in latency to the GTCS was observed in the WT littermates (Figure 1C, p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Direct brain administration of oxytocin increases resistance to induced seizures.

A) Generation of a dose-response curve with direct brain administration of OT using the 6 Hz seizure induction paradigm in CF1 mice. 10 μg OT significantly increased resistance to 6 Hz seizures. N = 6/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. B) Direct brain administration of OT (10 μg) increased resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures in Scn1aRH/+ mutants. N = 5–10/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. C) Direct brain administration of OT (10 μg) increased resistance to PTZ-induced seizures in Scn1aRH/+ mutants and WT littermates. N = 7–11/group, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. D) Generation of a dose-response curve in Scn1aRH/+ mutants and WT littermates with intranasal administration of free OT. 10 μg free oxytocin increased resistance to 6 Hz seizures in Scn1aRH/+ mutants while 50 μg OT elicited proconvulsant effects in WT littermates. N = 10/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Intranasal administration of oxytocin protects against 6 Hz-induced seizures

We next investigated whether intranasal administration of OT could also increase seizure resistance in RH/+ mutants and WT littermates. A dose-response curve was generated based on the ability of intranasally administered OT (0–50 μg) to alter response to 6 Hz-induced seizures in RH/+ mutants and WT littermates (Figure 1D). We found that intranasal administration of OT (10 μg) yielded a statistically significant increase in resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures in the RH/+ mutants (p < 0.01). However, we also observed a significant increase in seizure susceptibility in the WT littermates following the intranasal administration of 50 μg OT; seizure protection in RH/+ mutants was also lost at 20 and 50 μg OT (Figure 1D).

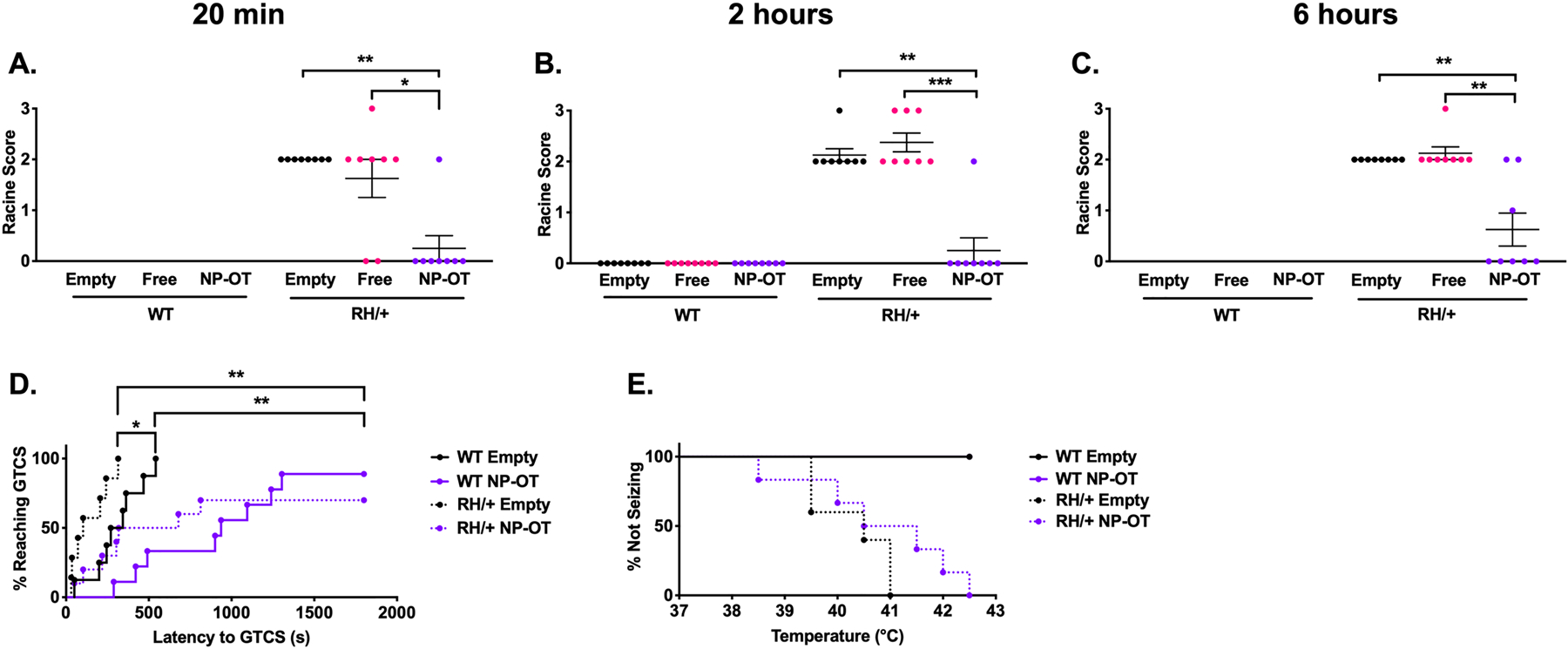

Nanoparticle encapsulated OT confers sustained and robust protection against induced seizures in RH/+ mutants

To determine whether nanoparticle encapsulation of OT could provide greater efficacy against induced seizures, we compared the effect of empty nanoparticles, free (unencapsulated) OT (10 μg OT), or nanoparticle encapsulated OT (NP-OT; 100 μg OT) on 6 Hz-induced seizures in male RH/+ mutants and their WT littermates (Figure 2A–C). None of the WT littermates exhibited a seizure. However, all empty nanoparticle-treated RH/+ mutants (8/8) had RS2 seizures, while 2/8 free OT-treated and 7/8 NP-OT treated RH/+ mutants were protected against 6 Hz-induced seizures at 20 minutes following administration (Figure 2A). When retested at 2 and 6 hours after OT administration, significant seizure protection was still observed in the NP-OT treated RH/+ mutants (7 RS0, 1 RS2 at 2 hours; 5 RS0, 1 RS1, 2 RS2 at 6 hours) while free OT- and empty nanoparticle-treated RH/+ mutants exhibited comparable seizure responses at these time points (Figure 2B–C). Sustained protection against 6 Hz-induced seizures was similarly observed following NP-OT (100 μg OT) administration to female RH/+ mutants and WT littermates (Figure S1).

Figure 2. Intranasal nanoparticle encapsulated oxytocin increases resistance to induced seizures.

A-C) Nanoparticle encapsulated oxytocin (NP-OT, 100 μg) protects against 6 Hz-induced seizures in Scn1aRH/+ mutants and maintains protection for up to 6 hours after administration. N =8/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. D) 1/9 and 3/10 WT and RH/+ mutants, respectively, did not exhibit a GTCS after NP-OT treatment. N = 9–10/group, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. E) NP-OT treatment did not protect against hyperthermia-induced seizures in Scn1aRH/+ mutants. N = 7–10/group, log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001.

