Abstract

Research on undersampled magnetic resonance image (MRI) reconstruction can increase the speed of MRI imaging and reduce patient suffering. In this paper, an undersampled MRI reconstruction method based on Generative Adversarial Networks with the Self-Attention mechanism and the Relative Average discriminator (SARA-GAN) is proposed. In our SARA-GAN, the relative average discriminator theory is applied to make full use of the prior knowledge, in which half of the input data of the discriminator is true and half is fake. At the same time, a self-attention mechanism is incorporated into the high-layer of the generator to build long-range dependence of the image, which can overcome the problem of limited convolution kernel size. Besides, spectral normalization is employed to stabilize the training process. Compared with three widely used GAN-based MRI reconstruction methods, i.e., DAGAN, DAWGAN, and DAWGAN-GP, the proposed method can obtain a higher peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure(SSIM), and the details of the reconstructed image are more abundant and more realistic for further clinical scrutinization and diagnostic tasks.

Keywords: MRI, reconstruction, deep learning, compressive sensing, neuroinformatics, artificial intelligence, GAN

Introduction

MRI can carry out the non-invasive examination of the internal tissues of the human body, so it is widely used in clinical pathological examination and diagnosis (Liang and Lauterbur, 2000; Kabasawa, 2012). However, the excessive scanning time of MRI limits its clinical application, and this problem is particularly prominent for high-resolution imaging. Therefore, how to reduce k-space sampling (Duyn et al., 1998) and shorten MRI acquisition time has become a research focus in this field. Compressed sensing (CS) (Lustig et al., 2008, 2010) is a conventional method for solving this problem, it uses the compressibility and sparsity of the signal to reduce k-space sampling and achieve fast imaging. At present, the methods surrounding compressed sensing for fast MRI mainly include non-Cartesian CS (Haldar et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2012), combination parallel imaging with CS (Murphy et al., 2012; El Gueddari et al., 2019; Shimron et al., 2020), and CS-based on dictionary learning (Ravishankar and Bresler, 2010; Huang et al., 2014; Du et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2020). Although the above-mentioned methods based on compressed sensing have achieved good results, they all rely on the prior knowledge extracted from the image, which limits the use of the above methods to a certain extent.

In recent years, deep learning (LeCun et al., 2015) methods have been successfully applied in many fields. In particular, with the emergence of convolutional neural networks, made it show great performance in computer vision. At present, many MRI reconstruction methods based on deep learning have been proposed (Boyd et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016; Aggarwal et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018; Akçakaya et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020). In 2016, Wang et al. (2016) first applied deep learning methods to the acceleration of MRI imaging. They employed an offline CNN to realize the mapping of undersampled zero-filled MRI and fully sampled k-space data and achieved good reconstruction effectively. Deep learning based MRI reconstruction methods can be roughly divided into unrolling-based approaches and those not based on unrolling (Liang et al., 2020). Among them, the unrolling-based method usually expands the CS-based iterative reconstruction algorithm into a deep network, so that the parameters in the reconstruction algorithm can be learned by the network. Sun et al. (2016) proposed the ADMM-Net defined over data flow graphs, which were derived from the iterative procedures in the Alternating Direction Method of Multipliers (ADMM) algorithm (Boyd et al., 2011) for optimizing a general CS-based MRI mode, and it significantly improved the baseline ADMM algorithm and achieved high reconstruction accuracies with fast computational speed. The framework proposed by Aggarwal et al. (2018), termed as MOdel-based reconstruction using Deep Learned priors (MODL), merged the power of model-based reconstruction schemes with deep learning. Their model provided improved results, despite the relatively smaller number of trainable parameters. The methods not unrolling-based mainly uses deep networks to learn the mapping between under-sampled data and fully sampled data to achieve reconstruction. Zhu et al. (2018) proposed a unified framework—automated transform by manifold approximation (AUTOMAP), it constructed a supervised learning task to learn the mapping between sensor domain and image domain from training data. Besides, Robust artificial-neural-networks for k-space interpolation (RAKI) (Akçakaya et al., 2019) was proposed for image reconstruction by training convolutional neural networks on ACS data. Compared with the traditional linear k-space interpolation-based method, this method had better anti-noise performance.

The Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) (Goodfellow et al., 2014) proposed by Goodfellow was a novel deep generative model, which introduced the idea of game theory and improved the fitting ability of the network through the competitive learning of generator and discriminator. In 2016, Radford et al. proposed Deep Convolutional Generative Adversarial Networks (DCGAN) to apply convolutional neural networks to unsupervised learning (Radford et al., 2016). By applying convolutional neural networks to generators and discriminators, the network could learn a hierarchy of representations from object parts to scenes. At present, GAN and its variants have achieved excellent performance in image-to-image translation (Zhu et al., 2017), image super-resolution (Ledig et al., 2017), and others. In recent years, since its good data representation capabilities, GAN have also been used for MRI fast imaging (Arjovsky et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2017; Jiang et al., 2019; Kwon et al., 2019) and super-resolution (Chen et al., 2018; Lyu et al., 2019; Mahapatra et al., 2019). Yang et al. (2017) applied conditional GAN to MRI reconstruction and proposed the De-Aliasing Generative Adversarial Networks (DAGAN) model. Compared with conventional methods, the DAGAN model achieved a better reconstruction effect and retained more perceptible details. Wasserstein GAN (Arjovsky et al., 2017) is a variant of the original GAN, by replacing the Jensen-Shannon divergence in the original GAN with Wasserstein distance, it stabilizes the learning process and solves the problem of mode collapse. Jiang et al. (2019) proposed a de-aliasing fine-tuning Wasserstein generative adversarial network (DA-FWGAN) for MR imaging reconstruction. The DA-FWGAN could provide reconstruction with improved peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure (SSIM).

