Abstract

Kidney transplant recipients are at increased risk for infection, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), given ongoing immunosuppression. In individuals with COVID-19, complications including thrombosis and endothelial dysfunction portend worse outcomes. In this report, we describe a kidney transplant recipient who developed severe thrombotic microangiopathy with a low platelet count (12 ×109/L), anemia (hemoglobin, 7.5 g/dL with 7% schistocytes on peripheral-blood smear), and severe acute kidney injury concurrent with COVID-19. The clinical course improved after plasma exchange. Given this presentation, we hypothesize that COVID-19 triggered thrombotic microangiopathy.

Index Words: COVID-19, kidney transplant, thrombotic microangiopathy, acute kidney injury

Many systemic complications associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been described.1, 2, 3, 4 There is a complex relationship between COVID-19 and pathologic activation of immune cells, with not only inflammatory pathway activation and the presence of cytokine storm but also endothelial injury, dysfunction, and microthrombotic pathway activation.5, 6, 7, 8 We describe a kidney transplant recipient with COVID-19 who developed severe thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) in the setting of acute infection.

Case report

The patient is a man in his 40s who is 9 years status post cadaveric donor kidney transplantation; kidney failure was secondary to Liddle syndrome with mutation of gene SCNN1B. The patient was maintained on an immunosuppression regimen of tacrolimus, everolimus, and prednisone. There was no history of rejection, and he had no history of donor-specific antibodies. At his most recent follow-up assessment 1 month before admission, serum creatinine level was 1.75 mg/dL, estimated glomerular filtration rate was 42 mL/min, serum tacrolimus level was 5.3 ng/mL, and everolimus level was 3.6 ng/mL, with normal urinalysis results.

The patient presented with fever (maximum noted of 38 ºC at home), dyspnea, diarrhea, and abdominal pain for 1 week. On initial examination, temperature was 37 ºC, blood pressure was 122/60 mm Hg, pulse rate was 90 beats/min, and oxygen saturation was 93% (while breathing ambient air); he had bibasilar crackles and appeared volume depleted. Laboratory results are summarized in Table 1. The main findings were lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, high serum C-reactive protein and D-dimer levels, acute kidney injury with metabolic acidosis, and the presence of epithelial and granular casts on urinalysis. Anemia was not present. Thoracic radiography showed an interstitial pulmonary infiltrate on the basal right lung. A nasopharyngeal swab followed by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assessment confirmed the diagnosis of COVID-19.

Table 1.

Baseline and Follow-up Serum Parameters

| Measure | Reference Range | Baseline | D1 | D3 | D6 | D8 | D11 | D13 | D17 | D19 | D22 | D23 | D36 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13-17.5 | 14.2 | 13.1 | 11.6 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 7.6 | 7.0 | 7.8 | 8.0 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 11.6 |

| White blood cell count, ×109/L | 4.00-10.00 | 6.80 | 9.70 | 11.90 | 6.70 | 10.20 | 8.80 | 10.30 | 11.65 | 10.30 | 9.9 | 6.0 | 6.0 |

| Total neutrophils | 1.8-7.5 | 4.5 | 8.9 | 10.9 | 4.9 | 8.2 | 6.5 | 8.0 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 7.6 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| Total lymphocytes | 1.3-3.5 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.5 |

| Total monocytes | 0.2-1.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Platelet count, ×109/L) | 140-400 | 144 | 85 | 84 | 54 | 29 | 12 | 60 | 151 | 163 | 155 | 135 | 160 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 10.5-13.5 | 11.8 | 13.2 | 13.0 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 13.4 | 12.4 | 12.9 | 13.4 | 14.1 | 12.1 | 12.0 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 27-38 | 0.95 | 21.8 | 27.8 | 30.1 | 25 | 24.2 | 27.8 | 27.6 | 27.8 | 30.2 | 30.0 | 29.3 |

| Fibrinogen, mg/dL | 150-450 | 409 | 720 | 692 | 793 | 712 | 733 | 297 | 332 | 452 | 684 | 431 | 469 |

| D-Dimer, ng/mL | 0-250 | — | 304 | 177 | 515 | 488 | 526 | 465 | 580 | 455 | 528 | 567 | 95 |

| Haptoglobin, mg/dL | 27-129 | — | — | — | — | <6 | — | <6 | <6 | 32 | — | — | 41 |

| Albumin, g/L | 3.4-4.8 | 4.2 | 3.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 5-41 | — | 24 | 25 | 40 | 46 | 29 | 21 | 35 | 37 | 37 | 26 | 30 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 39-308 | — | 519 | 672 | 894 | a | a | 564 | 324 | a | 276 | 175 | 129 |