The ability of intranasal NP-OT (100 μg OT) to protect against PTZ-induced seizures was also tested in male RH/+ mutants and WT littermates 2 hours after administration. The latency to the first GTCS was significantly increased in NP-OT treated mutants and WT littermates (Figure 2D, p < 0.01). Furthermore, 1/9 and 3/10 NP-OT-treated WT and RH/+ mutants, respectively, did not exhibit a PTZ-induced GTCS (Figure 2D, p < 0.01). NP-OT (100 μg OT) did not provide protection against hyperthermia-induced seizures when tested in RH/+ mutants, (Figure 2E).

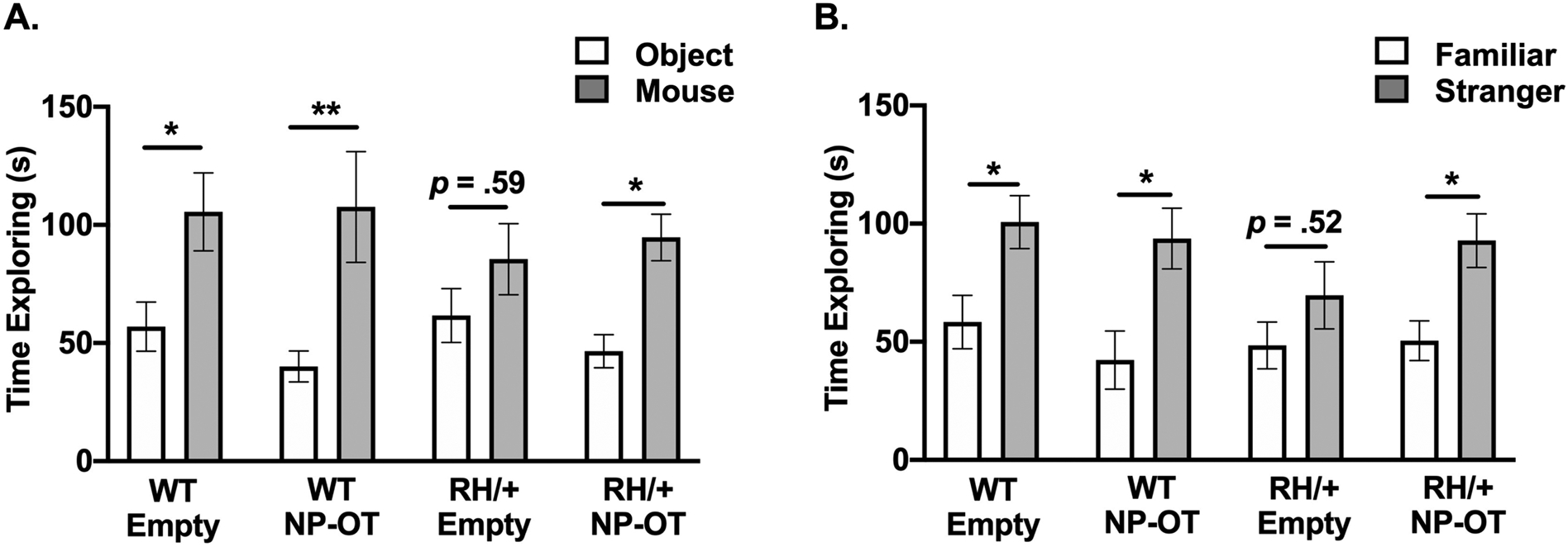

Nanoparticle encapsulated OT improves social behavior in RH/+ mutants

The effect of NP-OT on social behavior in RH/+ mutants was examined using the three-chamber social interaction paradigm(Dutton et al., 2017; Inglis et al., 2019). Empty nanoparticle- and NP-OT (50 μg OT) treated WT littermates exhibited normal sociability (Figure 3A) and social discrimination (Figure 3B). In contrast, empty nanoparticle-treated RH/+ mutants displayed no clear preference for the stranger mouse vs. an inanimate object, suggesting a deficit in sociability (Figure 3A, p = 0.59), and impaired social discrimination, as evidenced by no clear preference for the familiar vs. stranger mouse (Figure 3B, p = 0.52). However, RH/+ mutants administered NP-OT (50 μg OT) displayed more normal sociability (Figure 3A, p < 0.05) and social discrimination (Figure 3B, p < 0.05). These results demonstrate that NP-OT is also capable of improving social behavior in RH/+ mutants.

Figure 3. Intranasal nanoparticle encapsulated oxytocin improves social behavior in Scn1aRH/+ mutants.

A) Nanoparticle encapsulated oxytocin (NP-OT, 50 μg) administration increased the time spent exploring the stranger mouse vs. inanimate object in Scn1aRH/+ mutants. B) NP-OT improved the ability of Scn1aRH/+ mutants to discriminate between the stranger and familiar mouse. N = 12–14/group, two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

