Abstract

At the end of December 2019, the rapid spread of the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) disease and, subsequently, deaths around the world, lead to the declaration of the pandemic situation in the world. At the beginning of the epidemic, much attention is paid to person-to-person transmission, disinfection of virus-contaminated surfaces, and social distancing. However, there is much debate about the routes of disease transmission, including airborne transmission, so it is important to elucidate the exact route of transmission of the COVID-19 disease. To this end, the first systematic review study was conducted to comprehensively search all databases to collect studies on airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments. In total, 14 relevant and eligible studies were included. Based on the findings, there is a great possibility of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments. Therefore, some procedures are presented such as improving ventilation, especially in hospitals and crowded places, and observing the interpersonal distance of more than 2 m so that experts in indoor air quality consider them to improve the indoor air environments. Finally, in addition to the recommendations of the centers and official authorities such as hand washing and observing social distancing, the route of air transmission should also be considered to further protect health personnel, patients in hospitals, and the public in other Public Buildings.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Airborne transmission, Indoor air, Ventilation

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The SR was conducted to compile studies on airborne transmission of virus in indoor air.

-

•

In total, 14 relevant and eligible studies were included.

-

•

There is a great possibility of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air.

-

•

Improving ventilation is essential, especially in hospitals and crowded places.

1. Introduction

At the end of December 2019, a novel human coronavirus belonging to the subgenus Betacoronavirus emerged for the first time in Wuhan city, central Hubei province, China. The virus spread rapidly in all countries and territories of the world. Therefore, on March 12, 2020, the world health organization (WHO) declared the novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which causes severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), as a global pandemic (Amoatey et al., 2020; Carraturo et al., 2020; Correia et al., 2020; Noorimotlagh et al., 2020a; Ansari and Ahmadi Yousefabad, 2020).

WHO guidelines declared that the main route of transmission of COVID-19 is person-to-person transmission, especially prolonged and unprotected exposure to the virus. Therefore, it is recommended that the main precautions to avoid exposure to the virus are hand washing several times in a day and observe a social distance of at least 1 m (arm's length) (Ghinai et al., 2020; Morawska and Cao, 2020; Organization, 2020). Health officials declared that the virus is transmitted primarily by direct or indirect exposure to droplets from coughing or sneezing and surfaces contaminated by patients. Based on these precautions, countries and health officials have enacted emergency quarantine conditions and lockdown procedures that impede the movement of people in society (Ansari and Ahmadi Yousefabad, 2020; Lewis, 2020; Morawska and Cao, 2020; Organization, 2020).

Unfortunately, despite all the above-mentioned precautions, disease prevention and control procedures, all countries in the world continue to suffer from the disease and pandemic situation, due to high levels of infection and mortality. Also, recently Domingo et al., 2020 reviewed the influence of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on the COVID-19 pandemic. They suggested that based on the results of the reviewed studies, chronic exposure to some of the air pollutants can lead to more severe and deadly forms of the disease and delay and/or complicate the recovery of patients from COVID-19 disease (Domingo et al., 2020). Therefore, we can assume that the various aspects of the virus transmission mechanisms are not fully understood and we have a rudimentary understanding of the spread of the disease, including an important question about the route of transmission of the virus.

There is a great debate among researchers and scientists about the routes of transmission of the virus, including airborne transmission, especially in the indoor environment. Besides, several studies reported different results that generate more debate (Liu et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020a; Stadnytskyi et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Buonanno et al., 2020; Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020; Faridi et al., 2020; Kenarkoohi et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020b). Therefore, to determine the answer to the important question about airborne transmission, the aim of this systematic review (SR) is to systematically collect all experimental studies related to airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments.

2. Methods

This study is the first SR of all articles available from the onset of COVID-19 disease to the present and is based on the airway for transmission of COVID-19 in indoor air using Cochrane templates for a rapid review of COVID-19 according to PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for SRs and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/InDevelopment.aspx) (Noorimotlagh et al., 2020b).