| Creatinine kinase, U/L | 39-308 | — | 118 | 437 | 376 | 533 | 402 | 82 | 43 | 33 | 18 | 19 | 31 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.70-1.20 | 1.75 | 3.69 | 3.75 | 4.56 | 7.36 | 8.79 | 6.06 | 3.05 | 2.68 | 2.68 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | ≥60 | 42 | 18 | 17 | <15 | <15 | <15 | 247 | <15 | 26 | 27 | 39 | 39 |

| Urea, mg/dL | 15-45 | 81 | 139 | 167 | 179 | 257 | 311 | <15 | 122 | 110 | 121 | 69 | 43 |

| High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I, pg/mL | — | — | — | — | 1618.5 | 830 | 131.7 | 28.2 | 4.8 | — | — | 35270 | 7.3 |

| Serum ferritin, μg/L | 22-274 | — | — | 10,031 | — | 7,188 | 8,554 | — | — | — | — | 1,650 | 190 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 0.00-0.50 | — | 0.33 | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.60 | 1.9 | — | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| C-Reactive protein, mg/dL | 0.-0.5 | — | 13 | 15.6 | 23.1 | 16.1 | 20.6 | 4.4 | 0.12 | 3.2 | 8.1 | 5.2 | 0.6 |

| Interleukin 6, pg/mL | <4.3 | — | — | — | 105.9 | 216.7 | — | — | — | — | — | 87.0 | — |

| Tacrolimus, ng/mL | 4.0-10.0 | 5.4 | — | >30 | >30 | 2.9 | 0.6 | — | — | — | — | — | 4.2 |

| Everolimus, ng/mL | 3.0-8.0 | 3.6 | 12.7 | — | 6.1 | — | <0.4 | — | — | — | — | — | 3.0 |

Note: Conversion factors for units: creatinine in mg/dL to μmol/L, ×88.4.

Abbreviations: D, day; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Hemolysis interference.

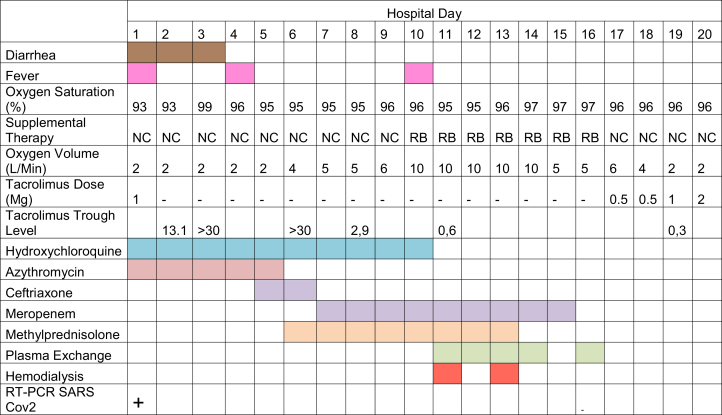

The course of the patient’s symptoms and treatments are summarized in Figure 1. We initiated supportive treatment with oxygen therapy and volume repletion and started empiric treatment with hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. We initially reduced the tacrolimus dose and discontinued everolimus treatment. Two days later, tacrolimus level remained elevated and we discontinued all immunosuppression. On the third hospital day, the patient had high levels of pancreatic enzymes without abdominal pain, diarrhea, or other gastrointestinal symptoms, with subsequent normalization on the following days. On hospital day 9, he had an elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I level without chest pain and with a normal electrocardiogram and normal biventricular function on the echocardiogram. Myocarditis related to COVID-19 was presumptively diagnosed. His respiratory status subsequently worsened and a chest radiograph revealed new bilateral pulmonary infiltrations. He started a methylprednisolone bolus (2 mg/kg per day) for 7 days and oxygen supplementation was increased.

Figure 1.

Baseline and follow-up clinical symptoms and treatments. Abbreviations: NC, nasal cannula; RB, reservoir bag; RT-PCR, reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; SARS-CoV2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

On hospital day 11, a diagnosis of TMA was made based on the following findings: anemia with hemoglobin level of 7.5 g/dL, thrombocytopenia with platelet count of 12 ×109 /L, reticulocytosis, elevated lactate dehydrogenase level, 7% schistocytes on peripheral-blood smear, negative direct and indirect Coombs test, undetectable haptoglobin, and acute kidney injury with serum creatinine level peaking at 8.79 mg/dL. ADAMTS 13 (von Willebrand factor protease) activity of 68% excluded thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. There was no presence of bacteria pathogens on stool culture or urinary antigen Streptococcus pneumoniae. Serologic tests for HIV, hepatitis C virus, and parvovirus B19 were negative. Cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr virus serologic test results were negative. Immunologic study results, including antinuclear antibody, anti–double strand DNA, antiphospholipid antibody, complement, and immunoglobulin, were normal.