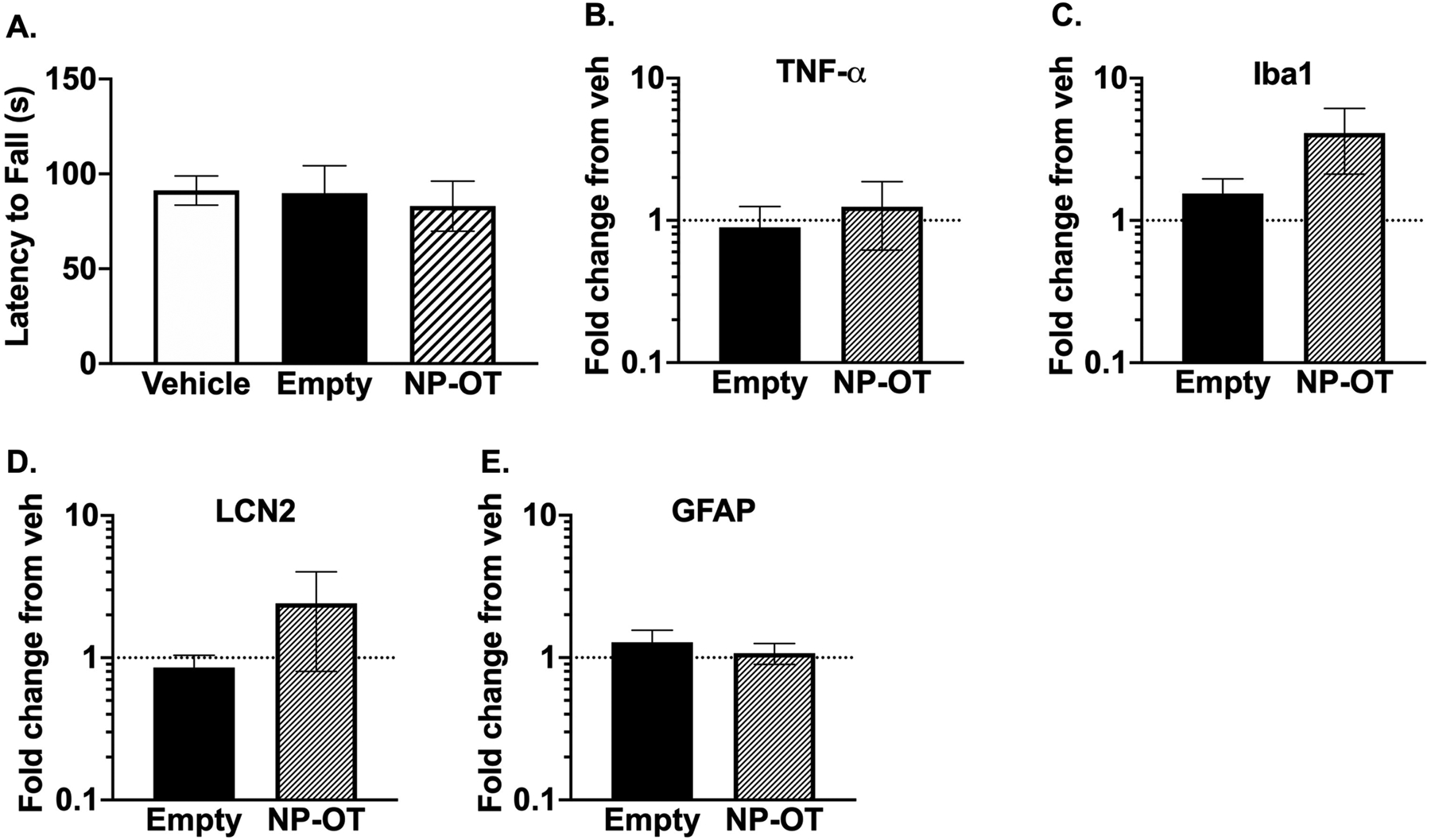

Acute administration of NP-OT does not produce neurotoxic effects

To determine whether acute NP-OT administration induces neurotoxic effects, we administered vehicle, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT (50 μg OT) to CF1 WT mice 2 hours prior to evaluating performance on a rotarod. We found no difference in the latency to fall from the accelerating rotarod across all treatment groups (Figure 4A), demonstrating that the empty nanoparticles and NP-OT do not cause neurotoxic motor effects.

Figure 4. Nanoparticles do not elicit neurotoxic effects.

A) Latency to fall off an accelerating rotarod was not significantly different between treatments. N = 10/group, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. B-E) Repeated administration of NP-OT for 5 days did not elicit an inflammatory response in WT mice administered vehicle, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT. Data normalized to vehicle-treated mice. N = 4–5/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons.

Repeated administration of NP-OT does not elicit an inflammatory response

To evaluate whether repeated nanoparticle (empty and NP-OT) administration could cause an inflammatory response, we administered vehicle, empty nanoparticles, or NP-OT (100 μg OT) to CF1 WT mice for 5 consecutive days, and the mice were sacrificed 24 hours after the last administration. qRT-PCR was performed to quantify mRNA levels of several inflammatory markers. We found no statistically significant differences in mRNA expression of TNF-α, Iba1, LCN2, and GFAP between any of the treatment groups (Figure 4B–E). Furthermore, the average weight of each mouse in each treatment group was comparable at the time of sacrifice (data not shown).