Systematic searches were carried out in the electronic databases of Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science, PubMed (MEDLINE), Elsevier Bibliographic Database (Scopus) and Google Scholar using MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) with the following keywords: (“COVID-19" [Supplementary Concept] OR “Human Coronaviruses " OR “HCoV” OR “Coronaviruses” OR “CoV” OR “Novel Coronaviruses” OR “nCov” OR “2019 Novel Coronavirus” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome −2"[Mesh] OR “SARS-CoV-2″) AND (“Aerosols” [Mesh] OR “Airborne” OR “Inhalation” OR “Transmission” OR “hospital” OR “indoor air").

Studies were selected according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria and then included in the present review. The inclusion criteria were: electronic version of the article is available, the language of the article is English, and it focuses on the air route for transmission of COVID-19 in an indoor air environment. In this SR, studies were systematically excluded if they only contained abstracts, literature reviews, book reviews, guidelines, protocols, book chapters, letters to editors, conference abstracts, non-English language (other languages such as Italian, Spanish, French, German,..), oral presentation, dissertations, white papers, etc. Two reviewers (ZN & SM) independently extracted data from each original publication. The information was the name of author, the location of the study, the objective of the article, the design of the study, the meteorological parameters (such as particulate matter (PM), relative humidity (RH) and temperature) and the main key results.

3. Results

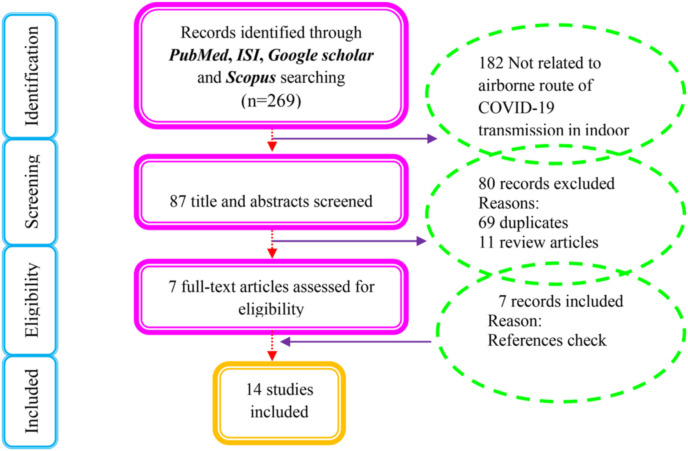

An initial search of 269 articles was systematically performed in four databases. When evaluating the title and abstract, 182 were eliminated for not being related to the airway of transmission of COVID-19 indoors, duplicates and review articles. Based on the selection of full-text articles, three records were also removed because they were letters to editor and discussion. Finally, fourteen studies were eligible and included in this SR based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (Wang and Yoneda, 2020; Buonanno et al., 2020; Vuorinen et al., 2020; Stadnytskyi et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Faridi et al., 2020; Kenarkoohi et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020a; Santarpia et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2020; Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Masoumbeigi et al., 2020; Razzini et al. (2020)).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for the selection of eligible studies.

Table 1 shows the main findings of the included reviewed studies. Among the selected and included studies, eleven studies conducted experimental studies to determine the possible airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments (Santarpia et al., 2020a; Santarpia et al., 2020b; Liu et al., 2020; Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020; Stadnytskyi et al., 2020; Faridi et al., 2020; Kenarkoohi et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; MasoumbeigI et al., 2020; Razzini et al., 2020). These studies were conducted in Iran (n = 3), USA (n = 2), China (n = 1), Spain (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Philadelphia (n = 1), Korea (n = 1) and Italy (n = 1). Of the 14 records, three studies examined the main hypothesis of the present SR based on the simulation method (Wang and Yoneda, 2020; Buonanno et al., 2020; Vuorinen et al., 2020). These studies were conducted in Japan (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), and Finland (n = 1). The main findings of the studies reviewed to determine our hypothesis about the possibility of airborne transmission of COVID-19 are discussed in the next section.

Table 1.