To treat TMA, the patient received 5 sessions of plasma exchange with fresh frozen plasma replacement, and 2 hemodialysis sessions were necessary. Subsequently, serum creatinine level decreased to 2.5 mg/dL and there was no evidence of further hemolysis. Immunosuppressive treatment was reintroduced. On hospital day 23, the patient developed chest pain accompanied by elevated high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I level. Acute myocardial infarction was diagnosed and he was successfully treated with angioplasty of the right coronary artery. He was discharged on hospital day 36 with recovery of kidney function and normalized platelet count.

Discussion

Multiple complications related to COVID-19 have been described, including respiratory failure, myocarditis, and thrombosis.9 To our knowledge, this is one of the only reports of COVID-19–associated TMA.

Kidney transplant recipients have risk factors for TMA, specifically use of calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus. Our patient had been receiving tacrolimus for the last 9 years without side effects. Although markedly elevated serum tacrolimus levels could play a role in the development of TMA, many viruses may provoke TMA.10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15 In this case, although it is possible that both factors were complicit in TMA, previous studies published about COVID-19 in kidney transplant recipients suggest that high serum tacrolimus levels and acute kidney injury are frequent; however, TMA has not been reported.

Multiple reports indicate that systemic effects on the vasculature are common in COVID-19, including a procoagulant milieu.9,11,12 There is pathologic activation of immune cells with destructive mechanisms through the endothelial system, with subsequent endothelial dysfunction, microthrombotic pathway activation, and complement activation.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 In the current case, we ruled out many additional causes for TMA given negative serologic test results and negative blood, urine, and stool cultures. The patient received low doses of enoxaparin as prophylaxis during the first 5 days, but we stopped the treatment when platelet counts decreased, and we did not appreciate any platelet recovery, making heparin-induced thrombocytopenia unlikely.

COVID-19 may have direct and indirect effects on the kidney, with studies suggesting that 7% of patients with COVID-19 develop acute kidney injury, with as many as 37% of hospitalized patients developing acute kidney injury.20 Whether this is a direct effect of the virus on the kidney or indirect effects in the setting of systemic illness or a combination of these factors remains uncertain. In our case, the clinical presentation was most consistent with acute kidney injury in the setting of TMA.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Arturo Bascuñana, MD, Antonia Mijaylova, MD, Almudena Vega, PhD, Nicolás Macías, PhD, Eduardo Verde, PhD, Maria Luisa Rodríguez-Ferrero, MD, Andrés Delgado, MD, Javier Carbayo, MD, and Marian Goicoechea, PhD.

Support

None.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests

Patient Consent

The authors declare that they have obtained consent from the patient discussed in the report.

Peer Review

Received April 21, 2020. Evaluated by 1 external peer reviewer, with direct editorial input from an Associate Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form September 27, 2020.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou P., Yang X.-L., Wang X.-G. A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature. 2020;579(7798):270–273. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holshue M.L., DeBolt C., Lindquist S. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(10):929–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Onder G., Rezza G., Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323(18):1775–1776. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang D., Hu B., Hu Ch. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shi S., Qin M., Shen B. Association of cardiac injury with mortality in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;25(7):802–810. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.0950. 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar D., Michaels M.G., Morris M.I. Outcomes from pandemic influenza A H1N1 infection in recipients of solid-organ transplants: a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(8):521–526. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70133-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wux C., Chen X., Cai Y. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1–11. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danzi G.B., Loffi M., Galeazzi G., Gherbesi E. Acute pulmonary embolism and COVID-19 pneumonia: a random association? Eur Heart J. 2020 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa254. ehaa254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murer L., Zacchello G., Bianchi D. Thrombotic microangiopathy associated with parvovirus B 19 infection after renal transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(6):1132–1137. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1161132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Java A., Edwards A., Rossi A. Cytomegalovirus-induced thrombotic microangiopathy after renal transplant successfully treated with eculizumab: case report and review of the literature. Transpl Int. 2015;28(9):1121–1125. doi: 10.1111/tri.12582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pham P.T., Peng A., Wilkinson A.H. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus-associated thrombotic microangiopathy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;36(4):844–850. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2000.17690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu L., Xu X., Ma K. Successful recovery of COVID-19 pneumonia in a renal transplant recipient with long-term immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(7):1859–1863. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su H., Yang M., Wan C. Renal histopathological analysis for 26 postmortem findings of patients with COVID-19 in China. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valga F., Vega N., Macia M. Targeting complement in severe coronavirus disease 2019 to address microthrombosis. Clin Kidney J. 2020;13(3):477–479. doi: 10.1093/ckj/sfaa095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ackermann M., Verleden S.E., Kuehnel M. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirsch J.S., Ng J.H., Ross D.W. Acute kidney injury in patients hospitalized with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;98(1):209–218. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]