Key Points

Question

Is weight loss equivalence and improvement of quality of life similar at 7 years after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in patients with morbid obesity?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial of 240 patients with morbid obesity, the 7-year mean percentage excess weight loss was 47% after LSG vs 55% after LRYGB, a difference that did not meet prespecified criteria for equivalence; greater weight loss was associated with better quality of life. Disease-specific quality of life and general quality of life were similar.

Meaning

Weight loss was not equivalent between LSG and LRYGB because somewhat greater weight loss was achieved after LRYGB; quality of life improvement was similar after both procedures.

Abstract

Importance

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is currently the predominant bariatric procedure, although long-term weight loss and quality-of-life (QoL) outcomes compared with laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are lacking.

Objective

To determine weight loss equivalence of LSG and LRYGB at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity, with special reference to long-term QoL.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The SLEEVE vs byPASS (SLEEVEPASS) multicenter, multisurgeon, open-label, randomized clinical equivalence trial was conducted between March 10, 2008, and June 2, 2010, in Finland. The trial enrolled 240 patients with morbid obesity aged 18 to 60 years who were randomized to undergo either LSG or LRYGB with a 7-year follow-up (last follow-up, September 26, 2017). Analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. Statistical analysis was performed from June 4, 2018, to November 8, 2019.

Interventions

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (n = 121) or LRYGB (n = 119).

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary end point was percentage excess weight loss (%EWL) at 5 years. Secondary predefined follow-up time points were 7, 10, 15, and 20 years, with included 7-year secondary end points of QoL and morbidity. Disease-specific QoL (DSQoL; Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life questionnaire [range of scores, –3 to 3 points, where a higher score indicates better QoL]) and general health-related QoL (HRQoL; 15D questionnaire [0-1 scale for all 15 dimensions, with 1 indicating full health and 0 indicating death]) were measured preoperatively and at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years postoperatively concurrently with weight loss.

Results

Of 240 patients (167 women [69.6%]; mean [SD] age, 48.4 [9.4] years; mean [SD] baseline body mass index, 45.9 [6.0]), 182 (75.8%) completed the 7-year follow-up. The mean %EWL was 47% (95% CI, 43%-50%) after LSG and 55% (95% CI, 52%-59%) after LRYGB (difference, 8.7 percentage units [95% CI, 3.5-13.9 percentage units]). The mean (SD) DSQoL total score at 7 years was 0.50 (1.14) after LSG and 0.49 (1.06) after LRYGB (P = .63), and the median HRQoL total score was 0.88 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.78-0.95) after LSG and 0.87 (IQR, 0.78-0.95) after LRYGB (P = .37). Greater weight loss was associated with better DSQoL (r = 0.26; P < .001). At 7 years, mean (SD) DSQoL scores improved significantly compared with baseline (LSG, 0.50 [1.14] vs 0.10 [0.94]; and LRYGB, 0.49 [1.06] vs 0.12 [1.12]; P < .001), unlike median HRQoL scores (LSG, 0.88 [IQR, 0.78-0.95] vs 0.87 [IQR, 0.78-0.90]; and LRYGB, 0.87 [IQR, 0.78-0.92] vs 0.85 [IQR, 0.77-0.91]; P = .07). The overall morbidity rate was 24.0% (29 of 121) for LSG and 28.6% (34 of 119) for LRYGB (P = .42).

Conclusions and Relevance

This study found that LSG and LRYGB were not equivalent in %EWL at 7 years. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass resulted in greater weight loss than LSG, but the difference was not clinically relevant based on the prespecified equivalence margins. There was no difference in long-term QoL between the procedures. Bariatric surgery was associated with significant long-term DSQoL improvement, and greater weight loss was associated with better DSQoL.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00793143

This randomized clinical trial compares weight loss equivalence of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at 7 years in patients with morbid obesity, with special reference to long-term quality of life.

Introduction

The obesity epidemic is still increasing worldwide.1,2,3 Bariatric surgery is currently the only effective treatment for morbid obesity that results in substantial and sustainable weight loss, remission of obesity-related comorbidities, and improvement of quality of life (QoL) in the long term.4,5,6,7 The annual number of bariatric procedures performed worldwide is currently approximately 700 000. The 2 most common bariatric procedures are laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has been the most frequently performed bariatric procedure since 2014 and is still showing a steady annual increase both in number and proportion of all bariatric surgical procedures.8 This shift in global preference for LSG vs LRYGB happened before adequate long-term data for LSG were available.9

The SLEEVE vs byPASS (SLEEVEPASS) multicenter, multisurgeon, open-label, randomized clinical trial (RCT) was designed to compare the equivalence of LSG vs LRYGB on weight loss with the primary end point of 5-year percentage excess weight loss (%EWL).10 At 5 years, the 2 procedures did not meet the criteria for equivalence in terms of %EWL, but the difference between the procedures was not statistically significant owing to the prespecified equivalence margins. At 5 years, there was no difference in type 2 diabetes or dyslipidemia remission, QoL improvement, or morbidity. Hypertension remission was superior after LRYGB.

Besides weight loss and remission of comorbidities, QoL is a major outcome measure in bariatric surgery. Patients with morbid obesity are shown to have lower QoL compared with the general population11,12 and bariatric surgery is associated with improved QoL.13,14,15 At 5-year follow-up of the 2 largest RCTs, there was no difference in improvement of disease-specific QoL (DSQoL) between LSG and LRYGB.10,16 However, these 5-year outcomes are lacking more detailed long-term QoL assessments covering both general health-related QoL (HRQoL) and DSQoL, including the durability and association of QoL improvement with weight loss.

This article reports the 7-year follow-up of the SLEEVEPASS RCT focusing on %EWL with a special reference to long-term QoL assessing DSQoL dimensions, improvement from baseline, HRQoL comparison with the general population, and the effect of weight loss outcomes on long-term QoL.