The main characteristics of the studies reviewed in this SR.

| Study ID | The main objective | Study Design | Meteorology Parameters |

The main key finding | Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM | RH | Tem | |||||

| (Santarpia et al., 2020a), USA | Detection of the virus in air and surface | Experimental | N* | N | N | Viral contamination confirmed in all samples | During curing for COVID-19 patients, airborne isolation precautions were recommended. |

| (Masoumbeigi et al., 2020), Iran | Detection of the virus in hospital indoor air | Experimental | N | R | R | The occurrence of the virus in hospital air samples was not confirmed. | Due to the close contact with patients, the protection of medical staff and healthcare workers must be considered according to international and national strict guidelines. |

| (Santarpia et al., 2020b), USA | Transmission potential of SARS-CoV-2 in Viral Shedding | Experimental | N | N | N | Air samples and toilet facilities had evidence of viral contamination | Indirect contact through airborne transmission played a role in the spread of disease, therefore the use of airborne isolation precautions was supported |

| (Kim et al., 2020), Korea | Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in hospital indoor air | Experimental | N | N | N | There is no positive results for the SARS-CoV-2 RNA in the indoor air samples | They suggest that remote air transmission (more than 2 m) of SARS-CoV-2 from hospitalized COVID-19 patient is uncommon. |

| (Liu et al., 2020), China | Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in two Hospitals |

Experimental | N | N | N | SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in isolation wards, ventilated patient rooms, toilet areas, and medical staff areas. | Room ventilation, open space, sanitization of protective apparel, and proper use and disinfection of toilet areas can effectively limit the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in aerosols |

| (Faridi et al., 2020), Iran | Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environment of hospital | Experimental | R* | R | R | All indoor air samples were negative. | Implement in vivo experiments using actual patient cough, breath, and sneeze aerosols to evaluate the possibility of production of the airborne size carrier aerosols and the viability fraction of the embedded virus in these carrier aerosols. |

| (Kenarkoohi et al., 2020), Iran | The monitoring of hospital indoor air environment for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 virus | Experimental | R | R | R | They indicated two viral RNA positive air samples in the indoor air environment of the hospital were found. | More studies and quantitative analysis are required to determine the role of actual cough mechanisms in the emission of airborne size carrier aerosols. |

| (Razzini et al., 2020), Italy | Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in hospital indoor air | Experimental | N | N | N | The results showed that all the indoor air samples collected from the ICU and the corridor as a contaminated area, were positive. | The authors recommended that strict disinfection precautions, protective measures and hand hygiene be taken for medical personnel and isolation from airborne transmission. |

| (Chia et al., 2020), Singapore | Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environment of hospital rooms of infected patients | Experimental | R | R | R | Detection of SARS- CoV-2 PCR-positive particles of sizes more than 4 μm and 1–4 μm in two rooms. Although particles in this size range have the potential to remain in the air longer. | Detailed epidemiological studies of the outbreak are required to determine the relative contribution of various routes of transmission and their correlation with factors at the patient-level. Implement experiments to collect more data on virus viability and infectivity to confirm potential airborne spread of the virus. |

| (Stadnytskyi et al., 2020), Philadelphia | Potential importance of small speech droplets in SARS-CoV-2 airborne transmission | Experimental | N | N | N | The normal speaking could be a substantial probability that causes airborne virus transmission in confined environments | – |

| (Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020), Spain | Evidences of SARS-CoV-2 virus air transmission indoors | Experimental | N | N | N | Surfaces could not be touched by patients or health workers, so viral spreading was unequivocally produced by air transmission. | These data support the recommendation to carry out frequent disinfection of the surfaces of hospitalized patients. |

| (Wang and Yoneda, 2020), Japan | Determination of the optimal penetration factor for evaluating the invasion process of aerosols | Simulation | R | N | N | The penetration mechanism was explored by the proposed optimal penetration factor and the error analysis of each method. They also provided a rapid and accurate assessment method for preventing and controlling the spread of the epidemic. | – |

| (Buonanno et al., 2020), Italy | Estimation of airborne SARS-CoV-2 emission | Simulation | N | N | N | Proper ventilation was a key role in the containment of the virus in indoor environments | – |

| (Vuorinen et al., 2020), Finland | Simulation aerosol transport for SARS-CoV-2 transmission in inhalation indoors | Simulation | N | N | N | The exposure time to inhale O(100) aerosols could range from O(1 s) to O(1 min) or even to O(1 h) depending on the situation | – |

N*= Not reported R*=Reported.