Although the current MRI reconstruction methods based on deep learning can better learn the mapping relationship between undersampling MRI and full sampling MRI, the reconstruction effect still has a lot of room for improvement. Firstly, most GANs use convolutional layers to build their generators. Due to the limited size of the convolution kernel, the network can only focus on the dependencies of the information in the local receptive field (Luo et al., 2016), but it cannot establish the long-range dependencies of the image, which leads to the inaccurate reconstruction of the image details and texture. Self-Attention Generative Adversarial Networks (SA-GAN) (Zhang et al., 2019) proposed by Zhang et al. solved this problem by introducing a self-attention mechanism and constructing long-range dependency modeling. The self-attention mechanism was used for establishing the long-range dependence relationship between the image regions. To enhance the image details and improve the quality of reconstructed MRI, the local dependence, and the global dependence of the image were combined. Secondly, the discriminator did not make full use of the prior knowledge that half of the input data is true and half is fake (Jolicoeur-Martineau, 2018). When the generated data is real enough, the discriminator can directly distinguish the generated data into real data, which results in the insufficient performance of the discriminator and the training of the generator cannot be continued. Alexia Jolicoeur-Martineau used the prior knowledge to induce a “relative discriminator” (Jolicoeur-Martineau, 2018), which estimated the probability that the given real data was more realistic than a randomly sampled fake date.

In this paper, we propose a novel MRI reconstruction method, termed as SARA-GAN, which combines the self-attention mechanism and the relative discriminator. The generator is designed as a structure, composing of down-sampling block, residual block, and up-sampling block. Among them, in the up-sampling block, we add a self-attention layer to capture the global information of the image. Besides, the discriminator uses the CNN structure and introduces the idea of relative discrimination to construct a relative average discriminator. At the same time, we also apply spectral normalization on the generator and discriminator to stabilize the training process. The novelties of our proposed SARA-GAN model have been summarized as follows

Given the traditional convolutional structure that can only focus on the local dependency of the image, we add a self-attention layer to the high-layer of the generator network. The self-attention mechanism can calculate the correlation degree between image pixels and build long-range dependencies so that the reconstructed image can demonstrate more details.

The theoretical formula of the original GAN-based methods ignores the prior information of the discriminator's input data. In our SARA-GAN model, we use relative average discriminator to transform the absolute true or false discrimination into relative true or false. In doing so, our SARA-GAN model can make full use of the prior information, and therefore can improve the discriminator performance.

In our SARA-GAN, the generator adopts a residual network structure, in which multiple residual blocks are cascaded and multiple skip connections are incorporated to reduce the loss of original features in the convolution calculation. At the same time, this can avoid poor performance of the generator in the initial training stage; therefore, the training procedure can be more efficient.

We also apply the spectral normalization to the network parameters of the generator and the discriminator to satisfy the Lipschitz constraint, thereby stabilizing the training of our GAN-based SARA-GAN model.

Methods

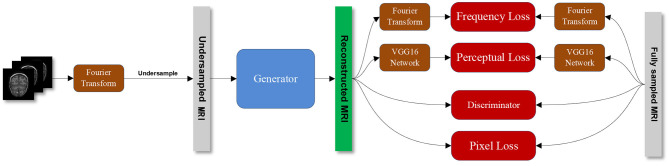

Figure 1 shows the overall structure of our proposed SARA-GAN. We obtain the k-space data of the fully sampled MRI through Fourier transform, then undersampled the k-space data, and perform inverse Fourier transform to obtain the image-domain undersampled MRI. The generator is used to learn the mapping relationship between undersampled MRI and full-sampled MRI. The discriminator is a binary classifier, used to judge whether the reconstructed image is true or false. The combined loss function incorporates the pixel loss, the perceptual loss, and the frequency-domain loss based on the adversarial loss. The pixel loss and the perceptual loss can constrain GAN training on the image content. The frequency-domain loss provides additional constraints for the data consistency in the k-space. The pre-trained VGG16 network is used to extract features from the fully sampled MRI and the reconstructed MRI respectively, and the two sets of features are compared to obtain the perception loss. The discriminator and the combined loss function guide the training of the generator together.

Figure 1.

The overall structure of the proposed SARA-GAN method.

Network Structure

Generator Model

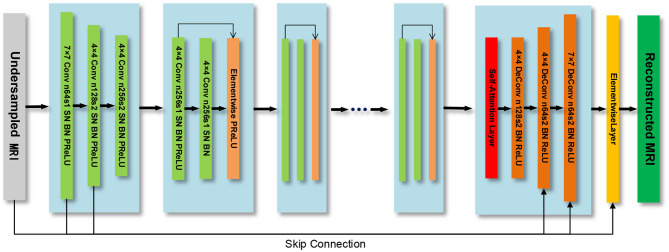

The generator model is composed of a down-sampling block, residual block, and up-sampling block. The three convolutional layers in the down-sampling block are used to extract image features. The residual block contains 7 residual blocks, and each residual block contains two convolutional layers. The up-sampling block consists of three transposed convolutional layers, which are used to expand the feature map and generate reconstructed MRI. We use spectral normalization on the generator network and choose the PReLU (He et al., 2015) function as the activation function. Besides, we introduce the self-attention module in the up-sampling block to build the long-range dependency of the image, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The generator model.

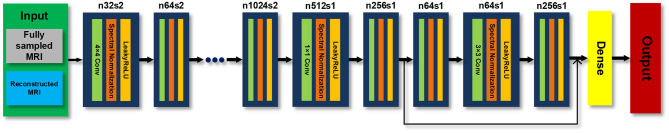

Discriminator Model

The discriminator model is an 11-layer CNN network, which uses leaky ReLU as the activation function. The last layer is the dense layer, and the sigmoid function is used as the activation function to output the discriminatory results of the discriminator, as shown in Figure 3. We also use spectral normalization in the discriminator.