Methods

Trial Design, Participants, Randomization, and Interventions

The study design, preoperative evaluations, and surgical techniques have been previously reported.10,17,18 The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethics committees of all study hospitals, and all patients gave written informed consent (trial protocol in Supplement 1).

In brief, the SLEEVEPASS study was a multicenter, multisurgeon, open-label, randomized clinical equivalence trial conducted between March 10, 2008, and June 2, 2010, at 3 hospitals in Finland (Turku, Vaasa, and Helsinki). A total of 240 patients with morbid obesity were randomized to undergo either LSG or LRYGB. Randomization was performed with 1:1 equal allocation ratio using a closed-envelope method. All of the treating surgeons were part of the study team. Eligibility criteria included body mass index (BMI; calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) greater than 40 or greater than 35 with a significant obesity-associated comorbidity, age 18 to 60 years, and a previous failed adequate conservative treatment. Exclusion criteria were BMI greater than 60, significant eating or psychiatric disorder, active alcohol or substance abuse, active gastric ulcer disease, severe gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with a large hiatal hernia, and previous bariatric surgery.

Objective

The objective of this 7-year secondary analysis was to assess %EWL equivalence after LSG and LRYGB in patients with morbid obesity. In addition, QoL outcomes were compared between procedures and with those of an age-standardized and sex-standardized general population, and long-term QoL association with weight loss outcomes was determined.

Outcome Measures

The primary end point of the SLEEVEPASS study was weight loss at 5 years defined by %EWL (initial weight − follow-up weight)/(initial weight − ideal weight for BMI of 25) × 100%.19 The predefined secondary end points included QoL, remission of obesity-related comorbidities, and overall morbidity and mortality. Remission of obesity-related comorbidities was reported at the 5-year follow-up; these data are not reported at 7 years, with next follow-up scheduled at 10 years. In this 7-year follow-up study focusing on weight loss and QoL, the %EWL and the improvement of DSQoL and HRQoL were assessed preoperatively and at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years after surgery. Postoperative complications were classified as major or minor20 and according to the Clavien-Dindo classification.21 All additional complications between 5 and 7 years after surgery were assessed and added to previously reported 5-year complications.10

The Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life questionnaire of the Bariatric Analysis and Reporting Outcome System was used for DSQoL assessment. It is a 1-page analysis addressing self-esteem (score range, −1 to 1) and 4 daily activities (physical activity, social life, work conditions, and sexual activity [score range, −0.5 to 0.5 for each activity]) with the total score ranging from −3 to 3 points and a higher score indicating better QoL.22 The generic, comprehensive, standardized, and self-administered 15-dimensional (15D) questionnaire, which can be used both as a profile and a single index score measure, was used for HRQoL assessment. The 15 dimensions include: breathing, mental function, speech (communication), vision, mobility, usual activities, vitality, hearing, eating, elimination, sleeping, distress, discomfort and symptoms, sexual activity, and depression.23 There is a 0 to 1 scale for all dimensions (profile score) and an additive aggregation formula for all dimensions (single index score), with 1 indicating full health and 0 indicating death. A change of more than 0.015, on average, results in people feeling a difference that indicates clinical importance.24 The validity, sensitivity, reliability, responsiveness to change, and discriminatory power of the 15D questionnaire has been well tested in the Finnish population,23 with available data on HRQoL of the Finnish general population25 enabling the age-standardized and sex-standardized general population comparison.

Long-term Follow-up

The patients were followed-up at 30 days,17 6 months,18 and 1, 2, 3, 5,10 (primary end point assessment), and 7 years. The follow-up plan extends up to 20 years, with follow-up time points of 10, 15, and 20 years. At the follow-up visits, the patients underwent clinical examination and laboratory tests, and they filled out the questionnaires. The last follow-up date for this 7-year report was September 26, 2017. Patients lost to follow-up were contacted several times by telephone.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis. Statistical analysis was performed from June 4, 2018, to November 8, 2019. Study sample size calculations have been previously reported.10 Continuous variables are summarized with mean (SD) values and categorical variables with numbers and percentages. Pearson correlation was calculated between %EWL and DSQoL. Comparison of %EWL between LSG and LRYGB at 7 years was estimated within linear mixed models for the repeated-measures model. In this model, baseline %EWL, operation type (LRYGB or LSG), time (within factor), and their interaction were included as well as diabetes and study site as between factors. Model-based estimates and their 95% CIs were calculated to evaluate the predefined margins for equivalence. Tukey corrections were used in pairwise comparisons. Assumptions for the model were checked with studentized residuals.

Similarly, comparisons for DSQoL at 7 years were estimated within linear mixed models suitable for repeated measures (PROC MIXED in SAS software, version 9.4 for Windows; SAS Institute Inc). In the model, intervention, time, and their interaction were included. Study site was handled as a random factor. An unstructured covariance structure was used; otherwise, the same details as in %EWL analyses were followed. The Moorehead-Ardelt QoL score dimensions were compared between interventions separately for each time point using the Fisher exact test. Similarly, the number of patients with complications was compared between interventions with the χ2 test.

We excluded the 15D responses where more than 3 dimensions were left blank. Other possible missing 15D values were estimated using a regression analysis according to Sintonen.23 If 2 or more alternatives were reported for a single dimension, the worst value chosen was included in the analysis. The 15D score was calculated for each respondent individually and the mean 15D scores were calculated for each time point for both intervention groups. Furthermore, the mean 15D profiles were drawn for all groups. All the estimates were calculated separately for baseline, at 6 months, and at 1, 3, 5, and 7 years. The 15D results were compared with age-standardized and sex-standardized general population values. Population values were drawn from a national survey (the Health 2011 survey) on changes in the health status, functional capacity, and welfare of the population.25 Differences between the groups in median 15D scores were compared with the control group using a Mann-Whitney test. Differences in 15D scores between time points were compared using an independent samples t test.