4. Discussion

On December 31, 2019, the COVID-19 outbreak emerged in Wuhan city, Hubei province, China. COVID-19 is a highly pathogenic and contagious, transmissible and invasive pneumococcal disease caused by SARS-CoV-2. There is considerable controversy about the different routes of transmission of the virus in the scientific and research community. At the beginning of the outbreak, the WHO and many studies mainly emphasized that the main routes of transmission are person-to-person transmission, observing social distance, and washing hands several times a day (Ghinai et al., 2020; Morawska and Cao, 2020; Organization, 2020). In recent months, COVID-19 has been exerting profound detrimental effects on all people around the world, such effects have been compounded by the lockdown that has affected all activities that cause global economic disruption.

Airborne transmission is an important route for contagious agents such as the viruses. With this in mind, the airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 was ignored and precautions to prevent and control the airway were not considered. To this end, the evaluation of the possible airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is of utmost importance.

In the present SR study, we conducted a comprehensive literature search for original studies on airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in the indoor air environment, and after examining the collected literature and conducting an in-depth analysis, we included 14 eligible studies (Liu et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020a; Stadnytskyi et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Wang and Yoneda, 2020; Buonanno et al., 2020; Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020; Faridi et al., 2020; Kenarkoohi et al., 2020; Vuorinen et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020b; Kim et al., 2020; Masoumbeigi et al., 2020; Razzini et al., 2020). Among the fourteen included studies, eleven eligible studies were experimental and reported different findings on positive or negative detection of SARS-CoV-2 airborne transmission in indoor air (Liu et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020a; Stadnytskyi et al., 2020; Chia et al., 2020; Orenes-Piñero et al., 2020; Faridi et al., 2020; Kenarkoohi et al., 2020; Santarpia et al., 2020b; Kim et al., 2020; Masoumbeigi et al., 2020; Razzini et al., 2020). Among them, three studies indicated that all indoor air samples in the hospital were negative, thus concluding that there is no evidence that SARS-CoV-2 is transmitted by air (Faridi et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Masoumbeigi et al., 2020). Unlike the results of these studies, other included experimental studies reported positive results that confirmed transmission of the virus through the air. In this context, Kenarkoohi et al. (2020), and Razzini et al., 2020, indicated that air samples positive for viral RNA were found in the indoor air environment of the ICU rooms in the hospital. Furthermore, Chia et al. (2020) confirmed that despite twelve air changes per hour in isolation rooms for airborne infections in the hospital, SARS-CoV-2 PCR-positive particles were found in two of the three airborne infection isolation rooms. However, the area of the room was not reported to consider the ventilation rate (Chia et al., 2020). Besides, Stadnytskyi et al. (2020) investigated the lifespan in air of small speech droplets and their potential in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and confirmed that using highly sensitive laser light scattering observations, in closed and confined environments, it is a substantial possibility that normal speech causes the transmission of airborne viruses. The results of the studies included in the experimental section reveal that there is a great possibility of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments, even with a ventilation rate of 12 air changes per hour. Therefore, it is essential that the ventilation rate is more efficient and takes into account what was reported in the included study.