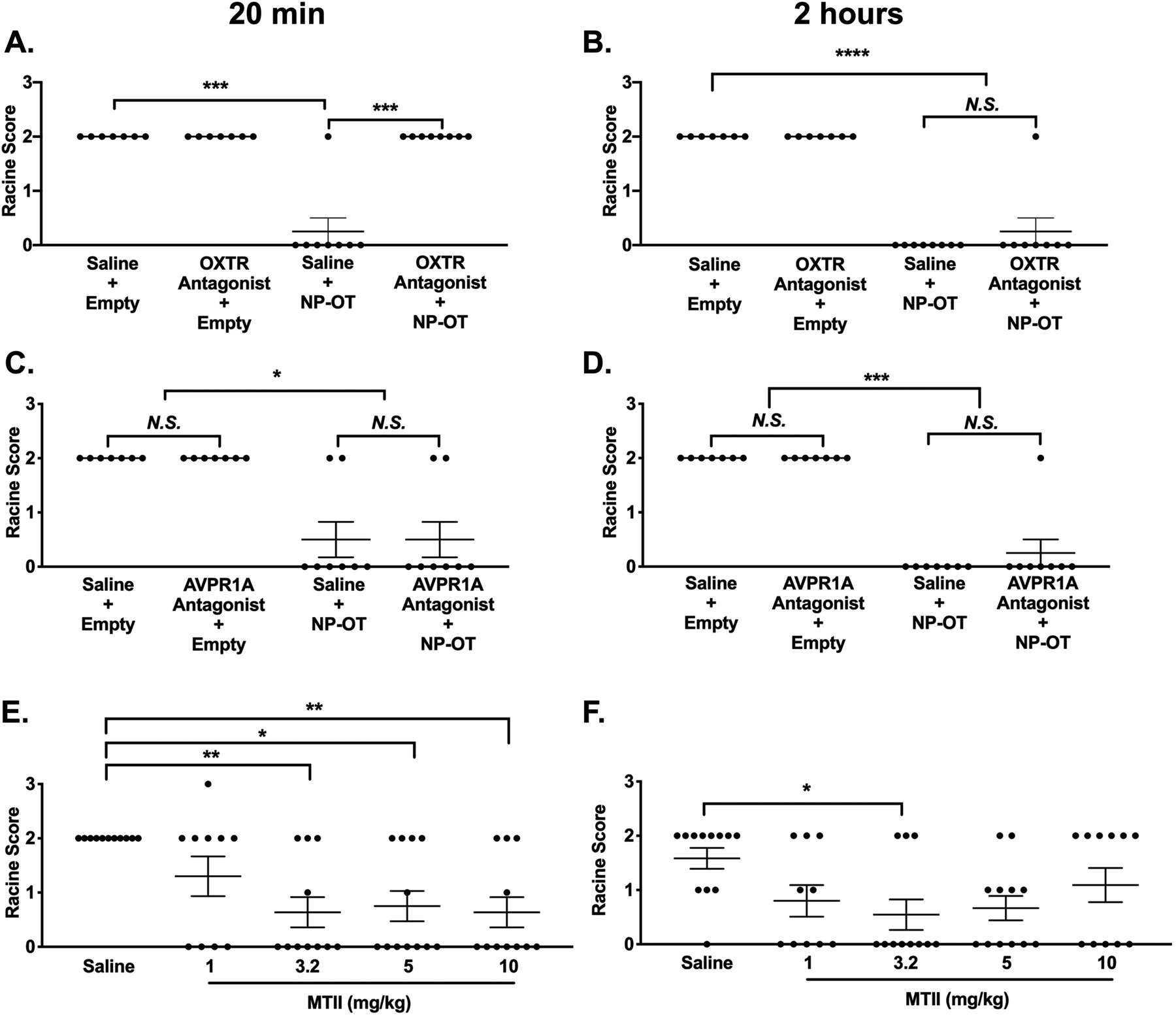

NP-OT mediated seizure protection is mediated by the oxytocin receptor

To evaluate the contribution of the oxytocin (OXTR) and the AVPR1A vasopressin receptors to NP-OT-mediated seizure protection, we pre-treated CF1 WT mice with either saline, an OXTR antagonist, or an AVPR1A antagonist 45 minutes prior to NP-OT (100 μg OT) administration. The mice were subjected to 6 Hz seizure induction at 20 minutes and 2 hours after NP-OT administration. As expected, saline + NP-OT treated CF1 mice were protected against 6 Hz-induced seizures at both time points (Figure 5A–D); however, administration of the OXTR antagonist blocked the NP-OT-mediated seizure protection at the 20-minute time point (Figure 5A), while seizure protection was observed at the 2-hour time point (Figure 5B). In contrast, administration of the AVPR1A antagonist + NP-OT did not prevent NP-OT from conferring seizure protection at either time point (Figure 5C–D). These results demonstrate that NP-OT conferred seizure protection is mediated by the OXTR.

Figure 5. The oxytocin receptor contributes to oxytocin-mediated seizure protection.

A) Administration of the OT receptor antagonist L-371,257 blocks NP-OT mediated seizure protection at 20 minutes but not B) two hours after NP-OT administration. N = 7–8/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. C-D) Administration of the AVPR1A antagonist SR49059 does not block NP-OT mediated seizure protection. N = 7–8/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. E) Generation of a dose-response curve for melanocortin 4 receptor agonist melanotan II (MTII). MTII (3.2–10 mg/kg) increased resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures at 20 minutes after administration in CF1 mice. F) MTII (3.2 mg/kg) increased resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures at 2 hours minutes after administration in CF1 mice. E-F) N = 10–12/group, Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Higher endogenous OT levels also provide seizure protection

To determine whether increasing endogenous OT levels could also provide seizure protection, we administered melanotan (MTII), a melanocortin receptor agonist that has previously been shown to increase endogenous OT levels(Modi et al., 2015). We found that MTII (3.2, 5, and 10 mg/kg) was able to significantly increase resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures in CF1 mice at 20 minutes following administration (Figure 5E). A statistically significant increase in seizure protection was only observed with 3.2 mg/kg MTII at 2 hours after administration (Figure 5F). These results demonstrate that higher levels of endogenous OT can also increase resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures.

Discussion

Previous studies have been inconsistent on the ability of OT to increase seizure resistance. For example, Erbas et al. found that OT administration inhibited PTZ-induced seizures(Erbas et al., 2013), while Loyens et al. observed an increase in susceptibility to PTZ-induced seizures following OT administration(Loyens et al., 2012). The conflicting observations from these studies might have been due to the short half-life of OT and its poor ability to cross the blood-brain barrier when administered via systemic intraperitoneal injection. However, intrahippocampal OT administration in rats(Erfanparast et al., 2017) and ICV OT delivery in the current study (Figure 1), were both associated with increased resistance to induced seizures, demonstrating that OT can confer seizure protection if improved brain penetrance could be achieved.

Previous studies have shown that approximately 0.005% of intranasally administered OT reaches the CSF within 1 hour of administration(Leng et al., 2016); therefore, bolus or repeated intranasal OT administration would not significantly increase OT levels in the CSF. To overcome these limitations, we developed a bovine serum albumin nanoparticle formulation conjugated with rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) to encapsulate OT(Oppong-Damoah et al., 2019; Zaman et al., 2018). Intranasal administration of our NP-OT formulation was previously shown to significantly increase the concentration of OT in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) when compared with intranasally administered free OT in WT mice(Oppong-Damoah et al., 2019). NP-OT administration also resulted in a greater ratio of OT in CSF versus plasma, thereby reducing potential peripheral side effects of OT(Oppong-Damoah et al., 2019). Furthermore, NP-OT was shown to increase social interaction in WT mice at 2 hours and 3 days after administration, demonstrating sustained OT-mediated effects(Oppong-Damoah et al., 2019). In the current study, we demonstrate that NP-OT significantly increases and sustains resistance to induced seizures, and improves social behavior in a mouse model of Scn1a-derived epilepsy.

Oxytocin and vasopressin (AVP) share considerable homology, differing only at the 3rd and 8th amino acid(Stoop, 2012), thus, it is not surprising that OT has been shown to act upon the oxytocin receptor OXTR and the arginine vasopressin receptor AVPR1a. AVP can bind to each of the three AVP receptors and OXTR with similar affinity while OT preferentially binds the OXTR with 100-fold greater affinity than AVP receptors(Manning et al., 2012; Mouillac et al., 1995; Stoop, 2012). However, there is evidence that OT can exert effects by activation of the AVPR1a (Schorscher-Petcu et al., 2010; Song et al., 2014). Our findings shed light on potential mechanisms of OT-mediated seizure protection, indicating that the OXTR, and not the AVPR1A, is critical for the observed seizure protection. OXTR block prevented NP-OT-mediated seizure protection at the early time point (20 minutes after administration) but not at the 2-hour time point (Figure 5A–B). This observation is likely explained by the short half-life of the OXTR antagonist L-371,257; thus, it is unable to effectively block OXTR activity at the later time point (165 minutes from intranasal L-371,257 administration)(Williams et al., 1995). Unlike the OXTR antagonist, the AVPR1A antagonist (SR49059) has a significantly longer duration of action(Serradeil-Le Gal et al., 1993); and would be expected to still exert its effect at the 2-hour time point (Figure 5C–D). It has been hypothesized that the rapid increase in OT levels during or immediately following a seizure is a neuroprotective adaptive mechanism aimed at regulating the hypothalamus during a stress response(Piekut et al., 1996). For example, activation of OT-but not vasopressin-expressing magnocellular neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), as reflected by c-Fos staining, has been observed following kainic acid (KA)-induced status epilepticus (SE)(Piekut et al., 1996). Although OT and vasopressin are closely related neuropeptides, they likely play different roles in epilepsy.