The 15D statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14 (StataCorp). Other statistical reporting was performed using SAS software, version 9.4 for Windows. A 2-tailed P < .05 was considered statistically significant and 95% CIs were calculated for proportions.

Results

Trial Patients

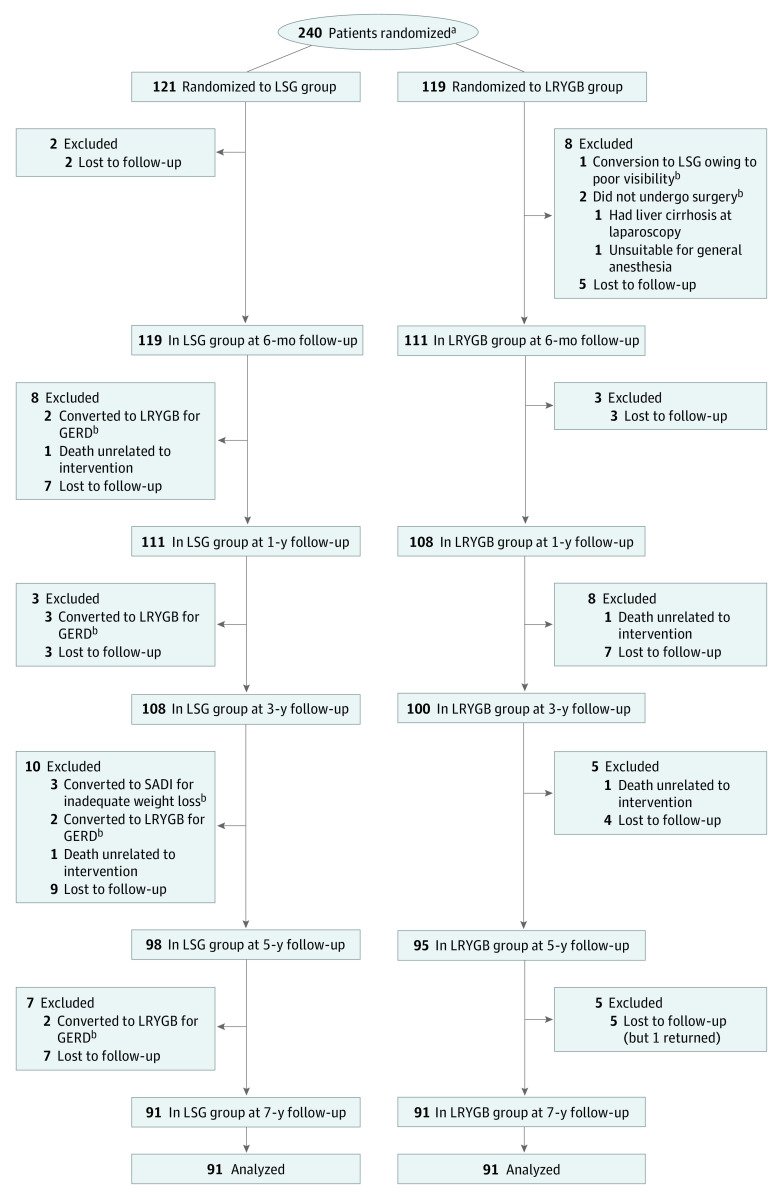

The flow of participants is shown in Figure 1. The patient baseline characteristics are reported in Table 1. Of the initial 240 patients (167 women [69.6%]; mean [SD] age, 48.4 [9.4] years; mean [SD] baseline BMI, 45.9 [6.0]), 121 were randomized to undergo LSG (87 women [71.9%]; mean [SD] age, 48.5 [9.6] years; mean [SD] baseline BMI, 45.5 [6.2]) and 119 to undergo LRYGB (80 women [67.2%]; mean [SD] age, 48.4 [9.3] years; mean [SD] baseline BMI, 46.4 [5.9]). At 7 years, 182 patients (75.8%) were available for follow-up; 91 (75.2%) in the LSG group and 91 (76.5%) in the LRYGB group.

Figure 1. Study Flowchart.

GERD indicates gastroesophageal reflux disease; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; LSG, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; and SADI, single anastomosis duodenoileal bypass.

aThe number of patients assessed for eligibility was not adequately recorded.

bAnalyzed according to intention to treat.

Table 1. Patient Baseline Characteristics.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| LSG (n = 121) | LRYGB (n = 119) | |

| Female | 87 (71.9) | 80 (67.2) |

| Male | 34 (28.1) | 39 (32.8) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 48.5 (9.6) | 48.4 (9.3) |

| Weight, mean (SD), kg | 130.1 (21.5) | 134.9 (22.5) |

| Baseline BMI, mean (SD) | 45.5 (6.2) | 46.4 (5.9) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 52 (43.0) | 49 (41.2) |

| Hypertension | 83 (68.6) | 87 (73.1) |

| Dyslipidemia | 39 (32.2) | 45 (37.8) |

| Moorehead-Ardelt QoL total score, mean (SD)a | 0.10 (0.94) | 0.12 (1.12) |

| Hospitals participating in the study, No. | ||

| Turku | 40 | 40 |

| Vaasa | 40 | 40 |

| Helsinki | 41 | 39 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); LSG, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; QoL, quality-of-life.

Score range, −3 to 3, with higher score indicating better QoL.