Three of the fourteen included studies examined the possible airborne transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 using simulation methods (Wang and Yoneda, 2020; Buonanno et al., 2020; Vuorinen et al., 2020). Wang and Yoneda (2020) showed that under the current experimental conditions, due to the minimal effect of the value of the air exchange rate (AER) and fluctuations in concentration, the size-dependent Pavg is the optimal value for the penetration factor of virus-containing particles. Furthermore, they indicated that separation and reentry of virus-containing particles after ventilation capture is inevitable. Buonanno et al. (2020) proposed and developed a novel approach to estimate the quanta emission rate (expressed in quanta h−1) based on the viral load emitted by the mouth of an infectious person (expressed in RNA copies in mL−1). Taking into account the following parameters on the quanta emission rate: respiratory physiological parameters such as the inhalation rate, the type of respiratory activity such as talking, breathing, and whispering, and the level of activity such as light exercise, standing, and resting. They showed that according to the SARS-CoV-2 quanta emission rate, the asymptomatic subject had high emission values both in the circumstances of light exercise during speech and in intense exercise with oral breathing. Therefore, their approach is of great relevance to indoor air quality experts and epidemiologists in managing the indoor microenvironment during epidemic/pandemic situations by taking into accounts the great importance of ventilation in the indoor environment to reduce the spread of the virus (Buonanno et al., 2020). Vuorinen et al. (2020) using numerical simulations to model aerosol transport and virus exposure relative to the SARS-CoV-2 virus by indoor inhalation. Using applied theoretical calculations and various physics-based models to obtain 0D-3D simulations, the authors demonstrated that the typical size range of cough and speech produces droplets (d ≤ 20 μm) that allow it to remain in the air for O (1h) that can be inhaled. According to the results of the numerical evidence, the fast drying process of even large droplets, up to sizes O (100 μm), in droplet/aerosols nuclei was provided. The authors indicated that the transport and dilution of aerosols (d ≤ 20 μm) at distances of more than 10 m in generic environments using 3D-scale resolution computational fluid dynamics simulations (Vuorinen et al., 2020). These authors emphasized that the two main issues are the physical distance and the minimum time spent in these indoor places, since due to strong breathing or loud speech, the high level of aerosol generated is anticipated. It was reported that by applying various common-sense actions, such as minimizing exposure time, maximizing physical distance, and improving ventilation, aerosol exposure could potentially be reduced with high expectations of reducing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus as well (Vuorinen et al., 2020). Finally, the concepts of “exposure time” to aerosols containing viruses were introduced to complement the traditional thinking of “safe distance” and the authors confirmed that the exposure time for inhaling 100 aerosols could range from 1 s to 1 min or even to 1 h depending on the situation. Therefore, using Monte-Carlo simulations, the authors presented clear quantitative information on exposure time in different indoor public settings (Vuorinen et al., 2020). As can be seen from the simulation studies, the authors investigated the various aspects of exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in indoor environments.

However, each of the included studies had limitations and assumptions, they showed that the emission of the SARS-CoV-2 virus (accompanied by other types of bioaerosols) by symptomatic or even asymptomatic people in the indoor air environment is inevitable. Considering the results of the study by van Doremalen et al. (2020) experimentally indicated that the SARS-CoV-2 virus in aerosols generated with diameters <5 μm can survive and be viable and infectious in aerosols for hours (generally 3 h). On the other hand, environmental factors such as temperature and relative humidity (RH) were shown to affect the airborne transmission of small viral particles, including SARS-CoV-2 (Ahlawat et al., 2020). It was highlighted that the probability of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is higher in dry indoor environments (RH less than 40%) than in humid environments (RH more than 90%) (Ahlawat et al., 2020).

Taking into account the results of the included studies, as well as other published studies, there is a great possibility of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor environments. Therefore, since more than 80–90% of the time people spend indoors, especially in confined conditions, to reduce exposure and risk of COVID-19 disease, the following procedures are offered to experts in indoor air quality (IAQ) and related engineers to improve indoor air environments:

-

1)

Provide ventilation systems, especially displacement ventilation in all indoor environments: In displacement ventilation, the outside air is usually supplied at low speed from diffusers near floor level and is extracted above the occupied zone, near or on the ceiling (Blocken et al., 2020).

It is worth noting that due to the effect of outdoor air pollution on IAQ, it is suggested that air conditioning systems can use building/room ventilation, especially in highly polluted areas (Chirico et al., 2020; Harbizadeh et al., 2019). However, a recent review study applied a snowball strategy to investigate airborne transmission through air conditioning systems and reported that the spread of viral particles through air conditioning systems was suspected and supported by computer simulation (Chirico et al., 2020). Therefore, the application of air conditioning systems required more experimental studies to determine the exact role of air conditioning systems in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (Domínguez-Amarillo et al., 2020). On the other hand, in the recent SR of hospital air quality and the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, all the evidence on air filtration and recirculation was investigated and could be suitable documents for readers on this specific topic (Mousavi et al., 2020).