The melanocortin 4 receptor agonist, melanotan (MTII) has previously been shown to elicit a wide range of behavioral effects, including increased sexual behavior(Giuliano et al., 2006; Rossler et al., 2006), improved social behavior(Barrett et al., 2014; Minakova et al., 2019; Modi et al., 2015), peripheral nerve regeneration(Ter Laak et al., 2003), and increased insulin sensitivity(Heijboer et al., 2005). The most pronounced melanotan-mediated effects appear to be on social and sexual behaviors which have been shown to be associated with an increase in endogenous OT release(Modi et al., 2015). Consistent with the response to NP-OT administration, we demonstrated that administration of MTII, as a method to increase endogenous OT, significantly increased resistance to 6 Hz-induced seizures (Figure 5E and F). While we cannot exclude the possibility of a non-OT related mechanism by which melanotan increases seizure resistance, a survey of the literature showed that the major effects of melanotan are associated with an increase in endogenous OT release. Therefore, we believe that the observed increase in seizure resistance following MTII administration is likely due to increased endogenous OT.

OXTRs are expressed in the CA1(Muhlethaler et al., 1984), CA2(Y. T. Lin, Hsieh, et al., 2018; Mitre et al., 2016; Tirko et al., 2018), and CA3(Hammock et al., 2013; Y. T. Lin et al., 2017; Y. T. Lin, Hsieh, et al., 2018; Y. T. Lin & Hsu, 2018) and the dentate gyrus (DG)(Harden et al., 2016) regions of the hippocampus and have been shown to play an important role in regulating neuronal excitability in the hippocampus(Y. T. Lin & Hsu, 2018). For example, exogenous application of OT to rat hippocampal slices was shown to inhibit CA1 pyramidal neurons as a result of increased firing of GABAergic interneurons(Muhlethaler et al., 1984; Zaninetti et al., 2000). To date, only a few studies have examined the effect of OT on subclasses of GABAergic interneurons. Owen et al. demonstrated that OT activates feed-forward fast-spiking parvalbumin (PV) interneurons which 1) suppresses CA1 pyramidal cell firing and 2) enhances information transfer from the PV interneurons to pyramidal cells(Owen et al., 2013). Harden and Frazier showed that in the DG, OT activates fast-spiking hilar interneurons which, in turn, releases GABA onto hilar mossy cells(Harden et al., 2016). Given that oscillatory rhythms in the hippocampus are largely controlled by GABAergic interneurons(Y. T. Lin & Hsu, 2018), it is possible that OT could activate GABAergic interneurons to suppress abnormal hippocampal rhythms that are often observed in epilepsy. OT has also been shown to increase firing of CA3 pyramidal neurons and promote neurogenesis in the DG(Y. T. Lin et al., 2017). Although the CA2 region of the hippocampus has been less studied, there is evidence to suggest that activation of OXTRs in the CA2 region plays a role in social recognition memory(Y. T. Lin, Hsieh, et al., 2018; Tirko et al., 2018). For example, Tirko et al. demonstrated that OT promotes repetitive firing of CA2 pyramidal neurons, which subsequently enhances the efficacy of information transfer to CA1 neurons, thus improving social recognition memory(Tirko et al., 2018). Together, these observations suggest that OT could be therapeutic in epilepsy by modulating neuronal excitability and ameliorating behavioral comorbidities.

In addition to OT, other neuropeptides, including galanin and neuropeptide Y (NPY), have demonstrated anti-epileptic(Foti et al., 2007; Haberman et al., 2003; Klemp et al., 2001; Kokaia et al., 2001; E. J. Lin et al., 2003; A. Mazarati et al., 2002; A. M. Mazarati et al., 1992; Stroud et al., 2005; Vezzani et al., 2004) and behavior modulating effects(Broqua et al., 1995; dos Santos et al., 2013; Heilig et al., 1993; Heilig et al., 1989; Heilig et al., 1988; Kask et al., 1998) when directly administered or overexpressed in the brain; however, limited bioavailability of neuropeptides remains a critical barrier to their clinical application. Factors contributing to this include; 1) the size of the peptide which limits the ability to cross the BBB, 2) the hydrophilic/hydrophobic nature of the peptide, and 3) enzymes and proteases that actively degrade peptides, resulting in short half-lives. The recent development of nanoparticles, which are composed of polymer matrices, such as poly(lactide-co-glycolides (PLGA) or natural polymers like chitosan and bovine serum albumin, which range in size from 50–200 nm(Kaur, 2018), allow for optimal intranasal delivery. Advantages of nanoparticle encapsulation include improved BBB penetrance, protection of encapsulated contents from degradation, and sustained drug release.

Nanoparticle technology has also been used to improve brain delivery of established anti-epileptic drugs. Valproic acid, a commonly prescribed AED, was packaged into a nanostructured lipid carrier and demonstrated significantly greater brain-to-plasma concentration compared to systemic injection of valproic acid(Eskandari et al., 2011). Carbamazepine (CBZ)-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles significantly increased plasma and brain CBZ levels compared to non-encapsulated CBZ(Liu, 2018). Gabapentin-loaded albumin nanoparticles significantly increased resistance to maximal electroshock seizures and PTZ-induced seizures(Wilson et al., 2014). Administration of oxcarbazepine-loaded PLGA nanoparticles reduced seizure severity after PTZ administration(Musumeci et al., 2018). As demonstrated in these studies, nanoparticle technology can significantly enhance the therapeutic potential of established drugs, and as shown in the current study, can also provide improved brain delivery and sustained release of neuropeptides.

We have established that nanoparticle encapsulated oxytocin confers robust and sustained protection against induced seizures and improves social behavior in RH/+ mutants, a mouse model of Scn1a-derived epilepsy. This strategy can be readily applied to other neuropeptides, thus creating new opportunities for clinical application in the treatment of epilepsy and other neurological disorders.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Oxytocin is a promising therapeutic treatment for Scn1a-derived epilepsy and possibly other forms of epilepsy.

Nanoparticle encapsulation of oxytocin (NP-OT) significantly increases and maintains resistance to induced seizures in Scn1a mutant mice.

Social behavior was restored to more normal behavior following NP-OT treatment in Scn1a mutants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Cheryl Strauss for her editorial assistance.