Weight Loss

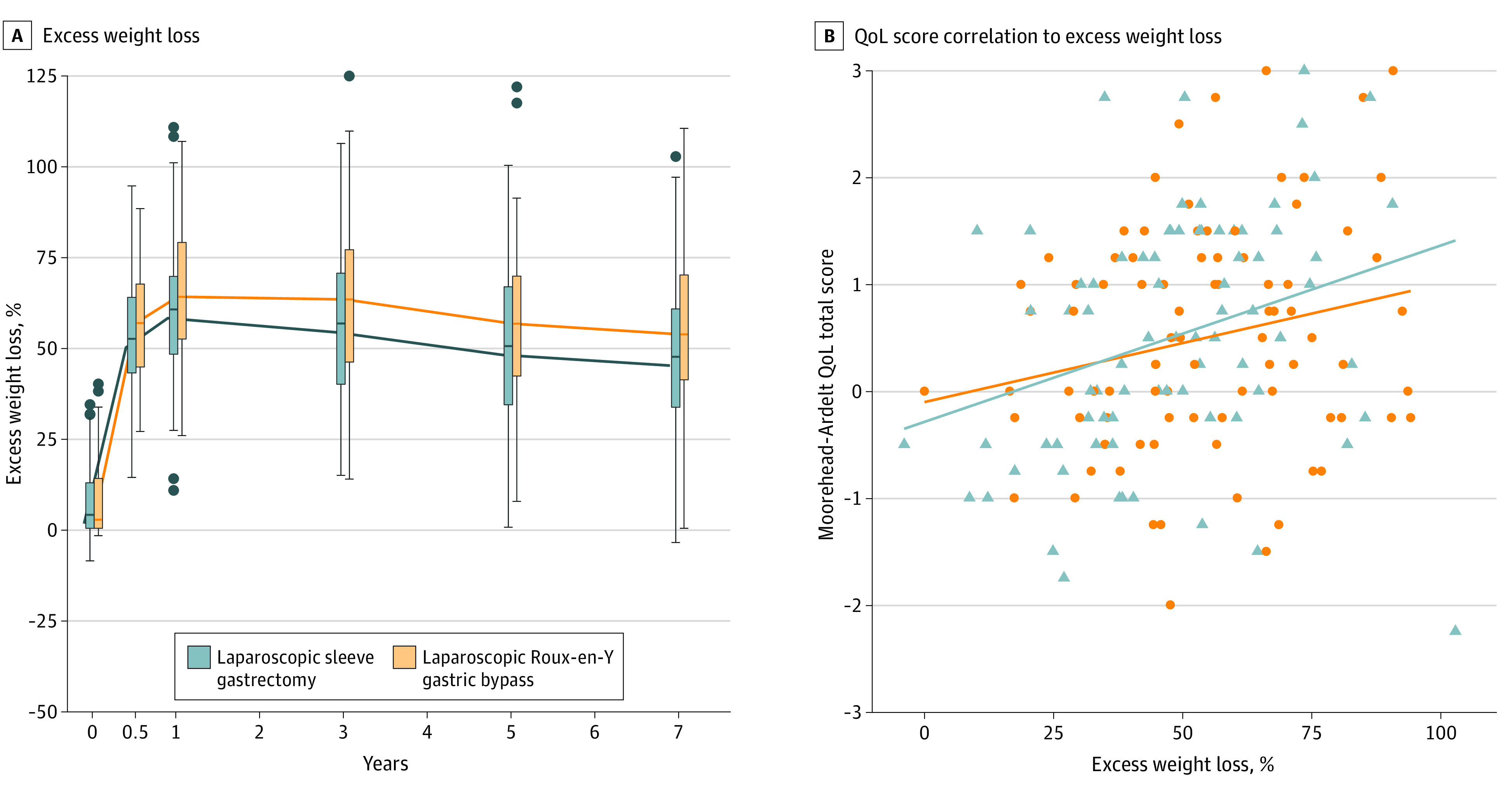

At 7 years, the estimated mean %EWL was 47% (95% CI, 43%-50%) in the LSG group and 55% (95% CI, 52%-59%) in the LRYGB group. The model-based estimate of mean %EWL was 8.7 percentage units (95% CI, 3.5-13.9 percentage units) higher after LRYGB than after LSG. Based on the predefined margins for equivalence (−9 to 9), the 2 groups were not equivalent at 7 years as the whole confidence interval is not within the margins. Although weight loss after LRYGB was statistically greater compared with LSG, the difference was not clinically relevant with respect to the predefined 95% CIs and equivalence margins. The %EWL at each follow-up point for both procedures is shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2. Excess Weight Loss and Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life (QoL) Total Score Correlation to Excess Weight Loss.

A, Excess weight loss at each follow-up point. B, Moorehead-Ardelt QoL total score correlation to excess weight loss.

Disease-Specific QoL

At baseline, the mean (SD) DSQoL (Moorehead-Ardelt QoL26) total score was 0.10 (0.94) after LSG (n = 117) and 0.12 (1.12) after LRYGB (n = 118) (Table 1). At 7 years, the mean (SD) DSQoL total score was 0.50 (1.14) after LSG and 0.49 (1.06) after LRYGB, with no statistically significant difference in between the 2 groups (P = .63). The mean (SD) DSQoL total scores were 1.20 (1.08) for LSG and 1.32 (1.05) for LRYGB at 1 year; 0.91 (1.17) for LSG and 1.13 (1.13) for LRYGB at 3 years; and 0.85 (1.08) for LSG and 0.76 (1.01) for LRYGB at 5 years. In both groups, the mean (SD) DSQoL score was significantly better at 7 years compared with baseline (LSG, 0.50 [1.14] vs 0.10 [0.94]; and LRYGB, 0.49 [1.06] vs 0.12 [1.12]; P < .001). There were no significant differences in any of the Moorehead-Ardelt QoL dimensions between the 2 procedures at 7 years (Table 2). Percentage excess weight loss was associated with the DSQoL score; greater weight loss resulted in superior DSQoL (r = 0.26; P < .001) (Figure 2B).