Figure 3.

Discriminator model.

Self-Attention Module

To overcome the problem that the network cannot learn long-range global dependencies caused by the limited size of the convolution kernel, we add the self-attention (Zhang et al., 2019) into the up-sampling block of the generator, as shown in Figure 2. In the self-attention module, the output feature map of the last residual block x with the channel number C of the previous convolution layer is input to three convolution layers with a kernel of 1 × 1 and the channel numbers of C/8, C/8 and C respectively, to obtain the feature space f(x),g(x) and h(x)

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Then the transpose of f(xi) is multiplied by g(xj), and the weight is normalized by the Softmax function to obtain βj,i

| (4) |

| (5) |

where βj,i is an attention map that indicates the extent to which the model attends to the ith location when synthesizing the jth region. The output of the self-attention layer is defined as

| (6) |

In the above formula, Wf, Wg,Wh, and Wv are the weight matrices of the 1 × 1 convolutional layer. To allow the generator learns the local dependence of the image as well as the long-range global dependence, we multiply the output of the self-attention layer oj by a weight coefficient γ and add it to the input feature map xi to obtain the final output of the self-attention module yi

| (7) |

Among them, γ is a learnable parameter and is initialized to 0. Its function is to enable the network to learn the proportion of the global dependency on the feature map.

Relative Average Discriminator

In the original GAN model, the generator accepts random noise, and then generates a false image and inputs it to the discriminator. The discriminator gives the probability that the input image belongs to the real image. The two compete with each other and learn together. Finally, the generator learns the probability distribution of the real image, making the discriminator unable to distinguish between the real image and the generated image, and then achieves Nash equilibrium.

Specifically, in the problem of MRI image reconstruction, x is defined as the fully sampled MRI image, and z is the undersampled zero-filled MRI image. The theoretical formula of the original GAN is:

| (8) |

| (9) |

where Pdata(x) is the fully sampled MRI image distribution, Pz(z) is the undersampled zero-filled MRI image distribution. The optimization process of the original GAN is essentially to reduce the Jensen–Shannon divergence (JSD) between Pdata(x) and Pz(z)

| (10) |

When , JSD(Pdata‖Pz) gets the minimum value 0. Therefore, ideally, when the generator generates sufficiently real samples, the discriminator cannot distinguish between true and false samples and should output a probability value of 0.5. However, in actual training, the above formula may cause the expected output of the discriminator D to be 1. This is because the original GAN theoretical formula ignores a priori knowledge, for instance, in a minibatch, half of the samples' input to the discriminator are real data and the other half are generated data.

We use the relative average discriminator (Jolicoeur-Martineau, 2018) and believe that the discriminator should estimate the probability that the given full sampling MRI is more realistic than the reconstruction MRI, on average, by making full use of the above prior knowledge. Therefore, the theoretical formula after using the relative average discriminator in our work is

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

where C(·) is the output of the discriminator network.

Spectral Normalization

Miyato et al. (2018) proposed to apply spectral normalization (SN) to the discriminator network to stabilize GAN training. In this study, we also use spectral normalization in the weights of the generator network and discriminator network. The spectral normalization method uses the spectral norm on the parameter matrix of the discriminator and generator network, so that the network satisfies the Lipschitz constraint, thereby smoothing the network parameter to stabilize training.

Loss Function

The loss function is used to evaluate the gap between the reconstructed image and the fully sampled image, which is the optimization object of the GAN. The smaller the loss function value, the smaller the gap between the reconstructed image and the fully sampled image, and the better the reconstruction effect. A reasonable loss function can provide accurate gradient information for network training, thereby improving reconstruction performance. We use a combined loss function that combines perceptual loss, pixel loss, frequency domain loss, and adversarial loss to comprehensively evaluate the fitting ability of the network.

The pixel loss Lpixel and frequency domain loss Lfrequency are based on Mean Square Error(MSE), can be defined as follows

| (14) |

| (15) |

where xt and xu are fully sampled and reconstructed MR images in the image domain, respectively. yt and yu correspond to the frequency domain data of xt and xu, respectively. The perceptual loss and adversarial loss are defined as

| (16) |

| (17) |

where fVGG16 represents the VGG16 network (Russakovsky et al., 2015), D(·) represents the relative average discriminator.

Therefore, the final total loss function can be expressed as

| (18) |

where α, β and γ are the weight parameter of each loss function.

