Abstract

This mendelian randomization analyzes the potential causality between physical activity and schizophrenia.

Substantial evidence indicates that physical activity (PA) improves symptoms, cognitive function, and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia.1 Some studies suggest a protective effect of PA against schizophrenia/psychosis risk itself, although current evidence is inconclusive.2 Here, using mendelian randomization (MR) and its multivariable extension (MVMR), we have examined the association between PA (exposure) and schizophrenia risk (outcome). Likewise, we have investigated the potential pleiotropic role of body mass index (BMI), a common confounder in studies involving PA, in this interplay.

Methods

Instrumental variables (IVs) for the main exposures in our study were extracted from summary data of UK Biobank genome-wide–association study (GWAS) on accelerometer-based PA (minimum n = 90 667; maximum n = 91 105) and self-reported PA (minimum n = 261 055; maximum n = 377 234).3,4 For these GWAS, summary statistics with and without BMI correction were obtained (see the Table for a list of PA phenotypes). Likewise, IVs for schizophrenia (40 675 cases and 64 643 controls) and BMI (n = 339 224) were extracted from their respective GWAS.5,6 Whenever possible, exposure IVs were selected among genome-wide associated variants. All original GWAS investigations were conducted with ethics committee approval. The UK Biobank studies received approval from the National Health Service National Research Ethics Service. Written informed consent was obtained from participants.

Table. Results of Univariate/Multivariable MR Analyses and Sensitivity Analyses.

| Exposure | P value IVs selection in GWAS | MR method | MR univariate analyses | MR multivariable analyses, physical activity and BMI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No BMI correction | Physical activity GWAS corrected for BMI | ||||||||||||||

| No. of IVs | MR P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Heterog Q P value | MR Egger int P value | No. of IVs | MR P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | Heterog Q P value | MR Egger int P value | No. of IVs | MR P value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | |||

| Overall activity | 1×10−7 | IVW | 7 | .04 | 1.51 (1.02-2.23) | .10 | .06 | 3 | .69 | 0.87 (0.45-1.71) | .12 | .30 | 4 | .43 | 1.18 (0.79-1.76) |

| MR Egger | .03 | 6.39 (1.91-21.38) | NA | .33 | 7.10 (0.82-61.55) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .32 | 1.23 (0.82-1.86) | NA | .63 | 0.86 (0.46-1.61) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Moderate activity | 1×10−6 | IVW | 7 | .69 | 0.93 (0.65-1.32) | .33 | .58 | 9 | .21 | 0.83 (0.61-1.12) | .60 | .73 | 4 | .97 | 1.01 (0.65-1.55) |

| MR Egger | .52 | 0.67 (0.22-2.09) | NA | .94 | 0.97 (0.38-2.44) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .69 | 0.91 (0.57-1.45) | NA | .12 | 0.72 (0.48-1.09) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Average acceleration | 5×10−8 | IVW | 6 | .42 | 1.02 (0.97-1.08) | .08 | .57 | 5 | .30 | 0.97 (0.91-1.03) | .12 | .63 | 4 | .68 | 1.01 (0.96-1.06) |

| MR Egger | .70 | 0.95 (0.76-1.20) | NA | .82 | 1.03 (0.81-1.32) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .52 | 1.01 (0.97-1.07) | NA | .06 | 0.94 (0.89-1.00) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Fraction accelerations >425 mg | 5×10−8 | IVW | 6 | .10 | 1.33 (0.95-1.88) | .67 | .26 | 5 | .82 | 1.04 (0.67-1.60) | .34 | .54 | 5 | .96 | 0.99 (0.64-1.53) |

| MR Egger | .29 | 0.02 (0-8.64) | NA | .55 | 0.11 (0-67.69) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .09 | 1.44 (0.94-2.20) | NA | .76 | 0.91 (0.52-1.62) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Strenuous sports/exercises | 5×10−8 | IVW | 7 | .12 | 2.85 (0.77-10.58) | .12 | .06 | 5 | .54 | 0.61 (0.13-2.93) | .07 | .68 | 7 | .60 | 1.78 (0.55-5.72) |