-

2)

Try redesigning and increasing the existing ventilation rate and efficiency. Also, upgrade ventilation systems with portable air cleaners or disinfectants (such as UV lamps or high-efficiency filtration systems) to remove all types of bioaerosols including SARS-CoV-2. It should be noted that the maintenance of ventilation systems, as well as filters or disinfectants in air purifiers, is of the utmost importance.

-

3)

Studies reported that SARS-CoV-2 concentrations in the air, especially in hospitals, could be higher during the first week of the rooms of confirmed COVID- 19 positive patients. Therefore, more prevention and control policies should be applied to reduce the concentration of SARS-CoV-2 in the air and subsequently the exposure of more people to viral particles. One of the most important strategies is to isolate the COVID-19 patient with high viral loads in the exhaled air in the first weeks of infection.

-

4)

To minimize airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2, it is very important to establish a minimum RH standard for indoor environments, including hospital wards, confirmed COVID-19 positive patients rooms, offices, and public transports (Ahlawat et al., 2020).

-

5)

To avoid exposure to the virus, observe an interpersonal distance of more than 2 m (also known as “droplet distance”) as effective protection only if everyone wears face masks (Setti et al., 2020). However, the WHO stated that the safe distance is 1 m as a sufficient distance to avoid transmission of the virus by air (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019). Unlike the WHO-reported safe distance of 1 m for interpersonal distance or droplet distance, recently a study of mathematical models demonstrated that short-range airborne transmission dominates exposure to viral particles in close contact (less than 2 m) (Chen et al., 2020).

-

6)

To observe social distance and avoid overcrowding, in restaurants, customers sit at alternate tables, students sit in any other disc in the school classroom, or in any other seat on public transportation, etc.

5. Conclusions

There is a controversial debate about the routes of transmission of COVID-19 in this pandemic situation. Currently, due to incomplete evidence of airborne transmission of COVID-19, investigation of the possibility of airborne transmission is of utmost importance. Therefore, in the present study, a total of fourteen relevant and eligible studies were collected. According to the findings of the reviewed studies, there is an important and strong possibility of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor air environments. Based on these results, it is necessary to take into account some procedures to improve indoor air environments: such as improving the ventilation of buildings or rooms, especially in hospitals and crowded places, observing an interpersonal distance of more than 2 m, setting the minimum standard of RH, etc. Observing these recommendations associated with ventilation and other measures could be beneficial in reducing the general environmental concentrations of bioaerosols in the air and eventually reducing the spread of SARS-CoV-2 through the respiratory tract. Finally, it was recommended that along with other guidelines from the centers and official authorities, the search for cases, isolation and quarantine, hand washing, observation of social distancing and the use of materials to disinfect surfaces in crowded places be included. The airborne route of transmission is also considered to promote the protection of healthcare professionals, patients especially in hospitals, and the public in other public buildings.

Credit author contribution statement

Zahra Noorimotlagh: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision. Neemat Jaafarzadeh: Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Susana Silva Martinez: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Seyyed Abbas Mirzaee: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Project administration.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Ilam University of Medical Sciences, Ilam, Iran.