Experiments

Experimental Setup

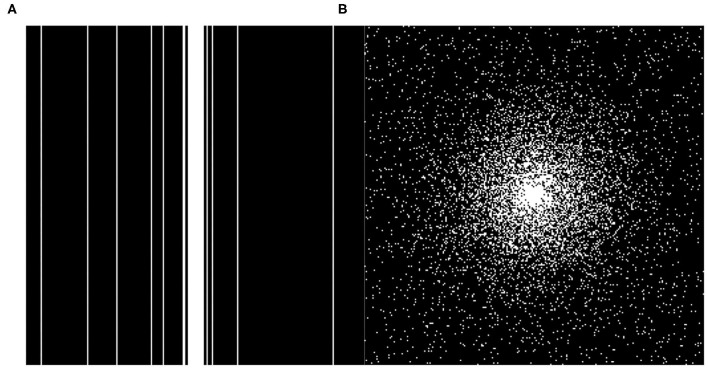

The datasets used in this article are downloaded from the Diencephalon Challenge (https://www.synapse.org/#!Synapse:syn3193805/wiki/217780) in the public repository of the MICCAI 2013 grand challenge. The MRI data acquisition method is MPRAGE, the scanning matrix size is 256 × 256 × 287, and the resolution is 1 × 1 × 1 mm. We randomly selected 130 3D neuro-MRI images from the data set to verify the proposed SARA-GAN model. In the experiments, 70 samples (15,816 effective 2D MRIs) were used as the training set, 30 samples (5,073 effective 2D MRIs) were used as the validation set, and 30 samples (5,198 effective 2D MRIs) were used as the test set. In order to enhance the network performance, we applied data augmentation to the training dataset, including flipping (left to right), rotating ±20 degrees, shifting 10% along the x-axis and y-axis, random zooming between 0.9 times and 1.1 times, random brightness changes, and the random elastic transformation with alpha of 255 × 3 and sigma of 255 × 0.10. We use TensorFlow 1.12.0 and Python framework to program, and train the proposed model on a TeslaV100-SXM2 GPU under a CentOS system environment. Two undersampling modes, including 1-dimensional Gaussian distribution and 2-dimensional Gaussian distribution, three sampling rates of 10, 20, and 30% (Corresponding to 10×, 5×, and 3.3× acceleration factors respectively) were used for obtaining undersampling MRI. We train the model separately for each sampling mode. The sampling modes are shown in Figure 4. The contrast experiments were carried out under the above conditions.

Figure 4.

The two different under sampling masks. (A) 1D Gaussian mask and (B) 2D Gaussian mask.

The input and output image size of the generator is 256 × 256, batch size set to 16. We set the learning rate of the generator and the discriminator to 0.0001 and 0.0002, respectively, so that the generator and the discriminator can learn simultaneously. Since loss items in the combined loss are inconsistent on the number scale; therefore, we use hyperparameters α, β and γ to balance them into a similar scale to make the final loss function more accurate. The hyperparameters α, β, and γ in the combined loss function are set to 15, 0.1, and 0.0025, respectively. The choice of these hyperparameters were tuned empirically for better reconstruction performance.

We use the Adam optimizer with Gradient Centralization (Yong et al., 2020) to optimize the loss function, and set the exponential decay rate for the 1st moment estimates (β1) to 0.5, and the exponential decay rate for the 2nd moment estimates (β2) to 0.999. To prevent over-fitting, we use the normalized mean square error (NMES) as an indicator to evaluate the fitting effect of the network on the validation set every epoch. After the network is trained for 30 epochs, the training is terminated, and the optimal model with the smallest NMSE is saved.

Reconstruction Quality Evaluation

In our experiment, the peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) and structural similarity index measure (SSIM) were used as evaluation indexes of the reconstructed image. PSNR and SSIM are defined as following

| (19) |

where x represents the full sampling MRI, y represents the network reconstructed MRI, i and j represent the coordinates of image pixels, and M, N represents the size of the image.

| (20) |

where μx and μy represent the means of image x and y, σx and σy represent the variances of image x and y, respectively.

Results

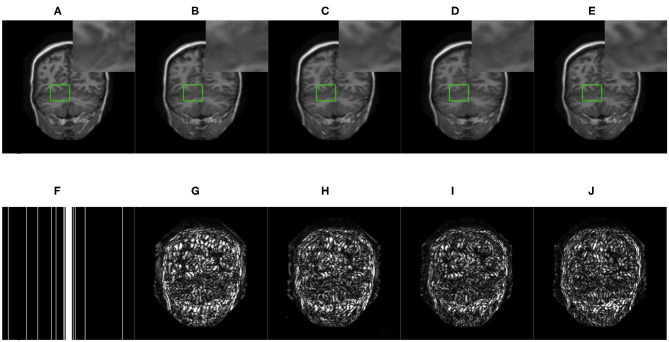

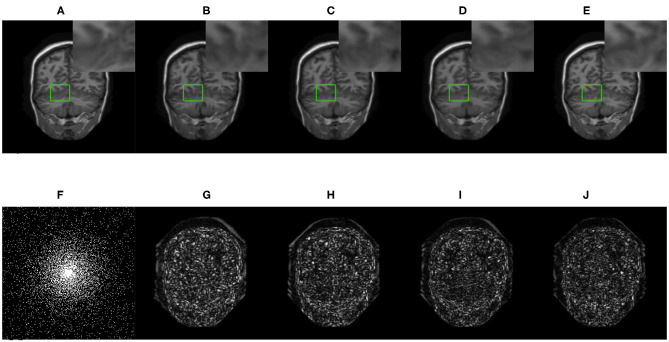

We compared three GAN-based MRI reconstruction models, i.e., DAGAN, DAWGAN, DAWGAN-GP, and the compared methods all used the best parameter settings. Figures 5, 6 show the reconstruction effect of a typical MRI for the 10-fold accelerated k-space data masked with the Gaussian distribution using a different method. We chose to zoom in on a specific area of the MRI to compare the reconstruction details. From the local enlarged image, we can conclude that the reconstructed image obtained by the DAGAN method loses most of the texture information. DAWGAN and DAWGAN-GP perform slightly better than DAGAN, but there is still a big gap compared with full sampling MRI. Compared with the other three GAN-based methods, our method can restore more texture details, and the texture edge is clearer. The second line of Figures 5, 6 shows the reconstruction error map of different algorithms, and the color of pixels indicates the reconstruction error of the corresponding position. It can be seen that the reconstruction error of our method is less than that of other methods, indicating that the reconstructed MRI is closer to the full sampling MRI. Table 1 shows the quantitative comparison of the reconstruction effects of different methods. We calculate the average PSNR and SSIM of each method on the test set to evaluate the reconstruction performance of the model. Except for the first row in the table, our results are close to the DAWGAN-GP method. In the other undersampling modes, our method obtains higher PSNR and SSIM. The average PSNR is improved 0.04 dB ~ 0.96 dB over the DAWGAN-GP and the corresponding SSIM improvements are 0.0003 ~ 0.0008. In order to illustrate the performance of the proposed method, we estimate the statistical significancy using the Wilcoxon rank sum test (p < 0.05 indicates the significant difference). We find that except for 10% 2D Gaussian sampling experiment we have a similar performance between DAWGAN-GP and SARA-GAN (p = 0.1849), other experiments have demonstrated that our SARA-GAN has outperformed other methods significantly (most p-values are < 0.001).