Table 2. Moorehead-Ardelt QoL Scores at Baseline and at 7 Years.

| Component | Patients, No./total No. (%) | P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Fair | Good | Very good | Excellent | ||

| At baseline | ||||||

| Self-esteema | ||||||

| LSG | 0/117 (0) | 23/117 (19.7) | 50/117 (42.7) | 42/117 (35.9) | 2/117 (1.7) | .46 |

| LRYGB | 1/118 (0.8) | 21/118 (17.8) | 54/118 (45.8) | 36/118 (30.5) | 6/118 (5.1) | |

| Socialb | ||||||

| LSG | 1/117 (0.9) | 5/117 (4.3) | 28/117 (23.9) | 45/117 (38.5) | 38/117 (32.5) | .73 |

| LRYGB | 0/118 (0) | 5/118 (4.2) | 33/118 (28.0) | 49/118 (41.5) | 31/118 (26.3) | |

| Physicalc | ||||||

| LSG | 26/117 (22.2) | 55/117 (47.0) | 24/117 (20.5) | 11/117 (9.4) | 1/117 (0.9) | .59 |

| LRYGB | 25/118 (21.2) | 49/118 (41.5) | 34/118 (28.8) | 8/118 (6.8) | 2/118 (1.7) | |

| Labord | ||||||

| LSG | 10/117 (8.6) | 36/117 (30.8) | 37/117 (31.6) | 31/117 (26.5) | 3/117 (2.6) | .59 |

| LRYGB | 13/118 (11.0) | 27/118 (22.9) | 37/118 (31.4) | 35/118 (29.7) | 6/118 (5.1) | |

| Sexuale | ||||||

| LSG | 7/117 (6.0) | 37/117 (31.6) | 34/117 (29.1) | 29/117 (24.8) | 10/117 (8.6) | .92 |

| LRYGB | 9/118 (7.6) | 35/118 (29.7) | 36/118 (30.5) | 31/118 (26.3) | 7/118 (5.9) | |

| At 7 y | ||||||

| Self-esteema | ||||||

| LSG | 1/83 (1.2) | 11/83 (13.3) | 35/83 (42.2) | 29/83 (34.9) | 7/83 (8.4) | .91 |

| LRYGB | 1/88 (1.1) | 9/88 (10.2) | 36/88 (40.9) | 36/88 (40.9) | 6/88 (6.8) | |

| Socialb | ||||||

| LSG | 0/83 (0) | 2/83 (2.4) | 19/83 (22.9) | 35/83 (42.2) | 27/83 (32.5) | .53 |

| LRYGB | 0/88 (0) | 1/88 (1.1) | 16/88 (18.2) | 47/88 (53.4) | 24/88 (27.3) | |

| Physicalc | ||||||

| LSG | 10/83 (12.1) | 21/83 (25.3) | 26/83 (31.3) | 22/83 (26.5) | 4/83 (4.8) | .98 |

| LRYGB | 10/88 (11.4) | 24/88 (27.3) | 30/88 (34.1) | 20/88 (22.7) | 4/88 (4.6) | |

| Labord | ||||||

| LSG | 4/83 (4.8) | 20/83 (24.1) | 22/83 (26.5) | 29/83 (34.9) | 8/83 (9.6) | .30 |

| LRYGB | 7/88 (8.0) | 15/88 (17.1) | 35/88 (39.8) | 25/88 (28.4) | 6/88 (6.8) | |

| Sexuale | ||||||

| LSG | 7/81 (8.6) | 23/81 (28.4) | 20/81 (24.7) | 24/81 (29.6) | 7/81 (8.6) | .14 |

| LRYGB | 6/87 (6.9) | 15/87 (17.2) | 34/87 (39.1) | 20/87 (23.0) | 12/87 (13.8) | |

Abbreviations: LSG, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; QoL, quality of life.

“Usually I feel…”

“I have satisfactory social contacts…”

“I enjoy physical activities…”

“I am able to work…”

“The pleasure I get out of sex is…”

Health-Related QoL

The median HRQoL (15D23) total score at baseline was 0.87 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.78-0.90) in the LSG group (n = 116) and 0.85 (IQR, 0.77-0.91) in the LRYGB group (n = 117). After 7 years, the median HRQoL total score was 0.88 (IQR, 0.78-0.95) in the LSG group (n = 83) and 0.87 (IQR, 0.78-0.92) in the LRYGB group (n = 88) (P = .37). The 15D total scores at each follow-up point are shown in the eFigure in Supplement 2. For the first 5 years after the procedures, HRQoL stayed higher compared with baseline, but decreased close to baseline at 7 years, with no significant difference in HRQoL compared with baseline (LSG, 0.88 [IQR, 0.78-0.95] vs 0.87 [IQR, 0.78-0.90]; and LRYGB, 0.87 [IQR, 0.78-0.92] vs 0.85 [IQR, 0.77-0.91]; P = .07).

The HRQoL of the trial patients was also compared with the HRQoL of the age-standardized and sex-standardized general Finnish population. At baseline, the mean (SD) HRQoL total score of all patients was 0.84 (0.10) and that of the general population was 0.93 (0.01). At 7 years, the mean (SD) HRQoL total score was 0.84 (0.12) for trial patients and 0.92 (0.01) for the general population. Both at baseline (P < .001) and at 7 years (P < .001), the HRQoL of the trial patients remained statistically significantly lower compared with the general population (eFigure in Supplement 2).

Morbidity and Mortality

The 30-day,17 6-month,18 and 5-year10 adverse events have been previously reported. At 7 years, the overall complication rate was 24.0% (n = 29) for LSG and 28.6% (n = 34) for LRYGB (P = .42). The late minor complication rate between 5 and 7 years for LSG was 5.0% (n = 6), and for LRYGB, it was 3.4% (n = 4) (P = .75). The late major complication rate was 0.8% for LSG (n = 1) and 2.5% (n = 3) for LRYGB (P = .37). All major complications were reoperations. All complications from 30 days until the 7-year follow-up are presented in detail in Table 3. No treatment-related mortality or mortality from other causes was reported between the 5-year and 7-year follow-up.