References

- Ahlawat A., Wiedensohler A., Mishra S.K. An overview on the role of relative humidity in airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in indoor environments. Aerosol and Air Quality Research. 2020;20:1856–1861. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2020.06.0302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amoatey P., Omidvarborna H., Baawain M.S., Al-Mamun A. Impact of building ventilation systems and habitual indoor incense burning on SARS-CoV-2 virus transmissions in Middle Eastern countries. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:139356. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansari M., Ahmadi Yousefabad S. Potential threats of COVID-19 on quarantined families. Publ. Health. 2020;183:1. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blocken B., Van Druenen T., Van Hooff T., Verstappen P., Marchal T., Marr L.C. Can Indoor Sports Centers Be Allowed to Re-open during the COVID-19 Pandemic Based on a Certificate of Equivalence? Building and Environment. 2020:107022. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno G., Stabile L., Morawska L. Estimation of airborne viral emission: quanta emission rate of SARS-CoV-2 for infection risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2020:105794. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraturo F., Del Giudice C., Morelli M., Cerullo V., Libralato G., Galdiero E., Guida M. Persistence of SARS-CoV-2 in the environment and COVID-19 transmission risk from environmental matrices and surfaces. Environ. Pollut. 2020;115010 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Zhang N., Wei J., Yen H.-L., Li Y. Short-range airborne route dominates exposure of respiratory infection during close contact. Build. Environ. 2020;176:106859. doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.106859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chia P.Y., Coleman K.K., Tan Y.K., Ong S.W.X., Gum M., Lau S.K., Lim X.F., Lim A.S., Sutjipto S., Lee P.H. Detection of air and surface contamination by SARS-CoV-2 in hospital rooms of infected patients. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16670-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico F., Sacco A., Bragazzi N.L., Magnavita N. Can air-conditioning systems contribute to the spread of SARS/MERS/COVID-19 infection? Insights from a rapid review of the literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:6052. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17176052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Correia G., Rodrigues L., Silva M., Gonçalves T. Airborne route and bad use of ventilation systems as non-negligible factors in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Med. Hypotheses. 2020:109781. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2020.109781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingo J.L., Marquès M., Rovira J. Influence of airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on COVID-19 pandemic. A review. Environ. Res. 2020;188:109861. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Amarillo S., Fernández-Agüera J., Cesteros-García S., González-Lezcano R.A. Bad air can also kill: residential indoor air quality and pollutant exposure risk during the COVID-19 crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:7183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faridi S., Niazi S., Sadeghi K., Naddafi K., Yavarian J., Shamsipour M., Jandaghi N.Z.S., Sadeghniiat K., Nabizadeh R., Yunesian M. A field indoor air measurement of SARS-CoV-2 in the patient rooms of the largest hospital in Iran. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:138401. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghinai I., Mcpherson T.D., Hunter J.C., Kirking H.L., Christiansen D., Joshi K., Rubin R., Morales-Estrada S., Black S.R., Pacilli M., Fricchione M.J., Chugh R.K., Walblay K.A., Ahmed N.S., Stoecker W.C., Hasan N.F., Burdsall D.P., Reese H.E., Wallace M., Wang C., Moeller D., Korpics J., Novosad S.A., Benowitz I., Jacobs M.W., Dasari V.S., Patel M.T., Kauerauf J., Charles E.M., Ezike N.O., Chu V., Midgley C.M., Rolfes M.A., Gerber S.I., Lu X., Lindstrom S., Verani J.R., Layden J.E., Brister S., Goldesberry K., Hoferka S., Jovanov D., Nims D., Saathoff-Huber L., Hoskin Snelling C., Adil H., Ali R., Andreychak E., Bemis K., Frias M., Quartey-Kumapley P., Baskerville K., Murphy E., Murskyj E., Noffsinger Z., Vercillo J., Elliott A., Onwuta U.S., Burck D., Abedi G., Burke R.M., Fagan R., Farrar J., Fry A.M., Hall A.J., Haynes A., Hoff C., Kamili S., Killerby M.E., Kim L., Kujawski S.A., Kuhar D.T., Lynch B., Malapati L., Marlow M., Murray J.R., Rha B., Sakthivel S.K.K., Smith-Jeffcoat S.E., Soda E., Wang L., Whitaker B.L., Uyeki T.M. First known person-to-person transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in the USA. Lancet. 2020;395:1137–1144. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30607-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbizadeh A., Mirzaee S.A., Khosravi A.D., Shoushtari F.S., Goodarzi H., Alavi N., Ankali K.A., Rad H.D., Maleki H., Goudarzi G. Indoor and outdoor airborne bacterial air quality in day-care centers (DCCs) in greater Ahvaz, Iran. Atmos. Environ. 2019;216:116927. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2019.116927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kenarkoohi A., Noorimotlagh Z., Falahi S., Amarloei A., Mirzaee S.A., Pakzad I., Bastani E. Hospital indoor air quality monitoring for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) virus. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:141324. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim U.J., Lee S.Y., Lee J.Y., Lee A., Kim S.E., Choi O.-J., Lee J.S., Kee S.-J., Jang H.-C. Air and environmental contamination caused by COVID-19 patients: a multi-center study. J. Kor. Med. Sci. 2020;35 doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. 2020. Is the Coronavirus Airborne? Experts Can't Agree Nature News. Retrieved 6 April 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Ning Z., Chen Y., Guo M., Liu Y., Gali N.K., Sun L., Duan Y., Cai J., Westerdahl D. Aerodynamic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in two Wuhan hospitals. Nature. 2020;582:557–560. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2271-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masoumbeigi H., Ghanizadeh G., Arfaei R.Y., Heydari S., Goodarzi H., Sari R.D., Tat M. Investigation of hospital indoor air quality for the presence of SARS-Cov-2. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s40201-020-00543-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L., Cao J. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2: the world should face the reality. Environ. Int. 2020;139:105730. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi E.S., Kananizadeh N., Martinello R.A., Sherman J.D. COVID-19 outbreak and hospital air quality: a systematic review of evidence on air filtration and recirculation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;11 doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c03247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorimotlagh Z., Karami C., Mirzaee S.A., Kaffashian M., Mami S., Azizi M. Immune and bioinformatics identification of T cell and B cell epitopes in the protein structure of SARS-CoV-2: a Systematic Review. Int. Immunopharm. 2020:106738. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorimotlagh Z., Mirzaee S.A., Martinez S.S., Rachoń D., Hoseinzadeh M., Jaafarzadeh N. Environmental exposure to nonylphenol and cancer progression Risk–A systematic review. Environ. Res. 2020:109263. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenes-Piñero E., Baño F., Navas-Carrillo D., Moreno-Docón A., Marín J.M., Misiego R., Ramírez P. Evidences of SARS-CoV-2 virus air transmission indoors using several untouched surfaces: a pilot study. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:142317. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organization W.H. 2020. Coronavirus Disease ( COVID-19): Situation Report; p. 182. [Google Scholar]