Figure 5.

The reconstructed MRI for the 10-fold accelerated k-space data masked with the 1D Gaussian distribution by using different GAN-based methods. (A) Fully-sampled MRI, (B) DAGAN, (C) DAWGAN, (D) DAWGAN-GP, (E) SARA-GAN, (F) 1D mask, (G) DAGAN(error), (H) DAWGAN(error), (I) DAWGAN-GP(error), and (J) SARA-GAN(error).

Figure 6.

The reconstructed MRI for the 10-fold accelerated k-space data masked with the 2D Gaussian distribution by using different GAN-based methods. (A) Fully-sampled MRI, (B) DAGAN, (C) DAWGAN, (D) DAWGAN-GP, (E) SARA-GAN, (F) 2D mask, (G) DAGAN(error), (H) DAWGAN(error), (I) DAWGAN-GP(error), and (J) SARA-GAN(error).

Table 1.

The average reconstruction performances of different methods on the test set (mean ± std).

| DAGAN | DAWGAN | DAWGAN-GP | SARA-GAN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask: 1D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 34.0484 ± 4.81 | 0.9538 ± 2.20e-2 | 35.4455 ± 4.57 | 0.9654 ± 1.71e-2 | 36.3499 ± 4.27 | 0.9718 ± 1.37e-2 | 36.3926 ± 4.73 | 0.9713 ± 1.46e-2 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 40.2395 ± 4.23 | 0.9857 ± 6.41e-3 | 41.4284 ± 4.45 | 0.9894 ± 5.18e-3 | 42.6101 ± 3.92 | 0.9923 ± 3.77e-3 | 43.2054 ± 4.49 | 0.9929 ± 3.71e-3 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 40.8891 ± 4.46 | 0.9873 ± 5.88e-3 | 42.1798 ± 4.61 | 0.9907 ± 4.53e-3 | 42.9149 ± 3.69 | 0.9928 ± 3.41e-3 | 43.3522 ± 4.34 | 0.9931 ± 3.47e-3 |

| Mask: 2D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 39.7242 ± 5.01 | 0.9801 ± 1.06e-2 | 40.7623 ± 4.68 | 0.9861 ± 7.75e-3 | 41.1885 ± 4.43 | 0.9876 ± 6.85e-3 | 41.6323 ± 5.25 | 0.9881 ± 6.83e-3 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 41.5595 ± 4.93 | 0.9857 ± 7.74e-3 | 41.7733 ± 5.15 | 0.9880 ± 6.84e-3 | 42.9742 ± 4.61 | 0.9912 ± 5.05e-3 | 43.4991 ± 5.15 | 0.9920 ± 4.84e-3 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 44.3886 ± 5.01 | 0.9934 ± 3.95e-3 | 44.2812 ± 5.11 | 0.9932 ± 4.03e-3 | 44.7868 ± 3.86 | 0.9947 ± 2.97e-3 | 45.7536 ± 4.99 | 0.9951 ± 3.03e-3 |

The bold value means that the experimental result value is the best.

With the increase of the acceleration factor, the reconstruction effect of either method becomes worse. At the same time, the reconstruction effect of 2-dimensional Gaussian sampling mode is obviously better than that of 1-dimensional Gaussian sampling. This is because the brain MRI has fewer texture details than natural images. The main information of brain MRI is concentrated in the low-frequency part of k-space, and the Gaussian sampling mode happens to also mainly collects the low-frequency part. Therefore, with the increase of sampling rate and sampling dimension, the information of the low-frequency part is more collected, so the reconstruction effect is also improved.

The real MRI sampling process often contains random noise. To simulate the real scene and evaluate the anti-noise ability of the model, we added 30 and 40 dB Gaussian white noise to the test set MRI and retested the above methods. Tables 2, 3 respectively show the reconstruction results of different algorithms on the test set with 30 and 40 dB Gaussian white noise. It can be seen from the table that, the average PSNR is improved by 0.004 ~ 0.841 dB over the DAWGAN-GP and the corresponding SSIM improvements are about 0.0004 ~ 0.0008. Despite the addition of a certain intensity of noise, our method still obtains a good reconstruction effect and is better than other GAN-based methods. This shows that our method has good anti-noise performance and the potential for practical application.

Table 2.

The average reconstruction performances of different methods on the test set with 30dB noise.

| DAGAN | DAWGAN | DAWGAN-GP | Proposed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask: 1D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 33.4169 | 0.9364 | 34.8801 | 0.9582 | 35.0774 | 0.9450 | 35.3201 | 0.9535 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 38.9860 | 0.9742 | 39.2584 | 0.9600 | 40.5054 | 0.9805 | 41.4684 | 0.9878 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 38.0020 | 0.9279 | 39.4411 | 0.9579 | 40.7167 | 0.9825 | 41.5242 | 0.9886 |

| Mask: 2D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 39.1818 | 0.9775 | 39.5594 | 0.9827 | 40.5227 | 0.9859 | 40.5901 | 0.9861 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 40.3423 | 0.9807 | 40.1344 | 0.9843 | 41.6388 | 0.9890 | 41.7555 | 0.9895 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 42.5157 | 0.9907 | 42.3948 | 0.9901 | 42.6534 | 0.9919 | 43.0708 | 0.9922 |

The bold value means that the experimental result value is the best.