Table 3. Minor and Major Complications After LSG and LRYGB From 30 Days to 7 Years of Follow-up.

| Complication | Patients, No./total No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSG | LRYGB | ||

| Minor early (<30 d) complications | |||

| Bleeding | 3/121 (2.5) | 2/117 (1.7) | NA |

| Intra-abdominal infection/infection of unknown origin | 2 (1.7) | 8/117 (6.8) | NA |

| Pneumonia | 1/121 (0.8) | 6/117 (5.1) | NA |

| Superficial wound infection | 2/121 (1.7) | 3/117 (2.6) | NA |

| Trocar site pain | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Dehydration | 0 | 1/117 (0.9) | NA |

| Total | 9/121 (7.4) | 20/117 (17.1) | .02 |

| Major early (<30 d) complications | |||

| Bleeding | 3/121 (2.5) | 7/117 (6.0) | NA |

| Intra-abdominal infection/infection of unknown origin | 1/121 (0.8) | 3/117 (2.6) | NA |

| Pneumonia | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Bowel perforation | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Torsion of the enteroanastomosis | 0 | 1/117 (0.9) | NA |

| Outlet obstruction | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Total | 7/121 (5.8) | 11/117 (9.4) | .29 |

| Minor late (30 d to 5 y) complications | |||

| Vomiting/dehydration | 0 | 3/119 (2.5) | NA |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 11/121 (9.1) | 0 | NA |

| Ulcer/stricture at gastrojejunal anastomosis | 2/121 (1.7) | 6/119 (5.0) | NA |

| Dumping | 0 | 3/119 (2.5) | NA |

| Nonspecific abdominal pain | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Total | 13/121 (10.7) | 13/119 (10.9) | .96 |

| Major late (30 d to 5 y) complications | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 7/121 (5.8) | 0 | NA |

| Internal herniation | 0 | 17/119 (14.3) | NA |

| Incisional hernia | 3/121 (2.5) | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Total | 10/121 (8.3) | 18/119 (15.1) | .10 |

| Minor late (5-7 y) complications | |||

| Fistula and abscess | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Ulcer/stricture at gastrojejunal anastomosis | 0 | 2/119 (1.7) | NA |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 5/121 (4.1) | 0 | NA |

| Uretherolithiasis | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Adhesion-related intestinal obstruction | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Total | 6/121 (5.0) | 4/119 (3.4) | .75 |

| Major late (5-7 y) complications | |||

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 1/121 (0.8) | 0 | NA |

| Internal herniation | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Incisional hernia | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Candy cane/blind loop resection | 0 | 1/119 (0.8) | NA |

| Total | 1/121 (0.8) | 3/119 (2.5) | .37 |

Abbreviations: LSG, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy; LRYGB, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

Significant and sustained %EWL was achieved both after LSG (mean, 47%) and LRYGB (mean, 55%) in this 7-year follow-up of the SLEEVEPASS RCT with a high follow-up rate. The 2 procedures did not meet criteria for equivalence at 7 years. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass again resulted in slightly greater %EWL compared with LSG, but owing to the prespecified equivalence margins resulting in a very wide confidence interval for the difference, the difference cannot be interpreted as clinically relevant. There was no difference in long-term QoL between the procedures and bariatric surgery was associated with significant long-term DSQoL improvement. However, the QoL of trial patients remained lower than that of the age-standardized and sex-standardized general population throughout follow-up. Greater weight loss was associated with better DSQoL.

To our knowledge, SLEEVEPASS is so far the largest RCT comparing the outcomes of LSG and LRYGB with a 7-year follow-up.27 The second-largest RCT with similar long-term follow-up, the Swiss Multicenter Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS), showed no significant difference in percentage excess BMI loss between the 2 procedures.16 These 7-year results of the present RCT with the longest available follow-up, to our knowledge, indicate that %EWL trajectories between LRYGB and LSG seem to be quite constant from 5 to 7 years, with LRYGB being associated with greater %EWL at 7 years. In the SLEEVEPASS trial, LRYGB has been constantly associated with higher %EWL throughout all time points and the criteria for equivalence have not been met at any of the previous time points (6 months and 1, 3, and 5 years) either.10 However, using the definition of percentage of total weight loss, LRYGB was superior to LSG at the 5-year follow-up of the SLEEVEPASS trial, which is in concurrence with the findings of the recent large (n = 9710) unmatched surgical National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet) cohort study showing 6.2% to 8.1% more total body weight loss with LRYGB than with LSG.28 The variability of the weight loss results based on the definition of weight loss used highlights the importance of using uniform and standardized definitions to ensure optimal comparison between trials.29 This need for standardized reporting is evident also within each bariatric procedure; predictability of weight loss seems to vary between LRYGB and LSG, with the latter having more heterogeneity of weight loss outcomes.30

The other main focus of this 7-year report was detailed long-term QoL, covering both general HRQoL and DSQoL, including the durability and association of QoL improvement with weight loss. At 7 years, there were no differences in either DSQoL or HRQoL between LSG and LRYGB. In addition, a significant long-term improvement of DSQoL was demonstrated after both procedures compared with baseline. Health-related QoL remained higher compared with baseline after both procedures up to 5 years, but at 7 years, HRQoL descended to baseline level. At baseline and throughout the entire follow-up, HRQoL of the trial patients remained lower than the HRQoL of the age-standardized and sex-standardized general Finnish population despite the improvement provided by bariatric surgery. This report also demonstrated the association between weight loss and QoL; greater weight loss resulted in better DSQoL. This positive effect of bariatric surgery on overall QoL has been reported in many studies,13,15,31,32,33,34 but long-term QoL assessing all different domains of DSQOL and HRQoL are scarce, to our knowledge. In contrast to the improvement of DSQoL after both procedures compared with baseline, the HRQoL at 7 years declined back to baseline; this deterioration happened between 5 and 7 years. This difference of long-term HRQoL deterioration after bariatric surgery may be explained, at least partially, by potential differences in the mean age of the patients, as this same phenomenon associated with aging is also seen in the general population without obesity.23 The similarity of both long-term HRQoL and DSQoL after LSG and LRYGB in our study is in line with findings of previous studies assessing the different QoL domains.14,32,35,36,37,38 The type of procedure does not seem to affect QoL outcomes, but this needs to be assessed even at longer-term follow-up with regard to the weight loss outcome and its sustainability.