Funding and disclosure

This study was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R21NS114795 JCW; AE and KSM, R21NS100512; KSM, DA046215) and the American Epilepsy Society (LS). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no financial interests relating to the work described and declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barrett CE, Modi ME, Zhang BC, Walum H, Inoue K, & Young LJ (2014). Neonatal melanocortin receptor agonist treatment reduces play fighting and promotes adult attachment in prairie voles in a sex-dependent manner. Neuropharmacology, 85, 357–366. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.05.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton ME, Klein BD, Wolf HH, & White HS (2001). Pharmacological characterization of the 6 Hz psychomotor seizure model of partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res, 47(3), 217–227. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11738929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broqua P, Wettstein JG, Rocher MN, Gauthier-Martin B, & Junien JL (1995). Behavioral effects of neuropeptide Y receptor agonists in the elevated plus-maze and fear-potentiated startle procedures. Behav Pharmacol, 6(3), 215–222. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11224329 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs RM (1983). Vasopressin and oxytocin--their role in neurotransmission. Pharmacol Ther, 22(1), 127–141. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(83)90056-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilumuri A, & Milton NG (2013). The Role of Neurotransmitters in Protection against Amyloid- beta Toxicity by KiSS-1 Overexpression in SH-SY5Y Neurons. ISRN Neurosci, 2013, 253210. doi: 10.1155/2013/253210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Del-Favero J, Ceulemans B, Lagae L, Van Broeckhoven C, & De Jonghe P (2001). De novo mutations in the sodium-channel gene SCN1A cause severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Am J Hum Genet, 68(6), 1327–1332. doi: 10.1086/320609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes LR, Deprez L, Suls A, Baets J, Smets K, Van Dyck T, … De Jonghe P (2009). The SCN1A variant database: a novel research and diagnostic tool. Hum Mutat, 30(10), E904–920. doi: 10.1002/humu.21083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos VV, Santos DB, Lach G, Rodrigues AL, Farina M, De Lima TC, & Prediger RD (2013). Neuropeptide Y (NPY) prevents depressive-like behavior, spatial memory deficits and oxidative stress following amyloid-beta (Abeta(1–40)) administration in mice. Behav Brain Res, 244, 107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.01.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton SBB, Dutt K, Papale LA, Helmers S, Goldin AL, & Escayg A (2017). Early-life febrile seizures worsen adult phenotypes in Scn1a mutants. Exp Neurol, 293, 159–171. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2017.03.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erbas O, Yilmaz M, Korkmaz HA, Bora S, Evren V, & Peker G (2013). Oxytocin inhibits pentylentetrazol-induced seizures in the rat. Peptides, 40, 141–144. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erfanparast A, Tamaddonfard E, & Henareh-Chareh F (2017). Intra-hippocampal microinjection of oxytocin produced antiepileptic effect on the pentylenetetrazol-induced epilepsy in rats. Pharmacol Rep, 69(4), 757–763. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escayg A, & Goldin AL (2010). Sodium channel SCN1A and epilepsy: mutations and mechanisms. Epilepsia, 51(9), 1650–1658. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02640.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escayg A, Heils A, MacDonald BT, Haug K, Sander T, & Meisler MH (2001). A novel SCN1A mutation associated with generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus--and prevalence of variants in patients with epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet, 68(4), 866–873. doi: 10.1086/319524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escayg A, MacDonald BT, Meisler MH, Baulac S, Huberfeld G, An-Gourfinkel I, … Malafosse A (2000). Mutations of SCN1A, encoding a neuronal sodium channel, in two families with GEFS+2. Nat Genet, 24(4), 343–345. doi: 10.1038/74159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari S, Varshosaz J, Minaiyan M, & Tabbakhian M (2011). Brain delivery of valproic acid via intranasal administration of nanostructured lipid carriers: in vivo pharmacodynamic studies using rat electroshock model. Int J Nanomedicine, 6, 363–371. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S15881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson JN, Young LJ, Hearn EF, Matzuk MM, Insel TR, & Winslow JT (2000). Social amnesia in mice lacking the oxytocin gene. Nat Genet, 25(3), 284–288. doi: 10.1038/77040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foti S, Haberman RP, Samulski RJ, & McCown TJ (2007). Adeno-associated virus-mediated expression and constitutive secretion of NPY or NPY13–36 suppresses seizure activity in vivo. Gene Ther, 14(21), 1534–1536. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3303013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuliano F, Clement P, Droupy S, Alexandre L, & Bernabe J (2006). Melanotan-II: Investigation of the inducer and facilitator effects on penile erection in anaesthetized rat. Neuroscience, 138(1), 293–301. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guastella AJ, Einfeld SL, Gray KM, Rinehart NJ, Tonge BJ, Lambert TJ, & Hickie IB (2010). Intranasal oxytocin improves emotion recognition for youth with autism spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry, 67(7), 692–694. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberman RP, Samulski RJ, & McCown TJ (2003). Attenuation of seizures and neuronal death by adeno-associated virus vector galanin expression and secretion. Nat Med, 9(8), 1076–1080. doi: 10.1038/nm901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammock EA, & Levitt P (2013). Oxytocin receptor ligand binding in embryonic tissue and postnatal brain development of the C57BL/6J mouse. Front Behav Neurosci, 7, 195. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2013.00195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han S, Tai C, Westenbroek RE, Yu FH, Cheah CS, Potter GB, … Catterall WA (2012). Autistic-like behaviour in Scn1a+/− mice and rescue by enhanced GABA-mediated neurotransmission. Nature, 489(7416), 385–390. doi: 10.1038/nature11356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara Y, Ago Y, Higuchi M, Hasebe S, Nakazawa T, Hashimoto H, … Takuma K (2017). Oxytocin attenuates deficits in social interaction but not recognition memory in a prenatal valproic acid-induced mouse model of autism. Horm Behav, 96, 130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2017.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden SW, & Frazier CJ (2016). Oxytocin depolarizes fast-spiking hilar interneurons and induces GABA release onto mossy cells of the rat dentate gyrus. Hippocampus, 26(9), 1124–1139. doi: 10.1002/hipo.22595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heijboer AC, van den Hoek AM, Pijl H, Voshol PJ, Havekes LM, Romijn JA, & Corssmit EP (2005). Intracerebroventricular administration of melanotan II increases insulin sensitivity of glucose disposal in mice. Diabetologia, 48(8), 1621–1626. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-1838-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, McLeod S, Brot M, Heinrichs SC, Menzaghi F, Koob GF, & Britton KT (1993). Anxiolytic-like action of neuropeptide Y: mediation by Y1 receptors in amygdala, and dissociation from food intake effects. Neuropsychopharmacology, 8(4), 357–363. doi: 10.1038/npp.1993.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Soderpalm B, Engel JA, & Widerlov E (1989). Centrally administered neuropeptide Y (NPY) produces anxiolytic-like effects in animal anxiety models. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 98(4), 524–529. doi: 10.1007/bf00441953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Wahlestedt C, & Widerlov E (1988). Neuropeptide Y (NPY)-induced suppression of activity in the rat: evidence for NPY receptor heterogeneity and for interaction with alpha-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol, 157(2–3), 205–213. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(88)90384-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Bartz J, Chaplin W, Phillips A, Sumner J, Soorya L, … Wasserman S (2007). Oxytocin increases retention of social cognition in autism. Biol Psychiatry, 61(4), 498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Novotny S, Hanratty M, Yaffe R, DeCaria CM, Aronowitz BR, & Mosovich S (2003). Oxytocin infusion reduces repetitive behaviors in adults with autistic and Asperger’s disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28(1), 193–198. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis GAS, Wong JC, Butler KM, Thelin JT, Mistretta OC, Wu X, … Escayg A (2019). Mutations in the Scn8a DIIS4 voltage sensor reveal new distinctions among hypomorphic and null Nav 1.6 sodium channels. Genes Brain Behav, e12612. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y, Pappas C, Tajiri N, & Borlongan CV (2016). Oxytocin modulates GABAAR subunits to confer neuroprotection in stroke in vitro. Sci Rep, 6, 35659. doi: 10.1038/srep35659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karelina K, Stuller KA, Jarrett B, Zhang N, Wells J, Norman GJ, & DeVries AC (2011). Oxytocin mediates social neuroprotection after cerebral ischemia. Stroke, 42(12), 3606–3611. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.628008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kask A, Rago L, & Harro J (1998). Anxiolytic-like effect of neuropeptide Y (NPY) and NPY13–36 microinjected into vicinity of locus coeruleus in rats. Brain Res, 788(1–2), 345–348. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00076-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Manhas P, Swami A, Bhandari R, Sharma KK, Jain R, Kumar R, Pandey SK, Kuhad A, Sharma RK, and Wangoo N (2018). Bioengineered PLGA-chitosan nanoparticles for brain targeted intranasal delivery of antiepileptic TRH analogues. Chemical Engineering Journal(346), 630–639. [Google Scholar]