Table 3.

The average reconstruction performances of different methods on the test set with 40dB noise.

| DAGAN | DAWGAN | DAWGAN-GP | Proposed | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask: 1D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 33.9782 | 0.9527 | 35.3805 | 0.9648 | 36.2549 | 0.9711 | 36.2590 | 0.9703 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 40.0935 | 0.9849 | 41.3256 | 0.9880 | 42.3872 | 0.9918 | 42.9586 | 0.9926 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 40.3222 | 0.9828 | 41.6212 | 0.9878 | 42.6548 | 0.9924 | 43.1355 | 0.9928 |

| Mask: 2D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 39.6494 | 0.9797 | 40.2391 | 0.9843 | 41.1332 | 0.9874 | 41.5031 | 0.9879 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 41.4073 | 0.9852 | 41.0897 | 0.9866 | 42.8114 | 0.9910 | 43.2453 | 0.9918 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 44.1260 | 0.9931 | 44.0760 | 0.9929 | 44.5119 | 0.9944 | 45.3533 | 0.9949 |

The bold value means that the experimental result value is the best.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study is to accurately reconstruct clear MR images from under-sampled MRI k-space data, thereby accelerating MR imaging. The experimental results have demonstrated that the proposed SARA-GAN method can obtain high-quality reconstructed MRI, even in the presence of noise. In the SARA-GAN method, we propose to use the relative average discriminator instead of the original discriminator, and the self-attention mechanism to achieve global reference. Compared with the other state-of-the-art GAN-based MRI reconstruction methods, such as DAGAN, DAWGAN, DAWGAN-GP, our SARA-GAN method can provide outstanding reconstruction performance and generate MRI images with a stronger integrity, more details, and higher evaluation indices.

The convolution operation on CNN can only work in the local domain of the convolution kernel, which makes the network miss a lot of global information. The self-attention mechanism is proposed to solve the above problem by capturing long-range interactions. In this study, we apply the self-attention mechanism in the up-sampling block of the generator to combine local and global spatial information. To evaluate the impact of the self-attention mechanism on network reconstruction, we removed the self-attention layer in the up-sampling block of the generator and conducted training and testing under the same experimental conditions. The average PSNR and SSIM of the test set are shown in Table 4. As can be seen from the table, in all under-sampling modes, the self-attention mechanism affects improving the quality of reconstructed MRI images. The average PSNR is improved 0.32 ~ 1.03 dB and the corresponding SSIM improvements are 0.0005 ~ 0.0027.

Table 4.

The influence of self-attention mechanism and SN on PSNR and SSIM of the reconstructed image.

| RA-GAN | SARA-GAN(NoSN) | SARA-GAN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mask: 1D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 35.9669 | 0.9686 | 35.6708 | 0.9669 | 36.3926 | 0.9713 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 42.8805 | 0.9924 | 42.9769 | 0.9925 | 43.2054 | 0.9929 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 42.7548 | 0.9920 | 43.1507 | 0.9927 | 43.3522 | 0.9931 |

| Mask: 2D Gaussian | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM | PSNR | SSIM |

| Sample rate: 10% | 41.1679 | 0.9867 | 40.5628 | 0.9848 | 41.6323 | 0.9881 |

| Sample rate: 20% | 43.0552 | 0.9912 | 42.1689 | 0.9894 | 43.4991 | 0.9920 |

| Sample rate: 30% | 44.7239 | 0.9940 | 44.3378 | 0.9932 | 45.7536 | 0.9951 |

The bold value means that the experimental result value is the best.

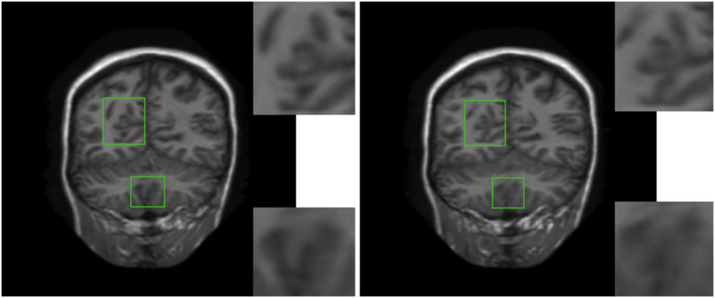

In order to verify the visual effect of the long-range dependence constructed by the self-attention mechanism on the reconstructed MRI, we selected a typical MRI and enlarged the texture-rich regions locally, as shown in Figure 7. Observation shows that the brain texture in the left picture is rich in detail and structural information is relatively complete. Comparing the enlarged image of the same area, the left image has a clear texture boundary and relatively complete color blocks, while the right image has blurry borders, and the color blocks are somewhat broken. Therefore, under the action of the self-attention mechanism, the integrity of reconstructed MRI is stronger and the visual effect is improved.

Figure 7.

The visual influence of self-attention mechanism on the reconstructed image. Proposed RASA-GAN (PSNR: 33.5931) and Proposed (NoSA) RA-GAN (PSNR: 32.9152).

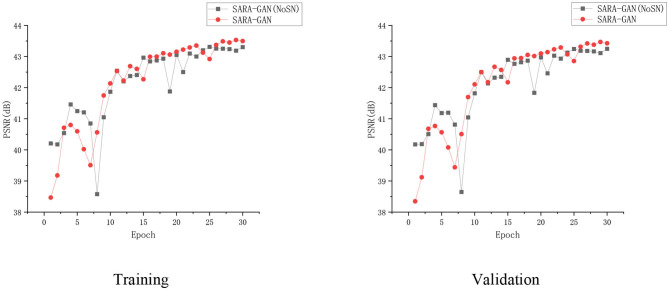

We also apply spectral normalization to the parameter matrix of the generator and discriminator.