- Razzini K., Castrica M., Menchetti L., Maggi L., Negroni L., Orfeo N.V., Pizzoccheri A., Stocco M., Muttini S., Balzaretti C.M. SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection in the air and on surfaces in the COVID-19 ward of a hospital in Milan, Italy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140540. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santarpia J.L., Rivera D.N., Herrera V., Morwitzer M.J., Creager H., Santarpia G.W., Crown K.K., Brett-Major D., Schnaubelt E., Broadhurst M.J. Aerosol and Surface Transmission Potential of SARS-CoV-2. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santarpia J.L., Rivera D.N., Herrera V., Morwitzer M.J., Creager H., Santarpia G.W., Crown K.K., Brett-Major D., Schnaubelt E., Broadhurst M.J. Transmission Potential of SARS-CoV-2 in Viral Shedding Observed at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.23.20039446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Setti L., Passarini F., De Gennaro G., Barbieri P., Perrone M.G., Borelli M., Palmisani J., Di Gilio A., Piscitelli P., Miani A. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2020. Airborne Transmission Route of COVID-19: Why 2 Meters/6 Feet of Inter-personal Distance Could Not Be Enough. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadnytskyi V., Bax C.E., Bax A., Anfinrud P. The airborne lifetime of small speech droplets and their potential importance in SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. Unit. States Am. 2020;117:11875–11877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006874117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doremalen, Neeltje, Trenton Bushmaker, DylanMorris H, MyndiHolbrook G, Amandine Gamble, BrandiWilliamson N, Azaibi Tamin Aerosol and Surface Stability of Sars-Cov-2 as Compared with Sars-Cov-1. New England J. Med. 2020;382(16) doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. 1564–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuorinen V., Aarnio M., Alava M., Alopaeus V., Atanasova N., Auvinen M., Balasubramanian N., Bordbar H., Erästö P., Grande R. Modelling aerosol transport and virus exposure with numerical simulations in relation to SARS-CoV-2 transmission by inhalation indoors. Saf. Sci. 2020:104866. doi: 10.1016/j.ssci.2020.104866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Yoneda M. Determination of the optimal penetration factor for evaluating the invasion process of aerosols from a confined source space to an uncontaminated area. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:140113. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]