- Klemp K, & Woldbye DP (2001). Repeated inhibitory effects of NPY on hippocampal CA3 seizures and wet dog shakes. Peptides, 22(3), 523–527. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11287110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokaia M, Holmberg K, Nanobashvili A, Xu ZQ, Kokaia Z, Lendahl U, … Hokfelt T (2001). Suppressed kindling epileptogenesis in mice with ectopic overexpression of galanin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 98(24), 14006–14011. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231496298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamar T, Vanoye CG, Calhoun J, Wong JC, Dutton SBB, Jorge BS, … Kearney JA (2017). SCN3A deficiency associated with increased seizure susceptibility. Neurobiol Dis, 102, 38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng G, & Ludwig M (2016). Intranasal Oxytocin: Myths and Delusions. Biol Psychiatry, 79(3), 243–250. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng G, Meddle SL, & Douglas AJ (2008). Oxytocin and the maternal brain. Curr Opin Pharmacol, 8(6), 731–734. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim MM, & Young LJ (2006). Neuropeptidergic regulation of affiliative behavior and social bonding in animals. Horm Behav, 50(4), 506–517. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EJ, Richichi C, Young D, Baer K, Vezzani A, & During MJ (2003). Recombinant AAV-mediated expression of galanin in rat hippocampus suppresses seizure development. Eur J Neurosci, 18(7), 2087–2092. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02926.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YT, Chen CC, Huang CC, Nishimori K, & Hsu KS (2017). Oxytocin stimulates hippocampal neurogenesis via oxytocin receptor expressed in CA3 pyramidal neurons. Nat Commun, 8(1), 537. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00675-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YT, Hsieh TY, Tsai TC, Chen CC, Huang CC, & Hsu KS (2018). Conditional Deletion of Hippocampal CA2/CA3a Oxytocin Receptors Impairs the Persistence of Long-Term Social Recognition Memory in Mice. J Neurosci, 38(5), 1218–1231. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1896-17.2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YT, & Hsu KS (2018). Oxytocin receptor signaling in the hippocampus: Role in regulating neuronal excitability, network oscillatory activity, synaptic plasticity and social memory. Prog Neurobiol, 171, 1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yang S, and Ho PC (2018). Intranasal administration of carbamazepine-loaded carboxymethyl chitosan nanoparticles for drug delivery to the brain. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences(13), 72–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lossin C (2009). A catalog of SCN1A variants. Brain Dev, 31(2), 114–130. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2008.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loyens E, Vermoesen K, Schallier A, Michotte Y, & Smolders I (2012). Proconvulsive effects of oxytocin in the generalized pentylenetetrazol mouse model are mediated by vasopressin 1a receptors. Brain Res, 1436, 43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning M, Misicka A, Olma A, Bankowski K, Stoev S, Chini B, … Guillon G (2012). Oxytocin and vasopressin agonists and antagonists as research tools and potential therapeutics. J Neuroendocrinol, 24(4), 609–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2012.02303.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin MS, Dutt K, Papale LA, Dube CM, Dutton SB, de Haan G, … Escayg A (2010). Altered function of the SCN1A voltage-gated sodium channel leads to gamma-aminobutyric acid-ergic (GABAergic) interneuron abnormalities. J Biol Chem, 285(13), 9823–9834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.078568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati A, & Wasterlain CG (2002). Anticonvulsant effects of four neuropeptides in the rat hippocampus during self-sustaining status epilepticus. Neurosci Lett, 331(2), 123–127. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00847-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazarati AM, Halaszi E, & Telegdy G (1992). Anticonvulsive effects of galanin administered into the central nervous system upon the picrotoxin-kindled seizure syndrome in rats. Brain Res, 589(1), 164–166. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)91179-i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller AR, Hawkins NA, McCollom CE, & Kearney JA (2014). Mapping genetic modifiers of survival in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Genes Brain Behav, 13(2), 163–172. doi: 10.1111/gbb.12099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minakova E, Lang J, Medel-Matus JS, Gould GG, Reynolds A, Shin D, … Sankar R (2019). Melanotan-II reverses autistic features in a maternal immune activation mouse model of autism. PLoS One, 14(1), e0210389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitre M, Marlin BJ, Schiavo JK, Morina E, Norden SE, Hackett TA, … Froemke RC (2016). A Distributed Network for Social Cognition Enriched for Oxytocin Receptors. J Neurosci, 36(8), 2517–2535. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2409-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modi ME, Inoue K, Barrett CE, Kittelberger KA, Smith DG, Landgraf R, & Young LJ (2015). Melanocortin Receptor Agonists Facilitate Oxytocin-Dependent Partner Preference Formation in the Prairie Vole. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(8), 1856–1865. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales T (2011). Recent findings on neuroprotection against excitotoxicity in the hippocampus of female rats. J Neuroendocrinol, 23(11), 994–1001. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillac B, Chini B, Balestre MN, Jard S, Barberis C, Manning M, … et al. (1995). Identification of agonist binding sites of vasopressin and oxytocin receptors. Adv Exp Med Biol, 395, 301–310. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8713980 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhlethaler M, Charpak S, & Dreifuss JJ (1984). Contrasting effects of neurohypophysial peptides on pyramidal and non-pyramidal neurones in the rat hippocampus. Brain Res, 308(1), 97–107. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90921-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci T, Serapide MF, Pellitteri R, Dalpiaz A, Ferraro L, Dal Magro R, … Puglisi G (2018). Oxcarbazepine free or loaded PLGA nanoparticles as effective intranasal approach to control epileptic seizures in rodents. Eur J Pharm Biopharm, 133, 309–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppong-Damoah A, Zaman RU, D’Souza MJ, & Murnane KS (2019). Nanoparticle encapsulation increases the brain penetrance and duration of action of intranasal oxytocin. Horm Behav, 108, 20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2018.12.