Spectral normalization makes the parameter matrix meet 1-Lipschitz continuity by applying the spectral norm to the network parameters, which limits the network gradient change, thereby making the training process more stable. We have conducted the convergence analyses in every epoch by using SARA-GAN and SARA-GAN without SN methods in the case of the 30% sampling rate with a 1D Gaussian mask. As shown in Figure 8, the convergence of SARA-GAN method is more stable than SARA-GAN without the SN method. Table 4 also shows the experimental results of SARA-GAN without the SN method on the test set. It can be seen that SN significantly improves the quality of network reconstruction MRI. Under the same number of iterations, due to the improvement of training stability, the method with SN can achieve a more optimized state.

Figure 8.

The convergence curve of the PSNR vs. the Epoch number in the case of a 30% sampling rate with the 1D Gaussian mask. Training and validation.

Conclusion

In this study, a new MRI reconstruction method, named SARA-GAN, was proposed to reduce k-space sampling and accelerate MRI imaging. Our method combines the self-attention mechanism with relative average discriminator. Compared with other GAN-based methods, such as DAGAN, DAWGAN, and DAWGAN-GP, the experimental results show that our method can obtain more accurate reconstructed MRI with a higher PSNR and SSIM. Especially through the long-range global dependence constructed by the self-attention mechanism, the proposed method can reconstruct images with more realistic details and stronger integrity. At the same time, the proposed method has a certain ability of noise tolerance and short reconstruction time. It provides a promising approach to speed up the MRI.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://mrbrains13.isi.uu.nl/data/, MICCAI 2013 grand challenge public data set.

Author Contributions

ZY, MJ, YW, BW, and GY: conceptualization. ZY, MJ, YW, BW, YL, PW, and GY: methodology. ZY, MJ, YW, and BW: formal analysis, investigation, and writing—original draft preparation. WM-S, ZN, and GY: writing—review and editing. MJ and GY: funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the study conception, design, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

Co-authors ZN and WM-S are employed by Aladdin Healthcare Technologies Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (61672466 and 62011530130), in part by the Key Research and Development Program of Zhejiang Province (2020C03060), in part by the Joint Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation (LSZ19F010001), in part by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ20F02003 and LY18D060009), in part by the Science Technology Department Program of Zhejiang Province (LGG18H180001), in part by the 521 Talents project of Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, in part by IIAT Hangzhou, in part by the European Research Council Innovative Medicines Initiative on Development of Therapeutics and Diagnostics Combatting Coronavirus Infections Award DRAGON: rapiD and secuRe AI imaging based diaGnosis, stratification, fOllow-up, and preparedness for coronavirus paNdemics [H2020-JTI-IMI2 101005122], and in part by the AI for Health Imaging Award CHAIMELEON: Accelerating the Lab to Market Transition of AI Tools for Cancer Management [H2020-SC1-FA-DTS-2019-1 952172].

References

- Aggarwal H. K., Mani M. P., Jacob M. (2018). MoDL: model-based deep learning architecture for inverse problems. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 38, 394–405. 10.1109/TMI.2018.2865356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akçakaya M., Moeller S., Weingärtner S., Ugurbil K. (2019). Scan-specific robust artificial-neural-networks for k-space interpolation (RAKI) reconstruction: database-free deep learning for fast imaging. Magn. Resonance Med. 81, 439–453. 10.1002/mrm.27420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjovsky M., Chintala S., Bottou L. (2017). Wasserstein gan. arXiv. Available online at: https://arxiv.org/pdf/1701.07875.pdf

- Boyd S., Parikh N., Chu E. (2011). Distributed optimization and statistical learning via the alternating direction method of multipliers. Now Foundations and Trends. p.128 10.1561/9781601984616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J., Liu S., Liu H., Lu H. (2020). CS-MRI reconstruction based on analysis dictionary learning and manifold structure regularization. Neural Netw. 123, 217–233. 10.1016/j.neunet.2019.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Shi F., Christodoulou A. G., Xie Y., Zhou Z., Li D. (2018). Efficient and accurate MRI super-resolution using a generative adversarial network and 3D multi-level densely connected network, in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. (Granada: Springer; ), 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Pan Z., Zhang P., Li Y., Ku W. (2019). Compressive sensing image recovery using dictionary learning and shape-adaptive DCT thresholding. Magn. Reson. Imaging 55, 60–71. 10.1016/j.mri.2018.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duyn J. H., Yang Y., Frank J. A., Veen J. W. (1998). Simple correction method for k-space trajectory deviations in MRI. J. Magn. Reson. 132, 150–153. 10.1006/jmre.1998.1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Gueddari L., Ciuciu P., Chouzenoux E., Vignaud A., Pesquet J.-C. (2019). Calibrationless oscar-based image reconstruction in compressed sensing parallel MRI, in 2019 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (Venice: ), 1532–1536. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow I., Pouget-Abadie J., Mirza M., Xu B., Warde-Farley D., Ozair S., et al. (2014). Generative adversarial nets, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Montréal: ), 2672–2680. [Google Scholar]