In addition to weight loss, other factors potentially having an effect on QoL are procedure-related adverse events, including interventions, operations, and hospitalizations after bariatric surgery. In a large surgical patient cohort (n = 33 560), these adverse outcomes were more often associated with LRYGB than LSG.39 In our study, from baseline to 5 years10 and also from 5 years to 7 years, there were no statistically significant differences in the complication rate between LSG and LRYGB, which is in accordance with the 5-year outcomes of the SM-BOSS RCT.16 High-quality bariatric surgery is associated with a low complication rate40; thus, detecting potential differences requires larger patient cohorts.28 In addition, the potentially higher incidence of GERD and Barrett esophagus after LSG16 may also play a role in long-term QoL.16,37,41 The issue of GERD and Barrett esophagus needs to be assessed at long-term follow-up of RCTs; all of the SLEEVEPASS trial patients will undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy at 10-year follow-up, allowing comparison with preoperative esophageal status.

Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations stated earlier,10 including the potential learning curve effect in both groups owing to the small number of bariatric procedures performed in Finland during trial enrollment as well as the lack of standardized GERD symptom assessment. Third, the predefined equivalence margins may be considered a potential limitation. They were set somewhat arbitrarily owing to little clinical information available to provide a good estimate for this minimal clinically important difference. This fact underlines the complexity and challenges of establishing this minimal clinically important difference in clinical trials, especially in trials addressing issues with only little clinical information at the time of study initiation. Fourth, the lack of comorbidity results in this 7-year report can also be seen as a limitation. However, as there were no major differences in comorbidity remission at 5 years,10 owing to manuscript word limitations and to add to the current literature, we decided to focus on the detailed analysis of both DsQoL and HRQoL, which have not yet been reported at long term. The most important comorbidity is type 2 diabetes and according to the 5-year outcomes of both the SLEEVEPASS10 and SM-BOSS16 studies, there was no difference between the 2 procedures regarding type 2 diabetes. At 5 years, this was also true for dyslipidemia remission. A recent meta-analysis similarly showed no difference in type 2 diabetes remission, but LRYGB was superior for dyslipidemia remission.27 In contrast, the PCORNet study showed superior type 2 diabetes remission after LRYGB compared with LSG.28 However, to detect a 10-percentage-point difference in the type 2 diabetes remission rate between the operations, about 700 patients with type 2 diabetes would need to be enrolled, which will be achievable only by future scientific collaboration using large prospective cohorts. Fifth, 24.2% of patients (58 of 240) were lost to follow-up at 7 years. However, the dropout rates were similar in both groups and the baseline characteristics of the patients lost to follow-up did not differ from those of the patients who completed the 7-year follow-up. On the other hand, this follow-up rate can be considered a study strength because, at 7 years, it compares favorably with most other studies reporting long-term follow-up.9 In addition, the dropout rate was similar in both groups, minimizing the potential bias associated with it. Other strengths of the study are the large number of patients, the 7-year follow-up, and a randomized, multicenter, multisurgeon setting. A major advantage in terms of QoL assessment is the inclusion of both DSQoL and HRQoL throughout the whole study period from baseline up to 7 years.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and LRYGB were not equivalent in terms of %EWL at 7 years. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass resulted in greater weight loss, but the difference was not clinically relevant based on the prespecified equivalence margins. There was no difference in long-term QoL between the procedures and bariatric surgery was associated with significant long-term DSQoL improvement. Greater weight loss was associated with better DSQoL.