| MR Egger | .11 | 0.01 (0-1.14) | NA | .77 | 3.75 (0-12 504.89) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .17 | 2.80 (0.66-12.05) | NA | .46 | 0.58 (0.14-2.45) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Vigorous activity | 1×10−7 | IVW | 9 | .02 | 3.20 (1.19-8.57) | .14 | .36 | 12 | .03 | 2.67 (1.12-6.35) | .13 | .85 | 4 | .03 | 3.50 (1.11-11.04) |

| MR Egger | .71 | 0.46 (0.01-24.60) | NA | .73 | 1.91 (0.06-64.44) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .05 | 3.28 (1.02-10.51) | NA | .01 | 3.55 (1.31-9.57) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Moderate to vigorous activity | 5×10−8 | IVW | 13 | .004a | 1.96 (1.24-3.11) | .21 | .09 | 10 | .002a | 2.67 (1.41-5.02) | .10 | .41 | 10 | .02 | 1.92 (1.10-3.35) |

| MR Egger | .04 | 29.05 (1.56-539.9) | NA | .23 | 20.28 (0.21-2006.8) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

| Weighted median | .02 | 1.98 (1.11-3.52) | NA | .004a | 2.81 (1.40-5.63) | NA | NA | NA | |||||||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; Egger int, Egger intercept; GWAS, genome-wise association study; IVs, instrumental variables; IVW, inverse variance weighted; MR, mendelian randomization; NA, not applicable.

Significant after Bonferroni correction for the 7 physical activity traits.

TwoSampleMR (https://github.com/MRCIEU/TwoSampleMR) was used to generate a list of linkage disequilibrium–independent IVs for each PA exposure and extract them from schizophrenia risk (outcome). LDlinkR (https://github.com/CBIIT/LDlinkR/) was implemented to find proxies with an r2 greater than 0.80 for those IVs not available in the outcome. Exposure and outcome data were harmonized. Horizontal pleiotropy was evaluated using MR-PRESSO (https://github.com/rondolab/MR-PRESSO), leading to removal of outlier IVs. The MR main analyses and sensitivity analyses were run using TwoSampleMR. The MVMR analyses, where 1 exposure (BMI) potentially mediates the association between the exposure of primary interest (PA) and the outcome (schizophrenia risk), were run in a similar fashion.