- Haldar J. P., Hernando D., Liang Z. P. (2011). Compressed-sensing MRI with random encoding. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 30, 893–903. 10.1109/TMI.2010.2085084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He K., Zhang X., Ren S., Sun J. (2015). Delving deep into rectifiers: surpassing human-level performance on imagenet classification, in: Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (Santiago: ), 1026–1034. 10.1109/ICCV.2015.123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Paisley J., Lin Q., Ding X., Fu X., Zhang X.-P. (2014). Bayesian nonparametric dictionary learning for compressed sensing MRI. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 23, 5007–5019. 10.1109/TIP.2014.2360122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang M., Yuan Z., Yang X., Zhang J., Gong Y., Xia L., et al. (2019). Accelerating CS-MRI reconstruction with fine-tuning Wasserstein generative adversarial network. IEEE Access 7, 152347–152357. 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2948220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jolicoeur-Martineau A. (2018). The relativistic discriminator: A key element missing from standard GAN, in International Conference on Learning Representations (Vancouver: ). [Google Scholar]

- Kabasawa H. (2012). Magnetic resonance imaging apparatus and magnetic resonance imaging method. J. Biomech. Eng. 127, 148 −157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon G., Han C., Kim D. (2019). Generation of 3D brain MRI using auto-encoding generative adversarial networks, in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (Shenzhen: ), 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- LeCun Y., Bengio Y., Hinton G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444. 10.1038/nature14539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledig C., Theis L., Huszár F., Caballero J., Cunningham A., Acosta A., et al. (2017). Photo-realistic single image super-resolution using a generative adversarial network, in: Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (Honolulu: ), 4681–4690 [Google Scholar]

- Lee J., Kim H., Chung H., Ye J. C. (2020). Deep learning fast MRI using channel attention in magnitude domain, in: 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (Lowa City: ), 917–920. [Google Scholar]

- Liang D., Cheng J., Ke Z., Ying L. (2020). Deep magnetic resonance image reconstruction: Inverse problems meet neural networks. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 37, 141–151. 10.1109/MSP.2019.2950557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang Z.-P., Lauterbur P. C. (2000). Principles of Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Signal Processing Perspective. (SPIE Optical Engineering Press; ). [Google Scholar]

- Luo W., Li Y., Urtasun R., Zemel R. (2016). Understanding the effective receptive field in deep convolutional neural networks, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Barcelona: ), 4898–4906. [Google Scholar]

- Lustig M., Donoho D., Pauly J. M. (2010). Sparse MRI: the application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 58, 1182–1195. 10.1002/mrm.21391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig M., Donoho D. L., Santos J. M., Pauly J. M. (2008). Compressed Sensing MRI. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 25, 72–82. 10.1109/MSP.2007.914728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyu Q., You C., Shan H., Zhang Y., Wang G. (2019). Super-resolution MRI and CT through GAN-circle, in Developments in X-Ray Tomography XII: International Society for Optics and Photonics (Paris: ), 111130X. 10.1117/12.2530592 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra D., Bozorgtabar B., Garnavi R. (2019). Image super-resolution using progressive generative adversarial networks for medical image analysis. Comp. Med. Imaging Graphics 71, 30–39. 10.1016/j.compmedimag.2018.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyato T., Kataoka T., Koyama M., Yoshida Y. (2018). Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks, in International Conference on Learning Representations (Vancouver: ). [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M., Alley M., Demmel J., Keutzer K., Vasanawala S., Lustig M. (2012). Fast $\ell_1 $-SPIRiT compressed sensing parallel imaging MRI: scalable parallel implementation and clinically feasible runtime. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 31, 1250–1262. 10.1109/TMI.2012.2188039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radford A., Metz L., Chintala S. (2016). Unsupervised representation learning with deep convolutional generative adversarial networks, in International Conference on Learning Representations (San Juan: ). [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankar S., Bresler Y. (2010). MR image reconstruction from highly undersampled k-space data by dictionary learning. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 30, 1028–1041. 10.1109/TMI.2010.2090538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russakovsky O., Deng J., Su H., Krause J., Satheesh S., Ma S., et al. (2015). Imagenet large scale visual recognition challenge. Int. J. Comput. Vis 115, 211–252. 10.1007/s11263-015-0816-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shimron E., Webb A. G., Azhari H. (2020). CORE-deblur: parallel MRI reconstruction by deblurring using compressed sensing. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 72, 25–33. 10.1016/j.mri.2020.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J., Li H., Xu Z. (2016). Deep ADMM-Net for compressive sensing MRI, in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Liang D., King K. F., Nagarsekar G., Chang Y., Ying L. (2012). Improving GRAPPA using cross-sampled autocalibration data. Magn. Reson. Med. 64, 1042–1053. 10.1002/mrm.23083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Su Z., Ying L., Peng X., Zhu S., Liang F., et al. (2016). Accelerating magnetic resonance imaging via deep learning, in 2016 IEEE 13th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (Prague: ), 514–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G., Yu S., Dong H., Slabaugh G., Dragotti P. L., Ye X., et al. (2017). DAGAN: deep de-aliasing generative adversarial networks for fast compressed sensing MRI reconstruction. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 37, 1310–1321. 10.1109/TMI.2017.2785879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong H., Huang J., Hua X., Zhang L. (2020). Gradient centralization: a new optimization technique for deep neural networks. Eds. Vedaldi A., Bischof H., Brox T., Frahm J.M. Computer Vision – ECCV 2020. (Cham: Springer; ) p. 635-652. 10.1007/978-3-030-58452-8_37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Goodfellow I., Metaxas D., Odena A. (2019). Self-attention generative adversarial networks, in International Conference on Machine Learning. (Long Beach: PMLR; ), 7354–7363. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B., Liu J. Z., Cauley S. F., Rosen B. R., Rosen M. S. (2018). Image reconstruction by domain-transform manifold learning. Nature 555, 487–492. 10.1038/nature25988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J.-Y., Park T., Isola P., Efros A. A. (2017). Unpaired image-to-image translation using cycle-consistent adversarial networks, in Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (Venice: ), 2223–2232. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: https://mrbrains13.isi.uu.nl/data/, MICCAI 2013 grand challenge public data set.