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen SF, Tuncdemir SN, Bader PL, Tirko NN, Fishell G, & Tsien RW (2013). Oxytocin enhances hippocampal spike transmission by modulating fast-spiking interneurons. Nature, 500(7463), 458–462. doi: 10.1038/nature12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papale LA, Makinson CD, Christopher Ehlen J, Tufik S, Decker MJ, Paul KN, & Escayg A (2013). Altered sleep regulation in a mouse model of SCN1A-derived genetic epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+). Epilepsia, 54(4), 625–634. doi: 10.1111/epi.12060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penagarikano O, Lazaro MT, Lu XH, Gordon A, Dong H, Lam HA, … Geschwind DH (2015). Exogenous and evoked oxytocin restores social behavior in the Cntnap2 mouse model of autism. Sci Transl Med, 7(271), 271ra278. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3010257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piekut DT, Pretel S, & Applegate CD (1996). Activation of oxytocin-containing neurons of the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) following generalized seizures. Synapse, 23(4), 312–320. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell RH, Papale LA, Makinson CD, Sawyer NT, Schroeder JP, Escayg A, & Weinshenker D (2013). Effects of an epilepsy-causing mutation in the SCN1A sodium channel gene on cocaine-induced seizure susceptibility in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl). doi: 10.1007/s00213-013-3034-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossler AS, Pfaus JG, Kia HK, Bernabe J, Alexandre L, & Giuliano F (2006). The melanocortin agonist, melanotan II, enhances proceptive sexual behaviors in the female rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav, 85(3), 514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala M, Braida D, Lentini D, Busnelli M, Bulgheroni E, Capurro V, … Chini B (2011). Pharmacologic rescue of impaired cognitive flexibility, social deficits, increased aggression, and seizure susceptibility in oxytocin receptor null mice: a neurobehavioral model of autism. Biol Psychiatry, 69(9), 875–882. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schorscher-Petcu A, Sotocinal S, Ciura S, Dupre A, Ritchie J, Sorge RE, … Mogil JS (2010). Oxytocin-induced analgesia and scratching are mediated by the vasopressin-1A receptor in the mouse. J Neurosci, 30(24), 8274–8284. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1594-10.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serradeil-Le Gal C, Wagnon J, Garcia C, Lacour C, Guiraudou P, Christophe B, … et al. (1993). Biochemical and pharmacological properties of SR 49059, a new, potent, nonpeptide antagonist of rat and human vasopressin V1a receptors. J Clin Invest, 92(1), 224–231. doi: 10.1172/JCI116554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro L, Wong JC, & Escayg A (2019). Reduced cannabinoid 2 receptor activity increases susceptibility to induced seizures in mice. Epilepsia, 60(12), 2359–2369. doi: 10.1111/epi.16388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z, McCann KE, McNeill J. K. t., Larkin TE 2nd, Huhman KL, & Albers HE (2014). Oxytocin induces social communication by activating arginine-vasopressin V1a receptors and not oxytocin receptors. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 50, 14–19. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoop R (2012). Neuromodulation by oxytocin and vasopressin. Neuron, 76(1), 142–159. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud LM, O’Brien TJ, Jupp B, Wallengren C, & Morris MJ (2005). Neuropeptide Y suppresses absence seizures in a genetic rat model. Brain Res, 1033(2), 151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ter Laak MP, Brakkee JH, Adan RA, Hamers FP, & Gispen WH (2003). The potent melanocortin receptor agonist melanotan-II promotes peripheral nerve regeneration and has neuroprotective properties in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol, 462(1–3), 179–183. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02945-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirko NN, Eyring KW, Carcea I, Mitre M, Chao MV, Froemke RC, & Tsien RW (2018). Oxytocin Transforms Firing Mode of CA2 Hippocampal Neurons. Neuron, 100(3), 593–608 e593. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, & Sperk G (2004). Overexpression of NPY and Y2 receptors in epileptic brain tissue: an endogenous neuroprotective mechanism in temporal lobe epilepsy? Neuropeptides, 38(4), 245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RH, Hodgson BL, Grinton BE, Gardiner RM, Robinson R, Rodriguez-Casero V, … Scheffer IE (2003). Sodium channel alpha1-subunit mutations in severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy and infantile spasms. Neurology, 61(6), 765–769. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14504318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace RH, Scheffer IE, Barnett S, Richards M, Dibbens L, Desai RR, … Berkovic SF (2001). Neuronal sodium-channel alpha1-subunit mutations in generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus. Am J Hum Genet, 68(4), 859–865. doi: 10.1086/319516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PD, Clineschmidt BV, Erb JM, Freidinger RM, Guidotti MT, Lis EV, … et al. (1995). 1-(1-[4-[(N-acetyl-4-piperidinyl)oxy]-2-methoxybenzoyl]piperidin-4- yl)-4H-3,1-benzoxazin-2(1H)-one (L-371,257): a new, orally bioavailable, non-peptide oxytocin antagonist. J Med Chem, 38(23), 4634–4636. doi: 10.1021/jm00023a002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B, Lavanya Y, Priyadarshini SR, Ramasamy M, & Jenita JL (2014). Albumin nanoparticles for the delivery of gabapentin: preparation, characterization and pharmacodynamic studies. Int J Pharm, 473(1–2), 73–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2014.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JC, Dutton SBB, Collins SD, Schachter S, Escayg A (2016). Huperzine A provides robust and sustained protection against induced seizures in Scn1a mutant mice. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 7(357). doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JC, Thelin JT, & Escayg A (2019). Donepezil increases resistance to induced seizures in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Ann Clin Transl Neurol, 6(8), 1566–1571. doi: 10.1002/acn3.50848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu FH, Mantegazza M, Westenbroek RE, Robbins CA, Kalume F, Burton KA, … Catterall WA (2006). Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci, 9(9), 1142–1149. doi: 10.1038/nn1754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman RU, Mulla NS, Braz Gomes K, D’Souza C, Murnane KS, & D’Souza MJ (2018). Nanoparticle formulations that allow for sustained delivery and brain targeting of the neuropeptide oxytocin. Int J Pharm, 548(1), 698–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.07.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaninetti M, & Raggenbass M (2000). Oxytocin receptor agonists enhance inhibitory synaptic transmission in the rat hippocampus by activating interneurons in stratum pyramidale. Eur J Neurosci, 12(11), 3975–3984. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.