Trial Protocol

eFigure. A, 15D Total Score at Each Follow-up Point. B, 15D Dimensions for Normal Population vs Study Patients at Baseline. C, 15D Dimensions for Normal Population vs Study Patients at 7 Years.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Afshin A, Forouzanfar MH, Reitsma MB, et al. ; GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators . Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):13-27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1614362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2284-2291. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(21):2292-2299. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.6361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Courcoulas AP, Belle SH, Neiberg RH, et al. Three-year outcomes of bariatric surgery vs lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes mellitus treatment: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):931-940. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, et al. ; STAMPEDE Investigators . Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes—5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):641-651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams TD, Davidson LE, Litwin SE, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes 12 years after gastric bypass. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1143-1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee WJ, et al. Lifestyle intervention and medical management with vs without Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and control of hemoglobin A1c, LDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure at 5 years in the Diabetes Surgery Study. JAMA. 2018;319(3):266-278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. IFSO worldwide survey 2016: primary, endoluminal, and revisional procedures. Obes Surg. 2018;28(12):3783-3794. doi: 10.1007/s11695-018-3450-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Puzziferri N, Roshek TB III, Mayo HG, Gallagher R, Belle SH, Livingston EH. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312(9):934-942. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salminen P, Helmiö M, Ovaska J, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the SLEEVEPASS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):241-254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolotkin RL, Andersen JR. A systematic review of reviews: exploring the relationship between obesity, weight loss and health-related quality of life. Clin Obes. 2017;7(5):273-289. doi: 10.1111/cob.12203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersen JR, Aasprang A, Karlsen TI, Natvig GK, Våge V, Kolotkin RL. Health-related quality of life after bariatric surgery: a systematic review of prospective long-term studies. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(2):466-473. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.10.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macano CAW, Nyasavajjala SM, Brookes A, Lafaurie G, Riera M. Comparing quality of life outcomes between laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass using the RAND36 questionnaire. Int J Surg. 2017;42:138-142. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.04.061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Major P, Matłok M, Pędziwiatr M, et al. Quality of life after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2015;25(9):1703-1710. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1601-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hachem A, Brennan L. Quality of life outcomes of bariatric surgery: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2016;26(2):395-409. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1940-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peterli R, Wölnerhanssen BK, Peters T, et al. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(3):255-265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmiö M, Victorzon M, Ovaska J, et al. SLEEVEPASS: a randomized prospective multicenter study comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: preliminary results. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(9):2521-2526. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2225-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helmiö M, Victorzon M, Ovaska J, et al. Comparison of short-term outcome of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass in the treatment of morbid obesity: a prospective randomized controlled multicenter SLEEVEPASS study with 6-month follow-up. Scand J Surg. 2014;103(3):175-181. doi: 10.1177/1457496913509984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brethauer SA, Kim J, el Chaar M, et al. ; ASMBS Clinical Issues Committee . Standardized outcomes reporting in metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2015;11(3):489-506. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, et al. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(3):383-393. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70740-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205-213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oria HE, Moorehead MK. Bariatric analysis and reporting outcome system (BAROS). Obes Surg. 1998;8(5):487-499. doi: 10.1381/096089298765554043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sintonen H The 15D instrument of health-related quality of life: properties and applications. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):328-336. doi: 10.3109/07853890109002086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alanne S, Roine RP, Räsänen P, Vainiola T, Sintonen H. Estimating the minimum important change in the 15D scores. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(3):599-606. doi: 10.1007/s11136-014-0787-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koskinen S, Lundqvist A, Ristiluoma N Terveys, toimintakyky ja hyvinvointi Suomessa 2011 (In Finnish). National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Report 68/2012. Accessed May 4, 2020. https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/90832/Rap068_2012_netti.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 26.Moorehead MK, Ardelt-Gattinger E, Lechner H, Oria HE. The validation of the Moorehead-Ardelt Quality of Life Questionnaire II. Obes Surg. 2003;13(5):684-692. doi: 10.1381/096089203322509237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han Y, Jia Y, Wang H, Cao L, Zhao Y. Comparative analysis of weight loss and resolution of comorbidities between laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis based on 18 studies. Int J Surg. 2020;76:101-110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.02.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McTigue KM, Wellman R, Nauman E, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative . Comparing the 5-year diabetes outcomes of sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass: the National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network (PCORNet) Bariatric Study. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(5):e200087. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salminen P Standardized uniform reporting and indications for bariatric and metabolic surgery: how can we reach this goal? JAMA Surg. 2018;153(12):1077-1078. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azagury D, Mokhtari TE, Garcia L, et al. Heterogeneity of weight loss after gastric bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and adjustable gastric banding. Surgery. 2019;165(3):565-570. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.08.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooiman MI, Aarts EO, Janssen IMC, Hazebroek EJ, Berends FJ. Weight loss, remission of comorbidities, and quality of life after bariatric surgery in young adult patients. Obes Surg. 2019;29(6):1851-1857. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03781-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versteegden DPA, Van Himbeeck MJJ, Nienhuijs SW. Improvement in quality of life after bariatric surgery: sleeve versus bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14(2):170-174. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sha Y, Huang X, Ke P, et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus sleeve gastrectomy for type 2 diabetes mellitus in nonseverely obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Surg. 2020;30(5):1660-1670. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04378-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helmiö M, Salminen P, Sintonen H, Ovaska J, Victorzon M. A 5-year prospective quality of life analysis following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2011;21(10):1585-1591. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0425-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nickel F, Schmidt L, Bruckner T, Büchler MW, Müller-Stich BP, Fischer L. Influence of bariatric surgery on quality of life, body image, and general self-efficacy within 6 and 24 months—a prospective cohort study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(2):313-319. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.08.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rausa E, Kelly ME, Galfrascoli E, et al. Quality of life and gastrointestinal symptoms following laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2019;29(4):1397-1402. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-03737-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Biter LU, van Buuren MMA, Mannaerts GHH, Apers JA, Dunkelgrün M, Vijgen GHEJ. Quality of life 1 year after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a randomized controlled trial focusing on gastroesophageal reflux disease. Obes Surg. 2017;27(10):2557-2565. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2688-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu Z, Sun J, Li R, et al. A comprehensive comparison of LRYGB and LSG in obese patients including the effects on QoL, comorbidities, weight loss, and complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2020;30(3):819-827. doi: 10.1007/s11695-019-04306-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Courcoulas A, Coley RY, Clark JM, et al. ; PCORnet Bariatric Study Collaborative . Interventions and operations 5 years after bariatric surgery in a cohort from the US National Patient-Centered Clinical Research Network Bariatric Study. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):194-204. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2019.5470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gero D, Raptis DA, Vleeschouwers W, et al. Defining global benchmarks in bariatric surgery: a retrospective multicenter analysis of minimally invasive Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Ann Surg. 2019;270(5):859-867. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felsenreich DM, Kefurt R, Schermann M, et al. Reflux, sleeve dilation, and Barrett’s esophagus after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: long-term follow-up. Obes Surg. 2017;27(12):3092-3101. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2748-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eFigure. A, 15D Total Score at Each Follow-up Point. B, 15D Dimensions for Normal Population vs Study Patients at Baseline. C, 15D Dimensions for Normal Population vs Study Patients at 7 Years.

Data Sharing Statement