Results

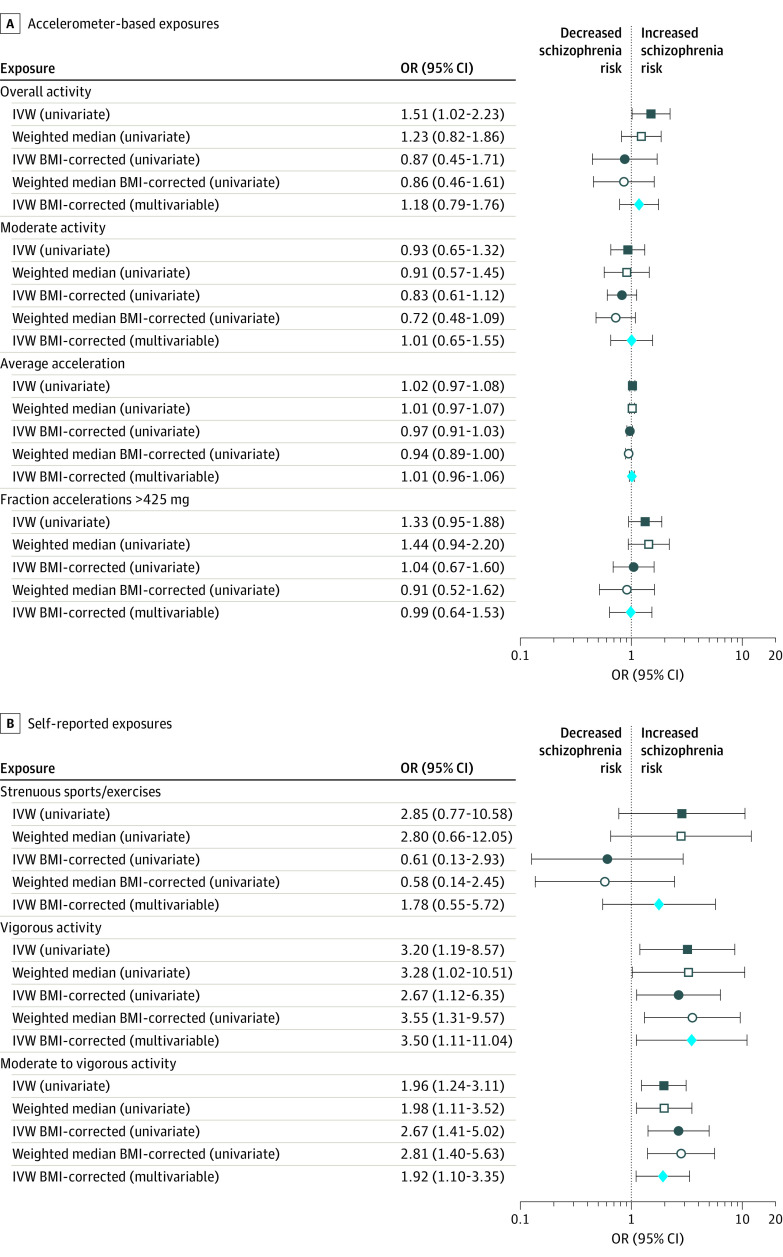

No association between PA and schizophrenia risk was observed in any of our analyses (Figure and Table). Univariate analysis with and without BMI correction provided evidence of the association of self-reported moderate/vigorous PA with increased schizophrenia risk (inverse variance–weighted and weighted median P <.05). Similar results were obtained with MVMR using BMI as covariate. Overall activity showed a similar trend in the univariate analysis, but the association was no longer significant after BMI correction.

Figure. Forest Plots of the Association of Physical Activity With Schizophrenia.

Inverse variance weighted (IVW) and median weighted effect estimates for the association between physical activity phenotypes and schizophrenia risk using mendelian randomization (MR). Estimates of univariate MR with and without body mass index (BMI) correction and multivariable MR are shown. OR indicates odds ratio.

Sensitivity analyses suggested that horizontal pleiotropy (Egger intercept P value >.05), heterogeneity (Cochran Q P >.05), or individual SNP effects (leave-one-out analyses, data not shown) were not likely to confound the results obtained for moderate/vigorous PA.

Discussion

Our results suggest that PA might not have preventive effects for schizophrenia. On the contrary, moderate/vigorous self-reported PA seems to increase schizophrenia risk, results that are difficult to align with current evidence.1 Interestingly, the most beneficial effects of PA in clinical studies are found on negative symptoms, especially cognitive dysfunction, and to a lesser extent on positive symptoms, although this is still an active area of research.1 Because positive symptoms usually drive the diagnosis of samples included in schizophrenia GWAS, we hypothesize that we are (1) missing the association of PA with the cognitive/negative symptom domain, and (2) capturing a factor closely related to intense physical exercise (perhaps stress-related or personality traits) that worsens the symptomatology of psychosis. In addition, we identified BMI as a relatively modest confounder in our analyses, probably due to the properties of MR analysis.

The potential causal associations we report, or lack thereof, should be interpreted with caution given the limitations of MR and the limited number of valid IVs that can be extracted from current PA GWAS. The potential implications of our results for disease prevention policies warrant the validation of these findings in well-powered cohort studies.

References

- 1.Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, et al. EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: a meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Eur Psychiatry. 2018;54:124-144. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brokmeier LL, Firth J, Vancampfort D, et al. Does physical activity reduce the risk of psychosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112675. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.112675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klimentidis YC, Raichlen DA, Bea J, et al. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int J Obes. 2018;42(6):1161-1176. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0120-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Doherty A, Smith-Byrne K, Ferreira T, et al. GWAS identifies 14 loci for device-measured physical activity and sleep duration. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5257. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07743-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Locke AE, Kahali B, Berndt SI, et al. ; LifeLines Cohort Study; ADIPOGen Consortium; AGEN-BMI Working Group; CARDIOGRAMplusC4D Consortium; CKDGen Consortium; GLGC; ICBP; MAGIC Investigators; MuTHER Consortium; MIGen Consortium; PAGE Consortium; ReproGen Consortium; GENIE Consortium; International Endogene Consortium . Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology. Nature. 2015;518(7538):197-206. doi: 10.1038/nature14177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pardiñas AF, Holmans P, Pocklington AJ, et al. ; GERAD1 Consortium; CRESTAR Consortium . Common schizophrenia alleles are enriched in mutation-intolerant genes and in regions under strong background selection. Nat Genet. 2018;50(3):381-389. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0059-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]